J. Bradford DeLong's Blog, page 322

August 12, 2018

The Vexed Question of Prussia in World History...

Reading Adam Tooze's powerpoints for his _War in Germany, 1618-1648 course, and thinking about the Vexed Question of Prussia in World History...

For a bit over the first half of the Long 20th Century global history was profoundly shaped by the peculiarity of Prussia. The standard account of this peculiarity���this sonderweg, sundered way, separate Prussian path���has traditionally seen it has having four aspects. Prussia���and the "small German" national state of which it was the nucleus���managed to simultaneously, over 1865-1945:

wage individual military campaigns with extraordinary success: in campaigns it should have won it conquered quickly and overwhemingly; in campaigns it should have narrowly lost it won decisively; in campaigns it should have lost it turned them into long destructive abattoirs.

wage wars no sane statesman would have entered and���unless its first quick victories were immediately sealed by a political agreement���lose them catastrophically via total neglect of grand-strategical and strategical considerations, and a failure to take anything other than the shortest view of logistics.

via the role, authority and interests of the military-service nobility societal caste, divert the currents of political development from the expected Anglo-Saxon, Celtic, French, Belgian, Dutch, Swiss, Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish path of growing political and social democracy into a separate channel, a sonderweg, of authoritarian rule at home in the short-run material interest of a business-landlord-service nobility class and caste, and of desired conquest and demographic expansion in the European "near abroad".

engage in continent-spanning systematic patterns and campaigns of terror, destruction, murder, and genocide that went far beyond anything other European powers engaged in within Europe, and even went far beyond the brutalities of colonial conquest and rule that European powers engaged in outside the continent.

Did Prussia���and the "small German" national state of which it became the core���in fact follow a separate and unusual path with respect to economic, political, cultural, social development relative to other western European national states in the arc from France to Sweden? Do these four aspects as components rightlfy summarize the sonderweg? What is their origin, and what is the relation between them?

This is the vexed question of Prussia...

The first thing to note is that Prussian operational excellence���winning campaigns it ought to of lost, and winning decisively and overwhelmingly campaigns it ought to have narowly won���did not exist before 1866 and the Prussian victory at Konnigratz in the Austro Prussian war. In 1864 the Prussian army did not cover itself with glory in the short Austro-Prussian war against Denmark. In 1815 the Prussian army had the distinction of losing the last two battles anybody ever lost to Napoleon: the battles of Ligny and Wavre. Also in 1815 staff confusion in arranging the order of mar h and the consequent delayed arrival of Prussian forces at Waterloo turned the Duke of Wellington's victory from a walk in the park into a damned near run thing and a bloody mess. In the rest of the Napoleonic and French Revolutionary wars, the performance of the Prussian army was: competent but undistinguished in 1813-4, the most disastrous in history in 1806, less than competent from 1792-5.

You have to go back to 1762 and the wars of Friedrich II Hohenzollern (the Great) to see any evidence of operational excellence, or, indeed, more than bare competence. Looking backward we can see Friedrich II as the culmination of a line of military-political development through Friedrich Willem and Friedrich I back to Friedrich Willem ("the Great Elector"). But there appears to be a century-long near-hiatus in anything that could be called a distinctive Prussian military-political-sociological pattern outside of the military, the bureaucracy, and their service nobility...

August 11, 2018

Globalization: Some Fairly-Recent Should- and Must-Reads

Marti Sandbu: EuroTragedy: A Drama in Nine Acts, by Ashoka Mody: "Writing about the euro... doing justice to the technicalities threatens to kill any narrative, while simplified storytelling risks misguided analysis. Ashoka Mody���s... is an ambitious attempt to avoid this trap...

We really do not know what effect a trade war would have on the global economy. All of our baselines are based off of what has happened in the past, long before the age of highly integrated global value chains. It could be small. It could be big. The real forecast is: we just do not yet know: Dan McCrum: Trade tension and China : "The war on trade started by the Trump administration is percolating through the world's analytical apparatus.... Tariffs could be bad for the global pace of economic activity, but only if the economic warfare escalates...

It has always seemed to me that the sharp Josh Bivens is engaging in some motivated reasoning here: "[1] Putting pen-to-paper on trade agreements contributed nothing to aggregate job loss in American manufacturing. This is almost certainly true.... [2] The trade agreements we have signed are mostly good policy and have had only very modest regressive downsides for American workers. This is false." How am I supposed to reconcile [1] and [2] here?: Josh Bivens (2017): Brad DeLong is far too lenient on trade policy���s role in generating economic distress for American workers on Brad DeLong (2017): NAFTA and other trade deals have not gutted American manufacturing���period: "I could rant with the best of them about our failure to be a capital-exporting nation financing the industrialization of the world...

My More Polite Thoughts from Aspen...

Early industrial Japan did marvelous things. It accomplished something unique: transferring enough industrial technology outside of the charmed circles of the North Atlantic and the temperate-climate European settler economies. Ever since, politicians, economists, and pretty much everybody else have been trying to determine just what it was Japan was ale to do, and why. But it was a low-wage semi-industrial civilization, economizing on land, materials, and capital and sweating labor: Pietra Rivoli (2005): The Travels of a T-Shirt in the Global Economy: An Economist Examines the Markets, Power, and Politics of World Trade (New York: John Riley: 0470456426) https://books.google.com/books?isbn=0470456426: "Female cotton workers in prewar Japan were referred to as 'birds in a cage'...

Edith Laget, Alberto Osnago, Nadia Rocha, and Michele Ruta: Trade agreements and global production: "Deeper agreements have boosted countries��� participation in global value chains and helped them integrate in industries with higher levels of value added. Investment and competition now drive global value chain participation in North-South relationships, while removing traditional barriers remains important for South-South relationships...

Wealth inequality measures have been grossly understating concentration because of tax evasion and tax avoidance in tax havens: Annette Alstads��ter, Niels Johannesen, and GabrielZucman: Who owns the wealth in tax havens? Macro evidence and implications for global inequality: "This paper estimates the amount of household wealth owned by each country in offshore tax havens...

Jared Bernstein: [Trump did a bunch of stuff to strengthen the dollar; now he���s upset about the strengthening dollar(https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/p...term=.576fbc1e4803)_: "Trump is annoyed that the Fed is raising rates and that the stronger dollar is making our exports less competitive...

Paul Krugman: Brexit Meets Gravity: "These days I���m writing a lot about trade policy. I know there are more crucial topics, like Alan Dershowitz. Maybe a few other things? But getting and spending go on; and to be honest, in a way I���m doing trade issues as a form of therapy and/or escapism, focusing on stuff I know as a break from the grim political news...

A Britain led by Theresa May or Boris Johnson or Jeremy Corbin will not "rediscover its own way... the British rae most resilient, most inventive, and happiest when they feel in control of their own future". That is simply wrong. And if it were right, May and Johnson and Corbin are not Churchill or Lloyd-George or even Salisbury: Robert Skidelsky: The British History of Brexit: "I am unpersuaded by the Remain argument that leaving the EU would be economically catastrophic for Britain...

Paul Krugman: "Maybe it's worth laying out the incoherence of Trump's trade war a bit more, um, coherently...

IMHO, betting that "even the Tory Party can spot a wrong 'un" seems a lot like drawing to an inside straight: Dan Davies: "The hard brexit types have been bounced into deal which has taught them that they're not as clever as they thought they were. Now they'll react to that with a leadership challenge which will teach them that they're not as popular as they thought they were. It's like education in the Montessori system-each little independence of discovery builds on the next..."

Anne Applebaum: Brexit is reaching its grim moment of truth���and the Brexiteers know it: "David Davis... and Boris Johnson.... At no point... have they or any of their Brexiteer colleagues offered what might be described as a viable alternative plan. That is because there isn���t one...

Trade around the Indian Ocean before 1500 was a largely peaceful, stable process. Empires, kingdoms, sultanates, and emirates ruled the lands around the ocean, but they did not have the naval strength or the orientation to even think of trying to control the ocean's trade. Pirates were pirates���but only attacked weak targets, and needed bases, and for the land-based kingdoms providing bases for pirates disrupted their own trade. Then came 1500, and a new entity appeared in the Indian Ocean: the Portuguese seaborne empire: [Non-Market Actors in a Market Economy: A Historical Parable): From David Abernethy (2000), The Dynamics of Global Dominance: European Overseas Empires 1415-1980 (New Haven: Yale), p. 242 ff: "Malacca... located on the Malayan side of the narrow strait... the principal center for maritime trade among Indian Ocean emporia, the Spice Islands, and China...

Alex Barker and Peter Campbell: Honda faces the real cost of Brexit in a former Spitfire plant: "Honda operates two cavernous warehouses.... They still only store enough kit to keep production of the Honda Civic rolling for 36 hours...

The big problem China will face in a decade is this: an aging near-absolute monarch who does not dare dismount is itself a huge source of instability. The problem is worse than the standard historical pattern that imperial succession has never delivered more than five good emperors in a row. The problem is the again of a formerly good emperor. Before modern medicine one could hope that the time of chaos between when the grip on the reins of the old emperor loosened and the grip of the new emperor tightened would be short. But in the age of modern medicine that is certainly not the way to bet. Thus monarchy looks no more attractive than demagoguery today. We can help to build or restore or remember our ���republican remedy for the diseases most incident to republican government���. An autocracy faced with the succession and the dotage problems does not have this option. Once they abandon collective aristocratic leadership in order to manage the succession problem, I see little possibility of a solution. And this brings me to Martin Wolf. China's current trajectory is not designed to generate durable political stability: Martin Wolf: How the west should judge the claimsof a rising China: ���Chinese political stability is fragile...

Brad Setser: "Larry Summers on Trump and trade:: 'From tweet to tweet, official to official, nobody can tell what his priorities are.' Certainly rings true to me. I have almost stopped trying to guess. Even for China:"

Very much worth reading from Nick Bunker: Nick Bunker: Pu...

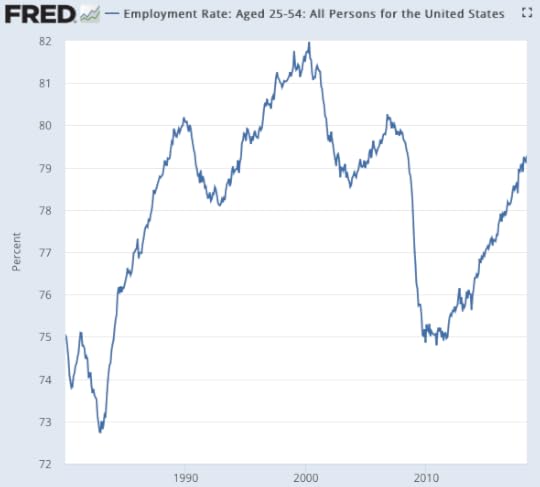

Very much worth reading from Nick Bunker: Nick Bunker: Puzzling over U.S. wage growth: "Hiring has not been particularly strong during this recovery...

...Even accounting for the low unemployment-to-vacancy ratio hiring is down. But only certain kinds of hiring are down. Hiring of workers who were previously unemployed or out of the labor market is in-line with the previous labor market recovery. The hiring that is down is the hiring of already-employed workers.... Analysis of the data shows a weak relationship between the unemployment rate and a good measure of wage growth. The prime employment rate has a much stronger relationship and has done a good job predicting wage growth out of the sample it draws from. The relationship is holding up in practice. Economists and analysts may just need to figure out how it works in theory...

See: here is another study that finds a lot of hysteresis...

See: here is another study that finds a lot of hysteresis���an ungodly amount: Christina D. Romer and David H. Romer: Why Some Times Are Different: Macroeconomic Policy and the Aftermath of Financial Crises: "Analysis based on a new measure of financial distress for 24 advanced economies in the postwar period shows substantial variation in the aftermath of financial crises...

...This paper examines the role that macroeconomic policy plays in explaining this variation. We find that the degree of monetary and fiscal policy space prior to financial distress���that is, whether the policy interest rate is above the zero lower bound and whether the debt-to-GDP ratio is relatively low���greatly affects the aftermath of crises. The decline in output following a crisis is less than 1 percent when a country possesses both types of policy space, but almost 10 percent when it has neither. The difference is highly statistically significant and robust to the measures of policy space and the sample. We also consider the mechanisms by which policy space matters. We find that monetary and fiscal policy are used more aggressively when policy space is ample. Financial distress itself is also less persistent when there is policy space. The findings may have implications for policy during both normal times and periods of acute financial distress...

#shouldread

August 10, 2018

Thomas Babington Macaulay (1831): Speech on the Great Reform Bill (March 2): "Reform, That You May Preserve": Weekend Reading

Thomas Babington Macaulay: Ministerial Plan of Parliamentary Reform: "It is a circumstance, Sir, of happy augury for the measure before the House, that almost all those who have opposed it have declared themselves altogether hostile to the principle of Reform...

...Two Members, I think, have professed, that though they disapprove of the plan now submitted to us, they yet conceive some alteration of the Representative system to be advisable. Yet even those Gentlemen have used, as far as I have observed, no arguments which would not apply as strongly to the most moderate change, as to that which has been proposed by his Majesty's Government.

I say, Sir, that I consider this as a circumstance of happy augury. For what I feared was, not the opposition of those who shrink from all Reform,���but the disunion of reformers. I knew, that during three months every reformer had been employed in conjecturing what the plan of the Government would be. I knew, that every reformer had imagined in his own mind a scheme differing doubtless in some points from that which my noble friend, the Paymaster of the Forces, has developed. I felt therefore great apprehension that one person would be dissatisfied with one part of the Bill, that another person would be dissatisfied with another part, and that thus our whole strength would be wasted in internal dissensions.

That apprehension is now at an end. I have seen with delight the perfect concord which prevails among all who deserve the name of reformers in this House, and I trust that I may consider it as an omen of the concord which will prevail among reformers throughout the country.

I will not, Sir, at present express any opinion as to the details of the Bill; but having during the last twenty-four hours, given the most diligent consideration to its general principles, I have no hesitation in pronouncing it a wise, noble, and comprehensive measure, skilfully framed for the healing of great distempers, for the securing at once of the public liberties and of the public repose, and for the reconciling and knitting together of all the orders of the State.

The hon. Baronet (Sir John Walsh) who has just sat down has told us, that the Ministers have attempted to unite two inconsistent principles in one abortive measure. He thinks, if I understand him rightly, that they ought either to leave the representative system such as it is, or to make it symmetrical. I think, Sir, that they would have acted unwisely if they had taken either of these courses. Their principle is plain, rational, and consistent. It is this, ���to admit the middle class to a large and direct share in the Representation, without any violent shock to the institutions of Our country [hear!]. I understand those cheers���but surely the Gentlemen who utter them will allow, that the change made in our institutions by this measure is far less violent than that which, according to the hon. Baronet, ought to be made if we make any Reform at all.

I praise the Ministers for not attempting, under existing circumstances, to make the Representation uniform���I praise them for not effacing the old distinction between the towns and the counties,���for not assigning Members to districts, according to the American practice, by the Rule of Three. They have done all that was necessary for the removing of a great practical evil, and no more than was necessary. I consider this, Sir, as a practical question. I rest my opinion on no general theory of government���I distrust all general theories of government. I will not positively say, that there is any form of polity which may not, under some conceivable circumstances, be the best possible. I believe that there are societies in which every man may safely be admitted to vote [hear!]. Gentlemen may cheer, but such is my opinion.

I say, Sir, that there are countries in which the condition of the labouring classes is such that they may safely be intrusted with the right of electing Members of the Legislature. If the labourers of England were in that state in which I, from my soul, wish to see them,���if employment were always plentiful, wages always high, food always cheap,���if a large family were considered not as an encumbrance, but as a blessing��� the principal objections to Universal Suffrage would, I think, be removed. Universal Suffrage exists in the United States without producing any very frightful consequences; and I do not believe, that the people of those States, or of any part of the world, are in any good quality naturally superior to our own countrymen.

But, unhappily, the lower orders in England, and in all old countries, are occasionally in a state of great distress. Some of the causes of this distress are, I fear, beyond the control of the Government. We know what effect distress produces, even on people more intelligent than the great body of the labouring classes can possibly be. We know that it makes even wise men irritable, unreasonable, and credulous���eager for immediate relief���heedless of remote consequences. There is no quackery in medicine, religion, or politics, which may not impose even on a powerful mind, when that mind has been disordered by pain or fear.

It is therefore no reflection on the lower orders of Englishmen, who are not, and who cannot in the nature of things be highly educated, to say that distress produces on them its natural effects, those effects which it would produce on the Americans, or on any other people,���that it blunts their judgment, that it inflames their passions, that it makes them prone to believe those who flatter them, and to distrust those who would serve them. For the sake, therefore, of the whole society, for the sake of the labouring classes themselves, I hold it to be clearly expedient, that in a country like this, the right of suffrage should depend on a pecuniary qualification.

Every argument, Sir, which would induce me to oppose Universal Suffrage, induces me to support the measure which is now before us. I oppose Universal Suffrage, because I think that it would produce a destructive revolution. I support this measure, because I am sure that it is our best security against a revolution. The noble Paymaster of the Forces hinted, delicately indeed and remotely, at this subject. He spoke of the danger of disappointing the expectations of the nation; and for this he was charged with threatening the House. Sir, in the year 1817, the late Lord Londonderry proposed a suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act. On that occasion he told the House, that, unless the measures which he recommended were adopted, the public peace could not be preserved. Was he accused of threatening the House?

Again, in the year 1819, he brought in the bills known by the name of the Six Acts. He then told the House, that, unless the executive power were reinforced, all the institutions of the country would be overturned by popular violence. Was he then accused of threatening the House?

Will any Gentleman say, that it is parliamentary and decorous to urge the danger arising from popular discontent as an argument for severity; but that it is unparliamentary and indecorous to urge that same danger as an argument for conciliatory measures?

I, Sir, do entertain great apprehension for the fate of my country. I do in my conscience believe, that unless this measure, or some similar measure, be speedily adopted, great and terrible calamities will befal us. Entertaining this opinion, I think myself bound to state it, not as a threat, but as a reason. I support this measure as a measure of Reform: but I support it still more as a measure of conservation. That we may exclude those whom it is necessary to exclude, we must admit those whom it may be safe to admit. At present we oppose the schemes of revolutionists with only one half, with only one quarter of our proper force. We say, and we say justly, that it is not by mere numbers, but by property and intelligence, that the nation ought to be governed. Yet, saying this, we exclude from all share in the government vast masses of property and intelligence,���vast numbers of those who are most interested in preserving tranquillity, and who know best how to preserve it.

We do more.

We drive over to the side of revolution those whom we shut out from power.

Is this a time when the cause of law and order can spare one of its natural allies? My noble friend, the Paymaster of the Forces, happily described the effect which some parts of our representative system would produce on the mind of a foreigner, who had heard much of our freedom and greatness. If, Sir, I wished to make such a foreigner clearly understand what I consider as the great defects of our system, I would conduct him through that great city which lies to the north of Great Russell-street and Oxford-street,���a city superior in size and in population to the capitals of many mighty kingdoms; and probably superior in opulence, intelligence, and general respectability, to any city in the world. I would conduct him through that interminable succession of streets and squares, all consisting of well-built and well-furnished houses. I would make him observe the brilliancy of the shops, and the crowd of well-appointed equipages. I would lead him round that magnificent circle of palaces which surrounds the Regent's-park. I would tell him, that the rental of this district was far greater than that of the whole kingdom of Scotland, at the time of the Union. And then I would tell him, that this was an unrepresented district!

It is needless to give any more instances. It is needless to speak of Manchester, Birmingham, Leeds, Sheffield, with no representation; or of Edinburgh and Glasgow with a mock representation. If a property-tax were now imposed on the old principle, that no person who had less than 150l. a year should contribute, I should not be surprised to find, that one-half in number and value of the contributors had no votes at all; and it would, beyond all doubt, be found, that one-fiftieth part in number and value of the contributors had a larger share of the representation than the other forty-nine-fiftieths.

This is not government by property. It is government by certain detached portions and fragments of property, selected from the rest, and preferred to the rest, on no rational principle whatever. To say that such a system is ancient is no defence. My hon. friend, the member for the University of Oxford (Sir R. Inglis) challenges us to show, that the Constitution was ever better than it is Sir, we are legislators, not antiquaries. The question for us is, not whether the Constitution was better formerly, but whether we can make it better now.

In fact, however, the system was not in ancient times by any means so absurd as it is in our age. One noble Lord (Lord Stormont) has to-night told us, that the town of Aldborough, which he represents, was not larger in the time of Edward 1st than it is at present. The line of its walls, he assures us, may still be traced. It is now built up to that line. He argues, therefore, that, as the founders of our representative institutions gave Members to Aldborough when it was as small as it now is, those who would disfranchise it on account of its smallness have no right to say, that they are recurring to the original principle of our representative institutions.

But does the noble Lord remember the change which has taken place in the country during the last five centuries? Docs he remember how much England has grown in population, while Aldborough has been standing still? Does he consider, that in the time of Edward 1st this part of the island did not contain two millions of inhabitants? It now contains nearly fourteen millions. A hamlet of the present day would have been a place of some importance in the time of our early Parliaments. Aldborough may be absolutely as considerable a place as ever. But compared with the kingdom, it is much less considerable, by the noble Lord's own showing, than when it first elected burgesses.

My hon. friend, the member for the University of Oxford, has collected numerous instances of the tyranny which the kings and nobles anciently exercised, both over this Mouse, and over the electors. It is not strange, that, in times when nothing was held sacred, the rights of the people, and of the Representatives of the people, should not have been held sacred. The proceedings which my hon. friend has mentioned, no more prove, that, by the ancient constitution of the realm, this House ought to be a tool of the king and of the aristocracy, than the Benevolences and the Ship-money prove their own legality; or than these unjustifiable arrests, which took place long after the ratification of the great Charter, and even after the Petition of Right, prove that the subject was not anciently entitled to his personal liberty.

We talk of the wisdom of our ancestors ���and in one respect at least they were wiser than we. They legislated for their own times. They looked at the England which was before them. They did not think it necessary to give twice as many Members to York as they gave to London, because York had been the capital of Britain in the time of Constantius Chlorus; and they would have been amazed indeed if they had foreseen, that a city of more than a hundred thousand inhabitants would be left without Representatives in the nineteenth century, merely because it stood on ground which, in the thirteenth century, had been occupied by a few huts.

They framed a representative system, which was 1196 not indeed without defects and irregularities, but which was well adapted to the state of England in their time. But a great revolution took place. The character of the old corporations changed. New forms of property came into existence. New portions of society rose into importance. There were in our rural districts rich cultivators, who were not freeholders. There were in our capital rich traders, who were not liverymen. Towns shrank into villages. Villages swelled into cities larger than the London of the Plant agents. Unhappily, while the natural growth of society went on, the artificial polity continued unchanged. The ancient form of the representation remained; and precisely because the form remained, the spirit departed. Then came that pressure almost to bursting���the new wine in the old bottles���the new people under the old institutions.

It is now time for us to pay a decent, a rational, a manly reverence to our ancestors ���not by superstitiously adhering to what they, under other circumstances, did, but by doing what they, in our circumstances, would have done. All history is full of revolutions, produced by causes similar to those which are now operating in England. A portion of the community which had been of no account, expands and becomes strong. It demands a place in the system, suited, not to its former weakness, but to its present power. If this is granted, all is well. If this is refused, then comes the struggle between the young energy of one class, and the ancient privileges of another. Such was the struggle between the Plebeians and the Patricians of Rome. Such was the struggle of the Italian allies for admission to the full rights of Roman citizens. Such was the struggle of our North American colonies against them other country. Such was the struggle which the Tiers Elat of France maintained against the aristocracy of birth. Such was the struggle which the Catholics of Ireland maintained against the aristocracy of creed. Such is the struggle which the free people of colour in Jamaica are now maintaining against the aristocracy of skin.

Such, finally, is the struggle which, the middle classes in England are maintaining against an aristocracy of mere locality���against an aristocracy, the principle of which is to invest 100 drunken, pot-wallopers in one place, or the owner of a ruined hovel in another, with powers which are withheld from cities renowned to the furthest ends of the earth, for the marvels of their wealth and of their industry.

But these great cities, says my hon. friend, the member for Oxford, are virtually, though not directly represented. Are not the wishes of Manchester, he asks, as much consulted as those of any town which sends Members to Parliament? Now, Sir, I do not understand how a power which is salutary when exercised virtually, can be noxious when exercised directly. If the wishes of Manchester have as much weight with us, as they would have under a system which should give Representatives to Manchester, how can there be any danger in giving Representatives to Manchester?

A virtual Representative is, I presume, a man who acts as a direct Representative would act: for surely it would be absurd to say, that a man virtually represents the people of property in Manchester, who is in the habit of saying No, when a man directly representing the people of property in Manchester would say Aye. The utmost that can be expected from virtual Representation is, that it may be as good as direct Representation. If so, why not grant direct Representation to places which, as every body allows, ought, by some process or other, to be represented?

If it be said, that there is an evil in change as change, I answer, that there is also an evil in discontent as discontent. This, indeed, is the strongest part of our case. It is said that the system works well. I deny it. I deny that a system works well, which the people regard with aversion. We may say here, that it is a good system and a perfect system. But if any man were to say so to any 658 respectable farmers or shopkeepers, chosen by lot in any part of England, he would be hooted down, and laughed to scorn. Are these the feelings with which any part of the Government ought to be regarded? Above all, are these the feelings with which the popular branch of the Legislature ought to be regarded?

It is almost as essential to the utility of a House of Commons, that it should possess the confidence of the people, as that it should deserve that confidence. Unfortunately, that which is in theory the popular part of our Government, is in practice the unpopular part. Who wishes to dethrone the King? Who wishes to turn the Lords out of their House? Here and there a crazy radical, whom the boys in the street point at as he walks along.

Who wishes to alter the constitution of this House? The whole people. It is natural that it should be so. The House of Commons is, in the language of Mr. Burke, a check for the people��� not on the people, but for the people. While that check is efficient, there is no reason to fear that the King or the nobles will oppress the people. But if that check requires checking, how is it to be checked? If the salt shall lose its savour, wherewith shall we season it? The distrust with which the nation regards this House may be unjust. But what then? Can you remove that distrust? That it exists cannot be denied. That it is an evil cannot be denied. That it is an increasing evil cannot be denied.

One Gentleman tells us that it has been produced by the late events in France and Belgium; another, that it is the effect of seditious works which have lately been published. If this feeling be of origin so recent, I have read history to little purpose. Sir, this alarming discontent is not the growth of a day or of a year. If there be any symptoms by which it is possible to distinguish the chronic diseases of the body politic from its passing inflammations, all these symptoms exist in the present case. The taint has been gradually becoming more extensive and more malignant, through the whole life-time of two generations. We have tried anodynes. We have tried cruel operations. What are we to try now? Who flatters himself that he can turn this feeling back?

Does there remain any argument which escaped the comprehensive intellect of Mr. Burke, or the subtlety of Mr. Wyndham? Docs there remain any species of coercion which was not tried by Mr. Pitt and by Lord Londonderry?

We have had laws. We have had blood. New treasons have been created. The Press has been shackled. The Habeas Corpus Act has been suspended. Public meetings have been prohibited. The event has proved that these expedients were mere palliatives. You are at the end of your palliatives. The evil remains. It is more formidable than ever.

What is to be done? Under such circumstances, a great measure of reconciliation, prepared by the Ministers of the Crown, has been brought before us in a manner which gives additional lustre to a noble name, inseparably associated during two centuries with the dearest liberties of the English people.

I will not say, that the measure is in all its details precisely such as I might wish it to be; but it is founded on a great and a sound principle. It takes away a vast power from a few. It distributes that power through the great mass of the middle order. Every man, therefore, who thinks as I think, is bound to stand firmly by Ministers, who are resolved to stand or fall with this measure. Were I one of them, I would sooner���infinitely sooner���fall with such a measure than stand by any other means that ever supported a Cabinet.

My hon. friend, the member for the University of Oxford tells us, that if we pass this law, England will soon be a republic. The reformed House of Commons will, according to him, before it has sat ten years, depose the King, and expel the Lords from their House. Sir, if my hon. friend could prove this, he would have succeeded in bringing an argument for democracy, infinitely stronger than any that is to be found in the works of Paine. His proposition is in fact this���that our monarchical and aristocratical institutions have no hold on the public mind of England; that those institutions are regarded with aversion by a decided majority of the middle class. This, Sir, I say, is plainly deducible from his proposition; for he tells us, that the Representatives of the middle class will inevitably abolish royalty and nobility within ten years: and there is surely no reason to think that the Representatives of the middle class will be more inclined to a democratic revolution than their constituents.

Now, Sir, if I were convinced that the great body of the middle class in England look with aversion on monarchy and aristocracy, I should be forced, much against my will, to come to this conclusion, that monarchical and aristocratical institutions are unsuited to this country. Monarchy and aristocracy, valuable and useful as I think them, are still valuable and useful as means, and not as ends. The end of government is the happiness of the people: and I do not conceive that, in a country like this, the happiness of the people can be promoted by a form of government, in which the middle classes place no confidence, and which exists only because the middle classes have no organ by which to make their sentiments known.

But, Sir, I am fully convinced that the middle classes sincerely wish to uphold the Royal prerogatives, and the constitutional rights of the Peers.

What facts does my hon. friend produce in support of his opinion? One fact only���and that a fact which has absolutely nothing to do with the question. The effect of this Reform, he tells us, would be, to make the House of Commons all-powerful. It was all-powerful once before, in the beginning of 1649. Then it cut off the head of the King, and abolished the House of Peers. Therefore, if this Reform should take place, it will act in the same manner.

Now, Sir, it was not the House of Commons that cut off the head of Charles the 1st; nor was the House of Commons then all-powerful. It had been greatly reduced in numbers by successive expulsions. It was under the absolute dominion of the army. A majority of the House was willing to take the terms offered by the King. The soldiers turned out the majority; and the minority���not a sixth part of the whole House���passed those votes of which my hon. friend speaks���votes of which the middle classes disapproved then, and of which they disapprove still.

My hon. friend, and almost all the Gentlemen who have taken the same side with him in this Debate, have dwelt much on the utility of close and rotten boroughs. It is by means of such boroughs, they tell us, that the ablest men have been introduced into Parliament. It is true that many distinguished persons have represented places of this description. But, Sir, we must judge of a form of government by its general tendency, not by happy accidents. Every form of government has its happy accidents. Despotism has its happy accidents. Yet we are not disposed to abolish all constitutional checks, to place an absolute master over us, and to take our chance: whether he may be a Caligula or a Marcus Aurelius.

In whatever way the House of Commons may be chosen, some able men will be chosen in that way who would not be chosen in any other way. If there were a law that the hundred tallest men in England should be Members in Parliament, there would probably be some able men among those who would come into the House by virtue of this law. If the hundred persons whose names stand first in the alphabetical list of the Court Guide were made Members of Parliament, there would probably be able men among them. We read in ancient history, that a very able king was elected by the neighing of his horse. But we shall scarcely, I think, adopt this mode of election.

In one of the most celebrated republics of antiquity���Athens���the Senators and Magistrates were chosen by lot; and sometimes the lot fell fortunately. Once, for example, Socrates was in office. A cruel and unjust measure was brought forward. Socrates resisted it at the hazard of his own life. There is no event in Grecian history more interesting than that memorable resistance. Yet who would have offices assigned by lot, because the accident of the lot may have given to a great and good man a power which he would probably never have attained in any other way?

We must judge, as I said, by the general tendency of a system. No person can doubt that a House of Commons chosen freely by the middle classes will contain many very able men. I do not say, that precisely the same able men who would find their way into the present House of Commons, will find their way into the reformed House���but that is not the question. No particular man is necessary to the State. We may depend on it, that if we provide the country with free institutions, those institutions will provide it with great men.

There is another objection, which, I think, was first raised by the hon. and learned member for Newport (Mr. H. Twiss). He tells us that the elective franchise is property��� that to take it away from a man who has not been judicially convicted of any malpractices is robbery���that no crime is proved against (he voters in the close boroughs���that no crime is even imputed to them in the preamble of the Bill���and that to disfranchise them without compensation, would therefore be an act of revolutionary tyranny. The hon. and learned Gentleman has compared the conduct of the present Ministers to that of those odious tools of power, who, towards the close of the reign of Charles the 2nd, seized the charters of the Whig Corporations.

Now there was another precedent, which I wonder that he did not recollect, both because it was much more nearly in point than that to which he referred, and because my noble friend, the Paymaster of the Forces, had previously alluded to it. If the elective franchise is property���if to disfranchise voters without a crime proved, or a compensation given, be robbery��� was there ever such an act of robbery as the disfranchising of the Irish forty-shilling freeholders? Was any pecuniary compensation given to them? Is it declared in the preamble of the bill which took away their votes, that they had been convicted of any offence? Was any judicial inquiry instituted into their conduct? Were they even accused of any crime?

Or say, that it was a crime in the electors of Clare to vote for the hon. and learned Gentleman who now represents the county of Waterford���was a Protestant forty-shilling freeholder in Louth, to be punished for the crime of a Catholic forty-shilling freeholder in Clare? If the principle of the hon. and learned member for Newport be sound, the franchise of the Irish peasant was property. That franchise, the Ministry under which the hon. and learned Member held office, did not scruple to take away. Will he accuse the late Ministers of robbery? If not, how can he bring such on accusation against their successors?

Every Gentleman, I think, who has spoken from the other side of the House has alluded to the opinions which some of his Majesty's Ministers formerly entertained on the subject of Reform. It would be officious in me, Sir, to undertake the defence of Gentlemen who are so well able to defend themselves. I will only say, that, in my opinion, the country will not think worse either of their talents or of their patriotism, because they have shown that they can profit by experience, because they have learned to see the folly of delaying inevitable changes. There are others who ought to have learned the same lesson. I say, Sir, that, there are those who, I should have thought, must have had enough to last them all their lives of that humiliation which follows obstinate and boastful resistance to measures rendered necessary by the progress of society, and by the development of the human mind. Is it possible that those persons can wish again to occupy a position, which can neither be defended, nor surrendered with honour?

I well remember, Sir, a certain evening in the month of May, 1827. I had not then the honour of a seat in this House; but I was an attentive observer of its proceedings. The right hon. Baronet opposite, (Sir R. Peel) of whom personally I desire to speak with that high respect which I feel for his talents and his character, but of whose public conduct I must speak with the sincerity required by my public duty, was then, as he is now, out of office. He had just resigned the Seals of the Home Department, because he conceived that the Administration of Mr. Canning was favourable to the Catholic claims. He rose to ask whether it was the intention of the new Cabinet to repeal the Test and Corporation Acts, and to Reform the Parliament. He bound up, I well remember, those, two questions together; and he declared, that if the Ministers should either attempt to repeal the Test and Corporation Acts, or bring forward a measure of Parliamentary Reform, he should think it his duty to oppose them to the utmost.

Since that declaration was made nearly four years have elapsed; and what is now the state of the three questions which then chiefly agitated the minds of men? What is become of the Test and Corporation Acts? They are repealed. By whom? By the late Administration. What has become of the Catholic disabilities? They are removed. By whom? By the late Administration. The question of Parliamentary Reform is still behind. But signs, of which it is impossible to misconceive the import, do most clearly indicate, that, unless that question also be speedily settled, property and order, and all the institutions of this great monarchy, will be exposed to fearful peril.

Is it possible, that Gentlemen long versed in high political affairs cannot read these signs? Is it possible that they can really believe that the Representative system of England, such as it now is, will last till the year 1860? If not, for what would they have us wait? Would they have us wait merely that we may show to all the world how little we have profited by our own recent experience? Would they have us wait, that we may once again hit the exact point where we can neither refuse with authority, nor concede with grace? Would they have us wait, that the numbers of the discontented party may become larger, its demands higher, its feeling more acrimonious, its organization more complete? Would they have us wait till the whole tragi-comedy of 1827 has been acted over again; till they have been brought into office by a cry of "No Reform!" to be reformers, as they were once before brought into office by a cry of "No Popery! "to be emancipators? Have they obliterated from their minds���gladly perhaps would some among them obliterate from their minds���the transactions of that year? And have they forgotten all the transactions of the succeeding year?

Have they forgotten how the spirit of liberty in Ireland, debarred from its natural outlet, found a vent by forbidden passages? Have they forgotten how we were forced to indulge the Catholics in all the license of rebels, merely because we chose to withhold from them the liberties of subjects? Do they wait for associations more formidable than that of the Corn Exchange,��� for contributions larger than the Rent,��� for agitators more violent than those who, three years ago, divided with the King and the Parliament, the sovereignty of Ireland? Do they wait for that last and most dreadful paroxysm of popular rage, ���for that last and most cruel test of military fidelity?

Let them wait, if their past experience shall induce them to think that any high honour or any exquisite pleasure is to be obtained by a policy like this.

Let them wait, if this strange and fearful infatuation be indeed upon them,���that they should not see with their eyes, or hear with their ears, or understand with their heart.

But let us know our interest and our duty better.

Turn where we may, ���within,���around,���the voice of great events is proclaiming to us, Reform, that you may preserve:

now, therefore, while every thing at home and abroad forebodes ruin to those who persist in a hopeless struggle against the spirit of the age,

now, while the crash of the proudest throne of the continent is still resounding in our ears,

now, while the roof of a British palace affords an ignominious shelter to the exiled heir of forty kings,

now, while we see on every side ancient institutions subverted, and great societies dissolved,

now, while the heart of England is still sound,

now, while the old feelings and the old associations retain a power and a charm which may too soon pass away,

now, in this your accepted time,

now in this your day of salvation,���take counsel:

not of prejudice,

not of party spirit,

not of the ignominious pride of a fatal consistency,

but of history,

of reason,

of the ages which are past,

of the signs of this most portentous time.

Pronounce in a manner worthy of the expectation with which this great Debate has been anticipated, and of the long remembrance which it will leave behind. Renew the youth of the State. Save property divided against itself. Save the multitude, endangered by their own ungovernable passions. Save the aristocracy, endangered by its own unpopular 1205 power. Save the greatest, and fairest, and most highly civilized community that ever existed, from calamities which may in a few days sweep away all the rich heritage of 60 many ages of wisdom and glory. The danger is terrible. The time is short. If this Bill should be rejected, I pray to God that none of those who concur in rejecting it may ever remember their votes! with unavailing regret, amidst the wreck of laws, the confusion of ranks, the spoliation of property, and the dissolution of social order...

#shouldread

#weekendreading

#democracy

#franchie

Weekend Reading: Judith Shklar: The LIberalism of Fear

Judith Shklar (1989): The Liberalism of Fear: "The liberalism of fear... does not... offer a summum bonum... but it certainly does begin with a summum malum, which all of us know and would avoid if only we could. That evil is cruelty and the fear it inspires...

...To that extent the liberalism of fear makes a universal and especially a cosmopolitan claim, as it historically always has done. What is meant by cruelty here? It is the deliberate infliction of physical, and secondarily emotional, pain upon a weaker person or group by stronger ones in order to achieve some end, tangible or intangible, of the latter.... Public cruelty is not an occasional personal inclination. It is made possible by differences in public power, and it is almost always built into the system of coercion upon which all governments have to rely to fulfill their essential functions. A minimal level of fear is implied in any system of law, and the liberalism of fear does not dream of an end of public, coercive government. The fear it does want to prevent is that which is created by arbitrary, unexpected, unnecessary, and unlicensed acts of force and by habitual and pervasive acts of cruelty and torture performed by military, paramilitary, and police agents in any regime.

Of fear it can be said without qualification that it is universal as it is physiological. It is a mental as well as a physical reaction, and it is common to animals as well as to human beings. To be alive is to be afraid, and much to our advantage in many cases, since alarm often preserves us from danger. The fear we fear is of pain inflicted by others to kill and maim us, not the natural and healthy fear that merely warns us of avoidable pain. And, when we think politically, we are afraid not only for ourselves but for our fellow citizens as well. We fear a society of fearful people.

Systematic fear is the condition that makes freedom impossible, and it is aroused by the expectation of institutionalized cruelty as by nothing else. However, it is fair to say that what I have called "putting cruelty first" is not a sufficient basis for political liberalism. It is simply a first principle, an act of moral intuition based on ample observation, on which liberalism can be built, especially at present. Because the fear of systematic cruelty is so universal, moral claims based on its prohibition have an immediate appeal and can gain recognition without much argument. But one cannot rest.... If the prohibition of cruelty can be universalized and recognized as a necessary condition of the dignity of persons, then it can become a principle of political morality.... What liberalism requires is the possibility of making the evil of cruelty and fear the basic norm of its political practices and prescriptions....

What the liberalism of fear owes to Locke is also obvious: that the governments of this world with their overwhelming power to kill, maim, indoctrinate, and make war are not to be trusted unconditionally ("lions"), and that any confidence that we might develop in their agents must rest firmly on deep suspicion. Locke was not, and neither should his heirs be, in favor of weak governments that cannot frame or carry out public policies and decisions made in conformity to requirements of publicity, deliberation, and fair procedures. What is to be feared is every extralegal, secret, and unauthorized act by public agents or their deputies. And to prevent such conduct requires a constant division and subdivision of political power.

The importance of voluntary associations from this perspective is not the satisfaction that their members may derive from joining in cooperative endeavors, but their ability to become significant units of social power and influence that can check, or at least alter, the assertions of other organized agents, both voluntary and governmental.

The separation of the public from the private is evidently far from stable here, as I already noted, especially if one does not ignore, as the liberalism of fear certainly does not, the power of such basically public organizations as corporate business enterprises. These of course owe their entire character and power to the laws, and they are not

public in name only. To consider them in the same terms as the local mom and pop store is unworthy of serious social discourse. Nevertheless, it should be remembered that the reasons we speak of property as private in many cases is that it is meant to be left to the discretion of individual owners as a matter of public policy and law, precisely

because this is an indispensable and excellent way of limiting the long arm of government and of dividing social power, as well as of securing the independence of individuals. Nothing gives a person greater social resources than legally guaranteed proprietorship. It cannot be unlimited; because it is the creature of the law in the first place, and also because it serves a public purpose���the dispersion of power.

Where the instruments of coercion are at hand, whether it be through the use of economic power, chiefly to hire, pay, fire, and determine prices, or military might in its various manifestations, it is the task of a liberal citizenry to see that not one official or unofficial agent can intimidate anyone, except through the use of well-understood and accepted legal procedures. And that even then the agents of coercion should always be on the defensive and limited to proportionate and necessary actions that can be excused only as a response to threats of more severe cruelty and fear from private criminals.

It might well seem that the liberalism of fear is radically consequentialist in its concentration on the avoidance of foreseeable evils. As a guide to political practices that is the case, but it must avoid any tendency to offer ethical instructions in general. No form of liberalism has any business telling the citizenry to pursue happiness or even to

define that wholly elusive condition. It is for each one of us to seek it or reject it in favor of duty or salvation or passivity, for example. Liberalism must restrict itself to politics and to proposals to restrain potential abusers of power in order to lift the burden of fear and favor from the shoulders of adult women and men, who can then conduct their lives in accordance with their own beliefs and preferences, as long as they do not prevent others from doing so as well...

#shouldread

August 9, 2018

Comment of the Day: Kaleberg: Optiomization Problem Solve...

Comment of the Day: Kaleberg: Optiomization Problem Solves You: "This discussion assumes that the optimization problem is about finding the optimal solution...

...A centrally planned system would be considered a failure if it produced too many size 9 shoes and not enough size 10 shoes for one shoe replacement season. Capitalism would be more successful because it would be willing to accept a solution that would deny shoes to a broad class of the population as long as shoe factory profits were high. The two systems play different games on different fields...

#shouldread

Pam Weintraub: The roots of writing lie in hopes and drea...

Pam Weintraub: The roots of writing lie in hopes and dreams, not in accounting: "In the four wellsprings of writing, it never (as far as we know) sprang forth as fully phonographic but evolved to become that���there���s usually some kind of proto-writing, and some kind of proto-proto-writing...

...I like to think of writing as a layered invention.... A durable mark on a surface. Humans have been doing this for at least 100,000 years.... Then... let���s make this mark different... and assign it a meaning.... Then there���s the linguistic one: let���s realise that a sound, a syllable and a word are all things in the world that can be assigned a graphic symbol. This invention depends on the previous ones, and itself is made of innovations, realisations, solutions and hacks. Then comes the functional invention: let���s use this set of symbols to write a list of captives��� names, or a contract about feeding workers, or a letter to a distant garrison commander. All these moves belong to an alchemy of life that makes things go boom.... Early writing in Mesopotamia, for instance, had no overtly political function.... Instead, for the first 300-400 years of early cuneiform texts in the region (from about 3300-2900 BCE)... a bookkeeping function for managing temple-factories of the day....

Tokens showed up in Neolithic archaeological sites from 8000 BCE.... Schmandt-Besserat... realised... they were markers for objects: one cone per unit of grain, one diamond per unit of honey.... Tokens... were stored in groups... sealing them into hollow clay balls... obvious drawback that the contents of a sealed envelope can���t be checked, early accountants pressed the tokens into the soft, wet surface of the envelope. By the fourth millennium, scribes realised that the impressed signs made the envelopes redundant....

Then one more step of abstraction completed the journey: create written signs that capture speech-sounds and word-meanings.... Early states functioned without writing for nearly 3,000 years before the invention of cuneiform because they had the token system for counting. And tokens didn���t need the... state to develop.... Counting that precedes complex economic organisation as well as phonetic writing that precedes political functions...

#shouldread

Cosma Shalizi (2012): In Soviet Union, Optimization Probl...

Cosma Shalizi (2012): In Soviet Union, Optimization Problem Solves You: "Both neo-classical and Austrian economists make a fetish (in several senses) of markets and market prices. That this is crazy is reflected in the fact that even under capitalism, immense areas of the economy are not coordinated through the market...

...There is a great passage from Herbert Simon in 1991 which is relevant here:

Suppose that [���a mythical visitor from Mars���] approaches the Earth from space, equipped with a telescope that revels social structures. The firms reveal themselves, say, as solid green areas with faint interior contours marking out divisions and departments. Market transactions show as red lines connecting firms, forming a network in the spaces between them. Within firms (and perhaps even between them) the approaching visitor also sees pale blue lines, the lines of authority connecting bosses with various levels of workers. As our visitors looked more carefully at the scene beneath, it might see one of the green masses divide, as a firm divested itself of one of its divisions. Or it might see one green object gobble up another. At this distance, the departing golden parachutes would probably not be visible.

No matter whether our visitor approached the United States or the Soviet Union, urban China or the European Community, the greater part of the space below it would be within green areas, for almost all of the inhabitants would be employees, hence inside the firm boundaries. Organizations would be the dominant feature of the landscape. A message sent back home, describing the scene, would speak of ���large green areas interconnected by red lines.��� It would not likely speak of ���a network of red lines connecting green spots.���[6]

This is not just because the market revolution has not been pushed far enough. (���One effort more, shareholders, if you would be libertarians!���) The conditions under which equilibrium prices really are all a decision-maker needs to know, and really are sufficient for coordination, are so extreme as to be absurd.(Stiglitz is good on some of the failure modes.) Even if they hold, the market only lets people ���serve notice of their needs and of their relative strength��� up to a limit set by how much money they have. This is why careful economists talk about balancing supply and ���effective��� demand, demand backed by money.

This is just as much an implicit choice of values as handing the planners an objective function and letting them fire up their optimization algorithm. Those values are not pretty. They are that the whims of the rich matter more than the needs of the poor; that it is more important to keep bond traders in strippers and cocaine than feed hungry children. At the extreme, the market literally starves people to death, because feeding them is a less ���efficient��� use of food than helping rich people eat more. I don���t think this sort of pathology is intrinsic to market exchange; it comes from market exchange plus gross inequality.... There is... a strong case to be made for egalitarian distributions of resources being a complement to market allocation. Politically, however, good luck getting those to go together...

#shouldread

#economicsgoneright

Mass Politics and "Populism": An Outtake from "Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Long Twentieth Century"

Once the people���the male people at first, and the white people overwhelmingly, and the adult people always, that is���had the vote, what were they going to do with it?

5.2.1: Inequality in the First Gilded Age: The coming of (white, male) democracy in the North Atlantic was all mixed up with the coming of modern industry���the move out of agriculture and into industrial and service occupations���the coming of the modern city (the move from the farm to someplace more densely populated), and the coming of heightened within-nation income inequality.

America in 1776 was, if you were a native-born adult white male, a remarkably egalitarian country. The richest one percent of households owned perhaps ���fteen percent of the total wealth in the economy���including the ���human wealth��� of their slaves iu their share of property but not in the aggregate wealth total. (After all, a slave is valuable property to the slaveowner���but equally or rather more so unproperty, antiproperty, negative property to the slave: a slave society can easily have a minority owning more than 100% of the national wealth once this is taken into account.) A top one percent owning only some fifteen percent of wealth is a very low value for such a statistic: the United States today is somewhere north of 40% of wealth owned by the richest one percent of households.

Inequality among white males at least did not grow that much as America���s north began to industrialize in the years up through the Civil War���and the Emancipation Proclamation and the thirteenth amendment gave a substantial equalizing push to the economy. In the aftermath of the Civil War the top one percent of households appear to have held perhaps a quarter of the wealth of the country.

By 1900, however, the United States was as unequal an economy in relative terms as���well, as it was at the peak of the housing bubble, or today. The United States had become the Gilded Age country of industrial princes, and immigrants living in tenements. On the one hand, Andrew Carnegie built the largest mansion in Newport, Rhode Island with gold water faucets. On the other hand, 146 largely-immigrant workers died in the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory ���re in Manhattan because the exits had been locked to keep workers from taking fabric out of the building in order to make their own clothes.

Surveys and guesses suggest that in the first decade of the twentieth century the richest one percent of U.S. households held something like half of national wealth. Attempts to count the wealth of the merchant princes themselves reinforce the suspicion that the pre-World War I U.S. was more unequal than at any time before or since. John D. Rockefeller was some four times richer relative to the wages of the average American of his day than the likes of William H. Gates or Jeff Bezos are today. (And Rockefeller was some ten times richer relative to the total size of the U.S. economy.)

5.2.2: An ���Aristocracy of Manufactures���: This country of immigrants and plutocrats was very different from a country of yeoman farmers (among, once again, native-born adult white guys: all the stuff about Americans pulling together to raise each others��� barns and respect each others��� claims ignore the fact that the first rule of property law was that no claim by a Mexican or an Amerindian need be respected���if they were then the heir of Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo would be in the same position in California today that His Grace Gerald Grosvener, 6th Duke of Westminster is in Britain today). For at its beginning the United States had been a land of yeoman farmers in its Founding Fathers��� imaginations, and in large part in reality.

How would things change when the society ceased to be one with a prosperous working and a broad middle class, and an elite made up of hard-working lawyers and merchants on the one hand and a few plutocratic slaveholders on the other? How would things work when the inheritors of land or resources or capital lorded it over everybody else���and bought politicians for small change? Alexis de Tocqueville, a keen-eyed commentator on American society in the ���rst half of the nineteenth century and author of Democracy in America, had feared the growth of such a class of plutocrats, such an ���aristocracy of manufacturers���:

The territorial aristocracy of past ages was obliged by law, or thought itself obliged by custom, to come to the help of its servants and relieve their distress. But the industrial aristocracy of our day, when it has impoverished and brutalized the men it uses, abandons them in time of crisis to public charity to feed them.... Between workman and master there are frequent relations but no true association. I think that, generally speaking, the manufacturing aristocracy which we see rising before our eyes is one of the hardest that have appeared on the earth...

In the United States the rising concentration of wealth during the pre-World War I era provoked a widespread feeling that something, somewhere had gone wrong with the country's development. Abraham Lincoln had thought he lived, and for the most part had lived, in an America in which:

the prudent, penniless beginner in the world labors for wages awhile, saves a surplus with which to buy tools or land for himself, then labors on his own account another while, and at length hires another new beginner to help him���

Since the outcome in Lincoln���s day was a largely middle-class society, Lincoln and his era:

[took] it that it is best for all to leave each man free to acquire property as fast as he can. Some will get wealthy. I don���t believe in a law to prevent a man from getting rich; it would do more harm than good. So while we do not propose any war on capital, we do wish to allow the humblest man an equal chance to get rich with everybody else���

As historian Ray Ginger writes:

Lincoln��� stood for an open society in which all men would have an equal chance���. ���I am a living witness,��� he told a regiment of soldiers, ���that any one of your children may look to come here as my father���s child has.������ From the Civil War to 1900, Abraham Lincoln dominated the visions of the good society which were being projected to exonerate the successful and to inspire the young���. But during those very decades��� the social realities that had shaped the Lincoln ideal were being chipped away���

And he quotes a Chicago laborer:

���Land of opportunity,��� you say. You know well my children will be where I am���that is, if I can keep them out of the gutter���

Many of the prosperous (and many of the native-born not-so-prosperous) blamed foreigners for what was going wrong with America in the late nineteenth century: aliens born in China, Japan, Italy, Spain, Poland, and Russia were:

incapable of speaking English,

or understanding American values,

or contributing to American society,

and were probably genetically feeble-minded too,

with children incapable of ever becoming smart and well-educated enough to be full partners in American civilization���

especially the Chinese and the Jews.

Don���t laugh���that���s what they argued, and that was one reason that if you were French or British you had an easy time fleeing Europe for America in the late 1930s on the eve of World War II, but the gates were in all likelihood shut against you if you were Russo- or Polish- or even German-Jewish.

5.2.3: Populists and Progressives: Many of the middle class, especially the farmers, blamed the rich, the easterners, and the bankers for what was going wrong with late nineteenth-century America. The Populists of the 1890s blamed the eastern bankers, the gold standard, and the monopolists. They sought the free coinage of silver at a ratio of 16-to-1 to boost the money supply, lower interest rates, and raise farm prices. They sought antitrust to bust monopolies and restore competition. They sought railroad and other forms of rate regulation to make sure that the largely-rural backbone of real Americans were not exploited by those in the cities with market power���whether rail barons, manufacturing monopolies, or bankers.

The Progressives of the 1900s sought reforms to try to diminish the power of what they saw as a wealthy-would be aristocracy: the ���malefactors of great wealth��� in Theodore Roosevelt���s words. They sought an expanded government role to protect the environment, a progressive income tax, curbs on financial manipulation, and also to make the world safe for democracy. The Progressives got their chance when the assassination of William McKinley moved Republican Progressive Theodore Roosevelt out of the Vice Presidency���the powerless job dismissed by John Nance Garner as ���a bucket of warm piss������and into the White House in 1899, and then again when Roosevelt���s disgust at his successor Taft���s betrayal of Progressive values and sharp, corrupt Republican National Convention practice led him to throw the presidency to Democratic Progressive Woodrow Wilson in 1912.

But the Populists and the Progressives remained minority political currents in America until the coming of the Great Depression. In the meantime, the voters continued to narrowly elect Republican presidents���or that triangulating bastard Grover Cleveland���who were more-or-less satisfied with American economic and social developments, and who believed that ���the business of America is business.���

There were some Democrats who sought a more equal distribution of income and more action by the government to put its thumb on the scales of the market in the interest of greater equality. They failed to wield political power even though they had a solid lock on the votes of the south after the disenfranchisement of the 1870s and a pretty solid lock on the votes of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. Many of the southern Democrats were Democrats only because Lincoln had freed the slaves. And while there were many among the northern Republicans who were Republican only because Lincoln had freed the slaves, they by and large sought a good, competent, activist government and not a more equal America.

Thus while the Populist and Progressive eras win the battle for mindshare in the history books, they failed to make that much of an impact on American policy before World War I���but the availability of the Populist and Progressive agendas made the shift in American politics in response to the Great Depression a generation later rapid and substantial. Pretty much every left-of-center initiative that had been proposed between 1885 and 1914 was dusted off and given a try in Franklin Delano Roosevelt���s New Deal.

5.2.4: Chicagoland: So how did politics and economics interact at the bleeding edge���at the most-rapidly growing and industrializing place on the pre-World War I earth, in that era���s counterpart to today���s Shanghai, in Chicago?

In 1840, when the Illinois and Michigan canal opened connecting the Mississippi River with the Great Lakes, Chicago had a population of 4000. In 1871 Mrs. O���Leary���s cow burned down a third of the city. In 1885 Chicago built the world���s first steel-framed skyscraper.

By 1900 Chicago had a population of two million. 70 percent of its citizens had been born outside the United States.

On May 1, 1886, the American Federation of Labor declared a general strike to win the eight-hour workday. On May 3, 400 police officers protecting the McCormick farm equipment factory and its strikebreakers opened fire on a crowd, killing six. The next day eight police officers were murdered by an anarchist bomb at a rally in protest of police violence and in support of the striking workers���and the police opened fire at the crowd and killed perhaps twenty civilians, largely immigrants, largely non-English speaking (nobody seems to have counted). A kangaroo court convicted eight innocent (we now believe) left-wing politicians and organizers of murder. Five were hanged.

In 1889 Samuel Gompers, President of the American Federation of Labor asked the world socialist movement���the ���Second International������to set aside May 1 every year as the day for a great annual international demonstration in support of the eight-hour workday and in memory of the victims of police violence in Chicago in 1886.

In the summer of 1894 the Democratic Party President Grover Cleveland persuaded Congress to make a national holiday in recognition of the place of labor in American society���not on the International Workers��� Day that was May 1 in commemoration of Chicago 1889, but rather a moveable feast on the first Monday in September instead.

In 1893 the new Democratic Governor of Illinois, John Peter Altgeld���the first Democratic Party governor since 1856, the first Chicago resident governor ever, and the first foreign-born governor ever���pardoned the three still-living ���Haymarket Bombers,��� saying that the real reason for the bombing was the out-of-control violence by the Pinkerton Security Company guards hired by McCormick and others.

Who was this John Peter Altgeld who pardons convicted anarchists, and blames violence on the manufacturing princes of the midwest and their hired armed goons, and is Governor of Illinois?

5.2.5: The Career of John Peter Altgeld: Altgeld was born in Germany. His parents moved him to Ohio in 1848 at the age of three months. He shows up in the Union Army during the Civil War, at Fort Monroe in the Virginia tidewater country, where he caught a lifelong case of malaria. After the war he shows up finishing high school, as a roving railroad worker, as a schoolteacher, and somewhere in there he read the law. In 1872 he is the city attorney of Savannah, Missouri. In 1874 he is county prosecutor. In 1875 he shows up in Chicago as the author of Our Penal Machinery and Its Victims. 1884 sees him as an unsuccessful Democratic candidate for Congress���and a strong supporter of Democratic presidential candidate Grover Cleveland.

In 1886 he wins election as a judge on Cook County���s Superior Court. And somewhere in there he becomes rich as a real estate speculator and a builder���with his biggest holding being the tallest building in Chicago in 1891, the sixteen-story Unity Building at 127 N. Dearborn St. As governor, Altgeld lobbied for and persuaded the legislature to enact the then-most stringent child labor and workplace safety laws in the nation, increased state funding for education, and appointed women to senior state government positions.

The largely-Republican and Republican-funded press condemned John Peter Altgeld for his Haymarket pardon. For the rest of his life he was, to middle-class newspaper readers nationwide and especially on the east coast, the foreign-born alien anarchist, socialist, murderous governor of Illinois.

On May, 11, 1894, workers of the Pullman Corporation, manufacturer of sleeping cars and equipment, went on strike rather than accept wage cuts. Altgeld���s friend Clarence Darrow wrote in his autobiography of how the strike looked from his perspective, and how he wound up as the lawyer of the strikers, the United Railroad Assocation, and their leader Eugene V. Debs:

I became the general attorney of the Chicago and North-Western Railway Company.... All sorts of questions were submitted to me... the liability of the company, in cases of personal injuries, in claims for lost freight, in the construction of the statutes and ordinances, and in all the numerous matters that affect the interest of railroads.... [The strike caused] a general interruption of railroad traffic.... The Chicago and North-Western Railway Company was involved with all the rest of the roads, and all who came to the offices thought and talked of little else besides the strike....