David J. Bookbinder's Blog, page 5

November 29, 2017

How the light gets through

Nobody sees a flower – really – it is so small it takes time – we haven’t time – and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time.

– Georgia O’Keeffe

In August, 2003, I attended a five-day, mostly silent retreat with Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh (and 900 others). I thought of it as “Buddhist boot camp.” We awoke at 5:30 a.m., exercised with Thich Nhat Hanh or one of his monks or nuns, and spent the day meditating, listening to dharma talks, participating in discussions of Buddhist thought, and in general immersing ourselves in Buddhist practice.

At that time the older brother I never had, my close friend Robert, was in a bad way. Like me, he had nearly died about ten years before, and like me had struggled with his infirmities. For a long time, he did well, but in recent months he’d fallen into a deep depression. I was also battling depression at that time and it strained my limited emotional resources to be with Robert. In the best of times, our relationship was 70% Robert, 30% David. Lately, it had been 99% Robert, and I’d been avoiding him. But as I drove past his apartment in Gloucester on the way back from the retreat, I realized I felt healed. I could see Robert again.

When I arrived home, there was a message on my answering machine from Robert’s ex-wife. I called her. “I hope you’re not going to tell me what I think you’re going to tell me,” I said. “I am,” she said. “Robert committed suicide two weeks ago.”

The next day, I came down with a high fever and a severe cough. For 10 days, I was in a delirium of what turned out to be pneumonia. When I’d recovered enough to venture outside, I took a walk on Good Harbor beach. As I crested the first dune, I was overcome by the sensation that I, as well as the air, the surf, the sand, the sky, and the people and dogs playing on the beach, were all just matter and energy. Everything was a continuum, the boundary between myself and the sand and the air vague and indistinct, as if we were all images in a Pointillist painting. For the first time in my life, I not only knew but felt and saw that I was part of everything and so was everything else. I was more aware than I have ever been.

After I got home, I remembered how Thich Nhat Hanh had described the beauty of the retreat’s host campus, which to me had seemed pleasant enough but not extraordinary in any way. This, I now thought, is how Thich Nhat Hanh sees. I was suddenly hungry and eagerly ate nearly a quart of vanilla yogurt, which tasted better than the best vanilla ice cream I’d ever had. I remembered Thich Nhat Hanh telling us to chew our food until it was liquid so we could enjoy the delicate flavors of carrots and zucchini. This, I thought, is how Thich Nhat Hanh tastes.

Over the next few months, I had shorter but equally intense experiences of heightened awareness. A baseball field I crossed on the way home from the commuter train shimmered with beauty. My heart resonated so strongly with a therapy client’s feelings that I thought, at first, the emotions were my own. With regular meditation, this awareness waxed. When I slackened my meditation practice, it waned.

Awareness cuts through the tangled thought processes of the rational mind and the pull of emotion by placing us in our bodies, in direct contact with our environment, right now. As a therapist, and in my own personal work, becoming aware has been a slow and sometimes faltering process, but it always yields a shift toward conscious choices rather than acting reflexively from unconscious attitudes and beliefs – of responding, rather than simply reacting.

There are many tools to increase awareness. They all facilitate connection between a more aware self and the world as it is, not as we hope it is or fear it will become. The tools I use most to help me become more aware include mindfulness and meditation practices from Buddhism, attunement practices from Focusing, perception-based techniques from Gestalt Therapy, and pattern recognition and interruption strategies from Spell Psychology. But photography, writing, and even motorcycling have also helped me to become more aware. Each of us finds our own path to awareness.

By clarifying our sense of ourselves, the world outside us, and our connections to it, awareness enables us to know who we are and what we need. As it increases, we find ourselves intuitively saying “yes” when we mean yes and “no” when we mean no. Awareness, regardless of the method by which it is achieved, is an essential component of awakening from the many-faceted sleep of illusion to the full and genuine lives that are our true heritage.

Books:

Paths to Wholeness: Fifty-Two Flower Mandalas

52 (more) Flower Mandalas: An Adult Coloring Book for Inspiration and Stress Relief

52 Flower Mandalas: An Adult Coloring Book for Inspiration and Stress Relief

Paths to Wholeness: Selections (free eBook)

… and coming soon, The Art of Balance: Staying Sane in an Insane World

Copyright 2017, David J. Bookbinder

http://phototransformations.com

http://www.transformationspress.org

http://www.davidbookbinder.com

http://www.flowermandalas.org

November 23, 2017

Looking for a few good … opinions!(And offering a giveaway)

Thanks for your thoughts on The Art of Balance title earlier this fall. The book is moving through its early pre-release stages. I’m busily getting feedback, making revisions, building a new website for Transformations Press, and investigating ways to network.

But before I can get much further, I need a good cover!

1. The Scene:

You’re feeling stressed and you’re scrolling through books on stress relief in the hope of finding a solution to your woes. You come upon one of these four book covers:

2. The Survey:

Click here to tell me, in this one-question survey, which cover you’d be most likely to click (and, optionally, why you were drawn to that particular one). Your opinions on the survey (and any additional thoughts) will be helpful in shaping the future of this book.

3. The Giveaway:

While you’re waiting for The Art of Balance to relieve that stress, take a look at these free books and courses.

For Black Friday, I’ve teamed up with several other authors. We’re offering books and courses that promote physical and mental health. Books cover topics such as diet, fitness, stress relief, time management, general wellness, and minimalism.

You can find the offer here:Black Friday Free Books and Courses

There are 14 free books and courses altogether. Scroll down the page to see what might be helpful to you!

More soon,

– David

P.S. Back to our regularly scheduled programming next post!

Books:

Paths to Wholeness: Fifty-Two Flower Mandalas

52 (more) Flower Mandalas: An Adult Coloring Book for Inspiration and Stress Relief

52 Flower Mandalas: An Adult Coloring Book for Inspiration and Stress Relief

Paths to Wholeness: Selections (free eBook)

… and coming soon, The Art of Balance: Staying Sane in an Insane World

Copyright 2017, David J. Bookbinder

http://phototransformations.com

http://www.transformationspress.org

http://www.davidbookbinder.com

http://www.flowermandalas.org

November 15, 2017

Garbage and Flowers

For the last several years, I’ve found myself attracted to the dead leaves I see on the ground as I walk, particularly those in late fall and winter. I’ve taken thousands of pictures of them. A friend’s mentioning to me the concept of wabi-sabi helped me understand why.

For the last several years, I’ve found myself attracted to the dead leaves I see on the ground as I walk, particularly those in late fall and winter. I’ve taken thousands of pictures of them. A friend’s mentioning to me the concept of wabi-sabi helped me understand why. Wabi-Sabi is a Japanese term for finding the beauty in imperfection, and accepting the cycle of birth, growth, aging, death, and decay.

I’m 66. It’s about time.

The Buddhist teacher and writer Thich Nhat Hanh talks about this cycle when he speaks of seeing the garbage in the flowers and the flowers in the garbage. “When we look at garbage,” he writes, “we also see the non-garbage elements: we see the flower there. Good organic gardeners see that. When they look at a garbage heap they see cucumbers and lettuce. That is why they do not throw garbage away. They keep garbage in order to transform it back into cucumbers and lettuce.”

“If a flower can become garbage,” Thich Nhat Hanh explains, “then garbage can become flowers. The flower does not consider garbage as an enemy or panic when becoming garbage, nor does the garbage become depressed and view the flower as an enemy. They realize the nature of interbeing. In Buddhist therapy we preserve the garbage within ourselves. We do not want to throw it out because if we do, we have nothing left with which to make our flowers grow.”

The challenge is seeing the beauty in the decay, and then, to the extent this is possible, bringing it into the light.

Books:

Paths to Wholeness: Fifty-Two Flower Mandalas

52 (more) Flower Mandalas: An Adult Coloring Book for Inspiration and Stress Relief

52 Flower Mandalas: An Adult Coloring Book for Inspiration and Stress Relief

Paths to Wholeness: Selections (free eBook)

… and coming soon, The Art of Balance: Staying Sane in an Insane World

Copyright 2017, David J. Bookbinder

http://phototransformations.com

http://www.transformationspress.org

http://www.davidbookbinder.com

http://www.flowermandalas.org

November 1, 2017

Time: Visible and Invisible

My first experience of time as a continuum occurred when I was about ten years old. Before that, I think time was invisible to me.

I was riding my bike past Johnny Sybulski’s house and I stopped, suddenly, for no particular reason. I looked at the simple brick facade, the white trim, the unkempt bushes, and I became aware of myself looking. I thought, “This is just one second in my life, and I’ll never remember it again.” But that moment is one of my more vivid memories from childhood. It marked the beginning of my sense of myself as mortal.

Both of my grandfathers had died that year. In each case I had seen them nearing death in the hospital some weeks before and had seen their dead bodies in the funeral home. Perhaps that’s why I noticed that moment, or perhaps ten is when most boys begin to understand time and death; I don’t know. What I do know is that from that point on, time had a kind of linearity it had not had before, and this linearity soon became part of my background understanding of the cosmos. As I got older, time became invisible again, but differently than it had before.

Dr. Stephen L. Thaler, a physicist who has modeled near-death and death itself on a neural network, believes that as neurons die, the surrounding neurons experience the loss of their compatriots as life events. Somewhat like dreams or hallucinations, the death visions created by dying neurons are as real to the dying person as anything else he or she has ever experienced.

Thaler hypothesizes that this process continues until death is complete, and that “for all intents, the dying individual may experience forever, through the cascading death of nearly 100 billion brain cells (and an unfathomable number of interconnections) within an instant, resulting in a torrent of experience tantamount to eternity. It is as if life is going on for the trauma victim. However, the timeline at death has only a moment’s projection on the timeline we call ‘real.'”

According to the doctor and the nurses who resuscitated me, my near-death experience must have lasted no more than a minute or two. They said I was talking to them all the while they were attempting to transfuse me, and that even during the blackout period I had continually crossed my hands over my chest, perhaps in an effort to warm myself. (Like Snowden in Catch-22, I was cold, so cold). They seemed surprised when I told them I’d had a near-death experience. Busy with trying to keep me alive, they hadn’t noticed I’d left the room.

During that minute or two of their time, however, my time seemed infinite, my experience of being alive at once the most intense and the simplest of my recollected existence. In near-death, time does more than slow down, as it might during a more routine emergency. It changes altogether, collapses into a singularity and then spans out again, altered, like light refracted by a prism.

After surgery, time moved in a jerky fashion. No longer stopped dead, as it had been during the near-death experience, time nevertheless stretched out almost endlessly. Days went on forever, much as they had when I was a child, and the two weeks I spent at Sister’s Hospital seemed — seem, still, today — to contain the experience of years.

Those days are by far the longest of my existence, but this way of experiencing time continued for several months. Later, when I began to circulate among the ordinary living again, I felt as if decades had passed. It was as though I had been rewarded for my troubles with an elongated sense of time. This seemed good. But it was also as if I were a modern incarnation of Rip Van Winkle returning to a time and place that had moved on without me, a people among whom I could walk but with whom I no longer belonged. I could not talk about the things I had once cared about, could not easily pick up any of the activities I left behind. I had been away too long and had forgotten my old ways.

Like before, time had become visible.

Now I think about time a good deal more than I used to, especially during the gaps between ending one thing and beginning another, the “waiting for a bus” times: waiting for someone to pick up the phone as it rings, waiting for a television commercial to end, waiting for my computer to save a file so I can get back to work. Those times.

I think about the minute or two I was over there, on the “other side,” or if not there then very close to it, and of the similarities and differences between that minute or two and those others. (Waiting for a bus and waiting to die are both, after all, waiting, though in the former very little seems to change, while during the latter, when life actually was on hold, everything did.)

Then I think about other minutes that divide everything into “before” and “after”: the minute you find out your mate is having an affair, your boss tells you you’re fired, your doctor tells you you have cancer, your car slides out of control. Or the other side of the equation: the minute a child is born, a lottery won, a love relationship consummated.

These minutes, too, contain more life in them than an average month of ordinary and predictable experience, and I wonder why it is that instead of seeking out the moments when every drop of life, bitter or sweet, is hot and passionate, most of us gravitate towards those empty minutes, find comfort in those in-between times.

In the ensuing years since my near-death experience, time has once again started to become invisible, and as more years pass I suspect this process will continue. But like before, it will do so differently.

– David

Books:

Paths to Wholeness: Fifty-Two Flower Mandalas

52 (more) Flower Mandalas: An Adult Coloring Book for Inspiration and Stress Relief

52 Flower Mandalas: An Adult Coloring Book for Inspiration and Stress Relief

Paths to Wholeness: Selections (free eBook)

Copyright 2017, David J. Bookbinder

http://phototransformations.com

http://www.transformationspress.org

http://www.davidbookbinder.com

http://www.flowermandalas.org

October 31, 2017

Time: Visible and Invisible(and a Halloween trick-and-treat from Amazon.com)

NOTE: Trick-and-treat after this essay extracted from a book-in-progress about the impact of a near-death experience I had 25 years ago.

My first experience of time as a continuum occurred when I was about ten years old. Before that, I think time was invisible to me.

I was riding my bike past Johnny Sybulski’s house and I stopped, suddenly, for no particular reason. I looked at the simple brick facade, the white trim, the unkempt bushes, and I became aware of myself looking. I thought, “This is just one second in my life, and I’ll never remember it again.” But that moment is one of my more vivid memories from childhood. It marked the beginning of my sense of myself as mortal.

Both of my grandfathers had died that year. In each case I had seen them nearing death in the hospital some weeks before and had seen their dead bodies in the funeral home. Perhaps that’s why I noticed that moment, or perhaps ten is when most boys begin to understand time and death; I don’t know. What I do know is that from that point on, time had a kind of linearity it had not had before, and this linearity soon became part of my background understanding of the cosmos. As I got older, time became invisible again, but differently than it had before.

Dr. Stephen L. Thaler, a physicist who has modeled near-death and death itself on a neural network, believes that as neurons die, the surrounding neurons experience the loss of their compatriots as life events. Somewhat like dreams or hallucinations, the death visions created by dying neurons are as real to the dying person as anything else he or she has ever experienced.

Thaler hypothesizes that this process continues until death is complete, and that “for all intents, the dying individual may experience forever, through the cascading death of nearly 100 billion brain cells (and an unfathomable number of interconnections) within an instant, resulting in a torrent of experience tantamount to eternity. It is as if life is going on for the trauma victim. However, the timeline at death has only a moment’s projection on the timeline we call ‘real.'”

According to the doctor and the nurses who resuscitated me, my near-death experience must have lasted no more than a minute or two. They said I was talking to them all the while they were attempting to transfuse me, and that even during the blackout period I had continually crossed my hands over my chest, perhaps in an effort to warm myself. (Like Snowden in Catch-22, I was cold, so cold). They seemed surprised when I told them I’d had a near-death experience. Busy with trying to keep me alive, they hadn’t noticed I’d left the room.

During that minute or two of their time, however, my time seemed infinite, my experience of being alive at once the most intense and the simplest of my recollected existence. In near-death, time does more than slow down, as it might during a more routine emergency. It changes altogether, collapses into a singularity and then spans out again, altered, like light refracted by a prism.

After surgery, time moved in a jerky fashion. No longer stopped dead, as it had been during the near-death experience, time nevertheless stretched out almost endlessly. Days went on forever, much as they had when I was a child, and the two weeks I spent at Sister’s Hospital seemed — seem, still, today — to contain the experience of years.

Those days are by far the longest of my existence, but this way of experiencing time continued for several months. Later, when I began to circulate among the ordinary living again, I felt as if decades had passed. It was as though I had been rewarded for my troubles with an elongated sense of time. This seemed good. But it was also as if I were a modern incarnation of Rip Van Winkle returning to a time and place that had moved on without me, a people among whom I could walk but with whom I no longer belonged. I could not talk about the things I had once cared about, could not easily pick up any of the activities I left behind. I had been away too long and had forgotten my old ways.

Like before, time had become visible.

Now I think about time a good deal more than I used to, especially during the gaps between ending one thing and beginning another, the “waiting for a bus” times: waiting for someone to pick up the phone as it rings, waiting for a television commercial to end, waiting for my computer to save a file so I can get back to work. Those times.

I think about the minute or two I was over there, on the “other side,” or if not there then very close to it, and of the similarities and differences between that minute or two and those others. (Waiting for a bus and waiting to die are both, after all, waiting, though in the former very little seems to change, while during the latter, when life actually was on hold, everything did.)

Then I think about other minutes that divide everything into “before” and “after”: the minute you find out your mate is having an affair, your boss tells you you’re fired, your doctor tells you you have cancer, your car slides out of control. Or the other side of the equation: the minute a child is born, a lottery won, a love relationship consummated.

These minutes, too, contain more life in them than an average month of ordinary and predictable experience, and I wonder why it is that instead of seeking out the moments when every drop of life, bitter or sweet, is hot and passionate, most of us gravitate towards those empty minutes, find comfort in those in-between times.

In the ensuing years since my near-death experience, time has once again started to become invisible, and as more years pass I suspect this process will continue. But like before, it will do so differently.

– David

Here’s the trick – and treat!

Halloween sale of my book Paths to Wholeness on Amazon

From time to time, for reasons known only to Amazon’s algorithm, they drop the prices of books, and this time they dropped the price of mine from $40 to $27.19. I have no control over this and the price will probably go back up after the current stock is sold out, so get ’em while they’re cheap!

Books:

Paths to Wholeness: Fifty-Two Flower Mandalas

52 (more) Flower Mandalas: An Adult Coloring Book for Inspiration and Stress Relief

52 Flower Mandalas: An Adult Coloring Book for Inspiration and Stress Relief

Paths to Wholeness: Selections (free eBook)

Copyright 2017, David J. Bookbinder

http://phototransformations.com

http://www.transformationspress.org

http://www.davidbookbinder.com

http://www.flowermandalas.org

October 25, 2017

First there is a mountain, then there is no mountain, then there is!

A recent trip to Vermont reminded me that, although I’m still enamored of the mountains north of Santa Fe, NM, New England mountains also have their particular, softer charm.

Some views of the Green Mountains, north and south

P.S. If you find what you read here helpful, please forward it to others who might, too. Or click one of the buttons below the blog entry.

Comments always appreciated!

Books:

Paths to Wholeness: Fifty-Two Flower Mandalas

52 (more) Flower Mandalas: An Adult Coloring Book for Inspiration and Stress Relief

52 Flower Mandalas: An Adult Coloring Book for Inspiration and Stress Relief

Paths to Wholeness: Selections (free eBook)

Copyright 2017, David J. Bookbinder

http://www.transformationspress.org

http://www.davidbookbinder.com

http://www.flowermandalas.org

October 11, 2017

Love Lives On

The gaze of love is not deluded. Love sees what is best in the beloved, even when what is best in the beloved finds it hard to emerge into the light.

– J. M. Coetzee

When I was 25, living in Manhattan, and trying to jump-start a career in writing and photography, I visited my parents and brothers in Buffalo two or three times a year. On those trips, I also saw my maternal grandmother.

It was painful to witness Bubby’s decline. Though only in her mid 70s, by then she was legally blind, mostly deaf, unable to manage on her own. She had a room at a Jewish nursing home downtown, an institutional environment where I always felt uneasy.

On one visit, as I was leaving I noticed two of Bubby’s former neighbors sitting in folding chairs on the lawn. I went over to them. Mr. Klein’s recent stroke had paralyzed one side of his body and frozen half his face; his attempts to talk were unintelligible. Mrs. Klein, however, seemed virtually unchanged since I’d last seen her, more than ten years before. She asked how I was and what I was doing. I described my hoped-for journalism career and told her about my girlfriend, with whom I had briefly lived after college, and whom I had followed to New York. Our relationship was difficult, I told Mrs. Klein, “but I love her.”

“Love?” Mrs. Klein said, gesturing toward her crippled husband. She looked me in the eyes. “Love is 50 years.”

In that moment my concept of love changed permanently.

There Mrs. Klein was, content to be living in a place I found disturbing even to visit, because that’s where her husband needed to be. I understood that for her, love wasn’t about sex or passion, or getting what she needed, or even conversation. Nor was it about soul mates, shared interests, “chemistry,” or any of the other things I sought in a relationship. Instead, it was about setting aside her needs for the sake of another and feeling no resentment.

Unless I somehow beat even the most wildly optimistic predictions for life expectancy, I will never approach Mrs. Klein’s 50 years with one person. But I have long reflected on that conversation, and in the decades since then I’ve been learning to embrace what she was trying to teach me. Through a much different path, I have come to a similar place: to see that love is about recognizing the essential humanity of the other person in toto and responding to it with an open heart.

In his poem “New Heaven and Earth,” D. H. Lawrence wrote about crossing over from a world “tainted with myself” into “a new world.” Before his crossing, “I was a lover. I kissed the woman I loved, and God of horror, I was kissing also myself. I was a father and begetter of children, and oh, oh horror, I was begetting and conceiving in my own body.” Afterward, when he reaches out in the night and touches his wife’s side, he experiences her not as an extension of himself, but as “she who is the other.” When we experience others as truly other, with their own needs, wants, and desires, we can begin the process of fully loving them.

Love need not even be requited. In the surrealistic movie Adaptation, based on the novel The Orchid Thief, Nicholas Cage portrays twin brothers, Charles and Donald Kaufman. Toward the end of the film, both brothers are pinned down in a swamp at gunpoint by the author of the novel (played by Meryl Streep) and her lover. Facing death, Charles tells Donald a secret he has been keeping since high school: He’d often seen his brother flirting with a girl who seemed kind and sweet when she was with Donald, but made fun of him with her friends as soon as he was out of earshot. To spare Donald’s feelings, Charles had kept this to himself all those years.

“I heard them,” Donald says.

“How come you looked so happy?” Charles asks.

“I loved Sarah, Charles,” Donald says. “It was mine, that love. I owned it. Even Sarah didn’t have the right to take it away.”

“She thought you were pathetic.”

“That was her business, not mine. You are what you love, not what loves you,” Donald says.

Being a therapist has helped me to practice loving selflessly. Therapeutic love is about seeing and accepting the essential nature of someone, what pioneer psychologist Carl Rogers called “unconditional positive regard,” and then reflecting it back, if necessary holding it for safekeeping when the object of that love can’t yet take it in. It is the foundation of the best therapeutic relationships, a love seldom directly stated and also, I believe, one that’s necessary for any truly healing relationship.

Like Donald’s love in Adaptation, selfless love asks for nothing in return, and it does not end when the beloved is gone. The love itself lives on.

P.S. If you find what you read here helpful, please forward it to others who might, too. Or click one of the buttons below.

Books:

Paths to Wholeness: Fifty-Two Flower Mandalas

52 (more) Flower Mandalas: An Adult Coloring Book for Inspiration and Stress Relief

52 Flower Mandalas: An Adult Coloring Book for Inspiration and Stress Relief

Paths to Wholeness: Selections (free eBook)

Copyright 2017, David J. Bookbinder

http://www.transformationspress.org

http://www.davidbookbinder.com

http://www.flowermandalas.org

September 26, 2017

Electrocuting the Ants

I did terrible things to insects as a child.

Like many other boys growing up with nothing better to do, I tore the legs off Daddy Longlegs, incinerated pill bugs with magnifying glasses, and set fire to more than one ant hill. But I didn’t stop there.

I was a kid scientist. Spurred on by the early space program and largely ignored by the adults around me, I dreamed of one day voyaging to the stars. Meanwhile, to prepare myself, I read Asimov, Clarke, Heinlein, Bradbury, and other SF masters of the day. At the same time, I plowed through one field of scientific inquiry after another, beginning with magnets and batteries – I built my first lead-acid battery when I was seven – and moving quickly through fossils, geology, chemistry and electronics. But entomology was my most enduring interest and bugs were my favorite experimental subjects.

The insect kingdom was convenient for testing ideas that came up in both my scientific and science fictional pursuits. My interest was, I believed, purely clinical. I was training myself to become the perfect scientist: dispassionate, precise, even ruthless in the pursuit of Knowledge.

So, in the name of Science and in imitation of the Martians in H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds, I removed the parabolic mirror from my telescope and used it to build a crude ray gun, on sunny days incinerating dozens of hapless bugs. Inspired by the pioneering efforts of the space program – I had a National Geographic poster of the solar system on one wall of my bedroom and on another a chart comparing the Russian and American unmanned satellites – I loaded grasshoppers and crickets into model rockets and blasted them into the sky. Unfortunately, like the dogs and monkeys who were carried aloft by grown-up rockets, few of my astronauts survived. Sea Hunt and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea led me to investigate building self-sustaining underwater environments, and in the course of my researches, I discovered that electricity breaks down salt water into hydrogen and chlorine gas. I caught flies and bleached them in hyper-chlorinated water, a byproduct of this process, until their bodies became translucent and their eyes glowed a piercing bright red.

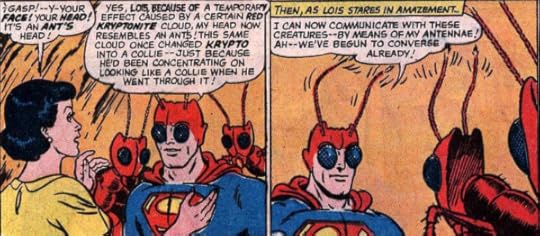

I found all bugs interesting, but I think it was Superman who first got me to home in on ants. Though I soon graduated to more sophisticated characters like X-Men and The Fantastic Four and finally to genuine science fiction, Superman was my earliest superhero, and the Man of Steel always had a special place in my pantheon.

In one issue, the Caped Crusader was exposed to red Kryptonite, which transformed him into a creature with the body and mind of a man and the head and special abilities of an ant. This metamorphosis, though horrifying to Lois Lane, turned out to be a lucky break for humanity. Nearby, an army of mutant ants which had grown to gargantuan size was threatening Metropolis. The transfigured Man of Steel was able to communicate with the ant Queen antenna-to-antenna and persuade her to follow him, with her flock, into outer space. Happily, the effects of the Kryptonite wore off soon after Superman’s return to Earth, restoring his familiar blue-haired, manly visage.

Though I could never match the Man of Steel’s skill in ant argot, on a summer’s day I would spend hours in the back yard watching these ingenious creatures conduct their subtle and mysterious business. To test the abilities of their tiny minds, I’d block their path with twigs and fingers, forming impromptu obstacle courses for them to find their way around. It was ants who first fell to the death ray of my telescope’s mirror, and ants who were my first aquanauts, held under water on a leaf or twig, small bubbles of air clinging to their skinny bodies until they ceased to move. Later, it was ants I threw into jars filled with sulfur dioxide gas, and then, briefly remorseful, attempted to revive with pure oxygen.

Ants abruptly and permanently ceased to be my subjects, however, shortly after I turned twelve.

As a school science project, I had built a Tesla coil. This was an air-core transformer capable of producing tremendously high voltages at very small currents. It was first created by Nikola Tesla, the Serbian-born inventor who discovered alternating current and the principles behind radio. My coil, constructed from a cardboard tube that linoleum came in and parts scavenged from broken TVs, generated about 100,000 volts of radio-frequency energy, enough to light fluorescent bulbs from across a room and to interfere with the neighbors’ television reception. It made a monstrous noise, reminiscent of the Jacob’s Ladders I’d seen in old Frankenstein movies. With it I had won the 7th grade science fair.

After the fair, I continued to read up on Tesla and his inventions and to experiment with his device. One thing I learned was that six- or seven-inch sparks could jump from the coil to my hand without hurting me because high-frequency electricity flowed only along the outer surfaces of objects. When I grew tired of making my fingers twitch, shocking my kid brothers, and remotely lighting fluorescent bulbs, I began to wonder what would happen to smaller life forms if they were subjected to this surface-seeking current.

My studies of ants often ran in parallel with other investigations. While I was experimenting with the Tesla coil, I had also been cultivating an ant farm. I’d dug up the ants from an ant hill at the base of the swing set in our back yard and filled a large peanut butter jar with a mixture of ants and dirt. Then I’d punched tiny holes in the lid and covered the sides of the jar with black construction paper to keep out the light. Every few days I placed bread crumbs and chopped-up raisins on top of the soil and added water to a Coke bottle cap I’d set up as a trough.

After a week, I took the paper off and found, as I’d hoped, that the ants had made this jar their home. They’d built a maze of tunnels, visible through the sides of the jar, and had deposited stores of food in miniature cul-de-sacs. The ant farm appeared to be a successful community – at any rate, far more so than the crop of “sea monkeys” I’d tried to raise from a kit ordered through DC Comics, or the pollywogs we caught at Boy Scout camp that never quite made it to frogs. From time to time I’d remove the paper to see what new works the ants had created, and I’d periodically refill the Coke bottle top and toss in scraps of food. I began to wonder what to do with it next.

One Saturday morning, directly after Mr. Wizard – an early hero, until I learned he’d run off with his secretary – I turned on the Tesla coil. I tested its spark by drawing it to my fingertips, then picked up the ant farm jar and let the spark discharge through it into my hand. To be sure I was well grounded, I’d grabbed one of the metal poles that supported the I-beam in the center of our house. I felt the shock ripple through one hand and across to the other, saw it snake along the black paper covering the jar, which I’d left in place like an executioner’s mask. A few seconds later I put the jar down and switched off the power.

I don’t think I would have been affected much if, when I examined the ant farm the next day, all of them had been killed; I had already sacrificed many ants in the name of Science. Conversely, had they been unscathed, this would merely have confirmed what I’d learned about high-frequency electricity. I was prepared for either of these outcomes. But instead, when I stripped off the paper and unscrewed the top of the jar, I found a few ants still scurrying through their tunnels and, neatly stacked at the entrance to one of them, a mound of dead ants.

It had never occurred to me that only some of the ants would die, or that ants were sentient creatures who valued their lives as much as I did mine and would respond meaningfully to death. Survivors of their own miniature holocaust, the ants had dealt with the unthinkable as best they could and moved on.

My whole view of ants, and of all living creatures, changed forever in that moment. Solemn and remorseful, I brought the ravaged ant farm outside, back to the ant hill from which it had come. I dumped out the contents of the jar and left it to the survivors and their kin to sift the living from the dead. I tossed the jar itself into the garbage and, a few weeks later, moved the Tesla coil out to the garage.

On that day my experiments with insects ceased and my apprehension of what it is to live, and die, and grieve began.

P.S. If you find what you read here helpful, please forward it to others who might, too. Or click one of the buttons below.

Books:

Paths to Wholeness: Fifty-Two Flower Mandalas

52 (more) Flower Mandalas: An Adult Coloring Book for Inspiration and Stress Relief

52 Flower Mandalas: An Adult Coloring Book for Inspiration and Stress Relief

Paths to Wholeness: Selections (free eBook)

Copyright 2017, David J. Bookbinder

http://www.transformationspress.org

http://www.davidbookbinder.com

http://www.flowermandalas.org

September 20, 2017

How to leap tall buildings in a single bound

The only way to find the limits of the possible is by going beyond them to the impossible.

– Arthur C. Clarke

During much of my childhood, I lived in the realm of possibility: machine intelligences, aliens, mutants, future worlds, alternate pasts. Infinite possibilities.

My first science fiction book was Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot. I was 10 when I found a copy at a Temple Sinai rummage sale. It opened the universe to me. Soon, I was wandering over to the adult section of the library every week, taking out as many science fiction books as the librarian would permit. I also haunted the local pharmacy’s rack of science fiction and mystery novels, trying to figure out how best to allocate my 50-cent allowance. By my early teens, I had amassed a collection of several hundred science fiction books and had read many more.

Around the time I discovered Asimov, I decided I wanted to be a “space scientist,” a dream that carried me all the way through my first year of engineering school. By then, I had stopped reading science fiction – I’d put away childish things – but my love affair with it never really ended. Twenty years later, I was in a PhD program in English, and to take a break from the dry, abstract, literary theory that English Studies had devolved into, I revisited the stories I had read as a boy.

It was like starting a new romance with an old lover.

I was one among many boys and girls whose interest in science was catalyzed by science fiction. The list of inventions and discoveries that came into being because science fiction writers imagined them – and children who read their stories or watched them on television became engineers who built them – is long.

Star Trek alone inspired cell phones, video conferencing, speech recognition, tablet computers, medical imaging, hyposprays, memory cards, biometrics, wireless earpieces, 3-D printers, machine translators, flat-screen televisions, and directed-energy weapons. Other contributions of science fiction include space flight, scanning for habitable planets and alien life, biodomes, computers, robots, artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and the multitude of products derived from these technologies.

At least as important as its technological influences is science fiction’s re-imagining of human potential. In the introduction to her gender-bending novel The Left Hand of Darkness, Ursula Le Guin describes how science fiction can expand our ideas of human possibility.

“If you like you can read it, and a lot of other science fiction, as a thought-experiment. Let’s say (says Mary Shelley) that a young doctor creates a human being in his laboratory; let’s say (says Philip K. Dick) that the Allies lost the second world war; let’s say this or that is such and so, and see what happens…. Thought and intuition can move freely within bounds set only by the terms of the experiment, which may be very large indeed.”

Rod Serling’s ’60s series The Twilight Zone is one example among many whose thought experiments explored sociopolitical realities and possibilities that conventional media suppressed. To bypass the censors, Serling migrated scripts about bigotry, gender roles, government oppression, politics, and war to distant planets, future times, or alternate versions of the present.

Although it has its share of “escape” fiction, the science fiction genre also contains some of the most thought-provoking works in all of literature. On a scale more ambitious than most conventional fiction, science fiction not only asks but also posits answers to the largest questions: How did this universe come into being? How will it end? Where does consciousness come from? What is its purpose? How will we end? Who will replace us?

Science fiction inspires us to reach not only for the stars, but also deeply within. In this way, it overlaps with psychotherapy, another way for us to boldly go where we have not gone before.

In today’s insurance-managed world, psychotherapy has been categorized as just another medical modality. But as science fiction is more than space operas, robots, time travel, and aliens, psychotherapy is more than “behavioral health.” Psychotherapy, too, is about making the “impossible” not only possible, but probable, through acts of imagination. The psychotherapy treatment room is a laboratory for a different kind of thought experiment. Clients ask: What if I were to test this limit, take steps down that path, plunge into these waters? Over time, they become emboldened to do what their parents, teachers, or peers had convinced them was impossible.

Christopher Reeve, the actor who played the omnipotent Superman, once said, “So many of our dreams at first seem impossible, then they seem improbable, and then, when we summon the will, they soon become inevitable.” You don’t have to be Superman, a therapist, or even a science fiction fan to actualize your possibilities. All you need is an act of imagination and the will to sustain it.

– David

P.S. If you find what you read here helpful, please forward it to others who might, too. Or click one of the buttons below.

Books:

Paths to Wholeness: Fifty-Two Flower Mandalas

52 (more) Flower Mandalas: An Adult Coloring Book for Inspiration and Stress Relief

52 Flower Mandalas: An Adult Coloring Book for Inspiration and Stress Relief

Paths to Wholeness: Selections (free eBook)

Copyright 2017, David J. Bookbinder

http://www.transformationspress.org

http://www.davidbookbinder.com

http://www.flowermandalas.org

September 13, 2017

The Cast of Characters

NOTE: I’ve been working with an illustrator on the characters in my forthcoming book on balance and thought you might be interested in what we’ve developed. Here’s the cast of characters and a brief introduction to them.

Know thy self, know thy enemy.

– Sun Tzu, The Art of War

This is a book about balance: What disrupts it, what restores it, and how to keep it going.

It is also a story, and like any story, it has a cast of characters.

Some are friends and fellow travelers. Some are enemies. In the pages of this book you will come to know them well. But first, some introductions.

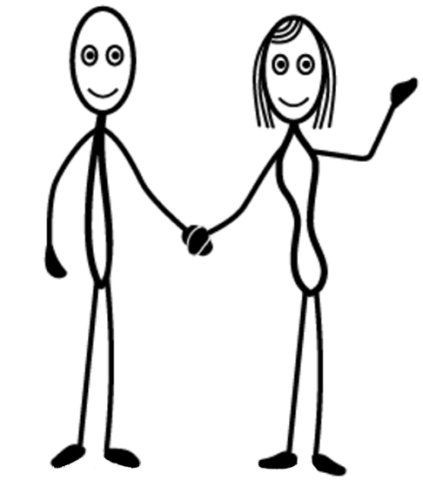

Al/Alice

We are the heroes of this saga, an epic battle not only for balance but literally for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

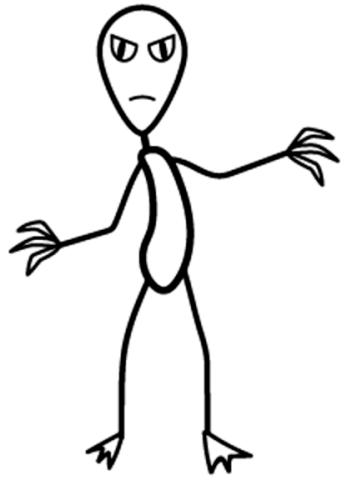

UnBalancer

The villain in our story is the nefarious UnBalancer.

UnBalancer is a fearsome and sometimes deadly force. It strives single-mindedly to unseat us, and sometimes it wins the battle – but not, as we’ll see, the war.

Balancer

Our chief ally in combating UnBalancer is Balancer.

Balancer is the internal stabilizer that handles day-to-day stresses. It keeps us sane and balanced most of the time and, for the most part, holds UnBalancer at bay.

Emphasis on “for the most part.” When Balancer falls, things can get wonky fast.

ReBalancer

Fortunately, Balancer is not our only ally.

Balancer’s trusty sidekick, ReBalancer, leaps into action when UnBalancer gets the upper hand.

ReBalancer is a good friend to have in a crisis.

Balanced/UnBalanced/ReBalanced Cycle

Here’s how these folks work to keep us sane:

That’s the cast. Stay tuned to catch them in action! (And please leave a comment to say hello.)

– David

P.S. If you find what you read here helpful, please forward it to others who might, too. Or click one of the buttons below.

Books:

Paths to Wholeness: Fifty-Two Flower Mandalas

52 (more) Flower Mandalas: An Adult Coloring Book for Inspiration and Stress Relief

52 Flower Mandalas: An Adult Coloring Book for Inspiration and Stress Relief

Paths to Wholeness: Selections (free eBook)

Copyright 2017, David J. Bookbinder

http://www.transformationspress.org

http://www.davidbookbinder.com

http://www.flowermandalas.org