Adrian Collins's Blog, page 96

May 20, 2023

REVIEW: The Lies of the Ajungo by Moses Ose Utomi

Set in an African-inspired world full of wonder and horror, Moses Ose Utomi’s novella The Lies of the Ajungo is a powerful, beguiling blend of parable and fantasy. As part of a bargain with the powerful Ajungo Empire, the citizens of the City of Lies sacrifice their tongues when they turn thirteen in exchange for just enough water to survive. When twelve-year-old Tutu realises just how ill his mother has become, he bravely sets out in search of water, determined to return to his city a hero. His journey through the Forever Desert is filled with danger, hope and heartbreak. Over the course of his travels he grows into a man, but also learns the true darkness behind the City of Lies and the realities of the Ajungo.

Dealing with some seriously grim themes–lies, manipulation, deep injustice and a terrible power imbalance, just for starters–The Lies of the Ajungo hides a considerable darkness beneath its surface, even if it’s maybe not quite what you’d call grimdark. Starting the story off as an almost total innocent, Tutu is trying to be a hero without really knowing what that means, a naive child lost in a world full of people so weighed down by pain and suffering that all they can do is concentrate on survival, whatever that takes. This isn’t a story about heroes though, and while parts of Tutu’s arc are beautiful and genuinely heartwarming, watching him come to understand just how much he’s been lied to–and what that does to him–is utterly heartbreaking.

Dealing with some seriously grim themes–lies, manipulation, deep injustice and a terrible power imbalance, just for starters–The Lies of the Ajungo hides a considerable darkness beneath its surface, even if it’s maybe not quite what you’d call grimdark. Starting the story off as an almost total innocent, Tutu is trying to be a hero without really knowing what that means, a naive child lost in a world full of people so weighed down by pain and suffering that all they can do is concentrate on survival, whatever that takes. This isn’t a story about heroes though, and while parts of Tutu’s arc are beautiful and genuinely heartwarming, watching him come to understand just how much he’s been lied to–and what that does to him–is utterly heartbreaking.

While this is very much a fantasy setting, complete with its own unique, intriguing forms of magic and a pretty bleak history, the fantastical elements never dominate or take away from the core of the story. The plot is largely quite straightforward, keeping the pace moving and lending proceedings a parable-like sense of focus and elegant simplicity. With the focus very much on Tutu’s emotional and intellectual journey, this determinedly character-first approach has a really powerful impact. The Lies of the Ajungo is a book which will undoubtedly reward multiple readings, with resonant themes and a brilliant protagonist, and which delivers an emotional punch far beyond what you might expect from its size. The fact that it’s only the first in a trilogy of novellas is really just the icing on the cake.

Read The Lies of the Ajungo by Moses Ose UtomiThe post REVIEW: The Lies of the Ajungo by Moses Ose Utomi appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

May 19, 2023

REVIEW: Cyberpunk 2077: Big City Dreams

I’m a big fan of the Cyberpunk 2077 comics by Dark Horse comics. I’ve been starved for cyberpunk content for the past decade and Cyberpunk 2077 only slightly scratched that itch. It’s a marriage made in heaven, or Night City at least, because Dark Horse is one of the few companies that I feel can really capture that dark and gritty attitude as well as the artwork style necessary to bring to life the dystopian futures that I love to read about. I haven’t been 100% blown away by the comics at times but I’ve never not gotten my money’s worth either.

The premise for Big City Dreams is that Tasha and Mirek are a pair of wannabe Edgerunners that are just a pair of hoodlums. Tasha fires her gun randomly at whoever catches her fancy and Mirek supports her despite the fact, well, he’s not psychotically violent. All this changes when Mirek finds himself trying out a brain dance (virtual reality for non-Cyberpunk 2077 fans) and experiences the life of a loving father as well as husband on a farm outside of Night City.

The premise for Big City Dreams is that Tasha and Mirek are a pair of wannabe Edgerunners that are just a pair of hoodlums. Tasha fires her gun randomly at whoever catches her fancy and Mirek supports her despite the fact, well, he’s not psychotically violent. All this changes when Mirek finds himself trying out a brain dance (virtual reality for non-Cyberpunk 2077 fans) and experiences the life of a loving father as well as husband on a farm outside of Night City.

The premise is a simple one, but I actually give props to the writers for coming up with something that I didn’t really expect to see in a comic like this. It’s a theme that resonates with the video game’s central one and its characters: do you want a quiet life or to die in the blaze of glory? This is a question asked repeatedly of V (the video game’s protagonist) and the ending of the game reflects whether he or she believes one or the other is their destiny.

I’m not sure Tasha is smart enough to realize she’s going to die or that anyone else matters enough to make the choice but it’s clear what she’d choose. She believes she’s a burgeoning Night City legend who will kill her way to the top despite the fact she’s manifestly incompetent as well as a murder hobo. Mirek, by contrast, is stunned at the possibility of a quiet life even existing. He wants to experience the life of a quiet farmer and family man away from violence as well as death. However, the moment he shares his “vision” with Tasha, he’s resoundingly mocked.

I like this story more than I thought I would because it strikes me as the kind of tale that the vast majority of the mooks encountered in the video game (and tabletop RPG for that matter) would have. Tasha doesn’t have the education, temperament, or skills to reach her goals, but she’s got a sociopathic unearned pride that tells her killing random chooms on the street will somehow make her famous. Mirek doesn’t have any other friends or loved ones (I’m not sure if Tasha is his girlfriend or not), so he’s just willing to go along with it.

I also like that while Mirek romanticizes the life of the countryside, the book doesn’t shy away from the fact it’s every bit the kind of illusion that Night City sells to wannabes like Tasha. Our first encounter with the farmer in “reality” is that his wife is miserable living on the farm and the quiet life does not suit her in the slightest. She wants to live in Night City and maybe she would be happy there or maybe it’s just a case of there being nowhere truly “happy” in Mike Pondsmith’s Earth.

Read Cyberpunk 2077: Big City DreamsThe post REVIEW: Cyberpunk 2077: Big City Dreams appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

May 18, 2023

REVIEW: The Malevolent Seven by Sebastien de Castell

The Malevolent Seven by Sebastien de Castell is a dark, comedic and bleak fantasy that paints a vivid and miserable picture of a world beset by warring angels and demons. This is as dark as it gets, with grisly deaths and despicable acts littering the pages. The aforementioned angels and demons cannot physically exist in the mortal plane, meaning their wishes are carried out by representatives. This struggle is the main thrust of our plot, which is breakneck and filled with twists and turns.

It has to be said, I don’t think I’ve read a book recently that embodies grimdark as strongly as The Malevolent Seven. Some of the deaths are truly jaw-dropping in their creativity and De Castell plunges some of our characters into depths of suffering so low that your heart can’t help but cry out for them. For readers of De Castell’s famous Greatcoats series (starting with Traitor’s Blade), his ability to make his characters suffer will not surprise you. But in the Malevolent Seven he takes this suffering to new levels, all while our main characters crack joke after joke.

It has to be said, I don’t think I’ve read a book recently that embodies grimdark as strongly as The Malevolent Seven. Some of the deaths are truly jaw-dropping in their creativity and De Castell plunges some of our characters into depths of suffering so low that your heart can’t help but cry out for them. For readers of De Castell’s famous Greatcoats series (starting with Traitor’s Blade), his ability to make his characters suffer will not surprise you. But in the Malevolent Seven he takes this suffering to new levels, all while our main characters crack joke after joke.

Speaking of the Greatcoats series, in those books our main characters are fallen magistrates bound to ideals of honour and duty, concepts they fully embody. This time round, our protagonists are about as far from that as you can get. They are the bad guys and they wander the world taking jobs from dictators and autocrats who pay them to use their devastating magical abilities to fulfil some pretty evil ambitions.

Money, war and sex. These are the concepts that the wonderists in The Malevolent Seven are bound by and Cade Ombra, the narrator of this tale, isn’t much better. He leaves us in no doubt about his thoughts on honour and valour and readily accepts being a villain rather than a hero. The Malevolent Seven follows Cade and his friend Corrigan, a homicidal thunder mage, as they carry out a suicide mission to kill the seven deadliest mages on the continent. Cade is in the business of selling himself to the highest bidder but he knows that there is more than meets the eye with this mission and a big chunk of The Malevolent Seven is him trying to work out what exactly he and his crew are getting themselves into.

It’s important to mention his crew as he and Corrigan spend a lot of time fulfilling ‘side quests’ to recruit the five other members of The Malevolent Seven. Without going into too much detail, we see a lot of hi-jinx and a lot of things go wrong as the crew belatedly come together. There is death–so much death–and we see some pretty cool elements of the world de Castell has built, including pleasure barges, rat mages and his take on the underworld. Their mission inevitably takes a turn and we end up with a pretty epic conclusion, one that promises a very exciting next installment in this series.

However, I think that’s where my issue lies. The events of the ending rendered much of what happened in the Malevolent Seven obsolete and I can’t help but thinking we could have got there a lot faster. This is effectively an origin story for the crew and though De Castell does a good job, it’s inevitable that the journeys of some of the seven characters feel a bit forced and poorly paced. A lot of the moments aren’t given enough time to breathe and we seem to jump from scene to scene at a breakneck speed. It feels at times as if de Castell tried to simply fit too much into this relatively short novel.

Plugging the gaps in worldbuilding is Cade and his narrative where he tells us in great detail about various magical concepts and explains the politics and structure of the world. I didn’t love this. Cade was undoubtedly entertaining at times but the constant breaking of the fourth wall definitely took away from the stakes and I struggled to get properly immersed in the book. There were a few occasions where concepts were just explained to the reader in the form of Cade’s slightly condescending, ‘too smart for you’ tone. This kind of narrative can undoubtedly work–some of my favourite books have proven that. However, I think we had a bit too much info-dumping throughout.

Overall, however, De Castell is one of my favourite authors and this is a pretty solid start to a series that has a lot of potential. The ending left me genuinely excited for what’s to come and the breadth of de Castell’s imagination is truly incredible. The Malevolent Seven is definitely one that grimdark fans will not want to miss. It’s been a while since I’ve read a book so unapologetically gory and over-the-top with its killing.

Read The Malevolent Seven by Sebastien de CastellThe post REVIEW: The Malevolent Seven by Sebastien de Castell appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

May 17, 2023

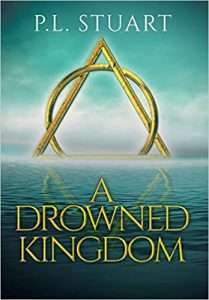

REVIEW: A Drowned Kingdom by P.L. Stuart

Submerge yourself in the majesty of P.L. Stuart’s masterful debut novel, A Drowned Kingdom, a fantasy inspired by the mythology of Atlantis. A Drowned Kingdom asks the question: when the most powerful country in the world is swallowed by the sea, can a new kingdom rise again?

The novel opens with a colonialist mission conducted by the First and Second Princes of the island kingdom of Atalanyx. While their objective is obviously political, they use religion to justify their actions, having the goal of converting pagans from their polytheistic religion to the one true God of Atalanyx. The monotheistic Atalantean religion is represented by the sign of the triangle and the circle, as depicted on the minimalistic cover of the novel.

The novel opens with a colonialist mission conducted by the First and Second Princes of the island kingdom of Atalanyx. While their objective is obviously political, they use religion to justify their actions, having the goal of converting pagans from their polytheistic religion to the one true God of Atalanyx. The monotheistic Atalantean religion is represented by the sign of the triangle and the circle, as depicted on the minimalistic cover of the novel.

A Drowned Kingdom is told as a first-person narrative by Othrun, the Second Prince of Atalantyx and half-brother of First Prince Erthal, heir to the kingdom. P.L. Stuart’s decision to employ single-perspective first-person narration works very effectively, although it is often discomforting being stuck inside the head of a despicable character such as Othrun. It doesn’t take long for Othrun to reveal his racism, misogyny, and religious intolerance.

Being inside Othrun’s head creates a morality distortion field on par with some of the greatest grimdark protagonists. But P.L. Stuart’s approach is also unique with the deeply religious influences on Othrun’s reasoning. Othrun’s belief in the Atalantean religion with its one true God seems genuine, but there are moments when his religious fervor may cross over into delirium. Othrun’s faith-based explanations for major events in the novel push him further into zealotry. P.L. Stuart has done a marvelous job plumbing the depths of Othrun’s psychology as he justifies treachery and sets himself on a path toward possible tyranny.

A Drowned Kingdom is also heavy on politics, and P.L. Stuart is adept at capturing the nuances of political interactions and the subtle games that people play to give themselves an advantage.

Although this is his debut novel, P.L. Stuart writes like a well-seasoned veteran. His prose has a gravitas that feels Biblical in some parts and like a historical diary in others. Despite its formality, Stuart’s prose is remarkably accessible, captivating me from the first page. The story itself is a slow burn but methodically paced.

P.L. Stuart is a master of characterization. The worldbuilding in A Drowned Kingdom is exceptionally well done. Yet this is just the tip of the iceberg, as our view is limited by Othrun’s unreliable tunnel vision.

Overall, A Drowned Kingdom is a remarkable debut that will appeal equally to grimdark and classic epic fantasy fans. The saga continues with The Last of the Atalanteans, the next installment in P.L. Stuart’s planned seven-book series, The Drowned Kingdom.

4.5/5

Read A Drowned Kingdom by P.L. StuartThe post REVIEW: A Drowned Kingdom by P.L. Stuart appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

May 16, 2023

REVIEW: Sister, Maiden, Monster by Lucy A. Snyder

Visceral, gory, and deliciously unhinged, Sister, Maiden, Monster is a fast-paced, disturbingly relatable pandemic horror that I absolutely devoured and never wanted to end.

Centering around the deadly—and thankfully fictional—PVG virus (polymorphic viral gastroencephalitis), Sister, Maiden, Monster is structured as three vignettes, each concerning a woman with a pivotal part to play in the ongoing apocalypse. Though there is little to connect Erin, Savannah and Mareva in their day to day lives, they’re all infected with PVG. It’s not long before their symptoms start manifesting in vastly different, horrifying ways.

Centering around the deadly—and thankfully fictional—PVG virus (polymorphic viral gastroencephalitis), Sister, Maiden, Monster is structured as three vignettes, each concerning a woman with a pivotal part to play in the ongoing apocalypse. Though there is little to connect Erin, Savannah and Mareva in their day to day lives, they’re all infected with PVG. It’s not long before their symptoms start manifesting in vastly different, horrifying ways.

Lucy A. Snyder writes in a highly evocative and effervescent style that makes the pages of Sister, Maiden, Monster turn very easily. Her descriptions are both matter of fact and grotesque, drawing on deep-seated human fears to crawl under your skin and linger in a way that is both repulsive and moreish. There’s an awful lot of teeth, hair and fleshy appendages growing where they shouldn’t, which is good news if you’re a fan of body horror; Snyder more than has you covered.

The body horror serves a purpose, however. The inadequate treatment of the chronically ill—especially women—is a prevalent theme throughout this book, as is feminism, the loss of body autonomy, and the erosion of human rights during times of great crisis. I particularly related to Erin’s struggle to adjust to her new life post-PVG infection. In seeking out alternative treatments with her fellow sufferers, rather than accepting the hopelessly grim fate dictated to her, she becomes empowered; transformed.

The two other POV characters, sex worker Savannah and teratoma-suffering Mareva, are both equally well drawn. Some of the actions these women commit are utterly reprehensible. And yet… I cannot bring myself to begrudge them for any of it, let alone dislike them. There’s a wit and verve to Snyder’s prose that makes even the goriest and most violent occurrences seem outright funny in places. I also love how unabashedly queer all these women are, and the way in which Snyder incorporates our real-life global reaction to COVID-19.

Where Sister, Maiden, Monster slightly lost me, however, was towards the end where things started getting—for want of a better word—silly. Horror is at its best when operating somewhere between reality and unreality; in that liminal space where readers know enough to draw conclusions, but not enough to know for sure. Unlike its predecessors, Part Three is largely set after the world has been utterly transformed by PVG, and it’s at this point some of the gross-out body horror moments start feeling tacky and cheap.

Snyder also introduces elements from Robert W. Chambers’ book, The King in Yellow, such as descriptions of the lost city of Carcosa, the Yellow Sign, and the Stranger in the Pallid Mask. Side by side with all the eldritch cosmic tentacle monsters, this seems to place Sister, Maiden, Monster firmly within Lovecraft’s Cthulu Mythos. This changed the tone and context of the book for me personally and left me feeling a bit confused. As much as I love Lovecraftian horror, I’m not overly familiar with anything outside of what the man himself wrote. I had to Google the Yellow Sign to try and make sense of the ending, and I’m still none the wiser really.

Overall, I had a great time reading Sister, Maiden, Monster. I was never bored, often shocked, it made my skin crawl, and I laughed more than once. I thought it was excellent.

Read Sister, Maiden, Monster by Lucy A. SnyderThe post REVIEW: Sister, Maiden, Monster by Lucy A. Snyder appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

An Interview with Mark Lawrence (2023)

Mark Lawrence has been a key voice in grimdark fantasy since the release of Prince of Thorns in 2011. Lawrence engages heavily with the grimdark community as both an author and as founder of the Self-Published Fantasy Blog-Off (SPFBO), using his platform to help indie authors. He has published sixteen novels that blend fantasy and science fiction to create an intricately connected universe spanning three worlds.

Mark Lawrence’s latest novel is The Book that Wouldn’t Burn, the first installment in The Library Trilogy. I recently had the distinct pleasure of speaking with Mark about his latest novel.

[GdM] Thanks so much for taking the time to do this interview with Grimdark Magazine. The Book that Wouldn’t Burn is your self-described love letter to books and the buildings where they live. Your descriptions of the Athenaeum—the infinitely large library of The Book that Wouldn’t Burn—made me feel like a young child, staring in awe at the tall bookshelves and the unopened books waiting to be read. When did you first fall in love with libraries? Did you find yourself reliving childhood memories as you were writing The Book that Wouldn’t Burn?

[ML] My mother’s first job when she and my father returned to the UK with baby Mark from a few years stint in America was as a librarian. So, I have very early memories of being a toddler in her workplace, dwarfed by towering bookshelves, lost in the midst of it. I certainly tried to get that feeling on the page. Books always numbered among my Christmas presents as a child, before video games etc were a thing, and I saw them as special, treasured items.

[ML] My mother’s first job when she and my father returned to the UK with baby Mark from a few years stint in America was as a librarian. So, I have very early memories of being a toddler in her workplace, dwarfed by towering bookshelves, lost in the midst of it. I certainly tried to get that feeling on the page. Books always numbered among my Christmas presents as a child, before video games etc were a thing, and I saw them as special, treasured items.

I found the library in question – my mother worked there in 1969. It’s a lot smaller than I remember!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hammersmith_Library

[GdM] Your previous trilogies are each built around a single main protagonist (Jorg, Jalan, Nona, Nick, and Yaz), but The Book that Wouldn’t Burn takes a different approach with two dynamic leads, Livira Page and Evar Eventari. How did you first develop the concept for The Book that Wouldn’t Burn? Was it a different process compared to your previous trilogies, which are built more overtly around a single protagonist?

[ML] Heh, I’m not sure phrases like “develop the concept” have a place in my writing. I don’t generally plan my books and for this one the ideas I had before I started typing would have fitted into a fairly short paragraph. The stories take form as I follow them across the pages.

I knew I wanted to show two sides to the library, one from the outside, seeing it as alien, unexpected, and wondrous. One from the inside, overly familiar, and seeing it as a place to be escaped. A theme that runs through the book is that of presenting ideas and situations from different angles and showing how the ‘truth’ of them is so dependent on context. And to do things like that, it helps to have more than one point of view character. You might carry that further and say, why not nine point of view characters? But I like to bring my point of view characters to life, to really get under their skin and form emotional bonds with them. This is easier with one or two characters who get lots of page time each.

[GdM] All of your trilogies play with the notion of time, sometimes subtly but often in a quite explicit fashion. The Book that Wouldn’t Burn falls into the latter category, with time flowing very differently between the library and the outside world. How did you decide to pursue a narrative where characters age at different rates? Did it present any special challenges or open unexpected avenues for the plot progression?

[ML] This is certainly walking the spoiler line, but what isn’t a spoiler is that I have great difficulty with ‘how did you decide’ type questions. Such questions imply a degree of internal debate that’s orders of magnitude greater than the reality. I often say, I just sit down and type. This isn’t meant to be dismissive or to hide any secret formula – it’s just what I do. Possibly the writing equivalent of the shoulder angel and shoulder devil are having heated debates about these issues in my subconscious, but all my consciousness does it ask, “What next?” then type it out.

Any significant transition in time, especially with a young character, presents challenges in accounting for the years missing from the page, and in easing the reader over the discontinuity. Additionally, there’s a need to have the character grow on all levels, physically, emotionally, and intellectually. I did the same thing with Jorg in The Broken Empire trilogy, and Nona in The Book of the Ancestor trilogy. So, I’ve had some practice.

[GdM] One of many reasons why I find your books so engaging is that there is always a scientific or technological basis for the fantastical elements of the stories, which makes them more believable. You have leveraged relativity, quantum mechanics, genetic mutations, artificial intelligence, and much more. Do you think that having a plausible scientific basis for fantasy is important so readers are not asked to suspend their disbelief around a new world and its magic system?

[ML] I think fantasy readers are old hands at suspending disbelief, so I don’t feel there’s a need for some pseudoscience arm waving in that regard. It’s just something I enjoy. I haven’t wanted to write a portal fantasy, but I do like connections between my fantasy worlds and the reality we inhabit. It serves to give it a sense of scale somehow. And the science elements serve as a kind of bridge, an indicator of a shared history, albeit a distant one.

[GdM] At the end of your previous novel, The Girl and the Moon, you wrote that it’s time for something new. The Book that Wouldn’t Burn is a wholly original tale set in a new world with a brand-new cast of characters. Yet with its infinitely large library, The Book that Wouldn’t Burn somehow encompasses all your previous work. How would you like people to view your interconnected universe? Do you have a preferred name for it?

[GdM] At the end of your previous novel, The Girl and the Moon, you wrote that it’s time for something new. The Book that Wouldn’t Burn is a wholly original tale set in a new world with a brand-new cast of characters. Yet with its infinitely large library, The Book that Wouldn’t Burn somehow encompasses all your previous work. How would you like people to view your interconnected universe? Do you have a preferred name for it?

[ML] I think it’s more the case that the library encompasses all realities, so setting copyright issues aside, it encompasses everyone’s previous (and future) work, along with anything they might possibly have written but didn’t. There’s no connection between this trilogy and my other work. The epigraphs heading various chapters include some playful nods, but they also include references to pop culture and literature from Shakespeare to 20th century poets, along with a host of entirely fictional works of fiction.

[GdM] The Book that Wouldn’t Burn is your longest novel to date. As a hefty book set in a library, I was expecting this to be a slow-paced story. I was pleasantly surprised to discover that The Book that Wouldn’t Burn is your fastest paced novel since Prince of Thorns. How do you approach the pacing of a novel? Does it unfold naturally for you, or does it require deliberate decision?

[ML] I’ve come to the conclusion that pacing is mainly in the eye of the beholder. The less someone is enjoying a book, the more likely they are to call it slow paced. Whenever a story veers away from the aspects a particular reader is interested in then that reader is likely to call those sections slow. The phrase often functions in readers’ minds as a stand in for the speed with which enjoyment is being delivered to them. And since different readers enjoy different things this explains why two readers can read the same book and one will call it slow paced and the other will say it was fast paced. I’ve certainly seen diametrically opposed judgements on aspects of a book (like pacing) which are nominally objective properties rather than subjective ones.

I tend to think of all of my books as relatively fast paced, and perhaps The Girl And The Stars is the most breakneck of them all.

As to how I approach the pacing of a novel, I’ll have to fall back into the pattern of previous answers and say that it never enters my mind at all. I just write a story that entertains me. However, since this turned out to be my most heavily edited book ever (it wasn’t heavily edited, but since I normally do very little at all, this holds the crown) I can say more on this question. My editor, whilst loving the book, did say that the middle section of the manuscript I handed in was “a little soggy” – which is a reference to pace. She felt it was getting a bit slow/bogged down. And in response I did chop out several small chunks, and also condense two chapters into one, losing a bunch more text. All of which is highly unusual for me. That chapter chopping was the first time. I’ve not done that in the previous 16 books.

So yes, someone had a clinical eye on pacing and edits were made to rectify that ‘sogginess’!

[GdM] Fantasy has a reputation for being overly wordy, but you never seem to waste a single word in any of your novels. Despite its length, The Book that Wouldn’t Burn is no exception. As scientists, we are taught that writing should be both precise and concise. Has your training as a scientist influenced how you write fiction? Do you find that it gives you a different perspective on writing compared to other authors coming from non-scientific backgrounds?

[ML] It’s certainly true that some fantasy is very wordy, especially the stuff written in the 80s. There was definitely a Big Fat Fantasy market, and if you’re writing a BFF then one way to push the front cover further away from the back is to be wordy.

I’ve enjoyed a fair few BFFs myself, back in the day, though I’d lost my taste for them by the time that things like Wheel of Time hoved into view. It’s never been in my nature to write great reams of description. I subscribe to the idea that the reader’s imagination will do a lot of the heavy lifting if you strike the right note, and that whole settings can be summoned into being with relatively few words if – and here’s the hard part – if they are the correct words.

I don’t think any of this is a scientist vs non-scientist thing though, just a matter of taste. And it’s not a black and white issue by any means. Just because I would try to evoke the feeling of being in a country lane with talk of the smell, and the wind, and the wideness of the sky – there’s very definitely a place for the author who populates the hedgerow with half a dozen named species and waxes lyrical about the interplay of colour and light.

[GdM] The Book that Wouldn’t Burn is your most theme-driven novel to date, covering topics such as how society develops the idea of a collective enemy, the seductive power of lies, and the danger of information in the absence of wisdom. With the global rise of nationalism and the weaponization of disinformation, these topics are more important now than ever. Did you feel that it was your responsibility as a writer (or as a Nobel Peace Prize nominee) to include these themes in The Book that Wouldn’t Burn? How should society respond in an age where disinformation spreads globally with the press of a button?

[ML] I certainly didn’t feel it was my responsibility. I wouldn’t ever want to write a responsible book! But these are things that I see in the world around me, and it seems natural to want to hold them up to the light and inspect them from different angles.

The Book That Wouldn’t Burn, like many of my other books, asks questions. It doesn’t give answers to those questions – that would be lecturing and I’m not in the business of educating readers, just in giving them something to think about.

There are two extreme views at the heart of the trilogy, and they attract various of the characters whilst others reject the emotional purity of the far ends of the spectrum and wallow in the messy realm of compromise. And none of these positions are, I hope, portrayed as without merit.

These are big issues with no answers that are obviously correct. I don’t try to solve them. But I do use the characters and their unfolding lives to explore the subject.

That sounds a bit dry and highbrow – but this is just a background – the story itself is about people and filled with action, adventure, even some kissing!

[GdM] The Book that Wouldn’t Burn contains some of the most beautifully written epigraphs of any book I’ve read. The epigraphs also provide plenty of Easter eggs for longtime fans of your work. What is your process for writing epigraphs? Do ideas for epigraphs arise while you are writing the corpus of the book, or do you tend to write them afterwards?

[ML] Once again I’ll have to say there’s not much of a process, but I can tell you that the idea of having epigraphs was suggested by Natasha Bardon (who heads up Voyager) after she’d read the manuscript. I thought it was a good idea and sat down to write 70 of the things. It took me about 3 days. I would look at the first page of each chapter, remember roughly what happened in it, and try to write something that held some vague connection with the events on a thematic level. Those connections vary from tenuous to non-existent.

The epigraphs are largely supposed extracts from books that live within the library, and they variously contain literary or pop culture references, often disguised. Some are just sentiments that occurred to me in the moment. Mostly they’re just a bit of fun, but quite a few of them turned out rather well, I feel.

I’ve done epigraphs for the other two books of the trilogy, and it was the same deal with those – I wrote them all together after the books were finished.

[GdM] From King of Thorns through The Book that Wouldn’t Burn, another one of your recurring themes is the nature of memory. How have your perspectives on memory evolved over your career as a scientist and later as an author? Have recent developments in artificial intelligence changed your perspective on the nature of memory and sentience?

[ML] I’ve always had an armchair interest in the nature of intelligence – both in the sense of how it might be recreated in different (silicon) forms, but also in the psychological and neuroscience sense: how do we create the illusion/delusion in which we exist. Our lives are great works of fiction loosely coupled to an underlying reality through our senses, biases, and – importantly – our memories. AI has always been both a fascinating prospect in its own right, but also another way to interrogate our awareness of self.

I don’t think recent developments have changed my perspective so much as sharpened my appetite for more advances and understanding. It turns out that there’s nothing more mind blowing than the mind.

[GdM] Is there anything you can share about the next two volumes of The Library Trilogy or other future projects currently underway?

[ML] There’s not a lot I want to say about them. They’re both written, and it will be book 1 that sells readers on book 2 rather than anything I have to say about it. But I’m definitely happy with how the story develops and also how it ends. Which is nice, because I never know how my books are going to end or even if a satisfying ending is possible – which is a bit terrifying when it comes to contracted work, a terror that I ameliorate by being so far ahead of schedule that should everything crash and burn, I could just start again. But I’ve never had to.

Read our 2022 Interview with Mark Lawrence here

Read our 2014 Interview with Mark Lawrence here

Read The Book That Wouldn’t Burn by Mark Lawrence

The post An Interview with Mark Lawrence (2023) appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

May 15, 2023

An Interview With Alexander Darwin

Alexander Darwin has had quite the journey to get to this point. In the last few years, he has gone from competing in beloved Self-Published Fantasy Blog Off (SPFBO), a cut-throat fantasy competition put on by novelist Mark Lawrence, to dropping his debut with Orbit books. Alexander is also a jiu-jitsu instructor who knows the five-finger exploding heart palm technique, probably. He was kind enough to have a lovely conversation with me about his upcoming novel The Combat Codes, writing, martial arts, and having his foot in two publishing worlds.

[GdM] I read in an interview that you grew up loving Dragonlance and played AD&D. Do you still play? Do you find that your early experience translated into your writing?

[GdM] I read in an interview that you grew up loving Dragonlance and played AD&D. Do you still play? Do you find that your early experience translated into your writing?

I don’t play anymore sadly! I played a ton between the ages of ten and twenty, and then stopped because I didn’t have anyone to play with. Since then, D&D seems to have gotten so popular and I’m really itching to get back into it. I have three daughters who I fully plan on indoctrinating when they are the right age!

I feel like D&D and role playing in general are such great vehicles for creativity. It sent me on the path at an early age, writing Dragonlance and Drizzt fan fiction.

[GdM] I saw someone refer to you as the most dangerous man in fantasy; what do you think about that? And do you know the five-point palm exploding heart technique from Kill Bill?

[AD] HAHAHA! I have a feeling John Gwynne and Miles Cameron might have something to say about that, especially if armor and weaponry are fair game. If we’re talking pajama wrestling (gi jiu-jitsu), I might have a shot, though there are several other practitioners you might not know of including Fonda Lee and Evan Winter.

And yes, I do know the five-point palm exploding heart technique, in particular because I’ve watched the final scene in Kill Bill 2 probably a hundred times. It’s one of my scenes in film. Just so friggin’ awesome –she hits Bill and then asks if she’s a bad person and he responds “naw… you’re a terrific person.” Then he gets up, buttons his jacket, and walks away as the music swells before dropping dead. So good.

[GdM] You wrote an excellent article on Jiu-Jitsu called, “Jiu Jitsu is Play.” Can you explain your mindset as a practitioner of Jiu-Jitsu? Is it always play for you?

[AD] I truly believe Brazilian jiu jitsu is one of the most unique activities a human can participate in because it taps into our mammalian brain’s need to play. If you watch mammals – rats, cats, dogs, bears, primates – they play fight, and it’s almost always grappling to prevent serious injury and so that they can prepare themselves for a competitive world. But studies have also shown this sort of play fighting can decrease stress – which it certainly does in my case.

I think when you are playing (at anything) your brain naturally becomes more sponge-like and can better soak up information. My students who learn how to play well often exceed those who are “trying too hard,” because they can test new skills and apply them without a self-imposed pressure of success.

Competition is another game though. The sort of training done for that isn’t as playful, which is one reason I never enjoyed competing much (even though I forced myself to do so). When you are competing you stop learning and just focus on your “A-Game,” which is really not much fun. I think this is why many competitors burn out. I’m in it for the long haul.

[GdM] You have a new book coming out, The Combat Codes. Can you talk about your journey to get to this point?

[AD] Wow, it’s been quite a crazy journey.

The book was self-published, and it did pretty well, in particular because in 2020 it became a finalist in SPFBO. This contest is a fantastic launch pad for self-pub authors; it’s run by Mark Lawrence with a wonderful assortment of reviewers / judges.

Through the next year I wrote and published the next two installments in the trilogy, and right after I released Blacklight Born (the third book) the entire series was acquired by Orbit Books. I can’t tell you how happy this made me, given they are by far my favorite SFF publisher, and I’m a massive fan of so many of their authors, like Evan Winter and Fonda Lee.

It was a unique opportunity for me because not only was I able to capitalize on Orbit’s editorial team to bring the Combat Codes to the next level, but I also took years of feedback from readers and reviewers to apply to the updated version. We did a ton of extra worldbuilding and character development this time around – almost an additional 30K words – and I’ve better aligned the first book on a trajectory for a very satisfying series arc.

[GdM] What is The Combat Codes about?

[AD] The book takes place in a world where single, unarmed combat between champions called Grievar Knights has replaced large scale wars. It follows two primary POVs:

Murray is an aging Knight who used to be at the top of the world and is now scrounging for scraps as a talent scout. He’s grappling not only with a failing body, but also the notion that the Codes of honor he’d lived by have eroded. Cego is a boy looking for his place in the world, but he’s stuck down in the slave Circles, fighting for drunks and degenerates. He certainly knows how to fight like a demon, but he’s haunted by a puzzling past.

When these two join up, they are both given direction in a “Lone Wolf and Cub” sort of way (which is one of my favorite tropes). Murray wants to free Cego from the slave Circles and bring him upworld to join the most prestigious combat academy in the nation.

[GdM] Would you elaborate on how The Combat Codes successfully melds aspects of both science fiction and fantasy?

[AD] I’m heavily influenced by jRPGS, in particular the early Final Fantasy games, which blend magic and technology seamlessly (Magitek). I don’t have traditional magic in the Combat Codes, but there are magic-like elements that integrate with the tech of the world.

For example, there are many different types of elemental Circles that the Grievar Knights fight within; each element influences the combatants in different ways. For example, fighting within a rubellium Circle invokes rage within a fighter or auralite makes a fighter susceptible to a crowd’s cheers and jeers. It’s essentially a magic system.

[GdM] What is Cego like as a character?

[AD] Cego is kind-hearted, but he has a darkness within him that he’s constantly grappling with. This darkness is directly connected to his past, which is slowly revealed throughout the narrative. He’s wise beyond his years in some ways (such as his combat prowess) and yet he’s very childlike in relation to other simple facets of the world.

As a martial arts practitioner, how do you choreograph fight scenes?

I pretty much play a fight scene out in my head, like I’m watching a movie (or live MMA event). I’ll write out the action, but then need to do some serious editing to make it read well. It’s funny, the action itself is not often what propels a fight scene – it’s the spaces between where we are in a fighter’s head, understanding the stakes and emotional toll – that’s where a scene can really come alive. Otherwise, it would just be a dry play-by-play.

[GdM] You were a self-published author before moving over to traditional publishing. You have had your foot in both worlds. What are the differences between the two publishing paths that people might not be aware of?

[AD] I think authors / readers are much more educated on the differences than when I first started self-pub in 2015 because there are a ton of great resources out there. The most important thing to know for self-pub is that it is running a business; you do the writing stuff, but then also hiring, marketing, PR and more. That’s all on you. You need to invest a decent amount of capital to compete, as if you were opening up a restaurant or moving service. If you don’t do this, you have zero chance of success.

[AD] I think authors / readers are much more educated on the differences than when I first started self-pub in 2015 because there are a ton of great resources out there. The most important thing to know for self-pub is that it is running a business; you do the writing stuff, but then also hiring, marketing, PR and more. That’s all on you. You need to invest a decent amount of capital to compete, as if you were opening up a restaurant or moving service. If you don’t do this, you have zero chance of success.

Trad pub is quite an enigma in many ways, and I’ve just started to scratch the surface learning about it. One thing I’ve discovered is once a publisher buys your book, it’s a fantastic accomplishment, but you’re still running up a steep hill to be “successful.”

You really need passion on either path to last.

[GdM] When you and I chatted, you mentioned there were an additional 30k words in the upcoming The Combat Codes. Are there any scenes that you had to cut in service to the story that you were reluctant to cut?

[AD] No! We didn’t cut scenes in the first book. We added many new scenes, which made me so very happy.

[GdM] You play with a lot of SFF tropes in The Combat Codes. What was your favorite to twist and play with, and why?

[AD] As I mentioned, I’m a massive fan of the “Lone Wolf and Cub Trope” – that’s been very popular lately between The Last of Us, Mandalorian and the Witcher. The central dynamic between my main two characters plays on this, though it also melds a similar “Master and Apprentice” trope more often found in martial arts stories or anime.

I also clearly love the academy trope, given a large portion of the story takes place in a combat school. But instead of Dark Academia we’re calling it Fight! Academia.

[GdM] The Combat Codes is written in a way that shows you appreciate Martial Arts films. What is your favorite and why?

[AD] We already talked about Kill Bill, which I’m clearly a fan of. I love old school kung fu movies, my favorite being ‘Fist of Legend’ with Jet Li. Why? Because it’s about Chen Zhen. The best. And of course, the Matrix was life changing for me.

The new cover for The Combat Codes is very striking. How did the new cover come about? What was the design process like?

Of course, I had much less control over the design compared to self-pub. But the Orbit art team included me in the process and shared each iteration as it arrived, as well as asked for feedback on many of the elements. They wanted to go with something striking and symbolic (as opposed to character art) to catch the eye of SFF readers browsing a bookstore.

[GdM] You were a finalist for Self-Published Fantasy Blog Off. What was that experience like for you as a self-published author? It is a cutthroat competition.

[AD] I had so much fun to be honest. I didn’t go into the competition with any expectations, so when Combat Codes did well it was a pleasant surprise. Most of all, I got to meet so many incredible authors (and reviewers). Prior to the competition I had zero connections and zero sense of SFF community. By the time it wrapped, I had a close-knit clan of friends to commiserate with.

[GdM] Have you decided if you will get Cego’s Whelp flux yet?

[AD] AH! I really want to. The problem is, getting a tattoo requires taking time off from practicing combat sports / grappling. I think it’s like at least a week or two? And training is so important for my mental and physical health… I know I’m moving the goal posts… but how about I get one if Combat Codes goes into second printing?

Read The Combat Code by Alexander DarwinThe post An Interview With Alexander Darwin appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

May 14, 2023

Monsters Among Us: Seven Novels and Stories that Will Make You Look Twice at the People (?) Around You

Let’s say you’re riding in an airplane, or better yet, a crowded bus. You and your fellow passengers are all pressed up against each other, nudging and bumping at the knees and elbows, mumbling apologies, trying not to overhear one another’s cellphone conversations, trying not to glance at the pages of one another’s books (or trying, at least, not to get caught glancing). It would be a tough place, there in the middle of that thick stew of bodies, to conceal some monstrous secret—palms covered in lupine fur; acid-yellow eyes wrapped in doubled, reptilian eye-lids; a pair of long, glistening fangs—or to discover such a disquieting secret in the guy on your left buried deep in his hoodie, or the woman standing too close behind you, her cloying perfume not quite masking some other ranker scent.

Why do we love the idea of monsters hidden among us? Perhaps it’s that old othering instinct that looks for strange dangers everywhere and fears finding them, above all, within our own camp. Or perhaps it springs from our own personal sense of otherness and alienation, our compulsion to painstakingly hide away our own monstrosity from polite society. Whatever the case, the tales that present us with monsters at the edge of town, monsters in the house across the street, even monsters right under our noses, have been chilling and delighting readers for a very long time. My debut novel, The God of Endings, with its vampire-passing-as-preschool-teacher protagonist, joins this long literary lineage, but I’d like to offer you seven other tales from classic to contemporary that will make you look twice at the people passing by on the street, or even at your own reflection in the mirror.

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson I would give anything to have gotten to read this electric tale without spoilers back when it was first published. Robert Louis Stevenson’s famed novella, which masterfully tells the tale of a lawyer’s growing concern for a dear friend who’s been acting very curiously of late, has become so iconic that the phrase “Jekyll and Hyde” is now shorthand for astonishing villainy concealed behind a seemingly innocent exterior. Despite the fact that everyone knows the ultimate plot twist, the tale is still utterly gripping and magnificently crafted. If you haven’t read it already, you simply must.

I would give anything to have gotten to read this electric tale without spoilers back when it was first published. Robert Louis Stevenson’s famed novella, which masterfully tells the tale of a lawyer’s growing concern for a dear friend who’s been acting very curiously of late, has become so iconic that the phrase “Jekyll and Hyde” is now shorthand for astonishing villainy concealed behind a seemingly innocent exterior. Despite the fact that everyone knows the ultimate plot twist, the tale is still utterly gripping and magnificently crafted. If you haven’t read it already, you simply must.

Stevenson’s famous exploration of humanity’s basest capacity for evil, has become synonymous with the idea of a split personality. More than a moral tale, this dark psychological fantasy is also a product of its time, drawing on contemporary theories of class, evolution, criminality, and secret lives. Also in this volume are “The Body Snatcher,” which charts the murky underside of Victorian medical practice, and “Olalla,” a tale of vampirism and “The Beast Within” which features a beautiful woman at its center.

Read the bookBram Stoker’s Dracula I’ll be honest, my feelings on Bram Stoker’s choice of the epistolary form for this seminal vampire romp are mixed, but what can’t be denied is the cinematic magnificence and potent creeping dread of so many of the brilliant sections of this novel. Jonathan Harker’s iconic hair-raising stay in Count Dracula’s castle is iconic for good reason. That’s (literally) just the beginning though! There’s also the delightfully chilling coffin-bound voyage of the count; the predation of sweet, unsuspecting Ms. Lucy Westenra; as well as a madman in a jail cell who passes the time by doing disturbing things with flies. Best of all, though, may be the only lightly touched plot point of the count’s sinister ambitions for the city of London. The book is an absolute horror salad and a must read.

I’ll be honest, my feelings on Bram Stoker’s choice of the epistolary form for this seminal vampire romp are mixed, but what can’t be denied is the cinematic magnificence and potent creeping dread of so many of the brilliant sections of this novel. Jonathan Harker’s iconic hair-raising stay in Count Dracula’s castle is iconic for good reason. That’s (literally) just the beginning though! There’s also the delightfully chilling coffin-bound voyage of the count; the predation of sweet, unsuspecting Ms. Lucy Westenra; as well as a madman in a jail cell who passes the time by doing disturbing things with flies. Best of all, though, may be the only lightly touched plot point of the count’s sinister ambitions for the city of London. The book is an absolute horror salad and a must read.

Famous for introducing the character of the vampire Count Dracula, the novel tells the story of Dracula’s attempt to move from Transylvania to England so he may find new blood and spread undead curse, and the battle between Dracula and a small group of men and women led by Professor Abraham Van Helsing.

Dracula has been assigned to many literary genres including vampire literature, horror fiction, the gothic novel and invasion literature. The novel touches on themes such as the role of women in Victorian culture, sexual conventions, immigration, colonialism, and post-colonialism.

Although Stoker did not invent the vampire, he defined its modern form, and the novel has spawned numerous theatrical, film and television interpretations.

Read the bookThe Daemon Lover by Shirley Jackson Does any writer do a better job than Shirley Jackson at exploring that fine, porous boundary between the everyday and the monstrous? Her short story collection, The Lottery and Other Stories, portrays monsters of an astonishing variety, from a town that buys peace through human sacrifice, to a community that punishes a new resident for failing to exhibit enough racism. My favorite tale from the collection, however, is The Daemon Lover, a subtle, magnificently eerie story of a young woman looking desperately for love, and finding it, only to be both literally and figuratively ghosted.

Does any writer do a better job than Shirley Jackson at exploring that fine, porous boundary between the everyday and the monstrous? Her short story collection, The Lottery and Other Stories, portrays monsters of an astonishing variety, from a town that buys peace through human sacrifice, to a community that punishes a new resident for failing to exhibit enough racism. My favorite tale from the collection, however, is The Daemon Lover, a subtle, magnificently eerie story of a young woman looking desperately for love, and finding it, only to be both literally and figuratively ghosted.

One of the most terrifying stories of the twentieth century, Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” created a sensation when it was first published in The New Yorker in 1948.

“Power and haunting,” and “nights of unrest” were typical reader responses. Today it is considered a classic work of short fiction, a story remarkable for its combination of subtle suspense and pitch-perfect descriptions of both the chilling and the mundane.

The Lottery and Other Stories, the only collection of stories to appear during Shirley Jackson’s lifetime, unites “The Lottery” with twenty-four equally unusual short stories. Together they demonstrate Jackson’s remarkable range―from the hilarious to the horrible, the unsettling to the ominous―and her power as a storyteller.

Read the bookSolaris by Stanislaw Lem What if the monster was all around you? What if it was not only all around you, but also within you? What if it could peer inside of you and then take the form it knew you most longed for? This is the predicament in which a crew of astronauts find themselves in Stanislaw Lem’s gorgeous and haunting science fiction novel from 1961. It was adapted into a movie starring George Clooney that’s well worth watching, but don’t deprive yourself of the reading experience, which is equal parts imaginative sci-fi, heart-breaking romance, and pulse-pounding horror.

What if the monster was all around you? What if it was not only all around you, but also within you? What if it could peer inside of you and then take the form it knew you most longed for? This is the predicament in which a crew of astronauts find themselves in Stanislaw Lem’s gorgeous and haunting science fiction novel from 1961. It was adapted into a movie starring George Clooney that’s well worth watching, but don’t deprive yourself of the reading experience, which is equal parts imaginative sci-fi, heart-breaking romance, and pulse-pounding horror.

When psychologist Kris Kelvin arrives at the planet Solaris to study the ocean that covers its surface, he finds himself confronting a painful memory embodied in the physical likeness of a past lover. Kelvin learns that he is not alone in this and that other crews examining the planet are plagued with their own repressed and newly real memories. Could it be, as Solaris scientists speculate, that the ocean may be a massive neural center creating these memories, for a reason no one can identify?

Long considered a classic, Solaris asks the question: Can we understand the universe around us without first understanding what lies within?

Read the bookMary Reilly by Valerie Martin After you follow my advice and read The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, follow it up with Valerie Martin’s Mary Reilly, which tells the same classic harrowing tale, but from the perspective of the house maid. The protagonist’s second-class gender and socio-economic status ratchet up the tensions as Mary tries, by her limited means, to make sense of doors slammed in the night, frightening intruders, the stomping of rough steps on the landing, and the growing dread that all is not well in the Jekyll household.

After you follow my advice and read The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, follow it up with Valerie Martin’s Mary Reilly, which tells the same classic harrowing tale, but from the perspective of the house maid. The protagonist’s second-class gender and socio-economic status ratchet up the tensions as Mary tries, by her limited means, to make sense of doors slammed in the night, frightening intruders, the stomping of rough steps on the landing, and the growing dread that all is not well in the Jekyll household.

From the acclaimed author of the bestselling Italian Fever and award winning Property, comes a fresh twist on the classic Jekyll and Hyde story, a novel told from the perspective of Mary Reilly, Dr. Jekyll’s dutiful and intelligent housemaid.

Faithfully weaving in details from Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic, Martin introduces an original and captivating character: Mary is a survivor–scarred but still strong–familiar with evil, yet brimming with devotion and love. As a bond grows between Mary and her tortured employer, she is sent on errands to unsavory districts of London and entrusted with secrets she would rather not know. Unable to confront her hideous suspicions about Dr. Jekyll, Mary ultimately proves the lengths to which she’ll go to protect him. Through her astute reflections, we hear the rest of the classic Jekyll and Hyde story, and this familiar tale is made more terrifying than we remember it, more complex than we imagined possible.

Read the bookLet The Right One In by John Ajvide Lindqvist It’s as though, when coming up with his internationally bestselling vampire novel Let the Right One In, John Ajvide Lindqvist asked himself, what is the most unexpected and chilling shape that a savage, blood-thirsty monster could take? The answer: a small, frail child with big eyes, a disarming manner, and a strange talent with Rubik’s Cubes. Lindvist’s novel is itself a Rubik’s Cube of intricate plot-lines and finely drawn characters that is both a literary and horror delight.

It’s as though, when coming up with his internationally bestselling vampire novel Let the Right One In, John Ajvide Lindqvist asked himself, what is the most unexpected and chilling shape that a savage, blood-thirsty monster could take? The answer: a small, frail child with big eyes, a disarming manner, and a strange talent with Rubik’s Cubes. Lindvist’s novel is itself a Rubik’s Cube of intricate plot-lines and finely drawn characters that is both a literary and horror delight.

It is autumn 1981 when inconceivable horror comes to Blackeberg, a suburb in Sweden. The body of a teenager is found, emptied of blood, the murder rumored to be part of a ritual killing. Twelve-year-old Oskar is personally hoping that revenge has come at long last―revenge for the bullying he endures at school, day after day.

But the murder is not the most important thing on his mind. A new girl has moved in next door―a girl who has never seen a Rubik’s Cube before, but who can solve it at once. There is something wrong with her, though, something odd. And she only comes out at night. . .

Read the bookThe Apartment Dweller’s Beastiary by Kij Johnson After all the blood and gore and dread of the aforementioned tales, cleanse your monster palette with this whimsical gem of a story that was featured in Clarkesworld and Best American Science Fiction, and will now be included in her upcoming collection The Privilege of the Happy Ending: S/M/L Stories, which comes out in October from Small Beer Press. It offers a helpful encyclopedic resource for renters on the various monsters—some pleasant, some not—that one might expect to encounter peering out of ovens, hiding in the dark depths of cupboards, or roosting in bathroom vents. Thoughtful and lyrical, Kij Johnson’s story will scratch the itch of any who wish Dr. Suess hadn’t only written for children.

After all the blood and gore and dread of the aforementioned tales, cleanse your monster palette with this whimsical gem of a story that was featured in Clarkesworld and Best American Science Fiction, and will now be included in her upcoming collection The Privilege of the Happy Ending: S/M/L Stories, which comes out in October from Small Beer Press. It offers a helpful encyclopedic resource for renters on the various monsters—some pleasant, some not—that one might expect to encounter peering out of ovens, hiding in the dark depths of cupboards, or roosting in bathroom vents. Thoughtful and lyrical, Kij Johnson’s story will scratch the itch of any who wish Dr. Suess hadn’t only written for children.

A surprising and exciting new collection of speculative and experimental stories that explore animal intelligences, gender, and the nature of stories.

The Privilege of the Happy Ending collects award-winning writer Kij Johnson’s speculative fiction from the last decade. The stories explore gender, animals, and the nature of stories, and range in form from classically told tales to deeply experimental works. The collection includes the World Fantasy Award-winning “The Privilege of the Happy Ending” and “The Dream-Quest of Vellitt Boe,” as well as two never-before published works.

Read the book

Jacqueline Holland’s new book The God of Endings is out now.

The post Monsters Among Us: Seven Novels and Stories that Will Make You Look Twice at the People (?) Around You appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

May 13, 2023

An Interview with Jeff VanderMeer

Jeff VanderMeer is a New York Times-bestselling author, editor, and critic, known as one of the pioneers of the New Weird movement in speculative fiction. VanderMeer has published over ten novels, including the Nebula and Shirley Jackson Award-winning Annihilation, the first entry in his Southern Reach series, which has been translated into over thirty-five languages. In 2018, Annihilation was adapted into a feature film by Paramount starring Natalie Portman.

A special twentieth anniversary edition of Jeff VanderMeer’s first novel, Veniss Underground, is being published on April 11, 2023, which includes five bonus stories and a new foreword by Charles Yu. Veniss Underground takes place in the future metropolis of Veniss, where biological material is recycled into art and a terrifying darkness lies hiding in the labyrinthine world beneath the city.

We recently had the honor of discussing with VanderMeer about Veniss Underground, the Southern Reach series, and more.

[GdM] Congratulations on the twenty-year anniversary of your first novel, Veniss Underground. What made you decide to revisit the story?

[GdM] Congratulations on the twenty-year anniversary of your first novel, Veniss Underground. What made you decide to revisit the story?

[JV] MCD/FSG and Picador US had been releasing the rest of my backlist in new editions, like the Ambergris Trilogy, and I’d also been getting more and more involved in environmental causes while writing novels like Hummingbird Salamander that are very direct about ecological issues. When I went back and read Veniss, it felt like it sat comfortably between the direct environmental message of Hummingbird Salamander and the lyrical, experimental one of my novel Dead Astronauts. So, a reissue felt relevant, and also given the actual 20-year anniversary of initial publication occurs during April, which is also the month for Earth Day.

[GdM] How did you originally conceive the idea for this novel and how did it evolve into its final form?

[JV] I wrote the first part, from the point of view of a failed poet/writer, Nicholas, and then mulled the implications of that—sold that part to Interzone under the title “Quin’s Shanghai Circus,” which is also the title of a novel by the little-known US writer Edward Whittemore. The novel contains a scene of a slaughter of circus animals that is deranged and terrible and also one of the more unique and visceral scenes I’d ever read. Somehow, to me, it dovetailed with the biotech themes of my story and also the idea that in the far future even obscure works from our time period might wind up being the inspiration for things in that future. Then, once I realized characters in that first section would be their own viewpoint sections, I had the rest of the novel.

[GdM] The foreword for the new release of Veniss Underground is written by Charles Yu. How did he become involved in the project?

[JV] Charles and I have known each other’s work for quite some time and I’ve always loved how he weds formal experimentation with great emotional intensity. Even when he’s meta, he’s not abstract. Veniss structurally, going from “I” to “you” to “him,” and how those pieces fit together has some sneaky experimentation to it, and I thought the book might appeal to him. He was kind enough to say yes and to have some very interesting things to say about Veniss.

[GdM] Charles has a great quote in the forward, “In Veniss, a reader can see in VanderMeer’s first novel many of the preoccupations found in his later work, the conceptual DNA of a larger project already present, pluripotent stem cells that will go on proliferating for years into many more books, many more beings and worlds and ideas.” Looking back 20 years later, do you find this to be true?

[JV] Yes, definitely. As a writer who has always grown up surrounded by incredible biodiversity and lush habitat, one thing I bring to my fiction is an understanding of how the natural systems of the world are vital—and part of that is always trying to see things from a nonhuman as well as human perspective. This permeates my view of biotech, as well.

[GdM] The diverse narrative styles in Veniss Underground are particularly effective at building emotional connections with the three point-of-view characters, Nicholas, Nicola, and Shadrach. How did you decide to employ first-, second-, and third-person narration across these three perspectives? Did you encounter any particular challenges among these three narrative styles?

[GdM] The diverse narrative styles in Veniss Underground are particularly effective at building emotional connections with the three point-of-view characters, Nicholas, Nicola, and Shadrach. How did you decide to employ first-, second-, and third-person narration across these three perspectives? Did you encounter any particular challenges among these three narrative styles?

[JV] I once read a novel with sixteen different first person points of view, and it exemplified for me that sometimes varying perspectives can be the most effective way of creating characters that don’t merge into one another. Nicholas is definitely ego driven and thus “I” seemed appropriate. The realities of Nicola’s situation demanded second person, while Shadrach’s quest through very strange realms felt like it needed the ability to visualize more that third person affords. Far from creating challenges, deciding on this approach solved all sorts of problems and felt very natural.

[GdM] Veniss Underground is known as one of the defining works of the New Weird movement. How would you describe New Weird today? How has it evolved since the original publication of Veniss Underground twenty years ago?

[JV] Someone once said it was a moment more than a movement, and similarly, for most of us associated with New Weird, we were just passing through, caught in and lifted up by that moment, but we weren’t “New Weird writers.” I’ve certainly gone back and forth on how I feel about the term and sometimes looked askance as new generations discover it and redefine it without knowing the history. But at the same time, more than most “movements” I think “New Weird” as a term simply helps, even now, to make clear a certain visceral yet also cerebral approach to some liminal place that otherwise has no name. Should it keep finding a name and losing that name? Or remain nameless?

[GdM] Veniss Underground features meerkats in a variety of forms. When did your fascination with meerkats begin? Does this relate to the etymological connection between meerkats and your surname?

[JV] [laughs] No, it has no connection to my surname, which means “of the lake”. I just find esoteric mammals fascinating and loved their little communities. But it was funny, because I first saw a photo of them without wider context and thought they were five feet tall. Half-way through writing the novel, I saw a video and realized “oh crap—they’re tiny!” And that’s the why large ones in Veniss are described as biotech combined with other animal genes. One reader called Veniss “Saw meets Meerkat Manor” when the novel first came out, which also kind of cracks me up.

[GdM] How has your process of writing evolved since the publication of Veniss Underground? If you could have given yourself one piece of writing advice at the early stages of your career, what would that be?

[JV] My advice to the younger me would just be: Keep doing what you’re doing, exactly the way you’re doing it. Which is just to say that I’ve always written what’s personal to me and what I’m passionate about and I can’t write any other way. I’d be writing even if I never got published. I’ve just been extraordinarily lucky to find an audience for books, like Veniss, which, after all, features a disembodied wise-cracking meerkat head superglued to a dinner plate. There must be a lot of timelines where that kind of gig doesn’t pay much.

[JV] My advice to the younger me would just be: Keep doing what you’re doing, exactly the way you’re doing it. Which is just to say that I’ve always written what’s personal to me and what I’m passionate about and I can’t write any other way. I’d be writing even if I never got published. I’ve just been extraordinarily lucky to find an audience for books, like Veniss, which, after all, features a disembodied wise-cracking meerkat head superglued to a dinner plate. There must be a lot of timelines where that kind of gig doesn’t pay much.

[GdM] You are known as a passionate environmentalist and have been dubbed “the weird Thoreau” by The New Yorker magazine. You have even restored a natural ecosystem to your own Tallahassee backyard, which now features remarkable biodiversity. Which animals and plants have you been most surprised to discover in the VanderWild?

[JV] Seeing both gray and red foxes has been great, but also the amazing diversity of insects. I can’t keep track of all of the kinds of bees, butterflies, and wasps that now find this place home. And it’s all because of planting so many native plants, each of which has evolved over millions of years to be the host for as well as sometimes food for equally individually evolved insects. That’s what you lose when you clearcut a place, build on it, and then replaced the habitat that was there with generic lawn and some crap myrtles you bought at Home Depot.

[GdM] You clearly find much inspiration in the infinite complexity of nature. Do you feel that your connection and appreciation of nature impact into your writing? And if so, how?

[JV] It’s hard to quantify because when you’re surrounded by something your whole life and feel like you’re part of it, not separate, how do you analyze the impact? It’s just there. Mostly, I guess I have always understood the intrinsic value and personhood of the nonhuman in our world and not understood how we could work against that in so many self-destructive ways. This is the world, not the built environment of parking lots and strip malls. If we give up an idea of the world the way it actually works, we doom ourselves, too. So this is one urgency that drives my fiction, along with the curious fascination with just how complex and amazing Earth is when we don’t destroy parts of it for no particularly good reason.

[GdM] We are very excited about Absolution, the upcoming fourth entry in your Southern Reach series. What can you tell us about this newest installment?

[JV] I’m letting it build organically and slow, driven by so much we don’t know about the Séance & Science Brigade in the first three books, the role of Old Jim in it all, a prior clandestine biological mission not related to the Southern Reach, and a sudden waking vision of white rabbits appearing all over the forgotten coast 30 years before the border comes down. That’s all I can really say at the moment.

[GdM] How do you develop the concepts for your new books? Do you tend to start with the world or the characters, or perhaps with a general theme?

[JV] When you’re a beginning writer, you try to accumulate technique so you have as many different ways of writing a novel as possible. You stop and start a lot and figure out your process. These days I still work hard on continuing education as a writer, but the writing process has definitely changed, in that I spend a lot more time thinking about a piece of fiction before I write it. Over time, I’ve come to realize I’ve written too early before, but never too late. As a result, I tend to write fewer drafts and to know exactly the moment to take notes and scene fragments and begin to write a draft in earnest. It’s always about the viewpoint of the character wedded to some initial situation and image or relationship to landscape. But I also have to know the ending, or some approximation, before I start.

[GdM] Do you have any news about the upcoming TV adaptation of Borne? How does the experience of adapting a book to TV compare to that of adapting to a feature film?

[JV] All I have to say is the team at AMC and the folks now involved in adapting Borne are amazing and there’s been significant progress. The option was just renewed as they get some final pieces in place. But the treatment I’ve seen is incredibly faithful to the book while deviating in ways that make sense for the change in medium. I’m so excited to share more, but that’s all I can really say for now.

Interview by John C. Mauro and Beth Tabler

Read Veniss Underground by Jeff VanderMeer

The post An Interview with Jeff VanderMeer appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

May 12, 2023

REVIEW: Killer by Peter Tonkin

After Peter Benchley’s Jaws was published in 1974, its massive success and that of the 1975 film adaptation inspired a wave of authors and filmmakers hoping to hit the commercial jackpot with their own lurid tales of aquatic creatures terrorizing those poor fools who thought it was safe to go back into the water. Books and films about piranhas and giant octopi followed, and Guy N. Smith even memorably wrote a series of novels about killer crustaceans, beginning with Night of the Crabs in 1976. Larger and more intelligent than Jaws’ iconic great white shark, killer whales also enjoyed a brief moment in the spotlight. Produced by Dino De Laurentiis and starring Richard Harris and Charlotte Rampling, Orca: The Killer Whale was released to theaters in 1977, to poor reviews and middling box office results. Peter Tonkin’s 1979 novel Killer, however, fared much better. Lean and tightly plotted, Killer emphasized the orca’s formidable physicality and intelligence in prose in a way that Orca: The Killer Whale failed to accomplish on the silver screen. While successful in both the United Kingdom—the author’s home country—and in the United States, Tonkin struggled to produce subsequent novels. The aquatic horror boom faded with time, and Killer inevitably fell out of print.

Now, more than four decades since the book’s debut, Killer is back. It received glowing coverage in Grady Hendrix’s Paperbacks from Hell: The Twisted History of ‘70s and ‘80s Horror Fiction (2017) retrospective, and now the novel itself is a part of Valancourt Books’ companion PAPERBACKS FROM HELL line of cult classic horror novels curated by Hendrix and Too Much Horror Fiction blogger Will Errickson. The Valancourt Books release is available in both digital and nostalgia-inspiring mass market paperback format, with Ken Barr’s vintage cover artwork and a new introduction by Hendrix.