John Walters's Blog, page 10

August 3, 2024

Book Review: Outside Looking In: A Novel by T. C. Boyle

T. C. Boyle has a penchant for examining countercultural issues, especially those from the sixties and seventies. One of his previous novels, Drop City, concerns a commune of hippies that decides to relocate from California to Alaska; the transplanted freaks are ultimately unprepared for the stark realities of the harsh climate and struggle for survival. In Outside Looking In, Boyle focuses on the early 1960s and Timothy Leary’s initial experiments with psychedelic drugs and communal lifestyles.

After a prologue set in Switzerland in 1943, in which the scientist who initially discovered LSD’s radical properties gets unexpectedly blasted out of his mind, Boyle cuts to Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1962. The story is told in three parts through the viewpoints of Fitz and Joanie, a couple with a teenage son. Fitz is a Harvard graduate student in psychology who is studying under Leary. In the first part, through Fitz’s viewpoint, the couple begins to become part of Leary’s “inner circle” by attending weekend psychedelic parties. They initially take psilocybin and gradually move on to the much more potent but then-untested LSD. At the time, both these drugs were legal, and Leary had Harvard’s approval to pursue the project. In part two, told through Joanie’s point of view, Leary’s followers spend two summers in Zihuatanejo, Mexico, where Leary has booked an entire seaside hotel. In this idyllic setting, they continue to indulge in LSD, psilocybin, marijuana, alcohol, and other drugs, supposedly in the name of research. During the second summer, the authorities in Mexico deport them.

In the third part, told through Fitz’s point of view, Leary is gifted a 64-room mansion in Millbrook, New York, and he invites the entire inner circle and their families to move in. They continue their so-called experiments, which basically amount to staying stoned and drunk most of the time, sharing communal chores and activities, and concocting ever-wilder schemes to expand and unite their minds. One of these involves drawing the names of two random people from a hat; the selected couple spends a week together, freed from household duties and encouraged to partake of large amounts of LSD. When Fitz is paired with an eighteen-year-old teenage girl, he develops an obsessive infatuation with her, losing interest in his wife and son and everything else around.

The Millbrook section traces the deterioration of the group’s harmony, which is inevitable, really, considering that they are united around Leary’s charisma and overindulgence in hallucinogenic substances. The drugs eventually render them at least partially glazed and dysfunctional, and Leary proves to be an untrustworthy guru; by the end of the book he is planning to take off for a six-month-long honeymoon in India with one of the multitudinous beauties that he regularly sleeps with. This last section, to my mind, is a bit tedious; Boyle takes his time detailing the inescapable deterioration, and it is particularly onerous because Fitz is so enamored with his teenage heartthrob that he can think of little else. Joanie eventually gets fed up with the commune and Fitz’s shenanigans and leaves with their son, and Fitz hardly even notices or cares.

In conclusion, it’s an interesting novel, and absorbing in parts, and I would recommend it but with reservations. The last third, as I mentioned, really does stretch out too long, and the climax comes with a fizzle rather than a bang. It doesn’t touch on any of the legal problems that are ahead for Leary; it ends with the so-called inner circle helplessly enmeshed in an experiment gone awry, an experiment that has descended into a mishmash of dysfunctional relationships and drug-muddled minds.

July 27, 2024

Book Review: Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann

Let me preface this review by clarifying that I have not seen the award-nominated film of the same name by Martin Scorsese, so reading this book was my introduction to this horrific story. After oil is discovered on land belonging to the Osage Nation in Oklahoma, the Osage people become wealthy, but local businessmen William Hale, his relatives, and criminals he hires conspire to murder numerous Osage who have headrights to the oil deposits so that they can take over their riches. The murders are perpetrated by shooting, poisoning, and bombing; it is almost unbelievable to what evil depths the local authorities, who ostensibly are the guardians of the Osage, will do in their greed to acquire their vast wealth.

The book is told in three parts. The first focuses on an Osage woman named Mollie Burkhart. One by one her relatives are being killed, and investigations financed by Hale and others intentionally lead nowhere. The second part features Thomas White, a former Texas Ranger who is now an FBI agent. J. Edgar Hoover dispatches him to Oklahoma to solve the murders; he puts together a team and slowly unravels the intricate webs of deception that cover the involvement of Hale and his minions. The third part is a first-person account by the book’s author Grann describing his research journey to Oklahoma and his discoveries of documents that prove the Osage murder conspiracy was much more extensive than White discovered during his investigation.

This book’s significance goes far beyond a mere murder mystery. It uncovers the shame of white attitudes towards Native Americans in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, a shame that ascended to the highest levels of government. Because members of Congress considered the Osage to be childlike, incompetent, and incapable of handling their own affairs, they authorized the system of guardianship through which local whites managed Osage wealth. The whites used the system as an opportunity to plunder the riches they were supposed to be safeguarding; many of the guardians concocted elaborate schemes to rob their Osage clients of everything they owned, giving them poor advice, falsifying documents, and even resorting to murdering the people they were supposed to protect. Conspiracies ran so deep that they were nearly impossible to overcome; they included local lawyers, sheriffs, policemen, and businessmen. Only White, coming in from the outside as a federal agent, was able to meticulously expose the immense scandal – and Grann makes it clear that he had to do it despite the interference of his overseer J. Edgar Hoover, who was more concerned with his own personal image than with seeing to the welfare of the Osage.

It is a complex story, but Grann presents it with skill and acuity so that readers are never lost in the maze of plots and subplots. The amazing thing is that it is as wild and unpredictable and unlikely as a work of fiction, but it’s all true. It all really happened. It’s disheartening to know that such evil exists in the world, but we knew that already, didn’t we? The triumph is that Hale and his cronies did not succeed. Their plot was exposed and they were tried and sent to prison for life. The tragedy is that so many members of the Osage Nation died, and some of their killers were never caught. Sometimes when I am making a bit of extra cash online by taking surveys I come across a question like: “Are you proud of America’s history as a nation?” True stories like this cause me to take a long pause before answering.

* * *

After I finished writing this review and pondered the subject further, I realized I needed to add a postscript to touch on a couple of related topics.

Firstly, in reference to the demonic businessman Hale who relentlessly preyed upon the Osage, I thought of the similarities between him and modern television characters that are idolized such as Kevin Costner as the ranch owner in Yellowstone and basically all the nasty family members in Succession. These award-winning shows are so acclaimed that I tried watching the first season of each. In short, they disgusted me. On both shows there were no good guys whatsoever, only various shades of villains. And the families in each had acquired immense wealth by exploiting the poor. It made me think that the Osage murders were not a fluke in American society, but rather in fact the norm. All too often wealth is built by the rich on the backs of the poor, and the rich use their resources to consolidate their hold on power through generous donations (think bribes) to political patrons. It still happens. Where have all the heroes gone?

Secondly, I remembered my personal connection with Native Americans in Oklahoma. When I attended a renowned writing workshop in 1973, I met a full-blooded Kiowa named Russell Bates. I was just starting out as a writer, but Russ already had several credits, including sales to major science fiction magazines and anthologies and an internship as a screenwriter for Star Trek (the original series). (Russ would go on to co-write an episode for the Star Trek animated series that won an Emmy Award.) Anyway, Russ and I became friends and for a time roomed together in Los Angeles while we tried to write a teleplay. Shortly before I took off on my extensive world travels, Russ decided to return to Oklahoma, so Russ and I and another writing workshop grad named Paul Bond set out on a road trip to take him home. When we arrived at Russ’s parents’ house, they treated Paul and I royally, feeding us their specialty of fried bread and beans, which was oh my God so delicious. On one occasion Russ and his brother David and Paul and I went to a bar for a few pitchers of beer. When we were getting ready to leave, somehow I ended up first out into the parking lot, where a gang of white guys surrounded me, intending to punish me for hanging out with Indians. One of them punched me, splitting the skin open above my left eye, and then David exited the bar. When he saw what was happening, he let out a roar and advanced. He was a big guy and all the white rapscallions scattered and fled. Russ’s mom patched me up when we got home and that was that, but it was a stark reminder that our Kiowa friends sometimes still had to endure the prejudice of narrow-minded white assholes. Some people never seem to learn.

July 24, 2024

In Pursuit of Excellence

I have been doing power yoga for decades now, at least three times a week as part of my exercise regimen. Since I began when I was still living in Greece and my schedule and location did not permit me to go to a school or studio, I devised my routine by studying numerous books and culling out the best advice from each. I’ll never forget what one of the authors wrote about the proper mindset during exercise. He said that the ultimate goal is not perfection because you never become perfect. That’s why yoga is called a practice. There is no arrival point; your aim is continual improvement. That’s true of many things in life, of course, including writing. It is important to fully focus on what you are doing so that everything you do is your best possible effort at the time.

Recently I forgot this and attempted to juggle too many projects at once, including finalizing three books and also writing at least five hundred new words a day. The result was that my attention dissipated into several different directions, which slowed me down and made it difficult to properly concentrate on anything. For instance, I had all but completed my new collection of memoirs and essays, Thoughts from the Aerie, but it was roughly assembled; it needed some fine tuning. And I couldn’t do that while I was simultaneously attempting to do all these other things. I had to put the rest aside and focus on the book. As I was beginning to realize and implement this, I came across a book called Slow Productivity: The Lost Art of Accomplishment Without Burnout by Cal Newport, which reinforced my efforts to slow down and work on one project at a time, get it right, and then move on. Newport suggests three principles: do fewer things, work at a natural pace, and obsess over quality. This confirmed the direction I had been heading in sidelining some tasks so I could fine-tune Thoughts from the Aerie. I rearranged the content, took out a few pieces that didn’t quite fit, and revised it thoroughly.

Most of the memoirs and essays I include were composed after I moved into the fourth-floor apartment that I call my aerie. I not only have an excellent physical view from my balcony, but in my solitude I have a sweeping perspective of past, present and future. In the book’s first section, “Back Story,” I deal with the past: I trace the roots of my artistic destiny and my irresistible urge to travel the world; I analyze the intricate patterns of past relationships; and I recall one of the most profound periods of solitude I have ever experienced during my life’s journey, a walk alone into the Himalayan Mountains. In the second and third sections I share observations about writing, travel, literature, perseverance amidst adversity, optimism during a pandemic, and other topics. And finally, I express my hopes and dreams for the future.

It would not have been possible to finalize the book into its present form if I had not made the decision to set aside other projects and prioritize its completion. Going forward, I plan to continue to work slowly, focus intently on one thing at a time, and emphasize quality.

July 20, 2024

Book Review: Once Upon a Time in Hollywood: A Novel by Quentin Tarantino

I am normally not a fan of novelizations of films, but this one, after all, is written by Tarantino himself, so I figured it was worth a read. It turns out that the book is not really a novelization; that is, it does not strictly follow the plot of the movie. In fact, the mind-blowing violent climax of the movie is presented as a flash-forward of a couple of pages near the beginning of the book and is not mentioned again at the end. Instead, Tarantino uses the novel as an excuse to fill in back-stories for the book’s main characters, in particular Rick Dalton, played in the film by Leonardo DiCaprio; Cliff Booth, played by Brad Pitt; Sharon Tate, played by Margot Robbie; and Charles Manson, played by Damon Herriman. This provides Tarantino with an opportunity to expound on the Hollywood of the late 1960s and on films and filmmakers in general, and he takes full advantage of it. For example, in the novel he presents Cliff Booth as an aficionado of foreign films, and he uses this as an excuse to spend an entire chapter extolling on the talents of his favorite foreign actors and directors. He also delves much deeper than the film does into Manson’s dark past, his acquaintance with Dennis Wilson of the Beach boys and other major players in the Hollywood music scene, his unrequited desire to be a singer/songwriter, the gathering of his harem of vagabond hippie women, and the use of these women as sexual pawns to influence and control the aforementioned important people.

So don’t expect a carefully cadenced plot leading up to a resounding climax. What Tarantino presents, rather, is a disjointed info-dump of details that did not make it into the film. Let me emphasize, though, that they are fascinating details. As I mentioned above, I am not really interested in film novelizations. This, in fact, is something much better: a supplement that brings out nuances of the story and characters that Tarantino was unable to include in the finished film. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is already one of my favorite Tarantino films, and the added material presented in this book only increases my appreciation of it. I’ve already watched it several times, and I can’t wait to watch it again with the extra insights culled from this book in mind.

Tarantino is a very good writer, and the voice with which he presents the material here reminds me of his tone in his other recent book, Cinematic Speculations. He is casual and conversational but at the same time erudite and precise, and he draws on a lifetime of film study and appreciation that few others can match. What can I say more? If you are a fan of Tarantino’s films, you are sure to enjoy this book. I would appreciate it, in fact, if he would write similar treatments for some of his other films. Pulp Fiction, for instance, and Kill Bill and Inglourious Basterds and Django Unchained. That would make for some good reading.

* * *

I couldn’t help but re-watch the film after reading the book. As I did, the differences between the book and the film became even clearer. Tarantino’s main medium is film, of course, and in the length of a film (even a somewhat longer film of almost three hours like Once Upon a Time in Hollywood) every moment of screen time is vital for the dissemination of information or advancement of the plot. This movie is set mainly in 1969, and to fully appreciate it you have to be aware of all the cultural inferences that Tarantino throws in – seemingly casually, but in fact all contributing to the buildup to the climax. The film, unlike the book, is a piece of alternate history, but we don’t really understand this until the end. (By the way, if you haven’t yet seen the film, some of that which follows may constitute spoilers.) The murder of Sharon Tate and her friends at the mansion she shared with her husband Roman Polanski (who was away at the time of the killings) was a horrendous deed that among others (such as the murder of a member of the audience by Hell’s Angels during the Rolling Stones concert at Altamont) signaled the end of the seemingly innocent and peaceful hippie era of the 1960s. The aura of love and joy that the hippies disseminated was shattered by the gruesome killings. One reason that I loved Once Upon a Time in Hollywood so much when I first saw it was that it offered a fairy tale-like alternative to what happened in the real world. In Tarantino’s alternate universe, Sharon Tate and the others are not murdered; instead, Manson’s followers are killed as they attempt to attack a mansion next door. I liked this. After all, they were obviously the crazed transgressors. The alternate history ending was similar, in a sense, to what happens at the end of Tarantino’s film Inglourious Basterds, in which Hitler and his main minions are all burned alive in a movie theater owned by a Jewish woman whose entire family was slaughtered by the Nazis. The stories in these two films, from the beginning to the end, lead up to a fantasy ending in which history itself is changed.

Now: back to Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. I grew up in the sixties; by 1969 I was sixteen years old. I was old enough to be appalled by the Manson killings when I read about them in the newspapers, and, like the characters in the film, I used to listen to those old pop songs on the radio. Tarantino nails the ambiance of the era; he’s spot on. However, if you are not familiar with this background, the book offers details that will increase your enjoyment of the film, and it also provides enhanced descriptions and explanations for the characters, films, TV shows, and so on that Tarantino refers to in the film. In a sense this blatantly brings out what a good filmmaker has to subtly do to provide verisimilitude in a movie. To get you to properly suspend your disbelief as you watch a film, a scriptwriter has to be aware of the details that Tarantino provides in the novel – even if they are only implied in the finished film. One casualty due to the long explanations in the novel, though, is the fairy tale ending, the “once upon a time” in the title.

July 17, 2024

Check Out My Book Recommendations!

I was invited to promote my novel The Misadventures of Mama Kitchen and suggest some of my favorite related books on a new recommendation site. Follow this link to check out The Best Books Celebrating the Psychedelic Sixties!

July 13, 2024

Book Review: The God Equation: The Quest for a Theory of Everything by Michio Kaku

The God Equation is Michio Kaku’s term for the ultimate theory, “the holy grail of physics, a single formula from which, in principle, one could derive all other equations, starting from the Big Bang and moving to the end of the universe.” In this book, Kaku traces the history of the search for this equation, beginning with Isaac Newton’s discovery of the laws of motion and gravity, and moving onward through Einstein’s theory of relativity, Michael Faraday and James Maxwell’s explanation of electricity and magnetism, and the contributions of Schrodinger, Heisenberg, Planck, Hawking, and others to the development of quantum theory and string theory. Kaku’s own area of expertise is string theory, one of the latest iterations in the quest for the ultimate explanation.

According to Kaku, an essential aspect of the God equation is symmetry. “To a physicist, beauty is symmetry. Equations are beautiful because they have a symmetry – that is, if you rearrange or reshuffle the components, the equation remains the same.” Through the development of the theory of gravitation, the theory of relativity, quantum theory, and string theory, physicists have always sought symmetry in their answers to the mysteries of the universe. You don’t have to worry, though, if, like me, you have not studied much advanced mathematics or physics. There are very few equations presented in the body of the text, but if you are interested you can find a few in the notes. Kaku is intent upon providing a general overview of the research in this area for those who have not had much training in it. Even so, I have to confess that I did not understand everything in The God Equation. Kaku is summarizing a vast amount of research history in just a few hundred pages, and sometimes he lost me as he jumped from one topic to the next.

The value I derive from this book is in its clarification of the logical leaps from Newton to Einstein to quantum theory, string theory, and beyond. It is also fascinating as Kaku delves into brief explanations of black holes, wormholes, dark matter, time travel, the creation of the universe, and the blackness of the night sky. I had never considered this last topic before. As Kaku writes, “If we start with a universe that is infinite and uniform, then everywhere we look into space our gaze will eventually hit a star. But since there are an infinite number of stars, there must be an infinite amount of light entering our eyes from all directions. The night sky should be white, not black.” The answer was finally provided by Edgar Allen Poe, of all people, who besides writing mystery and horror stories was also an amateur astronomer. He posited that “the night sky is black because the universe has a finite age.” Kaku adds that “telescopes peering at the farthest stars will eventually reach the blackness of the Big Bang itself.”

The book ends in uncertainty. Unfortunately, the God equation has not yet been discovered and experimentally proved. In fact, as Kaku explains it, the closer physicists seem to get to the answer, the more they uncover amazing new truths that add to the complexity of the conundrum. Who knows? Maybe the universe (or the multiverse) is set up as a never-ending puzzle, an entertaining and amusing diversion that will fascinate physicists for millennia to come. For those of you who are interested in assessing the current level of progress, this book is highly recommended.

July 6, 2024

A Summer Treat for My Blog Followers

As a summer gift to readers, I have enrolled electronic editions of some of my books and stories in the Smashwords Summer Sale, which runs through the month of July. Complete books are half price, marked down from $3.99 to $1.99. Short stories and mini-collections of essays and memoirs are available to download for free. Take advantage of this sale to stock up on some great reading material.

If the discount price does not appear on my profile page, click on the link to the specific book you are interested in and you’ll see the deal.

Smashwords was the digital distributor I used when I first became involved in electronic publishing, and when I later switched to another distributor, I left numerous editions of my early works in the Smashwords catalog. You can find a complete listing at my author’s profile here.

Among the books available at a half-price discount are my memoirs World Without Pain: The Story of a Search, After the Rosy-Fingered Dawn: A Memoir of Greece, and America Redux: Impressions of the United States After Thirty-Five Years Abroad; the novels Love Children, The Misadventures of Mama Kitchen, and Sunflower; the collections The Dragon Ticket and Other Stories, Painsharing and Other Stories, Dark Mirrors: Dystopian Tales, and Opting Out and Other Departures; and the essay collection Reviews and Reflections on Books, Literature, and Writing.

The stories available for free include some of my personal favorites such as “Dark Mirrors,” “The Customs Shed,” “Life After Walden,” and “Noah and the Fireflood.”

So head on over to Smashwords and pick up some thrilling and thoughtful novels, short stories, memoirs, and essays at deep discounts and even free.

June 29, 2024

Thoughts from the Aerie: Memoirs and Essays Is Now Available!

My latest book, Thoughts from the Aerie: Memoirs and Essays, has just been published by Astaria Books and is available from numerous online outlets, including the venues listed below. Here’s a summary from the back cover:

After living abroad for thirty-five years in India, Bangladesh, Italy, Greece, and other countries, John Walters returned to his home country, the United States, with his sons. When the youngest moved out, he found himself alone in a fourth floor apartment with a spectacular view. He dubbed his new home the aerie.

For some people solitude can be devastating, but for others it can provide a unique opportunity to maximize the creative experience. These scintillating and captivating essays trace the roots of artistic destiny, follow the intricate patterns of past relationships, and offer fascinating observations about writing, travel, literature, perseverance amidst adversity, optimism during a pandemic, and other topics.

Most of the memoirs and essays I include were composed after I moved into the fourth-floor apartment that I call my aerie. I not only have an excellent physical view from my balcony, but in my solitude I have a sweeping perspective of past, present and future.

By the way, I have received my physical author’s copies of the book and they are beautiful. Many thanks to Two Pollard Design for the radiant cover.

June 22, 2024

Book Review: The Quickening: Creation and Community at the Ends of the Earth by Elizabeth Rush

Elizabeth Rush is the author of Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore, a study of the effects of global warming and rising sea levels on vulnerable places and communities. In The Quickening she continues her studies of the impact on the environment of a warming world. In 2019, she joined the first scientific expedition to ever visit the massive Thwaites Glacier in Antarctica. During a brief window when the area around the glacier was not completely ice-bound, the crew and scientists aboard the Nathaniel B. Palmer grappled with inclement weather, dodging icebergs and sometimes having to break through surface ice to reach their destination. Once there, Rush assisted the various teams, conducted interviews, and recorded her experiences. She clarifies that in the past the exploration of Antarctica was very much the realm of affluent white males; there was a distinct lack of women and minorities on early research teams. In the modern era, however, the situation is being somewhat rectified.

The emphasis on exploration, discovery, and scientific achievement with a view to mitigating disasters wrought by climate change is only one of the major threads in this intense, multifaceted book. Early on Rush makes it clear that she deeply desired to have a child, but she was concerned that her yearning for motherhood conflicted with the need to minimize humankind’s global carbon footprint with a view to saving the planet. However, it is not as simple as mathematical calculations. She writes that “having children can be an act of radical faith that life will continue, despite all that assails it.” And: “I can celebrate the idea that to have a child means having faith that the world will change, and more importantly, committing to being a part of the change yourself.” Her longing to be a mother suffuses the narrative and adds a personal dimension to it. Even if we succeed in making radical societal and personal adjustments to combat climate change, it will take time to turn things around. Our children and grandchildren and many generations to come will reap the rewards of our sacrifices, and for their sakes everything we can do to make a difference is worthwhile.

As the story of the voyage continues, Rush alternates accounts of the activities aboard ship amidst snow flurries and icebergs with an account of her life afterwards. She does indeed become pregnant, and as the child grows in her womb, she continues to study literature on personal and societal responsibility for Earth’s changing environment. She discovers, for instance, that it was a major oil company that spent hundreds of millions of dollars in advertising to popularize the concept of the personal carbon footprint. She writes: “The narrative that individuals are responsible for both the climate crisis and slowing its acceleration via different consumer choices was crafted and drilled into us by one of the highest-emitting companies in the world.” She expresses rage “for the time I lost feeling ashamed for wanting to become a mother” and the determination to make “central to one’s position in the world, the possibility of that world’s continuation.”

Late in Rush’s pregnancy COVID-19 forces the world into isolation. Now that things have somewhat opened up again, it’s easy to forget how tense things were back then when the hospitals were filling up with patients and hundreds of thousands and then millions were dying. I remember doing the weekly grocery shopping in the early hours of a weekday morning when fewer people were around, how the supermarket shelves emptied of certain needed items, how most people wore masks in enclosed areas, and how all communal activities were canceled. During the pandemic, Rush is hyper-cautious for the sake of the new life within her as she continues to write about the urgency of valuing our planet enough to safeguard it from disaster.

At the bottom of the copyright page of The Quickening is a statement from the publisher that it “is committed to ecological stewardship” and that the book is printed “on acid-free 100% postconsumer-waste paper.” This is a specific example of a step that environmentally-conscious companies can take to mitigate climate change. The message of this book, then, is both cautionary and hopeful. Yes, climate change is happening and the world is warming; however, instead of despairing we need to commit to doing what we can to make the planet a better place for future generations.

June 13, 2024

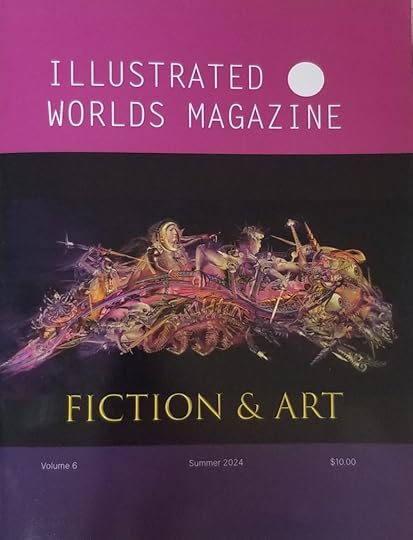

“The Hospice” Has Just Appeared in Illustrated Worlds Magazine

I am pleased to announce that my short story “The Hospice” has just been published in Illustrated Worlds Magazine: Volume 6, Summer 2024. It is a meticulously rendered slick magazine with innovative and attractive layout and interior artwork to illustrate each story.

In my story: A nurse in a hospice near a battlefield of the future refuses evacuation to remain behind and receive a drone bearing one last soldier, who turns out to be a severely wounded teenage girl. As the enemy approaches, nurse and patient enter a virtual world together, where they confront their individual traumas and seek healing.

Here’s the website description of the contents: Graced with mystical artwork by the incomparable Ruben Aldenhoven of the Netherlands on the cover, this issue contains illustrations by Nick Stevens, Phil Longmeier, Reggie Thomas, Kirsty Greenwood, Aidonas, Steve Bentley and J. Cox. There are stories of mechanical reptiles to enjoy, along with enduring love, deities fallen on hard times, the ravages of war and … well, bedbugs. Read imaginative tales told by master storytellers Stetson Ray, L. Chan, Christopher Bond, Johnathon Heart, Anthony Regolino, John Walters and more. It’s the perfect summer reading companion. You can order print or digital copies from the publisher’s website