Anthony McIntyre's Blog, page 1201

July 14, 2017

Jobstown Innocent, Establishment Guilty

Details of a public meeting in Belfast to be hosted by

Labour Alternative.

Add caption

Add caption

Public Meeting

Jobstown Innocent, Establishment Guilty

7.30pm Monday 17th July, Queen's SU(Club rooms, third floor)

Guest speakers - Ruth Coppinger TD & Cllr Michael O'Brien, Solidarity

In Dublin, the first group of Jobstown defendants have been found not guilty of false imprisonment for taking part in a peaceful, anti-austerity protest which delayed then Deputy Prime Minister Joan Burton in her car for three hours. This is a huge blow to the Southern establishment, who threw everything at securing convictions in what was clearly a politically motivated witch-hunt to undermine the right to protest and cut across the left and movements of the 99%.

Come along to hear the details of the trial, including evidence of a police conspiracy, the impact the verdict has had and the campaign to have all charges against the remaining defendants dropped, as well as the growing movements for pay restoration and the right to choose in the South.

Hosted by Labour Alternative

Add caption

Add captionPublic Meeting

Jobstown Innocent, Establishment Guilty

7.30pm Monday 17th July, Queen's SU(Club rooms, third floor)

Guest speakers - Ruth Coppinger TD & Cllr Michael O'Brien, Solidarity

In Dublin, the first group of Jobstown defendants have been found not guilty of false imprisonment for taking part in a peaceful, anti-austerity protest which delayed then Deputy Prime Minister Joan Burton in her car for three hours. This is a huge blow to the Southern establishment, who threw everything at securing convictions in what was clearly a politically motivated witch-hunt to undermine the right to protest and cut across the left and movements of the 99%.

Come along to hear the details of the trial, including evidence of a police conspiracy, the impact the verdict has had and the campaign to have all charges against the remaining defendants dropped, as well as the growing movements for pay restoration and the right to choose in the South.

Hosted by Labour Alternative

Published on July 14, 2017 07:00

The New Wave

The

Uri Avnery Column

looks at a spreading challenge to establishment politics, which is international in its span.

The

Uri Avnery Column

looks at a spreading challenge to establishment politics, which is international in its span.When I was young, there was a joke: "There is no one like you – and that's a good thing!"The joke applies now to Donald Trump. He is unique. That's good, indeed.

But is he unique? As a world-wide phenomenon, or at least in the Western world, is he without parallel?

As a character, Trump is indeed unique. It is extremely difficult to imagine any other Western country electing somebody like that as its supreme leader. But beyond his particular personality, is Trump unique?

Before The US election, something happened in Britain. The Brexit vote.

The British people, one of the most reasonable on earth, voted democratically to leave the European Union.

That was not a reasonable decision. To be blunt, it was idiotic.

The European Union is one of the greatest inventions of mankind. After many centuries of internal warfare, including two world wars, with uncounted millions of casualties, good sense at long last prevailed. Europe became one. First economically, then, slowly, mentally and politically.

England, and later Britain, was involved in many of these wars. As a great naval power and a world-wide empire, it profited from them. Its traditional policy was to instigate conflicts and to support the weaker against the stronger.

These days are, alas, gone. The Empire (including Palestine) is but a memory. Britain is now a mid-ranking power, like Germany and France. It cannot stand alone. But it has decided to.

Why, for God's sake? No one knows for sure. Probably it was a passing mood. A fit of pique. A longing for the good old days, when Britannia ruled the waves and built Jerusalem in England's green and pleasant land. (Nothing very green and pleasant about the real Jerusalem.)

Many seem to believe that if there had been a second round, the British would have reversed themselves. But the British do not believe in second rounds.

Anyhow, The "Brexit" vote was considered a sharp turn to the Right. And right after, there was the American vote for Trump.

Trump is a Rightist. A very rightist Rightist. Between him and the right wall there is nothing, except, perhaps, his Vice. (Vice in both meanings of the word.)

Taken together, the British and the American votes seemed to portend a world-wide wave of rightist victories. In many countries, rightists and outright fascists were flexing their muscles, confident of success. Marine Le Pen was scenting victory, and her equivalents in many countries, from Holland to Hungary, hoped for the same.

History has known such political waves before. There was the wave started by Benito Mussolini after World War I, who took the old Roman fasces and transformed them into an international term. There was the Communist wave after World War II, which took over half the globe, from Berlin to Shanghai.

So now it was the great right-wing wave, that was about to submerge the world.

And then something quite different happened.

Nothing Seemed as stable as the political system of France, with its old established parties, led by a class of old experienced party hacks.

And there – lo and behold – appears a nobody, a practically unknown non-politician, who with a wave of the hand clears the entire chessboard. Socialists, fascists and everybody in between are swept to the floor.

The new man is Emmanuel Macron. (Emmanuel is a good Hebrew name, meaning "God with us".) He is very young for a president (39), very good looking, very inexperienced, except for a short stint as an economic minister. He is also a staunch supporter of the European Union.

A quirk, party functionaries comforted themselves. It will not last. But then came the French parliamentary elections, and the flood became a tsunami. An almost unprecedented result: already in the first round Macron's new party gained an astounding majority, which will surely grow in the second round.

Everybody Needed to think again. Macron was obviously the very opposite of the New Rightist Wave. Not only about European unity, but about almost everything else. A man of the center, he is more left than right. A modest person, compared to the American Trump. A progressive, compared to the British May.

Ah, Theresa May.

What got into her? Put in power after the Brexit vote, with a comfortable majority, she was restless. Seems she wanted to prove that she could get an even larger majority just by herself. These things happen to politicians. So she called for new elections.

Even poor me, with my limited experience, could have told her that this was a mistake. For some reason, people don't like untimely elections. It's like a curse of the Gods. You call, you lose.

May lost her majority. There was no obvious coalition partner in sight. So she is compelled to court the most obnoxious right wingers: the Northern Irish protestants, compared to whom Trump is a progressive: no rights for gays, no abortions, no nothing. Poor May.

Who was the big winner? The most unlikely of unlikely persons: Jeremy Corbyn, (Another one with a good Hebrew first name. Jeremy was a major Biblical prophet.)

Corbyn is as unlikely a near-winner as you get them: ultra-left, ultra-everything. Many members of his own party detest him. But he almost won the elections. In any case, he made it impossible for Theresa May to rule effectively.

Corbyn's achievement brings to mind again that something very similar happened in the US elections within the Democratic Party. While the official candidate Hillary Clinton aroused widespread antipathy in her own party, a most unlikely alternative candidate stirred a wave of admiration and enthusiasm: Bernie Sanders.

Not the most promising candidate: 78 years old, a senator for 10 years. Yet he was feted like a newcomer, a man half his age. If he had been the candidate of his party, there is little doubt that he would be President today. (Even poor Hillary got a majority of the popular vote.)

So Do all these victories and near-victories have something in common? Do they add up to a "wave"?

On first sight, no. Neither did the Left win (Trump, Brexit) nor did the right (Macron, Corbyn, Sanders).

So there is nothing in common?

Oh yes, there is. It is the rebellion against the establishment.

All these people who won, or almost won, had this in common: they smashed the established parties. Trump won despite the Republicans, Sanders fought against the Democratic establishment, Corbyn against the Labour bosses, Macron against all. The Brexit vote was, first of all, against the entire British establishment.

So that is the New Wave? Out with the establishment, whoever it is.

And In Israel?

We are not yet there. We are always late. The last national movement in Europe. The last new state. The last colonial empire. But we always get there in the end.

Half of Israel, almost the entire Left and Center, is clinically dead. The Labor party, which for 40 years held power almost single-handedly, is a sorry ruin. The right-wing, split into four competing parties, tries to impose a near-fascist agenda on all walks of life. I just hope that something will happen before their final success.

We need a principled leader like Corbyn or Sanders. A young and idealistic person like Macron. Somebody who will smash all the existing occupation-era parties and start right from the beginning.

To adapt Macron's slogan: Forward, Israel!

Published on July 14, 2017 01:00

July 13, 2017

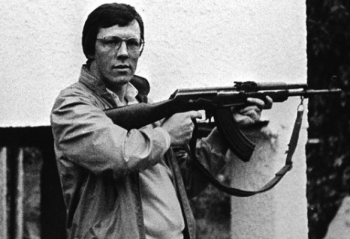

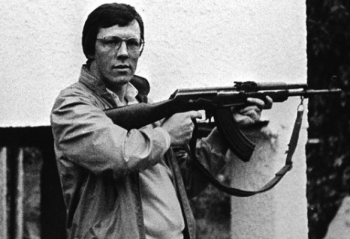

Outraging Grieving Relatives

Anthony McIntyre

featuring in the

Belfast Telegraph

writes that:

Birmingham Bombs: Interview Served No Purpose Other Than To Outrage Grieving RelativesI recall the Birmingham bombs well. As a seventeen year old IRA prisoner, it was a talking point in Crumlin Road jail. The year was ending pretty much as it had started for the IRA’s England campaign: bomb induced fatalities that reached double figures. If the M62 coach bombing was something the IRA could boast about because of the predominance of military personnel among the dead, there were to be no bragging rights in the wake of Birmingham. The slaughter was sans justification. What mitigation may have been cited was never going to make a dent in the public revulsion.

If I found it hard to comprehend then, my understanding has not been enhanced in the slightest by the “revelations” of Michael Hayes, interviewed for a BBC documentary on the bombings. Hayes was many years earlier “identified” as one of the men who planted a device on that fateful November evening in 1974. He has never admitted to it and his contribution to the BBC broadcast brought him no closer to an admission. His responses to the interviewer often seemed like the standard fare IRA posture when confronted by RUC interrogators. It is understandable why he might wish to feature in such a programme: to convey some semblance of remorse for an action he nevertheless refused to admit carrying out. It is much less understandable why the BBC should wish to put the camera on him when he said so little of consequence.

If the appearance in combat fatigues was designed to give an air of military authenticity to the attack, it failed lamentably, merely conjuring up memories from the time when the cartoon commanders of the UDA could appear in television studios in full military regalia, and masked to boot.

Sensationalism of this type might titillate some but it is hardly informative. The BBC managed to outrage the relatives of those killed in the blasts without adding anything substantive in terms of public knowledge.

It is evident Michael Hayes can throw greater light on the bombings than currently exists. But his contribution to the BBC broadcast was heat rather than light. He is unlikely to be forthcoming for understandable reasons. With the paralysis to truth recovery that is induced by a prosecutorial culture, encouraged more for recrimination than revelation, the chances for procuring a detailed account of what happened in Birmingham more than forty years ago recede to the point of neither heat nor light: only darkness.

Birmingham Bombs: Interview Served No Purpose Other Than To Outrage Grieving RelativesI recall the Birmingham bombs well. As a seventeen year old IRA prisoner, it was a talking point in Crumlin Road jail. The year was ending pretty much as it had started for the IRA’s England campaign: bomb induced fatalities that reached double figures. If the M62 coach bombing was something the IRA could boast about because of the predominance of military personnel among the dead, there were to be no bragging rights in the wake of Birmingham. The slaughter was sans justification. What mitigation may have been cited was never going to make a dent in the public revulsion.

If I found it hard to comprehend then, my understanding has not been enhanced in the slightest by the “revelations” of Michael Hayes, interviewed for a BBC documentary on the bombings. Hayes was many years earlier “identified” as one of the men who planted a device on that fateful November evening in 1974. He has never admitted to it and his contribution to the BBC broadcast brought him no closer to an admission. His responses to the interviewer often seemed like the standard fare IRA posture when confronted by RUC interrogators. It is understandable why he might wish to feature in such a programme: to convey some semblance of remorse for an action he nevertheless refused to admit carrying out. It is much less understandable why the BBC should wish to put the camera on him when he said so little of consequence.

If the appearance in combat fatigues was designed to give an air of military authenticity to the attack, it failed lamentably, merely conjuring up memories from the time when the cartoon commanders of the UDA could appear in television studios in full military regalia, and masked to boot.

Sensationalism of this type might titillate some but it is hardly informative. The BBC managed to outrage the relatives of those killed in the blasts without adding anything substantive in terms of public knowledge.

It is evident Michael Hayes can throw greater light on the bombings than currently exists. But his contribution to the BBC broadcast was heat rather than light. He is unlikely to be forthcoming for understandable reasons. With the paralysis to truth recovery that is induced by a prosecutorial culture, encouraged more for recrimination than revelation, the chances for procuring a detailed account of what happened in Birmingham more than forty years ago recede to the point of neither heat nor light: only darkness.

Published on July 13, 2017 13:00

European Reformations & Witch Hunts – Christian Misogyny & Religious Madness

Michael A. Sherlock

(Author) writes on how the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic-Counter Reformation encouraged witch hunting in Europe. TPQ republishes the piece with the author's permission.

Introduction

Prior to the thirteenth century, the Catholic Church’s position on witchcraft, as enunciated within the Canon Episcopi, was that it was a relatively harmless illusion, incapable of directly affecting natural phenomena.[1] Witchcraft was still, according to the widespread belief underpinning the Canon Episcopi, an evil offense worthy of admonition and exile, but the later belief, that it posed an immediate threat to natural phenomena, had yet to arise amongst the superstitious crowds of Christendom.[2] The former position was eventually overturned, and in the first few decades of the fourteenth century, largely as a result of Pope John XXII’s issuance of his Super Illius Specula, which authorized the Inquisition to vigorously prosecute witches [3] – witches, predominantly female,[4] were hunted down, beheaded, burned, drowned, strangled, and slaughtered in the thousands.[5] This barbarism aimed primarily against women reached a fever-pitch within the bloody Thirty Years War (1618-1648) between Catholic and Protestant Christians,[6] and it is estimated that by the end of this religious war, as many as half a million people had been executed on charges of witchcraft.[7]

This essay will briefly examine and discuss a number of ways in which both the Protestant Reformation (1517)[8] and the Catholic-Counter Reformation (1545-1648)[9] encouraged witch hunting in Europe. It will be argued that although these Reformations did contribute largely to the increase in both the severity and zeal with which witch hunts were conducted during these centuries, the primary culprits were religion and superstitious ignorance, just as they continue to co-conspire to commit the same atrocities in overtly religious and superstitious countries like modern Saudi Arabia.[10] It will be argued that the spike in witch hunts during the period in question can be accounted for by placing religion at the foundation of the examination, upon which various social, political and possibly even meteorological contributing factors may be seen as exacerbating influences.

Academic Approaches

Numerous scholars from a variety of academic fields have offered various explanations for the increased intensity of witch hunting from the fourteenth to the seventeenth centuries in Europe. Scholars such as Foucault (1961), Szasz (1970), and Senter (1947), for example, have produced a variety of hypotheses based upon a psychological-psychiatric model, arguing, variously, that this phenomenon can be explained by examining the mental states of the perpetrators and/or the victims. Trevor-Roper (1967), a scholar with one of the most eclectic approaches to the examination of witch hunting in Europe during these centuries, employs a scapegoat hypothesis, which holds that the predominantly female victims of witch hunts were mere scapegoats for the strife faced by Europeans during the period under examination. Other scholars (White, 1913; Thorndike, 1941; Rattansi, 1972; Ben, 1971; Hansen 1975) have argued that the increase in witch hunting can be explained by a superstitious and ignorant misunderstanding of a pre-scientific revolution, which saw some of the first modern attempts at chemistry and other sciences that appeared to a religious and credulous population as magical witchcraft. Further still, other scholars (Nelson, 1975; Currie, 1968; Shoeneman, 1977) have sought to put forth social, political and personal gain models, arguing that the ‘witch craze’ received so much attention that some saw it as a personally and politically profitable avenue for gain, thereby adding impetus to the already fervent persecution of women and men accused of witchcraft. Finally, a small handful of scholars, amongst whom are included Lewis (1971), Trevor-Roper (1967) and Nelson (1975), argue that the inferior status of women was a causal factor in the fervent witch hunts of early modern Europe.

There may be elements of truth in each of the approaches evinced above, as well as those omitted, but the answer may also lie in a more eclectic approach, one that incorporates not only the spur given to the witch hunts by both the Catholic and Protestant Reformations, but by all of the factors mentioned above, which, to varying degrees, may have watered the seeds of religious ignorance in a more general sense. Historian Keith Thomas concurs with this proposition, saying: ‘But religious beliefs as such were a necessary precondition of the prosecutions’.[11]

The Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation began in 1517 with Martin Luther nailing his Ninety-Five Theses on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Saxony.[12] One of the principle doctrines of Luther’s Reformation was Sola Scriptura (‘by scripture alone’), which held that the Bible was the sole and supreme authority on all matters pertaining to doctrine and practice.[13] This principle acted as a driving force which resulted in Bibles being printed in local vernaculars and as an eventual result, increased literacy rates across Europe.[14] This increase in literacy, coupled with the prior advent of the Gutenberg Printing Press in the 1450s,[15] meant that literature of all kinds could be widely disseminated across the European continent.[16] The proliferation of this new media technology meant that treatises which encouraged the hunting and prosecution of witches, such as Heinrich Kramer and James Sprenger’s Malleus Maleficarum (Eng. Hammer of the Witches), published in 1487,[17] were, for the first time, being widely published, and the increased propagation of such literature may have also contributed to the general belief amongst a relatively newly literate laity that witchcraft was becoming an increasingly widespread problem. This proposition ties in with the psychological-psychiatric model, for if such was in fact the case, then the influence of such media over the mentality of an already superstitious and fearful mass of believers would have probably been quite significant.

Luther’s German Translation of Exodus 22:18 – “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live”.

The majority of the victims of the witch hunts in Europe were women. According to Barstow: ‘women were overwhelmingly victimized: on average 80% of those accused and 85% of those killed were female’.[18]

It is no secret that the Bible itself is a wellspring of religious misogyny, from Genesis to Paul’s Epistles – but on top of the pre-existing misogyny that formed the foundation of such gender-focussed persecutions, Luther’s German translation of the Bible, specifically, his translation of Exodus 22:18, was probably another factor which contributed to the zealous witch hunts launched largely against women. The source of Luther’s translation is found amongst a textual tradition known to biblical scholars as the ‘Textus Receptus’, and this textual tradition forms the foundation of the King James Bible.[19] This dubious textual tradition, which, with regards to the Hebrew Bible, drew upon the Greek Septuagint,[20] translated the Hebrew noun כשף [21] (‘kashaph’ – Eng. ‘evil doer’/ ‘sorceress’? The precise meaning is unknown)[22] in Exodus 22:18 to ‘witch’/‘sorceress’ (Gk. ‘pharmakis’).[23] The King James Version of Exodus 22:18 was thus rendered: ‘Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live’.[24]

Luther, following the textual tradition that almost a century later would serve as the foundation of the King James Bible, translated the Hebrew ‘kashaph’ from the Greek ‘pharmakis’ into the German ‘zauberninnen’ (Eng. witches).[25] It is, therefore, reasonable to argue that the Luther’s German translation of ‘pharmakis’ into the local vernacular of the people was a protagonist in the largely female-focussed witch hunts of early modern Europe. If such happens to have been the case, then it goes some way to vindicating the hypothesis of scholars who have sought to attribute the inferior status of women as a causal factor in the witch hunts of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Europe. Add to this translation the newly contrived doctrine of ‘Sola Scriptura’, and the conditions would have been ripe for the persecution of witches, for the Bible, the perceived supreme authority of Christian doctrine and practice commanded such barbarism in the local vernacular of the people.

Heresy and Witches

The word ‘heresy’ stems from the Greek αἵρεσις (‘hairesis’),[26] and it originally connoted a self-chosen, or freely adopted opinion.[27] The meaning of the word was first co-opted and arguably perverted by early Christians.[28] From approximately the second century onward, heresy came to connote wrong belief, and within the exclusivist theology of the Christian religion, this was associated with concept that the Devil is a deceiver and causes people to fall prey to wrong beliefs, or heresies.[29]

The schismatic Reformations in Europe made heresy a prevalent and widely discussed issue, playing a pivotal role in the Thirty Years War.[30] That heresy came to the surface of the consciousness of Christians in Europe at this time is a matter of little dispute, and that witchcraft was branded heretical is also a fact supported by primary historical sources of the time – such as the aforementioned Malleus Maleficarum, an excerpt of which reads:

Further, Monter comments:

This association of witchcraft with heresy in Europe may have led to a rise in witch hunts due to the boiling accusations of heresy that were being launched at members of competing confessions of Christianity, and it may well be the case that “witches” were not so much a façade as Trevor-Roper has suggested,[33] but both, or either, an external social or internal psychological drive for consistency in an environment fuelled with a feverish religious zeal to prosecute and persecute “heretical enemies” of the “one true” confession of faith, whether they were Catholics, Protestants, or “witches”. It is of interest here to note that in areas unaffected by Protestantism, like Spain and Italy – that is to say – in areas unaffected by the heresy-focusing dissonance between Protestantism and Catholicism, witch hunts and trials were far less frequent.[34] To put it in simpler terms, the public obsession with heresy inspired by the split in Christendom could have inspired authorities and the public at large alike to strive for consistency by persecuting heresy wherever they found it, and if the proliferation of literature on witches brought this form of heresy to the public’s attention, then it is only natural that this heresy would have received widespread attention at a time when heresy was in the forefront of people’s minds.

The Catholic Reformation in Bamberg

The Catholic Reformation, sometimes referred to as the Counter-Reformation, [35] was a comprehensive initiative by the Catholic Church to ebb the tide of Protestantism which was sweeping across Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.[36] It began with the Council of Trent in 1545 and ended with the close of the Thirty Years War in 1648.[37] Friedrich Forner has been held to be the architect of the Catholic Reformation in Bramberg, Germany.[38] His literary accomplishments were vast, but his Panoplia Armaturae Dei (Eng. Panoply of the Armor of God probably received the most attention.[39] Panoplia Armaturae Dei was a series of 35 sermons published in 1626 primarily concerned with the threats posed to Catholics by witchcraft and magic.[40] Forner viewed the proliferation of witchcraft to be the Devil’s last desperate attempt to destroy the Catholic faith, considering that the evil heresy of Calvinism had been largely defeated in the first stages of the Thirty Years War.[41] Thus, Forner’s perception of witchcraft was heavily tied into his eschatological beliefs about the ‘End Times’, which was, for obvious reasons, prevalent during the period of the Thirty Years War.[42] Clark notes:

Forner’s sermons were being read by preachers in Sunday and feast-day addresses, and within approximately a year of their publication a third wave of witch hunts, trials and executions ensured in Bamberg.[44] The persecutions of [predominantly] women believed to have been witches in Bamberg were described by Trevor-Roper as having been the worst and most brutal of their time.[45]

The religious insanity in Bamberg was so extreme that it inspired Prince-Bishop Johann Georg Fuchs Von Dornheim to oversee the construction of a “witch prison”, within which was a torture chamber adorned with the relevant biblical passages.[46] The religious authorities and the faithful and frightened laity in Bamberg were so completely seized by this superstitious frenzy that they executed judges they believed were too lenient on “witches” and even the mayor of Bamberg, Johannes Junius, who was put to death on charges of witchcraft.[47] This panic, it may be intimated, was probably further intensified by the works of the Froner, who has been variously dubbed the ‘”spiritus rector” of the witch hunts, a “ferocious witch-damner,” and the “mortal enemy of heretics and sorcerers”’[48], and who was also one of the primary protagonists of the Catholic Reformation in Germany.

Climate Change and Witch Hunts

One historical hypothesis that may possibly mitigate, to some degree, the influence of the European Reformations on the increased severity and intensity of witch hunts during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, is the ‘Little Ice Age Theory’. Proponents of this theory argue that climate change in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries produced meteorological phenomena that had never been witnessed by the people living at the time [49] – like the River Thames in London freezing over between the years 1558-1603,[50] along with the freezing over of Alpine Lakes.[51] On top of these unusual weather phenomena, the climate change is alleged to have occasioned relatively poor, and occasionally completely barren, harvests.[52] These rare climate conditions, scholars like Pfister and Behringer argue, coincided with the previously established belief that witches could affect weather. Behringer comments:

‘The resumption of witch-hunting in the 1560s was accompanied by a debate on weather-making, because this was the most important charge against suspected witches’.[53] Further, Brooke, employing the scapegoat hypothesis, states:

Conclusion

Whether the weather changes assisted in an increase in witch hunts in the early modern period or whether it was the result of a number of ideological, political, or social factors associated with the European Reformations, one thing seems abundantly clear: religion was not merely a catalyst, it was the primary perpetrator. Where might Europeans have drawn their delusional paranoia regarding the perceived threat of the supernatural forces guided by witches if not from religion? Who were the primary propagators of the religious belief in the threat of the demonic and evil forces possessed by witches? They were the clergy, the scholars of the Church, like Kramer, Sprenger, and Froner – men who in their capacity as leaders of the Church spread the fear of witches amongst a religious population who were trained from birth to believe without question. Voltaire once quipped; ‘Those who can make you believe absurdities, can make you commit atrocities’, and such a poignant statement appears entirely applicable to the witch craze of the early modern period in Europe. Thus, although there is sufficient evidence to conclude that the Reformations, both Protestant and Catholic, created an environment in which heresy took centre stage, and that Luther’s doctrine of ‘Sola Scriptura’ led to dogmatic interpretations of the Bible, which further exacerbated the problem – the culprit upon whose shoulders rests the largest portion of blame for the increase in brutal and predominantly misogynistic witch hunts from the sixteenth to the seventeenth centuries, is the superstitious ignorance inherent within religion itself.

End Notes

Rosemary Ellen Guiley, The Encyclopedia of Witches, Witchcraft and Wicca, 3rd , New York: Facts on File, Inc., 2008, p. 50.Canon Episcopi, cited at: http://www.personal.utulsa.edu/~marc-carlson/witch/canon.html, accessed on 2nd April, 2016.Michael D. Bailey, Magic and Superstition in Europe: A Concise History from Antiquity to the Present, Lanham: Rowan and Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2007, p. 122.Anne Llewellyn Barstow, Witchcraze: A New History of the European Witch Hunts, London: Harper-Collins Publishers, 1995, p. 23.Nacham Ben-Yahuda, Problems Inherent in Socio-Historical Approaches to the European Witch Craze, ‘Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion’, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Dec., 1981), 328.Peter H. Wilson, Europe’s Tragedy: A New History of the Thirty Years War, Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009, p.787.Ibid.John M. Murin (ed.), Paul E. Johnson (ed.), James M. McPherson (ed.), Gary Gerstle (ed.), Emily S. Rosenberg (ed.), Norman L. Rosenberg (ed.), Liberty, Equality, Power: A History of the American People, Belmont: Thomson-Wadsworth, 2009, p. 32.Lawrence G. Lovasik, St Joseph Church History, New Jersey: Catholic Book Publishing Corporation, 1990, p. 133.Terrence D. Miethe & Hong Lu, Punishment: A Comparative Historical Perspective, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005, p. 63.Keith Thomas, Religion and the Decline of Magic, Studies in Popular Beliefs in Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century England, London: Penguin Books, 1971, cited at: https://books.google.co.jp/books?id=Ww1uMe7Dj2MC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Religion+and+the+Decline+of+Magic&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwijsODw7-zLAhUHj5QKHRUTDFoQ6AEIHDAA#v=onepage&q=necessary%20precondition&f=false, accessed on 1st April, 2016.Simon McCarthy-Jones, Hearing Voices: The Histories, Causes and Meanings of Auditory Verbal Hallucinations, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012, p. 40.Keith A. Mathison, The Shape of Sola Scriptura, Moscow, Idaho: Canon Press, 2001, pp. 85-86; Mark Greengrass, The Theology and Liturgy of Reformed Christianity, cited in: R. Po-Chia Hsia (ed.), The Cambridge History of Christianity, Vol. 6: Reform and Expansion – 1500-1660, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008, p. 104.Peter Matheson (ed.), Denis R. Janz (ed.), A People’s History of Christianity, Vol. 5: Reformation Christianity, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2010, p. 134.Joseph Needham and Tsien Tsuen-Hsuin, Science and Civilization in China, Vol. 1.1: Paper and Printing, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985, p. 316.Candice Goucher and Linda Walton, World History: Journeys from Past to Present, New York: Routledge, 2008, p. 238.Donald S. Swenson, Society, Spirituality, and the Sacred: A Social Scientific Introduction, 2nd Ed., Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009, p. 250.Anne Llewellyn Barstow, Witchcraze: A New History of the European Witch Hunts, London: Harper-Collins Publishers, 1995, p. 23.Stanley E. Porter, Language and Translations of the New Testament, cited in: J.W. Rogerson and Judith M. Lieu, The Oxford Handbook of Biblical Studies, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006, p. 197.Sidney Jellicoe, The Septuagint and Modern Study, Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1993, p. 5.‘Kashaph’ – Hebrew: Bible Hub, cited at: http://biblehub.com/hebrew/3784.htm, accessed on 2nd April, 2016.Ibid.M.W. Knox, The Medea of Euripides, cited in: T.F. Gould and C.J. Herington, Yale Classical Studies, Vol. XXV: Greek Tragedy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977, p. 214; John M. Riddle, Eve’s Herbs: A History of Contraception and Abortion in the West, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1997, p. 133.The Bible, Exodus 22:18, KJV.John M. Riddle, Eve’s Herbs: A History of Contraception and Abortion in the West, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1997, p. 133.‘Heresy’, Greek, Bible Hub, cited at: http://biblehub.com/greek/139.htm, accessed on 3rd of April, 2016.Ibid.See Irenaeus’ Against the Heresies, dated to around 180 CE: Margaret M. Mitchell (ed.) and Frances M. Young, The Cambridge History of Christianity, Vol. 1: Origins to Constantine, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008, p. 419.Ben Witherington III, The New Cambridge Bible Commentary: Revelation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003, p. 247; Claire Taylor, Heresy in Medieval France: Dualism in Aquitaine and the Agenais, 100-1249, Suffolk: Cromwell Press, 2005, p. 81.Peter H. Wilson, Europe’s Tragedy: A New History of the Thirty Years War, Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009, p. 26.Heinrich Kramer and James Sprenger, Malleus Maleficarum, (trans. Montague Summers), New York: Cosimo Classics, 2007, pp. 2-3. William Monter, The Historiography of European Witchcraft: Progress and Prospects, ‘The Journal of Interdisciplinary History’, Vol. 2, No. 4, Psychoanalysis and History (Spring, 1972), p. 445.Peter T. Leeson and Jacob W. Russ, Witch Trials, p. 12, cited at: http://economics.yale.edu/sites/default/files/witch_trials.pdf, accessed on 1st April, 2016.Anne Llewellyn Barstow, Witchcraze: A New History of the European Witch Hunts, London: Harper-Collins Publishers, 1995, p. 94.The Counter-Reformation, Encyclopedia Britannica, cited at: http://global.britannica.com/event/Counter-Reformation, accessed on 1st April, 2016.Michael A. Mullett, The Catholic Reformation, London: Routledge, 1999, p. 1.Lawrence G. Lovasik, St Joseph Church History, New Jersey: Catholic Book Publishing Corporation, 1990, p. 133.William Bradford Smith, Friedrich Förner, the Catholic Reformation, and Witch-Hunting in Bamberg, ‘The Sixteenth Century Journal’, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Spring, 2005), p. 115.Ibid. pp. 115-116.William Bradford Smith, Reformation and the German Territorial State: Upper Franconia 1300-1630, New York: University of Rochester Press, 2008, p. 173.Ibid. p. 126.Kevin Cramer, The Thirty Years War and German Memory in the Nineteenth Century, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007, p. 225; Ken Kurihara, Celestial Wonders in Reformation Germany, London: Routledge, 2016, p. 157.Stuart Clark, Thinking With Demons: The Idea of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997, p. 454.Bengt Ankarloo, Stuart Clark, William Monter, The Athlone History of Witchcraft and Magic in Europe, London: The Athlone Press, 2002, p. 27.Hugh Redwald Trevor-Roper, The Crisis of the Seventeenth Century: Religion, Reformation, and Social Change, Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, Inc., 1967, p. 146.William E. Burns, Witch Hunts in Europe and America, London: Greenwood Press, 2003, p. 17; Jeffrey B. Russell, Brooks Alexander, A History of Witchcraft: Sorcerers, Heretics and Pagans, 2nd Ed., London: Thames and Hudson, 2007, p. 86.Rosemary Ellen Guiley, The Encyclopedia of Witches, Witchcraft and Wicca, 3rd , New York: Facts on File, Inc., 2008, pp. 187-188.Bradford Smith, Friedrich Förner, the Catholic Reformation, and Witch-Hunting in Bamberg, ‘The Sixteenth Century Journal’, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Spring, 2005), p. 115.Wolfgang Behringer, Climate Change and Witch-Hunting: The Impact of the Little Ice Age on Mentalities, ‘Climate Change Journal’, 43 (1999), Kluwer Academic Publishers, p. 335.Mark Levene (ed.), Rob Johnson (ed.) and Penny Roberts (ed.), History at the End of the World? History, Climate Change and the Possibility of Closure, Tirril Hall: Humanities E-Books, LLP, 2010, p. 69.Ibid.Wolfgang Behringer, A Cultural History of Climate, trans. Patrick Camiller, Munchen: Polity Press, 2007, p. 132.Wolfgang Behringer, Climate Change and Witch-Hunting: The Impact of the Little Ice Age on Mentalities, ‘Climate Change Journal’, 43 (1999), Kluwer Academic Publishers, p. 339.John L. Brooke, Climate Change and the Course of Global History: A Rough Journey, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014, p. 451.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Canon Episcopi, cited at: http://www.personal.utulsa.edu/~marc-carlson/witch/canon.html, accessed on 2nd April, 2016.

Kramer, Heinrich and Sprenger, James, Malleus Maleficarum, (trans. Montague Summers), New York: Cosimo Classics, 2007.

The Bible, Exodus 22:18, KJV.

Secondary Sources

Ankarloo, Bengt, Clark, Stuart, Monter, William, The Athlone History of Witchcraft and Magic in Europe, London: The Athlone Press, 2002.

Bailey, Michael D.,Magic and Superstition in Europe: A Concise History from Antiquity to the Present, Lanham: Rowan and Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2007.

Barstow, Anne Llewellyn, Witchcraze: A New History of the European Witch Hunts, London: Harper-Collins Publishers, 1995.

Behringer, Wolfgang, A Cultural History of Climate, trans. Patrick Camiller, Munchen: Polity Press, 2007.

Behringer, Wolfgang, Climate Change and Witch-Hunting: The Impact of the Little Ice Age on Mentalities, ‘Climate Change Journal’, 43 (1999), Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Ben, David J., The Scientist’s Role in Society, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, Inc., 1971.

Ben-Yahuda, Nacham, Problems Inherent in Socio-Historical Approaches to the European Witch Craze, ‘Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion’, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Dec., 1981).

Brooke, John L., Climate Change and the Course of Global History: A Rough Journey, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Burns, William E., Witch Hunts in Europe and America, London: Greenwood Press, 2003.

Clark, Stuart, Thinking With Demons: The Idea of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Cramer, Kevin, The Thirty Years War and German Memory in the Nineteenth Century, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007.

Currie, E.P., Crime without Victim: Witchcraft and its Control in Renaissance Europe, ‘Law and Society Review’, 3:7-32.

Foucault, Michel, Madness and Civilization, London: Tavistock Publications, 1961.

Goucher, Candice and Walton, Linda, World History: Journeys from Past to Present, New York: Routledge, 2008.

Greengrass, Mark, The Theology and Liturgy of Reformed Christianity, cited in: Hsia, R. Po-Chia (ed.), The Cambridge History of Christianity, Vol. 6: Reform and Expansion – 1500-1660, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Guiley, Rosemary Ellen, The Encyclopedia of Witches, Witchcraft and Wicca, 3rd Ed., New York: Facts on File, Inc., 2008.

Hansen, B., Science and Magic, cited in: Lindberg, D.C. (ed.), Science in the Middle Ages, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975.

Jellicoe, Sidney, The Septuagint and Modern Study, Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1993.

Knox, B.M.W., The Medea of Euripides, cited in: T.F. Gould and C.J. Herington, Yale Classical Studies, Vol. XXV: Greek Tragedy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977.

Kurihara, Ken, Celestial Wonders in Reformation Germany, London: Routledge, 2016.

Leeson, Peter T. and Russ, Jacob W., Witch Trials, cited at: http://economics.yale.edu/sites/default/files/witch_trials.pdf, accessed on 1st April, 2016.

Levene, Mark (ed.), Johnson, Rob (ed.) and Roberts, Penny (ed.), History at the End of the World? History, Climate Change and the Possibility of Closure, Tirril Hall: Humanities E-Books, LLP, 2010.

Lewis I.M., Ecstatic Religion: An Anthropological Study of Spirit Possession, Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1971.

Lovasik, Lawrence G., St Joseph Church History, New Jersey: Catholic Book Publishing Corporation, 1990.

Matheson, Peter (ed.), Janz, Denis R. (ed.), A People’s History of Christianity, Vol. 5: Reformation Christianity, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2010.

Mathison, Keith A., The Shape of Sola Scriptura, Moscow, Idaho: Canon Press, 2001.

McCarthy-Jones, Simon, Hearing Voices: The Histories, Causes and Meanings of Auditory Verbal Hallucinations, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Miethe, Terrence D. & Lu, Hong, Punishment: A Comparative Historical Perspective, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Mitchell, Margaret M. (ed.) and Young, Frances M., The Cambridge History of Christianity, Vol. 1: Origins to Constantine, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Monter, William E., The Historiography of European Witchcraft: Progress and Prospects,

‘The Journal of Interdisciplinary History’, Vol. 2, No. 4, Psychoanalysis and History (Spring, 1972).

Mullett, Michael A., The Catholic Reformation, London: Routledge, 1999.

Murin, John M. (ed.), Johnson, Paul E. (ed.), McPherson, James M. (ed.), Gerstle, Gary (ed.), Rosenberg, Emily S. (ed.), Rosenberg, Norman L. (ed.), Liberty, Equality, Power: A History of the American People, Belmont: Thomson-Wadsworth, 2009.

Needham, Joseph and Tsuen-Hsuin, Tsien, Science and Civilization in China, Vol. 1.1: Paper and Printing, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

Nelson, M., Why Witches Were Women, cited in: Freeman, J. (ed.), Women: A Feminist Perspective, Pal Alto, California: Mayfield Publishing Company, 1975.

Porter, Stanley E., Language and Translations of the New Testament, cited in: Rogerson, J.W. and Lieu, Judith M., The Oxford Handbook of Biblical Studies, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Rattansi, P.M., The Social Interpretation of Science in the Seventeenth Century, cited in: Matthias, P (ed.), Science and Society 1600-1900, London: Cambridge University Press, 1972.

Riddle, John M., Eve’s Herbs: A History of Contraception and Abortion in the West, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Russell, Jeffrey B. and Alexander, Brooks, A History of Witchcraft: Sorcerers, Heretics and Pagans, 2nd Ed., London: Thames and Hudson, 2007.

Senter, P., Witches and Psychiatrists, ‘Journal of Psychiatry’, 10:49-50, 1947.

Shoeneman, T.J., The Role of Mental Illness in the European With Hunts of the 16th and 17th Centuries: An Assessment, ‘Journal of the History of the Behavioural Sciences’, 13:337-351, 1977.

Smith, William Bradford, Friedrich Förner, the Catholic Reformation, and Witch-Hunting in Bamberg, ‘The Sixteenth Century Journal’, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Spring, 2005).

Smith, William Bradford, Reformation and the German Territorial State: Upper Franconia 1300-1630, New York: University of Rochester Press, 2008.

Swenson, Donald S., Society, Spirituality, and the Sacred: A Social Scientific Introduction, 2nd Ed., Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009.

Szasz, T, The Manufacture of Madness, New York: Harper and Row, 1970.

Taylor, Claire, Heresy in Medieval France: Dualism in Aquitaine and the Agenais, 100-1249, Suffolk: Cromwell Press, 2005.

Thomas, Keith, Religion and the Decline of Magic, Studies in Popular Beliefs in Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century England, London: Penguin Books, 1971, cited at: https://books.google.co.jp/books?id=Ww1uMe7Dj2MC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Religion+and+the+Decline+of+Magic&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwijsODw7-zLAhUHj5QKHRUTDFoQ6AEIHDAA#v=onepage&q=necessary%20precondition&f=false, accessed on 1st April, 2016.

Thorndike, L., History of Magic and Experimental Science, New York: Columbia University Press, 1941.

Trevor-Roper, Hugh Redwald, The Crisis of the Seventeenth Century: Religion, Reformation, and Social Change, Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, Inc., 1967.

White, A.D., A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology, New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1913.

Wilson, Peter H., Europe’s Tragedy: A New History of the Thirty Years War, Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009.

Witherington III, Ben, The New Cambridge Bible Commentary: Revelation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Introduction

Prior to the thirteenth century, the Catholic Church’s position on witchcraft, as enunciated within the Canon Episcopi, was that it was a relatively harmless illusion, incapable of directly affecting natural phenomena.[1] Witchcraft was still, according to the widespread belief underpinning the Canon Episcopi, an evil offense worthy of admonition and exile, but the later belief, that it posed an immediate threat to natural phenomena, had yet to arise amongst the superstitious crowds of Christendom.[2] The former position was eventually overturned, and in the first few decades of the fourteenth century, largely as a result of Pope John XXII’s issuance of his Super Illius Specula, which authorized the Inquisition to vigorously prosecute witches [3] – witches, predominantly female,[4] were hunted down, beheaded, burned, drowned, strangled, and slaughtered in the thousands.[5] This barbarism aimed primarily against women reached a fever-pitch within the bloody Thirty Years War (1618-1648) between Catholic and Protestant Christians,[6] and it is estimated that by the end of this religious war, as many as half a million people had been executed on charges of witchcraft.[7]

This essay will briefly examine and discuss a number of ways in which both the Protestant Reformation (1517)[8] and the Catholic-Counter Reformation (1545-1648)[9] encouraged witch hunting in Europe. It will be argued that although these Reformations did contribute largely to the increase in both the severity and zeal with which witch hunts were conducted during these centuries, the primary culprits were religion and superstitious ignorance, just as they continue to co-conspire to commit the same atrocities in overtly religious and superstitious countries like modern Saudi Arabia.[10] It will be argued that the spike in witch hunts during the period in question can be accounted for by placing religion at the foundation of the examination, upon which various social, political and possibly even meteorological contributing factors may be seen as exacerbating influences.

Academic Approaches

Numerous scholars from a variety of academic fields have offered various explanations for the increased intensity of witch hunting from the fourteenth to the seventeenth centuries in Europe. Scholars such as Foucault (1961), Szasz (1970), and Senter (1947), for example, have produced a variety of hypotheses based upon a psychological-psychiatric model, arguing, variously, that this phenomenon can be explained by examining the mental states of the perpetrators and/or the victims. Trevor-Roper (1967), a scholar with one of the most eclectic approaches to the examination of witch hunting in Europe during these centuries, employs a scapegoat hypothesis, which holds that the predominantly female victims of witch hunts were mere scapegoats for the strife faced by Europeans during the period under examination. Other scholars (White, 1913; Thorndike, 1941; Rattansi, 1972; Ben, 1971; Hansen 1975) have argued that the increase in witch hunting can be explained by a superstitious and ignorant misunderstanding of a pre-scientific revolution, which saw some of the first modern attempts at chemistry and other sciences that appeared to a religious and credulous population as magical witchcraft. Further still, other scholars (Nelson, 1975; Currie, 1968; Shoeneman, 1977) have sought to put forth social, political and personal gain models, arguing that the ‘witch craze’ received so much attention that some saw it as a personally and politically profitable avenue for gain, thereby adding impetus to the already fervent persecution of women and men accused of witchcraft. Finally, a small handful of scholars, amongst whom are included Lewis (1971), Trevor-Roper (1967) and Nelson (1975), argue that the inferior status of women was a causal factor in the fervent witch hunts of early modern Europe.

There may be elements of truth in each of the approaches evinced above, as well as those omitted, but the answer may also lie in a more eclectic approach, one that incorporates not only the spur given to the witch hunts by both the Catholic and Protestant Reformations, but by all of the factors mentioned above, which, to varying degrees, may have watered the seeds of religious ignorance in a more general sense. Historian Keith Thomas concurs with this proposition, saying: ‘But religious beliefs as such were a necessary precondition of the prosecutions’.[11]

The Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation began in 1517 with Martin Luther nailing his Ninety-Five Theses on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Saxony.[12] One of the principle doctrines of Luther’s Reformation was Sola Scriptura (‘by scripture alone’), which held that the Bible was the sole and supreme authority on all matters pertaining to doctrine and practice.[13] This principle acted as a driving force which resulted in Bibles being printed in local vernaculars and as an eventual result, increased literacy rates across Europe.[14] This increase in literacy, coupled with the prior advent of the Gutenberg Printing Press in the 1450s,[15] meant that literature of all kinds could be widely disseminated across the European continent.[16] The proliferation of this new media technology meant that treatises which encouraged the hunting and prosecution of witches, such as Heinrich Kramer and James Sprenger’s Malleus Maleficarum (Eng. Hammer of the Witches), published in 1487,[17] were, for the first time, being widely published, and the increased propagation of such literature may have also contributed to the general belief amongst a relatively newly literate laity that witchcraft was becoming an increasingly widespread problem. This proposition ties in with the psychological-psychiatric model, for if such was in fact the case, then the influence of such media over the mentality of an already superstitious and fearful mass of believers would have probably been quite significant.

Luther’s German Translation of Exodus 22:18 – “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live”.

The majority of the victims of the witch hunts in Europe were women. According to Barstow: ‘women were overwhelmingly victimized: on average 80% of those accused and 85% of those killed were female’.[18]

It is no secret that the Bible itself is a wellspring of religious misogyny, from Genesis to Paul’s Epistles – but on top of the pre-existing misogyny that formed the foundation of such gender-focussed persecutions, Luther’s German translation of the Bible, specifically, his translation of Exodus 22:18, was probably another factor which contributed to the zealous witch hunts launched largely against women. The source of Luther’s translation is found amongst a textual tradition known to biblical scholars as the ‘Textus Receptus’, and this textual tradition forms the foundation of the King James Bible.[19] This dubious textual tradition, which, with regards to the Hebrew Bible, drew upon the Greek Septuagint,[20] translated the Hebrew noun כשף [21] (‘kashaph’ – Eng. ‘evil doer’/ ‘sorceress’? The precise meaning is unknown)[22] in Exodus 22:18 to ‘witch’/‘sorceress’ (Gk. ‘pharmakis’).[23] The King James Version of Exodus 22:18 was thus rendered: ‘Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live’.[24]

Luther, following the textual tradition that almost a century later would serve as the foundation of the King James Bible, translated the Hebrew ‘kashaph’ from the Greek ‘pharmakis’ into the German ‘zauberninnen’ (Eng. witches).[25] It is, therefore, reasonable to argue that the Luther’s German translation of ‘pharmakis’ into the local vernacular of the people was a protagonist in the largely female-focussed witch hunts of early modern Europe. If such happens to have been the case, then it goes some way to vindicating the hypothesis of scholars who have sought to attribute the inferior status of women as a causal factor in the witch hunts of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Europe. Add to this translation the newly contrived doctrine of ‘Sola Scriptura’, and the conditions would have been ripe for the persecution of witches, for the Bible, the perceived supreme authority of Christian doctrine and practice commanded such barbarism in the local vernacular of the people.

Heresy and Witches

The word ‘heresy’ stems from the Greek αἵρεσις (‘hairesis’),[26] and it originally connoted a self-chosen, or freely adopted opinion.[27] The meaning of the word was first co-opted and arguably perverted by early Christians.[28] From approximately the second century onward, heresy came to connote wrong belief, and within the exclusivist theology of the Christian religion, this was associated with concept that the Devil is a deceiver and causes people to fall prey to wrong beliefs, or heresies.[29]

The schismatic Reformations in Europe made heresy a prevalent and widely discussed issue, playing a pivotal role in the Thirty Years War.[30] That heresy came to the surface of the consciousness of Christians in Europe at this time is a matter of little dispute, and that witchcraft was branded heretical is also a fact supported by primary historical sources of the time – such as the aforementioned Malleus Maleficarum, an excerpt of which reads:

And those who try to induce others to perform such evil wonders are called witches. And because infidelity in a person who has been baptized is technically called heresy, therefore such persons are plainly heretics.[31]

Further, Monter comments:

‘Continental witch-trials were almost invariably heresy trials as well as trials for malign sorcery, which makes them different both from the English and from virtually all of the non-European societies which have been studied by anthropologists’.[32]

This association of witchcraft with heresy in Europe may have led to a rise in witch hunts due to the boiling accusations of heresy that were being launched at members of competing confessions of Christianity, and it may well be the case that “witches” were not so much a façade as Trevor-Roper has suggested,[33] but both, or either, an external social or internal psychological drive for consistency in an environment fuelled with a feverish religious zeal to prosecute and persecute “heretical enemies” of the “one true” confession of faith, whether they were Catholics, Protestants, or “witches”. It is of interest here to note that in areas unaffected by Protestantism, like Spain and Italy – that is to say – in areas unaffected by the heresy-focusing dissonance between Protestantism and Catholicism, witch hunts and trials were far less frequent.[34] To put it in simpler terms, the public obsession with heresy inspired by the split in Christendom could have inspired authorities and the public at large alike to strive for consistency by persecuting heresy wherever they found it, and if the proliferation of literature on witches brought this form of heresy to the public’s attention, then it is only natural that this heresy would have received widespread attention at a time when heresy was in the forefront of people’s minds.

The Catholic Reformation in Bamberg

The Catholic Reformation, sometimes referred to as the Counter-Reformation, [35] was a comprehensive initiative by the Catholic Church to ebb the tide of Protestantism which was sweeping across Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.[36] It began with the Council of Trent in 1545 and ended with the close of the Thirty Years War in 1648.[37] Friedrich Forner has been held to be the architect of the Catholic Reformation in Bramberg, Germany.[38] His literary accomplishments were vast, but his Panoplia Armaturae Dei (Eng. Panoply of the Armor of God probably received the most attention.[39] Panoplia Armaturae Dei was a series of 35 sermons published in 1626 primarily concerned with the threats posed to Catholics by witchcraft and magic.[40] Forner viewed the proliferation of witchcraft to be the Devil’s last desperate attempt to destroy the Catholic faith, considering that the evil heresy of Calvinism had been largely defeated in the first stages of the Thirty Years War.[41] Thus, Forner’s perception of witchcraft was heavily tied into his eschatological beliefs about the ‘End Times’, which was, for obvious reasons, prevalent during the period of the Thirty Years War.[42] Clark notes:

‘Forner listed the thirteen sins that unleashed demons and witches on errant Catholics (Sermons XII-XIII), and the twenty-four pieces of ‘armour’ that would protect them (Sermons XIV-XXXV)’.[43]

Forner’s sermons were being read by preachers in Sunday and feast-day addresses, and within approximately a year of their publication a third wave of witch hunts, trials and executions ensured in Bamberg.[44] The persecutions of [predominantly] women believed to have been witches in Bamberg were described by Trevor-Roper as having been the worst and most brutal of their time.[45]

The religious insanity in Bamberg was so extreme that it inspired Prince-Bishop Johann Georg Fuchs Von Dornheim to oversee the construction of a “witch prison”, within which was a torture chamber adorned with the relevant biblical passages.[46] The religious authorities and the faithful and frightened laity in Bamberg were so completely seized by this superstitious frenzy that they executed judges they believed were too lenient on “witches” and even the mayor of Bamberg, Johannes Junius, who was put to death on charges of witchcraft.[47] This panic, it may be intimated, was probably further intensified by the works of the Froner, who has been variously dubbed the ‘”spiritus rector” of the witch hunts, a “ferocious witch-damner,” and the “mortal enemy of heretics and sorcerers”’[48], and who was also one of the primary protagonists of the Catholic Reformation in Germany.

Climate Change and Witch Hunts

One historical hypothesis that may possibly mitigate, to some degree, the influence of the European Reformations on the increased severity and intensity of witch hunts during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, is the ‘Little Ice Age Theory’. Proponents of this theory argue that climate change in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries produced meteorological phenomena that had never been witnessed by the people living at the time [49] – like the River Thames in London freezing over between the years 1558-1603,[50] along with the freezing over of Alpine Lakes.[51] On top of these unusual weather phenomena, the climate change is alleged to have occasioned relatively poor, and occasionally completely barren, harvests.[52] These rare climate conditions, scholars like Pfister and Behringer argue, coincided with the previously established belief that witches could affect weather. Behringer comments:

‘The resumption of witch-hunting in the 1560s was accompanied by a debate on weather-making, because this was the most important charge against suspected witches’.[53] Further, Brooke, employing the scapegoat hypothesis, states:

Emerging literatures are demonstrating that not only grain prices fluctuated with climate, leading to subsistence crises, but that early modern Europeans found a scapegoat for their troubles in the form of “weather-making witch”: the great witch hunts of the early modern period exactly bracket the second stage of the Little Ice Age.[54]

Conclusion

Whether the weather changes assisted in an increase in witch hunts in the early modern period or whether it was the result of a number of ideological, political, or social factors associated with the European Reformations, one thing seems abundantly clear: religion was not merely a catalyst, it was the primary perpetrator. Where might Europeans have drawn their delusional paranoia regarding the perceived threat of the supernatural forces guided by witches if not from religion? Who were the primary propagators of the religious belief in the threat of the demonic and evil forces possessed by witches? They were the clergy, the scholars of the Church, like Kramer, Sprenger, and Froner – men who in their capacity as leaders of the Church spread the fear of witches amongst a religious population who were trained from birth to believe without question. Voltaire once quipped; ‘Those who can make you believe absurdities, can make you commit atrocities’, and such a poignant statement appears entirely applicable to the witch craze of the early modern period in Europe. Thus, although there is sufficient evidence to conclude that the Reformations, both Protestant and Catholic, created an environment in which heresy took centre stage, and that Luther’s doctrine of ‘Sola Scriptura’ led to dogmatic interpretations of the Bible, which further exacerbated the problem – the culprit upon whose shoulders rests the largest portion of blame for the increase in brutal and predominantly misogynistic witch hunts from the sixteenth to the seventeenth centuries, is the superstitious ignorance inherent within religion itself.

End Notes

Rosemary Ellen Guiley, The Encyclopedia of Witches, Witchcraft and Wicca, 3rd , New York: Facts on File, Inc., 2008, p. 50.Canon Episcopi, cited at: http://www.personal.utulsa.edu/~marc-carlson/witch/canon.html, accessed on 2nd April, 2016.Michael D. Bailey, Magic and Superstition in Europe: A Concise History from Antiquity to the Present, Lanham: Rowan and Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2007, p. 122.Anne Llewellyn Barstow, Witchcraze: A New History of the European Witch Hunts, London: Harper-Collins Publishers, 1995, p. 23.Nacham Ben-Yahuda, Problems Inherent in Socio-Historical Approaches to the European Witch Craze, ‘Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion’, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Dec., 1981), 328.Peter H. Wilson, Europe’s Tragedy: A New History of the Thirty Years War, Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009, p.787.Ibid.John M. Murin (ed.), Paul E. Johnson (ed.), James M. McPherson (ed.), Gary Gerstle (ed.), Emily S. Rosenberg (ed.), Norman L. Rosenberg (ed.), Liberty, Equality, Power: A History of the American People, Belmont: Thomson-Wadsworth, 2009, p. 32.Lawrence G. Lovasik, St Joseph Church History, New Jersey: Catholic Book Publishing Corporation, 1990, p. 133.Terrence D. Miethe & Hong Lu, Punishment: A Comparative Historical Perspective, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005, p. 63.Keith Thomas, Religion and the Decline of Magic, Studies in Popular Beliefs in Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century England, London: Penguin Books, 1971, cited at: https://books.google.co.jp/books?id=Ww1uMe7Dj2MC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Religion+and+the+Decline+of+Magic&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwijsODw7-zLAhUHj5QKHRUTDFoQ6AEIHDAA#v=onepage&q=necessary%20precondition&f=false, accessed on 1st April, 2016.Simon McCarthy-Jones, Hearing Voices: The Histories, Causes and Meanings of Auditory Verbal Hallucinations, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012, p. 40.Keith A. Mathison, The Shape of Sola Scriptura, Moscow, Idaho: Canon Press, 2001, pp. 85-86; Mark Greengrass, The Theology and Liturgy of Reformed Christianity, cited in: R. Po-Chia Hsia (ed.), The Cambridge History of Christianity, Vol. 6: Reform and Expansion – 1500-1660, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008, p. 104.Peter Matheson (ed.), Denis R. Janz (ed.), A People’s History of Christianity, Vol. 5: Reformation Christianity, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2010, p. 134.Joseph Needham and Tsien Tsuen-Hsuin, Science and Civilization in China, Vol. 1.1: Paper and Printing, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985, p. 316.Candice Goucher and Linda Walton, World History: Journeys from Past to Present, New York: Routledge, 2008, p. 238.Donald S. Swenson, Society, Spirituality, and the Sacred: A Social Scientific Introduction, 2nd Ed., Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009, p. 250.Anne Llewellyn Barstow, Witchcraze: A New History of the European Witch Hunts, London: Harper-Collins Publishers, 1995, p. 23.Stanley E. Porter, Language and Translations of the New Testament, cited in: J.W. Rogerson and Judith M. Lieu, The Oxford Handbook of Biblical Studies, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006, p. 197.Sidney Jellicoe, The Septuagint and Modern Study, Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1993, p. 5.‘Kashaph’ – Hebrew: Bible Hub, cited at: http://biblehub.com/hebrew/3784.htm, accessed on 2nd April, 2016.Ibid.M.W. Knox, The Medea of Euripides, cited in: T.F. Gould and C.J. Herington, Yale Classical Studies, Vol. XXV: Greek Tragedy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977, p. 214; John M. Riddle, Eve’s Herbs: A History of Contraception and Abortion in the West, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1997, p. 133.The Bible, Exodus 22:18, KJV.John M. Riddle, Eve’s Herbs: A History of Contraception and Abortion in the West, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1997, p. 133.‘Heresy’, Greek, Bible Hub, cited at: http://biblehub.com/greek/139.htm, accessed on 3rd of April, 2016.Ibid.See Irenaeus’ Against the Heresies, dated to around 180 CE: Margaret M. Mitchell (ed.) and Frances M. Young, The Cambridge History of Christianity, Vol. 1: Origins to Constantine, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008, p. 419.Ben Witherington III, The New Cambridge Bible Commentary: Revelation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003, p. 247; Claire Taylor, Heresy in Medieval France: Dualism in Aquitaine and the Agenais, 100-1249, Suffolk: Cromwell Press, 2005, p. 81.Peter H. Wilson, Europe’s Tragedy: A New History of the Thirty Years War, Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009, p. 26.Heinrich Kramer and James Sprenger, Malleus Maleficarum, (trans. Montague Summers), New York: Cosimo Classics, 2007, pp. 2-3. William Monter, The Historiography of European Witchcraft: Progress and Prospects, ‘The Journal of Interdisciplinary History’, Vol. 2, No. 4, Psychoanalysis and History (Spring, 1972), p. 445.Peter T. Leeson and Jacob W. Russ, Witch Trials, p. 12, cited at: http://economics.yale.edu/sites/default/files/witch_trials.pdf, accessed on 1st April, 2016.Anne Llewellyn Barstow, Witchcraze: A New History of the European Witch Hunts, London: Harper-Collins Publishers, 1995, p. 94.The Counter-Reformation, Encyclopedia Britannica, cited at: http://global.britannica.com/event/Counter-Reformation, accessed on 1st April, 2016.Michael A. Mullett, The Catholic Reformation, London: Routledge, 1999, p. 1.Lawrence G. Lovasik, St Joseph Church History, New Jersey: Catholic Book Publishing Corporation, 1990, p. 133.William Bradford Smith, Friedrich Förner, the Catholic Reformation, and Witch-Hunting in Bamberg, ‘The Sixteenth Century Journal’, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Spring, 2005), p. 115.Ibid. pp. 115-116.William Bradford Smith, Reformation and the German Territorial State: Upper Franconia 1300-1630, New York: University of Rochester Press, 2008, p. 173.Ibid. p. 126.Kevin Cramer, The Thirty Years War and German Memory in the Nineteenth Century, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007, p. 225; Ken Kurihara, Celestial Wonders in Reformation Germany, London: Routledge, 2016, p. 157.Stuart Clark, Thinking With Demons: The Idea of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997, p. 454.Bengt Ankarloo, Stuart Clark, William Monter, The Athlone History of Witchcraft and Magic in Europe, London: The Athlone Press, 2002, p. 27.Hugh Redwald Trevor-Roper, The Crisis of the Seventeenth Century: Religion, Reformation, and Social Change, Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, Inc., 1967, p. 146.William E. Burns, Witch Hunts in Europe and America, London: Greenwood Press, 2003, p. 17; Jeffrey B. Russell, Brooks Alexander, A History of Witchcraft: Sorcerers, Heretics and Pagans, 2nd Ed., London: Thames and Hudson, 2007, p. 86.Rosemary Ellen Guiley, The Encyclopedia of Witches, Witchcraft and Wicca, 3rd , New York: Facts on File, Inc., 2008, pp. 187-188.Bradford Smith, Friedrich Förner, the Catholic Reformation, and Witch-Hunting in Bamberg, ‘The Sixteenth Century Journal’, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Spring, 2005), p. 115.Wolfgang Behringer, Climate Change and Witch-Hunting: The Impact of the Little Ice Age on Mentalities, ‘Climate Change Journal’, 43 (1999), Kluwer Academic Publishers, p. 335.Mark Levene (ed.), Rob Johnson (ed.) and Penny Roberts (ed.), History at the End of the World? History, Climate Change and the Possibility of Closure, Tirril Hall: Humanities E-Books, LLP, 2010, p. 69.Ibid.Wolfgang Behringer, A Cultural History of Climate, trans. Patrick Camiller, Munchen: Polity Press, 2007, p. 132.Wolfgang Behringer, Climate Change and Witch-Hunting: The Impact of the Little Ice Age on Mentalities, ‘Climate Change Journal’, 43 (1999), Kluwer Academic Publishers, p. 339.John L. Brooke, Climate Change and the Course of Global History: A Rough Journey, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014, p. 451.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Canon Episcopi, cited at: http://www.personal.utulsa.edu/~marc-carlson/witch/canon.html, accessed on 2nd April, 2016.

Kramer, Heinrich and Sprenger, James, Malleus Maleficarum, (trans. Montague Summers), New York: Cosimo Classics, 2007.

The Bible, Exodus 22:18, KJV.

Secondary Sources

Ankarloo, Bengt, Clark, Stuart, Monter, William, The Athlone History of Witchcraft and Magic in Europe, London: The Athlone Press, 2002.

Bailey, Michael D.,Magic and Superstition in Europe: A Concise History from Antiquity to the Present, Lanham: Rowan and Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2007.

Barstow, Anne Llewellyn, Witchcraze: A New History of the European Witch Hunts, London: Harper-Collins Publishers, 1995.

Behringer, Wolfgang, A Cultural History of Climate, trans. Patrick Camiller, Munchen: Polity Press, 2007.

Behringer, Wolfgang, Climate Change and Witch-Hunting: The Impact of the Little Ice Age on Mentalities, ‘Climate Change Journal’, 43 (1999), Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Ben, David J., The Scientist’s Role in Society, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, Inc., 1971.

Ben-Yahuda, Nacham, Problems Inherent in Socio-Historical Approaches to the European Witch Craze, ‘Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion’, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Dec., 1981).

Brooke, John L., Climate Change and the Course of Global History: A Rough Journey, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Burns, William E., Witch Hunts in Europe and America, London: Greenwood Press, 2003.

Clark, Stuart, Thinking With Demons: The Idea of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Cramer, Kevin, The Thirty Years War and German Memory in the Nineteenth Century, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007.

Currie, E.P., Crime without Victim: Witchcraft and its Control in Renaissance Europe, ‘Law and Society Review’, 3:7-32.

Foucault, Michel, Madness and Civilization, London: Tavistock Publications, 1961.

Goucher, Candice and Walton, Linda, World History: Journeys from Past to Present, New York: Routledge, 2008.

Greengrass, Mark, The Theology and Liturgy of Reformed Christianity, cited in: Hsia, R. Po-Chia (ed.), The Cambridge History of Christianity, Vol. 6: Reform and Expansion – 1500-1660, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Guiley, Rosemary Ellen, The Encyclopedia of Witches, Witchcraft and Wicca, 3rd Ed., New York: Facts on File, Inc., 2008.

Hansen, B., Science and Magic, cited in: Lindberg, D.C. (ed.), Science in the Middle Ages, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975.

Jellicoe, Sidney, The Septuagint and Modern Study, Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1993.

Knox, B.M.W., The Medea of Euripides, cited in: T.F. Gould and C.J. Herington, Yale Classical Studies, Vol. XXV: Greek Tragedy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977.

Kurihara, Ken, Celestial Wonders in Reformation Germany, London: Routledge, 2016.

Leeson, Peter T. and Russ, Jacob W., Witch Trials, cited at: http://economics.yale.edu/sites/default/files/witch_trials.pdf, accessed on 1st April, 2016.

Levene, Mark (ed.), Johnson, Rob (ed.) and Roberts, Penny (ed.), History at the End of the World? History, Climate Change and the Possibility of Closure, Tirril Hall: Humanities E-Books, LLP, 2010.

Lewis I.M., Ecstatic Religion: An Anthropological Study of Spirit Possession, Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1971.

Lovasik, Lawrence G., St Joseph Church History, New Jersey: Catholic Book Publishing Corporation, 1990.

Matheson, Peter (ed.), Janz, Denis R. (ed.), A People’s History of Christianity, Vol. 5: Reformation Christianity, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2010.

Mathison, Keith A., The Shape of Sola Scriptura, Moscow, Idaho: Canon Press, 2001.

McCarthy-Jones, Simon, Hearing Voices: The Histories, Causes and Meanings of Auditory Verbal Hallucinations, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Miethe, Terrence D. & Lu, Hong, Punishment: A Comparative Historical Perspective, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Mitchell, Margaret M. (ed.) and Young, Frances M., The Cambridge History of Christianity, Vol. 1: Origins to Constantine, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Monter, William E., The Historiography of European Witchcraft: Progress and Prospects,

‘The Journal of Interdisciplinary History’, Vol. 2, No. 4, Psychoanalysis and History (Spring, 1972).

Mullett, Michael A., The Catholic Reformation, London: Routledge, 1999.

Murin, John M. (ed.), Johnson, Paul E. (ed.), McPherson, James M. (ed.), Gerstle, Gary (ed.), Rosenberg, Emily S. (ed.), Rosenberg, Norman L. (ed.), Liberty, Equality, Power: A History of the American People, Belmont: Thomson-Wadsworth, 2009.

Needham, Joseph and Tsuen-Hsuin, Tsien, Science and Civilization in China, Vol. 1.1: Paper and Printing, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

Nelson, M., Why Witches Were Women, cited in: Freeman, J. (ed.), Women: A Feminist Perspective, Pal Alto, California: Mayfield Publishing Company, 1975.

Porter, Stanley E., Language and Translations of the New Testament, cited in: Rogerson, J.W. and Lieu, Judith M., The Oxford Handbook of Biblical Studies, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Rattansi, P.M., The Social Interpretation of Science in the Seventeenth Century, cited in: Matthias, P (ed.), Science and Society 1600-1900, London: Cambridge University Press, 1972.

Riddle, John M., Eve’s Herbs: A History of Contraception and Abortion in the West, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Russell, Jeffrey B. and Alexander, Brooks, A History of Witchcraft: Sorcerers, Heretics and Pagans, 2nd Ed., London: Thames and Hudson, 2007.

Senter, P., Witches and Psychiatrists, ‘Journal of Psychiatry’, 10:49-50, 1947.

Shoeneman, T.J., The Role of Mental Illness in the European With Hunts of the 16th and 17th Centuries: An Assessment, ‘Journal of the History of the Behavioural Sciences’, 13:337-351, 1977.

Smith, William Bradford, Friedrich Förner, the Catholic Reformation, and Witch-Hunting in Bamberg, ‘The Sixteenth Century Journal’, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Spring, 2005).

Smith, William Bradford, Reformation and the German Territorial State: Upper Franconia 1300-1630, New York: University of Rochester Press, 2008.

Swenson, Donald S., Society, Spirituality, and the Sacred: A Social Scientific Introduction, 2nd Ed., Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009.

Szasz, T, The Manufacture of Madness, New York: Harper and Row, 1970.

Taylor, Claire, Heresy in Medieval France: Dualism in Aquitaine and the Agenais, 100-1249, Suffolk: Cromwell Press, 2005.

Thomas, Keith, Religion and the Decline of Magic, Studies in Popular Beliefs in Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century England, London: Penguin Books, 1971, cited at: https://books.google.co.jp/books?id=Ww1uMe7Dj2MC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Religion+and+the+Decline+of+Magic&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwijsODw7-zLAhUHj5QKHRUTDFoQ6AEIHDAA#v=onepage&q=necessary%20precondition&f=false, accessed on 1st April, 2016.

Thorndike, L., History of Magic and Experimental Science, New York: Columbia University Press, 1941.

Trevor-Roper, Hugh Redwald, The Crisis of the Seventeenth Century: Religion, Reformation, and Social Change, Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, Inc., 1967.