Caitlin E. Jones's Blog, page 3

November 20, 2017

Banning Books and Virtuous Outrage: A Defense of Reading Widely

A fissure has formed in the book community as of late, and over a topic we don’t often assign to the average bookworm: censorship. Reviewers have grown more passionate about defending diverse books and criticizing common racial/LGBT pitfalls that less diverse authors fall into. This was a great, purposeful movement,… until it became a weapon.

Popular reviewers and bloggers began leading hunts after writers and books they deemed ‘problematic’, full of 1-star reviews and call-out blogs. Readers were told not to buy, or read, or even speak positively of books the community found troubling or questionable. This ‘problematic’ label now ranges from actual poor representation to lead characters who simply don’t align with upstanding morals/beliefs- it’s even been directed at book before they’ve released in ARC. This aslso came a very anti-classic novel movement, aiming to snub the patriarchal roots of fiction found in the likes of Hemingway and Updike.

The lines have been drawn, and many people have come out with criticism over the movement. Likewise, there are authors, agents, and reviewers that defend the movement’s core idea is being upheld.

The image that comes to mind for community censorship is not usually a group of awkward bookish teens, but the conservative Midwestern housewife, storming into her son’s school after she’s discovered the many uses of N-word in To Kill a Mockingbird, or all the course language and scary content of Bridge to Terabithia. This happens every year, after all. It’s a culture of church pamphlets that scare parents away from Harry Potter and Golden Compass, or whispered fear of why someone won’t read Kurt Vonnegut.

Community censorship isn’t new, but do we actually serve progressive writing and diverse works with it? Are works of the past, or difficult topics, now impossible to broach in this ‘more sensitive’ era?

Doubtful. If the aforementioned books can survive controversy, then so will many of the recent troublemakers. If a book stirs something in the world, chances are it’s worth reading- if only to see why it stirred up said reaction. If the combatants of problematic books meant to taper down interest, it failed with novels like Carve The Mark, The Black Witch, and All The Crooked Saints, all of which sold brilliantly. And that’s not to say these books are immune to criticism; indeed, we should discuss the ideas behind a bigoted character taking a lead role, or a white author writing outside of their race or culture. We should discuss the pitfalls and merits to these kinds of books, but the key word is “discuss”: not “banish.”

If we’re truly being supportive of diversity, we have to learn to critique without bashing. We also have to read older works with an understanding of what is historical, and therefore may not age well by our standards. Most of all, we need to remember that authors are just people (albeit weird people) who do not usually mean to attack in their portrayals or narratives. I suspect internet culture buries this etiquette in the face of personal opinion and virtue signaling, but I still find it exists.

Fostering this mindset is so important these days, simply because one of the biggest issues in censorship is that people simply refuse to read widely enough. Like the man who never leaves his small American hometown, limited reading makes a limited reader. Yes, there’s a lack of proper representation in popular fiction, a selection of books that makes up about 0.11111111% of what books you can buy. There are scores of incredible indie and less well promoted books, written by authors from all walks of life, about characters and stories from all over the world. These books not only deserve your reviews, but the market will continue to have a hard time changing untilpeople make an effort to positively support these kinds of books and buy them. Be the change you wish to see realized.

The same goes for your experience with classic fiction. You can’t just disregard the eras past fully, where Oscar Wilde and Virginia Woolf, notable LGBT authors, reside. Or how about Jane Austen, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, and Christina Rossetti, incredibly feminist voices of their day? Shakespeare himself explored complex themes with race, homosexuality, and gender roles in an era we often don’t associate with progressive anything.

Are these old works flawless in their pursuits? No, and many of them are marked with their era’s views, and the same will happen with the works of the 21st century. In Shakespeare’s time, readers found Chaucer unreadable, troubled, and dated. A hundred years from now, groups of scholars will study our scores of YA books and chat box novels, and students will scoff that these works: “how dated! How problematic! Why would they even think this way?”

There are few paths to a perfect, truly “unproblematic” book- and why would we want our characters perfect and unbiased anyway? Humanity is flawed, people are messy and sometimes wrong. When we have characters that are the same way, it allows an audience to reflect on that wrongness through the lens of fiction. Old books also allow us a glimpse a past and an understanding of it, so that we might do better. That should be the purpose of the hard, controversial, and downright upsetting.

If we are never challenged, then we never truly reflect. And I suppose that’s a good question to ask one’s self: if a book or character stirs anger in my soul- if I feel the need to hide away from it, what exactly am I hiding from? What truth do we see, looking back at us from those pages?

Published on November 20, 2017 00:00

November 6, 2017

Behind The Curtain, Between Lines: On Critical Reading

“Reading is easy. I just don’t have time.” I hear this at least once or twice during my year, often more now that I’m in college, where fellow students are assigned multiple novels during a semester. They will probably skirt by through SparkNotes, skim their books, and follow the movie versions for an easier, two-hour viewing.

“Reading is easy,” yet many of us would rather do anything but settle in to read something in-depth for a few hours. Reading consumes time and takes effort- save for maybe the lightest fair that makes up your local grocery store’s books, abound with James Patterson and Nora Roberts. For something that’s gained the reputation of being easy, we sure treat reading like a Herculean task in our day. In many ways, people speak of reading the exact same way the speak of writing: “anyone can do it, but I’d rather not.”

So perhaps we should reframe what reading is, or better yet, the different kinds of reading we engage in. Because we often ignore the value of critically reading- and I don’t just refer to the critical reading we do in school. I refer to the critical dissection of work that goes beyond reading for fun.

I think this makes more sense from the author’s perspective. There is a space you reach, at some point when you write, where it becomes harder to just “read for fun.” Not that you won’t ever read for fun again, but the enjoyment you garner from stories will come from different places. Your favorites’ list will start to become a narrower, cleanly trimmed path of books that you revisit a lot and fill with sticky notes. You begin to admire the sweep of a sentence and the structure of a story arc, rather than the garnish and straight plot that makes up a usual read. Like any good magician, you suddenly understand how the tricks are put together; you see the mirrors and extra cards. It’s only worse if you have a strong inner editor.

When I first experienced this, I was a little heartbroken. There were suddenly so many books I was critical of, and I feared it made me hate them. I would never siphon true enjoyment from reading if all I could think to do was pick apart sentences and story arcs… It took me some time- not until I first considered an English major in college, that I changed my mind.

Flashback to spring of 2015, in my small English 102 class, where we spent a lot of time interpreting contemporary poetry. We had one novel to write about for the class, Robert Cormier’s YA terrorist thriller, After The First Death… I hated this book. I still really hate this book, and the way it’s written, and how horrible its one-dimensional characters are to each other. I wasn’t entirely sure how I was going to write about it, since I spent ¾’s of my read picking it apart. When the professor approached me about my essay ideas, I made it clear, “I don’t particularly like this book. In fact,” I said. “I’d have enjoyed it better if I spent more time on the relationships and characters. There’s so much to be desired there.”

“I agree. So, write about it,” my professor offered. “Interpret it through that perspective.”

Two lengthy, handwritten drafts later, not only did I write an entire essay on the critical issues surrounding After The First Death, I had completely reshaped one of the final scenes and accredited two characters’ tension to Stockholm and Lima Syndrome, with scientific evidence to back up the claim. It led to two of the best grades I ever got on essays. From my critical read, I had gained something else Cormier’s book that I might not have gleaned otherwise. Yes, I saw what Cormier did, but also why it worked for other readers, and how to interpret it differently.

This was for a class, but I try to maintain this style of reading now, whether studying Shakespeare or cracking open the latest novel by Marissa Meyer. I try to cobble together deeper meaning from the fiction I read, and love when books can meet me with that level of depth. I love when I can peel back the layers of a story, and surprise myself with what the author created.

Reading this way isn’t always easy, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t enjoyable. There is magic to be found in between passages, after all.

Published on November 06, 2017 18:11

November 1, 2017

October 11, 2017

That Which Authors Fear Most: At Odds With Writing Doubts

While at an author talk on fairytales and the writing process at my university, a question came from the audience about writing challenges, sensitively, and how to overcome both. The author smiled warily and paused before answering (and this is not quite verbatim), “You know, I struggled a lot with finding a voice in the process, and tuning out critics who didn’t care for this kind of storytelling. I can’t quite tell you how to move past those fears or be less sensitive, because chances are- if you’re drawn to writing, you are a little more sensitive anyway, and you’ve learned to embrace that as part of what you do. It’s okay.”

The statement struck me with all sorts of memories, the first of these being the descriptor from my previous job managing an authors’ community: “must have good bedside manner: authors are sensitive creatures and known for their moodiness.” In the most negative connotation, this can sound like chiding for melodramatic behavior. But then, I had to admit, all authors have a flare for melodrama, don’t they? It’s not our fault, really- it is part of the makeup of creating something. The double-edged sword of art is the confidence to build out of thin air, and the crippling fear that you have created it wrong.

I’ve written longer than I had means to form words on paper, and used storytelling as a harbor to deal with a sometimes difficult childhood. Writing helped translate many of my personal anxieties into something more tangible, making them less scary. Ironic that writing can become, in its own way, a new form of stress and worry. We begin to fret and fuss over our own skills, how our audience views us, and if we live up to the very expectations we place upon ourselves.

I’m no exception to the rule. I am the most and least happy when I want to write; the writing itself is a joyful process. Editing and revision less so, and boy, do I ever hate working on middles. I can become so wrapped up in the process of not writing and the guilt I feel when not writing, that I work myself up into a sad frenzy. “That’s it- I’ll never write again. Been a nice ride, but clearly, I have used all the talent. I am a fake, a fraud…”

And that’’s never true, is it? We always end up back on the grind- pen to paper, fingers to keys. We find our way back into the land of make-believe eventually. A failure in creating is when we give up, after all, not when we make something less than desirable.

During my time as a community manager, I heard a lot of stories from authors. So many emails and comments about emotion turmoil, mental illness, or just good ol’ self-doubt. About coping, drinking, and all the bad and good habits we’ve accrued in hopes of finding a short route to art. But on the business front, I was often asked why “x author here” was acting this way. Why are artists so damned quick to sadness, or anger? Why do they need all this… encouragement?

And I couldn’t help but wonder, just for myself, how much better it was knowing I wasn’t alone. How comforting was it knowing that other writers struggled with the same worries, doubts, and fears.

There is a part of the world that disregards ‘sensitive’ folk as tenderhearted, as something flawed. We discount these nervous behaviors as odd, but what if they are as much part of the writing as the writer themselves? What if it is that very anxiety that drives us to do better?

Not to say you should cripple yourself with worry and doubt, but rather it’s important to recognize that those doubts and worries don’t make you a bad writer, and they certainly don’t make you a bad person. Caring about what you create means far more than to have never cared at all. There is bravery in continuing in spite of writing woes.

So, go ahead: write the scene that scares you most, press forward in miserable revisions, send out query letters even if you fear rejection.

Find someone whose shoulder you can cry on, find a writing tribe who gets that you aren’t out of your mind for despairing over your imaginary friends.

Make yourself a fresh cup of tea or pot of coffee- spike it with something strong, if needed, and keep going. Courage, dear heart.

Published on October 11, 2017 15:11

September 27, 2017

On Women, Horror, and The Art of Otherness

There is a story, from when I was five or six, about the first time I saw a Stephen King series. I believe it was Storm of The Century, where a small town in Maine is blocked off by a huge snowstorm and subsequently terrorized by what turns out to be a demon. Suicides occur, children are taken to become evil protégé, all while the villain continuously sings “I’m a Little Teapot.”

There is a story, from when I was five or six, about the first time I saw a Stephen King series. I believe it was Storm of The Century, where a small town in Maine is blocked off by a huge snowstorm and subsequently terrorized by what turns out to be a demon. Suicides occur, children are taken to become evil protégé, all while the villain continuously sings “I’m a Little Teapot.”I remember this vividly, you might notice- because it scared the hell out of me. As did The Tower of Terror, that skeleton army scene in The Black Cauldron, the entire Fantasia sequence of “Night on Bald Mountain.” The one time I watched sections of The Wall when my parents didn’t see me come in (a bad idea, in hindsight). I suffered from one fired-up imagination and had a habit of taking frightening imagery, allowing my brain to fill in the story’s blanks. This resulted in a lot of sleeplessness and nightmares.

“They’re only stories,” my father told me once. “Like Little Red Riding Hood and The Big Bad Wolf. Remember, that wolf always loses.”

Something in those words settled into my soul, and I revisit them sometimes. While I scared very easily as a child, I grew to like and write gothic fiction overtime- a lot of writers do that. A close cousin to historical and horror, and a little like neither. More in common with cabaret music and steampunk culture these days too. Tim Burton was always fun, and I loved the ghost stories book that my mother had passed along to me- the kind with The Monkey’s Paw and ghostly women that haunted roadside hotel. When I was eleven, I sunk my teeth into Edger Allen Poe’s The Black Cat and Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events. The wolves were there, and they came in the form of human condition, negligence, and impossible odds. There is complexity and nuance to each monster, and I saw hope and cleverness there. I found that through fear- something these stories often used, there was also glints of compassion and heroics. I fell in love. I dove into the genre and all it had to offer.

As a reader, a writer, and I suppose, as a person, I’ve always related heavily to that one Doctor Who quote from the Weeping Angels episode with Sally Sparrow. “I love old things. They make me feel sad. It’s happy for deep people.” While a bit on the “emo teenager” side of statements, I’ve far more in common with old ghosts and antique books than I really should. There is an otherness there that I understand.

There is a rather interesting phenomenon in horror and gothic fiction that taps into Otherness. These stories exist in several ways: the heroes verses The Other (Dracula, The Phantom of The Opera), the village verses The Other (The Masque of The Red Death), and The Other verses himself (The Picture of Dorian Gray, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and one could argue Frankenstein). Scholars like Jarlath Killeen have discussed the connotations of this in early gothic fiction, and their often racially or culturally charged supernatural entities. There is a mirror effect that occurs in these stories as well, a self-reflection not only of the author themselves, but of the cultural state they occupy, particularly in female authors. Female horror authors love Otherness.

Mary Shelley reflects her times with subjects of responsibility and parentage, and with a monster so brilliant and devastating powerful- yet so physically abhorrent. Shirley Jackson, who died too young to see how her books have lasted, loved the subject of dysfunctional family and tragedy. Anne Rice’s vampires are as depraved as they are empathetic. And this does not go without critique, films like The Woman in Black, Corpse Bride, and Crimson Peak, more feminine in focus and nuanced in their villains, were dragged for being “too sad” and “not scary enough.”

This comes in clear contrast to Stoker, or Wilde, or much of King; monsters are enemies to be defeated. Otherness is something separate from the hero, or even something that consumes the hero to his demise (see Dorian). There is no space for nuance- we’re back to Little Red Riding Hood and The Big Bad Wolf. Wolves always lose.

But what if your wolves are not so literal? What if our enemies are not the ghosts we face, but the beasts that created them? Or what’s more- what if your wolves are too literal? Women spend most of their lives facing what the Big Bad Wolf represents, making this threat more reality than fiction. Perhaps women understand their monsters better, or see them differently.

One of the most striking statements I’ve encountered about gothic horror is that men write monsters based on their enemy (take “enemy” to mean whatever you like sociologically); women write monsters based on how they view themselves. They aren’t just fighting the monster, they are the monster. Society certainly seems to think so, given its track record with women: witch trials, poor mental health, suppression, claims of hysteria… Is it any wonder we feel for the Other?

I write my own sad ghosts and empathetic monsters now, not near as scared of horror movies these days. If anything, I’ve come to understand them a bit better. Rather than fearing the wolves, society sometimes acts as though women might just become one of them. And maybe they’re right.

Published on September 27, 2017 20:40

August 24, 2017

The Undergrad Novelist: On the Sophomore Slump and How I Beat It

Published on August 24, 2017 12:50

August 14, 2017

The Power of Laughter: On Satire and Parody in Fiction

There is a quote from Mel Brooks that I’ve always adored: “If you want to take power away from something, laugh at it.” A stunning statement coming from a Jewish-raised man who served in World War II, and his humor often reflected that background. Many of his movies portray Hilter and The Third Reich as comical, foppish, and foolish. There is an entire musical in The Producers dedicated to mocking Nazis, which goes on to be a smash hit with the audience in movie (much to the chagrin of the main characters). “Springtime for Hitler” doesn’t ignore the darkness inside World War II (“Winter for Poland and France”, so the lyrics go), but undercuts real evil with a heaping of ridiculousness.

Brooks has made it his life’s mission to make light, whether it be pop culture, overused tropes, and more touchy subjects like racism and war. His movies have shown that he’s not the only one who enjoys the laugh, given their importance in American cinema and comedy. Not all parody need be like the Scary Movie franchises; the art of parody goes well beyond Brooks, reaching into novels, plays, and every weekly sketch show in existence.

And then, well beyond the absurd: Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey was written as a satire of late 18th century Gothic fiction, many of Shakespeare’s plays poked fun at romance tropes and popular characters from his era’s England. But surely, says the general public, we aren’t supposed to make fun of Austen and Shakespeare. They were serious writers and respectable in the world of literature. How dare someone write a modern text version of Romeo and Juliet, or Pride & Prejudice with zombies!

And I will tell you, general public, that you should probably read a few of those Shakespeare plays one more time. You’ve overlooked all the raunchy jokes and clever cultural references. And after all, who said humor can’t be literary? Who ever said that comedy can’t be part of intelligence? It’s easy to throw satire into the ring of low brow, but being funny requires a little more than a good punchline.

I grew up with Monty Python’s Flying Circus reruns, a series more well-attuned to British humor than American. And while it has its share of silliness, their comedy always came with a wink and a tongue firmly placed in cheek. The movie Monty Python & The Holy Grail is a brilliant example of this, an Arthurian legend parody on its surface with a ton of political and historical comedy peppered along the way. While there are plenty of quotable parts from the film, my favorite scene is still the witch trial.

Not only is this still really funny and well-paced, this joke actually has historical context! Tried witches in Europe used to be tossed in ponds and rivers to see if they floated- which is dark and absurd to consider now. There are layers of humor here, from the silly and down into something more cultural and well-researched. The movie just takes life’s true absurdity a step further, revealing it for its ridiculousness and paranoia.

And maybe that’s the core of satire and parody: a means to honesty through the abstract and comical. The world we inhabit is harsh sometimes, just as it is strange and nonsensical.

We use comedy as a reflection from which the world feels a little lighter. Political climates can feel smothering, people grossly negative, and the daily grind crushing. Is it any wonder people turn to The Daily Show or Saturday Night Live at the end of the day? We want comedy to undercut the world’s seriousness. Sometimes, we need to laugh, to take the power back.

Published on August 14, 2017 13:08

July 19, 2017

Creatives and Criminals: The Dark Side of The Writer

Going through all of Stephen King’s works sounds like a beastly task, but it’s also an insightful one. King is the modern master of horror for a reason, tapping into every ghost, ghoul, and inner fear his audience would rather hide. Some of his most telling work though, is about the persona behind the pen. The Shining, Misery, and the novella, Secret Window, Secret Garden, all deal with authorly protagonists. Jack Torrance, an troubled aspiring author and alcoholic whose personal demons, hotel ghosts, and artistic failures all drive him to kill. And Paul Sheldon, a mild-mannered, famous author who finds himself held captive by his biggest fan, forced to revive a popular series he has decided to end.

Misery is the sort of book every writer’s group makes jokes about as an “author’s worst nightmare.” Annie Wilkes is the monster that destroys manuscripts, fuels co-dependency, and chops off fingers (don’t lie- you know you flinched). But King tapped into something far more terrifying with Mort Rainey.

In Secret Garden, Secret Window (better known for Secret Window, a 2004 film adaptation with Johnny Depp as the lead), Mort Rainey comes into conflict with John Shooter, an unstable stranger that has plagiarized his latest story- all but its ending anyway.

Several arson cases and violent deaths later, Mort realizes (and spoilers here, so be warned) that there was never any John Shooter at all. Mort is John Shooter, a character so powerful that he has become part of Mort’s personality. While the movie and novella end on different notes (somewhat creepy when you consider the plot), the message retains its prowess. Sometimes our monsters aren’t disturbed fans or old spirits; sometimes the author is the monster.

This has a rocky history of playing itself out in real life. Creative folk get a rep for being weird at best, and deviant or disturbed at worst. They are statistically more inclined to depression and anxiety, drawn heavily to drugs and drinking (all of King’s authors had problems with drug abuse and/or alcoholism, notably), and usually do not fit in to what we might call “normal.” What we seek and do is very lonely at times, and this lifestyle is not a path most desire to tread.

I have a vivid memory of the first time I got in a fight with a professor: after a classmate’s sobering presentation on young musicians, mental illness, and suicide, she dared to call me out and ask why “all artists are depressed freaks? That means you’re a freak too, right?”

I shot up in my seat at once. “Yes, and I’m proud of that.”

I’ve reflected on this incident since, wondering about this “depressed freak” stereotype and how much truth exists in its shadow. Writers are only people, after all; we have the potential to be bullies to reviewers, terrors to our family, and destructive forces on ourselves. There are writers from the past, whose choices reflect racial and social beliefs that shock a modern audience. Several people have even made a career of writing about their crimes, turning horrors into art. They are social outcasts like Wilde, or dark cultish personalities like Hubbard. King himself has a notorious reputation from taking out his rage on the man who accidentally hit him with a car. He was destroyed as a character in King’s fiction, and legally ruined in real life. His reputation didn’t recover before his early death.

Authors aren’t always good people, probably because they are people in the first place. No matter how idealized and golden their created worlds may be. Does that mean a story get take on the judgement that we cast on the author? Depends on the reader, I suppose, but I would much rather let a story stand outside of an author’s shadow- as much as it possibly can anyway.

We are imposing strange creatures at times, but we all write to express a certain secret honesty out into the world. Whether that truth gives away of our inner darkness away really comes down to the author, and whether the reader wants to know said author quite so intimately.

Interestingly enough, the statistical number of fiction authors who are real-life killers is quite low compared to King’s characters. Studies have shown though that psychopathy and a lack of empathy isn’t commonly connected with artistic traits. Indeed, most serial killer authors tend to write more about themselves than anyone else.

It begs the question though- why writers choose to portray other fictional writers as monsters? What kind of “freak” do we see when we create, and are we scared of it too?

Published on July 19, 2017 00:28

May 25, 2017

Writer’s Block and You: On Causes and How to Write On

If I were going to rank writing-related questions from least to greatest, “how do I beat writer’s block?” probably falls quite high on the list, if not at number one. When I worked as a small publisher’s community manager, this question would show up at least twice a week- on forums, discussion posts, and Q&As with other published authors.

The responses were varied and usually stale in quality: the same “take a walk, listen to fresh music, write something else”- and that’s not to say that these things can’t stop Writer’s Block, because they can for some people. But it’s often occurred to me that, for a question that gets asked so much, there are very few solid answers as to how you actually stop Writer’s Block. There is nothing more frustrating when you are applying all of the fixes and they just don’t work. Que the spiral of despair as you stare down that ever-blinking cursor.

But if Writer’s Block is an ailment, we shouldn’t be searching for the cure; we should find the cause. The same logic applies if you spike a fever; cause might say you have cold, but WebMD will convince you that you’re probably dying of gangrene.

So, let’s talk about a few distinct types of Writer’s Block and what they do to the writing process.*

*(to me, personally. Full disclaimer here, because the most important thing to understand about Writer’s Block is how, just like writing habits, its causes are very unique to the author.)

Starting-Point Stage Fright:

Usually right before or at the beginning of every novel. Symptoms include procrastination, excessive research, and lots of deleted opening paragraphs.

There’s a really great quote by Gene Wolfe, which goes, “You never learn how to write a novel … you only learn to write the novel you’re on.” This was said to Neil Gaiman (yeah, that Gaiman), who finally felt he had this novel thing down after writing American Gods.

I’m now three novels into my writing career, with two more on my plate for this year. Each one of them starts with the sensation of groping around a pitch-black room with only my rough outline and a half functional flashlight. There are things in this room that I want (and probably better batteries for my flashlight), but I need to get my bearings first. It usually takes me about 15,000 words to do this, and it’s easy to mistake this sensation for a “lack of inspiration.” I encourage you to bury the concept of inspiration somewhere deep for now. Inspiration isn’t magical fully-fleshed out concepts; inspiration is what we do when we find those fresh batteries and get a clearer picture of our space. “Press forward to those 15,000,” I remind myself. It always pays off and I always manage to find those batteries eventually, even if it takes a few tries.

The Middle of Despair:

Named so for its location, as the middle of books are notorious for being mind-numbingly hard to write. Symptoms will include plotting ending scenes you have not yet written, social media browsing, and crippling self-doubt. Welcome to the void of the writing process. You got this.

Not everyone has problems writing their novel’s middle, but it’s often noted as a rough part of first drafts and rewrites. We tend to come into stories with a general idea of the plot’s cause and effect: the beginning and middle, in more novel-related terms. It’s easy to get caught up in the sogginess of a middle and fall into a great deal of mood swing-y sadness. Writing must not be for you if you can’t even get through a simple section of the book.

But journeys aren’t about the destination, yes? And as Jeff VanderMeer says, when the reader enjoys an ending, they’re really saying they enjoyed the payoff to the well-structured middle of a novel. This quote helped me re-frame what middles were; the meat and potatoes of the story. Substance that keeps your reader around for the finale, rather than a sequence of events so you can get to the ending. Whenever I find myself trapped in the middle, I have to ask myself “how does this benefit the ending?” If it doesn’t, I cut and rework (even in a first draft, which something I would normally warn against). Listening to your gut about what isn’t working, and locating the strength in your middle, is usually one of the easiest ways to avoid its slog.

Revisionary Roadblocks:

Symptoms include starting new projects despite a lack of time, inelegant sobbing, and the return of that crippling self-doubt.

You might think, once you have finished your first draft, you would be free of the Writer’s Block and its troubling patterns. Revision and rewriting should be easy now that you’ve finished the book, right?

Ah, the innocence.

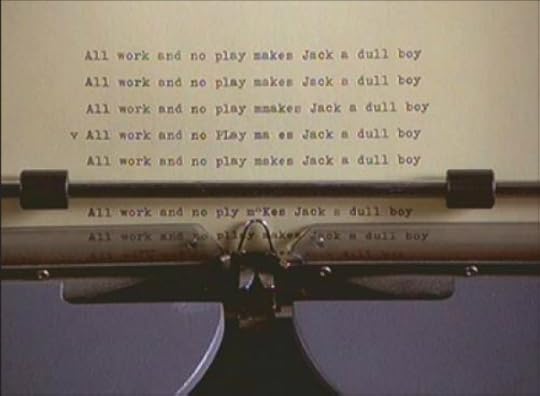

Some of the worst roadblocks I have encountered in writing show up in the process of fixing the first draft; the scenes to reframe, plotlines to tighten, characters to build upon. Revision is harder than hell, since so many issues can show up during revisions that you don’t expect. The point of editing books is digging deeper; you must unearth the layers beneath the top soil that is your first draft, and you will find things you don’t like, things you must throw away and rework into oblivion. There will be scenes that you adore and no longer apply to your current vision. Your story will never again be the project you started, and it will never be perfect, and you get to accept that in all its artistic ugliness.

I recently finished my editing on my first novel and am currently working on edits for the second. The act of pushing through your revision roadblocks- whatever they may be, is a matter of willpower, and moreover, about confidence. It requires trusting in your own abilities, recognizing your limits, and practicing over and over. It’s about being open to failure and critique, and learning from both for the future. These are all hard to stomach, and probably the reason most people don’t like editing. But revision separates the novice from the novelist, and humbling yourself to it is the best way forward. After all, we are often much stronger writers than we feel.

What’s your experience with Writer’s Block? Where do you get it during the writing process and how have you learned to address it?

Published on May 25, 2017 22:09

May 2, 2017

A ShoreIndie Featured Author of 2017!

Just a super quick update (because graduation and finals- yikes) to let everyone know that this summer, I will be representing the #ShoreIndie Contest as a Featured Author! I will be on Twitter between June 12-July 30 (a pinned-down date to come) to discuss writing, my blogs, and my experience with everyone, so have your questions ready and feel free to share to interested folk! The contest they are running is fantastic and very supportive of the indie community- so if you are interested, you can read more about them here! Please also check out the other featured authors; I am honored to be up there with so many talented writers!

Just a super quick update (because graduation and finals- yikes) to let everyone know that this summer, I will be representing the #ShoreIndie Contest as a Featured Author! I will be on Twitter between June 12-July 30 (a pinned-down date to come) to discuss writing, my blogs, and my experience with everyone, so have your questions ready and feel free to share to interested folk! The contest they are running is fantastic and very supportive of the indie community- so if you are interested, you can read more about them here! Please also check out the other featured authors; I am honored to be up there with so many talented writers!Stay tuned for more during the summer!

Published on May 02, 2017 12:31