Kurtis Scaletta's Blog, page 6

August 9, 2015

Hope from Evolutionary Biology

[W]ithin groups selfish individuals beat altruistic individuals, but groups of altruists beat groups of selfish individuals.

E. O. Wilson, “Evolution and Our Inner Conflict“

Filed under: Miscellaneous Tagged: altruism, e o wilson

July 31, 2015

The Three-footed Squirrel

True story: a few weeks ago I was picking up medicine for my cat and on the way back to the car I saw a three-footed squirrel. One of its hind feet had been severed; the wound where it used to be was kind of scabbed over and the squirrel was making do, hobbling along, gathering scraps of food from an overflowing garbage can, watching the world more warily than most squirrels do, but not especially tragic.

I knew I wanted to write about this plucky rodent. I thought of allusions that might tie in: the famous poem about the Scot and the field mouse; a squirrel that was an ironic icon of traffic safety when I was a child living in England. I recalled a crippled beggar I saw in Rome at age seven, how I bawled later, and how my parents yelled at me… one of my most palpable memories, but one I’ve written about futilely so many times it no longer has heat.

I never did write about it because I failed to come up with a narrative frame, something the squirrel would be “about” in the grand scheme of things. I gave fleeting glances in subsequent days as I drove by that building (used to be a grocery store, now vacant and fenced off), but gradually forgot.

Such is the plight of the bush-league memoirist, of which the blogger is a kind. I want to make meaning of my experiences, but fail sometimes to see theme lurking behind a scene.

I thought of that squirrel today because there’s a conversation about what people choose to think and write about. Here is an example of something trivial that I nevertheless cared about, and wanted to write about, no doubt in a week of mudslides and mass shootings that I received with tragedy-saturated numbness. Squirrels are less significant than humans, I know, and not even an endangered species. But God forgive me, I briefly gave a damn about a small thing.

Filed under: Miscellaneous

July 24, 2015

To Improve Upon Silence

There’s a saying you’ve probably seen or heard before, in some form:

Before you say something, ask yourself: Is it true? Is it kind? Is it necessary?

Ironically, this is the sort of wisdom that is captioned onto a photo, say, of a statue of the Buddha or a gurgling grotto, and posted on Facebook or Twitter where it will float along a bilious stream of untruth, unkindness, and non-necessity. But it is worth considering. I have been frustrated with how little currency truth and value have when we enter the online world; I’ve seen some of the kindest people I know disparage kindness; I’ve seen people say outright that the truth of a thing is beside the point. I have thought of this proverb when seeing waves of outrage and thought, “I would settle for any one.”

Researching the origins of the quote (Quaker school tract from the turn of the last century? Ancient midrash? Who knows?) I came across a different construct:

Before you say something, ask yourself: Is it true? Is it kind? Does it improve upon silence?

Does it improve upon silence?

This reveals the compulsion that leads good people to be unkind and, at best, unconcerned about knowing the full truth. They want to fill the silence. Silence is associated with oppression and victimization; to be told to be kind and true is interpreted as a demand to be silent, sometimes by people who have long been silenced. I get all that, and yet I’m wary of the conclusion. Is any noise at all preferable to silence?

But this also creates a rubric for what construes necessity. It’s the best test there is for the value of an utterance. Does it improve upon silence?

Sometimes I sit one out, and let a cycle of fury rage and fizzle without me. But I realize now that failing to join in the fray is not silence, even without the public apophasis that I am not going to comment on [story of the week] because of my judiciousness and gallantry. Silence is something other than strategic noiselessness.

Sometimes I sit one out, and let a cycle of fury rage and fizzle without me. But I realize now that failing to join in the fray is not silence, even without the public apophasis that I am not going to comment on [story of the week] because of my judiciousness and gallantry. Silence is something other than strategic noiselessness.

I have begun to think of this silence as a natural resource to be treasured and protected: the silence of a calm lake at dawn; the silence of a mind at rest; the silence of listening and waiting. This silence, like clean water and star-lit skies, is harder and harder to find. It is also a value: a decision to seek silence inside and out, to turn of all the screens and quiet your own mind. And, if such a place be found, to protect it.

My mother didn’t work for the last ten years of her life, and spent much of that (waking) time watching television, particularly the 24-hour news networks, which sometimes blared different channels in different rooms of the house. Entering her house was to enter a churning noise machine, her own running commentary mixed in with that of various TV pundits and reporters. She took up every news cycle ready to be angry and outspoken. I now see the noise as a part of her sickness, and her inability for her mind to heal. But it’s also a metaphor for my own mind, clattering with noise, my inner muttering monologist struggling to be heard over the din. I can only quiet my mind by choice: walks at dawn, drives with the car stereo muted, the time before sleep where I listen to the breaths of family and pets around me and the murmurings of the house itself.

The proverb takes on power when it is not about manners; it is about soul-nurturing. Is this thing I am about to say worth disrupting my own calm? If I believe in silence as a natural resource, is it now worth plundering? What whispers of the universe might I hear, if I remain silent?

Filed under: Miscellaneous Tagged: kindness, silence, social media, truth

July 15, 2015

Go Set a Record Straight

Forget what you’ve read and/or assume about Go Set a Watchman. It is not a “first draft” of To Kill a Mockingbird. And while it may not narrowly meet the definition of sequel, it sure reads like one: a new story, set decades later, with most of the same characters. Indeed, it really feels like the writer of this book assumes readers are familiar with the events and characters of To Kill a Mockingbird. Yes, there are inconsistencies, huge ones, which indicate it was not written after final edits to Mockingbird. But it mostly works as a sequel.

Forget what you’ve read and/or assume about Go Set a Watchman. It is not a “first draft” of To Kill a Mockingbird. And while it may not narrowly meet the definition of sequel, it sure reads like one: a new story, set decades later, with most of the same characters. Indeed, it really feels like the writer of this book assumes readers are familiar with the events and characters of To Kill a Mockingbird. Yes, there are inconsistencies, huge ones, which indicate it was not written after final edits to Mockingbird. But it mostly works as a sequel.

Also, Go Set a Watchman is not remotely, as NPR suggested (and many people suspected), “a mess.” It pleasurable reading, with Lee’s talent for dry humor and poetic description, and her unmatched ability to write perspicaciously about her own terrain. There are some uneven transitions, overlong conversations that could be trimmed (the mansplaining in this book!), and the aforementioned inconsistencies with Mockingbird, but it is not far from the polished sequel that might have been, if Lee had wanted to pursue it. I wonder how much of the decision not to publish this, as is, has more to do with anxiety over how the (white) reading public would receive it, than a judgment on its literary quality? And I wonder if Lee’s decision to abstain had more to do with roiling her community than feeling the manuscript was not up to snuff and beyond salvation?

Now to the touchy spot. The Atticus Finch in Go Set a Watchman is a continuation of the one we love from Mockingbird. It is not a different Atticus, or a different draft of Atticus. Sorry, folks. This is Atticus. Harper Lee goes out of her way to show us that the Atticus in Watchman is every inch the Atticus of Mockingbird. And, as you have probably read, in Watchman Atticus is a bigot.

Keep in mind that even the Mockingbird-era Atticus is a man of his time and place. His attitude toward black people is kind but paternalistic. He maintains his idealism in the courthouse, but the black people he has in his house are servants. He is a perfect example of the white moderate of good will, the kind Martin Luther King described as “the biggest stumbling block” to equality. This new Atticus does fit with that one; he may not fit with the one in your head but he fits with the one in the book.

Early reviewers dropped a “Snape kills Dumbledore” sized spoiler on the reading public, but the reviewers didn’t tell you this: it is supposed to be shocking. It is absolutely devastating to Jean Louise (aka Scout) when she finds out what her father has become. If we feel the soil give way beneath our feet, it’s because that’s exactly what Lee intended to do to us. I’m sorry you had to find out that way. I’m sorry I had to find out that way.

But it’s important for us to accept that this is our beloved Atticus Finch, and not some Bizarro world Atticus Finch, because racism is not just enacted by the uneducated, trashy Ewells of the world. It is also enacted by genteel and well-educated whites, even ones with lofty principles. Jean Louise discovers her father at his racist meeting among “men of substance and character, responsible men, good men. Men of all varieties and reputations.” She hides and listens to the filth spew from their mouths. None spews from her father’s mouth, at this meeting, but he doesn’t speak up. She thinks: “Did that make it less filthy? No, it condoned.”

This is a necessary message, and a necessary postscript to To Kill a Mockingbird. Racism is enacted by kind, polite people. Silence is sanction. If this is not the same Atticus, and if this is not a sequel, there is utterly no point to the book. The book is about Scout, now grown, coming to terms with the frailties of her own origins. Everywhere she goes, all of the people she meets, the people she loves, veer into racist diatribes. Is she of these people, she asks herself? Are these the people she loves? When she describes herself as color blind, it is not to hint that she doesn’t “see color,” in that late 20th Century trope, but that she has been blind to the true nature of her community. To be honest, even Jean Louise’s own New York-influenced high mindedness falls short of 2015 standards (but she’s getting there, her own ideas evolving even in the text.)

This book is a time capsule; perhaps its most glaring deficit in that regard is that Lee could not know how iconic Atticus and Scout would be decades later, how much we would want Atticus to remain a pillar of progressive ethics. Lee writes about him as if he were a mere human character. Perhaps the idealized Atticus Finch is another southern flag that needs to be lowered.

I won’t belabor this point, but I want to set the record straight on the book itself. Go Set a Watchman is not a mess, nor is it a sloppy draft. Read as a sequel to To Kill a Mockingbird, it has powerful and necessary truths, even ones that make us uncomfortable. It deepens and complicates our understanding of To Kill a Mockingbird, and though it is imperfect, it is no stain on Lee’s legacy.

Filed under: Miscellaneous Tagged: atticus finch, go set a watchman, harper lee

July 12, 2015

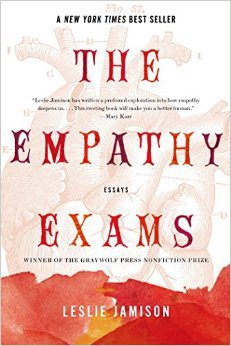

The Empathy Exams

The Empathy Exams is an essay collection by Leslie Jamison. The title comes from the first essay, where she blurs her experience as a medical actor with her own real-life medical experiences. Other essays approach second-hand experience of pain from different angles: reality television (of the sort that focuses on shattered lives); tours through impoverished and violent neighborhoods in the U.S., Mexico, and elsewhere; grueling ultramarathons; medical delusions; imprisonment; addiction. Other pain is personal: an abortion, a break-up, an inexplicable attack in a street in Nicaragua. In some ways Jamison is within a trend of creative nonfiction that packages pain for pleasure, like memoirs of addiction and abuse or depictions of third-world poverty. I’ve heard the genre dismissively referred to as “mis lit.”

The Empathy Exams is an essay collection by Leslie Jamison. The title comes from the first essay, where she blurs her experience as a medical actor with her own real-life medical experiences. Other essays approach second-hand experience of pain from different angles: reality television (of the sort that focuses on shattered lives); tours through impoverished and violent neighborhoods in the U.S., Mexico, and elsewhere; grueling ultramarathons; medical delusions; imprisonment; addiction. Other pain is personal: an abortion, a break-up, an inexplicable attack in a street in Nicaragua. In some ways Jamison is within a trend of creative nonfiction that packages pain for pleasure, like memoirs of addiction and abuse or depictions of third-world poverty. I’ve heard the genre dismissively referred to as “mis lit.”

But Jamison is doing something else in these essays: she isn’t writing about misery so much as the communal experience of misery, the choice to feel what others must feel. There is a place between lurid entertainment and antipathy. She isn’t sure where it is, but it’s where she wants to be.

“What can a twenty-something writer tell grown-ups about empathy?” one friend asked on Facebook, after I joked that it was “irritating” for such a young author to be so successful (similar criticism, some of it less facetious, is all over goodreads). But now I think that youth and uncertainty give this book its vitality. Jamison isn’t sure of herself; yet she is idealistic and hopeful about the form of essay in itself. She doesn’t generally adopt that all-know authoritative “we” voice I complained about recently; she stays within herself. She is honest and thoughtful, yearning to have a deeper conversation about the role of creative nonfiction in reshaping the world, to “fill the lack or liquidate the misfortune.” (And for the record, she is at least thirty).

Jamison is interested in empathy, but she isn’t sure about its value. Maybe empathy is solipsism, she suggests in the first essay, a kind of vicarious self-pity. How does empathy enable delusions, she wonders later, or the addicted, she considers yet later. Hers is not a call for people to “be more empathetic,” like that too-neat video with the bear and the rabbit. The title takes on new meaning as she continually scrutinizes empathy, coming to at least tentative conclusions. “It might be hard to hear anything over the clattering machinery of your own guilt,” she reflects in one essay. “Try to listen anyway.”

Midway through the book is an essay about sentimentality and sweeteners. I suspect it was the first one written: Jamison overeagerly drops in literary references, as if she’s eager to prove she’s read the canon; she resorts to that prescient “we”; and she writes in almost giddy abstraction about “crashing into wonder” and “flinging [oneself] upon simplicity.” Here she takes a stance for art (even bad art) that “can carry someone across the gulf between his life and the lives of others.” If I’m right about it being an earlier essay, it seems to give her the direction that makes the rest possible. She pursues and finds a purpose for tours of pain. She finds inspiration in the James Agee’s writings about rural poverty, and in documentaries that have freed innocent men by garnering public attention.

In the final epic essay Jamison considers the pain of women, often self-inflicted, bringing in the experiences of other women among her own: cutting, anorexia, miscellaneous wounds; mixed in with allusions to Sylvia Plath and Anne Carson, a brilliant one-page critique of Stephen King’s Carrie, lyrics from Ani DiFranco and Tori Amos, and too many other sources to list. She circles around women and pain, women writing about pain, the resentment and rejection of women writing about pain. She asserts explicitly what she is trying to do in the essay: to make it OK for women to write about pain, because even if it’s trite, the pain is real. “The wounded woman get’s called a stereotype, and sometimes she is. But sometimes she’s just true.” It feels like she’s finally enacted a proof of concept she’s been shaping the whole time. She’s found her exact place as an essayist. She’s found her way across the gulf an into the lives of others.

Filed under: Miscellaneous Tagged: empathy exams, leslie jamison

July 10, 2015

Abuses of the First Person Plural

I’ve resolved and failed to keep the promise to never write in the thinkpiece plural, the use of “we” that means either “most people, but certainly not me and other high-minded people,” or, conversely, “only people like me, as I kinda think there is nobody else.”

The first is generally used in social critiques, and conversations about conversations, of the sort:

“We call it _______ when _______ but when ______ we call it _______.”

This is married to the apophatic “nobody.”

“Nobody’s talking about ___________.”

If you’re like me you might find as many as a dozen posts in one Twitter stream talking about what purportedly nobody is talking about. It’s the non-set of the “we” that means “everybody else.”

I don’t understand this insistence on excusing oneself from the first person plural and from the human population. I am always a member of we, grammatically speaking. If I am doing something, then by definition somebody is doing it. But I’m sure I’ve lapsed into that think-piece language. I try to be aware of it and avoid it.

The other use of “we” is even more maddening, and I think I’m less likely to use it. This is the one where “we” is presumed to be everybody but is actually a quite small demographic of white, privileged people who probably have very good jobs and degrees from top tier schools. This is the “we” of magazine articles about helicopter parents and unrealized ambitions. It is the we of wanting yet more and feeling entitled to it — the woman who “sacrificed” a bigger family so she could buy a two million dollar home. Demographically I am sort of there — white, middle-aged, well-educated. But private preschools are not my concern; making do is. I am noncoastal. I am broke. My college degree is from a public university that doesn’t compete academically or athletically on a national stage.

I’m reminded, in these cases, of an overheard conversation between a knee-weakeningly gorgeous girl who sat behind me in chemistry class and said, to a friend, that “everybody” was at a particular party that weekend that obviously I was not at and knew nothing about.

I don’t write thinkpieces, but my mind is pretty much a 24/7 monotone of metacriticial noise. When I do venture to say a nonfictiony thing and make an observation, I try to keep out uses of “we” that doesn’t include me, or vaguely insinuates that everybody is in the same boat. The strongest writing I’ve seen is personal and openly autobiographical, it takes ownership of personal experience and presumes nothing about the reader. I think it makes you vulnerable, as a writer, to abandon the we, to stop blurring yourself into the background. It makes you take more ownership for your declarations, to be honest, to admit the limitations of your experience, perhaps even be embarrassed by your privilege.

Filed under: Miscellaneous

July 5, 2015

Mat Johnson’s Pym

Edgar Allan Poe is one of few authors by whom I’ve read everything, at least everything available, including his literary criticism. I was obsessed with him for a while, and in an alternative life where I get a Ph.D. in English Literature, I might well be writing academic papers on Poe (and Hawthorne, and Melville, and maybe Irving).

Edgar Allan Poe is one of few authors by whom I’ve read everything, at least everything available, including his literary criticism. I was obsessed with him for a while, and in an alternative life where I get a Ph.D. in English Literature, I might well be writing academic papers on Poe (and Hawthorne, and Melville, and maybe Irving).

The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym is easy to pick as Poe’s biggest failure. It is his only attempt at a novel, and falls short even there, with a series of loosely connected episodes that lack continuity and a proper ending. The problems don’t end there. It is also Poe’s most damningly racist work. Though racist caricatures appear in his other tales, this is the one most informed by Poe’s pathological fear of non-whiteness. However, it also proves to be one of his most influential works, figuring explicitly into subsequent works by some of his biggest admirers, particularly Jules Verne and H.P. Lovecraft.

The hero of Mat Johnson’s Pym is an African American scholar obsessed with Poe, and especially with Pym. This singular obsession with white authors (and a refusal to serve on the diversity committee) disrupts his academic career, but a series of coincidences leads him on his own fantastic voyage that parallel Poe’s Pym, encountering much of the same…. experiences.

It is simultaneously a pastiche and a critique of Poe, but an effective satire of current American culture: academia, pop painting, junk food, you name it. In some ways it is an academic novel, wise and winking in literary references, casually name-dropping major pieces of the black canon including ones that white readers like me didn’t know about (Equiano, Webb) mixed in with the more obvious ones to the source material (one nod to Lovecraft made me laugh out loud). But it would work without one knowing literary history, purely as adventure/horror and humor. And of course it is book about race itself; a critical reflection about whiteness and blackness both literal and figurative.

I love everything about this book. It centers me in the black experience of America as effectively as Ralph Ellison, and gives me a fix of sharp satire that reminds me of being fourteen and discovering Kurt Vonnegut. It pushes my buttons as literary nerd, but is enjoyable purely as a great yarn.

The American literary canon is racist and sexist because our history is racist and sexist, but what do we do about it? Pointing out the problems is necessary, but doesn’t suggest where to go next. I’m not a big fan of expunging literary history; that itself becomes a kind of whitewashing. Besides, I think there is value in Poe, in Twain, even in Margaret Mitchell. I would rather read those books, then read these creative critiques–books like Johnson’s Pym, or Alice Randall’s The Wind Be Gone–that critique and re-create and re-center the narratives, that subsume and overtake the source material.

I think Johnson takes on a particularly problematic text to show just how brilliantly this can be done; it makes me grateful for Poe’s Pym because it makes Johnson’s possible.

Filed under: Miscellaneous Tagged: mat johnson, poe, pym

July 3, 2015

Dung Beetles

For the last week I keep watching this video about a dung beetle trying to push a turd ball up a blazing hot sand dune. You think Sisyphus had a hard time of it? He has nothing on this uncomplaining scarab.

http://www.discovery.com/embed?page=68740

I’ve considered before the heroic efforts of the tiniest things, and more recently been particularly interested in these industrious recyclers. I am sure an idea is brewing but I don’t know what it is: nonfiction, perhaps, or a picture book, or a novel. “Watership Down with dung beetles!” I ventured yesterday on Facebook, to a rousing lack of enthusiasm.

I guess people think dung beetles are gross because dung, but… well, without them, things would be a lot grosser. They consume some feces and bury more, effectively aerating and fertilizing the land they use. I have come to appreciate nature more, in my middle-ages, and the wonderful integration of the world’s species to function as a whole. Imagine the prairie three hundred years ago: buffalo gobbling up the long hoary grass and leaving these tremendous buffets for the hordes of dung beetles that followed, who repurposed the poop and fed the small birds and prairie dogs, which in turn fed the ferrets and hawks and coyotes…. Without the beetles, none of it is possible. And dung beetles serve a similar role across the globe, in various ecosystems, and are rarely appreciated (though the ancient Egyptians wisely thought they were sacred).

Few people can claim what the dung beetle can, which is that their mere existence makes the world an unarguably better place. Dung beetles are also the only animal besides humans known to observe the stars, and I think this single idea is what makes them especially fascinating to me. The humblest creature on earth will climb upon its dung ball, orient itself by the milky way, and — I like to believe — make a fervent wish before it continues on its journey.

I think this will fuel a book but I don’t know what it is yet. I hope you will give it, and its heroes, a chance, despite their diet.

Filed under: Miscellaneous Tagged: dung beetles

June 27, 2015

The Saga of Big Bear

Every night we play Go Fish before Byron goes to bed. It is our favorite family ritual. Our deck has 26 matches, each match featuring a letter of the alphabet and an animal. The cleverest part is, one half of each match has the adult animal and capital letter; the other has the baby animal and the lowercase letter.*

The deck has been around since before B. was born and is no longer available. Anyway, sometimes Byron gets a little kooky bananas at the end of the game and scatters the cards. One evening we realized Big Bear was missing. We played for weeks with one of the instructions cards subbing for mama bear. We looked everywhere for that card, and sometimes when I had half an hour I would go looking for it again: through the drawers and cupboards and bookshelves and baskets in the living room, in different rooms in case somebody had absentmindedly carried it off. After a month we gave up. It became almost a joke to suggest we look for it some more.

The deck has been around since before B. was born and is no longer available. Anyway, sometimes Byron gets a little kooky bananas at the end of the game and scatters the cards. One evening we realized Big Bear was missing. We played for weeks with one of the instructions cards subbing for mama bear. We looked everywhere for that card, and sometimes when I had half an hour I would go looking for it again: through the drawers and cupboards and bookshelves and baskets in the living room, in different rooms in case somebody had absentmindedly carried it off. After a month we gave up. It became almost a joke to suggest we look for it some more.

The other night my wife was out, so B. and I played alone. He started asking me knowingly every time if I had a bear card. It turns out he and A. had found the missing card earlier that day and restored it to the deck, and he had it in his hand, and he couldn’t wait to make the match so I could see that they’d found it. And as crazy as it sounds it kinda feels like with the big bear back where she belongs, everything is going to be all right.

*In case you’re curious: Alligator, Bear, Cow, Duck, Elephant, Frog, Goat, Horse, Iguana, Koala, Iguana, Jaguar, Koala, Lion, Mouse, Narwhal, Orangutan, Pig, Quail, Rhinoceros, Squirrel, Turtle, Umbrella Bird, Vulture, Walrus, foX, Yak, Zebra

P.S. I was thinking of writing an entire post about the movie Inside Out, but I don’t think I have a blog entry’s worth to write about it, especially avoiding spoilers. I’ll just say that I’m heartened that an ordinary kid can drive a major summer movie: no superpowers, no wizard scars. The gimmick behind it is genius, and I think it’s a good conceit for the turbulence of childhood. This might be the most “middle grade” movie ever made. And I see it as radical that a major summer movie can be a movie about a girl’s feelings.

Byron is with me now and I read him this entire entry. He wants me to add that the movie has a scary clown it. You have been warned!

Filed under: Miscellaneous

June 24, 2015

The Noble Reading Project, and Other Failures

Remind me never to take on another project that isn’t writing a novel or raising a child or teaching a class — e.g., nothing that commits me well into the future when there is no compensation and no obligation. I ventured into my goal of reading exclusively women of color in 2015 with the best of intentions, and launched into it early but still did not make it a year, let alone all of 2015.

I have to admit some of the piss was taken out of me by a spate of articles about men who’d done what I was doing. I read a few books I didn’t care for, and felt ashamed for not liking them. My motivation started to flag. My mind started to wander. I’ve always been a mercurial reader.

So this spring I read some of the much buzzed YA books of the year — Bone Gap, The Walls Around Us, and Read Between the Lines are all terrific, by women at the top of their game. I meant to blog about them all but failed there, too (and have nothing to add to the chorus of acclaim for them all). In a way, that was a refreshing vacation from my own taste. I don’t actually like YA, or claim not to, but these books refute the facile claims that YA is especially “dark” or “morally certain.” I think the only thing YA really claims to be is about the teen experience.

More recently, I became hooked on the novels of Mat Johnson, who is, well, a dude. While everybody talks about race and talks about how we need to talk about race, I find Johnson does so more deftly and with more wit and verve than anyone else, at least that I’ve read.

I made excuses to myself because at least all of the books I were reading were either by women or a person of color, but I also recently read some essays by Edward O. Wilson, who is a white dude scientist who studies ants. As I noted back when I began my journey, the worst representation of women of color is in nonfiction, particularly when you move into the sciences (memoir, social justice, and history have better selections). If you want to read about science, and are limited to women authors from non-European backgrounds, the pickings are very slim. I did come to this book through an interest in Wilson specifically, anyway, but holy cow, are all the science books by white people, and most of them men.

I expect somebody will comment that it doesn’t matter because an ant is an ant, regardless of writing about it, but I think about young people — whipping smart ones, with an interest in the natural world — walking into that section and feeling that they’re in the “wrong” section. It makes me wonder, with the call for children’s books by diverse authors, where is the call for quality nonfiction across the curriculum that tells all children, this entire world is yours to study?

Anyway, back to my reading… it is time to concede that I have wandered off the path and will continue to do so. I have to read The Empathy Exams for a class I’m teaching, and have a towering to-be-read pile with all kinds of books by all kinds of people. Many of them are people of color, many are women, and many are both, but I am hereby removing all rules and strictures from myself.

However, I think it was a good practice while it lasted. I’ve come to be less likely to go straight to the white/male books, but actively seek out other points of view. I’m sure my reading habits have been permanently changed from it.

I have become more aware of ways that representation is still a problem — it is one thing to scan a bookshelf for proof that books by women or people of color exist, quite another to have only those options. And there other things I now know. Books by African American authors have long wait lists at the library, apparently in high demand by readers who can’t afford to go buy the book, but also suggesting the library isn’t meeting demand because they underpurchase those books in the first place. The audiobook section is particularly thin and picked over when you’re looking for books by women of color; I think aside from Toni Morrison and a few other luminaries, few get the honor of an audiobook production. Even acclaimed books with glowing reviews in all the major publications might be picked up by only a few bookstores; books that I’m sure would be in end-cap displays if they had the same buzz and white authors on the back. And, as previously mentioned, nonfiction is an utter desert.

I would not be aware of any of this if I hadn’t forced myself to look only for books that meet those two criteria. I would have probably gestured at a few bestsellers and award winners by women of color as counter-proof that everything is hunky dory. “Look, Roxane Gay is here, and Claudia Rankine is there, so there must not be a problem!”

I have also come to regard books by privileged people with more healthy skepticism. I can still enjoy a literary tour de force, but have less patience with the art-for-arts-sake self-indulgence that used to be my primary pleasure. It’s not that there are two genres of literature, exclusively staffed by white men on the one count and women of color on the other, but I kinda think that maybe white male writers suffer from a pathological self-regard that leads to stylistic navel-gazing and expertise-on-all-things. And that in Danticat and Adichie, especially, I found a vital currency and immediacy, books about experience of living instead of the experience of reading a book, that made me feel their books were important, not just as books, but as historical artifacts. I don’t feel that way reading David Mitchell, however dazzling his artistry.

Anyway, I’m letting myself off the hook, but feel generally less stupid for having tried.

Filed under: Miscellaneous Tagged: Reading

Kurtis Scaletta's Blog

- Kurtis Scaletta's profile

- 45 followers