Christopher G. Nuttall's Blog, page 10

November 26, 2023

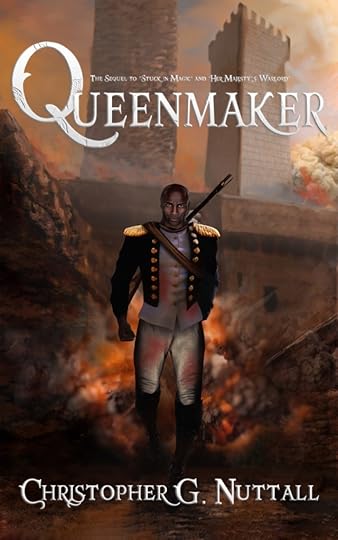

Preorder Now – Queenmaker (Stuck in Magic III)

There can be no peace, as long as a single warlord remains alive …

Elliot, Her Majesty’s Warlord, has been riding high. The coup against Queen Helen has been foiled, the New Model Army is readying itself for the coming war, and his lover is pregnant. But the warlords have been preparing too and now they’re on the march, ready to crush the kingdom and put the uppity commoners to the sword. Facing a war on three fronts, Elliot embarks on a desperate gamble to win the war in a single campaign …

… Unaware the warlords have plans of their own.

Download a FREE SAMPLE, then purchase from here.

Also, check out Guardians of the Twilight Lands: The Sixth Book of Unexpected Enlightenment – Out Now!

November 17, 2023

OUT NOW – Fantastic Schools Staff

Featuring a whole new Schooled in Magic novella …

You’ve met the students of magic schools, but what about the staff? What is it like to work in a magic school, to teach students and serve as their mentors and disciplinarians and everything else young minds need? We know their types … the headmasters – kindly or unpleasant; the teachers – friendly or cruel; the matrons and assistants and inspectors and janitors, all of whom have their own role to play beyond being characters in a student-themed story. But what is it like to be them?

Come meet a teacher trying to set up a whole new school, in the face of heavy opposition, and another who has to deal with a fairy infestation; meet a teacher who has a mission of his own and another who must take a stand against his own headmaster, for fear of letting the school be plunged into darkness …

Purchase HERE!

by Christopher G. Nuttall, J.F. Posthumus, Misha Burnett, Erin N.H. Furby, AC Young , Suzanne Gallagher, Frank B. Luke , Becky R. Jones, Declan Finn, Rhys Hughes

Book Review – The Armchair General World War One: Can You Win The Great War?

The Armchair General World War One: Can You Win The Great War?

by John Buckley, Spencer Jones

It is very easy, as I noted in my review of the first Armchair General book (covering the Second World War), to fall into trap of believing that the people on the spot, at the time, enjoyed the same luxury of hindsight as yourself. This is obviously untrue. We have a far more rounded picture of what was happening than anyone who was actually there; the fog of war, at the time, made it impossible for them to know what was actually going on. Many seemingly bizarre decisions make sense in this context, because they were made based on what the decision-maker knew at the time.

The Great War has not been a particularly big stomping ground for alternate history. The war does not seem to have so many possible points of divergence as its successor, not least because the initial war of movement gave way to stalemate until tanks were invented and put into mass production. The battles outside Europe did not have any great influence on the war as a whole. Germany lost colonies, of course, but assuming a German victory those colonies could be easily reclaimed. The forces involved were often very small, and their absence did not affect the overall balance of power. This could not be said of the Second World War, where the relatively small engagements in North Africa played a major role in defining the military balance in Europe.

In this book, the writers have attempted to put the reader in the shoes of people who made the decisions and present the facts to them as the POV character would have seen it. (Like I said before, this comes across as a choose your own adventure book.) You are invited to decide what you would have done, under the circumstances, and explore possible alternate outcomes for the war. These outcomes are kept within the bounds of possibility, without any striking alterations such as a German invasion of Britain or a complete collapse of Germany much earlier than in the original timeline. As such, it is a very interesting read.

The book starts by asking just how the original July Crisis of 1914 blew up and what might happen if the assassination did not take place, or if the United Kingdom stayed out of the war. It offers several possibilities for the assassination never taking place, and suggests it might lead to better world, but it also discusses the British decision not to take part in the war and speculates that the Germans might have won fairly quickly if the British stayed out. This might be true, but it would be seriously against British interests to allow one power to dominate Europe. It is also true that personal feelings played a role in the outcome and those should not be underestimated.

We then move on to look at the dispatch of the British Expeditionary Force to France and the alternate prospects of the campaign. Deploying to Belgium instead of France looked good on paper and was actually quite a popular decision with British officers didn’t like the French. There was also an urgent need to provide support to the Belgians before the Germans crushed them. The book suggests that such a deployment would have been disastrous, at least at first; there were no plans for joint operations with the Belgians and they were simply not prepared for modern war, forcing both British and Belgian forces to withdraw into France. The only positive outcome Britain would be a distraction for the Germans, ensuring they could not take Paris in 1914.

Even following the historical path leaves you open to other possibilities. Should you stand and fight when the Germans give chase to British, or should you keep going? There are good arguments for both, but choosing to continue the retreat would have been disastrous; the Germans would have overwhelmed the rearguard and crush the British Army before laying siege to Paris, almost certainly winning the war in 1914.

This campaign also led to personal clashes between British officers – the authors speculate that if Sir John French had been dismissed by Kitchener in 1914, he would have been able to challenge Kitchener later and get promoted into a position he was temperamentally unable to handle, leading to later disaster. His historical character assassination of his rival would in this case was a military disaster instead.

The book then moves on to Gallipoli, and asks what might happen if the campaign had taken place elsewhere. On paper, the Dardanelles appear to be a reasonable target, but there were others – most notably Alexandretta in Syria. There were political issues, as the French believed the region had been promised to them after the end of the war, but these problems could have been solved. The authors argue that a successful landing in Syria would have crippled the Ottoman Empire and driven it out of the war in 1915 – ironically, this would have ensured the survival of the Ottomans in some form, although quite how long for is impossible to say.

The book then assesses the different choices of the Dardanelles campaign itself, pointing out the dangers of forcing the straits and then landing troops in very difficult and exposed locations along the shore. Deciding to embark on a naval-only campaign would end poorly, if the Navy could not silence the Turkish guns (and it could not); the only chance of a quick victory in the campaign came with an immediate trust into enemy positions and if that attack failed it is unlikely the campaign would have been victorious (although it is possible British and Allied troops would have remained in the Dardanelles trenches until 1918).

We then move onto the Battle of Jutland, which the authors believe to have been largely insignificant. It was possible, they argue, for the British to score more hits (particularly in the opening moments of the battle, if the fifth battle squadron had remained with the battlecruisers) and if the British commander had acted without orders he might have played a decisive role in a clear British victory. It was also possible that the battleships could have risked charging into the German torpedoes, closing the range between both fleets; in that case, the authors argue, greater British numbers would have led to a more significant victory. However, as I mentioned above, the impact of the battle was unlikely to be decisive even if the British wiped out the German fleet completely; the authors appear to believe the Germans could not have scored a decisive victory of their own.

The book then assesses the potential alternate outcomes for the Battle of the Somme. There were possibilities that the battle might be a slow and grinding victory for the British, following a ‘bite and hold’ set of tactics that would drive the Germans out of their trenches, and then force them to make counter-attacks against dug-in British troops. The authors speculate that this would have been decisive in a tactical sense, but the weather would prevent any major collapse of the German lines and the war would continue at least into 1917. An alternate possibility involves tanks – should they have been deployed as soon as they were available, or should they have been held in reserve? The author speculates that the tanks would have been decisive, and even though there would still have been a muddy stalemate by the end of the year their deployment would have boosted French morale and led to greater victories the following year. The authors conclude that a truly decisive victory was unlikely, but a firm commitment to one plan for the battle might have led to a vastly different outcome.

The book then considers the possibilities surrounding Lawrence of Arabia and the Arab Revolt, starting with which Arab faction the British should back. Should they side with Hussein bin Ali or Ibn Saud? Both warlords have their strengths and weaknesses; Hussein has greater political skill and legitimacy, while Saud has an army of zealots who may be more militarily effective in the coming conflict. The book believes that a decision to support Saud instead of Hussein would have been a dangerous mistake, sparking off a Civil War within Arabic ranks and effectively ensuring they posed no threat to the Ottoman Empire. The book then considers possible disasters that could have overwhelmed the revolt, many of which would have ended the Arabs as a military useful force.

The writers then explore the dilemma facing the British code-breakers when they deciphered the Zimmermann Telegram. On paper, the decision to inform the Americans that the Germans were planning to ally with Mexico and Japan against the United States seems a no-brainer. In practice, there were a number of other considerations. The United States would not be pleased to know that diplomatic telegrams were being deciphered – and the Germans, of course, would be delighted to know that their codes being broken. Simply releasing the intelligence would unleash an international incident, not least because the Germans could simply insist the message was faked.

An alternate possibility, of course, is the telegram never being publicly disclosed. If that happened, there was a very real possibility of Mexico taking hostile steps against the United States. The preponderance of American power was bitterly resented in Mexico, and the prospect of nationalising foreign-owned businesses was very tempting. It is unlikely, the authors argue, that Mexico would actually declare war on United States, but there might be some hostility along the border might distract the United States from sending troops to Europe.

Finally, the book looks at the last great what-if of the period, the Russian Revolution, and identifies a number of possible points in which a different decision could have changed history. Could the Tsar be convinced to reach out to dissidents before it was too late? Or should he use force to crush the rebels before they gained momentum that will be impossible to stop? Should he sue for peace, when the war becomes too costly, or risk continuing the fighting until it takes him down? Even when the provisional government takes power, should it continue the war? The book argues that a German-Russian peace treaty in 1917 would have saved the provisional government from the Bolsheviks, not least by giving them the prestige they needed to crush the uprising, although this would cause long-term problems for Russia (not least because the peace treaty would be seen as a betrayal by Britain and France). On the other hand, it could hardly be worse than the original timeline. They would certainly avoid the disaster of Brest-Litovsk!

It also suggests that the Bolsheviks were right to make peace in 1917, even on deeply unfavourable terms. Continuing the war, after overthrowing provisional government because it wanted to continue the war, might well have led to a White Russian victory in the Civil War. This would not be an unmixed blessing. On one hand, the world would be spared the horrors of communism; on the other, the reactionaries would certainly try to crush the rebels and lay the seeds for future rebellions in later years. It is unlikely that Germany (with or without Hitler) would have become so powerful in this timeline, but a reactionary Russia would not be as capable of defending itself and eventually crushing the Nazi beast in Berlin.

Overall, as the authors try to remind us, history is driven by more than just impersonal forces and geopolitical realities. Some decisions were driven by what the decision-makers knew at the time, and what they thought they knew, and others were driven by personal feelings that rarely enter into the calculations of dispassionate alternate historians. On paper, some decisions looked very good indeed and yet, as the Dardanelles Campaign taught us, turning a concept into reality can be incredibly difficult. Other choices were driven by factors that are difficult, if not impossible, to account for: personality conflicts and faction in-fighting can change history, yet they can be frightening difficult to predict.

Relatively few decisions offer the prospect of a radically changed world, although that seems incredible. If the July Crisis never takes place, what will spark a major war? If Britain does not join the war, or is driven out of France in 1914, Europe will be dominated by Germany, changing history beyond repair. The Ottomans leaving the war early might convince other German allies that they can leave too; by contrast, if the Dardanelles were abandoned without a major commitment, the Ottoman victory would not appear so crushing and the peace factions might be able to put together a workable compromise. A major failure in Arabia might not be that significant, at least immediately, but it would have an effect on the post-war world. So too would be America staying out of the war, or Russia trying to stay in it longer than OTL.

These points are disputable, of course. There’s plenty of room for speculation about what might happen if something had been different. But overall, this is a fresh look at the realities facing the decision-makers of the First World War and the limitations they had to overcome to win. It demands a great deal of commitment from its readers, but I do not feel that you will consider the time wasted if you’re interested in the war.

November 2, 2023

Snippet – The Forsaken (The Empire’s Corps)

Prologue I – Earth, 101 Years Prior to Earthfall

I am not a supplicant, President Martin Lopez told himself.

Sure, his own thoughts answered. And if you tell yourself that often enough, perhaps you’ll even come to believe it.

He stood in the antechamber and waited, trying to keep his angry and despair from showing on his face. The chamber was vast, large and ornate and completely inpersonal, designed to make any mere human feel small and weak before the majesty of the Imperial Supreme Court. There were no table or chairs, nothing to make him feel welcome; his staff – his assistants and lawyers and even his mistress – had been denied permission to accompany him, leaving him completely alone as he faced his judges. No, his planet’s judges. Martin wanted to believe they still had a chance, but it was growing increasingly clear the fix was in. It had been in well before he’d left his homeworld to plead its case on Earth …

It was hard, so hard, to remain calm. If only … he kicked himself, not for the first time, for allowing the planetary survey. There had been no reason to think Montezuma had extensive mineral reserves, certainly nothing that might be of interest to offworld minding corporations. Oil and gas were great for planetary development, but it was hardly economically beneficial to ship them across the stars. It had seemed so safe, so simple … in hindsight, he’d been a fool. He should have wondered more about the corporation’s willingness to carry out the survey for practically nothing, almost at cost for themselves. It was all too clear they’d had a good idea of what they’d find, when the survey was completed. They had to have known.

He was too tired, after years of legal struggles, to feel anything but numb as he contemplated the past. Montezuma was a treasure trove of raw materials, some so rare that selling them on the open market would bring in enough money to turn the planet into an economic powerhouse. Martin had wondered, despite himself, if it was worth the damage the mining operations would inevitably do to the ecosystem, or the disruption such a vast influx of money would do to the planetary culture. Perhaps there was a way to compromise, to make use of the windfall without destroying themselves … but the corporation hadn’t been willing to negotiate. They’d laid claim to the entire planet, through a spurious legal argument, and appeared to the Supreme Court to back their claim. By the time Martin had realised what was happening, it had been too late. The corporation had shovelled enough money around to ensure the judgement went in its favour.

His legs buckled. He sat on the cold marble floor, his lips twisting at the calculated disrespect. The portraits of Supreme Justices gazed upon him disapprovingly … he fancied they would have been horrified, if they’d encountered such corruption while they’d lived, although he suspected otherwise. He was no expect in Imperial Law – few were, even the ones who devoted their lives to legal practices – but he’d read enough briefs, over the past three years, to know there were enough precedents to justify almost anything, from slavery to stealing an entire planet from its inhabitants, if one had a particularly good lawyer. Martin wasn’t naive enough to think Montezuma’s political system was perfect, but even at its worst it was squeaky clean compared to the empire. The corporation was so wealthy it could buy and sell justices out of pocket change. And none of the men who’d be deciding his planet’s fate – who had already decided – had ever visited his world.

A man appeared and walked towards him, his lips thinning in disapproval as he saw a planetary president sitting on the ground like a wayward child. He wore the formal livery of a court-mandated escort, an unsubtle insult; Martin was all too aware the corprats had argued his people were unfit for independence, that they needed to be taken in hand like unruly children and taught civilisation. His face was bland to the point of being completely unremarkable, without the signs of a life truly lived. Martin couldn’t help thinking, as the young man stopped in front of him, that the poor boy was just a cog caught up in a much greater machine. If he’d wanted to make something of himself, he’d have gone elsewhere.

“The court requires your presence,” the escort said. His accent was pure upper-class, so deeply rooted in the homeworld that it was rarely heard outside Sol. The lack of honorifics was another calculated insult, perhaps a subtle way to tell him his title had been officially revoked. It wouldn’t be legal, as far as Montezuma was concerned, but the planet was no longer in control of its own destiny. “I am to escort you to the judgement chamber.”

Martin put out a hand. “Help an old man up, son?”

The escort looked, just for a second, as if he’d been asked to put his hand into an unflushed toilet. Martin didn’t try to hide his amusement as the escort helped him to his feet, letting go the moment the older man could stand on his own two feet. It wasn’t as if he needed the help, but … he felt a pang of remorse as the escort led him away, swiftly quenched by a growing apprehension. Montezuma had spent vast sums of money preparing a legal case, all of which might have well have been spent on fool’s gold and impossible lawsuits. They’d prolonged the agony, and prevented the court from ruling immediately, but he no longer had any illusions. The justices had known what conclusion the court would reach right from the start.

He followed the escort as the young man led him into the chamber. It was, surprisingly, smaller than the antechamber, but clearly designed to make very clear to the defender that he was in deep trouble. The justices sat in front of him, flanked by the corporation’s lawyers – a tiny percentage of the vast legal army the corprats had at their beck and call – and a handful of reporters, none remotely independent. A pair of men in fancy uniforms flanked the dock – he couldn’t help thinking of the podium as a dock – clearly ready for trouble. Martin wasn’t a military expert, but it was clear the two men were trained and experienced. There would be other security precautions too, kept in the shadows until they were needed. There was no shortage of people who wanted the justices dead.

The Speaker stepped forward, the moment Martin took his place. “We are gathered here today …”

To witness the unholy marriage of raw greed and corruption, Martin thought, as the Speaker droned on, outlining the details of the case and the principle arguments both sides had put forward as the legal battle took shape. The formal conventions had been outdated long ago, and he wasn’t sure why the Court was bothering to uphold them, not when they could justify anything they wanted with a careful read of the countless legal precedents set over the last few centuries. When is he going to get to the point?

It was almost a surprise when it actually came. “On the question of planetary sovereignty, we find that the settlement rights were improperly transferred to the Aztec Revival Movement and as such the entire settlement program was highly illegal, and the planetary population illicit settlers and the descendents of same …”

Martin had known it was coming, but it was still a shock.

“Planetary sovereignty therefore belongs to the Isabella Interstellar Corporation, who laid claim to them legally,” the Speaker continued. Martin wondered, with a sudden burst of fury, just how much he’d been paid – personally – to ensure the vote went the right way. “The planet’s current population, who are there illegally, are ordered to vacate the planet or face indenture for a period of no less than …”

Martin couldn’t help himself. “You’re selling my people into slavery!”

“Silence,” the Speaker snapped.

It was slavery, Martin knew. Indents rarely worked their way out of debt, certainly not if their debtors wanted to keep them. There was no way an entire planet of five million people could be evacuated, even if the planetary assets that might have funded the move hadn’t been seized by the same legal judgement. He’d travelled to Earth a President and now …

“The corporation may take possession of the planet as soon as it wishes,” the Speaker continued. Martin barely heard him. “The illicit settlers are to be given one chance to leave and …”

Martin gritted his teeth, barely noticing the justices filing out the moment the speech came to an end. The kabuki play had one purpose – to put a legal gloss on the corporation’s snatch and grab – and it was over now, all done and dusted. There was no appeal. He wasn’t sure why they’d even bothered. It wasn’t as if anyone on Earth, outside the Grand Senate and the upper classes, cared one jot about the outcome. Montezuma was nothing to the underclass. He doubted one in a billion of Earth’s teeming population could even point to the planet on a starchart. Why would they care?

His escort led him through another set of corridors, the guards following at a safe distance, and into a smaller room. It was an office; a table, three chairs, and even a water jug and glasses, waiting to be used. Two corprats sat behind the table, wearing the expensive suits that were practically a uniform. There was little real difference in appearance between the expensive and slightly less expensive suits, or so he’d been told, but anyone who wore the former had to be taken seriously. The men in front of him clearly did.

“Mr President,” one said. His accent was the same upper-class drawl as his escort, only stronger. “I would like to tell you that I am sorry about the court’s decision …”

“I’m sure you would,” Martin growled. He was sick of Earth, sick of the planet’s corruption, sick and tired of fighting a battle that had been lost before he’d realised it was underway … he just wanted to get home and … and what? Perhaps there had been a point to the judgement after all. If the corprats were the legal owners, they’d be entirely within their rights to call in the military to enforce their claims. “Get to the point.”

The suit looked surprised, just for a second. “It is very unfortunate …”

Martin leaned forward, raising his voice. “Get to the point!”

“We’d like to offer you a job,” the suit said. His tone didn’t change, even though it was clear he’d been planning to butter up Martin before finally making the proposal. “The planet requires a careful hand to integrate it into the corporate system and …”

Martin met his eyes, and had the satisfaction of seeing the man flinch. “You expect me to collaborate with you, to sell out my people?”

“It would make it easier on everyone,” the suit said. He produced a datapad and passed it to Martin. “You would be very well paid, with plenty if vacation time and a guaranteed retirement on a vacation world, with pensions and health benefits for all …”

“And in exchange for this,” Martin said, “you expect me to be the Judas Goat leading my people into slavery?”

“It would make it easier …”

Martin threw the datapad over his shoulder, to distract the guards just for a second, and hurled himself over the table and at the suit. The man was so unused to physical violence he didn’t even try to move, not until it was far too late. Martin crashed into him, knocking him backwards and jamming his fingers into the man’s eyes, trying to kill him before the guards recovered and attacked. The other suit screamed – Martin could smell the piss – an instant before the guard jumped him. Martin lashed out with his foot, hitting someone – he had no idea who – before someone else jammed a shockrod into his back. His entire body convulsed with pain, his muscles twitching helplessly.

“Barbarian,” someone said. “He …”

Martin’s awareness ebbed and flowed as strong hands dragged him up and carried him out the door. He doubted he would ever see his homeworld again, not ever. The corprats would hardly have let him go home if he’d refused their offer, expecting – correctly – that his first move would be to organise resistance. But his planet didn’t need him to resist the invasion. His people would keep fighting, and one day they would be free.

One day …

Prologue II: Montezuma, 98 Years Prior to Earthfall

“No one wants to work anymore,” Director Heimlich Von Raubritter said.

Assistant Director Sharon McManus kept her face under tight control as her boss ranted about how the corporation’s efforts were failing, head office was starting to ask pointed questions and how everyone was plotting against him. Again. Raubritter was unbelievably handsome, thanks to the finest cosmetic surgery money could buy, but there was something oafish about his character that shone through his perfectly-sculpted chin, perfectly clear skin, perfect blond hair, and perfect muscles that wouldn’t have been out of place on a flick action hero. She might have thought him attractive, if she’d seen him at a distance, but five minutes conversation had been enough to convince her Raubritter was just an empty suit. He was nothing more than a well-connected young man who had been parachuted into a post that called for a man with tact, diplomacy, and a certain willingness to compromise with the local population. If he hadn’t had close family ties to the Grand Senate, Sharon was entirely sure he would never have been allowed anywhere near the post.

Her lips quirked as the ranting continued. On paper, the post was an excellent one for a young corprat looking to get his ticket punched before returning to Earth to continue his climb into the corporate stratosphere. Montezuma was a world with incredible potential – vast mineral resources, an ecosystem that was already unpleasant, a population indentured to the corporation – and a smart man could probably use the post to make enough money to satisfy the dreams of his upper-class wife. In practice, the population was revolting – the nasty part of her mind insisted they were revolting in both senses of the word – and keeping them from sabotaging the mining infrastructure was a difficult, almost impossible, job. The corporation had summoned troops to teach the locals a lesson, but there was little they could do to keep the workers from causing trouble. They should have a secure outflow of raw materials by now, yet … they didn’t, and head office was getting antsy. They’d already invested far too much money into the mining operation to back off easily.

Perhaps we should try to come to terms with the locals …

She cut off that line of thought before it could go any further. The corporation had splashed money around like water to make sure the Supreme Court ruled in their favour, and then splashed more money around to ensure the former president was executed rather than being sold into indenture himself. In hindsight, that had been a mistake too; the gruesome details everyone on the planet took for granted might be untrue – the president had not been brutally tortured to death – but there was no denying the man was dead, which had turned him into a martyr. Ironically, the fact he’d died in a bid to save his world had absolved him of the mistake that had led to the corporate takeover in the first place.

“We need to do something,” Raubritter said. He waved a datapad at her, as if she hadn’t written the report herself. There were some details that simply couldn’t be entrusted to a secretary. “How can we raise production?”

Sharon assumed it was a rhetorical question. There were quite a few ways to raise production, starting with treating the locals with a shred of decency, but Raubritter wouldn’t accept any of them. He’d staked his career on exploiting the planet as much as possible, to the point he’d actually signed off on a project to develop the high orbitals, without realising the planet’s cash reserves were falling rapidly. Perversely, Montezuma had never been a very wealthy world. The corporation could fund development, at least until the mining operation started to bring in the cash, but the beancounters would start asking questions. Raubritter would find his career spluttering to a halt if he didn’t find a way to increase production, and fast.

She watched him for a moment, wondering what he’d decide. She’d learnt the art of covering her ass a long time ago, and she would have no trouble demonstrating that Raubritter had made every decision from the moment he took office, if – when – head office started demanding answers. She was tempted to suggest a handful of options that would make even worse trouble for her boss, perhaps taking a loan from another corporation in exchange for future favours, but kept her mouth firmly closed. If she was lucky, she wouldn’t have to put up with him forever. Even if she wasn’t, she’d salted away enough cash to live well for the rest of her life.

“The problem is that the locals cannot be trusted to work for us,” Raubritter said, with the air of a child discovering two plus two made four. “We need more and better workers.”

“Quite,” Sharon agreed. There weren’t many locals willing to cooperate – collaborate – with the corporation. The ones who did were almost worse. Some were outcasts, hated by their peers; others pretended to cooperate long enough to get into position to do some real damage. “Do you intend to educate the locals?”

“No,” Raubritter said, an unusual burst of realism. “The educational program will not produce anything worthwhile for at least a decade, if that.”

Sharon nodded, slowly. She’d grown up in a corporate crèche, and she had little emotional attachments to her parents, but the locals took a different view, She didn’t pretend to understand it, yet she didn’t have to. All that mattered was that trying to raise the planet’s children to be good little corporate drones would make the situation even worse. If nothing else, they simply didn’t have the time.

“We’ll shut down the Delta and Gamma programs, for the moment,” Raubritter said. “Both of them can be placed on hold, without major disruption, and the funds rerouted to an incentive program. We’ll offer high wages and excellent benefits for people with the skills we need, people willing to immigrate and work in our facilities. If we can get enough offworlders, we won’t need the locals at all.”

Sharon blinked. “Do you believe you can recruit enough?”

Raubritter smiled. “If you throw enough money at a problem, it goes away.”

Sharon said nothing for a long cold moment. Raubritter was certainly wealthy enough to take that attitude, and the hell of it was that he had a point. The wealthy corporate families had covered up all kinds of bad behaviour, from the merely obnoxious to the illegal even to scions of the aristocracy, through paying out vast sums to their victims. She considered the figures thoughtfully. They really could offer all kinds of incentives, at least at first. The newcomers might discover the rewards dried up, after a while, but by then it would be someone else’s problem. She had no intention of staying on the desert world any longer than strictly necessary.

“It might work,” she said, finally. It would be very bad for the locals, and perhaps for the descendents of the newcomers, but that would be their problem. She could understand why the locals were so angry, yet she wouldn’t sacrifice her career in a bid to save them. It would be futile to try. “If we can convince enough to join us …”

“Make the preparations,” Raubritter ordered. “I want the project underway by the time head office tries to audit us.”

Sharon nodded. “Yes, sir.”

Chapter One: Mictlan, Montezuma

The air stank. As usual.

Felecia Kahn checked her mask as she scrambled onto the bus, pressed her fingers against the reader to confirm she was an authorised passenger, and found a seat, alone in the midst of a crowd. The other riders were a faceless mass, most wearing masks that covered their entire faces or hoods that made them look utterly inhuman. Even the handful of youngsters who only covered their mouths and noses looked strange, as if they didn’t quite belong. The air was always unpleasant near the mining complex, but today it was particularly bad. The corporation was working desperately to extract every last bit of value it could, before time ran out. She couldn’t help wondering, as the doors slammed closed, if time had already run out. The entire planet was on edge …

The bus rattled into motion, the driver steering his vehicle through the hazy streets towards the checkpoint at the edge of town. Felecia breathed deeply, tasting the scent even through the mask, her eyes scanning the haze for potential threats. The town had been a nice place to grow up, assuming one never went outside the walls, but it had started to decay recently as the pollution got worse. Outdoor gardens and water parks, a sign of proper development on a world known for being dangerously dry, were being steadily ground down; the greenhouses, the only safe way to grow food so close to the complex, were half-buried in the dust. She had been assured the greenhouses were safe, but she feared otherwise. The planet hadn’t been a safe place to live permanently, even before the mining operations had turned vast tracts of land into a polluted nightmare. It was easy, all too easy, to understand why the insurgency had grown and grown until it seemed the entire planet was waging war against the corporations. And the Huéspeds.

She felt her scalp itch and ran her hand through her dark hair. She was going to be dirty and grimy when she got to work, again. She might have time for a shower, if she was lucky, but it was impossible to be sure if they’d get to the complex on time. The road network was very busy at the best of times, even when the insurgents weren’t making life difficult for anyone who wanted to live outside the complex. She’d been so late, only a few short months ago, that she’d reached her workplace thirty minutes before it was time to go home. If her boss hadn’t been surprisingly understanding …

The bus drove through the first set of gates, paused long enough for the second to be opened, and then headed onwards into the desert. The contrast was startling, startling enough to jolt her awake even though she’d seen it a hundred times before. The sand dunes, endlessly shifty and treacherous, stretched as far as the eye could see. A distant shimmer on the horizon promised a sandstorm … she hoped, as she forced herself to sit back on her seat and wait, that it wasn’t heading towards them. Sandstorms meant trouble, particularly here. The insurgents excelled at using them to get close to the settlements and mining complexes, sniping or mortaring or even laying bombs along the roads and withdrawing before they were spotted, leaving deadly surprises for the next set of innocents to drive along the roads. The corporate pullback, abandoning large complexes as the galactic economy collapsed, didn’t seem to be helping. The insurgents, scenting victory, had redoubled their attacks until agreeing – reluctantly – to a truce. Felecia – and the rest of the Huéspeds – doubted it would last for long.

She glanced at her watch as the giant corporate complex – a spaceport, a administrative centre, a warehouse on a planetary scale – came into view. The shacks and shanties around the outer wall chilled her to the bone, as they always did. There were older women trying to sell their wares, eking out a living on a planet that cared nothing for its human occupants, and older men staring menacingly at the bus as it passed; young children ran around, their unprotected faces bearing scars from living too close to the complex, carefully avoiding the open channels that carried effluents and wastes down to the Dead Sea. There were no young women her age, or men either. She knew why.

The bus didn’t slow down as it passed the shantytown and made its way into the guardpost, where it came to a stop as soon as the gates closed behind it. The doors banged open a second later, allowing the passengers to stand and make their way towards the security checkpoints up ahead. The guards looked relaxed, Felecia noted, as they watched the new arrivals pass through the automated sensors. She hoped that wasn’t a bad sign too. She didn’t like being patted down, or being singled out for a random strip search, but it was better than the alternative. The insurgents had smuggled bombs through the gates before and, if the truce failed ahead of time, they’d do it again.

“Clear,” the guard said. He sounded bored as he checked her ID. “You may proceed.”

Felecia thanked him, and headed onwards. The corporation’s giant complex was practically a large town in its own right, the air a little cleaner inside through giant purifiers that swept the pollution out before it could reach offworld noses and lungs. The corporation could have kept its mining operations relatively clean, she knew, but it didn’t care enough to try. She was mildly surprised it had agreed to evacuate the workers, when it had become clear the mining operation would have to be shut down completely. But then, it had a legal obligation to uplift anyone who wanted to go. The corprats might bend the law into a pretzel, or a plate of spaghetti, but they didn’t break it outright. It wasn’t how they rolled.

She breathed a sigh of relief as she removed her mask, then headed towards her workplace. The crowds seemed more relaxed, as if they’d already forgotten the insurgency had been far from defeated. She spotted young children heading to playgroup and older teenagers making their way to the arcade, rather than school. She couldn’t help a twinge of envy. She’d barely had a chance to be a child, growing up in the settlement. She’d had to go to work as soon as possible, just to ensure the family had enough money to live. She was very far from alone.

The office complex was warm and welcoming, the lobby dominated by a statue of Director Sharon McManus, the woman who had directed the Huésped program nearly a century ago and been assassinated for it. Felecia wondered, not for the first time, if the long-dead woman had known what she was doing, or even if she cared. It was unusual to meet a corprat who thought about anything other than the bottom line, who put anything ahead of profits and promotions. Felecia had even heard their marriages and affairs were arranged for them, something that always made her roll her eyes. What sort of marriage had adulterous relationships organised by the wife and mistress? It was just absurd.

She checked her watch again as she reached the office and had a quick shower, then changed into her work clothes and checked her appearance in the mirror before heading back outside to relieve her colleague. Anna Cameron winked at her as she entered, then stood and held out a datapad. Their work was never done.

“He’s got meetings all afternoon, some with people whose real names have clearly been blanked,” Anna told her. “Don’t breathe a word about them.”

“As if I would,” Felecia told her. She was one of the most highly-paid Huéspeds on the planet. She wouldn’t do anything to jeopardise it, certainly not now. “Did you have a good morning?”

Anna laughed. “I was working, so no,” she said. “You want to cover for me tomorrow so I can see Jim?”

Felecia shook her head. If she covered for Anna, she’d either have to stay with her overnight – which would be awkward for both young women and Jim – or find a hotel. The latter would be expensive, even if she chose the one that that expected its guests to sleep in tubes uncomfortably reminiscent of coffins. She didn’t have many other friends in the complex and none of them would put her up, certainly not without a few days warning. Anna didn’t seem particularly put out as she stood, passed Felecia the datachips that opened the complex’s datacore, and headed for the door. Felecia felt a twinge of envy, despite herself. Anna had far more freedom than Felecia, even though they were the same age.

But her family is hundreds of light years away, she reminded herself, as she tapped the console to bring up the director’s schedule. Mine is back in the settlement.

She sighed inwardly, then put the thought aside as she checked the appointment book. Anna had been right. There were seven appointments with clearly fake names, one probably the Caudillo himself and the rest his allies and semi-rivals. Her stomach twisted in disgust. The corporation’s official policy was never to negotiate with insurgents, particularly insurgents who could be easily classed as terrorists, but someone very high up had probably forced a change in policy. The corporation was pulling out, withdrawing from the planet and taking the Huéspeds with it. She supposed she could put up with the decision to discuss a truce with the insurgents, one that would last long enough to let the corporation evacuate the planet in peace. It was better than the alternative. If the war was fought to the last, hundreds of thousands on both sides would die.

The inner door opened, revealing President Dominica Lopez. Felecia stood and hastily genuflected, even through everyone knew the planetary president was little more than the director’s puppet. The older woman barely spared Felecia a glance as she stalked out of the room, not even bothering to be polite as she slammed the door behind her. Felecia resisted the urge to stick out her tongue at the closed door. It was hard not to feel sorry for the so-called president. If there was anyone on the planet who took her title seriously, he was alone.

Her boss stuck his head out of the office. “Have my next guest sent up via the private elevator, and hold all my calls unless they’re from the priority list.”

“Yes, sir,” Felecia said. Director Von Donitz wasn’t a bad boss, all things considered, even though he had a habit of talking to her as thought she were a child. A great many people from Earth seemed to believe their planet was the home of all elegance, and anyone who grew up without attending a finishing school could barely be trusted to tie their shoelaces without getting into a terrible muddle, but she knew it could be worse. One low-ranking corprat had a small harem of pretty secretaries and another was notoriously abusive. “Do you require tea or coffee?”

“I’ll see to it myself,” Von Donitz said. “If anyone who isn’t on the priority list calls, take their names and I’ll call them back.”

Felecia frowned as her boss withdraw, closing the door behind him. It was her job to bring him and his visitors tea and coffee – and everything else, from little biscuits to full meals – and effectively wait on them … and yet, he was going to make his own coffee? It was out of character for the most powerful man on the planet, a man who couldn’t operate a drinks dispenser to save his life. Sure, anyone could put coffee grains and milk and hot water together, but …

He doesn’t want me to see who’s visiting, she thought. It was wrong, and having the thought made her feel uneasy, and yet it refused to go away. Didn’t he trust her? Who is he meeting … and why?

The unease nagged at her mind as she sat back down. She had never been quite sure why Von Donitz had hired her in the first place. She knew she was capable and competent and cheap, by corprat standards, but … he could get a second offworld assistant if he wished. Anna wasn’t paid anything more than Felecia, as far as she knew, and the director could pay a hundred offworlders like her out of pocket change. She had wondered, at first, if he’d had other reasons, but he’d never made a pass at her. Hell, he’d never even hired a high-class escort. She’d seen his personal accounts. If the man had any interests beyond doing his job, he kept them well hidden.

Her terminal bleeped. The guest had arrived. His escort had brought him through the secure corridors and they were now waiting for the elevator, the one that would take them into the office without walking past her guest. She tapped her console, informing Von Donitz that the mystery guest had arrived, then leaned back in her chair. Who was it? And what were they discussing? Her eyes lingered on the door for a long moment, then returned to her console. She could press her ears against the metal, if she wished, but she’d hear nothing. The room was completely soundproofed.

The unease grew as she surveyed his inbox. It was astonishing how much crap was forwarded to the director, and how much the director relied on his staff to separate the genuinely important messages from the spam. There were just too many people who had permission to send emails directly into the poor man’s box, not all of whom could be trusted not to take advantage of it. She put a number of emails into the low-priority box – they weren’t aimed at the director, merely copied to him – and rolled her eyes at the sheer pettiness displayed by officials who had to know their time on the planet was coming to an end. The infighting had never stopped, even as mortar shells rained on settlements and antiaircraft missiles were fired at shuttlecraft or helicopters. Perhaps it had just been a way of coping with the constant threat of death, she thought wryly. The officials couldn’t do anything about the insurgency, but they could fight bitter office wars over pointless issues …

Her lips twisted as she scanned an update from Sol, confirming – as if everyone hadn’t already known – that Earth was effectively gone. It was hard to wrap her head around the sheer scale of the disaster. There had been eighty billion people on the planet, including the Grand Senate and much of the Civil Service, and they were just gone. The orbital halo, the cluster of settled asteroids and industrial nodes that had turned the system into an economic powerhouse, lay in ruins. The destruction of entire colonies on Mars, or asteroid settlements being shattered, would have dominated news cycles a few years ago, but now they were barely drops in an ocean of blood. Felecia had been born on Montezuma, and she had never been offworld, and yet … losing Earth felt like the end of the universe. The old certainties were falling everywhere. No wonder, she reflected, that the corporation was preparing to abandon the mining world. Right now, they’d be lucky if they could still in business long enough for the dust to settle and a new order to arise.

She frowned as she read a message from General Hampshire. The man had never liked her, or Huéspeds in general, but he had done a fairly good job of coordinating the defences well enough to keep the mines open. Her brother had had some choice things to say about the general, yet … she shook her head, eyes narrowing as she scanned the words. There was something oddly weaselly about it, a strange tone from a man who was often blunt to the point of rudeness. It was even stranger, she noted, that he’d done a spot of clerical work himself. Generals didn’t plan operations, certainly not in anything more than broad strokes. That was what his staff were for …

The plan was simple, the uplift schedule for departure … a month, more or less, from the present date. Felecia felt an odd little moment of regret, then frowned as something struck her. The evacuation plan was surprisingly vague in places, but it was clear that it was only intended to last a few days. Her frown deepened, her heart thudding as she kept reading. She was no military expert, and she’d never flown in a shuttle in her entire life, but even she knew there were hard limits on how many passengers could be transported to orbit in a single flight. Assuming a flight schedule that was probably unrealistic, without a single delay or technical failure, they couldn’t hope to get more than a few tens of thousands of people off world in the period. Unless they were bringing in extra shuttles or transports … she’d been told colonist-carriers were being arranged, but that had been a month ago. No one knew if the schedule was still in operation, or it had been changed somewhere dozens of light years away. The planet had never been so isolated before.

Odd, she thought. The truce was intended to give the corporation time to evacuate peacefully, leaving the world to the original population. How do they intend to get us all off?

It hit her in a flash, horror numbing her so completely she could barely move. She didn’t want to consider the possibility, even hypothetically, but the figures didn’t lie. The truth was right in front of her, barely concealed. There was no way to turn away and pretend she hadn’t seen it …

They don’t intend to evacuate us at all, she thought, stunned. They’re leaving us behind.

October 23, 2023

Snippet – Boys Own Starship

Hi, everyone

This is a novella (planned 30K) aimed at young teenagers (think Starman Jones or The Rolling Stones). It’s also something of an experiment, so comments (etc, etc) are warmly welcomed.

Chris

Chapter One

“I’m telling you,” Eric said, “we can do this!”

“And I’m telling you we don’t have the money,” John said. His brother had always been the careful one of the duo. He’d gone into engineering, while Eric had studied interstellar piloting and navigating. “Even if we combine both of our trust fund payments for the next decade, we won’t have enough money to purchase an interstellar freighter.”

Eric smirked. “I’ve got a plan,” he said. “We purchase two scrap freighters.”

John gave him a sharp look. “Scrap freighters?”

“Yes,” Eric said. He held out a datapad. “There are two Century Hawk-class light freighters at the scrapyard, on sale for a song. Neither one can fly on her own, but we can cannibalise the first ship to make the second fly and add a few other components to improve her. A stardrive, for example …”

“I see.” John scanned the datapad thoughtfully. “They do seem to match up. We could use one to make the other fly. But why didn’t the scrapyard operator do it himself?”

Eric shrugged. “The design is very old,” he said. “Anyone who has the money would prefer a modern ship, complete with modern systems. These ships are over fifty years old.”

John nodded, thoughtfully. “And they’d need a proper stardrive to be competitive,” he said. “If we could install one.”

“We could do it,” Eric said. “This is our chance!”

They exchanged long looks. They’d been trust-fund children for a long time, ever since their parents had vanished in interstellar space and left them – and their older sister – alone. They were hardly poor or starving, but they couldn’t take control of the family corporation until all three had turned twenty-five and that was over thirteen years in the future. They’d spent the last five years living in the mansion, studying desperately, and hoping – against all odds – that their parents would miraculously return. But they’d grown tired of waiting, and they didn’t want to grow up like so many others they’d met over the last few years. They wanted to emulate their parents and do something with their lives.

“Maryam will have to sign off on the expense,” John pointed out, finally. “How do you intend to convince her?”

“She signed a permission slip,” Eric reminded him. “Is it my fault she doesn’t have time to authorise every expense separately?”

John stood. “Let’s go then, shall we?”

Eric nodded and led the way to the aircar pad on the roof of the mansion. They both had flying permits, but they weren’t allowed to fly personally without a qualified adult beside them … one of the many rules and regulations on Old Earth their parents had chafed against, when they’d been young and intent on building up an interstellar shipping corporation of their own. Eric wondered, sometimes, quite why their parents had never moved to the colonies, where men could breathe free and laws were dictated by common sense rather than bureaucratic inertia. Earth had better schools and industries, but anyone could take the schooling modules and learn at home rather than attending class with hundreds of other students. Eric had gone to school with the super-rich – or, more accurately, the children of the super-rich – for a year and he had no intention of going back. He’d never met quite so many spoilt brats in his entire life. Even the ones who were eighteen were going on eight.

The aircar hummed into the air and flew north, the autopilot taking them away from the mansion and straight towards the giant scrapyard hundreds of miles away. It was meant to be a repair and renovation centre, he’d been told, but most starships landed in the scrapyard were left to die. He’d checked, out of curiosity, and discovered that anything capable of being useful – still – was never scrapped, merely passed down to a new set of owners. He frowned inwardly, wondering – despite himself – if there was something wrong with the scrapped freighters. They might have fallen through the cracks – too small to be useful – but it was still odd. The asteroid miners tended to be unconcerned about the exact state of the starship as long as it could hold an atmosphere and power a drive.

John leaned forward as the scrapyard came into view, miles upon miles of grounded starships from the last hundred years of interstellar exploration and settlement. There were ships so old they predated faster-than-light travel and ships so new they were younger than John, although they were visibly banged up so badly it was clear they would never fly again. The distant refineries were working hard, breaking down the scrapped ships and recycling as much as possible for transfer to the orbital industrial nodes. What little was left would, eventually, be thrown into the sun. He sucked in his breath as the aircar landed neatly, the two boys scrambling out to be met by the manager. The man looked unsure of himself …

Eric smiled. So much the better.

“We spoke earlier,” he said, before the man could say a word. Adults tended to get rather pedantic, when dealing with children … never mind that Eric was a teenager and John on the cusp of joining him. “Please show us to the Century Hawks.”

The manager nodded and led them through the gate and into the yard itself, passing dozens of scrapped vessels. There was little security, nothing to keep the locals from sneaking in and night and taking whatever they wanted. Eric suspected the scrapyard’s owners simply didn’t care. If the locals could make use of something from the yard, they might as well have it. Anything truly valuable would have been removed long ago. They walked past a giant freighter that had been modified so many times, before being finally scrapped, that it was impossible to tell which class she’d originally been, then paused as the Century Hawks came into view. They were ugly as sin …

… And yet, they were also the most beautiful ships in the known universe.

He stared. The ships looked like crude arrowheads, antigravity nodes clearly visible on their hulls and a mighty sublight thruster to their rear. Their hulls looked scarred and pitted, but his visual inspection suggested there were no cracks or obvious weak points in the hull. He’d looked it up, when he’d realised the opportunity in front of him, and noted that the design was surprisingly tough. There were records of a Century Hawk coming down hard, practically crash-landing, and being put back into service within a week. Eric was fairly sure the crew had gotten very lucky – his instructors had drilled him mercilessly, before giving him his licence, and pointed out that a single mistake could easily get the entire crew killed – but they had survived. Any landing was a good one, as long as you could walk away from it.

“Your ships,” the manager said. “Let us know if you want to purchase them.”

He turned and walked away. Eric grinned to himself as he led the way towards the hatch. He’d been to a dozen used starship dealers, over the last couple of years, and all of them had tried to talk up the ship as much as possible, glossing over precise details that might have cost them the sale. Eric had tried to purchase a crippled starship once and had only been stopped, thankfully, by the rules governing his trust fund. It had been irritating, but he had learnt a useful lesson. Perversely, the manager’s lack of concern was surprisingly reassuring. The man had nothing to gain – or lose – if they purchased the ships or not.

“The interior is a little rank,” John commented. He dug his engineering toolkit out of his belt and deployed the scanning microbugs. The tiny machines would survey the ship from bow to stern, then relay their findings to John’s wristcom. “Other than that …”

Eric barely heard him as they made their way through the ship. The internal lighting was online, revealing small cargo holds and cabins and a bridge that was barely large enough to be called a bridge. He was mildly disappointed to note there was no command chair, merely three control stations … but then, the freighter was hardly a giant interstellar warship. The systems were powered down, the consoles dark and silent … he reached for a switch, thoughtfully, then stopped himself. They might have been told the ship was effectively powerless, save for the lighting, but his instructors had cautioned him to take nothing for granted. It was unlikely the scrapyard’s engineers had been particularly careful when the ships had been moved to their final resting place.

John knelt on the deck and studied the live feed from his microbugs. Eric left him to it and walked through the remainder of the ship, feeling as if he were standing in the midst of a ghost vessel … although one with massive potential. The cabins had been stripped bare – he opened a pair of drawers, just to be sure, and found nothing – and the holds were completely empty. He hadn’t expected to find anything, not after the ship had been searched multiple times, but it was still a little disappointing. There were all sorts of stories about people discovering hidden treasures in their new homes, or starships; indeed, some of the stories were actually real.

“I’ll have to inspect the other ship, then draw up a work plan,” John said, as Eric returned to the bridge. “It should be doable.”

Eric grinned. “I told you so.”

“We haven’t made it happen yet,” John cautioned him. “And we’ll need to find a stardrive.”

“There’s bound to be one around here somewhere,” Eric said. A new-model stardrive would be expensive, but an older design would come cheaply … if they could find one. “Or we can find one in another yard.”

“If,” John said. He glanced at the holograms projected by his wristcom. “The internal datanet needs replaced, or modernised. The life support system is in good condition, but I’d be happier with a couple of back-ups. The navicomputer really does need replaced, if we want to take the ship out of the system. It was never designed to work with a stardrive.”

He paused. “We’ll have to buy that one new.”

“Joy,” Eric muttered. They might be wealthy, even by Earthly standards, but there were limits. “What else?”

“They tore out the onboard fabbers and food recyclers,” John said. “We’ll need to replace those too.”

“We could just stockpile regular food,” Eric reminded him. “And …

His brother interrupted him. “And what happens if we get stranded in interstellar space?”

Eric nodded, curtly. “Add it to the list.”

John stuck out his tongue. “Add it to the list? I thought you were keeping the list.”

“I am,” Eric said. “But you need to keep a list too.”

He sighed, inwardly, as they headed to the second starship. The interior looked a great deal more cracked and broken, to the point he honestly wondered if the starship had been boarded by pirates, but enough systems remained intact to allow the ship to be cannibalised. He followed his brother through the hull, trying to breathe through his mouth, as they checked each and every component before retreating back to the fresh air. Something was clearly rotting away, inside the second starship. Rats, perhaps. They had a nasty habit of sneaking onto starships and riding into interstellar space. The hull should have been fumigated, he reflected as they made their way back to the office, but if the vessel was being scrapped it was possible no one had bothered.

The manager nodded politely. “Did you find what you were looking for?”

“We’d like to buy both hulls,” Eric said, flatly. “And hire a crew to transfer them to the local spaceport, once we have made arrangements for the refit.”

“Of course,” the manager said. If he had any doubts about selling two hulls to a pair of teenagers, he kept them to himself. He’d have checked Eric’s piloting licence and John’s engineering licence when they made contact the first time. “I’ll see to it personally.”

Eric nodded as he withdraw a credit chip from his pocket and placed it against the reader, bracing himself. The expense should have been pre-authorised, if he’d done everything properly, but it was just possible the bank might balk. The trust fund wasn’t unlimited … he gritted his teeth in annoyance, remembering the spoilt brats who had unlimited access to the family’s bank account despite being underage. If he had that sort of money, he could buy a modern freighter and outfit it out of pocket change. He breathed a sigh of relief when the money was transferred, without a hitch.

“We’ll be in touch,” he said. “Thank you.”

His wristcom vibrated the moment he stepped outside. He glanced at the message and swallowed. GET BACK HERE NOW!!!

“Three exclamation marks,” John said. “Who was it who said that three exclamation marks was the sign of a deranged mind?”

“I can’t recall,” Eric said, as they hurried to the aircar. Maryam normally minded her own business, and kept her head firmly buried in her studies. If she was calling them home so urgently … he felt his heart sink. Maryam was their legal guardian, to all intents and purposes, and if she wanted to say they couldn’t go … he closed his eyes as the aircar took off, mentally rehearsing his arguments as they flew back home. “We have to convince her.”

John giggled. “You could always tell her we’ll be out of her hair for good,” he said. “She hasn’t forgiven us for chasing Hank away, remember?”

The aircar landed nearly on the rooftop landing pad, and the two boys made their way down to their sister’s office. She was sitting behind her desk, reviewing expense records … Eric wondered, suddenly, if she’d left a flag in the family banking accounts, a computer program designed to alert her if a large sum was withdrawn in a single transaction. It wasn’t impossible. She might not have absolute power over the family business, not yet, but she did have a great deal of influence.

He composed himself as his sister scowled at him. “You called?”

Maryam didn’t smile. “And what, exactly, are you thinking? Spending most of your trust fund on a pair of clapped-out starships?”

“Which can be combined into a single working starship, with a little sweat and blood,” Eric said, easily. It was hard to keep his voice steady. He wanted to yell at her, to demand to know why she thought it was any of her business. “We can install a stardrive and take her out on an interstellar cruise …”

“And then what?” Maryam met his eyes. “How do you intend to make enough money to keep the ship running?”

“Most interstellar freighters are huge, and their prices are correspondingly huge,” Eric pointed out. He’d spent years digging into the economics of interstellar travel. “It can be very expensive to ship goods from star to star, even if you only hire a tiny hold on a giant starship. Our ship is smaller, with smaller running costs, and we won’t need to charge through the nose to keep the ship running.”

“And we also have the remainder of our trust fund for the year,” John put in.

“And we can ship goods quite some distance,” Eric added. “Foodstuffs, colony gear, modern computer systems … all worth very little here, but worth their weight in gold on the other side of explored space.”

Their sister looked unconvinced. “And how exactly did you get me to agree to pay for all this?”

Eric kept himself from smiling. Somehow. “You pre-authorised trust fund expenditures,” he said. “There was no need to consult with you, as long as we didn’t overdraw the account.”

Maryam gave him an icy look. “You are aware, of course, that your licences are dependent on you having a qualified adult accompanying you,” she said. “How do you intend to address that problem?”

“No one is going to inspect a single light freighter,” Eric said. “And once we’re away from Sol, no one is going to care …”

“I wouldn’t put money on that,” Maryam said, coldly. “And if you do get inspected, what then?”

Eric hesitated, unsure what to say. If they did get inspected …

“You come with us,” John said. “You are an adult, are you not?”

“That doesn’t mean I want to come with you,” Maryam pointed out. “Who else can you ask?”

Eric thought fast. There wasn’t anyone else. The handful of household servants hadn’t signed up for interstellar voyagers, and he didn’t want to ask them in any case. They didn’t have any close adult relatives, or they’d have been living with them, and asking a stranger was asking for trouble. Maryam was the best choice, if they had to have an adult, and yet … she was their older sister. And she could be a real stick-in-the-mud at times.

“You’re studying to become a doctor, right?” Eric spoke fast, before either of the other two could come up with a response. They weren’t the only ones who wanted to be more than just trust fund babies, waiting for full control of the family fortune. Maryam had decided she was going to be a doctor long ago, perhaps even before their parents had vanished. “You need interstellar experience, if you want to get ahead in the field. Right?”

Maryam nodded, shortly.

“So come with us,” Eric said. “I do the flying, John does the engineering, you do the medical stuff. You’ll be listed as ship’s doctor. You can carry on with your studies while we do our thing, and when we get home you can say you’ve been an interstellar doctor.”

“It might work,” Maryam said, slowly.

“And you wouldn’t have to deal with all those boys who come crawling round,” John put in. “Wouldn’t that be great?”

Maryam had to laugh. “Let me check the paperwork first,” she said, firmly. “And read through the requirements for interstellar medical experience. And if that works …”

Eric grinned. They were going to space!

Chapter Two

“Everything appears to be in order,” the inspector said. “When do you intend to fly?”

“As soon as the cargo is loaded,” Eric said. The inspector had gone over the ship with a fine-toothed comb, checking and rechecking everything so carefully Eric had feared he was looking for a reason to decline their licence. It had taken three weeks to strip down one of the ships, transfer everything to the other ship, then purchase and install everything they couldn’t cannibalise or find in the scrapyard. “We should be ready to leave in a couple of days.”

The inspector nodded, slowly. “I ran through all the basic tests,” he informed them. “I advise you to carry out your first jump within the system, just in case you have a drive failure, but otherwise you are good to go. Make sure you have all your certifications filed, before you depart.”

He pressed his thumb against a datapad, transferring the licence file to the starship’s datacore, then turned and made his way back to the airlock. Eric let out a breath he hadn’t realised he’d been holding. The refit had been more complex than he’d anticipated, and a number of components that had seemed to be in working order had needed to be replaced, and it had been quite possible that the inspection would turn up errors the shipyard staff had missed or simply decided could be safely overlooked. The man had certainly asked a great many questions, most of which hadn’t had anything to do with him. It had been incredibly frustrating, not least because they hadn’t been sure what he was trying to do.

“I’ve filed the licence,” John said. “And the updated flight roster.”

Eric smiled, although he couldn’t help feeling a pit in his stomach. The ship – they’d promised themselves they wouldn’t name her until after she was ready to fly – didn’t need a big crew, but they were pushing their luck by only having three people onboard. It didn’t help that Maryam had almost no spacer training at all, beyond the basics, and wouldn’t be able to do much if they ran into trouble. Eric and John had crawled over the ship, going through every emergency procedure in the manual, but they’d been cautioned that the manual was no substitute for real experience. Emergency drills tended to leave out the actual emergency. A disaster plan might work perfectly, on paper, but fail drastically in the real world.

“We’d better get the cargo loaded onboard,” he said. “And then we can get going.”

He sucked in his breath as he made his way through the ship. Maryam had claimed the largest compartment for herself, and refitted a second to serve as a makeshift sickbay, complete with autodoc and stasis chamber. She’d teased them both with suggestions she might invite one of her suitors along to see if he could tolerate her bothers in close quarters for weeks, but – thankfully – she’d refrained from actually doing it. Eric and John had claimed the next set of cabins, both so small there was barely any room to swing a cat, and turned the remaining cabins into passenger spaces. He didn’t intend to take passengers, at least on the first cruise, but having the space might be helpful. There were plenty of people who wanted to travel and didn’t have the time, or the money, to buy space on a big colonist-carrier …

Maryam stuck her head out of her sickbay. “Did you pick a good cargo?”

Eric nodded, curtly. It wasn’t easy to get advanced computer systems on colonial worlds. The big interstellar shipping and colonisation firms preferred to transport colonists, farming gear and equipment that was easy to repair, if it broke down. They’d purchased a hundred modern datacores, their operating systems sold separately, that could – at least in theory – be sold for a reasonable mark-up. If they were wrong … he reminded himself, sharply, that they had enough food and fuel to keep going for quite some time, even if it was better not to think about quite where their ration bars were coming from. At worst, they could go back to Earth …

He shook his head. Their parents had started from nothing – well, practically nothing – and built an interstellar shipping empire. They had never given up, despite setbacks that would have destroyed lesser men, and they’d been rewarded for it. Eric had no intention of giving up either. He was going to prove himself worthy of the family inheritance or die trying. John – and Maryam too, he suspected – felt the same way.

“Good luck,” Maryam said. “You got all your educational modules too?”

“Yes,” Eric said, as if she hadn’t watched closely while they’d purchased and downloaded enough modules to keep them busy for the next decade. They were lucky they’d done most of their studies at home, although they’d still had to attend online examinations to actually get their qualifications. They’d need to do that again, after they finished their next set of modules … if they had time. “Our education won’t suffer.”

“Hah.” Maryam looked unconvinced. “If this demented scheme doesn’t work …”

“It must,” Eric said. “Or do you want us to grow up into spoilt little brats.”

Maryam made a rude gesture, then returned to her work. Eric smiled and hurried on to the airlock. The trade goods were already waiting in the nearby warehouse, ready to be transferred to the ship. He keyed the hatch, gave the orders, then returned to the bridge. John was still there, making sure all the computer nodes were working in harmony. He looked up as Eric entered.

“We should be clear to fly at any moment,” he said. “You want to book a slot? Or should we hold a party?”

Eric shook his head. One downside of living in the mansion and studying at home, after their parents died, was that they had few friends worthy of the name. Too many of their acquaintances were more interested in making friends with the family fortune, rather than the family itself, and he had little interest in inviting them to a party. The remainder … none of their acquaintances really had much in common with them. Most were from very old money indeed and could trace their ancestors back to the primordial ooze, or very new and insecure in their wealth. Eric and John had never quite fitted in. Their family was wealthy, but most of that wealth was locked away until John turned twenty-five.

“Which leads to the all-important question,” John said. “What do we name our ship?”

“Can’t stick with Century Hawk,” Eric said. The class might have been out of production for years, but there were still hundreds of working models plying the spacelanes. “Max Jones?”

They shared a look. They’d both enjoyed the novel – and the updated reissues, and the three different movie versions – and, truth be told, they’d found it inspiring. Max Jones had wanted to make something of himself, and he’d succeeded. If they went with Max Jones …

“Good idea,” John said. “Max Jones she is.”

Eric smiled, silently relieved. They had purchased the ship together and spilt the ownership rights fifty-fifty, something that would cause problems if they disagreed. Maryam had flatly refused to purchase a five percent share from each of them, ensuring she’d cast the deciding vote if Eric and John couldn’t agree on something … Eric hoped, as he keyed the terminal to register the name, that it didn’t come back to bite them one day. They were close, true, but they didn’t always agree on everything.

“I’ll finish up here,” John said. “Book a departure slot for tonight?”

“Check with Maryam, then do it,” Eric said. He’d told the inspector they should be ready to leave in a couple of days, but once the cargo was loaded they could go at any moment. “If she’s happy to leave now …”

He smiled, then made his way down to the holds. The hatches were open, the loading crews carefully transferring the sealed pallets to the hold and making certain they were secured against sudden violent motions. The compensators were top-of-the-range – only a fool would risk compensator failure when the ship was in flight – but it was better to be careful. Eric walked through the gaps, checking to make sure the seals were still in place. There was no shortage of horror stories about crewmen skimping on the survey and discovering, too late, that the crates had been opened, the goods stolen or replaced by stowaways or hijackers. He’d checked the crates before, but it was well to be careful. Anything could have happened in the warehouses.

“All good,” he said, to the foreman. He slipped the man a hefty tip. Cash was preferable to electronic money, not least because the managers insisted on getting a share of the latter. “See you next time.”