Matthew J. Distefano's Blog, page 6

January 2, 2020

Third Sunday of Advent

When John heard in prison what the Messiah was doing, he sent word by his disciples and said to him, ‘Are you the one who is to come, or are we to wait for another?’Jesus answered them, ‘Go and tell John what you hear and see:the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor have good news brought to them.And blessed is anyone who takes no offense at me.’

As they went away, Jesus began to speak to the crowds about John: ‘What did you go out into the wilderness to look at? A reed shaken by the wind? What then did you go out to see? Someone dressed in soft robes? Look, those who wear soft robes are in royal palaces. What then did you go out to see? A prophet? Yes, I tell you, and more than a prophet. This is the one about whom it is written,

‘See, I am sending my messenger ahead of you,

who will prepare your way before you.’Truly I tell you, among those born of women no one has arisen greater than John the Baptist; yet the least in the kingdom of heaven is greater than he.” ~ Matthew 11:2–11

Today’s passage, like the one from December 8, gives

us insight into John the Baptist and who he thought Jesus to be. As we

discussed in the last entry, John thought Jesus was going to bring deliverance

with retributive judgment and wrath. Jesus, however, had a different approach,

which he lends clues to in how he responds to John’s disciples. When he answers

the question “Are you the one who is to come, or are we to wait for another?”

he does so, not by giving a yes or no answer, but by quoting various passages

from Isaiah, as well as 1 and 2 Kings (Isa 29:18; 35:5, 6; 61:1–2; 1 Kgs

17:17–34; 2 Kgs 5). What is interesting to note is that all of these passages

have associated vengeance texts surrounding the verses Jesus quotes, yet none

are referenced by Christ. For instance, when he quotes Isaiah 61:1–2, he leaves

off the phrase “and the day of vengeance of our God.” When he quotes Isaiah

29:18, he leaves off the phrase “for the tyrant shall be no more, and the

scoffer shall cease to be, all those alert to do evil shall be cut off.” And so

on and so forth with the passages from Isaiah 35:5, 6, 1 Kings 17:17–34 and 2

Kings 5.

It is this type of messiahship that confounds John and

those who thought like him. Again, much of what was expected by the messiah

involved divine wrath and retribution. For many, the messiah was going to come

in like a Davidic warrior-type. As Matthew 11:12 states, the kingdom of God had

been taken over by violence, and it was going to be with violence that brings about

perpetual peace. But no, not for Jesus.

This, mind you, was not going to be some passive

messiahship, however. Sure, retribution and violence weren’t going to be Jesus’

modus operandi, but deliverance would still come. This is what Walter Wink is

referring to when he says that Jesus had a “third way.” Jesus wouldn’t use

violence to bring about what the kingdom of God was going to look like, but he

was going to use it in order to blow apart the notion that violence works in

achieving long-lasting peace.

This way of deliverance caused scandal among both

Jesus’ and John’s disciples. It caused offense. But Jesus wants John’s

disciples to know that those who are not offended by his words and actions will

be blessed. In other words, if people chose to follow Jesus, they would be able

to break free from the scandal of mimetic rivalry and the subsequent violence

that inevitably comes. They would be able to follow the one who follows the

non-rivalrous Father, and this would be considered a blessed way of living in

and among a kingdom that had suffered violence for far too long.

Second Sunday of Advent

“‘In those days John the Baptist appeared in the wilderness of Judea, proclaiming,‘Repent, for the kingdom of heaven has come near.’This is the one of whom the prophet Isaiah spoke when he said,

‘The voice of one crying out in the wilderness:

‘Prepare the way of the Lord,

make his paths straight.’Now John wore clothing of camel’s hair with a leather belt around his waist, and his food was locusts and wild honey. Then the people of Jerusalem and all Judea were going out to him, and all the region along the Jordan, and they were baptized by him in the river Jordan, confessing their sins.

But when he saw many Pharisees and Sadducees coming for baptism, he said to them, ‘You brood of vipers! Who warned you to flee from the wrath to come? Bear fruit worthy of repentance. Do not presume to say to yourselves, ‘We have Abraham as our ancestor’; for I tell you, God is able from these stones to raise up children to Abraham. Even now the ax is lying at the root of the trees; every tree therefore that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire. I baptize you with water for repentance, but one who is more powerful than I is coming after me; I am not worthy to carry his sandals. He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and fire. His winnowing fork is in his hand, and he will clear his threshing floor and will gather his wheat into the granary; but the chaff he will burn with unquenchable fire.’” ~ Matthew 3:1–12

It is fairly obvious that John the Baptist took inspiration from the prophet Isaiah. Isaiah often talked about how, when the messiah comes, social injustices were going to be leveled. Valleys would be filled in. Mountains would be brought down. Imagery like this. Further, it is also obvious that John the Baptist, like Isaiah before him, had an apocalyptic image of God that included what we can only call “wrath.” In other words, in John’s mind, in order for social injustices to be leveled, God was going to intervene with apocalyptic wrath and destruction. This is why, as he so clearly states here in verse 12, the one coming after him (i.e., Jesus) will burn the chaff with “unquenchable fire.” It will be because the wrath of God burns in such a way so as to destroy those who are committing the injustices against God’s people.

Jesus, on the other hand, never really behaves in the

same way John expects. This is why, in Luke 7:18–23, we have an account of John

sending his disciples to question Jesus about whether he is “the one” or not. To

put it simply, John is torn because, on the one hand, he wants to believe Jesus

is the chosen one, but on the other, isn’t witnessing the type of behavior

expected of such a chosen one. John expects the messiah to come in with guns

blazing, but Jesus has a different tactic (and theology, for what it’s worth).

We see this most clearly in Luke 4, during Jesus’ first “sermon” in the

synagogue in Nazareth. When Jesus reads from Isaiah 61:1–2—the passage about

the Day of Jubilee—he omits a key phrase that nearly gets him killed: “the day

of vengeance of our God.” Again, in order for the valleys to get filled and the

mountains brought low, God’s wrath and vengeance were going to have to be on

full display. The people knew this. The “Bible” was clear. Isaiah believed

this. John the Baptist believed this. But it was not so for Jesus. This is what

confounded John and the people of Nazareth.

This is why it is always important to put things in

their proper context. Sure, today’s passage has a destructive tone. An ax

chopping down a true. Chaff burning with unquenchable fire. But that’s just how

some folks thought of things. The Jews were an oppressed people, but also

believed that one day they would be liberated. Fair enough! That was what was

promised to them through Abraham. They just didn’t quite understand the “how”

of the equation. To our human minds, it only makes sense that our oppressors

will have to be utterly destroyed in order for us to be free. But for Jesus,

the true messiah, well, he had a different way of going about things. For him,

deliverance was coming, the kingdom of God was coming, but it was going to be

inaugurated without any such violence and wrath. This is what makes Jesus a

truly unique messiah.

First Sunday of Advent

“But about that day and hour no one knows, neither the angels in heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father. For as the days of Noah were, so will be the coming of the Son of Man. For as in those days before the flood they were eating and drinking, marrying and giving in marriage, until the day Noah entered the ark, and they knew nothing until the flood came and swept them all away, so too will be the coming of the Son of Man. Then two will be in the field; one will be taken and one will be left. Two women will be grinding meal together; one will be taken and one will be left. Keep awake therefore, for you do not know on what day your Lord is coming. But understand this: if the owner of the house had known in what part of the night the thief was coming, he would have stayed awake and would not have let his house be broken into. Therefore you also must be ready, for the Son of Man is coming at an unexpected hour.” ~ Matthew 24:36–44

The Left Behind series of books are some of the

most popular to ever grace the bookshelves of American Christian bookstores.

This is a shame. And a sham. Why? Because they are bogus. Bunk. Christian

fiction of the highest order. And while there is biblical merit—if we want to

even call it that—it takes a twisting and manipulation of the texts in order to

get to a place where we seriously think the Bible argues that in the last days,

Christians will be raptured up to heaven while the rest of humanity is left to

face the destruction of the planet, and thus, their own miserable deaths.

Sadly, today’s text is one of those that gets used to place Christians into the

shackles of fear.

This doesn’t have to be the case, however. If we look

closely at the text, we’ll actually see that the opposite of what the Rapture

theologians teach is true. So, to begin, let’s compare the Greek words for

“taken” (paralambano) and “left” (aphiemi), because this is where

things get rather interesting. The Friborg Lexicon has this to say about the

word we translate to “left,” as in “left behind:”

(1) send off or away, let go (MT 27.50); (2) as a legal technical term divorce (1C 7.11); (3) abandon, leave behind (MT 26.56); (4) of duty and obligation reject, set aside, neglect (MK 7.8); (5) of toleration let go, leave in peace, allow (MK 11.6); (6) of sins or debts forgive, pardon, cancel (LU 7.47); (7) give or utter a loud cry (MK 15.37).

Did you notice that? To

be “left behind” is to be forgiven. Rapture theology teaches the opposite:

those left behind are those who are left to face life without peace, mercy,

forgiveness, and so on. But the text in Matthew 24 teaches that those left

behind are really those who, like Noah before the flood, are faithful and thus

are those who are spared from the coming destruction.

So, what, if not a flood

of epic proportions sent by God to smite the wicked, is this passage all about?

To answer that, we’ll have to get anthropological because, if you aren’t yet

aware, the flood that happened in the days of Noah is completely due to the

rising tide of violence that humanity—not God—caused. We’ll also have to take a

look at the “son of man” phrase because that will be key in understanding what

is really going on here.

First, let’s look at what

causes the flood in Genesis. In Genesis 6:5, the writer states that “every

inclination of the thoughts of their hearts was only evil all the time.” So, in

other words, as Michael Hardin points out in The Jesus Driven Life, this

is a psychological explanation for the problem of evil.[1] To put it simply, it’s an

issue of the heart: the inclination of the heart is mediated desire derived

from the imitation of those around us. In Genesis 6:11, the writer then tells

us what this leads to: “the earth was corrupt in God’s sight and full of

violence.” Corrupt hearts, full of evil inclinations, and saturated with human

violence. This is the cause of the flood.

Now, I will admit that

the writer(s) of Genesis indeed state that God sends the flood to wipe out

humanity because of our propensity toward violence and corruption. But that

need not be our theology. We have Jesus, and if there is one thing that we’ve

learned about Jesus, it’s that he tends to do a number on our theological

presuppositions. This is where the “son of man” phrase comes into play.

You see, the phrase “the

son of man” was, first off, Jesus’ favorite self-designation and secondly, only

used by him. No one else calls him that. Why is this important? Because the

phrase is used by him as a corporate designation, meaning that when Jesus uses

it, it’s to say that he is a stand-in for all of humanity. And if Jesus is God,

as any good Trinitarian theologian would suggest, then that means that

God—Jesus—identifies with humanity in spite of our violence and corruption. He

doesn’t imitate our violence by bringing about even bigger violence; he stands

with us in the midst of it, refusing to imitate it all the while. This is

important because, on the one hand, Jesus is the key figure who doesn’t get

caught up in the rising tide of violence that was around him. Although

corruption and violence were going to be coming down onto Jerusalem within that

generation, Jesus was going to be the beacon of hope, the ark, that withstands

such a flood. But on the other hand, the invitation is sent out to anyone who

wants to join him in being “left behind” to stand in solidarity with the

nonviolent Lord. As Paul Neuchterlein writes, “We are called to follow in the

footsteps of his [Jesus’] faithfulness. Baptized, we are those who die and rise

with him so that we might also be left behind when the next rising tide of

human violence rolls our way. We are those who resist joining in. Living in

faith, we do not get carried away.”[2]

Amen to that. Resist

corruption and violence, and be left behind with Jesus to confidently face the

evil of this world.

[1] Hardin, The Jesus Driven Life,

189.

[2] Neuchterlein, “Advent 1A,” sec. 4,

para. 7.

October 2, 2017

5 Things We’ll Miss if We Take the Bible Too Literally

We all want certainty. I get that. It makes us feel better about ourselves. It makes us feel all warm and fuzzy inside. It makes us feel like the big, bad monster we call “Doubt” isn’t going to get us.

So it is no wonder that, when approaching the Scriptures, many of us opt for literalism above all else. It gives us that sense of security, that sense that we have a grasp on the situation. However, I’ve discovered throughout my long and winding journey that the security we get from biblical literalism is nothing more than a façade. And, when that foundational card in our meticulously built house gets yanked out, down goes the whole thing; our faith crumbles and we are left without even a basic foundation. To use comedian Pete Holmes’ analogy, we are left with an apartment void of all furniture.

Furthermore, when we approach the Bible too literally, we are doing nothing more than embarking on an adventure in missing the point. Sure, we think we are being faithful servants of the almighty God — and perhaps some of us really are — but what we are primarily doing is nothing more than defending a position that, ironically, the Bible never asks us to defend. And when we do this, we end up missing a ton of great things that go on throughout the Bible. I’d like to mention 5 of them.

1. The Theology of Jesus

There are so many things said about God in the Bible, from the slightly obscure to the out-and-out insane. I won’t get into all of them here — as if we have the time or space — but those of us who use our brains from time to time know what I’m talking about. So, when we believe that every theological claim made by every writer of every book of the Bible is undeniably true, that it is theologically on-point at every turn, we hardly leave any room for Jesus to offer any critique. For instance, when we literally believe Deuteronomy’s claim that “If you do not diligently observe all the words of [the] law that are written in this book [Torah], fearing the glorious and awesome name, the Lord your God, then the Lord will overwhelm both you and your offspring with severe and lasting afflictions and grievous and lasting maladies,” then when we turn to John 9, we end up in a bit of a conundrum. Why? Because this is not what Jesus teaches.

In John 9, when Jesus is pressed on the issue of intergenerational curses, Jesus doesn’t affirm the cultural norm that people are afflicted by God with grievous and lasting maladies for failing to observe every jot and tittle of Torah, but that grievous and lasting maladies afflict people so that “God’s works might be revealed.” What are God’s works? Contrary to Deuteronomy 28, where it is claimed that God is a blessing and cursing God, God’s works are wholly for the purpose of blessing (Matt 5:45), for healing and restoring: “When he had said this, he spat on the ground and made mud with the saliva and spread the mud on the man’s face, saying to him, ‘Go, wash in the pool of Siloam.’ Then he went and washed and came back able to see.”

Indeed, there are other cases where Jesus reorients our way of theologizing, but I don’t have the space to discuss that here. If you are interested, pick up my book From the Blood of Abel and then, when you’ve digested that, Michael Hardin’s The Jesus Driven Life.

2. The Old Testament Dialogue

This may come as a surprise to some, but it’s not just Jesus who critiques the views of his people. The writers (primarily the prophets) of the Hebrew Bible do this too. In other words, the Old Testament is a dialogue about, among other things, God and God’s nature. For one example of this, consider what happened to Jezreel.

In 2 Kings 9, there is an account of a massacre at this place by the hands of a man named Jehu. What happens is that Jehu is ordered — nay, anointed — by the prophet Elijah to strike down the entire house of his master Ahab over their tyranny and wickedness (2 Kings 9:7–8). So, he does! And he is championed as a righteous man of God for doing so.

A few generations later, however, the prophet Hosea sees things differently. Speaking on behalf of the Lord, Hosea writes: “For in a while I will punish the house of Jehu for the blood of Jezreel, and I will put an end to the kingdom of the house of Israel” (Hos 1:4). In other words, according to Hosea, God is not all-too-pleased with what the murderous zealot Jehu did to the house of Ahab. This, in spite of Elijah’s commanding such a thing.

This move away from violence is a key component to the overarching biblical metanarrative, but it is a move that is far from a neatly drawn straight line. Rather, the Bible is a “text in travail,” as René Girard calls it, and as such what needs to happen is that the Bible needs to be “rightly divided,” rather than always being taken so literally.

3. The Opportunity to be Credible in the Modern World

It’s quite laughable that, to this day, some of us think Genesis 1 is attempting to put forth a scientific explanation of creation. I mean, you’d think the fact that the sun is not said to be created until the fourth day would be enough evidence for us to conclude the days in this story are something other than literal 24-hour periods. And yet, many of us continue in our ignorance.

I find this sad, because not only does this rampant literalism prevent us from gleaning some of the actual theological and anthropological nuggets Genesis 1 presents (as in, when we compare it with the Babylonian myth Enuma Elish), it also forces us to under-appreciate any and all scientific discovery. And when this happens, we end up looking rather silly in the process. Anyone who uses their brain knows that it is ridiculous to think that, somehow, someway, Noah literally got all of the thousands of species of animals onto a wooden ark and cared for them for months without having all manners of chaos ensue; that Lions and tigers and bears — Oh my! — all swore off being carnivores because they understood the survival of their species depended on them becoming vegans. So, when Christians turn off their brains and say otherwise, it in turn only turns off critically thinking folks who could actually use the Gospel in their lives. All for the sake of taking the Bible literally.

4. The Psychology of “the Fall”

Snakes don’t talk. But many readers of the Bible point to Genesis 3 as evidence that some snakes do. This is silly. Something else is going on here, something we’ll miss if we hold fast to a literal reading of Genesis 3 and 4.I’ll begin by saying that the serpent is used as an analogy. It represents the type of corrupted, twisted desire that arises when prohibitions are placed on things (René Girard’s work has gone a long way in teasing out the specifics of phenomenon). Notice the corruption in the very first question asked of Eve: “Did God not say, ‘You shall not eat from any tree in the garden?’” (Gen 3:1) As we know, that is not what God said. There is only one prohibited tree, not many. This is a trap. Sure, Eve initially corrects the serpent, but she then imitates it by making up her own lie. It’s subtle, but it’s there, plain as day. She answers: “You shall not eat of the fruit of the tree that is in the middle of the garden, nor shall you touch it, or you shall die” (Gen 3:3, emphasis mine). So, what began with one prohibition has now been twisted into two.Initially, however, nothing happens to Eve. It is only after the man — who was there with her the whole time — eats of the fruit that both of their eyes are opened. This suggests that all three of the characters — the serpent, Eve, and Adam — are connected in a certain way. In other words, as Michael Hardin points out: “All of this literarily suggests that the man, the woman and the serpent are one big figure of the process of mediated desire and its consequences.” What are these consequences? Initially, accusations and scapegoating: the man blames both God and the woman (Gen 3:12), then the woman follows by turning it back onto the serpent (Gen 3:13).

The story goes on, and more consequences follow. What begins with a lie in chapter 3 quickly turns into a murder in chapter 4. In his grasping for God’s blessing, Cain kills Abel. Brother rises up against brother. Then Cain founds a city; civilization built upon blood. From there, violence escalates until the whole world is corrupt and full of wickedness.

Again, to read the “fall” literally ensures that we will miss much of this look into our psychology and how it relates to violence. It ensures that instead of digging deeper for further levels of meaning, we’ll be content to just skim the surface.

5. The Profundity of John’s Revelation

The book of Revelation is scary, amiright? At least, it was for me. I mean, dragons and fire and slaughter — that’s enough to keep any kid up at night. But that’s all changed now, since I don’t take it all so literally anymore.

And once I ceased believing in literal multi-headed, multi-horned creatures who were going to devour my face off, I was able to see how profound this book actually can be. For instance, I was able to see the insights this book gives regarding where the violence of empire leads to; and in contrast, I was able to see just how powerful the Gospel can be in overcoming such violence. Before, though, I couldn’t; I could barely keep from going insane over whether I would be raptured or not, whether I would be thrown into a literal lake of fire or not.

Whether we take seriously or not where our violence is taking humanity remains to be seen. That in itself is scary. But, if we can step back and see the forest in spite of all the individual trees, we can see that we have a promise: The gates of New Jerusalem never shut (Rev 21:25). So, may we heed the warnings in this book so that we can help bring about, insofar as we are able, the kingdom of God. And may all join us in the call to enter the blessed City.

July 26, 2017

Problematizing Biblical Inerrancy

It seems safe to say that most Christians — whether Catholic, Protestant, Orthodox, Anabaptist, or something else entirely — believe they are generally correct in their doctrinal views. Otherwise, why would they have them? This is not necessarily a bad thing, since there is nothing wrong with loosely holding onto beliefs we find credible. However, many of these folks — mainly Protestants who affirm an inerrant Bible — are not simply convinced about their beliefs, but are certain they are correct. Which makes those who differ wrong. Dead wrong.

In this piece, while I am not going to put forth a particular way to approach Scripture (I’ve done that here, here, and here), I am going to be a bit of a rabble-rouser and simply problematize things for folks who consider themselves inerrantists. After all, the first step to solving a problem is to admit there is one. And Houston, inerrancy has and is a problem.

Problem I: Jesus Takes a Back Seat to Scripture

If we begin our theological pilgrimage (as Karl Barth might call it) with an inerrant Bible, then we aren’t beginning with Jesus. And if we fail to start with Jesus, instead opting to start with a certain view of the book — or rather, books — that testify about him, how can we ever know the way in which Jesus himself approached his Scriptures? Is it enough to say that “because he quotes from Scripture, he therefore affirms it all?” Well, that would be highly irresponsible of us, as it assumes far too much and fails to lead us in asking some crucial questions, such as: How did he interpret Scripture? Did he follow a certain pattern? What did he even consider “Scripture?”

Furthermore, if we begin with the view that everything said in the Bible — even all the whacky stuff — testifies to the true nature of God, then we would be more than hard-pressed in saying, as Paul did, that Jesus is the fullness of God in bodily form (Col 2:9). In other words, with inerrancy, any theological truths that Jesus reveals become papered over by the whole of Scripture, instead of the whole of Scripture being read through the lens of the life, death, resurrection, and ascension of Christ.

This seems bass-ackwards!

Problem II: Sociological Problems Abound

When every jot and tittle of Scripture is assumed to be inerrant, real world problems arise. Turn your attention to John 9. In this story, Jesus and his disciples come across a societal outcast who was born blind. The disciples ask “Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?” But why do they assume this?

Well, this thinking comes straight from Deuteronomy 5 and 28. The Bible is clear:

Deut 5:9: You shall not bow down to them or worship them; for I the Lord your God am a jealous God, punishing children for the iniquity of parents, to the third and fourth generation of those who reject me.

Deut 28:18: Cursed shall be the fruit of your womb.

Deut 28:22: The Lord will afflict you with consumption, fever, inflammation.

Deut 28:27: The Lord will afflict you with the boils of Egypt; with ulcers, scurvy, and itch, of which you cannot be healed.

Deut 28:37: You shall become an object of horror.

Needless to say, when we take for granted that everything in Scripture is from God himself, we certainly run the risk of looking around at those in need and concluding that they are cursed — just like Job’s “friends” did all throughout the book of Job. And just like many of the folks did in Jesus’ day. Sadly, and since we are living post-Jesus, ironically, we still do this today.

Problem III: You Can’t Shed Your Subjectivity

No matter what objective truths are out there, we can never approach them objectively ourselves. We are always in first-person mode, bringing our own subjectivity to the table. Even if the Bible were written by God and contained zero historical, anthropological, psychological, or theological errors, we would still never be able to approach it objectively. We will always bring our presuppositions to our interpretation.

For one example of what I’m talking about, let’s think about Paul’s phrase pistis Christou. Is it the “faithfulness of Christ” or “faith in Christ” that saves us? Some scholars affirm the former, others the latter. What are we non-scholars to say? It makes a difference, because if it is the faithfulness of Christ that “reconciles the world to God,” then salvation is, first and foremost, an act of God. If, on the other hand, it is our faith in Christ that saves us, then salvation is, first and foremost, offered by God, but actualized by our faith. Our answer likely depends upon a whole host of factors, including any assumptions and presuppositions we may currently have.

Piggybacking on this, what is the “correct” biblical way of thinking about our “belief” in Jesus? As the Lord says in John’s Gospel, he is “the way” to the Father (John 14:6). But how are we to interpret this? As Michael Machuga points out in our book, A Journey with Two Mystics, this can mean a whole host of things. First, it could mean we simply must acknowledge that Jesus exists, that he is who he says he is — sort of like believing in Santa Claus. Or, it could mean believing that his way of living — his ethics, politics, and philosophy — is our model for living. And third, it could mean believing he accomplished what he set out to accomplish, namely, that he indeed conquered death and was victorious over sin and the devil.

At the end of the day, all these issues (and many more) are open for interpretation, whether we call our Bible inerrant or not.

Problem IV: Which Bible Are We Even Talking About?

When we make the claim that “the Bible is inerrant,” which canon are we referring to? Is it only the 66 book Protestant Bible? Or should we add some deuterocanonical books? Why? Why not? How would it change things if, for example, we had 1 Enoch in our canon (Jude probably did)? That instead of the Bible being 66 books, it was 80? Or 81, as the Ethiopian Orthodox Church suggests?

Furthermore, are only the original manuscripts (which we don’t have) inerrant or did the translations also stand the test of time? All of them? Even the ones that contradict each other? Even the ones with missing verses (the NIV doesn’t include John 5:4, Acts 8:37, and a few others)?

Problem V: The Bible Never Makes this Claim

The Bible simply never makes the claim that it is inerrant. (And even if it did, the logic would be entirely circular. And it still wouldn’t address our fourth problem.) Sure, there is that funky verse in 2 Timothy, but using it as some proof-text for inerrancy seems rather dubious.

First, there is no “is” in the Greek text. The writer simply begins the sentence with “Pasa graphe theopneustos kai,” which literally translates to “Every writing God-breathed and.” So, translators have to make a decision. Should it read: “All Scripture is inspired by God…” or “Every Scripture inspired by God is…” or “Every writing God-breathed is…” or something else entirely? Our answer makes a lot of difference here.

Second, given that the writer of 2 Timothy could not have possessed what we moderns call “the Bible,” one would have to conclude that what they meant by “Scripture/writing” was in relation to the Hebrew Scriptures. Forcing our canon of Scripture back into this text is anachronistic and fallacious.

All that said, even if we take what we call “the Bible” and determine it is all “God-breathed,” that hardly means it is inerrant (or infallible for that matter). Heck, the Bible clearly states that humanity is “God-breathed” — God breathes the ruach into the adama to create a living nefesh — but no one I know is clamoring on about how humanity is inerrant. Far from it, in fact! And I would agree with them.

In Closing

If you don’t happen to see the same problems with inerrancy that I do, then that is understandable. These are just the issues I was confronted with that forced me, after 25 years of living the Evangelical lifestyle, into the desert of deconstruction. Sure, when I “came out the other side,” Jesus was there, with the Scriptures in-hand, so that I could sit at his feet. But I didn’t always know this, so I empathize with those who think I am trying to “take away their Bibles.” I am not — I am just verbalizing the problems I, and others, have faced in our journey out of inerrancy. Do with it as you see fit.

Peace.

The post Problematizing Biblical Inerrancy appeared first on All Set Free.

June 22, 2017

REPOST: Jesus is the Reason the Bible is Not Innerant

Growing up, I was always told that the Bible was the inerrant Word of God. What is meant by this is that it is without error or fault in all of its teaching (see The Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy). Without even getting into what is considered “correct” canon—as that is not even agreed upon—if something in Scripture says “God said,” then that means “God said.” And if something says “God did,” then that means “God did.” So, for instance, in Numbers 25, when the writer says that God said to Moses, “Take all the chiefs of the people, and impale them in the sun,” then that means this conversation happened just as it is written. God literally, at one point in history, commanded murder so that his anger can be assuaged. And then, when Phinehas does just as God commanded, he is given a peace covenant.

Just let that sink in for a moment.

But this is just one of many stories like this contained throughout the Scriptures—where God commands others to spill blood in his name. And in theory, I guess it is possible that God is like this. It is possible that all of the stories in the Bible, where God is depicted as a bloodthirsty deity, are true. But then what do we do with the first-century pacifist name Jesus, who lived his life in servitude for others, never once committing an act of violence? Is his Gospel not a gospel of peace (Eph 6:15)? And is he not what God is like as a human? And did Paul—taking for granted he wrote Colossians—not describe him as the fullness of God in bodily form (paraphrasing Col 2:9)? And did Jesus himself not say that no one has ever seen God except for him (John 1:18)?

So what do we do with this?

Well, we could do what most Christians in the West do, namely create a Janus-faced God. We could say that Jesus reveals one side of God (i.e. his merciful side), while failing to reveal his wrathful side. Or, we could say that during one epoch of history (the Old Testament), God is vengeful, and then in another epoch (the first century) he is merciful—and then per the book of Revelation, he will return to vengeful.

But answers like these fail to get to the heart of my questions above.

Moreover, they fail to do us any good if we are supposed to think of God as a Father, or as Jesus so affectionately called him, Abba. And they fail to do us any good if God is to be thought of as the same yesterday, today, and forever, just as Christ is described by the writer of Hebrews (Heb 13:8). Because these answers don’t do a damn bit of good for us at all, we need to rethink our approach. We need to start with Jesus and work backward, so to speak.

Let’s start with John 1.

The writer begins, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God” (John 1:1). Now, to state what should be the obvious: the Word here is not the Bible. It is the Christ. It is not a book. It is a human.

John 1:1 is also a “rewrite” of Genesis 1:1, where “in the beginning” God created something. Now, in the beginning was already a something, the Word—Jesus Christ. The writer is telling us where to begin, not with an authority of Scripture, or a hermeneutical approach, or any doctrine or dogma, but with a person, a walking, talking, breathing person.

When we start here, then, we have the correct foundation for when we approach something like the authority of Scripture. We have the cornerstone, if you will (Matt 21:42). And this cornerstone has a very specific way of interpreting things. Let me point to just a few passages so that you see what I mean.

First, Luke 4 has an interesting story about Jesus’ initial teaching after his testing in the wilderness. After Jesus enters the synagogue, it eventually comes time for him to read, so he is given the scroll from the prophet Isaiah. He turns to what is now Isa 61:1–2, and reads, “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release from the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.” Then he stops, and rolls up the scroll—midsentence. What he “should have” read was the phrase “And the day of vengeance of our God.” But he doesn’t. And this is not taken in kind by the once eager listeners. In fact, his interpretive method nearly gets him tossed off a cliff, because for God’s vengeance to be omitted is for the enemies of Israel to not suffer what is promised them.

But the wrath of God of course had to befall those oppressing God’s people. This was a theological given.

But not according to Jesus.

One other theological given—based on clear Scriptural truths—was that those who were afflicted with illnesses were in such a state due to their sin. Thinking like this comes from places like Deut 28:15, 20–24, 59–61. But what Jesus teaches in John 9:3 is that things don’t work like this. Jesus, instead of likening blindness to sin, says that blindness is a part of life so that God can show God’s self to be a healer, a reconciler, a peacemaker. After all, God sends his rain on the righteous and the wicked, and blesses sinners and saints alike (Matt 5:45). He doesn’t, as the Proverb clearly states, reserve curses for the house of the wicked and blessings for the house of the righteous (Prov 3:33).

Not according to Jesus.

He was not bound to some presupposed authority of Scripture, no matter what his interlocutors thought and said. Sure, the Scriptures taught certain things about God as if they were objective truths, but Jesus often countered these with his own teachings. The Sermon on the Mount is notorious for this.

“You have heard that it was said . . . but I say unto you.”

Over and over he does this, where he replaces one set of teachings with new, progressive ones. And he can do this because he speaks on behalf of the Father. In fact, he only says and does what he sees the Father doing (John 5:19). And what he sees the Father doing is showing mercy to all (Luke 6:36).

That is why Jesus goes to the cross speaking the message of peace and grace (Luke 23:34). His Father is doing the same. In fact, his Father has always been doing that because his Father never changes. That is the theological reorientation Christ gave us, and it is also the reason I cannot believe, for one damn second, everything said about the Father in what we call the Bible is true. Or, quoting the prophet Jeremiah, “the lying pen of the scribes has surely distorted it” (Jer 8:8).

So if we are going to say Christians are to be followers of Jesus, then we need to follow his scriptural teachings. When we do, we will find that he had a specific and unique approach. And it was far from “God said it, I believe it, and that settles it.” Sorry, it’s not that easy folks. It actually takes diligent work to “rightly explain the word of truth” (2 Tim 2:15).

Peace.

The post REPOST: Jesus is the Reason the Bible is Not Innerant appeared first on All Set Free.

June 11, 2017

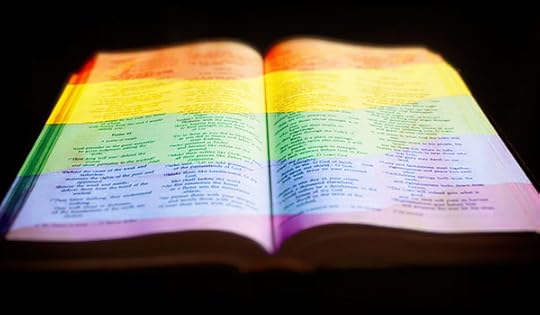

God Made Adam, Eve, and Steve

“Homosexuality is clearly condemned in the Bible. It undermines God’s created order where He made Adam and Eve, a man and a woman, to carry out his command to fill and subdue the earth (Genesis 1:28). Homosexuality cannot fulfill that mandate.”

— Matt Slick[1]

“Homosexuality is a result of the rejection of God (Rom 1:21–25). Gay marriage is the institutionalization of the rejection of God . . . The Bible teaches how Christians should respond to gay marriage. Don’t condone it; no matter how much we may love our friends and want to see them happy, real love is bringing them to a saving relationship with Jesus, not encouraging a sinful lifestyle.”

— Got Questions Ministries[2]

For the good part of thirty years, I held to the belief that homosexuality was a sin in the eyes of God. I was handed this view from my parents and the evangelical church at an age I cannot remember, and they had it handed to them from people and places of which I could only speculate. In all likelihood, they would tell you that their view came directly from the Bible, but I have since learned that really means their interpretation of the Bible.

After all, every single one of us, from the conservative pre-millennial dispensationalist to the liberal Anabaptist, has a hermeneutic. That is to say, everyone has a lens that they view the Bible through, whether they admit it or not. I’ll even take that one step further. Everyone has a lens that they view everything through, and so we can never escape our own subjectivity.

So, when it comes to a Christian’s attitude toward the LGBTQ community, we must keep this humbly in mind and not be cavalier about rejecting these folks, labeling them “sinners” based solely on their sexuality. To the contrary, it’s my strong contention that we actually have a duty to wholly and openly affirm this group.

That Pesky Bible

The strongest “Christian” case against affirming the LGBTQ community comes from the Bible. Duh, right? But let me be clear, even that case is thin in terms of how much weight is even given to the issue. Out of the over thirty-thousand verses in the Bible, you can count on two hands how many cover homosexuality. These are what are commonly known as the “clobber passages.”[3]

This raises the question: why does this topic cause such a stir within Christianity? One would think that Christians would be far more concerned with practicing compassion, kindness, humility, meekness, and patience (Col 3:12), loving thine enemies (Mark 11:25; Matt 5:44; Luke 6:27), helping the poor (Matt 19:21; Gal 2:10), the orphans and widows (Js 1:27), showing mercy and grace to the world (Matt 9:13; Luke 6:36; John 8:1–11), and living in the Spirit, whose fruit includes love, joy, peace, forbearance, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control (Gal 5:22–23). Isn’t this focus the overarching message of the Bible, particularly the New Testament?

Furthermore, one only needs a friendly reminder from the Apostle Paul as to why we should not point the accusatory finger at others: “All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Rom 3:23). So judge not, lest ye be judged (Matt 7:1). This much we should all agree on.

Now, with anything, context is crucial. As Jarrod Saul McKenna reminds us, “A text without a context is a con.”[4] If we miss this, we’ll risk missing everything, including how, as post-postmodern followers of Christ, we should approach the issue of homosexuality.

For instance, does it make any sense for a Christian to pluck Old Testament verses from their original historical and cultural context in order to clobber others, given that we are not under the Law but under Grace? It seems it would be a con to the very faith we proclaim!

Remember, if you add just a little bit of law to the Gospel, you have no Gospel at all (see Gal 1:6–7). If we are willing to clobber gay people with Leviticus 20:13, for example, are we also willing to be consistent when it comes to tattoos (Lev 19:28), eating bacon-wrapped shrimp (Lev 11:2–11), or wearing cotton/poly blends (Lev 19:19)? Do we stone women to death if they are found to have lost their virginity prior to being wed (Deut 22:13–21)? Do we execute children for cursing their parents (Exod 21:15)? Do we execute those who break the Sabbath (Exod 31:14)? Do we execute rape victims who don’t cry out loud enough while being sexually assaulted (Deut 22:23–24)? For the love of God, and I mean that in the sincerest sense, I hope not!

Shifting our focus onto the New Testament . . .

First, allow me to note that Jesus never once explicitly discusses “homosexuality” or “homosexual marriage.” Neither does Paul — not in the way we, in the twenty-first century, would. How could they? These were not classifications present during the first century. Here’s how the Oxford Classical Dictionary begins its entry on what homosexuality was and was not in classical antiquity:

“No Greek or Latin word corresponds to the modern term homosexuality, and ancient Mediterranean societies did not in practice treat homosexuality as a socially operative category of personal or public life. Sexual relations between persons of the same sex certainly did occur (they are widely attested in ancient sources), but they were not systematically distinguished or conceptualized as such, much less were they thought to represent a single, homogeneous phenomenon in contradistinction to sexual relations between persons of different sexes. That is because the ancients did not classify kinds of sexual desire or behavior according to the sameness or difference of the sexes of the persons who engaged in a sexual act; rather, they evaluated sexual acts according to the degree to which such acts either violated or conformed to norms of conduct deemed appropriate to individual sexual actors by reason of their gender, age, and social status … The application of “homosexuality” (and “heterosexuality”) in a substantive and normative sense to sexual expression in classical antiquity is not advised.”[5]

This is not to say that Paul did not admonish against “male prostitution and sodomy” (1 Cor 6:9; 1 Tim 1:10) or men engaging in “shameless acts with men” (Rom 1:27[6]), because he did. He also warned against a host of other immoral acts. Again, though, context is crucial.

As I’ve already noted, the concept of “homosexuality” was not present in Paul’s day, at least not in the modern way we view it. So, when Paul talks about unnatural acts between same-sex partners, it seems reasonable to think that he was speaking of something else entirely, something relevant to the issues he would have been facing as a first-century Christian. John Shore succinctly explains what that was:

“During the time in which the New Testament was written, the Roman conquerors of the region frequently and openly engaged in homosexual acts between themselves and boys. Such acts were also common between Roman men and their male slaves. These acts of non-consensual sex were considered normal and socially acceptable. They were, however, morally repulsive to Paul, as today they would be to everyone, gay and straight.”[7]

Adding insult to injury, because sexual relationships tended to be hierarchical — the penetrated being subservient to the penetrator — being on the receiving end of such a coercive relationship meant one would be stripped of a more desirable social status. Pardon the pun, but it was quite the double-whammy.

So, we must ask ourselves: Is this the phenomenon we are witnessing today? Are gay couples clamoring to have the right to coercively engage in sexual acts with unwilling partners? Are they hell-bent on garnering the legal right to participate in pederasty? Of course not! Using the writings of the Apostle Paul outside of this context in order to create any division is blatantly out of line.

As Christians, we should understand this, for it is Paul himself who plainly teaches: “There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male or female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus” (Gal 3:28, emphasis mine). In other words, for Paul, there were to be no dividing lines in the Church. In the first century, those lines included whether your table was kept kosher or not, whether you rested on the Sabbath or not, and whether, if male, some of your penis skin was cleaved off or not. Ouch!

But, in the twenty-first century, we could include the modern sociological dividing line of “gay” and “straight,” of which I’d have to guess Paul would emphatically rebuke as part of a false gospel that inevitably only leads to death (Gal 1:6, 2:19).[8] Admittedly, this is speculative, but given the context of Paul’s letters to the Romans and Galatians, it seems in line with his radically inclusive message.[9]

At the end of the day, what matters most — especially as Christians — is how we love. The writer of 1 John teaches us that “God is love” (1 John 4:8). Paul sums up the entire law in one sentence: “You shall love your neighbor as yourself” (Gal 5:14). Jesus himself teaches us that the greatest commandment is to love God and our neighbor as our self (Matt 22:36–40), and that in order to be his disciple, we must “have love for one another” (John 13:35). This obviously includes those who identify as LGBTQ!

To have love for them is not to condemn them because of their sexual preference. How can that be what it means to “love our neighbor as our self?” Do those who identify as heterosexual have any tacit knowledge of what it is like to be homosexual, for example?

So, do a thought experiment for me. Imagine you are a married, heterosexual person, and imagine your life up to this point altered in only one way, that instead of being partnered with someone of the opposite sex, you had partnered with someone of the same sex. All of your shared experiences are the same. All of your loving moments are the same. All of your times of joy, hope, even suffering, alike in every way save for one. How, then, would it be sinful if the only variable is that you are sharing these experiences with someone who shares your gender? How would you be violating what Jesus calls the greatest commandment: that we are to love God and neighbor?

Questions like these should give us great pause. Once upon a time they forced me to stop and reflect. And when I did, I could no longer stand justified in front of my God and my neighbor in telling any two consenting adults that they couldn’t share their lives together in the same way I was sharing my life with my lovely wife. So, I repented — that is, I changed my mind — and I started practicing how to love my LGBTQ family in the same way Christ Jesus loves them, beginning by openly welcoming them into the blessed community that has no dividing lines.

—————————

^ Slick, “What does the Bible say about homosexuality?” para. 2.

^ This quote can be found at https://www.compellingtruth.org/gay-marriage.html.

^ These verses include Genesis 19; Leviticus 18:22, 20:13; Romans 1:26–27; 1 Corinthians 6:9–10; 1 Timothy 1:9–10; Jude 1:7.

^ Quoted in Hardin, What the Facebook? , 232.

^ Hornblower and Spawforth, Oxford Classical Dictionary , 720.

^ I’ll note that if Pauline scholar Douglas Campbell is correct, Romans 1:26–27 is (ironically) a portion of the “false teachers’” argument Paul is dead set on rebuking, beginning in Romans 2:1. See Campbell’s The Deliverance of God: An Apocalyptic Rereading of Justification in Paul . Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2009.

^ Shore, Unfair , 9. I will also note that in Paul Among the People: The Apostle Reinterpreted and Reimagined in His Own Time , Sarah Ruden makes a strong case that whenever Paul discusses “homosexuality,” it is in the context that pederasty was running rampant in the Greco-Roman world.

^ I should note that the dividing line the Church has historically created over this issue has in fact led to mortal violence against the LGBTQ community being justified and even carried out by Christians. Take, for example, the 1999 murder of Gary Matson and Winfield Scott Mowder by the fundamentalist Williams brothers. Or, one year later, self-proclaimed “Christian soldier” Ronald Gay’s slaying of Danny Overstreet in Roanoke, Virginia.

^ This claim will no doubt be disputed. So, for a detailed look at how I read Paul’s letters, see the following: Galatians by J. Louis Martyn, and The Deliverance of God: An Apocalyptic Rereading of Justification in Paul by Douglas Campbell.

Image by Dan Wilkinson using photos from Pixabay.

The post God Made Adam, Eve, and Steve appeared first on All Set Free.

May 22, 2017

PART 3: PODCAST- Does The Evangelical View of the Cross Lead To Violence?

Awesome Part 3 of a conversation between Quoir authors Matthew Distefano, Keith Giles, and Jamal Jivanjee and about how Evangelical Christian views of the crucifixion relate to ideas about redemptive violence, and more.

Awesome Part 3 of a conversation between Quoir authors Matthew Distefano, Keith Giles, and Jamal Jivanjee and about how Evangelical Christian views of the crucifixion relate to ideas about redemptive violence, and more.

LISTEN TO PART 1 HERE

LISTEN TO PART 2 HERE

In this Podcast we talk about:

2:30 – Are we making claims for the Bible that it doesn’t even make for itself?

9:55 – What is a “Flat Bible” perspective vs a “Jesus-Centric” perspective?

14:50 – Why Jesus is superior to the Old Testament

18:40 – Has the Bible hindered Christianity?

26:00 – Is it appropriate to “chuck the Scripture”?

30:25 – Why context matters

31:50 – Why the Holy Spirit and community are essential to understanding Scripture

AND MORE!

LISTEN HERE:

LEARN MORE:

Suggested reading for further study

Who Wrote the Bible

Disarming Scripture

Healing the Gospel

What Is the Bible?

The Bible Tells Me So

Reading the Bible with Rene Girard

Jesus Driven Life

Stricken By God

ONLINE RESOURCES:

Video: The Monster God Debate [Start with part 2 here]

Video: The Beautiful Gospel by Brad Jersak

Podcast: The Robcast

WEBSITES:

Matthew: www.allsetfree.com

Keith: www.keithgiles.com

Jamal: www.jamaljivanjee.com

The post PART 3: PODCAST- Does The Evangelical View of the Cross Lead To Violence? appeared first on All Set Free.

PART 2: PODCAST- Does The Evangelical View of the Cross Lead To Violence?

Part 2 of a conversation between Quoir authors Keith Giles, Jamal Jivanjee and Matthew Distefano about how Evangelical Christian views of the crucifixion relate to ideas about redemptive violence, and more.

NOTE: I personally do not believe that the Penal Substitutionary Atonement Theory is what ultimately leads to violence.

Case in point: The early Christians did not embrace this PSA theory until John Calvin introduced it in the 1500s, and yet they did engage in a lot of violence against others, and even one another.

However: The PSA view does impact the way we see God and it does often provide justification for our own violence because, if God is violent can’t we be violent, too?

In this Podcast we talk about:

*Why did Jesus have to die on the cross?

*What is the mechanism that creates the necessity for Christ’s death?

*What is Mimetic Theory and how does it relate to the crucifixion?

*If Jesus wasn’t killed by His Father to satisfy His wrath and make it possible for us to be forgiven, then what was the cross all about?

*Why did Peter deny Jesus? Was this a special character flaw or are we all wired to go along with the crowd?

*Why is Jesus’ invitation to “Follow Me” crucial to our ingrained tendency to imitate the desire of others?

*What does it mean to say that “No one has ever seen God at any time [except Jesus]?”

AND MORE!

The post PART 2: PODCAST- Does The Evangelical View of the Cross Lead To Violence? appeared first on All Set Free.

May 16, 2017

Guest Post: Episode 47: Why The Evangelical Message About The Cross Leads To Violence: An Interview With Quoir Authors Keith Giles & Matthew Distefano

Although Jesus was the prince of peace and demonstrated love and non-violence throughout his life, evangelical Christians by and large have been the most consistent defenders of empire building, military action, and war. The reason for this anomaly among Christian behavior isn’t simply hypocrisy, however. This behavior could very well be rooted in the way we have been taught to see the cross and the nature of divine justice. Because humans are reflective beings, people will always reflect the God they perceive.

I recently sat down with fellow Quoir authors Matthew Distefano & Keith Giles to record a podcast about how the Penal Substitution Atonement theory (held by evangelicalism) actually produces violence.

At the 6:15 mark, we discuss the disconnect that penal substitution theory causes between our view of God as father, and our view of Jesus.

At the 10:00 mark, we discuss the fallacy of believing that sin separates us from God.

At the 14:30 mark, we discuss why Jesus actually was crucified.

At the 20:54 mark, we discuss why Penal Substitution Theory of the cross was not a view held by early Christians. Penal Substitution Theory, as commonly found in modern evangelical thinking, was largely a creation of John Calvin.

The resources mentioned in this conversation were:

If you haven’t subscribed to The Love Cast yet, would you consider doing that? Here is the link on iTunes where you can listen to this episode, subscribe, and write a review as well:

https://itunes.apple.com/us/podcast/the-love-cast-with-jamal/id1126696772

or you can listen directly here:

Source: Jamal Jivanjee https://www.jamaljivanjee.com

The post Guest Post: Episode 47: Why The Evangelical Message About The Cross Leads To Violence: An Interview With Quoir Authors Keith Giles & Matthew Distefano appeared first on All Set Free.

Matthew J. Distefano's Blog

- Matthew J. Distefano's profile

- 24 followers