Adrian Collins's Blog, page 7

September 21, 2025

REVIEW: Old Gods and Other Tales by Scott Oden

There is a breed of fantasy writer who, no matter how talented, haven’t received the attention they, and by extension their work, deserve. Writers like Paul Kearney, whose Monarchies of God series should’ve thrust him higher in the consciousness of fantasy writers, is one such author. Another is Michael Woodring Stover, whose Caine books, a skilful and thrilling blend of cyberpunk and high fantasy, came out twenty years ago, yet has managed to somehow undeservedly stay under the radar.

Add to the collection Scott Oden, an American author who burst on to the scene with a series of historical novels set in Ancient Greece and Egypt. Works like 2005s Men of Bronze and The Lion of Cairo married historical action with the best of the 1930s inspired pulp writings of authors such as Robert E. Howard.

Add to the collection Scott Oden, an American author who burst on to the scene with a series of historical novels set in Ancient Greece and Egypt. Works like 2005s Men of Bronze and The Lion of Cairo married historical action with the best of the 1930s inspired pulp writings of authors such as Robert E. Howard.

After The Doom of Odin, the last in a trilogy of Norse inspired historical fantasy, Oden released a collection of cosy fantasies, before returning to his original love, pulp infused historical sword and sorcery, in his latest collection, Old Gods and Other Tales.

In his introduction, Oden pays homage to his literary hero, Robert E. Howard. And reading the stories in Old Gods, Howard’s presence looms large. Like Howard, Oden makes fascinating use of historical settings. Like Howard, Oden’s lead characters are indomitable, facing great odds with a grim, unwavering purpose. And most importantly, like Howard, Oden knows how to write a propulsive, action packed story with vibrant characters who leap off the page as their story unfolds.

I’m a big fan of this collection. Oden has used a wide variety of historical locations – Elizabethan England (where, winningly, the protagonist is a playwright, who uses his intuitive understanding of narrative to overcome seemingly overwhelming occult odds), the Crusader Kingdoms, the Byzantine Empire and the time of Alexander – to tell an even wider variety of fantasy stories. My personal preferences lean more towards the action/heroic, so stories such as The Unburied (returning soldiers serving under Alexander the Great find their home village overrun by the spoilers) or The Purple Shroud(an assassin seeks the Imperial Byzantine throne) an excellent example of pulp story telling informed by history) found a very appreciative audience.

It says much about Oden’s skill as a writer that any of these stories (yes, even Three Tabbed Doom – no I won’t spoil it for you) could be spun out into a novel, or even a series of novels. What Oden has realised, just as Howard realised, that no matter how inventive an author might be in worldbuilding a fictional world, there is no beating the endless variety and indeed, strangeness, of our own history. Of fascination for Oden (and myself) is the history of the Crusader Kingdoms – those Christian realms carved out of Palestine by crusaders from the West in the 11th and 12th centuries. Here, Oden has found a thick vein of inspiration – the story The Lion of Montgisard features the famed Leper King, Baldwin, facing down a huge host of Moslems led by the famed Saladin.

Oden expertly weaves tales of high adventure out of historical backgrounds that are endlessly fantastical to the modern reader. The prose is often muscular and forthright, though Oden is no blood and thunder author. There is a modern sensibility to his writing, and he is certainly capable of writing from a female perspective in a confident manner. No matter how strange the setting, Oden crafts characters that are instantly recognisable – men and women of action, who do not shirk their duty, and even though they might die, do so with their honour intact.

I highly, and I mean highly, recommend Old Gods Old Gods and Other Tales. In many ways, Oden is heir to Howard – an author whose work is gripping, occasionally appealingly doom-laden, making expert use of history to infuse stories of high adventure with an added, addictive frisson. One hopes that with this collection, Oden begins to earn the attention he so richly deserves.

Read Old Gods Old Gods and Other Tales by Scott OdenThe post REVIEW: Old Gods and Other Tales by Scott Oden appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

September 20, 2025

REVIEW: Red Country by Joe Abercrombie

Best Served Cold took us to the revenge genre, The Heroes took us to war, and now Red Country takes us to the west. Rife with the fantastic character development and intense action that only Joe Abercrombie can deliver, Red Country adds grit, a rescue mission, wide, open terrains, brutal standoffs, prospectors, and the questions & struggles of individualism against the inevitable churning will of civilization. With blood on its knuckles and a keen look in its eyes, Red Country is a dream come true for fans of westerns and grimdarks.

“The trouble with running is wherever you run to, there you are.”

“The trouble with running is wherever you run to, there you are.”

We start off with Shy South and Lamb, a young woman and her step father, who return to their farm after visiting the town to find it burned to the ground, a friend hung, and Shy’s brother and sister kidnapped. The pair takes off in pursuit, where they come across cheating speculators, roving gangs, and desperate men doing desperate deeds.

The main strength of Red County—as expected in an Abercrombie novel—is the character development. Shy and Lamb are both fascinating characters who have their own buried pasts of violence, but as they race to save the kidnapped children, they have to dig up the tools and come face to face with who they truly are. There’s something so compelling about Abercrombie’s skill of bringing characters to live by showing them struggle to be better while denying what they are. The result of the clashing desires, dialogues, and decisions is a cast of rich, nuanced characters, and Red Country’s biggest success is its cast.

The side characters also burst off the page with nuance and firm humanity. There’s a lot of tropes at play in Red Country between the hard businesswoman, the scheming speculators, the desperate prospectors, the gang members, and so on, but they don’t feel like simple tropes. They fit into a role surely, but not in a way that feels stale.

One last character who deserves a shout out is Temple. Temple is a lawyer for one of the characters making a return to the page in Red Country, and Temple has about as good a time as a lawyer can have in an Abercrombie western fusion. He gets his shit rocked more than once, as well as bullied and underestimated frequently. He persists, growing a backbone as the story goes, and should be a favorite for fans of stories like Senlin Ascends.

From an action perspective, Red Country rivals The Heroes as Abercrombie’s best yet. Instead of the epic battles and widespread death and chaos in the previous novel, Red Country is almost intimate in its proximity to violence. The fights and duels are far more centered on one death at a time, and the result is a bone-crunching, close-up delight.

There’s a duel about halfway through Red Country which is still widely talked about to this day (and for good reason, it’s obscenely hype and one of the most memorable scenes in First Law), but there’s one scene in the first quarter of the book that lives rent free in my mind. Lamb embraces his old ways in a bar fight, and the build up, the dialogue, and the ending is perfection. In the best way, it’s eerily reminiscent in tone, setting, and rising tension of the Hound’s “chicken scene” from Game of Thrones.

“Evil turned out not to be a grand thing. Not sneering Emperors with their world-conquering designs. Not cackling demons plotting in the darkness beyond the world. It was small men with their small acts and their small reasons. It was selfishness and carelessness and waste. It was bad luck, incompetence, and stupidity. It was violence divorced from conscience or consequence. It was high ideals, even, and low methods.”

This is a western through and through, which means the pacing is slow, the violence can be random and unfair, and everyone is rugged and sweaty. Additionally, Abercrombie has stated that this was a hard novel to write, and you can feel it in instances. There are certain portions where the quality of the novel dips, particularly when Shy and Temple are the main characters on the page. At the end of the day, Red County is a divisive novel. While it’s my personal favorite of the standalones, an objective review would be incomplete without offering fair warning that it’s not for everyone.

For fans of the western genre though, Red Country is a delight. The reunion with some fan-favorites, the action, the dialogue, and the character building is wonderful, and the subversion of expectations of what it means to “ride into the sunset” is something I think about all the time. Red Country is a rugged, but marvelous, work, and I can’t recommend it enough for fans of the western genre.

Read Red Country by Joe AbercrombieThe post REVIEW: Red Country by Joe Abercrombie appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

September 19, 2025

REVIEW: The Savage Sword of Conan #6

Issue #6 of The Savage Sword of Conan features the conclusion of the lengthy King Conan comic “The Ensorcelled,” a short Conan story by Matthew John, and a new self-contained comic starring Dark Agnes de Chastillon.

Once again penned by Jason Aaron and illustrated by Geof Isherwood, the second half of “The Ensorcelled” takes up the lion’s share of the issue. When we last left King Conan, he was far from home, in Aquilonia’s neighboring kingdom of Brythunia. Despite taking a direct role in the capture of Xyleena, the infamous Witch of Graskaal, Conan finds himself disgusted by the way she was railroaded through a sham trial by his host, King Fabiano. Conan rescues the witch from her impending execution, a bold act that makes him an enemy of the ruthless witchfinders known as the Brethren of the Briar. Despite his distrust of sorcery, Conan throws in his lot with Xyleena, taking up arms against the hateful zealot Father Flail. He soon learns that the Brethren possess body-warping magic of their own, however. Spanning a combined length of 103 pages across two magazine issues, “The Ensorcelled” still feels a little on the long side—as a Savage Sword reader I would rather have multiple self-contained stories and leave serialized adventures to the monthly Conan the Barbarian title—but the second half is stronger than the first. It features some gnarly body horror, exciting combat, and an amusing epilogue. Geof Isherwood’s artwork impresses, and it’s clearly legible in monochrome, which can’t always be said for contributions by artists more accustomed to working in color. With their tangled, thorny masks Isherwood gives the Brethren of the Briar a cool and distinctive appearance, and he’s no slouch when it comes to rendering the gory bits of the tale as well.

Once again penned by Jason Aaron and illustrated by Geof Isherwood, the second half of “The Ensorcelled” takes up the lion’s share of the issue. When we last left King Conan, he was far from home, in Aquilonia’s neighboring kingdom of Brythunia. Despite taking a direct role in the capture of Xyleena, the infamous Witch of Graskaal, Conan finds himself disgusted by the way she was railroaded through a sham trial by his host, King Fabiano. Conan rescues the witch from her impending execution, a bold act that makes him an enemy of the ruthless witchfinders known as the Brethren of the Briar. Despite his distrust of sorcery, Conan throws in his lot with Xyleena, taking up arms against the hateful zealot Father Flail. He soon learns that the Brethren possess body-warping magic of their own, however. Spanning a combined length of 103 pages across two magazine issues, “The Ensorcelled” still feels a little on the long side—as a Savage Sword reader I would rather have multiple self-contained stories and leave serialized adventures to the monthly Conan the Barbarian title—but the second half is stronger than the first. It features some gnarly body horror, exciting combat, and an amusing epilogue. Geof Isherwood’s artwork impresses, and it’s clearly legible in monochrome, which can’t always be said for contributions by artists more accustomed to working in color. With their tangled, thorny masks Isherwood gives the Brethren of the Briar a cool and distinctive appearance, and he’s no slouch when it comes to rendering the gory bits of the tale as well.

Written by occasional Grimdark Magazine contributor Matthew John, “Madness on the Mound” is the first prose story to be included in The Savage Sword of Conan since issue #3’s excerpt from Conan and the Living Plague, published as part of John C. Hocking’s Conan: City of the Dead omnibus. This story takes place in the frozen north, shortly after Conan’s encounter with the demigoddess Atali, the Frost Giant’s Daughter (an episode recounted in Conan the Barbarian #15). Conan and the exhausted remnants of the Æsir war band led by Niord stop by an isolated village hoping for a brief respite. Conan is instantly on edge when he finds the hamlet left undefended, the bulk of the menfolk having left to search for a missing hunting party. A terrified boy rushes back to the village to report an attack by Vanir warriors, and Conan and his comrades set out to meet their foes. Instead of an enemy encampment, however, the men are confronted by a still-glowing fallen star. Fleshy roots have burst from the massive rock, and Conan soon discovers that the tendrils terminate in the bodies of the dead Vanir, wending through them and animating them like grotesque puppets. What follows is a bloody and grim little tale that emphasizes the horror aspect commonly found in Sword & Sorcery. It feels very much a companion to the creepy fantasy-horror stories collected by John in To Walk on Worlds and his contribution to Old Moon Quarterly, Vol. 7. The editing could have been a little tighter—“spore” is used when the word “spoor” is intended, and “below” instead of “bellow”—but John packs quite a bit of adventure in two short pages. John’s portrayal of Conan feels authentic, and supporting character Niord also has some good character moments.

The issue is rounded out by “The Head of St. Denis,” written by Michael Downs and illustrated by Piotr Kowalski. It focuses on 16th century French swordswoman Agnes de Chastillon. Dark Agnes hasn’t had the best track record in Titan Comics; a modified version of her origin story appeared in The Savage Sword of Conan #4 with the baffling choice of anime style artwork, and she also had a fairly unsatisfying role in the Conan the Barbarian: Battle of the Black Stone crossover event miniseries. This brief comic is almost a character study for Dark Agnes. Separated from her companion Etienne and pursued by enemies, she stumbles through a wooden marsh until she encounters an apparition of the decapitated martyr St. Denis of Paris. The episode feels a bit like a scene from a Hellboy comic (indeed, Kowalski’s artwork looks like a blend of Mike Mignola and woodcut prints) and not much happens beyond the reader getting a sense of Agnes’ fierce determination, but this is the best depiction the character has gotten in Titan Comics to date. I don’t envy modern day creators trying to work with Dark Agnes. She only appeared in two unpublished Robert E. Howard stories and a fragment, and there isn’t much substance to the character beyond “talented swordswoman who rejects patriarchy.” Maybe this episode will launch better stories for Dark Agnes in the future, but if the intent is to promote a Howardian heroine I think Conan’s former companions Valeria or Bêlit would make more interesting protagonists.

While it feels like creators continue to struggle with Dark Agnes and I would’ve preferred the page count be devoted to shorter standalone stories rather than sprawling multi-issue epics, The Savage Sword of Conan #6 marks a strong conclusion to the black and white magazine’s first year at Titan Comics. The artwork was excellent throughout and action scenes abundant. I appreciate seeing prose stories appear alongside the comics, and despite its impressive brevity Matthew John’s “Madness on the Mound” was the highlight of the issue.

Read The Savage Sword of Conan #6 by Jason Aaron (W), Geof Isherwood (A), Matthew John (W), Michael Downs (W), Piotr Kowalski (A) Read on Amazon

Read on AmazonThe post REVIEW: The Savage Sword of Conan #6 appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

September 18, 2025

REVIEW: The Will of the Many by James Islington

Ambitious & insightful, James Islington’s The Will of the Many is a dark academia book with a lot of heart and a lot of rage. Cutthroat characters, an intense setting, and a very cool magic system, The Will of the Many is the best school setting since Name of the Wind and threatens to be a classic series.

“There comes a point in every man’s life where he can rail against the unfairness of the world until he loses, or he can do his best in it. Remain a victim, or become a survivor.”

“There comes a point in every man’s life where he can rail against the unfairness of the world until he loses, or he can do his best in it. Remain a victim, or become a survivor.”

The primary plot of the novel is about Vis, our main character who is an ousted prince of one of the empire’s takeovers, and the mission his adoptive father gives him. He’s to go to the country’s most prestigious school and pretend to be one of them, but really he’s there to investigate the murder of his adoptive father’s brother. To do that, he’ll need to rise in the ranks of the school and secure allies, but he can never let the mask slip.

The Will of the Many takes place in a setting where people participate in pyramid structures of “will ceding”, a system where lower ranked people give their “will” to people above them. It comes with numerous physical benefits to those who receive their payments, but it places a large strain on the population and a critical vulnerability on the society.

What I find most delightful about The Will of the Many is the sheer ambition that Islington has in telling this. Topics range from colonialism, capitalism, ambition, loyalty, nepotism, utilitarianism, and revenge. Islington covers these with a deft, natural touch, never outright preaching but instead showing and having honest dialogues. If a weaker author had tried this, it would have fallen flat on its face. Instead, The Will of the Many is a book that delivers on its promise of having a lot to say.

Another thing that I love from The Will of the Many is that every single character in the novel has agency, and none more so than Vis. Vis is a fantastic protagonist: a bitter past, well-defined traits, and a moral complexity. He’s angry at the world and the empire, he’s carrying scars, and he’s trying to do the right thing despite it all. As mentioned, the side characters have their own goals, moral lines, and plans as well. In a society as cutthroat as the one Islington has made, these characters frequently backstab—or demand Vis to backstab—each other. The tension is palpable throughout the entire length of the novel and the pages fly by, but what I found most impressive is just how real everyone felt. When one character fucks over another, you understand why. There’s a certain moral grayness that colors the world and makes you question whether the characters are vicious because of the setting or if it’s simply their nature.

The school setting is both familiar and unique. We see a lot of the expected tropes like the pedantic/aggressive teacher, the bullies, the cliques, the misunderstood victim, the training montages, the love interest, so on and so on. Despite that, there’s a breath of fresh air in the novel. Maybe it’s just Islington’s talent—combined with a few absolutely great and gut-wrenching expectation subversions—but the tropes in The Will of the Many just work in an excellent way.

Islington’s prose and dialogue are significantly improved from his earlier works. The Will of the Many was a book I was clearing through hundreds of pages at a time, and that’s because Islington’s prose is clean and Vis’ discussions sing.

Finally, I have to shout out the ending. It’s batshit insane and if I had the sequel in-front of me upon finishing I would have dove right into it. Islington’s greatest strength used to be his plotting, and assuming that skill hasn’t diminished since Licanius, this series is going to be bonkers in the best way.

“They know the system is wrong, but they choose not to think or speak up or act because they ultimately hope that in their silence, they will gain. Or at the very least not have to give more than they have already given.”

Honestly, I don’t really have any complaints about this book, but I do have a few warnings. If you’re someone who doesn’t like school settings, this is not the book for you. If you’re someone who doesn’t like training montages, this is not the book for you. If you’re someone who doesn’t like philosophizing in their stories, this is not the book for you.

However, if you’re someone who does like school settings, someone who wants a cutthroat society with a lot of twists, someone who wants to go into deeper themes of life, then pick up The Will of the Many.

Read The Will of the Many by James IslingtonThe post REVIEW: The Will of the Many by James Islington appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

September 17, 2025

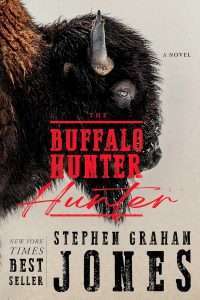

REVIEW: The Buffalo Hunter Hunter by Stephen Graham Jones

As The Buffalo Hunter Hunter begins, Etsy Beaucarne is struggling with an undistinguished academic career. A surprising opportunity falls in her lap, however, after a distant relative’s crumbling journal is discovered hidden in the walls of a decrepit parsonage. Penned in 1912 by her great-great-grandfather Arthur, a Lutheran pastor posted in Montana, Etsy hopes to use the manuscript as the springboard for a new research project, ideally leading to publications and tenure. But as transcriptions of the brittle and faded pages are delivered, she discovers a much darker and more troubling narrative than expected.

The premise established, Etsy’s story fades into the background. The Beaucarne Manuscript makes up the bulk of The Buffalo Hunter Hunter. Arthur Beaucarne’s religious ministrations to the small town of Miles City are disrupted when an ominous stranger begins attending his sermons. Invariably seated in the rearmost pew, the visitor is a Native American man dressed incongruously in a black Jesuit robe, battered cavalry boots, and dark glasses. Disturbed by the man’s intense scrutiny, Arthur nevertheless finds himself fascinated by the visitor. Eventually the Indian approaches Arthur after a Sunday service, introducing himself as Good Stab of the Pikuni (Piegan Blackfeet tribe), and says that he has come to the church to confess his sins. Over a series of weekly visits—the chapel dimmed so as not to aggravate his unusual sensitivity to light—Good Stab unburdens his soul, and Arthur dutifully recounts the man’s anecdotes in his journal.

The premise established, Etsy’s story fades into the background. The Beaucarne Manuscript makes up the bulk of The Buffalo Hunter Hunter. Arthur Beaucarne’s religious ministrations to the small town of Miles City are disrupted when an ominous stranger begins attending his sermons. Invariably seated in the rearmost pew, the visitor is a Native American man dressed incongruously in a black Jesuit robe, battered cavalry boots, and dark glasses. Disturbed by the man’s intense scrutiny, Arthur nevertheless finds himself fascinated by the visitor. Eventually the Indian approaches Arthur after a Sunday service, introducing himself as Good Stab of the Pikuni (Piegan Blackfeet tribe), and says that he has come to the church to confess his sins. Over a series of weekly visits—the chapel dimmed so as not to aggravate his unusual sensitivity to light—Good Stab unburdens his soul, and Arthur dutifully recounts the man’s anecdotes in his journal.

During his first visit, Good Stab describes encountering the scene of a bizarre massacre, with dead white men surrounding a wagon containing a caged and hissing chalk-white man with fangs. After a series of catastrophes, the so-called “Cat Man” escapes from his prison and Good Stab undergoes a traumatic metamorphosis.

Between Good Stab’s visits, mutilated and exsanguinated human bodies begin appearing outside Miles City, partially skinned in apparent imitation of the wasteful fashion of white hunters of buffalo. Arthur quickly draws a connection between the corpses and his unusual guest and begins to investigate. Over time he begins to suspect an ulterior motive underlying Good Stab’s visits.

As it makes clear surprisingly early on, this book is a vampire novel. The Buffalo Hunter Hunter shares some superficial elements with Anne Rice’s 1976 Interview with the Vampire, and fans of the latter are likely to enjoy Stephen Graham Jones’ novel. But it’s also simultaneously a compelling revenge tale that deals unflinchingly with the Native Americans’ genocide at the hands of white colonizers. Rage, guilt, and regret feature prominently, and Good Stab’s anguish is powerfully rendered. Jones is himself of Blackfeet heritage, and it felt like the historical setting gave the author license to write about his ancestors’ plight in a more unfiltered and immediate way than his works set in the modern day.

Literary weightiness aside, The Buffalo Hunter Hunter is a particularly original vampire story. The Old West setting is fresh, as is the fact that—in Jones’ world—vampires literally are what they eat. Vampires begin to take on characteristics of the creatures they habitually consume. Too much deer blood and stubby antlers begin to sprout, for example. The same principle extends to human prey; when Good Stab subsists on white victims, he grows to resemble them, gaining a pale skin tone and scraggly beard. If he is to maintain his original form, he’s forced to devour his own people. It could be argued that this is a metaphor for cultural assimilation: associate too much with the white man and Good Stab begins to become one, but isolating himself among his fellow Pikuni is likewise harmful and unsustainable in the long term.

Beyond this novel depiction of vampirism, the book also boasts an abundance of chilling moments. With unlimited time at their disposal, The Buffalo Hunter Hunter repeatedly demonstrates that a sufficiently patient and motivated vampire can concoct tortures of breathtaking malice. Fates literally worse than death.

The Buffalo Hunter Hunter benefits from the strong and distinct voices of its two primary narrators, Good Stab and Arthur Beaucarne. Both are unreliable narrators in their own way. Good Stab is fond of using colorfully literal translations of his people’s words for animals (big mouth, blackhorn, real-bear, prairie-runner, etc.), but he occasionally slips and betrays a more fluent command of American English than the disarming Indian stereotype he playacts as. Arthur, on the other hand, reveals a tendency to dance around sensitive topics, to avoid examining or grappling with the uncomfortable until it’s too late.

Unfortunately, the robust characterization on display with Good Stab and Arthur ends up making the novel’s primary flaw more visible. When the Beaucarne Manuscript concludes, the narrative returns to the present day, with Etsy left to deal with her great-great-grandfather’s disturbing legacy. But because readers have spent so little time with Etsy, she feels much less satisfying as a viewpoint character. Good Stab and Arthur’s words are given heft by a lightly archaic style and the weight of history, while Etsy is just a modern gal with modern job frustrations and a cute cat. Relatable, but underequipped for the task of carrying such a heavy story’s ending. Perhaps this issue could have been ameliorated by having Etsy resurface periodically during the middle portion of the book to share her reactions and own investigative footwork, rather than showing up for a few brief pages in the beginning and then reappearing only to shoulder the last tenth of the book. The violence depicted in the finale also felt tonally different than what readers had been presented with previously. Less gritty, more gonzo.

Despite the comparatively weak finish, The Buffalo Hunter Hunter remains the most original and exciting vampire novel in years. Stephen Graham Jones has released many strong books in a short span of time, but this one is particularly passionate and multidimensional. While I suspect Jones’ best work is still ahead of him, The Buffalo Hunter Hunter stands out even among an already robust catalog of work.

Read The Buffalo Hunter Hunter by Stephen Graham JonesThe post REVIEW: The Buffalo Hunter Hunter by Stephen Graham Jones appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

September 16, 2025

REVIEW: Molten Flux by Jonathan Weiss

Molten Flux by Jonathan Weiss, the opening chapter in his Flux Catastrophe series, is a high-octane thrill ride full of grit, violence and some truly mind-bending worldbuilding. Think Mad Max and Red Faction with magic.

We follow Ryza, a young man whose wandering trade caravan is captured at the novel’s opening by smelters, death-dealers of a different kind. His hands are cuffed, his life is forfeit and about his neck an explosive collar is strapped. And just like that, one of the most exhilarating science-fantasy novels of modern times begins.

We follow Ryza, a young man whose wandering trade caravan is captured at the novel’s opening by smelters, death-dealers of a different kind. His hands are cuffed, his life is forfeit and about his neck an explosive collar is strapped. And just like that, one of the most exhilarating science-fantasy novels of modern times begins.

Weiss wastes no time in this novel, throwing the reader headfirst into events. With quick, succinct explanations, Weiss is able to reveal the world and magic in vivid ways. As is true of all good worldbuilding, the novel hints at greater depths but never burdens the reader with their explanation. Weiss’ worldbuilding is full of smoke and mirrors and rusty guns. It is deep but never overbearing; there is a glossary at the back of the book, but Weiss’ descriptions and depictions of magic and the world are always enough. This is a world with mist at its edges and rust in its heart.

The story takes place in a world known only as The Droughtlands. Imagine sprawling, unending deserts, sporadically populated with human settlements constructed from refuse and debris. It is a truly fallen world. A post-post-apocalyptic one. Among the debris, people scrounge for survival and dominance.

And for molten flux.

A self-replicating liquid metal, molten flux can be injected into corpses (known as Autominds) to be reanimated and controlled by Kretatics (those capable of metal magic). Despite the punishments for possession of even a drop of the lethal liquid, there is a roaring trade across the Droughtlands and it is over this precious and deadly commodity that the novel’s central conflicts are fought.

A large portion of the novel takes place upon Revance: a colossal, walking fortress composed of scrap metal and held together and controlled by magic unseen. Think Howl’s Moving Castle but more rusty, dilapidated and with a gargantuan cannon strapped to it. It is a hulking beast of a fortress whose purpose and ownership is unknown. It simply roams from city to city, endlessly. Within Revance live hundreds of conscripts of various factions whose duty it is to search for scrap metal to add to its composition. It is part cargo hauler and part mercenary outfit, and at the novel’s outset, there is tension brewing on-board and mutiny is in the air.

At the oil-slicked heart of this novel are the characters. Weiss presents us with a rag-tag band of conscripts on-board Revance who feel honest, deep and real. He has spent time considering their beliefs and opinions, and each of these differences plays out on the page.

Although Molten Flux is often compared to Mad Max, I felt that when it came to characters, Point Break came closest. The relationship between Ryza and some of his enemies reminded me of Keanu’s Johnny Utah and Swayze’s Bodhi: in another life, in another world, they would’ve been the greatest of friends, but here, in the Droughtlands, their beliefs and actions have sent them down irreversible paths. So often the chasms between the characters are unaddressed flaws within themselves. This tension between the characters is tight, biting and above all, realistic, and creates a complex web of interactions.

Chief among my praises for Molten Flux, however, is Weiss’ sheer originality. Sure we’ve had walking castles and scrambles in the desert over precious resources. But never like this. Weiss approaches every obstacle and conflict with a methodical mind and applies his originality to everything he touches. The high-energy is maintained throughout the novel, and the stakes are always clear.

A central theme of the story is the value of human life, and how humans can be reduced to little more than machines; a topic Weiss has further expanded upon in his discussions around social media.

I can’t think of many weaknesses or holes in the plot. I enjoyed this book so much, even the only lingering question I have—how do people survive in such a water-scarce world?—I am choosing to overlook.

Molten Flux blends the raw energy of Mad Max, the tension of Point Break, while sprinkling in shades of Red Faction.

Genuinely one of the most original pieces of fiction I have ever read, Molten Flux perfectly marries science fiction with fantasy. The novel presents over-the-top concepts with such believability I only hope the popularity of this series grows and finds a wider audience. If you are looking for a high-energy, brutal and original bit of fiction, there are few better places to start than The Droughtlands.

Read Molten Flux by Jonathan WeissThe post REVIEW: Molten Flux by Jonathan Weiss appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

September 15, 2025

Emmy Award Winning Grimdark

Everyone loves a good award don’t they? The awards shows might be as boring as watching paint dry but the Emmys did at least recognise some of the great grimdark TV series brought to our screen over the last year. So let’s dive into some over the big winners of the awards night (or should that be nights? They are pretty bloated, aren’t they?) and see which of our faves went home with a trophy or two.

The Penguin Matte Reeves spin off tale from The Batman was pretty brilliant. Starring Colin Farrell as the titular mobster in amazing heavy make-up, the series was dark and brutal and one of the best dark comic TV series to ever hit our screens. The series was nominated for four of the main awards and took home one – a deserving win for Cristin Milioti as lead actress in a limited series for her take on Sofia Falcone. Hopefully this means The Penguin may return to the small screen following the upcoming The Batman Part 2.

Matte Reeves spin off tale from The Batman was pretty brilliant. Starring Colin Farrell as the titular mobster in amazing heavy make-up, the series was dark and brutal and one of the best dark comic TV series to ever hit our screens. The series was nominated for four of the main awards and took home one – a deserving win for Cristin Milioti as lead actress in a limited series for her take on Sofia Falcone. Hopefully this means The Penguin may return to the small screen following the upcoming The Batman Part 2.

I don’t have many words left to tell people who incredible Andor is. It doesn’t matter if you lie Star Wars or not, the series is one of the best things to have ever hit the screen and that isn’t an exaggeration in any way. The music, the writing, the acting, directing, everything about this show was just perfection. It gave us two of the best screen speeches I have ever witnessed and showed the potential of the grittier side of the Star Wars world. If, for some unknown reason, you haven’t seen this show – sort it out. You’re missing out on greatness. Whilst it missed out wins after nominations for Best Drama and Best Directing, it did win Best Writing in a Drama for the episode Welcome to the Rebellion. It took home some more creative Emmy awards but definitely deserved more.

I don’t have many words left to tell people who incredible Andor is. It doesn’t matter if you lie Star Wars or not, the series is one of the best things to have ever hit the screen and that isn’t an exaggeration in any way. The music, the writing, the acting, directing, everything about this show was just perfection. It gave us two of the best screen speeches I have ever witnessed and showed the potential of the grittier side of the Star Wars world. If, for some unknown reason, you haven’t seen this show – sort it out. You’re missing out on greatness. Whilst it missed out wins after nominations for Best Drama and Best Directing, it did win Best Writing in a Drama for the episode Welcome to the Rebellion. It took home some more creative Emmy awards but definitely deserved more.

Arcane is loved here at Grimdark Magazine. The second season won four Emmys including Outstanding Animated Program. The Netflix animated series seemed to come out of nowhere and blow us away with its story based on characters from the League of Legends game. The story followed the origin story of sisters Vi and Powder as they are separated and brought back together by a conflict between the city of Piltover and the oppressed undercity of Zaun. With eight Emmys won overall for the two seasons, I’m sure it won’t be long before we dive back into the mesmerising world of Arcane.

Arcane is loved here at Grimdark Magazine. The second season won four Emmys including Outstanding Animated Program. The Netflix animated series seemed to come out of nowhere and blow us away with its story based on characters from the League of Legends game. The story followed the origin story of sisters Vi and Powder as they are separated and brought back together by a conflict between the city of Piltover and the oppressed undercity of Zaun. With eight Emmys won overall for the two seasons, I’m sure it won’t be long before we dive back into the mesmerising world of Arcane.

The second season of the apocalyptic hit series based on the award-winning game was nominated for sixteen Emmys, winning just the one. This is down from the first season which was nominated for twenty-four awards and won eight. Still, this is further proof of the growing recognition of grimdark tales during award season and something that definitely needs to be celebrated.

The second season of the apocalyptic hit series based on the award-winning game was nominated for sixteen Emmys, winning just the one. This is down from the first season which was nominated for twenty-four awards and won eight. Still, this is further proof of the growing recognition of grimdark tales during award season and something that definitely needs to be celebrated.

What is to come? With the amazing TV series and films released recently and with more to come, I’m sure there will be many more awards to come for the work that sits in the darker realms of our screens. I can’t wait to see what is next!

The post Emmy Award Winning Grimdark appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

September 14, 2025

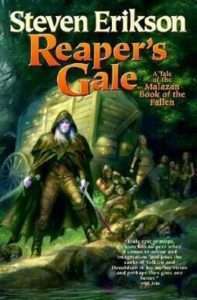

REVIEW: Reaper’s Gale by Steven Erikson

A rich tide of convergence, Reaper’s Gale is one of the most action packed, heart-breaking, and metal books in Steven Erikson’s Malazan: Book of the Fallen. Featuring new characters and old locations, Erikson’s plot surges forward and the armies march steadily to the end.

“We left a debt in blood,’ she said, baring her teeth. ‘Malazan blood. And it seems they will not let that stand.’

“We left a debt in blood,’ she said, baring her teeth. ‘Malazan blood. And it seems they will not let that stand.’

They are here. On this shore.

The Malazans are on our shore.”

Reaper’s Gale is where the series becomes married. Previously, we had essentially three different chains with Gardens & Memories, Deadhouse & House of Chains, and the seemingly separate Midnight Tides. Bonehunters brought together the first two entities, and Reaper’s Gale is the book that unites all of them, complete with bringing in more Malazan marines, more meddling gods, and a new major character in Redmask: an exile guarded by two K’Chain Che’Malle leading the clans to war against Letheras.

As with any Malazan novel, Erikson is juggling at tens of plot threads and hundreds of characters. Reaper’s Gale is no different, although the arcs generally center on what’s going on in Letheras. There’s wars coming from both the Malazan marines and Redmask’s Awl rebellion; there’s Rhulad—the immortal emperor—taking on any and all challengers in a manic/suicidal frenzy; there’s gods watching it all and putting their fingers on the scale.

Reaper’s Gale is bursting with action. Knives in the dark, mages wielding catastrophic magic, and soldiers carrying spears fill these pages. Most of the time it’s intense and keeps you on your toes, especially since Erikson keeps a steady introduction of new characters and isn’t afraid to kill the old. There’s room to kill off so many characters that the fear of losing one you care about keeps you reading every word.

The dialogue in Reaper’s Gale is hard to capture. At times, it’s his best, and at others it’s his worst. While the wittiest character in the series isn’t quite as prominent as in a separate book, their presence is still felt and every page featuring them is a blessing. The Malazan marines are as entertaining and philosophical as ever, but some of the other discussions from characters fell flat for me.

From a prose perspective, Reaper’s Gale is as gorgeous as Erikson’s other works. At this point the reader should know what to expect, and he doesn’t let them down. There’s some evocative language and questions here, particularly on themes of colonialism and war.

I’d argue this is Erikson’s most mysterious book. Reaper’s Gale has an iron grip on plot threads with massive implications, but he never fully dispels the mystery. A few are solved by the end of the novel, but the larger questions and conspiracies are still at play, with the full information being played close to the chest by Erikson and his characters alike.

One character deserves a special shout out. They can’t be named, but those who have read the book know exactly who I’m talking about. Erikson’s skill at bringing characters to life—despite the huge size of the cast—is shown off in a dazzling way in Reaper’s Gale. This character is brought to highs rarely seen in fantasy, and the climax of the story makes him an unforgettable fan favorite.

I’d be remiss if I wrote this review without mentioning that my favorite poem comes from this book. I’m not well versed in poetry, but that one is a poem I think of often, even if it does not think of me.

“Never mind the truth. The past is what I say it is. That is the freedom of teaching the ignorant.”

Unfortunately, Reaper’s Gale is Erikson’s most frustrating novel. It’s got some of his highest highs and lowest lows. There’s a ton to love in this book, but we spend a fair number of hours on plot threads and characters that simply don’t work as well as others. If this book were reduced to 800 or 900 pages it’d be one of the greatest in the series. Instead, Erikson makes us focus on plot threads that don’t have as fulfilling as a resolution as others, or characters who don’t leap off the page like others.

Still, Reaper’s Gale is a great novel. There’s some filler and some parts don’t work as well as others, but there is so much to love about this heartbreaking novel. Frustrations included, Reaper’s Gale is one of my personal favorites from the series, and if you’re someone who’s read The Bonehunters and are hesitant to continue, I implore you to. Erikson gives you a sneak peek into the heights this series is going to hit, and it hurts and delights in just the right way.

Read Reaper’s Gale by Steven EriksonThe post REVIEW: Reaper’s Gale by Steven Erikson appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

September 13, 2025

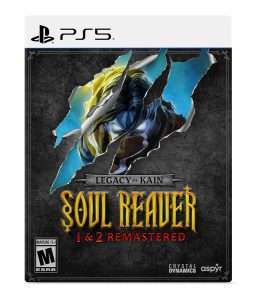

REVIEW: Legacy of Kain Soul Reaver 1&2 Remastered Edition

In 1996, Crystal Dynamics released a game called Blood Omen: Legacy of Kain for the original PlayStation. This introduced us to the dark, gothic world of Nosgoth, in which a murdered nobleman, the titular Kain, is raised as a vampire and given a chance at revenge. This premise turns out to be but a prologue for an epic journey in which Kain discovers the entire world has been exposed to terrible corruption which can only be purified if he will kill the guardians of the Pillars of Nosgoth. Kain begins a blood-drenched journey in which he gradually comes to think of his vampiric curse as more of a gift, and himself as a god.

This game was followed by the release of Soul Reaver: Legacy of Kain (1999) and Soul Reaver 2 (2001), which pick up thousands of years later. “Kain is deified,” Raziel tells us, and has raised other vampires in his eternal, corrupt empire. Soul Reaver opens with Kain betraying his most-trusted lieutenant, Raziel, casting him into an abyss. Raziel does not die, however, but is transformed into an indestructible wraith. After centuries of agony, he is greeted by the Elder God, who calls vampires abominations who disrupt the Wheel of Fate. He tells Raziel to become his “soul reaver” and avenge himself on Kain. All of this is prelude to a much deeper mystery Raziel finds himself embroiled in, with many forces trying to control his destiny.

This game was followed by the release of Soul Reaver: Legacy of Kain (1999) and Soul Reaver 2 (2001), which pick up thousands of years later. “Kain is deified,” Raziel tells us, and has raised other vampires in his eternal, corrupt empire. Soul Reaver opens with Kain betraying his most-trusted lieutenant, Raziel, casting him into an abyss. Raziel does not die, however, but is transformed into an indestructible wraith. After centuries of agony, he is greeted by the Elder God, who calls vampires abominations who disrupt the Wheel of Fate. He tells Raziel to become his “soul reaver” and avenge himself on Kain. All of this is prelude to a much deeper mystery Raziel finds himself embroiled in, with many forces trying to control his destiny.

The Legacy of Kain series as a whole has some of the finest storytelling I’ve ever experienced (in any format, not just games), and had a tremendous impact on my writing—on the stories I wanted to tell and how I wanted to tell them. Anyone familiar with both the games and my work will no doubt spot the homages scattered throughout.

In fact, the story, setting, and voice acting are so pitch perfect I’m still in awe of them after more than twenty years. Amy Henning, the director of many of the games, became one of my writing heroes. Simon Templeman, the voice actor for Kain, is so stunning in his delivery I cannot imagine anyone else filling the role. His interactions with Michael Bell (Raziel) have a Shakespearean grandeur to them.

After the partial conclusion of 2003’s Legacy of Kain: Defiance, no more games manifested. I held out hope of further games, but with each passing year, that hope dwindled a little more. Then, in 2024, a Kickstarter was announced for a prequel comic book.

Instant backer, here.

As many had hoped and speculated, the Kickstarter tested the waters for the announcement of a remaster, in this case of Soul Reaver 1&2. The remaster improved the graphics and made some minor quality of life upgrades, as remasters do, while leaving the games otherwise the same.

These remasters were released in December of 2024, but I couldn’t play right away as I was abroad. The chance to play these again, to experience the story again, had me ridiculously excited, and they were the first games I got to when I could.

Buy Legacy of Kain Soul Reaver 1&2 Remastered EditionThe post REVIEW: Legacy of Kain Soul Reaver 1&2 Remastered Edition appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

September 12, 2025

REVIEW: Pearl by Tim Waggoner

Ti West first imagined Pearl in his A24 film of the same name as a sympathetic yet brutal female antagonist battling against isolation and madness on her parents’ farm. Now, she’s been transcribed from screen to page in Pearl by Tim Waggoner. Waggoner is no stranger to TV and film adaptations with several notable series under his belt, including Terrifier and Alien. He has a knack for putting us inside the characters’ heads, and his books work well beside their visual counterparts rather than against them. Pearl, already a complex, character-driven thriller, is more devastating than we could have imagined as we get an inside look into Pearl’s descent into psychopathy.

Pearl is a twisted take on the femme fatale story, but rather than getting her way through seduction and manipulation, Pearl uses more direct approaches like, well, murder. Pearl is a young woman from the middle-of-nowhere East Texas — seriously, the town isn’t even given a name — with big dreams of becoming a movie star. However, she faces several obstacles, including a global pandemic, World War 1, an absent husband, a severely sick father, and an emotionally neglectful mother.

Pearl is a twisted take on the femme fatale story, but rather than getting her way through seduction and manipulation, Pearl uses more direct approaches like, well, murder. Pearl is a young woman from the middle-of-nowhere East Texas — seriously, the town isn’t even given a name — with big dreams of becoming a movie star. However, she faces several obstacles, including a global pandemic, World War 1, an absent husband, a severely sick father, and an emotionally neglectful mother.

“Pearl lifted her head and looked into Mama’s eyes, making sure to maintain the contrite expression on her face. She wished she could hear the orchestra one more time, but Mama had killed the music—just like she always did.”

Her hunger for stardom and desperation to leave her bleak situation eventually led to her madness overwhelming her and going on a murder spree. As someone who is from one of these

middle-of-nowhere towns in East Texas, Pearl’s plight may resonate with me a little more than the average person, murderous intent aside.

In all seriousness, Waggoner truly captures the inner monologue of a character like Pearl, who does violent and terrible things, and it is expressed in such a way that you almost catch yourself feeling bad for her. Waggoner takes the time to get the reader somewhat comfortable with Pearl before she crosses the point of no return. We see her goals, her dreams, her pain, her love, and her desire for acceptance. We see her as a woman repressed and forced to deny her baser instincts.

“One day you’ll understand that getting what you want isn’t important. Making the most of what you have is.”

A big part of this is due to the tension that is built up in Pearl through Pearl’s increasingly disturbing thoughts, questionable actions, and worsening hallucinations. Pearl becomes less human as the novella progresses, so rather than humanizing the monster, we see how the human becomes the monster.

“It was too bad the sheep had to die, but sacrifices need to be made to bring new life into the world. Every mother knew that.”

Waggoner explores the classic question of Nature VS Nurture, as we know how the madness already within Pearl festers and grows as she loses her sanity and fights for freedom from her sad life and entrapment on the family farm.

Her relationship with her mother, in particular, is a significant point of contentment as the distance between them widens the more confident Pearl becomes in herself. Pearl is the female hysteria trope in literature, but if you gave the woman from The Yellow Wallpaper a pitchfork and anger issues.

“They will notice eventually, and they will be frightened. Just as I am.”

Pearl’s world is no doubt bleak, but the central conflict in the novella stems from such an internal battle that I would not classify the novel as grimdark. It leans heavily into the psychological thriller/horror genres, but man, was it such a fun ride. I also went into this having watched all three movies several times; Pearl has a special place in my heart, so I can’t say if the novella stands by itself as such a knock-out success. I will say Mia Goth’s heart wrenching monologue at the very end did not translate as effectively onto the page, but that speaks more to her abilities as an actress than to Waggoner’s writing abilities. Pearl is one of the few female slashers we have, and I can’t wait to read the following two books in the series to see Waggoner work his magic yet again.

Read Pearl by Tim WaggonerThe post REVIEW: Pearl by Tim Waggoner appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.