Arleen Williams's Blog, page 9

May 11, 2018

Exciting News!

In April 2008, my first book was published. On this 10thanniversary, I am very pleased to announce the re-release of The Thirty-Ninth Victim .

The Green River murders were headline news throughout the 1980s. By the time the perpetrator was finally arrested over twenty years later, at least 48 young women had been killed in the worst serial murder case in history.

In THE THIRTY-NINTH VICTIM, Arleen Williams tells the story of her family's journey before and after the Green River killer murdered her youngest sister and offers a window into the family dynamics behind this life-altering tragedy. The redemptive power of finding and facing truth are at the heart of this powerful memoir.

As you may know, writing this memoir reshaped the course of my life. Publication gave me voice and launched an unplanned and much cherished writing career. The book sparked memorable conversations with readers and earned numerous positive reviews.

A courageous and insightful memoir that stands as a tribute to a beloved sister and that opens a revealing window on family dynamics in the face of an unspeakable crime. Arleen Williams's account is measured, thorough, factual, and heartbreaking. —Priscilla Long, author of Fire and Stone: Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?

You can find The Thirty-Ninth Victim here. If you have read the first edition, perhaps you might want to gift a copy to friend or family. This 10thanniversary edition sports a new epilogue as well as a sharp new cover by designer, Loretta Matson.

As always, thank you for your interest and readership (and for your Amazon reviews).

As always, thank you for your interest and readership (and for your Amazon reviews).

Published on May 11, 2018 11:42

April 20, 2018

Thank you!

Shortly after I finished Biking Uphill, I had lunch with friends who were concerned about illegal immigration. I found myself wanting to say, "But I know someone who's been through this and she…" Then I realized I was thinking about Antonia and that her story had touched me so deeply I almost forgot it was fiction. This is the power of Arleen Williams' writing. She's a born story-teller.Susan Knox, author of Financial Basics: A Money-Management Guide for Students

Sometimes a good review is just what the “writing doctor” ordered. I remember first reading the above review. Tears filled my eyes. I felt like a writer, like I’d touched a reader’s heart, like I’d accomplished something important. Readers’ reviews can do that for a writer, for this writer. They can encourage and vindicate. Many thanks to all of you who take the time to post your thoughts.

Sometimes a good review is just what the “writing doctor” ordered. I remember first reading the above review. Tears filled my eyes. I felt like a writer, like I’d touched a reader’s heart, like I’d accomplished something important. Readers’ reviews can do that for a writer, for this writer. They can encourage and vindicate. Many thanks to all of you who take the time to post your thoughts.Biking Uphill is on sale this weekend for only $0.99. If you haven’t read it, now is a great time to download your copy. Just click here!

Published on April 20, 2018 07:57

April 13, 2018

This Weekend Only ...

I sit at my writing desk and gaze at the bleeding hearts in the garden outside my window. Is spring in your part of the world as unpredictable as it is in mine? Do you need a new book on you Kindle to fill the indoors hours?

I sit at my writing desk and gaze at the bleeding hearts in the garden outside my window. Is spring in your part of the world as unpredictable as it is in mine? Do you need a new book on you Kindle to fill the indoors hours?Running Secrets is a great rainy day read. Haven't read it yet? Now's the time! On sale this weekend for only $0.99, you might want to load it on your Kindle. Just click here.

Chris is bent on self-destruction until Gemi, an Ethiopian home healthcare provider, and Jake, a paramedic, enter her life. They help Chris confront her difficult past and regain a passion for living. In the process, Chris and Gemi forge an unconventional friendship that bridges cultural, racial and age differences. Their friendship spurs Gemi to question restrictive traditions dictating her immigrant life, and Chris to probe family secrets. Together the women learn that racial identity is a choice, self-expression is a right, and family is a personal construct.

The interconnecting portraits of The Alki Trilogy give voice to the plight of the newest immigrants to the Pacific Northwest. The Alki Trilogy also includes Biking Uphill and Walking Home.

Published on April 13, 2018 08:40

April 6, 2018

What Bulawayo Taught Me

I pride myself in understanding the immigrant and refugee experience, in knowing the challenges of mastering the English language and adapting to life in the United States. I’ve spent over three decades honing my skills as an ESL instructor. Yet, I was recently brought to my knees by the work of NoViolet Bulawayo, convinced that I am a professional fraud, ignorant of the depths of despair faced by countless immigrants in our country.

Shortly after Trump’s inexcusable comment on January 11, 2018 about countries around the globe, using a word that would land a schoolchild in detention, I came across an article at the online magazine Electric Lit titled 11 Incredible Books by Writers from ‘Shithole’ Countries.

After printing the article, I logged into my Seattle Public Library account and put holds on every book on the list except one, Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, which I’d already devoured.

In the last few months, I’ve read most of the books on the list. Novels, memoirs, and poetry collections that sang with passion and fury. Books that made me laugh and cry, that made me think and re-evaluate what I thought I knew.

NoViolet Bulawayo’s novel forced me to examine the depth of my understanding of the students who sit in my ESL classroom each day, of the immigrants we see on our streets in cities and small towns across America. There is so much in this novel it is hard to choose what to share. Four scenes, or perhaps themes, took my breath away: one dealing with language learning, another with food consumption, a third with legality, and finally one about home and the responsibility of immigrants to their home country and the loved ones left behind.

I am a language instructor at a large, urban community college. Each quarter I face students from a dozen or more different nations. I view this as a learning opportunity not only for them, but also for me – even after thirty years at the college. And yet, I was stunned by Bulawayo’s descriptions of the challenges of learning the English language.

In this scene, Darling’s aunt is on the phone trying to order a bra from Victoria Secret. The conversation does not go well. When it ends, Bulawayo describes her aunt’s behavior in this way:

I know that she will turn on the lights as she descends the creaking stairway, that she will take small measured steps like there is something down there that she dreads, that when she gets to the bottom, she will stand in front of the mirror that covers one wall and look at her reflection. I know that she won’t be looking at her thinness but at her mouth. I know that she will stand there and start the conversation all over and say out loud, in careful English, all the things that she meant to say, that she should have said to the girl on the phone but did not because she could not find the words at the time. I know that in front of that mirror, Aunt Fostalina will articulate, that the English will come alive on her tongue and she will spit it like it’s burning her mouth, like it’s poison, like it’s the only language she has ever known. (p. 200)

And here, I had to put the book aside, to think, breathe, remember the many, many, many times I have reminded my students to speak in English. Even during break time.

Because we were not in our country, we could not use our own languages, and so when we spoke our voices came out bruised. When we talked, our tongues thrashed madly in our mouths, staggered like drunken men. Because we were not using our languages we said things we did not mean; what we really wanted to say remained folded inside, trapped. In America we did not always have the words. It was only when we were by ourselves that we spoke in our real voices. When we were alone we summoned the horses of our languages and mounted their backs and galloped past skyscrapers. Always, we were reluctant to come back down. (p. 242)

Health is often a theme in my classes each quarter. Over the years, I have witnessed seemingly healthy and svelte new arrivals put on weight, often excessive weight, after a period of time in the United States. I have attributed this unfortunate situation to dietary changes and the consumption of too much cheap, fast food. Bulawayo shows me another interpretation:

…At McDonald’s we devoured Big Macs and wolfed down fries and guzzled supersized Cokes. At Burger King we worshipped Whoppers. At KFC we mauled bucket chicken. We went to Chinese buffets and ate all we could inhale—fried rice, chicken, beef, shrimp, and as for the things whose names we could not read, we simply pointed and said, We want that.

We ate like pigs, like wolves, like dignitaries; we ate like vultures, like stray dogs, like monsters; we ate like kings. We ate for all our past hunger, for our parents and brothers and sisters and relatives and friends who were still back there. We uttered their names between mouthfuls, conjured up their hungry faces and chapped lips—eating for those who could not be with us to eat for themselves. And when we were full we carried our dense bodies with the dignity of elephants—of only our country could see us in America, see us eat like kings in a land that was not ours. (p. 241)

Legal status is a devastating concern plaguing far too many immigrants in our country. Every quarter is see the strain, I feel the pain. Every quarter students mysteriously disappear. Sometimes I’ll get a whisper: ICE. Most times I do not. Here is Bulawayo’s description of what it means to be undocumented in America:

When they debated what to do with illegals, we stopped breathing, stopped laughing, stopped everything, and listened. We heard: exporting America, broken borders, war on the middle class, invasion, deportation, illegals, illegals, illegals. We bit our tongues till we tasted blood, sat tensely on one butt check, afraid to sit on both because how can you sit properly when you don’t know about your tomorrow?

And because we were illegal and afraid to be discovered we mostly kept to ourselves, stuck to our kind and shied away from those who were not like us. We did not know what they would think of us, what they would do about us. We did not want their wrath, we did not want their curiosity, we did not want any attention. We did not meet stares and we avoided gazes. We hid our real names, gave false ones when asked. We built mountains between us and them, we dug rivers, we planted thorns—we had paid so much to be in America and we did not want to lose it all. (p. 244)

Another theme We Need New Names addresses is the weight of responsibility immigrants carry toward those they left behind and the homeland they love, as well as the anger and expectations of those left behind. The endless stream of money sent by Western Union, the packages of food and clothing are never enough. Here, Darling is skyping from the U.S. with a childhood friend in Zimbabawe:

Just tell me one thing. What are you doing not in your country right now? Why did you run off to America, Darling Nonkululeko Nkala, huh? Why did you just leave? If it’s your country, you have to love it to live in it and not leave it. You have to fight for it no matter what, to make it right. Tell me, do you abandon your house because it’s burning, do you expect the flames to turn into water and put themselves out? You left it, Darling, my dear, you left the house burning and you have the guts to tell me, in that stupid accent that you were not even born with, that doesn’t even suit you, that this is your country?

My head is buzzing. I throw the computer, and when I realize what I’ve done, it is sailing toward the wall. I gasp as it connects to the mask, cover my ears when they both crash to the floor. I don’t look to check the damage, I just get out of my room like the air has been sucked. (p. 288-289)

My head is also buzzing with the endless insults and gutter talk of the man we call president of this nation of immigrants. The world is small and getting smaller. The deeper our understanding and appreciation of the diversity of those who inhabit it, the better we are able to cherish our shared home. The brilliant works of international authors help us do just that.

Shortly after Trump’s inexcusable comment on January 11, 2018 about countries around the globe, using a word that would land a schoolchild in detention, I came across an article at the online magazine Electric Lit titled 11 Incredible Books by Writers from ‘Shithole’ Countries.

After printing the article, I logged into my Seattle Public Library account and put holds on every book on the list except one, Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, which I’d already devoured.

In the last few months, I’ve read most of the books on the list. Novels, memoirs, and poetry collections that sang with passion and fury. Books that made me laugh and cry, that made me think and re-evaluate what I thought I knew.

NoViolet Bulawayo’s novel forced me to examine the depth of my understanding of the students who sit in my ESL classroom each day, of the immigrants we see on our streets in cities and small towns across America. There is so much in this novel it is hard to choose what to share. Four scenes, or perhaps themes, took my breath away: one dealing with language learning, another with food consumption, a third with legality, and finally one about home and the responsibility of immigrants to their home country and the loved ones left behind.

I am a language instructor at a large, urban community college. Each quarter I face students from a dozen or more different nations. I view this as a learning opportunity not only for them, but also for me – even after thirty years at the college. And yet, I was stunned by Bulawayo’s descriptions of the challenges of learning the English language.

In this scene, Darling’s aunt is on the phone trying to order a bra from Victoria Secret. The conversation does not go well. When it ends, Bulawayo describes her aunt’s behavior in this way:

I know that she will turn on the lights as she descends the creaking stairway, that she will take small measured steps like there is something down there that she dreads, that when she gets to the bottom, she will stand in front of the mirror that covers one wall and look at her reflection. I know that she won’t be looking at her thinness but at her mouth. I know that she will stand there and start the conversation all over and say out loud, in careful English, all the things that she meant to say, that she should have said to the girl on the phone but did not because she could not find the words at the time. I know that in front of that mirror, Aunt Fostalina will articulate, that the English will come alive on her tongue and she will spit it like it’s burning her mouth, like it’s poison, like it’s the only language she has ever known. (p. 200)

And here, I had to put the book aside, to think, breathe, remember the many, many, many times I have reminded my students to speak in English. Even during break time.

Because we were not in our country, we could not use our own languages, and so when we spoke our voices came out bruised. When we talked, our tongues thrashed madly in our mouths, staggered like drunken men. Because we were not using our languages we said things we did not mean; what we really wanted to say remained folded inside, trapped. In America we did not always have the words. It was only when we were by ourselves that we spoke in our real voices. When we were alone we summoned the horses of our languages and mounted their backs and galloped past skyscrapers. Always, we were reluctant to come back down. (p. 242)

Health is often a theme in my classes each quarter. Over the years, I have witnessed seemingly healthy and svelte new arrivals put on weight, often excessive weight, after a period of time in the United States. I have attributed this unfortunate situation to dietary changes and the consumption of too much cheap, fast food. Bulawayo shows me another interpretation:

…At McDonald’s we devoured Big Macs and wolfed down fries and guzzled supersized Cokes. At Burger King we worshipped Whoppers. At KFC we mauled bucket chicken. We went to Chinese buffets and ate all we could inhale—fried rice, chicken, beef, shrimp, and as for the things whose names we could not read, we simply pointed and said, We want that.

We ate like pigs, like wolves, like dignitaries; we ate like vultures, like stray dogs, like monsters; we ate like kings. We ate for all our past hunger, for our parents and brothers and sisters and relatives and friends who were still back there. We uttered their names between mouthfuls, conjured up their hungry faces and chapped lips—eating for those who could not be with us to eat for themselves. And when we were full we carried our dense bodies with the dignity of elephants—of only our country could see us in America, see us eat like kings in a land that was not ours. (p. 241)

Legal status is a devastating concern plaguing far too many immigrants in our country. Every quarter is see the strain, I feel the pain. Every quarter students mysteriously disappear. Sometimes I’ll get a whisper: ICE. Most times I do not. Here is Bulawayo’s description of what it means to be undocumented in America:

When they debated what to do with illegals, we stopped breathing, stopped laughing, stopped everything, and listened. We heard: exporting America, broken borders, war on the middle class, invasion, deportation, illegals, illegals, illegals. We bit our tongues till we tasted blood, sat tensely on one butt check, afraid to sit on both because how can you sit properly when you don’t know about your tomorrow?

And because we were illegal and afraid to be discovered we mostly kept to ourselves, stuck to our kind and shied away from those who were not like us. We did not know what they would think of us, what they would do about us. We did not want their wrath, we did not want their curiosity, we did not want any attention. We did not meet stares and we avoided gazes. We hid our real names, gave false ones when asked. We built mountains between us and them, we dug rivers, we planted thorns—we had paid so much to be in America and we did not want to lose it all. (p. 244)

Another theme We Need New Names addresses is the weight of responsibility immigrants carry toward those they left behind and the homeland they love, as well as the anger and expectations of those left behind. The endless stream of money sent by Western Union, the packages of food and clothing are never enough. Here, Darling is skyping from the U.S. with a childhood friend in Zimbabawe:

Just tell me one thing. What are you doing not in your country right now? Why did you run off to America, Darling Nonkululeko Nkala, huh? Why did you just leave? If it’s your country, you have to love it to live in it and not leave it. You have to fight for it no matter what, to make it right. Tell me, do you abandon your house because it’s burning, do you expect the flames to turn into water and put themselves out? You left it, Darling, my dear, you left the house burning and you have the guts to tell me, in that stupid accent that you were not even born with, that doesn’t even suit you, that this is your country?

My head is buzzing. I throw the computer, and when I realize what I’ve done, it is sailing toward the wall. I gasp as it connects to the mask, cover my ears when they both crash to the floor. I don’t look to check the damage, I just get out of my room like the air has been sucked. (p. 288-289)

My head is also buzzing with the endless insults and gutter talk of the man we call president of this nation of immigrants. The world is small and getting smaller. The deeper our understanding and appreciation of the diversity of those who inhabit it, the better we are able to cherish our shared home. The brilliant works of international authors help us do just that.

Published on April 06, 2018 11:26

March 29, 2018

Truth is …

I skipped February completely, and here it is the end of March. What happened to those weekly, bi-weekly, even monthly posts? Have I nothing more to say? Have I run out of words? Has laziness gotten the better of me?

Maybe…

Maybe I have nothing to say in these turbulent times. Maybe I’ve run out of words to voice my frustrations. Maybe I’ve allowed laziness or apathy to take hold.

Truth is …

I took a break. Truth is sometimes life gets in the way of intentions and self-imposed deadlines. Truth is teaching and writing, revising and editing have gotten the better of me these last few months.

More to come soon. I promise.Happy Spring!

Maybe…

Maybe I have nothing to say in these turbulent times. Maybe I’ve run out of words to voice my frustrations. Maybe I’ve allowed laziness or apathy to take hold.

Truth is …

I took a break. Truth is sometimes life gets in the way of intentions and self-imposed deadlines. Truth is teaching and writing, revising and editing have gotten the better of me these last few months.

More to come soon. I promise.Happy Spring!

Published on March 29, 2018 15:47

January 12, 2018

Rediscovering My Local Library

When my daughter was young, we spent long hours in our local library paging the picture books, collecting tall piles to carry home, our library visit a weekly highlight throughout her earliest years.

Primary school brought a change, a limitation to the long leisurely library days, but we still borrowed books on a regular basis. Later, as my daughter began swim team and dance classes, I branched out from my local library and sought the nearest location available while I waited. I wrote much of The Thirty-Ninth Victim in public libraries in Burien, Queen Anne and Green Lake.

I live in an area privileged with two superb library systems: Seattle Public Library and King County Library. Still, I lost my library habit as my daughter became a teenager. When renovations closed my neighborhood branch for a year and a half, I began shopping used bookstores and buying titles on Amazon to support writer/friends. I bought rather than borrowed until our bookshelves overflowed.

Recently an NPR review of a new title intrigued my husband, but he didn’t want to pay full price for a hefty hardcover. He also didn't want to bring more books into the house until the two large bags in the trunk of the car have been donated. So, we took a walk to our local library.

It’s a beautiful red brick building with antique light fixtures and heavy wood furniture. The library website states: "The library, which opened in 1910, is a Carnegie-funded branch designed by W. Marbury Somervell and Joseph S. Coté. It is listed on The National Register of Historic Places."

At the library, my husband and I both needed to reactivate our accounts due to inactivity. Then, as he wandered the stacks, I created a long list of holds I want to read. It felt a bit like making a wish list for Santa. How had I forgotten this amazing treasure?

At the library, my husband and I both needed to reactivate our accounts due to inactivity. Then, as he wandered the stacks, I created a long list of holds I want to read. It felt a bit like making a wish list for Santa. How had I forgotten this amazing treasure? Now I sit with three books on the desk beside me. Sometimes the Wolf by local author, Urban Waite. Lab Girl , a memoir by Hope Jahren recommended by a friend. Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi, the Seattle Reads title for 2018. It’s a constantly changing collection always at hand to distract me from shopping, cooking, writing, teaching, cleaning, laundry, exercise.

So many wonderful library books to fill the dark days of winter. What are you reading? What do you recommend I add to my list? Have you visited your local library lately?

Published on January 12, 2018 16:06

December 26, 2017

A Boxing Day Special for You!

There are a few competing stories for the origin of the name [Boxing Day], but none are definitive. The first is that the day after Christmas was when servants of the wealthy were given time off to visit their family, as they were needed to work on Christmas Day. Each servant would be given a box to take home with food, a bonus and gifts. Another theory is that in the Victorian era, churches often displayed a box for parishioners to donate money. Also, it was customary for tradespeople to collect 'Christmas boxes' of money or gifts on the first weekday after Christmas as a thank you for good service over the year. (

Are you ready to load that new Kindle with hours of reading pleasure? Or perhaps you’re adding new titles to a much-loved e-reader in preparation for the long winter months ahead. Do you have friends and family who need reading suggestions?

With a slight nod to my humble Irish ancestry, I’d like to suggest a little something for your metaphorical Christmas box this Boxing Day. My third novel, Walking Home, is available today and tomorrow for only $0.99!

In Walking Home, Kidane flees violence in the Horn of Africa only to find the nightmares and despair of his past follow him to Seattle. A new country, a new hope, and a new love may not be enough to save him. Walking Home explores the challenges immigrants face in their search for belonging and a place to call home. This stirring journey into the world of African refugees offers readers a powerful coming of age tale that is both heartwarming and haunting.

Click HERE (link) to buy Walking Home today for only $0.99

Published on December 26, 2017 08:46

December 19, 2017

Morning Musings of Mexico City

Wind and rain lash my front window on this cold Seattle morning. I longed for days like this when I lived in Mexico City. Now I long for the dry warm air I once knew. I sit at my dining table in the dim light with coffee, pen and notebook, the large window framing the gray morning, watching a hummingbird land on the swinging feeder.

I scribble my morning musings of Mexico City. I left in 1984 and returned only once the following year. If not for the sore joints, gray hair and wrinkles, it would feel like yesterday. It was only five and a half years – a lifetime for a young woman seeking self.

I did not put up a Christmas tree this year, did not carefully unwrap each Mexican ornament – tiny painted gourds and straw miniatures of baskets, animals and stars, each with a length of bright red yarn. I miss that annual ritual of unwrapping and finding just the right spot on the tree, of carefully tying the red yarn, of remembering the markets of Mexico City where I selected each ornament.

I remember the poinsettia-filled roundabouts and medians of the major downtown streets and the neighborhood posadas, street re-enactments of the biblical Christmas story. I remember the scent of cinnamon and coffee, tortillas and tamales, spicy mole, steaming pozoleand sweet atole. I stare at the Seattle rain remembering the sights and smells of Mexico City and know I will return.

I remember the poinsettia-filled roundabouts and medians of the major downtown streets and the neighborhood posadas, street re-enactments of the biblical Christmas story. I remember the scent of cinnamon and coffee, tortillas and tamales, spicy mole, steaming pozoleand sweet atole. I stare at the Seattle rain remembering the sights and smells of Mexico City and know I will return.

Published on December 19, 2017 11:58

November 24, 2017

The Gift

The day after Thanksgiving, the house is quiet. Last night the energy and chatter of fourteen sisters, nieces, nephews, and significant others bounced off these walls, a large furry family member curled at our feet under this large table where I now write. I’m dawdling. I have lost the habit of daily writing, of beginning each day scribbling words on the page – sometimes meaningless babble, other times scenes that find their way into a project at hand or inspire a new one. A routine ignored in the chaos of a busy life.

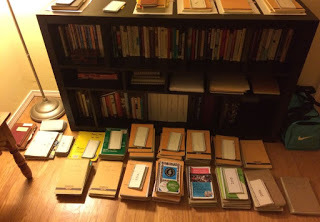

The evidence? I begin a rewrite of one plot line in my current memoir project. Frustration gets the better of me as I struggle with facts and chronologies. I dig out my notebooks – two large white plastic laundry baskets full – and search for those pertaining to the story at hand. The baskets hold a jumbled mess of notebooks dated 1974 to 2017. Following the advice I often give my students – get organized! – I sort and stack the notebooks chronologically by year. Once finished, the evidence is glaring: some years display hefty piles ranging from seven to twelve notebooks, 2017 has two.

The evidence? I begin a rewrite of one plot line in my current memoir project. Frustration gets the better of me as I struggle with facts and chronologies. I dig out my notebooks – two large white plastic laundry baskets full – and search for those pertaining to the story at hand. The baskets hold a jumbled mess of notebooks dated 1974 to 2017. Following the advice I often give my students – get organized! – I sort and stack the notebooks chronologically by year. Once finished, the evidence is glaring: some years display hefty piles ranging from seven to twelve notebooks, 2017 has two.

I spend three and a half days in Mesa, Arizona. One cousin, the flight attendant, flies me down; the other cousin puts me up in her hillside home. A secret mission to surprise my aunt, their mother, on her 90th birthday. My aunt shows no sign of the dementia that cursed my mother, her sister. She’s bright and spry, attending yoga classes, driving her own car, and remembering anecdotes from the past better than either of her daughters or me.

I spend three and a half days in Mesa, Arizona. One cousin, the flight attendant, flies me down; the other cousin puts me up in her hillside home. A secret mission to surprise my aunt, their mother, on her 90th birthday. My aunt shows no sign of the dementia that cursed my mother, her sister. She’s bright and spry, attending yoga classes, driving her own car, and remembering anecdotes from the past better than either of her daughters or me.

My aunt inspires and encourages me. She asks about my writing, about when The Thirty-Ninth Victim will be re-released, about why the unpublished memoir I’ve written about my mother has not been published, about what I am working on now. She wants to read more of my work. That alone is enough to bring me back to my notebook.

My aunt inspires and encourages me. She asks about my writing, about when The Thirty-Ninth Victim will be re-released, about why the unpublished memoir I’ve written about my mother has not been published, about what I am working on now. She wants to read more of my work. That alone is enough to bring me back to my notebook.

Published on November 24, 2017 15:00

November 6, 2017

Illusive Time

Seven weeks have passed since I last posted. How is that possible? How can days pile into weeks without my notice? I look at my calendar. I open iCloud photos. I search for highlights of time lost.

The week after my last post, fall quarter began with unusually large classes in a partially unfinished building. I'm in a spacious classroom with floor to ceiling windows that frame the changing seasons, and the folks in IT ironed out the frustrating computer issues by week two. Or perhaps week three.

By mid October, classes were settling, and it was time to winterize the garden. I’ve had a board and brick bookcase since the early 1980s. It was in my work office for close to thirty years until the building was torn down and I landed in a much smaller space. We re-purposed a few of the boards and bricks and brought in the potted plants for an indoor garden. Blooms blur seasonal change.

By mid October, classes were settling, and it was time to winterize the garden. I’ve had a board and brick bookcase since the early 1980s. It was in my work office for close to thirty years until the building was torn down and I landed in a much smaller space. We re-purposed a few of the boards and bricks and brought in the potted plants for an indoor garden. Blooms blur seasonal change. In late October, I accepted a new personal truth: afternoon gym workouts weren’t going to happen. So I began 6 a.m. spin classes. Enough time for an intense hour-long workout and still make it to my first class. I can’t pretend I like it, but I feel good when it’s over.

In late October, I accepted a new personal truth: afternoon gym workouts weren’t going to happen. So I began 6 a.m. spin classes. Enough time for an intense hour-long workout and still make it to my first class. I can’t pretend I like it, but I feel good when it’s over. The month ended with streams of trick-or-treaters at our door. Such a change in West Seattle. When our daughter was knocking on doors, my husband watching from the sidewalk, she was one of few kids in the neighborhood. Now they seem to be sprouting like autumn mushrooms in the Northwest forests.

We are in a constant state of change as nature gifts us lovely sunsets and hummingbirds that flutter through the leafless branches and feed just beyond my office window.

We are in a constant state of change as nature gifts us lovely sunsets and hummingbirds that flutter through the leafless branches and feed just beyond my office window.

I've looked at life from both sides now

I've looked at life from both sides nowFrom win and lose and still somehow

It's life's illusions I recall

I really don't know life at all

Joni Mitchell, Both Sides Now

Published on November 06, 2017 17:27