Clive James's Blog, page 3

March 25, 2009

Francis Wheen

Francis Wheen, born in 1957, was educated at Harrow, where he was a contemporary of Mark Thatcher. Wheen’s Marxist inclinations thus had plenty of material to work on from an early date, and it can be said that his leftist critique of society has always been at least as well grounded in observation as in theory. Based variously at the Guardian, at the Evening Standard and at Private Eye, he has kept up a constant barrage of outgoing artillery fire in the best traditions of polemical journalism – i.e. the polemics take account of the real world. His gift for invective can be uncomfortable for those who find themselves on the other end of it, as I know to my cost, but there is no denying the continuing relevance of his fine anger. His book Hoo-hahs and Passing Frenzies: Collected Journalism 1991-2001, which came out in 2002, remains a model of the genre: it deservedly won the 2003 George Orwell prize. To hindsight, the book, from which the pieces featured here are taken, proves that Wheen, while blazing away at all the expected targets, was already preparing himself for a new impatience: the Left, to which he nominally belonged, was starting to worry him with its incurable yearning for something more decisive than democracy. This new impatience broke into the clear when he gamely pilloried his own newspaper, the Guardian, for apologising –cravenly, in Wheen’s view – to Noam Chomsky over its supposed misrepresentation of his views on the massacre in Srebrenica. Wheen was a valuable addition to the list of signatories on the Euston Manifesto in 2006. The manifesto marked the point when a left-within-the-left lost patience with the host body’s sympathy for any force, no matter how extreme, that might embarrass the Western democracies. Along with Nick Cohen and Christopher Hitchens, Wheen became a target for unreconstructed radical journalists who found their breakaway colleagues guilty of Liberal Universalism. It was an accusation that Wheen, in particular, was well equipped to counter with learned scorn. As a Marxist who had actually read Marx (his biography of Marx was another prize-winner), he has the advantage of being able to provide his own theoretical back-up. But finally what makes him stand out is his inclusive style, sensitive to everything that is happening, and sometimes, remarkably, to what will happen next.

Francis Wheen, born in 1957, was educated at Harrow, where he was a contemporary of Mark Thatcher. Wheen’s Marxist inclinations thus had plenty of material to work on from an early date, and it can be said that his leftist critique of society has always been at least as well grounded in observation as in theory. Based variously at the Guardian, at the Evening Standard and at Private Eye, he has kept up a constant barrage of outgoing artillery fire in the best traditions of polemical journalism – i.e. the polemics take account of the real world. His gift for invective can be uncomfortable for those who find themselves on the other end of it, as I know to my cost, but there is no denying the continuing relevance of his fine anger. His book Hoo-hahs and Passing Frenzies: Collected Journalism 1991-2001, which came out in 2002, remains a model of the genre: it deservedly won the 2003 George Orwell prize. To hindsight, the book, from which the pieces featured here are taken, proves that Wheen, while blazing away at all the expected targets, was already preparing himself for a new impatience: the Left, to which he nominally belonged, was starting to worry him with its incurable yearning for something more decisive than democracy. This new impatience broke into the clear when he gamely pilloried his own newspaper, the Guardian, for apologising –cravenly, in Wheen’s view – to Noam Chomsky over its supposed misrepresentation of his views on the massacre in Srebrenica. Wheen was a valuable addition to the list of signatories on the Euston Manifesto in 2006. The manifesto marked the point when a left-within-the-left lost patience with the host body’s sympathy for any force, no matter how extreme, that might embarrass the Western democracies. Along with Nick Cohen and Christopher Hitchens, Wheen became a target for unreconstructed radical journalists who found their breakaway colleagues guilty of Liberal Universalism. It was an accusation that Wheen, in particular, was well equipped to counter with learned scorn. As a Marxist who had actually read Marx (his biography of Marx was another prize-winner), he has the advantage of being able to provide his own theoretical back-up. But finally what makes him stand out is his inclusive style, sensitive to everything that is happening, and sometimes, remarkably, to what will happen next.

March 17, 2009

The Engine and the Roses

But the approach was different—a leather-lunged engine pushed the passengers round and round in a corkscrew, mounting, rising; they chugged through low-level clouds and for a moment Dick lost Nicole’s face in the spray of the slanting donkey-engine

(Tender is the Night, Book II, chapter xii)

Dorothy Perkins roses dragged patiently through each compartment slowly waggling with the motion of the funicular, letting go at the last to swing back to their rosy cluster. Again and again these branches went through the car.

(Tender is the Night, Book II, chapter viii)

After my interview with Clive James on F. Scott Fitzgerald was published, I sat down at the computer with my father George and we read through it together, until we had climbed as high as the moment where James and I discuss the ‘leather-lunged engine,’ and gloss over the phrase in puzzlement. I could tell by the expression on my father’s face that the ‘leather-lunged engine’ wasn’t something he was about to gloss over. A design engineer, not just by profession but vocation (he retired years ago but all the machines he designed still whirr and chime in his imagination) George looks at a steam engine the way I might look at a painting by Rembrandt: as a thing of beauty and a miracle of rare device, of which he always asks the question ‘How does it work?’ He told me exactly how the hydraulic engine on Fitzgerald’s mountain train would work, and I summarise his comments below.

After my interview with Clive James on F. Scott Fitzgerald was published, I sat down at the computer with my father George and we read through it together, until we had climbed as high as the moment where James and I discuss the ‘leather-lunged engine,’ and gloss over the phrase in puzzlement. I could tell by the expression on my father’s face that the ‘leather-lunged engine’ wasn’t something he was about to gloss over. A design engineer, not just by profession but vocation (he retired years ago but all the machines he designed still whirr and chime in his imagination) George looks at a steam engine the way I might look at a painting by Rembrandt: as a thing of beauty and a miracle of rare device, of which he always asks the question ‘How does it work?’ He told me exactly how the hydraulic engine on Fitzgerald’s mountain train would work, and I summarise his comments below.

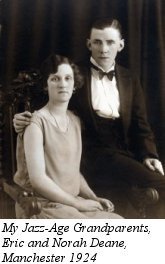

He also told me another little wonder. I was delighted to discover that in the garden of the house where I write this, the house where our family has lived since 1933, is a vigorous, seemingly unkillable Dorothy Perkins rose bush. Until George told me this, I hadn’t known the name of the variety—only that the rose at the bottom of the garden, the one that guarded us from the world beyond, was an exuberant, small, pink climber with a delicate scent. My grandfather Eric planted it sometime in the mid 30s, and we have been attempting to control it ever since.

But what a recognition scene! As George recounted that story, I knew how it felt to be in the funicul ar even more clearly than I had before. Yes, the stems of the roses are long and wild, and Fitzgerald is spot on in describing the way they invade the carriage. As kids, we had to push through those long stems as we exited the garden gate and walked into the field below the house in the same way that the funicular had to push through the roses as it climbed the mountain. One summer morning years ago, I shouldered my way through those roses after rain, and then tried to write a poem about the way rain water collected on each leaf and flower and deposited icy tear-streaks down my bare back as I walked under the roses. I had forgotten that abandoned poem until this conversation. So thanks to my father, I know the engine and I know the small but tenacious Jazz-Age roses. Thanks to him, the long stretch of distance between Fitzgerald and myself evaporates and the perfumed funicular and the chugging mountain train rise up before me out of the mist.

ar even more clearly than I had before. Yes, the stems of the roses are long and wild, and Fitzgerald is spot on in describing the way they invade the carriage. As kids, we had to push through those long stems as we exited the garden gate and walked into the field below the house in the same way that the funicular had to push through the roses as it climbed the mountain. One summer morning years ago, I shouldered my way through those roses after rain, and then tried to write a poem about the way rain water collected on each leaf and flower and deposited icy tear-streaks down my bare back as I walked under the roses. I had forgotten that abandoned poem until this conversation. So thanks to my father, I know the engine and I know the small but tenacious Jazz-Age roses. Thanks to him, the long stretch of distance between Fitzgerald and myself evaporates and the perfumed funicular and the chugging mountain train rise up before me out of the mist.

F. Scott Fitzgerald is even more accurate than Clive James or I imagined in our interview. In Tender is the Night, when he talks about a ‘leather-lunged engine’ in the scene where Dick Diver sees Nicole in the train carriage, it appears that he is talking about a particular part of the mechanism. Leather was used in hydraulic and steam engines to seal cylinders and valves. Leather was the material of choice in such engines because it was tough, but also because it flexed and bridged the gap between the piston and the cylinder. Until I knew this, I had thought of the image as being purely metaphorical, a way of describing the engine’s sound. I did not realise that the metaphorical element might reside chiefly in the ‘lung’ part of the image, and this is where you get to the heart of Fitzgerald: accurate observation becoming a strange, beautiful and sonorous metaphor.

It is a metaphor that Fitzgerald does not invent but reinvents. The Merriam Webster Dictionary tells us that the phrase ‘leather-lunged’ dates back to an earlier part of the Industrial Age. The phrase ‘leather-lunged singers’ is recorded as far back as 1846, ‘leather-lunged’ suggesting the loudness of voice required by singers and other performers to project their voices in an auditorium in the days before electronic amplification. In the dictionary example, the metaphor is used to describe a human sound in terms of machinery. Fitzgerald turns the metaphor upside down and uses it to give the machine an operatic human voice.

Yet, whether we want to praise the lyricism of the image or its technical accuracy, there can be no more perfect emblem of Fitzgerald’s achievement than the ‘leather-lunged engine’— except perhaps the Dorothy Perkins roses. Either the engine or the roses could stand as ideal metaphors for Fitzgerald’s prose. The struggle of the engine and the way it arrives ‘on top of the sunshine’ puts us in mind of the way he joins beauty and energy. On the other hand, we must not forget the tough little roses pushing their way into our sensory experience, overwhelming us again and again with their delicate scent and their thorny, joyous resilience.

Nichola Deane

February 17, 2009

Updates 2008

On this website, as of December 2008:

AUDIO:

Clive James BBC Radio 4 A Point of View

Transcripts and recordings of this month's broadcasts:

"How rich is rich?": on wealth and power

"Changing the government": on the American Presidential election

"Robin the Hood": on a new concept of action movies

"Bad language": on standards in broadcasting

"Glamourising terror": on The Baader-Meinhof Complex

VIDEO:

Postcard from Bombay

Talking in the Library, Series 6 (produced by TimesOnline): Clive James in conversation with Melvyn Bragg (click here for the presentation page by Arts Reporter Ben Hoyle)

Music Finds: Les Paul and Mary Ford ("How High the Moon")

TEXT:

New poem by Clive James: "Signing Ceremony" (The New Yorker, Dec. 1, 2008)

Prose Finds: The Wall Street Journal, on the current financial crisis; Joan Bakewell, on the BBC standards; Jeffrey Rosen, on privacy and security laws, and Germany's star literary critic Marcel Reich-Ranicki

New Guest Writer Nichola Deane

As of November 2008:

AUDIO:

Clive James on BBC Radio 4: A Point of View

(This new series of programmes will be available on this website in December. For previous Point of View programmes by Clive James, click here.)

GALLERY:

New section: Cartoons - introducing the work of Marf

Video art: Saatchi Face Parade

VIDEO:

'Video Finds' on YouTube, introduced by Clive James:

Dance: Alessandra Ferri as Juliet

Music: Show Me Heaven; Leopold Stokowski and the Faun

TEXT:

By Clive James:

Poem: Overview

TV criticism: articles from Glued to the Box: "Hrry Crpntr"; "Big-time Sue"; "There is no death"; "You tested the Gyroscope?"; "A horse called Sanyo Music Centre";"This false peace"

As of October 2008:

VIDEO:

Postcard from Paris

Talking in the Library: Clive James in conversation with Salman Rushdie and with Germaine Greer

(Due to a recent technical glitch, these interviews are currently available only as extracts. TimesOnline are working towards resolving the problem as fast as is technically possible. — Dec. 1, 2008)

AUDIO:

Clive James and Pete Atkin, in a podcast interview by David Hepworth for The Word (podcast), about forty years of songwriting

Clive James interview with Richard Dawkins at the Edinburgh Book Festival

Poetry (Chicago) Editor Christian Wiman, interview with Clive James

TEXT:

By Clive James:

Obituary for Pat Kavanagh

Poem 'We Being Ghosts'

On the new Talking in the Library series, an article for The Times

Review of Joseph Horowitz's book Artists in Exile: How Refugees from Twentieth Century War and Revolution Transformed the American Performing Arts (TLS, Sept 9, 2008)

As guest editor of Time Out Sydney: on Sydney vagrant Bea Miles and on Crime Movie Music

Television criticism: 6 new pieces from Glued to the Box: 'Oodnatta Fats', 'Borg's little bit extra', 'How do you feel?', 'Idi in exile', 'Master stroke', and 'Someone shart JR'.

GALLERY:

An addition to the Sarah Raphael pavilion: a Sarah Raphael profile by Geordie Greig, on the artist's surprising foray into abstraction (Modern Painters, winter 1998)

As of September 2008:

VIDEO:

Talking in the Library: Clive James in conversation with Tom Stoppard (Due to a recent technical glitch, this interview is currently available only as an extract. TimesOnline are working towards resolving the problem as fast as is technically possible. — Dec. 1, 2008)

Clive James on YouTube with Kate Winslet, and with Alice Cooper

Video Finds: Tito Gobbi and Marlon Brando

TEXT:

List of links to all on-line articles by Clive James about poetry and poets

Guest Poet Jamie McKendrick

Prose Finds: William Deresiewicz

FORTHCOMING:

Clive James's Talking in the Library 5th video series, including conversations with: actors and authors Emma Thompson and Stephen Fry, actor Jeremy Irons, novelist Nick Hornby, literary biographer Claire Tomalin, literary critic Professor John Carey, and television and film actors and authors Victoria Wood, Catherine Tate and Alexei Sayle. (Recorded and produced by SkyArts in May 2007, the programmes have all been broadcast on digital television but due to administrative complications the online launch has been delayed. We're working on it.)

As of August 2008:

VIDEO:

Video Finds: Actor John Gielgud in Peter Greenaway's Prospero's Books and in the 1978 BBC Richard II.

As of July 2008:

TEXT:

The Great Wrasse, by Clive James (from The Book of My Enemy), for Les Murray.

Guest Writer Marina Hyde digs deep on the crucial subjects of Paris Hilton, Trudie and Sting, Pete Doherty, and reflects on virtual illusion and the Internet.

Guest Poet Peter Porter. Introduction by Clive James, and 10 poems chosen by the author.

GALLERY:

Painting:

Sarah Raphael pavilion: with articles by William Boyd, Daniel Day-Lewis, Clive James, Andrew Motion, and Frederic Raphael

New works by painter Laura Smith, including paintings from her forthcoming exhibition (9 - 13 July 2008 at 54 The Gallery, Shepherd Market, Mayfair, London W1)

Bande dessinée (new section): Posy Simmonds

VIDEO:

Video Finds: Alessandra Ferri and Sting (Dance), and Laurence Olivier (Actors)

As of June 2008:

TEXT:

Frederic Raphael's foreword to In Love, by Alfred Hayes, and book extracts.

New guest writer Vicki Woods

Mark Steyn on Frank Sinatra's anthem "It Was A Very Good Year"

P.J. O'Rourke's travelogue on China

AUDIO:

Clive James reads out three poems from The Book of My Enemy.

VIDEO:

In the Mood for Love

Mr Hulot's Holiday

As of May 2008:

GALLERY:

"Geneviève Seillé: Beyond Reading", by Roger Cardinal

Four short films by Cordelia Beresford

TEXT:

Guest writer: art critic Laura Cumming

Prose Finds: Paul Berman on Islamism

Clive James: new poem Ghost Train to Australia; on writing lyrics: "My life in lyrics" (Guardian, April 1, 2008) and Cream articles

VIDEO:

Postcard from Berlin

Video Finds: the Silver Rose and Ian Dury

As of April 2008:

TEXT:

Guest writer: film director Peter Bogdanovich

Clive James: "The Perfectly Bad Sentence" and "Meeting MacNeice"

VIDEO:

Video Finds

GALLERY:

Painting: Albert Herbert and Geneviève Seillé

Posted on March 18, 2008:

TEXT:

Prose Finds: David Hepworth on the high-octane, trail-blazing, revolutionary American TV series about the drug war in Baltimore, The Wire.

As of February 2008:

TEXT:

Guest writer Jonathan Meades

Prose Finds: Binyavanga Wainaina writing about Africa; P.J. O'Rourke on the confessions of Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr; Noel Pearson on white guilt, victimhood and the radical centre; Patrick Smith on not loving the Airbus A380; Pascal Bruckner defending Ayaan Hirsi Ali.

GALLERY:

Sculptor Georgia Russell

Video and performance artist Éleonore Saintagnan

AUDIO:

Star Australian poets Judith Beveridge, Stephen Edgar, and Les Murray reading their poems.

January 27, 2009

Paterson "resonant"

‘All were skies falling silent.’ In this way, Don Paterson, poet, guitarist, aphorist and editor, distils the nature of his ‘revelations’ in the opening salvo of The Blind Eye, one of his three collections of aphorisms. To paraphrase Octavio Paz, it is the job of the poet to show the silence, and indeed to become a ‘master of silence.’ Paz made these comments with reference to Elizabeth Bishop, but that title, ‘master of silence,’ is one that in just over fifteen years Don Paterson can surely be said to have earned. Prizes and praises have greeted every collection to date, but the accolade ‘master of silence,’ whilst it cannot be awarded, can and should be suggested. Paterson’s poetry is the real thing: it resonates out of silence and returns the reader to silence. In his poetry collections, Nil Nil (1993), God’s Gift to Women (1997), The Eyes (1999), Landing Light (2003), and Orpheus (2006), his unique poetic voice refines and purifies itself. It is a voice that has such a fiercely independent existence that critical commentary hardly seems needed. For this reason, I have merely tried to point, in three different ways, to the resonant silence of the poems, the river of absence that flows through them.

Trying to flow with the poems, I have not stopped to analyse themes; rather, the themes emerge if you read the lists of words I have gathered from each of the collections, starting with Nil Nil. Each ‘word-hoard’ is comprised of words in the poems that have reacted on me and which, when placed together, tell a story from, if not the story of, each book. Hell; The Road; the search for a ‘you;’ trains; spent desire; God; and, of course, silence are all themes to look out for.

Difficult as these poems often are in terms of their argument and their subject-matter, they are easy to trust. Their brilliance stems from their syntax, the thread on which each ‘word-hoard’ is strung, and therefore I make some brief comments that point towards Paterson’s gifts in this area. But more than this, his poems claim us through their cadence, and so from syntax the natural progression is to a capsule essay on metre and its music. If the poems convince because of their syntax, they seduce because of the way they sing; for no matter how dazzling or intricate Paterson’s ideas, the music in his poems is never wayward, and carries all pain and delight in it. Watch the water move.

i) Word-hoards

Before you read or re-read Don Paterson’s poems, try this miniature compendium of words garnered from his various collections, not for size but for sound. Roll around a few of these gems on your tongue, against your palate, between your teeth: ‘gurry, winterbourne, rancour, Hilltown, futterin, shadows, lyre, ticktock, woodsmoke, whitewing, blackedged, gracile.’ How does that feel? Now try it at half the speed of your first attempt, making sure you say each word aloud and that there’s a slight pause between each one. For each comma read in a heartbeat. Keep track of your pulse, your breath. Let the words resolve into morphemes and almost lose their meaning: let them simply vibrate.

These poems are sounds that walk ahead of you. Their fabric is stitched with an array of threads. In Nil Nil, Paterson’s word-hoard reveals a hunger for every texture you can think of, from ‘lino’ to ‘gurry,’ and every kind of register from the obscene (‘cunt’) to the divine (‘irenicon’).

Tongue, pish, Murphy’s, black, guck, gurry, winterbourne, jism, tenement, Fomalhaut, ictus, bodhran, scything, cloaca, epicene, cunt, resonance, blind, lino, hare-lip, sick, gibbered, tenement.

Nil Nil begins with a solitary game of pool in The Ferryman’s Arms and the words you see here are little oil lamps in the gloom. Music, violence, poverty, religious mania, sickness and desire are some of the subjects explored, and the poetry feels like a sick pleasure, perhaps a spilt self.

lacuna, concatenation, Leucotomy, Origamian, pollen, junkie, golden, lifetime, sweetpea, loop-tape, weight, pricktease, hieratica, heart.

In every book of Paterson’s, the word ‘heart’ appears, and the heart of this book thuds like a bodhran played at battle speed:

glare, monochrome, half-lotus, balletic, kickabouts, Clatto, shanty-town, Tayport, Carnoustie, irenicon, wind, cloud, Venus, haar, nirvana, goodbye.

Even out of the element of their poems and forced into a morganatic union with other bedfellows, these words, in roughly the order they appear in the book, have a shuddering, debased grandeur, as though Paterson can gut a word like ‘pish’ and turn it inside out, revealing its acoustic swim-bladder, its sound-skeleton. How does he do that? Well, he both tells you and doesn’t tell you:

Thrown out in a glittering arc

As clear as the winterbourne,

The jug of Murphy’s I threw back

Goes hissing off the stone.

Whatever I do with all the black

Is my business alone.

(‘Filter’)

Alchemy is Paterson’s business, and he delights in any and all materials. As with the ‘pish’, so with with ‘cloaca’, ‘kickabout’, ‘tenement’: black to gold is always the trajectory. It is a matter of physiological process—and a mystery. The process involves fortuitous meetings of two or more words gathered together, words finding each other as lovers, disciples and congregations might, the words breaking their boundaries to belong, to sink into each line. What assurance: to begin this way, with all these dark sounds igniting and blazing! ‘Tongue’ is one of Nil Nil’s opening words and ‘Goodbye’ is its last, as if by the end of his first collection, Paterson is already doing a disappearing act. But then he starts Nil Nil at ‘The Ferryman’s Arms’ with a coin already on his tongue.

Where do you go from there, if Charon is already waiting and the meter is ticking? If you are Paterson, you go AWOL looking for what was lost before you reached the crossing-place: a brother, mother, sisters, the Horseman’s word and a Scheherezade or two. Yet, rifling through the word-hoard of God’s Gift to Women the book begins to look like a strange affirmation of faith.

Church, butterscotch, rancour, heartburn, pray, Caird, lochan, Kemback, kiosk, saint, stalled, thorn, mother, carcass, Fetherlite, harem, sea, weight, vortex.

We begin in the ‘little church’ of poetry, a base camp for journeys backwards in time: to lost and perfect days in childhood out by the lochan; to days that a lost brother never lived; to stalled nights; and to what is lost at sea and in the storm, and then

Messiaen, Hilltown, florins, charred, Macalpine, mothers, Cocteau, kiss, black, Ladyburn, chlairsach, North British, whisky, Scheherezade, beggar, fuck, futterin, Hameseek, furrow,

Coins again, drinking, sex and music take us on a long and squalid but beautiful binge until we see

Venus, morganatic, sleekit, bleeding, death-camp, mother, cock, Cerberus, singer, engines, angels, SPONG, phthistical, spanking, breeks, wank, innocence, Wolflaw, tallow, shadows, faith.

By the close, it is morning; morning brought coughing into life with a couple of Nurofen and a pint of coffee. The same Anglo-Saxon dirt is here (‘cock,’ and ‘fuck,’), the Dundee sorrow (‘kiosk,’ ‘Hilltown,’ ‘Macalpine’) and the nightmare (‘death-camp,’ ‘Cerberus,’ ‘Wolflaw’) but there are grace-notes too. Uplift comes from ‘saint’ and ‘singer,’ ‘kiss’ and ‘angels.’ No more comforting or comfortable than the Nil Nil doctrine, God’s Gift nonetheless makes notable adjustments of texture, giving us, in a number of poems, a world to aery thinness beat. A deity is invoked, and the poet gazes up, breaking his focus on the abyss.

What he sees when his gaze shifts falls on us like a sunshower in The Eyes where everything and nothing is his. The Spanish poet Antonio Machado is his master here, his giver of breath and bread. For the first time, Paterson makes versions—not translations. In his versions of Machado’s poems, the fabric of the words is gossamer, or lighter. Words begin their return to breath.

Wait, drink, Buddha, Cain, lyre, breath, rainbow, eyes, sea, heartless, Lord, Guadarrama, obol, desire, forget, desire, knots, heart, shoreline, silence, salt-grains, honeycomb, hour, beloved, dust.

Where are we now? Although the location is the Spain inhabited by Machado, the words gathered here do not belong to any one country. Rootless, they sound like a heart or a river rising:

Andalusia, hosannas, ticktock, bells, no, anchor, work, Bergson, salto inmortal, sea, weep, quiver, nothing, woodsmoke, dream, Name, ashless, ripe, parched, you, you, lover, starless, Christ.

Clocks and bells whirr and chime, but time slips past (there is no anchor in these Machado poems) and even the sense of ‘I’ loosens. The poems hunt out an ever-receding ‘you,’ travelling far into

NIHIL, silver, black, black, heart, hinge, lilies, sing, water, rock, river, pulse, orange-trees, shore, desperate, she, evening, Heraclitean, gathering, zero, oblivion, Machado, absence.

So we ‘wait’ and our reward is ‘absence,’ and this book seems to rest in that absence. Not only rare fauna like ‘obol’ sing (note: a word for Charon’s currency inhabits every book in our journey so far) but words like ‘rock’ and ‘river.’ And not only rock and river cantillate. Even an abstract imperative like ‘wait’ is rendered weightless and airborne: ‘wait as the beached boat waits, without a thought /for either its own waiting or departure’ (‘Advice’). ‘No’ and ‘not’ arrive in you with the force of their heterographs ‘know’ and ‘knot.’ A great ‘no’ is all we know here, and what is ‘not’ is always before us as we read, a slip-knot of longing. Indeed, longing for the beautiful is all that seems to hold some of these poems on the page: the salt-grain’s ache for ‘honeycomb’ and the heart opening like a hinge for more of the lilies, orange-trees, and bells.

In the gathering, scented dusk of The Eyes, it is easy to forget the bleating ‘Mooncalf’ of Nil Nil or the female ‘drunken carcasses’ littering God’s Gift. But Paterson does not, and the shadow-river pulsing below the river returns in his next work, Landing Light, like a bradycardiac bad dream. If The Eyes felt like a Paradiso of sorts, Landing Light loops back to hell—but with moments of blissful surfacing to draw breath.

Luing, motherland, catholicon, whitewing, work, wingspan, minuscule, boked, Strophades, she, silent, worm, shite, sons, roses, wet, knuckled, pearl, ochre-pink, hawk, cave, Leda, wolfing, wives,

We begin in a heavenly Scottish landscape—in poems like ‘Luing,’ a remote island becomes as weightless and heavenly as Machado’s Spain— but we quickly rebound from heaven into hell. The middle of the book is largely a place of the skull:

Hindemith, Gromit, rose, worm, Scheherezade, Sodom, pisshole, bricht, luthier, skull, Padmasambhava, delete, heart, blood, lover, triste, arse, feedback-loop, oxter, ochone, malebolge,

And yet, no matter how deeply into the abyss we travel, our guide will lead us back into the upper air, after a spot of purgation:

No No, Babel, ayebydan, loins, thigh, ear, Sika, ecstatic, damn, facsimile, begging-bowl, lyre, alibi, ken, sternless, birk, alane, Mother, girl, wonder, blackedged, love.

Hell is in the ‘malebolge,’ the ‘pisshole’ stare of the poetaster, the ‘feedback-loop’ of torture. But the bliss! The bliss is animal and sexual (‘wet’ and the mildly sadistic-sounding ‘knuckled;’ ‘pearl,’ and the light, delicious consonantal kick of ‘ochre-pink’). The bliss is also linguistic: Scots rises in Landing Light like a spring in three poems: ‘Form,’ ‘Twinflooer,’ ‘Zen Sang at Dayligaun.’ Not the invented Scots of MacDiarmid, this is something that feels both pentecostal and truly spoken: a currency that is exchanged in a place (a living, breathing Scotland) but escapes out of time, into the unbound realm of Dasein und Engeln, being and angels.

An’ there’s nae burn or birk at aw

But jist the sang alane

(‘Zen Sang at Dayligaun.’)

Pure Rilke in its dissolve, this is also a pure-sounding Scots, not walking softly on the land but flowing and singing across its surface like a caress. ‘Burn’ and ‘birk’ are not Scots exotica, but the plainest and arguably the loveliest metonyms you could use to stand for the Scottish landscape. But these are also literary metonyms. The burn’s fiery water fluting home brushes past Hopkins; birch trees flexing swing forever in the direction of Robert Frost: two words alliterating gently out of the soil and into song.

Ah, song. The word takes us straight to Orpheus, Paterson’s versions of Rilke’s über-poems. Rilke’s sonnets, once read, can enter the reader as if there were no other real poems in existence, so powerful and seductive is their music. After Rilke, even the word ‘tree’ becomes a song in itself (had you really known what a tree was until Rilke set the word ringing for you?); words like ‘mirror’, ‘mouth’ and ‘sigh’ go forth and fructify in entirely new ways; these hungry little words, so pure and unexpectedly vast. Or, at least, this new way of seeing and hearing occurs if you have read Rilke as Paterson evidently has:

Tree, lyre, girl, death, arose, crossroads, sigh, heavy, heavier, spaces, true, song, belong, willow, pitcher, wine, herald, lament, lyre, mouths, hesitance, spurring, reining, praise, O, reach, bestows,

Each word is rootless, as in the Machado poems, but here the tone is weightier, the nouns earthy; the Orpheus keynote of ‘lyre’ returns and returns to set every other word echoing:

apple, leaf, fugitive, juice, curse, pelt, ascent, lyre, perfected, drumbeat, blue, baptised, gracile, maenads, rocks, seas, eyes, losses, mirrors, kiss, beast, negate, invoke, torture, departure, glass,

Hints of fecundity, of ‘fruit’ and ‘juice,’ follow Rilke into sensual celebration, brief though this is, as the lyre continues its song of departure:

shatters, meadow-brother, wind, heals, spent, balance, dancer, blur, gold, heart, grief, , axe, bough, danger, star, lone, choir, one, lyre, impermanence, lyre, true, dark, crossing, I, flow, am.

Smooth as wave-worn pebbles, the Orpheus word-hoard is full of rounded sensual treasures: the tiger’s eye of ‘pelt,’ the tourmaline of ‘pitcher.’ They fall into two groups, words that spur us on like ‘shatters,’ ‘baptised,’ and ‘juice;’ and words that rein us in like ‘sigh,’ ‘grief’ and ‘willow.’ And yet, how little difference there seems to be between spurring on and reining in: in either case, the energy of the word, be it noun or verb, pulsates, a newborn image.

Only listening is necessary to catch the image and watch it melt, to say the sound and watch it run. But as Rilke takes pains to point out in the Duino Elegies, listening is no easy matter: the purest listening is a kind of emptying out in which the listener does not remain. No one hears; no one is left to hear; there is only hearing. Whatever the arguments about the nature of translation and the creation of versions, the poems Paterson resolves onto the page in Orpheus are made of that luminous hearing: never once in this collection do the individual words sound less than notes coaxed from the lyre.

ii) Syntax

But words are never individual. If Paterson’s words sound as though they come from the lyre, in Orpheus, Landing Light and elsewhere, it is because they flow and move in a particular way: it is because of their syntax. Paterson, the lover of words, is easy to find: name ‘pish’ or ‘grief’ or ‘juice’ and you feel you have him there before you. Evoke Paterson’s relationship with syntax, however, and he starts to run through your fingers.

Paterson is not a ‘lover of syntax’ or a ‘master of syntax.’ Syntax is something that our minds are in, the slipstream of our thought. Paterson is mastered by syntax, as every true poet should be. Think of that line from Hopkins, ‘Thou mastering-me-God,’ where God and poet are part of the same noun phrase; fighting, embracing, and indistinguishable, the ‘me’ subdued by a greater force.

Nil Nil’s murk is marked by attack of phrasing: ‘I’d swing for him, and every other cunt/happy to let my father know his station.’ Aggressive, ‘blunt’ and passionate but speaking, with the swing and punch of verbal combat, as he picks up tired figures of speech (‘swing for him’ ‘know his station’) and puts his lips to them. There is no violent conjunction of phrase here, and therefore no knowing wink directed at the reader. Instead, the old phrases slide into the new, and the fit is perfect.

All that happens to the syntax as Paterson progresses towards Orpheus is a process of tiny, critical refinements. Sentences flex and embrace more and more, as Paterson’s work attains ever lovelier syntactic complexity. Letting you carry idea upon idea at the same moment, his sentences nonetheless do not make you suffer under their weight. Like a gifted ballerina, these phrases know how to hold themselves so that they become light enough to lift:

I carefully arrange a chain of nips

in a big fairy ring; in each square glass

the tincture of a failed geography,

its dwindled burns and woodlands, whin fires, heather,

the sklent of its wind and salty rain,

the love-worn habits of its working-folk,

the waveform of their speech, and by extension

how they sing, make love, or take a joke.

(‘A Private Bottling’)

One sentence, this contains a bouquet of clauses resolving in a soft bass-note rhyme in which the reader carries a place, a people and all the intangible waveforms of their existence—and doesn’t stagger. Quite the opposite: the clauses leap but you hardly hear them land, you just feel the way they earth as a kind of rightness. Dance terms such as ‘ballon’ and ‘line’ spring to mind here for the way the sentence articulates (‘ballon’ being the illusion of weightlessness given when a dancer jumps; ‘line’ being the way a dancer has of making the curve of limbs symmetrical and beguiling to look at). But in fact we are running out of metaphors that get us anywhere close to understanding the enchantment of Paterson’s syntax. There is only one place to go beyond syntax: music.

iii) Metre and music

Syntax, the language-world we inhabit, is full of patterned noise. The patterns we find ourselves in and being used by jar and loop, clank and squeal—for the most part. Perhaps because of the weight of this noise, the music of a poem can strike us so forcefully that the unintelligible world seems momentarily suspended. I could list, now, instance on instance of Paterson’s music. But list them is all I can do. The music of a line is a complex experience, the marriage of more than acoustic pattern, syntactic grace and verbal acuity. It is also what happens when that complex of ideas and harmonies rains into the waveform of the reader’s life—transforming it. The note is struck that sounds an echo. So, receive these samples and let them resonate, as Paterson has.

‘So take my hand and tell me, flesh or tallow.

Which man I am tonight I leave to you.’

‘then swallowed its shout

in the cave of my breast’

‘the vanished trail of your own wake’

‘Silent comrade of the distances.’

Receiving goes many steps beyond reading; words that resonate overstep their borders. So often, these poems step off into ‘the distances’ and reading them means go with the music, chase the echo. If you leave for the distances, you won’t find Paterson, who disappeared from his own poems long ago, but you might find yourself better able to listen –listen completely, as Paterson’s mentor Rilke recommended.

Nichola Deane, 2009

Orwell Special Prize

In 2008 I received the Orwell Special Prize for lifetime achievement in journalism and broadcasting.

Clive James's Blog

- Clive James's profile

- 289 followers