Michael Swanwick's Blog, page 132

June 12, 2015

When Marnie Was There

.

I went to see Studio Ghibli's latest (and perhaps last) movie the other day. When Marnie Was There, despite its awkward title, is a lovely film and worthy of its legendary studio.

What's interesting is how I keep thinking of it as a non-genre film, when -- I'm sure I'm not giving anything away by telling you this -- it's actually a ghost story. Perhaps it's because ghost stories are so embedded in our culture. Perhaps it's because so many people believe in ghosts and even those who don't would like to believe in them. But unless the ghost is malevolent (in which case the story or film goes straight to horror), it's difficult to think of a ghost story as fantasy. It feels like an accepted part of our everyday worldview.

I can think of only one other fantasy sub-type that can be routinely sold and accepted as mainstream, and that's the time-travel love story. It has to be love that breaches the walls of time and (briefly, usually) unites two people who were Meant To Be Lovers. Machinery gets in the way of romance and turns the whole thing into icky sci-fi.

So that's two. Can anybody think of a third?

And a word to young writers...

If you're a natural fantasist who wants to write a mainstream novel, falling through time and in love is probably the way to go. Keep in mind, though, that you stand the same chance of getting a big paycheck as you do if you stay in genre. I've talked to any number of not-yet-famous mainstream writers who are jealous of the big advances they presume genre writers receive.

The cash is always greener on the other side of the fence.

*

I went to see Studio Ghibli's latest (and perhaps last) movie the other day. When Marnie Was There, despite its awkward title, is a lovely film and worthy of its legendary studio.

What's interesting is how I keep thinking of it as a non-genre film, when -- I'm sure I'm not giving anything away by telling you this -- it's actually a ghost story. Perhaps it's because ghost stories are so embedded in our culture. Perhaps it's because so many people believe in ghosts and even those who don't would like to believe in them. But unless the ghost is malevolent (in which case the story or film goes straight to horror), it's difficult to think of a ghost story as fantasy. It feels like an accepted part of our everyday worldview.

I can think of only one other fantasy sub-type that can be routinely sold and accepted as mainstream, and that's the time-travel love story. It has to be love that breaches the walls of time and (briefly, usually) unites two people who were Meant To Be Lovers. Machinery gets in the way of romance and turns the whole thing into icky sci-fi.

So that's two. Can anybody think of a third?

And a word to young writers...

If you're a natural fantasist who wants to write a mainstream novel, falling through time and in love is probably the way to go. Keep in mind, though, that you stand the same chance of getting a big paycheck as you do if you stay in genre. I've talked to any number of not-yet-famous mainstream writers who are jealous of the big advances they presume genre writers receive.

The cash is always greener on the other side of the fence.

*

Published on June 12, 2015 07:24

June 10, 2015

This Glitterati Life

.

Last week, I was in Laramie, Wyoming, taking a crash course in astronomy. A month ago I was wandering through China with a group of friends that included my old pals Ellen Datlow and Eileen Gunn. And today?

I'm bouncing between tapping on the keyboard and downloading papers on Messier 4.

When you're a writer, there ate four constructive types of activity you engage in, three of them falling under the heading of research. The first is wandering about, experiencing new things and learning all you can. The second is acquiring new (or, in this case, refreshing old) lore. The third is specific research for a given project.

The fourth, alas, is tapping away at the keyboard.

As a general rule, the further away you get from the actual writing, the more fun the activity is.

There is also a fifth category of activity, and that's all the business stuff: reading contracts with skepticism, cashing checks, responding to editorial queries and the like. This is even less fun than the actual writing is, which is why editors find it easier to get writers to make revisions of their work than it is to get them to provide a social security number, so they can get paid. Ironic, but true.

Above: my work in progress.

*

Published on June 10, 2015 08:12

June 8, 2015

Keeping Raven Young

.

I spent all of last week in Laramie, Wyoming, taking a refresher course in astronomy. The course was called Launch Pad and was run by Michael Brotherton, with the assistance of Christian Ready, Andrea Schwortz, and Jim Verley. It was a great deal of mental work which, incidentally, gave me much insight into my less than stellar college career.

I hear you asking: why was I there?

Berndt Heinrich wrote a book titled Mind of the Raven: Investigations and Adventures with Wolf-Birds. Which I highly recommend to anyone seriously interested in ravens. One of his observations was that young ravens are endlessly curious. Put out something odd in their habitat, and they'll poke at it, push it around, try to figure it out. Some of them die as a result of this curiosity. But the survivors have stuffed their heads with odd information about the world that will last them a lifetime.

Old ravens, those who have come of breeding age, are exactly the opposite. When they see something new in their environment, they view it with active suspicion. They won't come anywhere near it. They flee anything that smacks of innovation.

Human beings are not all that different, are we?

So that's what I was doing in the University of Wyoming. Keeping my inner raven young.

Above: There I am in front of the university's geology museum. Some things just don't change. Photo by Amy Thomson.

*

I spent all of last week in Laramie, Wyoming, taking a refresher course in astronomy. The course was called Launch Pad and was run by Michael Brotherton, with the assistance of Christian Ready, Andrea Schwortz, and Jim Verley. It was a great deal of mental work which, incidentally, gave me much insight into my less than stellar college career.

I hear you asking: why was I there?

Berndt Heinrich wrote a book titled Mind of the Raven: Investigations and Adventures with Wolf-Birds. Which I highly recommend to anyone seriously interested in ravens. One of his observations was that young ravens are endlessly curious. Put out something odd in their habitat, and they'll poke at it, push it around, try to figure it out. Some of them die as a result of this curiosity. But the survivors have stuffed their heads with odd information about the world that will last them a lifetime.

Old ravens, those who have come of breeding age, are exactly the opposite. When they see something new in their environment, they view it with active suspicion. They won't come anywhere near it. They flee anything that smacks of innovation.

Human beings are not all that different, are we?

So that's what I was doing in the University of Wyoming. Keeping my inner raven young.

Above: There I am in front of the university's geology museum. Some things just don't change. Photo by Amy Thomson.

*

Published on June 08, 2015 13:21

June 1, 2015

"Better Than Sex" Kirkus RAVES!!!

Brace yourselves, gentle readers. My brilliantly entertaining Darger & Surplus novel, Chasing the Phoenix , comes out in less than three months. Which means that, yes, I will be flogging it relentlessly. Doing so is like voting for yourself when you're on the Nebula ballot. Everybody does it, nobody is petty enough to say you shouldn't, and because it has no great effect on the outcome, it does no harm. So why not?

Also, it never hurts to let your editor know that you're doing your bit.

All of which is prologue to the fact that my novel has just received its first official review -- a starred review from Kirkus, no less.

The pullquotes to note are "witty, supple, artfully humorous, and vastly engaging" and "this one's just too good to miss."

I will not pretend that I am not happy about this.

The review in its entirety is:

CHASING THE PHOENIX [STARRED REVIEW!]

Author: Michael Swanwick

Publisher:Tor

Pages: 320

Price ( Hardcover ): $26.99

Price ( e-book ): $12.99

Publication Date: August 11, 2015

Category: Fiction

Classification: Science Fiction/Fantasy

A new entry in Swanwick's picaresque post-apocalyptic series, following Dancing with Bears (2011) and various short stories. Technological civilization collapsed long ago, the reasons for which only gradually emerge, yet Swanwick's seductive future swarms with gene-modified creatures, ancient weapons, vengeful artificial intelligences, and other contrivances that would not seem out of place in a steampunk yarn. Surplus, a genetically modified dog with the stance and intellect of a human, arrives in the Abundant Kingdom with the corpse of his friend (and fellow confidence trickster) Aubrey Darger in search of the Infallible Physician, the only agency by which Darger might be revived. They soon learn that the land's paranoid and quite possibly insane Hidden King is both ambitious to reunite the sundered kingdoms of old China and obsessed with locating his Phoenix Bride. Seeing a likely source of great wealth, our heroes attach themselves to the king's entourage, braving the skepticism of Chief Archaeological Officer White Squall (whose mission is to recover and repair ancient war machines) and Ceo Powerful Locomotive. Surplus becomes Noble Dog Warrior, while Darger declares himself to be Perfect Strategist. In turn, various persons attach themselves to the heroes, among them Capable Servant and a band of feisty horse warriors. Somehow, Surplus and Darger's intrigues and stratagems really begin to work. Or so it seems. One drawback to this otherwise witty, supple, artfully humorous, and vastly engaging yarn is the plot's broad similarity with the previous novel. Still, along with a splendid supporting cast, Swanwick offers a pair of delightful rogues whose chief flaw (like Jack Vance's celebrated Cugel the Clever, a likely inspiration) is that they're a little too crafty for their own good. Swanwick's approaching top form, and this one's just too good to miss.

And as always . . .

I'm on the road again. This time I'm off to Launch Pad in Wyoming for a weeklong crash course in astronomy. It's been (cough) years since I took a formal astronomy course and I felt that it was time to do a little catching up. The universe is a much bigger place than it was when I was in college.

I'll do my best to keep up my blog while I'm away. But, necessarily, I can make no promises.

Behave yourselves while I'm away!

*

Published on June 01, 2015 00:30

May 29, 2015

Probably the Single Coolest Science Fiction Book of the Year

.

You've probably already heard of The Three-Body Problem. When I tried to order a copy at Big Blue Marble, the friendly independent bookstore in Chestnut Hill, they told me their distributor had sold every copy they had. Then, when I called Tor to ask for a copy, my editor friend there, sounding extremely happy, told me that the book was "flying off the shelves." And of course it's currently on the Nebula and Hugo ballots. So it's not exactly obscure.

Nevertheless, I feel compelled to add a few quiet words of praise for Cixin Liu's novel, the first of a trilogy that's a best-seller in China, ably translated by American writer Ken Liu, just because it's so damnably cool.

Here's the basic premise: In a near-future China, top-level physicists are committing suicide in alarming numbers. Experimental data, it turns out, are no longer consistent. Experiments yield different results every time they are run. Physics is no longer reproducible. As a crusty old cop observes, when things get this strange, there's usually somebody making it happen.

There's a lot to like about this book: the culture and history of China, to begin with. (Did you know that it's perfectly okay now to openly criticize the Cultural Revolution?) The heavy emphasis on science for another. (An engineer of my acquaintance did grumble that there was a lot of hand-waving; but he liked the book anyway.)

Its weaknesses? It's a little old-fashioned structurally, with a great deal of characters delivering lectures on science to one another. But that's undoubtedly part of the reason for its popularity. The prose is functional, rather than beautiful. But that's a good part of the reason why it got translated in the first place..

Mostly, though, I love this book because it contains ideas that I hadn't seen before. Larry Niven's Ringworld, you'll remember, had kind of a ramshackle plot where the characters land on the eponymous artifact, wander about for a bit, and then leave. But the brilliance of the central idea made it a landmark in science fiction. The Three-Body Problem has that same virtue: original ideas.

Recommended for everyone. New writers in particular.

*

You've probably already heard of The Three-Body Problem. When I tried to order a copy at Big Blue Marble, the friendly independent bookstore in Chestnut Hill, they told me their distributor had sold every copy they had. Then, when I called Tor to ask for a copy, my editor friend there, sounding extremely happy, told me that the book was "flying off the shelves." And of course it's currently on the Nebula and Hugo ballots. So it's not exactly obscure.

Nevertheless, I feel compelled to add a few quiet words of praise for Cixin Liu's novel, the first of a trilogy that's a best-seller in China, ably translated by American writer Ken Liu, just because it's so damnably cool.

Here's the basic premise: In a near-future China, top-level physicists are committing suicide in alarming numbers. Experimental data, it turns out, are no longer consistent. Experiments yield different results every time they are run. Physics is no longer reproducible. As a crusty old cop observes, when things get this strange, there's usually somebody making it happen.

There's a lot to like about this book: the culture and history of China, to begin with. (Did you know that it's perfectly okay now to openly criticize the Cultural Revolution?) The heavy emphasis on science for another. (An engineer of my acquaintance did grumble that there was a lot of hand-waving; but he liked the book anyway.)

Its weaknesses? It's a little old-fashioned structurally, with a great deal of characters delivering lectures on science to one another. But that's undoubtedly part of the reason for its popularity. The prose is functional, rather than beautiful. But that's a good part of the reason why it got translated in the first place..

Mostly, though, I love this book because it contains ideas that I hadn't seen before. Larry Niven's Ringworld, you'll remember, had kind of a ramshackle plot where the characters land on the eponymous artifact, wander about for a bit, and then leave. But the brilliance of the central idea made it a landmark in science fiction. The Three-Body Problem has that same virtue: original ideas.

Recommended for everyone. New writers in particular.

*

Published on May 29, 2015 08:25

May 26, 2015

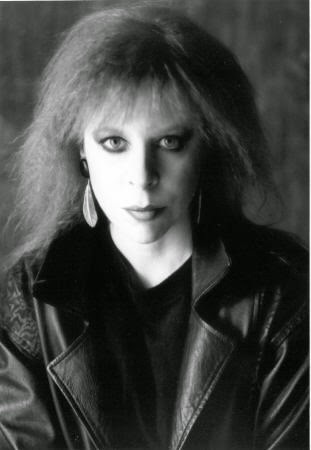

Tanith Lee, Sorceress

.

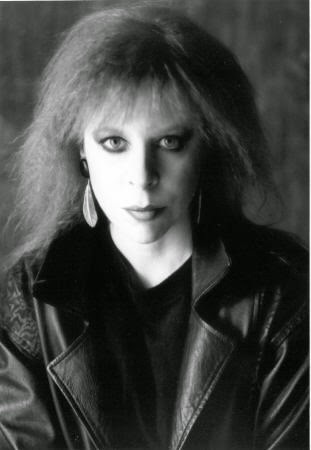

I have just now heard from a reliable source that Tanith Lee has died. This is terrible news for lovers of fantasy. Her prose was elegant, sensuous, a delight to read. There really was no other writer like her.

I never met Ms Lee, so I have no stories about her to share. So instead, I'll give you the section of my essay, "In the Tradition..." dealing with her work:

If there is one commonality among the hard fantasists, it is that they are not a prolific lot. Tanith Lee, however, is prolific. Which makes it hard to single out one work for examination. A survey of her oeuvre would necessitate the exclusion of other writers. Nor can she simply be skipped over. She is a Power, and has earned her place here.

I've chosen to focus on Lee's Arkham House collection Dreams of Dark and Light not only in the name of ruthless simplification but also because it is a rare thing for a hard fantasist to work much in short fiction (novels being the preferred length of eccentricity, and eccentricity being the name of the game) and rarer still for one individual to excel at both lengths.

Here's a quick sampler of what happens in Dreams of Dark and Light: A selkie beds a seal-hunter in trade for the pelt of her murdered son. The dying servant of an aged vampire procures for her a new lover. A writer becomes obsessed with a masked woman who may or may not be a gorgon. A young woman rejects comfort, luxury, and the fulfillment of her childhood dreams, for a demon lover. These are specifically adult fictions.

There is more to these stories than the sexual impulse. But I mention its presence because its treatment is never titillating, smirking, or borderline pornographic, as is so much fiction that purports to be erotic. Rather, it is elegant, languorous, and feverish by turns, and always tinged with danger. Which is to say that it is remarkably like the writing itself.

In "Elle Est Trois (La Morte)" three artists--a poet, a painter, a composer--are visited by avatars of Lady Death. The suicidal allure of la vie boheme, with its confusion of death, sex, poverty and the muse, has rarely been so well conveyed as here. The artists are captured as their essences, each courting death in his own way. The composer France unwittingly acknowledges this when he tells his friend Etiens Saint-Beuve, "One day such sketches will be worth sheafs of francs, boxes full of American dollars. When you are safely dead, Etiens, in a pauper's grave."

After France himself has been taken, the poet Armand Valier muses on Death's avatars (the Butcher, the Thief, the Seducer) in Lee's sorcerous prose:

This is the apotheosis of romantic decadence--sex, drugs, and death mixed into a single potent cocktail. But, lest the reader suspect her of indulging in mere literary nostalgia, Lee notes in passing that "the poet would have presented this history quite differently," by introducing a unifying device, such as a cursed ring. This sly contrasting of the story's sinuous structure with the clanking apparati of its Gothic ancestors, does more than just establish that the fiction is an improvement on antique forms. It hints (no more) that the real horror, the real beauty, the real significance of the story, is that death is universal. She is a true democrat, an unselective lover who sooner or later comes for all, aware of her or not, the reader no less than the author.

Once upon a time the Romantics elevated the emotions above reason, sought the sublime in the supernatural and the medieval, and elevated the equation of sex and death to cult status. Following generations took their machinery and put it to lesser ends, much as the forms of magic were taken over by performers of sleight-of-hand. They could do no better, for they had lost the original vision.

Lee's work is a return to sources and a rejuvenation of that original vision. It is the higher passions that matter. Viktor, the bored aristocrat in "Dark as Ink" is too wise to pursue his obsessions, and for this sin suffers a meaningless life and early death. But the eponymous heroine of "La Reine Blanche" finds redemption despite her singular regicide and unwitting betrayal of her fated love because she has stayed true to her passions. An erotic spirituality shimmers like foxfire from the living surfaces of this book.

By some readings (though not mine) these works could be classified as horror. There has long been a midnight trade between the genres, ridge-runners and embargo-breakers smuggling influences both ways across the borders. It's illegal, we are all agreed, but is it wrong? No one would dare attempt to expel the late Fritz Leiber from the Empire of the Fantastic. Yet he readily admitted that nearly all his work was, at heart, horror. Even his Fafhrd and Gray Mouser stories, though disguised by ambiguously upbeat endings and the wit and charisma of their heroes, exist in an almost Lovecraftian horror-fiction universe. In the end, the only question that matters is whether the work suits our purposes or not.

"As I supposed," says a raven in one of these tales, "your story is sad, sinister, and interesting." Exactly so. There are twenty-three stories in this volume, and I recommend them all.

Copyright 1994 by Michael Swanwick. Probably the best way to memorialize Tanith Lee would be by reading one of her books.

*

I have just now heard from a reliable source that Tanith Lee has died. This is terrible news for lovers of fantasy. Her prose was elegant, sensuous, a delight to read. There really was no other writer like her.

I never met Ms Lee, so I have no stories about her to share. So instead, I'll give you the section of my essay, "In the Tradition..." dealing with her work:

If there is one commonality among the hard fantasists, it is that they are not a prolific lot. Tanith Lee, however, is prolific. Which makes it hard to single out one work for examination. A survey of her oeuvre would necessitate the exclusion of other writers. Nor can she simply be skipped over. She is a Power, and has earned her place here.

I've chosen to focus on Lee's Arkham House collection Dreams of Dark and Light not only in the name of ruthless simplification but also because it is a rare thing for a hard fantasist to work much in short fiction (novels being the preferred length of eccentricity, and eccentricity being the name of the game) and rarer still for one individual to excel at both lengths.

Here's a quick sampler of what happens in Dreams of Dark and Light: A selkie beds a seal-hunter in trade for the pelt of her murdered son. The dying servant of an aged vampire procures for her a new lover. A writer becomes obsessed with a masked woman who may or may not be a gorgon. A young woman rejects comfort, luxury, and the fulfillment of her childhood dreams, for a demon lover. These are specifically adult fictions.

There is more to these stories than the sexual impulse. But I mention its presence because its treatment is never titillating, smirking, or borderline pornographic, as is so much fiction that purports to be erotic. Rather, it is elegant, languorous, and feverish by turns, and always tinged with danger. Which is to say that it is remarkably like the writing itself.

In "Elle Est Trois (La Morte)" three artists--a poet, a painter, a composer--are visited by avatars of Lady Death. The suicidal allure of la vie boheme, with its confusion of death, sex, poverty and the muse, has rarely been so well conveyed as here. The artists are captured as their essences, each courting death in his own way. The composer France unwittingly acknowledges this when he tells his friend Etiens Saint-Beuve, "One day such sketches will be worth sheafs of francs, boxes full of American dollars. When you are safely dead, Etiens, in a pauper's grave."

After France himself has been taken, the poet Armand Valier muses on Death's avatars (the Butcher, the Thief, the Seducer) in Lee's sorcerous prose:

. . . And then the third means to destruction, the

seductive death who visited poets in her irresistible

caressing silence, with the petals of blue flowers or

the blue wings of insects pasted on the lids of her

eyes, and: See, your flesh also, taken to mine, can

never decay. And this will be true, for the flesh of

Armand, becoming paper written over by words, will endure

as long as men can read.

And so he left the window. He prepared, carefully,

the opium that would melt away within him the iron barrier

that no longer yielded to thought or solitude or wine. And

when the drug began to live within its glass, for an instant

he thought he saw a drowned girl floating there, her hair

swirling in the smoke. . . . Far away, in another

universe, the clock of Notre Dame aux Lumineres struck

twice.

This is the apotheosis of romantic decadence--sex, drugs, and death mixed into a single potent cocktail. But, lest the reader suspect her of indulging in mere literary nostalgia, Lee notes in passing that "the poet would have presented this history quite differently," by introducing a unifying device, such as a cursed ring. This sly contrasting of the story's sinuous structure with the clanking apparati of its Gothic ancestors, does more than just establish that the fiction is an improvement on antique forms. It hints (no more) that the real horror, the real beauty, the real significance of the story, is that death is universal. She is a true democrat, an unselective lover who sooner or later comes for all, aware of her or not, the reader no less than the author.

Once upon a time the Romantics elevated the emotions above reason, sought the sublime in the supernatural and the medieval, and elevated the equation of sex and death to cult status. Following generations took their machinery and put it to lesser ends, much as the forms of magic were taken over by performers of sleight-of-hand. They could do no better, for they had lost the original vision.

Lee's work is a return to sources and a rejuvenation of that original vision. It is the higher passions that matter. Viktor, the bored aristocrat in "Dark as Ink" is too wise to pursue his obsessions, and for this sin suffers a meaningless life and early death. But the eponymous heroine of "La Reine Blanche" finds redemption despite her singular regicide and unwitting betrayal of her fated love because she has stayed true to her passions. An erotic spirituality shimmers like foxfire from the living surfaces of this book.

By some readings (though not mine) these works could be classified as horror. There has long been a midnight trade between the genres, ridge-runners and embargo-breakers smuggling influences both ways across the borders. It's illegal, we are all agreed, but is it wrong? No one would dare attempt to expel the late Fritz Leiber from the Empire of the Fantastic. Yet he readily admitted that nearly all his work was, at heart, horror. Even his Fafhrd and Gray Mouser stories, though disguised by ambiguously upbeat endings and the wit and charisma of their heroes, exist in an almost Lovecraftian horror-fiction universe. In the end, the only question that matters is whether the work suits our purposes or not.

"As I supposed," says a raven in one of these tales, "your story is sad, sinister, and interesting." Exactly so. There are twenty-three stories in this volume, and I recommend them all.

Copyright 1994 by Michael Swanwick. Probably the best way to memorialize Tanith Lee would be by reading one of her books.

*

Published on May 26, 2015 07:36

May 25, 2015

Memorial Day

.

Every year on Memorial Day, my father put on his American Legion cap and went to Memorial Day services. I remember them as always being held in cemeteries. Marianne's father, who also served in WWII, never missed a one either.

So when Marianne and I moved to Roxborough, we we careful to always show up on Memorial Day.

Back in the late Seventies and early Eighties, there wasn't much of a turnout at Gorgas Park. The Vietnam War was still fresh in people's memories. Some skipped the ceremonies because they thought we shouldn't have been in the war. Others because they thought that we should have won it.

Both missed the point. The dead are beyond politics. Those who served with them show up to remember the fallen and to honor their sacrifice. You don't have to support the particular war they served in to feel the solemnity of their loss.

National moods shift. In 2002, there was a huge turnout and some of those who were showing up for the first time were in a jingoistic mood. I remember one woman tried to start a chant of "U.S.A! U.S.A.!" The vet who was speaking gently cut her off. "How sweet those words are," he said, and went back to his eulogy. Because it wasn't a day for flag-waving but a day for remembrance.

There are lot more memorial services within walking distance today than there were back then. The big one is still in Gorgas Park. But we go to a smaller one in Leverington Cemetery. There is a memorial there to the Virginians who were massacred by British soldiers a few blocks down Ridge Avenue, a marble monument erected by the family of a nurse who died while tending to the wounded in the Civil War, stones with the names of regiments illegible from a century and a half of rain... It is a reminder of what a terrible thing history can be.

It is such a little thing to show up for a brief ceremony one day out of the year. But when it's all you can, you pretty much have no choice.

*

Every year on Memorial Day, my father put on his American Legion cap and went to Memorial Day services. I remember them as always being held in cemeteries. Marianne's father, who also served in WWII, never missed a one either.

So when Marianne and I moved to Roxborough, we we careful to always show up on Memorial Day.

Back in the late Seventies and early Eighties, there wasn't much of a turnout at Gorgas Park. The Vietnam War was still fresh in people's memories. Some skipped the ceremonies because they thought we shouldn't have been in the war. Others because they thought that we should have won it.

Both missed the point. The dead are beyond politics. Those who served with them show up to remember the fallen and to honor their sacrifice. You don't have to support the particular war they served in to feel the solemnity of their loss.

National moods shift. In 2002, there was a huge turnout and some of those who were showing up for the first time were in a jingoistic mood. I remember one woman tried to start a chant of "U.S.A! U.S.A.!" The vet who was speaking gently cut her off. "How sweet those words are," he said, and went back to his eulogy. Because it wasn't a day for flag-waving but a day for remembrance.

There are lot more memorial services within walking distance today than there were back then. The big one is still in Gorgas Park. But we go to a smaller one in Leverington Cemetery. There is a memorial there to the Virginians who were massacred by British soldiers a few blocks down Ridge Avenue, a marble monument erected by the family of a nurse who died while tending to the wounded in the Civil War, stones with the names of regiments illegible from a century and a half of rain... It is a reminder of what a terrible thing history can be.

It is such a little thing to show up for a brief ceremony one day out of the year. But when it's all you can, you pretty much have no choice.

*

Published on May 25, 2015 12:12

May 22, 2015

Alternate Waldrops

.

Why did nobody tell me about this? For two dozen years and two it's been sitting there and yet I had no idea there was such a thing as Eileen Gunn's Alternate Waldrops. Howard Waldrops, that is.

Why isn't there an Alternate Howard Waldrops Day? Why isn't it a national holiday? And what's wrong with the rest of the world? It's practically a national holiday here. So -- what? -- France is too good for Howard Waldrop? Is that even possible?

You can read the piece here.

For yet another Alternate Waldrop, you can read my and Gregory Frost's absolutely brilliant "Lock Up Your Chickens and Daughters -- H'ard and Andy Are Come to Town!" It appeared in Asimov's recently, and one of us is sure to include it in a collection someday. But in the meantime, you can read the story here.

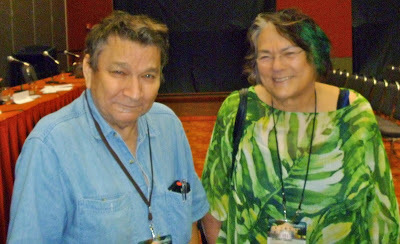

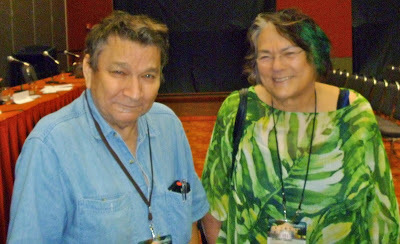

Above: I swiped this great photo of Howard and Eileen from Lawrence Person's website. If you can't steal things from a friend who can you steal them from?

*

Why did nobody tell me about this? For two dozen years and two it's been sitting there and yet I had no idea there was such a thing as Eileen Gunn's Alternate Waldrops. Howard Waldrops, that is.

Why isn't there an Alternate Howard Waldrops Day? Why isn't it a national holiday? And what's wrong with the rest of the world? It's practically a national holiday here. So -- what? -- France is too good for Howard Waldrop? Is that even possible?

You can read the piece here.

For yet another Alternate Waldrop, you can read my and Gregory Frost's absolutely brilliant "Lock Up Your Chickens and Daughters -- H'ard and Andy Are Come to Town!" It appeared in Asimov's recently, and one of us is sure to include it in a collection someday. But in the meantime, you can read the story here.

Above: I swiped this great photo of Howard and Eileen from Lawrence Person's website. If you can't steal things from a friend who can you steal them from?

*

Published on May 22, 2015 07:45

May 20, 2015

The Tao of Terry Carr

.

It is the common lot of even the best editors to be forgotten. There are exceptions, but they are few and far in between. Probably the best forgotten editor I ever knew was Terry Carr. He bought my first novel for a revival of the Ace Specials line, a short but prestigious selection that included the first novels of Kim Stanley Robinson, Lucius Shepard, Howard Waldrop and an obscurity by the name of William Gibson. What an eye for talent the man had!

Recently I received the second volume of Feast of Laughte r, an R. A. Lafferty bookzine, which I'll try to do credit to just as soon as I can find the time. Among many other gems, it contains a reprint of an interview that Tom Jackson did of Lafferty back in 1991. When asked what influence Terry had on Lafferty's work, Lafferty replied as follows:

Terry Carr taught me that a story must begin with a bang. As a consequence the first book of mine he edited and published, Past Master, had in its first paragraph:

[...] There was a clattering thunder in the street outside. [...] the clashing thunder of mechanical killers, raving and ravaging. They shook the building and were on the verge of pulling it down. They required the life and blood of one of the three men [...} now [...] within the minute.

Well, maybe all stories don't have to begin with a bang, but all Terry Carr stories had to begin with a bang of some sort. Terry also told me that 'You can lose a reader, completely and forever, in fifteen seconds. Never leave him even a fifteen-second interval without a hook to jerk him back.' Anything else Terry told me is contained in those two very good pieces of advice.

Which is every word of it God's own truth. If you doubt me, go back and reread A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man , say, or À la recherche du temps perdu. You'll see.

*

It is the common lot of even the best editors to be forgotten. There are exceptions, but they are few and far in between. Probably the best forgotten editor I ever knew was Terry Carr. He bought my first novel for a revival of the Ace Specials line, a short but prestigious selection that included the first novels of Kim Stanley Robinson, Lucius Shepard, Howard Waldrop and an obscurity by the name of William Gibson. What an eye for talent the man had!

Recently I received the second volume of Feast of Laughte r, an R. A. Lafferty bookzine, which I'll try to do credit to just as soon as I can find the time. Among many other gems, it contains a reprint of an interview that Tom Jackson did of Lafferty back in 1991. When asked what influence Terry had on Lafferty's work, Lafferty replied as follows:

Terry Carr taught me that a story must begin with a bang. As a consequence the first book of mine he edited and published, Past Master, had in its first paragraph:

[...] There was a clattering thunder in the street outside. [...] the clashing thunder of mechanical killers, raving and ravaging. They shook the building and were on the verge of pulling it down. They required the life and blood of one of the three men [...} now [...] within the minute.

Well, maybe all stories don't have to begin with a bang, but all Terry Carr stories had to begin with a bang of some sort. Terry also told me that 'You can lose a reader, completely and forever, in fifteen seconds. Never leave him even a fifteen-second interval without a hook to jerk him back.' Anything else Terry told me is contained in those two very good pieces of advice.

Which is every word of it God's own truth. If you doubt me, go back and reread A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man , say, or À la recherche du temps perdu. You'll see.

*

Published on May 20, 2015 09:55

May 19, 2015

When Lafferty Insulted Harlan

.

Raymond Aloysius Lafferty put his wrinkled hand on my left forearm and said to me, "Ellison... you are the imp of Satan."

Ever wondered what it would take to insult Harlan Ellison with impunity? We are, after all, talking about a man who is a master of vituperation, someone famously disinclined to suffer fools gladly, a fellow who, as all the old gaffers and geezers at Stratford-on-Avon agreed when asked about the character of the late, sainted Bill Shakespeare, might best be characterized as "a fast man with a comeback." There are many, many stories in the collective folklore of Fandom about people who by word or act raised up his wrath against them -- too many, perhaps, for they tend to obscure the very real brilliance of his fiction -- and with the exception of two or three that smell suspiciously like repurposed urban legends to me, Harlan comes off second in none of them.

But first, I should explain that the above italicized sentence is the opening of Ellison's introduction to the second volume of the collected stories of R. A. Lafferty, a beautiful and pricey tome which y-hight The Man with the Aura , published with (I am certain) justifiable pride by Centipede Press. So you don't have to take my word for it that Lafferty offered deathly insult to someone whose many talents include a particular talent for the discursive essay. Of which the introduction in question is an excellent example.

So am I ready to explain the second sentence of this essay -- my first, after Ellison's -- yet? No. For there must be a word or two about Lafferty himself, the forgotten giant from Tulsa, Oklahoma. Lafferty wrote like no one ever did before him, and though attempts to pastiche his style were plenteous back in the day, to my ear not a one of them truly succeeded. He came to prominence during the New Wave days, which was ironic for he was a hidebound conservative and mossbacked reactionary in all the ways that sub specie aeternitatis are of no importance at all. He faded to all but nothing (in terms of literary visibility) two decades later.

But in the early 1970s, all the writers you admire most thought he was the cat's pajamas. If I tried to explain why, we'd be here all day and still I'd be no closer to the horizon than I was when we started it. Let's just say he was the single most original writer science fiction has ever seen. This and five bucks, as they say, will get you a grande mochaccino at Starbucks, the sprinkle of cinnamon optional. When the gentlemanly business of publishing was bought up by multinationals and computerized, it was discovered that while Lafferty was beloved of God and the literati, to the masses he was tref. Nothing. He simply didn't have the numbers.

But at the time he insulted Ellison, Lafferty was at the height of his prestige. Not that that mattered. To those who care, really care about words, sales figures are nothing. All that matters is the art. And Lafferty had art coming out the yingyang.

I'm not going to give away the conclusion of Ellison's intro. He put a lot into it, buyers of this book are going to want to read it with pleasure and no spoilers, and I'm not about to step on his punchline. But I don't think it gives anything away to say that if you want to insult Harland Ellison and get away with it, it's the simplest thing in the world:

You just need to have earned enough of his respect to pull it off.

The uncommonly well-made book was issued in an edition of 300 and costs $45. Those who need this book know who they are. They, and the merely curious, can find Centipede's page on it here

Above: Was I trying to pull off an imitation of Harlan Ellison's famously inimitable style here? No, I was not. But I was trying my hand at the discursive essay. This stuff is harder to pull of than it looks -- and I never for a moment thought it looked easy at all.

*

Raymond Aloysius Lafferty put his wrinkled hand on my left forearm and said to me, "Ellison... you are the imp of Satan."

Ever wondered what it would take to insult Harlan Ellison with impunity? We are, after all, talking about a man who is a master of vituperation, someone famously disinclined to suffer fools gladly, a fellow who, as all the old gaffers and geezers at Stratford-on-Avon agreed when asked about the character of the late, sainted Bill Shakespeare, might best be characterized as "a fast man with a comeback." There are many, many stories in the collective folklore of Fandom about people who by word or act raised up his wrath against them -- too many, perhaps, for they tend to obscure the very real brilliance of his fiction -- and with the exception of two or three that smell suspiciously like repurposed urban legends to me, Harlan comes off second in none of them.

But first, I should explain that the above italicized sentence is the opening of Ellison's introduction to the second volume of the collected stories of R. A. Lafferty, a beautiful and pricey tome which y-hight The Man with the Aura , published with (I am certain) justifiable pride by Centipede Press. So you don't have to take my word for it that Lafferty offered deathly insult to someone whose many talents include a particular talent for the discursive essay. Of which the introduction in question is an excellent example.

So am I ready to explain the second sentence of this essay -- my first, after Ellison's -- yet? No. For there must be a word or two about Lafferty himself, the forgotten giant from Tulsa, Oklahoma. Lafferty wrote like no one ever did before him, and though attempts to pastiche his style were plenteous back in the day, to my ear not a one of them truly succeeded. He came to prominence during the New Wave days, which was ironic for he was a hidebound conservative and mossbacked reactionary in all the ways that sub specie aeternitatis are of no importance at all. He faded to all but nothing (in terms of literary visibility) two decades later.

But in the early 1970s, all the writers you admire most thought he was the cat's pajamas. If I tried to explain why, we'd be here all day and still I'd be no closer to the horizon than I was when we started it. Let's just say he was the single most original writer science fiction has ever seen. This and five bucks, as they say, will get you a grande mochaccino at Starbucks, the sprinkle of cinnamon optional. When the gentlemanly business of publishing was bought up by multinationals and computerized, it was discovered that while Lafferty was beloved of God and the literati, to the masses he was tref. Nothing. He simply didn't have the numbers.

But at the time he insulted Ellison, Lafferty was at the height of his prestige. Not that that mattered. To those who care, really care about words, sales figures are nothing. All that matters is the art. And Lafferty had art coming out the yingyang.

I'm not going to give away the conclusion of Ellison's intro. He put a lot into it, buyers of this book are going to want to read it with pleasure and no spoilers, and I'm not about to step on his punchline. But I don't think it gives anything away to say that if you want to insult Harland Ellison and get away with it, it's the simplest thing in the world:

You just need to have earned enough of his respect to pull it off.

The uncommonly well-made book was issued in an edition of 300 and costs $45. Those who need this book know who they are. They, and the merely curious, can find Centipede's page on it here

Above: Was I trying to pull off an imitation of Harlan Ellison's famously inimitable style here? No, I was not. But I was trying my hand at the discursive essay. This stuff is harder to pull of than it looks -- and I never for a moment thought it looked easy at all.

*

Published on May 19, 2015 14:47

Michael Swanwick's Blog

- Michael Swanwick's profile

- 546 followers

Michael Swanwick isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.