David Tickner's Blog, page 10

October 26, 2023

Cool

When we talk of someone being cool, do we mean that they are feeling a bit chilly standing outside on a blustery autumn day without a warm sweater?

When we talk of someone being cool, do we mean that they are feeling a bit chilly standing outside on a blustery autumn day without a warm sweater?Cool, meaning not warm or not too cold, has its origins in Old English col, Proto-Germanic koluz, and the Proto-Indo-European root gel (cold, to freeze).

In the 14th century, cool also meant manifesting coldness, apathy, or dislike. Even today, to be ‘cool to the idea’ means to be unconvinced.

In the 14th century, the poet Geoffrey Chaucer used cool to describe someone’s wit. In the late 16th century, in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Act 5, Scene 1), Shakespeare wrote, “Lovers and madmen have such seething brains, such shaping fantasies, that apprehend more than cool reason ever comprehends.”

In the early 1700s, a cool amount of money meant a very large amount of money. Cool-headed, meaning not easily excited or confused, is from 1742. Cool, meaning calmly audacious, is from the early 1900s.

In the 1930s, cool was a casual expression used to mean something intensely good. “The slang use of cool to mean fashionable is by 1933, originally African-American vernacular; its modern use as a general term of approval is from the late 1940s, probably via bop talk and originally in reference to a style of jazz” (Online Etymological Dictionary).

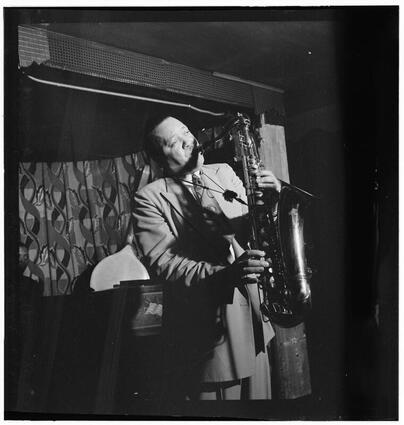

“The jazz saxophonist Lester Young was the first to say “I’m cool” in reference to a state of mind: it meant he felt relaxed, safe, and laid-back in the environment. Young’s use of the phrase also encoded a certain protest during the era of racial segregation: “I’m cool” meant “I’m keeping it together—in mind and spirit—against oppressive social forces.” Cool came into common use among Black Americans in the 1930s as a term for calming someone down from emotional stress” (The National World War II Museum).

Marc Bain, writing in Quartz in 2020, states, “Where for most of its history cool was characterized by a reserved dispassion, to be cool now often includes being informed and concerned about what’s happening in the world—or, at minimum, looking like you do.”

Sometimes when I am reviewing the key points when concluding a course on effective instruction, I will ask participants, tongue in cheek, “Who would like to be seen by their learners as a ‘cool’ instructor?” I pause. There’s silence—no one ever admits that they’d like to be a cool instructor. It’s as if this feels uncomfortable—is it cool to say you’re cool?

After the brief pause and a wink, I say, “If you want to be a cool instructor, put a little ICE into your work!” And the group groans. Why? Because during the course, when discussing the characteristics of effective instruction or of an effective instructor, three items that most often appeared on lists were Interaction / Involvement, Communication / Clarity, and Enthusiasm. In short, I C E.

Image: Lester Young: Library of Congress Public Domain Archive.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2014/julyaugust/feature/how-did-cool-become-such-big-deal

https://qz.com/1896190/what-does-cool-mean-in-2020

https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/origins-of-cool-in-post-wwii-america

Published on October 26, 2023 21:07

October 22, 2023

Mazda

The word mazda has its origins in Proto-Indo-European (PIE) mens-dhe (to set the mind) from the PIE roots men-(1) (to think) + dhe- (to set, to put). The word mazda (wise) is first seen in Avestan, an ancient Persian language.

The word mazda has its origins in Proto-Indo-European (PIE) mens-dhe (to set the mind) from the PIE roots men-(1) (to think) + dhe- (to set, to put). The word mazda (wise) is first seen in Avestan, an ancient Persian language.Ahura Mazda is the name of the God of Zoroastrianism, the religion of ancient Persia which began about three or four thousand years ago. Avestan ahura = spirit, lord + mazda = wise combine to create the name which means the spirit or lord of wisdom, intelligence, and harmony.

Wikipedia suggests that in Zoroastrianism can be seen many concepts that later emerged in other religious and philosophic systems “including the Abrahamic religions and Gnosticism, Northern Buddhism, and Greek philosophy.”

So, what does all this have to do with Mazda vehicles, you might ask.

In 1931, the Japanese company, Toyo Kogyo, launched its first vehicle, the ‘Mazda-go’, a tricycle truck (illustrated above). One of the founders of the company, Jujiro Matsuda (1875 – 1952), chose the name Mazda for two reasons.

First, according to a publication of the Mazda company, the leaders of the Toyo Kogyo Company were looking for a name that represented “a symbol of the beginning of the East and the West civilization [and] also as a symbol of the automotive civilization and culture. Striving to make a contribution to the world peace and to be a light in the automotive industry, Toyo Kogyo was renamed Mazda Motor Corporation” (www.mazda.com).

A second reason is that the Japanese pronunciation of Matsuda sounds very much like the pronunciation of Mazda.

I wrote this while waiting at a Mazda dealership while some maintenance work was being done on my car.

Image: Mazda-go "DA type" (introduced in 1931). Mazda Virtual Museum: 100 Years of History in Pictures.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

https://www.mazda.com/en/innovation/mazda-stories/mazda/behind/

https://www2.mazda.com/en/100th/virtual_museum/gallery/gallery011.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zoroastrianism

Published on October 22, 2023 20:33

October 19, 2023

Mojo

The other day I ran into a woman from an art group that we attend.

The other day I ran into a woman from an art group that we attend.“Haven’t seen you for a while,” I said.

“No,” she replied, “I seem to have lost my mojo.”

Her comment made me wonder about the word mojo.

The Online Etymological Dictionary suggests that the origins of the word mojo are probably related to Gullah moco (witchcraft) and Fula moco’o (medicine man). Mojo, meaning magic, first appeared in the southeastern United States in the 1920s.

“The Gullah are an African American ethnic group who predominantly live in the Lowcountry region of the U.S. states of South Carolina, North Carolina, Georgia, and Florida within the coastal plain and the Sea Islands” (Wikipedia).

Fula, the language of the Fulani people, is spoken as a first language by about ten million people and is widely used in West Africa (Wikipedia).

Wikipedia defines a mojo as an amulet consisting of a flannel bag containing one or more magical items—a “prayer in a bag”—that is part of the African-American spiritual practice called Hoodoo (not to be confused with Voodoo). Wikipedia defines hoodoo as “a set of spiritual practices, traditions, and beliefs that were created by enslaved African Americans in the southern United States from various traditional African spiritualities, Christianity, and elements of indigenous botanical knowledge.”

By the 1930s, mojo was also an underworld name for any of the poisonous habit-forming narcotics.

More recently mojo is used to mean “exceptional ability, good luck, success” (Dictionary.com).

Image: The photo caption includes, “note the mojo around the neck of the center figure.”

New York Public Library Public Domain Collections.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

https://www.dictionary.com/e/word-of-the-day/mojo-2021-10-18/

Published on October 19, 2023 17:03

Wow!

Wow, first seen in Scottish in the 1510s, is a natural expression of amazement. When you are amazed, your mouth drops open and almost automatically makes a ‘wow’ sound as you exhale. The word was very popular in the early 1900s and again in the 1960s (Online Etymological Dictionary).

Wow, first seen in Scottish in the 1510s, is a natural expression of amazement. When you are amazed, your mouth drops open and almost automatically makes a ‘wow’ sound as you exhale. The word was very popular in the early 1900s and again in the 1960s (Online Etymological Dictionary).The noun ‘wow’ (an unqualified success) is from 1920. The verb ‘to wow’ (to overwhelm with delight or amazement) is from 1924.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on October 19, 2023 17:00

October 12, 2023

Zero

Do you ever wonder why the numbers we use are called Arabic numbers? The short answer is that the Arabic numbering system gradually replaced the Roman numeral system in Western Europe during the early medieval period. Can you imagine trying to multiply XXII by XXXVII?

Do you ever wonder why the numbers we use are called Arabic numbers? The short answer is that the Arabic numbering system gradually replaced the Roman numeral system in Western Europe during the early medieval period. Can you imagine trying to multiply XXII by XXXVII?Let’s focus on the zero.

Before the word zero appeared in English, the word cipher, from the late 14th century, was used to name the arithmetical symbol ‘0’. Cipher came to English from Latin cifra, Arabic sifr (empty, nothing), and Sanskrit sunya-s (empty).

The word zero did not appear in English until around 1600. At that time, a zero was “a figure which stands for naught [nothing] in the Arabic notation” and which referred to “the absence of all quantity considered as quantity” (Online Etymological Dictionary). Zero came to English from French zero, Italian zero, Latin zephirum, and Arabic cifr—all from Sanskrit sunya-m meaning an empty place, a desert, nothing, naught (Old English na (no) + wiht (thing) = nawiht).

Seemingly, when zero first appeared in English it was not a number but a quality. If zero means ‘nothing’, how did zero become a number meaning something? Is zero even a ‘number’? At this point, we are quickly sliding into philosophy rather than etymology.

-o-

A bit of background. Just as writing evolved in different ways in different places (e.g., multiple combinations of Chinese characters or the 26-letter A-Z alphabet) so also did numbers evolve in different ways in different places.

In early mathematics, zero was used simply as a placeholder; e.g., a 0 determined whether a number is 12 or 102. You can’t do this with Roman numerals; e.g., Roman numeral ‘V’ only ever means 5 whereas the figure 5 has a different value if it is in the number 514 or the number 145.

As far as is known, this positional concept of zero emerged in only four places: in Babylon, around 2000 BCE, in China around the beginning of the 1st century CE, and between the 4th and 9th centuries CE in both India and the Mayan civilization of Central America.

To quote at length from the Online Etymological Dictionary,

“But the next step, the true miracle moment, is to realize that [using zero as a] ‘symbol for nothing’ means that [zero] is not just a place-holder, but an actual number: that ‘empty’ and ‘nothing’ are one … that's when the door blows open and the light blazes forth and numbers come alive. Without that, there's no modern mathematics, no algebra, no modern science.

As far as we know, that has only happened once in human history, somewhere in India, in the intellectual flowering under the Gupta Dynasty, about the 6th century C.E. There was no ‘miracle moment,’ of course. It was a long, slow process.

Some [Western] authorities, however, put up strong resistance to the [notion] of the Indian origin of modern mathematics. At first, they were mired in the same religion-based worldview that … the number system simply had to be Hebrew in origin, because nothing else would comport with the Bible (so they thought). Later, [this] resistance took refuge in unwillingness to concede cultural superiority to non-Western civilizations.

Speculation about a Greek origin of the ten ‘Arabic numerals’ goes back to the 16th century in Europe. But before that, there are many sources in Europe and the pre-Islamic Levant that frankly attribute them to India. The earliest depiction of [Arabic numerals] in English, The Crafte of Nombrynge (c.1350), correctly identifies them as “teen figurys of Inde."

I suspect that the Western European merchants and bankers of the time had a great deal of influence in the adoption of the Arabic number system.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

A brief history of zero. https://www.etymonline.com/columns/post/zero?old=true

https://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/listen-the-greatest-numbers-of-all-time-1.6978649

Published on October 12, 2023 16:59

October 1, 2023

Virtual Reality (VR)

The words virtue and virtual have their origins in the PIE root wi-ro (man), Latin vir (man), Latin virtus (excellence, potency, efficacy; manliness, manhood), and Latin virtutem (moral strength, high character, goodness; manliness; valor, bravery, courage in war; excellence, worth). Virtue is made manifest in the external actions of a person.

The words virtue and virtual have their origins in the PIE root wi-ro (man), Latin vir (man), Latin virtus (excellence, potency, efficacy; manliness, manhood), and Latin virtutem (moral strength, high character, goodness; manliness; valor, bravery, courage in war; excellence, worth). Virtue is made manifest in the external actions of a person.The word virtual (i.e., influencing by physical virtues or capabilities and effective with respect to inherent natural qualities) came to English in the late 14th century from Latin vitualis and virtus.

Virtual, meaning something capable of producing a certain non-physical effect, is from the early 15th century. Virtual, as something which produces a certain essence or effect that is not actual or in fact, is from the mid-15th century. For example, certain objects (e.g., old photos, family heirlooms) can evoke strong mental associations just as a touch can evoke a feeling or a smell can evoke a memory. In short, something that is virtual can produce a strong (or virtual) effect.

In the 1950s, Susanne Langer described art as a form of ‘virtual experience’; that is, the artist creates artworks or ‘virtual worlds’ which can evoke such strong effects in the viewer.

Similarly, virtual in the computer sense of something not physically existing but made to appear or to be represented by software is from 1959.

Anecdotally, and somewhat surprisingly, Nora Roberts (writing as J.D. Robb) mentioned the use of Virtual Reality (VR) devices in her 1995(!) crime novel Naked in Death.

Virtual Reality (VR) is a term for digital learning environments in which learners engage in interactions with simulated objects or people (e.g., avatars) within computer-generated representations of either real life or imaginary realities; e.g., realistic simulations of a work-related experience, a visit to a museum, gaming. Through the use of various devices, notably VR headsets and goggles, learners are immersed in a digital world in which they navigate and act.

The two aspects of reality in such VR experiences are, one, the reality (and awareness) of the simulation or other activity in which one is immersed and, two, the reality (and awareness) of wearing the headset or other gear. Both realities are experienced simultaneously.

Laia Tremosa describes the “virtuality continuum; i.e., the full spectrum of possibilities between the entirely physical world—the ‘real’ or ‘actual’ environment—and the fully digital world or virtual environment. In a continuum, adjacent parts are almost indistinguishable [e.g., augmented or extended reality: AR or XR] but extremes are very different.”

Using such digital devices to walk virtually in a park or to virtually troubleshoot a problem in a truck engine are not the same experiences as actually visiting a park or working on the shop floor. However, as David Chalmers states, both actual and virtual (or other artificial) experiences are real—they are just different.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Chalmers, D.J. (2022). Reality+: Virtual worlds and the problems of philosophy. New York: Norton.

Tremosa, L. (2023, July?). Beyond AR vs VR: What is the difference between AR vs MR vs VR vs XR? https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/beyond-ar-vs-vr-what-is-the-difference-between-ar-vs-mr-vs-vr-vs-xr

Susanne Langer. (2023, Sept 23). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Susanne_Langer

Published on October 01, 2023 19:42

September 30, 2023

Reconciliation

In Canada, September 30th marks the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation (also known as Orange Shirt Day), a statutory federal holiday established to recognize the legacy of the Canadian Indian residential school system.

In Canada, September 30th marks the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation (also known as Orange Shirt Day), a statutory federal holiday established to recognize the legacy of the Canadian Indian residential school system.Surprisingly, perhaps, the word reconciliation has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root kele, meaning to shout. This seems odd. However, the etymology tells us that the ancient connotation of such shouting is in the context of ‘a calling together’; for example, “Hey people! We need to get together and talk about this…”

PIE kele (to shout, to call) + the Latin prefix com (together, together with) = Latin concilium (a meeting, a gathering of people) and conciliare (to bring together, to unite in feeling, to make friendly).

The verb ‘to reconcile’ (to restore in union and friendship after estrangement or variance) came to English in the mid-14th century from 12th century Old French reconcilier and Latin reconciliare (to bring together again; to regain; to win over again).

The noun reconciliation (renewal of friendship after disagreement; action of reaching accord with an adversary or one estranged) is also from the mid-14th century.

The verb ‘to reconcile’ is also the source of the verb ‘to conciliate’ (to overcome distrust or hostility) which came to English in the 1540s.

Image: https://www.concordia.ca/events/orange-shirt-day.html

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation / University of Manitoba

http://www.trc.ca/about-us/trc-findings.html

Published on September 30, 2023 08:51

September 24, 2023

So long

Do you ever wonder why we say, “So long”, when we are taking leave of someone? Where does the phrase ‘so long’ come from? In brief, no one knows.

Do you ever wonder why we say, “So long”, when we are taking leave of someone? Where does the phrase ‘so long’ come from? In brief, no one knows.The term ‘so long’ first appears in the 19th century and was widely used in the United States, Britain, and Canada, particularly among lower classes (Online Etymological Dictionary).

Numerous suggestions for the origins have been made. For example, the German idiom adieu so lange (farewell, while we’re apart). Or Hebrew shalom. Or Norwegian adjo sa lenge (bye so long). Or Swedish sa lange (for now). Or from garbled Arabic words in sailors’ slang. However, the Online Etymological Dictionary suggests that many etymological sources lean toward a Germanic origin.

However, the noted etymologist, Anatoly Liberman, states, “…there is no consensus on the origin of ‘so long’. Yet, despite all doubts, the idea that we are dealing with a sailor’s phrase seems right. If this idea is acceptable, ‘so long’ is, most probably, a garbled version of some foreign word.”

The Cambridge Dictionary suggests that we can use “So long” as a less formal way of saying “Goodbye” so long as we are not sure of when we’re returning. That is, we might say, “So long, catch up with you later” rather than “Goodbye, see you tomorrow.”

Anyway, so long for now.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

https://blog.oup.com/2018/03/the-origin-of-so-long/

https://dictionary.cambridge.org/grammar/british-grammar/as-long-as-and-so-long-as

Published on September 24, 2023 19:52

September 22, 2023

Debt, Debit

The words debt and debit both have origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root ghebh (to give, to receive; to hold either in offering or taking) and Latin debitum (something owed).

The words debt and debit both have origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root ghebh (to give, to receive; to hold either in offering or taking) and Latin debitum (something owed).Debt

Latin debitum = de (away) + habere (to have); i.e., not to have something or to keep something away from someone.

The word dette (anything owed or due from one person to another, a liability or obligation to pay or render something to another), from Old French dete and Latin debitum, came to English around 1300. Later in the Middle Ages, the wordsmiths of the day added the ‘b’ to dette in order to retain the word’s original Latin roots. Debt, meaning the state of being under obligation to make a payment, is from the mid-14th century.

Also in the mid-14th century, the phrase ‘debt of the body’ referred to that which spouses owe to each other; i.e., sexual intercourse. I am tempted to ask who was keeping track of who owes what to whom? But I won’t. I was also wondering if it could be said that if someone was a little behind in their debt payments that their account would be in arrears? Sorry… couldn’t resist.

Debit

The word debit (something that is owed, a debt), from Old French debet and Latin debitum, came to English in the mid-15th century. Debit, as a bookkeeping term meaning an entry into an account of a sum of money owing, is from 1776. The verb ‘to debit’ (to charge with a debt) is from the 1680s and ‘to debit’ (to enter on the debit side of an account) is from1865. Debit card is from 1975.

In brief

What is the difference between a debt and a debit? A debt is an amount of money owed to an individual or institution. A debit is an amount of money leaving your account to purchase something.

Bookkeeper, by the way, is the only English word with three consecutive double letters. But I digress.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/1988/economics/what-is-the-difference-between-a-debit-and-a-debt

Published on September 22, 2023 08:19

September 17, 2023

Bleach

The other day I saw the word bleach on a shopping list. I stopped and looked at the word as if I had just seen a colorful stone on a gravel path. Where does the word bleach come from, I wondered.

The other day I saw the word bleach on a shopping list. I stopped and looked at the word as if I had just seen a colorful stone on a gravel path. Where does the word bleach come from, I wondered.The verb ‘to bleach’ has its origins in the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root bhel-(1) (to shine, flash, burn; shining white) and Proto-Germanic blaikjan (to make white), the source of words such as Old Saxon blek, Dutch bleek, German bleich, Old Norse bleikja, and Old English blaecan (all meaning to make white by removing color, to whiten).

Interestingly, the words bleach and black are siblings of the PIE bhel-(1) family, “perhaps because both black and white are colorless, or because both are associated in different ways with burning” (Online Etymological Dictionary). The origins of the word black form yet another interesting word story.

The noun bleach first appears in the 18th century. Bleach, as a chemical bleaching agent, is from 1881. The Old English noun blaece meant leprosy, perhaps related to changes in skin color resembling the burning or whitening of the skin.

The next time you use bleach to perform some ordinary household task, consider that the word bleach has come to us more or less unchanged through thousands of years of ordinary household use.

Reference: Online Etymological Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/

Published on September 17, 2023 20:39