Rosa Jamali's Blog, page 2

March 23, 2019

The Clock Cell

Something happens to die

And the sunlight which has been soaking is wet and obscure

If I carry on the lines

The frozen object which has been captured in your hands will drop

Otherwise, the day has come to an end.

Void

When I get home; staring at all those cubical shapes;

Standstill current of water

And the sunlight which is never damp

On the blank sheets of writing

bursting into tears over old sheets on my bed.

The elements

Its essence has been painted by my blood

The rain of cats and dogs on my field

The moon is encompassing the land!

Here with the frostbite on the iron post,

I left the time on the river bank

Time was a whim slipped away from my fingers

The moments have been cleaned and cleared.

The wall has turned blue

Me and the black gown

Have taken the flow of the river.

It's a calf death breast-fed.

What is it?

Sediments on a neutral background

It could be in a different colour

It's been many days since I started walking on the rope

The creased moon is hanging down the ceiling.

Blizzard

A flimsy stone

The frostbite on the window glass

The bridge has fallen down

Silence on a metal tape

Ending to a blind full stop.

(TRANSLATED FROM ORIGINAL PERSIAN TO ENGLISH BY ROSA JAMALI)

Published on March 23, 2019 01:52

March 19, 2019

Introduction

Rosa Jamali is a renowned poet in contemporary Iran; she is often considered as the most important female figure in Post-revolutionary Persian literature.

She studied Drama at the Tehran University of Art; later she received her MA degree in English Literature from Tehran University.

Her debut collection of poems, " This Dead Body is Not an Apple, it is either a Cucumber or a Pear" , was published in 1997 and announced a major new voice in Iranian poetry. The book opened Persian poetry to new creative possibilities. Her second collection of poems " Making a Face" was well received by critics and established her literary career. In this collection, with its stream-of-consciousness narrative poems; she merges different types of discourse and registers – archaic, colloquial and written, formal and informal, journalistic or scientific and so on... She adopts a kind of music from classical Persian poetry and imbues that with the natural cadence of speech, juxtaposing long and short sentences, infusing the whole with her bitter and distinctive sense of humour.

Her third collection " Making Coffee To Run a Crime Story" is a re-reading of Sadegh Hedayat’s Blind Owl in a post-modern narrative.

The lengthy dramatic poem at the beginning of book retells the image of misogyny in Hedayat's literature; the chopped off woman in the blind owl. The poem has got frequent references to bible, myths & characters." Here Gravity is Less" is a collection of her short avant-guard pieces on urban life and " Dating Noah's Son" , a collection with so many biblical themes. The book " The Hourglass is Fast Asleep" has been mentioned for combining a present-day setting with the myths and themes of Persian mystics. Like Suhrawardi she takes the philosophy of illumination to talk about life from an Eastern Perspective; a kind of cosmology in which all creation has taken an existence from the light of lights; a kind of unification with the heaven above. In this book, she writes on death & love as Omar Khayyam did so many years ago. The book has been widely discussed in its mythological references through birth and rebirth cycle, vegetation deity and archetypal patterns. And " Highways Blocked" , her recent poems are much more in the political scene of present-day Iran.

She has written a number of poetry reviews, critical articles, and scholarly essays... In an article on 'Ahmad Shamlu's poetry, she says:

' Shamlu is a part of our cultural heritage, but we are from a different generation so we have to criticise the past:

1- Shamlou's poetry is a political speech.

2-The music he creates in his poetry comes from fragmenting the phrases which cannot be real music where else he applies the classical kind of rhythm which is not used in modern literature.

3- The archaic style he applies can't utter today's life throughout poetry.

4- In his love poems, he describes his lover as a nurse, mother or a paragon of patience which cannot be practical in real life.

5-He applies the eloquence of the 11th-century prose which sounds obsolete and old-fashioned now.

Rosa Jamali's poems have been translated to various languages; English, French, German, Swedish, Turkish, Italian, Dutch & Esperanto... Among her translators are the distinguished Rumi Scholar, Franklin Lewis, and British acclaimed poet and prominent scholar of THE BOOK OF KINGS, Dick Davis.

She has translated a number of English poets into Persian among which are Yeats, Sylvia Plath, Carol Anne Duffy, Adrienne Rich, Beat poets, John Ashbury, and some recent poets, ...

'The shadow ' is a play by Rosa Jomali. The police are seeking for a murderer, a woman but he's found eleven women resembling the murderer. The setting is a room. There are two women in black, covered their hair in black headscarves confronting in a shelter. They were born on the same day and they've got one name. They both married a man called Parviz.

A challenge of identity let them kill each other. In the end, a third woman exactly like them enters the same room, finding a piece of paper: 'The police have arrested 13 women who are quite alike but two have been found dead.'

She has also collaborated with Franklin Lewis in

the English Translation of Ghazaleh Alizadeh's 'The House of Edrisis'.

She has appeared in different literary festivals and sessions worldwide. She delivered a talk on " Iran in writing" at the British Library in Feburary 2015 following a Panel Discussion with Ahmad Karimi Hakkak and Daljit Nagra.In Gutenburg poetry festival(2013) she has talked about the image of contemporary Iranian women in Literature. She has been a guest poet in different Persian study centre in the United States like Chicago University, Colombia University, Iranica Centre, UCLA, University of Arcansas, Meriland university, George Washington University, Library of Congress and... India's Asian biennale of poetry(2019) is among her recent contributions.

" The Forbidden City" , which is her next collection of poetry, is under print now.

Many of her poems have been translated by herself.

Rosa Jamali's Works:

This Dead Body is not an Apple, it's either a Cucumber or a Pear(1997)

Making a Face(1978)

Making Coffee to Run a Crime story(2002)

The Sand Glass is Fast

Asleep(2011)

Highways Blocked(2015)

The Shadow (a play)

The Forbidden City(2019)

Anthology of English poets translated into Persian(2019)

She studied Drama at the Tehran University of Art; later she received her MA degree in English Literature from Tehran University.

Her debut collection of poems, " This Dead Body is Not an Apple, it is either a Cucumber or a Pear" , was published in 1997 and announced a major new voice in Iranian poetry. The book opened Persian poetry to new creative possibilities. Her second collection of poems " Making a Face" was well received by critics and established her literary career. In this collection, with its stream-of-consciousness narrative poems; she merges different types of discourse and registers – archaic, colloquial and written, formal and informal, journalistic or scientific and so on... She adopts a kind of music from classical Persian poetry and imbues that with the natural cadence of speech, juxtaposing long and short sentences, infusing the whole with her bitter and distinctive sense of humour.

Her third collection " Making Coffee To Run a Crime Story" is a re-reading of Sadegh Hedayat’s Blind Owl in a post-modern narrative.

The lengthy dramatic poem at the beginning of book retells the image of misogyny in Hedayat's literature; the chopped off woman in the blind owl. The poem has got frequent references to bible, myths & characters." Here Gravity is Less" is a collection of her short avant-guard pieces on urban life and " Dating Noah's Son" , a collection with so many biblical themes. The book " The Hourglass is Fast Asleep" has been mentioned for combining a present-day setting with the myths and themes of Persian mystics. Like Suhrawardi she takes the philosophy of illumination to talk about life from an Eastern Perspective; a kind of cosmology in which all creation has taken an existence from the light of lights; a kind of unification with the heaven above. In this book, she writes on death & love as Omar Khayyam did so many years ago. The book has been widely discussed in its mythological references through birth and rebirth cycle, vegetation deity and archetypal patterns. And " Highways Blocked" , her recent poems are much more in the political scene of present-day Iran.

She has written a number of poetry reviews, critical articles, and scholarly essays... In an article on 'Ahmad Shamlu's poetry, she says:

' Shamlu is a part of our cultural heritage, but we are from a different generation so we have to criticise the past:

1- Shamlou's poetry is a political speech.

2-The music he creates in his poetry comes from fragmenting the phrases which cannot be real music where else he applies the classical kind of rhythm which is not used in modern literature.

3- The archaic style he applies can't utter today's life throughout poetry.

4- In his love poems, he describes his lover as a nurse, mother or a paragon of patience which cannot be practical in real life.

5-He applies the eloquence of the 11th-century prose which sounds obsolete and old-fashioned now.

Rosa Jamali's poems have been translated to various languages; English, French, German, Swedish, Turkish, Italian, Dutch & Esperanto... Among her translators are the distinguished Rumi Scholar, Franklin Lewis, and British acclaimed poet and prominent scholar of THE BOOK OF KINGS, Dick Davis.

She has translated a number of English poets into Persian among which are Yeats, Sylvia Plath, Carol Anne Duffy, Adrienne Rich, Beat poets, John Ashbury, and some recent poets, ...

'The shadow ' is a play by Rosa Jomali. The police are seeking for a murderer, a woman but he's found eleven women resembling the murderer. The setting is a room. There are two women in black, covered their hair in black headscarves confronting in a shelter. They were born on the same day and they've got one name. They both married a man called Parviz.

A challenge of identity let them kill each other. In the end, a third woman exactly like them enters the same room, finding a piece of paper: 'The police have arrested 13 women who are quite alike but two have been found dead.'

She has also collaborated with Franklin Lewis in

the English Translation of Ghazaleh Alizadeh's 'The House of Edrisis'.

She has appeared in different literary festivals and sessions worldwide. She delivered a talk on " Iran in writing" at the British Library in Feburary 2015 following a Panel Discussion with Ahmad Karimi Hakkak and Daljit Nagra.In Gutenburg poetry festival(2013) she has talked about the image of contemporary Iranian women in Literature. She has been a guest poet in different Persian study centre in the United States like Chicago University, Colombia University, Iranica Centre, UCLA, University of Arcansas, Meriland university, George Washington University, Library of Congress and... India's Asian biennale of poetry(2019) is among her recent contributions.

" The Forbidden City" , which is her next collection of poetry, is under print now.

Many of her poems have been translated by herself.

Rosa Jamali's Works:

This Dead Body is not an Apple, it's either a Cucumber or a Pear(1997)

Making a Face(1978)

Making Coffee to Run a Crime story(2002)

The Sand Glass is Fast

Asleep(2011)

Highways Blocked(2015)

The Shadow (a play)

The Forbidden City(2019)

Anthology of English poets translated into Persian(2019)

Published on March 19, 2019 04:00

March 4, 2019

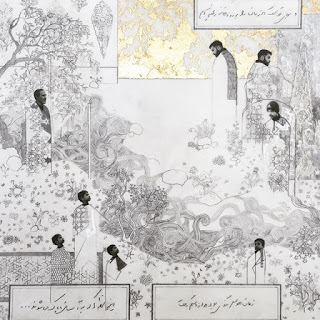

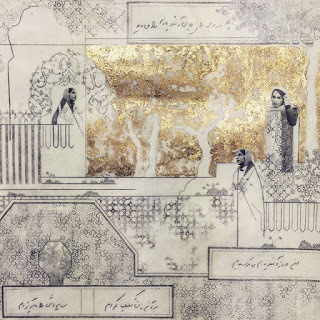

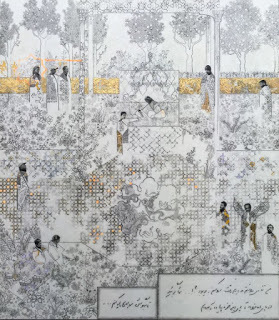

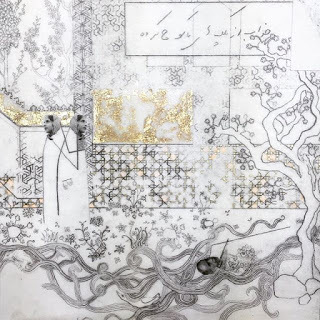

I left my name on the Land I stepped

A collaborative project with English painter Charlie Calder-Potts to illustrate this timeless narrative and its themes. She has taken people from the ‘here and now’ on the streets of Iran and placed them within the context of Persian Poems of Rosa Jamali.

Check more,...

Published on March 04, 2019 06:13

March 3, 2019

The Biennial of Asian Poetry

Published on March 03, 2019 14:26

Knotweed - Poem by Rosa Jamali

I've turned to an annual plant, shielded and armed, from the genus of hollyhocks and broad leaves

Whole five-thousand-year history is turning over my head

It was the moment that you were buried with no shroud

And I'm the weeds and icicles of this land, …

Had been climbing over the flames, it was a black ladder, burning my sole feet

It was the moment that I had chopped my heart, you had sucked my blood in that woundless bowl

Had been growing like a wildflower, had been living for millions of years

In Syriac over my body:

Nail-shaped herbs had written some letters.

I'm the genius of thorns with wounded heels of thousands of miles travelling in the oasis

My blistered feet, weary and my parched lips

Shattered by the mountain ranges I had been fighting with my claws

My roots are extended with the fluent liquid in the vessels

Lilacs had grown over my arms and now I've turned to the ivy as if burning in the fire

I left my name on the land I stepped, …

And who's this weeping human child, lamenting two thousand years in my arms? Still weeping? ! Always weeping? !

I've been raising this child for six thousand years

I've grown this Persian hero to send him to the battlefield

Breastfed him

And he has grown out of my eyes

This extreme light which has blinded me….

(TRANSLATED From original Persian to English by the Poet)

Published on March 03, 2019 14:26

April 16, 2016

Ecology and Environment in Persian Poetry / By Rosa Jamal...

Ecology and Environment in Persian Poetry / By Rosa Jamali (India; Green Life Organization; December 2015)

Abstract:

1

Nature has always been a major theme in Persian Poetry. Persian Poetry pays a great tribute to Persian Mythology. Creation seems to have been taken place through a process of metamorphoses of natural resources, vegetation, flora and fauna. This has made a great influence on Persian Poetry. In Khorasan School Manuchehri Damghani depicts autumn and describes death and rebirth cycle in a very popular poem. In THE GREAT BOOK OF KINGS, Ferdowsi always describes gloomy scenes as if the earth is not going to revive itself. Later in the Poetry of Hafiz and Rumi, nature creates lots of metaphors in reference to Islamic mysticism. In Modern Persian Poetry Nimā Yushij who lived a whole life in the countryside of Northern Iran describes nature very strongly while Sohrab Sepehri takes the initial step to get close to a sort of belief: the manifestation of God in the nature and creating a sacred halo around the environment,…

2

As Plato said poets recreate nature by imitation and modelling it as the major source of beauty so that the description of pure nature and the Garden of Eden is just found in poetry, poets preserve the untouched, pristine and serene nature this way. It’s a calamity when poets see the destruction of life cycle in the nature. Mother Nature is represented in poetry as an archetype so is the birth and death recycle. A poet insists on nurturing and raising what has been missed or ignored over the centuries to survive and maintain the energy sources of the planet earth

3

Based on Persian mythology there could exist a literary theory; quite close to ecofeminism; for Chista and Anahita have been depicted as wise and insightful Goddesses who play significant roles in nature's elemental forces whereas in Greek Mythology Medusa and Pandora have been described as sources of evil and destruction. I'd like to discuss that there could be a sort of rebirth in ecofeminism in Persian poetry, quite representative to what has already existed in our racial cultural and historical background and in reference to a sort of Manichean aesthetics,… this says that feminine writing cares much about nature and keeping it safe; feminine writing is in conflict with death, mass murder, genocide and abortion of beings ; Birth and Rebirth archetype and Mother nature could strongly appear in feminine writings, how can this type of writing dispense with slaughter and extinction of some species of nature,..?!

So that Persian feminine writing could present quite a unique point of view in this respect;..

4

In the visionary writings of many Persian mystic poets for instance the followers of illumination like Sheikh Shahabuddin Suhrawardi ; there exists a kind of transcendental view towards the nature. Mystical Visionary writings have been written in harmony of a life which could transcend you to the heaven. This life which is quite peaceful and has been practiced through the time, the path is not an easy one. You need to go through seven steps to become a real mystic; a sort of alchemist and reach to the kingdom of God which is called Malakut. You need to forget greediness and gluttony through fasting, you'll forget lust and temptations through a secluded lifestyle and you feel much closer to God by repeating holy verses, this makes you a better human being, a spiritual medium and a peace keeper.

5

Masnavi Manavi is a principle text for the seeker of a better life, getting to know about enlightenment, then the basic steps you need to take to see the world through the lens of a Suffist, through Persian wisdom and a divine ladder,. Sonnets of Rumi which I include them in occult reading give you a sense of Ecstasy and euphoria what makes you dance till you drop. That specific dance being a long-time ritual is called Sama ; you'll become a different human being with Godly characteristics which help you to get to know to the kingdom of heaven, now you need to forget your earthly ambitions.You need to forget temptations and set a limit on your needs and wants. At last you'll get united with the whole universe, this step is called Malakut; by reading Masnavi in a holy place which is called Khanqah and taking its advice in your daily life, you'll become a selected human being; blessed with God and a heavenly guardian which paves your way to the kingdom of heaven.

6

Deconstruction made the literary theory quite easy, there is no binary opposition of nature/ man; so that there's no grand narrative. Wild life can be created in poetry with no preconception. Nature makes and creates itself in a primitive process. All these mention that human being is no longer the ruler of nature, the one who was supposed to be THE KING for a lengthy time,…

7

The idea has been very much inspired by advise letters to the kings of Persia before Islam; how to become a good and just ruler by hard practice and a kind of mental exercise, so great kings grow with Godlike features which have been bestowed upon them and being granted by heavenly inspirations; they need to follow the principles of good deeds, good thought and good speech.

The story of Zahhak in Persian national epic" THE GREAT BOOK OF KINGS", is a very dark myth, a critical turning point. Persians were vegetarians before that, the cook persuades the king to eat meat and the king enjoys the taste. Later the cook prepares the brains of human being as a delicious meal and consequently snakes as symbols of evil grow on his shoulders. The king becomes a corrupt and this is the most oppressive era of history for such a nation of strong beliefs!

Abstract:

1

Nature has always been a major theme in Persian Poetry. Persian Poetry pays a great tribute to Persian Mythology. Creation seems to have been taken place through a process of metamorphoses of natural resources, vegetation, flora and fauna. This has made a great influence on Persian Poetry. In Khorasan School Manuchehri Damghani depicts autumn and describes death and rebirth cycle in a very popular poem. In THE GREAT BOOK OF KINGS, Ferdowsi always describes gloomy scenes as if the earth is not going to revive itself. Later in the Poetry of Hafiz and Rumi, nature creates lots of metaphors in reference to Islamic mysticism. In Modern Persian Poetry Nimā Yushij who lived a whole life in the countryside of Northern Iran describes nature very strongly while Sohrab Sepehri takes the initial step to get close to a sort of belief: the manifestation of God in the nature and creating a sacred halo around the environment,…

2

As Plato said poets recreate nature by imitation and modelling it as the major source of beauty so that the description of pure nature and the Garden of Eden is just found in poetry, poets preserve the untouched, pristine and serene nature this way. It’s a calamity when poets see the destruction of life cycle in the nature. Mother Nature is represented in poetry as an archetype so is the birth and death recycle. A poet insists on nurturing and raising what has been missed or ignored over the centuries to survive and maintain the energy sources of the planet earth

3

Based on Persian mythology there could exist a literary theory; quite close to ecofeminism; for Chista and Anahita have been depicted as wise and insightful Goddesses who play significant roles in nature's elemental forces whereas in Greek Mythology Medusa and Pandora have been described as sources of evil and destruction. I'd like to discuss that there could be a sort of rebirth in ecofeminism in Persian poetry, quite representative to what has already existed in our racial cultural and historical background and in reference to a sort of Manichean aesthetics,… this says that feminine writing cares much about nature and keeping it safe; feminine writing is in conflict with death, mass murder, genocide and abortion of beings ; Birth and Rebirth archetype and Mother nature could strongly appear in feminine writings, how can this type of writing dispense with slaughter and extinction of some species of nature,..?!

So that Persian feminine writing could present quite a unique point of view in this respect;..

4

In the visionary writings of many Persian mystic poets for instance the followers of illumination like Sheikh Shahabuddin Suhrawardi ; there exists a kind of transcendental view towards the nature. Mystical Visionary writings have been written in harmony of a life which could transcend you to the heaven. This life which is quite peaceful and has been practiced through the time, the path is not an easy one. You need to go through seven steps to become a real mystic; a sort of alchemist and reach to the kingdom of God which is called Malakut. You need to forget greediness and gluttony through fasting, you'll forget lust and temptations through a secluded lifestyle and you feel much closer to God by repeating holy verses, this makes you a better human being, a spiritual medium and a peace keeper.

5

Masnavi Manavi is a principle text for the seeker of a better life, getting to know about enlightenment, then the basic steps you need to take to see the world through the lens of a Suffist, through Persian wisdom and a divine ladder,. Sonnets of Rumi which I include them in occult reading give you a sense of Ecstasy and euphoria what makes you dance till you drop. That specific dance being a long-time ritual is called Sama ; you'll become a different human being with Godly characteristics which help you to get to know to the kingdom of heaven, now you need to forget your earthly ambitions.You need to forget temptations and set a limit on your needs and wants. At last you'll get united with the whole universe, this step is called Malakut; by reading Masnavi in a holy place which is called Khanqah and taking its advice in your daily life, you'll become a selected human being; blessed with God and a heavenly guardian which paves your way to the kingdom of heaven.

6

Deconstruction made the literary theory quite easy, there is no binary opposition of nature/ man; so that there's no grand narrative. Wild life can be created in poetry with no preconception. Nature makes and creates itself in a primitive process. All these mention that human being is no longer the ruler of nature, the one who was supposed to be THE KING for a lengthy time,…

7

The idea has been very much inspired by advise letters to the kings of Persia before Islam; how to become a good and just ruler by hard practice and a kind of mental exercise, so great kings grow with Godlike features which have been bestowed upon them and being granted by heavenly inspirations; they need to follow the principles of good deeds, good thought and good speech.

The story of Zahhak in Persian national epic" THE GREAT BOOK OF KINGS", is a very dark myth, a critical turning point. Persians were vegetarians before that, the cook persuades the king to eat meat and the king enjoys the taste. Later the cook prepares the brains of human being as a delicious meal and consequently snakes as symbols of evil grow on his shoulders. The king becomes a corrupt and this is the most oppressive era of history for such a nation of strong beliefs!

Published on April 16, 2016 09:06

November 19, 2015

The Angles Of The Frame (Translated From Original Persian To English by the Author) By Rosa Jamali

1

Many years have passed since the day,

I looked into a mirror, saw a wrinkled face.

I've been disclosed to the bulging sands of my bed.

2

Aeons of breath account for the many veins in my atrium.

3

The bull I breast-fed for many years

And I've submerged into the frame.

4

I knew the justifications were hard,

Hard as against the current of water.

No news from the ambiguous points

something uncommon.

It can't be justified by natural rules,

many years we've been tangled on it.

5

This usurped land is a part of all buried treasure islands

No finger points in any direction.

Lost in the dead-end alleys

Tracing images without a compass.

6

Horse pounding pulse sing endlessly in my blood.

My kinsmen of horses…

Blood-line linked as to rays of a circle

like roots of a tree growing deep on the roof.

7

You can't stop the hands of the clock.

You can't come back to the broken minutes.

The days have been arranged one after another.

The knights have left the game one after another.

8

There was a straw mat where you fell asleep.

I became numb, quite used to the stillness of the house.

9

Was something supposed to get away from the core

to join us?

A century has passed and we still live in this house.

10

Dimensions have shifted

Not exclusive to the roof

The letters approved us as the residents of the house

They ran away as the convicts

And we got used to the standstill.

Published on November 19, 2015 12:16

April 26, 2015

THE STREET BEFORE YOU LEAVE TEHRAN / Rosa Jamali / Translated from original Persian to English by Franklin Lewis

Facing the airport,

all that’s now left in my grasp

is a crumpled land

that fits in the palm of my hand

Facing the wavering sunbeams

of a sun that is cross and will not speak with us.

All the way from the salt sands of Dasht-e Lut,

it came, a dream that made my fingers shift,

that set my teeth on edge, a muted breeze,

a whirlwind

spun from the sand dunes

all the way through the back alley of our house.

Pasting together the cut up fragments of my face to make me laugh?

A short leap, no longer than the palm of the hand,

exactly the length you had predicted

A huge grave

in which to lay the longest night of the year to sleep

“Sleep has quit our eyelids for other pastures,

has dropped its anchor at the shores of garden ponds

has lost the chapped flaking of its lips,

poor thing.”

Pasting together the cut up fragments of my face to make me laugh?

With scissors – snip, snip – they’re cutting something up.

The alphabet shavings strewn on the ground,

are they the letters of our name?

With every other zig-zag,

rigid and unyielding,

in the middle of the salt dunes, flat and vast,

did you cage my mother’s breath,

her footprints fading

in the shifting sands?

Pasting together the cut up fragments of my face to make me laugh?

No!…

I will not return to the last street.

I left behind a shoe, one of a pair, for you to put on and follow after me

A strange shape forms

facing the horizon…

It fits in the palm of the hand!

A big leap, beyond what three legs could manage,

the length of the palm of the hand.

"From Poetry Anthology of Metropolitan Museum of Art"

Franklin Lewis is associate professor of Persian in the department of near eastern languages and civilizations at the University of Chicago. His books include:

- Rumi: Swallowing the Sun (Oneworld, 2007)

- Rumi: Past and Present, East and West (Oneworld, 2000)

-Things We Left Unsaid: Zoya Pirzad, Translated from original Persian by Franklin D. Lewis (Oneworld, 2013)

Published on April 26, 2015 07:15

How I turned to become an experimental poet:

My talk at the British Library:

1

At the first step when I started my literary career the job was totally challenging for the range of set vocabulary was limited and not too many poets could generate a new style and create new metaphors or revitalise the themes used in Persian classics. I was born one year before the revolution and I grew up at the time of Iran-Iraq war, growing up at the most critical moment of Iran’s history made me a totally different person with a critical view towards the past and present. I usually create new metaphors facing the new subject matters of our society. Besides I felt that we need some new techniques to be much more creative, like narrating a poem through different voices or mingling a formal and informal language.

2

I’m from a generation living in a different milieu far from the classics and with a vague prospect of future for the mass immigration of Iranians. As a patriot there is a strong sense of local colour in my poetry with recurrent themes: Tehran has often been described as a lover, a metropolis with noise and pollution and massive highways, my concerns with the land and reminiscing the past have been expressed through the kind of condensed and language-based imagery I generally apply, allusive to our history.The outcome of such a hectic and traumatic background is that our fears and dreams are different from the generation past. They used to be hopeful,they used to have big goals, they believed in utopias and revolutions but they're all senseless to us and we’re obsessed with the trivial matters, I never judge the situations I usually describe in my poetry, I would let the reader feel and get it between the lines.

3

One of my main concerns is to revitalise the techniques of the past through some layers of intertextuality, there was a sort of writing in the past which was called visionary writing, it’s true to the essence of poetry, with a high sense of intuition to discover life by being through a mystic vision, a sort of trance-like state.In a comparative study the method could be taken as a sort of automatic writing which was a favourite of surrealist poets. I’m a lot influenced by this sort of writing in which you need to discover the unconscious side of the language or create the moment of being as Heidegger says. I still think that sufism is the main trend in Persian poetry which could be recreated through the objects within our everyday life.

4

Being obsessed with archetypes,I’ve been much inspired by a trend of mysticism in poetry which embodies the elements of nature and sees the manifestation of God in the nature and its harmony, a kind of phenomenological approach being seen in the visionary writings in which the boundaries like rhymes and rhythms haven't been considered, what matters is getting united with the whole universe through the words.I like the diction because it's far from the cliches and not so much repetitive as it is in mystical sonnets. In mystical sonnets the cup-bearer has always been taken as a medium of spirituality; as a result a certain terminology have been created and applied for centuries.Unlike the sonnets in the visionary writings like the diary and letters of mystics the writer is free to apply any word he likes, whether inside the poetics or not, it doesn't matter much. I’ve also been inspired by Persian mythology and I usually mingle that within a modern atmosphere.The book of the kings contains mythological imagery which is quite appealing and surrealistic to my mind.

Iran in Writing: Past and Present

British Library, February 2015

Daljit Nagra, Rosa Jamali, Ahmad Karimi Hakkak, Shadab Vajdi, British Library's Speaker

Published on April 26, 2015 07:09

April 14, 2013

Ghazaleh Alizadeh's novel THE HOUSE OF THE EDRISIS to be published ...

Excerpts from THE HOUSE OF THE EDRISIS /Translated & prefaced by Rosa Jamali

Ghazaleh Alizadeh(1947-1996)

THE HOUSE OF EDRISIS

A Novel by Ghazaleh Alizadeh

Original language: Persian

Translator to English: Rosa Jamali

Number of pages:757 pages in Persian

First publication: Tirajeh, 1991

Type of novel: Dystopian, river-novel (roman-fleuve), Allegory

Season 1: Ashkhabad

Chapter one

The turn-out of a misfortune in a household is not all of a sudden, in the wooden cracks, on the sheets, throughout the hatchways and in the pleats of curtains, the dust covers everything longing for the wind to release the scattered constituents of a lurking-place.

In the house of Edrisis, life was going on; the engraved wall clock with the covered pinnacles of birds and flowers, a piece of work by the carpenters of Bokhara struck 10.

Legha looked at her wristwatch, she set it forward and stood up, she walked away from the breakfast table and took the bread crumbs for the fish.

Vahhab, the son of the household, gulped down the last sip of tea after pouring some from that azure Serve teacup and stopped yawning, turned to Mrs. Edrisi:” she is better today.” The old lady moved the glasses on her nose, her eyes behind the glasses were dark blue:” It’s not clear what she does.”

The fog descended down to the arcade, fretted the windows, turned around, and faced pine and poplar trees. Down at the end, from the corridor, there came the sound of washing the dishes. The tap-water popped and turned around and then there was the bubbling of semavar.

From time to time, Yavar coughed in the kitchen, sluggishly pulled his feet on the floor.

The lady crossed her eyebrows:” Poor man, growing old, lost his lung by smoking...!” Vahhab leaned against the margins of the table, stood up.”I should go to the library, I read an article about the ruins of a city “Nisa”, it was a magnificent place once, buried now.”

Mrs. Edrisi sighed:” Plenty of them have been buried and one day our city is going to be buried.” Vahhab closed his eyes, turned back, and walked away.

The household were a kind of quiet in eating, drinking, walking and talking.

Vahhab was thirty but looked much older, thin and hunchback, a pale face, solemn and lightless eyes. He had studied at British boarding schools, for any word or movement, he felt the lashes of punishment on his back. He ate a little and took a shower before noon, clipped his nails every week, and filed them. Below his eyes was bloated from the shortage of sleep. He stood across from the mirror, counted the strands of grey hair in a pile of soft and black hair. The other day he had twelve of them, all white. He didn’t go out, always residing in a shelter, twice a month he dropped in “Ashena Bookshop”, the man put aside some new books for him, Vahhab knitted his eyebrows and with a tight mouth paid for them, straightly came back home.

In the afternoon if the weather was good, he would sit by the pool, opened the fountain, and looked at the patterns and the flow of water, he remembered the past, his childhood was far away.

Gradually when it was getting dark, the dreams faded away. Birds flew in the garden. In the hot weather females feeding cows at the end of the alfalfa field were mooing. On the second floor, his elder aunt, Legha sat behind the hatchway with her hand under a cheek, stared at the mulberry trees, clay-roofs, and faded attics till the time they would turn on the lamps around and drew the curtains. She didn't turn on the lamp but closed her eyes. Behind the dark dreamy drowned eye-lids, sometimes a blue and yellow pattern like flowers and silica glass expanded and amused her.

On the rocking chair, grannie leaned against the mahogany furniture of walnut trees, rubbed the perfume on the back-ears. The acrid extract of jasmine spread in the house. Once in a while, she would see the dreadful figure of her late husband, in a summer suit, with a white bow and salt and pepper whiskers, in a hoarse and throaty voice caused by tobacco and opium he whispered:” Such a nice smell!”

The time she stared into the dark, the white phantom had gone, then she heard the creaking hinges of the doors on the first storey, Yavar was walking in the corridor. He turned on the candelabra in the vault, it glared on the plaster moulding, the leaves of vine trees, lotus flowers, and clusters of grapes. The wind moved the candelabra and the chains squeaked. The rainbow prism glowed on the images of the carpet, the bifurcated winding stairs and bending balustrade all leaped around.

The first storey had three corridors, a big anteroom, a library and four bedrooms. On the second storey, around the balustrade there were ten attached bedrooms, all except three were locked.

In the morning, when Vahhab was tired of reading, leaning against the velvet cushion in the drawing-room , half asleep and behind the flower pots, he listened to the creaking of the springs, there were some pillows with the patterns of peacocks and parrots. He put them under his elbow, then he drank a cup of coffee and lit a cigarette.

Staring at the waterdrops, he yawned. There was a slight pain in his bones. shaking his legs he pondered into the past. He was dreaming of Rahila, his aunt who had died young of a strange fever. After her death, Mrs. Edrisi’s hair had grown white overnight, Vahhab was ten at that time.

She was engaged to a broad-shouldered stout man with big eyes and a Moorish face. A widower who was a grand landowner called Moayyed. People said that he lived in a mansion and had a lot of horses in the stable, in pomp and circumstance he came. They wanted to buy his chestnut horse for 3000 roubles, he came in hurry with three servants, the sound of his shoes on the pavement. Rahila would sit by the bed, didn’t move, her hands on the white satin weary and proud, pouted her lips like roses, grinned. Her head uplifted, her almond eyes half-open. The shade of her eyelashes on her moonlit cheeks and with a dreamy glance, tall, airy, introverted, and aloof, nothing made her happy. In the end of spring, she would sit in the courtyard. Sipping her tea on a straw chair under the trellis of lilacs, white pigeons surrounded her feet while hovering in the trellis. The rain started then she walked in the garden and her garments were wet. She looked at the clocks as if she were waiting for somebody, she didn’t have a friend. Never answered the letters, visits, or messages.

Vahhab used to look at her through the hatches. Rahila tucked up her skirt, skipping over the brook, soft and agile, pranced and tiptoed on the wet lawn, picked up a rose-bud, smelled and pinned it to her hair, she closed her eyes and opened them once more, wandered in the garden for hours, when she became tired, she went to the shade of that big elm tree then made a house with the rubble stones. She rooted up the grass and squeezed it with her teeth.In the end, while standing up, she ruined the built-up house with the rubble stones tossing over one another on the steep lawn.

The memory of Rahila was deeply moving, Rahila’s room at the end of the corridor, in the north frontline had two big windows, one to the garden and the other one to the courtyard and the arbour. The lace curtains had the smell of dust and the perfume of autumn crocuses, when he went to the mirror, his face looked like a stranger. He closed his eyes and wanted Rahila to be alive, her straight hair spreading around, loose on her shoulders, the strands slipped over one another like a flash of silk. Now Vahhab turned to a small boy, pulling her skirt naughtily, the young girl with her very charming eyes would send him off.

He opened the drawers, arranged the perfumes on the dressing table, nineteen hundred from Paris and Moscow, Italian, Chinese, Indian, the longlasting perfumes of far oceans: musk and birch and myrtle and black ambergris. In cosmetics she had nothing but perfume, there were several bottles in each drawer. He bent down the table, took a deep breath. He opened the closet, his face was lost in the white garments, muddy stains, flower buttons, dry grass and thorn, and beads. In the dark, it turned up a crack of mouth-worn wood, he tilted his head and closed the door. He put the perfume bottles in the right place, arranged the pleats of curtains, spread the bedspread to the pillows of lace and embroidery. He left the room, locked the door. In the dark corridor, walked on the polished parquet and went to the library.

They were some magazines in a drawer, he took them out and turned the pages over, he looked at the biography and pictures of Roxana Yashvili, she was a stage actress, starring in plays such as “Small Bourgeois”, “One Month in the Village”, “The Blue Bird” and “Chaika”, they called her a wildflower, the glimmering of a creative will-power in her eyes.

Critics believed she could show the spiritual images and transfer them to the audience, seemingly resembled Rahila, Vahhab looked at her pictures in the costumes of Normandy women, in a black velvet dress with a fan in one hand, beneath an arbour or at the breakfast table while playing with an actor. Painters had painted her on several canvases, poets had written many poems for her. Since six years before, she had been living with “Marenko”; the noted poet.

There was no picture of Rahila in the house. When Vahhab looked at Roxana’s almond and black and glimmering eyes and slim figure remembered Rahila. She came from Tbilisi with a different nature noted for her upheavals. Vahhab didn’t like her complacency, didn’t read the interviews, just looked at her pictures.

Just at twelve Legha climbed down the winding stairs, stepped in the hall, knitted her eyebrows, cross, broad-shouldered and tall, pale with big lips and a sharp chin and hooked nose, grey eyes, rummaging but lightless, fumbled around, wiggling, her backbones pricking in hatred, she was sensitive to heel-relief stone, even disliked the shape and the name. Naked and screaming she ran away and fainted on the floor. Mrs. Edrisi sneered and covered her hanging boobs with a sheet.

The smell of men revolted Legha, when the workers came for some days to dig the garden or trim the trees or cut the weeds, she locked herself in the room and didn’t come down. A strike of smell made her sick. She opened all the windows, the candelabra moved, in the arcade the wind blew and howled, for two times a day she took a shower. She had the smell of soap and foam with herself. At nights, right after the dinner she used to brew sour orange blossoms, she stirred it with a little teaspoon, the leaves soaked and spread out, the steam on the cup had a smell of moss and bare moors, she sipped the root beer slowly, with decency and dignity, her lips were not wet. She stood up and very cold said good night, in a flower-patterned gown and with plait hair, a hand on the banister, she climbed up the stairs and her pale countenance lost in the dark landing.

Chapter two

Mrs. Edrisi sighed in despair, card reading was over. She tossed the deck of cards on the dining table; it's getting worse day by day. Vahhab stopped reading, scratching his nose, nothing's moved.

The old lady smiled:" Poor the man who'd marry her!"

Vahhab's eyes glimmered mischievously. "Is there a man like that?"

"At least for money!"

"One should be perilous to marry such a freak!"

Mrs. Edrisi closed her eyes:" They do as if you don't know people!"

"Poor the man, what if she saw heel-relief stone...?!"

The old lady chuckled:" She would see far-off!"

"A whole sum of all contradictions!"

Fed up with cards, the old lady nodded. The clock struck eleven, in the far-off distance the owl was howling, placing her ears on the window, grannie listened:" Such a throat, howls excruciatingly loud, won't it cut its throat?"

Vahhab smiled wondering what the owl does.

Grannie left, resting the door ajar.

Vahhab kept solitary vigil at nights, reading and staying up by the daybreak.

About midnight a grey cat popped through the window.

Through the cat's eyes there was a wavy spectrum of seaweed colours, Vahhab pampered the cat, soothed its backbones, purring and mewing around, up and down into the cushions, turning a page over, the cat opened its eyes. Just before the sunrise, he used to move to the kitchen. The kitchen was in the corner of the dinning room. Warsaw Samavars with paintings on the wall, they looked crooked in the copper pans.

A cockroach was squeaking around on onion crusts. Branches of that weeping willow hit the windows, Vahhab would leave the kettle on to boil some water. Brewing tea and setting the silver tea set and then he left for the dinning room. Drinking cups and cups of tea one after another, Yavar was in the next door, the hedge of the doors creaked, twilight glowed on Yavar's salt and pepper beard, shabby and scruffy, untidy hair, bony skinny cheeks, dreamy and bewitched sleepy eyes seemed rather like sockets and holes carved into the darkness. His hunchback and loose and expressionless arms seemed like objects out of his body. He used to make a lot of noise and the cat cocked his ears, peeping around.

The cat leaped around the sofa and crept away. Yavar coughed huskily in the bright-lit corridor. The long shadow of fences over the yard. Vahhab switched off the candle on the wall, went up the stairs, his footsteps faded into the fluffy carpet. Grannie was snoring, turning the doorknob, he entered the room. Morning twilight with its mellow and pale light murkily was shading a silhouette of velvet. Arch over his head and morning sunlight was shading all over the place, dressed in pyjamas, drawing the bedspread, rested and rolled into that satin and soft bed, the crimson blanket over his head, to his chin, while reading he fell fast asleep.

Around ten in the morning, while Legha was playing the piano, he woke up. For another half an hour, he lay down in bed rolling from side to side.

Two times a day Legha played the piano, Italian Caprichoes, Franz Liszt's Rhapsodies, and Mandelson's Romances. For so many years she had played them with great skill in her fingers. No stranger could believe her skill, the spirit in her fingers, and many years of practice. The stagnant maidenhood and silent youth, all were her oppressed desires, yearning in music and all this deepened her strength. Closing the piano lid, she felt young once more, while turning back, she was Legha once again, fierce and impatient yelled at Yavar for mixing up her exceptional plate with others on the dish rack, she had secluded herself with her cutlery and dishes, golden felt-tip mug, the blue china dish, Sheffield bony forks. Before each meal, she watched her mug carefully in a bright-lit place not to observe a speck of dirt and stains on it. If there was a guest at home, Mrs. Edrisi would glare at her out of anger.

Yawning in bed, Vahhab got up and dressed impeccably in a white ironed shirt and tied, a trench coat with button cuffs. Brushing his hair, opened a central parting. In the pick of youth, he used to dress like an old man. Wearing a very strong perfume came to the breakfast table. Grannie coughed:" What an awful smell! you're reeking like Egyptian mummies, where the hell did you find it?"

Vahhab knitted his eyebrows:" It's the perfume of deep oceans, extracted essence of whale's abdomen, a gift of Buenos Aires."

Mrs. Edrisi nodded: "You call it a present?"

Aunt Legha frowned:" Much better than a man's smell!"

Grannie Chuckled:" Don't exaggerate it. A man has a job, a love affair, a riding horse, a hunting game, or at least a kinda drinking habit in a pub (sighed) I wish there were a man here."

Legha crumpled the napkin:" If you'd like a man here, I'll go and get a room in the town."

"Dear nowhere is free of men. One would crawl into your room one night!"

With a twist around the corner lines of her lips, Legha blushed. Hiding her face in her hands, ran towards the door. The sound of crying covered all over the house.

Yavar came in, smiling and peeping, asked the Grannie:" Anything you would like?"

Mrs. Edrisi smiled:" Come in!"

"Miss Legha's annoyed!"

Grannie said, her hands clasping: "Then if you could find her a suitor, it would be...."

Stealthily Yavar tiptoed to the door:" Ooooh! Heaven forbid, never ever! Haven't found a suitor and she hates me!"

Mrs. Edrisi pointed to the wooden stool:" Get sit down!"

He hesitated, blew the dust over the stool, and finally sat down on the clean stool.

Mrs. Edrisi said:" Oooooh! Leave it dear ...!You'll dust off the stuff later!"

"There won't be enough time, such a big manor house needs more servants."

Mrs. Edrisis's lips wrinkled in the corner: "Come on! We're single-handed, when the wages are low they come and see Legha and they flee! Nobody's as faithful as you. Remember the old days, those were the days. Once we cooked twenty rice bowls, what was the name of that chef? ( Scratching her forehead)...pity I don't remember the name!."

Yavar lifted his chin haughtily: "Ebrahim Beigh!"

" Ooooooh! Good!... I wish he had quit such horrible habits, he used to aim the knife at you as if stabbing!"

Yavar was bitting his lips:" Mr. Edrisi sacked him for his dirty look at women!"

Mrs. Edrisi placed her hair behind ears:" And you were the eye witness?!"

The air was penetrating into his cheeks, thoughtfully he spoke: "What shall I say ?! He was a Tatar with the habit of dancing with a knife!"

Quite irritated Mrs. Edrisi said: "Such nonsense! My Grannie was a half-breed Tatar, never seen such habits among them! Rahila was as decent as her."

Vahhab moved:" Where was she from?"

"Around Crimea, with a glamorous voice like nightingales, her voice got a move on the windows."

With a sparkle in his eyes, Vahhab asked:" What did she sing, Grannie?"

" It's a shame I cannot recall, Legha has taken after her in playing music."

Vahhab grinned:" The only talent she's got!"

Mrs. Edrisi said: "She might have some other abilities not flowered yet!"

Vahhab sneered: "It's apparently late now, you've counted on her a big deal!"

Mrs. Edrisi's face colored: " You two bear a resemblance!"

Quite irritated, looking at the table, Vahhab complained: "Grannie!!!... We have nothing in common."

The old lady sighed:" A mere bagatelle! At least Legha's touching her life in hatred, how about you?(scowling)

as dry as dust!"

Yavar stared into flower patterns of carpet, twisting a hair of his mustache:" Poor indigestion, it's the yellow bile, some jejebu and aloe vera would help."

Vahhab looked at the snowy landscape of the painting over the wall. At the end of poplar trees, dark and cold, the footprints of Rahila which were left seemed to fade.

Mrs. Esrisi's and Yavar's eyes met. The old lady shrugged her shoulders. Looked at the cards:" The knave of hearts, it's a good sign(lifted her eyebrows) a letter might come. Who is it from? Only God knows the soldiers of the new government might have written letters to Legha. What were they called?"

"Fire-squad-band they're called."

The wrinkles on Mrs. Edrisi's face disappeared at once:" Long ago they used to write letters to me.I never read them, tore up all ( stared at the foggy branches of maple ) a young soldier was in love with me, he wasn't from here, was in the regiment, had a childish face, dark blue eyes. One night I got up and I saw him if my father could get it he would turn him to a piece of..., I got dressed and bare-foot went to the garden, with tearful eyes he said that he was not from this county! Had come around to Kick the bucket. I said you must be insane! Lifting the lantern those satanic eyes looked like a hatchway to hell. He disappeared after some months. In the midwinter, I got the words that he had taken the journey to the mountains. He entered the anti-government campaign. How's the fire-squad band doing now?"

" Filthy people!"

The old man frowned and nodded:" They're not filthy, it's the smell of yarrow leaves they consume!"

"The yarrow leaves?"

"Their boots are green, their lips livid blue, they consume pure grass."

"When did they come?"

Vahhab twisted his mustache by his fingers:" Not worth speaking, never understood their attitude, inhumane, vulgar, barbaric, do they ever think? ( He touched the white flowers of the table cloth) vain, hollow mechanical man!"

Mrs. Edrisi asked:" Why don't you immigrate? Intellectuals like you have all left!"

The man yawned:" No Civilisation's left. People all over the world are dying from the neck up!" ( he grasped his hands ) never take me a pig-headed intellectual. Greedy and benumbed golden beard and necks, hand in hand with martial law have been buried somewhere in the hell! My books and room would suffice."

Vahhab's words seemed tedious to Yavar, he carried on with no care:" The time we were young, we climbed down the valley at moonlit nights. The fire squad band would stay on the mountain top and set a big fire."

Mrs. Edrisi asked: "Didn't you get scared?"

Yavar blinked:" Fear, what shall we call it? Their dazzling sparkling eyes like wolves."

Mrs. Edrisi wrapped the woolen scarf around her arms. " I don't know what happened to that soldier? Joined them and became a devil? He was in the first gang, must be dead now!"

Yavar pondered:" Tongue-tied, a herb they've taken, mouth-shut!"

Mrs. Edrisi said:" I've heard they never pay for the things they purchase."

Yavar nodded.

Vahhab closed the book:" This is the privilege we have. Money matters, they never care for the dainty stuff, they return them."

Mrs. Edrisi asked:" How can they pull the wool over our eyes?"

Yavar hesitated:" They'd come for an inquiry, they'd asked how many we are and what we do, the neighbors have told them about the charity hospital."

Mrs. Edrisi bent down:" Why didn't you tell us sooner?"

Vahhab clicked his jaws:" So one of these days they swarm over us like bugs, they'll ruin culture and beauty. Decadence has taken its place( He stood up and the chair was knocked by the table, walked along the room)

The world is going to decline. We live at the age of Kali Yuga! Pity a city like Nisa's buried ( looked at Mrs. Edrisi) I wish I hadn't been born at the present time. Several centuries ago would fit me better; the age of Achilles, Prickles, the knights of the round table, queens and the empress, the story of Shehrzadeh and one thousand and one Arabian nights or saint Aquinas."

( His eyes radiant with the magnificence of old age.)

The old lady turned up her nose:" You would have been a misanthropist at any age! ( looked at the plaster molding of the ceiling in regret) Before long it'll be our turn. Since last week I've been plagued with the nightmare of the fire-squad. As if their teeth were growing out of grass, fuzzy hair mixed with the smell of fleecing wool, marching their boots. I got up and went to the window, gazed at the lamp-post in the street, shifting one by one, do they ever sleep?"

Yavar lifted his chin:" Two hours a day with nightmares, got used to it."

" And manners?"

" They laugh all in a group, hairy, bushy, beardy and filthy, people call them beefy!"

The old lady got a glimpse: " a mine of rumors ( asking Vahhab ), don't you look at the papers?"

The man crumbled a piece of paper:" Vulgar, all the same. Scruffy faces holding guns, with a flag in their hands marching, could you get it, grannie? Long lists of executions, let's dispense with it!"

Mrs. Edrisi stared at the lamp bulb:" No peace anymore!"

Chapter three

Mrs. Edrisi was sitting next to the velvet cushion, looking into the garden. She was doing a piece of embroidery on that green table cloth. She was doing some maroon six-petal daisies, the feathers of peacock and some iris flowers, her fingers were really skilled, her hands full of grace.

Legha was dressing up in a long and green robe, wearing white wooden sandals, her fingers were wrinkled of the spa bath. Her wet hair was braided, ribboned in pink. She used to do some exercise after breakfast.

For thirty times she stretched and joined her legs, lowering her head between the stretched legs and arms stretched moving along the room. She called it butterfly movement. Turning around her waist, she did some muscle breathing exercise, with each movement hands up, with no direction in the air moved along a curve. She took a deep breath, her belly inflated with the navel out, like newborn babies.

Yavar was sweeping the pavement of the yard. His cigarette unlit in the corner of his lips. He opened the fountains, listened to the music of the fountains. In the front, the pigeons with bloated throats left their feathers on the paving stones. Somebody was knocking at the door, knock, knock and knock. It repeated several times.

He left the broom, quite pale, walked to the corridor, opened the door in the corridor, kneeled with his hands posed for praying:" May God help us!"

The old man lowered his head. Legha shouted and took hold of her skirt, big thighs and red knees appeared. One sandal out:" I'll kill myself", half crawling burst into tears, her tears were dropping over her nose, twinkled, her pupils looked much bigger, the knocking at the door repeated. Vahhab was still in his sleeping gown, climbed down the stairs. With shabby hair, a sticky ringlet of hair over his forehead marked his restless nights and sleepiness. The lock of hair was stiffened over the parting, he tied his robe:

" Our game's over! Try not to show fear ( He went to the study and touched the leather binding of the books), they would take whatever we have."

The old lady responded:" I'll go and open the door."

Startled back, Vahhab looked into the mirror then straightened his hair:" Do I look good?"

Yavar buttoned up: "Your look doesn't matter, as if they were raiding into the yard."

Mrs. Edrisi lifted her head:" Then I'll go."

She opened the door in the corridor; a cold breeze was penetrating.

She climbed down the stairs outside in the courtyard. The moisture on the lilacs was evaporating gradually. The water drops were dropping down the fir tree. She opened the gate, took hold of the doorknob, it was cold and wet.

The one who was shorter leaned against the door. In a pale green uniform, dusty and creased, his fingers on the trigger, his hair scruffy rough like a cloth brush, the brushy waxy beard had covered his lips, all over his chin and cheeks.

He was watching the edifice in triumph. Mrs. Edrisi turned and looked at the same point. The attic had become tattered, the hatched roof and the gable hazy in the fog, chimnies, draughty corridors, ventilators, brown hatches, and lace curtains, as if they had been forgotten over the years.

The firing squad members sneered; the one who was in the front, with a thin lanky neck which much looked like the stem of a cherry, and the second who was shorter and muscular.

The skinny boy looked at his worn-out boots:" How many people are living here?"

While smoothing her throat, Mrs. Edrisi replied:" Four, does it matter?"

The second firing-squad member kicked to the fences:" We're supposed to ask and you're obliged to answer, understood?"

The shawl slipped over her shoulders and arms:

"No problem, there's nothing to say!"

The slim boy looked at her:" How many rooms do you have?"

Mrs. Edrisi answered hesitatingly: "I guess twenty ."

They both laughed along, the man with broad shoulders asked:" How long have you been here?"

Mrs. Edrisi lifted one hand:" For four generations."

"Then you don't know how many rooms you have?!"

Mrs. Edrisi smiled:" Rooms are for living not for counting."

The short man said:" Not an excuse ( he stepped in) we'll go for further observation."

They went into the manor house, the march of boots on the stairs was echoing. One by one they came in, Legha was peeping, she jumped and ran away to the back room. Vahhab got dressed, buttoned-up disorderly, as if one shoulder looked broader, holding hands, leaned on the wall. Yavar's lips moved in silence. Startled while facing them.

They entered the anteroom. They examined the walls and the ceiling. The skinny boy whistled: "All accessories!"

The broad-shouldered turned around, pulling a thread of mustache:" Just four, (clapped hands and laughed), how many were we in each tent?"

" The number of these rooms."

The shortie nodded:" The number was adding up day by day, isn't it stupid to miss such horrible days?"

The other one sighed: "Just right at the dawn the skyline was clear, the wild birds used to sit over our shoulders, we shivered in cold."

The broad-shouldered pointed to the painting:" Is it a replica?"

Mrs. Edrisi paused:" It should be the original."

The man got closer and touched the paint:" I had seen the replicas, never thought one day I could see the original. The waves look vivid, the seagulls flow away in a flock, just like us ( suddenly became firm) the possession of such items should be clarified. Belongs to the museum."

Mrs. Edrisi objected: " people's possessions are not your business."

They both burst into laughter; the thinner blushed:" It's a part of our duty."

They went to the window, shoulder by shoulder, they stood. In the cloudy sunlight, they looked vulgar and despicable. The broad-shouldered poked:" Such a garden has no borders!"

The scrawny pointed to a tree: "Silver leaves!"

The broad-shouldered nodded:" I hadn't seen such a tree before."

"Grows in cold places."

Mrs. Edrisi followed them:" Would you like to chop it off for your museum? Forty-two at least, as old as my elder daughter."

Somebody who was hiding back at the partition said:" The silver fir tree is not over thirty."

The firing-squad band turned back, the broad-shouldered pleaded: "Whose voice was that?"

There were the hustles and bustles, a short breath, a short sigh, the broad-shouldered peeped in. Legha leaned on the closet, pushed the doorknob." Don't get closer!"

The young one looked at the other in surprise, his finger on the trigger: "Why? Is she armed?"

Legha burst into tears, down in the partition, you could see her ankles. Her wooden sandal heels were being pressed on the floor, the scrawny looked at the old lady and said:" Has she got a contagious disease?"

Mrs. Edrisi nodded: "She hates men."

The young men laughed aloud. The candelabra moved. The sighs were short, something was falling down.

The broad-shouldered kicked over:

"And she detests us?"

The door opened and the smell of ambergris mixed with tiny waves was blowing over:" Legally you cannot hurt us, we are not guilty."

The slim-necked winked:" Good morning, living in such a house is the biggest crime."

Vahhab's nose vibrated, he put his hand over his mouth, something inside him was twitching:

"It's our heritage, should we have destroyed it?"

"No, you should have dedicated it to us."

" For the sake of Republic? If it was easy you'd never resided in the mountains."

"Anyone willing can join the firing band."

" On what cost?"

" The cost of your life."

"Very kind of you! We don't deserve it! So what? what could get your place?!"

The slim figure headed forward:

" You would have been honoured if you could be in our place."

"We don't need an honourary degree."

The broad-shouldered knocked the gun stock over his shoulder.

As if your body's itching for real punishment, go ahead but we'll make you behave at the end."

Legha screamed and fainted. The old lady opened the closet, unfolded jasmine-scented sheets. The aroma spread in the house, she covered her with a white sheet, the maiden sighed and fell asleep.

The fire-band turned around, inspected the first storey. They went to open Rahila's room, Vahhab pushed them away, held the doorknob.

"The room's bleak hasn't been open since twenty years ago."

The broad-shouldered twisted the new-grown mustache:" We'll inaugurate it."

Vahhab shielded his breast:" Over my dead body."

His eyes flamed in the dark.

The fire-band member panicked and went back, furious and tempted turned back:

"What's the secret in the locked door?"

Mrs. Edrisi explained:" It's not a secret, all perfume and dress, turned to a legend now. The room belonged to my daughter who died young( she wrapped the hems of the shawl around her fingers.)

The mysterious story of her death was never disclosed to us ( sighed bitterly) she died of ill fate and the stuff there are Rahila's memorabilia, we kept everything untouched, even the strands of her hair over the comb.

One poked the other one and whispered some words and took a stroll out of his pocket, lit a match, the light was faltering, he pointed to some lines in the stroll, marched on the floor and yelled:" For now there's nothing to do with this room."

They came back to the hallway, the broad-shouldered stared into the ceiling :

" Obscure and dim."

Over the arched windows, the pigeons were flying. Over the twigs and foliage was covered with dung and droppings, hovered over the winding stairs on the landing of the second story, they opened the white doors with the white golden-bread room, the stuffy air spread around. The satin bedspread's lustrous radiant in the sunlight, its heavenly image reflected in the dusty mirrors. In Legha's room, there was a wet towel hanging on the chair. The flared flappy pyjamas on the side of the bed, the breeze which was blowing made it look much bigger in size.

On the bedside table, the book of memoirs was turning page by page. The virgins of the rocks were the only ornament on the walls.

In Vahhab's room, the canopy curtains had been drawing back. The smell of ambergris had covered the house. Rablais' "Great Garagantu" was open on the floor. In the light of the lamp bulb, a bottle of water and sleeping pills were seen on the bedside table. The broad-shouldered entered. Backed the bedspread. The dust over the fluffy velvet spread in the room.

"What's the use of it?"

Vahhab leaned against the door:" It barricades the sound and night. Gives security to me. "

The fire-band frowned: "Not a necessity ( he looked at his comrade ) stupid! Let's take it to the store!"

Vahhab complained:" I cannot sleep without them, ( marking the table) see the pills! I suffer from insomnia."

While drawing the curtains, they parted it! They folded the heavy velvet, bundled it and took it, punched to the shelf, the plaster moulder was dropping down, they made a fuss and left the room.

Vahhab hid his head in his knees, under the checkered coat, his shoulders were trembling.

The slim figure turned back, put the pills into his pocket, slammed the door, and left.

Yavar got closer to Vahhab, kneeled in front of him:" Don't worry sir, we'll make another!"

The broad-shouldered opened the door:" No curtains! You'll sleep this way or you'll die of insomnia."

They went to the old lady's, the rocking chair was creaking and moved. There was a raw of small bottles on the dressing table, jasmine, and pansy in a bottle of perfume, powder pad, and a golden comb.

The broad-shouldered took a plastic bag out, put them all in. The rocking chair was moving, kicked to the legs of the table, looked at the comrade: "You like such stuff?"

The slim man nodded:" Such trinkets make me sick." ( glared at the chair) I dislike them."

Mrs. Edrisi objected:" You don't have to like it, it's my personal stuff, I sit there in the afternoons."

The fire band shrugged:" You're not a child!"

The broad-shouldered confirmed:" It's okay."

He put the chair on the balcony, it was getting dark and cloudy, the fog was descending, it was raining, he lifted the chair but dropped it. The chair fell down and broke. He burst into laughter, a burst of hysteric laughter perhaps, poked into his comrade. As a sign of victory, tapped on his knees. Showed some lines of the dirty stroll to the lady, Mrs. Edrisi pushed back to the stroll:" These stupid lines don't make for the chair."

The rain and fog showed her face a little bit paler. She looked at the broken chair:" I used to sit there and reminisce old days, my whole family used it before me, all fingerprints of my mother, my husband, and my young daughter who died young."

She placed her head into the frame, the fire-band had gone, they slammed the door, pranced over the stairs. Mrs. Edrisi came into the room. She lay down, covered her body in the blanket, hands over her eyes.

The House of Edrisis is a prominent post-revolutionary novel in Iran by Ghazaleh Alizadeh, a noted novelist, translated from original Persian to English by Rosa Jamali.

Contact:

rosa_jamali@yahoo.com

rosajamali@gmail.com

Quotations are free as far as you mention the translator's name.

Excerpts can be cited with a reference.

THE HOUSE OF THE EDRISIS

Published on April 14, 2013 12:46

•

Tags:

ghazaleh-alizadeh, iranian-women-writers, novel