Arleen Williams's Blog, page 22

May 7, 2015

Finding Home: Other Voices

How do we hold our childhood memories? How does an adult recall the fears of a six-year-old in a tornado? Today Jan Wissmar shares her story.

My father built the three houses I lived in growing up but it’s the first one that flashes through my mind whenever I hear the word “tornado.” I return to the small concrete bunker smelling of sawdust. I hear the cackling radio and see my mother’s tears in the dim light as the baby cries and my brother feigns bravery.

My father built the three houses I lived in growing up but it’s the first one that flashes through my mind whenever I hear the word “tornado.” I return to the small concrete bunker smelling of sawdust. I hear the cackling radio and see my mother’s tears in the dim light as the baby cries and my brother feigns bravery. I was six when it happened; running barefoot through nearby farms, stealing pea pods and prying them open for the sweet goodies inside. When I was a child I only went inside when called. Or when hungry or scared.

It came on a sweaty afternoon in late spring, a time when Black-eyed Susans, with their cheery faces and lop-eared petals, grew thick and wild everywhere in central Michigan and you could pick as many as you wanted which is what I was doing when I heard the neighbor's rabbits squealing and ran over to see why. As in many rural towns, our neighbors kept chickens and rabbits trapped in small, wire cages.

“What’s wrong?” I asked, freeing the rabbits. They had black and white spots and were so fat they could barely hop. The neighbor spied me from her window and ran outside screaming.

“Your momma’s gonna whip you good!”

I started running but spotted her dog on his heavy chain whining piteously. He was my friend and something wicked was coming so I had to free him as well. What was it? An ogre perhaps, or maybe a cyclops. A massive, one-eyed, child-eating cyclops with blood-stained teeth and a laugh that turned blood to ice. I had to free as many animals as I could so they could run away.

Our house was built into a hill, not a particularly steep hill but one with enough slope to ski down in the winter when there was snow. Beyond our yard was Thorny Woods, a swath of birches filled with impenetrable blackberry vines so bewitched they towered over me. I arrived home to find my mother standing at the back door with the baby in her arms screaming my name, my toddler brother wrapped around her legs. Overhead gray clouds drooped like the udders of deranged milk cows. “Get down to the cellar,” she ordered.

"I can't!”

“Take your brother and get down there. Now!"

Our house had four levels. The bedrooms were upstairs, the kitchen and living areas at ground level, the garage beneath the kitchen and beneath the garage, the cellar. I couldn’t go through the garage because of the horror which mother knew as she shoved me toward the stairs with her one free hand. "For crying out loud! They're only animals!"

Our house had four levels. The bedrooms were upstairs, the kitchen and living areas at ground level, the garage beneath the kitchen and beneath the garage, the cellar. I couldn’t go through the garage because of the horror which mother knew as she shoved me toward the stairs with her one free hand. "For crying out loud! They're only animals!" I grabbed my brother’s chubby paw and started to cry, each step down the stairs worse than the one before until I reached the bottom and the lights flickered. I tried not to look but blood was everywhere, pooling in lakes all over the concrete from my father’s latest kills, the rabbits, the deer, the pheasants, now hanging on meat-hooks, their sad eyes watching me. I froze as Mother ran through the blood to open the trap door and then disappeared into the hole. My brother broke free of my grasp and ran after her. He slipped and fell into the stain, then rose and with a sob followed her.

Mother re-emerged seconds later, picked me up savagely and carried me across the pools of blood. Once in the bunker she tried to read a book in the dim light from the camp stove but we couldn’t hear the words over the sound of the monster raging above. The baby cried, my brother cried and finally my mother cried.

After what seemed like hours, suddenly it was quiet. Maybe it’s over I thought, but I was wrong. We heard a sucking noise and, without warning, the water in the toilet shot up to the ceiling like a geyser, followed by a rumbling in the earth as it threatened to rip apart beneath us. We were all screaming. The banshees, the baby, my brother, mother and me.

Anyone who’s been through a tornado knows that in the aftermath a strange calm fills the air. Once the winds finally stopped howling we emerged like zombies into the daylight. Slowly other zombies joined us. The still air like a cocoon. The sun, blinding.

With the exception of broken windows, my father’s first house was spared. However, the house next door looked like a pile of pick-up sticks. I heard they rebuilt but by then father had tired of the corporate world and we were gone.

Jan (JT Twissel) traveled all over the country as a child but now makes her home in the beautiful (though parched) San Francisco Bay Area. She somehow managed to trick UC Berkeley into giving her a degree in English and then worked as a documentation and process specialist for software companies for many years while raising children and pets (alas, no rabbits). Currently she is trying to figure out how to market her third book (WILLFUL AVOIDANCE) which deals with divorce, starting again, dealing with the government, working with dying children and avoiding the wrong man. She blogs at http://www.jttwissel.comand tweets at @jttwissel. Her other books are FLIPKA and THE GRADUATION PRESENT.

Jan (JT Twissel) traveled all over the country as a child but now makes her home in the beautiful (though parched) San Francisco Bay Area. She somehow managed to trick UC Berkeley into giving her a degree in English and then worked as a documentation and process specialist for software companies for many years while raising children and pets (alas, no rabbits). Currently she is trying to figure out how to market her third book (WILLFUL AVOIDANCE) which deals with divorce, starting again, dealing with the government, working with dying children and avoiding the wrong man. She blogs at http://www.jttwissel.comand tweets at @jttwissel. Her other books are FLIPKA and THE GRADUATION PRESENT. Don't want to miss a single post? Get them delivered by entering your email in the box in the lower right To read the prior posts in this mini-memoir series, go to the posts listing in the left side bar and click on "March."

Published on May 07, 2015 06:52

May 5, 2015

Finding Home: Santa Cruz Cottage

Readers who know me well say they see me in Carolyn, a protagonist in all three novels of The Alki Trilogy. I admit there are similarities between Carolyn and me, and I've certainly drawn from my personal experiences to create all my characters. Among those similarities are Carolyn's cottage in Biking Uphill as well as our shared failure to fit into small town California university life

When I returned to Santa Cruz from Caracas,the boyfriend and I rented a second-story walk-up that felt like a cheap hotel. Still, it was better than moving back into the fancy studio we'd shared before my six months in Venezuela. The rumors circulating on campus about that place made re-entry impossible. The boyfriend and I lasted a month together.

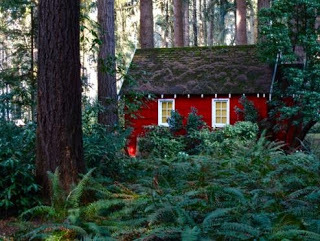

I landed in a faded red cottage with peeling white trim, a covered porch complete with a swing hanging from rusty chains. Like Carolyn's cottage, mine stood in the overgrown backyard of an enormous gingerbread Victorian on the hill that rose behind downtown Santa Cruz halfway to the university. Unlike Carolyn, I never owned or rode a bicycle in Santa Cruz, but I was every bit the lonely college student that she was.

I have no photos of my cottage. Can you imagine this with peeling paint?Despite my heartbreak as well as my inability to adjust to life either in Santa Cruz or at the university, I loved my cottage. It was the perfect hide-away. A place to lick my wounds and ponder my next move. The cottage was tiny. The front door opened to a small living room, and you walked through a smaller kitchen to exit through the back door. A tiny bathroom and a wall ladder to a minuscule loft were just inside that back door.

I have no photos of my cottage. Can you imagine this with peeling paint?Despite my heartbreak as well as my inability to adjust to life either in Santa Cruz or at the university, I loved my cottage. It was the perfect hide-away. A place to lick my wounds and ponder my next move. The cottage was tiny. The front door opened to a small living room, and you walked through a smaller kitchen to exit through the back door. A tiny bathroom and a wall ladder to a minuscule loft were just inside that back door. Every night I climbed the ladder. The loft ceiling was so low I couldn't sit upright, but the window that opened to the overgrown backyard and forest beyond more than compensated for the limited headroom. A tall fir towered over my cottage, the wide branches brushing the roof and window in heavy winds. From the loft, I felt the peace of nature, the trees and forests of my childhood.

I loved my cottage, but it wasn't home. I did not belong to the place or to the folks inhabiting it despite the handful of special friends I'd made there. I finished my coursework for my bachelor's degree, but still needed to complete a research project or comprehensive exams to earn my degree. That's when my brother showed up and invited me to his home in Hawaii. How could I refuse the lure of the North Shore?

Years later, on a trip with my daughter, I visited my old cottage. I was re-tracing old stomping grounds and sharing stories with her. When we turned the rental car down the winding cul-de-sac on a route engrained deep in memory despite having lived there less than a year, I was stunned. The little cottage not only still stood, but was all painted and pretty. It stood in plain sight smack in the center of a dusty, dirty construction site, the overgrown yard destroyed, unfinished houses on both sides.

A bit like this without any trees.That last Santa Cruz visit was fifteen years ago. Today, I do not know if my little cottage remains in anything more than wisps of memory. For me it will never be home, but it will always represent an interlude, a sanctuary in the confusions of youth.

A bit like this without any trees.That last Santa Cruz visit was fifteen years ago. Today, I do not know if my little cottage remains in anything more than wisps of memory. For me it will never be home, but it will always represent an interlude, a sanctuary in the confusions of youth.Don't want to miss a single post? Get them delivered by entering your email in the box in the lower right To read the prior posts in this mini-memoir series, go to the posts listing in the left side bar and click on "March."

Published on May 05, 2015 06:42

April 30, 2015

Finding Home: Other Voices

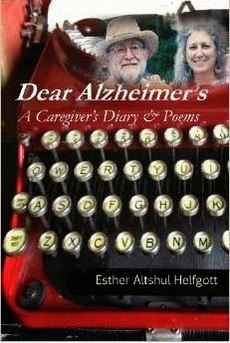

For a change of pace, I'm pleased to share the work of author and poet, Esther Altshul Helfgott today.

Spouse as Home

I didn't know he

was my shul

my language

my mother tongue

and prayer

the zeyde I lost,

and bubbes

I never had.

Or that he was my homeland.

And exile.

My nakedness.

I didn’t know

when I met him

twenty-five years ago

that I had needed

a place to

dwell

in.

Or that knowing

turned less

into more

And more

into

less.

Oh,where shall

Idwell

when he’s

gone

Whereshall

I

when

he’sFrom Dear Alzheimer’s: A Caregiver’s Diary & Poems(Yakima, WA: Cave Moon Press, 2013; e-version: Two Sylvias Press, 2013)Also appears in Beyond Forgetting: Poetry and Prose about Alzheimer's Disease. Holly Hughes, ed. (Kent State University Press) 2009; forthcoming in West Coast Women's Jewish Poetry Anthology

***

I Sat Upon His GraveI watched the letters of his name

upon the stone.I cried until they came alive—

the letters of his name.The grass was warm beneath me.My face was hot

from the sun.I rose to say goodbye

and touch his name.The cemetery

transmogrified.The ground swelled.His arms reached out to me—

and I was home.

From Dear Alzheimer’s: A Caregiver’s Diary & Poems(Yakima, WA: Cave Moon Press, 2013; e-version: Two Sylvias Press, 2013)***

I buy a new pen—you slip from the nib—I write us home

from Listening to Mozart: Poems of Alzheimer’s(Cave Moon Press, 2014; Two Sylvias Press, 2014, e version)

Esther Altshul Helfgott is a non-fiction writer and poet with a Ph.D. in history from the University of Washington. She’s the founder of the 25-year-old It’s About Time Writer’s Reading Series, the longest running non-university-supported reading series in Seattle. (About Time meets the 2nd Thurs of every month at the Ballard library). Esther is the author of Listening to Mozart: Poems of Alzheimer’s (Yakima, WA.: Cave Moon Press, 2014) and Dear Alzheimer’s: A Caregiver’s Diary & Poems (Yakima, WA: Cave Moon Press, 2013) and other works. She has a bunch of kids and grandkids who keep her hopping—and a big German Shepherd named Emma. www.estherhelfgott.com

Spouse as Home

I didn't know he

was my shul

my language

my mother tongue

and prayer

the zeyde I lost,

and bubbes

I never had.

Or that he was my homeland.

And exile.

My nakedness.

I didn’t know

when I met him

twenty-five years ago

that I had needed

a place to

dwell

in.

Or that knowing

turned less

into more

And more

into

less.

Oh,where shall

Idwell

when he’s

gone

Whereshall

I

when

he’sFrom Dear Alzheimer’s: A Caregiver’s Diary & Poems(Yakima, WA: Cave Moon Press, 2013; e-version: Two Sylvias Press, 2013)Also appears in Beyond Forgetting: Poetry and Prose about Alzheimer's Disease. Holly Hughes, ed. (Kent State University Press) 2009; forthcoming in West Coast Women's Jewish Poetry Anthology

***

I Sat Upon His GraveI watched the letters of his name

upon the stone.I cried until they came alive—

the letters of his name.The grass was warm beneath me.My face was hot

from the sun.I rose to say goodbye

and touch his name.The cemetery

transmogrified.The ground swelled.His arms reached out to me—

and I was home.

From Dear Alzheimer’s: A Caregiver’s Diary & Poems(Yakima, WA: Cave Moon Press, 2013; e-version: Two Sylvias Press, 2013)***

I buy a new pen—you slip from the nib—I write us home

from Listening to Mozart: Poems of Alzheimer’s(Cave Moon Press, 2014; Two Sylvias Press, 2014, e version)

Esther Altshul Helfgott is a non-fiction writer and poet with a Ph.D. in history from the University of Washington. She’s the founder of the 25-year-old It’s About Time Writer’s Reading Series, the longest running non-university-supported reading series in Seattle. (About Time meets the 2nd Thurs of every month at the Ballard library). Esther is the author of Listening to Mozart: Poems of Alzheimer’s (Yakima, WA.: Cave Moon Press, 2014) and Dear Alzheimer’s: A Caregiver’s Diary & Poems (Yakima, WA: Cave Moon Press, 2013) and other works. She has a bunch of kids and grandkids who keep her hopping—and a big German Shepherd named Emma. www.estherhelfgott.com

Published on April 30, 2015 06:27

April 28, 2015

Finding Home: Caracas, Venezuela

In July 1977 the boyfriend and I landed in a world so alien to me I felt numb. I'd been to Mexico City. I'd experienced the density, rhythm, and flavor of a huge Latin American city. Still, Caracas in the late seventies was running on oil boom fever. You could feel it in the air, smell it on the winds blowing through the city, see it in the construction cranes dotting the skyline. The city is in a valley and at the time maintained rigid laws limiting the growth on the surrounding mountainsides. With nowhere to go, the city built skyward.

We stayed in the boyfriend's family home, and I landed a job right away at the British Embassy school - with a name like Arleen Feeney, I managed to exaggerate my Irish-ness. Before returning to his studies in Santa Cruz, the boyfriend arranged for me to live with his sister and brother-in-law in one of the many new residential developments at the limits of the city. The commute was dreadful. I took shared cabs, small vans crammed with ten to twelve commuters. You had to shout your stop over the heads and voices of the other passengers. I'd spend the hour plus commute rehearsing what I'd have to say and worrying I'd forget when to shout it.

As dreadful as the commute was, the family life was worse. I felt I was under constant surveillance and scrutiny. In all fairness to the boyfriend's family, I imagine they felt they needed to take care of me. But I wasn't used to being taken care of and wasn't liking it much at all. I remember once getting a deep cleansing facial - a gift from one of my wealthy students at her favorite spa - and the boyfriend's mother insinuated the ensuing redness and rash was caused by the unshaven chin of someone other than her beloved son. What do they say about living up to others' expectations? I suppose I figured if they'd already condemned me for something I hadn't done, maybe I should consider doing it.

As dreadful as the commute was, the family life was worse. I felt I was under constant surveillance and scrutiny. In all fairness to the boyfriend's family, I imagine they felt they needed to take care of me. But I wasn't used to being taken care of and wasn't liking it much at all. I remember once getting a deep cleansing facial - a gift from one of my wealthy students at her favorite spa - and the boyfriend's mother insinuated the ensuing redness and rash was caused by the unshaven chin of someone other than her beloved son. What do they say about living up to others' expectations? I suppose I figured if they'd already condemned me for something I hadn't done, maybe I should consider doing it.Salvation came from the same lovely student who gifted me my first spa visit. She was recently married and owned a vacant downtown condo. She insisted I'd be doing her a favor by living there. I'd never known such luxury. The servants' quarters seemed as large as any of my prior apartments. There was an ornate iron balcony overlooking a large park, the view and peace marred only by construction cranes and noise. The condo was fully furnished, complete with linens, kitchenware, and a stocked liquor cabinet.

When I told the boyfriend's family I would be living alone downtown, they were horrified. And then, they quickly washed their hands of any assumed responsibility for my physical or moral well-being. I was ecstatic. I certainly hadn't found home, but I loved teaching and filled weekdays with embassy classes and weekends with outings. The other teachers were largely older British and Australian ex-pats who knew how to have a good time. I took lessons. I'll never forget slurping oysters and lime in a narrow canoe as fast as the local fisherman could catch and shuck them. Where was that? Who was I with? Did it happen with the colors and fragrances I am now sensing as I write these words? Memory has a veiled dreamlike quality. I had no camera. This was before computers or cell phones. Memory consists of what I still hold or took the time to describe in a notebook. Connection with the boyfriend was limited to the occasional letter.

Six months later I returned to Santa Cruz to find that the boyfriend had left me behind in much the same ways I had abandoned him. Maybe the tiny studio with the bright blue swimming pool was where he took his flings when I was in his homeland. But who was I to point fingers? After all, I had indeed lived up to expectations thrust upon me. Returning to campus was another challenge. I heard too many whispered stories of the boyfriend's adventures in my absence and felt too much remorse about my own.

We tried to make a go of it, even renting a different apartment. I lasted about a month with him. I didn't find home in Caracas, in Santa Cruz, or with the boyfriend. I was so busy looking for a sense of belonging elsewhere, instead of within myself, my first love ended without finding home.

Don't want to miss a single post? Get them delivered by entering your email in the box in the lower right To read the prior posts in this mini-memoir series, go to the posts listing in the left side bar. If no longer visible, just click on "March."

Published on April 28, 2015 06:37

April 23, 2015

Finding Home: Other Voices

The Finding Home blog series began on March 5. When I invited other writers to share their stories on the subject of home, I had no idea of the depth and breadth of works I would receive. Today, I am pleased to offer a story of trials and triumphs from author, Mindy Halleck. Enjoy!

A Sense of Home

My childhood homes were many, chaos filled and transitory. My mother’s wanderlust disrupted life whenever we found a place to call home. I attended too many schools to remember, learned to disconnect from friends with ease, finally making no friends, because within that ‘ease’ was heartbreak every time I had to say goodbye. Those goodbyes generally occurred every year. That was the timeline: one year. Then mom got itchy feet, sold everything she owned, and move on to a new life, believing the grass is always greener somewhere else. It never was.

These days I jokingly call her the merchant of chaos, but that appellation is a thin veil masking the pain, abandonment and shattered reality of what should have been a refuge. Because of her, the concept of ‘home’ was alien to me; what is home? What and who should be in it?

I recall vividly, when I was ten years old, returning from school one day to a garage sale on the front lawn, all our furniture being sold, my bedroom set included. I loved that bedroom set with a French provincial white four poster bed and matching vanity. It was mine. How could she sell it?

That day, my bedroom furniture went off with an old woman. The red tail lights of her truck at the corner of Stanton Street, blinked, then turned onto 35th and disappeared. A deep root of resentment set in my bones that day. I knew with the fading of those tail lights we would soon move, leave our house, school, friends and start over, again.

Over the next three years my parent’s fights grew to legendary proportions; arrests, house fires, crashed cars, broken bones, or them disappearing for days on end, leaving me to tend my three younger brothers. I learned home was not a safe place, not a place where I could get attached to anything, or trust those whom I should have been able to trust the most. And though they loved us, my brothers and me, we were forgotten in their war. Dad slipped into alcoholism and mom, her bizarre gypsy ways, including, but not limited to giving things away with no regard for what was paid for those things or what they meant to the holder. Twice we ended up in a house with no furniture. Dad would buy new, she’d get mad and sell it all again. Dad finally disappeared with the last furniture sale.

I left ‘home’ at thirteen, then moved back because I had nowhere to go. At sixteen I left again, for good. I couch-surfed, lived in a car, a church basement and was blessed by a cousin who took me in.

It took forty years of roaming humanity’s desert to finally find a safe place to call home. Now, I have one with gardens, water view and a loving husband who swears (after our last move) we will never move again–music to my ears. We lived in our last house over a decade and we will stay in this one till we’re too old to go up the stairs, then it’s a condo, we’ve decided. I thrive in the normalcy of his steadfast plans. I’ve learned home is more than a house that can be sold, left and abandoned, it’s who is in that house that makes it a sanctuary. Home is no longer an alien concept to me. Home is my unwavering husband, no matter where we live.

My wander-lusting ‘merchant of chaos’ mother resents my normalcy and mocks me with her teen-angst voice whenever we argue. We argue a lot. Thankfully I’ve come to understand she is not a well person. She is an eternally rebellious and trapped teenager who wants to leave home, and I am the parent. To her any belongings, children, husbands or homes are shackles and must be banished, escaped and left behind.

For example, last year after we moved her into a fairly posh retirement residence, they had a Halloween dance at a neighboring rec-center. After not speaking to me for a week because I left her in a ‘home’, she called and asked if I’d drive her to the party. When I arrived she descended the stairs slowly so I could take in the full view of her costume; a black and white striped prison uniform with a chain belt.

She got into my car without a word, sat smiling and looking forward, her point made.

I shook my head, started the engine and said, “Do we need to stop somewhere to pick up a ball and chain?”

Now, that one year mark has hit. She’s serving her sentence in the ‘home’ but is planning an escape. She has one friend left who can drive (during the day) and they think they’re going on a road trip, you know to where that grass is greener, and apparently where men have hair and teeth. They are in their eighties and need naps about every two hours. I don’t think they’ll get far, I think that hair and teeth will be fake, and I know the grass won’t be greener.

We have told her if she tries to leave this safe haven we will never help her find one again. She knows we mean it this time. And though she has these little rebellions, I don’t think she will actually leave the retirement center where they feed, medicate, entertain and allow her the freedom to come and go with no strings. I think she’s finally grown up enough to recognize the need for a home.

Our mother, regardless of antics loves us deeply in her own dysfunctional way, and in that love is our sense of humor, humility, and yes, finally a sense of familial home. Mindy Halleck is a Pacific Northwest author who in 2014, after many years as a non-fiction author released her debut novel,

Return To Sender

–a literary thriller set on the Oregon Coast in the 1950’s. The novel is based on one of her short stories, The Sound of Rain, which received Honorary Mention in a Writer’s Digest Literary Contest. Halleck also blogs at Literary Liaisons and is an active member of the Pacific Northwest writing community. In addition to being a writer, Halleck is a happily married, globe-trotting beachcomber and three-time cancer survivor. www.MindyHalleck.com

Mindy Halleck is a Pacific Northwest author who in 2014, after many years as a non-fiction author released her debut novel,

Return To Sender

–a literary thriller set on the Oregon Coast in the 1950’s. The novel is based on one of her short stories, The Sound of Rain, which received Honorary Mention in a Writer’s Digest Literary Contest. Halleck also blogs at Literary Liaisons and is an active member of the Pacific Northwest writing community. In addition to being a writer, Halleck is a happily married, globe-trotting beachcomber and three-time cancer survivor. www.MindyHalleck.com

A Sense of Home

My childhood homes were many, chaos filled and transitory. My mother’s wanderlust disrupted life whenever we found a place to call home. I attended too many schools to remember, learned to disconnect from friends with ease, finally making no friends, because within that ‘ease’ was heartbreak every time I had to say goodbye. Those goodbyes generally occurred every year. That was the timeline: one year. Then mom got itchy feet, sold everything she owned, and move on to a new life, believing the grass is always greener somewhere else. It never was.

These days I jokingly call her the merchant of chaos, but that appellation is a thin veil masking the pain, abandonment and shattered reality of what should have been a refuge. Because of her, the concept of ‘home’ was alien to me; what is home? What and who should be in it?

I recall vividly, when I was ten years old, returning from school one day to a garage sale on the front lawn, all our furniture being sold, my bedroom set included. I loved that bedroom set with a French provincial white four poster bed and matching vanity. It was mine. How could she sell it?

That day, my bedroom furniture went off with an old woman. The red tail lights of her truck at the corner of Stanton Street, blinked, then turned onto 35th and disappeared. A deep root of resentment set in my bones that day. I knew with the fading of those tail lights we would soon move, leave our house, school, friends and start over, again.

Over the next three years my parent’s fights grew to legendary proportions; arrests, house fires, crashed cars, broken bones, or them disappearing for days on end, leaving me to tend my three younger brothers. I learned home was not a safe place, not a place where I could get attached to anything, or trust those whom I should have been able to trust the most. And though they loved us, my brothers and me, we were forgotten in their war. Dad slipped into alcoholism and mom, her bizarre gypsy ways, including, but not limited to giving things away with no regard for what was paid for those things or what they meant to the holder. Twice we ended up in a house with no furniture. Dad would buy new, she’d get mad and sell it all again. Dad finally disappeared with the last furniture sale.

I left ‘home’ at thirteen, then moved back because I had nowhere to go. At sixteen I left again, for good. I couch-surfed, lived in a car, a church basement and was blessed by a cousin who took me in.

It took forty years of roaming humanity’s desert to finally find a safe place to call home. Now, I have one with gardens, water view and a loving husband who swears (after our last move) we will never move again–music to my ears. We lived in our last house over a decade and we will stay in this one till we’re too old to go up the stairs, then it’s a condo, we’ve decided. I thrive in the normalcy of his steadfast plans. I’ve learned home is more than a house that can be sold, left and abandoned, it’s who is in that house that makes it a sanctuary. Home is no longer an alien concept to me. Home is my unwavering husband, no matter where we live.

My wander-lusting ‘merchant of chaos’ mother resents my normalcy and mocks me with her teen-angst voice whenever we argue. We argue a lot. Thankfully I’ve come to understand she is not a well person. She is an eternally rebellious and trapped teenager who wants to leave home, and I am the parent. To her any belongings, children, husbands or homes are shackles and must be banished, escaped and left behind.

For example, last year after we moved her into a fairly posh retirement residence, they had a Halloween dance at a neighboring rec-center. After not speaking to me for a week because I left her in a ‘home’, she called and asked if I’d drive her to the party. When I arrived she descended the stairs slowly so I could take in the full view of her costume; a black and white striped prison uniform with a chain belt.

She got into my car without a word, sat smiling and looking forward, her point made.

I shook my head, started the engine and said, “Do we need to stop somewhere to pick up a ball and chain?”

Now, that one year mark has hit. She’s serving her sentence in the ‘home’ but is planning an escape. She has one friend left who can drive (during the day) and they think they’re going on a road trip, you know to where that grass is greener, and apparently where men have hair and teeth. They are in their eighties and need naps about every two hours. I don’t think they’ll get far, I think that hair and teeth will be fake, and I know the grass won’t be greener.

We have told her if she tries to leave this safe haven we will never help her find one again. She knows we mean it this time. And though she has these little rebellions, I don’t think she will actually leave the retirement center where they feed, medicate, entertain and allow her the freedom to come and go with no strings. I think she’s finally grown up enough to recognize the need for a home.

Our mother, regardless of antics loves us deeply in her own dysfunctional way, and in that love is our sense of humor, humility, and yes, finally a sense of familial home.

Mindy Halleck is a Pacific Northwest author who in 2014, after many years as a non-fiction author released her debut novel,

Return To Sender

–a literary thriller set on the Oregon Coast in the 1950’s. The novel is based on one of her short stories, The Sound of Rain, which received Honorary Mention in a Writer’s Digest Literary Contest. Halleck also blogs at Literary Liaisons and is an active member of the Pacific Northwest writing community. In addition to being a writer, Halleck is a happily married, globe-trotting beachcomber and three-time cancer survivor. www.MindyHalleck.com

Mindy Halleck is a Pacific Northwest author who in 2014, after many years as a non-fiction author released her debut novel,

Return To Sender

–a literary thriller set on the Oregon Coast in the 1950’s. The novel is based on one of her short stories, The Sound of Rain, which received Honorary Mention in a Writer’s Digest Literary Contest. Halleck also blogs at Literary Liaisons and is an active member of the Pacific Northwest writing community. In addition to being a writer, Halleck is a happily married, globe-trotting beachcomber and three-time cancer survivor. www.MindyHalleck.com

Published on April 23, 2015 06:29

April 21, 2015

Finding Home: The Boardwalk

I arrived by Greyhound in late summer. The Venezuelan boyfriend had been accepted at University of California Santa Cruz. He received a plane ticket and instructions from his government, and he wasn't happy about doing anything to risk his free ride. Still, I snuck in and out of his summer dorm for the weeks it took for to find an apartment and a job. The campus stood high in the rolling hills above town and food options were limited. The boyfriend had a college meal plan. I lived off vending machine peanuts, raisins, and orange soda.

With a sense of relief, I signed a rental agreement on our first apartment two blocks from the famous Santa Cruz Boardwalk with its gigantic roller coaster and endless stream of summer tourists. My first job in California was selling hotdogs and beer (though not yet 21) at a Boardwalk kiosk.

The apartment building was a converted tourist motel, and the apartment consisted of two connecting motel rooms with two doors opening from an outdoor walkway. One motel room held a large kitchen and bathroom. The other was the living room/bedroom. The boyfriend built a room-divider bookcase to create a private bedroom. He cut and sanded and varnished each of those boards on the walkway in front of our two front doors. It took days, which is why what happened when we moved out was so infuriating and heartbreaking.

The apartment building was a converted tourist motel, and the apartment consisted of two connecting motel rooms with two doors opening from an outdoor walkway. One motel room held a large kitchen and bathroom. The other was the living room/bedroom. The boyfriend built a room-divider bookcase to create a private bedroom. He cut and sanded and varnished each of those boards on the walkway in front of our two front doors. It took days, which is why what happened when we moved out was so infuriating and heartbreaking. Even though I loved the early morning beach, the winter beach, the beach when the tourists were gone, Santa Cruz never felt like home. I ran the beach and worked the Boardwalk until the end of the tourist season while the boyfriend spent every moment studying or playing chess at a local coffee shop.

Like Carolyn in Biking Uphill, I never felt I belonged to any of the diverse groups populating the small community: the townies, the students, the tourists, the surfers, the hippies, the vets. Unable to afford to return to school until I established state residency, I tried becoming a townie. After working a season on the Boardwalk, I found an office job at a local department store. I was twenty years old working with lifers twice my age. When I finally re-started my Bachelor's degree, I felt old, unable to fit in to the college scene there anymore than I had at the two universities I'd attended in Seattle. After less than a year at UCSC, I decided to leave.

By then we owned a small car, and we decided to move. We rented a new apartment, a tiny studio in a rather fancy development with a swimming pool. It was for the boyfriendAs I remember it, I did most of the moving. I made a series of trips back and forth across town, the small car packed tight with boxes of accumulated housewares, clothing, and books. The boyfriend had carefully dismantled the bookcase and stacked the boards in the middle of the room, but I simply couldn't get them into the car. I still had keys and the month had not ended, but when I returned to collect the final load a day or two later with a borrowed car, the boards were gone.

"Thought you were out," the landlord said. "Sold them boards to the roofers. They were happy to have 'em."

I suppose that was the beginning of the end, the souring of my first love, but I didn't know it yet. The boyfriend and I were heartbroken and furious, but not with each other. Not then. Not yet.

Don't want to miss a single post? Get them delivered by entering your email in the box in the lower right To read the prior posts in this mini-memoir series, go to the posts listing in the left side bar. If no longer visible, just click on "March."

Published on April 21, 2015 06:22

April 16, 2015

Finding Home: Other Voices

Please welcome Eleanor Parker with her lovely guest post based on her memoir-in-progress titled, Home in Three Acts.

ACT I: 1957-2005: Military Housing

By my eighteenth birthday, I’d lived in four countries. This Army brat’s idea of home was a temporary place, where my roots had grown accustomed to remaining shallow, but with strong runners that grew horizontally outward and downward from the plant. As far back as I can remember, every three to four years, I was carefully uprooted, tenderly cut from the main plant, and transplanted at the family’s next duty station, where again I’d thrive as best I could.

My mother’s habit, which later became my own, was to set up the children’s bedrooms first to make us kids feel comfortable, safe, and secure in a new place. Invariably favorite curtains wouldn’t fit the new windows of our next military quarters, the bathroom colors had changed, which meant new towels were added to an already large mismatched collection, or I was forced to share a bedroom with my youngest sister, but I was a flexible child. A house didn’t mean all that much to me—leaving new friends was an expected part of the life my parents had chosen. Besides, I loved meeting and making new friends at new postings, vacationing in exotic places, and traveling back and forth across the Atlantic Ocean with stops in Puerto Rico to visit family.

I graduated from college and worked in the DC area as a single woman for seven years, where I met and married an Army officer. At our wedding reception on Fort Myer, overlooking the Potomac River, I thought my new husband was my soul mate. Maybe he was, and with him came the promise of more travel and exotic vacations, a lifestyle I wanted for my children. When the kids were nine and seven, my 57-year old mother died suddenly, shattering a lifelong dream of living close to her. She was the epitome of home to me, where love, safety, fun, and warmth lived. Home and the world no longer felt safe, fun, or warm without her.

With my mother gone, the Army sent my little family on one more Army tour and we moved from Northern Virginia to Brussels, Belgium, where we lived in a vibrant ex-pat community for the next thirteen wonderful years. Our stay in Brussels was the longest I’d ever lived in one place, and it was a great place to raise children. I was again responsible for creating a home for my growing family.

In our ninth year in Brussels, when my oldest child left for university in the United States, early stresses in our marriage were no longer shrouded and were impossible to ignore. We bought un mas in the Provençal village of Uchaux, in the south of France, the way some people believe a new baby can ‘fix’ a broken marriage. For the next four years, we were blissfully happy. Plans were made to turn the mas into a B&B, where I would lead art workshops in the French countryside and write a novel. My husband would relax under the plataintree in the garden, watching the farmers next door till the soil for new grapevines after nearly thirty years in the Army. The word idyllic was a close description to what I planned for us in the home where we’d retire in a few years time. But sometimes you can’t see what is coming toward you at warp speed.

ACT II: 2006: Abandoned Home

Standing on the balcony of a rented townhouse, overlooking a black-topped parking lot in Syracuse, New York, I stared blankly at the white geraniums and variegated ivy plants I’d planted in three, green plastic flower pots. How in the hell had I ended up in this place? I pushed an exposed root deeper into the dirt and wondered what happens to our past visions. The kids were now at their respective universities, friends and family were happy to see me 'stateside,' but I wasn’t so sure. There had been no time to assimilate, make concrete plans, or weigh the options of leaving Europe. It had happened quickly—I’d been a healthy, thriving plant and was yanked out of the ground and thrown onto a musky compost heap amidst other debris. One morning, I was married and by that evening I was separated from my husband of twenty five years.

A year later the contents of the rented Belgian house and our French home were packed into an enormous truck and before I knew it, I was on a plane bound for the US with my worried teenagers and two freaked out cats.“Everything will be fine. Don’t worry; we will be fine,” I told them, but I didn’t believe my thin words. I had no choice—I was now mother and father to two children who hadknown HOME for thirteen years. As Brussels became a tiny spot thousands of feet below, I wondered if my husband, who’d remained behind, would come to his senses. My throat threatened to choke my shallow breaths and I prayed. Hard.

Another errant root pushed back into the soil, I watched the neighbor park his car, and struggled to remember the garden in Provence with the lavender-lined walkway, and how sweet the morning air smelled when I pushed open the blue shutters of our bedroom. It would be time to cut back the lavender and rosemary soon, but I knew the house and grounds sat abandoned. An abandoned home. I realized how close to the edge I was; how close I felt to losing myself, so I chose anger because it was always safer than sadness. No one would know of my secret pain, but I dreamed of France—the palm trees in front of my daughter’s bedroom, the kitchen counters and sink hewn in the same stone as the custom-made, floor to ceiling fireplace. Memories of picking plums, nectarines, figs, and peaches in the orchard to the right of the in-ground pool with the stone surround that Thierry, the maçon had lovingly installed using old tools so the house would appear older than it was. I remembered night swims with the deafening sound of the cicadas’ songs around me. Let it go, I told myself as tears stung my eyes.

One should never grow attached and accustomed to HOME. One couldn’t trust it. If I hadn’t loved my home so much, this sickening, intense homesickness and the stabbing pains in my heart at having realized a life dream only to lose it, would subside. I didn’t miss my husband; I missed my home, my life overseas. Never again would I be attached to home. This, I told myself.

ACT III: 2011 to Present Day - Fear and Freedom.

Despite repeated, tiring attempts of pushing the idea of home out of my head in the weeks and months after my divorce, I unpacked dishes, a few of my mother's knickknacks, photographs of my children, but I vowed never to unpack my writing journals or family photo albums from 1994 to 2006. Forget about watching films and reading books set in France, especially Provence; that life was over. A good friend advised me to think of my time in Europe as a goal achieved rather than a vanquished dream. I agreed but told my friend to convince my heart; it wouldn’t listen to logic.

Once again, my roots were thin, delicate, shallow, just beneath the surface as I roamed from New York to Maryland to Virginia, trying to find a place to call home. Hell, not even home; a couple of years in one place so my children had a home to return to during summer and holiday breaks from university would have been nice. Instead, a year here, two there, and I divorced, but with every move, I was closer in distance to my beloved children who lived in Virginia. When the French house was bought by a French lawyer, a single woman with no children, I cried for days.

No more soul mates; only endless first dates, job interviews, and the same dull DC conversations of the high cost of living, the Redskins, and the ridiculous traffic—stories I’d heard in 1994 when we left for Belgium. I nodded politely at the man, my dinner date. He insisted I select a bottle of wine for our dinner. I decided on a bottle of Saint Emilion I could no longer afford, but he was buying, and I slowly sipped the blood red nectar until I began to feel myself uncoil. As he spoke about his football glory days, I remembered a beautiful evening in France feasting on oysters, a tagine of lamb, couscous, and grilled vegetables. Suddenly, the harsh words of my expensive divorce lawyer rang in my ear, “Most women never recover from divorce because they refuse to change the lifestyle they led as married women. They end up in one bedroom apartments with no money in the bank. Be smart.” What did he know? Jerk.

Four years later, it was the same routine—work, home, dinners out, work, home, dinners out. The idea of home seeped into my consciousness once again. I felt more settled, but not settled enough. My children graduated from college, found good jobs, and my work, though rewarding, didn’t feed my soul. I longed to paint and write again. Why not? That’s what I loved, that was my life’s passion, but how could I make that happen? I pulled out a map, tied a string to a straight pin and taped a pencil to the end of the string. I inserted the straight pin into the map, in the city where I stood and drew a circle. I would search for an available home within the circle, which would be two hours from my kids. West Virginia. According to the young man at the bank, that was where I could afford to buy a house. My pain-in-the-ass lawyer had been right.

All signs pointed to West Virginia, where I knew one person, a good friend. I didn’t hesitate. In three months time, I’d quit my job, bought an historic house with good bones—not my forever home, but a soft place to land and rebuild my life. My kids with their busy lives and my family visited me in the new, old home for family holidays and weekend visits. I was happy again.

Sitting in a French country armchair in front of an oak table bought at a Brussels flea market, amidst family photos in old silver frames, French and Dutch oil paintings on the walls, with my memories and thoughts of family roots and home, I finished that novel. And then my son moved to the Netherlands just like I’d always known he would, in search of home.

Puerto Rican-born novelist and painter, Eleanor Parker Sapia was raised in the United States, Puerto Rico, and Europe. Her passion for travel and adventure, combined with her careers as a counselor, alternative health practitioner, and a Spanish language social worker and refugee case worker inspire her writing. She loves introducing readers to Latina characters and stories. When Eleanor is not writing, she enjoys facilitating The Artist’s Waycreativity groups, and has taught creative writing to children and adults. Eleanor shares her passion for telling stories at her blog,

The Writing Life

and her website, http://www.eleanorparkersapia.com

Puerto Rican-born novelist and painter, Eleanor Parker Sapia was raised in the United States, Puerto Rico, and Europe. Her passion for travel and adventure, combined with her careers as a counselor, alternative health practitioner, and a Spanish language social worker and refugee case worker inspire her writing. She loves introducing readers to Latina characters and stories. When Eleanor is not writing, she enjoys facilitating The Artist’s Waycreativity groups, and has taught creative writing to children and adults. Eleanor shares her passion for telling stories at her blog,

The Writing Life

and her website, http://www.eleanorparkersapia.com A Decent Woman, Eleanor’s debut historical novel, has garnered rave reviews and currently sits on several Amazon best seller lists for Hispanic, Latin American, and Caribbean Literature. She has two adult children and currently

Published on April 16, 2015 07:14

April 14, 2015

Finding Home: First Apartment to Homeless Wandering

This is the twelfth post in a blog series called Finding Home, a serialized mini-memoir exploring my search for a place to call home. Like the characters in The Alki Trilogywho struggle to find a place of belonging, I spent far too many years doing the same.

After two years at a private Catholic university, I wanted something bigger, something I thought of as more real, more radical, more a reflection of the chaos of the mid 1970s. I wanted the University of Washington, and I wanted my own apartment. Or, I thought I did. Before the loneliness became unbearable and I questioned the meaning and purpose of life itself. I was also in love for the first time. And sex? Let's just say those Jesuit professors would've disapproved of what was going on every night within the sacred walls of an impressive number of those dormitory rooms.

I rented a studio apartment in a three-story brownstone one block from the University of Washington campus and one block from The Last Exit on Brooklyn, the coffee shop I memorialized in Running Secrets. I sat for hours watching chess games and eaves-dropping on the political rants of the hippie intellectuals until the cigarette smoke burned my eyes and my loneliness within a crowd became worse than the loneliness of being alone. Now, forty years later, the brownstone and The Last Exit are only whispers of memory.

For six months I lived in a spacious studio with a small kitchen. The kitchen had etched glass French doors, and there was a large walk-in closet complete with a fold-down Murphy bed. Large trees stood just outside my third floor windows. I loved the place. I felt all Marlo Thomas in That Girl,but I didn't have her boyfriend or her financial security or her friends. My love was lopsided - boyfriend continued his English language studies at the university I had chosen to leave. My part-time jobs barely covered tuition and rent . Friendship was something I still struggled to understand. I didn't know how to get a Marlo Thomas life, how to build a support system where none existed, how to bear the self-imposed isolation.

For six months I lived in a spacious studio with a small kitchen. The kitchen had etched glass French doors, and there was a large walk-in closet complete with a fold-down Murphy bed. Large trees stood just outside my third floor windows. I loved the place. I felt all Marlo Thomas in That Girl,but I didn't have her boyfriend or her financial security or her friends. My love was lopsided - boyfriend continued his English language studies at the university I had chosen to leave. My part-time jobs barely covered tuition and rent . Friendship was something I still struggled to understand. I didn't know how to get a Marlo Thomas life, how to build a support system where none existed, how to bear the self-imposed isolation.

Despite my initial infatuation with my first apartment, it definitely was not home. When my lease was up, I bought a month-long Greyhound bus pass and set off to see the country. Alone. The boyfriend was Venezuelan and on a government scholarship. He was waiting to see where Caracas would send him to earn his degree. I was ready to follow him to the end of the world. If only he'd ask.

Despite my initial infatuation with my first apartment, it definitely was not home. When my lease was up, I bought a month-long Greyhound bus pass and set off to see the country. Alone. The boyfriend was Venezuelan and on a government scholarship. He was waiting to see where Caracas would send him to earn his degree. I was ready to follow him to the end of the world. If only he'd ask. After a month of travels, I found myself homeless and still waiting. My parents' home was about forty-five minutes from Seattle, but without a car it might as well have been across the country. Besides, I had no intention of returning to the hide-a-bed in the living room. Instead I returned to the dormitory that still housed the English language school and the boyfriend. I knew the building well after having lived and worked there for almost two years before transferring to the University of Washington. I knew who worked where and when. I knew which showers on which floors I could sneak into. And I knew there was a full-sized bench sofa in the women's restroom in the lobby.

Don't want to miss a single post? Get them delivered by entering your email in the box in the lower right To read the prior posts in this series, go to the posts listing in the left side bar. If no longer visible, just click on "March."

Published on April 14, 2015 06:21

April 9, 2015

Finding Home: Other Voices

Today author Tess Thompson shares her story of finding home and what it means to her. Enjoy!

Wild and Unruly

“I said I wanna touch the earth

I wanna break it in my hands

I wanna grow something wild and unruly” Dixie Chicks, “Cowboy Take Me Away” I am a child. Where I live we worship the moon and stars, the green river that meanders through the mountains, trees that rustle in the breeze, and the sweet scent of flowers. We know the difference between pines and cedars and firs and that lighter green needles indicate the year’s growth. Stargazers, buttercups, and rhododendrons grow wild alongside country roads and their dabs of color are deemed a small miracle. During springtime we celebrate the blooming lilacs and Dogwood trees and the first morning of the year we wake to the sound of chirping birds. In the valley where our town dwells, humble and haggard, boasting of one stoplight and a Dairy Queen, we know one another by name. We’re polite to adults because they are our friend’s parent, or our teacher, or our neighbor that grows tomatoes so juicy we eat them warm from the garden like apples as juice runs down our chins, or the librarian who always knows just the right book to send us home with. We love because we’re loved.

We run in packs of young people. I have my pack. They’re like home. We were birthed from the earth and the expansive sky. We’re daughters of schoolteachers and hippies and furniture makers. Smart girls. Readers. Students. Nice girls, except for our wild and unruly hearts that yearn for adventure and love and cannot to be tamed. On August afternoons, my last August, we gather at the river and swim deep, down to the rocks that host a crawfish, and when we emerge the sun dries our skin and the backs of our legs turn pink from the hot rocks that jut out of the water as our feet dangle into the cool green. If we’re still, minnows will nibble our toes under a sky so blue its beauty almost hurts. When night comes we spend hours looking up because the stars seem close enough to touch. And there are falling stars in August. Everywhere. We wait but a moment before one darts across the sky, and then another, and another. Under us, the rocks are still warm from the sun.

We are young and full of dreams. My heart is big and pulses with love for these friends that are my home and for the dry air that brings the smell of the flowers no one can name and for the community that keeps watch over their young. But the air whispers of change; I cannot hear it just then. I am a star shooting across the sky. Nothing can deter me from this hope, this anticipation for my life to come. It is the last time I am ever young.

Our gaggle of girls scattered like the seeds of our beloved flowers to all ends of the earth because we had to grow up, had to leave our little Oregon town and make our way in the world. One day I’m watching the ever-changing hue of the mountains and the next I’m in the place where I am to chase dreams instead of stars.

In this new home, the mountains are brown, the sky a hazy orange. At night the sound of helicopters flying overhead never ceases, penetrated only by an occasional gunshot. The sidewalks smell of urine and stale beer. Graffiti mars every building. People hate one another here. They hate one another and they hate the college students that live in their midst. Our privilege must feel like mockery, I imagine, the ugliness of their surroundings like jail. There are no trees, no flowers. Birds do not call to one another. Homes have bars across the windows. There is this foreboding, this just suppressed violence that feels like a room filled with gas just before someone lights a match.

For the first time in my life, I am afraid. I learn to keep my eyes averted, to walk fast, to carry mace. Only when I reach the gates of campus do I breathe easily even though I dare not look behind me. Here, on campus, the lawns are manicured. Old trees and brick buildings. Thirteen libraries. Paths zigzag around the buildings, teeming with privileged college students too young to understand how luck brought us to one place and not the other. Across the street is America’s failure. No one speaks of it, this poverty that brings crime and gangs and fear. No one wants to see it, to take responsibility for it, and so hate grows. Later, after Rodney King, the match is lit and the streets burn. Every building across from our campus will be obliterated when hate explodes.

And yet, in this new place, my new home, I find another gaggle of girlfriends. They’re not from the land of sky and river but of places I know only from the map. We bond because we’re displaced from our homes and because we’re creative with big dreams and because we’re wild and unruly and cannot be tamed. One of us is a Jersey girl that attended a Catholic school for girls and I never tire of hearing stories of the nuns and uniforms and what it was like to study without the distraction of boys. Amazed I do not know, she teaches me how to make a cross over my chest. Another is the daughter of a Marin County doctor – she has a nose ring and tells stories of her boyfriend that plays in a band. The other is a valley girl – not my valley with acres of hayfields, but the California variety where her parents are friends with famous people. Sometimes she drives us all to the beach in her convertible, our big eighties hair blowing in the wind. Often we marvel at the hue of the sky over our campus, trying to give it a name, a color, but are baffled. Other times we drink too much beer at theatre school parties. We share secrets we agree never to tell another soul. We perform in a play where we wear corsets. We cry over boys that do not like us. We grow up a little at a time, together. I learn that I love the smell of the ocean as much as the river. I am no longer a falling star but a wave. I’ve made a new home.

So it goes, all my life. Gaggles of wild and unruly girlfriends that make anyplace I’ve lived a home, despite the color of the sky or the weather or even my changing dreams. Home is where your people are. Home is where love lives. And each time I’ve had to venture further out into the world, seeking a new home or rebuilding the one that crumbled, as I’ve had to do recently, they remain in my wild and unruly heart no matter the miles between us. But I think, too, that my first home of earth and sky - where an entire community loved me - taught me how to love in the deep way I do. Hate is taught. And so is love. I love because I was loved. I love because I’m loved.

Tess Thompson is the bestselling author of romantic suspense, including the River Valley Collection. Her first historical fiction, Duet for Three Hands , was released in the February 2015. She grew up in a small town in southern Oregon before moving to south central Los Angeles to study theatre at the University of Southern California. Currently, she lives in a suburb of Seattle with two cats and two daughters. Visit Tess Inspiration for Ordinary Life.

Wild and Unruly

“I said I wanna touch the earth

I wanna break it in my hands

I wanna grow something wild and unruly” Dixie Chicks, “Cowboy Take Me Away” I am a child. Where I live we worship the moon and stars, the green river that meanders through the mountains, trees that rustle in the breeze, and the sweet scent of flowers. We know the difference between pines and cedars and firs and that lighter green needles indicate the year’s growth. Stargazers, buttercups, and rhododendrons grow wild alongside country roads and their dabs of color are deemed a small miracle. During springtime we celebrate the blooming lilacs and Dogwood trees and the first morning of the year we wake to the sound of chirping birds. In the valley where our town dwells, humble and haggard, boasting of one stoplight and a Dairy Queen, we know one another by name. We’re polite to adults because they are our friend’s parent, or our teacher, or our neighbor that grows tomatoes so juicy we eat them warm from the garden like apples as juice runs down our chins, or the librarian who always knows just the right book to send us home with. We love because we’re loved.

We run in packs of young people. I have my pack. They’re like home. We were birthed from the earth and the expansive sky. We’re daughters of schoolteachers and hippies and furniture makers. Smart girls. Readers. Students. Nice girls, except for our wild and unruly hearts that yearn for adventure and love and cannot to be tamed. On August afternoons, my last August, we gather at the river and swim deep, down to the rocks that host a crawfish, and when we emerge the sun dries our skin and the backs of our legs turn pink from the hot rocks that jut out of the water as our feet dangle into the cool green. If we’re still, minnows will nibble our toes under a sky so blue its beauty almost hurts. When night comes we spend hours looking up because the stars seem close enough to touch. And there are falling stars in August. Everywhere. We wait but a moment before one darts across the sky, and then another, and another. Under us, the rocks are still warm from the sun.

We are young and full of dreams. My heart is big and pulses with love for these friends that are my home and for the dry air that brings the smell of the flowers no one can name and for the community that keeps watch over their young. But the air whispers of change; I cannot hear it just then. I am a star shooting across the sky. Nothing can deter me from this hope, this anticipation for my life to come. It is the last time I am ever young.

Our gaggle of girls scattered like the seeds of our beloved flowers to all ends of the earth because we had to grow up, had to leave our little Oregon town and make our way in the world. One day I’m watching the ever-changing hue of the mountains and the next I’m in the place where I am to chase dreams instead of stars.

In this new home, the mountains are brown, the sky a hazy orange. At night the sound of helicopters flying overhead never ceases, penetrated only by an occasional gunshot. The sidewalks smell of urine and stale beer. Graffiti mars every building. People hate one another here. They hate one another and they hate the college students that live in their midst. Our privilege must feel like mockery, I imagine, the ugliness of their surroundings like jail. There are no trees, no flowers. Birds do not call to one another. Homes have bars across the windows. There is this foreboding, this just suppressed violence that feels like a room filled with gas just before someone lights a match.

For the first time in my life, I am afraid. I learn to keep my eyes averted, to walk fast, to carry mace. Only when I reach the gates of campus do I breathe easily even though I dare not look behind me. Here, on campus, the lawns are manicured. Old trees and brick buildings. Thirteen libraries. Paths zigzag around the buildings, teeming with privileged college students too young to understand how luck brought us to one place and not the other. Across the street is America’s failure. No one speaks of it, this poverty that brings crime and gangs and fear. No one wants to see it, to take responsibility for it, and so hate grows. Later, after Rodney King, the match is lit and the streets burn. Every building across from our campus will be obliterated when hate explodes.

And yet, in this new place, my new home, I find another gaggle of girlfriends. They’re not from the land of sky and river but of places I know only from the map. We bond because we’re displaced from our homes and because we’re creative with big dreams and because we’re wild and unruly and cannot be tamed. One of us is a Jersey girl that attended a Catholic school for girls and I never tire of hearing stories of the nuns and uniforms and what it was like to study without the distraction of boys. Amazed I do not know, she teaches me how to make a cross over my chest. Another is the daughter of a Marin County doctor – she has a nose ring and tells stories of her boyfriend that plays in a band. The other is a valley girl – not my valley with acres of hayfields, but the California variety where her parents are friends with famous people. Sometimes she drives us all to the beach in her convertible, our big eighties hair blowing in the wind. Often we marvel at the hue of the sky over our campus, trying to give it a name, a color, but are baffled. Other times we drink too much beer at theatre school parties. We share secrets we agree never to tell another soul. We perform in a play where we wear corsets. We cry over boys that do not like us. We grow up a little at a time, together. I learn that I love the smell of the ocean as much as the river. I am no longer a falling star but a wave. I’ve made a new home.

So it goes, all my life. Gaggles of wild and unruly girlfriends that make anyplace I’ve lived a home, despite the color of the sky or the weather or even my changing dreams. Home is where your people are. Home is where love lives. And each time I’ve had to venture further out into the world, seeking a new home or rebuilding the one that crumbled, as I’ve had to do recently, they remain in my wild and unruly heart no matter the miles between us. But I think, too, that my first home of earth and sky - where an entire community loved me - taught me how to love in the deep way I do. Hate is taught. And so is love. I love because I was loved. I love because I’m loved.

Tess Thompson is the bestselling author of romantic suspense, including the River Valley Collection. Her first historical fiction, Duet for Three Hands , was released in the February 2015. She grew up in a small town in southern Oregon before moving to south central Los Angeles to study theatre at the University of Southern California. Currently, she lives in a suburb of Seattle with two cats and two daughters. Visit Tess Inspiration for Ordinary Life.

Published on April 09, 2015 06:52

April 7, 2015

Finding Home: College Dorms

After a year on the living room hide-a-bed,I was ready to leave home. What I wasn't ready for was a tight dorm room with three other girls and a bathroom down the hall. Despite coming from a large family, life on fifteen acres of undeveloped land allowed for loads of personal space. I felt simultaneously suffocated and lost in my first dorm room on an upper floor of a tall, concrete block building. And let's admit it, I was painfully awkward. Making friends was terror. I wanted escape. I needed space and quiet. It was 1972. Despite overcrowding, freshmen were required to live on campus. Still, by the end of my first quarter I was searching for alternatives.

There were two other dorm buildings on campus at my small Jesuit university. The first the was male equivalent of my dorm; the second housed an odd assortment including an English language school (both classrooms and dorms), deaf students attending a neighboring community college, and upper class university students - male only. I wanted one of those rooms.

I climbed the ladder of university authority getting increasingly abrupt refusals. That's when I made an appointment with the director of the English language school who was more than happy to rent me a room. I suppose he figured having a native speaker living amongst his international students could be good for marketing. I moved into a private room mid-freshman year.

My mistake was in telling any of my classmates where I lived. Somehow word reached a campus reporter, and the next thing I knew I was back in the director's office. The university had threatened to terminate the language school lease if they continued to rent to me. Fortunately, the director saw the absurdity of keeping empty dorms at an overcrowded urban university, and he found the perfect solution: he offered me a job. I lived rent-free as a Resident Assistant for the remainder of my two year stint at that university.

My strongest memory? The screams. I remember a week of dreadful, bloodcurdling screams. It was before my official role as Resident Assistant had begun. I was still an anonymous American co-ed living in a single room on a floor of tiny dorm rooms full of international students from around the world. Some came for a few months of English before extended travels around the United States. Others had plans to enter American universities. And still others were part of the first wave of Vietnamese refugees, those with sufficient funds or connections to the United States military, who managed to escape before the fall of Saigon in 1975.

She was a young Vietnamese woman, so petite at first glance I thought she was a child. Only after years of working with refugees and immigrants did I comprehend the horror behind those endless nights of screaming and crying. I offered nothing more than a passing smile in the long hallway. Then, she disappeared.

The year and a half I spent in that world of international students and ESL instruction opened my eyes to a new reality. I continued attending classes but no longer worried about fitting into the private Catholic university scene that felt more alien to me than the worlds of my new floor-mates. But beyond the dorm and the insular campus, the Vietnam War continued to rage, the country was on fire, and I was ready to move on.

Don't want to miss a single post? Get them delivered by entering your email in the box in the lower right column.

To read the prior posts in this series, go to the posts listing in the left side bar. If no longer visible, just click on "March."

Published on April 07, 2015 06:41