Martin Jones's Blog, page 7

January 14, 2024

The Bee Sting by Paul Murray – a Bee Sting and a Dog’s Life

The Bee Sting is a novel by Paul Murray, shortlisted for the 2023 Booker Prize. Set mostly in a small Irish town not far from Dublin, it unravels the tangled history of the Barnes family, who have enjoyed decades of wealth and local influence, thanks to their VW dealership. Now, leaner times have arrived.

There is much looking to the past in The Bee Sting, and I’ll start with some personal nostalgia the book provoked in me. Believe it or not this involves the TV show Friends. Fairly early in my read through, I recalled the moment where Monica, squeakily indignant about something or other, causes Chandler to advise her, ‘only dogs can hear you now’.

Let me explain.

We begin in the present day, focusing on teenager Cass Barnes and her relationship dramas. For a few months, she has a boyfriend called Rowan, who, though no Oscar Wilde, does occasionally come out with some interesting facts. One of his observations involves dogs and their sense of smell. Dogs have a hugely better sense of smell than humans, which, as Rowan points out, would make their perception of past and future different to ours.

‘They must have a whole different understanding of time, because for them the past is literally still around. When a dog looks at the world it must see all these presences gradually fading out. Like a sky full of contrails.’

You could say the perspective of The Bee Sting is like that of Rowan’s dogs. In fittingly freeform writing which might lack full stops, or muddle together first, second and third person narration, things do not simply start and finish. Past hurts linger, hidden aspects of personality re-emerge, eccentric ladies with psychic abilities see events in advance, like a dog picking up a scent long before their human owners are aware of anything.

I pondered on this doggy outlook. Rowan thinks it’s a good thing, because from a scent-centric point of view, the nice times in our lives tend to stay with us for longer. There are also suggestions throughout the book that looser perception might make us more tolerant and collaborative. I thought this an interesting idea, but I did have some reservations. If you are taking dogs as a model, then forgive me if I come over as a canine pedantic, but they are pack animals just like humans. Their floaty, nasal insights don’t stop them snarling at each other and engaging in doggy violence. A lost owner is lost, even if their scent lingers. A bereft dog is still bereft. And as for the suggestion that thinking in terms of the olfactory, might give a pointer towards more openness and collaboration, well there’s the irony that a dog’s sense of smell is often involved in territorial marking. Picky? What can I tell you. The dog thing, which serves as a template for much of The Bee Sting, didn’t quite work for me.

Still I got the point. And there’s also the fact that dog perception isn’t simply held up as a standard we humans should aim for. When psychic Rose foresees bad things happening, these premonitions are characteristically marked by the appearance of a ferocious-looking black dog. Dogs are presented as ambivalent, both helpful and frightening. Maybe The Bee Sting, in the way of good novels, is not writing some kind of prescription for how we should see the world. It’s more a picture to be looked at from different angles. Seeing things in less defined terms is useful, until the potential for confusion brings its own problems.

I started out wondering if this was a book with a message that only dogs could hear, but ended up feeling that The Bee Sting could find an appreciative human audience. Though its central idea might be a bit of a stretch, generally speaking it’s a woof from me

December 30, 2023

The Shipping News by Annie Proulx – Trying to Find a Good Story

The Shipping News by Annie Proulx, is a Pulitzer Prize winning novel, published in 1993. Set initially in a small New York State town, it tells the story of Quoyle, a young man struggling to make a living as a reporter at the Mockingburg Record. Quoyle’s life is beset by a series of disasters – the suicide of his uncaring parents, marriage to a sociopathic woman who tries to sell their young daughters, before she dies in a car crash while fleeing to Florida with her latest boyfriend. Quoyle is used to enduring bad treatment, but even he is reeling. An aunt persuades him to make a new start in Newfoundland, ancestral home of the Quoyle family. He gets a job with The Gammy Bird, a local Newfoundland paper, writing up car crashes and shipping news. On this shaky basis, a better life begins to come together in a harsh but beautiful place.

Summarised like this, the events of Quoyle’s life sound gothically newsworthy, the sort of thing his newspaper bosses would love. To the man himself, he simply endures a series of horrible setbacks. Quoyle doesn’t have the confidence to believe his life deserves attention. And yet here we are reading about him. Will he come to believe that his story has value?

Settling in Newfoundland, Quoyle tries to get along. He covers a few dramatic stories, while personally leading a quiet life, looking after the children, renovating houses, going to the occasional riotous party, meeting Wavey, a young woman who seems to like him.

Quoyle’s life back in Mockingburg had been the stuff of tabloid headlines. His girlfriend has herself escaped a potentially tabloid headline-grabbing relationship. Really their joint achievement in the end is not to become noteworthy in those garish terms, but to finally believe that they are both deserving of happiness. They don’t become the sort of people who might apparently be written about – but who wants that? Their non-story is better.

The Shipping News is a beautifully written novel, with much to say about the complex way stories work in our lives. In many ways we see the dark side of stories, the way they exaggerate, distort, and focus on the worst of humanity. But there is also a sense for the truth hidden in stories. For example, an imaginary white dog terrorises Quoyle’s daughter Bunny, appearing in her dreams, or in the shape of some random object she sees. Bunny makes drama out of nothing. And yet it is characteristic of The Shipping News that real and imaginary drama are hard to tell apart. Imaginary dogs take on something like reality when old Bill Pretty describes to Quoyle a myth linked to a dangerous rock on the Newfoundland coast, called the Komatik Dog.

“You come at it just right it looks for all the world like a big sled dog on the water, his head up looking around. They used to say that he was waiting for a wreck, that he’d come to life and swim out and swallow up the poor drowning people.”

While the story of the Komatik Dog is as fanciful as Bunny’s imaginary white dog, it reflects the real possibility of shipwreck. Silly, melodramatic stories need not be nonsense. They can hold a truth we would be wise to heed.

December 23, 2023

The Chemical History of a Candle by Michael Faraday – Christmas Illumination

During the Christmas holidays of 1825, the Royal Institution organised a short programme of science lectures for young people. This became an annual event, which continues today. For the 1848 season, Michael Faraday gave a series of six talks called The Chemical History of a Candle. They were published in book form in 1861, soon after Faraday had repeated the series for Christmas 1860.

Ernest Hemingway once said that someone starting a book should write down the truest sentence they know and work out from there. In this beguiling series of lectures, with visual illustration from experiments involving heat, cold, balloons, explosion and implosion, Faraday explores the physics and chemistry of a candle, which he presents as a tiny model for more general processes. In effect, he follows Hemingway’s advice, taking a candle as the truest of things and working outwards. I now know that candle wax is what’s called a hydrocarbon, a substance consisting of hydrogen and carbon in combination. Lighting a candle wick causes the wax to melt and vaporise into a hot gas. This causes the hydrocarbons to start breaking down into their constituent parts of hydrogen and carbon, which are drawn up into the flame. Here they combine with oxygen in the air to produce water (hydrogen and oxygen) and carbon dioxide (carbon and oxygen). Candle combustion is basically the same as any combustion anywhere, including that driving life. As I write this review, and as you read it, we breath in atmospheric oxygen to fan our metabolic flame, breaking down food hydrocarbons to produce energy and heat, with water vapour and carbon dioxide as by-products, which we breathe out.

Faraday takes apart the process of candle burning, and the products that result, demonstrating many clever techniques of division. Fascinatingly though, Faraday’s doesn’t simply take things apart, but also shows them acting together as a whole. For example, he makes reference to nitrogen in the atmosphere, an abundant gas that actually suppresses burning. How does a fire suppressant gas contribute to the process of combustion? Well, an atmosphere of oxygen alone would produce an explosive, tinderbox world. Nitrogen alone would make it impossible to support the combustion that supports life. An atmosphere of oxygen existing alongside a larger proportion of nitrogen, allows a candle to burn in a controlled way for hours. I found myself considering life in these terms. There are many circumstances holding us back from shining our various lights, more problems than solutions no doubt. Although nitrogen is the dominant gas, in combination with a little oxygen, we have the chance to burn with a steady flame.

The lectures do invite this sort of thinking, the penultimate lecture encouraging the audience to consider themselves as candles and spread some illumination around.

This book was a delightful surprise. It turns out that a candle is one of the truest things I know.

December 14, 2023

Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon – Turning the Last Page Before the First

Gravity’s Rainbow is Thomas Pynchon’s 1973 novel, set in the final months, and immediate aftermath, of World War Two. It centres on Germany’s V-2 rocket programme, and a quest by a group of central characters to find a secret device, planned for a special version of the rocket.

The V-2 was a shockingly powerful innovation, the forerunner of all rockets we see today launching people and hardware into space. As one of the first man-made objects ever to break the sound barrier, the V-2 moved so fast that someone witnessing its impact saw an explosion first, followed by the sound of the rocket falling. Seemingly arriving ahead of itself, the V-2 blurred the difference between past and future, and so began to tear apart the foundations of what we complacently assumed was stable reality. The book’s initial confusion of past and future spreads out to include good and bad, madness and sanity, seriousness and levity, inside and outside. You name some form of organisation, it will fall apart in Gravity’s Rainbow. The psychologist Karl Jung – mentioned in the book – thought there was a shared unconscious which we enter in our dreams, where all the polite categories of waking life fall away. In the world of Gravity’s Rainbow this chaotic dream realm actually mimics real life, where Germany lies in ruins, its borders meaning nothing as troops of many nationalities mill about a wrecked wasteland. Berlin’s population live together in the open, amongst the rubble of former houses. A weird, sometimes beautiful, often profoundly distasteful, nearly always confusing, dream/nightmare is a good description of Gravity’s Rainbow.

In contrast to the fever dream feel, there is also a lot of hard science in the book, chemical bonds and engineering principles related to rockets and the industries that support them. The scientific method involves studying one variable while excluding all others. But in Gravity’s Rainbow it is impossible to separate one variable from another. The subject of astrology comes up quite frequently, a non-scientific subject in the sense that you can never separate one variable from another. You can’t keep Jupiter still while studying the effect of the movement of Mercury, for example. Gravity’s Rainbow is informed by science, but has an artistic sense that life’s variables can’t be isolated from one another.

So does all this make for a good book? I don’t know. Who am I to judge? My personal feeling was that Gravity’s Rainbow might be full of fascinating ideas, but the actual reading experience was patchy, at times entertaining, moving and interesting, but increasingly hard work and exhausting into the later sections. Thomas Pynchon certainly did not follow Hemingway’s writing advice that ‘the main thing is to know what to leave out’. Nothing is left out of this massive novel. Personally, I felt that some of Hemingway’s leaving out would have been beneficial to my reading pleasure. All the oppositions that get demolished in Gravity’s Rainbow include the idea of a good or bad book. This one is both.

December 3, 2023

Prophet Song by Paul Lynch – Fighting the Wrong War

Prophet Song is a novel by Irish author Paul Lynch, winner of the 2023 Booker Prize.

This book imagines Ireland, taken over by a repressive regime, descending into civil war and anarchy. We witness events through the eyes of a woman whose husband is one of the first people to be ‘disappeared’ as the government ramps up oppressive measures.

The story, told in the present tense, has the feel of a movie filmed in one long take. Some parts of it rang true for me – a political party with repressive instincts wins an election, installs sympathisers in prominent official positions, and so becomes a dictatorship. To a certain extent this sort of thing has already happened. There was also a feeling of truth in the suggestion that once the totalitarian rot begins, going back is not easy. Without peaceful transfer of power, the only way to overthrow a government is through violent means, and one lot of violence isn’t much better than another. This gave rise to some fatalistic philosophising, suggesting that societies go through cycles of light and darkness, and there’s not much we can do about it.

Other aspects of Prophet Song were less believable. My reservations focused on the nature of Ireland’s imagined regime, where the state is a faceless, inhuman machine swallowing up individuals. This was like reading a dystopian novel from the 1950s. Against a background of Soviet Russia, and recent experience of Hitler’s Germany, the oppressive states described in books like Nineteen Eighty-Four and Fahrenheit 451 were a reaction to their times. But the situation in western countries in the 2020s is different. Modern would-be dictators tend to be highly visible populists. They are hostile to state institutions, presenting them as enemies of personal freedom. The problem is not so much the state, more the wayward individual who, seeking personal aggrandisement at all costs, finds the moderating influence of state institutions standing in their way. And in fact, even back in the day of famously dark twentieth century novels, the individual may have been a bigger problem than is generally allowed. Repression is often linked to a single, deranged person, whether that’s Hitler or Stalin, or a more recent wannabe. Even the oppressive regime in Nineteen Eighty-Four centres itself on the idea of an individual – Big Brother. In Prophet Song there is no such figure. There is just ‘the state’.

Perhaps it is our desire to see the world in personal terms that helps an inappropriate individual into a position of authority. People identify with a familiar face rather than a department of policy experts. Fame is the major determinant of political success, not competence. We need to rethink that. The struggle today is not with a faceless state, but with the well known faces of people who are unsuited to their position of public responsibility. The men and women who work for the state, unsung civil servants, scientific advisors, administrators of museum and arts funding, social security officials, teachers, health workers – are they really the problem? Nothing is perfect, but if anyone is fighting the good fight, it is usually them.

Prophet Song does not address such complications. In many ways it is engaged in a battle that does not apply anymore. The book reminded me of an idea attributed to Georges Clemenceau, French Prime Minister during World War One. Clemenceau is supposed to have said that generals are always prepared to fight the previous war, not the current one. Sometimes this applies to novels as well.

November 19, 2023

Snow Crash by Neal Stephenson

Science fiction often works by taking dangerous potentials lurking in current trends and then magnifying them out into a possible future. A lot of famous mid-twentieth century science fiction – Brave New World, Nineteen Eight-Four, Fahrenheit 451, imagined what would happen if government gained excessive power over people’s lives. Maybe by the 1990s some were taking this message rather too seriously. 1990s America saw a strengthening of sentiment hostile to government. Conservative groups, such as the ‘Citizens for Sound Economy’ stated an aim for smaller government and less regulation. Then came the Tea Party of the 2010s, and the Republican Party of the 2020s, parts of which appeared to want not just smaller government, but no state institutions at all. Interestingly, the world of 1992’s Snow Crash, by Neal Stephenson, imagines the consequences of these people getting their way. With organised crime stepping into the power vacuum, it’s not a pretty picture. The rich live in gated communities, the poor in ghettos. The police are a private enterprise protecting those best able to pay. And of course, the cruelly ironic effect of ‘freeing’ yourself from stabilising institutions, is an increased risk of some deranged individual coming along and imposing a personal dictatorship. And this is where Snow Crash’s magnified threat comes in. Maybe the threat we face isn’t where the old sci fi thought it would be. Snow Crash might be closer.

Snow Crash by Neal Stephenson – A Little Knowledge is a Dangerous Thing

Science fiction often works by taking dangerous potentials lurking in current trends and then magnifying them out into a possible future. A lot of famous mid-twentieth century science fiction – Brave New World, Nineteen Eight-Four, Fahrenheit 451, imagined what would happen if government gained excessive power over people’s lives. Maybe by the 1990s some were taking this message rather too seriously. 1990s America saw a strengthening of sentiment hostile to government. Conservative groups, such as the ‘Citizens for Sound Economy’ stated an aim for smaller government and less regulation. Then came the Tea Party of the 2010s, and the Republican Party of the 2020s, parts of which appeared to want not just smaller government, but no state institutions at all. Interestingly, the world of 1992’s Snow Crash, by Neal Stephenson, imagines the consequences of these people getting their way. With organised crime stepping into the power vacuum, it’s not a pretty picture. The rich live in gated communities, the poor in ghettos. The police are a private enterprise protecting those best able to pay. And of course, the cruelly ironic effect of ‘freeing’ yourself from stabilising institutions, is an increased risk of some deranged individual coming along and imposing a personal dictatorship. And this is where the next part of Snow Crash’s magnified threat comes in.

The book’s vision of a technological future has computer users hanging out in a digital world called the Metaverse – and yes, this was the first use of the term. The story centres on a virus, called Snow Crash, which makes a kind of species jump between digital and biological realms. A powerful business mogul wants to use this ambivalent infection to control people and take over the world.

Now, the Snow Crash virus presented in the book is complicated and not very believable. It’s variously a computer virus that enters the brain of computer programmers via the optic nerve, a biological agent spreading through blood products, and a linguistic trigger transmitted by certain patterns of words. It may have originated in the Sumerian civilisation, or maybe outer space.

I felt that the Snow Crash virus was interesting not so much for its bewildering details, but more as an illustration of the sort of viral misinformation that has become such a problem since the 1990s. The book has the nature of an influential meme, which typically takes kernels of truth – in this case drawn from computing, linguistics, history and biology – and spins them into conspiratorial delusion. The result is beguiling nonsense. I felt that Snow Crash is a book relevant not so much for what it says, but for what it is, a conspiracy novel in a similar vein to The Da Vinci Code. Snow Crash shows how much people are drawn into the kind of fantasy that uses bits of truth as a springboard into a more fantastical situation, explaining the apparent machinations of those that would control us. Truth can be boring, a bit bureaucratic, making you feel small and insignificant. It is tempting to leave truth and work-a-day bureaucracy behind, taking back control by explaining everything in terms of an overarching conspiracy. But no good will come of it.

I found Snow Crash somewhat chaotic in both plotting and ideas. It is, however, one of those books that catches a moment in the evolving chaos of people and their doings. It is a commentary on, and an example of, the present difficulties we now face.

I’ll give the last word to Alexander Pope:

A little knowledge is a dangerous thingDrink deep or taste not the Pierian Spring

There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,

and drinking deep largely sobers us again

November 10, 2023

The Big Sleep, by Raymond Chandler – Who Cares Who Did It

Nighthawks by Edward Hopper

Nighthawks by Edward HopperWhen he lost his job as an oil company executive, Raymond Chandler found himself unemployed during the years of the Great Depression. Thrown back on an early interest in writing, he decided that crime fiction might pay the bills. In a business-like way he taught himself the genre’s formula by reading pulp magazines and the work of Erle Stanley Gardner, creator of Perry Mason. The Big Sleep, published in 1939, was Chandler’s first novel.

Obviously, if you are a writer working during the Great Depression, and you don’t have any other income, you have to sell books and make money. Never mind poetic musings about life. If people like crime stories, that’s what you have to provide.

Looking back on his career, in his book Trouble is My Business, Chandler reminisced about trying to escape the limits of his chosen genre. While crime appeared to be his only option from a financial point of view – feeling ill-equipped to write romance for women’s magazines – he decided to join those who stretched the formula by writing stories where solving a mystery was not really the point. For Chandler, the perfect detective story ‘was one you would read if the end were missing’. Scene should outrank plot.

That was how I enjoyed The Big Sleep. The plot, involving a wealthy, grievously ill man, his wayward daughters and a blackmail attempt, is fairly confusing. I preferred to follow private detective Philip Marlowe, going about his work in long, lugubrious scenes, through rainy nights in 1930s Los Angeles. Marlowe’s character provides the interest. He is a detective living in a society of murky morals, where, for example, changing attitudes to Prohibition make the drinks business an illegal enterprise one day, a legitimate business the next. Certainties are hard to find. Marlowe responds by shrinking his personal world down to a small flat, and his work. And that’s it. From this little fortress he looks out at life, just as Raymond Chandler himself looks out from the tight confines of crime fiction. In a dark way, it’s almost cosy, in the sense that we have settled into our small corner, appreciating its limits even in resenting them.

For all the compulsive effort Marlowe puts into his work, even dreaming about it at night, he never gets a pay off, either financially or emotionally, at the end of it. In fact, there never really is an end. As he says to his client: ‘when you hire a boy in my line of work, it isn’t like hiring a window washer and showing him eight windows, and saying, “Wash those and you’re through”’.

There are, however, some dark consolations to be found in never reaching a satisfactory conclusion. When you are reading for scene rather than plot, the story’s point is not a few moments right at the end when the mystery is solved and justice apparently done. The point of the story is the whole thing, the long, atmospheric scenes which can be enjoyed in a leisurely way as Marlowe wanders through Hollywood fog. The journey becomes its own destination. I really enjoyed The Big Sleep in that respect. The term Big Sleep is a euphemism for death, the end of all our journeys. In that case it is definitely best to focus on scene rather than plot. Plot will provide a few moments of satisfaction: scene can last a lifetime.

November 7, 2023

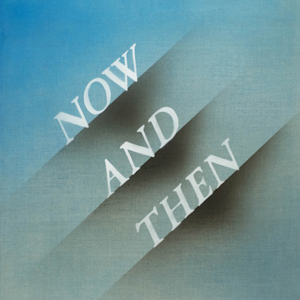

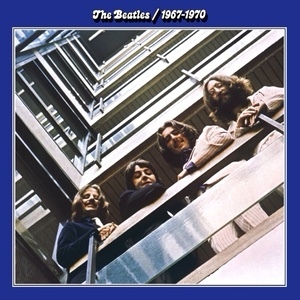

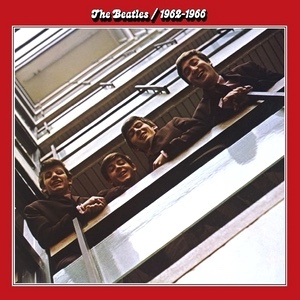

Now And Then Album Cover – Living on a Diagonal

In November 2023, The Beatles released their last song, Now and Then, with front cover art by American artist, Edward Rushcha.

Observant fans have drawn comparisons between the Red and Blue compilation album covers and the Now and Then cover, in the sense that they all feature diagonal lines. Is that just a coincidence? Or does this type of line have a role to play in producing an interesting and fitting image?

Let’s start with those Red and Blue album covers. The Beatles are pictured on the internal stairway at EMI House in 1963 and 1969. The stairwell balconies create a set of diagonals. These images could have been presented face on, but photographer Angus McBean tipped everything sideways. In photography or art, horizontal and vertical lines naturally suggest stability and structure. Diagonals, by contrast, bring a sense of dynamism, excitement, instability or insecurity. In the words of Cornell academic Charlotte Jirousek, an object on a diagonal line is always unstable in relation to gravity. The Red and Blue era Beatles appear happy enough, but the angled balconies imply something like a sinking ship. The exciting and terrifying experience of being world famous, while creating music of turbulent reinvention, certainly must have been ‘unstable in relation to gravity’.

Now and Then has been billed as the last Beatles song, but lyrically it’s really about continuing emotional uncertainty, and does not suggest an end. The cover reflects this. Apart from the diagonals, the image is ambivalent in how solid it appears to be. The background colouration could be seen either as a flat plain, on which the diagonals sit as folds, or as a gauzy, misty, watery surface with depths beyond. We have not reached firm ground. Everything is still slipping and sliding, and we cannot be sure of our footing. In fact Rushcha’s cover makes me think of words associated – accurately or otherwise – with John Lennon: ‘It’ll be alright in the end, and if it’s not alright, it’s not the end.”

(Images courtesy of Wikipedia Commons)

October 28, 2023

Skippy Dies by Paul Murray – a Theory of Doughnuts, the Universe and Everything

Skippy Dies is Irish author Paul Murray’s second novel, published in 2010, and long listed for the 2010 Booker Prize.

The story starts with the death of Daniel Juster – or Skippy to his friends – in a doughnut shop. We then go back to events leading up to Skippy’s demise, before moving on to its dramatic aftermath.

In some ways this is an old fashioned book, set in a posh boarding school, describing the humorous antics of pupils and teachers – reminding me of Kipling’s Stalky and Co., and Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, both of which I’ve read recently. On the other hand, Skippy Dies is very modern. The boarding part of the school is old and decrepit, earmarked for rebuilding. The involvement of the Catholic Church in running the school is winding down, an unpleasant, management-speak acting-principal manoeuvring to take over from an ailing incumbent. The pupils have modern concerns, whether that means video games, fast food, drugs, or in the case of one scientifically-inclined boy called Ruprecht, string theory. The story also has a harsh edge of realism, which makes Stalky and Co. at its most unpleasant, seem traditionally well-mannered by comparison.

Thinking about what I made of it, I kept recalling one particular scene where a group of boys discuss Robert Frost’s poem, The Road Less Travelled. Dennis, the class cynic, thinks it’s about less than orthodox sexual practices, which seems a crazy idea, but which actually makes perfect sense of the poem. I thought of Skippy Dies in this way – a book presenting life as a confusing, crazy mess, where any interpretation of its ‘meaning’ is going to make you sound like a schoolboy with mad ideas about the poems of Robert Frost. And yet… the mad meaning actually seems to make sense. String theory boy, Ruprecht, is continually trying to come up with a scientific concept that explains the universe. If there is any theory explaining the Skippy Dies universe, it is a contradictory scheme that is complete nonsense but still, in an odd way, hangs together. Maybe if scientists do ever come up with a theory that explains the universe, it might be nice if it’s something similar, an explanation that leaves much to explain.

This is a big, sprawling, funny, tough book with lots of scientific and historical ideas colliding with doughnut eating and cynicism. It’s certainly fun to read, though some sections are distinctly discomforting. Overall, a traditional-feeling book with a modern message.