Mark Simner's Blog, page 6

April 3, 2016

Young Douglas Haig

Most people will have heard of Field Marshall Douglas Haig, who is often remembered as the ‘Butcher of the Somme’ due to the horrendously high casualty rate suffered by the British Army during the offensive in 1916. Indeed, Haig has been a controversial figure amongst historians ever since the end of the First World War, some seeing him as being out of his depth as a senior military commander, while others argue he was the man who won the war. The debate goes on to this day, with little sign...

March 13, 2016

Book Review | Wellington’s Redjackets: The 45th (Nottinghamshire) Regiment of Foot on Campaign in South America and the Peninsula, 1805-14 by Steve Brown (2015)

Titl

e: Wellington’s Redjackets: The 45th (Nottinghamshire) Regiment of Foot on Campaign in South America and the Peninsula, 1805-14

Author: Steve Brown

Publication Date: 2015

Publisher: Frontline Books

ISBN: 978-1-47385-175-7

The Peninsular War of 1808 to 1814 was, perhaps, the principal theatre of war during the wider Napoleonic Wars where Britain was able to make a significant contribution to the fight against Napoleon on land. Anyone with an interest in British history will have heard of the Duke of Wellington and his campaigns against the French in Portugal and Spain. Many will also have heard of the exploits of the legendary 95th Rifles or the almost equally famous 52nd Regiment of Foot, another light infantry unit. Numerous other regiments, of course, fought under the duke’s command during the campaign, many of which also have a rich an interesting history; yet so little is heard about them outside of official regimental histories or brief mentions in other works. Thanks to author Steve Brown, we can now learn much about the 45th Regiment of Foot, which clearly rates amongst some of the best in the Peninsula.

Although this title largely concentrates on the 45th in Portugal and Spain, the book begins with the regiment in South America, a theatre of war that still remains under-studied in the history of the Napoleonic Wars, thus offering the reader something more than just details of the fighting on the Iberian Peninsula. However, the story really begins when the regiment landed in Portugal in late 1808, after which the author chronologically examines the activities of the battalion, which remained in the Peninsula until the end of the war in 1814. (The book itself is separated into parts, each examining a full year of the war while being further subdivided into three to five chapters.) The 45th would take part in – or at least be present at – the battles or sieges of Rolica, Vimiera, Talavera, Busaco, Fuentes D’Onoro, Ciudad Rodrigo, Badajoz, Salamanca, Vittoria, Pyrenees, Nivelle, Orthes and Toulouse; making it one of the most experienced of Wellington’s infantry regiments by the time of Napoleon’s first defeat. One could even argue that the 45th should take pride of place alongside the legendary 95th Rifles and 52nd Foot.

Overall the book is extremely well written and enjoyable to read. It is packed full of detail and, although there are none of the usual illustrations or images, there are many useful maps. This book should appeal to anyone with an interest in the Napoleonic Wars, and especially those with a particular enthusiasm for the Peninsular War. It deserves five out of five stars!

March 8, 2016

New Book | Pathan Rising: Jihad on the North West Frontier of India 1897-1898 by Mark Simner – Now Available for Pre-order

Pathan Rising tells the story of the large-scale tribal unrest that erupted along the North West Frontier of India in the late 1890s; a short but sharp period of violence that was initiated by the Pathan tribesmen against the British. Although the exact causes of the unrest remain unclear, it was likely the result of tribal resentment towards the establishment of the Durand Line and British ‘forward policy’, during the last echoes of the ‘Great Game’, that led the proud tribesmen to take up arms on an unprecedented scale. This resentment was brought to boiling point by a number of fanatical religious leaders, such as the Mad Fakir and the Hadda Mullah, who visited the various Pathan tribes calling for jihad. By the time the risings ended, eleven Victoria Crosses would be awarded to British troops, which hints at the ferocity and level of bitterness of the fighting. Indeed, although not eligible for the VC in 1897, many Indian soldiers would also receive high-level decorations in recognition of their bravery. It would be one of the greatest challenges to British authority in Asia during the Victorian era.

Publication Date: 21 July 2016

Format: Hardback (272 pages)

Published By: Fonthill Media

January 25, 2016

The Sudan Military Railway: A Most Effective Weapon

Few people interested in the wars and campaigns of the late-Victorian period will have failed to come across Kitchener’s re-conquest of Sudan between 1896 and 1898. Indeed, the Battle of Omdurman remains one of the most well-known actions fought during the Queen’s reign, and it made the reputation of one of Britain’s best remembered generals. However, few are aware of the Sudan Military Railway, which was so vital to the winning of the campaign, and even fewer truly understand its significance as being the most effective weapon employed against the Mahdists.

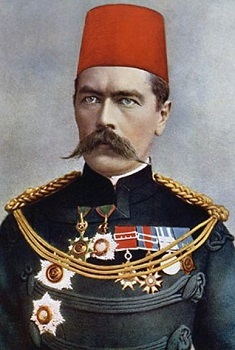

Major-General Kitchener, Sirdar of the Egyptian Army

Following the death of Charles ‘Chinese’ Gordon and the loss of Khartoum, Britain attempted to largely stay out of Sudanese affairs, showing a reluctance to confront the Khalifa and avenge the killing of their beloved general. After all, Sudan was an Egyptian problem and not one worth spilling the blood of British troops, who, inevitably, would be required in large numbers to wrestle control of the country from the fanatical Mahdists in order to restore it to Egyptian control.

A detailed account of how the British finally came to take the decision to re-conquer Sudan over a decade after its loss is beyond the scope of this short article, but needless to say the time eventually arrived when the Egyptian Government in Cairo, with the blessing and backing of the British Government in London, embarked on what would be a gradual and drawn-out operation to destroy the Mahdists and recover the lost territory. The campaign, which involved a number of actions and several major battles, effectively ended in success on 2 September 1898 at the Battle of Omdurman, although the Khalifa would not be killed until the following year. How, however, did the humble railway become key to this success?

As any student of military history will know, the issue of logistics is of paramount importance to winning any war or campaign. It is true that most are predominately drawn to the actual fighting aspect of military history, but there is usually a whole host of support mechanisms in place to supply and service the fighting troops, without which the latter could not realistically hope to operate successfully. The railway, built across Sudan, helped not only move the fighting men to and from the front, but it also kept them supplied with just about everything they needed. Traditionally in this theatre of war, supplies were transported on boats along the Nile or via camels across the desert, but the former was restricted by the numerous – and often impassable – cataracts, while the latter required an incredible number of animals to carry enough supplies to supply the 25,000 men who would eventually make up the Anglo-Egyptian army in Sudan.

The answer to Kitchener’s supply problems was, of course, to build a railway, but that in itself presented a number of huge problems that had to – one way or another – first be overcome. Firstly, many professional railroad builders in Britain believed that constructing a line across the Sudanese desert – terrain which was thought to be mostly sandy or rocky – would be totally unsuitable for the laying of track. Secondly, it was also thought that no sources of water would be found in adequate quantities in order to supply the thousands of workers required for such an ambitious project. Thirdly, no reliable maps were known to exist and so the intended route was an almost unknown. Fourthly, the territory through which the line would run was infested with hostile Mahdists, who were highly unlikely to stand and watch the invader get on with the construction unobstructed. Kitchener, however, had no intentions of letting such minor details stop him from building the line.

Kitchener turned to Édouard Percy Cranwill Girouard, a Canadian officer in the Royal Engineers who had a background as a railway builder with the Canadian Pacific Railways prior to his joining the army, after which he took charge of the Woolwich Arsenal Railway in Britain. Joining Kitchener’s expedition to Dongola in 1896, the engineer immediately set to work extending the existing line to Dongola, following the advancing troops as closely as possible. In this task he encountered a number of obstacles, chief amongst which was the poor quality of the workers at his disposal, most being unenthusiastic criminals. However, he managed to overcome his problems and greatly contributed to the success of the 1896 campaign.

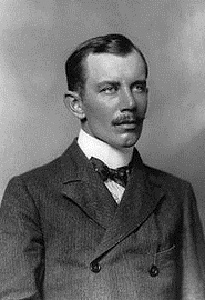

Édouard Percy Cranwill Girouard, Royal Engineers

Perhaps the real triumph of the railway, however, came in 1897 and 1898, following Kitchener’s extension of the campaign from merely occupying Dongola to the retaking of Khartoum itself, which lay much further south along the Nile. The plan was to build a new line from Wadi Halfa to Abu Hamed, which would greatly reduce the line of advance by about 330 miles, since the route would be direct and not follow the winds and bends of the Nile. Girouard even travelled back to Britain in order to find suitable locomotives, carriages and other equipment to build his railway, during which he met with Cecil Rhodes who agreed to loan him several engines for no fee.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Edward Cator of the Royal Engineers had conducted a survey along the intended route, and, to Kitchener’s delight, the terrain was found to be more suitable for the laying of track than had been previously believed. The lieutenant even identified several locations where water could be found in large enough quantities to sustain the workers as they built the line.

Work on the new line commenced on 1 January 1897, the surveyors marking out the route, after which the bankmakers followed, building embankments or otherwise cutting their way along the route. Next came the platelayers, who installed the wooden sleepers upon which the tracks were laid, followed by the spiking gangs, who would spike the tracks into place to ensure they did not move. Finally, the locomotives and the wagons could move along the line carrying their precious cargoes of men, supplies and equipment. The railway even carried a number of gunboats, which were broken down into sections then reassembled further up the Nile. Due to the cataracts and other obstacles, these vessels may not have been able to play the part they did in the campaign, but the railway allowed them to bypass the blockages.

Without the railway, Kitchener would had to have relied solely on the Nile and animal transport in order to move men and supplies from Egypt to the front. Such a reliance, even if realistically possible, would have resulted in a longer campaign and possibly a greater loss of life. It is, however, thanks to Kitchener’s forceful personality and the engineering talents of Girouard that such a seemingly impossible task was completed nonetheless. It truly was the most effective weapon employed against the Mahdists during Kitchener’s re-conquest of Sudan.

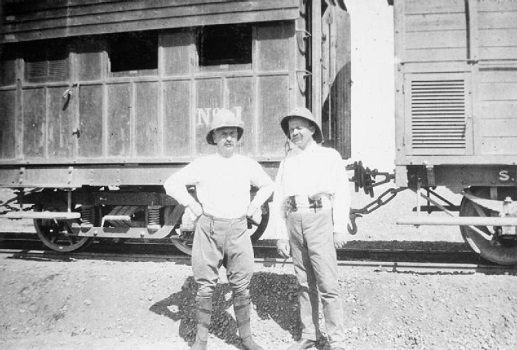

Kitchener’s intelligence officer, Colonel Sir Francis Wingate (left), in front of several trucks of the Sudan Military Railway

It is perhaps fitting to end this article with the words of Winston Spencer Churchill, who was present during the campaign in 1898:

‘In a tale of war the reader’s mind is filled with the fighting. The battle—with its vivid scenes, its moving incidents, its plain and tremendous results—excites imagination and commands attention. The eye is fixed on the fighting brigades as they move amid the smoke ; on the swarming figures of the enemy ; on the General, serene and determined, mounted in the middle of his Staff. The long trailing line of communications is unnoticed. The fierce glory that plays on red, triumphant bayonets dazzles the observer; nor does he care to look behind to where, along a thousand miles of rail, road, and river, the convoys are crawling to the front in uninterrupted succession. “Victory is the beautiful, bright-coloured flower. Transport is the stem without which it could never have blossomed. Yet even the military student, in his zeal to master the fascinating combinations of the actual conflict, often forgets the far more intricate complications of supply.’

January 12, 2016

Book Review | Death Before Glory by Martin R. Howard (2015)

Title: Death Before Glory: The British Soldier in the West Indies in the French Revolutionary & Napoleonic Wars, 1793-1815

Author: Martin R. Howard

Publication Date: 2015

Publisher: Pen and Sword Military

ISBN: 978-1-78159-341-7

The French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars are amongst some of the most written about events in history. Go into any good bookshop and you will not need long to find a shelf full of books on the subject. Yet despite this fact, you might find it difficult to find a book that focusses on the campaigns fought between the British and French in the West Indies, with most writings on the subject being relegated to a chapter at best in books with a wider focus. Author Martin R. Howard, however, has thankfully produced a work to help fill this glaring gap in the current literature.

As the subtitle suggests, this book specifically examines the experiences of the British soldier fighting in the West Indies from the beginning of Britain’s involvement in the French Revolutionary Wars to the final defeat of Napoleon in 1815. The book itself is split into three sections, the first of which briefly examines the opposing armies, including: the British Army battalions sent to the region and the professional French soldier along with his locally raised militias and other citizen warriors. The second section considers the actual campaigns themselves in detail, which took place in and around the West Indies almost continuously throughout the wars. Finally, the author concludes his work with a number of chapters that closely examine the personal experiences of those who fought in the campaigns, shedding much light on what it was like for the ordinary men who had to endure the hardships and terrors associated with service on the islands.

At the time of writing this review, Death Before Glory is one of two Napoleonic Wars related books written by Howard, the other being Walcheren 1809: The Scandalous Destruction of a British Army, itself another understudied aspect of the wars. Like his first title, this book is easy to read and packed full of detail, making it appealing to both the general reader and military history enthusiast alike. Due to the scarcity of works on this specific subject, it should be considered a must-read for those with a serious interest in the period. Overall, the book deserves a five out of five star rating.

December 15, 2015

Book Review | Wellington’s Engineers by Mark S. Thompson (2015)

Title: Wellington’s Engineers: Military Engineering in the Peninsular War, 1808-1814

Author: Mark S. Thompson

Publication Date: 2015

Publisher: Pen and Sword Military

ISBN: 978-1-78346-363-3

A number of good titles regarding the Peninsular War of 1808 – 1814 have been published over the years, but few – if any – have examined the role of the military engineers during the conflict. Yet, as any military expert will know, the presence of ‘scientific’ soldiers is essential to a successful campaign, whether it was one fought on the Napoleonic battlefields of over 200 years ago or those of today. With that in mind, this title from Mark S. Thompson is a particularly welcome addition to the current literature.

The author considers the work of the Allied engineers under the command of Sir Arthur Wellesley, the future Duke of Wellington, in a chronological order. That is, he begins in 1808 and examines each year in turn until the conflict’s end in 1814. As one might expect, all the British sieges of the Peninsular War are included, as are the issues of bridge building (and demolition) etc., but perhaps the main gem of this work is the chapter examining the Lines of Torres Vedras. The majority of books on the war mention this amazing feat of engineering, but few go into the depth that Thompson’s does. At the end of the title the reader is presented with a number of fascinating appendices that go into greater detail regarding certain aspects of military engineering, including: reconnaissance, surveying, bridging and education, amongst others.

Overall, Thompson has produced an excellent, scholarly piece of work that offers the reader a thorough analysis of Wellington’s engineers throughout the Peninsular War. The book is well-written and, despite its academic nature, easy to read. The only caveat the reviewer would place on this work is to recommend that the potential reader reads a general history of the war before this title, since Thompson focusses on the role of the engineers rather than the campaign itself, and prior knowledge of the conflict is beneficial. For those already familiar with the war, Wellington’s Engineers is a must-read. The book deserves a five out of five star rating.

November 26, 2015

Read my new article ‘Agent Garbo: The Chicken Farmer Spy’ on WW2 Nation

The British Double Cross System, active throughout much of the Second World War, was one of the most successful espionage operations of all time. One of its agents, a chicken farmer from Spain codenamed Agent Garbo, was a most unlikely spy. Yet his actions would have profound effects on the Allied invasion of France in 1944. Read more about his fascinating story on WW2 Nation.

November 10, 2015

FREE EBOOK | A Brief History of the Peninsular War by Mark Simner (2015)

THIS OFFER HAS NOW EXPIRED

My eBook, A Brief History of the Peninsular War, 1808-14, will be available to download free from the Amazon Kindle store from 11 November 2015 for 48 hours! The title can be found using the following links:

Amazon UK – http://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/B015Q8GSU6?keywords=mark%20simner&qid=1446204054&ref_=sr_1_2&sr=8-2

*For other countries please search your local Amazon site.

This is strictly a limited time offer, so do download your copy quickly before it reverts back to normal price!

“The Peninsular War, fought in Portugal, Spain and southern France between 1808 and 1814, was perhaps Britain’s most significant contribution to the fighting on land during the Napoleonic Wars. The conflict also saw Arthur Wellesley, who Napoleon would later deride as the ‘sepoy general’, make his name as one of Britain’s leading field commanders and become the Duke of Wellington. However, although often seen as largely a British struggle against the French, it should be remembered that both the Portuguese and Spanish played an equally important part in the eventual defeat of the emperor’s troops on the Iberian Peninsula.

“A Brief History of the Peninsular War examines the complex origins of the conflict before considering the key phases of the war, including: Wellesley’s first expedition; Moore’s failed campaign; the return of Wellesley and his campaign in Portugal; the war as it happened in Spain; and the climatic invasion of southern France. Although Napoleon’s first defeat in 1814 was arguably a result of fighting elsewhere in Europe, the Peninsular War, in the form of both major battles and the relentless guerrilla tactics of the Spanish, acted as an immense drain on the French Grande Armée. It truly was Napoleon’s ‘Spanish Ulcer’.”

November 2, 2015

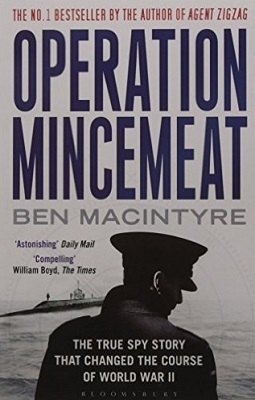

Book Review | Operation Mincemeat by Ben Macintyre (2010)

Title: Operation Mincemeat

Author: Ben Macintyre

Publication Date: 2010

Publisher: Bloomsbury

ISBN: 978-1-4088-0921-1

Operation Mincemeat was one of the most audacious deception operations of the Second World War. It was also one of the most bizarre, since it relied on the use of a freshly appropriated corpse that would be set adrift from a submarine in order to wash-up on a Spanish beach. Ultimately, it was also hugely successful, fooling the Germans into thinking that the main Allied thrust in the Mediterranean would not, as expected, come through Sicily but rather elsewhere. When the Allied troops, during the subsequent Operation Husky, eventually did storm ashore on the island of Sicily, they faced a much reduced German defensive force; and they had a dead homeless man to thank for their good fortune!

The story of Operation Mincemeat is perhaps best known from the 1956 film ‘The Man Who Never Was’, staring Clifton Webb, Gloria Grahame and Robert Flemyng, itself based on the book of the same name written by Ewen Montague. Montague himself was the real-life naval intelligence officer behind the deception, who, after the war, fought hard to be granted permission to make public the story of Mincemeat, However, at a time when the Second World War was still fresh in the memory of many, the published story was subject to many restrictions, since a number of characters involved in events continued to work in the shadowy world of secret intelligence.

Macintyre, writing almost seventy-years later, has painstakingly researched the true story of Operation Mincemeat and produced one of the most detailed and comprehensive accounts of the deception. No longer restricted by the need for secrecy, the reader is introduced to the complex planning of the operation and its subsequent execution and aftermath. The reader is also introduced to a cast of remarkable figures involved in the events, such as Montague and his fellow intelligence officer, Charles Cholmondeley. Perhaps most importantly, the star of the story, Glyndwr Michael, who in life accomplished so little but in death can be justly credited in having saved thousands of lives, is given the proper recognition he deserves.

The author has produced a highly readable account of this fascinating, yet sometimes morbid, true story of Allied deception. Indeed, it reads more like a novel than a history book, and should appeal to both the military history enthusiast and general reader alike. This title truly deserves a five out of five star rating!

October 28, 2015

Malta Spitfire EN199

The Malta Aviation Museum at Ta Qali houses a small number of interesting aircraft, predominately dating from the 1940s and 1950s, which, for a small fee, can be viewed by the visitor. One particular aircraft of note is EN199, a MK IX Supermarine Spitfire that was lovingly restored after it was damaged in a gale and subsequently subjected to souvenir hunters.

The aircraft itself was built in the UK in 1942, first taking to the skies in November of the same year. In early 1943, the Spitfire saw action in North Africa with No.81 Squadron, RAF, being flown by Wing Commander R. Berry DFC. A short while later, EN199 was sent to Malta from where it flew with No.154 Squadron based at Ta Qali, and conducted a number of missions in support of Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily. With the Allies firmly established in Sicily, the aircraft was relocated to the island from where it was operated by No.1435 and later No.255 Squadrons. Following the end of hostilities, it returned to Malta in October 1945, being used in a meteorological role flying from Hal Far. However, after later moving to the airfield at Luqa, EN199 suffered damage to its tail during a gale, forcing it to be removed from RAF service.

Fortunately, the airframe escaped being scrapped and was presented to the Malta Air Scouts on 27 May 1947. Sadly, the aircraft was subjected to souvenir hunters who illegally took parts to either sell or retain as keepsakes. It would not be until 1974, when Malta’s National War Museum was established, that attempts were made to salvage as much of EN199 as possible. Although it was intended to restore the Spitfire, the necessary skills and funding was not available at that time. However, in the early 1990s, a small but dedicated group of volunteers began a restoration project on the airframe, with the intention of bringing it back to static display condition. The work took over two and a half years to complete, and the restoration team had to find many missing parts, either through donations, purchase or even some rescued from under water Spitfire wrecks dotted around Malta.

Eventually, EN199 was fully restored and went on display in Valletta in 1995, just in time for the 50th anniversary of VE-Day. Since then, the aircraft has been moved to the Air Battle of Malta Memorial Hangar at Ta Qali, where she can be seen today alongside Hawker Hurricane Z3055.