Stan C. Smith's Blog, page 22

May 7, 2022

Awesome Animal Fact - Fast Falcons

Did you know there's a fish that can swim faster than a cheetah can run? Yep, it's the black marlin. Cheetahs have been clocked at up to 75 miles per hour (120 km/hr). However, a black marlin that was hooked by a fisherman was recorded stripping line off the fishing reel at 120 feet per second. That's 82 miles per hour (132 km/hr). I find this to be amazing because the fish is swimming through water, which creates much more resistance than air.

Hmmm... let's think about this, though. Actually, the marlin is swimming, which is kind of like flying through the water, right? Therefore, maybe we should compare the marlin's speed to the speed of something flying through the air instead of running. The fastest flying animal is the peregrine falcon, clocked at an astounding 242 miles per hour (389 km/hr). That's three times faster than the marlin can swim.

The peregrine is not only the fastest flyer, it is the fastest animal in the entire animal kingdom.

I should point out that the peregrine falcon does not fly this fast when it is moving horizontally. Instead, the falcon achieves this speed when in its high-speed hunting dive (called a hunting stoop). The bird flies to a great height, then it dives at its prey (another flying bird) at over 200 miles per hour. Interestingly, the falcon is careful to strike one wing of the bird, not the body, to keep from smashing itself to smithereens. This breaks the prey bird's wing, making it easy for the falcon to then finish it off.

Photo Credits:

Photo Credits:

- Peregrine falcon diving - DepositPhotos

Hmmm... let's think about this, though. Actually, the marlin is swimming, which is kind of like flying through the water, right? Therefore, maybe we should compare the marlin's speed to the speed of something flying through the air instead of running. The fastest flying animal is the peregrine falcon, clocked at an astounding 242 miles per hour (389 km/hr). That's three times faster than the marlin can swim.

The peregrine is not only the fastest flyer, it is the fastest animal in the entire animal kingdom.

I should point out that the peregrine falcon does not fly this fast when it is moving horizontally. Instead, the falcon achieves this speed when in its high-speed hunting dive (called a hunting stoop). The bird flies to a great height, then it dives at its prey (another flying bird) at over 200 miles per hour. Interestingly, the falcon is careful to strike one wing of the bird, not the body, to keep from smashing itself to smithereens. This breaks the prey bird's wing, making it easy for the falcon to then finish it off.

Photo Credits:

Photo Credits:- Peregrine falcon diving - DepositPhotos

Published on May 07, 2022 06:10

Awesome Animal Fact - Inefficient Pandas

Did you know giant pandas eat 25 to 90 pounds (12-38 kg) of bamboo every day? Bamboo is pretty much all pandas eat—bamboo leaves, shoots, and stems. Fourteen hours per day eating bamboo.

The question is, why do they eat so much of the stuff? Recent research has provided some answers. It turns out that pandas have microbes in their gut that are more similar to the microbes of carnivores and omnivores than to those of herbivores. Actually, they don't have any of the microbes needed to digest cellulose, which is the stuff in plant cell walls that make plants hard for humans to digest. So, pandas have to eat a lot of bamboo because they can only digest about 17% of the bamboo they eat.

Pandas evolved from omnivore ancestors, not from herbivores, and they began specializing in eating bamboo about seven million years ago. During those seven million years, they never developed a highly efficient way to break down cellulose. They simply do not have the genes necessary to produce plant-digesting enzymes.

For this reason, many scientists believe pandas are at an evolutionary dead end, and this may have increased their risk of extinction. Fortunately, conservation efforts are helping to preserve at least some of the panda's native bamboo forests. Photo Credits:

Photo Credits:

- Panda eating bamboo - DepositPhotos

The question is, why do they eat so much of the stuff? Recent research has provided some answers. It turns out that pandas have microbes in their gut that are more similar to the microbes of carnivores and omnivores than to those of herbivores. Actually, they don't have any of the microbes needed to digest cellulose, which is the stuff in plant cell walls that make plants hard for humans to digest. So, pandas have to eat a lot of bamboo because they can only digest about 17% of the bamboo they eat.

Pandas evolved from omnivore ancestors, not from herbivores, and they began specializing in eating bamboo about seven million years ago. During those seven million years, they never developed a highly efficient way to break down cellulose. They simply do not have the genes necessary to produce plant-digesting enzymes.

For this reason, many scientists believe pandas are at an evolutionary dead end, and this may have increased their risk of extinction. Fortunately, conservation efforts are helping to preserve at least some of the panda's native bamboo forests.

Photo Credits:

Photo Credits:- Panda eating bamboo - DepositPhotos

Published on May 07, 2022 06:06

April 22, 2022

Awesome Animal Fact - Productive Cows

Did you know cows poop 15 times per day? The average adult cow produces about 65 pounds (30 kg) of manure daily. That adds up to about 12 tons (11,000 kg) of poo each year. Per cow. I guess this shouldn't be surprising, considering cows stand around eating pretty much all day long. Fortunately, all that manure makes for excellent fertilizer.

Of course, this depends on the breed, sex, and size of the animal, but these numbers are reasonable averages.

Cows also produce copious amounts of urine. On average, a cow releases 3.5 gallons (13 L) of urine each day. It helps to wrap your head around this if you imagine filling up thirteen 1-liter soda bottles with urine.

And let's not forget about milk. An average dairy cow produces about 7.5 gallons (28 L) of milk per day. Interestingly, if a cow was only producing enough milk to feed a calf, it would need only one gallon per day. Due to selective breeding, the average yearly milk production for a single cow has increased from 233 gallons in 1880 to 2,825 gallons in 2022. Um, that's twelve times more milk per cow.

Photo Credit:

Photo Credit:

- Dairy cows - DepositPhotos

Of course, this depends on the breed, sex, and size of the animal, but these numbers are reasonable averages.

Cows also produce copious amounts of urine. On average, a cow releases 3.5 gallons (13 L) of urine each day. It helps to wrap your head around this if you imagine filling up thirteen 1-liter soda bottles with urine.

And let's not forget about milk. An average dairy cow produces about 7.5 gallons (28 L) of milk per day. Interestingly, if a cow was only producing enough milk to feed a calf, it would need only one gallon per day. Due to selective breeding, the average yearly milk production for a single cow has increased from 233 gallons in 1880 to 2,825 gallons in 2022. Um, that's twelve times more milk per cow.

Photo Credit:

Photo Credit:- Dairy cows - DepositPhotos

Published on April 22, 2022 11:49

April 18, 2022

Awesome Animal Fact - Sleepy Koalas

Did you know koalas sleep 18 to 22 hours every day? Seriously, that's more than a human teenager sleeps. I know, because I used to be one... a teenager, not a koala.

Why do koalas sleep so much? Because they are always working really hard. On the outside, it may not look like they're working hard (in fact, they seem kind of lazy), but they are definitely working hard on the inside.

Here's why. Koalas are fond of living in eucalyptus trees and eating eucalyptus leaves. In fact, that's pretty much all they ever eat. They eat more than a pound of eucalyptus leaves per day. The problem is, eucalyptus leaves are toxic, and they have a huge amount of fiber and very few calories and nutrients. So, a koala's body has to work really hard to break down the toxins and extract nutrients from the leaves. This, of course, can be done while they sleep. And because it takes so much energy to digest their food, they might as well be sleeping to keep from using up what little energy they are gaining from digestion.

Oh... one more thing. I mentioned above that koalas only eat eucalyptus leaves, but that's not completely true. When they are really young (and called joeys), they eat their mother's poop. This is after they stop feeding on milk and before they start eating leaves on their own. Technically, though, because the mother only eats eucalyptus leaves, I guess the mother's poop is eucalyptus leaves too.

Photo Credit:

- Sleeping koala - DepositPhotos

Why do koalas sleep so much? Because they are always working really hard. On the outside, it may not look like they're working hard (in fact, they seem kind of lazy), but they are definitely working hard on the inside.

Here's why. Koalas are fond of living in eucalyptus trees and eating eucalyptus leaves. In fact, that's pretty much all they ever eat. They eat more than a pound of eucalyptus leaves per day. The problem is, eucalyptus leaves are toxic, and they have a huge amount of fiber and very few calories and nutrients. So, a koala's body has to work really hard to break down the toxins and extract nutrients from the leaves. This, of course, can be done while they sleep. And because it takes so much energy to digest their food, they might as well be sleeping to keep from using up what little energy they are gaining from digestion.

Oh... one more thing. I mentioned above that koalas only eat eucalyptus leaves, but that's not completely true. When they are really young (and called joeys), they eat their mother's poop. This is after they stop feeding on milk and before they start eating leaves on their own. Technically, though, because the mother only eats eucalyptus leaves, I guess the mother's poop is eucalyptus leaves too.

Photo Credit:

- Sleeping koala - DepositPhotos

Published on April 18, 2022 10:02

March 24, 2022

Awesome Short Story - Letters and Words

I've been spending some time lately writing a series of speculative short stories (2,000 to 2,500 words or so). For each of these stories, I start with a "What if?" question.

For this story, I asked the question "What if you discovered someone or something was trying to communicate with you in a strange way?"

I hope you enjoy it!

Reuben didn’t like change. He liked what he’d always liked. That’s why he was eating breakfast alone at 5:30 AM, just as he had always done. It was also why he’d bought a dozen boxes of Alpha-Bits cereal when some company in China started making the stuff once it was discontinued in the US. And it tasted pretty much the same as it always had, which was fine with Reuben. Alpha-Bits drowned in 100% whole milk. From a cow. Not from almonds, or soybeans, or chickpeas, or whatever else they were trying to make milk from these days.

With his mug of black coffee steaming beside his bowl of Alpha-Bits, Reuben spread out his old-fashioned printed newspaper on the breakfast table, careful not to crinkle the pages too loudly and wake Marlene. Marlene liked to sleep in. Always had.

So far it was a perfect morning. Reuben had already had a decent bowel movement, nothing to complain about there. He’d found the newspaper on the porch instead of in the bushes. And today marked his ninth year of retirement. It’d been a damn good nine years, too. Nine years of comfortable routine. Reuben and Marlene, doing what they loved to do, day after day. Some things they did together, some things apart. Just the right balance.

Staring at the not-so-perfect headlines about inflation and a new COVID-19 variant, he spooned up his first bite of cereal. Before shoving it into his mouth, he glanced at the pile of random letters on his spoon. Only they weren’t random. Among the haphazard letters on their edges or upside-down were six letters arranged in order: REUBEN.

Reuben stared. What were the chances? He had occasionally gotten a two-letter word, and one time he laughed his head off when he got the word ASS. But nothing like this. Today was indeed going to be a perfect day.

Grinning like a kid at Christmas, he ate his name, imagining that it tasted better simply because of the statistical improbability of it. He spooned up another pile. In the spoon, six letters again spelled REUBEN.

Reuben’s grin faded. For a moment he thought maybe he hadn’t actually put the first spoonful in his mouth and was still staring at the same pieces, but his mouth was full—he had eaten his name. Somehow the letters had arranged themselves into his name a second time. This was not only unlikely, it couldn’t happen. It just couldn’t.

He considered calling to Marlene, waking her up to see what he’d done. But she’d think he was pulling her leg, then she’d be in a foul mood from getting woke up. He shoved the bite into his mouth, stirred the cereal around in his bowl a few times to mix it up, then scooped up a totally random spoonful.

Six letters spelled REUBEN.

A wave of tingles began washing over Reuben’s face, from his scalp down. Maybe he was hallucinating. He’d eaten a sampler plate of seafood chowders at Buck’s Crab House the previous evening. Maybe he’d gotten a bad batch. But his stomach felt perfectly fine.

He turned the spoon over, splattering the contents onto the table. Somehow, in the mess, six letters still spelled out his name. His tingles spread down his neck and out to his fingertips. Using his spoon, he scooped more cereal onto the table, not caring that the milk was getting his newspaper wet. Among the scattered pieces of sugary, multigrain cereal, his name appeared again: REUBEN. He did it again, and again it said REUBEN.

He stood up and swiped the newspaper off the table. It fluttered noisily onto the floor. He went to the cupboard and brought back the half-empty Alpha-Bits box. After flipping open the tabs and unrolling the plastic sleeve, he sprinkled some of the cereal across the tabletop, working the box back and forth to spread the letters out. Clutching the box to his chest, he stared down at the mess. For several long seconds, he didn’t see anything unusual. Then he did. He spotted the word IMPORTANT. Once he saw it, it was obvious. And there were more words. There was an entire sentence.

REUBEN THIS IS IMPORTANT

“Marlene!” His voice cracked, so he shouted again. “Marlene!”

He wanted Marlene to see what he’d done, so he left the cereal on the table exactly like it was. He sat in his chair and sprinkled the rest of the cereal from the box onto the floor. Seconds later he found another sentence in the mess.

REUBEN YOU MUST SAVE YOUR PEOPLE

“Marlene!”

“What is it, Reuben?”

“You gotta see this!”

“I’m trying to sleep. Can’t it wait?”

“Dammit, Marlene, you gotta see this!”

Reuben went to the cupboard again, plucked out a new box of Alpha-Bits, and tore it open. He sprinkled cereal onto the counter below the cupboard. Seconds later he saw it.

REUBEN SAVE YOUR PEOPLE FROM TERRENCE

“Terrence?” he said aloud. The only Terrence he knew was the neighbor from next door. Strange man who never did much neighboring. “Who are you?” he said, feeling stupid, like he was talking to a box of cereal.

Marlene’s voice came from beyond the bedroom door. “What did you say?”

“You need to get out here!” He moved to a new spot on the counter and dumped out more cereal. He saw the sentence.

REUBEN YOU MUST KILL TERRENCE NOW

He stared. This was insane. “Who are you?”

He dumped more cereal.

IMPORTANT

“What’s important?” He dumped more cereal.

KILL TERRENCE NOW TO SAVE YOUR PEOPLE

He poured out some more.

KILL HIM NOW REUBEN

The bedroom door opened. Marlene was in her robe. “For God’s sake, what are you doing?”

“I don’t know what I’m doing! You have to see this.” He showed her, starting with the words on the table, then the ones on the floor, then on the counter.

“You woke me up for this? Aren’t you a little mature for this kind of joke?”

He stared at her. “Someone is telling me to kill our neighbor!”

Her eyes grew wide as she studied his face. Now she looked as scared as he was. “Are you okay, Reuben?”

“No, I’m not okay!”

She turned and headed back to the bedroom. “I’m calling Clinton.”

“Good, you do that.”

Clinton was Marlene’s brother—a psychiatrist, and a good one too. Clinton had helped save Reuben and Marlene’s marriage years ago. Reuben liked the guy, even though he drove a hoity-toity Jaguar. Yes, Reuben needed to talk to Clinton. Right now.

Seconds later, he heard Marlene talking to her brother in a hushed tone.

Reuben decided he needed something better for these messages than breakfast cereal. He went to the closet and dug out the Scrabble game. He cleared the coffee table in the living room, opened the box, then dumped out the hundred letter tiles from the cloth bag. It took him only a few seconds to spot a message.

TERRENCE IS GOING TO KILL YOUR PEOPLE

He was surely going mad. “Why are you saying these things? Who are you?” He scooped up the tiles and dropped them onto the tabletop again.

KILL TERRENCE NOW

He scooped them up and dropped them again.

YOU ARE RUNNING OUT OF TIME

He did it again.

REUBEN YOU MUST KILL TERRENCE NOW

“Ahh!” Reuben shouted, and he flipped the coffee table over, scattering the tiles across the carpet. He sat on the couch, trying to steady his breathing. Was that a pain in his chest? Was he having a heart attack?

Marlene came into the room, stared for a moment, and said, “He’s on his way.” She turned the table upright and started picking up the mess. She had changed into a dress. Reuben was losing his marbles, maybe having a life-threatening heart attack, and she had taken the time to change her clothes. After putting the tiles back into their bag, she sat beside him. “Reuben, you’re trembling.” She put her arm around him, which he actually found to be comforting.

***

Clinton knocked on the door within minutes, and Marlene showed him in. Reuben was now lying on his back on the couch, with a warm washcloth over his eyes. He sat up, feeling slightly dizzy.

“I think it started as a joke,” Marlene said, after accepting a hug from her brother. “He was trying to be funny, but now I’m really worried about him.”

Reuben shook his head. “It didn’t start as a joke!”

Marlene gave her brother a look that said a lot without her needing to speak any words. It was infuriating, but at this point Reuben wanted Clinton to find that he was having some kind of episode—something there might be a pill for.

“Show Clinton what you think is happening,” said Marlene.

Reuben grabbed the bag of tiles and dumped them onto the coffee table. He held his breath, hoping there wouldn’t be a message. He needed to be proven wrong.

Then he saw it. He pointed to the first word then moved his finger over the entire sentence.

REUBEN MARLENE AND CLINTON YOU MUST KILL TERRENCE NOW

He turned to Clinton, who was frowning.

“How did you do that?” Clinton asked.

Instead of answering, Reuben scooped up the tiles and dropped them again. He found the words and pointed.

KILL TERRENCE OR HE WILL DESTROY YOUR WORLD

Marlene sucked in a breath, as if this was the first time she had actually seen the words. “What’s going on, Reuben? This isn’t funny. Not one bit.”

“How many times has this happened?” Clinton asked.

Reuben scooped the tiles up again. “It started at breakfast—with my Alpha-Bits, for God’s sake! And it happens every time. It keeps saying to kill Terrence. Our neighbor’s name is Terrence.” He dropped the tiles on the table then pointed.

YOU ARE RUNNING OUT OF TIME

“I’ve never seen anything like this,” Clinton said. “And to be honest, it’s rather frightening.” He pulled his phone from his pocket. “For lack of a better idea, I think the police should probably pay a visit to your neighbor.” He nodded at the phone in his hand. “Do you mind?”

“Please do,” said Marlene.

Reuben shrugged. This debacle was ruining his whole day. Now he wanted the whole thing to go away. Then maybe he’d be able to convince himself it had never happened.

***

Twenty minutes later, two Dubuque police officers were standing in the living room, staring at a new message on the coffee table.

KILL TERRENCE NOW IF YOU WANT TO SAVE YOUR PEOPLE

It was the sixth message in a row that they had seen, and Reuben was starting to wonder if they were ever going to believe what their own eyes were showing them.

The heavier man, last name Brewer, shook his head for the umpteenth time. “Let me try it.” He gathered the tiles and dropped them.

Marlene saw the message first and pointed it out.

SOON IT WILL BE TOO LATE

“Jesus Christ,” said the smaller one, last name Bramley. “What do you folks know about your neighbor Terrence?”

“Almost nothing,” said Marlene. “The man hardly speaks, even when we holler hello. Doesn’t even wave.”

The two officers eyed each other for a moment.

Officer Brewer said, “You folks stay inside until we get back, okay?”

They all nodded.

When the officers stepped out the front door, Reuben, Marlene, and Clinton gathered at the only window that had a view of Terrence’s front porch. The officers crossed the lawns, climbed the steps to the porch, and knocked. They knocked again, and Brewer shouted something.

Terrence opened the door, stepped out, and closed the door behind him. He stood facing the officers, with his back to the three observers. Brewer and Bramley were asking questions, but they didn’t seem very happy with the answers. Or maybe they weren’t getting any answers at all.

Reuben saw something strange, and he squinted. Terrence was standing with his hands clasped behind his back, but something was happening to his hands. They were changing shape, seemingly growing longer.

Abruptly, Terrence swung both his arms from behind his back and struck Brewer.

Marlene let out a scream.

Reuben stared in confusion. Officer Brewer’s head was gone. His body collapsed in a heap on the porch.

Officer Bramley shouted something and took several steps back as Terrence drew his arms back to thrust them out again.

A shot rang out, then another and another and another. Terrence toppled down the porch steps and onto the sidewalk.

Reuben ran for his front door and threw it open, ignoring Marlene’s pleas for him to stay inside. He ran across the yards and stopped at Terrence’s body. But it wasn’t a normal body. It still had Terrence’s face, but the impossibly long arms were shiny and orange, with wide, flat blades instead of hands, like two plastic, jointed canoe paddles.

As he stared down at Terrence, Reuben barely heard Officer Bramley shouting into his radio, calling for help.

Orange fluid—maybe blood—was flowing from Terrence’s gunshot wounds onto the sidewalk, forming tiny rivulets on its way toward the street. The rivulets started shifting, changing directions, some of them even flowing up the slope. Within seconds, they formed a string of letters.

REUBEN GO INSIDE AND TURN IT OFF NOW

BASEMENT

GREEN LEVER BLUE LEVER THEN WHITE LEVER

Reuben knew he needed to do this. He had no idea why, he just knew it. He leapt up the stairs, past Officer Bramley and his dead partner, and into the house. He found the door to the basement, descended the carpet-covered stairs, and stopped, staring at an object unlike anything he had ever seen before. It filled most of the basement, from floor to ceiling. It was mostly black, with irregular streaks of orange running parallel to each other, like reverse tiger stripes.

He felt something, a silent vibration that jiggled his internal organs. It was getting more pronounced with every passing second, growing, intensifying, strengthening.

Something caught his eye, on the concrete floor. Sawdust and dirt. The particles were moving, pulling together, forming letters, words, even punctuation.

NOW REUBEN

GREEN LEVER BLUE LEVER THEN WHITE LEVER

NOW NOW NOW

He turned back to the massive black and orange object. To his right, at chest level, was a control panel with dozens of buttons, switches, and levers, each a different color. He found the green lever, in the up position, and he shoved it down. Then he found the blue lever and shoved it down, then the white lever.

His organs stopped jiggling.

He turned back to the sawdust and dirt on the floor. “What did I just do?”

The particles moved into formation.

YOU SAVED YOUR PEOPLE

“Why couldn’t you do it yourself? I mean, if you can move dirt and Scrabble tiles and Alpha-Bits?”

MY INFLUENCE IS LIMITED DUE TO MY GREAT DISTANCE FROM YOUR WORLD

Reuben tried to swallow, but his mouth was too dry. “Who are you?”

I AM AN OBSERVER

YOUR WORLD INTERESTS ME

“Are you like Terrence?”

IN MY BODY TYPE ONLY

NOT IN MY INTENTIONS

“Did I save the world?”

YOU MUST LEAVE THIS HOUSE NOW

OTHERS LIKE ME WILL ARRIVE SOON TO DESTROY THE WEAPON

“Why couldn’t they turn off the weapon?”

THEY WERE TOO FAR AWAY WHEN THE WEAPON ACTIVATION WAS DETECTED

IT IS FORTUNATE YOU WERE NEAR

YOU MUST GO HOME NOW

“Will you continue talking to me? You know, with the cereal or whatever?”

LET US HOPE IT IS NOT NECESSARY

GOODBYE REUBEN

For this story, I asked the question "What if you discovered someone or something was trying to communicate with you in a strange way?"

I hope you enjoy it!

Reuben didn’t like change. He liked what he’d always liked. That’s why he was eating breakfast alone at 5:30 AM, just as he had always done. It was also why he’d bought a dozen boxes of Alpha-Bits cereal when some company in China started making the stuff once it was discontinued in the US. And it tasted pretty much the same as it always had, which was fine with Reuben. Alpha-Bits drowned in 100% whole milk. From a cow. Not from almonds, or soybeans, or chickpeas, or whatever else they were trying to make milk from these days.

With his mug of black coffee steaming beside his bowl of Alpha-Bits, Reuben spread out his old-fashioned printed newspaper on the breakfast table, careful not to crinkle the pages too loudly and wake Marlene. Marlene liked to sleep in. Always had.

So far it was a perfect morning. Reuben had already had a decent bowel movement, nothing to complain about there. He’d found the newspaper on the porch instead of in the bushes. And today marked his ninth year of retirement. It’d been a damn good nine years, too. Nine years of comfortable routine. Reuben and Marlene, doing what they loved to do, day after day. Some things they did together, some things apart. Just the right balance.

Staring at the not-so-perfect headlines about inflation and a new COVID-19 variant, he spooned up his first bite of cereal. Before shoving it into his mouth, he glanced at the pile of random letters on his spoon. Only they weren’t random. Among the haphazard letters on their edges or upside-down were six letters arranged in order: REUBEN.

Reuben stared. What were the chances? He had occasionally gotten a two-letter word, and one time he laughed his head off when he got the word ASS. But nothing like this. Today was indeed going to be a perfect day.

Grinning like a kid at Christmas, he ate his name, imagining that it tasted better simply because of the statistical improbability of it. He spooned up another pile. In the spoon, six letters again spelled REUBEN.

Reuben’s grin faded. For a moment he thought maybe he hadn’t actually put the first spoonful in his mouth and was still staring at the same pieces, but his mouth was full—he had eaten his name. Somehow the letters had arranged themselves into his name a second time. This was not only unlikely, it couldn’t happen. It just couldn’t.

He considered calling to Marlene, waking her up to see what he’d done. But she’d think he was pulling her leg, then she’d be in a foul mood from getting woke up. He shoved the bite into his mouth, stirred the cereal around in his bowl a few times to mix it up, then scooped up a totally random spoonful.

Six letters spelled REUBEN.

A wave of tingles began washing over Reuben’s face, from his scalp down. Maybe he was hallucinating. He’d eaten a sampler plate of seafood chowders at Buck’s Crab House the previous evening. Maybe he’d gotten a bad batch. But his stomach felt perfectly fine.

He turned the spoon over, splattering the contents onto the table. Somehow, in the mess, six letters still spelled out his name. His tingles spread down his neck and out to his fingertips. Using his spoon, he scooped more cereal onto the table, not caring that the milk was getting his newspaper wet. Among the scattered pieces of sugary, multigrain cereal, his name appeared again: REUBEN. He did it again, and again it said REUBEN.

He stood up and swiped the newspaper off the table. It fluttered noisily onto the floor. He went to the cupboard and brought back the half-empty Alpha-Bits box. After flipping open the tabs and unrolling the plastic sleeve, he sprinkled some of the cereal across the tabletop, working the box back and forth to spread the letters out. Clutching the box to his chest, he stared down at the mess. For several long seconds, he didn’t see anything unusual. Then he did. He spotted the word IMPORTANT. Once he saw it, it was obvious. And there were more words. There was an entire sentence.

REUBEN THIS IS IMPORTANT

“Marlene!” His voice cracked, so he shouted again. “Marlene!”

He wanted Marlene to see what he’d done, so he left the cereal on the table exactly like it was. He sat in his chair and sprinkled the rest of the cereal from the box onto the floor. Seconds later he found another sentence in the mess.

REUBEN YOU MUST SAVE YOUR PEOPLE

“Marlene!”

“What is it, Reuben?”

“You gotta see this!”

“I’m trying to sleep. Can’t it wait?”

“Dammit, Marlene, you gotta see this!”

Reuben went to the cupboard again, plucked out a new box of Alpha-Bits, and tore it open. He sprinkled cereal onto the counter below the cupboard. Seconds later he saw it.

REUBEN SAVE YOUR PEOPLE FROM TERRENCE

“Terrence?” he said aloud. The only Terrence he knew was the neighbor from next door. Strange man who never did much neighboring. “Who are you?” he said, feeling stupid, like he was talking to a box of cereal.

Marlene’s voice came from beyond the bedroom door. “What did you say?”

“You need to get out here!” He moved to a new spot on the counter and dumped out more cereal. He saw the sentence.

REUBEN YOU MUST KILL TERRENCE NOW

He stared. This was insane. “Who are you?”

He dumped more cereal.

IMPORTANT

“What’s important?” He dumped more cereal.

KILL TERRENCE NOW TO SAVE YOUR PEOPLE

He poured out some more.

KILL HIM NOW REUBEN

The bedroom door opened. Marlene was in her robe. “For God’s sake, what are you doing?”

“I don’t know what I’m doing! You have to see this.” He showed her, starting with the words on the table, then the ones on the floor, then on the counter.

“You woke me up for this? Aren’t you a little mature for this kind of joke?”

He stared at her. “Someone is telling me to kill our neighbor!”

Her eyes grew wide as she studied his face. Now she looked as scared as he was. “Are you okay, Reuben?”

“No, I’m not okay!”

She turned and headed back to the bedroom. “I’m calling Clinton.”

“Good, you do that.”

Clinton was Marlene’s brother—a psychiatrist, and a good one too. Clinton had helped save Reuben and Marlene’s marriage years ago. Reuben liked the guy, even though he drove a hoity-toity Jaguar. Yes, Reuben needed to talk to Clinton. Right now.

Seconds later, he heard Marlene talking to her brother in a hushed tone.

Reuben decided he needed something better for these messages than breakfast cereal. He went to the closet and dug out the Scrabble game. He cleared the coffee table in the living room, opened the box, then dumped out the hundred letter tiles from the cloth bag. It took him only a few seconds to spot a message.

TERRENCE IS GOING TO KILL YOUR PEOPLE

He was surely going mad. “Why are you saying these things? Who are you?” He scooped up the tiles and dropped them onto the tabletop again.

KILL TERRENCE NOW

He scooped them up and dropped them again.

YOU ARE RUNNING OUT OF TIME

He did it again.

REUBEN YOU MUST KILL TERRENCE NOW

“Ahh!” Reuben shouted, and he flipped the coffee table over, scattering the tiles across the carpet. He sat on the couch, trying to steady his breathing. Was that a pain in his chest? Was he having a heart attack?

Marlene came into the room, stared for a moment, and said, “He’s on his way.” She turned the table upright and started picking up the mess. She had changed into a dress. Reuben was losing his marbles, maybe having a life-threatening heart attack, and she had taken the time to change her clothes. After putting the tiles back into their bag, she sat beside him. “Reuben, you’re trembling.” She put her arm around him, which he actually found to be comforting.

***

Clinton knocked on the door within minutes, and Marlene showed him in. Reuben was now lying on his back on the couch, with a warm washcloth over his eyes. He sat up, feeling slightly dizzy.

“I think it started as a joke,” Marlene said, after accepting a hug from her brother. “He was trying to be funny, but now I’m really worried about him.”

Reuben shook his head. “It didn’t start as a joke!”

Marlene gave her brother a look that said a lot without her needing to speak any words. It was infuriating, but at this point Reuben wanted Clinton to find that he was having some kind of episode—something there might be a pill for.

“Show Clinton what you think is happening,” said Marlene.

Reuben grabbed the bag of tiles and dumped them onto the coffee table. He held his breath, hoping there wouldn’t be a message. He needed to be proven wrong.

Then he saw it. He pointed to the first word then moved his finger over the entire sentence.

REUBEN MARLENE AND CLINTON YOU MUST KILL TERRENCE NOW

He turned to Clinton, who was frowning.

“How did you do that?” Clinton asked.

Instead of answering, Reuben scooped up the tiles and dropped them again. He found the words and pointed.

KILL TERRENCE OR HE WILL DESTROY YOUR WORLD

Marlene sucked in a breath, as if this was the first time she had actually seen the words. “What’s going on, Reuben? This isn’t funny. Not one bit.”

“How many times has this happened?” Clinton asked.

Reuben scooped the tiles up again. “It started at breakfast—with my Alpha-Bits, for God’s sake! And it happens every time. It keeps saying to kill Terrence. Our neighbor’s name is Terrence.” He dropped the tiles on the table then pointed.

YOU ARE RUNNING OUT OF TIME

“I’ve never seen anything like this,” Clinton said. “And to be honest, it’s rather frightening.” He pulled his phone from his pocket. “For lack of a better idea, I think the police should probably pay a visit to your neighbor.” He nodded at the phone in his hand. “Do you mind?”

“Please do,” said Marlene.

Reuben shrugged. This debacle was ruining his whole day. Now he wanted the whole thing to go away. Then maybe he’d be able to convince himself it had never happened.

***

Twenty minutes later, two Dubuque police officers were standing in the living room, staring at a new message on the coffee table.

KILL TERRENCE NOW IF YOU WANT TO SAVE YOUR PEOPLE

It was the sixth message in a row that they had seen, and Reuben was starting to wonder if they were ever going to believe what their own eyes were showing them.

The heavier man, last name Brewer, shook his head for the umpteenth time. “Let me try it.” He gathered the tiles and dropped them.

Marlene saw the message first and pointed it out.

SOON IT WILL BE TOO LATE

“Jesus Christ,” said the smaller one, last name Bramley. “What do you folks know about your neighbor Terrence?”

“Almost nothing,” said Marlene. “The man hardly speaks, even when we holler hello. Doesn’t even wave.”

The two officers eyed each other for a moment.

Officer Brewer said, “You folks stay inside until we get back, okay?”

They all nodded.

When the officers stepped out the front door, Reuben, Marlene, and Clinton gathered at the only window that had a view of Terrence’s front porch. The officers crossed the lawns, climbed the steps to the porch, and knocked. They knocked again, and Brewer shouted something.

Terrence opened the door, stepped out, and closed the door behind him. He stood facing the officers, with his back to the three observers. Brewer and Bramley were asking questions, but they didn’t seem very happy with the answers. Or maybe they weren’t getting any answers at all.

Reuben saw something strange, and he squinted. Terrence was standing with his hands clasped behind his back, but something was happening to his hands. They were changing shape, seemingly growing longer.

Abruptly, Terrence swung both his arms from behind his back and struck Brewer.

Marlene let out a scream.

Reuben stared in confusion. Officer Brewer’s head was gone. His body collapsed in a heap on the porch.

Officer Bramley shouted something and took several steps back as Terrence drew his arms back to thrust them out again.

A shot rang out, then another and another and another. Terrence toppled down the porch steps and onto the sidewalk.

Reuben ran for his front door and threw it open, ignoring Marlene’s pleas for him to stay inside. He ran across the yards and stopped at Terrence’s body. But it wasn’t a normal body. It still had Terrence’s face, but the impossibly long arms were shiny and orange, with wide, flat blades instead of hands, like two plastic, jointed canoe paddles.

As he stared down at Terrence, Reuben barely heard Officer Bramley shouting into his radio, calling for help.

Orange fluid—maybe blood—was flowing from Terrence’s gunshot wounds onto the sidewalk, forming tiny rivulets on its way toward the street. The rivulets started shifting, changing directions, some of them even flowing up the slope. Within seconds, they formed a string of letters.

REUBEN GO INSIDE AND TURN IT OFF NOW

BASEMENT

GREEN LEVER BLUE LEVER THEN WHITE LEVER

Reuben knew he needed to do this. He had no idea why, he just knew it. He leapt up the stairs, past Officer Bramley and his dead partner, and into the house. He found the door to the basement, descended the carpet-covered stairs, and stopped, staring at an object unlike anything he had ever seen before. It filled most of the basement, from floor to ceiling. It was mostly black, with irregular streaks of orange running parallel to each other, like reverse tiger stripes.

He felt something, a silent vibration that jiggled his internal organs. It was getting more pronounced with every passing second, growing, intensifying, strengthening.

Something caught his eye, on the concrete floor. Sawdust and dirt. The particles were moving, pulling together, forming letters, words, even punctuation.

NOW REUBEN

GREEN LEVER BLUE LEVER THEN WHITE LEVER

NOW NOW NOW

He turned back to the massive black and orange object. To his right, at chest level, was a control panel with dozens of buttons, switches, and levers, each a different color. He found the green lever, in the up position, and he shoved it down. Then he found the blue lever and shoved it down, then the white lever.

His organs stopped jiggling.

He turned back to the sawdust and dirt on the floor. “What did I just do?”

The particles moved into formation.

YOU SAVED YOUR PEOPLE

“Why couldn’t you do it yourself? I mean, if you can move dirt and Scrabble tiles and Alpha-Bits?”

MY INFLUENCE IS LIMITED DUE TO MY GREAT DISTANCE FROM YOUR WORLD

Reuben tried to swallow, but his mouth was too dry. “Who are you?”

I AM AN OBSERVER

YOUR WORLD INTERESTS ME

“Are you like Terrence?”

IN MY BODY TYPE ONLY

NOT IN MY INTENTIONS

“Did I save the world?”

YOU MUST LEAVE THIS HOUSE NOW

OTHERS LIKE ME WILL ARRIVE SOON TO DESTROY THE WEAPON

“Why couldn’t they turn off the weapon?”

THEY WERE TOO FAR AWAY WHEN THE WEAPON ACTIVATION WAS DETECTED

IT IS FORTUNATE YOU WERE NEAR

YOU MUST GO HOME NOW

“Will you continue talking to me? You know, with the cereal or whatever?”

LET US HOPE IT IS NOT NECESSARY

GOODBYE REUBEN

Published on March 24, 2022 18:08

February 2, 2022

Awesome Animal - Axolotl

When I was a kid, there was a city park about a block away that had a small lake. Around the edges of this lake were burrows that went back into the ground from the water's edge. In my endless curiosity (and perhaps foolishess) I discovered that, if I would lie down on my belly with my head over the water, I could reach my hand far back into these burrows. I know... kind of creepy, right? Well, even creepier, when I reached my hand back in there, I felt some fat, slimy creatures wriggling around, trying to escape my grasp. When I pulled one out, I realized it was a big, black and yellow tiger salamander. That's when my fascination with salamanders began.

This is the type of critter (tiger salamander) I pulled out of those holes in the lake's bank:

Then, in college, when I was working on a degree in wildlife biology, I learned that some tiger salamanders never grow out of the larval stage (the aquatic stage where they have external gills on the sides of their heads). If tiger salamanders happen to live in a pond with few or no predators, and if the pond has plenty of oxygen in the water and does not freeze all the way to the bottom, the salamander larvae are like Peter Pan—they never grow up. They remain in the larval form, even though they grow quite large. These larval tiger salamanders are sometimes called water dogs or mud puppies (although there is actually another type of salamander called the mudpuppy).

However, these water dogs can transform into adults (by losing their gills and developing lungs) at any time. For example, if the pond starts to dry up. Years ago, when I was a science teacher, I put two water dogs in an aquarium full of oxygenated water, and two in an aquarium with only an inch of water. The water dogs in the shallow aquarium transformed into air-breathing adults, whereas those in the full aquarium remained as larvae with gills. Fascinating, huh?

Well, there also happens to be a strange type of salamander that NEVER transforms into the adult form. It NEVER loses its gills. It is the true Peter Pan of the salamander world, and it's called the Axolotl .

What the heck is an Axolotl?

The Axolotl, pronounced ax-oh-lot-ul, is actually closely related to the tiger salamander. However, the axolotl only lives in a small area of Mexico, and it is almost extinct in the wild.

The native habitat of axolotls is only two lakes in the southern part of Mexico City. One of the lakes is now gone, and the other has mostly been converted into canals.

Axolotls are predators, feeding on aquatic insects, snails, worms, small fish, and other small aquatic creatures.

Here's an unusual twist. Despite being all but extinct in the wild, millions of axolotls exist around the world. Why? Because these creatures are used extensively in research and are therefore widely bred in research labs. They are also bred for the pet industry.

Amazing Facts about Axolotls

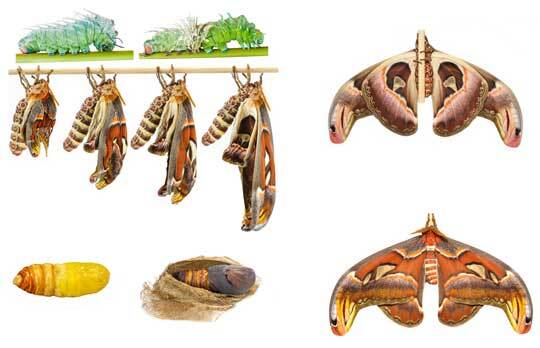

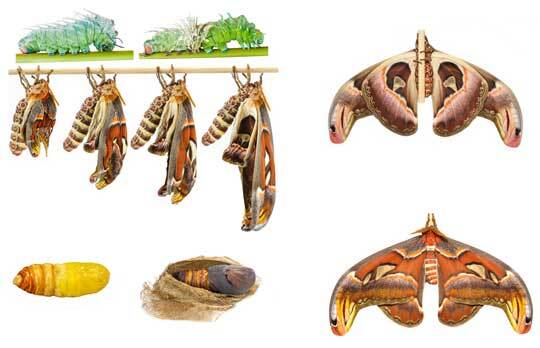

Okay, let's take a closer look at this Peter Pan concept. It's not really like axolotls never grow up. They do grow to sexual maturity, and they do reproduce. However, they always remain in their larval form, even when they grow to be 12 inches (30 cm) or longer. This is a specialized condition called paedomorphism (sometimes called neoteny)—retaining juvenile physical traits throughout adulthood.

Personally, there's been a few times I've been accused of retaining the mind of a child (which I consider a compliment), but that's a psychological trait, not a physical trait... not the same thing as neoteny!

As you probably know, most amphibians, like frogs and toads, start out as aquatic, tadpole-like larvae. Eventually, though, they metamorphose into terrestrial adults, breathing air instead of water. Most salamanders do this too, although, unlike tadpoles, salamander larvae usually have legs, and they do not lose their tail as they become adults.

So, why do axolotls display permanent paedomorphism? One reason is that axolotls do not have a certain hormone that is necessary for the thyroid gland to trigger metamorphosis.

Oddly, scientists have found that they can force axolotls to go through metamorphosis by artificially administering the hormone. But these salamanders cannot produce the hormone themselves, so this does not happen naturally in the wild. By the way, people who have axolotls as pets should not try this, as it usually kills the creature, either during the process or afterwards.

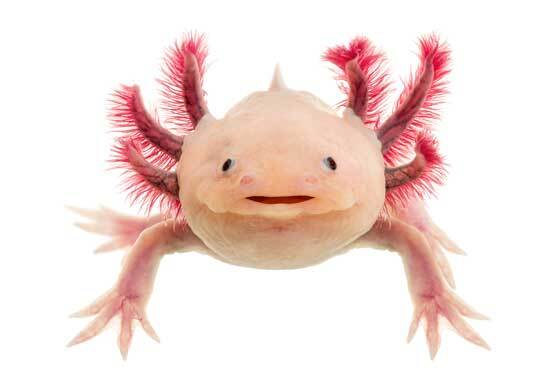

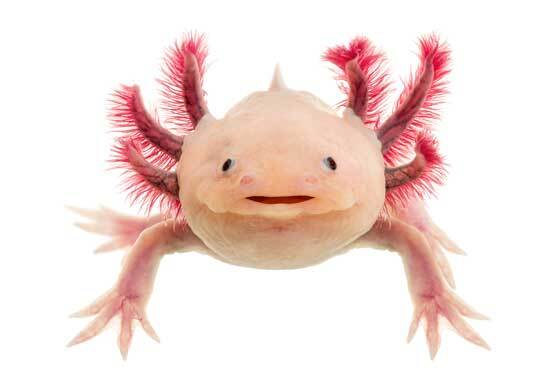

Take a look at the white axolotl below (as well as the white one above the previous photo).

White individuals like this are not found in the wild. Back in 1864, several axolotls were captured in Mexico and taken to Paris. There, people began breeding them in captivity, eventually developing several different color strains, including the white ones.

Because axolotls are easy to keep and breed in captivity, they have become popular pets, which are sometimes called "Mexican walking fish" in pet stores. Of course, they aren't really fish.

Also, as I stated above, they are widely bred for biological research. The reasons why are quite fascinating. First of all, axolotls have an amazing ability to regenerate body parts. You may know that some other amphibians can regenerate lost body tissue, but the axolotl is by far the champion at this. If they lose a limb, it grows right back. But that's not all. They can also regenerate their jaw, their spine, and even a portion of their brain. To give you an idea of how amazing the ability is, here's a quote from Professor Stephane Roy of the University of Montreal:

"You can cut the spinal cord, crush it, remove a segment, and it will regenerate. You can cut the limbs at any level—the wrist, the elbow, the upper arm—and it will regenerate, and it’s perfect. There is nothing missing, there’s no scarring on the skin at the site of amputation, every tissue is replaced. They can regenerate the same limb 50, 60, 100 times. And every time: perfect."

As you can probably guess, by studying regeneration in axolotls, scientists hope to figure out how to give humans this ability. Well, that seems like a stretch, but even if they don't figure out how to give humans the ability, understanding the process will likely result in other medical breakthroughs.

As if that weren't intriguing enough to scientists, axolotls are also 1,000 times more resistant to cancer than humans and other mammals. And, they can accept transplanted organs from other axolotls without ever rejecting the organs.

No wonder these critters are so common in research labs!

By the way, here's what the original wild axolotls looked like:

Unfortunately, they're pretty much gone in the wild. Remember, one of the lakes they lived in is now gone, and the other has been converted to canals. And this is in Mexico City, one of the largest cities in the world, where water pollution is a concern. In 1998, a survey was done in the canals that used to be the lake axolotls lived in, and scientists found a density of 6,000 axolotls per square km. A similar survey in 2003 found 1,000 per square km, and in 2008 they found only 100 per square km. In 2013, a four-month search found exactly zero axolotls.

Surprisingly, soon after that search, two axolotls were spotted in one of the canals. So, it is possible that a few wild ones are still alive in the canals.

I suppose it's a good thing axolotls thrive in captivity. In fact, there may be a greater number of them in captivity around the world than the number that ever lived in the two lakes of their original native range.

Finally, axolotls have long been culturally important in Mexico. According to legend, the axolotl is actually the Aztec god of fire and lightning, named Xolotl, who disguised himself as a salamander to avoid being sacrificed. Why? Because the Aztec gods were supposed to sacrifice themselves to the sun, to keep it alive and moving across the sky.

In Mexico City, axolotls are depicted on billboards, the sides of buildings, and even on the sides of tour buses.

In 2020, Mexico decided to use an image of an axolotl on its new 50-peso bill.

So, the Axolotl deserves a place in the W.A.H.O.F.

(Wizard Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word wizard, as you can imagine, is quite old. It originated in the early 1400s, and then it meant "philosopher or sage." It came from the Middle English wys, which meant "wise." It wasn't until about 1550 that the word was used to mean someone "with magical power." This happened because the distinction between philosophy and magic became blurred during the middle ages. Much, much later, in 1922, people (particularly British people) began using wizard as an adjective to mean "superb, outstanding."

So, wizard is another way to say awesome (at least in the UK)!

Photo Credits:

- Tiger salamander - DepositPhotos

- Axolotl #1, facing left, brown background - DepositPhotos

- Axolotl #2, closeup of brown, speckled face - DepositPhotos

- Axolotl #3, white, facing camera - DepositPhotos

- Axolotl #4 - wild brown color - DepositPhotos

This is the type of critter (tiger salamander) I pulled out of those holes in the lake's bank:

Then, in college, when I was working on a degree in wildlife biology, I learned that some tiger salamanders never grow out of the larval stage (the aquatic stage where they have external gills on the sides of their heads). If tiger salamanders happen to live in a pond with few or no predators, and if the pond has plenty of oxygen in the water and does not freeze all the way to the bottom, the salamander larvae are like Peter Pan—they never grow up. They remain in the larval form, even though they grow quite large. These larval tiger salamanders are sometimes called water dogs or mud puppies (although there is actually another type of salamander called the mudpuppy).

However, these water dogs can transform into adults (by losing their gills and developing lungs) at any time. For example, if the pond starts to dry up. Years ago, when I was a science teacher, I put two water dogs in an aquarium full of oxygenated water, and two in an aquarium with only an inch of water. The water dogs in the shallow aquarium transformed into air-breathing adults, whereas those in the full aquarium remained as larvae with gills. Fascinating, huh?

Well, there also happens to be a strange type of salamander that NEVER transforms into the adult form. It NEVER loses its gills. It is the true Peter Pan of the salamander world, and it's called the Axolotl .

What the heck is an Axolotl?

The Axolotl, pronounced ax-oh-lot-ul, is actually closely related to the tiger salamander. However, the axolotl only lives in a small area of Mexico, and it is almost extinct in the wild.

The native habitat of axolotls is only two lakes in the southern part of Mexico City. One of the lakes is now gone, and the other has mostly been converted into canals.

Axolotls are predators, feeding on aquatic insects, snails, worms, small fish, and other small aquatic creatures.

Here's an unusual twist. Despite being all but extinct in the wild, millions of axolotls exist around the world. Why? Because these creatures are used extensively in research and are therefore widely bred in research labs. They are also bred for the pet industry.

Amazing Facts about Axolotls

Okay, let's take a closer look at this Peter Pan concept. It's not really like axolotls never grow up. They do grow to sexual maturity, and they do reproduce. However, they always remain in their larval form, even when they grow to be 12 inches (30 cm) or longer. This is a specialized condition called paedomorphism (sometimes called neoteny)—retaining juvenile physical traits throughout adulthood.

Personally, there's been a few times I've been accused of retaining the mind of a child (which I consider a compliment), but that's a psychological trait, not a physical trait... not the same thing as neoteny!

As you probably know, most amphibians, like frogs and toads, start out as aquatic, tadpole-like larvae. Eventually, though, they metamorphose into terrestrial adults, breathing air instead of water. Most salamanders do this too, although, unlike tadpoles, salamander larvae usually have legs, and they do not lose their tail as they become adults.

So, why do axolotls display permanent paedomorphism? One reason is that axolotls do not have a certain hormone that is necessary for the thyroid gland to trigger metamorphosis.

Oddly, scientists have found that they can force axolotls to go through metamorphosis by artificially administering the hormone. But these salamanders cannot produce the hormone themselves, so this does not happen naturally in the wild. By the way, people who have axolotls as pets should not try this, as it usually kills the creature, either during the process or afterwards.

Take a look at the white axolotl below (as well as the white one above the previous photo).

White individuals like this are not found in the wild. Back in 1864, several axolotls were captured in Mexico and taken to Paris. There, people began breeding them in captivity, eventually developing several different color strains, including the white ones.

Because axolotls are easy to keep and breed in captivity, they have become popular pets, which are sometimes called "Mexican walking fish" in pet stores. Of course, they aren't really fish.

Also, as I stated above, they are widely bred for biological research. The reasons why are quite fascinating. First of all, axolotls have an amazing ability to regenerate body parts. You may know that some other amphibians can regenerate lost body tissue, but the axolotl is by far the champion at this. If they lose a limb, it grows right back. But that's not all. They can also regenerate their jaw, their spine, and even a portion of their brain. To give you an idea of how amazing the ability is, here's a quote from Professor Stephane Roy of the University of Montreal:

"You can cut the spinal cord, crush it, remove a segment, and it will regenerate. You can cut the limbs at any level—the wrist, the elbow, the upper arm—and it will regenerate, and it’s perfect. There is nothing missing, there’s no scarring on the skin at the site of amputation, every tissue is replaced. They can regenerate the same limb 50, 60, 100 times. And every time: perfect."

As you can probably guess, by studying regeneration in axolotls, scientists hope to figure out how to give humans this ability. Well, that seems like a stretch, but even if they don't figure out how to give humans the ability, understanding the process will likely result in other medical breakthroughs.

As if that weren't intriguing enough to scientists, axolotls are also 1,000 times more resistant to cancer than humans and other mammals. And, they can accept transplanted organs from other axolotls without ever rejecting the organs.

No wonder these critters are so common in research labs!

By the way, here's what the original wild axolotls looked like:

Unfortunately, they're pretty much gone in the wild. Remember, one of the lakes they lived in is now gone, and the other has been converted to canals. And this is in Mexico City, one of the largest cities in the world, where water pollution is a concern. In 1998, a survey was done in the canals that used to be the lake axolotls lived in, and scientists found a density of 6,000 axolotls per square km. A similar survey in 2003 found 1,000 per square km, and in 2008 they found only 100 per square km. In 2013, a four-month search found exactly zero axolotls.

Surprisingly, soon after that search, two axolotls were spotted in one of the canals. So, it is possible that a few wild ones are still alive in the canals.

I suppose it's a good thing axolotls thrive in captivity. In fact, there may be a greater number of them in captivity around the world than the number that ever lived in the two lakes of their original native range.

Finally, axolotls have long been culturally important in Mexico. According to legend, the axolotl is actually the Aztec god of fire and lightning, named Xolotl, who disguised himself as a salamander to avoid being sacrificed. Why? Because the Aztec gods were supposed to sacrifice themselves to the sun, to keep it alive and moving across the sky.

In Mexico City, axolotls are depicted on billboards, the sides of buildings, and even on the sides of tour buses.

In 2020, Mexico decided to use an image of an axolotl on its new 50-peso bill.

So, the Axolotl deserves a place in the W.A.H.O.F.

(Wizard Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word wizard, as you can imagine, is quite old. It originated in the early 1400s, and then it meant "philosopher or sage." It came from the Middle English wys, which meant "wise." It wasn't until about 1550 that the word was used to mean someone "with magical power." This happened because the distinction between philosophy and magic became blurred during the middle ages. Much, much later, in 1922, people (particularly British people) began using wizard as an adjective to mean "superb, outstanding."

So, wizard is another way to say awesome (at least in the UK)!

Photo Credits:

- Tiger salamander - DepositPhotos

- Axolotl #1, facing left, brown background - DepositPhotos

- Axolotl #2, closeup of brown, speckled face - DepositPhotos

- Axolotl #3, white, facing camera - DepositPhotos

- Axolotl #4 - wild brown color - DepositPhotos

Published on February 02, 2022 07:38

January 16, 2022

Awesome Animal - Tasmanian Devil

When I was a kid, I didn't realize the Tasmanian devil was a real animal. I thought it was just that crazy, snarling, slobbering Looney Tunes cartoon character. I still like Taz, but it turns out there is a real Tasmanian devil, and the two don't look much like each other.

What the heck is a Tasmanian Devil?

First of all, Tasmanian devils are carnivorous marsupial mammals. Marsupials are characterized by giving birth to very underdeveloped young (often smaller than a jelly bean). The young then move into a pouch on the female's body, attach themselves to a nipple, and go through most of their development in the pouch instead of inside the mother's body. Placental mammals (including humans), on the other hand, go through extensive development inside the mother's body before being born, and they get nutrients from the mother's blood through a placenta.

Tasmanian devils are now the largest carnivorous marsupials. They've only held this title since 1936, which is when the thylacine (the Tasmanian tiger) became extinct. Tasmanian devils are about the size of a small dog, with an average weight of 18 pounds (8 kg) for males and 13 pounds (6 kg) for females.

Devils are found mainly on the Australian island state of Tasmania, although a small population has been reintroduced to mainland Australia, where devils have been extinct for hundreds of years.

Early European settlers gave this animal the name devil after seeing the creature display some of its rather bizarre behaviors when feeding and defending its food, including baring its teeth, lunging at anything that gets near, and emitting frightening screeches and growls. As you can probably guess, these behaviors are also what inspired the crazy Looney Tunes character.

Amazing Facts about Tasmanian Devils

First, let's consider this animal's reputation for being insanely aggressive. Is this reputation deserved? Yes and no. Yes, they fiercely defend themselves when attacked, but so do many other animals. They open their mouths wide, baring their teeth, but this is usually just a threatening gesture.

Devils are typically solitary, but the smell of a dead animal carcass will bring them together to feed. One of the rituals of this type of feeding is that they aggressively jockey for a good feeding position on the carcass. It's important to point out that many of their aggressive feeding behaviors do not actually involve physical harm. Studies have found that they use twenty different aggressive postures and eleven different aggressive sounds to intimidate each other without actually fighting. Their famous open-mouth yawn is an example of an aggressive gesture. Sometimes they stand on their hind legs and "spar," shoving each other with their front paws and their snouts.

That being said, the posturing and sparring doesn't always work, and devils do resort to vicious fighting. Scars from these fights are commonly seen on their faces and rumps, particularly in the males, who also fight during the breeding season.

Check out this video on the devil's aggressive behavior.

Tasmanian devils can bite really hard. Due to the arrangement of skull bones and jaw muscles, devils have a bone-crushing bite. In fact, they have one of the strongest bites (per unit of body mass) of any mammal. Their heads and necks are proportionally large compared to their body size. These strong jaws allow them to eat the entire bodies of their prey (and carrion), including the bones. In fact, devils have teeth that are adapted to feeding on bones. They have the same number of teeth as dogs, but unlike dogs their teeth grow continuously throughout their lives, which is important if you are constantly chewing on things as hard as bones.

Speaking of eating, Tasmanian devils are predators, but they are also opportunistic, and they actually feed on carrion (which they find with a keen sense of smell) more often than they feed on animals they kill. When hunting, one of the devils' favorite prey is the wombat, which is relatively easy to kill. They also hunt small wallabies and other smallish marsupials, as well as birds, reptiles, frogs, fish, and domestic farm animals. They will eat just about any dead animal they find, including fish washed ashore and roadkill. They have even been known to dig up dead animals that people have buried. They were seen excavating a horse that had died of disease and had been buried.

When Tasmanian devils find or kill a meal, they really take advantage of the available food. They gorge themselves, sometimes eating as much as 40% of their body weight in one day! When food is abundant, they are able to store fat in their tail. In fact, a good sign of a healthy devil is a nice, plump tail.

Um, this may seem a bit disturbing, but Tasmanian devils have a habit of falling asleep inside the carcasses of large carrion animals. This allows them to defend the carcass from other scavengers, and it's also a matter of convenience—they can start eating again immediately after waking up.

Tasmanian devils are athletic. They are excellent tree climbers and swimmers, as well as long-distance runners. A devil can maintain a pace of 15 miles per hour (24 km/hr) for an hour straight.

When it comes to mating season, you probably won't be surprised that male devils fight aggressively over females (I guess fighting is just a way of life for these pugnacious critters). The females then mate with the winning males. Sometimes the pair will mate off and on for up to eight days, and the male sticks around to guard the female, preventing other males from mating with her.

Females give birth standing up, which is not a problem, considering each baby isn't much bigger than a grain of rice (remember, that's how marsupials do things... the babies develop outside the body instead of inside). Here's where things get a little weird. The female gives birth to 20 to 30 tiny young, and the babies have to race to the pouch. Why? There are only FOUR nipples in the pouch. That means most of the young will not survive, so getting to one of the four nipples quickly is literally a matter of life and death.

The surviving young develop inside the pouch for about three months. After the mother kicks them out, they continue living in the underground den for another three months before going out on their own. Baby devils are called joeys, pups, or imps.

So, the Tasmanian Devil deserves a place in the S.A.H.O.F.

(Slick Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word slick has a long and diverse history, with numerous meanings. It may have originated in about 900 A.D. from the Norwegian word slikja, which was a verb meaning "to make something smooth," like making a rough piece of wood smooth. Starting in the 1620s, the word slick was used as a noun for a type of cosmetic. Then starting in 1849 it was used as a noun for a smooth surface of the water caused by spilled oil (an oil slick). Of course, here we are using it as an adjective. Starting in the 1590s, it was used as an adjective to describe someone who is "clever in deception." Finally, in 1833, it became a slang adjective meaning "wonderful, first-rate, excellent." Example: "The new Rampage Ridge is one slick thriller."

So, slick is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

- Looney Tunes Tasmanian Devil - Wikimedia Commons

- Tasmanian devil 3D rendering on white background - DepositPhotos

- Tasmanian devil with its mouth open - DepositPhotos

- Two Tasmanian devils fighting - DepositPhotos

- Tasmanian devil, fat and lounging on the ground - DepositPhotos

- Tasmanian devil running, on white background - DepositPhotos

- Two baby Tasmanian devils handled by zoo employee - DepositPhotos

What the heck is a Tasmanian Devil?

First of all, Tasmanian devils are carnivorous marsupial mammals. Marsupials are characterized by giving birth to very underdeveloped young (often smaller than a jelly bean). The young then move into a pouch on the female's body, attach themselves to a nipple, and go through most of their development in the pouch instead of inside the mother's body. Placental mammals (including humans), on the other hand, go through extensive development inside the mother's body before being born, and they get nutrients from the mother's blood through a placenta.

Tasmanian devils are now the largest carnivorous marsupials. They've only held this title since 1936, which is when the thylacine (the Tasmanian tiger) became extinct. Tasmanian devils are about the size of a small dog, with an average weight of 18 pounds (8 kg) for males and 13 pounds (6 kg) for females.

Devils are found mainly on the Australian island state of Tasmania, although a small population has been reintroduced to mainland Australia, where devils have been extinct for hundreds of years.

Early European settlers gave this animal the name devil after seeing the creature display some of its rather bizarre behaviors when feeding and defending its food, including baring its teeth, lunging at anything that gets near, and emitting frightening screeches and growls. As you can probably guess, these behaviors are also what inspired the crazy Looney Tunes character.

Amazing Facts about Tasmanian Devils

First, let's consider this animal's reputation for being insanely aggressive. Is this reputation deserved? Yes and no. Yes, they fiercely defend themselves when attacked, but so do many other animals. They open their mouths wide, baring their teeth, but this is usually just a threatening gesture.

Devils are typically solitary, but the smell of a dead animal carcass will bring them together to feed. One of the rituals of this type of feeding is that they aggressively jockey for a good feeding position on the carcass. It's important to point out that many of their aggressive feeding behaviors do not actually involve physical harm. Studies have found that they use twenty different aggressive postures and eleven different aggressive sounds to intimidate each other without actually fighting. Their famous open-mouth yawn is an example of an aggressive gesture. Sometimes they stand on their hind legs and "spar," shoving each other with their front paws and their snouts.

That being said, the posturing and sparring doesn't always work, and devils do resort to vicious fighting. Scars from these fights are commonly seen on their faces and rumps, particularly in the males, who also fight during the breeding season.

Check out this video on the devil's aggressive behavior.

Tasmanian devils can bite really hard. Due to the arrangement of skull bones and jaw muscles, devils have a bone-crushing bite. In fact, they have one of the strongest bites (per unit of body mass) of any mammal. Their heads and necks are proportionally large compared to their body size. These strong jaws allow them to eat the entire bodies of their prey (and carrion), including the bones. In fact, devils have teeth that are adapted to feeding on bones. They have the same number of teeth as dogs, but unlike dogs their teeth grow continuously throughout their lives, which is important if you are constantly chewing on things as hard as bones.

Speaking of eating, Tasmanian devils are predators, but they are also opportunistic, and they actually feed on carrion (which they find with a keen sense of smell) more often than they feed on animals they kill. When hunting, one of the devils' favorite prey is the wombat, which is relatively easy to kill. They also hunt small wallabies and other smallish marsupials, as well as birds, reptiles, frogs, fish, and domestic farm animals. They will eat just about any dead animal they find, including fish washed ashore and roadkill. They have even been known to dig up dead animals that people have buried. They were seen excavating a horse that had died of disease and had been buried.

When Tasmanian devils find or kill a meal, they really take advantage of the available food. They gorge themselves, sometimes eating as much as 40% of their body weight in one day! When food is abundant, they are able to store fat in their tail. In fact, a good sign of a healthy devil is a nice, plump tail.

Um, this may seem a bit disturbing, but Tasmanian devils have a habit of falling asleep inside the carcasses of large carrion animals. This allows them to defend the carcass from other scavengers, and it's also a matter of convenience—they can start eating again immediately after waking up.

Tasmanian devils are athletic. They are excellent tree climbers and swimmers, as well as long-distance runners. A devil can maintain a pace of 15 miles per hour (24 km/hr) for an hour straight.

When it comes to mating season, you probably won't be surprised that male devils fight aggressively over females (I guess fighting is just a way of life for these pugnacious critters). The females then mate with the winning males. Sometimes the pair will mate off and on for up to eight days, and the male sticks around to guard the female, preventing other males from mating with her.

Females give birth standing up, which is not a problem, considering each baby isn't much bigger than a grain of rice (remember, that's how marsupials do things... the babies develop outside the body instead of inside). Here's where things get a little weird. The female gives birth to 20 to 30 tiny young, and the babies have to race to the pouch. Why? There are only FOUR nipples in the pouch. That means most of the young will not survive, so getting to one of the four nipples quickly is literally a matter of life and death.

The surviving young develop inside the pouch for about three months. After the mother kicks them out, they continue living in the underground den for another three months before going out on their own. Baby devils are called joeys, pups, or imps.

So, the Tasmanian Devil deserves a place in the S.A.H.O.F.

(Slick Animal Hall of Fame).

FUN FACT: The word slick has a long and diverse history, with numerous meanings. It may have originated in about 900 A.D. from the Norwegian word slikja, which was a verb meaning "to make something smooth," like making a rough piece of wood smooth. Starting in the 1620s, the word slick was used as a noun for a type of cosmetic. Then starting in 1849 it was used as a noun for a smooth surface of the water caused by spilled oil (an oil slick). Of course, here we are using it as an adjective. Starting in the 1590s, it was used as an adjective to describe someone who is "clever in deception." Finally, in 1833, it became a slang adjective meaning "wonderful, first-rate, excellent." Example: "The new Rampage Ridge is one slick thriller."

So, slick is another way to say awesome!

Photo Credits:

- Looney Tunes Tasmanian Devil - Wikimedia Commons

- Tasmanian devil 3D rendering on white background - DepositPhotos

- Tasmanian devil with its mouth open - DepositPhotos

- Two Tasmanian devils fighting - DepositPhotos

- Tasmanian devil, fat and lounging on the ground - DepositPhotos

- Tasmanian devil running, on white background - DepositPhotos

- Two baby Tasmanian devils handled by zoo employee - DepositPhotos

Published on January 16, 2022 13:38

January 1, 2022

Awesome Animal - Christmas Tree Worm

A number of different animals have been given Christmas-themed names. For example, the candy cane shrimp. Although not an animal, there is the common house plant called the Christmas cactus. Christmas Island, an Australian territory in the Indian Ocean, has several animals with Christmas names, such as the Christmas imperial pigeon, the Christmas frigatebird, and my favorite, the Christmas boobook (sometimes called the Christmas hawk-owl).

The Christmas tree worm got its name because it has two "crowns" that stick up, looking very much like two tiny Christmas trees.

What the heck is a Christmas Tree Worm?

Christmas tree worms (Spirobranchus giganteus) are marine worms that live on coral reefs in tropical areas around the world. They are polychaetes, which are segmented, burrowing worms. They attach themselves to the coral then grow a hard, calcium carbonate tube around their body for protection. The tube attaches to the coral. and the coral often grows around the tube. The worm never leaves that spot for the rest of its life.

Their flowery crowns come in a variety of colors, and the worm's body is only about 1.5 inches (3.8 cm) long. Although they are small, these worms are easily spotted when they have their crowns protruding from their coral burrow.

Check out the variety of colors below.

Amazing Facts about Christmas Tree Worms

First, let's talk about those beautiful Christmas tree structures. Maybe it's just me, but these structures look like something from a Dr. Seuss picture book. But what are they? The two crowns are highly specialized mouthparts called palps. They help with feeding and with getting oxygen from the water. Each of those spiral appendages is covered with feathery tentacles. The tentacles have numerous, tiny, movable, finger-like structures called cilia. When planktonic prey animals get caught in the tentacles, these cilia move the prey down into the worm's mouth.

Although the Christmas tree crowns are mainly used to capture prey, they also help the worm breathe. Therefore, the crowns are often called gills, but that's not really a correct name.

When threatened, Christmas tree worms can pull these crowns into their burrow really fast, within just a few milliseconds. Once their feathery plumes are pulled inside their tube burrow, they move another modified mouthpart called an operculum into place over the opening. The operculum is hard and serves as a protective hatch, making the worm safe in its burrow.

Check out this beautiful video showing numerous Christmas tree worms emerging from their tubes. If you watch closely you can see the operculum moving aside as they emerge.

Amazingly, Christmas tree worms can live for 40 years or more, particularly in pristine, unpolluted coral reefs.

Let's consider how these worms reproduce. Keep in mind that they stay in their tube their entire adult life, so they cannot crawl around to find mates. Because they're anchored to one spot, they've developed a specialized way to sexually reproduce. The females simply release unfertilized eggs into the water, and the males release sperm into the water. The water currents carry the eggs and sperm away. If the worms are lucky, some of the sperm will meet some of the eggs. This method of reproduction is called broadcast spawning.

Once an egg is fertilized, it becomes a larva very quickly, within 24 hours. The larvae drift around with all the other plankton for 9 to 12 days as they grow. When it's time to settle down, they attach to a coral rock and start growing their hard calcium carbonate tube, in which they will live out their life, eventually starting the life cycle all over again be releasing eggs or sperm into the water.

Although the worm itself is only 1.5 inches (3.8 cm) long, the tube it constructs is often 8 to 10 inches (20 to 25 cm) long. So, even though they stay inside their tube, I guess they have at least a little room to move around.

The most common predators of Christmas tree worms are shrimp, crabs, and sea urchins. Some fish also feed on them. Usually, though, these predators only bite off the tree-like crowns. When that happens, the worms can regrow their crowns in a few weeks. Christmas tree worms are often collected by humans because their bright colors make them desirable to aquarium enthusiasts. That's a relatively minor threat to the population, though. Not surprisingly, the biggest threat to these worms is the destruction of coral reefs due to pollution and climate change.

So, the Christmas Tree Worm deserves a place in the P.A.H.O.F.

(Posh Animal Hall of Fame).