David E. Fessenden's Blog

September 13, 2022

Here’s a split you really want to avoid

Photo by David Hofmann on Unsplash

Photo by David Hofmann on UnsplashNo, I’m not talking about a gymnastic split — but at my age, I probably should avoid that, too! What I’m talking about is splitting a verb and its modifier with a noun — usually the noun that is the object of the verb. Let me explain what I mean: we often use verbs and modifiers in our writing, such as “look over” or “go around.” In these two cases, we take a verb (“look” or “go”) and use a preposition (“over” or “around”) to modify, or enhance, the verb. The verb says what action is being done, and the preposition is acting as an adverb, explaining how or where the action is being done. (Sorry to get into so many grammatical terms; I’ll try to use them sparingly from here on.)

You often have to split these verb/preposition combinations by saying, “Let’s look this over,” or “She turned it around.” When single, simple words like “this” and “it” split them, it’s no problem. It’s not even a problem when you split them with two or three words: “Let’s look this contract over,” or “She turned the plastic bottle around.” The sentences are still understandable, though some writers might prefer to avoid the split, even when it’s just two or three words.

It’s when we split these noun/preposition combinations with a long noun phrase that things really start to get messy: “The president decided to give the plan to raise taxes on the middle class up.” Would it not be better to say “The president decided to give up the plan to raise taxes on the middle class“? Of course, there are other ways to do this. You could replace the verb and modifier with a single verb, saying, “The president decided to drop the plan to raise taxes on the middle class.” Or you could rephrase the whole sentence, such as, “The president decided that the plan to raise taxes on the middle class was not worth pursuing.”

Both of these alternatives avoid the use of the verb-modifier combo altogether, and that’s too bad, because it’s a legitimate grammatical construction — as long as you don’t split it too far apart. How far apart is too far? That’s for you to decide — you’re the writer!

September 8, 2022

Hey, let’s split some infinitives!

Here’s another thing your grade-school English teacher wants you to worry about: split infinitives.

Photo by Mikhail Nilov on Pexels.com

Photo by Mikhail Nilov on Pexels.comSome people have no idea what a split infinitive is, and they are happy souls. But for the rest of us, let’s just remember that a split infinitive is NOT grammatically incorrect. It cropped up in 19th-century grammar textbooks as an “error,” but has been routinely ignored by professional writers ever since.

If you are dying to know what it is, here you go: an infinitive is a verb that has “to” before it, that’s all. Like “to be or not to be.” If Shakespeare wanted to drive an English teacher crazy, he would have written the phrase as “to be or to not be,” and he would have created a split infinitive. The adverb “not” is placed between “to” and “be,” splitting them, and to some people’s minds, the meaning of the sentence has been destroyed. But somehow, we manage to understand what the author is saying, even if that little adverb is intruding into the intimate embrace of “to” and “be.”

Why this was ever seen to be a problem is beyond me, because we routinely split other two-word verb phrases with “not” (and other adverbs), and the walls do not come crashing in. The future tense of “be” is “will be”; so if Hamlet commits suicide (which, by the way, is what he is contemplating in “to be or not to be”), he “will not be” alive. Why is there no outrage over splitting a future tense phrase? I suppose we could avoid splitting the verb phrase “will be” by saying, “he will be not alive,” but that seems decidedly awkward. Should we then, like Shakespeare, put “not” before the verb phrase, and say, “he not will be alive”? Of course not! But that is the very suggestion some English teachers use to correct split infinitives!

Let’s try a sentence that uses another adverb — “quickly” — to split the infinitive. “He advised us to quickly decide which road to take.” We could say, “He advised us to decide quickly which road to take,” and that would be fine, though possibly a little awkward in its phrasing. (Awkward phrasing seems to be of little concern to English teachers, though it is of great concern to writers.) Worse yet, some self-appointed grammarians insist that the most correct way is to put the adverb before the verb phrase, making it “He advised us quickly to decide which road to take,” which is not only awkward, but ambiguous, because we don’t know if the advising is being done quickly, or the deciding.

So feel free to split those infinitives, and if anyone challenges you on it, laugh in their face!

My next post will show how splitting some verb phrases with nouns (usually the object of the verb phrase) can and often does lead to ambiguity and awkward phrasing. So English teachers, listen up! This really is a split you want to avoid.

February 17, 2022

Jump-Start Your Creativity!

There’s an old story that a beginning writer once asked a veteran author how he kept coming up with writing ideas. The veteran grabbed the young man by the shoulders, shook him fervently, and said with a tone of desperation, “How do you stop coming up with ideas?!”

There’s an old story that a beginning writer once asked a veteran author how he kept coming up with writing ideas. The veteran grabbed the young man by the shoulders, shook him fervently, and said with a tone of desperation, “How do you stop coming up with ideas?!”

The point of the story is that experienced writers often get more ideas than they can possibly follow up on, and the last thing they need are more of them! But those same writers will admit that they sometimes go through creative dry spells, where they have no ideas — or worse yet, the ideas they have don’t seem to pan out. Whether you are at the too-many or not-enough idea stage, there are a number of ways you can jump-start your creative engines, so that you can have more ideas, develop the ideas you have, and choose the best out of the bunch. Check out the chapter on brainstorming in my book, Concept to Contract. I recently read a very perceptive quote from C. D. Jackson: “Great ideas need landing gear as well as wings.” We need to think through all aspects of an idea before we try to implement it — the same way an aeronautical engineer thinks through the design of a plane so it will not only get up in the air, but also safely back to earth. In my own experience, I’ve found that if I try to work with an idea at the “kernel of thought” stage — the “Eureka!” moment that we all have once in a while — the idea either loses steam or produces mediocre results. The way to get an idea to the point of implementation is to take it through the brainstorming process, where every facet of the idea is analyzed and applied to real life.]]>

February 15, 2022

Christ: The Source of Creativity

I had a poor sort of a mind, heavy and cumbrous, that did not think or work quickly. I wanted to write and speak for Christ and to have a ready memory, so as to have the little knowledge I had gained always under command. I went to Christ about it, and asked if He had anything for me in this way. He replied, “Yes, my child, I am made unto you Wisdom.” I was always making mistakes, which I regretted, and then thinking I would not make them again; but when He said that He would be my wisdom, that we may have the mind of Christ, that He could cast down imaginations and bring into captivity every thought to the obedience of Christ, that He could make the brain and head right, then I took Him for all that. And since then I have been kept free from this mental disability, and work has been rest. I used to write two sermons a week, and it took me three days to complete one. But now, in connection with my literary work, I have numberless pages of matter to write constantly besides the conduct of very many meetings a week, and all is delightfully easy to me. The Lord has helped me mentally, and I know He is the Savior of our mind as well as our spirit.

So if your creative well seems to have run dry, I want to point you to the Fountain of Living Water—Jesus. It’s one of the things I learned from the kindergarteners in Sunday school: whenever the teacher asked a question, they would always answer, “Jesus!” And they were right—the answer to every question is Jesus. He is our All in All. ]]>

January 9, 2022

Four Kinds of “Questionable” Discussion Questions — and How to Avoid Them

Writing discussion questions at the end of a book chapter, or as part of a Bible study or curriculum, is far more complex than most authors seem to realize. First of all, there is the range of knowledge in your potential audience. You need to write questions that are simple and straightforward enough to be understood by newer believers, but challenging enough to cause a seasoned student of the Bible to think. Second, you need to have a mix of question styles — ones that directly address the specific content of a Scripture passage or the book’s chapter, and others that ask how a particular truth applies to the reader’s life.

With these issues to navigate, you can see that making good discussion questions has its challenges. But you should do fine if you avoid certain “questionable” questions. Let me describe a few of them:

Questions that don’t breed discussion. A question that can be answered yes or no, or invites a one-word response, shuts down a group discussion, rather than stimulating it. (This why it is referred to as a “closed” question.) For instance, “Who betrayed Jesus in the garden?” is both a simplistic and a dead-end question. It might be okay if you are writing curriculum for the primary class, but it is unlikely to lead to a lively debate in an adult Bible study. You might ask a closed question if it is a challenge — a question that may (gently) call for confession, like “Do you have trouble maintaining a regular habit of prayer?” But then follow it up with some analysis of the problem: “What changes in your life might improve your prayer time?” Needless to say, challenge questions need to be few and far between, and sprinkled with grace. Frequent and heavy-handed discussion questions can make the group wonder if they’ve stumbled into a police interrogation!“Altar call” questions — the kind a preacher makes just before he asks his audience to “walk the sawdust trail.” You know what I mean: a question that presses for a decision, an immediate response, such as, “Will you resolve to love God more fully?” It’s a great thing to ask at the end of a sermon, but not as a discussion starter! (Besides, the question demands a yes; what if the person wants to say no?) Most importantly, though, an “altar call” question it doesn’t invite the reader to deep reflection. Better to ask a question like, “If you resolved to love God more fully, how would it affect your daily routine?” Subjective questions about objective truths. A subjective question is fine if it refers to personal feelings or actions, such as “What would you have done in Paul’s situation?” Such questions have limited value, though they help the reader relate to the passage being read. But questions like “What does this passage mean to you?” are dangerous, inviting a private interpretation of Scripture. When faced with this very question in a Bible study, a well-known Christian teacher responded, “I don’t care what it means ‘to me,’ or to anyone else, for that matter. We should be asking what the Holy Spirit, speaking through the biblical author, intended it to mean.” Amen! I would only add that the question may have simply been poorly worded, and its intent should have been, “How does this passage apply to your life?” — a perfectly legitimate thing to ask!Ambiguous questions. Are you asking things like, “What are the three most important points of this topic?” It may be obvious to you what three points you are referring to, but possibly not to the reader! Asking, “How does Jesus reveal God’s glory?” is a question that could have a million answers, and the group may struggle to understand your point. It might help in this case to provide a biblical definition of the word “glory,” and then ask a more specific question: “What are some of the things Jesus did on earth that revealed God’s glory?”Even if you are watching for these four kinds of “questionable” questions, they can often sneak in under your radar. it helps to have others read your questions, or better yet, try to have a group hold a discussion with your questions. After I started writing a study guide for a published book, a local church did an adult Sunday school class based on the book. The teacher graciously agreed to use my study guide, and gave me feedback on the class response to various questions. It was invaluable! Don’t ever be afraid to put your discussion questions to a real-life test.

September 12, 2020

What’s a nice Christian boy doing on a Jewish newspaper?

I sat across the desk from Dr. Brown, head of the communications department at Buffalo State College, with a mixture of hope and dread. I was there to receive my senior-year internship in journalism, and I had my doubts that he would understand my dilemma.

“You see, Dr. Brown,” I began hesitantly, trying to keep my voice from quivering, “I’m not sure I want an internship on a regular newspaper.” I forced myself to make eye contact with this man who was the very soul of a hard-bitten journalist. “I’m interested in Christian journalism.”

“Ah, religious journalism!” I noted with an inward smile his nimble change in terminology, but I was not at all ready for his next statement. “I have just the assignment for you: the Buffalo Jewish Review.” He must have seen the utter shock on my face, because he added with a grin, “I’m sure it will be a real learning experience for you.”

I walked out of the office in a daze. And when I told my classmates about it, they thought it was a great joke — including those who were Jewish. Apparently the Buffalo Jewish Review was not exactly a plum assignment. Most of the students were vying for a spot on one of the daily papers, or maybe one of the larger suburban weeklies. A small regional weekly that specialized in the news of the local Jewish community appeared to be distasteful to skeptical college students.

Of course, I had a different concern over the internship: would the editor of a Jewish newspaper be willing to accept a born-again Christian on his staff? I need not have worried; Steve Lipman was a great guy to work for, and (as I later discovered) his best friend was active in a Baptist church!

My first assignment was to cover a protest by a group of college-age activists over a theatrical performance they felt was anti-Semitic. That ended in a few arrests and charges of police brutality. A photographer came with me and took some dramatic shots. The story ended up on the front page — with my by-line.

Many of the news events I wrote about were more run-of-the-mill, but my lack of knowledge of Judaism usually kept them from being dull. One lady I interviewed for an article about a Jewish cultural event was perturbed over the ignorant questions I was asking and said, “Your parents didn’t take you to temple very often, did they?” No, m’am, my Episcopalian parents did not take me to temple very often! But it was a unique opportunity to learn about Judaism.

And a few of the stories were — well, unusual to say the least. I was assigned to interview a Jewish woman who was active in the environmental movement, including protection of endangered species. Imagine my surprise when I was met at the door by a live wolf!

The culmination of the internship was staying up till four a.m. one night with Steve as we waited for election results from Israel. While my classmates were reporting on flower club meetings and waste-treatment plant renovations, I was able to get a by-line on an international news story. So I guess I had the last laugh!

December 20, 2019

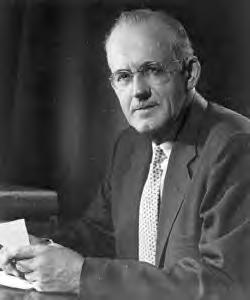

A.W. Tozer on Christian Writing

I describe his writing as refreshing, but don’t get the wrong idea. It is often less like drinking a cool glass of water and more like a splash of cold water in the face. (And don’t we all need a spiritual kick in the pants sometimes?) And yet he always seems to “bind up the bones he has broken” with an encouraging word. I’ve heard some complain that Tozer’s writing is too strong and harsh, but I am reminded that the apostle Paul was accused of the same thing. Seems to me that Tozer had that unique capacity to “comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable”!

James Snyder, in the authorized biography, The Life of A.W. Tozer: In Pursuit of God, includes a full chapter on Tozer’s practices as a writer. There is a lot we can learn from him, especially in his example of striving for excellence and setting high standards for himself. He once turned down an offer from one of the major publishers of his day to publish a collection of his editorials, because he felt they needed to be rewritten, and he didn’t have time to do it. (He later carved out the time to compile and reedit several volumes of essays.) He also never allowed “transcripts” of his sermons to be published (a common practice among preachers today), because, he said, preaching and writing are decidedly different.

Tozer felt that writing a book was an important task, and he urged Christian authors to get their marching orders from God. “The only book that should ever be written is one that flows up from the heart, forced out by the inward pressure,” he said. “Don’t write a book unless you just have to.”

When invited to speak to a group of Christian writers, he surprised the group by delivering a strong argument against popular Christian fiction, saying that it tended to imitate the world and sought only to entertain. The result, he concluded, was fiction that was “unrealistic, affected and false.” What would he think of today’s Christian fiction, I wonder?

I don’t think Tozer was necessarily against fiction, because his writings are peppered with quotes from and admiring comments about the fictional works of Shakespeare, among others. His concern and criticism was reserved for the shallow, simplistic and trite religious drivel being cranked out by some Christian publishers, to slavishly follow the lead of the shallow, simplistic and trite secular drivel being cranked out by secular publishing houses. Besides, Tozer was writing sixty years ago. I believe that today we are seeing Christian fiction produced that is imaginative, original, and profound — along with a lot of imitative drivel!

Tozer argued that the only way to produce material of real depth and spiritual insight, which focused on the eternal rather than the superficial and trivial, was to begin with disciplined Bible study and prayer. He followed this up with good research and with careful wording, often writing and rewriting sentences over and over to keep out the excess verbiage and vague phraseology. “Hard writing makes for easy reading,” he often said.

If there is one supreme thing that Tozer taught me about writing (as well as all aspects of my Christian life), it is simply this: watch your motives. Whenever we start thinking of developing our reputations or making big money through Christian writing, we can be sure that real ministry is going to get lost in the shuffle. Besides, if you want to make big money, forget Christian writing; dig ditches — it pays better!

December 19, 2019

Step 1: Engage Brain

I have re-discovered something about writing and thinking: in order to  write well, you need to engage your brain. OK, OK, so it’s not that profound; it’s not a “stop the presses!” moment. I never said it was. But it has struck me anew just how little we (I should say “I,” but I’m hoping you relate to this) really think deeply about the problems, possibilities and issues of our daily lives. Part of the reason for this is surely that thinking—pondering, musing, analyzing—is hard work, and we (and here I really should say “I”) are mentally lazy. Deep down, we would really like to just have the words flow without thought, wouldn’t we? The problem is, words without thought tend to be shallow, hackneyed clichés that fail to communicate well. Remember what the poet Sheridan said: “Easy writing’s vile hard reading.” Another reason we do less deep thinking today is our distraction-prone culture. Social media is often cited as the main culprit, but there are plenty of other factors that deserve blame: postmodernism’s muddling of fact and opinion; our love for sound bites and talking points over reasoned discourse; and the proliferation of more and more sources of information—and disinformation. So how do we overcome distractions and our natural inclination to avoid the hard work of deep thinking? Ironically, I have made a second re-discovery about thinking and writing, the flip side of the first: a great way to engage your brain is to write! A central principle of communication is that language (spoken and written) is inseparable from conceptual thought. We think in words far more than we may realize, and all our writing is a product of our thought processes. So when you decide to do deep thinking, have a notepad and pen handy, and write out your thoughts. (Yes, you could tap it out on a keyboard, but it makes you more vulnerable to some of those cultural distractions.) Are the words that I write down while thinking deeply going to be read by anyone else? Maybe not, but write as if they are. When you work to make your written thoughts understandable to a stranger, you will find that it creates new patterns of thinking, and helps you avoid shallow reasoning and cliché-ridden mental habits. As I’ve been thinking (and writing) deeply about my new business, I am seeing previously ignored details that I can now deal with and potential pitfalls that I can now avoid. Because I have written down my thoughts as if explaining them to a stranger, I have been able to use these notes as a source for promotional/marketing copy for my company. Nothing gets wasted. I encourage you to make a regular habit of deep thinking, accompanied by careful writing; it will lead to freshness of thought and clarity of expression. And if the notes you make from your great and profound ideas result in publishable text, all the better!

write well, you need to engage your brain. OK, OK, so it’s not that profound; it’s not a “stop the presses!” moment. I never said it was. But it has struck me anew just how little we (I should say “I,” but I’m hoping you relate to this) really think deeply about the problems, possibilities and issues of our daily lives. Part of the reason for this is surely that thinking—pondering, musing, analyzing—is hard work, and we (and here I really should say “I”) are mentally lazy. Deep down, we would really like to just have the words flow without thought, wouldn’t we? The problem is, words without thought tend to be shallow, hackneyed clichés that fail to communicate well. Remember what the poet Sheridan said: “Easy writing’s vile hard reading.” Another reason we do less deep thinking today is our distraction-prone culture. Social media is often cited as the main culprit, but there are plenty of other factors that deserve blame: postmodernism’s muddling of fact and opinion; our love for sound bites and talking points over reasoned discourse; and the proliferation of more and more sources of information—and disinformation. So how do we overcome distractions and our natural inclination to avoid the hard work of deep thinking? Ironically, I have made a second re-discovery about thinking and writing, the flip side of the first: a great way to engage your brain is to write! A central principle of communication is that language (spoken and written) is inseparable from conceptual thought. We think in words far more than we may realize, and all our writing is a product of our thought processes. So when you decide to do deep thinking, have a notepad and pen handy, and write out your thoughts. (Yes, you could tap it out on a keyboard, but it makes you more vulnerable to some of those cultural distractions.) Are the words that I write down while thinking deeply going to be read by anyone else? Maybe not, but write as if they are. When you work to make your written thoughts understandable to a stranger, you will find that it creates new patterns of thinking, and helps you avoid shallow reasoning and cliché-ridden mental habits. As I’ve been thinking (and writing) deeply about my new business, I am seeing previously ignored details that I can now deal with and potential pitfalls that I can now avoid. Because I have written down my thoughts as if explaining them to a stranger, I have been able to use these notes as a source for promotional/marketing copy for my company. Nothing gets wasted. I encourage you to make a regular habit of deep thinking, accompanied by careful writing; it will lead to freshness of thought and clarity of expression. And if the notes you make from your great and profound ideas result in publishable text, all the better!

June 28, 2018

Ever Heard of “Citation-Stacking”?

[image error]One of my courses in college required me to buy a textbook which was  never discussed in class (and never cracked open, for that matter). An upperclassman let me in on the secret: the book was written by a friend of the professor, and was included in the list of required textbooks simply to give his friend a boost in sales.

never discussed in class (and never cracked open, for that matter). An upperclassman let me in on the secret: the book was written by a friend of the professor, and was included in the list of required textbooks simply to give his friend a boost in sales.

Some academic journals, it seems, are doing something similar through a scheme called “citation stacking.” Here’s how it works: the more often an academic journal’s articles are cited, the higher the journal’s reputation and influence, theoretically. The rumor is that some journal editors are pressuring their contributing authors to include more citations from their own journal’s articles, thereby “stacking” their editorial content with self-promoting citations. It appears that this fanatical drive for citations is fueled by some number-crunching group out there which counts up how many citations each journal receives every year, and then assigns an “impact factor” to each periodical. Woe to the poor editor whose journal has a low “impact factor” (i.e., fewer citations)—heads will roll!

This monitoring group for journal content recently slapped the hand of 20 different journals for “citation-stacking”—having too many articles which cite their own publication. It makes me feel sorry for the editors of super-specialized periodicals (like the “Journal of Diseases of the Left Earlobe” or something), whose articles hardly ever get cited in other journals. Doesn’t it make sense that there would be a lot more self-citation in the journal of a very specialized field of study? I only hope that the “citation police” take that into account!

Unless you’re an academic author, you’re probably wondering what all this has to do with you. Is there some form of “citation-stacking” in popular magazine and book publishing, especially Christian publishing? Well, in a way, yes. When I included a bibliography in one of the books I wrote, the publisher asked that I add in a few titles by their publishing company.

Is it self-serving? Sure, it is—just as self-serving as authors whose books include a list of other books they’ve written. Is it a bad thing? Not really. I had no problem with adding to my bibliography the books my publisher suggested, because they were good books by good authors, and they related directly to the topic I was writing about.

I suppose if a publisher asked me to remove a competing publisher’s books from a bibliography, solely because they were a competitor’s titles, I might refuse, but I’ve never heard of that situation. Are you aware of any other practices in Christian publishing similar to “citation-stacking”? If so, please comment and let us know.

June 19, 2018

Five Rules for Internet Research

Photo by Michael Kubalczyk on Unsplash

Photo by Michael Kubalczyk on Unsplash

I recently read an article suggested by my web browser on the rising number of rent-burdened consumers. I learned that “rent-burdened” is a commonly used term, meaning a renter whose monthly housing costs were more than 30% of their income.

Yeah, I know, not very fascinating; economics for most people is about as exciting as watching paint dry. But bear with me; this is not about economics, but about research.

Anyway, I was so interested in the problem of being “rent-burdened” that I searched for another article—just a glutton for punishment, I guess. And there, at the top of the search results was another article, which spoke about how the number of rent-burdened households was falling, not rising! How could this be?

The other author was using the same definition of “rent-burdened,” so that wasn’t the problem. The two articles were written six months apart, and it’s doubtful that the figures could change in that short a time. After a long analysis of both articles, I found that the author talking about the falling number of rent-burdened households was using current figures, but the “rising” author was using figures that were three to seven years old. Was this author just incompetent, or pushing an agenda? Well, I’m going to name names: the article was published by Pew Charitable Trusts, an organization that ought to know what it’s doing.

My point is the first rule of internet research: Use multiple sources when you research a topic. That’s a good rule for any research, but especially for the Internet.

The second rule of Internet research applies here as well: Check the dates. In this case, the article was less than two months old, but the statistics they used were from three to seven years earlier.

The third rule is Check the authorship. Is the article from a respected information source, or just some joker with a blog? We should have been able to trust this article, but in this case, Pew Charitable Trusts let us down.

The fourth rule, unfortunately, appears to apply here as well: Check for obvious bias. Are multiple viewpoints presented, or is the information one-sided? The Pew article was dated April 2018, but it gave the results of a survey conducted between 2011 and 2015 by (surprise, surprise) Pew Charitable Trusts! One wonders why Pew would wait three years to issue these survey results. If they had issued them in 2016, however, it would have highlighted the bad economic conditions in the middle of the 2016 presidential race. Was there a two-year delay in reporting these figures in order to avoid giving more ammunition to one of the presidential candidates? Curious.

Finally, the fifth rule is Check the quality of the website and its content. Granted, this is a somewhat subjective thing, and does not apply to the Pew article. Their website is very nice-looking, and the article was well-written with no typos that I could see. But usually, if a website has bad information and unreliable research, the quality of the writing and the website design is likely to be pretty bad, as well. But let me add that this rule is not absolute. A good-quality site and well-written material could have bad information, and a slap-dash, poorly written website might have accurate information. But it’s more likely to be the other way around.

Next time you see an article online by Pew Charitable Trusts, give them another chance. Nobody’s perfect. But when doing research on the web, use these five rules to evaluate any material you find, and you won’t go wrong.

The Lord spoke the world into being. His infinite creativity is seen in the unbelievable diversity and intricacy of the physical world. And the Book He gave to us is a perennial best-seller! In light of all this, His children should be the most creative people on the face of the earth. If we then struggle with creativity—and I cannot believe I am alone in this—I must conclude that it is due to the operation of a different spiritual law: “You have not because you ask not.” Let me share the experience of A.B. Simpson, a prolific author of the 19th century:

The Lord spoke the world into being. His infinite creativity is seen in the unbelievable diversity and intricacy of the physical world. And the Book He gave to us is a perennial best-seller! In light of all this, His children should be the most creative people on the face of the earth. If we then struggle with creativity—and I cannot believe I am alone in this—I must conclude that it is due to the operation of a different spiritual law: “You have not because you ask not.” Let me share the experience of A.B. Simpson, a prolific author of the 19th century: Tozer (author of numerous Christian books, including the classics, The Knowledge of the Holy and The Pursuit of God). I have to say he is my favorite Christian writer. Whenever I am feeling spiritually dry, I can always find refreshment in one of his essays or books. Sometimes just a sentence or two of his sage advice can keep me going.

Tozer (author of numerous Christian books, including the classics, The Knowledge of the Holy and The Pursuit of God). I have to say he is my favorite Christian writer. Whenever I am feeling spiritually dry, I can always find refreshment in one of his essays or books. Sometimes just a sentence or two of his sage advice can keep me going.