Adrian Collins's Blog, page 116

November 22, 2022

Review: The Golden Enclaves by Naomi Novik

The Golden Enclaves and the entire Scholomance series have been a long dark road full of twists and turns. What started as a run-of-the-mill dark academia story pushed and expanded past the bounds of the genre and became a gripping grimdark story with a morally gray heroine that you may not like, but you can certainly get behind. Because while the story has solid side characters, especially in The Golden Enclaves, the journey is that of Galadriel, or El as she likes to be called. El, could be a dark sorcerous who can make mountains bow before her, and all mothers of the world cry out in weeping anguish. To quote the original Galadriel, “Instead of a Dark Lord, you would have a queen, not dark but beautiful and terrible as the dawn! Tempestuous as the sea, and stronger than the foundations of the Earth! All shall love me and despair!”

That is, if she chooses to go down that path, which is the crux of the story and her nagging fear.

That is, if she chooses to go down that path, which is the crux of the story and her nagging fear.

The Golden Enclaves starts out just as we left off, with El and company having fought a host of maleficaria hell-bent on their destruction. El released her power and a spell that could crack the Earth if she chose to. Instead, it split the Scholomance dimension off this plane, and hopefully all the demons with it. Did it work? As the book blurb can attest, sorta. “Ha, only joking! Actually it’s gone all wrong. Someone else has picked up the project of destroying enclaves in my stead, and probably everyone we saved is about to get killed in the brewing enclave war on the horizon. And the first thing I’ve got to do now, having miraculously got out of the Scholomance, is turn straight around and find a way back in.”

El is out of the immediate danger of Scholomance but has been thrust into an entirely different sort of danger, that of intrigue and guile. As she puts it, “my own personal trolly problem to solve.” This is where her friends and supporting characters truly shine. El might be unimaginably powerful, but she sucks when it comes to people. She has had to have a wall of outright unapproachability to protect others. “My anger’s a bad guest, my mother likes to say: comes without warning and stays a long time.”

Her having to play nice with the different enclaves to achieve a single goal is very new. And this is where Liesel, of all people, steps in. We met Liesel in earlier books. Liesel is a social climber and so practical in her approach to things it skirts being robotic. She sees angles in everything and, in her blatant practicality, is immune to all of El’s “charms.” Because only the outcome matters, she is the embodiment of all El has hated her entire life. But El discovers that while Liesel’s nature is of brutal practicality is offputting; she has developed it to survive, much like El has developed her cantankerous shell. As much as El hates it, they have a lot of similarities. The first and foremost is surviving Enclave life.

Plotwise, The Golden Enclaves is not the type of book one can talk about without ruining it. But I can tell you that The Golden Enclaves soars to the finale. It is a mile-a-minute story where every page is revelatory, and things can and do change from chapter to chapter. Instead of crashing at the end of this series as many authors do, their stories spent and the characters tired, Novik’s soars and rages. Her characters do not go gently into that goodnight.

I loved The Golden Enclaves and am so glad I took the journey through Scholomance with Novik. It was a hell of a ride.

READ THE GOLDEN ENCLAVES BY NAOMI NOVIKThe post Review: The Golden Enclaves by Naomi Novik appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

A Future Without Fiction: Dragons and Book Bans by Jason Pargin

I don’t want to be an alarmist and imply that the United States is on the verge of a Fahrenheit 451 scenario. If a candidate ran for president on a book-burning platform, they’d likely lose by, I don’t know, five or six points? It would depend on how the economy is doing, I suppose. But I do worry that a hundred years from now, you’ll find a society in which truly free expression barely exists. To explain why, I need to take us back to the invention of the dragon.

Now let me hit you with a sci-fi thought experiment: If aliens came to earth, would they find it strange that we did that? Would they think the whole concept of fantastic stories, of transmitting accounts of events that could never actually occur, was just an evolutionary glitch?*

Now let me hit you with a sci-fi thought experiment: If aliens came to earth, would they find it strange that we did that? Would they think the whole concept of fantastic stories, of transmitting accounts of events that could never actually occur, was just an evolutionary glitch?*

After all, it would actually be hard for the average person to explain to the alien what practical purpose these stories serve. We might say that heroic tales of space and magic inspire us to be great, but why would a fake story of heroism do that? What’s the benefit of asking a child to imagine themselves as a knight slaying a dragon — a job that no longer exists and an animal that never existed — instead of encouraging them to imagine life as a meticulous bricklayer? If your answer is that this would be extremely boring for the child, then the alien’s next question is obvious: “Don’t they only consider real life tedious because they compare it to your impossible tales?”

The justification we’d land on, I think, is that stories persisted as a way to convey important cultural norms in a format that sticks in the mind. It’s boring for a kid to remember which berries are poison, but package it as a harrowing folk tale of how touching deadly nightshade will bring you face-to-face with the devil, and you’ve seared the information into a terrified child’s mind. At this point, our hypothetical alien would likely nod and say, “Considering the crucial role stories serve, storytellers are surely carefully trained and controlled by your authorities.” And if we’re honest with ourselves, our reply would be, “Not yet, but we’re working on it.”

If you follow the news, you know we’re in another book-banning era. Politicians are loudly pushing to eliminate certain titles from libraries and the typical rebuttal is not that they shouldn’t be banning books, but that they’re banning the wrong books. Opposing factions will declare certain works to be problematic, obscene or blasphemous, but all seem to agree on this much larger, stranger premise: that fiction writers are now in charge of shaping public morals. Otherwise, what problem is a “problematic” book threatening to cause? Who cares if a novel is obscene if not for the assumption that obscenity can ruin a human mind? The claim of blasphemy is the most astonishing of all: not even an almighty creator can stand up to the raw, destructive power of the wrong words typed in the wrong order.

Meanwhile, those who are not directly pushing for restrictions still judge stories entirely on how effectively they transmit the right social and political messaging. In my other browser tab, redditors are currently debating how well a recent work is conveying the precepts of modern feminism. The work in question is a TV show about a female lawyer who is also an Incredible Hulk.

I’ll just say it: As a professional novelist who spins gruesome (and frankly, implausible) tales of time-hopping demons, I am not up to the task of shaping collective morality, especially if I’m primarily answering to corporations who cater to whatever group is yelling the loudest that week. But I’m also a hypocrite; if a fan says my last book made them a better person, I’ll happily accept the compliment. I can’t have it both ways. If my stories hold that kind of power, I have no argument against regulating them. Likewise, if I read a novel about, say, a race of alien slaves who learn to love their slavery, I’ll join the voices asking how in the world such a thing was approved for publication.

If you think it’s a ridiculous leap to suggest that fiction will soon be regulated into a tasteless paste, please remember that our current state of affairs — in which everyone is drowning in an ocean of cheap media — is incredibly recent. There are people alive who remember when television was brand new, and their great-grandparents likely had friends who never learned to read. Suddenly there’s this exponential explosion of storytelling, resulting in the control of cultural norms being yanked from politicians, priests and parents and handed to a bunch of weirdos like me. The traditional powers in society haven’t yet had time to adjust.

If you think it’s a ridiculous leap to suggest that fiction will soon be regulated into a tasteless paste, please remember that our current state of affairs — in which everyone is drowning in an ocean of cheap media — is incredibly recent. There are people alive who remember when television was brand new, and their great-grandparents likely had friends who never learned to read. Suddenly there’s this exponential explosion of storytelling, resulting in the control of cultural norms being yanked from politicians, priests and parents and handed to a bunch of weirdos like me. The traditional powers in society haven’t yet had time to adjust.

I believe they are adjusting now.

If fiction really does have the power to mold minds, it means it also has the ability to erode faith in institutions and foment radical change. That means the institutions that survive will be the ones that convince the population that stories are dangerous, that they must kick creatives out of the cockpit and let someone else take the controls. The result will be a world in which the only permissible fantasies are morality plays and propaganda, in which audiences read and watch bland feel-good messaging, feel nothing, but applaud anyway lest the surveillance drones detect their lack of enthusiasm.

If I’m to choose between that and a collective agreement that stories don’t really matter all that much, I’d prefer the latter. I mean, in theory, we wouldn’t have to choose if we could build a society in which it’s safe for creators to play with even the most repugnant ideas because their audiences have gained enough critical thinking skills to realize fictional stories aren’t marching orders. But I try not to let my ridiculous fantasies get away from me.

*Yes, I realize this was the plot of Galaxy Quest.

Jason Pargin is the author of If This Book Exists, You’re in the Wrong Universe, on shelves Oct 18, 2022.

Read Jason Pargin’s New Book If This Book Exists, You’re in the Wrong UniverseThe post A Future Without Fiction: Dragons and Book Bans by Jason Pargin appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

November 20, 2022

REVIEW: LA Noire

LA Noire by Rockstar Games and Team Bondi is one of those classic games that has managed to stand the test of time despite the fact it was not a massive success in its initial release. It was created under extremely taxing circumstances, using the latest in motion capture technology, and managed to find an audience but not an incredibly huge one. People came into it expecting another Grand Theft Auto and got something much closer to a linear adventure game.

The premise is WW2 veteran, Cole Phelps, has taken a job as part of the police in the post-war economic boom town that is Los Angeles. Cole has some bad memories of his time in the Pacific Front, no kidding, but is generally thought of as a war hero. However, he’s eager to put his past behind him and forge a new life by solving crimes as well as working his way up the incredibly corrupt LAPD. Unfortunately, Cole is as honest as the sun is shiny.

The premise is WW2 veteran, Cole Phelps, has taken a job as part of the police in the post-war economic boom town that is Los Angeles. Cole has some bad memories of his time in the Pacific Front, no kidding, but is generally thought of as a war hero. However, he’s eager to put his past behind him and forge a new life by solving crimes as well as working his way up the incredibly corrupt LAPD. Unfortunately, Cole is as honest as the sun is shiny.

The positives of the game are difficult to put into words because they’re really-really positive. The facial capture technology provides the game as close to photo realistic as was possible for the time and the characters mostly hold up even eleven years later. The recreation of Los Angeles is spectacular and the game really has the benefit of giving you a look into a cityscape that no longer exists.

The real hum dinger of the game, though, is the writing and this is probably one of the best written games of all time. Alongside Red Dead Redemption 2, this is a truly great story and would make a great movie or book if it wasn’t already an incredible video game. The individual cases are incredibly well-realized with stories ranging from a skeevy film maker blackmailing his actresses for sex, the infamous “Black Dhalia” case expanded into an entire story arc, and more mundane cases like a Jewish man murdering a man who abused him one too many times. The larger narrative is also pretty good, invoking both Chinatown as well as LA Confidential. If you haven’t seen either of those then Who Framed Roger Rabbit’s freeway plan.

The gameplay is primarily based around, shockingly enough, actual police work. Cole goes to crime scenes, examines them, gathers evidence, and then interrogates suspects. Sometimes he gets into shoot-outs and action scenes but surprisingly rarely. This is honestly closer to Phoenix Wright instead of Grand Theft auto. The goal is to figure out who did it, where, and with what as in Clue. Very often, it will involve watching the facial animations of suspects to see them overact some tick that gives away they’re lying.

The quality of the acting deserves its own salutation because it really is impressive to look upon. There’s some real quality actors here like John Noble among others. The characters tend to be archetypes but never so much that I didn’t believe they were real characters either. Which is another thing you don’t often see in these sorts of video games, if not video games in general.

Now for the flaws of the game. The first one is the fact that it’s actually very inconsistently designed. There’s no reason for the game to be an open world title because there’s nothing to do in the open world and nothing would have been lost if they’d just begun every case directly after the last one. A better developer might have also incorporated more open world activities or made the “random crimes” spread throughout the map ones you can find via map marker.

The game is also full of fantastic cases but also seems like it’s skipped over some important character beats as well. One emotional subplot is a main character having an affair in a time when that was illegal and could get you fired from your job. However, we never get to know the main character’s wife or the person they’re having the affair with so it comes out of nowhere. Just a little bit more would have gone a long way in terms of character development. The game is fantastic when it’s doing cases but drops the ball in a few areas.

There’s also a switch in protagonists when, bluntly, one of the protagonists is substantially better written than the other. An entire fascinating story about morphine smuggling, real life crime boss Mickey Cohen, and the Post-War financial situation for veterans is only available to learn about via video cutscenes. It would have been much better to actually play out the scenes. Of course, given the game took seven years to make, talking about the things they could have included is probably a mistake.

Gameplay wise, LA Noire is underwhelming because the investigations are entertaining enough but could have been supplemented with more action scenes as well as things like car chases as well as more exploration. The game is definitely for mature gamers with racism, sex, murder, and a dark gritty take on Post-War Los Angeles.

LA Noire was remastered in 2017 and a VR version of the game was released. Virtual Reality is not my thing but worth considering for those who are into the whole thing. Right now, it is about twenty dollars and I think it’s a real bang for your buck kind of deal. I strongly recommend the game even with all of its flaws.

The post REVIEW: LA Noire appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

November 19, 2022

REVIEW: Thrice by Andrew D. Meredith

Thrice is Andrew D. Meredith’s charming adventure fantasy infused with Slavic folklore. As the novel opens, we are introduced to Jovan, a thirty-five-year-old needle maker who is bloodily pounding some unfortunate bloke in a fit of rage. Jovan has a well-known history of violence and is soon forced to flee town. Most of the novel chronicles Jovan’s journey toward the suitably named town of Rightness, or Righteousness as one of the characters erroneously calls it.

Jovan travels with his adopted son, Leaf, a four-year-old boy who exudes innocence but is also wise beyond his years. Despite his rage issues, Jovan’s relationship with Leaf is that of a loving, protective father who cares deeply about his son. Andrew D. Meredith beautifully conveys this relationship between Jovan and Leaf, which forms the heart and soul of Thrice. I especially enjoyed reading about the small details of their relationship, which helped make Jovan and Leaf come alive off the page.

Jovan travels with his adopted son, Leaf, a four-year-old boy who exudes innocence but is also wise beyond his years. Despite his rage issues, Jovan’s relationship with Leaf is that of a loving, protective father who cares deeply about his son. Andrew D. Meredith beautifully conveys this relationship between Jovan and Leaf, which forms the heart and soul of Thrice. I especially enjoyed reading about the small details of their relationship, which helped make Jovan and Leaf come alive off the page.

Andrew D. Meredith’s prose in Thrice has the same classic feel as in Deathless Beast, capturing the great sense of humanity at the core of this novel. The vivid descriptions of the world are also beautifully conveyed by the author.

The plot comprises a delightful blend of folklore and classic fantasy elements organized into episodic chapters that gradually reveal Leaf’s surprising abilities, which make him a target for some of the more unsavory characters in the novel. The episodic style of Thrice generally works well, but it becomes a bit repetitive as Jovan and Leaf consistently encounter unscrupulous people along their journey. The plot has several twists, although some of the coincidences may require readers to suspend their disbelief (a common requirement when reading folktales), and the ending of the novel came too quickly for my taste. Still, Meredith’s gifted storytelling kept me glued to the pages and left me with a warm, fuzzy feeling inside.

Despite opening with a blood-splattering fight scene, Thrice is a very wholesome novel and will appeal to adult and adolescent readers alike. Grimdark readers looking for a brief respite from the dark side may appreciate this novel and its focus on small personal conflicts rather than the grand battles normally associated with epic fantasy.

Thrice is a deeply personal and touching tale and serves as a beautiful vehicle for Andrew D. Meredith’s poignant storytelling. It is a semi-finalist in Mark Lawrence’s 8 th Self-Published Fantasy Blog-Off (SPFBO8) and the first entry in Meredith’s Needle and Leaf series.

4/5

Read Thrice by Andrew D. MeredithThe post REVIEW: Thrice by Andrew D. Meredith appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

November 18, 2022

REVIEW: A Woman of the Sword by Anna Smith Spark

A book that beats you emotionally senseless, A Woman of the Sword is an intense experience delivered in only the way Anna Smith Spark delivers fiction. Its grimdark at its finest: a small but intense point of view of a mother struggling with motherhood, with sacrificing the things she wants to do with her life to be a mother, of feeling like she is a horrible parent, of life with PTSD, of fighting men and women and they way people treat each other, all scaled against the endless cycle of mass warfare that is the human condition.

In A Woman of The Sword, Lidae—warrior, wife, mother—watches the remains her ex-soldier husband burn in the ocean. While she tries to understand and even realise her own grief, her young children, Ryn and Samei, don’t quite grasp what this means and continue to demand of her emotionally and physically. The village members try to help, but Lidae can’t hold herself together, and she struggles to be a mother amongst her own inner anger and fear and loss.

In A Woman of The Sword, Lidae—warrior, wife, mother—watches the remains her ex-soldier husband burn in the ocean. While she tries to understand and even realise her own grief, her young children, Ryn and Samei, don’t quite grasp what this means and continue to demand of her emotionally and physically. The village members try to help, but Lidae can’t hold herself together, and she struggles to be a mother amongst her own inner anger and fear and loss.

Then, one night, the soldiers come and burn her town. This starts an incredible, emotional ride of motherhood and soldiering that spans a decade of war and brutal inner turmoil and struggle as king after queen after king throw the land and their armies at each other time and again with Lidae and her boys in the middle of it.

A Woman of the Sword is both a grimdark military fantasy and a heavy character-focussed story. The military side of it is a backdrop to a story of broken family, of broken people, and what broke them. Smith Spark’s ability to paint beautiful and horrible scenes against which to tell this heart wrenching story—as she did in her Empires of Dust trilogy starting with The Court of Broken Knives—is on full display here. This book is a beautiful read.

The key theme that really hit home for me is the one of motherhood. Of feeling like you’re not very good at it, of wondering how you can be so good at one thing (soldiering, in Lidae’s case), face so many colossal challenges, yet not be able to connect with your son enough to know how to not make him cry like other mothers do. Not only am I not a parent, but I’m not a woman, and yet Smith Spark managed to make that theme reach right out of the second chapter and vice-grip my heart.

A Woman of the Sword also delves into themes of PTSD (as I understand it) and struggling mothers, and (I think), post partem depression. Again, I am not somebody who has these experiences, but Smith Spark hit me with them, hard.

A Woman of the Sword is written across two timelines, one with the boys young, and one with them as teenagers. Watching Lidae watch her sons make adult decisions, weighing them against her own when she was young and indestructible and ruthless is one of the most interesting parts of this book, and I definitely cannot help but feel that not being a parent myself means that I am incapable of plumbing the full emotional depths of this book. This book is an absolute MUST read for the parents in the dark / grimdark fantasy fan base.

Something Smith Spark does better than anything I can remember reading in recent memory, is really show how small the individual foot soldier is in the greater scheme of things. How unlikely it is that even the best soldiers will ever have more than a passing contact with a king or queen, dragon, or mighty hero. How an army is about the many, and how little it cares for the individual. Of how easily discarded and forgotten the individual is. If you’re after a book about how the farmhand becomes the general, this is not that book. The army and the battles are scenery (awesomely written and integral to the plot) to Lidae and her sons’ relationship, and to motherhood in the deepest darkest places.

A Woman of the Sword is brilliant grimdark fantasy. It hurts to read at times, is unputdownable at others, and I feel different people at different stages of their lives are going to take away different things. This is Anna Smith Spark at her heart-wrenching, mythic-feeling, storytelling best, and just completely unmissable.

Read A Woman of the Sword by Anna Smith SparkThe post REVIEW: A Woman of the Sword by Anna Smith Spark appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

November 17, 2022

REVIEW: A Song for the Void by Andrew C. Piazza

A Song for the Void is Andrew C. Piazza’s masterful cosmic horror set in the South China Sea during the Opium Wars between Great Britain and China in the mid-nineteenth century. This historical setting is the perfect backdrop for Piazza’s exploration of nihilistic philosophies and psychological manipulation.

A Song for the Void is told from the first-person perspective of Dr. Edward Pearce, a surgeon on a British naval ship, whose backstory is full of personal tragedy, including the death of his wife and son during childbirth and the subsequent murder of his adopted daughter in Hong Kong. Against his own better judgment, Pearce finds solace in the opium pipe, which numbs his pain and replaces his grim reality with a sense of euphoria. Piazza poignantly conveys Pearce’s struggles with opium addiction throughout A Song for the Void, including detailed descriptions of the physical and psychological effects of withdrawal. I was especially touched by the portrayal of Pearce’s sense of shame about his addiction.

A Song for the Void is told from the first-person perspective of Dr. Edward Pearce, a surgeon on a British naval ship, whose backstory is full of personal tragedy, including the death of his wife and son during childbirth and the subsequent murder of his adopted daughter in Hong Kong. Against his own better judgment, Pearce finds solace in the opium pipe, which numbs his pain and replaces his grim reality with a sense of euphoria. Piazza poignantly conveys Pearce’s struggles with opium addiction throughout A Song for the Void, including detailed descriptions of the physical and psychological effects of withdrawal. I was especially touched by the portrayal of Pearce’s sense of shame about his addiction.

Horror comes in the form of an evil-looking eye in the sky, which the sailors view as a strange stationary comet. The eye is known as the Darkstar and is the physical manifestation of nihilism, manipulating the minds of the crew members to convince them that their lives are meaningless. The power of the Darkstar is especially potent when its victims are high on opium, causing them to question the purpose of life and even the existence of reality itself.

The novel is a page-turner, full of action and deception. The philosophical discussions are perfectly balanced by the novel’s heart pounding action. Grimdark readers will especially enjoy the gruesome scenes in the latter part of the novel.

Beyond Dr. Pearce, there is also a great cast of supporting characters, whose loyalties are not at all clear. My favorite supporting character is the Chinese woman Jiaying, who is underestimated by most of the Western crew members.

From the historical setting to the detailed descriptions of opium abuse, Andrew C. Piazza has put a great deal of careful research into this novel. Altogether, A Song for the Void feels like a marriage between R.F. Kuang’s The Poppy War and the classic seafaring novels of Herman Melville. Both Piazza and Kuang explore the potential metaphysical implications of opium use and portray heartbreakingly honest accounts of addiction. Like Melville, Piazza treats an isolated ship as a microcosm for humanity’s place in the universe and explores the consequences of madness at sea. Despite these similarities, Piazza demonstrates tighter storytelling than either Kuang or Melville.

A Song for the Void is cosmic horror at its finest, dripping with existential dread but ultimately leaving the reader with a sense of hope. Piazza’s novel is a finalist in Mark Lawrence’s 8 th Self- Published Fantasy Blog-Off (SPFBO8).

5/5

Read A Song for the Void by Andrew C. PiazzaThe post REVIEW: A Song for the Void by Andrew C. Piazza appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

November 16, 2022

REVIEW: Feed Them Silence by Lee Mandelo

Feed Them Silence is the latest work from author Lee Mandelo. Published by TorDotCom, this novella is a ‘near-future’ piece of science fiction following the work of Doctor Sean Kell Luddon’s attempt to ‘be in kind’ with a non-human creature. In this case, they were creating a neurological link between her and one of the last remaining wild grey wolves in existence to learn more about these beasts before they are driven to extinction by climate change and other human interference. Split into four chapters, this short fiction is exceptionally compelling, and a thought-provoking read.

Through Mandelo’s protagonist, Sean, the reader follows this project to create to ‘be in kind’ with a wild wolf from its inception, the search for funding and academic support, and ultimately the results the experiment has. Although Mandelo covers a lot in just over a hundred pages, the novella flows well, and their lyrical prose engrossed me. Feed Them Silence does not just look at Dr. Kell-Luddon’s scientific research. It also focuses on the impact it has on the relationships in her life. In particular, the novella shows how her obsession is destroying the relationship with her wife, fellow academic Riya. I enjoyed the academic setting and the plausible nature of the science fiction elements to Feed Them Silence. Still, Sean’s questionable morality and the degeneration of her life away from her work would stick with me after finishing this novella.

Through Mandelo’s protagonist, Sean, the reader follows this project to create to ‘be in kind’ with a wild wolf from its inception, the search for funding and academic support, and ultimately the results the experiment has. Although Mandelo covers a lot in just over a hundred pages, the novella flows well, and their lyrical prose engrossed me. Feed Them Silence does not just look at Dr. Kell-Luddon’s scientific research. It also focuses on the impact it has on the relationships in her life. In particular, the novella shows how her obsession is destroying the relationship with her wife, fellow academic Riya. I enjoyed the academic setting and the plausible nature of the science fiction elements to Feed Them Silence. Still, Sean’s questionable morality and the degeneration of her life away from her work would stick with me after finishing this novella.

Mandelo wrote about the erosion of Sean’s relationship in a captivating way. Early on in Feed Them Silence, I felt like Sean would be a very clear ‘bad’ character; from the first few pages, she is selfish, egotistical, and happy to ignore her wife’s ethical issues with her wolf project. But Mandelo’s characterisation is much more complex, and Sean is more than a modern take on the power-mad scientist. It was also refreshingly read as a science fiction novella with the main character as a complex queer female academic working in STEM. But the fact that Sean is not meant to be likeable meant that it was sometimes a struggle to sympathise with her at darker points in the story.

I am loathed to describe Feed Them Silence as haunting, in case it gives a ghoulish suggestion, but it is definitely a narrative I cannot shake off. I read the book over a few days (but it could easily be devoured in one sitting if a reader has the time), and even after a couple of days to collect my thoughts to write the review, I find it unsettling. As with some other near-future science fiction works, Feed Them Silence is not dystopic, but it is truly unnerving that the science fiction Mandelo shows here is probably not too far off being science fact. What that ability might mean for humanity is quite a disquieting thought.

Feed Them Silence is an excellent novella. It has a tense sci-fi narrative, captivating characters, and a moral ambiguity that should appeal to readers of Grimdark Magazine even though the novella is not typically dark.

Thank you very much to Lee Mandelo and the team at TorDotCom for sending me an ARC to be able to provide this review.

4/5.

Read Feed Them Silence by Lee MandeloThe post REVIEW: Feed Them Silence by Lee Mandelo appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

November 15, 2022

REVIEW: Deathless Beast by Andrew D. Meredith

Andrew D. Meredith combines maximalist worldbuilding with a nuanced character-driven plot in Deathless Beast, the first volume of his epic fantasy series, The Kallattian Saga.

With Deathless Beast, Meredith has created a marvelously complex world that feels Tolkienesque in its scope and detail, but without falling into the usual epic fantasy trap of copying The Lord of the Rings. Meredith looks past the use of classic Tolkien fantasy elements (elves, dwarfs, orcs, etc.) to create his own world that feels wholly original, complete with its own set of fantastical fauna, races, religions, and more. If your goal with reading fantasy is to lose yourself in a wondrous new world, then look no further than Deathless Beast.

With Deathless Beast, Meredith has created a marvelously complex world that feels Tolkienesque in its scope and detail, but without falling into the usual epic fantasy trap of copying The Lord of the Rings. Meredith looks past the use of classic Tolkien fantasy elements (elves, dwarfs, orcs, etc.) to create his own world that feels wholly original, complete with its own set of fantastical fauna, races, religions, and more. If your goal with reading fantasy is to lose yourself in a wondrous new world, then look no further than Deathless Beast.

The worldbuilding itself is introduced through Malazan-style immersion, without any handholding or info dumps in the main text. Fortunately, readers can consult several glossaries in the back of the book to help keep track of the characters and other elements of worldbuilding. The glossaries gave just the right level of detail so that I never felt lost reading the novel.

Despite the vastness and intricacy of the worldbuilding, Deathless Beast is fundamentally a character-driven story. My favorite characters are Hanen and Rallia Clouw, a brother-and-sister duo that serve as part of the Black Sentinels, a group of mercenaries for hire who have their own code of honor. Mercenary work is a family business for the Clouws, but the other Black Sentinels don’t necessarily share the same sense of loyalty.

The next point-of-view character is Jined Brazstein, a Paladin of the Hammer, a holy order of knights. Jined feels called to a deeper faith while the Paladin order itself appears to be on the decline.

The final main character is Katiam Borreau, a Paladame of the Rose, a female holy order analogous to the Paladins. Katiam serves as personal physician to both the Matriarch of her order and the Prima Pater (first father) of the Paladins. Katiam feels like her life has been decided for her, but new possibilities open when she makes an unexpected discovery.

Religion is featured prominently in Deathless Beast, including a fully developed polytheistic belief system with a complex set of religious vows. All of these details are spelled out clearly in the glossaries. However, the real focus of Deathless Beast is not on organized religion itself, but on the personal faith of its principal characters as they strive to find a deeper purpose in their lives. This personal focus makes the characters feel real and relatable.

Andrew D. Meredith’s prose has a classic feel but without the stiffness sometimes associated with epic fantasy. The plot itself is a slow burn, full of introspective dialogue. Meredith’s unhurried, contemplative writing recalls Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. But Deathless Beast also features several well-written action scenes interspersed throughout the longer, more introspective passages.

Although Deathless Beast has a few dark scenes, it is not nearly as dark as one might infer from the cover. Rather, the author has unabashedly embraced the “epic” in epic fantasy.

Grimdark readers, nevertheless, will appreciate the depth of Meredith’s character development and the full range of gray morality at play amongst the Dark Sentinels and Paladins, with plenty of corruption hiding beneath the surface. My favorite scene came about 75% into the novel, when we learn the origin of the titular beast. Although much of the plot felt like setup for future volumes of the series, Deathless Beast does have a satisfying, albeit somewhat abrupt, conclusion.

At its best, Deathless Beast will restore your faith in classic epic fantasy, combining Tolkienesque worldbuilding with a Proustian level of elegance and introspection. I look forward to reading more in this world.

4/5

Read Deathless Beast by Andrew D. MeredithThe post REVIEW: Deathless Beast by Andrew D. Meredith appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

November 14, 2022

REVIEW: A Dance For The Dead by Nuzo Onoh

Nuzo Onoh lives up to her title of “Queen of African horror” with her latest novel, A Dance For The Dead. Stitched with powerful imageries of dark magics and secret rites, Onoh weaves a macabre tale of revenge.

A Dance For The Dead takes place in the Kingdom of Ukari and the ten villages. The world Onoh depicts is one of cruelty and raw beauty. I was mesmorized with the culture, from the famed festivals featuring dancing and drinking sweet palm-wine to ritual sacrificing and the nightmares plaquing the Ukari village every night.

A Dance For The Dead takes place in the Kingdom of Ukari and the ten villages. The world Onoh depicts is one of cruelty and raw beauty. I was mesmorized with the culture, from the famed festivals featuring dancing and drinking sweet palm-wine to ritual sacrificing and the nightmares plaquing the Ukari village every night.

The morality of the characters in A Dance For The Dead are complex as their culture demands of them. The Kingdom of Ukari has many enemies and scheming allies. Slavery is rampant and even those born into power can have their titles stripped all so easily. Learning the hidden secrets and traumatic pasts of these morally gray characters intensified the frightening moments of Onoh’s novel.

A Dance For The Dead is told from three points of view. Diké is the first-born son of King Ezeala and leader of Ogwumii, the deadly warrior cult. While he was asleep, traitors had moved his body into the forbidden Shrine of Ogu n’Udo. In a span of one night, the heir to the Ukari throne has become an Osu, a fate worse than death. To reclaim his name, he must risk his life and face horrors in the ancestral realm. Big-Bosom is a woman haunted by her late father’s dishonored legacy. While she is of marrying age, no man will ever wed into the clan of the traitor. She longs to escape her abusive brothers and to have the affection of Ife, the youngest son of the King.

Among the first introduced in A Dance For The Dead is Ife. He is titled “Feather-Feet” and famed as the reincarnation of Mgbada, the greatest dancer in the ten villages and beyond. He resists traditional expectations of marriage, preferring to spend his nights dancing and getting drunk on palm-wine. His merriment days end when his older brother Diké falls from grace. Now he must find his courage to save his brother.

A Dance For The Dead is fast paced and flushed with bone-chilling scenes. I love how Onoh uses horror to drive character development. Nothing is scary for the sake of jump scares, rather her horror elements give expression to past wrongs. I did wish certain parts were slowed down, especially relationships between certain characters. While the outcome felt natural, I wanted to see more of their development.

A Dance For The Dead is a celebration of nightmarish imagination. It is African-horror triumphant. I am eager to read more from Nuzo Onoh.

Read A Dance For The Dead by Nuzo OnohThe post REVIEW: A Dance For The Dead by Nuzo Onoh appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.

November 13, 2022

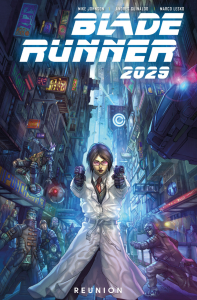

REVIEW: Blade Runner: 2029 by Mike Johnson (W), Andres Guinaldo (A)

The world of Blade Runner: 2049 is, in a word, bleak. Somewhere on the outermost edges of dystopia, the grim bordermarches of a not-too-distant future that straddles the razor’s edge of horrifying and mystifying.

Blade Runner: 2029 at its core is a war story, a story of revolution and truths and how the truths of different peoples—however people are defined—can create uproarious conflict and drag the lives of everyone around them into it, even an entire city. Set, as most the Blade Runner franchise is, in Los Angeles, we follow the titular Blade Runner, Ash, as they pursue a revolutionary replicant across the city after the replicants have been outlawed. It’s a chase that takes more twists and turns than an apoplectic rattlesnake, tearing across, above, and below the sprawling, decaying metropolis. As is so often the case in stories of this nature, Blade Runner: 2029 has no clearly defined good guys or bad guys. There is a protagonist, sure, but the morals of all the characters throughout are ambiguous at best and for the most part everyone isn’t so much self-serving as desperate to fulfill their overarching goals. It creates a kind of amorphous tension, a dynamic that makes it almost impossible to truly root for one side or the other. The character who is ostensibly the antagonist is immensely sympathetic, in no small part due to their palpable charisma—oftentimes eclipsing Ash, who acts as the axis around which the entire story turns.

Blade Runner: 2029 at its core is a war story, a story of revolution and truths and how the truths of different peoples—however people are defined—can create uproarious conflict and drag the lives of everyone around them into it, even an entire city. Set, as most the Blade Runner franchise is, in Los Angeles, we follow the titular Blade Runner, Ash, as they pursue a revolutionary replicant across the city after the replicants have been outlawed. It’s a chase that takes more twists and turns than an apoplectic rattlesnake, tearing across, above, and below the sprawling, decaying metropolis. As is so often the case in stories of this nature, Blade Runner: 2029 has no clearly defined good guys or bad guys. There is a protagonist, sure, but the morals of all the characters throughout are ambiguous at best and for the most part everyone isn’t so much self-serving as desperate to fulfill their overarching goals. It creates a kind of amorphous tension, a dynamic that makes it almost impossible to truly root for one side or the other. The character who is ostensibly the antagonist is immensely sympathetic, in no small part due to their palpable charisma—oftentimes eclipsing Ash, who acts as the axis around which the entire story turns.

Ultimately, Blade Runner: 2029 is an extremely enjoyable series that is as immersive and entertaining as the rest of the Blade Runner comics that Titan has been pumping out and I recommend it just as highly as the others. The writing team is the same as Blade Runner: Origins, so the dialogue is just as well-written and crisp, the drama just as well thought out, but this time around we see Andres Guinaldo undertaking the art duties and their work is refreshing and a joy to behold. There’s something of the old Metal Hurlant magazine in the linework and compositions, in the character’s expressions and the action itself. There’s definitely something of the European comic scene’s flair in the art, and to be quite frank it’s lovely and full of character. More than once (more, probably, than a dozen times) I caught myself just staring at a page or a tableau for a few minutes before even bothering to read anything because of how impressive the art on display was.

Blade Runner: 2029 is a breathtaking read and a thrill-a-minute series that fans of the original franchise, the other comics, and the sci-fi genre alike can jump in and enjoy, and to make matters all the better: it’s not the end. Ash’s story will continue, much sooner rather than later, in the upcoming Blade Runner: 2039 and I can’t wait.

Read Blade Runner: 2029 by Mike Johnson (W), Andres Guinaldo (A)The post REVIEW: Blade Runner: 2029 by Mike Johnson (W), Andres Guinaldo (A) appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.