Adrian Collins's Blog, page 91

July 1, 2023

An Interview with Emily H. Wilson

Retellings and reimaginings are a huge trend in the traditionally published market right now, and have been for a while. But outside the usual culprits like Greek and Roman mythology and Arthurian legends, they suddenly become a lot sparser – though not any less exciting! One of the brilliant entries into 2023’s retelling line-up is Emily H. Wilson’s debut, Inanna. Taking the goddess of love and war from Ancient Sumer and stories from the Epic of Gilgamesh, she creates a dark epic fantasy trilogy attractive for readers of Grimdark Magazine. We had the opportunity to sit down and chat research, writing and retellings with her ahead of publication next month. Read on for her fascinating thoughts, and click here for our full review of Inanna.

[GdM]: Can you pitch Inanna in one sentence for our readers, please?

[GdM]: Can you pitch Inanna in one sentence for our readers, please?

[EHW]: The man who would become my literary agent asked me for something similar. He said: ‘Tell me in a sentence why anyone would want to pay out their own money for your book.’ This is the reply I sent: ‘This is an epic adventure set in Ancient Sumer, the world’s first civilisation, starring the longest-lived and most powerful female deity in history (Inanna) and also Gilgamesh, the very first literary hero – who wouldn’t want to buy it!’ Since then I’ve realised that Inanna has just as much right to be called the world’s first literary hero as Gilgamesh does, but that’s another story. Editor’s Note: If that’s not a reason to go hit that pre-order button, I don’t think we can be friends, sorry.

[GdM]: Would you be able to go into your research process a bit? What sorts of things helped you create your world and inspired you during the writing process?

[EHW] For book one, I read translations of the ancient myths, for inspiration. Then I read various academic papers about aspects of ancient Sumer, to work out, for example, how many people would

have lived in Uruk in 3,500BC, or, did they have hippos? I visited the British Museum many times to look at the Sumerian objects on display there. It’s nice to know what sort of cup a Sumerian king might drink from, or what kind of necklace a princess would wear. I was also lucky enough to go behind the scenes at the British Museum into the library where many of the ancient clay tablets from Sumer and the Akkadian civilisations that followed are now kept. I also read travelogues from Iraq, written by people like Wilfred Thesiger, for some idea of the physicality of the wilder reaches of the country as it might have been even in the very ancient past. As I read Thesiger, I would make little notes for myself, for example: Add frogs.

[GdM]: One of my standout moments of the book was the royal burial scene. I read in the acknowledgements that this was inspired by an archaeological find. How did you come across it and why did it inspire you to include it?

[EHW]: Yes I took the details of the royal burial scene from an old book that my mother, a former archaeologist, happened to have on the bookshelves in her flat. The book, by the archaeologist Leonard Woolley, describes his finds from the city of Ur in the 1920s and 1930s. In the royal graveyard there they found what Woolley interpreted as a really grisly mass burial, dated about 2,700BC. Whether he was right or not, it looked to him as if more than 70 people were killed or chose to die there, presumably with the idea that they would pass over with the dead queen to another realm. According to Woolley, the women in the group wore what he called silver ribbons in their hair. But one girl died with her ribbon still in her pocket. That very moving, human detail led me to include a mass burial in Inanna.

[GdM]: Was there anything that took you by complete surprise while researching or that you wish you’d been able to include in the finished book?

[EHW]: The amazing sophistication of the Sumerians at such an early date … that continues to be mind-blowing to me. Other than that… The beauty of some of the language in the ancient myths sometimes stops me in my tracks. I’ve taken my favourite lines or phrases and woven them into the text of Inanna, just to have some of that language in there. There’s also a lot of very grim stuff in the myths. The only lines in Inanna that my editor at Titan questioned, as possibly being over the top, were straight out of the myths. A very nasty torture method, for example. Another example: a maggot falling from the nose of a corpse. I couldn’t get everything into Inanna, but luckily there are two more Sumerian books coming! Editor’s Note: Well that’s appropriate for a book reviewed here on Grimdark Magazine!

[GdM]: Who is Inanna to you? Of course, she is the character the book is centred around, but how did you encounter her, how did she come to fascinate you enough to build this world around her?

[EHW]: I first properly noticed Inanna, who was the Sumerian goddess of love and war, while re-reading the (ancient) Epic of Gilgamesh. That sent me down an Inanna rabbit hole, and I discovered for myself the myths in which she is central. The first evidence for Inanna appears in about 3,200 BC. After that she went on to become Ishtar, then at least aspects of her were used to make up Aphrodite and then Venus. That makes her the longest-lived deity in history, and yet almost no one knows her origin story. Plus, she’s probably older than Sumer. To me, her stories have all the markings of tales from deep prehistory.

She is also simply a brilliant character. There’s no settling down into a nice quiet marriage for Inanna; quite the reverse. Put all that together, and it’s just amazing to me that she had to wait all this time for someone to put her centre stage in her own epic. I was very happy to oblige.

[GdM]: Writing a story based on source material isn’t quite the same thing as writing something uniquely your own from the start. What were some of the joys and challenges the process of writing a retelling brought with it?

[EHW]: The joy is that you get a stab at recreating a whole lost world from history, even if it’s only your very personal, fantastical, totally made-up take on that lost world. You get to create a universe that’s fantastical, and yet rooted in history and ancient writings, which for me makes it more delicious. Of course the gods did not really walk the Earth in 4000BC. But what would it be like if they did? Imagining all that was joy, because that’s something I love in a book: time spent in a universe I love being in, but that also offers some sort of deep connection, however fanciful, to our ancient past. The challenge is that Sumerian myths do not fit neatly together into novel form. Far, far, from it. They’re a hot mess. It took me a while to realise that I was not going to be able to create novels that anyone would read unless, when necessary, I parted ways with the myths. Once my characters became real, breathing characters in my mind, that made it easier. When I played fast and loose with some myth, I would just think to myself: the myths that survived got that one thing wrong about Inanna. Of course my version is the accurate one!

[GdM]: Having written a brilliant book inspired by an ancient epic, what do you think distinguishes an excellent retelling?

[EHW]: My favourite mythological retelling is Mary Renault’s two-part take on the story of Theseus and the labyrinth (The King Must Die, and The Bull from the Sea). I think with Mary Renault, what she creates feels so real that it ends up feeling like history. You read her work and you think, how can things have been any different? She creates something that feels true. She did it even more brilliantly in the first two books of her Alexander trilogy (which are amongst my top five favourite novels ever). Of course the Alexander books are historical fiction, but when you’re spinning magic from what at times amounts to not much more than historical scraps, as Renault does, I’m not sure the difference between mythological retellings and historical fiction is that great.

[GdM]: Are you allowed to tell us anything about what you’re working about next?

[EHW]: Inanna was sold as the first part of a trilogy, entitled The Sumerians, so I will be chest-deep in the marshy bogs of Ancient Sumer for at least another year. Right now I’m a good way on with Book Two; I have to send it to my editor at Titan by July 30 this year. It’s currently titled The Secrets of the Gods. It has all the old characters from Inanna, plus some new characters. When I say ‘new’, of course, what I mean is, ‘very very ancient characters from Sumer who have not been wheeled into action by me’.

And then as soon as that’s off my plate, I’ll be starting in earnest upon the final part of the Sumerians trilogy, currently titled The Great Above, which I guess will be due in in July 2024.

[GdM]: What books (or other media) have been filling your creative well?

[EHW]: I recently enjoyed Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld. After the extraordinary boldness of Rodham, I will basically read anything she writes. I’m now reading Demon Copperhead although I haven’t quite settled into yet. Books aside, I am enjoying Seth Rogan and Rose Byrne in Platonic. It’s my post-Succession sticking plaster. Oh and I’m rewatching (the relatively new version of) Battlestar Gallactica with one of sons. Oof, that Pegasus episode in season two! Such great, sustained storytelling.

The post An Interview with Emily H. Wilson appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

REVIEW: Inanna by Emily H. Wilson

This book’s copy starts out by saying “Inanna is an impossibility.” I would agree. Inanna is an impossibility in how quickly and utterly it captivated me and how much I need more of it. Ok, I may be exaggerating a bit. I did expect to fall in love with this book when I heard about it and ran to my emails to request a copy. But this story of the Ancient Mesopotamian goddess of love and war, alongside Gilgamesh, who is often considered to be the first ever literary hero, is both poetic and dark, perfectly targeted specifically at me, and at a Grimdark audience more generally (and do also read our interview with Emily H. Wilson here, for an in-depth look at her research, writing and thought process).

Inanna is the first of the Anunnaki born on Earth, into a warring Pantheon of twelve existing immortal Anunnaki. Crowned the goddess of love and forced into marriage, she soon realises that her path is not to be a smooth one, and the gods’ whims are threatening to tear the world apart. Gilgamesh is a mortal – a human son of the Anunnaki – who finds himself captured and imprisoned. Despite his arrogance and selfishness, Gilgamesh manages to be given one final chance to prove himself. Ninshubar is a powerful warrior woman, but has been cast out of her community after an act of kindness and finds herself persecuted by her own people. Their journeys push the three heroes together and their fates intertwine in a brutal and powerful story.

Inanna is the first of the Anunnaki born on Earth, into a warring Pantheon of twelve existing immortal Anunnaki. Crowned the goddess of love and forced into marriage, she soon realises that her path is not to be a smooth one, and the gods’ whims are threatening to tear the world apart. Gilgamesh is a mortal – a human son of the Anunnaki – who finds himself captured and imprisoned. Despite his arrogance and selfishness, Gilgamesh manages to be given one final chance to prove himself. Ninshubar is a powerful warrior woman, but has been cast out of her community after an act of kindness and finds herself persecuted by her own people. Their journeys push the three heroes together and their fates intertwine in a brutal and powerful story.

The characters are bold and strong, based on ancient tales but still utterly the author’s own. Inanna is considered the model for the later Aphrodite and Venus, but she is much darker in nature – she is a warrior too, she is not the soft seductress or creature of envy the later goddesses have become over the centuries. I also really appreciated Ninshubar, who, while a warrior, was ultimately a human, a person experiencing mercy and kindness, rather than ruthlessness at the core of her personality. It is poetic in many ways that Gilgamesh is rather insufferable – as heroes tend to be, if we dare admit it to ourselves – but still perseveres. A debut that knows what it is doing, and doesn’t shy away from killing its darlings (though, in a world where you never know if death is permanent…).

Probably my favourite element of Inanna, however, is the way Emily H. Wilson manages to marry beautiful, poetic prose with heartbreaking plot. Much of the story itself is dark, darker than expected. There is torture, there is human sacrifice, there is betrayal – this is truly a Grimdark novel, but in a package that makes these elements unexpected when they do occur and therefore so much more impactful. I found that a passage quite early on exemplifies this really well. In it, Inanna is still a child, when she has to say goodbye to her friend. You see, her friend’s father was a king, and with his passing, his household is expected to accompany him into death. The depiction of this is based on an archaeological find, and Wilson succeeds in bringing across the heart-wrenching feeling of senseless loss while writing beautifully. Inanna never comes across as a violent book, it manages to strike that fine balance thanks to the strength of its writing. This has me convinced that Emily H. Wilson is an author to watch. I can’t wait for books two and three of The Sumerians trilogy, and for you all to meet Inanna this summer.

Read Inanna by Emily H. WilsonThe post REVIEW: Inanna by Emily H. Wilson appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

June 30, 2023

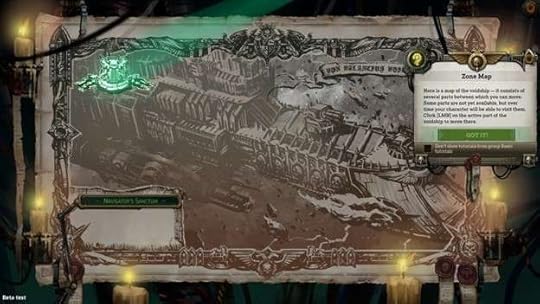

REVIEW: Warhammer 40K: Rogue Trader Impressions

Warhammer 40K: Rogue Trader is an upcoming CRPG developed by Owlcat Games. After achieving considerable success with their previous titles Pathfinder Kingmaker and Pathfinder: Wrath of the Righteous, Owlcat Games are taking a crack at the Warhammer franchise.

As an enormous fan of CRPGs of all kinds, I’ve been waiting for Rogue Trader ever since its announcement. Huge thanks to Owlcat for providing Grimdark Magazine with beta access, and I was the lucky guy who got to play the closed beta.

So a few disclaimers before I go further. First — this is a beta, so there are many unpolished and unfinished things in the game. While the closed beta allows players to access the first three Acts of the story, it is still an incomplete experience. Voice acting in cutscenes isn’t implemented and there’s a fair bit of missing work on optimization, so I’m not judging the game based on this. Speaking of early impressions, the open beta contains a lot of content. Owlcat’s CRPGs are gigantic experiences. The Pathfinder games easily top 100 hours for most players. I got access to the beta last week and with my other commitments, I couldn’t invest dozens of hours into the beta.

While I’m a fan of the Warhammer universe, I’m no expert. Just like my coverage of Warhammer 40K: Darktide last year, I went into Rogue Trader a little rusty on Warhammer’s lore. However, I’m no stranger to CRPGs. Rogue Trader opens up with the incredible visuals and space-opera that is Warhammer, greeting players to a great soundtrack. Starting a new game, I went through the extensive character creation screen, with the option to tweak many difficulty settings from the get-go. I went with a bog standard character for this preview test, focusing on guns as well as the normal difficulty option, so I could get the core experience.

The concept is fairly simple. Originally an heir to the Rogue Trader position, the player is thrust into the role after a classic sabotage/betrayal act. During this opening set piece, you’re introduced to the world through lore inspections, long dialogue sequences and a set of tutorials to learn the ropes. After a chunky set of combat sequences, a mini-boss fight that almost killed me, and lovely deaths, the game opens up properly, and the player can explore the Warhammer universe.

For a beta, I’m really happy that Owlcat Games allowed their backers to play such a large chunk of the game before full release. I did not play the alpha that was just a small, vertical slice of the Act 2 gameplay, so I was pleased they offer such a large experience to delve into. Like other Owlcat games, Warhammer 40K: Rogue Trader is an enormous, complex game with many systems working under the hood, and it’s very easy to get overwhelmed. I spent half an hour in the character creation alone, and the prologue throws a lot of information at the player. It took me a while to get used to everything, but the amount on offer impressed me.

Visual design is great, especially for a CRPG like this. Every environment is handcrafted with a living atmosphere, bolstered by great sound. I felt like I belonged in the gigantic spaceship as I explored its crevices. The key to building these worlds is making sure every corner has something interesting to do — more difficult than it sounds! Environmental storytelling is shown through inspections that describe the scene, alongside NPCs doing their work. In this present build, there’s very little voice acting implemented, and I noticed a lot of repetitive dialogue in the NPC shouts. This is all normal, so hopefully by full release, this will be improved. Remember — the beta version does not represent the full product! Regardless, I was blown away at times by the visuals, and there’s a ton of detail in the environments.

Even the interface is pretty. A full tutorial codex compliments a lore encyclopedia for easy access, and as a lore glutton, I enjoyed delving through everything to learn more. Navigating menus made me feel like a Warhammer elite marine, digging through ancient, sacred texts with all the metallic clunks. When I’m excited about a game’s interface, that is a good thing. It can lag at times, although as a beta I expect that to improve.

Combat is turn-based in Warhammer 40K: Rogue Trader, and offers players many different ways to destroy their enemies. As systems go, I’ve had a blast in battles so far, and in true Warhammer fashion, people die in brutal, destructive ways. There’s nothing more satisfying than unleashing my chain sword attacks on multiple enemies at once, while my squishier gunmen use cover to shield themselves and snipe them from afar. Just with my initial set of characters I had the options of guns, blades and deadly lightning strikes to handle my encounters. What I enjoyed was that friendly fire is realistic. Imagine my surprise the first time when my lighting strike hit my characters as well as toasting my opponents!

Careful positioning is key to survival here. On the base difficulty, I found fights fairly well-balanced. I feel powerful, but my enemies are powerful as well, especially in the boss fights. With five classes and a trove of abilities and skills to pick from, there’s more to uncover than I can in just one go. It will be best to wait until I have the full game before I make a full review of these classes, as balancing game mechanics is an ever-evolving process.

As with games in active development, there are issues to explore. I won’t judge the performance right now as work does need to be done for full release. That is the point of having betas in the first place — as it is the best way to get active player feedback and act on it. From this early build, even mid-tier computers should be able to run Rogue Trader reasonably well. Even on my GTX 1060 laptop, I found performance decent even on high settings. However, I ran into frequent frame drops especially during combat and cutscenes, when characters were at their most active. Animations bugged out occasionally, and NPCs had to catch up by going Sonic speed when it glitched out. I did not crash once, which was a pleasant surprise. The lack of voice acting was a disappointment, but this should be present in the release build.

Performance is probably Owlcat’s greatest challenge for Warhammer 40K: Rogue Trader. Their previous Pathfinder games suffered significant issues with performance and bugs, especially Pathfinder: Kingmaker’s launch. Enormous games like this where there are so many options for players tend to break, but during a time when AAA titles launch in a broken state left and right, the tolerance for bugs is at an all-time low. Balancing the dozens of game mechanics and content dumps is going to be interesting, so I’m interested to see how the late game plays out.

ConclusionOnly time will tell, but so far, my experience of Rogue Trader’s beta state is fairly positive. Warhammer needs more RPGs — the world is too fascinating not to have them. The world and lore are rich in Rogue Trader, and I’m enjoying the turn-based combat system. It is difficult to make combat systems in RPGs that don’t feel repetitive, and Rogue Trader is winning me over in that regard. I wish I had more time to play around with the beta’s mechanics before writing this up, but this is what early impressions are for. While performance is a mild concern, I have faith that most of these issues will be ironed out for the full launch.

We haven’t seen a CRPG like this set in the 40K universe, and if anyone can pull it off, it is Owlcat Games. As of now, Warhammer 40K: Rogue Trader has no set release date, but it should be on track for a release this year.

The post REVIEW: Warhammer 40K: Rogue Trader Impressions appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

June 29, 2023

REVIEW: Savage Crowns by Matt Wallace

In Savage Crowns by Matt Wallace (Savage Rebellion book 3), the empire of Crache is on the verge of crashing down, and its every defence is writhing to maintain its iron grip over its people. The Skrain are out in force to put down the Savage Rebellion, the Protectorate Ministry continue their shadowy machinations to keep the people under Crache’s boot heel, and the Ignobles continue their bloody quest to wrest back control of Crache. In the concluding book of the Savage Rebellion trilogy (Savage Rebellion, Savage Bounty), all will collapse—it’s just a question of who is left standing to claim the rubble of an empire.

Spoilers for books one and two to follow.

The Sparrow General wakes up in a bird cage, the Skrain laughing at her. The battle is lost, she has no idea if her friends live, or how much of her army survives. A Skrain captain gives her a reason to fight. Taru has rejoined the Savage rebellion, having led a devastating charge to save it. Finding out Brio is alive, they have purpose once more. Dyeawan shares control of the Planning Cadre, but that sits in open conflict with the terrifying denizens of the Protectorate Ministry. And in the Bottoms, the Ragged Matron lurks, giving the poor and dispossessed a central figure to fight around and take on the privileged Crache from the bottom up.

The Sparrow General wakes up in a bird cage, the Skrain laughing at her. The battle is lost, she has no idea if her friends live, or how much of her army survives. A Skrain captain gives her a reason to fight. Taru has rejoined the Savage rebellion, having led a devastating charge to save it. Finding out Brio is alive, they have purpose once more. Dyeawan shares control of the Planning Cadre, but that sits in open conflict with the terrifying denizens of the Protectorate Ministry. And in the Bottoms, the Ragged Matron lurks, giving the poor and dispossessed a central figure to fight around and take on the privileged Crache from the bottom up.

In Savage Crowns, Wallace does a great job of wrapping up the story arcs in a satisfying way, drawing together the characters we care about in a way we can care about. The action is visceral, the characters diverse, interesting, and engaging, and it’s certainly, for the most part, a book that is hard to put down. As with the first two books, there are plenty of contemporary problems and themes woven into this fantasy world. However in this book we really see what you’d hope would be modern solutions. Whether those solutions in this context lands with you is going to be entirely up to your tastes in fantasy.

Viewing this through the lens of somebody who prefers their dark fantasy to trickle over into the grimdark side of things, there were a few bits that didn’t land for me for this very reason. The key part for me, and one I feel grimdark readers are unlikely to enjoy, is one of the final twists. It felt like a far too positive outcome was applied to a situation where it just didn’t seem feasible at all. Juxtapose that with a wonderful betrayal (which was brilliantly delivered) earlier in the book as we were building up to the denouement, and it just felt like a forced unrealistic outcome to both provide a moral message outcome, and to link two sections of the book together when perhaps all else had failed.

In addition, one of the secondary character’s deaths really fell flat, in my eyes. And while I recognise that not every character can die on screen, with the pantomime villainy rampant throughout the series it just seemed really lacklustre to not put that particular death on the page in a more engaging way (not that gridmark requires violence on the page, it just seemed weird in the context of the representations of evil in this book).

In Savage Crowns we get the action packed ending that we’ve been waiting for. Wallace delivers both a chaotic and satisfying ending, mixing brutal dark fantasy with modern morality to deliver an enjoyable contemporary-styled medieval story. While certain parts didn’t land with me because of my own personal preferences, I can definitely see a large part of the fantasy community getting a huge kick out of this series.

2.75/5

Read Savage Crowns by Matt WallaceThe post REVIEW: Savage Crowns by Matt Wallace appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

June 28, 2023

REVIEW: The Pomegranate Gate by Ariel Kaplan

Ariel Kaplan isn’t a name that is widely known, but The Pomegranate Gate is set to change that. Set in a world heavily inspired by fifteenth century Spain, its Inquisition and antisemitic culture, this is a poetic fantasy novel steeped in darkness. It combines lyrical writing with meticulous world-building and brilliant characters and douses it all with a good dose of magic – all the ingredients for a breakout success in the genre. Reminiscent of Ava Reid’s The Wolf and the Woodsman and Alix E. Harrow’s The Ten Thousand Doors of January in very different ways, The Pomegranate Gate stands out both thematically and through its writing. I loved it and am looking forward to continuing on with the story in the next instalment.

Toba Peres has always been different in ways she couldn’t quite figure out. Naftaly Peres is lost in dreams. But they are also very different in a tangible way: they are Jews in a hostile way. When the Queen of Serafad, in a world more than slightly reminiscent of fifteenth-century Spain orders all of her nation’s Jews to leave or convert, Toba and Naftaly are forced to flee along with their families. Separated from their caravan by chance, Toba is further drawn away by a mysterious stranger and enters a second world through a pomegranate gate. There, she finds answers, but also far more than she bargained for, as her fate – and that of Naftaly – are bound in conflicts far greater than their individual lives, and sorrow, heartbreak and a rocky road awaits them.

Toba Peres has always been different in ways she couldn’t quite figure out. Naftaly Peres is lost in dreams. But they are also very different in a tangible way: they are Jews in a hostile way. When the Queen of Serafad, in a world more than slightly reminiscent of fifteenth-century Spain orders all of her nation’s Jews to leave or convert, Toba and Naftaly are forced to flee along with their families. Separated from their caravan by chance, Toba is further drawn away by a mysterious stranger and enters a second world through a pomegranate gate. There, she finds answers, but also far more than she bargained for, as her fate – and that of Naftaly – are bound in conflicts far greater than their individual lives, and sorrow, heartbreak and a rocky road awaits them.

As a bookish nerd, I loved reading about Toba. She is one of us at heart, curious, determined and never happier than when she has her nose in a book. Her character arc has her working in a library for large stretches of time, and it is wonderful to read along as she falls into a new world, a new side to herself and partially makes sense of things by holding on to the one thing that is a constant when everything else changes: books. It feels like a serendipitous parallel. I also thoroughly enjoyed Naftaly as a far more grounded, practical character, a tailor used to figuring out solutions based on the physical objects in front of his eyes rather than thinking too far. Still, he is a dreamer, a dreamer in both literal and metaphorical sense, giving him dimension and depth. Together, they made for great reading, varied story-telling and engaging perspectives.

While this mostly sounds rather wholesome, rest assured that there is plenty of meat to enjoy for lovers of the (grim)dark variety of stories. Set in two worlds, the one based on history is very much a Grimdark one – full of danger and prosecution, stacked against our characters. That isn’t to say that the world past the pomegranate gates is any lighter. Danger and betrayal abound there too and Toba especially has to contend with people who should by all rights be on her side intent on destroying her. It is a strong novel with brilliant, lyrical writing, appealing to readers across the fantasy genre. And personally, I need the follow-up desperately.

Read The Pomegranate Gate by Ariel KaplanThe post REVIEW: The Pomegranate Gate by Ariel Kaplan appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

The best dark SFF of 2023 so far

It’s that time of the year. Apologise to your TBR piles in advance because the Grimdark Magazine review team is about to make it rain new books at your house! 2023 had had some brilliant dark SFF drop so far, and there is a bit of something for everyone in our list with city-sized AI robots, dragons, necromancy, empires overthrown, dreams crushed and hope clawed for. If you’re looking for something new to read, we’ve got you covered!

Babel by R.F. KuangAndrew Jaden There are books you devour. And then there are books you nibble at in small chunks, books you need to savour because they are revelatory in so many different ways. And Babel by R.F. Kuang is one of the latter. Subtitled , or the Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators’ Revolution, it is made clear from the beginning that this isn’t your average dark academia themed fantasy novel.

There are books you devour. And then there are books you nibble at in small chunks, books you need to savour because they are revelatory in so many different ways. And Babel by R.F. Kuang is one of the latter. Subtitled , or the Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators’ Revolution, it is made clear from the beginning that this isn’t your average dark academia themed fantasy novel.

Read the full review here.

About the bookThe city of dreaming spires.

It is the centre of all knowledge and progress in the world.

And at its centre is Babel, the Royal Institute of Translation. The tower from which all the power of the Empire flows.

Orphaned in Canton and brought to England by a mysterious guardian, Babel seemed like paradise to Robin Swift.

Until it became a prison…

But can a student stand against an empire?

Read the bookTo Shape a Dragon’s Breath by Moniquill BlackgooseBrigid Flanagan In a grim world damaged by dragon wars, colonization, and industrialization, To Shape a Dragon’s Breath follows the story of a young Indigenous girl who becomes the hope of her people. Instead of Dragon rider, her people call her Nampeshiweisit. Throughout the book, Blackgoose digs up the older roots of fantasy and plants new life with original ideas, growing this novel into a stronger, more thoughtful story. In a whaling village, a girl watches as a rare dragon leaves its egg. It hatches in front of Anequs, who finds herself in a bond with a baby dragon. Anequs is led into the horrid, complicated politics between her people and the colonial government, which requires that she train in dragoneering at a dragon academy, far away from her people.

In a grim world damaged by dragon wars, colonization, and industrialization, To Shape a Dragon’s Breath follows the story of a young Indigenous girl who becomes the hope of her people. Instead of Dragon rider, her people call her Nampeshiweisit. Throughout the book, Blackgoose digs up the older roots of fantasy and plants new life with original ideas, growing this novel into a stronger, more thoughtful story. In a whaling village, a girl watches as a rare dragon leaves its egg. It hatches in front of Anequs, who finds herself in a bond with a baby dragon. Anequs is led into the horrid, complicated politics between her people and the colonial government, which requires that she train in dragoneering at a dragon academy, far away from her people.

Read the full review here.

About the bookThe remote island of Masquapaug has not seen a dragon in many generations—until fifteen-year-old Anequs finds a dragon’s egg and bonds with its hatchling. Her people are delighted, for all remember the tales of the days when dragons lived among them and danced away the storms of autumn, enabling the people to thrive. To them, Anequs is revered as Nampeshiweisit—a person in a unique relationship with a dragon.

Unfortunately for Anequs, the Anglish conquerors of her land have different opinions. They have a very specific idea of how a dragon should be raised, and who should be doing the raising—and Anequs does not meet any of their requirements. Only with great reluctance do they allow Anequs to enroll in a proper Anglish dragon school on the mainland. If she cannot succeed there, her dragon will be killed.

For a girl with no formal schooling, a non-Anglish upbringing, and a very different understanding of the history of her land, challenges abound—both socially and academically. But Anequs is smart, determined, and resolved to learn what she needs to help her dragon, even if it means teaching herself. The one thing she refuses to do, however, is become the meek Anglish miss that everyone expects.

Anequs and her dragon may be coming of age, but they’re also coming to power, and that brings an important realization: the world needs changing—and they might just be the ones to do it.

Read the bookThe Lies of the Ajungo by Moses Ose UtomiSaberin Set in an African-inspired world full of wonder and horror, Moses Ose Utomi’s novella The Lies of the Ajungo is a powerful, beguiling blend of parable and fantasy. As part of a bargain with the powerful Ajungo Empire, the citizens of the City of Lies sacrifice their tongues when they turn thirteen in exchange for just enough water to survive. When twelve-year-old Tutu realises just how ill his mother has become, he bravely sets out in search of water, determined to return to his city a hero. His journey through the Forever Desert is filled with danger, hope and heartbreak. Over the course of his travels he grows into a man, but also learns the true darkness behind the City of Lies and the realities of the Ajungo.

Set in an African-inspired world full of wonder and horror, Moses Ose Utomi’s novella The Lies of the Ajungo is a powerful, beguiling blend of parable and fantasy. As part of a bargain with the powerful Ajungo Empire, the citizens of the City of Lies sacrifice their tongues when they turn thirteen in exchange for just enough water to survive. When twelve-year-old Tutu realises just how ill his mother has become, he bravely sets out in search of water, determined to return to his city a hero. His journey through the Forever Desert is filled with danger, hope and heartbreak. Over the course of his travels he grows into a man, but also learns the true darkness behind the City of Lies and the realities of the Ajungo.

Read the full review here.

About the bookThey say there is no water in the City of Lies. They say there are no heroes in the City of Lies. They say there are no friends beyond the City of Lies. But would you believe what they say in the City of Lies?

In the City of Lies, they cut out your tongue when you turn thirteen, to appease the terrifying Ajungo Empire and make sure it continues sending water. Tutu will be thirteen in three days, but his parched mother won’t last that long. So Tutu goes to his oba and makes a deal: she provides water for his mother, and in exchange he will travel out into the desert and bring back water for the city. Thus begins Tutu’s quest for the salvation of his mother, his city, and himself.

The Lies of the Ajungo opens the curtains on a tremendous world, and begins the epic fable of the Forever Desert. With every word, Moses Ose Utomi weaves magic.

Read the bookForest of Foes by Matthew HarffyAaron S. Jones The ninth book of The Bernicia Chronicles continues the adventures of Beobrand as readers are transported back to Frankia in AD 652. Beobrand has been ordered to lead a group of pilgrims to the holy city of Rome. He plans to journey quickly and return to Northumbria without delay, but as always – nothing is that simple for Beobrand and the road is long and perilous…

The ninth book of The Bernicia Chronicles continues the adventures of Beobrand as readers are transported back to Frankia in AD 652. Beobrand has been ordered to lead a group of pilgrims to the holy city of Rome. He plans to journey quickly and return to Northumbria without delay, but as always – nothing is that simple for Beobrand and the road is long and perilous…

Read the full review here.

About the bookBeobrand finds himself caught between the perilous intrigues of royalty and the Church in this latest thrilling Bernicia Chronicles adventure.

AD 652. Beobrand has been ordered to lead a group of pilgrims to the holy city of Rome. Chief among them is Wilfrid, a novice of the Church with some surprisingly important connections. Taking only Cynan and some of his best men, Beobrand hopes to make the journey through Frankia quickly and return to Northumbria without delay, though the road is long and perilous.

But where Beobrand treads, menace is never far behind. The lands of the Merovingian kings are rife with intrigue. The queen of Frankia is unpopular and her ambitious schemes, though benevolent, have made her powerful enemies. Soon Wilfrid, and Beobrand, are caught up in sinister plots against the royal house.

After interrupting a brutal ambush in a forest, Beobrand and his trusted gesithas find their lives on the line. Dark forces will stop at nothing to seize control of the Frankish throne, and Beobrand is thrown into a deadly race for survival through foreign lands where he cannot be sure who is friend and who is foe.

The only certainty is that if he is to save his men, thwart the plots, and unmask his enemies, blood will flow.

Read the bookSome Desperate Glory by Emily TeshBeth Tabler Some Desperate Glory is a story about a young woman who discovers everything she believes in is a lie. It’s about propaganda, radicalisation, deprogramming, and transformation. It imagines a world where humanity went to war against the alien threat and lost. Our protagonist, Valkyr, has grown up as part of the last resistance – or so she thinks. She has trained since childhood to avenge the murder of the Earth; but the people in power on Gaea Station, where she grew up, have other uses for her. (-Quote from the author)

Some Desperate Glory is a story about a young woman who discovers everything she believes in is a lie. It’s about propaganda, radicalisation, deprogramming, and transformation. It imagines a world where humanity went to war against the alien threat and lost. Our protagonist, Valkyr, has grown up as part of the last resistance – or so she thinks. She has trained since childhood to avenge the murder of the Earth; but the people in power on Gaea Station, where she grew up, have other uses for her. (-Quote from the author)

Read our interview with Emily Tesh, here.

About the bookWhile we live, the enemy shall fear us.

Since she was born, Kyr has trained for the day she can avenge the murder of planet Earth. Raised in the bowels of Gaea Station alongside the last scraps of humanity, she readies herself to face the Wisdom, the powerful, reality-shaping weapon that gave the majoda their victory over humanity.

They are what’s left. They are what must survive. Kyr is one of the best warriors of her generation, the sword of a dead planet. When Command assigns her brother to certain death and relegates her to Nursery to bear sons until she dies trying, she knows she must take humanity’s revenge into her own hands.

Alongside her brother’s brilliant but seditious friend and a lonely, captive alien, Kyr escapes from everything she’s known into a universe far more complicated than she was taught and far more wondrous than she could have imagined.

Read the bookThe Strange by Nathan BallingrudRyan Howse The Strange by Nathan Ballingrud is a True Grit-style western on Mars that slowly veers into horror, and westerns and horror are two of my favorite things. The Martian colonies have been cut off from supplies since The Silence, when all communication and shipments from Earth stopped. The colonists become more desperate. When Anabelle’s father’s restaurant is robbed, and they took the last memento of her mother, Anabelle pursues the thieves through an unnerving Martian desert and into even stranger places.

The Strange by Nathan Ballingrud is a True Grit-style western on Mars that slowly veers into horror, and westerns and horror are two of my favorite things. The Martian colonies have been cut off from supplies since The Silence, when all communication and shipments from Earth stopped. The colonists become more desperate. When Anabelle’s father’s restaurant is robbed, and they took the last memento of her mother, Anabelle pursues the thieves through an unnerving Martian desert and into even stranger places.

Full review to come.

About the book1931, New Galveston, Mars: Fourteen-year-old Anabelle Crisp sets off through the wastelands of the Strange to find Silas Mundt’s gang who have stolen her mother’s voice, destroyed her father, and left her solely with a need for vengeance.

Since Anabelle’s mother left for Earth to care for her own ailing mother, her days in New Galveston have been spent at school and her nights at her laconic father’s diner with Watson, the family Kitchen Engine and dishwasher as her only companion. When the Silence came, and communication and shipments from Earth to its colonies on Mars stopped, life seemed stuck in foreboding stasis until the night Silas Mundt and his gang attacked.

At once evoking the dreams of an America explored in Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles and the harder realities of frontier life in Charles Portis True Grit, Ballingrud’s novel is haunting in its evocation of Anabelle’s quest for revenge amidst a spent and angry world accompanied by a domestic Engine, a drunken space pilot, and the toughest woman on Mars.

Nathan Ballingrud’s stories have been adapted into the film Wounds and the Hulu series Monsterland, The Strange is his first novel.

Read the bookForge of the High Mage by Ian C. EsslemontJames Tivendade Esslemont continues his early empire Path to Ascendancy sequence impressively with the fourth instalment, Forge of the High Mage. This series is a prequel to the events of Erikson‘s Malazan Book of the Fallen and Esslemont’s own Novels of the Malazan Empire, with this entry seeing Kellanved (The Emperor), Dancer (Master Assassin), Dassem Ultor (The Sword), Tayschrenn (High Mage) and their armies advancing into Falar. Awaiting them in or approaching their destination are a powerful religious faction that worships the elder god, Mael, the tribes of the Jhek that includes soletaken wolf and bear warriors, formidable Crimson Guard mercenaries, and something mysterious and ancient that, if left unchecked, could cause devastating damage to the surrounding environment and those within the vicinity.

Esslemont continues his early empire Path to Ascendancy sequence impressively with the fourth instalment, Forge of the High Mage. This series is a prequel to the events of Erikson‘s Malazan Book of the Fallen and Esslemont’s own Novels of the Malazan Empire, with this entry seeing Kellanved (The Emperor), Dancer (Master Assassin), Dassem Ultor (The Sword), Tayschrenn (High Mage) and their armies advancing into Falar. Awaiting them in or approaching their destination are a powerful religious faction that worships the elder god, Mael, the tribes of the Jhek that includes soletaken wolf and bear warriors, formidable Crimson Guard mercenaries, and something mysterious and ancient that, if left unchecked, could cause devastating damage to the surrounding environment and those within the vicinity.

Read the full review here.

About the bookAfter decades of warfare, Malazan forces are now close to consolidating the Quon Talian mainland. Yet it is at this moment that Emperor Kellanved orders a new campaign far to the north: the invasion of Falar.

Since the main Malazan armies are otherwise engaged in Quon Tali, a collection of orphaned units and broken squads has been brought together under Fist Dujek – himself recovering from the loss of an arm – to fight this new campaign. A somewhat rag-tag army, joined by a similarly motley fleet under the command of the Emperor himself.

There are however those who harbour doubts regarding the stewardship of Kellanved and his cohort Dancer, and as the Malazan force heads north, it encounters an unlooked-for and most unwelcome threat – unspeakable and born of legend, it has woken and will destroy all who stand in its way. Most appalled by this is Tayschrenn, the untested High Mage of the Empire. He is all-too aware of the true nature of this ancient horror – and his own inadequacy in having to confront it. Yet confront it he must, alongside the most unlikely of allies . . .

And then the theocracy of Falar is itself far from defenceless – its priests are in possession of a weapon so terrifying it has not been unleashed for centuries. Named the Jhistal, it was rumoured to be a gift from the sea-god Mael. But two can play at that game, for the Emperor sails towards Falar aboard his flagship Twisted – a vessel that is itself thought to be not entirely of this world . . . Here, then, in the tracts of the Ice Wastes and among the islands of Falar, the Empire of Malaz faces two seemingly insurmountable tests – each one potentially the origin of its destruction . . .

These are bloody, turbulent and treacherous times for all caught up in the forging of the Malazan Empire.

Read the bookThe Fourth Wing by Rebecca YarrosSally Berrow Fourth Wing is a rip-roaring, breathlessly exciting war school fantasy featuring high stakes, a tough as nails heroine, a brooding love interest, epic power-up moments, and wonderfully sarcastic dragons. High literature it is not, but it’s still the best book I’ve read all year.

Fourth Wing is a rip-roaring, breathlessly exciting war school fantasy featuring high stakes, a tough as nails heroine, a brooding love interest, epic power-up moments, and wonderfully sarcastic dragons. High literature it is not, but it’s still the best book I’ve read all year.

Read the full review here.

About the bookTwenty-year-old Violet Sorrengail was supposed to enter the Scribe Quadrant, living a quiet life among books and history. Now, the commanding general―also known as her tough-as-talons mother―has ordered Violet to join the hundreds of candidates striving to become the elite of Navarre: dragon riders.

But when you’re smaller than everyone else and your body is brittle, death is only a heartbeat away…because dragons don’t bond to “fragile” humans. They incinerate them.

With fewer dragons willing to bond than cadets, most would kill Violet to better their own chances of success. The rest would kill her just for being her mother’s daughter―like Xaden Riorson, the most powerful and ruthless wingleader in the Riders Quadrant.

She’ll need every edge her wits can give her just to see the next sunrise.

Yet, with every day that passes, the war outside grows more deadly, the kingdom’s protective wards are failing, and the death toll continues to rise. Even worse, Violet begins to suspect leadership is hiding a terrible secret.

Friends, enemies, lovers. Everyone at Basgiath War College has an agenda―because once you enter, there are only two ways out: graduate or die.

Read the bookThe Adventures of Amina al-Sirafi by Shannon ChakrabortyFabienne Scwhizer Some books are so magical you know within a few pages that they will end up on your favourites shelf. The Adventures of Amina al-Sirafi by Shannon Chakraborty is such a book. I was smitten by the end of the historical preface, in love by the time I first got to glimpse Amina herself. Shannon Chakraborty wrote herself into readers’ hearts with the Daevabad series – fans will spot a fun easter egg in this – but has seriously levelled up with this new book. Telling the magical tale of Amina al-Sirafi, medieval pirate in the Pacific within the historical context of the Crusades and Holy War, this is compelling, twisty and brilliant.

Some books are so magical you know within a few pages that they will end up on your favourites shelf. The Adventures of Amina al-Sirafi by Shannon Chakraborty is such a book. I was smitten by the end of the historical preface, in love by the time I first got to glimpse Amina herself. Shannon Chakraborty wrote herself into readers’ hearts with the Daevabad series – fans will spot a fun easter egg in this – but has seriously levelled up with this new book. Telling the magical tale of Amina al-Sirafi, medieval pirate in the Pacific within the historical context of the Crusades and Holy War, this is compelling, twisty and brilliant.

Read the full review here.

About the bookAmina al-Sirafi should be content. After a storied and scandalous career as one of the Indian Ocean’s most notorious pirates, she’s survived backstabbing rogues, vengeful merchant princes, several husbands, and one actual demon to retire peacefully with her family to a life of piety, motherhood, and absolutely nothing that hints of the supernatural.

But when she’s tracked down by the obscenely wealthy mother of a former crewman, she’s offered a job no bandit could refuse: retrieve her comrade’s kidnapped daughter for a kingly sum. The chance to have one last adventure with her crew, do right by an old friend, and win a fortune that will secure her family’s future forever? It seems like such an obvious choice that it must be God’s will.

Yet the deeper Amina dives, the more it becomes alarmingly clear there’s more to this job, and the girl’s disappearance, than she was led to believe. For there’s always risk in wanting to become a legend, to seize one last chance at glory, to savor just a bit more power…and the price might be your very soul.

Read the bookThe Book that Wouldn’t Burn by Mark LawrenceJohn Mauro Reading Mark Lawrence’s latest novel, The Book that Wouldn’t Burn, feels like having your mind blown in slow motion. This first volume of his new Library Trilogy is a blend of science fiction and fantasy but at the same time transcends conventional genre labels.

Reading Mark Lawrence’s latest novel, The Book that Wouldn’t Burn, feels like having your mind blown in slow motion. This first volume of his new Library Trilogy is a blend of science fiction and fantasy but at the same time transcends conventional genre labels.

Read the full review here.

About the bookThe boy has lived his whole life trapped within a book-choked chamber older than empires and larger than cities.

The girl has been plucked from the outskirts of civilization to be trained as a librarian, studying the mysteries of the great library at the heart of her kingdom.

They were never supposed to meet. But in the library, they did.

Their stories spiral around each other, across worlds and time. This is a tale of truth and lies and hearts, and the blurring of one into another. A journey on which knowledge erodes certainty and on which, though the pen may be mightier than the sword, blood will be spilled and cities burned.

Read the bookNight Angel Nemesis by Brent WeeksFiona Denton Night Angel Nemesis is the latest novel from bestselling fantasy author Brent Weeks and marks a return to the world of his debut trilogy. The Night Angel Trilogy of The Way of Shadows, Shadow’s Edge, and Beyond the Shadows was released in 2008 by Orbit, before Grimdark Magazine was even a twinkle in the eye of the Internet. I cannot tell you how much I loved that original trilogy, but by now, my copies of the books are held together with sticky tape and good intentions. I was gleeful at returning to Week’s world with Night Angel Nemesis, the first of The Kylar Chronicles.

Night Angel Nemesis is the latest novel from bestselling fantasy author Brent Weeks and marks a return to the world of his debut trilogy. The Night Angel Trilogy of The Way of Shadows, Shadow’s Edge, and Beyond the Shadows was released in 2008 by Orbit, before Grimdark Magazine was even a twinkle in the eye of the Internet. I cannot tell you how much I loved that original trilogy, but by now, my copies of the books are held together with sticky tape and good intentions. I was gleeful at returning to Week’s world with Night Angel Nemesis, the first of The Kylar Chronicles.

Read the full review here.

About the bookAfter the war that cost him so much, Kylar Stern is broken and alone. He’s determined not to kill again, but an impending amnesty will pardon the one murderer he can’t let walk free. He promises himself this is the last time. One last hit to tie up the loose ends of his old, lost life.

But Kylar’s best — and maybe only — friend, the High King Logan Gyre, needs him. To protect a fragile peace, Logan’s new kingdom, and the king’s twin sons, he needs Kylar to secure a powerful magical artifact that was unearthed during the war.

With rumors that a ka’kari may be found, adversaries both old and new are on the hunt. And if Kylar has learned anything, it’s that ancient magics are better left in the hands of those he can trust.

If he does the job right, he won’t need to kill at all. This isn’t an assassination — it’s a heist.

But some jobs are too hard for an easy conscience, and some enemies are so powerful the only answer lies in the shadows.

Read the bookGothic by Philip FracassiRobin Marx Philip Fracassi’s new horror novel Gothic opens with its protagonist Tyson Parks trapped in an untenable situation. Twenty years ago he was a New York Times bestselling horror author, hailed as Stephen King’s heir apparent. But times have changed and his more recent books have been commercial and critical failures. His smug Manhattan agent—lounging in the posh corner office Tyson’s labor and talent financed—berates him like a child for falling out of step with the fickle tastes of the fiction market. Tyson’s latest manuscript is both late and diverges significantly from the book he pitched to his anxious publisher. The creative well is running dry and his business partners are growing impatient while his debts mercilessly compound.

Philip Fracassi’s new horror novel Gothic opens with its protagonist Tyson Parks trapped in an untenable situation. Twenty years ago he was a New York Times bestselling horror author, hailed as Stephen King’s heir apparent. But times have changed and his more recent books have been commercial and critical failures. His smug Manhattan agent—lounging in the posh corner office Tyson’s labor and talent financed—berates him like a child for falling out of step with the fickle tastes of the fiction market. Tyson’s latest manuscript is both late and diverges significantly from the book he pitched to his anxious publisher. The creative well is running dry and his business partners are growing impatient while his debts mercilessly compound.

Read the full review here.

About the bookOn his 59th birthday, Tyson Parks—a famous, but struggling, horror writer—receives an antique

desk from his partner, Sarah, in the hopes it will rekindle his creative juices. Perhaps inspire him to write another best-selling novel and prove his best years aren’t behind him.

A continent away, a mysterious woman makes inquiries with her sources around the world, seeking the whereabouts of a certain artifact her family has been hunting for centuries. With the help of a New York City private detective, she finally finds what she’s been looking for.

It’s in the home of Tyson Parks.-

Meanwhile, as Tyson begins to use his new desk, he begins acting… strange. Violent. His writing more disturbing than anything he’s done before. But publishers are paying top dollar, convinced his new work will be a hit, and Tyson will do whatever it takes to protect his newfound success. Even if it means the destruction of the ones he loves.

Even if it means his own sanity.

Read the bookA Shade of Madness by Thiago AbdallaRai Furniss-Greasley A Shade of Madness follows on where successful debut A Touch of Light left off and dives straight back into a world in increasing peril. Thiago Abdalla continues to demonstrate excellent worldbuilding and the exploration of flawed characters trying to do what they believe is the right thing. Far from having any ‘middle book syndrome’, A Shade of Madness is another strong entry into The Ashes of Avarin series that promises more dark, high fantasy with a heavy focus on both death and, well, madness.

A Shade of Madness follows on where successful debut A Touch of Light left off and dives straight back into a world in increasing peril. Thiago Abdalla continues to demonstrate excellent worldbuilding and the exploration of flawed characters trying to do what they believe is the right thing. Far from having any ‘middle book syndrome’, A Shade of Madness is another strong entry into The Ashes of Avarin series that promises more dark, high fantasy with a heavy focus on both death and, well, madness.

Read the full review here.

About the bookAs griffin riders clash against airships above and hordes of madmen below, Lynn finds herself surrounded by enemies. Ones that will test the limits of her faith. To defeat them, she must risk everything… including her sanity.

Adrian has lost the Legion, but new magics on foreign shores might be the answer he needs to rebuild his army. His return to the Domain will bring vengeance, and the hope that he will finally prove himself to his father.

Nasha’s curse has taken on a new, terrifying shape. She dreads it could be just what the dead goddess needs to escape from Her prison within the Silent Earth. Will she be strong enough to resist, or will Nasha’s curse give rise to the monster she fears to become?

Madness is spreading and it cares not for the borders of men.

Read the bookThe Tyranny of Faith by Richard SwanAdrian Collins In The Tyranny of Faith by Richard Swan, our protagonist Helena, Vonvalt, and his retainers travel from Galen’s Vale to the empire’s capital of Sova to unravel the pit of treachery it has become. Old mentors and leaders, and some of the very most senior justices in Vonvalt’s Order of Magistrates must be cut from the body of the empire, lest they poison if further. And if the treachery and intrigue and action stopped there this would still be a very good book. But because it’s a fucking great book, it doesn’t stop there.

In The Tyranny of Faith by Richard Swan, our protagonist Helena, Vonvalt, and his retainers travel from Galen’s Vale to the empire’s capital of Sova to unravel the pit of treachery it has become. Old mentors and leaders, and some of the very most senior justices in Vonvalt’s Order of Magistrates must be cut from the body of the empire, lest they poison if further. And if the treachery and intrigue and action stopped there this would still be a very good book. But because it’s a fucking great book, it doesn’t stop there.

Read the full review here.

About the bookA Justice’s work is never done.

The Battle of Galen’s Vale is over, but the war for the Empire’s future has just begun. Concerned by rumors that the Magistratum’s authority is waning, Sir Konrad Vonvalt returns to Sova to find the capital city gripped by intrigue and whispers of rebellion. In the Senate, patricians speak openly against the Emperor, while fanatics preach holy vengeance on the streets.

Yet facing down these threats to the throne will have to wait, for the Emperor’s grandson has been kidnapped – and Vonvalt is charged with rescuing the missing prince. His quest will lead him – and his allies Helena, Bressinger and Sir Radomir – to the southern frontier, where they will once again face the puritanical fury of Bartholomew Claver and his templar knights – and a dark power far more terrifying than they could have imagined.

Read the bookNeed more books for your TBR?Check out our previous year’s recommendations:

Best of 2022Best of 2021Best of 2020Best of 2019Best of 2018The post The best dark SFF of 2023 so far appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

June 27, 2023

REVIEW: Perilous Times by Thomas D Lee

Perilous Times is Thomas D Lee’s debut novel. It is a wickedly funny Arthurian inspired satirical fantasy novel, set in a contemporary world. In it, and the idea where the title derives from, the knights of the road table rise up from a magical sleep whenever England is in peril. This means they have been called upon to help in almost every battle in English history, from Agincourt to the Somme. In Perilous Times, the current peril resurrecting the knights is a doomsday level of climate change – mass extinction of birds and bugs, rising sea levels meaning a lot of the country is underwater, and it is twenty-five pounds a pint in the north of England. Oh, and a dragon is on the loose. Perilous times indeed.

Now, picking up an Arthurian-inspired story, I did expect more of the big man. Arthur does appear later in the novel, but he is very different from how the legends have had us remember him. However, the knights we see the most are Kay, Arthur’s brother, and Lancelot. These, and the other Arthur-linked characters, are names that I recognised, but Lee’s presentation of them, and the others taken from the legend, feels new. Which is remarkable, given just how many Arthurian retellings there are out there. The original characters in Perilous Times are also very good creations of Lee’s, particularly one who is arguably the novel’s main character, Mariam, whom I hope other readers will love as much as I did. I think that Lee has done a stellar job in terms of representation with all of the characters, and none feel like token-inclusive gestures added to tick a box on a diversity checklist.

Now, picking up an Arthurian-inspired story, I did expect more of the big man. Arthur does appear later in the novel, but he is very different from how the legends have had us remember him. However, the knights we see the most are Kay, Arthur’s brother, and Lancelot. These, and the other Arthur-linked characters, are names that I recognised, but Lee’s presentation of them, and the others taken from the legend, feels new. Which is remarkable, given just how many Arthurian retellings there are out there. The original characters in Perilous Times are also very good creations of Lee’s, particularly one who is arguably the novel’s main character, Mariam, whom I hope other readers will love as much as I did. I think that Lee has done a stellar job in terms of representation with all of the characters, and none feel like token-inclusive gestures added to tick a box on a diversity checklist.

I was surprised by how much I enjoyed Perilous Times. I thought I would like it when I picked it up, thinking it would be a palate cleanser from darker novels, a jolly romp with knights of old. Which it is. But it is also so much more than that. Lee’s writing is nuanced, and he covers some serious issues in a careful and considerate way. The loss of loved ones, trying to find a sense of belonging in a world that doesn’t seem to fit you, questioning why you fight when fighting seems to get you nowhere, and hope even when hope feels foolish. Perilous Times is sometimes sarcastic and cynical but equally poignant and touching at others. So as well as being a delightful escapist fantasy, with some jolly romping with knights, Lee’s emotive writing will stick with you long after you have read the final page. A huge thank you to Thomas D Lee and the team at Orbit for sending a copy to be able to review it.

4/5

Read Perilous Times by Thomas D LeeThe post REVIEW: Perilous Times by Thomas D Lee appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

June 26, 2023

REVIEW: The Once Yellow House by Gemma Amor

Religious occultism collides with the color yellow in Gemma Amor’s latest horror novel, The Once Yellow House. The Bram Stoker Award-nominated author adopts an entirely epistolary format for The Once Yellow House, with the story told through a combination of diary entries, newspaper clippings, and transcripts of audio recordings.

The plot of The Once Yellow House focuses on the events leading up to the Yellow Massacre of 2020, in which 347 members of a cult known as “The Retinue” were brutally killed on a property in upstate New York called the Once Yellow House. The Once Yellow House was owned by a married couple, Thomas and Hope Gloucester. Thomas is presumed dead from the Yellow Massacre, while Hope is now missing and needed for questioning.

The plot of The Once Yellow House focuses on the events leading up to the Yellow Massacre of 2020, in which 347 members of a cult known as “The Retinue” were brutally killed on a property in upstate New York called the Once Yellow House. The Once Yellow House was owned by a married couple, Thomas and Hope Gloucester. Thomas is presumed dead from the Yellow Massacre, while Hope is now missing and needed for questioning.

Thomas originally started The Retinue online, gaining a following that somehow expanded exponentially after he and Hope moved into the Once Yellow House. Before long, cult members gathered to camp out in their yard, treating Thomas as a divine figure.

This epistolary style of The Once Yellow House is especially effective at revealing bits of information, allowing readers the chance to put together pieces of the puzzle. Gemma Amor also makes brilliant use of this format to delve into the minds of her two main protagonists: the presumably widowed Hope and one of the few cult survivors, known only as Once Yellow Kate. Hope and Kate are both murky about the events leading up to the Yellow Massacre and must rely on each other’s perspectives to piece together the full story.

I particularly enjoyed the discussions between Hope and Kate comparing art and religion. As an artist, Hope interprets many of the occultist practices in terms of artforms, noting how both art and religion embrace symbolism. Moreover, both famous artists and religious leaders earn followers who fervently await their every word.

I also appreciated Gemma Amor’s incorporation of artwork throughout the book, which provides another dimension of disquiet as we try to grasp the true nature of Hope’s situation. All of the artwork in The Once Yellow House, including the cover, were made by the author herself.

Through her believable and somehow relatable characters, Gemma Amor explores themes of emotional abuse and the corruption of love. The unsettling elements of The Once Yellow House span a range of psychological and cosmic horror, as well as truly grotesque body horror. This book is definitely not for the squeamish.

The Once Yellow House also serves as Gemma Amor’s love letter to the color yellow. Yellow is the color of happiness, light, energy, and friendship, but also the color of caution, cowardice, and deceit. I enjoyed reading Hope’s musings on these multifaceted meanings of yellow in art. Hope is particularly attracted by Vincent van Gogh’s prolific use of yellow in his paintings, reflecting on how his choice of color scheme mirrored his evolving mental state.

Gemma Amor’s writing is perfect, as usual, with a keen attention to detail. As an upstate New York native, I was pleasantly surprised to see that she even used our correct telephone area code in the novel.

Gemma Amor is one of my favorite horror authors, and The Once Yellow House only reinforces that view. The Once Yellow House is both a brilliantly constructed puzzle and a first-rate work of art.

5/5

Read The Once Yellow House by Gemma AmorThe post REVIEW: The Once Yellow House by Gemma Amor appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

June 25, 2023

REVIEW: The Handyman Method by Nick Cutter and Andrew F. Sullivan

The Handyman Method is a wickedly brutal horror novel coauthored by Nick Cutter and Andrew F. Sullivan that provides a heinous twist on the classic haunted house theme while delivering equal doses of hilarity and horror.

As the novel opens, the young Saban family moves into a newly constructed home in an unfinished, isolated neighborhood. Despite being new, the house seems to be falling apart, starting with an enormous crack that Trent and Rita Saban discover in their walk-in closet. The crack itself is concerning, but not nearly as disturbing as what they find hidden inside.

As the novel opens, the young Saban family moves into a newly constructed home in an unfinished, isolated neighborhood. Despite being new, the house seems to be falling apart, starting with an enormous crack that Trent and Rita Saban discover in their walk-in closet. The crack itself is concerning, but not nearly as disturbing as what they find hidden inside.

To address these problems, Trent consults a series of YouTube videos by Handyman Hank. The YouTube star apparently has the solution to every problem, extending well beyond the domain of home repair.

But Hank also promotes old-fashioned toxic masculinity through subliminal messages that are readily absorbed by Trent. Handyman Hank becomes an increasingly nefarious figure as the book progresses, with his videos becoming more personalized for Trent’s specific situations. Before long, Trent is a pickup truck-driving, contractor card-carrying tough guy complaining to his disbelieving wife that she doesn’t understand how difficult it is to be a man.

The Handyman Method is a cutting satire of home improvement culture, featuring several side-splitting trips to Home Depot that highlight the one-upmanship of the Y chromosome crowd who compete to display the highest levels of testosterone-fueled manliness.

The Handyman Method is both a hilarious and horrifying read. I couldn’t stop laughing at the authors’ brutal takedown of Infowars-style toxic masculinity. At the same time, there are some truly excruciating scenes that made me wince in pain. This is the rare horror book that elicits genuine tears of both agony and laughter.

The collaboration between Nick Cutter and Andrew F. Sullivan is seamless. Their writing is ferociously funny and unrelentingly brutal. Cutter and Sullivan also give a unique spin on the classic haunted house trope, reaching a level of dread that I didn’t think possible. I was truly shocked by several of the plot twists, especially in relation to the house’s history.

The Handyman Method feels like an acid-tripping horror version of the classic sitcom Home Improvement. Overall, The Handyman Method is a riotous ride, delivering both a terrifying haunted house story and a biting satire of the male chauvinism that pervades home improvement culture.

5/5

Read The Handyman Method by Nick Cutter and Andrew F. SullivanThe post REVIEW: The Handyman Method by Nick Cutter and Andrew F. Sullivan appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

June 24, 2023

Review: The First Bright Thing by J.R. Dawson

A magical circus is traveling to an empty lot in the middle of a prairie in Iowa, where the prairie feels like literal magic next to rousing magicians. A freckled middle-aged woman wearing a bright red velvet coat commands Windy Van Hooten’s Circus of Fantasticals in 1920s America. She and her Sparks spin joy and romance for a crowd that will soon exit their tent for a dark world of wars to end all wars and insecure men who smile at pain. It’s George Méliès in a magical, romantic, dark world.

J.R. Dawson collects romantic tales of circus people and transforms them into misfits clasping for the love and respect missing from their lives. A glittering trapeze artist, a strongwoman, men in pinstripe threads, sapphics traveling through time, a circus king out for revenge, and grotesque illusions are shaped into this book set on a hot Iowan prairie.

J.R. Dawson collects romantic tales of circus people and transforms them into misfits clasping for the love and respect missing from their lives. A glittering trapeze artist, a strongwoman, men in pinstripe threads, sapphics traveling through time, a circus king out for revenge, and grotesque illusions are shaped into this book set on a hot Iowan prairie.

But Dawson also goes deeper: how the circus is not just a romantic escape but a path for those on the outskirts of society. Sparks, magicians with specific talents, walk in between the difficult choices the world presents. The First Bright Thing is about the choice to be as terrible as their abusers or to resist with pizazz. Rin’s circus of fantasticals name themselves misfits in more than one means–queer and defiantly happy. In Dawson’s The First Bright Thing, some Sparks time travel, others heal bullet wounds, and then there are those that incite violence in the slimiest of ways. Their society paints them as a threat, so much so that parents shove them to a sanitarium to be fixed–gay conversions immediately come to mind. At the opposite end of all the hate in The First Bright Thing stands Rin and her magical circus, performing illusions for people that want a little joy in their life. But a monster from her past haunts this new happy life–friends and lovers most of all.

The Circus King and his Midnight Illusionatories have arrived in the Midwest with nightmare tents of black and red. He cuts a cunning figure with a sharp face, a suave black coat, and a tophat of bloody red. His intentions are the opposite of Rin’s. Ownership. Manipulation. All-consuming power.

The First Bright Thing observes memory, dipping in between the past and present. It’s the story of Rin in the present and Edward, a young soldier given a second chance at life after dodging the horrors of the great war. Dawson vividly paints the horrendous realities of trauma, as with Edward peeling off his war-damaged jumpsuit like a skin he can’t quite escape from. Edward’s story is about how that jumpsuit never really leaves him. It even eats at his ability to feel human and to live in the world as a human. Because Edward discovers that he’s got a special ability. He can make people do horrible, disturbing things.

The First Bright Thing jumps into a straightforward novel of love, romance, and surviving abuse. Those that know the precise horrors that abuse entails also know it doesn’t just end with the escape but that building relationships afterward is an uphill battle of many horrors. Magic is power in Dawson’s world. Here, in a book of unflinching truths, are uncomfortable scenes of women wilting like flowers in the face of cold, demanding domesticity, taking their confidence down inch by inch until it feels as if they do not exist at all.

I used to go to the circus in Iowa many times with my parents, including the locations featured in this book. The prairie, the hardships of being queer in the Midwest, and the beautiful sounds of cicadas are all very familiar. The author’s descriptions of the setting did not always feel real. Dawson plays a bit into the stereotype that cities are queer utopias, effectively erasing the rural queer communities of my home.

The First Bright Thing is like falling into a tent of sharp costumes, trapeze artists, and cabinets of curiosities–both sour and sweet. It is not flawless, but it is a richness of layered narratives. If you ever want to spend a summer in a dark fantastical circus, enter J.R. Dawson’s The First Bright Thing.

Read The First Bright Thing by J.R. DawsonThe post Review: The First Bright Thing by J.R. Dawson appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.