Emily Hauser's Blog, page 2

April 2, 2016

#MythMonth

Check out this page of the website, or visit my Twitter feed at @ehauserwrites for a whole month of Greek myths – all in only 140 characters! Fabulous illustrations provided by the very talented Dr. Helen Forte.

Published on April 02, 2016 10:17

March 28, 2016

Giveaway! – Part 1 of 'For the Most Beautiful'

This Easter Monday I'm giving away 10 FREE digital copies of Part 1 of For the Most Beautiful – so if it's been sitting on your to-read list, or you just want something to curl up with this Easter weekend, why not enter to win? Just hop over to my Twitter page @ehauserwrites and retweet to win!

Happy Easter! x

Happy Easter! x

Published on March 28, 2016 06:30

March 21, 2016

A step-by-step guide to the translations of Homer's Iliad

Following on from last week's post on why it matters which translation of the Iliad you read, here's your step-by-step guide to the different translations of Homer's Iliad, from Lattimore's classic 1951 version to Caroline Alexander's recent 2016 translation. Use it to find which version of the Iliad you should pick off the shelf if you're a newcomer to Homer, or which translation you should choose if you're ready to dive a bit deeper into the poetry of the Iliad.  Richmond Lattimore, 1951. The Iliad of Homer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (reprinted 2011).

Richmond Lattimore, 1951. The Iliad of Homer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (reprinted 2011).

Ideal for: Beginners

Buy here

Lattimore’s translation, originally published in 1951 and republished in a new edition in 2011 with an introduction by the classicist Richard Martin, is a classic (it was also the translation I read at school). Renowned for its fluent, clean verse, this edition is also exceptionally useful for those who want to get to grips with Homer’s world and the world of the Trojan War, with maps, glossary and line-by-line commentary included at the back. Christopher Logue, 1962. War Music: An Account of Homer’s Iliad. London: Faber & Faber.

Christopher Logue, 1962. War Music: An Account of Homer’s Iliad. London: Faber & Faber.

Ideal for: Literary enthusiasts

Buy here

This is less of a translation and more a literary interpretation of the Iliad by the poet Christopher Logue – but its vivid, staccato-like, very modern feel may appeal to readers who are looking for a literary re-imagining of Homer’s epic which nevertheless stays close to the original plot-line. Robert Fitzgerald, 1974. Homer: The Iliad. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Robert Fitzgerald, 1974. Homer: The Iliad. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ideal for: Beginners

Buy here

Another classic translation with an introduction by renowned Homerist G. S. Kirk, including maps, bibliography and a glossary. Fitzgerald’s emphasis in his translation was on channelling the immediacy – the vividness – of the Greek into English: he once said in an interview, ‘I wanted the Greekness of the thing to come across’. This is a great translation for readers who want the feeling of reading Homer without too much poetic interpolation. Robert Fagles, 1990. The Iliad. London: Penguin Books.

Robert Fagles, 1990. The Iliad. London: Penguin Books.

Ideal for: Intermediate

Buy here

Fagles’ translation is one of my favourites – it doesn’t provide the easiest access to the text, but it sounds beautiful read aloud and if you’re already familiar with the essentials of the Iliad it’s a great way to experience the rhythm, flow and sound of Homer’s poetry. Includes an introduction and notes by classicist Bernard Knox.

Stanley Lombardo, 1997. The Iliad. Indianapolis: Hackett.

Stanley Lombardo, 1997. The Iliad. Indianapolis: Hackett.

Ideal for: Beginners/Intermediate

Buy here

A former professor of Classics, Lombardo’s feel for the rhythm and sound of the ancient Greek is indisputable – and his Iliad, with its modern, vernacular feel, is likely to appeal to students and those already familiar with the Iliad alike. Like Fagles’ translation, Lombardo’s version is intended to be read aloud, and comes in both an audiobook version (performed by Lombardo himself) and in the form of a shortened selection. Caroline Alexander, 2016. The Iliad. New York: Vintage.

Caroline Alexander, 2016. The Iliad. New York: Vintage.

Ideal for: Beginners/Students

Buy here

Notable as the first translation of the Iliad ever to have been published by a woman, Alexander’s Iliad is admirable in its own right. Clearly articulated and in a sparse style that echoes the archaic diction of the Homeric Iliad, one of the most useful features of Alexander’s translation is its line-by-line fidelity to the Homeric text, making it a valuable resource for students wishing to study the ancient Greek.

Richmond Lattimore, 1951. The Iliad of Homer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (reprinted 2011).

Richmond Lattimore, 1951. The Iliad of Homer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (reprinted 2011).Ideal for: Beginners

Buy here

Lattimore’s translation, originally published in 1951 and republished in a new edition in 2011 with an introduction by the classicist Richard Martin, is a classic (it was also the translation I read at school). Renowned for its fluent, clean verse, this edition is also exceptionally useful for those who want to get to grips with Homer’s world and the world of the Trojan War, with maps, glossary and line-by-line commentary included at the back.

Christopher Logue, 1962. War Music: An Account of Homer’s Iliad. London: Faber & Faber.

Christopher Logue, 1962. War Music: An Account of Homer’s Iliad. London: Faber & Faber.Ideal for: Literary enthusiasts

Buy here

This is less of a translation and more a literary interpretation of the Iliad by the poet Christopher Logue – but its vivid, staccato-like, very modern feel may appeal to readers who are looking for a literary re-imagining of Homer’s epic which nevertheless stays close to the original plot-line.

Robert Fitzgerald, 1974. Homer: The Iliad. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Robert Fitzgerald, 1974. Homer: The Iliad. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Ideal for: Beginners

Buy here

Another classic translation with an introduction by renowned Homerist G. S. Kirk, including maps, bibliography and a glossary. Fitzgerald’s emphasis in his translation was on channelling the immediacy – the vividness – of the Greek into English: he once said in an interview, ‘I wanted the Greekness of the thing to come across’. This is a great translation for readers who want the feeling of reading Homer without too much poetic interpolation.

Robert Fagles, 1990. The Iliad. London: Penguin Books.

Robert Fagles, 1990. The Iliad. London: Penguin Books.Ideal for: Intermediate

Buy here

Fagles’ translation is one of my favourites – it doesn’t provide the easiest access to the text, but it sounds beautiful read aloud and if you’re already familiar with the essentials of the Iliad it’s a great way to experience the rhythm, flow and sound of Homer’s poetry. Includes an introduction and notes by classicist Bernard Knox.

Stanley Lombardo, 1997. The Iliad. Indianapolis: Hackett.

Stanley Lombardo, 1997. The Iliad. Indianapolis: Hackett.Ideal for: Beginners/Intermediate

Buy here

A former professor of Classics, Lombardo’s feel for the rhythm and sound of the ancient Greek is indisputable – and his Iliad, with its modern, vernacular feel, is likely to appeal to students and those already familiar with the Iliad alike. Like Fagles’ translation, Lombardo’s version is intended to be read aloud, and comes in both an audiobook version (performed by Lombardo himself) and in the form of a shortened selection.

Caroline Alexander, 2016. The Iliad. New York: Vintage.

Caroline Alexander, 2016. The Iliad. New York: Vintage.Ideal for: Beginners/Students

Buy here

Notable as the first translation of the Iliad ever to have been published by a woman, Alexander’s Iliad is admirable in its own right. Clearly articulated and in a sparse style that echoes the archaic diction of the Homeric Iliad, one of the most useful features of Alexander’s translation is its line-by-line fidelity to the Homeric text, making it a valuable resource for students wishing to study the ancient Greek.

Published on March 21, 2016 09:20

March 18, 2016

Which Iliad should I read? – A guide to the translations of Homer’s Iliad

It can be disorientating to say the least when you walk into a bookshop and see the sheer numbers of different translations of the Iliad on the shelf. How on earth are you supposed to pick one – and aren’t they all translations of the same text anyway?

It can be disorientating to say the least when you walk into a bookshop and see the sheer numbers of different translations of the Iliad on the shelf. How on earth are you supposed to pick one – and aren’t they all translations of the same text anyway?Does it really matter which one you choose?

Well, the answer to that is yes – and no. In the end, you’re reading Homer’s Iliad, and if you just want to cut to the chase and get to the content of the story then you will get the same timeless tale whichever translation you pick: the famous story of Achilles’ rage, the devastating siege of Troy, and Hector’s tragic death.

But, to me at least, the Iliad is so much more than just its plot. It’s the rhythm of the ancient Greek poetry, written in a dialect that would have sounded old-fashioned even by the time democracy came to Athens in around 500 BC. It’s the uniqueness of the epithets – ‘the wine-dark sea’, ‘swift-footed Achilles’, and all the other well-known collocations. It’s the sound of the words – and since I’m lucky enough to have studied ancient Greek, that’s something that I think really lies at the heart of the poetry.

I still remember the first time I really realised how amazing – just how unbelievably mind-blowing – it is to be reading the words of a poet who was writing over 2500 years ago. Just think about that. 2500 years! That’s more than twice the time that has passed between the Battle of Hastings in 1066 and now. And we’re still reading the words they wrote, the stories they told. I remember revising for my Greek GCSE at my grandparents’ house when it suddenly hit me – this is it! I’m reading Homer! I’m listening in to the past. And then I sat down and read aloud the opening lines of the Iliad, as they were meant to be heard – savouring every beat of the metre, every poetic word-choice, every formulaic phrase (glaukopis Athene is one of my favourites – ‘Athena with the grey-green eyes’).

And if you want to get a flavour of that, then you’ll have to look a little further.

Before I go into the different merits of each translation in next week’s post – and I’m not saying one is better than the other, only that you’ll get different things from each of them – I’ll dive into a quick example that should give you an idea of what a difference a translation can make.

At the beginning of book 16 of the Iliad, Patroclus, Achilles’ companion, comes to him weeping. Homer uses a simile to describe the flow of Patroclus’ tears (I’ve given you the transliterated Greek, and then a literal translation below):

dakrua therma cheón hós te kréné melanudros,

hé te kat’ aigilipos petrés dnoferon cheei hudór.

hot tears pouring like a spring of black water,

which down a goatless (i.e. steep) rock pours dark water.

Here are a couple of different translations of those lines, in no particular order: … streaming

warm tears – like a shaded mountain-spring

that makes a rock-ledge run with dusky water.

— Robert Fitzgerald … weeping,

His face like a sheer rock where the goat trails end

And dark springwater washes down the stone.

— Stanley Lombardo … wept warm tears, like a spring dark-running

that down the face of a rock impassable drips its dim water…

— Richmond Lattimore

… wept warm tears like a dark spring running down

some desolate rock face, its shaded currents flowing.

— Robert Fagles

You might say it doesn’t matter very much whether you compare the tears streaming down Patroclus’ face to a spring running down ‘a sheer rock where the goat trails end’ or ‘a rock-ledge’. You might even omit it entirely, as Christopher Logue does in Patrocleia. And of course it doesn’t affect the plot of the Iliad at all. But to me, there’s a huge difference between the prosaic ‘rock-ledge’ of Fitzgerald’s translation and Lombardo’s ‘sheer rock where the goat trails end’ – bringing out, as it does, the hidden resonances of the Greek word aigilipos, ‘left by goats’, meaning a mountain so steep that not even goats can climb it. To me, that single word provides us with a little glimpse into Homer’s world – a world where goats scrambled over rocks, their bells clanging at their necks, teetering on precipices over the deep valleys of Greece. With one word, we are thrown back into a peaceful world where the Greek soldiers were still simply farmers and herdsmen, tending to their flocks on the rugged hilltops of the Greek landscape. And the cause of Patroclus’ grief – the deaths of his comrades – suddenly becomes all the more poignant, because you know the life that they have lost.

In summary, then, it depends what you’re looking for – which Iliad you want to read. If you’re a newcomer to the ancient Greek world, searching for a fluent translation which gives you all the essentials of the Iliadic plot, you’ll probably want a different translation from someone who’s looking to read slowly and interpret every word for its nuances and impact on the poem’s interpretation.

Coming next week: a step-by-step how-to guide to the translations of the Iliad. Which translation of the Iliad do you like best, and why? Comment below or send me a tweet at @ehauserwrites – I’d love to hear from you!

Published on March 18, 2016 09:31

February 18, 2016

For the Most Beautiful coming soon to the US!

This is just a quick, but very exciting announcement – I am VERY pleased to be able to say that For the Most Beautiful will be coming to the US soon with Pegasus Books! Exact dates to be confirmed. I am so excited to reach out to all of you in the US and can't wait for For the Most Beautiful to make its way across the pond!

This is just a quick, but very exciting announcement – I am VERY pleased to be able to say that For the Most Beautiful will be coming to the US soon with Pegasus Books! Exact dates to be confirmed. I am so excited to reach out to all of you in the US and can't wait for For the Most Beautiful to make its way across the pond!More details coming soon...

Published on February 18, 2016 09:29

June 11, 2014

The Ruins of Troy

You can also read Emily's blog, "Missives from Iris", online at www.irisonline.org.uk/index.php/blog A few weeks ago I was lucky enough to visit the ruins of Troy in Turkey. It’s a stunning site, like an archaeologist’s playground – full of ruined walls, towers, and houses, with beautiful views out over the Trojan plain and the sea. Standing there on the north-east tower, it was easy to imagine Helen as she is described in the third book of the Iliad, gazing out over the battle-plain, surrounded by Trojan advisors and speaking with the Trojan king, Priam.

First, though, a bit of historical background to give you some context. For over 1500 years, the city of Troy was thought to have been a myth. Scholars believed that the Trojan War, the epic ten-year battle which inspired Homer’s famous poem, the Iliad, was a poetic fiction; a story told to enchant the imagination, and nothing more. But one man thought differently. His name was Heinrich Schliemann, and he was a German businessman with a firm belief in the truth of the Homeric texts. When Schliemann travelled to the north-western coast of Turkey in 1868 in search of Troy, he met a British diplomat and archaeologist by the name of Frank Calvert. Calvert told him that he had unearthed several finds on the hill of Hisarlik, and that it might be worth starting there.

Schliemann took Calvert’s advice and began digging on Hisarlik. So desperate was he to discover the Troy of Homer, and so certain that it would be buried in the very deepest layers of the mound of Hisarlik, that he took dynamite to the hill and blew it up to get in faster! As the smoke cleared, Schliemann went in to take a closer look – and what he found was beyond his wildest dreams. Schliemann was ecstatic. He had discovered walls, a beautiful stone ramp, and, to top it all off, a treasure-trove of gold including stunning jewellery that he immediately dubbed “The Jewels of Helen”. He wrote at once to the major newspapers, declaring that he had discovered Homer’s Troy.

Unfortunately for Schliemann, however, it soon became clear that not only was he wrong – he was digging a thousand years too deep! It was a mortifying mistake, not least because he had unwittingly blown up most of the remains of Homer’s Troy in his hurry to get to the bottom of the mound.

What we have today, then, is not just the Troy of Homer, but all the cities that existed before it as well as some that were built on top of it later. Imagine a Victoria Sponge cake with lots and lots of layers. The earliest layers, built around 3000 BCE, were the first layer of the cake. Each successive layer was built on top of the previous city (it was much easier just to build on top than to remove all the buildings), until Homer’s Troy, which was the sixth layer (archaeologists call it Troy VI). After Homer’s Troy, there were four more layers, before the site fell out of use and it disappeared under grass and wildflowers. Schliemann’s trench, blown into the site with dynamite, essentially cut a slice out of the cake leaving only the very bottom layer behind. What we have now are bits and pieces of each layer which we have to puzzle together ourselves as we go around the site – a few remains from Troy VI, Homer’s Troy, as well as some very early remains from Troy I and II (the first two layers), and some later Roman remains (Troy VIII and IX).

So what are you waiting for? Let’s have a look around the site!

First, though, a bit of historical background to give you some context. For over 1500 years, the city of Troy was thought to have been a myth. Scholars believed that the Trojan War, the epic ten-year battle which inspired Homer’s famous poem, the Iliad, was a poetic fiction; a story told to enchant the imagination, and nothing more. But one man thought differently. His name was Heinrich Schliemann, and he was a German businessman with a firm belief in the truth of the Homeric texts. When Schliemann travelled to the north-western coast of Turkey in 1868 in search of Troy, he met a British diplomat and archaeologist by the name of Frank Calvert. Calvert told him that he had unearthed several finds on the hill of Hisarlik, and that it might be worth starting there.

Schliemann took Calvert’s advice and began digging on Hisarlik. So desperate was he to discover the Troy of Homer, and so certain that it would be buried in the very deepest layers of the mound of Hisarlik, that he took dynamite to the hill and blew it up to get in faster! As the smoke cleared, Schliemann went in to take a closer look – and what he found was beyond his wildest dreams. Schliemann was ecstatic. He had discovered walls, a beautiful stone ramp, and, to top it all off, a treasure-trove of gold including stunning jewellery that he immediately dubbed “The Jewels of Helen”. He wrote at once to the major newspapers, declaring that he had discovered Homer’s Troy.

Unfortunately for Schliemann, however, it soon became clear that not only was he wrong – he was digging a thousand years too deep! It was a mortifying mistake, not least because he had unwittingly blown up most of the remains of Homer’s Troy in his hurry to get to the bottom of the mound.

What we have today, then, is not just the Troy of Homer, but all the cities that existed before it as well as some that were built on top of it later. Imagine a Victoria Sponge cake with lots and lots of layers. The earliest layers, built around 3000 BCE, were the first layer of the cake. Each successive layer was built on top of the previous city (it was much easier just to build on top than to remove all the buildings), until Homer’s Troy, which was the sixth layer (archaeologists call it Troy VI). After Homer’s Troy, there were four more layers, before the site fell out of use and it disappeared under grass and wildflowers. Schliemann’s trench, blown into the site with dynamite, essentially cut a slice out of the cake leaving only the very bottom layer behind. What we have now are bits and pieces of each layer which we have to puzzle together ourselves as we go around the site – a few remains from Troy VI, Homer’s Troy, as well as some very early remains from Troy I and II (the first two layers), and some later Roman remains (Troy VIII and IX).

So what are you waiting for? Let’s have a look around the site!

Published on June 11, 2014 03:56

February 26, 2014

In Search of Cleopatra

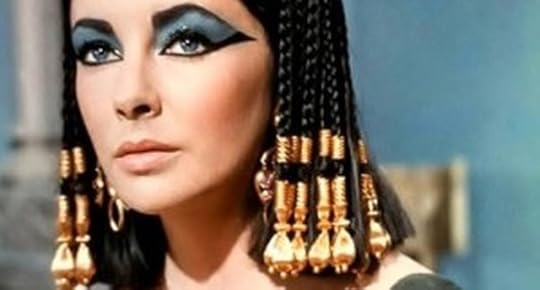

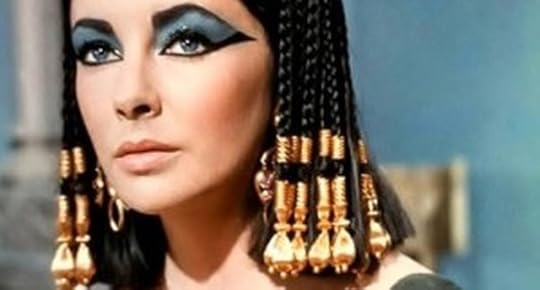

You can also read Emily's blog, "Missives from Iris", online at www.irisonline.org.uk/index.php/blog Cleopatra is something of an icon of our culture. How many people haven’t heard of Cleopatra’s famous suicide? Her infamous affair with Julius Caesar and Mark Anthony? Her kohl-rimmed eyes and irresistible sex appeal? But how much do you really know about Egypt’s last queen? Take the quiz below to find out – you might be surprised by what you learn! (Answers are at the bottom of the page)

1. How many children did Cleopatra have?

1. How many children did Cleopatra have?

A) None.

B) Two.

C) Four.

D) Six.

2. What was Cleopatra’s actual title?

A) Cleopatra VII Philopator

B) Cleopatra the Great

C) Cleopatra III Euergetis

D) Cleopatra I

3. How many languages did Cleopatra speak?

A) Only Egyptian.

B) Latin and Egyptian.

C) Seven different languages.

D) Fifteen different languages.

4. Who was Cleopatra’s first husband?

A) Julius Caesar.

B) Mark Anthony.

C) Alexander the Great.

D) Her brother.

5. Which of these images represents Cleopatra?

As you’ll notice, there’s actually quite a lot wrong in our understanding of Cleopatra. She wasn’t just a beauty or a femme fatale – she was highly political, with a fancy title to her name. She was smart, highly educated, and was the only one of her family to have learnt Egyptian, the language of the people she ruled (Cleopatra and her family were Greek by descent). She travelled widely when she was young, even going on a trip to Rome with her father, Ptolemy XII. At only eighteen years old, she married her own younger brother, Ptolemy XIII, to get to the throne. When things didn’t go too well for the newly married couple (rather unsurprisingly), Cleopatra coolly convinced the most famous Roman general, Julius Caesar, to side with her in a civil war against her brother by getting herself carried into Caesar’s rooms rolled up in a bit of sacking. The pair became lovers, and Cleopatra became pregnant with Caesar’s child, whom she later called Caesarion (“little Caesar”) after his father. It wasn’t, Plutarch tells us, that Cleopatra was that beautiful; but men just didn’t seem to be able to resist her. "For her beauty, as we are told, was in itself not altogether incomparable,” Plutarch says, “nor such as to strike those who saw her; but converse with her had an irresistible charm, and her presence, combined with the persuasiveness of her discourse and the character which was somehow diffused about her behaviour towards others, had something stimulating about it. There was sweetness also in the tones of her voice; and her tongue, like an instrument of many strings, she could readily turn to whatever language she pleased..."

When her great gamble fell through, however, and Caesar was murdered in the Roman Senate House on the Ides of March, Cleopatra took advantage of events yet again to ensure her safety and the safety of her country. Sailing across the Mediterranean in a luxury yacht, she met with one of the new rulers of the Roman Republic, Mark Anthony. Dressed up in the guise of the goddess of love, Cleopatra must have made quite an impression on the notoriously pleasure-loving Mark Anthony. But she obviously decided it wasn’t enough. So she invited him to a feast, determined to impress him with her wealth and glamour in a rather more unusual way. Calling for a glass of sour wine, she casually took off her earring – one of the largest pearls in the ancient world – and dropped it into the drink. The pearl dissolved, and Cleopatra drank it, showing Mark Anthony just how much wealth Egypt had to spare – they could even drink it! Mark Anthony was instantly smitten. The two fell in love, married, and had three children together: a pair of twins, Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene, and a son, Ptolemy Philadelphus. Only when Cleopatra’s second gamble fell through, and Octavian defeated Mark Anthony at the Battle of Actium, did the queen admit defeat. She committed suicide only moments after her husband: dramatic to the last, faithful to her husband and her country, a queen to the very end.

So does this sound like the Cleopatra you know? Most likely not. All the signs point to a Cleopatra who was, in fact, faithful to both the husbands she chose, a powerful and dedicated ruler who put the needs of her country before her own, and not even particularly beautiful – just very good company (to paraphrase Plutarch). So was Cleopatra a seductive siren or a good queen? Perhaps we’ll never know. But it seems, to me at least, that there’s rather more about Cleopatra than initially meets the eye. ANSWERS: 1. C 2. A 3. C 4. D 5. All have been identified with Cleopatra, but the only one that we know for sure represents her is the coin (B), as it bears her name. Can you find it? (Hint: it’s just above her head, to the left)

ANSWERS: 1. C 2. A 3. C 4. D 5. All have been identified with Cleopatra, but the only one that we know for sure represents her is the coin (B), as it bears her name. Can you find it? (Hint: it’s just above her head, to the left)

1. How many children did Cleopatra have?

1. How many children did Cleopatra have?A) None.

B) Two.

C) Four.

D) Six.

2. What was Cleopatra’s actual title?

A) Cleopatra VII Philopator

B) Cleopatra the Great

C) Cleopatra III Euergetis

D) Cleopatra I

3. How many languages did Cleopatra speak?

A) Only Egyptian.

B) Latin and Egyptian.

C) Seven different languages.

D) Fifteen different languages.

4. Who was Cleopatra’s first husband?

A) Julius Caesar.

B) Mark Anthony.

C) Alexander the Great.

D) Her brother.

5. Which of these images represents Cleopatra?

As you’ll notice, there’s actually quite a lot wrong in our understanding of Cleopatra. She wasn’t just a beauty or a femme fatale – she was highly political, with a fancy title to her name. She was smart, highly educated, and was the only one of her family to have learnt Egyptian, the language of the people she ruled (Cleopatra and her family were Greek by descent). She travelled widely when she was young, even going on a trip to Rome with her father, Ptolemy XII. At only eighteen years old, she married her own younger brother, Ptolemy XIII, to get to the throne. When things didn’t go too well for the newly married couple (rather unsurprisingly), Cleopatra coolly convinced the most famous Roman general, Julius Caesar, to side with her in a civil war against her brother by getting herself carried into Caesar’s rooms rolled up in a bit of sacking. The pair became lovers, and Cleopatra became pregnant with Caesar’s child, whom she later called Caesarion (“little Caesar”) after his father. It wasn’t, Plutarch tells us, that Cleopatra was that beautiful; but men just didn’t seem to be able to resist her. "For her beauty, as we are told, was in itself not altogether incomparable,” Plutarch says, “nor such as to strike those who saw her; but converse with her had an irresistible charm, and her presence, combined with the persuasiveness of her discourse and the character which was somehow diffused about her behaviour towards others, had something stimulating about it. There was sweetness also in the tones of her voice; and her tongue, like an instrument of many strings, she could readily turn to whatever language she pleased..."

When her great gamble fell through, however, and Caesar was murdered in the Roman Senate House on the Ides of March, Cleopatra took advantage of events yet again to ensure her safety and the safety of her country. Sailing across the Mediterranean in a luxury yacht, she met with one of the new rulers of the Roman Republic, Mark Anthony. Dressed up in the guise of the goddess of love, Cleopatra must have made quite an impression on the notoriously pleasure-loving Mark Anthony. But she obviously decided it wasn’t enough. So she invited him to a feast, determined to impress him with her wealth and glamour in a rather more unusual way. Calling for a glass of sour wine, she casually took off her earring – one of the largest pearls in the ancient world – and dropped it into the drink. The pearl dissolved, and Cleopatra drank it, showing Mark Anthony just how much wealth Egypt had to spare – they could even drink it! Mark Anthony was instantly smitten. The two fell in love, married, and had three children together: a pair of twins, Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene, and a son, Ptolemy Philadelphus. Only when Cleopatra’s second gamble fell through, and Octavian defeated Mark Anthony at the Battle of Actium, did the queen admit defeat. She committed suicide only moments after her husband: dramatic to the last, faithful to her husband and her country, a queen to the very end.

So does this sound like the Cleopatra you know? Most likely not. All the signs point to a Cleopatra who was, in fact, faithful to both the husbands she chose, a powerful and dedicated ruler who put the needs of her country before her own, and not even particularly beautiful – just very good company (to paraphrase Plutarch). So was Cleopatra a seductive siren or a good queen? Perhaps we’ll never know. But it seems, to me at least, that there’s rather more about Cleopatra than initially meets the eye.

ANSWERS: 1. C 2. A 3. C 4. D 5. All have been identified with Cleopatra, but the only one that we know for sure represents her is the coin (B), as it bears her name. Can you find it? (Hint: it’s just above her head, to the left)

ANSWERS: 1. C 2. A 3. C 4. D 5. All have been identified with Cleopatra, but the only one that we know for sure represents her is the coin (B), as it bears her name. Can you find it? (Hint: it’s just above her head, to the left)

Published on February 26, 2014 11:25

January 27, 2014

Who Knew? New Year

You can also read Emily's blog, "Missives from Iris", online at www.irisonline.org.uk/index.php/blog Happy New Year! As the days start to get longer again and we start to look forward to summer in the not-too-far-distant future, I wanted to take you back a bit for a look into the past. Because, while New Year might for you mean a lot of fireworks and even more resolutions (most of which have fallen by the wayside already), the celebration of the New Year actually goes all the way back to Roman times. (They didn’t have fireworks then, though, and I’m pretty sure the Romans were just as bad at keeping resolutions as we are.)

In fact, celebrating the New Year on January 1st has a bit of a bloody history to it. We’ve all heard of Julius Caesar, the famous first emperor of Rome who was murdered in the Senate for trying to become a tyrant. But what you might not have known is that Caesar, amongst his bloody campaigns and power-mongering, also engaged in a bit of home affairs. In fact, what Caesar decided Rome really needed was a new calendar. The trouble is that there aren’t exactly 365 days in a year, but 365 and a little bit. Now, before Julius Caesar, the Roman year lasted 355 days, and then, every now and then when they were running behind things a bit, the Romans would add in an extra month to make the time up. Not very convenient really, is it? Well, Caesar had a plan. Caesar’s idea was to divide the year into 365 days, rather than 355, and then simply add an extra day to the month of February every four years. That’s what gives us leap years today. And he also decided that it was much more sensible to celebrate the new year on the 1st January, rather than on March 1st, when the Romans used to celebrate the coming of spring. Much more logical, if you think about it.

In fact, celebrating the New Year on January 1st has a bit of a bloody history to it. We’ve all heard of Julius Caesar, the famous first emperor of Rome who was murdered in the Senate for trying to become a tyrant. But what you might not have known is that Caesar, amongst his bloody campaigns and power-mongering, also engaged in a bit of home affairs. In fact, what Caesar decided Rome really needed was a new calendar. The trouble is that there aren’t exactly 365 days in a year, but 365 and a little bit. Now, before Julius Caesar, the Roman year lasted 355 days, and then, every now and then when they were running behind things a bit, the Romans would add in an extra month to make the time up. Not very convenient really, is it? Well, Caesar had a plan. Caesar’s idea was to divide the year into 365 days, rather than 355, and then simply add an extra day to the month of February every four years. That’s what gives us leap years today. And he also decided that it was much more sensible to celebrate the new year on the 1st January, rather than on March 1st, when the Romans used to celebrate the coming of spring. Much more logical, if you think about it.

Julius Caesar’s calendar (today called the ‘Julian Calendar’) took effect in 45 BCE. But if you’ve done your homework, you know what happened next. Yes, that’s right: on the ides of March, 44 BCE, Julius Caesar was murdered (and, paradoxically, only a few weeks after the old New Year celebration. Good timing, Brutus). It was a difficult time for the newly formed empire, and having a new calendar in place can’t have made it easier. But when the senate voted to make Julius Caesar a god, they decided to do in on the first of January, as an official recognition of his achievement in making the new calendar, and the beginning of the new year.

So the celebration of the New Year on January 1st originally began with Julius Caesar turning into a god; and yet, the name of the month January actually comes from another Roman god – but not Julius Caesar (he got July). This is Janus, the two-headed god who guarded doorways and who could look both forwards and backwards – forwards, to the year to come; and backwards, to the year that had gone.

So the celebration of the New Year on January 1st originally began with Julius Caesar turning into a god; and yet, the name of the month January actually comes from another Roman god – but not Julius Caesar (he got July). This is Janus, the two-headed god who guarded doorways and who could look both forwards and backwards – forwards, to the year to come; and backwards, to the year that had gone.

What do you think – if Janus could have looked forwards to us now, in the future, would he still have recognised the New Year’s celebrations from his own days?

I like to think so.

In fact, celebrating the New Year on January 1st has a bit of a bloody history to it. We’ve all heard of Julius Caesar, the famous first emperor of Rome who was murdered in the Senate for trying to become a tyrant. But what you might not have known is that Caesar, amongst his bloody campaigns and power-mongering, also engaged in a bit of home affairs. In fact, what Caesar decided Rome really needed was a new calendar. The trouble is that there aren’t exactly 365 days in a year, but 365 and a little bit. Now, before Julius Caesar, the Roman year lasted 355 days, and then, every now and then when they were running behind things a bit, the Romans would add in an extra month to make the time up. Not very convenient really, is it? Well, Caesar had a plan. Caesar’s idea was to divide the year into 365 days, rather than 355, and then simply add an extra day to the month of February every four years. That’s what gives us leap years today. And he also decided that it was much more sensible to celebrate the new year on the 1st January, rather than on March 1st, when the Romans used to celebrate the coming of spring. Much more logical, if you think about it.

In fact, celebrating the New Year on January 1st has a bit of a bloody history to it. We’ve all heard of Julius Caesar, the famous first emperor of Rome who was murdered in the Senate for trying to become a tyrant. But what you might not have known is that Caesar, amongst his bloody campaigns and power-mongering, also engaged in a bit of home affairs. In fact, what Caesar decided Rome really needed was a new calendar. The trouble is that there aren’t exactly 365 days in a year, but 365 and a little bit. Now, before Julius Caesar, the Roman year lasted 355 days, and then, every now and then when they were running behind things a bit, the Romans would add in an extra month to make the time up. Not very convenient really, is it? Well, Caesar had a plan. Caesar’s idea was to divide the year into 365 days, rather than 355, and then simply add an extra day to the month of February every four years. That’s what gives us leap years today. And he also decided that it was much more sensible to celebrate the new year on the 1st January, rather than on March 1st, when the Romans used to celebrate the coming of spring. Much more logical, if you think about it.Julius Caesar’s calendar (today called the ‘Julian Calendar’) took effect in 45 BCE. But if you’ve done your homework, you know what happened next. Yes, that’s right: on the ides of March, 44 BCE, Julius Caesar was murdered (and, paradoxically, only a few weeks after the old New Year celebration. Good timing, Brutus). It was a difficult time for the newly formed empire, and having a new calendar in place can’t have made it easier. But when the senate voted to make Julius Caesar a god, they decided to do in on the first of January, as an official recognition of his achievement in making the new calendar, and the beginning of the new year.

So the celebration of the New Year on January 1st originally began with Julius Caesar turning into a god; and yet, the name of the month January actually comes from another Roman god – but not Julius Caesar (he got July). This is Janus, the two-headed god who guarded doorways and who could look both forwards and backwards – forwards, to the year to come; and backwards, to the year that had gone.

So the celebration of the New Year on January 1st originally began with Julius Caesar turning into a god; and yet, the name of the month January actually comes from another Roman god – but not Julius Caesar (he got July). This is Janus, the two-headed god who guarded doorways and who could look both forwards and backwards – forwards, to the year to come; and backwards, to the year that had gone. What do you think – if Janus could have looked forwards to us now, in the future, would he still have recognised the New Year’s celebrations from his own days?

I like to think so.

Published on January 27, 2014 04:49

January 8, 2014

Pompeii: A Guided Walking Tour (Part III)

You can also read Emily's blog, "Missives from Iris", online at www.irisonline.org.uk/index.php/blog

Thank you for all your responses! I hope you enjoy visiting your favourite sites in the continuation of the walking tour below…

It’s 75 CE. You’re a merchant from Rome who has come to buy some fish sauce in Pompeii. Rufus, a merchant from Pompeii, has just finished giving you a tour of the city and has left you by yourself at the Herculaneum Gate. You’re trying to work out how to get back to the harbour before the sun sets. Below is a map of your route so you can follow where you are.

You look around you. With Rufus gone, you’ve got absolutely no idea how to get back to the harbour, and you’re starting to worry that, if you’re not there in time, your ship might leave without you. You turn around and hurriedly shove a few denarii into the hand of the nearest fish sauce seller, grab a basket full of pots of the stinking sauce, and make your way towards the gate.

You look around you. With Rufus gone, you’ve got absolutely no idea how to get back to the harbour, and you’re starting to worry that, if you’re not there in time, your ship might leave without you. You turn around and hurriedly shove a few denarii into the hand of the nearest fish sauce seller, grab a basket full of pots of the stinking sauce, and make your way towards the gate.

I came into the city through one of the gates in the city walls, you reason with yourself, trying not to drop the basket of fish sauce as a crowd of noisy party-goers push past you. So, if I follow the city walls, that should take me back to where I started – eventually.

You try to ignore the creeping feeling in your stomach as you imagine what will happen if the ship leaves for Rome without you.

Scrambling a bit on the stone steps, you make your way up the rampart beside the Herculaneum Gate and onto the city walls. You hoped you’d have a good view from here, but the walls on the rampart are high enough that you can’t make out anything except a partial view over the sprawling city, full of high tenement blocks that blot out the darkening sky. You look right and left, then, not knowing which way to go, you toss one of your last denarii. The head of the Emperor Vespasian. Left, then.

You set off along the walls, trying to keep your basket level. Occasionally, you pass a massive fortified gate set in the walls, and you check to see if you can make out the river Sarno and the harbour; but there are only dry, dusty roads leading away from these gates, to the shadowy hulking mass of Mount Vesuvius to your left, its flanks lit gold in the sunset. It’s starting to get a bit colder, and you hunch your shoulders around your ears. This can’t be right. You’ve been walking for a good half hour, and still, no sign of the harbour.

When you reach the fourth gate, you decide that you must have gone the wrong way. You can see the main road that you and Rufus walked down only a few hours ago, stretching out below you like a yellow ribbon; and, slightly to the left of the road, a tavern, its oil lamps burning brightly and invitingly.

Without thinking about it, you scramble your way down the slope beside the gate and make your way towards the tavern. At least you can ask someone there for directions; and you wouldn’t say no to a good honey cake, either.

As you push open the door, the sound of chatter and laughter reaches your ears, and the delicious smell of roasting meat. You pass the bar, with its jars full to the brim of sweet red wine, and a few tables where men are sitting and playing dice. At one end of the room, serving a couple of men who look like they could be gladiators, you spot a woman with curled red hair who is carrying a tray with goblets of watered wine.

“Excuse me,” you say, approaching her cautiously. She turns around.

“Are you looking for a room?” she says, putting one hand on her hip. “Or just a meal?”

“Oh, no, I’m not here to buy,” you say quickly, hitching your basket up higher. “I’m afraid I’ve lost my way. I need to get back to the harbour.”

She smiles at you. “Not often we get someone here at Julia Felix’s who doesn’t want to buy,” she says, setting down her tray and taking you by the arm, leading you over to the door. “This is the most popular tavern in town. You’re lucky you stumbled on us and not somewhere else.”

She points across the street, to a bar packed with half-drunk men, some of them in the midst of a brawl.

“Anyway,” she says, and she leans out of the door and shades her eyes against the setting sun, “you’ll want to follow the main road that way,” she points down the road, away from the walls, “all the way through the city. Don’t turn at any of the crossroads, and don’t get distracted when you hit the forum.” She gleams a smile at you. “Just keep straight on. That should take you to the gate to the harbour alright.”

You thank her and give her another denarius for a honey cake before you take your leave. After a few blocks of houses, you suddenly recognise where you are. This is the very crossroads you passed with Rufus! There, on the right, are the baths, and on the left behind that high wall must be the house of Lucius Popidius Secundus! You start to quicken your footsteps. Any moment now you’ll be in the Forum, and then it’s only a matter of time until…

As the road starts to slope down towards the harbour, you almost whoop with joy. You’ve just spotted the Porta Marina. You hurry down the slight hill and through the gate, the traffic much less busy now than it was when you arrived. You give a sigh of relief. Your ship is there, floating on the water, just where it was a few hours ago. You hurry towards it, waving at the captain and pointing at your basket.

“Did you have to wait for me?” you ask breathlessly, heaving your basket on board and preparing to climb onto the ship, too.

The captain squints down at you. “We’ve got an hour left till we leave,” he says, staring at your sweaty face and dust-covered hands. “I hope you didn’t hurry here.”

You rub your forehead irritably. An hour left! All that rushing for nothing! Your stomach gives a loud grumble, and you think ruefully that you could have stopped in Julia Felix’s tavern for a whole meal.

The irritation must show on your face, because the captain smiles.

“Don’t worry,” he says. “There’s a perfect place to relax before we go. Over there,” and he points towards a large porticoed building, built right on the harbour edge. “The Suburban Baths. You’ve got time for a quick dip to wash off all that sweat and dust before we head for Rome.”

You thank him and make your way over towards the building. The entrance is quiet and dark, and you step immediately into the changing room. The walls are covered in paintings of couples in lewd positions. You smile as you place your clothes in a locker beneath a couple who seem to be particularly enjoying themselves. What an innovative way to make sure you remember where you put your clothes, you think to yourself.

After a tour through the baths, which involves a plunge into a cold pool, a sweating session in the boiling hot caldarium and a massage and a scrape-down in the tepidarium, you feel much more kindly towards Pompeii than you did an hour or so ago. You retrieve your clothes without any problems, and make your way back to the ship. The sun is just about to set as you climb aboard and stow your basket of fish sauce carefully in the hold.

“So,” the captain asks as one of the ship’s boys draws up the anchor and he hoists the sail, ready to leave, “how did you like Pompeii?”

You smile as you watch the lights of Pompeii, reflected in the water of the Sarno river, drifting into the distance.

“It’s not the biggest city you’ll ever see,” I say, quoting Rufus with a smile, “but then, I think I agree with my friend – it makes up in liveliness what it lacks in size.”

And, with that, you turn around towards the prow of the ship and look out to sea.

Thank you for all your responses! I hope you enjoy visiting your favourite sites in the continuation of the walking tour below…

It’s 75 CE. You’re a merchant from Rome who has come to buy some fish sauce in Pompeii. Rufus, a merchant from Pompeii, has just finished giving you a tour of the city and has left you by yourself at the Herculaneum Gate. You’re trying to work out how to get back to the harbour before the sun sets. Below is a map of your route so you can follow where you are.

You look around you. With Rufus gone, you’ve got absolutely no idea how to get back to the harbour, and you’re starting to worry that, if you’re not there in time, your ship might leave without you. You turn around and hurriedly shove a few denarii into the hand of the nearest fish sauce seller, grab a basket full of pots of the stinking sauce, and make your way towards the gate.

You look around you. With Rufus gone, you’ve got absolutely no idea how to get back to the harbour, and you’re starting to worry that, if you’re not there in time, your ship might leave without you. You turn around and hurriedly shove a few denarii into the hand of the nearest fish sauce seller, grab a basket full of pots of the stinking sauce, and make your way towards the gate.I came into the city through one of the gates in the city walls, you reason with yourself, trying not to drop the basket of fish sauce as a crowd of noisy party-goers push past you. So, if I follow the city walls, that should take me back to where I started – eventually.

You try to ignore the creeping feeling in your stomach as you imagine what will happen if the ship leaves for Rome without you.

Scrambling a bit on the stone steps, you make your way up the rampart beside the Herculaneum Gate and onto the city walls. You hoped you’d have a good view from here, but the walls on the rampart are high enough that you can’t make out anything except a partial view over the sprawling city, full of high tenement blocks that blot out the darkening sky. You look right and left, then, not knowing which way to go, you toss one of your last denarii. The head of the Emperor Vespasian. Left, then.

You set off along the walls, trying to keep your basket level. Occasionally, you pass a massive fortified gate set in the walls, and you check to see if you can make out the river Sarno and the harbour; but there are only dry, dusty roads leading away from these gates, to the shadowy hulking mass of Mount Vesuvius to your left, its flanks lit gold in the sunset. It’s starting to get a bit colder, and you hunch your shoulders around your ears. This can’t be right. You’ve been walking for a good half hour, and still, no sign of the harbour.

When you reach the fourth gate, you decide that you must have gone the wrong way. You can see the main road that you and Rufus walked down only a few hours ago, stretching out below you like a yellow ribbon; and, slightly to the left of the road, a tavern, its oil lamps burning brightly and invitingly.

Without thinking about it, you scramble your way down the slope beside the gate and make your way towards the tavern. At least you can ask someone there for directions; and you wouldn’t say no to a good honey cake, either.

As you push open the door, the sound of chatter and laughter reaches your ears, and the delicious smell of roasting meat. You pass the bar, with its jars full to the brim of sweet red wine, and a few tables where men are sitting and playing dice. At one end of the room, serving a couple of men who look like they could be gladiators, you spot a woman with curled red hair who is carrying a tray with goblets of watered wine.

“Excuse me,” you say, approaching her cautiously. She turns around.

“Are you looking for a room?” she says, putting one hand on her hip. “Or just a meal?”

“Oh, no, I’m not here to buy,” you say quickly, hitching your basket up higher. “I’m afraid I’ve lost my way. I need to get back to the harbour.”

She smiles at you. “Not often we get someone here at Julia Felix’s who doesn’t want to buy,” she says, setting down her tray and taking you by the arm, leading you over to the door. “This is the most popular tavern in town. You’re lucky you stumbled on us and not somewhere else.”

She points across the street, to a bar packed with half-drunk men, some of them in the midst of a brawl.

“Anyway,” she says, and she leans out of the door and shades her eyes against the setting sun, “you’ll want to follow the main road that way,” she points down the road, away from the walls, “all the way through the city. Don’t turn at any of the crossroads, and don’t get distracted when you hit the forum.” She gleams a smile at you. “Just keep straight on. That should take you to the gate to the harbour alright.”

You thank her and give her another denarius for a honey cake before you take your leave. After a few blocks of houses, you suddenly recognise where you are. This is the very crossroads you passed with Rufus! There, on the right, are the baths, and on the left behind that high wall must be the house of Lucius Popidius Secundus! You start to quicken your footsteps. Any moment now you’ll be in the Forum, and then it’s only a matter of time until…

As the road starts to slope down towards the harbour, you almost whoop with joy. You’ve just spotted the Porta Marina. You hurry down the slight hill and through the gate, the traffic much less busy now than it was when you arrived. You give a sigh of relief. Your ship is there, floating on the water, just where it was a few hours ago. You hurry towards it, waving at the captain and pointing at your basket.

“Did you have to wait for me?” you ask breathlessly, heaving your basket on board and preparing to climb onto the ship, too.

The captain squints down at you. “We’ve got an hour left till we leave,” he says, staring at your sweaty face and dust-covered hands. “I hope you didn’t hurry here.”

You rub your forehead irritably. An hour left! All that rushing for nothing! Your stomach gives a loud grumble, and you think ruefully that you could have stopped in Julia Felix’s tavern for a whole meal.

The irritation must show on your face, because the captain smiles.

“Don’t worry,” he says. “There’s a perfect place to relax before we go. Over there,” and he points towards a large porticoed building, built right on the harbour edge. “The Suburban Baths. You’ve got time for a quick dip to wash off all that sweat and dust before we head for Rome.”

You thank him and make your way over towards the building. The entrance is quiet and dark, and you step immediately into the changing room. The walls are covered in paintings of couples in lewd positions. You smile as you place your clothes in a locker beneath a couple who seem to be particularly enjoying themselves. What an innovative way to make sure you remember where you put your clothes, you think to yourself.

After a tour through the baths, which involves a plunge into a cold pool, a sweating session in the boiling hot caldarium and a massage and a scrape-down in the tepidarium, you feel much more kindly towards Pompeii than you did an hour or so ago. You retrieve your clothes without any problems, and make your way back to the ship. The sun is just about to set as you climb aboard and stow your basket of fish sauce carefully in the hold.

“So,” the captain asks as one of the ship’s boys draws up the anchor and he hoists the sail, ready to leave, “how did you like Pompeii?”

You smile as you watch the lights of Pompeii, reflected in the water of the Sarno river, drifting into the distance.

“It’s not the biggest city you’ll ever see,” I say, quoting Rufus with a smile, “but then, I think I agree with my friend – it makes up in liveliness what it lacks in size.”

And, with that, you turn around towards the prow of the ship and look out to sea.

Published on January 08, 2014 05:13

October 25, 2013

Pompeii: A Guided Walking Tour (Part II)

You can also read Emily's blog, "Missives from Iris", online at www.irisonline.org.uk/index.php/blog Take this survey online now to vote which monuments in Pompeii YOU want to visit on next week's tour! The two most popular sites will be included in next week’s guided tour through Pompeii!

It’s 75 CE. You’re a merchant from Rome who has come to buy some fish sauce in Pompeii. Rufus, a merchant from Pompeii, is giving you a tour of the city. Below is a map of your route so you can follow where you are. You have just arrived in front of a large aristocratic house, which Rufus has told you belongs to one of Pompeii’s most important aristocrats: Lucius Popidius Secundus.

It’s 75 CE. You’re a merchant from Rome who has come to buy some fish sauce in Pompeii. Rufus, a merchant from Pompeii, is giving you a tour of the city. Below is a map of your route so you can follow where you are. You have just arrived in front of a large aristocratic house, which Rufus has told you belongs to one of Pompeii’s most important aristocrats: Lucius Popidius Secundus.

You look at the huge bronze doors, and feel a shiver run down your spine, even though the day is hot.

You look at the huge bronze doors, and feel a shiver run down your spine, even though the day is hot.

“Who lives there?”

Rufus gives a snort. “Lucius Popidius Secundus,” he says derisively, though he lowers his voice to a whisper and looks around him all the same. He gives you a knowing look. “There are plenty of stories I could tell you about him, my friend.

“He’s from one of the oldest families in Pompeii. Look,” Rufus says more loudly, and he points to an election notice painted up on the front wall in red. “Fabius and Sula ask that you elect Gaius Cuspius Pansa and Lucius Popidius Secundus as aediles,” he reads aloud, tracing it with his finger. “That’s Lucius Popidius all over,” he says, lowering his voice back to its conspiratorial tone. “Says he’s Pompeii’s man through and through, but really, he’s just in it for the power.”

You don’t really understand what Rufus means, so you peer through the large bronze doors instead which are standing slightly ajar, and catch sight of a long corridor leading into a large hall with a fountain playing at the centre. Behind it, you can just glimpse a couple of beautiful colonnaded gardens filled with statues and – in one – even a swimming pool.

“It’s very grand,” you admit. “Some of the senators in Rome would give a lot for a house like this.”

Rufus looks pleased and leads you on. A few streets down you stop again and stare in delight.

“But this is just like Rome!” you exclaim. You are staring at a large amphitheatre, with arched walls towering up overhead. It sounds like the gladiators are training: you can hear the sounds of swords clashing against shields, the whoosh of nets and tridents and the shouts of the trainer, urging the gladiators on. You turn excitedly to Rufus. “The Emperor Vespasian is building one in the very centre of Rome, it will be the largest amphitheatre the world has ever seen.” Rufus looks a little hurt, so you add quickly, “But of course, this one’s very big too.” And it’s true. As you quickly scan the structure, you guess that it will hold around 20,000 people – not a bad audience to watch the gladiatorial games.

“The only one in Campania that’s larger is at Capua,” Rufus boasts, his smile coming back. Then he looks up at the sky and the sun, which is sinking west behind the mountain. “It’s getting late,” he says. “We should probably make our way over to the Herculaneum Gate if you want to get your fish sauce in time before the shops close.”

You nod, and you make your way back up another long street. You twist your head right and left to see everything – the bustling bars doling out wine from large jars set in the counters; the bakeries, where donkeys wearily walk round and round to grind the grain and ash-smeared bakers hurry in and out to deliver their customers’ loaves; you even spot a couple of single rooms in the basements of some of the shops where heavily-painted women are leading men in behind a curtain, giggling.

“Is Pompeii always this busy?” you ask, walking nimbly across the stepping stones as you cross a road.

Rufus smirks. “Always,” he says, turning a corner and making his way onto a curved road – one of the only ones you’ve been on that wasn’t on the grid system, you realise. You think that this must be the oldest part of the town, built before the grid system came in from Greece. “Here you are.”

He stops short. To the right of you is an odd, triangular-shaped block of houses – squeezed in, you realise, between the old curved street and the new straight ones. It’s filled with factories, all of them with tanks sunk in the ground full to the brim with water. You bring your hand immediately to your nose.

“Ugh – it stinks!”

Rufus laughs. “Fish sauce tastes better than it smells,” he admits. “But Pompeii’s Herculaneum Gate has the best in town. You won’t do better than here.” You turn your head to the left and see, at the end of the street, another large gate leading out of the city, and a milestone labelled “Herculaneum: 10 miles.” It must be another town around the Bay, you think. “Well, this is where I leave you.”

“Well, this is where I leave you.”

You realise that Rufus is talking to you, and turn back to look at him. He’s grinning at you and has his hand held out again.

“Good luck with your sauce,” he says jovially, “and give my regards to your father.”

“I will, I will,” you say, shaking his hand again. “Thank you for the tour.”

He waves your thanks away as if he’s swatting a particularly large fly. “It’s nothing. You’ll be able to find your way back again?” he asks.

You gaze back down the crooked street, past the crowds of bustling merchants and the endless bars and houses that all look the same.

“I — well —”

You look back at Rufus, about to ask him for directions to the harbour. But he’s already gone, disappeared into the crowds of Pompeiians swarming down the street.

You sigh. You suppose you’ll have to find your way back by yourself.

How will you get back to the harbour? YOU decide! Take this survey online now to vote which monuments in Pompeii YOU want to visit on your way back to the harbour! The two most popular sites will be included in next week’s walking tour. Check back for more adventures in Pompeii!

It’s 75 CE. You’re a merchant from Rome who has come to buy some fish sauce in Pompeii. Rufus, a merchant from Pompeii, is giving you a tour of the city. Below is a map of your route so you can follow where you are. You have just arrived in front of a large aristocratic house, which Rufus has told you belongs to one of Pompeii’s most important aristocrats: Lucius Popidius Secundus.

It’s 75 CE. You’re a merchant from Rome who has come to buy some fish sauce in Pompeii. Rufus, a merchant from Pompeii, is giving you a tour of the city. Below is a map of your route so you can follow where you are. You have just arrived in front of a large aristocratic house, which Rufus has told you belongs to one of Pompeii’s most important aristocrats: Lucius Popidius Secundus.  You look at the huge bronze doors, and feel a shiver run down your spine, even though the day is hot.

You look at the huge bronze doors, and feel a shiver run down your spine, even though the day is hot.“Who lives there?”

Rufus gives a snort. “Lucius Popidius Secundus,” he says derisively, though he lowers his voice to a whisper and looks around him all the same. He gives you a knowing look. “There are plenty of stories I could tell you about him, my friend.

“He’s from one of the oldest families in Pompeii. Look,” Rufus says more loudly, and he points to an election notice painted up on the front wall in red. “Fabius and Sula ask that you elect Gaius Cuspius Pansa and Lucius Popidius Secundus as aediles,” he reads aloud, tracing it with his finger. “That’s Lucius Popidius all over,” he says, lowering his voice back to its conspiratorial tone. “Says he’s Pompeii’s man through and through, but really, he’s just in it for the power.”

You don’t really understand what Rufus means, so you peer through the large bronze doors instead which are standing slightly ajar, and catch sight of a long corridor leading into a large hall with a fountain playing at the centre. Behind it, you can just glimpse a couple of beautiful colonnaded gardens filled with statues and – in one – even a swimming pool.

“It’s very grand,” you admit. “Some of the senators in Rome would give a lot for a house like this.”

Rufus looks pleased and leads you on. A few streets down you stop again and stare in delight.

“But this is just like Rome!” you exclaim. You are staring at a large amphitheatre, with arched walls towering up overhead. It sounds like the gladiators are training: you can hear the sounds of swords clashing against shields, the whoosh of nets and tridents and the shouts of the trainer, urging the gladiators on. You turn excitedly to Rufus. “The Emperor Vespasian is building one in the very centre of Rome, it will be the largest amphitheatre the world has ever seen.” Rufus looks a little hurt, so you add quickly, “But of course, this one’s very big too.” And it’s true. As you quickly scan the structure, you guess that it will hold around 20,000 people – not a bad audience to watch the gladiatorial games.

“The only one in Campania that’s larger is at Capua,” Rufus boasts, his smile coming back. Then he looks up at the sky and the sun, which is sinking west behind the mountain. “It’s getting late,” he says. “We should probably make our way over to the Herculaneum Gate if you want to get your fish sauce in time before the shops close.”

You nod, and you make your way back up another long street. You twist your head right and left to see everything – the bustling bars doling out wine from large jars set in the counters; the bakeries, where donkeys wearily walk round and round to grind the grain and ash-smeared bakers hurry in and out to deliver their customers’ loaves; you even spot a couple of single rooms in the basements of some of the shops where heavily-painted women are leading men in behind a curtain, giggling.

“Is Pompeii always this busy?” you ask, walking nimbly across the stepping stones as you cross a road.

Rufus smirks. “Always,” he says, turning a corner and making his way onto a curved road – one of the only ones you’ve been on that wasn’t on the grid system, you realise. You think that this must be the oldest part of the town, built before the grid system came in from Greece. “Here you are.”

He stops short. To the right of you is an odd, triangular-shaped block of houses – squeezed in, you realise, between the old curved street and the new straight ones. It’s filled with factories, all of them with tanks sunk in the ground full to the brim with water. You bring your hand immediately to your nose.

“Ugh – it stinks!”

Rufus laughs. “Fish sauce tastes better than it smells,” he admits. “But Pompeii’s Herculaneum Gate has the best in town. You won’t do better than here.” You turn your head to the left and see, at the end of the street, another large gate leading out of the city, and a milestone labelled “Herculaneum: 10 miles.” It must be another town around the Bay, you think.

“Well, this is where I leave you.”

“Well, this is where I leave you.”You realise that Rufus is talking to you, and turn back to look at him. He’s grinning at you and has his hand held out again.

“Good luck with your sauce,” he says jovially, “and give my regards to your father.”

“I will, I will,” you say, shaking his hand again. “Thank you for the tour.”

He waves your thanks away as if he’s swatting a particularly large fly. “It’s nothing. You’ll be able to find your way back again?” he asks.

You gaze back down the crooked street, past the crowds of bustling merchants and the endless bars and houses that all look the same.

“I — well —”

You look back at Rufus, about to ask him for directions to the harbour. But he’s already gone, disappeared into the crowds of Pompeiians swarming down the street.

You sigh. You suppose you’ll have to find your way back by yourself.

How will you get back to the harbour? YOU decide! Take this survey online now to vote which monuments in Pompeii YOU want to visit on your way back to the harbour! The two most popular sites will be included in next week’s walking tour. Check back for more adventures in Pompeii!

Published on October 25, 2013 09:21