Kim Hooper's Blog, page 35

September 18, 2016

The importance of reading for writers

This post isn’t going to say what you think it’s going to say. You probably think it’s going to say that I think writers should read all the classics and all the award winners and all the “important” books. But I don’t believe that to be true.

I’ve always been a reader. I hesitate to say “avid reader” because there are chunks of my life when I didn’t read much at all, for one reason or another. In college, for example, I read a book for pleasure every other month or so. I was too busy reading stuff for school. But, I can say that I’ve always written, even if it was just journal entries at the end of long days.

I like writing more than reading (just slightly). And, even though I read 60+ books a year now, I don’t think it’s necessary for writers to be extremely well-read. I think it’s more necessary for writers to write as much as they can, to find their own voice and exercise that voice, and to read books that interest them (and watch TV and go to movies and visit museums and listen to music…and all those other things that can contribute to a writer’s creativity just as much as books can).

This isn’t to say that I think reading isn’t helpful. Of course it is. The rhythm of others’ sentences inspires me. I stumble upon similes that make my jaw drop and make me want to push harder with my own writing. Sometimes, the structure of a book will inspire me–the way the story plays with time or is told from multiple points of view, for example. Sometimes, the voice of a character in another book will encourage my own. Catcher in the Rye did that for me in high school. I had to read that book to know that such a narrator was possible, that such a tone was possible. That first line remains one of my favorites:

“If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.”

If I’m honest (and why wouldn’t I be honest on my own blog), there are a number of “great” works I’ve never read. Here are some, off the top of my head:

Anything by Proust

Anything by Chekhov

Infinite Jest

Harry Potter (not a single one of the books, sorry)

Moby Dick

Middlemarch

Robinson Crusoe

Ulysses

All the King’s Men

Anything by Cormac McCarthy

Crime and Punishment

War and Peace

Anything by John Updike

I feel insecure when I read interviews with other writers who talk about their greatest influences and name novels I would consider a chore to read. A conversation with an overachieving MFA student is enough to make me feel downright stupid. But, life’s too short to be something I’m not. I love contemporary, not-too-literary fiction. My influences are writers like Tom Perrotta, John Irving, Michael Chabon, Liane Moriarty, Maggie O’Farrell, Jeffrey Eugenides, Brady Udall, and Jhumpa Lahiri. I wonder if people claim to dislike reading because they associate it with the books they were forced to read in high school (Just the mention of Beowulf makes me shudder). There is a whole world of books out there. And a whole world of writers with different interests. I can’t help but see that as a good thing.

The post The importance of reading for writers appeared first on Fiction Writing Blog.

September 5, 2016

Writing without a goal

People told me that once I published a book, I’d have to be careful not to let “the industry” distract me from my love of writing for the sake of writing. I didn’t think this would be a problem for me, but it has been.

Before publishing a book, I wrote the stories I wanted to write, without thinking about what my agent or editor or “the market” wanted. I just wrote. And, because I’d been rejected so many times, I didn’t really concern myself with the outcome. I hoped I’d get published one day, but I didn’t obsess about it.

Now that my debut is out there, I’m thinking, “OK, now what? What’s next?” My book deal was for the one manuscript. During the year-and-a-half-long phase of waiting for PEOPLE WHO KNEW ME to be published, I wrote other books, but my editor isn’t interested in those, which is disappointing, but not that shocking. Lots of writers say it’s even harder to get your second book published than your first. There are a couple different reasons for this. One, your first book didn’t do well enough, so your publisher isn’t motivated to give you a second deal. Or, two, your book did well, so your publisher wants you to write something that’s very similar to it (which isn’t always easy).

I started to desperately brainstorm ideas, bombarding my husband with them on a nightly basis. I had completely forgotten what I WANTED to write. I was just concerned with what other people wanted to read. This started to make writing seem not fun at all.

I’m back to my roots, writing what I want to write, with no outcome in mind. In fact, the project I’m working on now (the memoir-ish thing I mentioned a few posts back) makes no real sense from a career perspective (since I’m a fiction writer). Even though it may not be the most strategically sound project to dedicate myself to, I feel the need to write it, so I am. Maybe it will get published some day, or maybe writing it will open me up to write my next novel (which may get published or may lead to another novel). It doesn’t matter. I just need to write what I want (or need, rather) to write. Plain and simple.

I’ve also decided that I’m setting aside Sundays for writing. I’ve been lacking in time (and brain energy) lately because my job has been very stressful. I’m tired of jotting down ideas on Post-its and watching the Post-its collect in a pile. I need to set aside structured time for writing. I’m not usually that formal or disciplined about my writing, but I need to be now. I wrote for six hours yesterday and it was glorious. Sorry, in advance, to people who want to hang out with me on Sundays.

P.S. Happy Labor Day, everyone! I saw “The Light Between Oceans” today with my mom. It followed the book closely, but I still like the book more. It remains one of my all-time favorites. If you saw the movie, what did you think?

The post Writing without a goal appeared first on Fiction Writing Blog.

August 13, 2016

What it’s really like to publish your first book

It’s weird. Let me start there. It’s very weird.

The thing is, I’ve dreamed of publishing a novel since I was a little kid. It was the quintessential pie in the sky. My first attempts at making the dream a reality began in my early twenties. The rejection (from agents and publishers alike) made me want the damn thing even more (this may be related to my last post about how writers are crazy masochists). And now, in my mid-thirties, it finally happened.

I thought it would be life changing. But it’s not. Or, at least, not in the ways I imagined. There have been pleasant surprises. But there are realities of publishing that I didn’t know before (and wish someone had explained to me so I was more prepared).

A writer friend of mine sent me this essay by Jade Sharma entitled “The Terrible, No Good, Very Bad Day I Woke Up As a Debut Author.” An excerpt:

My best friend calls.

–Dude, I finished your book in one sitting. It’s so good. I’m really proud of you, she says.

–I’m glad you liked it.

–This must be a big day for you.

–I don’t know. I’m scared.

–What are you scared of? she asks.

–I’m scared that this is the part of the movie where the credits roll.

It’s true that I don’t feel as bad as last week. Not as useless. Jenefer Shute told me, Everyone’s first book is an act of desperation. But I still feel desperate. What do I need—money? Is it attention? Hey, everybody, look at what I can do. I’m super good at making up people and their stories. And then I write it alone in a room and then people go home and read it alone in a room. It’s so fucking weird. Is this a big deal? Is this not a big deal?

See, I’m not the only one who thinks the whole thing is WEIRD. Here are 12 things I’d say to a debut author:

1. You have very little control. People ask me if I designed the cover and I find that hilarious. Not just because I’m a terrible artist, but because big publishers have specific people dedicated to covers and the author just comes in at the last moment to say, “OK, looks good.” I love my cover, but I had nothing to do with it. In general, there is so much going on in the background at the publishing house to determine how your book will be positioned in the marketplace that, ultimately, is out of your hands. People ask me why my book is in some stores and not others. I don’t have an answer, except to say, “That’s what was decided.” Certain books have a ton of marketing dollars behind them, others don’t. It’s not up to the author. Usually, the bigger the advance, the more marketing dollars (because the publisher is trying to sell as many copies as possible to rationalize the amount of the advance).

2. Launch day will be surreal. It will feel like you’re in a dream when you see your book in a store, or when you start getting reviews on Amazon and Goodreads. You won’t be able to grasp it or put words to it (which is weird for you because you’re a writer).

3. Avoid reading reviews. Someone gave me this advice and I did not take it. I’ve gotten mostly positive reviews, and I’ve received nice Tweets and Facebook messages from readers as far away as Australia. Those make my day, but I pay more attention to the negative feedback. I’m drawn to the mean reviews like flies to shit (there’s that masochism again). You have to take it with a grain of salt (and a shot of tequila). People have their opinions for their own reasons. Whatever you do, do not respond to the mean reviews. I actually tried once and Goodreads had a canned message that popped up and said something like, “Are you sure you want to do that?” Good call, Goodreads.

4. Don’t worry about the money. Because, honestly, there isn’t much money in it (unless you get extremely lucky). I’ve heard of the huge advances. I know they’re out there. But most writers don’t get them. And, frankly, getting a big advance has very little to do with the pure quality of the book and more to do with current market trends and connections (which brings me back to #1). The original idea of an advance was to give the author enough cash to focus on writing. Now, most advances could pay a few months’ worth of living expenses. People say, “But you earn money on every book, right?” No. You have to “pay back” your advance first. So, if each book costs $20, you get $2 of that (10% is standard for a hard cover). But it goes toward your advance. So, if your advance was $20,000, you’d have to sell 10,000 books to “pay back the advance” before earning royalties (and when you do earn royalties, it’s $2/book). There are books that take off and sell millions of copies (Girl on the Train, for example), but most don’t. All this is to say that my co-workers should stop asking when I’m quitting my day job.

5. Don’t worry about sales. It’s unlikely you’ll have any idea how sales are doing anyway. I wish I had a t-shirt that said, “No, I don’t know how sales are doing,” because this is the first thing anyone asks me if they haven’t seen me in a few weeks. I have no idea. I’ve been told that Amazon posts some numbers, but those aren’t very accurate. I wouldn’t advise looking at those. The publisher will send me statements of how many copies are sold, but they are on a 3-month delay, so I will get back to you in November. I could probably beg my agent or editor for sales figures, but I think they would be annoyed and I don’t know what good it would do to know.

6. The book probably won’t become a movie, sorry. When I explain #4 to people, they say, “But it could become a movie!” This is the dream, right? Well, it’s not that easy or common. It’s possible that an interested party will option your book (which pays $1,000-$3,000 on average and allows them a certain amount of time to try to secure a studio for production). If they find a studio (and that’s a big IF), that’s when some money rolls in, but we’re still talking high five figures (low six figures if you’re lucky). And even if a studio is behind it, it doesn’t mean it will necessarily get made. Lots of uncertainty with this movie thing.

7. Don’t worry about future book deals. I always assumed that one book would open the door to several others–a lifetime of published novels! Not necessarily. Because of the state of the book industry, publishers are very particular about what they buy these days. Your first book has to do pretty well to get a second deal from the same publisher. At the very least, it has to “earn out” the advance. And if your first book does well, they will want your second book to be very similar to that. You have to not worry about all that and just write what you want to write. Not every book you write may be published, but chances are you will get a second deal eventually. It may be with a different publisher or a different book. The need for persistence does not stop just because you get one book published. There is no resting on laurels unless you are Stephen King.

8. You will feel like you need an assistant. There is a lot of publicity an author can do, especially on the local level, to get the book out there. But it’s very time consuming. I find this work much harder than writing. You want to network with other writers, reach out to bookstores and libraries, set up interviews, etcetera. If you’re a writer, these things probably aren’t in your nature. I hate self-promotion, and I hate the necessity for it even more. But, often, you have to do it because nobody else is going to do it for you.

9. Professional publicity may be a wise (and expensive) investment. The publisher will have someone in house to help with publicity, but the rumors are that person is usually also working on multiple other books. That’s where an outside publicist comes in. They can cost anywhere from $2,000 to $3,000 per month. I put all of my advance toward publicity. Interestingly, my biggest review, in the Wall Street Journal, was organic. For whatever reason, the WSJ writer picked my book out of a stack on her desk and reviewed it. Still, I’d say you should risk the investment in publicity because if your debut doesn’t do well, that can close a lot of doors.

10. There’s a lot of waiting around. Publishing moves very slow. The time between sending the book out and getting a deal is long (if a deal even happens). The time between getting a deal and the launch of the book is at least 18 months. Things don’t turn around in days, or even weeks. It takes months. It’s good to remember this with advance payouts, too. You get a third of the advance upon signing a contract, a third after the book is done (which could be months later), and a third when the book launches (which could be a year later). So, even if someone gets a big six-figure advance, that money is doled out over many months (or years).

11. It’s a marathon, not a sprint. Will this writing thing be a career? Can you make a living? There are success stories of this happening for debut authors, but most writers put in many years (and many books) before they are somewhat secure. People forget that Gillian Flynn wrote other books before Gone Girl (and Gone Girl took a while to take off, too). Overnight sensations are not the norm (and, if you are an overnight sensation, I’m assuming that comes with its own pressures and issues).

12. Enjoy the moment. It’s easy to get discouraged and disillusioned with the realities of the industry. Publishing is a business, after all. It’s not as romantic as it seems. But, getting a book on the shelves is a big deal. That’s part of you, out there in the world, forever. No matter what your advance was or what your future is, enjoy the moment. Enjoy the enthusiasm of your friends and family. Enjoy your launch events. Enjoy those messages from readers who loved your book. I started a scrapbook, with everything from my signed contract with St. Martin’s to the email from my editor with the book cover to photos of my readings to newspaper clippings. You’ll want to remember this. It’s all a blur, so find a way to record it so you can savor it later.

The post What it’s really like to publish your first book appeared first on Fiction Writing Blog.

August 2, 2016

Why writers are crazy masochists

On Sunday, I was scrolling through Facebook (never a good thing), and thinking about how most people spend their time on weekends. For most people, those days off are dedicated to fun, letting loose, getting out and about (or, that’s what Facebook implies). For me, weekends are a little angst-ridden. I struggle with how much to work on my writing (because weekends are the only time I have for that) and how much to enjoy life (because YOLO and FOMO and all those other acronyms that annoy the hell out of me).

This helped me realize something: WRITERS ARE NUTS. Most people seem to see happiness as the primary objective of life. I seem to value struggle. My mom says this is related to my Puritan ancestors. Perhaps my value of struggle is why I became a writer; or perhaps being a writer made me develop this value (because, honestly, if you don’t value struggle, you can’t be a writer. It’s like someone wanting to be a jockey without a horse).

I’m not saying that writers aren’t happy. I’m a generally content person. But so much of a writer’s life can be fraught. Here’s what I mean.

1. The act of writing itself is difficult. In an interview with Vice, author Joy Williams said, straight up, “Writing gives me no happiness.” I can’t say I agree with that, wholeheartedly, but I know what she means. There are days when everything is flowing and the story is surprisingly thrilling. That makes me happy. But, most days aren’t like that. I relate it to running. I have some runs that feel like I’m jumping on clouds, but most feel like I’m slogging through mud wearing weighted boots. Come to think of it, you must also value struggle to be a runner.

2. You always feel like you have no idea what you’re doing. There is so much self-doubt through the solitary process. You keep going because of the rare moments of, “Wow, maybe I have something here.” Anne Lamott says it best in Bird by Bird when she writes about the radio station KFKD (“K-Fucked”) and how it plays “the endless stream of self-aggrandizement” in one ear, and “rap songs of self-loathing” in the other.

3. But you must write. I don’t write for joy, though sometimes (on the magical days), joy is a result of writing. Mostly, writing is a need. Sometimes, it’s an obligation, the way an itch needing to be scratched is an obligation. I write because I have to. If I don’t, my brain feels like it will explode.

4. Unless you can write full-time, you will constantly feel like your brain is about to explode. Most writers are strapped for time, because they have regular jobs and commitments and responsibilities. I have so many ideas in my head and there is this constant, chronic unease because I’m physically unable to sit and bring those ideas to life. I’m always lamenting the lack of time. My brain never feels quite peaceful.

5. You have to sacrifice lots of “fun” things. Most weekends, I try to leave the majority of at least one day completely open so I can write. Preferably, both days are open. This means I miss out on fun things sometimes. But, what are you gonna do? If I don’t make the sacrifice and dedicate the time, bad things happen (ie, brain explosion).

6. The luxury of writing full-time is very rare. It just is. Elizabeth Gilbert says she didn’t quit her other jobs until Eat, Pray, Love took off. She’d written other books before that, but they couldn’t pay the bills. This is the reality for most authors.

7. Writing does not pay much. We all hear about huge advances, but the majority of writers are not making a real living off writing. Well-meaning people ask when I’m going to quit my day job and I laugh. I tell them, “Oh, I’m taking a loss on this book” and they think I’m joking. I tell them I’m serious and they looked confused. Most advances aren’t huge, and paying for things like your website and publicity and all of that is expensive. Hannah Gersen, in an interview with The Millions, says, “The culture’s really focused on making money…For me, I’m barely breaking even.” Yep, that’s how it goes.

8. You are part of a supposedly-dying industry. Everyone says fiction readers are a dying breed. This is really depressing because I am wired to write novels. I can write other things, but novels are what I love. I’ll always write them, but I suppose I may not have many readers at some point. There should be a support group for novelists, blacksmiths, and the creators of Nintendo games.

9. You are a sensitive soul in a really insensitive business. Publishing is tough business. There is so much rejection–form letters with zero emotion from uninterested agents, emails from publishers who “unfortunately need to pass” (for various obscure reasons), and snarky reader reviews on Amazon and Goodreads. Writers are very private people and it can often feel like too much (for me, at least).

10. You can’t quit the business. Trust me, I’ve thought about it. But, I will always write (see #3) and, as I do, I will feel that pull to publish for the sole purpose of sharing stories with others. It’s my introverted way of connecting.

So, like I said, writers are nuts. I always come back to this Dorothy Parker quote:

In all seriousness, though, I continue writing because it would cause me more angst to stop. If you love writing, do it. But do it for the joy of the process, not for any outcome. How’s that for today’s Buddhism lesson?

The post Why writers are crazy masochists appeared first on Fiction Writing Blog.

July 29, 2016

Flirting with nonfiction

While waiting for feedback on my idea for a second book, I’ve been working on something…different. I don’t know what it is yet, exactly. Meaning, I don’t know if it’s destined to be an essay or a book. But, I do know that it’s nonfiction, memoir-ish. I didn’t plan to work on something like this; it just kind of seemed right. It began with keeping notes, like a journal. I used to write in a journal religiously. As a little kid, I kept stacks of diaries in fire proof safes; as an adult, I confined my thoughts to Word documents that I emailed to myself for safe keeping. Then I stopped journaling all together. Life got busy, and I felt like writing and analyzing my thoughts was making me ruminate too much. In short, I started to annoy myself.

But, I can’t seem to deny that writing is my way of figuring out who I am, how I feel. It’s my way of making sense of things. In the past few years, so much has happened in my personal life that has necessitated attempts at sense-making. My husband and I have been through so many trying things together. We feel like elderly people. It’s only in the last few weeks that I’ve wanted to sit and write about it. Before then, we were in the thick of it. I had no perspective. I have some perspective now.

Writing reality is scary. There is something much safer about fiction. Fiction allows for a lot of hiding. Nobody really knows what parts of stories are rooted in truth, and which parts are completely imagined. And it’s not my responsibility to clarify. When in doubt, I can fall back on this blanket statement: “It’s fiction.”

With essays or memoirs, hiding is not possible. You’re just…out there. I’ve been reading a lot of memoirs lately, with a different appreciation for the brave honesty of the authors. In the past, I didn’t think too much about that. The authors were strangers to me, so their deepest, darkest confessions may as well have been those of a fictional character. But, now, I realize they are real people, with family members and friends who are suddenly privy to their private lives. And, when the anonymous haters on the Internet make comments, it’s decidedly more personal.

I could tuck away the past few years’ events in fictional stories–and I probably will do that, too–but it seems necessary to write about those events directly, as a way to reach out to anyone who is going through similar things and say, “It happened to me. I’m a real person, not a character. You’re not alone.” That, to me, is the beauty of nonfiction. It’s therapy for the author and the reader, a direct communication, no beating around the proverbial bush.

I’ve written a few personal essays (here and here, most recently), and putting them out in the world made me far more nervous than putting my fiction into the world. There’s that desire to crawl under a rock. I might get cold feet tomorrow about this new project and run back to the warm hug that is fiction. It is enough, for now, to say that I’m flirting with nonfiction, with complete honesty. If the relationship develops beyond flirtation, I will let you know.

The post Flirting with nonfiction appeared first on Fiction Writing Blog.

July 19, 2016

The daunting outline

When you want to get your first novel published, you have to submit the entire manuscript for consideration. Nonfiction is different in that you can get a book deal based on a detailed proposal. I always envied this. But, now, as I’m working on pitches for various ideas for my second novel, I’m realizing the difficulties.

The way it works is that I can submit a few sample chapters and an outline to secure a second book deal with my publisher. I consider this the Loyalty Clause of the contract. They’ve worked with you before, they know what they’re getting into, so they don’t need the whole book to make a decision. If you leave your publisher and go elsewhere, you’re back to square one, submitting the whole manuscript.

What’s difficult for me as I consider pitches for a second novel is that I don’t often know how a story is going to turn out until I write it. The sample chapters are easy. But asking me to summarize exactly how the characters and plot are going to evolve beyond those chapters, and how the story will eventually end, gives me anxiety. I DON’T KNOW. I JUST DON’T KNOW. For me, the not knowing is the beauty of the thing. For my publisher, not knowing is probably cause for concern.

In the July/August issue of Poets & Writers, Benjamin Percy wrote a piece titled “Superpowered Storytelling,” in which he discusses how he has to turn in outlines for the comic books he writes.

He writes:

“I have to hand in a rough skeleton of every issue for editorial approval. I blueprint my novels as well, but not so strictly as this. I like to know the end, know the major set pieces, know how the characters might change, and then improvise the rest, caught up in the emotional thrust of composition. So I fought this requirement at first, saying that it felt inorganic, a left-brain imposition on a right-brain process. But here’s the thing: I’ve never followed any of these outlines, not in a paint-by-numbers sort of way. Once I start writing, I always change things around, and no one ever complains. The editors just want to feel assured that I’m going in the right direction. And that’s how I now feel: assured. I’ve learned to enjoy the process of outlining, treating it like a rehearsal or a sparring match before the big fight. A way to get limber, excited, confident. Which is far preferable to staring at the white oblivion of an empty document, not knowing where to go next or blindly chasing a five-page scene that ends up deleted.”

This helped change my perspective on outlines. Maybe I don’t have to feel trapped by them. Maybe they don’t have to be the ball and chain in my love with writing. And, maybe, they don’t have to be perfect (gasp). It’s freeing to know that Percy deviates from his outlines. They aren’t contracts; just guides. I still think they’re annoying, and they aren’t natural for me at all. But, they’re a necessity in this business–just one more thing I’ve learned in the last few months.

Here is some proof that I’m not alone in my disdain for the outline:

“I do not outline. There are writers I know and count as my friends who certainly do it the other way, but for me, part of the adventure is not knowing how it’s going to turn out.” — Joyce Maynard

“I don’t make outlines or plans because whenever I do, they turn out to be useless. It is as if I am compelled to violate the scope of any outline or plan; it is as if the writing does not want me to know what is about to happen.” — Leslie Marmon Silko

“Outlines are the last resource of the bad fiction writers who wish to God they were writing masters’ theses.” — Stephen King

And then there are those who love outlines:

“Outlining is the most efficient way to structure a novel to achieve the greatest emotional impact. The most breathtaking prose and brilliantly drawn characters are wasted if the plot meanders and digresses. Outlining lets you create a framework that compels your audience to keep reading from the first page to the last.” — Jeffery Deaver

“I write an outline for a book. The outlines are very specific about what each scene is supposed to accomplish.” — James Patterson

“I found out that if you make an outline you’re much less likely to get blocked when you get into the middle of the story.” — Rick Riordan

If you’re a writer, do you outline? Why or why not?

The post The daunting outline appeared first on Fiction Writing Blog.

July 13, 2016

The state of the book

Every now and then, I feel the need to do a post about the state of publishing. Are books really dying? It’s hard for me to believe because I LOVE books and cannot imagine life without them. But, it appears that many people can totally imagine life without them. According to a 2015 survey by the Pew Research Center, 27% of adult Americans had not read a book within the past year. Not one book. I have one word for this: YIKES.

In 2015, the publishing industry was driven by sales of adult coloring books and memoirs by YouTube stars (marketed to tweens). When I heard this, I was depressed–not only because I write novels, but because I love to read novels. I know how publishing works. They want to pump out more and more of the one thing that’s selling. Which means more YouTube memoirs and coloring books. And fewer novels. Once again: YIKES.

But, then I read Michael Taeckens’ interview with Carolyn Kellogg (book editor of the Los Angeles Times) in Poets & Writers magazine. Here’s her take on the coloring books and YouTube memoirs:

“As long as people are turning to books from different age groups, for divergent reasons, publishing has reason to be optimistic.”

Now that’s a good way to look at it.

The thing is that publishing (and writers) have to adapt. It’s actually quite fascinating that the novel has remained in the same basic form for all these years. Other forms of entertainment (movies, magazines, video games) have changed pretty drastically.

The world we live in now is FULL of content, for better or worse. If you want an escape, you don’t need to seek out a good book. There’s the Internet, with cat videos and blog posts and episodes of TV shows you missed. Reading a book is an investment of focused time, and most people have less and less focused time. The e-book format helps. E-books are less intimidating than hardcovers, I think. It’s a screen, which is what most people are used to these days (again, for better or worse). It’s easily transportable. Personally, I like hardcovers, but I also still own CDs.

With the influx of content, more people saying they are “so busy,” and the shortening of attention spans, how is the traditional novel going to survive? Right now, there are enough of us pre-Internet-ers who still read books, but what about when we’re gone? In his acceptance speech for the Los Angeles Times Innovator’s Award, James Patterson said, “Book publishing…badly, badly needs to innovate.”

Patterson, along with his longtime publisher Little, Brown, is introducing BookShots, which are short, fast-paced novels under 150 pages, priced below $5, and available in paperback and e-book formats. I think this is a brilliant idea.

Here’s what I know: People will always love stories. Here’s a hard truth: The way stories are served up may need to change. And readers need help wading through the choices to find a book they’ll actually like. Nothing is more demoralizing for a tentative reader than reading a book that’s “not their thing.” As for writers, maybe we need to keep modern day pressures in mind when writing. Shorter chapters, shorter books, enough story suspense to keep pages turning. I’m not talking about traditional “suspense,” like what you find in a spy novel. I’m not saying that the only books that will sell are Gone Girl remakes. I’m talking about sustaining interest in characters and plot so the reader really wants to know what’s going to happen next. Readers don’t want meandering. Here’s what Bill Robinson, editorial director for BookShots and Little, Brown, said:

“We’re trying to take out parts that people skim. It should feel like reading a movie.”

I think they’re on to something.

The post The state of the book appeared first on Fiction Writing Blog.

July 4, 2016

Why you don’t want to be friends with a writer

I hate prioritizing. Or, rather, I hate having to prioritize. I frequently fantasize about a stress-free life with wide open spaces of time to gradually tackle everything on my life to-do list. The key word in that sentence: fantasize. The reality is that I have a very busy day job, meaning the only “free time” I have is on weekends (and isn’t exactly “free” thanks to errands and other things required of adults).

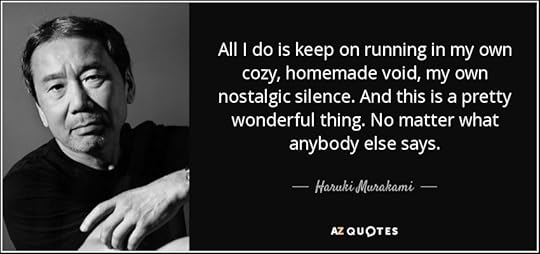

I’ve been stressed out trying to balance everything. I keep making dramatic declarations like, “Something’s gotta give.” I recently read Haruki Murakami’s memoir, What I Talk About When I Talk About Running (because reading and running are just a couple life passions that compete with writing when I do have free time). This book made me love Murakami even more than I already do. He’s a self-declared morning person with introverted tendencies who enjoys the peace of long runs. I GET YOU, man. I GET YOU. He dedicates some time in his book to discussing the need to prioritize when you’re a writer, and why it can lead to having no friends:

“I’m struck by how, except when you’re young, you really need to prioritize in life, figuring out in what order you should divide up your time and energy. If you don’t get that sort of system set by a certain age, you’ll lack focus and your life will be out of balance. I placed the highest priority on the sort of life that lets me focus on writing, not associating with all the people around me. I felt that the indispensable relationship I should build in my life was not with a specific person, but with an unspecified number of readers. As long as I got my day-to-day life set so that each work was an improvement over the last, then many of my readers would welcome whatever life I chose for myself. Shouldn’t this be my duty as a novelist, and my top priority? My opinion hasn’t changed over the years. I can’t see my readers’ faces, so in a sense it’s a conceptual type of human relationship, but I’ve consistently considered this invisible, conceptual relationship to be the most important thing in my life. In other words, you can’t please everybody.”

Of course, Murakami and I differ because his “unspecified number of readers” is, like, millions of people. I think I have a couple thousand (I don’t know, really. This article explains why). Point is, people understand if Murakami has to shut away the world and write. He has a globally-recognized purpose. I don’t. I have my personal sense of purpose (which I expect to matter to exactly nobody) and I try to balance that with my equally-strong desire not to piss off my loved ones. But, Murakami is right: You need a system in place if you want to write books. Book-writing doesn’t just…happen.

In my radio interview with Laguna Talks, the host asked my husband what it’s like to live with a writer. My husband, caught off guard, said something like, “Great!” He’s so cute. The reality is that it’s probably not that great. Writing takes a lot of time. Being with a writer is like being with a marathon runner. There are days when you have to do your thing and say, “Ok, bye, see you in a few hours.” Writing also takes a lot of mental energy. I talk about it often. I wrestle with characters and plot points, and I tend to verbalize the struggle with the same drama as a sports commentator. I’m sure this progresses from entertaining to annoying very quickly.

My “system” involves being very particular about my weekends (weekdays are out of the picture. I’m lucky to get a lunch break at my job and I’m exhausted by the time I get home). On Saturdays and Sundays, I try to schedule things for later in the day, after I’ve written, or leave entire days completely open (if I’m on a deadline or completely obsessed with a certain project). This doesn’t always work out perfectly, of course, but it’s the only system that sort of works and results in me actually writing. I know it bugs my family and friends. They probably think I’m rigid, but, frankly, I won’t write another book if I’m not rigid. Is this an appropriate time for that obnoxious “sorry not sorry” hashtag? I don’t do hashtags.

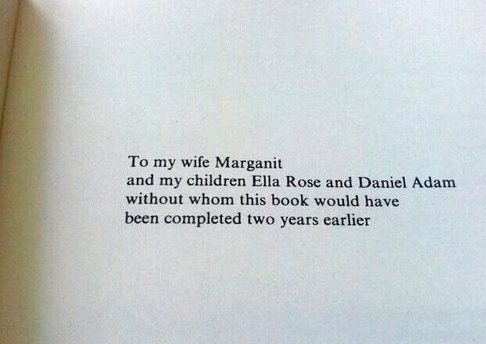

As this 3-day weekend comes to an end, I lament the fact that I didn’t write a thing (besides this blog post, which is of questionable quality). It’s a holiday weekend and I’m supposed to be celebrating independence, so I guess I can use those as excuses. The truth is life got in the way, and sometimes that’s okay. It reminds me of this hilarious book dedication:

I don’t even have children to blame. Neither does Murakami. Murakami also doesn’t have a day job (a fact he states with immense gratitude). I guess we all have our things that “get in the way.” After all, writing wouldn’t be writing if it didn’t involve a little strife and a lot of procrastination.

The post Why you don’t want to be friends with a writer appeared first on Fiction Writing Blog.

June 20, 2016

The nonfiction in fiction

I’ve done a handful of radio and newspaper interviews since my book came out (I have one tonight, actually), and every single person has asked me if the book (or its characters) are based on real life. The truth is simple: No.

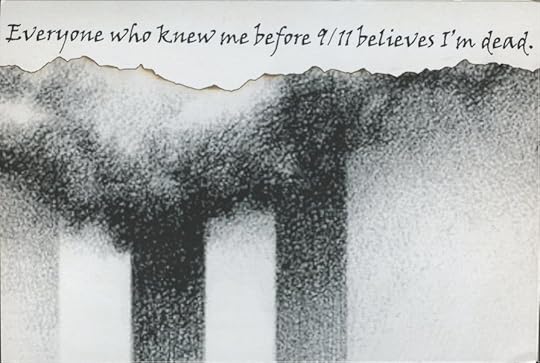

The core of PEOPLE WHO KNEW ME is fiction, in the truest sense. I did not fake my death on 9/11 and move to California. I do not know anyone who did this. The story was inspired by a couple random things that collided in my psyche. Years after 9/11, I heard about people who faked their deaths for insurance payouts. Then, I heard that one of the most common fantasies people have is leaving behind their current life and starting a new one. My book was already underway when I came across this on Post Secret:

It haunted me because it echoed the words of the character I had created. Very weird, right?

But, even though the core of the novel was from my imagination, there are parts of “me” in the story. For example, as I wrote in essays for Redbook and Psychology Today, I gained insight into caregiving when my husband was taking care of his mother and, yes, that experience informed the narrative in the book. My husband and I are nothing like Drew and Emily, but I could see the potential difficulties for couples. Drew and Emily are young and alone, they have no help, they struggle financially, their communication is poor, and they live in a country that doesn’t offer easy access to caregiving resources. This is a perfect storm of events that leads Emily to the dramatic decision she makes on 9/11. I can’t say I would have made the same choices as her. But I can see how a human being would make those choices. I was intrigued by her flaws and fantasies.

In this way, it’s hard to say if fiction is ever really fiction. Obviously, an author’s thought processes and sense of humor and life perspective are baked into paragraphs. My best friend read my book and said, “I felt like I was talking to you, even though none of this is real. It’s weird.” It is weird. If you know me, you can see how the book is “mine.” There are a few similarities to my own life (I work as a copywriter at an ad agency, as does Emily; I’m a runner, as is Emily), but beyond that, the story has my voice. It is very obviously… me.

This excerpt from Ann Patchett’s This is the Story of a Happy Marriage explains it better than I can:

“What exactly is a made-up story? I used to take a great deal of pride in the fact that people who read my novels, even all of my novels, wouldn’t really know anything more about me or my life at the end of them than they had known when they started. I’ve written novels about unwed mothers in Kentucky and a black musician in Memphis. I wrote about a gay magician in Los Angeles and a hostage crisis in Peru. The amount of real knowledge that I had on any of these subjects would weigh in about as substantially as an issue of People magazine. In my books, I make up the experiences and the characters, but the emotional life is real. It is my own. I think this is probably true of most novelists. The bright-green space alien with three heads and seventeen suctioning fingers in the latest science-fiction novel may be unrecognizable as a human, while in fact having the same emotional composition as the author’s mother.”

“What exactly is a made-up story? I used to take a great deal of pride in the fact that people who read my novels, even all of my novels, wouldn’t really know anything more about me or my life at the end of them than they had known when they started. I’ve written novels about unwed mothers in Kentucky and a black musician in Memphis. I wrote about a gay magician in Los Angeles and a hostage crisis in Peru. The amount of real knowledge that I had on any of these subjects would weigh in about as substantially as an issue of People magazine. In my books, I make up the experiences and the characters, but the emotional life is real. It is my own. I think this is probably true of most novelists. The bright-green space alien with three heads and seventeen suctioning fingers in the latest science-fiction novel may be unrecognizable as a human, while in fact having the same emotional composition as the author’s mother.”

I admit that, as a writer and reader, I always wonder what parts of books are rooted in some reality (or emotional life, as Patchett describes). After I finished reading Gone Girl, I Googled Gillian Flynn to see if she was married. I was afraid for her husband, quite frankly. She is married, by the way, and he is still living, as far as I can tell. Clearly, I’m just one more person who likes to wonder if the author is the protagonist (even though I find myself constantly explaining that I’m not the protagonist in my book). Recently, Jessica Knoll, author of Luckiest Girl Alive, went public about how she was gang-raped, which is a big part of the story line in her novel (though she also makes it clear that the book is not a memoir in any way). Authors like her link their books to their personal lives. At the other end of the spectrum are authors like M.L. Stedman (The Light Between Oceans, one of my favorite books), who has said she doesn’t share how her own experiences influenced her story because she wants readers to care about the characters, not her.

I read fiction with the assumption that it’s inspired by something in the author’s life, even if the narrative is nothing at all like the author’s life. I understand and respect Stedman’s perspective, but it is fun to hear how stories originate, mostly because it gives me a glimpse into the process for other writers. But, even if an author can pinpoint a couple key personal events that informed their story, the author’s inner life is that mysterious thing that makes no two books the same. It’s that inner life that readers connect with. That, in my mind, is the magic of literature.

The post The nonfiction in fiction appeared first on Fiction Writing Blog.

June 15, 2016

The writer’s fraudulence complex

In the April issue of Poets & Writers, Leigh Stein wrote a piece called “Poet, Writer, Imposter” that had me nodding along vigorously.

She starts:

“To begin with, my credentials are worthless. I’m no expert. A better writer should have gotten this assignment. My editor is ignoring my e-mails because my work is unpublishable and she’s just trying to find the nicest way to tell me. I’m not that talented. I’ve just been lucky, and what will I do when that luck runs out?

Does any of this interior monologue sound familiar? If so, you may be suffering from impostor phenomenon, which is the name for those sneaky feelings of inadequacy despite actual evidence of professional success.”

Ok, so, are there meetings for people with this issue? Because I will raise my hand with gusto and say, “My name is Kim Hooper. And I suffer from impostor phenomenon.”

The launch of People Who Knew Me has been incredibly surreal. I’ve been more emotional than I expected I would be. People have been so supportive and enthusiastic, saying things like, “We’re so proud of you” and “This is such an achievement.” And I keep thinking, “It’s not that big of an achievement. It’s just a book. Lots of people write books. Have you been in Barnes & Noble? There are, like, a million of them. I just got lucky to be in some Barnes & Noble stores. I’m not even in all of them.”

Then I go and read some of the more negative reviews on Amazon or Goodreads, as a masochistic way of convincing myself that the aforementioned thought process is valid.

What the heck is this about?

In her piece, Stein talks to Sherry Amatenstein, a licensed clinical social worker and author. Amatenstein says, “the whole process of writing is so fraught because unfortunately it is so much about what other people think.” Then: “Artists are always waiting for the next rejection, or the next person to like them.”

Incidentally, the May/June issue of Psychology Today also had a piece on this topic–“Captives of the Mind” by David Kessler.

Kessler hones in on David Foster Wallace and his suicide in 2008 at the age of 46. He writes:

“Contradictory impulses–yearning for greatness yet feeling like a fake with every new achievement–pushed him further into himself…Wallace was haunted by the ‘fraudulence complex,’ as he called it… As an adult, he was always on high alert, sensitive to signs of the beguiling impostor that, though he must have known exists in all of us, he could not allow for himself.”

“Any number of things could threaten his sense of credibility: critical praise, academic success, romantic attention, somebody laughing at his jokes. These were all land mines and, prompted by them, Wallace felt an immediate split between how he was perceived and who he really was. In such moments, his life became a lonely performance.”

Steve Bunney, professor emeritus of psychiatry at Yale, pointed out that “it’s not uncommon for successful people from all walks of life to feel a similar kind of distress. Research has shown that highly accomplished people often report the feeling of being a fraud. Many successful people grow concerned, as Wallace did, that if people really knew them, they’d realize they weren’t deserving of their achievements.”

How ironic that it’s the most successful people who feel least so. In any case, it’s comforting to know that this is a common issue. I’ve talked to co-workers at my ad agency who echo a similar sentiment (eg, “One of these days, someone’s going to find out I don’t know what the hell I’m doing”). Maybe this type of complex is what drives people to produce better and better books/paintings/whatever (and, sometimes, drives them crazy, simultaneously). It’s like they’re thinking, “That other success was fraudulent, but this next one will be (and feel) real.” Chasing the proverbial dragon, as they say.

It seems unlikely that creative people can stop feeling this way. But I think the key is continuing to do what we do despite feeling this way.

This is all new to me. It’s overwhelming. I feel extremely self-conscious and vulnerable with my book “out there,” subjected to opinions (positive and negative). There is just so much chatter now, thanks to the Internet and social media. I’m constantly questioning praise, instead of basking in it. I may never feel comfortable basking in it, but I will enjoy a few celebratory glasses of champagne and keep writing, no matter what.

The post The writer’s fraudulence complex appeared first on Fiction Writing Blog.