Edoardo Albert's Blog, page 95

February 6, 2014

Rejection notes – no.23 in a series

Thanks very much for sending this story to [...]. Unfortunately, it’s not quite right for us. I really liked the setting and the sense of detail, and I felt an intriguing acuteness in Cavel’s tone and situation, but the exposition on the background felt slow of pace to me after the first couple paragraphs, and I didn’t feel as much of an acuteness or urgency develop in Cavel’s situation as I needed for the story to continue to hold my interest.

We appreciate your interest in our magazine. Please feel free to submit other work in the future.

Regards,

TV is evil – part 2

With thanks to Ronnie Haydon for pointing this out to me. The just as great Roald Dahl on the effects of TV.

Television

The most important thing we’ve learned,

So far as children are concerned,

Is never, NEVER, NEVER let

Them near your television set –

Or better still, just don’t install

The idiotic thing at all.

In almost every house we’ve been,

We’ve watched them gaping at the screen.

They loll and slop and lounge about,

And stare until their eyes pop out.

(Last week in someone’s place we saw

A dozen eyeballs on the floor.)

They sit and stare and stare and sit

Until they’re hypnotised by it,

Until they’re absolutely drunk

With all that shocking ghastly junk.

Oh yes, we know it keeps them still,

They don’t climb out the window sill,

They never fight or kick or punch,

They leave you free to cook the lunch

And wash the dishes in the sink –

But did you ever stop to think,

To wonder just exactly what

This does to your beloved tot?

IT ROTS THE SENSE IN THE HEAD!

IT KILLS IMAGINATION DEAD!

IT CLOGS AND CLUTTERS UP THE MIND!

IT MAKES A CHILD SO DULL AND BLIND

HE CAN NO LONGER UNDERSTAND

A FANTASY, A FAIRYLAND!

HIS BRAIN BECOMES AS SOFT AS CHEESE!

HIS POWERS OF THINKING RUST AND FREEZE!

HE CANNOT THINK — HE ONLY SEES!

‘All right!’ you’ll cry. ‘All right!’ you’ll say,

‘But if we take the set away,

What shall we do to entertain

Our darling children? Please explain!’

We’ll answer this by asking you,

‘What used the darling ones to do?

‘How used they keep themselves contented

Before this monster was invented?’

Have you forgotten? Don’t you know?

We’ll say it very loud and slow:

THEY … USED … TO … READ! They’d READ and READ,

AND READ and READ, and then proceed

To READ some more. Great Scott! Gadzooks!

One half their lives was reading books!

The nursery shelves held books galore!

Books cluttered up the nursery floor!

And in the bedroom, by the bed,

More books were waiting to be read!

Such wondrous, fine, fantastic tales

Of dragons, gypsies, queens, and whales

And treasure isles, and distant shores

Where smugglers rowed with muffled oars,

And pirates wearing purple pants,

And sailing ships and elephants,

And cannibals crouching ’round the pot,

Stirring away at something hot.

(It smells so good, what can it be?

Good gracious, it’s Penelope.)

The younger ones had Beatrix Potter

With Mr. Tod, the dirty rotter,

And Squirrel Nutkin, Pigling Bland,

And Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle and-

Just How The Camel Got His Hump,

And How the Monkey Lost His Rump,

And Mr. Toad, and bless my soul,

There’s Mr. Rat and Mr. Mole-

Oh, books, what books they used to know,

Those children living long ago!

So please, oh please, we beg, we pray,

Go throw your TV set away,

And in its place you can install

A lovely bookshelf on the wall.

Then fill the shelves with lots of books,

Ignoring all the dirty looks,

The screams and yells, the bites and kicks,

And children hitting you with sticks-

Fear not, because we promise you

That, in about a week or two

Of having nothing else to do,

They’ll now begin to feel the need

Of having something to read.

And once they start — oh boy, oh boy!

You watch the slowly growing joy

That fills their hearts. They’ll grow so keen

They’ll wonder what they’d ever seen

In that ridiculous machine,

That nauseating, foul, unclean,

Repulsive television screen!

And later, each and every kid

Will love you more for what you did.

Roald Dahl

TV is evil

The great Theodore Dalrymple on the evil screen in the corner. I spent many years repairing televisions, and this is one of the reasons why, when broadcasts went digital, we did not follow. There were too many houses I visited were the TV was the first thing switched on in the morning and the last thing switched off at night – and in some households, it was never turned off, but remained, on mute, a flickering presence through the night. Our TV, analogue and out of date, allows us to watch DVDs, but we are not drawn into the passivity of channel hopping and slack-jawed staring at a screen. If further evidence is required, here is the good doctor on the people who make TV programmes.

To my shame, and against my principles, I have occasionally agreed to appear on television, though even less frequently than I have been asked. I have found those who work for TV broadcasting companies to be the most disagreeable people that I have ever encountered. I far preferred the criminals whom I encountered in my work as a prison doctor, who were more honest and upright than TV people.

In my experience, TV people are as lying, insincere, obsequious, unscrupulous, fickle, exploitative, shallow, cynical, untrustworthy, treacherous, dishonest, mercenary, low, and untruthful a group of people as is to be found on the face of this Earth. They make the average Western politician seem like a moral giant. By comparison with them, Mr. Madoff was a model of probity and Iago was Othello’s best friend. I am prepared to admit that there may be—even are—exceptions, as there are exceptions good or bad in every human group, but there is something about the evil little screen that would sully a saint and sanctify a monster.

Turn off, tune out, drop completely.

February 3, 2014

Rejection notes – no.22 in a series

Dear Edoardo,

Thank you for letting me see “The Long Death.” The story is moving and thoughtful, but I’m afraid it’s not quite right for me. I look forward to your next one, though.

All best

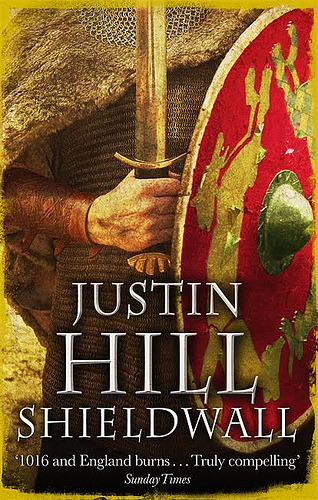

Justin Hill’s read my book!

This just gets better and better! After the wonderful message from Bernard Cornwell on Friday, my editor received an email from Justin Hill, author of Shieldwall (only the best novel about Anglo-Saxon England out there) this morning. He’s read Edwin: High King of Britain as well and he likes it too!

Justin Hill

So, here’s what Justin (we’re on first name terms now, you see!) has to say about Edwin:

‘At the dawn of England seven kingdoms struggle for supremacy: but there is more than honour and power at stake; paganism, Christianity and the future shape of the English nation will be decided. A fast-paced and gripping tale of the great Northumbrian King Edwin, reclaiming one of our great national figures from the shadows of history.’

I am, I must admit, feeling slightly overwhelmed at the moment, but in a good way! By the way, if you’ve never read Shieldwall, I can’t recommend it enough. Here’s my review of it.

Shieldwall

February 2, 2014

Constantine the Great

It’s rare for an emperor to earn the title ‘the great’. It’s even rarer for that same emperor to also be called a saint. So with Constantine I we’re dealing with no ordinary man. Now, while Constantine’s right to be called a saint is disputable – saints not being generally known for executing both son and wife – what is not open to question is that he was the greatest emperor of the late Roman Empire.

Bust of Constantine.

What’s more extraordinary is that Constantine came from, on his mother’s side, such humble stock. The Empress Helena was probably a tavern maid when she met an ambitious soldier called Constantius. Whether they ever married is not known for certain but we do know that this tavern maid left her home town of Drepanum in Asia Minor and accompanied Constantius on his campaigns, bearing him a son c.272AD. Constantius’s career took him virtually to the top of the military and imperial tree, culminating with the command of the provinces of Gaul, Britain and Spain. And there alongside him was his son, Constantine. But on 25 July 306 Constantius died at Eburacum (York), while campaigning against the Picts, and the legions acclaimed his son their Augustus.

At this time the Empire was ruled by four emperors, two in the west and two in the east, so Constantine was by no means the only man aspiring to the purple. However, there were more than four pretenders to the thrones, but illness and intrigue soon whittled the field down to four, with Constantine and Maxentius left as Augusti of the west. Not, you’ll guess, the most stable of arrangements, since kings generally dislike sharing their crowns.

Sure enough, in 312 the dispute between the emperors of the west turned bloody, and Constantine crossed the Alps into Italy with a vastly outnumbered force of 40,000 men. Maxentius had Rome as his base but, rather than wait out Constantine, he came forth with some 100,000 men, prepared to do battle at the Milvian Bridge over the River Tiber, north of Rome.

On the night before the battle, according to one source, Constantine had a dream commanding him to place the sign of Christ on his soldiers’ shields. Another historian says that there was a vision of a cross of light in the sky, with the words ‘by this, conquer’. Whichever account is true, we know that on 28 October 312 the armies of Constantine and Maxentius met in battle, and that Maxentius’s forces were utterly defeated and the former Augustus drowned while trying to escape back south across the river.

Constantine was now the undisputed emperor of the western Roman Empire. Meanwhile Licinius, via the odd battle of his own, had become the sole ruler of the eastern Empire. One of the first acts of the two emperors was to issue, in February 313, the Edict of Milan. This instructed the governors of all Roman provinces to stop the persecution of Christians (which had been vigorous under the previous emperors), to restore confiscated property to Christians, and to allow all citizens the freedom to practise whatever religion they wished

But history shows that it’s generally difficult to solve the equation of two emperors into one empire. Licinius reneged on the Edict and began a new persecution of the Empire’s Christian population. Three battles later, in 324, Constantine was the sole ruler of the Roman Empire, both east and west.

During the course of the war with Licinius Constantine had to lay siege to a city strategically sited on a promontory of the Bosporus. Whoever ruled the city was master over the sea traffic in and out of the Black Sea, as well as commanding a key position on the trade routes both north-south and east-west. If any one place could claim to be the centre of the world this was it. And on 8 September 324, only weeks after his victory over Licinius, Constantine laid out the boundaries of his new city. On this site New Rome would rule an empire for a thousand years after the fall of Old Rome.

But what about being a saint? There’s that unfortunate business with Crispus, his illegitimate first son, and Fausta, Constantine’s wife and mother of his later children to deal with. In 326 Constantine executed Crispus and then, not long after, the emperor had his wife, Fausta, killed too (reputedly by having her put in an overheated bath). Why did he kill two people so close to him? It is impossible to know for sure now, but perhaps the most plausible suggestion is that Fausta, wanting to ensure that her own sons succeeded to the throne, accused Crispus of attempting to seduce or rape her. Constantine, who was not known for calm forbearance, flew into a rage and executed his son. Then, when he found out that his wife had lied to him, he killed her too.

So, perhaps not a saint. But Constantine the Great? Yes, certainly.

January 31, 2014

Bernard Cornwell’s read my book!

Yes, that Bernard Cornwell, author of the Sharpe books (I’ve read 23 out of 24 of them, only excepting the one where Sharpe is cuckolded by his wife and falls out with William Frederickson, as I couldn’t bear to read it) and the Saxon War novels, and, now with Patrick O’Brian gone, probably the best and certainly the best-known writer of historical fiction in the world, that Bernard Cornwell – he’s read my book! My publisher, Lion Fiction, sent Bernard’s (we’re on first name terms now he’s endorsed my book!) agent a copy of Edwin: High King of Britain, but without any real hope of getting a reply – we had no ‘in’ with him, beyond the fact that he had once visited the Bamburgh Research Project. Then, to our astonishment, we received an email yesterday from the man himself. He’s read my book! He likes it!! He’s written a commendation for the cover!!! He’s given me even more reason to use exclamation marks!!!!!

So, when I say that I think the book is actually really rather good, I’ve now got Bernard Cornwell to back me up. Now, you want to know what he said, don’t you? Me, I kept re-reading it all yesterday. Well, here you go, this is what Bernard said, I’m sure it will have pride of place on the cover:

Edwin, High King of Britain, brings to life the heroic age of our distant past, a splendid novel that leaves the reader wanting more.

January 28, 2014

California Forming – the life of Junipero Serra

California is a state of contradictory perceptions: the golden land of opportunity on one hand, the diseased home of the tarnished American dream on the other. So it’s no surprise that Junipero Serra, the man who could be called the founder of California, should attract a similar range of views. But who was Junipero Serra and how did he earn such differing evaluations?

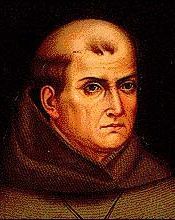

Junipero Serra

The facts are straightforward enough. He was born in 1713 in Majorca and entered the Franciscan order at the age of 16. For 20 years he followed the usual path for a bright Franciscan: study, ordination, teaching. If he had continued in that vein Serra would have merited no more than a footnote in obscure textbooks of theology. But the man wanted something more and, inspired by the missionary example of St Francis, set off to Mexico to…do more of the same for the next nine years. But a hint that that would not remain the case forever was given by the fact that he walked from the port all the way to Mexico City, some 200 miles. Another was his unusual practice, when preaching on repentance, of pulling his habit down from his shoulders and whipping himself. Apparently this was done not only to mortify himself but to encourage contrition in his congregation.

And sure enough, things did change for Serra. Spain, worried about a Russian claim on the Pacific coast (remember that at this time the Tsar still owned Alaska), wanted to establish priority in Alta (upper) California and to this end the governor agreed to fund missions there. Serra was placed in charge, setting off at the age of 56 and, 24,000 miles, nine new missions and 14 years later, he died at Mission San Carlos Borromeo. The missions he founded, including San Francisco de Asis (or Dolores), were linked by El Camino Real, a dirt road that eventually stretched some 600 miles, along the length of present-day California.

And here’s the controversy. Was Serra the ecclesiastical face of Spanish hegemony, pulling the free-spirited Native Americans of the coast into a life of stifling monastic discipline in the missions, the unwitting vector of the exotic diseases that killed thousands of natives and the general of the forces of cultural genocide? Or was he a man burning with an ideal of love that we find today hard to comprehend, a priest who continually fought with the secular authorities to protect the Indians and who offered up his life and labours for their salvation? The question seems inextricably bound up with our as yet unresolved questions about the nature of our own society, and because of that the legacy of Junipero Serra seems likely to remain uncertain for many years to come.

January 27, 2014

The First Iconoclasm

Individuals fall prey to illness, but the contagions that infect a civilisation are ideas. In the 8th and 9th centuries a Byzantine civilisation reeling before the onslaught of expansionist Islam was simultaneously torn apart by a controversy that might seem ridiculously abstruse from our vantage point: whether or not it was permissible to paint images of Christ and the saints. But to conclude that the Byzantines were wasting energy desperately needed for the defence of the empire is to make the mistake of judging them with the myopic gaze of the 21st century. Icons expressed the civilisational core of Byzantium, therefore their creation or destruction was vital to how New Rome saw itself.

Interior of an Orthodox church.

An icon (pace Bill Gates and sloppy journalists writing about mediacrities) is an image of Jesus, Mary, the saints or angels, generally painted on wood and richly coloured, often using gold leaf. Go into any Orthodox church today and the first thing that will strike you will be the glorious icons, glittering in the candlelight.

But in 726 the Emperor Leo III removed an image of Christ from above the doors to the imperial palace. Even that produced riots and deaths, for Byzantium saw itself as under the protection of Jesus. However, the emperor was not to be dissuaded and in 730 Leo took action, deposing the patriarch of Constantinople and ordering the removal or destruction of all icons from his city. All resistance was suppressed, violently. To judge how effective his policy was we simply have to note the almost complete lack of surviving icons from before the 8th century.

Why did Leo, on his own initiative, plunge his empire into what was virtually civil war, with the monasteries acting as an underground, hiding and protecting icons from the imperial troops? Part of the answer lies in the Byzantines’ struggle against Islam. As with their Muslim adversaries, the Byzantines saw success or failure as marks of God’s favour or disfavour. Thus their defeats by the aggressively iconoclastic Muslims lead some Byzantines to search for reasons why God had turned his face from them. They found a reason in the belief that the veneration of icons was idolatrous, in contravention to the second commandment forbidding graven images, and in the conclusion that since an icon only showed Christ’s human form it did violence to his nature as both fully human and fully divine.

Icons having been forbidden solely on imperial authority, Leo’s son and successor, Constantine V, decided to go for some ecclesiastical back up. He called a council of the church in 754, making sure that it consisted of bishops upon whom he could rely and notably excluding from the proceedings the Pope, and the Patriarchs of Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem. Sure enough, the meeting – later dubbed a robber council – duly rubber stamped the emperors’ actions.

However, the iconodules (those who venerate icons), were now mobilised. Their resistance centred on the monasteries and they found a spokesman in St John of Damascus, who though a Christian held the post of chief councillor to the Muslim Ummayad rulers of his city in Syria. Safely out of the emperor’s reach (or so he thought) John began to write in defence of icons, basing his case on the proposal that icons were not idols but rather depicted the sanctity of the figure portrayed as a reflection in a pool of water. He further pointed out that iconographers were only painting what God himself had done: become flesh and blood in the person of Christ. Therefore, to follow the iconoclasts’ logic, the first and greatest idolator was God himself.

The story goes that the emperor, unable to get at John directly, forged a letter purporting to show John offering to betray Damascus to the Byzantines. An unamused Caliph had John’s writing hand cut off.

The controversy continued for over a century, going through three more councils, each reversing the policy of the one previously, a number of emperors and two empresses. It was the women who decided matters in the end. The Empress Irene was the first to reverse the iconoclast policy of her predescessors, and in 843 the Empress Theodore proclaimed the restoration of icons. Since then the first Sunday of Lent has been celebrated as the feast of the triumph of Orthodoxy.

Who was right? It’s not for us to say. But go into an Orthodox church and look at the icons behind their flickering curtains of light. That glow you see. Is it a reflection, or an intimation of heaven?

January 25, 2014

Acceptance Notes – no.10 in a series

Hi, Edoardo–

Congratulations!

We’d be pleased to accept the story, “From Here to the Northern Line,” for inclusion in Third Flatiron Publishing’s spring 2014 anthology, with the working title, “Astronomical Odds.”

Please let us know if the story is still available.

We found the story about an autistic boy who spots Tube stations to the stars to be very entertaining.

We’d want the exclusive e-rights for six months. If this sounds good, please let me know, and I’ll get back with a contract. The anthology is scheduled for e-publication on March 15, 2014.