Zara Altair's Blog, page 5

July 22, 2019

Tips to Soar Through Writing

Stay In The Flow To maximize your writing time, follow two guidelines for writing your mystery.

Stay In The Flow To maximize your writing time, follow two guidelines for writing your mystery.Go into the story.

Stay in the flow.

When you go into the story, you visualize the scene - who is there, what they say and do, and the surroundings. Your work is to translate what you visualize into words.

A focus on writing keeps you in the flow. Any distractions that stop the flow slow you down.

Each writer writes at their own pace. You can write faster whatever your pace by avoiding roadblocks that stop your writing.

Preparation gives you the background - characters, story world, setting. The more you know the faster you will write.

8 Tips to Keep Writing When you are ready to write your story, set up your writing space with few distractions. Stay focused on writing. Distractions come in many forms, so to avoid a break in your flow, keep your writing time distraction-free.

Know your characters. Your work in your Character Bible will pay off when you write. You understand your characters and their context in the story.

Use your outline. Your storyline outline keeps you on track. You know what goes in each chapter. All you need to do is write the chapter.

No distractions. Turn off phone, email, and social media. Notify your family and friends that your writing time is private. If you respect your writing time, they will.

Gather your snacks and drinks before you start.

Establish a regular writing time. Developing this habit trains your mind to focus on writing.

Use your outline to research anything you know will be in your scene or chapter. For example, if a weapon will be in this section, look up details before you write.

Create a symbol like four red Xs to mark a place where you need more research. Don’t stop to do the research while you are writing. If you need more details about how forensic accounting or a Glock 9 work, stay with the story. Keep going. Come back to those research spots later.

Don’t self-edit. Leave those comma, hyphen, dash, colon questions for later. Use your spell checker after you have written. Use your check-later symbol for anything you want to check.

You may discover your own personal writing blockers. Recognize them and keep writing.

Train Your Brain Commit to your writing time. The biggest obstacle to blocking your writing flow is you. Your mind will come up with reasons to stop writing. I’ll just take this one phone call or answer this one email. Ignore those temptations.

When you honor your writing time, you strengthen your commitment. And, the more you write, the better you’ll feel about the rewards of progressing toward the end of your mystery.

Some writers create the first draft on paper. They perform their first edit and catch up on those research questions as they enter it on the computer.

Others, write in the morning and edit in the afternoon or evening.

Others, edit what they wrote the day before to get into the story to continue with their writing time for the day. Some do a shortcut to this by ending mid-sentence and picking up at that point in the next writing session.

Experiment with different methods to find the one that works for you.

Each writing session gets you closer to finishing your mystery. The better the flow, the sooner you get to The End.

Zara Altair

Published on July 22, 2019 12:21

July 15, 2019

Mystery Novel Four-Act Structure Demystified

Build Your Story Around the Main Events

Build Your Story Around the Main Events Between a full scene-by-scene, chapter-by-chapter outline and writing with no structure is a middle ground. When you understand the four-act structure, you give yourself the freedom to create your story around the main events in each act.

It’s easy for beginning writers to get lost in three acts — beginning, middle, and end. The four-act structure and the main events of each act give you a framework like tent poles you use to drape the fabric of your story.

When you know the structure, it’s easy to keep the main events in your head as you write. Each event is a destination and at each destination, the story changes.

Change builds tension. Tension keeps readers turning pages.

You have your detective and the murder and possibly the villain. Now it’s time to think story. Act One - Setup and Complicate The beginning is about bringing your reader into the story. In a mystery, you introduce them to your sleuth and, usually, the murder.

One of the best ways to introduce your sleuth is to show him solving a problem. Tell your readers, your sleuth can do what she’ll need to do to find the murderer. Illustrate at least one of your sleuth’s strengths you’ve created in your character background. If you know how he will catch the villain, mirror that talent in the beginning.

You introduce your reader to your sleuth and their everyday world by showing how he acts when faced with a problem. You are going to throwing a lot of problems her way, so highlight her skills at the beginning.

Once your reader knows your sleuth and sees them in action. Something happens that triggers your story.

The Inciting Incident

Once your reader has a taste of your sleuth, bring them into the main problem of the story. Move your sleuth out of their everyday world into a new challenge. In this scene, present your sleuth with a challenge he didn’t see coming.

Something happens that pulls your sleuth toward the main mystery. It could be a new neighbor, an old lover, a vehicle breakdown, or anything you want to imagine. Although you sleuth (and your reader) doesn’t know it yet, this small disturbance in her regular life is heading her toward the big mystery.

Once you introduce this event and show your sleuth’s reaction(s), it’s time to get to meet the mystery head on.

The First Plot Point

Now you introduce the dramatic event that must be answered in the climax of your story. In a mystery, the sleuth is brought on or volunteers to find the killer.

How this event unfolds will depend on the type of mystery you write. A cozy heroine may take on the search or a cop may be up next on the rota. Either way, your sleuth protagonist enters the mystery and takes on the challenge of solving the puzzle.

Act Two - Conflict and Rising Action in Discovery Now your sleuth must poke and probe to learn about the victim and the murder. He examines physical evidence and discovers a list of possible suspects. In this section of your mystery, your sleuth gets to know the victim’s world—what the victim did, who was in the victim’s world, why the victim was where they were when they were murdered.

This is the place where you introduce any subplots. The sidekick has a problem. Your sleuth meets a love interest. Outside forces put pressure on your sleuth. More juicy complications.

Pinch Point

Along the way, things don’t go smoothly. A piece of evidence is lostor your sleuth misinterprets (for now) the significance. As he meets suspects, they have their own personal reasons for resisting and not fully cooperating. Challenge your sleuth at the pinch point. Whatever he thinks is the right approach doesn’t work.

Your sleuth is nowhere near discovering who the killer is. During this discovery phase, throw in as many complications as you can. Make each complication more challenging than the last. More complications mean more tension and more tension keeps readers guessing and turning pages.

The Midpoint

The midpoint comes between Act Two and Act Three. The story pivots. Your sleuth may discover that she’s been going down the wrong path and has to rethink everything. He may be so discouraged he thinks about giving up.

Act Three - Crisis After the midpoint, your sleuth looks for a new approach to solving the puzzle and it doesn’t go well. Your sleuth must reexamine everything he learned in Act Two.

Add complications and twists to the subplot(s) here.

Pinch Point

The second pinch point shows your sleuth that the new direction he chose after the midpoint will not get her the results she wants. The undiscovered villain may set a trap that confuses your sleuth. Your sleuth realizes he’s in over his head.

Now your sleuth must gather forces. She may find new support, discover new evidence, and somehow get closer to discovering the murderer. Your sleuth examines all the old evidence with new information and a fresh approach. He’s looking for the evidence or suspect statement he overlooked before.

Now on a new discovery path, your sleuth feels she’s closer to the killer.

Plot Point

The killer antagonise uses a smokescreen and everything the sleuth thought he knew leads nowhere. Your sleuth needs to clear his vision of the victim’s world and take a new approach.

Act Four - Climax and Wrap Up Your detective is captured or blocked from finding the killer. The victim’s world becomes more of a mystery. She’s just not seeing anything the right way. If she’s trapped/captured, there’s no way out.

Rising Conflict

But then, your sleuth sees a way out. After the escape from the trap or block, he starts rethinking and gets a glimpse of who the killer might be. But, there’s still something that isn’t clear. He gets ready to confront the killer, but there’s one last defeat, and it’s the biggest of all.

Your detective knows the killer is dodging but can’t get to that final confrontation. For the moment, the killer survives any accusation.

Your detective finally finds the killer. But the killer has a surprise for the detective. Your detective may have made a false assumption or misread the killer’s intent. The killer pulls out one last trump card, one the detective didn’t expect. Whether it’s a battle of wits or hand to hand fighting, the killer plays that one last card.

In Act Four, you pull out all the stops. The confrontations and reversals are the most challenging in your mystery. The villain has the upper hand. Except…

Your detective finally realizes how to confront the villain and challenges him face to face. At this point, your sleuth reveals the murderer. In addition, your sleuth shines the spotlight on her special skill(s) that led her to this final confrontation and revelation.

In the midst of all this rising action, bring each subplot to conclusion, because once your sleuth reveals the killer, you’ve finished your unwritten agreement with your reader to solve the puzzle.

Revelation and Wrap Up

Once your sleuth has revealed the villain, wrap up your mystery. When the killer is revealed, bring your story to a quick conclusion.

The Framework The four-act structure gives you the freedom to write without a commitment to each scene while keeping in mind the important steps of your story.

Some writers find it helpful to sketch out the major story points.

Inciting incident

First plot point

Pinch point

Midpoint

Pinch point

Climax

After they note these major story points, all the chapters in between flow toward the next story point. As they write, they have a goal in mind: to get to the next story point.

Other writers keep those major story points in their head and just write.

It’s up to you how you want to put together your story structure. Beginning writers find that having the major story points in mind keeps them from writing themselves into a corner or going off track.

Image by JamesDeMers

from Pixabay

Published on July 15, 2019 12:27

July 8, 2019

Background Research for Your Mystery

Research Before You Write The Story The first round of research is background material for your story. You may look for settings, hidden alleys, a great beach. Murder weapons or poison. The psychology of being a mistress. How to clean a Glock. Pharmaceutical drug research lab procedures.

Research Before You Write The Story The first round of research is background material for your story. You may look for settings, hidden alleys, a great beach. Murder weapons or poison. The psychology of being a mistress. How to clean a Glock. Pharmaceutical drug research lab procedures. Base your research requirements on your story premise.

Gather Broad-base Details The aim of the first research is to discover background that will enrich the story for your readers. You are in discovery mode. When you find details, store them away. For beginning writers, know that 80% of your research will not show up in your story. The reverse of this that when you want a detail, you will have material to enliven your characters and enrich scenes.

Feet On the Ground While an online search, will give you generic information, there's nothing like going to the place of your story.

What You Need

It doesn’t take much to explore your story’s location. You’ll need:An open mind to find settingsA camera to record your discoveries. Most mobile devices have a camera capable of capturing what you need without the expense or weight of a camera.A notebook to record impressions, sounds, smells, and other sensory details, plus any scene ideas prompted by the location.You will discover details that no amount of online searching will offer.what your character(s) know and don't knowroute shortcuts that may offer surprises for your actioninterior details of buildings, rooms, grand halls, and back kitchensWord of mouth can give you new resources and introduce you to specialists. As you meet people and tell them why you are visiting, you'll be surprised at how people help you with your background research. They'll refer you to others. You should talk to my neighbor. He was here in the 50s, has a passion for hand weapons, grows herbs, knows all the bars. They will offer details you would never have considered on your ownThey'll do research for you, offering magazine articles or websites that address specifics of your storyYou'll taste authentic food different from the food in your homeFind surprises from being there Online Resources Google is a great place to start. But sometimes you need more detail or scholarly background.

Google Scholar gives you access to articles, book excerpts, and abstracts that won’t display in regular search results.

If you can’t get your feet on the ground, Google Earth displays very detailed images of cities and towns. Plug in a zip code or city, to search a certain area.

Need a mansion for a rich villain or a humble condo for your sleuth? Try Redfin. Images of exterior and interiors are yours for the asking. Be sure to save your images to your Research folder. These properties sell.

Books and Print Materials Build a personal reference collection of books you can grab to enhance your overall knowledge and gather specific details. What's What, by David Fisher and Reginald Bragoneir

, Jr. This is a visual encyclopedia of almost everything you can imagine: refrigerators, steamships, handguns, saddles, woodstoves, stagecoaches, cameras, everything. It gives you a drawing of the item and identifies all its pieces and parts. (An alternative: The Ultimate Visual Dictionary, by DK Publishing.)The Crime Writer's Reference Guide, by Martin Roth. A great writer’s resource. Crime Fiction and the Law. A collection of articles by various experts.Making Crime Pay: The Writer’s Guide to Criminal Procedure by Andrea Campbell.Forensics and Fiction by D. P. Lyle.Forensics for Dummies also by Lyle.FBI Handbook of Crime Scene Forensics compiled by the U.S. Department of Justice.Practical Homicide Investigation: Tactics, Procedures and Forensic Techniques by Vernon J. Geberth.Writer's Detective Handbook: Criminal Investigation for Authors and Screenwriters by B. Adam Richardson

As you search for just the right answers you may collect details from many sources: travel brochures, firearm manuals, used bookstores, government websites, maps, documentaries, medical journals, guidebooks, news broadcasts, trade magazines, public trials, almanacs, memoirs, regional histories, and other discoveries you find.

Guidelines for Research Research can lead you down rabbit holes. You could spend years doing research. Your main goal is to write the story.

Beginning writers can feel that they don’t know enough. You can get trapped in an endless search for more information. Gather basic information and then start writing.

Because you won’t use 80% of the research you’ve done, the best approach is to begin your story.

Let the Story Guide the Research No matter how much research you do, as you are writing you’ll discover details you want to know. Rather than trying to know everything before you start, do your general background research, then let the story guide the details you need.

As you write, you’ll discover needs you had not imagined. So, instead of attempting to get everything you need, collect general background. The story will tell you the specific details you need.

Zara Altair

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

Published on July 08, 2019 13:26

July 1, 2019

Mystery Character Secrets and Lies

Character Dimensionality Mystery is all about puzzle. Deeper characters provide more puzzling challenges to your sleuth. Your sleuth is challenged

Character Dimensionality Mystery is all about puzzle. Deeper characters provide more puzzling challenges to your sleuth. Your sleuth is challengedby the obstacles the other characters throw his way. One of the best ways to create a puzzle for your sleuth is to give each character a secret and a lie. Or more than one.

Secrets and the lies characters use to preserve the secret add a human dimension to characters. Whether it’s the villain or a suspect each character has things they don’t want others to know.

Your sleuth is challenged by diving through the lies to get to the truth that lies underneath. Ultimately, he must separate the various truths to get to the one that reveals the killer.

How to Create the Secret As you create background details for each character in your character bible, add two sections. One for the secret and one for the lies the character tells to hide the secret.

Along with the character’s context in the story, his ability to lie to hide a personal secret is a device you can use to confound your sleuth.

The lie doesn’t have to be about the murder. It can be anything that particular character wants to hide from public knowledge. An affair, a gambling habit, a fear of public speaking are all fair game.

You’ll need to know about your character’s personality and their role in the story to come up with a suitable lie that fits the character. Creating a strong character background is essential to create a believable lie that fits the character.

I like to think of it as casting the best characters possible to make the story work.

The Two Lies Each Character Tells Once you identify the character’s secret, you need to devise the lies he tells to cover up the secret. The lies are at two different levels.

Everyday lie. As long as the character has kept the secret, she’s used a standard cover up to keep the lie hidden. The trip to the corner shop to cover a stop off at the betting parlor. Evening walks to cover a clandestine tryst. This lie rolls off her tongue because she uses it consistently to hide her secret.Under pressure lie. When someone questions the everyday lie, your character has a deeper lie to preserve the secret. It may start to get convoluted or vague, but she’s determined not to give up the secret. Add more (false) details to the basic everyday lie. The cute little dog she met on the way to the corner store. How the bluebells were blooming in the forest on the walk. The under-pressure lie is usedto preserve the basic lie by elaborating with false details.

You can add another layer or two of lies, especially if the character is a main suspect. Your sleuth will keep pushing, and you want those defenses ready.

Humanize Your Characters Everyone has secrets they want to keep hidden. Adding secrets and lies to your characters gives them depth as characters in your mystery as well as

obstacles for your sleuth.

Zara Altair

Photo by Alexandru Zdrobău on Unsplash

Published on July 01, 2019 13:34

June 24, 2019

Get Your Cop Right

Derek Pacifico conducting Homicide School for Writers Real Cop Details in Your Fictional World Unless you have worked in law enforcement, writing realistic cops for your mystery involves getting to know law, law enforcement procedures, and a realistic picture of how cops think, act, and work.

Derek Pacifico conducting Homicide School for Writers Real Cop Details in Your Fictional World Unless you have worked in law enforcement, writing realistic cops for your mystery involves getting to know law, law enforcement procedures, and a realistic picture of how cops think, act, and work. Reading and online research will give you a general background on how cops operate on a daily basis

.

Knowing a law enforcement officer who is willing to share details about procedures, daily life, worst case scenarios and the like

is gold. Connect with your local law enforcement agency to find a resource. It may take some doing because cops are busy. Perhaps someone on the team can refer you to a recently retired detective who has more available time.

You’ll be on your way to verisimilitude that engages readers and doesn’t get your book tossed because of inaccurate details.

Procedures You may love noir loners who go against all odds and the bad guys, but real cops work as a team and call in professional teams for various aspects of an investigation. You’ll need to know who does what where your fictional cop is located

.

Procedures vary from big city locations with many personnel

to small town cops who may call in the local sheriff’s department for crime scene details.

Teams that may interact with your fictional cop:

Crime scene specialistsForensics laboratoryCoroner or Medical Examiner

Wherever your detective is located, make sure he is surrounded

by the right colleagues.

Writer Resources from Real Cops Some cops are willing to share their experience with writers. The following three cops have years of experience and the willingness toshare their knowledge with writers.

B. Adam Richardson a police detective does a lot to actively support

writers in getting their facts right from cop lingo to procedures and jurisdiction. Find him at Writer’s Detective Bureau a podcast with the same name, an email newsletter Writer's Detective APB, and a very active FaceBook group Writer's Detective Q&A community where you can join with other writers to answer questions.

Lee Lofland conducts the Writers’ Police Academy as well as

his website The Graveyard Shift. And, a group to ask specific questions Crimescenewriter2@groups.io.

Police chief and retired homicide detective Derek Pacifico taught interview and interrogation techniques to law enforcement personnel world wide. He offers a course for writers on how to do the same. Writing Fictional Police Interrogations. His book Writers’ Guide to Homicide gives background and provides insights into what cops do when faced with legal parameters.

The forums and Facebook groups are places for you to get specific answers to details you want to include in your story. Responses come from other law enforcement folks, forensic scientists, and other professionals related to solving crime.

Resources like Derek Pacifico will read chapters and passages from your story to ensure you are representing a true-to-life scenario.

First Hand Research Real cops are the backbone of getting your details right when it comes to writing about cops. You’ll avoid mistakes like having a cop share investigative details with your cozy mystery heroine.

Every novel takes background research. Mysteries often involve cops as well as civilians. Do the background research to make your story realistic and believable. Your readers will appreciate the work you do.

Zara Altair

Published on June 24, 2019 20:47

June 13, 2019

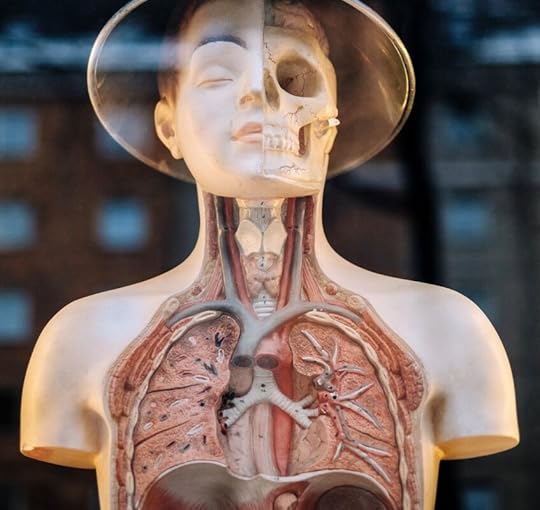

Get Inside Your Character’s Body

Photo by Samuel Zeller on Unsplash

Photo by Samuel Zeller on UnsplashBody Details to Improve Your Story Most writers don’t think of anatomy and physiology when they are creating a story, but you can enhance reader engagement with body part details. If you find your characters all nodding in agreement or sighing in resignation, try expanding your view of the character.

Every emotion sets off physical responses in the body. You can use the details of these responses to enrich your story.

The next time a character has a response, think of their whole body from head to toe. What are their hands doing? How are they breathing? What is their body position? Use one of those responses in your story.

Many writers act out a scene to get a better feel for how characters feel. You may feel self-conscious the first time you try, but putting yourself in your characters’ roles and physically acting out a scene gives you details you wouldn’t think of typing on your computer. Your Head-to-Toe Checklist Think about every part of your character’s body to create detailed reactions. You be on your way to creating vibrant and complex characters. You’ll make your characters knowable to the reader and the details create empathy. They’ll know when your sleuth has a worthy opponent and when a suspect is lying. And, they’ll know your sleuth’s reactions to those characters.

Each time you need to create action between characters give each character a body review. Here’s a list to help you go from top to bottom.

Head Hair Scalp Brain Forehead TemplesEyebrows Eyelids EyesNose Cheeks EarsLips Mouth Tongue Teeth Jaw Chin Face Neck Throat Voice Shoulders Torso Chest Heart Lungs Stomach Back Bottom Arms Hands Fingers Legs Feet Toes Skin Veins Muscles Bones List source; Valerie Howard books.

The reactions you use for each character depends on the point of view (POV) in the scene. Your sleuth can’t know what’s going on internally - brain, stomach - but she can use her powers of observation to note other physical reactions.

Breathe Life Into Your Characters Readers identify with physical reactions. They understand because they experience these reactions themselves. Tie the physical reactions to emotions bring characters alive.

Seasoned writers use this technique as they write. Beginning writers may focus on these bodily reactions during editing. In the speed of just getting it written you may write He nodded. During editing you have time to expand the physical reactions.

Two handbooks can help you work with these details:

The Emotion Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide To Character Expression by Angela Ackerman and Becca Publisi

. 1,000 Character Reactions from Head to Toe by Valerie Howard.

Both books are available in both digital and print format. They are both great reference guides when writing character reactions. Add them to your library.

Realistic detail brings your characters alive for your readers. Use one or two examples for each reaction (don’t overload your reader) to keep them engaged, sympathetic, and turning pages.

Zara Altair

Published on June 13, 2019 20:46

June 5, 2019

How To Get the Most Impact From Your Setting

Photo by Joao Tzanno on Unsplash

Photo by Joao Tzanno on UnsplashGive Your Reader a Sense of Place Setting is more than a backdrop for a story. A backdrop is a painted cloth hung at the back of the stage to create the appearance of a larger scene on stage. In a novel, you have room to bring your setting to life by placing your characters in the scene and interacting with the world around them.

Setting gives readers a sense of place. The more you integrate the setting the deeper connection you build with your reader. Your story makes them feel as if they are there. As you integrate physical details of the setting into the story, your reader empathizes with your characters, especially your sleuth.

Rather than a paragraph explaining (telling) the setting, scatter setting details throughout a scene. Use the five senses - taste, smell, touch, hearing, sight - to get your reader feeling the setting.

Here are four ways to get those details into a scene without a long descriptive passage.

Mood How many television mysteries have you seen with a full moon at night shining through tree branches? Bang! You know it’s a mystery. This image is overused so I don’t recommend the full moon through tree branches. But, you can set the mood of threat, with dark spaces like the woods, a dank basement, or even the proverbial graveyard. A quick sentence can set the mood without slowing down your reader with a long, descriptive passage.

Physical When your sleuth reacts to the setting, you build empathy for your reader. Get your sleuth and characters react to the physical details through sensory imagery. When you use these details, setting becomes like another character in your story influencing character actions. Jane Harper used these details effectively in her debut mystery, The Dry. And James Lee Burke’s characters interact with the Louisiana bayous and New Orleans city streets in his Dave Robicheaux series, beginning with his first mystery, The Neon Rain.

Emotional Setting can set off emotions in your characters. Frustration in the cold, lethargy in the heat, discomfort in a sterile room with no personal touches and other emotional responses to the setting can cloud your sleuth’s reasoning missing important clues that appear later as signals to the villain.

Obstacle Generator Setting is a treasure trove of obstacles for your sleuth to overcome. From tripping in a messy room just when she needs to confront the villain to fainting in the heat, your setting details mess up your sleuth’s life. They are useful in scenes that need an obstacle to raise tension.

Use Setting Details Specifics make your story come alive. It doesn’t matter where you place your story. Your hometown, a far-away exotic location, an historical country manor, a big city all have the ingredients your need to let setting add impact. Michael Connelly sets Harry Bosch in L.A. Place names, street names, sounds, and tastes all add to making the city of Los Angeles part of each story.

Your challenge as a writer is to illustrate the details that impact your characters. Show emotional depth when your protagonist love the sunset over the mountains/plains/coastline. Place a chase scene on a crowded highway with a soccer mom with an SUV full of kids impeding your sleuth’s high-speed chase. Hide a clue in the detritus on the forest floor. When your sleuth interacts with the environment, you give your reader a sense of place.

Zara Altair

Published on June 05, 2019 20:08

May 30, 2019

Read to Write

Why Read? You read long before you started writing. You probably started writing because you are a reader.

Why Read? You read long before you started writing. You probably started writing because you are a reader. Jane Friedman, writing and publishing coach/blogger underscores reading as the basis for good writing:

Establish a reading habit that matches roughly what you hope to write and publish. Make it as important as anything else you schedule in your day,As your writing practice develops, you’ll read with a critical eye. On the first read, you notice various places in the story. Ah, what great dialogue! Here’s where the plot turns. I’m feeling this character’s pain.

and never allow busyness to crowd out the time you devote to consuming other good works.

What You Learn Reading Without consciously noticing or reflecting, you learn a lot about story just from reading. If you apply a critical eye, you’ll start to balk at things that don’t work for you as a reader and examine what bothers you.

For me, re-reading helps me focus on craft details. The first read is for the sense of story flow. The second reading is much more critical. I’ll stop to take notes.

Story arc. How does the story start? What challenges happen in the long middle? When does the plot twist? Story structure. The beginning, the first plot point, the middle, the obstacles, the conclusion. A quick way to master story structure is to watch a lot of mysteries - movies and TV series episodes. Tension. Does every scene have tension? If so what is it? How does the tension build as the story progresses?Character development. How many characters are in the story? How are they introduced? What details does the author use to introduce a character? How does the author build on the details? Does each character have an arc? Only some characters? Why? Does it work? How does each character fit in the story?Conclusion. Is it satisfying? Why? Do you still like the protagonist? Are the loose ends gathered in and tied up? If not, does it matter to you? Was it a surprise? If not, why not? This is especially important for mystery stories.Scene. How does each scene move the story forward? Is each scene a mini-story? Would you write your scene similarly, or use a different technique? Tone. How does the writer set the tone? Is it dark? Playful? Serious? Do you like the tone? Does it fit the story? Why?Style. Do you keep reading, even if you are tired or have an appointment? Do the words flow? Are the sentences staccato or leisurely? Does the style add to the story? Why?Satisfaction. What elements did you as a reader enjoy? When did you want to skip passages? Do you want your story to meet or exceed in reader satisfaction? As a writer, satisfaction is a strong element to review because you want your readers to be satisfied with your story.

How You Benefit from Reading The deeper you delve into your writing craft, the more details you notice as you read. The compilation of knowledge you gain reading grows over time. You’ll find your writing improves and even during the writing process you’ll have a sense of what works in your story.

Gain the most benefit from reading by diversifying. Reading in your genre will up your game. But the lessons you learn reading

outside your genre are just as beneficial because you will incorporate your sense of storytelling into your own writing.

Zara Altair

Photo by Ben White on Unsplash

Published on May 30, 2019 21:55

May 23, 2019

Cast Your Characters

Why Casting Your Characters Helps Your Mystery To make your character function in your story world, you need to create details that set each one apart from the others. While the most important feature of your character in the story is the context, how they serve the story, help your readers identify each character with details.

Why Casting Your Characters Helps Your Mystery To make your character function in your story world, you need to create details that set each one apart from the others. While the most important feature of your character in the story is the context, how they serve the story, help your readers identify each character with details. How they dressHow they speakTheir voiceTheir speech patternsUnique quirks Individual physical traits

Thriller writer Dana Haynes recently spoke at my local Sisters in Crime chapter. He advised something I’ve been doing for years, “Cast your characters.” Use film actors and personalities to embody your character as you write. It doesn’t matter if they are living. What you want is the sense of how they move and speak.

I cast footballer Ádám Bogdán as one of Argolicus’ bodyguards, in my present work in progress The Grain Merchant. I wanted the energy and fierceness always in my head when writing.

Character Traits You can differentiate your characters with distinct character traits. It’s OK to borrow from those famous people. Use your character Bible to keep notes so when you bring a character back after 50 pages, you know the details.

Character Traits You can differentiate your characters with distinct character traits. It’s OK to borrow from those famous people. Use your character Bible to keep notes so when you bring a character back after 50 pages, you know the details. Create a background for each one of your characters. Some writers use a binder, others use built in character notes from software like Scrivener or StoryShop. Whatever tool you choose, enumerate the character traits that differentiate the character to make them memorable for your reader.

You’ll guide your readers through the maze of characters you create with specific details. If a character gets left behind for 50 pages, one outstanding detail will refresh your reader’s memory.

Borrow freely from your actor. As well as physical and personality traits, your actor may inspire the perfect secret and the lies your character constructs to make them a suspicious suspect.

The actor’s voice and speech patterns will help you write dialogue unique to each character.

When you cast each character, you’ll have an immediate fix on their personality as you write. You’ll have a red head with attitude, a debonair ex-husband, or a sultry, pouting mistress. (Lucille Ball, Cary Grant, Gloria Graham.) Your Casting Call Once you have your character’s context in the story, start searching for your cast.

If you already have an actor in mind, gather some images and put them in your character Bible. If you need to get a better fix on a character, perform an online search with terms like sex, age, and hair color. A broad search will give you plenty of results. Narrow your choices down to one or possibly two.

This selection process helps you understand your character, because from the wide range of choices, you’ll see that many don’t fit. And, you’ll discover that an actor you hadn’t thought about, is just the right persona.

Both the search and the final choice will help you write a character that readers remember.

Zara Altair

Published on May 23, 2019 17:39

May 16, 2019

Create The Puzzle For Your Reader to Solve

No Mystery Without a Puzzle

No Mystery Without a Puzzle Mystery readers love a puzzle. More than

one is more enticing. While your developed detective leads the reader on discovery search, the puzzle is the draw of a mystery.

All the work you do in developing your characters, creating suspects, and planting clues has one aim to create a mystery. Giving away too much at the beginning spoils the tension. Readers will tolerate backstory, a love interest subplot, and even descriptive setting passages, but without the puzzle, there’s no mystery.

The Set Up Your sleuth is the reader’s guide through the story. Creating a detective with quirks and strengths invites your reader into the story. The reader expects the detective to solve the mystery at the end, but not until the end. A solid introduction to how your sleuth works initiates reader trust that their guide has what it takes to collect the puzzle pieces and put them in place.

The murder victim is the key to the mystery. As the detective learns more about the victim and the victim’s world the reader follows along anxious to see how things develop. They are eager for clues and suspects to confound them and your sleuth.

The last part of the setup is when your sleuth takes on solving the mystery to uncover the villainous murderer.

The Discovery Once your sleuth takes on the case, you set the puzzle pieces in place. What evidence and clues are at the scene? How was the victim killed?

Then, your sleuth enters the victim’s world. He uncovers the victim’s friends, loved ones, and enemies. Each of these characters sheds new light on the victim’s life. The reader learns from each of the suspects a bit more about the victim. The victim’s likes and dislikes, their shortcomings, and their secrets are revealed as suspects contribute to painting a picture for the sleuth and your reader.

The sleuth and your reader begin to form an opinion of the victim and possible reasons the victim brought on their own death.

Toward the middle of your mystery your sleuth and your reader discover that they didn’t have a full picture. A midpoint event illustrates how wrong those first assessments were.

On The Hunt Everything seemed to go along in the discovery until the big obstacle pointed out the sleuth did not have all the facts, was headed in the wrong direction, and needed to rethink everything.

Once your sleuth reconsiders all the facts, evidence, and statements, she must find a new direction to unveil the killer. Without reversals and twists your reader will feel your story is episodic and is not creating the puzzle they crave.

This is the point where a beginning writer often lose the puzzle thread. They know the villain and the suspects and want to lead the sleuth and the reader to the revelation. But it’s much too soon in the story sequence. And it’s the reason both writers and readers complain about a sagging middle. But mystery writers have no reason to sag.

Whether you call it the last part of Act II or Act III, in a mystery the hunt section is the place where tension builds, your sleuth is overrun

with false starts and obstacles, and the villain confounds your sleuth’s search.

The Revelation Before you get to the revelation, give the antagonist one challenging twist. Your reader knows they are coming to the end, create more mystery with one last big challenge for your sleuth.

Tie up any loose ends or subplots, then the final reveal. All mystery leads to this moment.

Zara Altair

Photo by Tim Johnson on Unsplash

Published on May 16, 2019 13:15