Michael Swanwick's Blog, page 192

June 7, 2012

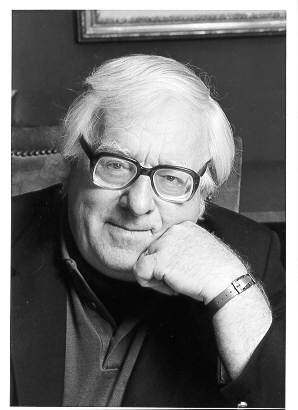

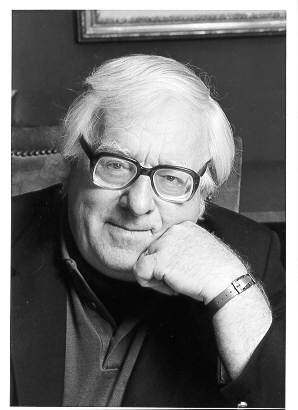

Raise a Glass of Dandelion Wine . . .

.

I was quoted in today's front-page Philadelphia Inquirer article marking the death of Ray Bradbury, and thankfully though my comments did not rise to the soaring heights that the best tributes reached, neither did I say anything stupid. Nor did anyone else, though the bracketed insertion into one of the observations that Darrell Schweitzer made ("showing by example that it was not merely OK but a superior means of storytelling for the [science-fantasy] writer to get in touch with genuine feelings") showed that the newspaper writer entirely missed what Darrell was saying.

No, not just for the science-fantasy writer. For any writer.

Bradbury was unique in that his fame transcended genre while he remained adamantly within that genre. Asimov, Heinlein, and Clarke became world-famous -- but as genre writers. Vonnegut became world-famous -- but only by denying that he was a science fiction writer. Bradbury was acknowledged to be a major American writer -- no genre qualifiers -- while never denying that what he wrote was (for the most part; and definitely for the better parts) science fantasy and horror.

Good on you, Ray. Wherever the barque of your fate takes you now, may the wind be at your back and water foaming white to either side.

You can read the Inquirer article here.

And other tributes to Bradbury pretty much everywhere.

*

I was quoted in today's front-page Philadelphia Inquirer article marking the death of Ray Bradbury, and thankfully though my comments did not rise to the soaring heights that the best tributes reached, neither did I say anything stupid. Nor did anyone else, though the bracketed insertion into one of the observations that Darrell Schweitzer made ("showing by example that it was not merely OK but a superior means of storytelling for the [science-fantasy] writer to get in touch with genuine feelings") showed that the newspaper writer entirely missed what Darrell was saying.

No, not just for the science-fantasy writer. For any writer.

Bradbury was unique in that his fame transcended genre while he remained adamantly within that genre. Asimov, Heinlein, and Clarke became world-famous -- but as genre writers. Vonnegut became world-famous -- but only by denying that he was a science fiction writer. Bradbury was acknowledged to be a major American writer -- no genre qualifiers -- while never denying that what he wrote was (for the most part; and definitely for the better parts) science fantasy and horror.

Good on you, Ray. Wherever the barque of your fate takes you now, may the wind be at your back and water foaming white to either side.

You can read the Inquirer article here.

And other tributes to Bradbury pretty much everywhere.

*

Published on June 07, 2012 13:36

June 6, 2012

From Science Fiction & Fantasy to Fiction & Literature

.

I was in a bookstore today and after checking out the SF&F section to see if there was anything new I needed, cruised the Fiction & Literature section. Kurt Vonegut's Cat's Cradle caught my eye because it's a science fiction novel that's routinely shelved as literature. So I did a quick scan of the shelves to see what other undeniably genre books were there. Not a careful one, mind. I'm sure I missed a lot. Here's what I did note, however:

Frankenstein by Mary Shelly

Dracula by Bram Stoker

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson

Orlando by Virginia Woolf

Anthem by Ayn Rand

A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess

Cosmicomics by Italo Calvino

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court by Mark Twain

The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka

Against the Day by Thomas Pynchon

Haroun and the Sea of Stories by Salman Rushdie

The Collected Stories of Edgar Allan Poe

and three shelves of Stephen King's works.

To say nothing of books you might well quibble about on various grounds, such as Gulliver's Travels, The Inferno, Alice In Wonderland, and Chuck Palahniuk's Fight Club.

The thing is that while all these books are undeniably genre, it does not surprise anybody to see them shelved in Fiction & Literature. Because they're all three: Fiction, Literature, and either Science Fiction or Fantasy, depending.

Which led me to muse upon Vonnegut's famous apostasy, when he denied writing science fiction in order to be accepted by what we rather quaintly like to refer to as "the mainstream." He left a lot of hurt feelings in his wake. But his work was always headed for a place on the Literature & Fiction shelves, the same way that Philip K. Dick's and H.P. Lovecraft's works are headed there today. I think he just wanted to see it happen while he was still alive.

Above: Half a face from a children's ride in the Ekaterinburg city zoo. Not terribly relevant to the conversation, admittedly. But I'm feeling whimsical today.

*

I was in a bookstore today and after checking out the SF&F section to see if there was anything new I needed, cruised the Fiction & Literature section. Kurt Vonegut's Cat's Cradle caught my eye because it's a science fiction novel that's routinely shelved as literature. So I did a quick scan of the shelves to see what other undeniably genre books were there. Not a careful one, mind. I'm sure I missed a lot. Here's what I did note, however:

Frankenstein by Mary Shelly

Dracula by Bram Stoker

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson

Orlando by Virginia Woolf

Anthem by Ayn Rand

A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess

Cosmicomics by Italo Calvino

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court by Mark Twain

The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka

Against the Day by Thomas Pynchon

Haroun and the Sea of Stories by Salman Rushdie

The Collected Stories of Edgar Allan Poe

and three shelves of Stephen King's works.

To say nothing of books you might well quibble about on various grounds, such as Gulliver's Travels, The Inferno, Alice In Wonderland, and Chuck Palahniuk's Fight Club.

The thing is that while all these books are undeniably genre, it does not surprise anybody to see them shelved in Fiction & Literature. Because they're all three: Fiction, Literature, and either Science Fiction or Fantasy, depending.

Which led me to muse upon Vonnegut's famous apostasy, when he denied writing science fiction in order to be accepted by what we rather quaintly like to refer to as "the mainstream." He left a lot of hurt feelings in his wake. But his work was always headed for a place on the Literature & Fiction shelves, the same way that Philip K. Dick's and H.P. Lovecraft's works are headed there today. I think he just wanted to see it happen while he was still alive.

Above: Half a face from a children's ride in the Ekaterinburg city zoo. Not terribly relevant to the conversation, admittedly. But I'm feeling whimsical today.

*

Published on June 06, 2012 12:02

June 5, 2012

Engels Park

.

During the Cold War, here in America, everything the Soviets did was inferior and wrong. When they managed to do something that was undeniably better than what we had -- the Moscow Metro stations, for example -- they did it for the wrong reasons. As propaganda, usually.

I am not about to deny the horrors of the Soviet Union. The millions of deaths from forced collectivism, government-caused famine, and the Terror were very real. Still . . . everything? Without exception?

One morning in Ekaterinburg, I went for a walk and come upon Engels Park. It was sad and wonderful, the ruins of a place that had been lovingly created to give children a playground worthy of their imaginations.

One morning in Ekaterinburg, I went for a walk and come upon Engels Park. It was sad and wonderful, the ruins of a place that had been lovingly created to give children a playground worthy of their imaginations.

The centerpiece of this was a locomotive. A real one, not mock, which had been made safe for children and then painted bright colors. There was also a brick spiral with window-crenelations which could be used as a fort or a house, a ramp which I'm guessing was for winter sledding, some standard playground equipment, a railroad car separate from the locomotive, a cluster of brick castle-towers that looked like chess pieces, and much else as well.

In the wake of Perestroika, everything fell apart, including Engels Park, most of which was defaced by vandalism and graffiti. During Soviet Times, everybody celebrated Lenin's birthday by "voluntarily" beautifying public spaces. "It was exactly like a day of work," one woman old me, "only without pay." Now that Russia is capitalist, volunteerism seems to be as much a discredited relic of the past as Communism itself. Nobody plays Ivanhoe in the towers because they're filled with rubble and liquor bottles. Half the playground equipment is broken.

In the wake of Perestroika, everything fell apart, including Engels Park, most of which was defaced by vandalism and graffiti. During Soviet Times, everybody celebrated Lenin's birthday by "voluntarily" beautifying public spaces. "It was exactly like a day of work," one woman old me, "only without pay." Now that Russia is capitalist, volunteerism seems to be as much a discredited relic of the past as Communism itself. Nobody plays Ivanhoe in the towers because they're filled with rubble and liquor bottles. Half the playground equipment is broken.

But I believe that someday Engels Park will make a comeback. In my own Philadelphia neighborhood, Gorgas Park was sad and rundown when I moved here, thirty-some years ago and today it's something to be proud of. Engels Park is a small gem -- it just needs some polishing. Which, as Ekaterinburg continues to grow more prosperous, it will eventually get. After all, somebody is keeping that locomotive painted.

And even in Cold War times it was generally acknowledged -- grudgingly, perhaps -- that the Russians were pretty good to their children.

Above: I could have taken a lot more pictures of broken things, but my heart wasn't in it.

*

During the Cold War, here in America, everything the Soviets did was inferior and wrong. When they managed to do something that was undeniably better than what we had -- the Moscow Metro stations, for example -- they did it for the wrong reasons. As propaganda, usually.

I am not about to deny the horrors of the Soviet Union. The millions of deaths from forced collectivism, government-caused famine, and the Terror were very real. Still . . . everything? Without exception?

One morning in Ekaterinburg, I went for a walk and come upon Engels Park. It was sad and wonderful, the ruins of a place that had been lovingly created to give children a playground worthy of their imaginations.

One morning in Ekaterinburg, I went for a walk and come upon Engels Park. It was sad and wonderful, the ruins of a place that had been lovingly created to give children a playground worthy of their imaginations. The centerpiece of this was a locomotive. A real one, not mock, which had been made safe for children and then painted bright colors. There was also a brick spiral with window-crenelations which could be used as a fort or a house, a ramp which I'm guessing was for winter sledding, some standard playground equipment, a railroad car separate from the locomotive, a cluster of brick castle-towers that looked like chess pieces, and much else as well.

In the wake of Perestroika, everything fell apart, including Engels Park, most of which was defaced by vandalism and graffiti. During Soviet Times, everybody celebrated Lenin's birthday by "voluntarily" beautifying public spaces. "It was exactly like a day of work," one woman old me, "only without pay." Now that Russia is capitalist, volunteerism seems to be as much a discredited relic of the past as Communism itself. Nobody plays Ivanhoe in the towers because they're filled with rubble and liquor bottles. Half the playground equipment is broken.

In the wake of Perestroika, everything fell apart, including Engels Park, most of which was defaced by vandalism and graffiti. During Soviet Times, everybody celebrated Lenin's birthday by "voluntarily" beautifying public spaces. "It was exactly like a day of work," one woman old me, "only without pay." Now that Russia is capitalist, volunteerism seems to be as much a discredited relic of the past as Communism itself. Nobody plays Ivanhoe in the towers because they're filled with rubble and liquor bottles. Half the playground equipment is broken.But I believe that someday Engels Park will make a comeback. In my own Philadelphia neighborhood, Gorgas Park was sad and rundown when I moved here, thirty-some years ago and today it's something to be proud of. Engels Park is a small gem -- it just needs some polishing. Which, as Ekaterinburg continues to grow more prosperous, it will eventually get. After all, somebody is keeping that locomotive painted.

And even in Cold War times it was generally acknowledged -- grudgingly, perhaps -- that the Russians were pretty good to their children.

Above: I could have taken a lot more pictures of broken things, but my heart wasn't in it.

*

Published on June 05, 2012 11:42

June 4, 2012

Pity The Poor Robot

.

It's always sad to encounter a destitute robot. Here's one I saw begging for rubles on the streets of Ekaterinburg.

And speaking of what I'm writing these days . . .

One of the many ways you can divide stories is into those that require some analytic thought on the part of the readers if they want to fully understand them and those whose intentions should be lucidly spelled out so that nobody could possibly miss them. A good example of the former would be Gene Wolfe's "Fifth Head of Cerberus," which can be reread many times without exhausting its riches. For the latter . . . One of G.K. Chesterton's Father Brown mysteries, say. Or pretty much anything by P.G. Wodehouse.

Neither mode is the "right" way to write, of course. Or the right thing to read. Sometimes you're in the mood for something difficult and involving. Other times you want something that goes down easy. Always, you want the story to be good of its kind.

I've been thinking about this particular dichotomy because I've recently finished one of each type of story and for one of them the editor (after indicating he would buy it) had a couple of questions about the plot. Had it been the for-lack-of-a-better-word art story, I probably would have gone with what I'd written. But the story in question being a for-lack-of-a-better-word entertainment, I'm going to have to spend a few hours today revising it to make sure that there's no possible room for misinterpretation.

And I conclude . . .

If there's one thing both types of story have in common -- other than that they should be written as well as possible -- it's this: When the final draft is finished, it's important to read the whole thing through out loud. It's astonishing how every mistake and infelicity of language pops out at you when you do.

*

It's always sad to encounter a destitute robot. Here's one I saw begging for rubles on the streets of Ekaterinburg.

And speaking of what I'm writing these days . . .

One of the many ways you can divide stories is into those that require some analytic thought on the part of the readers if they want to fully understand them and those whose intentions should be lucidly spelled out so that nobody could possibly miss them. A good example of the former would be Gene Wolfe's "Fifth Head of Cerberus," which can be reread many times without exhausting its riches. For the latter . . . One of G.K. Chesterton's Father Brown mysteries, say. Or pretty much anything by P.G. Wodehouse.

Neither mode is the "right" way to write, of course. Or the right thing to read. Sometimes you're in the mood for something difficult and involving. Other times you want something that goes down easy. Always, you want the story to be good of its kind.

I've been thinking about this particular dichotomy because I've recently finished one of each type of story and for one of them the editor (after indicating he would buy it) had a couple of questions about the plot. Had it been the for-lack-of-a-better-word art story, I probably would have gone with what I'd written. But the story in question being a for-lack-of-a-better-word entertainment, I'm going to have to spend a few hours today revising it to make sure that there's no possible room for misinterpretation.

And I conclude . . .

If there's one thing both types of story have in common -- other than that they should be written as well as possible -- it's this: When the final draft is finished, it's important to read the whole thing through out loud. It's astonishing how every mistake and infelicity of language pops out at you when you do.

*

Published on June 04, 2012 06:56

June 2, 2012

Lenin Gambles With History

.

One of the astonishing things about contemporary Russia is how thoroughly its public spaces have been colonized by advertising. Which leads to some odd juxtapositions. Such as the photo above of the statue of Lenin in 1905 Square, Ekaterinburg, taking a chance on our brave new world.

*

One of the astonishing things about contemporary Russia is how thoroughly its public spaces have been colonized by advertising. Which leads to some odd juxtapositions. Such as the photo above of the statue of Lenin in 1905 Square, Ekaterinburg, taking a chance on our brave new world.

*

Published on June 02, 2012 00:34

June 1, 2012

Home Again

.

If writers have one character flaw (and most people agree that this is understating the case), it is that we have a weakness for the picturesque. Which, at its worst, can make us unintentionally condescending -- "Look at the quaint Wisconsonite, with his wheel of cheese!" So I was careful not to snap pix of the street-sweepers in Ekaterinburg, even though some of them had a distinctly raffish air about them.

But I could not resist taking the above shot because it was as good as an essay on how technology gets absorbed into a culture at different rates. A besom and a cell phone! Nobody called this one.

And I am back home again . . .

It's a long trek, five-twelfths of the way around the globe. But Marianne and I made it in twenty-two hours, which is not bad time at all. It's wearying, though. So I'm going to spend the day lazing about, going through the mail, paying bills, and the like. My apologies for blogging so briefly. I'll be back in form on Monday.

*

If writers have one character flaw (and most people agree that this is understating the case), it is that we have a weakness for the picturesque. Which, at its worst, can make us unintentionally condescending -- "Look at the quaint Wisconsonite, with his wheel of cheese!" So I was careful not to snap pix of the street-sweepers in Ekaterinburg, even though some of them had a distinctly raffish air about them.

But I could not resist taking the above shot because it was as good as an essay on how technology gets absorbed into a culture at different rates. A besom and a cell phone! Nobody called this one.

And I am back home again . . .

It's a long trek, five-twelfths of the way around the globe. But Marianne and I made it in twenty-two hours, which is not bad time at all. It's wearying, though. So I'm going to spend the day lazing about, going through the mail, paying bills, and the like. My apologies for blogging so briefly. I'll be back in form on Monday.

*

Published on June 01, 2012 07:52

May 31, 2012

Ekaterinburg

.

As always, I am on the road again, this time flying home from Russia. The trip will take up most of the day and when I get home I will collapse for another day. So, while I hope to have a blog for you tomorrow, I can make no promises.

One question I was asked often on this trip was what I thought of Ekaterinburg. Specifically, what I thought of the changes that had taken place since my last visit in 2004. Well . . .

Eight years ago, Ekaterinburg was just beginning to recover from Perestroika. There was a stunned feel to the city and too much trash sifting through the park behind the opera house. There was some new construction, mostly over-glossy luxury highrise hotels for foreign businessmen come to pick over the ruins of the Soviet Union, but what stood out was all the beautiful old buildings falling to ruin. It was heartbreaking to see.

Today, Ekaterinburg is in the throes of a building boom of near-China proportions. Cars throng the streets. The old buildings -- those that haven't been torn down for the twenty-story hotels and office buildings and apartment complexes -- are being rehabbed. Restaurants have multiplied five-fold. It is no longer startling to run across a Gucci store. Expensive cars are everywhere.

"Ekaterinburg is for the experienced Russia traveler only," my guidebook said eight years ago. That's changed. They even have a tourist office! (An innovation which Moscow really ought to adopt.) On the airplane in, I chatted with a charity worker headed for Novosibersk, who said that if he could free up a week, he'd like to take a side trip here.

It all comes at a price: Traffic, loss of much architecture that should have been saved, and a corresponding loss of strangeness. Siberia comes in two varieties, a fan told me, Civilized Siberia and Wild Siberia. As Ekaterinburg, always civilized, becomes more so Wild Siberia recedes from it. On my last visit, an Old Believer gave me Xeroxes of his drawings to take to the West and a shaman, dressed in suit and tie, gave me a devil stone to unlock my potential power. Nothing like that has happened on this visit.

But I cannot and do not complain. Ekaterinburg is a beautiful and fascinating city and I'm grateful for both visits. It's a privilege to get to see it change. I hope to come here again someday, to take in Chapter Three.

Above: Sunset from my hotel window.

*

As always, I am on the road again, this time flying home from Russia. The trip will take up most of the day and when I get home I will collapse for another day. So, while I hope to have a blog for you tomorrow, I can make no promises.

One question I was asked often on this trip was what I thought of Ekaterinburg. Specifically, what I thought of the changes that had taken place since my last visit in 2004. Well . . .

Eight years ago, Ekaterinburg was just beginning to recover from Perestroika. There was a stunned feel to the city and too much trash sifting through the park behind the opera house. There was some new construction, mostly over-glossy luxury highrise hotels for foreign businessmen come to pick over the ruins of the Soviet Union, but what stood out was all the beautiful old buildings falling to ruin. It was heartbreaking to see.

Today, Ekaterinburg is in the throes of a building boom of near-China proportions. Cars throng the streets. The old buildings -- those that haven't been torn down for the twenty-story hotels and office buildings and apartment complexes -- are being rehabbed. Restaurants have multiplied five-fold. It is no longer startling to run across a Gucci store. Expensive cars are everywhere.

"Ekaterinburg is for the experienced Russia traveler only," my guidebook said eight years ago. That's changed. They even have a tourist office! (An innovation which Moscow really ought to adopt.) On the airplane in, I chatted with a charity worker headed for Novosibersk, who said that if he could free up a week, he'd like to take a side trip here.

It all comes at a price: Traffic, loss of much architecture that should have been saved, and a corresponding loss of strangeness. Siberia comes in two varieties, a fan told me, Civilized Siberia and Wild Siberia. As Ekaterinburg, always civilized, becomes more so Wild Siberia recedes from it. On my last visit, an Old Believer gave me Xeroxes of his drawings to take to the West and a shaman, dressed in suit and tie, gave me a devil stone to unlock my potential power. Nothing like that has happened on this visit.

But I cannot and do not complain. Ekaterinburg is a beautiful and fascinating city and I'm grateful for both visits. It's a privilege to get to see it change. I hope to come here again someday, to take in Chapter Three.

Above: Sunset from my hotel window.

*

Published on May 31, 2012 00:49

May 30, 2012

Andrew Matveev in the Ekaterinburg City Zoo

.

Exactly what is a dissident writer? The virtuous, if rather stuffy, political conscience of his times, right? Not necessarily.

Consider my friend Andrew Matveev. As a young man in the Soviet Union, he discovered the music of the Doors and Janis Joplin and the writings of Hunter S. Thomson. Immediately, he knew the kind of stuff he wanted to write. But when he submitted his first novel to a publishing house, the editor summoned him to his office and, jabbing his forefinger down on the typescript repeatedly, said, "This book will never be published."

Which is how Andrew was sent into internal exile, to Ekaterinburg which was at the time a closed city, and given a job as night watchman in the city zoo. "Everything was grey," he says today of those times. And, "The Communists took away a fraction of my youth and a fraction of what I might have been."

I wish I could say that Capitalism made up for all he'd been through. But we all know the world we live in doesn't operate like that. Today, Andrew Matveev makes his living through journalism, which eats up most of his writing time. But he persists. He endures. Which, for a writer, is to triumph.

And there are good times. Like the other day, when he and I sat in Gordon's Doctor Scotch Pub, drinking coffee (me) and tea (him) and talking, talking, talking. Or today when he took Marianne and me to the zoo and reminisced about the old days when the entrance to the zoo was a small wooden house, ferociously cold in winter, and the great cats at night fixed him with murderous glares and growled to let him know that it was just him and them.

This is what it meant to be a writer in the Twentieth Century, and this is the price that some of us paid.

*

Exactly what is a dissident writer? The virtuous, if rather stuffy, political conscience of his times, right? Not necessarily.

Consider my friend Andrew Matveev. As a young man in the Soviet Union, he discovered the music of the Doors and Janis Joplin and the writings of Hunter S. Thomson. Immediately, he knew the kind of stuff he wanted to write. But when he submitted his first novel to a publishing house, the editor summoned him to his office and, jabbing his forefinger down on the typescript repeatedly, said, "This book will never be published."

Which is how Andrew was sent into internal exile, to Ekaterinburg which was at the time a closed city, and given a job as night watchman in the city zoo. "Everything was grey," he says today of those times. And, "The Communists took away a fraction of my youth and a fraction of what I might have been."

I wish I could say that Capitalism made up for all he'd been through. But we all know the world we live in doesn't operate like that. Today, Andrew Matveev makes his living through journalism, which eats up most of his writing time. But he persists. He endures. Which, for a writer, is to triumph.

And there are good times. Like the other day, when he and I sat in Gordon's Doctor Scotch Pub, drinking coffee (me) and tea (him) and talking, talking, talking. Or today when he took Marianne and me to the zoo and reminisced about the old days when the entrance to the zoo was a small wooden house, ferociously cold in winter, and the great cats at night fixed him with murderous glares and growled to let him know that it was just him and them.

This is what it meant to be a writer in the Twentieth Century, and this is the price that some of us paid.

*

Published on May 30, 2012 00:26

May 29, 2012

Looking Backward, Looking Forward

.

Yesterday was Memorial Day back in the States and apparently something analogous here in Russia because when Marianne and I went to see the Black Tulip in Red Army Square, a monument to those who died in the Soviet Afghan War, we saw military people just beginning to gather for what looked to be memorial services.

I did not think Americans would be especially welcome at such an event and I did not stay. But I could not help wondering what our own Afghan War monument will look like when it's build. And I could not help hoping that, impossible though I know it is, ours will be the last monument and the last Afghan War.

And, because you wondered . . .

Why is the monument called the Black Tulip? Because that was the nickname the Soviet soldiers in Afghanistan gave to the plane that flew the bodies back home.

Here's a Russian song on the subject. If you go to YouTube, you'll find the lyrics beneath it.

Above: a closeup of the central element of the Black Tulip. Not shown are pylons to either side, each holding the names of soldiers who died in one year of the war.

*

Yesterday was Memorial Day back in the States and apparently something analogous here in Russia because when Marianne and I went to see the Black Tulip in Red Army Square, a monument to those who died in the Soviet Afghan War, we saw military people just beginning to gather for what looked to be memorial services.

I did not think Americans would be especially welcome at such an event and I did not stay. But I could not help wondering what our own Afghan War monument will look like when it's build. And I could not help hoping that, impossible though I know it is, ours will be the last monument and the last Afghan War.

And, because you wondered . . .

Why is the monument called the Black Tulip? Because that was the nickname the Soviet soldiers in Afghanistan gave to the plane that flew the bodies back home.

Here's a Russian song on the subject. If you go to YouTube, you'll find the lyrics beneath it.

Above: a closeup of the central element of the Black Tulip. Not shown are pylons to either side, each holding the names of soldiers who died in one year of the war.

*

Published on May 29, 2012 00:03

May 28, 2012

Tea With Eugeni Kasimov

.

After the usual round of gallivanting about Ekaterinburg yesterday, Marianne and I, in the company of our friend Boris Dolingo, dropped by Eugeni Kasimov's apartment. Eugeni is the head of the Urals Writers Union, which is why Boris refers to him as "my boss." He's also a very fine poet, as I can attest to on the basis of four of his poems which I've read in translation.

His apartment is . . . well, a typical writer's apartment. Writers build nests and then line them books and pictures, almost all of which have deep personal significance. He has two lovely cats whose names I will render as Moosha and Mooka, though both are almost certainly properly spelled otherwise. One of the high points of this visit to Russia is hearing Eugeni read (he's one of the best poetry readers I've ever heard; and I've hear a lot) a poem he wrote, inspired by The Iron Dragon's Daughter , while his cats prowled about his feet intently ignoring us.

We enjoyed a long literary afternoon with much talk accompanied by vodka, wine, port -- some had this and others that but nobody, as Boris joked we should, combined all three -- along with first black bread, caviar, Ukrainian spiced fat, and bowls of pelmeny, and then cup after cup of tea. We met Eugeni's charming daughter Vasilisa, for whom he once wrote a children's book. We enjoyed ourselves immensely.

And now Marianne and I are relaxing in our room in the Bolshoy Ural Hotel, resting up for more gallivanting tomorrow. So we are happy and I hope you are too.

Above: Eugeni Kasimov with a very small fraction of the books thronging his apartment.

*

After the usual round of gallivanting about Ekaterinburg yesterday, Marianne and I, in the company of our friend Boris Dolingo, dropped by Eugeni Kasimov's apartment. Eugeni is the head of the Urals Writers Union, which is why Boris refers to him as "my boss." He's also a very fine poet, as I can attest to on the basis of four of his poems which I've read in translation.

His apartment is . . . well, a typical writer's apartment. Writers build nests and then line them books and pictures, almost all of which have deep personal significance. He has two lovely cats whose names I will render as Moosha and Mooka, though both are almost certainly properly spelled otherwise. One of the high points of this visit to Russia is hearing Eugeni read (he's one of the best poetry readers I've ever heard; and I've hear a lot) a poem he wrote, inspired by The Iron Dragon's Daughter , while his cats prowled about his feet intently ignoring us.

We enjoyed a long literary afternoon with much talk accompanied by vodka, wine, port -- some had this and others that but nobody, as Boris joked we should, combined all three -- along with first black bread, caviar, Ukrainian spiced fat, and bowls of pelmeny, and then cup after cup of tea. We met Eugeni's charming daughter Vasilisa, for whom he once wrote a children's book. We enjoyed ourselves immensely.

And now Marianne and I are relaxing in our room in the Bolshoy Ural Hotel, resting up for more gallivanting tomorrow. So we are happy and I hope you are too.

Above: Eugeni Kasimov with a very small fraction of the books thronging his apartment.

*

Published on May 28, 2012 00:23

Michael Swanwick's Blog

- Michael Swanwick's profile

- 546 followers

Michael Swanwick isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.