Todd Richardson's Blog, page 3

September 13, 2015

Donald Trump and Hegel’s Dialectic

Everything turns into its opposite. That’s the paradoxical concept behind an established theme in political philosophy, one that, when you look for it, nevertheless manifests time and again in a diversity of unexpected circumstances. Aside from the novelty and entertainment factor, why would someone like Donald Trump experience a surge of popularity in the political arena? Perhaps it is because the currents of history are pulling for the emergence of an antithesis. The opposite of Obama.

The concept of change as the fundamental constant is as old as recorded philosophy. The ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus is credited with the aphorism that you can never stand in the same stream twice, the point being that the flow of the current constantly alters the substance around any fixed point. Then, about two hundred years ago, in the grand tradition of eccentric German philosophers with ideas that sound crazy but resonate somehow with a ring of truth, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel compounded that perception with an added twist: not only is everything in a state of change, but it is turning into its opposite.

There is more to what came to be known as Hegel’s dialectic. When something becomes its opposite, that, too, is a new premise for continued change. When the second status transforms into its own opposite, however, it does not revert to the original condition. Instead, the opposite of the opposite is a combination of its two predecessors. Thesis, antithesis, synthesis. Sounds unlikely, but examples are not hard to find. Don’t we all start out as miniature creations of our parents, then tend to rebel against their value systems in search of our own identities, and finally settle into a life that mirrors our origins while retaining allegiance to the perspectives formed in young adulthood?

You can see it, too, in the swings of American politics, particularly presidential politics. Take the two President Bushes. George H.W., the elder, was a model exponent of orthodox Republican east coast establishment, an upright plutocrat embodying careful conservative principles. Bill Clinton, then, was the opposite: a brainy southern Democrat with half-lidded eyes who was not believed when he said he didn’t inhale and did not have sexual relations with that particular woman. It’s not hard to describe George W. as a combination of the two. His father’s son, yes, and the chosen heir of the Republican establishment, but a Southerner with a history of questionable lapses, a swagger with an air of rehab about it.

So what about Barack Obama? Not so natural, true, to cast as the synthesis of his two predecessors, possibly a return to Democratic priorities with the policy wonk orientation of Bush-era neocons. But assume he’s a reset, a new thesis. What would his antithesis look like?

Instead of an African American of dignified bearing, a white guy who delights in carnival spectacle and shock pronouncements. A conservative haircut of curly graying black, versus not. From a need to explain in carefully constructed sentences, a disdain for details and a cursory dismissal of other views as those of losers. Rather than policy positions built from studied analysis, a cult of personality that is all about attitude.

Set aside appearance and style, consider the contrasting values and positions, and the premise holds true. Obama is oriented on improving the prospects of the disenfranchised, cultivating support among women and minorities; Trump is the unapologetic voice of wealth and privilege, with naked hostility toward Latinos and a preference for women in tiaras. Obama’s foreign policy focuses on diplomacy and an effort to understand the perspective of others; Trump’s approach is that foreign countries will bend to his will or else. Obama sympathizes with the undocumented seeking a better life in the United States; Trump sees illegals as a detestable threat to Americans like himself. Don’t forget that when a rumor arose that Obama might not be a naturalized citizen, it was Trump who placed a bounty on the man’s birth certificate.

The pull of Hegel’s dialectic does not mean, of course, that Trump will ride a contrarian wave all the way to the White House. Nate Silver is still assuring us that is not going to happen. But it does help explain the Trump phenomenon, in a world where a presence of one polarity tends to give rise to another of opposite charge. And if Nate should turn out to be wrong, and the antithesis wins the election, that begs the disturbing question. What in the world would a synthesis of Obama and Trump look like?

September 7, 2015

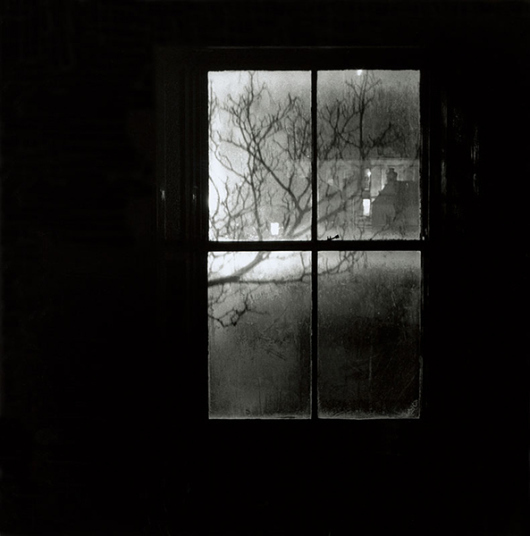

Windows and Mirrors

You get up in the night to go to the bathroom. There’s a window to the backyard. Do you feel a bit nervous about peering out? Or perhaps you pass a mirror in a dark hallway. Do you have a sense of dread as you steal a glance?

You get up in the night to go to the bathroom. There’s a window to the backyard. Do you feel a bit nervous about peering out? Or perhaps you pass a mirror in a dark hallway. Do you have a sense of dread as you steal a glance?

There is something undeniably creepy about windows and mirrors, as common and mundane a feature of our everyday lives as they are. They are a reliable staple for cheap jolts in horror movies, the unexpected figure or sudden movement, he’s right there!, it’s right behind you!, that sort of thing. As a device, particularly in a visual horror medium, it is a handy and effective mechanism for a quick scare, but that doesn’t really explain why mirrors and windows are disquieting even when you’re not watching a horror movie and are not expecting your life to turn into one.

The lurking terror hidden in windows and mirrors, I’d say, is the same thing that gives me faith in the fundamental capacity of humans to scare themselves. It is not what you see, it is the irrational fear of what you might see.

Take a flat, smooth plane and position it across your line of sight. Transparent or reflective, either way, what you see is no more or less than what lies beyond or appears before it. And yet, the interposition of a solid, invisible medium conveys a subtle impression on the mind. You are seeing through something, watching what is on the other side of a divide. It appears to be the world you know, but what if there is something different? What if there is something on the other side looking back?

Windows can induce fright from the inside looking out or from the outside looking in. If you’re inside, secure in your shelter, a face at the window or a shadow across the shade triggers the fear of intrusion, assault, invasion. It’s not a polite knock on the door or the ringing of a bell, it’s the sudden appearance of an outside presence with designs on what’s within. The classic example is the traditional vampire with hypnotic eyes, unable to enter without an invitation. If you’re outside, on the other hand, and you think the house is empty, a figure at a window can be equally unsettling. Or if you see a shadow or movement at a window and realize someone’s been watching you unawares.

Mirrors are worse. They seem to carry latent capacity to reveal more than what you would see looking about inside the room. What if your own face is distorted or deformed, or you see madness in your eyes, or a creeping ghastly pallor? What if an invisible presence is in the room, right next to you, but can only be glimpsed in the mirror? It is not the mirror itself that holds the hidden terrors, or the reflection world you see when before it, but the dreadful knowledge that whatever you encounter when you lift your eyes to the silvery expanse is an image of something that subsists in your reality. It will remain with you even if you press your eyes tightly shut, hold your hands over your ears and scream loudly.

Ultimately, the psychological appeal of mirrors and windows as fascinating sources of nervous dread lies in the fear of our own imagination. We picture in our minds a parade of horrors, ghosts, menacing figures, all manner of twisted visions, and we require nerve to face the open curtain and the possibility that the demons of our psyches will be revealed. How sublime are human beings, to attain the depth of consciousness and expansive scope of creative vision necessary to conjure in the mind a possible world in deviation from that being conveyed by immediate sense perceptions, and yet still wild and frantic enough to experience a surge of fear at the prospect of encountering the irrational horrors of our own fevered imaginations?

Perhaps it’s a survival instinct, just in case there really is a werewolf outside the window or a smiling ghost behind you in the mirror.

August 31, 2015

Victorian sensibilities in modern horror

Have you ever noticed the dominance of the nineteenth century as the setting of choice for horror stories? The era fills my earliest

Have you ever noticed the dominance of the nineteenth century as the setting of choice for horror stories? The era fills my earliest

horror memories. I recall Barnabas Collins as a contemporary vampire, but he cultivated the air of a gentleman from the prior century, with cape and cane. Uncle Creepy and Cousin Eerie, hosts of the classic Warren Publications horror magazines, dressed like Victorian undertakers. Even Heebie, the skeletal sidekick of Milton the Monster in the 60s Saturday morning cartoon, wore a cape and top hat. And when a cartoon character embodies a recognizable stock look, it bespeaks an archetype.

So why is that bygone era such fertile soil for tales of horror that resonate with modern audiences? Several reasons, I think.

Queen Victoria reigned over the British Empire from 1837 until 1901, presiding atop the dominant world civilization of the time and giving a name to an era, conveniently dying near the turn of the century to cement her association with the 1800s. One reason the Victorian era is preeminent in tales of horror, of course, is that it spanned a golden age of primarily Gothic writing that ushered in the modern concept of the horror story.

Ask someone the names of the two most famous monsters of all time, and chances are the response of anyone who isn’t trying to frustrate the exercise will be Dracula and Frankenstein. The correct term, of course, is Frankenstein’s monster, as the Doctor himself was only a monster in the psychological sense. But Mary Shelly’s Modern Prometheus was published in 1818, only one year before Queen Victoria’s birth. At the other end of her life, Bram Stoker published Dracula in 1897. All the film adaptations and other derivative works inspired by those two characters alone account for a healthy percentage of the horror genre since that time.

In the United States, moreover, the nineteenth century was the era of Edgar Allan Poe, whose sense of horror has similarly haunted the imaginations of storytellers ever since. He began his writing career in Baltimore in the 1830s, as Queen Victoria was rising to power, and unlike her died young in 1849. Again, the movie versions of Poe stories alone skew the statistics in favor of nineteenth century horror.

There are many other classic creations from that era – Jekyll and Hyde, Dorian Gray, the governess in Turn of the Screw – all late 1800s, all drawing on the manners and tastes of the time, and all exercising continuing influence on the chills of modern audiences. Gothic horror crested in the nineteenth century. Even Charles Dickens had a bent for ghost stories, of which A Christmas Carol is but the most famous; truth to tell, though, the Dickens style of haunted stories was not all that frightening.

But there is more to it, I believe, than the rich tradition of source material that emerged from that time period. The late 1800s especially evoke associations with present day circumstances. Like today, it was the dawn of a modern age, when technological advances transformed society and expanded the perception of possibility. It was a time when the harsh urban realities of the Industrial Revolution clashed with the genteel culture of past generations, when spiritualism caught fire amidst the strictures and dogma of conventional religion, when the acceleration of progress was itself a source of alarm and trepidation. Even the fashion sense had echoes in the mod look of later days, as Victorian gentlemen experimented with long hair, ornamental whiskers and sharp clothes. We react to the nineteenth century milieu because we can relate.

But it goes deeper than that. Why are 1800s photographs so creepy? The subjects are all dead now, for one thing, but more than that the solemn faces, the grooming and clothes, the tint and shadows, the formality of presentation, somehow the people look like they were already ghosts when the picture was taken, like they were conscious at the time of being visages from beyond the grave for future generations.

The character of the Victorian era, furthermore, is recalled as one of strict propriety, prim and correct, suppressing the base and the vulgar, and hence ripe for the disorienting horror of violence, chaos and passion. When we experience horror through Victorian eyes, we see the descent into madness and repulsion from a higher plateau of civilized order and mannered restraint.

The faces of the nineteenth century, then, convey the enlightenment of modern society, the shades of the past, and a lost sense of moral rectitude. They are at once ourselves, ghosts, and icons of refined sensibilities, just waiting to be victimized by some hideous and unnatural fiend.