Christopher G. Nuttall's Blog, page 27

July 11, 2021

Updates

Hi, everyone

It’s been a busy couple of weeks. I’ve finished the first draft of The Prince’s War (Prince Roland’s story, The Empire’s Corps) and I’ve resolved to try and take it a little easier for this week. That said, I do have edits for Child of Destiny and Stuck in Magic, which will be published as the start of a spin-off series (provisional title for Book 2 is Her Majesty’s Warlord), as well as a handful of other loose ends to worry about at some point. I’ve fallen behind on my email, so I probably need to do something about that too (sorry if you emailed me and I didn’t reply.)

I’m unsure what to write next, to be honest. I’m torn between The Cunning Man, which is a massively expanded (and third person) version of the novella in Fantastic Schools III (which could do with some review love, if anyone’s interested) and Standing Alone, which is the more or less direct sequel to Cast Adrift. Owing to a slight mix-up, mainly my fault, any cover for Cunning will be delayed, which will give me time to edit but also slow production a little. Let me know which one you want, please.

In other news …

I’ve been considering a weird little idea partly inspired by Barb’s Changing Faces. The basic concept is that there’s a pair of university students, a man and woman in their twenties, who have an argument over who had it worst in the past – men or women. A goddess/Q-type meddler overhears the argument and decides to show them what it was really like by sending them back in time (and possibly into a fantasy universe) and gender-swapping them. The young man becomes a young noblewoman, the young woman becomes a low-ranking nobleman fostered at the noblewoman’s castle. They rapidly find out the past isn’t a bed of roses for anyone.

I haven’t decided where to take the story yet. Part of me wants to keep it as an intensely personal story, with the two struggling to survive and establish themselves; part of me wants to think of it as another tech uplift story and/or fantasy setting story.

What do you think?

Chris

Draft Afterword: Stuck in Magic

Again, comments are welcome.

Afterword

Back in 2000, or thereabouts, I was a member of a short-lived book club – short-lived, I have to admit, because while we were all interested in books we were not interested in the same types of books. It was hard to find books that we were all willing to read, let alone discuss, and while it did expose me to different genres that broadened my mind a little it also convinced me that some people had takes on books that never agreed with mine. One of those takes stuck in my mind.

We were reading the first book in the Outlander series, by Diana Gabaldon. (It was titled Cross Stitch in the UK, but I’m going to stick with the US title here.) The basic plot is relatively simple; Claire Randall, a nurse from 1940s Britain, finds herself stranded in 1740s Scotland, shortly before the Jacobite Rising of 1945. She is taken in by the local community, uses her medical skills to impress them, weds a young man – Jamie – and eventually becomes involved in the morass of political and personal struggles threatening to tear the Highlands apart. It was, I thought, a good novel, but not one that interested me; Claire didn’t seem to have any real impact on history, not even introducing better medicine and suchlike.

One of the other readers, a young woman, thought it was a brilliant novel. She liked the idea of going back in time and marrying a man from a simpler age. I found that attitude difficult to process. Claire fell into a world of disease and deprivation, where a person without kin had little hope of survival; a world where women, such as Claire, were pretty much the property of their husbands. There is even a scene where Claire is physically disciplined by Jamie and while it is possible to argue that Claire deserved it, or that Jamie had no choice but to make it clear to the rest of the clan that Claire had been punished, it doesn’t mask the fact that the world of 1740 was not kind to anyone. The idea of someone wanting to go back in time and live there struck me as absurd. They would be throwing away both the comforts of the modern world and their own safety.

It is always fun to romanticise the past, and how to consider how it might be changed by an influx of ideas from the future. It would not, however, be easy to have any lasting impact (certainly if you happened to be a single person with no real proof of your story). Our ancestors generally had good reasons for being the people they were. Their societies were adapted to realities that we simply don’t understand. We recoil in horror when we look back at the sins of the past – slavery, conquest, semi-rigid gender roles – without realising that our ancestors had less choice than one might suppose. They had attitudes, shaped by their environment, that often made them seem an alien people. It is easy to think they were very primitive and indeed stupid. How could they take such obvious untruths for granted? But the simple fact is that they didn’t know they were untruths and it took time, decades and centuries, for society to advance to the point they could be put in the past, where they belonged. The world of our ancestors had no place for them.

Consider, education. It took years, in the past, to teach someone to read and write, let alone turn them into an educated man, even by the standard of the time. Who amongst the common-born had time for it, when they had to scrape a living from the land? The idea of universal education simply didn’t catch on – it couldn’t – until society reached the point where it could support children in schools, instead of forcing the children to work from a very early age. When our ancestors did something, they generally had a reason for it.

Now, what does that have to do with Schooled in Magic and Stuck in Magic?

Emily did not realise, at least for several years, that when she arrived in the Nameless World she arrived at a very high level indeed. She had magic, which made her a de facto noblewoman; she was popularly believed, amongst the local chattering classes, to be the bastard child of one of the most powerful sorcerers in the known world. And she was at Whitehall, a relatively safe environment compared to the rest of the world. People were prepared to listen to her, and give credence to her words, even before she became the Necromancer’s Bane, Duchess of Cockatrice, Mistress of Heart’s Eye, etc. This gave her enough room to introduce a handful of simple innovations, which took off like rockets and ensured some of her more radical ideas got a chance to breathe. She had her failures – some ideas didn’t work because she didn’t know the details – but she had enough credibility, by this point, for her missteps to be overlooked.

And, even though a sizable number of powerful people were growing increasingly concerned about her, and her impact on their society, they were reluctant to take open steps to deal with her for fear of the consequences. By the time they tried, it was too late to put the genie – they would have seen it as a demon – back in the bottle. Killing Emily would not have stopped the revolution she (accidentally) started.

Elliot has none of those advantages. He is a man without magic, a soldier in a world that regards soldiers – at best – as parasites. Worse, perhaps, he is a man – and therefore automatically seen as more threatening than the younger Emily – without any real social position at all. He is a child of his world, just like Emily, but he’s in an environment that takes a far dimmer view of his ‘eccentricities.’ He has no rights, beyond those he can secure for himself; he has no patron, at least at first, to provide political cover and protection. He doesn’t have the option of dispensing ideas and concepts as a farmer might scatter seeds on the ground, to see which ones sprout into life; he has to get down and dirty just to build a place for himself before he winds up dead in a ditch. Emily can afford to take risks with people like Harbin Galley. Elliot cannot.

I went back and forth about writing this story for a long time. Part of it was concern about crossing wires with The Cunning Man; part of it was fear about breaking the world I’d created over twenty-four novels and four novellas. I only decided to do it because I had the first scene rattling around in my head, demanding I write it. I’d been meaning to try to write a serial, so I plotted out a rough story and wrote two-four chapters per month until I reached a logical stopping point. And then I started drawing up the plans for the next book, Her Majesty’s Warlord.

I’m not sure, yet, how the next book will be written. A serial, like this one, or a more normal project? (One thing I discovered, when looking over the files, was that the serial format created headaches of its own.) Nor do I know, yet, if Eliot will ever meet Emily (although I think that, one day, they probably should come face to face.) As always, if you have any thoughts on the matter, feel free to let me know.

And now you’ve read this far, I have a request to make.

It’s growing harder to make a living through writing these days. If you liked this book, please leave a review where you found it, share the link, let your friends know (etc, etc). Every little helps (particularly reviews).

Thank you.

Christopher G. Nuttall

Edinburgh, 2021

July 10, 2021

Draft Afterword: The Prince’s War

This is the draft, so any comments are welcome.

Afterword

“When Adam delved and Eve span, Who was then the gentleman? From the beginning all men by nature were created alike, and our bondage or servitude came in by the unjust oppression of naughty men. For if God would have had any bondmen from the beginning, he would have appointed who should be bond, and who free. And therefore I exhort you to consider that now the time is come, appointed to us by God, in which ye may (if ye will) cast off the yoke of bondage, and recover liberty.”

-John Ball

Someone – I forgot who – once complained that science-fiction writers could only imagine monarchies, that numerous stories set in the far future included monarchies that wouldn’t have been unrecognisable to our ancestors from the distant past. Their complaint, if I recall correctly, was that there were other possibilities – direct democracy, for example, or actually workable communism – and monarchies were just plain lazy. Leaving aside the simple observation that monarchies tend to make for better stories, even if you wouldn’t want to live in those worlds personally, the simple truth is that the human race has been governed by monarchies for thousands of years. Large-scale constitutional democracy is actually, on a historical scale, a fairly new invention. Indeed, monarchy appears so often that one is tempted to wonder if there is something in humanity that adores a monarch.

The historical record seems to suggest that democracies have a fairly short shelf life. The democracy of Athens, which operated on a very limited franchise, was brought low by its own internal quarrels and weaknesses and eventually gave way to outside rule. The Roman Republic effectively suffocated under the weight of its own empire, eventually leading to civil war and the de facto creation of a monarchy. Peasant revolts against the European aristocracies often ended with the peasants choosing not to land the killing blow, only to be slaughtered when the aristocrats regained their nerve; the downfalls of King Charles I and Louis XVI were rapidly followed by political chaos, the rise of rulers with monarchical powers (Cromwell, Napoleon) and, eventually, the restoration of the monarchy. Even the modern-day United States has not been immune to this trend. President Bush43 was the son of President Bush41, while Hilary Clinton was the wife of President Clinton42; there are, as of writing, suggestions that the wives or daughters of Presidents Obama44 and Trump45 will enter politics. If they do, their connections will both help and hinder them.

Monarchy, a system of hereditary rule, is in fact near-universal throughout human history. So are the problems it brings in its wake. A king who remains in power too long will grow set in his ways, unable to change with the times. Strong and capable kings give way to sons who are far less capable and therefore weaken – and sometimes lose – the throne. And, of course, there is not even the pretence of democracy. Kings claimed to be the protectors of their people – smart rulers worked hard to create the illusion all the bad stuff was done by evil counsellors, who could be sacrificed if necessary – but the idea of commoners having a say in their own affairs was effectively blasphemy.

Why did this happen?

The first king, it is often said, was a lucky bandit. This isn’t entirely true – no one can call Augustus Caesar a bandit – but there is a degree of truth in it. The first kings (however termed) were men who reshaped society to support their primacy, creating a network of supporters who upheld the king’s position because to do otherwise would weaken their own position. This pattern was followed by every successful king, but also powerful figures as diverse as Hitler, Stalin and Saddam Hussein. The reshaping gave the aristocrats, however defined, a stake in society; it also carved out a logical and understandable chain of command and line of succession that provided a certain governmental stability. There could not be – in theory – any struggle over the succession, once a king died. His firstborn son would take the throne. In practice, it was often a little more complex. It was not until the institution of monarchy became predominant within Western Europe that the line of succession was clearly laid down and unhappy heirs still posed potential threats to newly crowned monarchs (and usurpers, such as Napoleon, found it hard to gain any real legitimacy.)

This structure went further than you might think. It co-opted religious institutions, merchants and, right at the bottom, commoners, serfs and de facto slaves. It was incredibly difficult for them to rise in the world, but there was – again, in theory – certain limits on how badly they could be abused. They knew their place in the world, yet they also knew how far their lords could go. The Poll Tax of 1381 England, for example, was sparked by the government demanding more and more taxes, taxes that were beyond the commonly accepted levels and collected with a previously known fervour. The monarch’s representatives had broken the rules, as far as his subjects were concerned, and therefore waging war on them – to teach them a lesson, rather than destroy them – was perfectly legal. Naturally, the aristocracy disagreed.

There were, at least in theory, advantages to this structure. The king was a known figure, a person who could reasonably expect to be on the throne for decades and therefore show a degree of long-term planning; the imperative to sire a heir and a spare was a clear commitment to securing the future of his holdings. The king would have a bird’s eye view of the kingdom, as well as experience in administration and warfare, and could therefore make decisions that benefited the entire kingdom. On paper, monarchy may seem to be amongst the better forms of human government.

The problems of monarchical rule, however, are manifold. No human ever born can hope to absorb and process an entire country’s worth of information, even when that information reaches the monarch without being altered by his servants. Kings therefore make poor decisions because they don’t know what’s really going on. Second, kings are often the prisoners of their own throne. A king cannot easily rule against his great lords, the ones who are abusing the commoners, for fear of turning them against him permanently and therefore being disposed when a new challenger arrives. Third, a king’s sons are rarely as capable as their father because they haven’t struggled and suffered in quite the same way. The great kings of England – Henry II, Edward I, Henry V, James VI and I, Charles II – were often followed by sons and grandsons who lacked their father’s insight. Indeed, a heir’s failings may become apparent very early on – Henry the Young King, for example – but because of the nature of monarchy it was very difficult to remove them from the line of succession.

And, when they become kings in their own right, they were very hard to remove. Richard II was disposed by his own cousin, Henry VI became a pawn in the original game of thrones, Charles I had his head lopped off after a civil war and James II was replaced by his sister and brother-in-law. The price of monarchy, in short, is periods of instability caused by kings who were not up to the task, or lacked a power base of their own (Mary of Scotland) and ambitious aristocrats manoeuvring for power.

At its core, the problem of monarchy is that it puts the primacy of the monarch and his aristocrats ahead of the interests of the entire kingdom. The king practices – he must practice – a form of nepotism. He must put forward men who are loyal to him personally, rather than the kingdom itself; he must use his sons and daughters as pawns on the diplomatic chess board, rather than let them marry for love (or bring new blood into the monarchy). He must raise his sons to take his place, all too aware that refusing to grant them real power will lead to resentment, hatred and (perhaps) civil war when – if – the heir’s courtiers start pushing him to grant favours he simply doesn’t have the wealth or power to give. The kingdom therefore becomes a collection of scorpions in a bottle, the monarchy unwilling to make any compromises for fear of where they will lead, let alone allow people to question his power, and the aristocracy unwilling to put aside its prerogatives for the greater good. This is a recipe for chaos and revolution. And revolution can often lead to a tyranny worse than the now-gone monarchy.

***

Why, then, are monarchies so popular?

There’s one argument that suggests the myth – and yes, it is a myth – of the ‘Father Tsar’ is actually quite appealing, that one can find comfort in it as one might find comfort in spiritualism and religion. There’s another that suggests a person bred and trained for power will do a better job than someone elected into their position, although both the historical record and simple common sense suggestions otherwise. And there’s a third that says we look at the fancy outfits and romantic lives and don’t recognise the downsides. And there’s a fourth that hints we all want to surrender our autonomy, to unite behind a single divinely anointed leader and follow him wherever he leads, rather than questioning him too closely for fear of what we might find. Personality cults are growing increasingly common these days and those who ask if the emperor has no clothes often come to regret it.

Personally, I think the blunt truth is that very few of us have any real idea of what it is like to live under an absolutist monarchy. The few remaining western monarchies are jokes, compared to their predecessors. It is easy to watch Bridgeton and debate whether or not Daphne raped Simon; it is harder to understand why a real-life Daphne might feel driven to such an action, or the consequences if she’d taken any other course. The fancy costumes we love hide a grim reality, one better left in the past. As the joke goes …

“My girlfriend wanted me to treat her like a princess. So I married her off to a man old enough to be her father, a man she’d never met, to secure an alliance with France.”

There is a temptation in monarchy. There is an entirely understandable sense that uniting behind a single man is right, particularly if that man has divine right, and if you do that man will fight for you. But no one can be trusted with such power. They would, eventually, be corrupted or be replaced by those who became corrupted themselves. Those people do not fight for you. They fight for themselves.

And now you’ve read this far, I have a request to make.

It’s growing harder to make a living through self-published writing these days. If you liked this book, please leave a review where you found it, share the link, let your friends know (etc, etc). Every little helps (particularly reviews).

Thank you.

Christopher G. Nuttall

Edinburgh, 2021

June 26, 2021

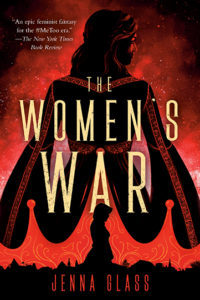

Book Review: The Women’s War

The Women’s War

-Jenna Glass

The spell they were set to cast tonight had been generations in the making, built by a succession of gifted abbesses who’d seen what no one else had seen—and who’d had the courage to act on it. It was well known that magical aptitude ran in certain families. In the Abbeys, it was similarly well known that the rarer feminine gift of foresight also ran in families, though only women who inherited that gift from both sides of their families could use it. And so the abbesses of Aaltah had set about manipulating bloodlines based on what they saw, strengthening and concentrating the abilities they needed. A love potion slipped into a client’s drink. A contraceptive potion withheld. A marriage falsely predicted to be unfruitful when the bloodlines were analyzed . . . The fate of the world rested on these small acts of feminine defiance.

Brynna Rah-Malrye had completed the process by bearing Nadeen and breeding her with that repulsive Nandel princeling to produce Vondeen. Generations had labored to produce these three women—the virgin, the mother, and the crone—who were the only ones who could complete this epic spell.

There was no turning back, no matter how high the cost or how much it hurt.

By a rather curious coincidence, shortly before I cracked open The Women’s War I read a biography of King Richard II, who – while hardly the worst person to park his rump on England’s throne – was a mess of insecurity and paranoia that led him to make an endless series of unforced errors that eventually resulted in his cousin invading the country, then overthrowing and murdering Richard before taking the crown as Henry IV. It is hard not to look at Richard’s career and think he must have been driven by his own personal demons, because many of his decisions were practically suicidal. Given his early life, it would be odd indeed if the adult was not shaped by the experiences of the child, but – when that adult sat upon a throne – his shortcomings became incredibly dangerous. Richard was nowhere near as unpleasant as Delnamal, the main antagonist of The Women’s War, yet I cannot help wondering if he was the major inspiration. If there was a wrong decision to be made, Richard (and Delnamal) made it.

The Women’s War is set in a fantasy world that clearly draws inspiration from medieval Europe (with some major differences, which will be discussed below.) Magic is a constant presence, with magical elements that are male-only, female-only and both-genders. Female magic is regarded as lesser and largely forbidden, outside the Abbeys of the Unwanted; women, in short, are regarded as little more than chattel, treated as property by their male guardians. A woman can be sent to the Abbeys on a whim, where she will be pushed into de facto prostitution. Marriages are arranged, at least amongst the nobility, for political reasons; a wife who fails to give her husband a (male) heir runs the risk of being discarded at any moment. It is, in short, a no woman’s land.

Everything changes when a handful of women, led by the Abbess of the local Abbey, enact a ritual to tamper with the source of magic itself. All of a sudden, women have access to far more – and different – magics, starting with a shift in reality that allows a woman to automatically terminate an unwanted pregnancy. As the social and political implications start to sink in, and chaos spreads around the known world, the monarchy sends the surviving women into exile …only to discover, too late, that the exiles have stumbled into a wellspring of new magic, open largely (if not only) to women. They eventually turn it into a de facto kingdom of their own, posing a threat to the established order that may trump everything the kingdoms have yet seen.

The story is centred on three different characters. Alysoon Rai-Brynna, daughter of the king (her mother was put aside and sent to the Abbey, allowing her father to marry again), finds herself wrestling with the changed magic and trying to save her own daughters from the wrath of their uncle; Princess Ellinsoltah of a different kingdom finds herself unexpectedly on the throne when everyone above her dies in an accident, then caught in plots hatched by older and more cunning (and masculine) advisors; Delnamal, half-brother to Alysoon, starts to plunge into madness as he loses his unborn child, his hated wife starts plotting against him, his father dies, leaving him on the throne. The three characters, and a handful of relatively minor ones, interact repeatedly, each clash triggering off the next stage of the plot.

Alysoon is something of an atypical character, being a widow and mother in her late forties when the world changes. She is curiously naive as a character, unable to anticipate that her mother would have told the world what she’d done (which was obvious, as otherwise the truth might not be realised until it was too late); she is reluctant to step into the light as the eventual de facto leader of the new community; she is, perhaps worst of all, unable to see the person under her prim and proper daughter until it is too late. Ellinsoltah is a little more conventional, slowly growing into her new role; she makes mistakes, some of which come very close to destroying her, but she eventually secures her position. Delnamal is perhaps the most conventional of the three, and a type we’ve seen before in many earlier works, yet he’s not entirely without reason. Jenna Glass does not make excuses for him, and rightly so, but she does help us to understand him. A person who is dealing with a colossal personal crisis, even one brought on by his own failings, is not going to respond well to hectoring from outsiders.

The Women’s War is not blind to the problems caused by the sudden change in the world, although – as all three major characters are royalty – it is hard to see what, if any, effects the crisis has on the commoners. The sudden loss of a number of unborn children is obviously disastrous, as is the realisation altar diplomatic will have to be radically altered. As more and more newer magic spells start to make their emergence, including spells designed to render someone important or even kill them outright, the world continues to change. Spells designed to prevent pregnancy can and do liberate women, allowing them to have sex outside wedlock, but this isn’t a cure-all. Ellinsoltah discovers, very quickly, that she has traded one problem for another when she consummates her relationship with her lover and this, eventually, nearly unseats her.

It also allows women – and men – to continue research into magic, assessing how the change worked, what the shift allows people to do now, and – for some – trying to figure out a way to reverse the change. This is one of the more interesting parts of the book, although it does raise the question of precisely why no one thought to investigate female magic more closelybeforehand. The power to heal is also the power to kill and the implications should have been obvious.

The book does, however, have its weaknesses. On a small scale, Alysoon’s daughter seems to jump around a lot in the last few chapters, resulting in a shock ending that feels more than a little contrived. Delnamal’s development as a character also jumps around a lot, leaving him veering between trying to come to grips with the crisis, then trying to tackle his insecurities, then finally jumping right off the slippery slope. At times, Delnamal comes across as an indecisive actor, at one point convincing himself that horrific things have to be done and, at others, regretting them the instant it is too late to deal with them.

On a larger scale, the treatment of women and firstborn heirs is largely allohistorical; it wasn’t uncommon for unwanted royal and aristocratic women to be sent to convents, just to keep them out of the way, but they were hardly turned into prostitutes. Nor was it something done on a whim. A king who disowned his foreign-born wife because he wanted a son, as Henry VIII did, would have found it harder to find a suitable replacement as the new wife’s family would suspect the relationship wouldn’t last long enough to put their child on the throne. A firstborn heir would be almost impossible to put aside, as it would call into question the very basis of the monarchy. (Note that Jane Seymour, mother of Edward VI, died shortly after childbirth; she wasn’t discarded by her husband.) Delnamal’s father would be unlikely to put his firstborn aside in Delnamal’s favour, even before Delnamal’s character flaws became apparent. The former heir would become a civil war waiting to happen.

(This, for example, is probably why Elsa and Anna’s parents didn’t quietly take Elsa out of the line of succession, even though it might have been the best possible thing to do.)

The Women’s War has been called ‘fantasy for the #METOO era.’ This is something of an exaggeration. It is set in a world that is very different from our current era and still quite different to anything that existed in the past. It presents issues that are not entirely contingent with ours. It avoids some issues that need to be assessed and raises issues that work in the book’s context, but don’t work outside it. And, in places, the author stacks the deck. The heroines have a powerful male ally, in Alysoon’s older brother, but if things had been different – for him – he might be on the other side.

The book is not like The Power or Farnham’s Freehold, where modern society is flipped upside down, nor set ten or so years after the change like The Philosopher’s Flight. It has less to teach and illustrate for us than more contemporary books. But, as a story set in a changing world, it works fairly well.

You can download a free sample from the author’s website here. However, outside the US, the book is only available in hardback or paperback.

June 24, 2021

Why Boys Don’t Read (Enough)

Why Boys Don’t Read (Enough)

OK, true story.

Back in 2003, I graduated as a librarian and set out on what I hoped would be a climb to the top of the field. (Spoiler alert – it wasn’t.) As I waited for my final exam results, I set out on a series of job interviews at various schools and universities around Greater Manchester, one of which remained stuck in my mind. The interviewers asked what I’d do to encourage kids to read. And my answer was that I would offer books that were popular at the time – the example I used was Harry Potter – so kids would read books they like and thus develop the reading muscles they need to move on to other, more advanced, books. I even suggested that the kids should be allowed to nominate library books for purchase, on the grounds they were the ones the kids actually liked.

This answer did not go down too well with them. They seemed to think I should choose books based on their literary merit. They found the idea of selecting books based on the likes and dislikes of a handful of kids to be wrong-headed, perhaps even counter-productive. As you have probably guessed, I didn’t get the job.

But I still stand by my answer. If you want kids to read, or do anything really, you have to present them with books that actually encourage them to read.

A few weeks back, a friend of mind pointed me to an article entitled ‘Boys Don’t Read Enough.’ The general gist of the article is that girls do better at reading than boys and it tries to offer a handful of explanations, but none of them are particularly convincing. They tend, I think, to avoid the fundamental problem. Adults are not children and therefore adults have a skewed idea of what children actually read. Nor do they understand that children, even the cleverest of children, have a very limited mindset.

You can argue, for example, that Charlie and the Chocolate Factory defended slavery. An adult might argue that the Oompa-Loompas are effectively slaves, and (at least originally) racist stereotypes. A child wouldn’t know or care about the underlying issues – his mind would, hopefully, be swept into a world of wonder and mystery that combines chocolate with the sense that bad people get what they deserve. (He wouldn’t care about the fridge horror in the fates of the four bratty kids either.) Or you could argue that Dumbledore is a very dodgy character indeed in Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (he left a one-year-old on a doorstep, for crying out loud) and the Dursleys are, at best, neglectful and, at worst, outright abusive. Again, a child wouldn’t care about such details. The whole story is more about a young boy who steps into a whole new world.

One can also argue, if one wishes, that these books have little literary merit. But that doesn’t matter. The point is that the books appeal to kids.

But, throughout my schooling, I was frequently forced to read books that bored me, irritated me or generally frustrated me. Bill’s New Frock was supposed, I believe, to teach us boys how different life was for girls. I found it boring and silly. Stone Cold was depressing as hell, as was Brother in the Land. Oliver Twist (the condensed version) was interesting, but it was hard to draw a line between myself and Oliver. The further the gap between me and the characters, the harder it was to feel for them. Z for Zachariah started well, but grew harder to follow as the story progressed. I’m not sure why I felt that way, at the time. I do wonder, in hindsight, if it had something to do with the main character growing more and more feminine before things went to hell. As an adult, I don’t blame her for crushing on the newcomer and considering marriage; as a child, it was just tedious.

In some ways, I think that is an issue. My mother had an old Girl Guide Annual I used to read. The stories I liked best were the ones the heroine could be swapped out for a hero without severely altering the plot. It’s easy to say that stories about people who are different promote empathy, and perhaps they do, but it’s also easy to turn those stories into moralistic bore-fests. It doesn’t help, I think, when people feel forced to read them.

I think, judging by my experience, that young boys want exciting stories of action and adventure, not tedious lectures or inappropriate morality. It is easy to blame Enid Blyton for not living up to modern-day standards on everything from race to gender roles, but Blyton died in 1968! Her books are often simplistic and, looking back at them, it is clear there were aspects that could have been reasonably criticized even at the time. And yet, what does that matter to a young reader? Blyton’s stories have clear heroes and clear villains and even the more complex ones are still quite simplistic at heart. They draw readers into their world in ways few modern stories can match.

Nor does it help when people over-think such matters. Reams of paper and ink have been wasted debating ‘the problem of Susan,’ in which Susan Pensive is denied heaven for growing up, embracing her adult life and doing her best to forget Narnia. Lewis is condemned for this by people who think too much and yet too little. On one hand, Susan is not in heaven for the very simple reason she’s not actually dead! On the other, more thoughtfully, the Narnia books were written for young boys and Susan, from the perspective of the target audience, is actually the least interesting female character. She occupies the role of older sister, mother-figure without actually being the mother; she’s the kind of person a young boy would regard as boring, if not an outright opponent. She’s neither the tomboy-type (like Lucy and Jill) nor the fascinating enemy (like Jadis). She just is.

If you want young boys to read, you have to offer them books keyed to their interests and tastes – their real interests, not the interests you think they should have. And that means acknowledging, right from the start, that those interests will be different from both young girls and adults of both genders. Do not force them to read books that bore them, annoy them, or slander them. Let them shape their reading habits so they develop their reading muscles, then proceed onwards to more meatier works. I look back at some of the stuff I read as a kid and I roll my eyes. Did I really read that crap? Yes. I did. And it helped me develop the skills to read more.

If you want boys to read, give them books they want to read.

OUT NOW – The Zero Secret (The Zero Enigma X)

A thousand years ago, an empire died. No one knew why. Not until now.

Seven years ago, Caitlyn “Cat” Aguirre – the first of the magicless Zeros – was kidnapped and taken to the ruins of the Eternal City. There, she discovered the dread secret behind the collapse of the Thousand-Year Empire, a secret she knew she didn’t dare share with the world. But now, with strange sightings and energies emitting from the ruined city – and a darkening political situation back home – Cat has no choice, but to return to the dead city.

And what she finds there will change everything …

Download a FREE SAMPLE, then purchase from the links here: Amazon, Books2Read.

Also, download Fantastic Schools III, featuring a whole new Schooled in Magic tale, from Kindle Unlimited HERE.

June 21, 2021

Snippet – The Prince’s War

Prologue

From: An Unbiased History of the Imperial Royal Family. Professor Leo Caesius. Avalon. 206PE.

It is extremely difficult to trace the history of the Imperial Royal Family – as it became known – past the final stages of the disintegration and the early days of the Unification Wars. Part of this, of course, is an inevitable result of the wars and their attendant devastation; a great many records were lost and/or deliberately destroyed during the fighting. Certain factions, particularly during the opening stages of the conflict, believed that it would be better to erase the past so the human race could stride forward into a brave new future, and therefore set out to capture or destroy as many records as possible. Others simply ignored the danger of historical erasure, and revisionism, until it was too late.

But a far more significant problem was caused by the newborn Imperial Household’s determination to legitimatise its position. There were no shortage of academics willing to take thirty pieces of silver – or, more practically, lands and titles – in exchange for creating largely or entirely fictional genealogies for their patrons to use as propaganda. The results were quite remarkable. The First Emperor was hailed as the direct descendent of such figures as Alexander the Great, Augustus Caesar, Elizabeth Tudor and many others, ranging from Albert Einstein to George Washington and Joe Buckley. Links were drawn between him and nearly every figure of consequence, to a truly absurd degree. He was not only the sole heir to every kingdom on Old Earth, but also lands that simply never existed, including little known fictional kingdoms such as Gondar, Narnia and Wakanda.

This had two unfortunate – and entirely predictable – effects on academic enquiry. An unwary student, more intent on getting a good grade rather than actually think about the material in front of him, might not notice the inconsistencies and frank impossibilities, such as a marriage between Queen Elizabeth Tudor of England (1533-1603, PSE) and Shaka Zulu (1787-1828, PSE), a marriage that would have been unlikely even if the two hadn’t lived and died nearly two hundred years apart. A more perceptive student, on the other hand, might realise there were just too many discrepancies to be accidental and come to the conclusion that the whole field was irredeemably damaged beyond repair. Such students would either leave of their own accord or, if they alienated their academic supervisors, would be pushed out or simply sidelined. The Imperial University’s administrators knew very well there were fields of enquiry that could not be touched, not without angering their patrons. What was the life of one student compared to the whole university?

Perversely, the truth is better than the fairy tale. The First Emperor – whose name was largely stricken from the records, to be replaced by a decidedly impersonal title – was a high-ranking military officer during the early years of the disintegration. Realising the endless wars were futile – his autobiography makes no mention of the burning ambition that was a mark of his career – he convinced a number of his fellows to mount a coup, seized control of the government and then embarked upon a series of increasingly sophisticated military campaigns to bring the rest of the settled worlds under his control. He was more than just a naval officer, it must be noted; his skill at convincing former opponents to join him, or at the very least not to oppose him, was quite remarkable. When he took the title of Emperor, he rewarded his followers by making them Grand Senators. They in turn rewrote history to make it appear they had always been part of the rightful ruling class.

Whatever else can be said about the First Emperor, he did his work well. By the time his son succeeded to the Imperial Throne, the empire was on a solid footing and could easily survive a handful of weak or clumsy rulers. There was enough of a balance of power, the ruling class felt, to ensure both a degree of stability and a certain amount of social mobility. It should have endured forever.

It did not. It took years – centuries – for decay to start to take hold, but it did. A trio of weak emperors allowed the Grand Senate to take more and more power for itself, then – worse – failed to play the different factions within the senate to right the balance of power. Social mobility slowed to a crawl, the successive emperors losing much of their influence as they were increasingly dominated by the aristocracy. Many of them lost themselves in mindless hedonism, whiling away the hours with wine, women, song and pleasures forbidden even to the aristocracy. The handful who tried to reclaim their birthright were swiftly slapped down by the new rulers of empire. Emperor Darren II was assassinated – it was blamed on terrorists, but the act was clearly ordered by the aristocracy – and Empress Lyudmila was held prisoner by her unwanted husband, then murdered when she produced a heir.

By the time the Empire entered its final days, the Imperial Throne was occupied – to all intents and purposes – by Prince Roland, known to the public as the Childe Roland. He was officially declared a great moral and spiritual leader, but the reality was somewhat different. Prince Roland – the Grand Senate hadn’t been able to decide on when he should be formally crowned – was, by the time he entered his teenage years, a useless layabout. The only good thing that could be said about him, it should be noted, was that he’d not fallen as far into depravity as some of his ancestors. It was generally believed that it was just a matter of time.

The Commandant of the Terran Marine Corps, in a desperate bid to turn the situation around, made use of the Corps’s long-held power to appoint bodyguards to the Imperial Household and assigned Specialist Belinda Lawson to take care of the prince and, hopefully, make a man out of him. She was rather more successful than one might expect, knocking some sense into the nearly-adult prince, but it was already too late. Earth collapsed into chaos and it was all Belinda could do, along with the prince, to escape. The Empire died and, as far as anyone outside the Corps knew, Prince Roland died with it. In reality, he was transferred to a Marine Corps starship.

This was, as far as the Corps was concerned, an awkward position. Roland was the legal ruler of the known galaxy. However, practically speaking, he ruled nothing. The Empire was dead and gone. The Corps could not recover even the Core Worlds, already blighted by civil war, let alone the rest of the settled worlds. Roland was an Emperor without an Empire; an unfinished young man who might be an asset but might equally become a burden. And that left the Corps with a serious problem.

What – exactly – were they going to do with Prince Roland?

Prologue II

Sarah Wilde awoke, in pain and darkness.

It wasn’t the first time she’d awoken in a strange place, her head throbbing as she tried to recollect what she’d been doing the previous evening. The sorority motto was practically “one evening in heaven, the next morning in hell” and she knew from bitter experience, after a year at Imperial University, that it was more than technically accurate. She and her peers had consumed vast amounts of everything from alcohol to mood-altering drunks in pursuit of mindless hedonism, all the while doing as little actual studying as they could get away with. It wasn’t as if the professors cared. Sarah had heard, from one of the more radical student activists, that the staff preferred their students to be zonked out of their minds. It kept them from considering how little they actually learnt at the university.

She kept her eyes closed as she quietly accessed the situation. She was lying on a hard stone floor … a relief, given how many times she’d woken up in a stranger’s bed. The air stank … she didn’t want to think about what it might be. Her clothes were rumpled, but in place. Her body was aching. Her wrists … a flash of alarm shot through her as she realised something cold and hard was wrapped around her wrists. Her hands were firmly bound behind her back … she heard someone moan, the sound far too close for comfort. Her eyes snapped open and she looked around in panic. She was in a cage, surrounded by cold metal bars. And she wasn’t alone.

Her memory returned in a flash. There’d been a protest march. She’d gone because it was the popular thing to do, not out of any real conviction. She didn’t understand the issues, nor did she really care. She’d joined the marchers and then … her memories were scattered, so badly jumped she wasn’t even sure they were in the right order. There’d been bangs and crashes and flashes of light so painful she’d thought she’d been blinded and then … and then nothing, until she’d woken up in a cell. Her heart sank as she looked from face to face. She didn’t recognise anyone within eyeshot, but they were all clearly in the same boat. They’d all been arrested.

Sarah swallowed, hard. It wouldn’t be that bad, she told herself. The cops would realise they’d made a mistake soon enough. She’d heard stories of being arrested, stories told by activists, that made it sound like a grand adventure. She heard someone being sick behind her, coughing and spitting to keep from choking on their own vomit. An adventure? She promised herself, numbly, that she’d never go to another protest march as long as she lived, not after she’d woken in a cell. The activists could find someone else to march in their protests.

Someone catcalled. She looked up and through the bars. There was another cage on the far side of a walkway, crammed with male prisoners. They looked savage … she shuddered helplessly, trying not to draw attention. The bars didn’t seem solid any longer. She lowered her head, wishing for water … wishing it was just a nightmare, wishing she could wake up in her own bed. She heard banging and crashing in the distance and forced herself to look, just in time to see two uniformed women marching towards them. They were banging their truncheons on the bars, waking the prisoners from their slumber. Sarah groaned in pain as the noise grew louder. She wanted – she needed – them to stop.

The women stopped in front of the cage and peered at the prisoners. “You,” the leader said, jabbing a finger at a girl in a tattered pink dress. “On your feet.”

The girl shook her head. “I want my lawyer.”

“Hah.” The guards laughed. “She wants a lawyer.”

Sarah opened her mouth to protest, but it was too late. The lead guard pointed a flashlight-like device at the protesting girl. Her entire body jerked, twisting unnaturally. She screamed in pain, then collapsed in a heap. Sarah stared in horror, unable to understand what had happened. It was … it was unthinkable. It was beyond her imagination. It was …

The guard pointed at her. “You. On your feet.”

Sarah forced herself to stand, despite her fear. The guard beckoned her forward, through the cage door, then shoved her down the corridor. Sarah tried to keep track of their movements, as they frogmarched her through a string of unmarked corridors and elevators that went up and down seemingly at random, but rapidly lost her bearings. It occurred to her she was being marched in circles, just to confuse her, although it seemed pointless. The building was just too big. She wondered numbly just where they actually were. She hadn’t seen any large police station within the university sector, not on any of the public maps. But she’d also been told there was a great deal that was never put on the terminals.

They shoved her into a small room and pushed her onto a stool, then stepped back. Sarah looked up and saw a man sitting behind a desk, his eyes on a terminal in front of him. He looked bored and harassed, his face suggesting he no longer gave a damn about his job or anything. She shivered, despite herself. She’d seen that expression before, on the maintenance staff who kept the university running. They seemed to loathe the students they served with a white-hot passion. She had always wondered why they didn’t look for better jobs elsewhere.

The man spoke in a bored monotone. “You have been convicted of public disorderliness, taking part in an unlicensed political rally and various other charges. Your appeal has been filed, reviewed and rejected. The original conviction stands. You have been sentenced to involuntary transportation.”

Sarah blinked. It was hard to follow his words, but … “I … I want a lawyer.”

“You have already been convicted,” the man said. His tone didn’t change. “You were caught in the performance of illegal activity. The state-appointed lawyer made a valiant attempt to defend you and your comrades, but the evidence was damning. The appeal was unsuccessful. You have been sentenced to …”

“I …” Sarah swallowed, hard. “It was … you can’t do this!”

“You were caught in the performance of illegal activity,” the man repeated. “You have been convicted.”

Sarah stared at him in shock. It … she’d heard rumours, sure, about what happened to people who stepped too far out of line, but she’d never taken them seriously. No one she knew really believed them. The police were a joke. It was …

The man didn’t wait for her to speak. “Your contract has been sold to the New Doncaster Development Corporation. You will be transported to New Doncaster shortly, once the remainder of the involuntary transportees have been processed. You may make a choice. As a young and presumably fertile woman, you may marry a farmer on the planet and assist him in developing his territory. If you agree to this, the corporation will forgive the debt you owe them. If you …”

Sarah found her voice. “I don’t owe them anything!”

“They bought out your contract,” the man said. “They own you.”

“You can’t own a person!” Sarah tried not to raise her voice, but it was hard. “Slavery was banned under the constitution …”

“You’re a convicted criminal,” the man said. “You have to pay your debt to society. The corporation has bought your contract and is offering you the chance to repay them …”

“By marrying a man I’ve never met and …” Sarah found it hard to put her thoughts into words. “It’s barbaric! My parents …”

“Are no longer part of the issue,” the man said. For the first time, she heard a hint of exasperation in his voice. “The corporation owns you. You can repay your debt, in the manner they suggest, and the slate will be wiped clean. Or you will find yourself on contract duty when you reach the planet, which could be anything from working in the fields to slaving in a brothel. You would be well-advised to accept their terms and strive to make it work. This is the one chance you’ll get.”

Sarah shook her head. “I’m not a slave!”

“The corporation owns you,” the man said. “Maybe you are not legally a slave. The fact remains they can treat you as one until you repay their debt. Choose.”

“I can’t …” Sarah tried to protest. “I don’t know …”

“Choose,” the man repeated. “I have no more time.”

Sarah pinched herself. Nothing happened. It was … it was a nightmare. She’d only gone to a protest march! It wasn’t as if she’d done something really wrong. And yet … she recalled hearing, somewhere, that Earth was so overpopulated that the sentence for just about anything was deportation, unless one had a really good lawyer. She wanted to demand her rights, as a free citizen, but … tears prickled in her eyes as she realised she wasn’t a free citizen any longer. She was property. She’d been sold to the highest bidder. Her family would never see her again. Would they ever know what had happened to her? Would they try to come looking? Or would they simply wind up arrested and deported themselves? Or …

Cold anger burnt through her as she gathered herself. She’d survive, she vowed. She’d build a new life for herself … no, she’d make the corporation regret it had ever enslaved her. She’d make it pay, even if it cost her everything. She’d make it pay.

“Very well,” she said. She needed to play dumb, for a while, until she knew what was really going on. And then she’d find a way to take advantage. “I’ll do as the corporation says.”

And then, her thoughts added silently, I’ll make them pay.

Chapter One

Marine Boot Camp, Merlin

The woods were dark, oppressive.

Roland, once Prince Roland of Earth and now Receipt Roland Windsor of the 7th Training Regiment, kept his head down as the squad picked their way through the trees. Visibility was terrifyingly variable, streams of light broken by pools of shadow that made a mockery of his enhanced eyes. The trees were large enough to conceal infantrymen below, their branches easily big enough to host a sniper or two. He swept his rifle from side to side, all too aware the enemy could be lurking anywhere. The mission had to be completed successfully. He wanted – he needed – to progress. He couldn’t go to the Slaughterhouse until he convinced his instructors that he could become a full-fledged marine.

Take it seriously, he told himself, sharply. You don’t want to get into shit because you were woolgathering when you needed to watch for trouble.

He inched around a tree, then darted to the next one. The mission was relatively simple, they’d been told, but the simplest things were often the most complex. The training company – broken down into squads – had to make its way through the forest, flushing out the enemy positions before they could rally and counterattack. Roland was tempted to wonder if they’d been sent on a wild goose chase – he’d heard shooting, yet they hadn’t seen the enemy – but he knew better. The fact the enemy hadn’t greeted them with a hail of fire was almost certainly a bad sign. They were probably dug in somewhere further into the forest, waiting for the recruits to stumble into their trap. Roland cursed under his breath as he paused, listening carefully for the slightest hint of movement. It was hard to be sure. The local wildlife was just too loud. A drunkard could pass unnoticed against the din.

Goddamned insects, he thought. He wasn’t sure who’d thought to introduce the tiny bugs to the training ground, but it was a stroke of evil genius. The clattering bugs provided all the sonic cover a hidden enemy force could want. If only we could get rid of them,

Recruit Walsh stepped up beside him, her face pale. Roland glanced at her, then held up a hand to signify she should remain behind as the rest of the squad advanced. They were dangerously spread out, and he was tempted to suggest they closed up, but he knew it would be asking for trouble. Their uniforms were supposed to make it hard for the enemy to detect them, yet hard wasn’t the same as impossible. A single drone, orbiting so far above them even his enhanced eyes couldn’t see it, would be enough to call fire down on their heads, if they slipped up and showed themselves. Better to remain spread out until they knew where there targets actually were. He nodded to the others, then resumed the advance. If he drew fire himself …

Nothing happened. The treeline remained quiet. Roland frowned. He wouldn’t be happy if someone hit him – the instructors would be very sarcastic, even if he hadn’t fucked up – but the rest of the squad could unleash hell on their opponents. It would be better to know the worst at once, he thought, rather than remain in ignorance of the enemy positions. The training ground was huge, easily large enough for an entire army to remain hidden if it wished. Roland kept his eyes open as the squad moved up to join him, but there was nothing. It was all too easy to believe they were completely alone.

Or we’re lost, which puts us on track for promotion to lieutenant and a court-martial, he thought, with a flicker of amusement. He’d no idea why so many marines seemed to believe their lieutenants couldn’t read maps – his first exercise in map-reading had been a disaster, yet he’d gotten better at it with practice – but it didn’t matter. There’s no way we can simply march out of the training ground and get hopelessly lost.

The squad continued to advance, pushing through the trees and avoiding the handful of half-baked trails within the woods. Roland couldn’t tell if they’d been made by animals or humans, although they’d been taught to stay off the paths as much as possible. A smart enemy would have their mortars already zeroed on the path, ready to unleash hell the moment their targets came into view. Unless … sweat continued to trickle down his back as the trees opened suddenly, revealing a grassy valley with a farmhouse and a pair of barns at the bottom. It looked deserted, but that was meaningless. The enemy could be using it as a base. They had to clear it before they continued the advance.

He glanced at the rest of the squad, then led the way forward at a run. Their uniforms were designed to provide a certain amount of concealment, but he’d been cautioned not to rely on it. The human eye was attracted to movement, even if it couldn’t make out what was actually moving. Roland had heard cautionary tales of defenders who’d been so keyed up they’d fired at shadows. He’d thought the stories were absurd until he’d been on guard duty himself. It had worn him down so much he’d nearly fired on a friendly convoy. And that would have landed him in real trouble.

Roland reached the side of the farmhouse, unhooked a flashbang from his belt and hurled it through the window, looking away as the grenade detonated. The flashbangs weren’t actually lethal, at least under normal circumstances, but anyone caught in the blast would be too busy projectile vomiting or trying not to collapse to worry about the intruders. He counted to five, then allowed Walsh to heft him up and through the window. He landed neatly, weapon raised and ready. The room was deserted. There weren’t even any tripwires that might be linked to IEDs or other surprises. He frowned as the rest of the squad joined him, then carefully led the way through the rest of the house. It looked oddly polished, for a building in the middle of a training ground. That worried him, although he wasn’t sure why. The corps was known for its attention to detail. The instructors would have gone to some trouble to make sure the building looked as though it had been abandoned in a hurry.

“Search the barns,” he ordered, as they completed their sweep and hurried outside. “Quickly.”

His heart pounded as they glided through the remainder of the farm. The farmhouse was nice and rustic, but it might also be a trap. They hadn’t had time to search it thoroughly. He checked his threat detector and saw nothing, but it wasn’t reassuring. There was an ongoing war between the techs who designed early warning and detection technology and the insurgents who tried to come up with ways to fool it. It was quite possible they’d missed something. The instructors were ruthlessly pessimistic. If there was even a slightest chance someone would be hit, they’d be hit. There was no room for the luck of the draw on the training ground.

Hard training, easy mission, Roland quoted, silently. Easy training, get the shit kicked out of you on a real mission.

Recruit Singh caught his eye. “It’s clear, sir.”

Roland nodded, turning his eyes towards the far side of the valley. Anything could be hidden within the trees, anything at all. He was tempted to call in and ask for support, perhaps even an update from the drones, but he knew it would be pointless. They’d been cautioned not to risk any sort of contact until they encountered the enemy, just in case. His superiors would not be amused if he risked contact just because he needed his hand held. They’d be very sarcastic.

He scowled as the squad prepared to resume the advance. His fellow recruits didn’t know him as anything other than Roland Windsor, a young recruit keen to be the best of the best, but his instructors knew who he’d been, only a few short months ago. Roland didn’t blame them, not really, for having their doubts about him. He looked back at himself when he’d been the Childe Roland, Heir to the Imperial Throne of Earth, and violently cringed. He’d been a spoilt little brat, a mindless pleasure-seeker who’d drunk and drugged himself constantly just to starve off the boredom of life … he shuddered when he remembered everything he’d done, to people who didn’t dare say no. He’d been trapped in a gilded cage and he hadn’t even known it, not then. He’d been a puppet who couldn’t even see the strings!

His eyes swept the distant hills, although his thoughts were elsewhere. Specialist Belinda Lawson, a Marine Pathfinder, had saved his life and soul. She’d swept into his palace and transformed his life, knocking some sense into his head … too late to save the planet, perhaps, but not too late to make a man out of him, Shame swept over him as he remembered how he’d tried to get her into bed, as if she’d be interested in a overweight princeling who could barely lift his own weight. And she was dead … or worse. His superiors – his new superiors -hadn’t been entirely clear on what had happened to her, but he feared the worst. She would have come to see him, wouldn’t she? He wanted to believe she would have come.

Perhaps you were just another assignment to her, his thoughts pointed out. You were surrounded by people who were paid to keep you happy and dumb, people who didn’t give a shit about you. She might not have given a shit about you either.

He tensed, suddenly, as he heard the sound of rotor blades in the distance. A helicopter swept low over the hills, heading straight towards them. Roland swore as he saw the weapon pods hanging under its stubby wings; antitank rockets and heavy machine guns that would punch through his body armour as though it wasn’t even there. The training brief hadn’t mentioned helicopters … not directly, at least. The instructors had a habit of throwing unpleasant surprises into the mix, just to make sure the recruits knew their intelligence, no matter how much the spooks vouched for it, couldn’t be taken for granted.

“Take cover,” he shouted. “Hurry!”

The sound grew louder as he hurled himself into a ditch, near the farmhouse. His mind raced as he saw Walsh take up position near the treeline. The farmhouse might have been a trap after all, although not in the way he’d thought. There could be someone on the hillside with a low-tech telescope, linked to a simple telephone line … he sucked in his breath. His instructors had warned him, time and time again, that just because something was outdated didn’t mean it was useless. A pre-space telescope and telephone wire would be pretty much impossible to detect unless the marines got lucky.

He stayed very still as the helicopter thundered over the valley, the rotors chopping through the air. Insurgents had learnt to fear the ugly aircraft a long time ago, all too aware the pilots could rain down death on them from overhead in relative safety. It took a great deal of luck to take down a helicopter without MANPADs or other heavy weapons, luck the umpires wouldn’t grant in a training exercise. Roland gritted his teeth, hoping the helicopter pilot would assume they’d gotten into the treeline before the aircraft got into position. Between the camouflage and the local wildlife confusing the craft’s sensors, they might just get lucky.

They know we can’t have gotten that far away, he thought. It didn’t look as though the helicopter was carrying a squad of troops, but appearances could be misleading. The aircraft was big enough to carry six or seven men in addition to the pilot and gunners, if they didn’t mind getting very friendly. Roland himself had been crammed into tiny aircraft with his peers several times, during the last few months. And they might think they have us pinned down …

The helicopter fired a machine gun burst into the trees. Roland frowned, unsure what the gunner had seen. None of the shells had gone anywhere near the recruits, not unless he’d misjudged where the other two had hidden. Perhaps they’d seen a fox or something move and fired on instinct or … perhaps they were just trying to intimidate the recruits. It might work out for them. Roland didn’t dare move, which meant they’d be pinned down right until the exercise ended or they were caught by the bad guys and humiliated … he peered towards the treeline, wondering if there was already a line of enemy troops moving towards them. It wasn’t as if they had to worry about being seen.

He frowned. He could hit the helicopter with a rifle-launched grenade, if he could get up and take aim before the craft blew him to atoms. But … he didn’t have time. Roland knew, without false modesty, that he was one of the fastest gunners in the training company and even he didn’t have enough time to take out the helicopter, not unless something happened to divert its attention. His mind churned. He needed a diversion. If he did nothing, they were screwed.

A plan occurred to him. He put it into action before he could think better of it. He signalled Walsh, instructing her to send a microburst message to their superiors. The messages were supposed to be undetectable and untraceable, but he knew the helicopter would have the very latest in detection gear, manned by people who knew precisely what to look for. The aircraft rotated rapidly, bringing its machine guns to bear on Walsh. Roland didn’t hesitate. He rolled over, slotted the grenade into place and fired it at the helicopter. It went through the gunner’s hatch and detonated inside. A moment later, the helicopter rose into the sky and vanished.

Got you, Roland thought. The boot camp was supposed to be realistic, but even his instructors drew the line at using real bullets and grenades. The helicopter was officially dead now and would remain so until the exercise terminated. You’ll be buying the drinks when we finally get some leave …

He tried not to feel guilty as he stumbled to his feet and looked at Walsh. She wasn’t dead, of course, but her training suit had locked up. She would remain immobile until the exercise ended or, depending on timing, the umpires collected her and put her on the sidelines. She’d be hopping mad afterwards, Roland reflected as the other two joined him. He promised himself he’d make it up to her, if he could. He would almost sooner have preferred to be ‘killed’ himself. At least he would have volunteered to serve as a human sacrifice.

There was no time to discuss it with her, he told himself, firmly. She’ll understand.

He gritted his teeth as they resumed their march through the trees. He’d been told, when he’d been a child, that it was his duty to look after the empire as a whole, rather than the individual people within it. He hadn’t realised, until much later, that it was a form of manipulation, that one could justify almost anything by insisting it was for the good of the empire. What was a single life compared to the uncountable trillions who made up the empire as a whole? It was nothing more than a number, perhaps even a rounding error. It was hard to argue that a single life mattered …

And yet, Walsh was a friend. He knew her. He knew she’d had hopes and dreams of her own before Earthfall. He knew she wanted to be a marine, that she’d joined the training company in hopes of making it to the Slaughterhouse. She was a living breathing person, a friend and a rival, a comrade and an enemy … no, never an enemy. They might have been on opposing teams, from time to time, but they weren’t enemies. He respected her and the rest of the company in a way he’d never respected anyone, back when he’d been the Childe Roland. And she was going to be mad at him in the aftermath of the exercise. She was probably going to punch him in the face.

Which is no more than you deserve, his thoughts mocked him. If someone had done that to him, without his permission, he would have been livid. Belinda would probably have kicked you in the nuts. It was bad enough when you tried to cop a feel …

He pushed that thought out of his mind and forced himself to keep going, heading towards the enemy position. Time was running out. They had to flush the enemy out before the umpires called a halt, before … he wondered if he’d be ordered to retake the training section again. He’d done some sections of boot camp twice now, at the whim of his superiors. Roland wasn’t sure if they were testing his patience, if they thought he’d tell them he wanted to quit if they didn’t let him complete boot camp and advance to the Slaughterhouse, or if they just wanted to be sure he knew everything he needed before it was too late. The Slaughterhouse was the final test, as far as the corps were concerned. And he was damned if he was failing. He owed it to Belinda to succeed.

Singh made a gesture as he peered around a tree. Enemy in sight.

Roland nodded, pushing his thoughts and doubts aside. They’d located the enemy lines. It was time to make war. He’d worry about the rest afterwards …

… And yet, as he braced himself for the advance, he couldn’t help wondering if he really had what it took to become a marine.

June 19, 2021

Weird Story Idea

So …

There are some kids who go to magic school in an alternate dimension – think Whitehall rather than Hogwarts. Something goes spectacularly wrong and they find themselves dumped on Earth instead. The good news is that they have magic still; the bad news is that they don’t have enough to reopen the portal and get back home. They get very lost until they discover, through one of their friends, that they can tap the electric power grid to power their spells and reopen the portal.

(I have the vague idea that the school’s alpha-bitch will be knocked down a peg or two because her magic is greatly reduced in our world, leaving the harder-working students with an edge.)

The discovery brings forth a new threat – a gang of rogue wizards on Earth, who have been secretly preparing an invasion of the magic world (they’re responsible for the portal accident, indirectly), and they try to stop the kids.

How does that sound?

Chris

June 18, 2021

Stuck in Magic 29-30

Chapter Twenty-Nine

“Well, at least they’re not demanding we give back the castle to a dead man,” Rupert said, an hour later. We’d spent the time dictating messages to Fallon, then listening as she repeated their messages back to us. “That would have been awkward.”

I grinned. Fallon giggled. The city fathers had been shocked, according to her, when they heard what we’d done. They hadn’t even realised we’d continued the offensive, even though it had been part of the plan. Going on until we hit something so hard we had to stop made perfect sense, as far as I was concerned, and we’d kept going until we won the war. Warlord Aldred’s former subordinates might try to declare independence, or try to offer homage to another warlord, but it didn’t matter. Right now, they lacked the firepower to do more than irritate us. The rebel serfs would keep them penned up until we could smash their castles one by one. Kuat had fallen. I had no doubt the others would be even easier to destroy.

Rupert smiled, tiredly. “We still have orders to wait for the princess,” he said. “By then, hopefully, the council will have decided what they want us to say to her.”

“They do keep changing their minds,” Fallon agreed. She glanced at the parchment. “Right now, they’re asking about securing our new territories.”

I unfurled a map and studied it thoughtfully. “We’ll position scouts along the roads leading to the neighbouring warlord territories,” I said. The nightmare was a united advance on multiple fronts, perhaps three or four armies heading straight to the city, but I doubted the warlords would manage to coordinate such an offensive. They’d need to build a modern army first, giving us time to tighten our defences and send more agents into their lands. “If they start an attack, we’ll know about it.”

Fallon wrote a message on her parchment. I felt a shiver running down my spine as the words faded and vanished, as if they’d never been. I’d never had that reaction to radios or computers … I frowned as Fallon read the reply out loud. To my eyes, the chat parchment was blank. It was hard not to feel we were being conned. We’d busted an insurgency cell, back in the Middle East, whose leader had faked messages from a multinational network to keep his subordinates in the fight. I knew Fallon wasn’t lying to us and yet it was hard to believe she could see something I couldn’t.

I turned my attention back to the map. “We’ll place a garrison here, just to make sure someone doesn’t try to take it from us, then split the army and deploy cannoneers to the rest of the castles. If they surrender, they can leave without a fight; if not, we can blow their walls down and they can die in the ruins. The quicker we eliminate them, the better.”

“The city fathers want you to detach half the army and send it back home,” Fallon said. “I think they’re getting worried.”

“We can do both,” I assured her. “And thank you.”

Fallon nodded, dropped a curtsey and hurried out the room. The communicators had taken over a handful of chambers, although personally I’d have preferred to keep them in the camp outside the walls. We were still searching the castle with the aid of the former servants, liberating prisoners from the cells, capturing records and logging every last item of value within the walls. The latter would probably have to be sent to the city, although I was pretty sure a number of smaller items had already been pocketed by my men. I sighed, inwardly. I didn’t want to encourage looting and yet … it wasn’t going to be easy to stop. Few, if any, people had qualms about stealing from a dead warlord. God knew he’d been stealing from everyone within his reach.

Rupert smiled at me, then winked. “She has a crush on you, you know.”

I scowled. It had been a long time since I’d lain with anyone and right now, in the flush of victory, my body was instant on reminding me just how long it had been. Fallon was young and pretty and … I cut off that line of thought before it could go any further. She was young enough to be my daughter, more or less, and she’d grown up in a society I didn’t really understand. It would be safer to visit an upper-class brothel, when I returned to the city, although that carried risks of its own. The last thing I wanted was a fantastical STD.

“I’m sure she’ll get over it,” I growled. I cleared my throat as I studied the map. “What do you think the princess actually wants?”

“Aldred wanted her to tell us to go home, disband our army and let him kick our backsides a few times,” Rupert said. We’d found the warlord’s private letters, along with everything else, when we’d searched his quarters. It was strange to realise that a man who’d had no qualms about twisting the king’s arm – he hadn’t been even remotely subtle about it – had also been a patron of the arts and a moderately gifted poet himself. “What she wants? I don’t know.”

I nodded as I turned my attention to organising the aftermath of the war. I didn’t really want to send a sizable chunk of the army home, even if they took a route that just happened to take them past a number of castles that needed to be reduced if they refused to surrender, but I didn’t have a choice. The city fathers had to be thinking we were dangerously loose cannons, although we’d won the war. They might not be openly churlish about it, not when public opinion would be firmly on our side, but they’d certainly do something to clip our wings. It was just possible they’d order us to concentrate on raising and training new recruits while giving combat commands to more reliable officers.

The hours went quickly. I checked the pile of captured gold – it looked like a dragon’s hoard – then arranged for it to be returned to the city under heavy guard. I allowed a detachment of former serfs to raid the warlord’s armoury, taking a few hundred swords, spears, crossbows and suits of armour that looked hopelessly outdated, along with thousands of arrows. It amused me to discover that the warlord had actually had his very own cannon, although he’d made no attempt to put it into service. The design was badly outdated, but it could still have hurled a cannonball into the city’s walls. I was sure his neighbours would be building up their own forces as fast as they could.

Fallon caught me as I returned to the castle, after inspecting the troops. “We have orders to send the aristocratic prisoners back to the city,” she said. “They want them back immediately.”

“I’ll see to it,” I said. The warlord’s wife, mistresses and remaining children had been kept under guard too. I wasn’t sure what, if anything, we could do with them. I didn’t want to execute them in cold blood and yet, leaving them alive would cause all sorts of problems in the future. “And then …”

She stopped as the chat parchment vibrated in her hand, more proof – if I’d needed it – that the original concept had come from my world. Or one very much like it. “Sir … the princess has been kidnapped!”

I blinked. “What?”