Kieran Fanning's Blog, page 2

October 25, 2024

October 19, 2024

Irish Independent recommends 'Haunted Ireland'

October 18, 2024

Dublin City FM Recommendation

October 9, 2024

Irish Times review of 'Haunted Ireland'

October 2, 2024

Westmeath Examiner review of Haunted Ireland

September 30, 2024

HAUNTED IRELAND review in Recommended Irish Reads 2024

September 24, 2024

July 25, 2024

The Wandering of the Déise

The Wandering of theDéise

The Déise were one ofthe first tribes to settle in Waterford, but their journey to the county was along and arduous one, filled with warfare and magic. It was first documented inthe 12th century manuscript, The Book of Leinster, under the titleof ‘Tairired na nDésse’ (The Wandering of the Déise).

The story of the Déisetribe begins in 3rd century County Meath where they owned a lot ofland near Tara, which was the capital of Ireland at the time. One of theirleaders was called Óengus of the Dread Spear because he owned the Spear ofLugh, one of the four treasures of the Tuatha Dé Danann. It was a magicalweapon which, once thrown, never missed its mark. It had a life of its own andhad to be chained inside a cauldron for safe keeping. The cauldron had to befilled with blood to stop the spear from going on fire. The weapon made Óengusa powerful and much feared leader.

For years, the Déiselived in peace beside the high king of Ireland, but that ended when one of the highking’s sons, Cellach, fell in love with Óengus’s niece. She had no interest in him,and rejected his advances, but Cellach was a prince who was used to getting whathe wanted, so he kidnapped the girl and took her to Tara.

When Óengus heard whathad happened to his niece, he was angry and went to Tara to get her back. Hewas accompanied by a small band of men carrying a large cauldron with Lugh'sdreaded spear inside, just in case. At the gates of Tara, Óengus called out forthe release of his niece, but Cellach refused.

Enraged, Óengus orderedthat his spear be released. He put on a thick pair of leather gloves and whenhis men had loosened the spear’s chains, he reached into the cauldron of blood.As soon as his fingers wrapped themselves around the shaft of the weapon, hefelt the energy pulsing inside it. He lifted it out, dripping with blood and convulsingrestlessly. It took all his strength to hold onto the spear because it had alreadyread the holder’s mind and knew who its target was. But still, Óengus waited.The spear vibrated so much that it started to glow red, getting hotter andhotter, until it burst into flames. Only then, did Óengus release it.

The burning lance shot upinto the air with its three chains flailing at its sides, scorching a trail of fireover the gates of the high king and into his royal fort. It weaved in and outbetween the king’s soldiers, making a beeline for Cellach. As it reached theprince, the king himself tried to stop it, but the weapon swerved to avoid him.In doing so, one of its trailing chains, caught the king in the eye, blindinghim, which meant he didn’t have to witness the weapon fly straight through hisson, leaving a burning hole in his chest. By the time Cellach hit the ground,dead, the spear had returned to its thrower and was being rechained once again insideits cauldron.

In fear of another attack,the high king released Óengus’s niece. It was only when the Déise were gonethat the king realised that he had just lost more than a son and an eye,because the law stated that the high king had to be without blemishes. In otherwords, a man with only one eye could not be the high king of Ireland. Angeredby all that he had lost, he rallied an army and went after Óengus.

After seven greatbattles, the Déise were defeated and driven out of County Meath. They headedsouth into County Laois where they fought the Uí Bairriche clan and drove themoff their land. They stayed there for thirty years but the Uí Bairriche regroupedand grew in strength until they could retaliate. After a lot of fighting, theDéise were defeated and again, driven off their land.

Homeless, they wandered furthersouth to Ard Ladrann, which is now the parish of Ardamine, near Gorey in CountyWexford. There, they were given land by the king of Leinster in exchange forhis marriage to a Déise woman. When this woman got pregnant, a druid called Bríprophesised that the child would be a girl and that ‘all the men of Ireland shallknow her, and her mother’s kindred will seize the land on which they dwell.’ Inother words, this girl would end the wandering of the Déise and would finallyfind them a home.

Because of this prophecy,the child was treated with the greatest of care when she was born. She was evenfed the flesh of little boys so that she might grow up strong. She became knownas Eithne the Terrible, because little boys were terrified of her.

Meanwhile, the new high kingof Ireland felt bad about how the Déise had been banished from their land andinvited them back but they refused, putting all their hopes into the prophecythat Eithne the Terrible would find them a new home.

When Eithne’s father,the king of Leinster died, his sons took over and wanted the Déise off theirland so they drove them into the Kingdom of Ossory, which is modern day CountyKilkenny. The Déise were not welcomed there and were driven into the Kingdom ofMunster. It was here that Eithne the Terrible, now a grown woman of greatbeauty, would fulfil the prophecy of her birth.

She was so alluring thatwhen the king of Munster saw her, he asked her to marry him, but Eithne wasmore interested in finding a home for her people than becoming a queen so sheasked the king what he was willing to offer for her hand in marriage. The kingwas so taken with Eithne that he said she could have three wishes.

‘And I can ask foranything?’ she clarified.

The king nodded.

‘For my first wish,’said Eithne, ‘I ask for revenge upon the Kingdom of Ossory, for they treated mypeople very badly.’

The king agreed, and thenext day, he sent his soldiers into Ossory. A great battle raged, but the Ossorytroops held firm against the invaders.

‘Has my wish beengranted?’ Eithne asked the king.

He shook his head. ‘Wecannot defeat them.’

‘Perhaps the wand cansucceed where the sword has failed,’ said Eithne, bringing the king to meet Brí,the druid who had prophesised her greatness.

When they asked for hishelp to defeat the Ossory army, the druid mixed up a brew of leaves and herbs,before swallowing it and going into a deep trance. Eithne and the king waiteduntil he snapped out of it.

Finally opening hiseyes, Brí said, ‘The battle shall be lost in the morning by the side that firstspills their enemy’s blood.’

‘So, we have to makesure that one of our warriors gets wounded first?’ the king, said to Eithne.

She nodded.

‘I can tell one of mymen to walk into the ranks of the enemy and not defend himself,’ suggested the king.

‘That might work,’ saidEithne, ‘but can we know for sure that he won’t lift his blade to defendhimself? When faced with death, a man’s instinct is to survive.’

The king agreed. ‘Wecould send him without weapons.’

‘The enemy might grow suspicious,’Eithne said, turning to her druid. ‘Is there another way?’

‘There is always anotherway,’ said Brí.

The next morning, thedruid conjured up a powerful magic spell to turn one of the king of Munster’ssoldiers into a red cow. The animal was then sent into the enemy’s camp. Assoon as the Ossory soldiers saw it, they killed it, spilling the first blood ofthe day.

‘Now you may attack,’declared the druid.

The king of Munster’sarmy charged and easily defeated their enemy.

The king, pleased to beone step closer to marrying Eithne, said, ‘And what shall your second wish be?’

Eithne didn’t have tothink about this, for she’d had this wish her whole life. ‘All I’ve ever wantedis land for my people and an end to their wandering. I wish for a home for theDéise.’

After much consideration,the king of Munster granted the Déise land which stretched from Inchinleama inthe West to Creadon Head in the East, and from the River Suir in the North tothe sea in the South. This territory would eventually be named Waterford, buteven today, the county is still widely known as the Déise county.

‘And what of your finalwish?’ the king asked Eithne.

‘That the Déise be declared a free people and thatour name live long in the minds of men.’

The king held his handout to his bride to be and nodded. ‘Your wish shall be granted.’

Eithne smiled and tookhis hand. ‘Time will tell.’

Though Ireland would seemany changes over the next two millennia, including the arrival ofChristianity, the Vikings, the Normans and the English, you only have to attenda Waterford hurling match and hear the crowd roar ‘Up the Déise!’ to know thatEithne’s final wish came true. The spirit of the Déise lives on in CountyWaterford.

July 12, 2024

Cover reveal!

Check out the cover of my new book, created by the talented Mark Hill. It will be published by Gill in October. Pre-order here!

June 15, 2024

Lady Betty - Ireland's First Hangwoman

Stone Court shopping centre in the square in Roscommontown is a bustling place full of happy

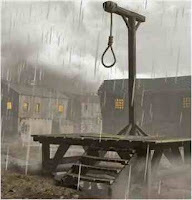

Stone Court shopping centre in the square in Roscommontown is a bustling place full of happyshoppers and diners, but this was notalways so, for the building’s walls hold a dark and violent history. Thecastellated parapet, the towering belfry and two rusty hinges on the façade areall that remain of the building’s former life as the Old Gaol, and home to a gallowsthat was renowned as having the biggest drop in Ireland. The jail housed someof Roscommon’s worst criminals, many of whom were hanged there. One criminalmanaged to avoid the noose by offering to do the executions when the hangmandidn’t turn up. Her name was Lady Betty, and she was the first hangwoman inIreland.

Her real name was Elizabeth Sugrue, and before she cameto Roscommon, she lived in Kerry on a small, rented farm with her husband andtwo sons. The 18th century was a difficult time for Catholic farmerslike the Sugrues. The Penal Laws denied them an education and an opportunity topractice their faith, with a price put on the head of any priest who broke thelaw by celebrating Mass. Many landlords cared little about their tenants andmercilessly evicted them if they couldn’t pay the ever-increasing rent. It wasa time of great unrest in Ireland, giving rise to rebellion and attacks on wealthylandlords.

Unlike most Irish Catholics, Elizabeth Sugrue waseducated and even owned some books. When she wasn’t working on the farm or intheir small cottage, she taught her husband and sons to read and write. Shealso liked to draw pictures, which was an unusual hobby at the time, when mostIrish people didn’t have time for hobbies.

Disaster struck when Elizabeth’s husband died, and shehad to sell her books to pay for the funeral. Unable to pay the rent, she wasevicted and forced to walk the roads with her two sons, begging for scraps offood. She picked up occasional work, reading or writing letters for people whowere illiterate, but the life of a beggar is no life for anyone, especiallychildren. When her youngest boy got sick, there was nothing Elizabeth could doexcept cradle him in her arms on the side of the road, as his little lifeextinguished before her eyes.

After that, Elizabeth sank into deep bouts of depression,and started to lose her mind, which was understandable, considering what shehad been through. Though she loved her remaining son, Pádraig, she was oftenimpatient, cross, and at times, cruel to him.

Travellingthe roads of Munster, and then Connacht, Pádraig, now almost an adult, took itupon himself to do his mother’s job of reading and writing for people, inexchange for a few morsels of food. All the while, however, he dreamed of abetter life.

‘Someday, I’ll be rich, Mother,’ he said. ‘And I’ll look after you in a big fancyhouse with servants.’

Insteadof encouraging him, Elizabeth laughed sourly at her son’s foolish ambitions andtold him he’d never amount to anything.

Whenmother and son found an abandoned cottage in Roscommon, they settled there, andthough they weren’t much better off than they’d been on the road, at least theyhad a roof over their heads.

Pádraigcontinued to read and write letters for people in return for a few pennies,which he used to buy food for himself and his mother. When he had some tospare, he put a penny aside for himself. From discarded newspapers, he educatedhimself about the wider world, including America, which seemed to be a land of changeand opportunity. His mother, suffering badly with her nerves, becameincreasingly difficult to live with, and often shouted and hit her son, untilhe could take it no longer. When he had enough saved, he packed a bag and leftfor America, leaving a note to say that he loved her and would return when he’dmade his fortune.

Elizabethscreamed in fury and threw his note into the fire. Forced to defend forherself, she started renting out a room in her home to travellers who couldn’tafford to stay in a proper inn. Though she was angry at her son for abandoningher, she was delighted to get a letter from him saying that he’d joinedWashington’s forces in the American War of Independence. He even left anaddress for her to write back, which she did, as soon as she had enough moneyto buy a stamp. Desperately, she waited for a second letter and when none came,she feared he’d been killed in the war.

Theyears passed and Elizabeth became more and more bitter at a world that hadstolen everything from her. One wet winter’s night, there was a knock on herdoor and she opened it to a well-dressed man, standing with his horse in therain.

‘Ibelieve you take lodgers?’ said the man.

Elizabethdid take lodgers but not ones as wealthy as this gentleman. She wondered why hedidn’t go to a real inn, but of course she didn’t ask. She wasn’t about to turndown the opportunity to earn some money. Inviting him in, she said he couldhave a bed, but that she had no money for food. Her eyes widened when the manproduced a pouch, heavy with coins, and taking out a sovereign, he told her togo buy some. She dashed off through the rain and returned with enough food tofeed her whole neighbourhood.

Afterthey’d filled their bellies, Elizabeth showed the gentleman to his room, andshe went to bed but couldn’t sleep. All she could think about was the man’s bagof coins in the room next door.

Takinga knife from the kitchen, she stole into his room with the stub of a candle tolight her way. Her visitor was fast asleep so she rummaged in his belongingsbut couldn’t find the pouch. Then, she noticed a leather cord hanging out fromunder his pillow. It made sense that he would keep it there. Would she be ableto remove it without waking him?

Herhand trembled as she gently pulled the cord, feeling the weight of a pouch ofcoins coming with it. Inch by agonising inch, she manoeuvred the pouch out andalmost had it free when the man woke and grabbed her wrist.

Instinctand fear kicked in, and she plunged the knife into the man’s neck. In seconds,he was dead.

Elizabethpulled out the pouch of sovereigns and then thought about how she’d dispose ofthe body, but first, she decided to check his belongings for more valuables.

Shegasped in shock when she found a letter with handwriting that she recognised –her own! It was the letter she’s sent to Pádraig. Trying not to think aboutwhat this meant, she rummaged through the rest of his stuff and found a diary.She flicked through the pages to the most recent entry.

I have finally arrived in Roscommon andtomorrow I shall visit my mother. I know she won’t recognise me after all theseyears but it will be good to see her again. I won’t reveal my identity untilI’ve spent a night with her. That will give me a chance to see if she’smellowed with age. If she has, I will look after her in luxury for the rest ofher days, like I promised I would.

Elizabeth’sscream woke her neighbours.

‘I’vekilled my son!’ she roared, sobbing with tears and hugging Pádraig’s lifelessbody.

Filledwith grief, rage and terror, she shrieked into the night, like a demented banshee,until some of the neighbours entered her hovel and came face to face with thehorrific spectacle of a mother weeping over the son that she’d murdered.

Elizabethwas arrested, imprisoned in Roscommon Gaol, tried, found guilty of murder, andsentenced to death by hanging.

Onthe morning of her execution, a huge crowd had gathered in the square beforethe Old Gaol. Some were spectators, there to be entertained by the grisly event.Other were friends and family of some of the twenty-five sheep-stealers,cattle-rustlers and shop lifters standing before the gallows. A few of theprisoners, from a gang called the Whiteboys, seemed to have a lot of supportfrom the crowd. The Whiteboys were a secret society who disguised themselves inwhite robes and carried out attacks on landlords who treated their tenantsbadly.

Theprisoners lined up at the dangling noose but there was no sign of the hangman.

‘He’ssick,’ a messenger said, but the sheriff didn’t believe a word of it. He knewthe hangman didn’t turn up because he was afraid of the Whiteboys.

Halfthe crowd called for blood, while the other half called for the prisoners to bereleased. The sheriff could do neither. Nor could he return them to the jailbecause their cells had been set aside for new prisoners. Try as he did, hecouldn’t find anyone to perform the hangings.

Then,a lone voice called out. ‘Spare me life, yer honour. Spare me life an’ I’ll hangthem all.’ It was Elizabeth Sugrue.

Thesheriff, though dubious about letting a woman do the job, was desperate, so heagreed. One by one, Elizabeth hung the prisoners, and seemed to take pleasurein doing so, despite the cries of hate she received from the Whiteboysupporters, who threatened to kill her. Afterwards, the sheriff knew it wouldbe unsafe to release Elizabeth into the public, so he offered her a permanentposition as hangwoman of the jail.

Sheaccepted, and took up residency in the building, taking to her new role withrelish. For efficiency, she even had the gallows moved from the square tooutside her room on the third floor. Prisoners would enter her room and besketched by her, before being noosed and pushed onto a platform outside.Elizabeth would then pull back a lever and the convict would plummet to his/herdeath below.

Inher room, Elizabeth displayed the charcoal portraits of all the prisoners shehad executed. She became known as Lady Betty, due to her interest in art,reading and writing, and the fact that she was a little more refined thaneverybody else in the prison.

Shewas also known to have enjoyed flogging convicts for the public and displayingcorpses of rebels outside the Old Gaol, which made her one of the most hatedwomen in Roscommon, where people referred to her as the ‘Woman from Hell’.

Thoughshe was pardoned for her own crime in 1802 as payment for her services to the jail,the public’s hatred of her eventually caught up with her. In 1807, a prisonerwho had been breaking rocks in the prison yard as punishment, struck her overthe head with a stone and killed her.

Shewas buried in an unmarked grave inside the prison walls, but long after herdeath, her ghost was said to haunt the jail, looking for one more neck tonoose. Her name was used to threaten naughty children in Roscommon for years.‘If you don’t be good, Lady Betty will get you.’

LadyBetty likes to draw

Theface before it drops the jaw.

Prayto Jesus that she might

Notsmile upon your face tonight.

Fromthe play, Lady Betty, by Declan Donnellan

By Kieran Fanning