Clyde Dee's Blog, page 4

December 12, 2020

Support Healing from Psychosis Versus Imposing Social Control!

When a person has a break from reality there is often a sense of urgent rush. Most people think that if this does not get treated with antipsychotic medication immediately, that grave and progressive brain damage will ensue. Many supporters fear a degenerative process that will render the person with an institutionalized shuffle through poverty the rest of their life.

This article is written for the loving supporter or social worker. It invites you to explore what it’s like to better learn the world of your loved one! It helps you gain strategies for how to handle the relationship.

With the public mental health system, images of crowded psychiatric emergency rooms, the loved one terrorized navigating crowded streets, violent police handcuff restraints, rapid tranquilization needle sticks, jail time, or substandard warehousing barracks may come to mind.

I will convey all these realities as mechanisms of the state. They either neglect or set up the person in the break to be forced back into consensus reality. It often becomes a punitive and damaging process.

Ultimately, I view the goal of the state to be about social control, not healing and recovery. It can become about saving money and making the afflicted impotent. It can become about endless submission, silence and perpetuation of lies.

At the same time there are times when political pressure to conform to consensus reality do help a person improve their behavior. Improving one’s behavior can help a person minimize their risk of escalations of trauma via social punishment. It can be better than nothing. Many can learn lessons from abuse and improve their circumstances to heal.

Still this usually takes safety and security so that the victim can reflect upon what’s happened. This may enable many victims to grow between the cracks in the concrete.

However, often safety is not promoted via things like homelessness, jail time, or warehousing. These realities may perpetuate a state of emergency.

Efficacy of the State’s Social Control Model:

Still, in America, state social control that guides behavioral change has a low efficacy in terms of promoting recovery. It gets to be more a part of the problem than the solution. Degenerative decline results in roughly a quarter of the people who undergo such treatment. For example, social myths and stereotypes leave most people thinking that degenerative decline is the standard for schizophrenia. When such social myths are maintained in one’s mind, it can seem like social control is the only option.

Still, as I suggested above, stints of incarceration can result in an increase in compliance with consensus reality. Half the population who experience a break associated with schizophrenia will move towards recovery within ten years of trial and error effort to raise their spirit and fit in.

In this culture, when incarceration and trauma happen, all is not lost. I believe we can learn healing alternatives instead of nurse-ratcheting up social control. Medication can be used in helpful manners at different times. However, many who continue to apply social control do learn, and repeatedly confirm, that healing is not likely.

To promote healing instead of social control, a person must understand, normalize, and navigate the break. This doesn’t happen often enough in the system because most people fear to be curious about psychosis.

Society doesn’t understand and so rarely do our psychologists and social workers! People must do the work on their own. They may do so with untrained interns/workers who may listen to burnt out managers. Many such interns/workers are focused on mainstream judgments of their collegiate education. Many managers are there to make money/justify services. This does not apply to all of us! Hence it takes ten years.

Meanwhile, the basics myths are maintained. Most are trained not to reinforce the delusions. Others fear they will catch the disease if they listen. Still others fear retraumatizing the respondent and making them angry.

There are ways around that by validating conspiracies so keep reading.

Conversely, it’s becoming known that systems that promote open dialogue and a socialist philosophy can greatly improve these kinds of rough statistics so that all can recover. If one studies open dialogue as its been applied in Finland, one learns that treating psychosis as though it is real and attempting to heal it via skilled communication works. Open dialogue, honoring the tradition of the wounded healer, empowers the victim as the prime leader and promotes healing and radically different results.

It’s a known fact that third world subsistence economies also do vastly better in promoting recovery than modern ones. While this is a fact that promotes generalized philosophic reflection, it is still worth noting.

Still, the norm among loved ones and social workers is to promote the medical model view and support social control. Consider the view of NAMI, the National Alliance for Mental Illness. It spends money and uses power to promote the concept that all mental illness is a (primarily eugenic) brain disease.

Why Do We Choose Social Control over Healing?

There are several reasons that recovery via social control is so vastly promoted in the United States. A major reason is that people are trained to be fearful of such realities is because of stigmatizing media, college texts, dubious twin studies, and sketchy studies that promote the role of genes which get disproportionately amplified in the media.

Let’s not forget we live in America, in the land of the free where the concept of government intelligence and propaganda is currently clouded by the cultural delusion of democracy, generalized propaganda of the old two-party system, family’s scapegoating neurodiversity, and the psychopharmocology industry’s imperfect understanding of mental “illness.” Currently we are all waiting to see if democracy will be toppled by a ruthless dictatorship so I do say these things with a sense of irony.

Concurrently, there is a very poor, medicalized understanding of what psychosis is. Hence, the average person will set boundaries with the person who starts talking openly about hearing voices or referencing conspiracies about being targeted or enlightened. Ridicule, social rejection, and turning the person over to the state’s care becomes the only option.

Too many people in the state and the public invalidate the trauma that ensues while social control measures occur. So many people feel it is justified. Just as the haves are known to hate the have-nots, the state’s goal becomes simple: spend as little money on the victim as possible, get them to fill unskilled labor markets, and don’t let them speak out against our cultural delusions.

It can feel like there is not much left for loved ones and good social workers to do besides support the effort to socially control the person they love and wait and see if they will recover.

Some Basic Alternatives to Social Control:

In order to promote healing from psychosis, it becomes very important to become uniquely adept at listening, validating, and contributing without getting confused, combative or dissociated. Asking the right kinds of questions and normalizing conspiracies and adding to them helps the person can realize they are not alone. Trust building and assessing is also very important.

Also, assisting your loved one in adhering to the requirements of work or making it possible for them to continue to socially network and have a social life is also an important investment. As L.A. psychiatrist, Mark Raggins suggests, work, or building relationships (to which I’d include studying spiritual traditions) are ways to teach us social skills, not incarceration.

Indeed, research in the United States behind Dartmouth’s IPS (Individualized Placement Services) model of vocational rehab suggests that a self-directed effort to conform to work with support is a real way to achieve behavioral earmarks. Hence a job is provided until the subject fails, and then another job is found and maintained until it is lost. Keeping the person moving through the job situation and adhering to social dictates until they can master the needed behaviors to keep a job—this is now proven via research to be the way to go.

Perhaps we can add this mentality to social and spiritual connectivity and enhance outcomes even further.

The majority of persons with psychosis want to work, have friends, and believe in god to avoid a life of poverty. It is a good way for many to motivate and comply with rules. But it requires support and might need to be coupled with therapy

Avoiding Pitfalls:

Sure, some social workers and perhaps some families may form secret societies that monitor their loved ones. These secret societies (like treatment teams in the hospital or family discussions/gossip) can easily be abused and defame the person with psychosis. I think family members and social workers must realize that when they do this, they mirror the oppression of other secret societies that may be real and may have something to do with their loved one’s awareness and ire.

Thus, when family or social workers recognize that they can function as agents of the state (police, FBI, corporations, prison gangs, fraternities, the Illuminati, the Ukrainian mafia, the military, religious cults and others) they can be open, communicative, and transparent about the secret societies in which they participate. This can greatly enhance trust and avoid pitfalls.

This might include taking responsibility to learn about things the person has experienced that pertain to you that you don’t feel are accurate. Consider monitoring the things your voice has expressed to your loved one (as auditory hallucinations). Then try to see the reality of what they are saying so you can confirm ways the communication is and isn’t valid. Always lead with the way it is valid.

Focus on What Healing Interactions Look Like?

In this manner, consider the opportunity that you have when the person enduring a break from reality gets mad and confronts you, their loved one, with something of which you are sure you’re not guilty.

I’d strongly recommend that before you confront that person with the reality check of your innocence, that you consider whether you want to avoid falling into the role of social control.

If you find yourself determined to prove your innocence, and confront your loved ones with your facts, I want to suggest they may see this as just another social control effort. It is a lot of the same kind of stuff they get in the state midst the jails, hospitals, and shelters that might not be appreciated

In other words, I am saying that defending yourself is a power play. It may gain you some compliance with consensus reality, but it also puts you at risk of diminishing trust between you and your loved one. In some cases, it can be a form of gaslighting.

In contrast, I suggest you take this intensely emotional situation, a potentially false accusation, and keep the goal of healing in mind. Instead of asserting the power play, let the loved one explore all the experiences that the person who is in a break has had that indicate your guilt. Then, communicate and clarify without invalidating.

When This Does Not Go as Planned:

I know this is an exceedingly simple suggestion! Let us not forget that asking the above question is a real test of the amount of trust that exists between the two of you.

For example, when I don’t trust the person who asks me to prove what I am saying with examples, I find I am often rendered speechless. It can be hard to put words to those experiences when you know they will be shot down.

In other words, unless I trust you and feel safe to speak about a misperception or two, words that define my experiences elude me.

Thus, if you are a social worker or a loved one and you don’t get any information, it is likely that you have so rejected your loved one’s reality so much over the years that they are afraid to communicate with you. It is likely that they have no hope you would ever understand.

I believe working towards a healing relationship involves cultural curiosity into your love one’s experience. If you can get yourself trusted to the point where you can explore all your loved ones associated experiences, then I think you are on the road towards healing them.

If you don’t have that kind of relationship with your loved one, focus on trying to get there and forget about the false accusation. Explore with curiosity other kinds of experience they have had.

Understanding the culture of your loved one’s psychosis to the point where you can admit the ways they are right about you, is far more likely to reality check them in a more healing manner and really move your relationship forward.

Adapting Your Strategies:

Also, it stands to be noted that people who experience psychosis often come from distinctive cultures, have different needs, and approach a break with different moods and core beliefs. In my experience I believed I was being persecuted by secret. illegal societies overseen by the government. Other people can have vastly different experiences with secret societies.

For example, some may believe they are being spiritually aided by secret Cabals like elite police and or politicians on their mission. Perhaps not all people experience social control in their family of origins the way I did. But still, you can inquire about euphoric experiences that your loved one may have had. Even so, you don’t want to come down on the forceful side of your loved one’s punitive state administrators.

Consider how some positive spiritual experiences really don’t need to be healed, true. But still there are those positive experiences have consequences that must be curbed. Consider what happens, for example, when they make the person descend from heaven back into a living hell on earth. Staying on earth can be a challenge.

Still, researching and giving them information about the negative aspects of the Cabals that tricked them and sent them soaring can help them make better decisions.

This may involve envisioning a world in which they do not have to endure social control to force them to come back down. Helping them takes communication and rational, healthy choices. It becomes more about reviewing the consequences that the state will impose if they go down that road. It become about mitigating those realities and maintain your collaborative standing.

Either way, delineating yourself from the mechanisms of control that may have led to trauma or got in the way of healing is an important thing to do! As a parent or as a social worker this may involve changing the historical role you’ve taken with your loved one.

This means, instead of telling them what to do, you should consider exploring their experiences.

Takeaways:

Do not forget that psychosis, special messages, or a break from reality is a collection of experiences. When you force your loved ones to defy their experiences and accept your reality via reality check, it is really about you imposing consensus reality on them and it puts you on the side of social control. They may know better.

I feel this becomes about your power. Ultimately it puts them down. When you do this, they will recognize this and it may trigger trauma from their run ins with the state. Thus, differentiating yourself from the state becomes an important strategy.

Helping them heal is not really not about you. Helping your loved one heal is about using your relationship to help them to navigate consensus reality in ways that they can achieve their hopes and dreams. If you care about them and their relationship with you, adapt a collaborative approach to their experiences. This is far more important than them respecting consensus reality which might be full of ignorance and propagandas.

Supporting their autonomy and freedom is needed. Learning about the mistakes you made can also be important. Give them transparent information about what you have said and done on their behalf. Ask them how they would like you to assist, then communicate.

It’s true, doing what they say and working on their behalf does require boundaries. Even if you are a lawyer, you can’t help them beat the state, only evade it.

Differentiate yourself from the social control and discriminatory laws (or the rampant corruption of those that are nondiscriminatory, like the ADA.) You really don’t want to be on the side of marginalizing your loved one!

The post Support Healing from Psychosis Versus Imposing Social Control! appeared first on Redefining "Psychosis".

Support Healing from Psychosis Verses Imposing Social Control!

When a person has a break from reality there is often a sense of urgent rush. Most people think that if this does not get treated with antipsychotic medication immediately, that grave and progressive brain damage will ensue. Many supporters fear a degenerative process that will render the person with an institutionalized shuffle through poverty the rest of their life.

This article is written for the loving supporter or social worker. It invites you to explore what it’s like to better learn the world of your loved one! It helps you gain strategies for how to handle the relationship.

With the public mental health system, images of crowded psychiatric emergency rooms, the loved one terrorized navigating crowded streets, violent police handcuff restraints, rapid tranquilization needle sticks, jail time, or substandard warehousing barracks may come to mind.

I will convey all these realities as mechanisms of the state. They either neglect or set up the person in the break to be forced back into consensus reality. It often becomes a punitive and damaging process.

Ultimately, I view the goal of the state to be about social control, not healing and recovery. It can become about saving money and making the afflicted impotent. It can become about endless submission, silence and perpetuation of lies.

At the same time there are times when political pressure to conform to consensus reality do help a person improve their behavior. Improving one’s behavior can help a person minimize their risk of escalations of trauma via social punishment. It can be better than nothing. Many can learn lessons from abuse and improve their circumstances to heal.

Still this usually takes safety and security so that the victim can reflect upon what’s happened. This may enable many victims to grow between the cracks in the concrete.

However, often safety is not promoted via things like homelessness, jail time, or warehousing. These realities may perpetuate a state of emergency.

Efficacy of the State’s Social Control Model:

Still, in America, state social control that guides behavioral change has a low efficacy in terms of promoting recovery. It gets to be more a part of the problem than the solution. Degenerative decline results in roughly a quarter of the people who undergo such treatment. For example, social myths and stereotypes leave most people thinking that degenerative decline is the standard for schizophrenia. When such social myths are maintained in one’s mind, it can seem like social control is the only option.

Still, as I suggested above, stints of incarceration can result in an increase in compliance with consensus reality. Half the population who experience a break associated with schizophrenia will move towards recovery within ten years of trial and error effort to raise their spirit and fit in.

In this culture, when incarceration and trauma happen, all is not lost. I believe we can learn healing alternatives instead of nurse-ratcheting up social control. Medication can be used in helpful manners at different times. However, many who continue to apply social control do learn, and repeatedly confirm, that healing is not likely.

To promote healing instead of social control, a person must understand, normalize, and navigate the break. This doesn’t happen often enough in the system because most people fear to be curious about psychosis.

Society doesn’t understand and so rarely do our psychologists and social workers! People must do the work on their own. They may do so with untrained interns/workers who may listen to burnt out managers. Many such interns/workers are focused on mainstream judgments of their collegiate education. Many managers are there to make money/justify services. This does not apply to all of us! Hence it takes ten years.

Meanwhile, the basics myths are maintained. Most are trained not to reinforce the delusions. Others fear they will catch the disease if they listen. Still others fear retraumatizing the respondent and making them angry.

There are ways around that by validating conspiracies so keep reading.

Conversely, it’s becoming known that systems that promote open dialogue and a socialist philosophy can greatly improve these kinds of rough statistics so that all can recover. If one studies open dialogue as its been applied in Finland, one learns that treating psychosis as though it is real and attempting to heal it via skilled communication works. Open dialogue, honoring the tradition of the wounded healer, empowers the victim as the prime leader and promotes healing and radically different results.

It’s a known fact that third world subsistence economies also do vastly better in promoting recovery than modern ones. While this is a fact that promotes generalized philosophic reflection, it is still worth noting.

Still, the norm among loved ones and social workers is to promote the medical model view and support social control. Consider the view of NAMI, the National Alliance for Mental Illness. It spends money and uses power to promote the concept that all mental illness is a (primarily eugenic) brain disease.

Why Do We Choose Social Control over Healing?

There are several reasons that recovery via social control is so vastly promoted in the United States. A major reason is that people are trained to be fearful of such realities is because of stigmatizing media, college texts, dubious twin studies, and sketchy studies that promote the role of genes which get disproportionately amplified in the media.

Let’s not forget we live in America, in the land of the free where the concept of government intelligence and propaganda is currently clouded by the cultural delusion of democracy, generalized propaganda of the old two-party system, family’s scapegoating neurodiversity, and the psychopharmocology industry’s imperfect understanding of mental “illness.” Currently we are all waiting to see if democracy will be toppled by a ruthless dictatorship so I do say these things with a sense of irony.

Concurrently, there is a very poor, medicalized understanding of what psychosis is. Hence, the average person will set boundaries with the person who starts talking openly about hearing voices or referencing conspiracies about being targeted or enlightened. Ridicule, social rejection, and turning the person over to the state’s care becomes the only option.

Too many people in the state and the public invalidate the trauma that ensues while social control measures occur. So many people feel it is justified. Just as the haves are known to hate the have-nots, the state’s goal becomes simple: spend as little money on the victim as possible, get them to fill unskilled labor markets, and don’t let them speak out against our cultural delusions.

It can feel like there is not much left for loved ones and good social workers to do besides support the effort to socially control the person they love and wait and see if they will recover.

Some Basic Alternatives to Social Control:

In order to promote healing from psychosis, it becomes very important to become uniquely adept at listening, validating, and contributing without getting confused, combative or dissociated. Asking the right kinds of questions and normalizing conspiracies and adding to them helps the person can realize they are not alone. Trust building and assessing is also very important.

Also, assisting your loved one in adhering to the requirements of work or making it possible for them to continue to socially network and have a social life is also an important investment. As L.A. psychiatrist, Mark Raggins suggests, work, or building relationships (to which I’d include studying spiritual traditions) are ways to teach us social skills, not incarceration.

Indeed, research in the United States behind Dartmouth’s IPS (Individualized Placement Services) model of vocational rehab suggests that a self-directed effort to conform to work with support is a real way to achieve behavioral earmarks. Hence a job is provided until the subject fails, and then another job is found and maintained until it is lost. Keeping the person moving through the job situation and adhering to social dictates until they can master the needed behaviors to keep a job—this is now proven via research to be the way to go.

Perhaps we can add this mentality to social and spiritual connectivity and enhance outcomes even further.

The majority of persons with psychosis want to work, have friends, and believe in god to avoid a life of poverty. It is a good way for many to motivate and comply with rules. But it requires support and might need to be coupled with therapy

Avoiding Pitfalls:

Sure, some social workers and perhaps some families may form secret societies that monitor their loved ones. These secret societies (like treatment teams in the hospital or family discussions/gossip) can easily be abused and defame the person with psychosis. I think family members and social workers must realize that when they do this, they mirror the oppression of other secret societies that may be real and may have something to do with their loved one’s awareness and ire.

Thus, when family or social workers recognize that they can function as agents of the state (police, FBI, corporations, prison gangs, fraternities, the Illuminati, the Ukrainian mafia, the military, religious cults and others) they can be open, communicative, and transparent about the secret societies in which they participate. This can greatly enhance trust and avoid pitfalls.

This might include taking responsibility to learn about things the person has experienced that pertain to you that you don’t feel are accurate. Consider monitoring the things your voice has expressed to your loved one (as auditory hallucinations). Then try to see the reality of what they are saying so you can confirm ways the communication is and isn’t valid. Always lead with the way it is valid.

Focus on What Healing Interactions Look Like?

In this manner, consider the opportunity that you have when the person enduring a break from reality gets mad and confronts you, their loved one, with something of which you are sure you’re not guilty.

I’d strongly recommend that before you confront that person with the reality check of your innocence, that you consider whether you want to avoid falling into the role of social control.

If you find yourself determined to prove your innocence, and confront your loved ones with your facts, I want to suggest they may see this as just another social control effort. It is a lot of the same kind of stuff they get in the state midst the jails, hospitals, and shelters that might not be appreciated

In other words, I am saying that defending yourself is a power play. It may gain you some compliance with consensus reality, but it also puts you at risk of diminishing trust between you and your loved one. In some cases, it can be a form of gaslighting.

In contrast, I suggest you take this intensely emotional situation, a potentially false accusation, and keep the goal of healing in mind. Instead of asserting the power play, let the loved one explore all the experiences that the person who is in a break has had that indicate your guilt. Then, communicate and clarify without invalidating.

When This Does Not Go as Planned:

I know this is an exceedingly simple suggestion! Let us not forget that asking the above question is a real test of the amount of trust that exists between the two of you.

For example, when I don’t trust the person who asks me to prove what I am saying with examples, I find I am often rendered speechless. It can be hard to put words to those experiences when you know they will be shot down.

In other words, unless I trust you and feel safe to speak about a misperception or two, words that define my experiences elude me.

Thus, if you are a social worker or a loved one and you don’t get any information, it is likely that you have so rejected your loved one’s reality so much over the years that they are afraid to communicate with you. It is likely that they have no hope you would ever understand.

I believe working towards a healing relationship involves cultural curiosity into your love one’s experience. If you can get yourself trusted to the point where you can explore all your loved ones associated experiences, then I think you are on the road towards healing them.

If you don’t have that kind of relationship with your loved one, focus on trying to get there and forget about the false accusation. Explore with curiosity other kinds of experience they have had.

Understanding the culture of your loved one’s psychosis to the point where you can admit the ways they are right about you, is far more likely to reality check them in a more healing manner and really move your relationship forward.

Adapting Your Strategies:

Also, it stands to be noted that people who experience psychosis often come from distinctive cultures, have different needs, and approach a break with different moods and core beliefs. In my experience I believed I was being persecuted by secret. illegal societies overseen by the government. Other people can have vastly different experiences with secret societies.

For example, some may believe they are being spiritually aided by secret Cabals like elite police and or politicians on their mission. Perhaps not all people experience social control in their family of origins the way I did. But still, you can inquire about euphoric experiences that your loved one may have had. Even so, you don’t want to come down on the forceful side of your loved one’s punitive state administrators.

Consider how some positive spiritual experiences really don’t need to be healed, true. But still there are those positive experiences have consequences that must be curbed. Consider what happens, for example, when they make the person descend from heaven back into a living hell on earth. Staying on earth can be a challenge.

Still, researching and giving them information about the negative aspects of the Cabals that tricked them and sent them soaring can help them make better decisions.

This may involve envisioning a world in which they do not have to endure social control to force them to come back down. Helping them takes communication and rational, healthy choices. It becomes more about reviewing the consequences that the state will impose if they go down that road. It become about mitigating those realities and maintain your collaborative standing.

Either way, delineating yourself from the mechanisms of control that may have led to trauma or got in the way of healing is an important thing to do! As a parent or as a social worker this may involve changing the historical role you’ve taken with your loved one.

This means, instead of telling them what to do, you should consider exploring their experiences.

Takeaways:

Do not forget that psychosis, special messages, or a break from reality is a collection of experiences. When you force your loved ones to defy their experiences and accept your reality via reality check, it is really about you imposing consensus reality on them and it puts you on the side of social control. They may know better.

I feel this becomes about your power. Ultimately it puts them down. When you do this, they will recognize this and it may trigger trauma from their run ins with the state. Thus, differentiating yourself from the state becomes an important strategy.

Helping them heal is not really not about you. Helping your loved one heal is about using your relationship to help them to navigate consensus reality in ways that they can achieve their hopes and dreams. If you care about them and their relationship with you, adapt a collaborative approach to their experiences. This is far more important than them respecting consensus reality which might be full of ignorance and propagandas.

Supporting their autonomy and freedom is needed. Learning about the mistakes you made can also be important. Give them transparent information about what you have said and done on their behalf. Ask them how they would like you to assist, then communicate.

It’s true, doing what they say and working on their behalf does require boundaries. Even if you are a lawyer, you can’t help them beat the state, only evade it.

Differentiate yourself from the social control and discriminatory laws (or the rampant corruption of those that are nondiscriminatory, like the ADA.) You really don’t want to be on the side of marginalizing your loved one!

The post Support Healing from Psychosis Verses Imposing Social Control! appeared first on Redefining "Psychosis".

October 25, 2020

The Challenges of Finding Community Support When You Have A History of Exile

Maintaining a sense of community support is precious when you struggle a history of exile. In my life words like “schizophrenia” and “anorexia” mixed with periods of institutional incarceration have resulted in alienation, trauma, and exile. It’s been twenty years since my most recent incarceration for “schizophrenia” and it remains very hard to find community support. I find the pattern of being othered replicates itself.

Healing from my most extreme experience of exile, “schizophrenia,” has involved outreach into many communities. I’d like to recommend community outreach because it’s been full of great experiences and rewards. But to be honest, although it is needed, it often results in repeated triggers that bring on emotional distress and familiar thinking patterns. Persisting has been very important as has finding ways to process those negative experiences and finding primary support.

Ultimately, I have learned to honor the communities where I have sensed safety and support that have enabled me to thrive and be authentic. These communities have enabled me to persist when I get triggered and feel othered. I am writing to share my perceptions about persisting through exile and to honor those places that have assisted in healing and soothing that sense of exile.

Starting with the Origins of Feeling Targeted:

This sense of exile I recently traced back in memory during an EMDR training. I remember being at a family friend’s farm and finding horns that fell off baby cattle. I remember being told that’s what happens to baby cattle as they grow, they lose their horns. It must have been Halloween, after my birthday at age of two or three. I remember the melancholy of feeling like one of those horns. The gray misty rain, the green pastures, the mud, the need to hold onto the horn that I identified with, those images have come back to me during periods of exile.

The family story is that the farm owner hid with me during hide and seek. No one could find us Otherwise I remember only traipses of what I presume to be the day. A glimpse into a crowded, festive room, the visual of a costumed witch, and the contrast, the grey, billowing fog, the misty rain.

I remember the owner asking me at a later point if I remember the day. I remember his sense of intensity. I remember feeling revolted when he touched my ass as I rode on his back. I remember feeling perplexed seeing him interact with his children who were far older than me. I remain only suspicion about what may have happened.

The main reason I am suspicious is that I have recaptured other dissociated memories about other sex abuse events that went along with family stories. Those stories help explain behavior and actions that were always frowned upon. Clothing myself in the shower and refusing to let anyone see me in the buff, not sleeping for a year on end, starving, sacrificing myself for people I love, these actions would result in incarceration and labels.

Ultimately, I only have a sense that the intensity of my reactions against sex abuse goes back further. For example, I just can’t imagine that I would dissociate so easily fondled in a tub at the age of nine and later, to behave so cowardly at the age of seventeen in the face of an atrocity that I am not even sure is real.

Sense of Exile:

Because I was “so sensitive” and perhaps because I frowned in all the pictures taken of me, I was exiled from my family and the school community in which I was raised. Male anorexia ultimately had a lot to do with this. Who starves themselves like that? It diminished a great deal of constructive work! I stopped being seen.

However, when I trace my history back at the school there was always a sense of rejection. Always a good student, I was nearly not admitted because I cut paper in an unusual manner. Luckily my parents worked there and were willing to have me repeat a year. There were early reports of how I failed to connect with other kids. There was the year I spent a lot of time home and sick. There was the fact that the kids picked on and bullied me. When I rebelled against the other kids, I got sent to counseling. I got psychological testing.

My sense of exile was clear in my decision to thumb my nose at the private school expectations of an expensive collegiate utopia. They published that I was going to a good school in the yearbook, regardless. However, I chose a local inner-city commuter college campus where I could afford to divorce myself from my parent’s influence. I would end up creating the space to hide daily binging and purging. I studied and worked the whole time. I never wasted time to go to a single college party. I graduated with a 3.9 GPA.

I fought a sense of exile among my graduate school affiliates, but I fought for acceptance. I was exiled at most jobs and among my twenty-something associates. I moved west where I knew very few people.

Extracting Pockets of Support:

I write to highlight the importance of finding the places where I did find a sense of acceptance. I owe them gratitude and vie to give back. I have developed and survived in spite of exile. I am more fortunate than many in that I have a career and have developed a sense of primary support.

I was first hospitalized at Child Guidance Center with whom Salvador Minuchin termed “kids from the slums.” I am relieved to say that in the face of what I consider to be significant institutional abuse, I did find streetwise kids had more compassion and acceptance for me than cohorts at private school.

Likewise, in college, working under the table at an inner-city Korean owned deli fifty hours a week through the spank of summer, I was profoundly touched by the fact that the community accepted me. They didn’t care if I was skinny and afraid of food. Meanwhile support and acceptance from cohorts continued to elude me as I entered professional positions.

For the last eighteen years I have found support working for psychiatric patients in a psychiatric unit. It’s true I have been less likely to feel supported by colleagues who called the clients, “crazies” or have took action to have me removed. But once again in the face of institutional abuse, I found community members heard my stories once I grew secure enough to tell them. It was with the clientele community that my mindful spontaneity and facilitation skills developed. I may have been a disrespected droid at family reunions and mainstream events, but I found myself again in the hospital back ward.

Support in the community gives you that sense of being known, respected and belonging. It is an important part of healing and human development. And yet to promote safety, the nature of many communities is that they set standards of behavior or social discourse that govern that sense of belonging. I have found that being fond of and accepted in one context can preclude one from fitting into another.

The road to rediscovering that sense of belonging can certainly be a long and winding one!

The Exile that Resulted from Battling Institutional Hypocrisy:

When I moved to the west coast, I decided that the mainstream needed to know how homeless and disabled people suffer. I was setting up services in a notorious section 8 housing complex. I alerted the newspapers. While it’s arguable I had the experience and capacity to understand the consequences of this prior, I had been taught by a mainstream therapist that if I thought corruption was real, I was paranoid.

It was the era of the psychopharmacology professional and the psychotherapy establishment that monitored me fronted kindness, yet predicted that I would be in and out of the hospital the rest of my life to any semblance of family support system that remained.

My coping strategy was to ignore corruption and work hard in the face of it. Housing Authority officials tried to bribe me by offering me as many tickets as I wanted to a music festival. I didn’t want to be paranoid and think it was a bribe, so I turned around and invited the whole community of residents that they serviced. I requested over a hundred tickets for the residents and was given twenty-four.

I have since accepted that the uninvestigated killing that alarmed me go with the territory in housing authorities, inner-city, and poor-community realities. It’s taken me a long time to accept. I had to go homeless and be an indentured servant for some time.

In my view, we are all a part of perpetuating those realities and decisions. The lure of fast money and soldiering results in a steady stream of death that is not often noted. Many people understand the injustice that happens, but they also know it isn’t safe to shine a light on it. Those that do end up in prison, dead, or unable to find work.

With unobserved rage from getting beat up in the WTO Protest and feeling ashamed for having run away from an incestuous rape, I was one bad ass who didn’t care. I was like Serpico! When I was threatened and told that curiosity killed the cat, I retorted, “Yes, but the cat has nine lives!”

As I started to believe I was being followed, I stopped taking medication and started to understand corruption better. I reached out to my one remaining college friend with a nefarious history and he made a credible threat. Still, I didn’t believe him. I tried to escape to Canada and was intercepted by police.

In fact, they were following me. It’s just that no one believed me.

Understanding the Reality of How American Society Maintains Control:

Being kicked out of the circle or rejected by the majority of the group often gets perpetuated by group leaders who either volunteer or get paid to manage. They vie to control the business and stay in power via controlling behavior and negotiating norms.

Whether done by the FBI, social service employers, educators, unions, lawyers or heads of the family fortunes, crime ring bosses, managers will go to great lengths to control and shape your behavior regardless of laws and justice. I have come to believe that much of it is about maintaining cultural delusions about wealth and privilege.

Thus, people who refuse to conform are pushed out and exiled. This can happen easily if you are not corrupt and are targeted by the community. It can also happen if you are too corrupt and targeted.

People have ways of sniffing out your history of belonging or failure to do so. They may look at the color of your skin or your gender or manners, or friends and presume the culture and experiences you have be subjected to and decide if they want you around.

For example, I believe that as a social services worker, being a productive and effective healer and promoting justice is a good way to get targeted. Clinics are there to make money and control costs, and arguably to control people. Input a little healing, and you become a threat to some people with six figure salaries.

It seems a good way to frame this is that you must agree to toque reefer, but must agree not to toque too much of it. Toque too much and you become a burner or addict. No toque, and one becomes an exiled joke. I feel its arguable that this was the quintessential dilemma that governed acceptance in American culture during the X generation. When Bill Clinton said, “but I didn’t inhale,” it clarified a lot. He promoted the very large Housing Authority company, with whom I was contracted to work, as a model of urban development. I knew that but I still alerted the press.

I must admit that I presume the toque, no toque dilemma happens at many sleep-away colleges and other developmental institutions like the military. I avoided this stage of life by living in a roach infested apartment and working under the table. This way I could live skinny and heal without being further targeted and shamed for being a thin man.

Some Historical Context:

Maybe in other generations it was different. In American history at one point it was more about accepting slavery or genocide. To fit in, one must sip the tea. One must go corrupt, just not too much so. Thus, Thomas Jefferson was cool, but hid his pedophilia exploits so as not to go too far. That’s a real American hero, yeah! He got to coauthor the American Constitution.

Makes you wonder what the history books will say about this era? When law and order is about preserving the Jeffery Epstein way of life via the execution of black men in the inner city, you’ve got to wonder! Perhaps this is what America First is all about. Donald Trump did say he could kill someone down on some avenue in broad daylight and his supporters would still vote for him. I have to say, I think he knew what he was talking about.

On the other hand, I would suggest that Donald Trump is transparent about the realities of social control and the feudal oligarchy we have all stupidly called American democracy. All the defenders of the dumb shit authored by Thomas Jefferson and other feudal pimps really believe in the law and constitutional democracy. I work hard to expose lies and cultural delusions, but I sure hope they can protect us from the mind state of a fascist xenophobe.

Perhaps it all boils back to the quintessential American dilemma, do I toque reefer!

“Take it easy, but take it!” This odd quote extracted from one of the bizarre cinematographic dissociative sequences in the movie, Midnight Cowboy still eludes me all these years later. I still say, no.

People like me who repeatedly get exiled and cannot find community might struggle with a sense of shame, trauma and the ongoing exile of pain.

The Science of Trauma and Surviving Exile

Indeed, when we turn to advances in neuroscience to understand what heals trauma: we end up with several different sects about how to create safety and resources. Some proponents identify community support as being important. Thus, in my local EMDR sect, people or things that have served as wise, protective, or nurturing support emerge as necessary resources to address the unthinkable.

The basic concept is to take inventory of good relationships that have existed and create community that you can bring with you to revisit victimization and help you through can be very transformative. Of course, some of these relationships can be with mythical fictional characters or public figures like artists, tv personalities. Or (gulp) politicians who are admirable (if that is possible.) For example, I have realized that Midnight Cowboy’s character Joe Buck is a personal resource for me. “Well, I am not a for-real Cowboy, but I sure am one hell of a stud.”

Taking a deeper dive into resourcing, I am learning that there are many ways to create a safe environment. Indeed, sometimes using mindfulness techniques and meditations can help create safety between the therapist and client. Thus, creating safety can form the basis for community support.

Taking the risk to listen and reflect on what the person experiences might be and help them feel safe and in the window of tolerance when they revisit traumatic images like the gray billows of misty rain, the green pastures, the mud and the cow horns.

Using mindfulness exercises is another way to build resources and keep the person in the window of tolerance. Then, using desensitization or bilateral stimulation and encouraging the person to reprocess that trauma or sense of exile can give people the tools to broaden their sense of safety and sense of support.

The result is that the sense of exile does not get triggered and new community support becomes attainable. Thus, people who attack you politically don’t trigger you into that sense of exile. Thus, you remember the community that accepts you and you avoid the tendency to dissociate and withdraw.

Keep Persisting!

I believe powerful community managers of many sorts will continue to exile you if your experience does not fit the mold they want to see or the realities that they have championed and the power of their salaries. Hacienda owners will attack you with all the power they have when you have done nothing wrong. Maybe it all boils down to the fact that you just don’t want to toque reefer for them, I don’t know.

Ultimately being exiled from their community doesn’t mean you should give up. The more you persist and utilize those communities that do support you, even if they are just in spirit, the less power those community managers have to exile you.

Furthermore, as they treat you like you don’t matter, are invisible, are inferior or are deficient, it gives you the opportunity to practice healing in the face of your original form of exile. You persist and reprocess and perhaps continue to champion the communities of support that have in fact been there for you.

The past year and a half as the community of support that I have worked for has been under assault. Managers say the county wants to create a new system. I tend to see it as another gentrification, race and class war cloaked in mental health reform.

Managers threatened closure and there was a massive exodus of many of the competent counselors of color with lesser tenure. Additionally, the one manager who supported me, was removed from power. Many of the clients gave up their treatment.

Indeed, I have witnessed yet again top down change imposed on the community has been very devastating for community members. I have seen this happen repeatedly in the hacienda system.

I have tended to view many layers of mismanagement. Ultimately, I believe plans have shifted towards blaming the unit’s failings it on the workers and layoffs. The inequity of work is stunning. The atmosphere is: keep one’s productivity high, and get targeted. My theory is that it will make it harder to fire us if we are productive. I have persisted and prayed, but have started up a private practice to protect myself if the cuts in fact prevail.

This week there has been a strike and the power that has mismanaged and harmed the community is reportedly going to be replaced. I still don’t know what this is going to mean for the community.

I have kept my memory of inner-city support in my heart and fought to maintain my productivity. Perhaps I am only clinging on to a baby cow horn in the misty rain. I have documented the work of the community. I worked with them for twelve years to create my redefining “psychosis” therapy platform. They are its architects and they have always deserved better.

I could write about ways I feel blacklisted and betrayed, but I am persisting to maintain community with love in my heart. I feel so touched as to encourage the reader to keep reaching for new community! Things may change.

I believe in peer support and not in involuntary medication. I have fought for these changes for our community for years. I have brought in peer counselors and they worked well. But when change is imposed in a top down manner, communities dwindle and the point is missed. Let change happen regardless of which top down political fool got in the latest punch.

I have heard that my boss of many years who supported hard work and good client care, says, keep fighting. He seems to have come around on the issue of peer support in his years of knowing me.

Me, I am just persisting as I always have done. Perhaps one day all those communities that have seemed to be turned against me will change. Maybe I will recapture a memory and realize that I am truly delusional. Until then, I will continue to persist and call out our cultural delusions.

The post The Challenges of Finding Community Support When You Have A History of Exile appeared first on Redefining "Psychosis".

The Challenges of Maintaining Community Support on the Hacienda of the Mental Health System:

Maintaining a sense of community support is precious when you struggle a history of exile. In my life words like “schizophrenia” and “anorexia” mixed with periods of institutional incarceration have resulted in alienation, trauma, and exile. It’s been twenty years since my most recent incarceration for “schizophrenia” and it remains very hard to find community support. I find the pattern of being othered replicates itself.

Healing from my most extreme experience of exile, “schizophrenia,” has involved outreach into many communities. I’d like to recommend community outreach because it’s been full of great experiences and rewards. But to be honest, although it is needed, it often results in repeated triggers that bring on emotional distress and familiar thinking patterns. Persisting has been very important as has finding ways to process those negative experiences and finding primary support.

Ultimately, I have learned to honor the communities where I have sensed safety and support that have enabled me to thrive and be authentic. These communities have enabled me to persist when I get triggered and feel othered. I am writing to share my perceptions about persisting through exile and to honor those places that have assisted in healing and soothing that sense of exile.

Starting with the Origins of Feeling Targeted:

This sense of exile I recently traced back in memory during an EMDR training. I remember being at a family friend’s farm and finding horns that fell off baby cattle. I remember being told that’s what happens to baby cattle as they grow, they lose their horns. It must have been Halloween, after my birthday at age of two or three. I remember the melancholy of feeling like one of those horns. The gray misty rain, the green pastures, the mud, the need to hold onto the horn that I identified with, those images have come back to me during periods of exile.

The family story is that the farm owner hid with me during hide and seek. No one could find us Otherwise I remember only traipses of what I presume to be the day. A glimpse into a crowded, festive room, the visual of a costumed witch, and the contrast, the grey, billowing fog, the misty rain.

I remember the owner asking me at a later point if I remember the day. I remember his sense of intensity. I remember feeling revolted when he touched my ass as I rode on his back. I remember feeling perplexed seeing him interact with his children who were far older than me. I remain only suspicion about what may have happened.

The main reason I am suspicious is that I have recaptured other dissociated memories about other sex abuse events that went along with family stories. Those stories help explain behavior and actions that were always frowned upon. Clothing myself in the shower and refusing to let anyone see me in the buff, not sleeping for a year on end, starving, sacrificing myself for people I love, these actions would result in incarceration and labels.

Ultimately, I only have a sense that the intensity of my reactions against sex abuse goes back further. For example, I just can’t imagine that I would dissociate so easily fondled in a tub at the age of nine and later, to behave so cowardly at the age of seventeen in the face of an atrocity that I am not even sure is real.

Sense of Exile:

Because I was “so sensitive” and perhaps because I frowned in all the pictures taken of me, I was exiled from my family and the school community in which I was raised. Male anorexia ultimately had a lot to do with this. Who starves themselves like that? It diminished a great deal of constructive work! I stopped being seen.

However, when I trace my history back at the school there was always a sense of rejection. Always a good student, I was nearly not admitted because I cut paper in an unusual manner. Luckily my parents worked there and were willing to have me repeat a year. There were early reports of how I failed to connect with other kids. There was the year I spent a lot of time home and sick. There was the fact that the kids picked on and bullied me. When I rebelled against the other kids, I got sent to counseling. I got psychological testing.

My sense of exile was clear in my decision to thumb my nose at the private school expectations of an expensive collegiate utopia. They published that I was going to a good school in the yearbook, regardless. However, I chose a local inner-city commuter college campus where I could afford to divorce myself from my parent’s influence. I would end up creating the space to hide daily binging and purging. I studied and worked the whole time. I never wasted time to go to a single college party. I graduated with a 3.9 GPA.

I fought a sense of exile among my graduate school affiliates, but I fought for acceptance. I was exiled at most jobs and among my twenty-something associates. I moved west where I knew very few people.

Extracting Pockets of Support:

I write to highlight the importance of finding the places where I did find a sense of acceptance. I owe them gratitude and vie to give back. I have developed and survived in spite of exile. I am more fortunate than many in that I have a career and have developed a sense of primary support.

I was first hospitalized at Child Guidance Center with whom Salvador Minuchin termed “kids from the slums.” I am relieved to say that in the face of what I consider to be significant institutional abuse, I did find streetwise kids had more compassion and acceptance for me than cohorts at private school.

Likewise, in college, working under the table at an inner-city Korean owned deli fifty hours a week through the spank of summer, I was profoundly touched by the fact that the community accepted me. They didn’t care if I was skinny and afraid of food. Meanwhile support and acceptance from cohorts continued to elude me as I entered professional positions.

For the last eighteen years I have found support working for psychiatric patients in a psychiatric unit. It’s true I have been less likely to feel supported by colleagues who called the clients, “crazies” or have took action to have me removed. But once again in the face of institutional abuse, I found community members heard my stories once I grew secure enough to tell them. It was with the clientele community that my mindful spontaneity and facilitation skills developed. I may have been a disrespected droid at family reunions and mainstream events, but I found myself again in the hospital back ward.

Support in the community gives you that sense of being known, respected and belonging. It is an important part of healing and human development. And yet to promote safety, the nature of many communities is that they set standards of behavior or social discourse that govern that sense of belonging. I have found that being fond of and accepted in one context can preclude one from fitting into another.

The road to rediscovering that sense of belonging can certainly be a long and winding one!

The Exile that Resulted from Battling Institutional Hypocrisy:

When I moved to the west coast, I decided that the mainstream needed to know how homeless and disabled people suffer. I was setting up services in a notorious section 8 housing complex. I alerted the newspapers. While it’s arguable I had the experience and capacity to understand the consequences of this prior, I had been taught by a mainstream therapist that if I thought corruption was real, I was paranoid.

It was the era of the psychopharmacology professional and the psychotherapy establishment that monitored me fronted kindness, yet predicted that I would be in and out of the hospital the rest of my life to any semblance of family support system that remained.

My coping strategy was to ignore corruption and work hard in the face of it. Housing Authority officials tried to bribe me by offering me as many tickets as I wanted to a music festival. I didn’t want to be paranoid and think it was a bribe, so I turned around and invited the whole community of residents that they serviced. I requested over a hundred tickets for the residents and was given twenty-four.

I have since accepted that the uninvestigated killing that alarmed me go with the territory in housing authorities, inner-city, and poor-community realities. It’s taken me a long time to accept. I had to go homeless and be an indentured servant for some time.

In my view, we are all a part of perpetuating those realities and decisions. The lure of fast money and soldiering results in a steady stream of death that is not often noted. Many people understand the injustice that happens, but they also know it isn’t safe to shine a light on it. Those that do end up in prison, dead, or unable to find work.

With unobserved rage from getting beat up in the WTO Protest and feeling ashamed for having run away from an incestuous rape, I was one bad ass who didn’t care. I was like Serpico! When I was threatened and told that curiosity killed the cat, I retorted, “Yes, but the cat has nine lives!”

As I started to believe I was being followed, I stopped taking medication and started to understand corruption better. I reached out to my one remaining college friend with a nefarious history and he made a credible threat. Still, I didn’t believe him. I tried to escape to Canada and was intercepted by police.

In fact, they were following me. It’s just that no one believed me.

Understanding the Reality of How American Society Maintains Control:

Being kicked out of the circle or rejected by the majority of the group often gets perpetuated by group leaders who either volunteer or get paid to manage. They vie to control the business and stay in power via controlling behavior and negotiating norms.

Whether done by the FBI, social service employers, educators, unions, lawyers or heads of the family fortunes, crime ring bosses, managers will go to great lengths to control and shape your behavior regardless of laws and justice. I have come to believe that much of it is about maintaining cultural delusions about wealth and privilege.

Thus, people who refuse to conform are pushed out and exiled. This can happen easily if you are not corrupt and are targeted by the community. It can also happen if you are too corrupt and targeted.

People have ways of sniffing out your history of belonging or failure to do so. They may look at the color of your skin or your gender or manners, or friends and presume the culture and experiences you have be subjected to and decide if they want you around.

For example, I believe that as a social services worker, being a productive and effective healer and promoting justice is a good way to get targeted. Clinics are there to make money and control costs, and arguably to control people. Input a little healing, and you become a threat to some people with six figure salaries.

It seems a good way to frame this is that you must agree to toque reefer, but must agree not to toque too much of it. Toque too much and you become a burner or addict. No toque, and one becomes an exiled joke. I feel its arguable that this was the quintessential dilemma that governed acceptance in American culture during the X generation. When Bill Clinton said, “but I didn’t inhale,” it clarified a lot. He promoted the very large Housing Authority company, with whom I was contracted to work, as a model of urban development. I knew that but I still alerted the press.

I must admit that I presume the toque, no toque dilemma happens at many sleep-away colleges and other developmental institutions like the military. I avoided this stage of life by living in a roach infested apartment and working under the table. This way I could live skinny and heal without being further targeted and shamed for being a thin man.

Some Historical Context:

Maybe in other generations it was different. In American history at one point it was more about accepting slavery or genocide. To fit in, one must sip the tea. One must go corrupt, just not too much so. Thus, Thomas Jefferson was cool, but hid his pedophilia exploits so as not to go too far. That’s a real American hero, yeah! He got to coauthor the American Constitution.

Makes you wonder what the history books will say about this era? When law and order is about preserving the Jeffery Epstein way of life via the execution of black men in the inner city, you’ve got to wonder! Perhaps this is what America First is all about. Donald Trump did say he could kill someone down on some avenue in broad daylight and his supporters would still vote for him. I have to say, I think he knew what he was talking about.

On the other hand, I would suggest that Donald Trump is transparent about the realities of social control and the feudal oligarchy we have all stupidly called American democracy. All the defenders of the dumb shit authored by Thomas Jefferson and other feudal pimps really believe in the law and constitutional democracy. I work hard to expose lies and cultural delusions, but I sure hope they can protect us from the mind state of a fascist xenophobe.

Perhaps it all boils back to the quintessential American dilemma, do I toque reefer!

“Take it easy, but take it!” This odd quote extracted from one of the bizarre cinematographic dissociative sequences in the movie, Midnight Cowboy still eludes me all these years later. I still say, no.

People like me who repeatedly get exiled and cannot find community might struggle with a sense of shame, trauma and the ongoing exile of pain.

The Science of Trauma and Surviving Exile

Indeed, when we turn to advances in neuroscience to understand what heals trauma: we end up with several different sects about how to create safety and resources. Some proponents identify community support as being important. Thus, in my local EMDR sect, people or things that have served as wise, protective, or nurturing support emerge as necessary resources to address the unthinkable.

The basic concept is to take inventory of good relationships that have existed and create community that you can bring with you to revisit victimization and help you through can be very transformative. Of course, some of these relationships can be with mythical fictional characters or public figures like artists, tv personalities. Or (gulp) politicians who are admirable (if that is possible.) For example, I have realized that Midnight Cowboy’s character Joe Buck is a personal resource for me. “Well, I am not a for-real Cowboy, but I sure am one hell of a stud.”

Taking a deeper dive into resourcing, I am learning that there are many ways to create a safe environment. Indeed, sometimes using mindfulness techniques and meditations can help create safety between the therapist and client. Thus, creating safety can form the basis for community support.

Taking the risk to listen and reflect on what the person experiences might be and help them feel safe and in the window of tolerance when they revisit traumatic images like the gray billows of misty rain, the green pastures, the mud and the cow horns.

Using mindfulness exercises is another way to build resources and keep the person in the window of tolerance. Then, using desensitization or bilateral stimulation and encouraging the person to reprocess that trauma or sense of exile can give people the tools to broaden their sense of safety and sense of support.

The result is that the sense of exile does not get triggered and new community support becomes attainable. Thus, people who attack you politically don’t trigger you into that sense of exile. Thus, you remember the community that accepts you and you avoid the tendency to dissociate and withdraw.

Keep Persisting!

I believe powerful community managers of many sorts will continue to exile you if your experience does not fit the mold they want to see or the realities that they have championed and the power of their salaries. Hacienda owners will attack you with all the power they have when you have done nothing wrong. Maybe it all boils down to the fact that you just don’t want to toque reefer for them, I don’t know.

Ultimately being exiled from their community doesn’t mean you should give up. The more you persist and utilize those communities that do support you, even if they are just in spirit, the less power those community managers have to exile you.

Furthermore, as they treat you like you don’t matter, are invisible, are inferior or are deficient, it gives you the opportunity to practice healing in the face of your original form of exile. You persist and reprocess and perhaps continue to champion the communities of support that have in fact been there for you.

The past year and a half as the community of support that I have worked for has been under assault. Managers say the county wants to create a new system. I tend to see it as another gentrification, race and class war cloaked in mental health reform.

Managers threatened closure and there was a massive exodus of many of the competent counselors of color with lesser tenure. Additionally, the one manager who supported me, was removed from power. Many of the clients gave up their treatment.

Indeed, I have witnessed yet again top down change imposed on the community has been very devastating for community members. I have seen this happen repeatedly in the hacienda system.

I have tended to view many layers of mismanagement. Ultimately, I believe plans have shifted towards blaming the unit’s failings it on the workers and layoffs. The inequity of work is stunning. The atmosphere is: keep one’s productivity high, and get targeted. My theory is that it will make it harder to fire us if we are productive. I have persisted and prayed, but have started up a private practice to protect myself if the cuts in fact prevail.

This week there has been a strike and the power that has mismanaged and harmed the community is reportedly going to be replaced. I still don’t know what this is going to mean for the community.

I have kept my memory of inner-city support in my heart and fought to maintain my productivity. Perhaps I am only clinging on to a baby cow horn in the misty rain. I have documented the work of the community. I worked with them for twelve years to create my redefining “psychosis” therapy platform. They are its architects and they have always deserved better.

I could write about ways I feel blacklisted and betrayed, but I am persisting to maintain community with love in my heart. I feel so touched as to encourage the reader to keep reaching for new community! Things may change.

I believe in peer support and not in involuntary medication. I have fought for these changes for our community for years. I have brought in peer counselors and they worked well. But when change is imposed in a top down manner, communities dwindle and the point is missed. Let change happen regardless of which top down political fool got in the latest punch.

I have heard that my boss of many years who supported hard work and good client care, says, keep fighting. He seems to have come around on the issue of peer support in his years of knowing me.

Me, I am just persisting as I always have done. Perhaps one day all those communities that have seemed to be turned against me will change. Maybe I will recapture a memory and realize that I am truly delusional. Until then, I will continue to persist and call out our cultural delusions.

The post The Challenges of Maintaining Community Support on the Hacienda of the Mental Health System: appeared first on Redefining "Psychosis".

October 19, 2020

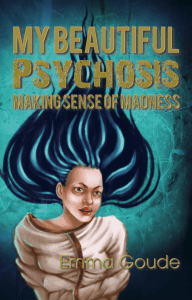

How Writing Helped Me Make Sense Of Madness, By Emma Goude

When I came out of hospital, after my first psychotic episode in 1996, aged 27, I felt compelled to write about my experiences. I used to have romantic notions of madness, was the first sentence of what, I didn’t realise at the time, would become My Beautiful Psychosis. Reading it now, it doesn’t sound like me: I never use the word ‘notions’ for a start. And the narrative voice was a little self pitying but it was part of the process of recovery.

When I was in hospital, I didn’t realise that I was experiencing psychosis. To me it felt like a spiritual awakening. I couldn’t understand why the doctors thought differently. They weren’t the ones on the inside of it and didn’t even ask me what I was experiencing so how could they know. I wrote because I needed to communicate. I felt so unseen, so pathologised and labeled. I was no longer a ‘normal’ person; I was a mental health service user. I wanted to right the wrongs that had been done to me in the name of psychiatry and tell my story as a form of complaint. The motivation to write was to share what a terrible time I’d had. But injustice and feeling misunderstood was just the top layer. There were deeper elements at play.

Apart from a poem about my pony that was printed in Pony Magazine when I was about 12, I had made zero attempts at writing. Teachers sometimes read allowed my work to the rest of the class so I had a natural talent. I didn’t admit to myself that I wanted to be a writer until I married one. I was privileged enough to witness up close someone going through the publishing process. It seemed doable.

Psychosis gave me something important to write about. I’m not a novelist: I find it difficult to make things up so memoir became my medium. It was a while before I figured out whether My Beautiful Psychosis was a novelised memoir or just a memoir. I would have loved to have been a novelist but I realised I needed to make it clear that my story was a true one. This was essential for the message to have the impact that I wanted it to have.

That brings me to the next layer. I have written My Beautiful Psychosis because the mental health services have got it so badly wrong. I not only need to put the record straight and tell my version of the story, I need to change how people see psychosis so that we can better treat it. The psychiatric service is not working. It is failing people, leaving them to live compromised lives instead of helping them to heal. We have accepted this situation for too long. It is time for a change.

In order to do that, we have to find new ways of looking at psychosis and new ways of treating it. So what is the current definition of psychosis? An official definition might go something like this: psychosis is a mental disorder, which causes you to lose touch with reality. You might see, hear, or believe things that aren’t real.

The perception of psychosis as being out of touch with reality is at best arrogant and at worst, false. For a start, there is no way of knowing what ‘reality’ actually is. It is something the brain constructs. Cats see everything blue but that does not make them deluded. It makes them better hunters. There is no reason why consensus reality of humans is any more real than cats. It is simply the one that humans have evolved to perceive in order to best function in our world. Perhaps there is another animal that sees reality more clearly than us.

An experiment shows that people with schizophrenia, the condition involving repeated psychoses, are actually able to perceive more accurately than so called normal people. It uses the Hollow Mask Illusion and involves identifying whether an image of a mask is concave or convex. All the participants with schizophrenia could distinguish between the two types of photos, whereas control volunteers without the condition were fooled 99 per cent of the time. ‘Normal’ perception is not something we can even trust as accurate.

During my own personal experiences of psychosis, I was able to see auras around objects and people, in real life and onscreen. I heard a voice, I can only describe as angelic, tell me that I was beautiful. I knew about certain traumatic events from childhood that I had repressed and forgotten. I saw a sparkler of light appear and form a figure of eight shape, the infinity sign, before disappearing again. I had memories from past lives play out with certain people around me. I could hear incongruent thoughts that people were thinking but denied, which I thought was their unconscious mind. They were being nice on the surface but it was simply a fake cover up for their socially unacceptable negative thoughts beneath.

Even in times when I was not experiencing psychosis, I have had some unusual experiences that would be interpreted by our modern material reductionist view as not being real. I saw a golden ribbon of light come from my belly button and attach itself to the duster that I was holding. I have also felt the energy of spirits inside my body communicating to me how they had died, by taking the shape of the weapon that had killed them. Each time I acknowledged their death, they sent love into my heart as thanks before moving on. I have also communicated with dolphins, psychically. There is no way we can prove that any of this in not real. Unfortunately the onus is on me to prove that it is and that is not possible either.

To say a person is out of touch with reality is to ignore the validity of the reality that they are in touch with. This is not only disempowering, it fails to celebrate the journey that the person is on, albeit in their alternate reality. It is also, more tragically, a missed opportunity.