Paul MacAlindin's Blog, page 4

January 28, 2016

Leading Online

Follow UPBEAT on Facebook

Follow UPBEAT on twitter

Follow UPBEAT on twitterWe conductors are a funny breed; once we get a taste for it, it’s hard to stop. Yes, we’ll tell you that the music comes first, that we are in the service of the composer, that we’re there to ‘help’, but the real reason we want to stand in front of a highly seasoned and professional workforce and tell them what to do, is because we love the electricity pulsing through our veins! We long for the power to shape the orchestra’s sound, exuding charisma through every pore (when it’s there at all) and taking people on the journey from darkness to light that great symphonic music affords us. Most of all, we love the thrill of giving everyone an epic night out.Books on leadership are thick on the shelves, but when I took on musical directorship of the National Youth Orchestra of Iraq in 2008, 99% of my leadership was online. For this, there is little real guidance. Years of fundraising, video auditions, visa and project management burnt through four laptops and thousands of cups of coffee in Cologne’s internet cafes. So how did we do it?Management guru, Charles Handy wrote Trust and the Virtual Organisation back in 1995, a classic that hits at the core of human behaviour in organisations. Trust, he says, ‘is not blind’. We build our relationships best of all face to face, which is tricky when managing an online project team. As English, German, Iraqi Arabic and Sorani Kurdish became our organisational languages, the possibilities for misunderstanding spiralled upwards. I had the relative advantage as a Scot in Germany, of being practised at modifying my English to be slower, clearer and idiom-free: so-called ‘Language Two English’. Having the patience to listen carefully and compassionately (most of the time), led to me questioning, clarifying and summarising often. We tried to get away from emails towards a higher context communication like phone, Skype or face-to-face to pick up emotional clues around our discussions. Though we rarely met face-to-face, when there was a chance, we took it.Handy also mentions that ‘trust needs boundaries’, so we needed to build our online trust, step by step over time. Our tasks tested our response time and accuracy against the reality of a country coming out of war. We often found ourselves negotiating around shattered infrastructures or security issues. Getting the audition videos from across Iraq, for example, hit major technical and logistical barriers which tested our trust in each other, often leading to blind faith. However, the audition process became vital for establishing the players’ wider trust in our fairness, hard work ethic and inclusivity, crucial motivators for driving our musical quality over the years.What happened when stuff didn’t get done well enough, or at all, and emails went unanswered? I would either do it myself or redelegate in order to manage a deadline. Anything could cause this: the wrong tone of email, bad timing, intercultural misunderstanding, lack of local knowledge such as public holidays or some invisible issue to do with hierarchy and internal politics. Or maybe we were just talking to the wrong people?For a leader, all of this backs up over time like a bad drain into Sacrifice Syndrome, the project becomes high maintenance, you lose grasp of your down-time and burn out. For me, running the orchestra sometimes felt like driving a car over a cliff once a week to see if I could land softly. Eventually, I learnt how becoming numb was a sure-fire way to shut my intuition down.For many entrepreneurs, whether socially motivated or not, it’s the the passion to build up a business from scratch that’s deeply thrilling. Our emotional gut energy gives wind to the sails of our intellect, intuition and actions. I kept that passion rolling by failing readily in our high risk environment, learning fast, feeding back into the organisation and taking the team as far as possible with me on that curve.Through my favourite leadership matrix, from Dan Goleman’s book Primal Leadership, I see all communication as emotional, whether we’re conscious of it or not, and open to misinterpretation in an online environment. I break it down like this:Do as I say is good for getting results where people need to be clearly told what to do, as in a crisis. This is fine for clear actions like filling out a visa application or creating an audition video, and works well with carrot-and-stick leadership. But, it’s pretty short term. Online, this style of leadership often became a conversation to clarify what was wanted, so an instruction became relationship-based.Come with me is the much lauded visionary style, with a longer term trajectory and less value on a day-to-day basis. Trust in the orchestra had to be continually reinforced, because the orchestra’s progress over the years couldn’t always be felt. Here, I used YouTube and Facebook to demonstrate our value so that our partners and players could see and hear the tangible growth and alignment with our vision.Democratic leadership is about a question and the patience to listen to the team’s answers, which I wrote on previously for Innovators. This showed how we built trust in each other from the outset and created our shared vision together.We actively promoted ‘people matter’ or affiliative leading in the orchestra courses, as young players needed intensive musical care from our teaching team. However, the online reality was tougher, as we stretched to the limits the relationships we’d built with each other during our annual courses, and make them last till the next course. Going home afterwards had a kind of ‘return to default setting’ effect. Constantly keeping the team focused on results and next steps kept our differences at bay and focused us hard on the ‘why?’ of making music.Do as I do is pace setting, and obviously, leadership for conductors. The joke goes, an orchestra without a conductor sounds pretty good. But a conductor without an orchestra? Pretty awful! The desire to lead doesn’t mean anyone should want to follow us, and here I come to the orchestra’s core reality. Coming out of war, they were desperate for any help to rebuild their musical lives. In online management, intrinsic motivation is, of course, an aspect of success. If they can just switch you off, or worse, ‘unfriend you’, then that’s your influence over. Is somebody testing you to see how much they can get away with? Again, trust has boundaries, and these can be tested, expanded, and rebuilt if necessary. To be honest, leading online with do as I do failed to motivate some team members, whilst others learnt fast and responded with better precision and quality. I should point out that most of our project management was voluntary, so working for the orchestra always added extra pressure to our daily lives. We proved that our achievements came out of a shared vision for the orchestra and what its success meant to us as musicians.When our sixth annual summer course, this time to the USA, was cancelled because of ISIL, I knew that trust with the players had been damaged. Even though this wasn’t my fault, I felt devastated at being caught in Iraq’s unfolding calamity. Boiling my online leadership down to one sentence, I’d say if you promise it, move heaven and hell to deliver it.This article first appeared in Innovators Magazine

Published on January 28, 2016 00:16

Fail-Safe: the Price of Innovation

Beethovenfest Kids Concert with Paul and NYOI, Bonn 2011

Beethovenfest Kids Concert with Paul and NYOI, Bonn 2011 Follow UPBEAT on Facebook

Follow UPBEAT on twitter

Whilst developing the electric light bulb, Edison quipped: “I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.”Tired of gurus telling you that success only comes after repeated failure, and yet you still have to pay the price for failing? That is, of course, a central, and unavoidable paradox of successful innovation.People who can’t help but think radically, who put their necks on the line for their vision again and again, coming up with great ideas, failing often, they’re the ones who take the real risks and pay the real price. Bigger players, the late adopters, wait to see who has the edge, and at their most vulnerable, swipe whatever is going and adapt it to their established business models, leaving the small player, usually some poor sodding freelancer, in the mud. It’s happened to me, and it’s probably happened to you.So, how to protect ourselves and fail successfully at the same time? We could start by removing anyone in our lives who is blocking us, because in order to continually fail, learn and pick ourselves back up for the next round, we need a support system of true believers with as

much stamina as us. Then, we might ask who we really are: incremental innovators, who change processes step by step, like a Kaizen black belt, or disruptive and visionary innovators, like Steve Jobs? Do our bosses really want our creativity and taste for risk, or is that just lip service? Are our customers ready to pull the rug out from under our feet for being too safe, or too dangerous? Will we ever learn to risk making the changes that turn those quantum leaps of the imagination into reality?In 2008, I could risk creating the National Youth Orchestra of Iraq only after decades of experimentation, painful learning and tenacious belief in what I offer as a musician and human being. Beautifully, this was one risk nobody else had the balls or wherewithal to take, and so I attained what academics call unique inimitable advantage. Yes, we should learn from analyses and articles to steer us away from pure folly, but without hard experience and solid faith in ourselves, I reckon we can never learn the art of risk taking, failing and therefore innovating. Most importantly, we’ll never learn resilience. With enough of that, all the lessons we seek will eventually become apparent.For me, faith in oneself is that sense of knowing what is worth committing to without a shred of evidence to evaluate the risks. It’s not instinct, which comes from experience, but rather intuition, staying open to slight signals in the environment and passionate about potential. And if failure thwarts us again, we face a simple life choice: bitterness or wisdom.Of course, every decision sets its price, and Seth Godin’s useful little book, The Dip, asks a couple of key questions about whether or not we’re flogging a dead horse:Is my persistence going to pay off in the long run?When should I quit? I need to decide now, not when I’m in the middle of it, and not when part of me is begging to quit.Tellingly, I set the strategy for the National Youth Orchestra of Iraq at five years, and in year six, we ran out of luck. Writing UPBEAT – the Story of the National Youth Orchestra of Iraq, forced me to re-evaluate my decisions and look hard at what I’d learnt. Did we fail? A thousand times. Did our successes become the stuff of legend? Absolutely.This article first appeared in Innovators Magazine

Published on January 28, 2016 00:04

October 30, 2015

Trying to stay UPBEAT

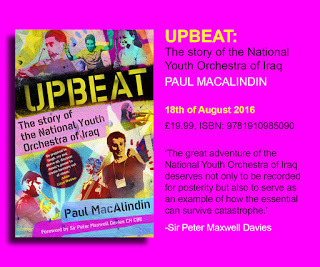

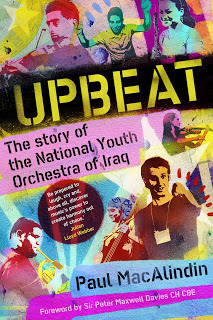

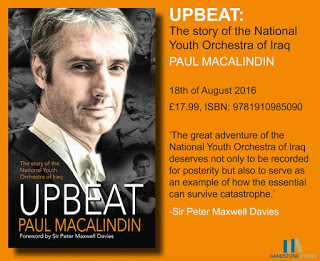

Pre-order UPBEAT: the Story of the National Youth Orchestra of Iraq

Pre-order UPBEAT: the Story of the National Youth Orchestra of IraqJust over a year ago now, the National Youth Orchestra of Iraq’s visit to America was cancelled, and left me, in Cologne, devastated. That’s hardly anything compared to the musicians in Iraq, who are trapped at home just miles away from ISIL. For the moment, they are all still safe, either in Baghdad or Kurdistan. We’re supposed to say “The Kurdistan Region of Iraq”, but that hardly seems relevant any more. Even if ISIL were defeated tomorrow, Iraq can never return to the way it was before. People, and I mean the real people of Iraq, are sick and tired of having their lives continually moved around like pawns and wrecked with impunity.

Since the collapse of the American tour, I’ve been keeping in touch with the players and writing the book on the orchestra from my position as its Musical Director. Though the stories are as numerous as the people involved, I was determined to create a factual account, starting back in 2008, when I saw a newspaper article about the search for a conductor. As the only person involved in the orchestra's daily business over six years, I feel I have a powerful story to tell, and lessons to share.

So, still raw and wounded from the calamity of the ISIL invasion, I sought out a couple of months' refuge living with artist friends, in need of patience and loving support as I mapped out the journey.

Backed up by an archive of every single document, e-mail, press article and media report I've stored over those years, memories bubbled to the surface, jostling with each other for attention. How could I forget this, that, the next? Weaving the several yarns that ran parallel through the book became the challenge, to keep me up all night drawing mindmaps on sheets of coloured A3 paper laid out across the floor. Much rearranging of yellow Post-Its, one for each paragraph of a chapter, made sure the multidimentional threads would ebb and flow around each other authentically, and clearly for the reader.

The reader – who is she? A musician or music lover? A Middle East expert? An intercultural guru? Or a social entrepreneur looking to do something as crazy as this, but in need of insight and guidance? That’s what everyone wants, to change things for the better, pain free. I guess it’s possible nowadays, but most change makers still have to go through the 99% of dirt to find the 1% that really works. Or maybe the reader is just looking for a great story to read, one that actually happened but at the same time contains bizarre elements of luck, paradox and magic realism.

The reader – who is she? A musician or music lover? A Middle East expert? An intercultural guru? Or a social entrepreneur looking to do something as crazy as this, but in need of insight and guidance? That’s what everyone wants, to change things for the better, pain free. I guess it’s possible nowadays, but most change makers still have to go through the 99% of dirt to find the 1% that really works. Or maybe the reader is just looking for a great story to read, one that actually happened but at the same time contains bizarre elements of luck, paradox and magic realism.Once I’d taken each chapter as far as I could, I farmed them out to dear friends from different backgrounds for feedback. Some created highly professional editorial comment, others marked it like school teachers, still more gave me their view on style, political sensitivity and so on. Sean Clayton and John Shea, with whom I’d worked in Montepulciano, David McNally, my old friend from Edinburgh now in Spain, Simon Crookall from Hawaii Opera, David Ramael from BOHO Ensemble in Belgium, Russell Jones from the New York Phil, and many more gave me the food for thought to steer my revisions. Some wanted more emotion, others less. Still others wanted fewer names and acronyms.

I wanted a story whose emotions arose from honesty and compassion, my own strengths and weaknesses, an ordinariness that blossomed from an extraordinary situation. I also banished the words “was” and “were”, two cop-outs when writing in the past tense that can nearly always be substituted for more entertaining verbs, often forcing more interesting sentence structures. I knew that most of the world's readers mentally process text into pictures. I do not. As a musician and conductor, I hear and feel words on the page, and so retraining my prose to become as vivid for visual readers as possible became an interesting challenge.

Once the manuscript had hit about 100,000 words, I started to look for a publisher. I prefer this to self publishing because the book, in a vast ocean of literature, needs every chance to look and feel brilliant. Some sniffing around online produced a list of fifteen publishers, mainly British, who accepted open submissions from unknown authors and may have an interest in the subject matter. Clearly, they are scared of the rising tide of independent self-publishing through sites like createspace.com, and would welcome those with a marketable story back into the professional publishing world.

After I'd laid out the contacts and conditions of submission on Excel, I started pumping out the e-mails and recording the responses. It’s always wise to reduce one’s cold calling log to rows and columns, as this is invariably what your prospects do to you. It allows me to keep a healthy perspective and not feel defensive when rejected. Generally, publishers wanted the first three chapters, a synopsis and a cover letter. When some went on to ask for the whole book, I had it ready.

Within 48 hours, one publisher came straight back, saying this was right up their street. Another two followed up within a fortnight, but being much larger companies, had a longer process for manuscripts farmed out to independent editors for evaluation. On return of a positive verdict, the board would choose which submissions to move forward on.

Meanwhile, I began initial talks with the first publisher, leading to an informal editing process which built our relationship up before deciding to sign with each other.

Because the publishing industry is new to me, I took the time, without rushing into a contract, to phone up distributors, business partners and even benefit from an American author who ran workshops for other authors on how the publishing industry works, as well as negotiating a deal. The key here is to remain transparent with all the interested publishers, because nothing is worse than being a time waster in their evaluation process.

I’m now signed with Sandstone Press in Britain. UPBEAT will come out in the middle of next year, and there is already foreign interest. Sandstone tells me it’s a great book, and we're both working hard to get it ready.

I’m looking forward very much to the cover design and choosing the photos for the two picture sections in the first hardback edition. I have literally thousands from the past six years, so that will be quite a job.

Sandstone asked me to look around a bookstore and reflect on cover designs, so I chose Waterstones in Princes Street, Edinburgh. The music section largely contains pop and rock biographies, with a small, rather unassuming collection of books on ballet and classical music. The whole bookshelf seemed to want to apologise for its presence amidst the veritable candy shop of contemporary novels, exotic travelogues and popular non-fiction. The bestseller, "This is Your Brain on Music", sat quite separate piled up on a table, not terribly nearby.

As a first time author, I feel very lucky indeed to have created something that a publisher wants to take on. This is a new adventure for me, and I’m sure I’ll be doing a lot of talking when the time comes. Indeed, my first interview is scheduled for 2pm today with a journalist from Deutsche Welle.

As well as the story itself, I round the book off with a chapter each on reconciliation in Iraq, the orchestra as social entrepreneur and answer the question, who are the Iraqis? In the meantime, I just hope they stay safe.

For enquiries about the book, please visit:

Sandstone Press

Please feel free to follow the book on Facebook and Twitter:

Tweets by @Upbeat_book

UPBEAT on Facebook

You can also find articles about the National Youth Orchestra of Iraq in five languages at:

NYOI on issuu

For my TEDx talk, go to:

Published on October 30, 2015 03:32

December 25, 2012

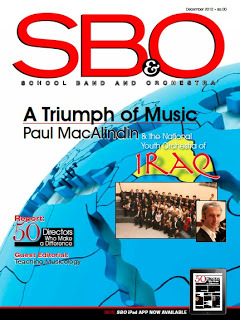

A Triumph of Music: School Band and Orchestra

SBO website

Pre-order UPBEAT: the Story of the National Youth Orchestra of Iraq

This month's edition of School Band and Orchestra interviewed me and Angelia Cho on NYOI:

School Band & Orchestra: What were some of the logistical and conceptual challenges of getting the NYOI off and running?

Paul MacAlindin: In year one, we had no idea who was providing security or where we were rehearsing as we flew into Iraq. It's a last minute culture, and so we were given the Palace of Arts by local government contacts on arrival, who also supplied us with local Peshmerga soldiers, the Kurdistan Region's own army. These were burly young men in uniform patrolling the building and its surroundings with AK-47s. It became a ritual of our bassoon tutors over the years to get photographed holding the weapons. I guess there's not much difference between a bassoon and a Kalashnikov, on some deep level.

SBO: How much of a realistic concern was safety?

PM: Safety is priority number one. You can't concentrate on learning music unless you have the basics in place. Choosing a Kurdish town in the north to hold the course was sensible for the Kurdish Iraqi players, but could mean a long and potentially dangerous journey from Baghdad for the Arab players. Because the Kurdistan region of Iraq is much safer than the rest, this was a logical location for the course.

Once we'd all started to relax into a routine, we started to get to know each other and the town of Suleymaniyah, which was a heartwarming and lovely experience. We were very fortunate to begin our life there.

SBO: Would you talk about the process of recruiting players?

PM: The musicians hear about NYOI through Facebook (www.facebook.com/nyo.iraq)and word of mouth. Auditions have to be done by YouTube. I needed to know what standard the players were at so I could choose suitable repertoire, and obviously, I couldn't take on everyone. There are no course fees, so the players have to be fully financed by the project.

Auditions by YouTube were very difficult because Iraq's infrastructure had been shattered by the war, and wireless capacity was just beginning to be set up. Uploading five minutes of video could take 10 hours, and if there were a power cut, you'd have to start all over again.

SBO: What were your initial expectations, musically?

PM: I had few expectations coming in. I was very clear what I wanted to do in that first two-week course in 2009, but I had no idea how this would work in reality. The repertoire was Haydn 99 and Beethoven Prometheus Overture. I also had a pile of shorter, easier pieces, which I would weave into rehearsals in week one as I got a feel for how they were progressing. There was a lot of ducking and diving, but we pulled together a final concert that the audience was pretty surprised and delighted at. I loved that they burst into applause, not just after every movement, but wherever there were two or three beats rest in the Haydn. This was hilarious fun, and made the whole relationship with the audience come to life.

SBO: What sorts of musical backgrounds do the players in the NYOI have?

PM: Many of the players have no formal teaching, or are not instilled with a pedagogy. There is no exam system, and players coming from certain districts of Baghdad or Kirkuk have to be careful how loud they play in case they get their families into trouble from local fundamentalist authorities.

There are Institutes of the Fine Arts around the country, so the bricks and mortar are there, who provide what support they can. Some of my less financially well-off players have been given their first instrument through such organizations, but then often there is only the internet to download from for further study. Classical music is seen as a basic educational necessity regardless of whether you play classical or Iraqi music, and this takes people up to a lower intermediate level, regarding reading and playing the more popular instruments such as violin. Many of the NYOI players know how to play Iraqi music, but don't tell me, as they see their own traditions as being somehow less significant. This is why every program we do puts an Arab and Kurdish Iraqi orchestral composition in pride of place. Violinists and clarinettists are the most versatile, as they can alter their tuning with a good degree of control and play traditional Iraqi Maq'ams.

SBO: How would you describe the experience of working with students from conflicting ethnic backgrounds and across different languages?

PM: Back in 2009, the Kurdish/Arab/English tutor divide was obvious in week one, as people would simply not speak to each other outside rehearsal. Given that the Kurds don't speak Arabic and the Arabs don't speak Kurdish and only half the orchestra could get by in English, this is not surprising. But once we had a birthday party, and discovered what an irrepressible bunch of party animals we all were, the ice broke and everyone hunkered down with new determination to make the concert happen. Music and party are the two common languages of NYOI.

SBO: Could you elaborate on that birthday party? How did that come together?

PM: It was the Friday at the end of week one, and we were all in an Iranian restaurant that we'd booked to feed the orchestra during our stay. We'd all started sitting at our usual tables outside on the lawn, defined by language, Kurds, Arabs, English speakers. A birthday cake for Boran Aziz, a highly talented young pianist, appeared for her 18th birthday, on that day. After singing Happy Birthday, a violinist and Daff player struck up a tune and we started dancing around in a circle. All the differences melted away and we realised how keen we were to let go and have a good time. Now, every year, someone brings along a Daff, which is an Ottoman drum, and someone else will start playing a local melody on violin or clarinet, two very common folk instruments in Iraq, and we'll all spontaneously start dancing, non-stop for hours on end. And without a single drop of alcohol. I think this first party made everyone feel they could have permission to be young, joyful, and silly while still taking music seriously.

SBO: How would you describe the strategy for getting the NYOI off the ground, and then developing growth?

PM: I think that first year worked with sheer guts and determination. The past four years have been blood sweat and tears, especially for me, but there really is no other way of setting something like this up for sustainability. Although the orchestra intake is better each year, there are still fundamental problems of listening, musicianship and technique that our tutor team – one per instrument – try their best to iron out in our brief annual courses, but this cannot replace the years of neglect that these young people have experienced.

Our strategy is to become diplomats, showing a more positive, united face to the world than it has seen so far, and to reach out to other youth orchestras. Last year, we collaborated with the German Youth Orchestra, Bundesjugendorchester, and this year with Edinburgh Youth Orchestra. Next year will be with the French Orchestre Francais des Jeunes in Aix en Provence. Our values, chosen in a players' workshop in 2009, are love, commitment and respect.

SBO: What do you mean by “an official set of values” for the ensemble?

PM: In 2009, I ran a mission and values workshop with the players, because I needed to know who they were and what they wanted out of this orchestra for the coming years. We asked them to write down anonymously, on pieces of paper, what qualities they valued in themselves, in music, in the youth orchestra, and if they were to run their own youth orchestra, what values would be its foundation. The most common answers were love, commitment, and respect, along with hard work, love of Iraq, and peace clustering around them. So that gave me as good a mandate as possible for how the players themselves saw the orchestra.

In practice, as with any value system, this can be hard to live up to, but at least it's there to refer to, and for everyone to remind themselves what NYOI is about. These are very broad and solid foundations that create a standard of behavior towards each other, especially through hard times.

SBO: How has the course of study and performance for the NYOI evolved since its inception?

PM: The 2009 and ‘10 courses were two weeks of rehearsal in Iraq and one concert. The 2011 course was two weeks in Iraq and one concert, then two more weeks in Bonn, a workshop concert in Berlin, two kids' concerts and one final concert in Beethovenfest. This year, the whole course was in Edinburgh for 3 weeks, with concerts in Glasgow, Edinburgh Festival Fringe and London Queen Elisabeth Hall. We're still trying to create the ideal formula for working.

SBO: Do I understand this correctly then that in some respects the NYOI is as much an advanced music education training program as it is a select performance ensemble?

PM: Yes. It has to be a musical boot camp to skill-up the players and get them through the course and final performance, as there really isn't enough music educational infrastructure to support them in Iraq. Those that make it through the auditions are largely self-taught.

SBO: Have you had the same musicians participating from year to year?

PM: We run annual auditions, just like every other national youth orchestra. The best applicants from each year get in, subject to available places. I reckon about a quarter have been in since the start. The short-term goal is to put on a concert at the end of each course. The long-term goal is to train as many talented young Iraqis as possible so that they will return to Iraq with better teaching ideas and more motivation to start their own ensembles and chamber orchestras, and this is already happening. In that sense, the viral effect of good quality teaching influences Iraqi music making by stealth over the long term future. That we've made it through the first four years is a miracle, but it's the deep impact over the next 25 years that we're thinking about, as well. We can't guarantee that there'll be a musical infrastructure for the future, but we can change the way music education is perceived, one player at a time, and give them a strong feeling of success and achievement.

After four years of getting this baby organization on its feet, we now have rolling interest from various embassies, countries, festivals, and this is all we can do to make sure it has a sustainable future. The orchestra is a paradox from top to bottom, and like all good paradoxes, it works because and not in spite of it's apparent contradictions.

SBO: The “orchestra is a paradox from top to bottom”? Could you expand on that?

PM: The first paradox is why a Scottish conductor based in Germany is doing this. I still don't really know, other than it still sounds like a great idea, and it's easy to fall for the young players and want to try and help them.

The second paradox is how a 17-year-old female pianist in Baghdad rallied considerable support in that first year to get NYOI off the ground. Zuhal has a magnetic charm and is furiously intelligent. We're lucky to have her.

Thirdly, how can a bunch of young people who can't even speak each other’s language, and have been taught to hate each other, sit down in front of the same music and play beautifully together? Because of the discipline of orchestral playing, we have a very secure and productive framework to come together. Having me and the other foreign tutors there also creates a neutral third space between the Kurds and Arabs through which we can mediate and pour our energy safely.

The fourth paradox is between Arab, Kurdish and Western musical culture, but this is also a generation who globally switches between cultures more effortlessly and articulately than ever before. It's a real Generation Y orchestra, with a high awareness of music outside Iraq through the Internet. Taking a very conservative format, the orchestra, and fitting it into a very conservative country within this globally aware context actually fits strangely well.

The final paradox is the most tragic and most important, and that is the suffering of the players themselves. Although there is little evidence on the surface of what they personally have been through, everyone's family has been affected by gas attacks, invasion, tribal tensions, and war. As young people, this is their normality. That comes out in the sound, which has been borne out of their determination to play through dangerous times, in order to shut out the world around them. It's a crazy, tense energy, but one which we can convert into joy together.

SBO: In the bigger picture, what do you think this organization represents?

PM: That's a huge question. I don't know really. The organization is a process. It represents a way of teaching and communicating that is kinder, more creative, more loving than what they've been used to. This has a stealth impact in Iraq, as people gradually realize what the true potential of these young players is, and leads everyone to deal with a highly informed, empowered next generation. The players know how to translate this experience to Iraq in ways I cannot. Diplomatically, we're looking at an orchestra of Iraqis living in Iraq, all with Iraqi passports, but some people cannot let go of the divisions within Iraq, so we deal with resistance to our symbolic wholeness. There's another paradox; a national youth orchestra from a nation that doesn't believe in itself as a whole.

SBO: How does this project differ from other conducting gigs you’ve had?

PM: NYOI will always be a coaching more than a conducting experience for me. Due to lack of experience, the players don't really know how to watch and play at the same time, and if they do, classical conducting technique doesn't have much meaning. I adapt my physical communication to be more energetic and direct than with professionals. My verbal communication is very economical, because it also has to be translated into Kurdish and Arabic. There's a Kurdish and Arab concertmaster sharing every concert, which helps keep a cultural balance. Working with two concertmasters is also a joy, because you're giving two people leadership experience instead of one, and leadership is a key development goal for when they return to daily Iraqi life. I'd say after four years, we've gotten all the lead positions about right.

SBO: How would you describe the impact that this ensemble has had on the musicians, their families and communities?

PM: That's a huge question. I don't know where to begin. In short, the average age in Iraq is about 21. Our upper age limit is 29. Therefore NYOI players, who are about 18-25, are really the current generation of music teachers and performers in Iraq. So those who teach, teach better. Some create ensembles like the Kurdistan String Quartet or the Babagoorgoor Chamber Orchestra in Kirkuk, and those who already play in ensembles like the Iraqi National Symphony Orchestra or the Kurdish String Orchestra, bring their NYOI experience to the rehearsals and performances.

SBO: Have you faced difficulty or skepticism about the concept of playing classical music in Iraq?

PM: The first orchestra in the Middle East was the Iraqi National Symphony Orchestra, founded in Baghdad in 1959. But really, why are we still having this discussion today? The idea that orchestras only belong to the west is something that might have held water 60 years ago, but now, orchestras are a world culture, composers of every background and style are writing for them, and practically every film you see needs one to bring the sound track to life. Even synthetic soundtracks end up imitating them.

Also, the contemporary definition of orchestra is broader than the 19th-century model, with Kurdish and Arab orchestras mixing violins, clarinets, double basses, ouds, nyes, josas up into whatever ensemble does the job of making the music. I'd say that four years on, we're well on the way to integrating diverse Iraqi voices into the programming, language is no longer a barrier with our superb team of trilingual translators, Kurdish/Arabic/English, and the diversity of individuals, regardless of where they come from, or what they speak, is richer than the anodyne characterless conservatoire playing you now get that churns out perfect and perfectly dull musicians for the global market.

SBO: What sort of potential do you see with this ensemble, both culturally and musically? What are the long-term goals of the NYOI?

PM: The energy, the grist to the mill that we bring to each other and our audiences, is irrepressibly joyful and defiant. Even if, for whatever reason, the orchestra were to stop now, it's spirit and meaning would carry on in the hearts of its participants and listeners for decades to come. It's really the beginning of a 30-year arc that I can only see bringing good things to the people of Iraq. Iraq is so focused on rebuilding and attempting to maintain it's fragile democracy that culture is pretty low down on the list of priorities.

And yet, for a post-war country as fragile as this one, I wonder who else but organizations like the NYOI is going to keep it from falling apart? Culture binds us together in common understanding far more powerfully than infrastructure. As Iraqis soul-search for a new identity, music will play its part. Let's not forget that the 21st century will not be shaped by the West, but by other cultures who are comfortable with paradox and see answers in apparent conflicts that we, with our linear thinking, don't understand.

SBO: What particular lessons have you taken from this experience?

PM: The lesson for me is to enter into as many challenges as possible in order to help others grow, because the most important resource I have for getting the best out of people isn't talent, but compassion.

Angelia Cho is a New York City-based violinist and member of The Academy, a program “for musicians who wish to redefine their role as musician and extend their music making from the concert stage into schools and the larger community.” In 2009, 2010, and 2011, Angelia traveled to Iraq as a violin tutor for the NYOI, one of approximately 10 instrument coaches brought in for about two weeks each year. Cho is currently touring with A Far Cry, a self-conducted classical chamber orchestra that she helped found in 2007. In between recent tour stops in Georgia and Louisiana, Cho took a moment to share her experiences in Iraq with SBO.

I traveled to Iraq for parts of three consecutive summers, about two-and-a-half weeks each year. I first heard about the NYOI while doing a fellowship with Carnegie Hall, where one leg of my program was educational outreach. The director of my fellowship program had given my name to an American representative for the NYOI, Allegra Klein, who presented the opportunity to me. Going to Iraq was a pretty scary idea at the time, but I was eventually convinced that I would be safe, and I decided to go ahead and do it.

When I got to Iraq, it was a lot more peaceful than I was expecting. There was some tension between the Kurds and the Arabs in the orchestra and there were some adventurous moments, but the sensationalized violence and chaos that the media loves to report on was basically non-existent. Still, we were all pretty paranoid whenever we went outside. We spent most of our time indoors in the hotel or at the rehearsal hall, but whenever we went outside, the locals were friendly. There was also a lot of curiosity about who we were and what we were doing.

As far as the schedule went, the rehearsals were pretty much allday affairs. We’d wake up in the morning and have sectionals right after breakfast. There were tutors for each instrument; I worked with the first violin section. Sectionals would last about two hours, during which time we’d go through the parts, fingerings, mark the score, and work on rhythm and other areas that might be problematic. The Iraqi musicians had such a wide range of playing levels that it was quite challenging. We’d break for lunch, and then have full rehearsals for another three hours or so. There was also travel time going from the hotel where we were staying to the rehearsal venue, and then time out for meals, so we were basically working with the kids non-stop. In addition, we would give lessons in the evenings, sometimes before dinner and sometimes after dinner, one-on-one, working on whatever individual skills the NYOI musicians needed [to improve].

The first year was really doing a lot of basic work with the musicians. There was a really wide range of musicianship, and some of them had never been in an orchestra or done a string sectional before. In the end, they pulled through for the concert – the concerts were always rewarding. Still, the second year wasn’t like picking up where we left off after the first year, because we had so many new members. Almost half of the musicians the second year were new, having heard about the NYOI purely through word of mouth. By the third year, though, it seemed like some of the more advanced musicians had begun teaching their colleagues.

I thought it was important to give my time freely while I was over there, and they were so enthusiastic about learning anything they could. They were like sponges. They really absorbed as much as they could. Working with them was really touching for me. Some of the Iraqi musicians would stay up all night long downloading videos related to the music we were playing – they hardly went to bed. We would give them a hard time about it, being strict with them and telling them that if they didn’t sleep, they wouldn’t be able to concentrate.

There was a French horn player named Ranya Nashat, who was the most outgoing person in the group. She also spoke very good English. When I asked her why she and her colleagues were staying up all night, she said, “You guys don’t understand what a gift this is for us. Your presence here means so much that we want to absorb every moment, and that’s more valuable than sleeping. There’s no way we’ll know what happens tomorrow.” This a girl who grew up in Baghdad, and still lives there. Ranya told me, “You don’t know what we see every day. My friend was just killed last week.” That put it into perspective for us, and I guess that’s why I went back for the next two summers.

Seeing the way that these kids worked together by the end of each season, I realized that wherever you are, whatever your means or resources, it doesn’t take much to make the most of any situation. Especially in music, where people have a common goal and interest, it doesn’t matter what happened in the past. There was a lot of conflict between the Arabs and the Kurds and the Arabs outnumbered the Kurds. By the end of the session, they were not only working together, but laughing and helping each other, and really learning, trying to pull off something that may have been beyond their scope. Learning from them really was a gift for me. I realized a lot about how necessary it is to reach out to people through what we do. It gave more meaning to my own life as a performer and as an educator. I could be playing in concert venues – I’m on tour right now – but what really gives meaning to what I do as a musician is helping, and feeling useful, needed, and relevant. They made that happen for me. They helped me realize the importance of what I do and why I do it, which is to teach, to pass on what I know to people who are eager to absorb it, and to people who need it. And that place really needs it, more than any other place that I’ve ever been to.

Published on December 25, 2012 07:02

December 8, 2012

The Fit between Sistema and Youth Orchestras

Youth Orchestra Festival Day at Walt Disney Concert Hall (5/14/11)Paul's youtube Paul's soundcloud Paul's facebook

Pre-order UPBEAT: the Story of the National Youth Orchestra of Iraq

"Music has to be recognized as an agent of social development, in the highest sense because it transmits the highest values - solidarity, harmony, mutual compassion. And it has the ability to unite an entire community, and to express sublime feelings"

- Jose Abreu, founder of El Sistema

So ran Abreu’s vision in 1975 when he founded the first ensemble in Venezuela to help protect kids from criminal behaviour, school drop-out and physical danger by creating a utopian orchestral world. Over nearly 40 years, Sistema has given hundreds of thousands of at-risk kids intensive music training, starting with beginners' orchestras from day one, rather than individual instrumental lessons. Teachers are supported by kids, who get involved in mentoring and coaching each other. Thus, local communities of music makers evolve over time into world class youth orchestras like Simon de Bolivar.

Today, many countries are starting to copy Sistema. It’s challenging, expensive and intensive, the vision has to fit the culture, but their leaders are passionately driven. They too support at-risk kids in poor and dangerous areas where music could lead to brighter futures as rounder, better educated adults. Independent research shows that school attendance, criminal statistics, learning ability and many other social factors improve where Sistema is present.

So, if Sistema is happening in your town, alongside your established local, county or national youth orchestra, how do they fit together? As more and more kids from Sistema audition for these youth orchestras, they will enter a competitive environment with the hierarchy inherent in all orchestras alongside kids who have more money and better provision than them.

Who then is going to give them the instrumental support and finance their participation? What are the emerging solutions?

Santa Anna Suzuki Strings

„Our goal is to raise children in at-risk communities by putting a violin in their hands as early as age 3“

An Hispanic American violinist who trained with the Santa Anna Suzuki Strings, recently became their first player to join the mainly Asian American Community Youth Orchestra of Southern California. Living physically close to, but economically apart from his peers, he also mentors in the Santa Anna programme and wants to study music at university. The contributor of this story added:

„The problem is not one of lacking the funds to support such musical communities and alliances. It is one of revealing resources that were overlooked and evolving a new ecosystem of relationships between organizations. Even when forces seem impossibly entrenched, it is the many small creative efforts to plant those first seeds that break through initial resistance and gain future momentum.“

Batuta

Batuta, the Columbian programme similar to El Sistema serves kids who are socially and economically excluded from existing music education. They also co-ordinate encuentros, massive collaborative music projects such as the 900 kids in the Cali region who played in an aircaft hangar to mark the 90th anniversary of the Columbian Air force.

„Every program in that area worked hard on the same music for months, with Batuta sponsoring professional development for faculty of all programs, to ensure success at their big shared event. Trust and collaborative practices were built, and now they continue to collaborate in projects years after the encuentro.“

Music Hubs

Music Hubs in England, who allocate funds for local music education, are responsible for strategically integrating a broad range of partners, some of whom sit on their steering committees. Sistema projects and established youth orchestras can find new ways of collaborating through these to ensure instrumentalists flow from one to the other, but the leaders of Hubs must be open enough to support this. Both Hubs and Sistema are relatively new to Britain. However, growth is happening fast. Scotland has just alllocated 1.325 million pounds for Sistema work in Glasgow.

Community Opus Project

A youth orchestra setting up its own Sistema programme is rare. After all, it’s a lot work and money, and existing resources are continually stretched. It could also require a radical reshape of structure, mission and values.

However, after noting that their kids came from affluent areas, San Diego Youth Symphony (SDYS) sets out to make music affordable to all. Their Community Opus project starts Hispanic American kids on instruments in elementary school, so that they are ready to apply to youth orchestras by the time they reach high school. In October 2010, the project gave free lessons and instruments to 70 kids in Chula Vista. By 2011, this had expanded to 250 kids, 20 of whom went on to join the Debut Strings Orchestra of SDYS. Those that couldn’t afford membership, were supported by scholarships.

What's the future?

Nascent Sistema programmes still face many questions in the developed world.

How should Sistema projects interpret their role as feeders for existing youth orchestras?

Will the success of one influence how the other measures success?

Who pays for musically gifted Sistema kids from poor families to join and sustainably participate in more affluent youth orchestras?

Would limits on this support be seen as a social failure by Sistema, or a social success by others?

Will Sistema projects build their own senior orchestras instead?

And why must many youth orchestras accept a majority of players whose families can privately afford instruments, tutors and courses in the first place?

If these two movements in music education can collaborate on the ground level, financially, strategically and structurally, then there's a chance these questions can be answered for the benefit of all kids.

By perceiving Sistema as either a music or a social programme, one faces the same paradox that the National Youth Orchestra of Iraq knows. Are we about reconciliation or music, rebuilding culture in Iraq or major cultural diplomacy, East or West? The answer is all of the above, and one happens because of the others. An enlightened funder understands this.

With many thanks to Lauren Widney, Marion de Mello Catlin, Eric Booth, Cynthia Faisst and the Linkedin Sistema Global group for helping me with this article.

To find out more about Sistema teaching practice and resources:

YOLA resource library

This article is a follow on from my original thoughts:

The Fit between Sistema and Youth Orchestras

Published on December 08, 2012 15:47

November 20, 2012

Supporting Youth Orchestras: Funding, Parents and Alumni

Pre-order UPBEAT: the Story of the National Youth Orchestra of Iraq

In a European Federation of National Youth Orchestras workshop last Friday in Apeldoorn, we were discussing fundraising for youth orchestras and how alumni and parents tie into this.

In the US, where private financing is the rule, many youth orchestra websites simply ask for donations. Here's my survey of some of the more creative ideas for developing alumni, fundraising and parent power. I've mostly chosen youth orchestras that are independent of professional orchestras or music schools.

A minority are engaging alumni or parental volunteering intensively through their website, but this may not be an indicator of real activity, which could be promoted in other ways. I'm just putting this out as a resource.

Alumni engagement:

Alumni tell their story:Phoenix Youth Symphony

Honoring Alumni biographically:DC Youth Orchestra

Time-capsule gallery of alumni over the decades:Central Kentucky Youth Orchestras

Honoring alumni at a dinner on video:Boston University AlumniBoston University Music Alumni sets up program

Developed alumni association:Greater Twin Cities Youth Orchestras

Missing alumni - where are you now?Albuquerque Youth Orchestra

Cool fundraising ideas:

Your car's a write-off? No worries, we'll turn it into a donation:Arvada Centre

Donation,alumni profiling and volunteering portal combined:Chicago Youth Symphony Orchestra

Donor/sponsor benefits visual:American Youth Symphony

Online per-purchase donations:Orange County School of ArtsMetropolitan Youth Symphony

Stock/Securities donations:Orange County School of Arts

Gifts of future assets you don't have to think about:Sacramento Youth Symphony

Wishlist:Youth Orchestra of Palm Beach County

Contact your employer for a matching gift:Elgin Youth Symphony Orchestra

New partnerships through fundraising for others:Greater New Orleans Youth OrchestrasFlorida Symphony Youth Orchestra

Community reward cards:Kalamazoo Junior Symphony

participatory fundraising:Southeastern Minnesota Youth Orchestras

Fundraising for building repairs:Albuquerque Youth Symphony

Annual Playathon:Harrisburg Symphony Youth Orchestras

Private dollar for dollar matched funding:Youth Orchestras of San Antonio

Funding scholarships:Youth Orchestra of the AmericasFlint Institute of Music

Selling ornaments, CDs, silent auction:Youth Orchestras of Prince William

Corporate and Business Sponsorship Program breakdown:Maple Valley Youth Symphony Orchestra

Checklisting benefits for kids and community:Milwaukee Youth Symphony Orchestra

Marketing as fundraising:

Two-tier public membership with benefits:Phoenix Youth Orchestra

Targeting young professionals as Friends:Boston Youth Symphony Orchestras

Public access to youth orchestra apparel:Youth Orchestra of Bucks County

Parent power:

Snappy, to-the-point Parent Network page:Louisville Youth Orchestra

Thanking the volunteers:American Youth Symphony

Developed Parent Support Org:Orange County School of Arts

Getting parents engaged with their kids' participation:Elgin Youth Symphony

Contacting volunteers with management functions:Grand Rapids Youth Symphony

Mission & structure of a parents' association:Bellvue Youth Symphony

Detailing volunteer job descriptions:Bellvue Youth SymphonyStamford Young Artists Philharmonic

Using volunteerspot.com:Spokane Youth Symphony

Anyway,I hope this is an entertaining and useful bunch of ideas that will improve the community involvement and funding of our orchestras. If you have any other ideas or opinions on how these themes can be developed, please do share.

Cheers

Paul

Published on November 20, 2012 19:24