Brian M. Watson's Blog, page 2

October 25, 2015

‘The Nature of English Erotic Fiction is Changed:’ The filthy and crapulous Romance of Lust

The Cover of an Edition of Romance of Lust

Last week, we discussed the Victorian gentleman Henry Spencer Ashbee and his various Indexes, which essentially serve as the best surviving record of nineteenth century pornographic novels in all of their great variety and obscenity. One of the most fascinating and ridiculous is the Romance of Lust, which was published anonymously by a publisher named William Lazenby in four volumes between 1873 and 1876. In the third volume of his Index Ashbee asserts it was largely written by William Simpson Potter, a minor 19th century novelist. He also notes that other authors helped: the book was “not the product of a single pen, but consists of several tales, ‘orient pearls at random strung,’ woven into a connected narrative by a gentleman, perfectly well known to the present generation of literary eccentrics and collectors.” He describes Potter as a “shrewd business man, the ardent collector, and the enthusiastic traveler … [with] a patriarchal, almost reverent appearance.” Altogether, Ashbee comments that The Romance of Lust “though no masterpiece of composition” is better-written than most of its competition. But, almost with a frown, Ashbee says that it contains scenes

not surpassed by the most libidinous chapters of [Sade’s] Justine. [which we discussed here]. The episodes, however, are frequently most improbable, sometimes impossible, and are as a rule too filthy and crapulous. No attempt is made to moderate the language, but the grossest words are invariably employed.

A brief survey of the work, which maunders through 300-plus dense pages of description, would give this impression as well. So let us begin!

Please note that some of the text/images below the fold are NSFW (not safe for work).

The Romance is a blow-by-blow account of the amorous career of a boy (and then a man) named Charles, told from his point of view. He begins his tale in his fifteenth year, and states that along with his two younger sisters, “Mamma treated us all as children, and was blind to the fact that I was no longer what I had been … my passions were awakening.” In a revealing detail about how different children were raised, and how beds were shared in a earlier time, as we’ve discussed here and here, Charles notes that

My sisters and I all slept in the same room. They together in one bed, I alone in another. When no one was present, we had often mutually examined the different formations of our sexes. We had discovered that mutual handlings gave a certain amount of pleasing sensation; and, latterly, my eldest sister had discovered that the hooding and unhooding of my doodle, as she called it, instantly caused it to swell up and stiffen as hard as a piece of wood. My feeling of her little pinky slit gave rise in her to nice sensations, but on the slightest attempt to insert even my finger, the pain was too great. We had made so little progress in the attouchements that not the slightest inkling of what could be done in that way dawned upon us.

The death of his father and the increasing illness of his mother causes her to hire a governess named Evelyn to educate and discipline Charles and his two sisters, Mary and Eliza. The mother describes the children to Evelyn as “somewhat spoiled, and unruly; but there is a horse, and Susan will make you excellent birch rods whenever you require them. If you spare their bottoms when they deserve whipping, you will seriously offend me.” This, as they say, is pretty blatant foreshadowing, and it is not too long afterwards that we have our first blatantly sexual scene, one of flagellation. Charles’ sister Mary refuses to do something that Evelyn commanded, and as a result she is placed on ‘the horse,’ which was a device used to administer corporal punishment. Charles’ description of it reads quite like a sex device from a BDSM catalog:

Corporal Punishment used in a School

[Evelyn] placed [Mary] on it, held her firmly with one hand while she put the noose round her with the other, which, when drawn, secured her body; other nooses secured each ankle to rings in the floor, keeping her legs apart by the projection of the horse, and also forcing the knees to bend a little, by which the most complete exposure of the bottom, and, in fact, of all her private parts too, was obtained. . . The rod whistled through the air and fell with a cruel cut on poor Mary’s plump little bottom. The flesh quivered again, and Mary, who had resolved not to cry, flushed in her face, and bit the damask with which the horse was covered. . . Cut succeeded cut, yell succeeded yell —until the rod was worn to a stump, and poor Mary’s bottom was one mass of weals and red as raw beef. It was fearful to see, and yet such is our nature that to see it was, at the same time, exciting.

Woman at her Toilet, Charles watching Ms Evelyn

Inadvertently, for a teenage boy, Charles quickly becomes infatuated with Evelyn and watches her undressing every night in the bedroom he shared with her and his sisters. Being ‘so innocent,’ he of course never thinks of “applying [his] fingers for relief,” and remains innocent. Innocent, at least for a few more pages (and two months later) when his mother is visited by a friend, Mr. B (who seems to have the most reoccurring name in English erotica, he pops up in Pamela, Fanny Hill, and even Justine), and his wife. One night, when trying to get something from a closet, he hears them coming and hides, peeking through a crack in the door:

[Mr. B] got up, and lifted her on the edge of the bed, threw her back, and taking her legs under his arms, exposed everything to my view. She had not so much hair on her mount of Venus as Miss Evelyn, but her slit showed more pouting lips, and appeared more open. Judge of my excitement when I saw Mr. Benson unbutton his trousers and pull out an immense cock. Oh, dear, how large it looked; it almost frightened me. With his fingers he placed the head between the lips of Mrs. Benson’s sheath, and then letting go his hold, and placing both arms so as to support her legs, he pushed it all right into her to the hilt at once. I was thunderstruck that Mrs. Benson did not shriek with agony, it did seem such a large thing to thrust right into her belly. However, far from screaming with pain, she appeared to enjoy it.

A few days later, Mr. B is forced to run away on business, and his wife, Mrs. Benson, who apparently cannot last more than a day or so without getting off, ropes Charles into visiting her room, and then in one long-winded and glorious night, “initiat[es Charles] into all the rites of Venus… the ne plus ultra [highest peak] of erotic pleasure.” The next fifty pages describe, in endless details all of the rites Mrs. Benson initiates him in.

It was a long bout indeed, prolonged by Mrs. Benson’s instructions, and she enjoyed it thoroughly, encouraged me by every endearing epithet, and by the most voluptuous manoeuvres. I was quite beside myself. The consciousness that I was thrusting my most private part into that part of a lady’s person which is regarded with such sacred delicacy caused me to experience the most enraptured pleasure. Maddened by the intensity of my feeling I at length quickened my pace. My charming companion did the same, and we together yielded down a most copious and delicious discharge.

As is quite common in earlier pornographic novels, such as Luisa Sigea or The School of Venus, Mrs. Benson also educates (initiates) Charles into anatomy and biology: “My dear Charles, do you see that little projection at the upper part of my quim, that is my clitoris, and is the site of the most exquisite sensations… you will find as you titillate it with your tongue or suck it, that it will become harder and more projecting,” and cautions him to be careful about how many times in a day he has sex: “I must consider your health. You have already done more than your age warrants, and you must rise and go to your bed to recover, by a sound sleep, your strength.”

Furthermore, she also educates him on how to manage his affairs, which is perhaps the only code of morals that is followed throughout the book. She lectures that he must “show great discretion and ready wit … [for] discretion is the trump card of success” and most importantly, he must let all his lovers “for some time imagine that each possesses you for the first time… you must enact the part of an ignoramus seeking for instruction.”

There, darling, that will do for the moment… I hope, my dear Charlie, that under my auspices you will become a model lover—your aptitude has already proved in several ways. First and best, with all the appearance of a boy, you are quite a man, and even superior to many. You have already shown great discretion and ready wit, and there is no reason to fear that you will become a general favourite with our sex, who soon find out who is discreet and who is otherwise—discretion is the trump card of success with us. Alas! few of your sex understand this… I have one piece of advice to give you as to your conduct to newer lovers: let them all for some time imagine that each possesses you for the first time. First of all, it doubles their satisfaction, and so increases your pleasure.

Shortly thereafter, Charles “ felt my opportunity was at hand to initiate my darling sister into the delightful mysteries that I had just been myself instructed in,” and proceeds to instruct his older sister Mary in all “all those are in the way of kissing and toying with your charming little Fanny,” and shortly thereafter his younger sister Eliza, commenting that “A reflection struck me that it would be necessary to initiate my sister Eliza in our secrets, and although she might be too young for the complete insertion of my increasingly large cock, I might gamahuche her while fucking Mary, and give her intense pleasure. In this way we could retire without difficulty to spots where we should be quite in safety, and even when such was not the case, we could employ Eliza as a watch, to give us early notice of any one approaching. It will be seen that this idea was afterwards most successfully carried out to the immense increase of my pleasure.”

There are some Sadean comments from the author as a result of this: Thus delightfully ended the first lesson in love taught to my sister, and such was my first triumph over a maidenhead, double enhanced by the idea of the close ties of parentage between us. In after-life, I have always found the nearer we are related, the more this idea of incest stimulates our passions and stiffens our pricks, so that if even we be in the wane of life, fresh vigour is imparted by reason of the very fact of our evasion of conventional laws.

The rest of the book is, quite simply, an exercise in increasing bawdiness, endless sex, and trampling of all societal boundaries. The second volume includes his orgies with his sisters and an older gentleman named James MacCallum, and the siblings’ seduction of their new governess, Miss Frankland. The end of the second volume and the beginning of the third concerns Charles’ ‘seduction’ by his aunt and uncle, and then the seduction of an extremely young village boy named Dale by him and his uncle. The fourth book reaches the height of profligacy and hedonism when all of the parties come together in a tumult:

Orgy from de Sades Juliette

myself in my aunt’s cunt, which incest stimulated uncle to a stand, and he took to his wife’s arse while her nephew incestuously fucked her cunt. The Count took to the delicious and most exciting tight cunt of the Dale, while her son shoved his prick into his mother’s arse, to her unspeakable satisfaction. Ellen and the Frankland amused themselves with tribadic extravagances.

And so on. The fourth volume comes to a close with a description of the children of the assorted couples, and how they too were “initiated in all love’s delicious mysteries by their respective parents.” With a final commentary by Charles, the book ends: “we are thus a happy family, bound by the strong ties of a double incestuous lust. It is necessary to have these loved objects to fall back upon, for alas! All the earlier partakers of my prick are dead and gone.”

All concerned, The Romance of Lust manages to cover sexual education, masturbation, heterosexual sex, lesbianism, male homosexuality, flagellation anal sex, double penetration, sexuality, incest, pedophilia, and coprophilia on a the short list. Unlike the stories that this essay began with, there is almost no dialogue, and very little plot that is not related to sex or serving as a vehicle, segue, or bridge to another sexual encounter. Nor is there really an effort at philosophizing or any sort of moral struggle. Lisa Sigel has, perhaps, attempted to redeem the work by arguing that the text is concerned with chronicling “a child’s growth to adulthood through his sexual awakening and activities …the [book] explains, expands, and reinforces the [act of penetration] …penetration becomes the essence of sexual activity.” Although this is true, it seems that the text provides just as many examples of ‘gamahuching,’ or oral sex, as the author calls it, and all other forms of sex abound as well. However, Siegel is right when she notes that “all penetration is good:” the novel presents all sex, sexual act, and sexualities in a positive, enthusiastic manner.

The reality of the issue, however, was that Holywell Street literature had matured into something resembling modern pornography in all but name—and as the word became increasingly popular, erotic literature simply came to fall under the umbrella of ‘pornography.’

Ashbee, perhaps the scholar emeritus of the field, also noted this in the introduction to his final (and most modern) Index:

We cannot fail to perceive that while in the former books [like Fanny Hill] the characters, scenes, and the incidents are natural, and the language not unnecessarily gross, those in the latter are false, while the words and expression employed are of the most filthy description. CLELAND’s characters—Fanny Hill, the coxcomb, the bawds, and the debauchees with whom they mix, are taken from human nature and do only what they could and would have done under the very natural circumstances in which they are placed; whereas the persons in the latter works are the creations of a disordered brain, quite unreal, and what they enact is either improbable or impossible. Thus, the nature of English erotic fiction is changed.

Indeed, Ashbee argues that “immoral and amatory fiction…must unfortunately be acknowledged to contain, cum granum salis, a reflection of the manners and vices of the times—of vices to be avoided, guarded against, reformed… English Erotic Novels, I repeat, are sorry productions.” That language of his—‘vices to be avoided, guarded against, reformed’—sounds suspiciously similar to the SSV’s description of their own goals. In truth, it is likely the best one-sentence summary of their entire project that has been written. “Better were it” Ashbee continues, “that such literature did not exist. I consider it pernicious and hurtful to the immature, but at the same time I hold that, in certain circumstances, its study is necessary, if not beneficial.”

Sources:

[2] The Romance of Lust – Anonymous (apparently it also comes in audiobook format?! scandalous.)

October 17, 2015

Henry Spencer Ashbee: The Victorian with the Pornographic Secret

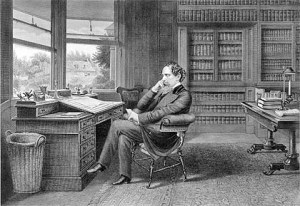

Henry Spencer Ashbee

In last week’s entry we discussed the passing of the British Obscene Publications Act in 1857. The impact of this law on England (and its colonies in North America, Asia and Australia) specifically and on other Western cultures generally can hardly be understated. For example, fifteen years later the United States would pass a series of laws that became to be known as the Comstock laws, and were modeled after the Obscene Publications Act. They prohibited the sending of erotica, contraceptives, sex toys, abortifacients [drugs or methods to cause abortion], and prohibited any information or advertisement on the above topics.

After the passing of the law, its author and sponsor, Lord Campbell, declared victory over the obscene publications and their publishers:

He was told that informations [sic] had been laid against dealers of the publications in question in Holywell Street; that warrants had been granted and searches made; and that large quantities of these abominable commodities had been found, and the parties owning them summoned before the magistrates… at last he was told, it was now in the quiet possession of the law, for the shops where these abominations were found had been shut up, and the rest of the houses were now conducted in a manner free from exception. [1]

And indeed, no doubt the Holywell Street authors laid low for a few years, but less than a decade later the Saturday Review reported that “the situation was as bad as ever, and that ‘the dunghill is in full heat, seething and steaming with all its old pestilence.”

Please note that text/images below the fold may be NSFW (not safe for work).

The final decades of the 1800s saw a veritable renaissance of pornography in England and other places, with new books being issued by the week. To provide a small selection, visitors to London’s Holywell Street in the years following the Obscene Publications Act would see such titles as: Intrigues in a Boarding School (1860), Confessions of a Lady’s Maid (1860), How to Raise Love or The Art of making Love, in more ways than one (1863), Lucretia or the Delights of Cunnyland (1864) which is a more obscene version of the Merryland books we discussed, or even The Inutility of Virtue, which was cheekily printed for the ‘Society of Vice’ (1865). Selective purchasers were rewarded when specialized genres and keywords began to develop, similar to modern-day pornographic subgenres: the boarding school, virgin confessions, nunneries, sex guides, flagellation—each with their own standard plots and tropes, much like a modern-day romance novel. It makes little difference which title one might buy, as nearly all of them saw a dramatic increase in the amount of sex and sexual positions at the expense of plot, narritive, or character, sometimes to the point of absurdity. Plot and style became a tattered scrap of plausibility to throw over scenes of debauchery, much like our modern pornography videos of “pizza delivery” or the “plumber’s visit.” One of the most obscene and absurd was the multi-volume The Romance of Lust which began appearing as early as 1859, and will be discussed in greater detail below. [2]

The third Ashbee publication.

Much of this renaissance was attributable to William Dugdale’s (who we discussed here) release from prison, but other publishers such as John Hotten or William Lazenby soon realized the profits to be made. All of the above titles and hundreds more, are noted, described, and excerpted in a series of erotic indexes: Index Librorum Prohibitorum (Index of Prohibited Books, 1877), Centuria Librorum Absconditorum (A Hundred Hidden Books, 1879) and Catena Librorum Tacendorum (A Series of Silenced Books, 1885). Originally privately published, this trilogy were originally attributed to fake author ‘Pisanus Fraxi,’ and they are essentially whirlwind bibliographies of pornographic books–an early iMDB of pornography.

[image error]

Charles Ashbee’s Electrical Chandelier (wikimedia)

The man behind the curtain, so to speak, was Henry Spencer Ashbee, who, on the surface, was a quite reputable and successful Victorian gentleman. Born in 1834 to moderately successful Kentish parents, Robert and Frances Ashbee, Henry Spencer would go on to become an extremely successful businessman himself when he married his wife, Elizabeth Lavy (their son Charles became a major artist). His new father-in-law would made him the head of a small branch of the textile company Charles Lavy & Co, and under Ashbee’s management the firm grew tremendously successful in England, France, Spain, Belgium and the United States. Much of Ashbee’s success is attributable to his amazing grasp of languages and literature–as a child he had been educated as in Greek, Latin, modern languages and literature, History and Geography. He never attended university or college, but his grasp of French, German, and Spanish were so good that he had an entry in the French version of Who’s Who and was elected to a prestigious post as a Spanish literary critic. [3]

His fluency also aided him in his obsessive and secret hobby, a hobby that ended up becoming the great passion of his life. Behind the scenes “he was engaged in the ambitious project of becoming the century’s leading collector and bibliographer or erotic books Ashbee emerges as the archetypical Victorian gentleman with a secret.” He began this hobby probably under the influence of a close friend of his, but eventually–probably due to a lot of money and a lot of time to read–Ashbee began to be obsessive about his collection, buying copies of every erotic text he came across. His trips across Europe on business especially helped in this goal, and he even made friends with a British ambassador who would smuggle erotic books into England in goverment bags (that could not be searched).

In his early fourties, Henry Spencer Ashbee decided he needed to set himself to a new project, as a way of giving back to all of his rich friends who had helped him collect these erotic and pornographic books–he decided to write a trilogy of Indexes of erotic literature. In his first Index, Index Librorum Prohibitorum, published in 1877, he described his reasons for doing this:

That English erotic literature should never have had its bibliographer is not difficult to understand. First and foremost the English nation possesses an ultra-squeamishness and hyper-prudery peculiar to itself, sufficient alone to deter any author of position and talent from taking in hand so tabooed a subject; and secondly English books of that class have generally been written with so little talent delicacy or art that in addition to the objectionableness of the subject itself they would undoubtedly be considered by most bibliographers as totally unworthy of any consideration whatever. [2]

Ashbee in his Library.

Ashbee, along with a group of male intellectuals in the Victorian era (including the famous Sir Richard Francis Burton, the adventurer and translator and close friend of Ashbee) was profoundly disturbed by what he saw as the backwards sexual morality and ‘hyper-prudishness’ of English society at the time, and his Indexes were partially a way to preserve the transient pornographic texts that are the most likely to be destroyed. As a result, many of his exceprts are the only surviving record of these book we have today. Pre-empting the charge that his commentaries are obscene, Pisanus Fraxi insists that ‘in treating of obscene books it is self-evident that obscenities cannot be avoided’, adding immediately that in his own text he will never be caught using an ‘impure word when one less distasteful but equally expressive can be found.’ And, anyways, nobody is going to be aroused by his commentaries:

The passions are not excited. Although the citations I produce are frequently licentious, being as a matter of course those which I have considered the most remarkable or most pungent in the books from which they are extracted; yet I give only so much as is necessary to form a correct estimate of the style of the writer, of the nature of the book, or the course of the tale, not sufficient to inflame the passions. This could only be accomplished by the perusal of the books in their entirety, by the reader giving himself up in fact to the author. My extracts on the contrary will, I trust and believe, have a totally opposite effect and as a rule will inspire so hearty a disgust for the books they are taken from, that the reader will have learned enough about them from my pages and will be more than satisfied to have nothing further to do with them. [2,3]

Being as knowledgeable as he was, Henry Spencer Ashbee knew that if he didn’t think of something clever, his indexes and his entire pornographic collection would be destroyed upon his death. Therefore he came up with a really clever tatic: along with his pornogaphy collection, he had the world’s largest collection of Don Quixote and Cervantes manuscripts and prints, so when he died, he offered both the erotica and the Cervantes to the British Museum on the condition that they take all of it (excepting duplicates) or none of it. Ian Gibson records what happened next:

The British Museum, informed of the Bequest on 6 August 1900 by Ashbee’s solicitors, Kennedy, Hughes, and Posonby, found itself in something of a quandary. The Trustees pointed out that the will made it clear the Museum must take all or nothing. So rich was the Cervantes collection, which included 384 editions of Don Quixote alone, so unique were some of the other items, that there could be no question of rejecting the bequest out of hand despite the presence of erotica. But what to do about the latter? …

[The Museum stated] ‘With regard to the collection of obscene books [we] have gone through the whole of them and have packed six boxes the duplicate copies. He asked the permission of the Trustees to destroy them.’ … Peter Mendes has come to the conclusion that, along with the ‘duplicates,’ the British Museum authorities destroyed the greater part of Ashbee’s collection of ‘poorly produced, illustrated pornographic fiction (particularly in English) of the nineteenth century,’ perhaps some hundred items… The loss to research is definitive because often no other copies of the works are known to have been preserved.

The former Private Case in the British Museum.

The books that were preserved were collected in a part of the British Library called the Private Case, which was, until recently, totally off limits to the public. Only recently have the public and academics been allowed permission to peruse the books, but there are still a number of strict rules surrounding it. When I visited earlier this year, there were all kinds of safeguards in place–for example, you had to read these books under the supervision of librarians, and you were not allowed to leave them on your desk if you went to the bathroom or got up to stretch your legs. Furthermore, if you were leaving for lunch, you had to return them behind the desk, and they would be placed in a chest and securely padlocked.

Knowing what we do about Henry Spencer Ashbee, being victorian’s foremost porography expert and all that, it would be surpring to think that there were books that could shock even him. For example, in one of his Indexes he comments that a certain book, The Romance of Lust contains scenes “not surpassed by the most libidinous chapters of [Sade’s] Justine [which we discussed here]. The episodes, however, are frequently most improbable, sometimes impossible, and are as a rule too filthy and crapulous. No attempt is made to moderate the language, but the grossest words are invariably employed.”

So let’s dive in to this romance, of uh, lust, next week

October 6, 2015

A Poison more Deadly than Prussic Acid, Strychnine, or Arsenic: The Obscene Publications Act of 1857

A Disapproval stamp that was used following the Obscene Publications Act.

A couple of entries ago, I mentioned that The Lustful Turk, which we discussed in greater detail last week was first published between 1828 and 1830 by a John Benjamin Brookes, and then republished by William Dugdale in 1857, pirating Brookes pornographic book without permission or reservations. Dugdale, by this time had been a publisher for about three decades (since 1822) and had been specializing in pornographic and subversive literature since at least 1828, and indeed became infamous as “the principal source of such publications in the country.” He had also been prosecuted by the Society for the Suppression of Vice at least nine times before 1857. Indeed, his constant mocking of the Vice Society frustrated them to no end, and they were determined use him as an example, to demonstrate to the government why a law specific to obscene publications was. So when he republished The Lustful Turk in 1857, they saw their chance, and managed to get him arrested and dragged before an influential member of England’s House of Lords: Lord John Campbell, 1st Baron Campbell.

No nobody’s surprise, Dugdale was (once again) convicted of publishing obscene libel, the same crime Edmund Curll had been prosecuted for over 130 years prior. Despite over 50 years of lobbying from 1802 to 1857, the Society for the Suppression of Vice had not been successful in getting major vice legislation passed. In 1817, the SSV’s Secretary, George Pritchard, testified before the House of Commons about their crusade. When asked how many prosecutions the Vice Society had launched, Pritchard testified

between thirty and forty, in all of which they have succeeded… [but] in consequence of renewed intercourse with the continent [after the Napoleonic War], incidental to the restoration of peace, there has been a great influx …of the most obscene articles of every description.

The House of Commons continued questioning him about the nature of the prosecutions, eventually asking his opinion on the adequacy of the current laws against obscene literature. Pritchard responded that the current libel law was

by no means adequate to the suppression of such offenses; for if an itinerant dealer is detected in the very act of dealing obscene prints …he cannot be apprehended without a warrant, which cannot be obtained until after a bill of indictment is presented and found against him … a thing almost impossible … I do not see how this evil can be effectively put a stop to, unless constables and other persons are enabled to seize such offenders without a warrant.

He further testified that many dealers were able to escape with impunity, and that many shops on Holywell Street were able to openly display obscene books and prints for sale.

Although House of Commons did not act on his testimony immediately, by 1824 the Society had succeeded in getting a addition to the 1824 Vagrancy Act that declared

every Person wilfully exposing to view, in any Street, Road, Highway, or public Place, any obscene Print, Picture, or other indecent Exhibition … shall be deemed a Rogue and Vagabond, within the true Intent and Meaning of this Act; and it shall be lawful for any Justice of the Peace to commit such Offender … to the House of Correction, there to be kept to Hard Labour for any Time not exceeding Three Calendar Months.

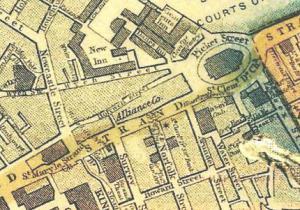

A map of Holywell Street’s former location in London.

In lobbying for this law, the SSV was specifically targeting Holywell Street in London, which was notorious for its ‘obscene prints, pictures and other indecent exhibitions,’ that were visible from the street. Unfortunately for the SSV, the 1824 Act did not define what a ‘public place’ was, and so they found themselves lobbying for revisions for another fourteen years.

The 1838 Vagrancy Act extended the earlier Act to include the display of such material inside a shop or house. Though this law was more stringent, it still required ‘public display,’ and it still did not grant the SSV power to seize and destroy material. Furthermore, they were frustrated by individuals like Dugdale, who had associates or relatives run his business while he was in jail. Finally, the Vagrancy Act was found wanting because it did not stipulate increased punishment for repeat offenders, such as Dugdale, who was prosecuted no less than nine times by the SSV. A greater, more powerful Act was needed, and the 1857 trial of William Dugdale and his associate William Strange, launched by the Society would provide this impetus.

During the course of the trial, the Society managed to impress upon the mind of the judge, Lord John Campbell, the great danger presented by obscene literature. Curious, Campbell examined The Lustful Turk and the other books that Strange and Dugdale were accused of publishing. Disgustedly, he declared his “‘astonishment and horror’ particularly at the low price at which it was sold, declared it to be a ‘disgrace to the country’ and proclaimed that it was ‘high time that an example should be made,’” and sent Dugdale to prison for a year. Not to belabor the point, but Campbell’s revulsion to the low cost and ease of access is a further example of how the definition of indecency hinged upon whether groups such as children or the poor were able to access it.

A couple days later, on May 11th, Campbell announced to the House of Lords that he had “learned with horror and alarm that a sale of poison more deadly than prussic acid, strichnine, or arsenic—the sale of obscene publications and indecent books—was openly going on.” Confirming the double standard for members of the lower and upper classes, Campbell noted that the poison available was not alone “indecent books of a high price, which was a sort of check” but that “the most licentious and disgusting [material] w[as] coming out week by week, and sold to any person who asked for them, and in any numbers.” Six weeks later, he introduced the Obscene Publications Act into the House of Lords.

The House of Lords

There is little purpose in documenting here all the twists and turns of the Act through the House of Lords and Commons, as it has been chronicled many times. The surprising aspect of the process (for people who believe the stereotype of Victorian prudishness) is how much resistance the Act initially encountered in the Houses. Opposition was led by Lord Chancellor Cranworth, and supported Lords Lyndhurst, Brougham and Wensleydale, all who opposed the bill on the grounds that there was no way of defining what the bill sought to suppress: Lord Lyndhurst commented in a wonderfully snarky British way that

My noble and learned Friend’s aim is to put down the sale of obscene books and prints; but what is the interpretation which is to be put on the word ‘obscene?’ I can easily conceive that two men will come to entirely different conclusions as to its meaning.

Furthermore, the consensus was that the bill granted constables too much power without enough oversight. In its original form, based on the strength of one person’s testimony, the authorities were allowed to enter and search any building and then seize and destroy any material they thought might be obscene. The Lords noted that these authorities were not well-known for their aesthetic or cultural judgment.

The resistance was so strong and bitter that Campbell seemed to lose hope and signaled that he might drop the bill. This could not stand! Society for the Suppression of Vice leaped into action, organizing a letter-writing lobbyinh campaign from its members and from the public as a whole. Shortly thereafter, Campbell noted to the House of Lords that he had received

such strong solicitations to proceed from various Members of that House, from clergymen of all denominations, from many medical men, from fathers of families, and from young men who themselves had been inveigled into those receptacles of abomination against which his Bill was directed.

Furthermore, the debate over the law was publicized in newspapers and pamphlets across London, and by the time the bill reached the House of Commons it saw near-universal support from “nearly all shades of the press. . . Campbell and the Society got their act with only minor amendments.”

Campbell was able to sell the act to the Lords by promising that it would apply “exclusively to the works written for the single purpose of corrupting the morals of youth and of a nature calculated to shock the common feelings of decency in any well-regulated mind,” and that any book that made any pretensions of being literature or art, classic or modern, had nothing to fear from the law. The real enemy, to Campbell and the press, were the Holywell Street pornographers.

The irony in Campbell’s argument is that less than three decades later “the law would be used against the classical works the Lords had wanted to guard, and especially against current literature.” Indeed, this same act would be used to target and threaten now-famous authors such as James Joyce and D.H. Lawrence until the 1960s, something we will turn to in later entries.

The Society for the Suppression of Vice put their newly-granted powers to use immediately and by December of the same year, Lord Campbell was able to declare ‘Mission Accomplished’ over London porngraphers:

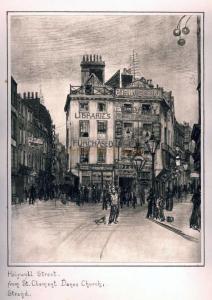

Holywell Street from St. Clement Church

He was told that informations [sic] had been laid against dealers of the publications in question in Holywell Street; that warrants had been granted and searches made; and that large quantities of these abominable commodities had been found, and the parties owning them summoned before the magistrates… at last he was told, it was now in the quiet possession of the law, for the shops where these abominations were found had been shut up, and the rest of the houses were now conducted in a manner free from exception.

If true, this did not remain the case for very long. No doubt the Holywell Street authors laid low for a few years, but less than a decade later the Saturday Review reported that “the situation was as bad as ever, and that ‘the dunghill is in full heat, seething and steaming with all its old pestilence.’”

Indeed, there was a virtual renaissance of pornography in the Strand, new books being issued by the year. Visitors to Holywell Street in the years following the Obscene Publications Act would see such titles as: Intrigues in a Boarding School (1860), Confessions of a Lady’s Maid (1860), How to Raise Love or The Art of making Love, in more ways than one (1863), Lucretia or the Delights of Cunnyland (1864), The Inutility of Virtue—cheekily printed for the ‘Society of Vice’ (1865), The New Epicurean or the Delights of Sex (1865), Adventures of a School Boy (1866), to provide a small selection. Selective purchasers were rewarded when specialized genres and keywords began to develop, similar to modern-day pornographic subgenres: the boarding school, virgin confessions, nunneries, sex guides, flagellation—each with their own literary conventions and tropes. In comparing them to earlier works, it makes little difference on which title one chose to peruse, as nearly all of them saw a dramatic escalation in lubricity, some to the point of absurdity.

The Cover of an Edition of Romance of Lust

One of the most obscene, popular and absurd was the multi-volume The Romance of Lust which began appearing as early as 1859, three years after the supposed death of pornography. This is the work we will turn to next week in these Annals of Pornographie.

Sources:

[1] Parliamentary debates:

HL Deb 11 May 1857 vol 145 cc102-4

HL Deb 25 June 1857 vol 146 cc327-38

HL Deb 03 July 1857 vol 146 cc864-7

HC Deb 12 August 1857 vol 147 cc 1475-84

HL Deb 07 December 1857 vol 146 cc327-383

[2] To the pure…A study of obscenity and the censor — Morris Leopold Ernst

September 24, 2015

The Lustful Turk: Anal Sex, Flagellation, and Threesomes, oh my!

Cover page of an edition of the Lustful Turk

When we left poor Emily Barlow last week she had just “sank on the couch overwhelmed with grief” because she had denied to the Algerian Dey the ability to love her “behind” in the other “grotto, a little more obscure.” Enraged at this, the Dey had stormed out on her, saying that he would let her come to her senses before he would see her or talk to her again, and maybe, just maybe he would forgive her.

In keeping with the epistolary format where all of the action takes place in letters written between the different characters, much like Pamela, Emily tries to get back into the good graces of the Dey by writing to him and announces “Oh, Ali, I am with child; hasten to comfort your miserable slave. You cannot doubt my love. Since the day you overpowered my innocence (the day I consider the happiest of my existence, although truly it was a painful one)” The Dey Ali writes back but refuses to flinch, and says that he “was aware of your being with child,” but declares that “ I am determined to tear myself from your tempting arms until I find your submission perfect.”

There is no other option, Emily must submit wholly to the Lustful Turk.

Please note that some text/images below the fold may be NSFW (not safe for work).

And she does, confessing via letter that she truly loves him and will grant him anything he wants from her. Whether this is supposed to be a sort of Stockholm syndrome or just the regular ridiculousness and poor plot of pornography is unclear, but either way, the Turk gets the object of his desire, and we have Emily here to give us a faithful account, abeit mixed in with some complicated emotions:

A Scene from the 1968 Lustful Turk Movie

he divided my thighs to their utmost extension, leaving the route he intended to penetrate fairly open to his attack. He now got upon me, and… proceeded with great caution and fierceness; in short, he soon got the head entirely fixed. His efforts then became more and more energetic. But he was as happy as the satisfying of his beastly will could make him. He regarded me not, but profiting by his success, soon completed my second undoing; and then, indeed, with mingled emotions of disgust and pain, I sensibly felt the debasement of being the slave of a luxurious Turk. . . By my submission I was reinstated in his affections, and everything proceeds as usual. But the charm is broken. It is true he can, when he pleases, bewilder my senses in the softest confusion; but when the tumult is over, and my blood cooled from the fermentation he causes-when reason resumes its sway, I feel that the silken cords of affection which bound me so securely to him have been so much loosened that he will never again be able to draw them together so closely as they were before he subdued me to his abominable desires.

The last sentence seems a little inconsistent with the rest of the tale, because Emily will be ‘enjoying him to the utmost’ a few short pages later. After these episodes, there is another long digression when another woman in the harem, ‘The Grecian Slave’ (who Emily conveniently “had been able to teach the English language”) tells a long story of losing her beloved during a Turkish raid on her island and the slaughter of him and the priest who was about to marry them. She recounts how when she refused the Dey’s sexual attentions he retaliated by poisoning her wine with a sleeping drug and then taking advantage of her. Suddenly, this letter (because all of the stuff recounted thus far happened in one ‘letter’ only (of course), ends abruptly and we hear from Sylvie, who was supposed to be Emily’s sister-in-law before Emily’s capture by pirates. Sylvie is profoundly and thoroughly disturbed and disgusted:

Emily—It is impossible at once to shake off our earliest acquaintance; if it had been you ought not to have expected that I should have taken any notice of your disgusting letters. What offence have I ever given that you should insult me by writing in the language you have? Why annoy me with an account of the libidinous scenes acted between you and the beast whose infamous and lustful acts you so particularly describe?

She goes on to describe what a horrible effect Emily’s letters and conduct have had on her and Emily’s mother, but notes in an offhand way that some missionaries are coming to Algeria to free slaves soon, and if “you wish to be released from the infamous subjection in which your beastly ravisher seems to hold both your person and senses. If there is a spark of feeling, on your mother’s account (or modesty on your own) left, make no delay in letting me know if you wish to escape from the wretch who thus holds you in his thralldom. I subscribe myself still your friend (if you deserve it).” The book then takes a really strange detour through the letters of a pair of missionaries, Pedro and Angelo, the first of which writes several long letters describing his seduction and enjoyment of a local girl, the daughter of the Marquis de Mezzia in a vaguely religious style (especially ‘rod of Aaron’):

Berthomme’s Naughty Monk and Nun

But never was conquest more difficult. Oh, how I was obliged to tear her up in forcing her virgin defences! With what delicious tightness she clasped my rod of Aaron, as it entered the inmost recesses of her till then virgin sanctuary. How voluptuous was the heat of her young body! I was mad with enjoyment! Her young breasts rising and falling in wild confusion attracted my caresses. Guess my state of excitement. I sucked them, and at last bit them with delight. Although Julia was much overcome with her suffering, still she reproachfully turned her lovely eyes swimming with pain and languor on me. At this instant, with a final energetic thrust, I buried myself up to the very hair in her. A shriek proclaimed the change in her state; the ecstasy seized me and I shot into the inmost recesses of the womb of this innocent and beautiful child as copious a flood of burning sperm as ever was fermented under the cloak of a monk; whereupon, oh, marvellous effects of nature, the lovely Mezzia, spite of her cruel sufferings, ceded to my vigorous impressments. The pleasure overcame the pain, and the stretching of her ivory limbs, the quivering of her body, the eager clasping of her delicate arms, clearly spoke that nature’s first effusion was distilling within her.

The letters go on to describe how the pair conspire to sell “young beauties over the sea to the great gratification of the Turks in Algiers and Tunis, but to the much greater gratification of ourselves, by well lining our own pockets with African gold.” The reason for this detour is soon revealed: Emily’s Dey has hired the pair of monks with his ‘African gold’ to kidnap and sell Sylvie to him because he is upset at the ‘way she talked about him’: he says he was “determined to pay the minx for calling me a beast if it lay in my power.”

Emily walks in on the pair of them going at it and, shocked, immediately faints, and, when she wakes up, is immediately reconciled with Sylvie, who begs “Forgive me, dearest… for the harsh letter I wrote you. Little did I then think that I too should fall a sacrifice to the dear wicked Dey.” Then, the ‘dear wicked’ Dey recounts to Emily in absurd detail what machinations he went through to kidnap and seduce her friend, and everything becomes ‘sweet and charming,’ almost like a fairytale ending:

After this the Dey would often amuse himself with us alternately, compelling one of us to guide into the other his instrument and handle his pendant jewels; then he would throw his hand back and insert his finger into the gaping place that awaited its turn. In this way we were frequently (all three) dissolved at the same time in a flood of bliss.

Both women become token bodies, enslaved to the Lustful Turk, and the harem becomes a sort of ‘pornotopia’ of delight created for the reader. However, the lull does not hold, and “an awful catastrophe put an end to our enjoyments:” in an act of protest against anal sex, another girl in the harem cuts the Dey’s penis off with his knife and then kills herself. The Dey, unfazed, has his physician cut off the remainder, preserves the ‘members’ (testicles) in glass jars for Sylvia and Emily, and sends them home to England.

On the level of language and appropriateness, The Lustful Turk is not that different from Fanny Hill. Although it is a bit more ‘vulgar’ with its language, it still avoids the common names and graphic description of genitalia such as ‘cunt’ or ‘cock.’ Additionally, it does not touch on many of the sexual acts or extremes that later works would. Like Fanny Hill, the work also places heterosexuality on a pedestal and avoids any reference to homosexuality, even lesbianism. Its main novelty and reason for its success might have been a forthright description of heterosexual anal sex. Even its mention of bondage (the Dey ties Sylvie up and flogs her) has a quite long history in England and Europe as a whole, dating all the way back to the 1500’s

Its main innovation may have been forthright description of heterosexual anal sex. Bondage, especially flogging, had a long history of representation in England, dating even earlier than Curll’s Treatise on Flogging, and was so widespread that it was referred to as le vice anglais (the English vice). On a philosophical level however, The Lustful Turk was terribly upsetting to Victorian moralists—not only does it involve rape, it involves the willing participation of English women in fornication and adultery with an infidel and a foreigner. Nor are Emily and Sylvia punished as they should be—at the end of the novel Emily is working on marrying an “Irish earl, who I have a presentiment will be found worthy of acceptance” and might be able to “erase the Dey’s impression from my heart.” Furthermore, it presents female sexuality in a manner that must have deeply disturbed the Society for the Suppression of Vice, who declared that “women are elevated in the scale of society and the suavity of manners … they have a mild, conciliating, forbearing, and civilizing spirit.”

It was no wonder then, that they brought a legal case against a certain William Dugdale for publishing and selling it. A legal case that would rock the world of English literature to its very foundations and be used by the state to control and punish for over a century.

Find out more, next week!

Sources:

[1] Lustful Turk: Or Scenes in the Harem of an Eastern Potentate — Anonymous (kindle edition)