Anthony McIntyre's Blog, page 1175

November 18, 2017

‘The Myanmar Deception': Reviewing The Context

In a follow-up to his recent article, The Myanmar Deception, and by way of response to those who have attacked it, Sean Bresnahan, a regular contributor to The Pensive Quill, offers an interesting insight into his thinking and motives when writing the piece.

Though it can sometimes expose us to ridicule – worse still to the charge of being ‘reactionary’ or ‘racist’ – it’s important no less that we try and speed a greater awareness regards geopolitics and the reality of how imperialism operates. We will not always get it right. Thanks, no matter, to The Pensive Quill for affording a platform were such can be attempted.

‘Human rights’ have now become an instrument of imperialist warfare, as crazy as that might sound. The agenda is manipulated on two fronts through the employ of Islamist jihadis — these having been integrated by the Western intelligence apparatus to divide target nations and in turn to usurp their resources.

On the one hand and in the first guise – that of which ‘Jihadi John’ was a notable caricature – they provide a pretext for military intervention to quash their supposed threat. On the other and in a different guise they provide a different pretext, one useful to target ‘human rights abusers’ who respond or are seen to respond to their provocations; a la Milosevic, Qaddafi and Assad. This is the grisly genius of ‘humanitarian war’.

With the routing of the ISIS and Peshmerga mercenaries in Iraq and Syria, the imperialist is getting nervous. The inability to finish off Yemen only compounds matters further. He has no intention, however, of quitting his heinous game — knowing no other way than death and destruction as his empire threatens to unravel. The Middle East on fire, Far Asia is now in his sights.

To speak candidly on all of this is to put yourself on a ledge to be stoned by the ultra-liberal ‘PC’ Left, who have been wholly absorbed by identity politics and the cultivation of image requirement introduced us by modern propaganda methods. The ultimate purpose here is to deflect us away from the concrete setting in which events take shape. That is the sad reality of where we are at.

While it may not be their intention, their browbeating serves to subdue thinking that is ‘outside the box’ — leaving people too afraid to voice their opinion for fear of being cast in the wrong light. Perhaps this is the real aim, even if those concerned don’t partake in this action consciously. In this respect, petty bourgeois leftists are as much an obstacle as the bankers — perhaps, indeed, they are even more so.

In their self-righteous assuredness, they inhibit (by their attacks on any narrative from outside their neat little boxes) the pressing requirement that we advance a greater understanding among ordinary people as to how the world really works, this that we might from there set out toward improving the lives of working people – and with them the poor – at a structural level. Fail to countenance the structure at core and we can change very little in regards where it counts.

My aim was towards this intent and not to determine the ins-and-outs of the crisis in Rakhine — who done what to whom; who is right or wrong; who is more worthy of our support or condemnation. My interest is not to dismiss such issues, which are worthy in their own regard, but to look beyond in search of solutions that the ills of our imperiled world might be found. As socialists and anti-imperialists, it is this in the end that we seek.

Rape, torture and murder are in no way acceptable and there is no suggestion otherwise. That said it's noteworthy that, rather than present proof that Suu Kyi is responsible for what she stands accused of or to admit in any way that the Buddhists – or even the Burmese state itself – might themselves have a different story worth considering, the do-gooder liberal class resort instead to a familiar type: smear and shout down anyone who dares to step outside their narrative.

But that differing versions of events should be considered does not mean we support or deny a particular narrative either way – except of course in the minds of fanatical internet warriors who treat discussion as though a contest of intellect. We consider these things not to win or to ‘do down’ the other but to try and establish a more complete picture for the benefit of all.

As argued in the piece, we must examine events as we meet and find them in their core ideological setting. In the instance of Myanmar, the US ‘Asia Pivot’ and its immediate rival – the Chinese ‘One Belt One Road’ – is the context to which we must look. The Zionist ‘War On Terror’ and the tactics it utilises is also important to our understanding.

There are those, no doubt, for whom the idea intelligence agencies would manipulate events to the point of their generation is well-beyond fanciful. The historical record, in spite of them, clearly tells us otherwise — not least in regard to the most recent history of the Middle East. The directing of jihadi terrorist groups to serve ulterior strategies is well-established and, like the collusion war in Ireland, is not mere 'conspiracy theory' as some would seek to tar it.

Returning to the Asia Pivot, the campaign to isolate Aung San Suu Kyi is for travelling in the wrong direction and has no relationship, beyond that, with the crisis in Rakhine State — a crisis which, of course, is very real for its many victims. None of that is to say that there aren’t issues with the Burmese military but that the situation is much more complex than what we are being presented.

We are presented a packaged version of the Myanmar story that ignores objectivity and with it the narrative of Rakhine’s Buddhist community. Here, only the Rohingya are victims as the ‘Rogingya genocide’ is the narrative which suits the requirements of the imperialist grand design.

In this regard, similar to the Libyan and Syrian instances (also no doubt 'conspiracy theories' in the minds of the liberal left), the Rohingya genocide story is intended to manipulate the vast majority here in the West, who have next-to-no understanding of both the history and the geopolitical context of Myanmar, the Bay of Bengal or the Silk Road old and new. In and through our state of ignorance, the Zionist ‘War Of Terror’ marches on.

Not to be terse but perhaps we’ll be content when our naivety helps deliver a ‘Balkanisation’ of Myanmar, with an Al Qaeda-run Kosovo-style ‘independent’ Rakhine – subject of course to Washington – in turn to be used as a base to push the Zionist false flag Salvador Option deeper and deeper into Asia.

In the final analysis, if we don’t deal with imperialism – regardless its hue – then in truth we cannot effect the changes we require as a global society and community. This is as much a necessity for the Rohingya as it is for all others. If we don’t understand imperialism and the tactics it uses in pursuit of its objects then how could we ever hope to deal with it, as we must?

Regardless of them who smear and undermine, often for their own sly motives, thanks to those who took the time to countenance what was actually written — not how they’d prefer it to be read. Articles as these are extremely tricky, to say the least, made all the more so in the knowledge there are always those lying in wait for the opportune moment to strike. The issues we face, though, are much too important that they and their methods be allowed to intimidate.

‘We have nothing to lose but our chains...’

Though it can sometimes expose us to ridicule – worse still to the charge of being ‘reactionary’ or ‘racist’ – it’s important no less that we try and speed a greater awareness regards geopolitics and the reality of how imperialism operates. We will not always get it right. Thanks, no matter, to The Pensive Quill for affording a platform were such can be attempted.

‘Human rights’ have now become an instrument of imperialist warfare, as crazy as that might sound. The agenda is manipulated on two fronts through the employ of Islamist jihadis — these having been integrated by the Western intelligence apparatus to divide target nations and in turn to usurp their resources.

On the one hand and in the first guise – that of which ‘Jihadi John’ was a notable caricature – they provide a pretext for military intervention to quash their supposed threat. On the other and in a different guise they provide a different pretext, one useful to target ‘human rights abusers’ who respond or are seen to respond to their provocations; a la Milosevic, Qaddafi and Assad. This is the grisly genius of ‘humanitarian war’.

With the routing of the ISIS and Peshmerga mercenaries in Iraq and Syria, the imperialist is getting nervous. The inability to finish off Yemen only compounds matters further. He has no intention, however, of quitting his heinous game — knowing no other way than death and destruction as his empire threatens to unravel. The Middle East on fire, Far Asia is now in his sights.

To speak candidly on all of this is to put yourself on a ledge to be stoned by the ultra-liberal ‘PC’ Left, who have been wholly absorbed by identity politics and the cultivation of image requirement introduced us by modern propaganda methods. The ultimate purpose here is to deflect us away from the concrete setting in which events take shape. That is the sad reality of where we are at.

While it may not be their intention, their browbeating serves to subdue thinking that is ‘outside the box’ — leaving people too afraid to voice their opinion for fear of being cast in the wrong light. Perhaps this is the real aim, even if those concerned don’t partake in this action consciously. In this respect, petty bourgeois leftists are as much an obstacle as the bankers — perhaps, indeed, they are even more so.

In their self-righteous assuredness, they inhibit (by their attacks on any narrative from outside their neat little boxes) the pressing requirement that we advance a greater understanding among ordinary people as to how the world really works, this that we might from there set out toward improving the lives of working people – and with them the poor – at a structural level. Fail to countenance the structure at core and we can change very little in regards where it counts.

My aim was towards this intent and not to determine the ins-and-outs of the crisis in Rakhine — who done what to whom; who is right or wrong; who is more worthy of our support or condemnation. My interest is not to dismiss such issues, which are worthy in their own regard, but to look beyond in search of solutions that the ills of our imperiled world might be found. As socialists and anti-imperialists, it is this in the end that we seek.

Rape, torture and murder are in no way acceptable and there is no suggestion otherwise. That said it's noteworthy that, rather than present proof that Suu Kyi is responsible for what she stands accused of or to admit in any way that the Buddhists – or even the Burmese state itself – might themselves have a different story worth considering, the do-gooder liberal class resort instead to a familiar type: smear and shout down anyone who dares to step outside their narrative.

But that differing versions of events should be considered does not mean we support or deny a particular narrative either way – except of course in the minds of fanatical internet warriors who treat discussion as though a contest of intellect. We consider these things not to win or to ‘do down’ the other but to try and establish a more complete picture for the benefit of all.

As argued in the piece, we must examine events as we meet and find them in their core ideological setting. In the instance of Myanmar, the US ‘Asia Pivot’ and its immediate rival – the Chinese ‘One Belt One Road’ – is the context to which we must look. The Zionist ‘War On Terror’ and the tactics it utilises is also important to our understanding.

There are those, no doubt, for whom the idea intelligence agencies would manipulate events to the point of their generation is well-beyond fanciful. The historical record, in spite of them, clearly tells us otherwise — not least in regard to the most recent history of the Middle East. The directing of jihadi terrorist groups to serve ulterior strategies is well-established and, like the collusion war in Ireland, is not mere 'conspiracy theory' as some would seek to tar it.

Returning to the Asia Pivot, the campaign to isolate Aung San Suu Kyi is for travelling in the wrong direction and has no relationship, beyond that, with the crisis in Rakhine State — a crisis which, of course, is very real for its many victims. None of that is to say that there aren’t issues with the Burmese military but that the situation is much more complex than what we are being presented.

We are presented a packaged version of the Myanmar story that ignores objectivity and with it the narrative of Rakhine’s Buddhist community. Here, only the Rohingya are victims as the ‘Rogingya genocide’ is the narrative which suits the requirements of the imperialist grand design.

In this regard, similar to the Libyan and Syrian instances (also no doubt 'conspiracy theories' in the minds of the liberal left), the Rohingya genocide story is intended to manipulate the vast majority here in the West, who have next-to-no understanding of both the history and the geopolitical context of Myanmar, the Bay of Bengal or the Silk Road old and new. In and through our state of ignorance, the Zionist ‘War Of Terror’ marches on.

Not to be terse but perhaps we’ll be content when our naivety helps deliver a ‘Balkanisation’ of Myanmar, with an Al Qaeda-run Kosovo-style ‘independent’ Rakhine – subject of course to Washington – in turn to be used as a base to push the Zionist false flag Salvador Option deeper and deeper into Asia.

In the final analysis, if we don’t deal with imperialism – regardless its hue – then in truth we cannot effect the changes we require as a global society and community. This is as much a necessity for the Rohingya as it is for all others. If we don’t understand imperialism and the tactics it uses in pursuit of its objects then how could we ever hope to deal with it, as we must?

Regardless of them who smear and undermine, often for their own sly motives, thanks to those who took the time to countenance what was actually written — not how they’d prefer it to be read. Articles as these are extremely tricky, to say the least, made all the more so in the knowledge there are always those lying in wait for the opportune moment to strike. The issues we face, though, are much too important that they and their methods be allowed to intimidate.

‘We have nothing to lose but our chains...’

Published on November 18, 2017 09:55

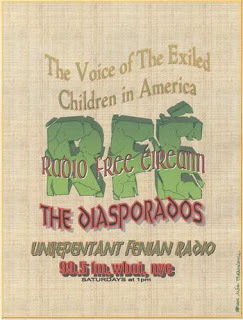

Radio Free Eireann Broadcasting 18 November 2017

Martin Galvin

with details of this weekend's broadcast from

Radio Free Eireann.

Radio Free Eireann will broadcast this Saturday November 18th on wbai 99.5 FM or wbai.org at 12noon-1pm New York time or 5pm-6pm Irish time or anytime after the program on wbai.org/archives.

Award winning journalist ,now political editor of the Belfast Telegraph, Suzanne Breen will give up to the minute coverage of the Sinn Fein Ard Fheis or national party convention, including a dramatic policy shift on entering coalitions in the south, report on Stormont talks, an announcement about Gerry Adams' succession plans and debate on abortion policy.

Author and journalist Ed Moloney will cover new developments on the Boston Tapes litigation.

John McDonagh will talk about the final performances on his one man show Off The Meter: On The Record, at the Irish Repertory Theatre.

John McDonagh and Martin Galvin co- host.

Radio Free Eireann is heard Saturdays at 12 Noon New York time on wbai 99.5 FM and wbai.org.

It can be heard at wbai.org in Ireland from 5pm to 6pm or anytime after the program concludes on wbai.org/archives.

Radio Free Eireann will broadcast this Saturday November 18th on wbai 99.5 FM or wbai.org at 12noon-1pm New York time or 5pm-6pm Irish time or anytime after the program on wbai.org/archives.

Award winning journalist ,now political editor of the Belfast Telegraph, Suzanne Breen will give up to the minute coverage of the Sinn Fein Ard Fheis or national party convention, including a dramatic policy shift on entering coalitions in the south, report on Stormont talks, an announcement about Gerry Adams' succession plans and debate on abortion policy.

Author and journalist Ed Moloney will cover new developments on the Boston Tapes litigation.

John McDonagh will talk about the final performances on his one man show Off The Meter: On The Record, at the Irish Repertory Theatre.

John McDonagh and Martin Galvin co- host.

Radio Free Eireann is heard Saturdays at 12 Noon New York time on wbai 99.5 FM and wbai.org.

It can be heard at wbai.org in Ireland from 5pm to 6pm or anytime after the program concludes on wbai.org/archives.

Published on November 18, 2017 01:27

November 17, 2017

Lord Bob

Published on November 17, 2017 11:47

BBC's 'Irish Troubles',

Christopher Owens with the latest in a series of reviews looks at a book on BBC NI.

Long regarded as the bastion of the British establishment, the BBC have often produced works that have both dealt with the history of this country in terms that could be described as informative. However, it's well publicised that their news coverage (which, let's remember, goes around the world) can often be lacking.

First published in 2015, Robert J. Savage's look at the history of BBC NI and it's role in this country and it's recent history. There have been studies of this topic before, like Rex Cathcart's The Most Contrary Region: The BBC in Northern Ireland 1924-1984, but Savage is able to use recently declassified documents in order to help give a broader picture for the scenes that played out in Broadcasting House.

Beginning from the first BBC NI radio broadcast in 1924, it's clear that the local members of the organisation were all too aware of the need to toe the line by the Stormont government. English journalists often tried to offer a more nuanced view, but were shot down by horrified executives, politicians and newspaper editors (Alan Whicker's segment for 'Tonight' that aired in 1959 is one such example cited).

These depictions of the early stages of the Six Counties make for tremendous reading. Often, the history books tend to start with the 1960's, so it's always intriguing to see just how far discrimination went down in the state, to the extent that references to gerrymandering and the poor upkeep of nationalist areas of the country were often deleted from programmes.

As events move onto the Civil Rights Association, through to the Army arriving and the beginning of violence, BBC NI journalists are depicted as seekers of the truth, openly despised by Stormont officials because of their questioning of the official line. Indeed, it's claimed that UTV and ITV were much preferred as they took the press office at their word. But said BBC journalists freely admit that their coverage of August 1969 was deeply flawed, and led to the perception in England of the conflict being one purely about religious differences, as opposed to civil rights and overt oppression.

Savage's writing style can be a little on the dry side at times, being overtly direct and with a tendency to repeat certain phrases and information about particular people. Unsurprisingly, this grates on the reader quickly. Also, he doesn't really ask questions that arise from particular incidents (apart from one that will be dealt with later on). It's just a case of describing particular moments, the reaction/coverage from the BBC and the implications of it.

In most cases, this is fine as events in the early 70's move so quickly throughout the book that it's quickly replaced by another. But by the time we get to the end of that decade, and the description of Roy Mason's open war on the corporation for their coverage of the Bernard O'Connor case, there are enough questions that can be raised by the reader.

For example, he uses the coverage of the Ulster Workers Council strike to show the disconnect that often existed between the BBC and the rest of the world. The Board of Governors genuinely seemed to think the NI branch had done a good job covering the strike (despite not offering any alternate viewpoints so beloved of the BBC), and Robert Fisk's expose of the coverage burst that particular bubble.

So what exactly made the Board decide such coverage was acceptable for broadcast? Did BBC NI staff do anything to indicate their supposed frustration at their bosses, like threaten a walkout? Questions like these are left unanswered, and I think they do deserve answers.

It has often been written about journalists north and south routinely felt the need to display how anti IRA they could be, in order to displace notions of them being (to quote Ed Moloney) "fellow travellers", and this is something that could certainly have been explored in depth as to why BBC NI staff (seemingly) did nothing.

The most fascinating moment comes when a Panorama crew end up filming an IRA unit setting up an impromptu checkpoint in Carrickmore in 1979. Through a set of circumstances involving lack of communication and gut reaction, the footage threatened the stability of the BBC with the Thatcher government, who were already furious at the BBC for interviewing an INLA spokesperson the same year.

Although there is a pervading feeling throughout that someone somewhere is holding back (and he is not prepared to cross the line and name names), Savage explores the various reactions from BBC management, and it comes across as the sort of bureaucratic nightmare often envisaged by Orwell and Kafka, with the ever real threat of journalists potentially being arrested for interviewing illegal organisations.

Savage argues, convincingly, that this was the beginning of the crackdown of broadcasters freedom by the Thatcher government which would ultimately culminate in her reaction to the ITV 'Death on the Rock' programme.

After the "Carrickmore incident", the book gets quite tedious, with the usual round of people complaining about bias over the hunger strike. The book ends with the broadcasting ban, and Savage admits this is mainly because the amount of declassified papers from this period onwards are nowhere near the same amount as the previous years.

It's certainly a worthy addition to the ever growing shelf of Troubles related texts, but it's writing style, lack of open questioning and cut off period stop it from being definitive. What is really needed are volumes dealing with the other major British broadcasters, and the media. The results would be interesting, and would give academics pause for thought about the power of the media to shape the ordinary person's opinion on such matters.

Robert J. Savage, 2015, The BBC's 'Irish Troubles': Television, Conflict and Northern Ireland Manchester University Press, ISBN-13: 978-1526116888

Christopher Owens reviews for Metal Ireland and finds time to study the history and inherent contradictions of Ireland.

Follow Christopher Owens on Twitter @MrOwens212

Long regarded as the bastion of the British establishment, the BBC have often produced works that have both dealt with the history of this country in terms that could be described as informative. However, it's well publicised that their news coverage (which, let's remember, goes around the world) can often be lacking.

First published in 2015, Robert J. Savage's look at the history of BBC NI and it's role in this country and it's recent history. There have been studies of this topic before, like Rex Cathcart's The Most Contrary Region: The BBC in Northern Ireland 1924-1984, but Savage is able to use recently declassified documents in order to help give a broader picture for the scenes that played out in Broadcasting House.

Beginning from the first BBC NI radio broadcast in 1924, it's clear that the local members of the organisation were all too aware of the need to toe the line by the Stormont government. English journalists often tried to offer a more nuanced view, but were shot down by horrified executives, politicians and newspaper editors (Alan Whicker's segment for 'Tonight' that aired in 1959 is one such example cited).

These depictions of the early stages of the Six Counties make for tremendous reading. Often, the history books tend to start with the 1960's, so it's always intriguing to see just how far discrimination went down in the state, to the extent that references to gerrymandering and the poor upkeep of nationalist areas of the country were often deleted from programmes.

As events move onto the Civil Rights Association, through to the Army arriving and the beginning of violence, BBC NI journalists are depicted as seekers of the truth, openly despised by Stormont officials because of their questioning of the official line. Indeed, it's claimed that UTV and ITV were much preferred as they took the press office at their word. But said BBC journalists freely admit that their coverage of August 1969 was deeply flawed, and led to the perception in England of the conflict being one purely about religious differences, as opposed to civil rights and overt oppression.

Savage's writing style can be a little on the dry side at times, being overtly direct and with a tendency to repeat certain phrases and information about particular people. Unsurprisingly, this grates on the reader quickly. Also, he doesn't really ask questions that arise from particular incidents (apart from one that will be dealt with later on). It's just a case of describing particular moments, the reaction/coverage from the BBC and the implications of it.

In most cases, this is fine as events in the early 70's move so quickly throughout the book that it's quickly replaced by another. But by the time we get to the end of that decade, and the description of Roy Mason's open war on the corporation for their coverage of the Bernard O'Connor case, there are enough questions that can be raised by the reader.

For example, he uses the coverage of the Ulster Workers Council strike to show the disconnect that often existed between the BBC and the rest of the world. The Board of Governors genuinely seemed to think the NI branch had done a good job covering the strike (despite not offering any alternate viewpoints so beloved of the BBC), and Robert Fisk's expose of the coverage burst that particular bubble.

So what exactly made the Board decide such coverage was acceptable for broadcast? Did BBC NI staff do anything to indicate their supposed frustration at their bosses, like threaten a walkout? Questions like these are left unanswered, and I think they do deserve answers.

It has often been written about journalists north and south routinely felt the need to display how anti IRA they could be, in order to displace notions of them being (to quote Ed Moloney) "fellow travellers", and this is something that could certainly have been explored in depth as to why BBC NI staff (seemingly) did nothing.

The most fascinating moment comes when a Panorama crew end up filming an IRA unit setting up an impromptu checkpoint in Carrickmore in 1979. Through a set of circumstances involving lack of communication and gut reaction, the footage threatened the stability of the BBC with the Thatcher government, who were already furious at the BBC for interviewing an INLA spokesperson the same year.

Although there is a pervading feeling throughout that someone somewhere is holding back (and he is not prepared to cross the line and name names), Savage explores the various reactions from BBC management, and it comes across as the sort of bureaucratic nightmare often envisaged by Orwell and Kafka, with the ever real threat of journalists potentially being arrested for interviewing illegal organisations.

Savage argues, convincingly, that this was the beginning of the crackdown of broadcasters freedom by the Thatcher government which would ultimately culminate in her reaction to the ITV 'Death on the Rock' programme.

After the "Carrickmore incident", the book gets quite tedious, with the usual round of people complaining about bias over the hunger strike. The book ends with the broadcasting ban, and Savage admits this is mainly because the amount of declassified papers from this period onwards are nowhere near the same amount as the previous years.

It's certainly a worthy addition to the ever growing shelf of Troubles related texts, but it's writing style, lack of open questioning and cut off period stop it from being definitive. What is really needed are volumes dealing with the other major British broadcasters, and the media. The results would be interesting, and would give academics pause for thought about the power of the media to shape the ordinary person's opinion on such matters.

Robert J. Savage, 2015, The BBC's 'Irish Troubles': Television, Conflict and Northern Ireland Manchester University Press, ISBN-13: 978-1526116888

Christopher Owens reviews for Metal Ireland and finds time to study the history and inherent contradictions of Ireland.

Follow Christopher Owens on Twitter @MrOwens212

Published on November 17, 2017 01:00

November 16, 2017

The Terrible Problem

The Uri Avnery Column discusses the ideas of Ze'ev Begin.Ze'ev Begin, the son of Menachem Begin, is a very nice human being. It is impossible not to like him. He is well brought up, polite and modest, the kind of person one would like to have as a friend.

Unfortunately, his political views are far less likeable. They are much more extreme than even the acts of his father. The father, after leading the Irgun, sat down and made peace with Anwar al-Sadat of Egypt. Ze'ev is closer to Golda Me'ir, who ignored Sadat's peace overtures and led us into the disastrous Yom Kippur war.

Begin jr. is a strict follower of the "revisionist" Zionist creed founded by Vladimir Ze'ev Jabotinsky. One of the characteristics of this movement has always been the importance it gave to written texts and declarations. The labor movement, headed by David Ben-Gurion, didn't give a damn about words and declarations and respected only "facts on the ground".

Last week, Ze'ev Begin wrote one of his rare articles. Its main purpose was to prove that peace with the Palestinians is impossible, a pipe-dream of Israeli peace-lovers (Haaretz 9.10). Quoting numerous Palestinian texts, speeches and even schoolbooks, Begin shows that the Palestinians will never, never, never give up their "Right of Return".

Since such a return would entail the end of the Jewish State, Begin asserts, peace is a pipe dream. There will never be peace. End of story.

A Similar point is made by another profound thinker, Alexander Jakobson, in another important article in Haaretz (9.26). It is directed against me personally, and its headline asserts that I am "True to Israel, but Not to the Truth". It accuses me of being tolerant towards the BDS movement, which is out to put an end to Israel.

How does he know? Simple: BDS confirms the Palestinians' "Right of Return", which, as everybody knows, means the destruction of the Jewish State.

Well, actually I object to BDS for several reasons. The movement to which I belong, Gush Shalom, was the first (in 1997) to declare a boycott of the settlements. Our aim was to separate the Israeli people from the settlements. The BDS (Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions) movement, by boycotting all of Israel, achieves the opposite effect: it pushes the Israeli people into the arms of the settlers.

I also don't like to call on people to boycott me.

But of all the points in the BDS platform, the one that bothers me the least is the demand that the State of Israel recognize the Palestinians' Right of Return. It is simply ridiculous. Not in a thousand years will the BDS compel Israel to do so. So why bother?

Let' Us First throw some light on the issue.

When the British withdrew from Palestine in 1948, there were in the country between the Mediterranean and the Jordan about 1.2 million Arabs and 635,000 Jews. By the end of the war that ensued, some 700,000 Arabs had fled and/or were driven out. It was a war of what was (later) called "ethnic cleansing". Few Arabs were left in the territory conquered by Jewish arms, but it should be remembered that no Jews at all were left in the territory conquered by Arab arms. Fortunately for our side, the Arabs succeeded in occupying only small slices of land inhabited by Jews (such as the Etzion bloc, East Jerusalem et al.), while our side conquered large, inhabited territories. As a combat soldier, I saw it with my own eyes.

The Arab refugees multiplied by natural increase, and today number about 6 million. About 1.5 million of them live in the occupied West Bank, about a million in the Gaza Strip, the rest are dispersed in Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and all over the world.

Would they all come back, if given the opportunity? Let us consider this.

Years Ago, I had a unique experience.

I was invited to give a lecture in New York. To my pleasant surprise, in the front row I saw a good friend of mine, the young Arab poet Rashid Hussein. Rashid was born in a village near Nazareth. He begged me to come and visit him in his New Jersey apartment.

When I arrived, I was flabbergasted, The small apartment was crowded with people – Palestinian refugees of all kinds, young and old, men and women. We had a long and extremely emotional discussion on the refugee issue.

When we drove home, I told my wife: "You know what I felt? That only a few of them really care to return, but that all of them were ready to die for their right to return!"

Rachel, a very keen observer, replied that she had the same impression.

Today, Dozens of years later, I am convinced that this basic truth is still valid: there is a huge difference between the principle and its implementation.

The principle cannot be denied. It belongs to the individual refugee. It is safeguarded by international law. It is sacred.

Any future peace treaty between the state of Israel and the State of Palestine will have to include a paragraph saying that Israel affirms in principle the Right of Return of the Palestinian refugees and their descendants.

No Palestinian leader could possibly sign a treaty that does not include this clause.

Only after this obstacle has been removed from the table, can the real discussion about the solution start.

I can imagine the scene: after agreement has been reached on this at the peace conference, the chairperson will take a deep breath and say, "Now, friends, let's get to the real issue. How shall we solve the refugee problem in practice?"

The six million Palestinian refugees constitute six million individual situations. There are many categories of refugees. No single solution can apply to all.

There are many refugees – perhaps most of them - who during the last 50 years have built for themselves a new life in another country. For these, the right of return is – well – a principle. They would not dream of going back to their ancestral village, even if it were still there. Some of them are well-to-do, some are rich, some very rich.

One of the richest is my friend (may I call you so?) Salman Abu Sitta, who started life as a barefoot boy in the Negev, fled in 1948 with his family to Gaza and later became an immensely successful contractor in Britain and the Gulf. We met at a peace conference, had a long and emotional private dinner afterwards and did not agree.

Abu Sitta insists that all refugees must be allowed to return to Israel, even if they are to be settled in the Negev desert. I do not see the practical logic in this.

I have had hundreds of discussions about solutions with Palestinians, from Yasser Arafat down to people in the refugee camps. The great majority nowadays would sign a formula that seeks a "just and agreed solution of the refugee problem" – "agreed" includes Israel.

This formula appears in the "Arab Peace Plan" devised by Saudi Arabia and officially accepted by the entire Muslim world.

How would this look in practice? It means that every refugee family would be offered a choice between actual return and adequate compensation.

Return – where? In a few extraordinary instances, their original village still stands empty. I can imagine some symbolic reconstruction of such villages – say two or three – by their former inhabitants.

An agreed number must be allowed to return to the territory of Israel, especially if they have relatives here, who can help them to strike roots again.

This is a hard thing for Israelis to swallow – but not too hard. Israel already has some 2 million Arab citizens, more than 20% of the population. Another – say - quarter million would make no real difference.

All the others would be paid generous compensation. They could use that to consolidate their lives where they are, or emigrate to places like Australia and Canada, which would gladly receive them (with their money).

About 1.5 million refugees live in the West Bank and Gaza. Another large number live in Jordan and are Jordanian citizens. Some still live in refugee camps. For all of them, compensation would be welcome.

Where will the money come from? Israel must pay its share (at the same time reducing its huge military budget). The world organizations will have to contribute a large part.

Is This feasible? Yes, it is.

I dare say more: if the atmosphere is right, it is even probable. Contrary to Begin's belief in texts written today by demagogues to serve today's purposes, once the process starts rolling, a solution like this – more or less – is almost unavoidable.

And let's not forget for a moment: these "refugees" are human beings.

Unfortunately, his political views are far less likeable. They are much more extreme than even the acts of his father. The father, after leading the Irgun, sat down and made peace with Anwar al-Sadat of Egypt. Ze'ev is closer to Golda Me'ir, who ignored Sadat's peace overtures and led us into the disastrous Yom Kippur war.

Begin jr. is a strict follower of the "revisionist" Zionist creed founded by Vladimir Ze'ev Jabotinsky. One of the characteristics of this movement has always been the importance it gave to written texts and declarations. The labor movement, headed by David Ben-Gurion, didn't give a damn about words and declarations and respected only "facts on the ground".

Last week, Ze'ev Begin wrote one of his rare articles. Its main purpose was to prove that peace with the Palestinians is impossible, a pipe-dream of Israeli peace-lovers (Haaretz 9.10). Quoting numerous Palestinian texts, speeches and even schoolbooks, Begin shows that the Palestinians will never, never, never give up their "Right of Return".

Since such a return would entail the end of the Jewish State, Begin asserts, peace is a pipe dream. There will never be peace. End of story.

A Similar point is made by another profound thinker, Alexander Jakobson, in another important article in Haaretz (9.26). It is directed against me personally, and its headline asserts that I am "True to Israel, but Not to the Truth". It accuses me of being tolerant towards the BDS movement, which is out to put an end to Israel.

How does he know? Simple: BDS confirms the Palestinians' "Right of Return", which, as everybody knows, means the destruction of the Jewish State.

Well, actually I object to BDS for several reasons. The movement to which I belong, Gush Shalom, was the first (in 1997) to declare a boycott of the settlements. Our aim was to separate the Israeli people from the settlements. The BDS (Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions) movement, by boycotting all of Israel, achieves the opposite effect: it pushes the Israeli people into the arms of the settlers.

I also don't like to call on people to boycott me.

But of all the points in the BDS platform, the one that bothers me the least is the demand that the State of Israel recognize the Palestinians' Right of Return. It is simply ridiculous. Not in a thousand years will the BDS compel Israel to do so. So why bother?

Let' Us First throw some light on the issue.

When the British withdrew from Palestine in 1948, there were in the country between the Mediterranean and the Jordan about 1.2 million Arabs and 635,000 Jews. By the end of the war that ensued, some 700,000 Arabs had fled and/or were driven out. It was a war of what was (later) called "ethnic cleansing". Few Arabs were left in the territory conquered by Jewish arms, but it should be remembered that no Jews at all were left in the territory conquered by Arab arms. Fortunately for our side, the Arabs succeeded in occupying only small slices of land inhabited by Jews (such as the Etzion bloc, East Jerusalem et al.), while our side conquered large, inhabited territories. As a combat soldier, I saw it with my own eyes.

The Arab refugees multiplied by natural increase, and today number about 6 million. About 1.5 million of them live in the occupied West Bank, about a million in the Gaza Strip, the rest are dispersed in Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and all over the world.

Would they all come back, if given the opportunity? Let us consider this.

Years Ago, I had a unique experience.

I was invited to give a lecture in New York. To my pleasant surprise, in the front row I saw a good friend of mine, the young Arab poet Rashid Hussein. Rashid was born in a village near Nazareth. He begged me to come and visit him in his New Jersey apartment.

When I arrived, I was flabbergasted, The small apartment was crowded with people – Palestinian refugees of all kinds, young and old, men and women. We had a long and extremely emotional discussion on the refugee issue.

When we drove home, I told my wife: "You know what I felt? That only a few of them really care to return, but that all of them were ready to die for their right to return!"

Rachel, a very keen observer, replied that she had the same impression.

Today, Dozens of years later, I am convinced that this basic truth is still valid: there is a huge difference between the principle and its implementation.

The principle cannot be denied. It belongs to the individual refugee. It is safeguarded by international law. It is sacred.

Any future peace treaty between the state of Israel and the State of Palestine will have to include a paragraph saying that Israel affirms in principle the Right of Return of the Palestinian refugees and their descendants.

No Palestinian leader could possibly sign a treaty that does not include this clause.

Only after this obstacle has been removed from the table, can the real discussion about the solution start.

I can imagine the scene: after agreement has been reached on this at the peace conference, the chairperson will take a deep breath and say, "Now, friends, let's get to the real issue. How shall we solve the refugee problem in practice?"

The six million Palestinian refugees constitute six million individual situations. There are many categories of refugees. No single solution can apply to all.

There are many refugees – perhaps most of them - who during the last 50 years have built for themselves a new life in another country. For these, the right of return is – well – a principle. They would not dream of going back to their ancestral village, even if it were still there. Some of them are well-to-do, some are rich, some very rich.

One of the richest is my friend (may I call you so?) Salman Abu Sitta, who started life as a barefoot boy in the Negev, fled in 1948 with his family to Gaza and later became an immensely successful contractor in Britain and the Gulf. We met at a peace conference, had a long and emotional private dinner afterwards and did not agree.

Abu Sitta insists that all refugees must be allowed to return to Israel, even if they are to be settled in the Negev desert. I do not see the practical logic in this.

I have had hundreds of discussions about solutions with Palestinians, from Yasser Arafat down to people in the refugee camps. The great majority nowadays would sign a formula that seeks a "just and agreed solution of the refugee problem" – "agreed" includes Israel.

This formula appears in the "Arab Peace Plan" devised by Saudi Arabia and officially accepted by the entire Muslim world.

How would this look in practice? It means that every refugee family would be offered a choice between actual return and adequate compensation.

Return – where? In a few extraordinary instances, their original village still stands empty. I can imagine some symbolic reconstruction of such villages – say two or three – by their former inhabitants.

An agreed number must be allowed to return to the territory of Israel, especially if they have relatives here, who can help them to strike roots again.

This is a hard thing for Israelis to swallow – but not too hard. Israel already has some 2 million Arab citizens, more than 20% of the population. Another – say - quarter million would make no real difference.

All the others would be paid generous compensation. They could use that to consolidate their lives where they are, or emigrate to places like Australia and Canada, which would gladly receive them (with their money).

About 1.5 million refugees live in the West Bank and Gaza. Another large number live in Jordan and are Jordanian citizens. Some still live in refugee camps. For all of them, compensation would be welcome.

Where will the money come from? Israel must pay its share (at the same time reducing its huge military budget). The world organizations will have to contribute a large part.

Is This feasible? Yes, it is.

I dare say more: if the atmosphere is right, it is even probable. Contrary to Begin's belief in texts written today by demagogues to serve today's purposes, once the process starts rolling, a solution like this – more or less – is almost unavoidable.

And let's not forget for a moment: these "refugees" are human beings.

Published on November 16, 2017 13:42

China: Collective Resistance Against iSlavery

Gabriel Levy reviews a book on the world of digital technology.

When 15 young workers jumped or fell from the upper floors of Foxconn’s factories in China in five months of 2010 – 13 of them to their deaths – it made international headlines. People across the world felt outrage at the oppressive working conditions in which iPhones and other high-tech products are made.

Much less well-publicised were the collective resistance movements that flowered at Foxconn and other big Chinese factories in the years following the “Suicide Express”.

In April 2012, 200 Foxconn employees at Wuhan took pictures of themselves on the factory rooftop, and circulated them on social media, along with threats to jump if the company kept ignoring their demand for a wage increase. The company backed down.

This action “differ[ed] qualitatively from individual acts of suicide. Instead, it became a collective behaviour that successfully pressurised Foxconn to increase wages”, the Hong Kong-based activist and university teacher Jack Linchuan Qiu writes in Goodbye iSlave (p. 134).

Qiu describes a world – our world – in which the latest technological devices are made by workers who are subject to dehumanising super-exploitation, and are also used by those workers in organising collective resistance to their conditions.

The main focus of the book is Foxconn, the world’s largest electronics manufacturer. Its workforce of 1.4 million, mostly in China, make most i-products for Apple – including iPads, iPhones, iMacs and MacBooks – and devices for HP, Dell, Nokia, Microsoft, Sony, Cisco, Nintendo, Intel, Motorola, Samsung, Panasonic, Google, Amazon and others.

Qiu describes how, after the slew of Foxconn suicides in 2010, the Chinese state – which had always, at central and local level, supported and encouraged the company’s bosses – felt compelled to act.

The authorities sent an investigation team to Foxconn Shenzhen. Its findings, leaked to the press by a trade union official, were that Foxconn workers were being compelled to do up to 100 hours of overtime a month, while the legal maximum was 36 hours; and that the company’s “semi-militarised management system” put too much pressure on workers, both when they were at the factory and when they were off duty (p. 126).

The friction between the authorities and Terry Guo, the multi-millionaire owner of Foxconn and a Chinese media darling, was real enough – but, as I understand it, was aimed at containing and dampening worker resistance at the giant factories.

If that was the idea, it didn’t work. Foxconn workers found new ways of fighting back , and students and others in China found ways to build solidarity.

Resistance to, and with, smartphones

Qiu argues that collective resistance in the aftermath of the “Suicide Express” (that is, in 2011-14) took different forms from earlier workers’ movement in China, partly because a new generation of workers were at the fore, and partly because they deployed the latest technology.

This new generation were migrants from the countryside, who were “less united, confrontational and militant compared with their elders in state-owned enterprises and the rural villages”, Qiu writes (p. 132). “While those of older age still remember and try to continue practising Maoist politics after they are laid off or facing illegal land grabs, young workers are much more individualistic, consumeristic and prone to seductions leading toward manufactured iSlavery [i.e. work in the high-tech sector].”

There were instances of collective violence in 2012-13 – but these often took the form of “in-fights among employees of different regional and/or ethnic identities and across internal divisions of labour, rather than organised against the ruling elite or the factory itself”. Examples included riots in Foxconn Taiyuan in September 2012 (Sha’anxi guards versus Henan workers), Foxconn Zhengzhou in October 2012 (assembly line workers versus quality-control employees) and Foxconn Yantai in September 2013 (Guizhou versus Shandong workers), Qiu writes.

Against this background, the use of poetry, folk songs, music, theatrical performance and online videos had played a positive and unifying role, Qiu argues. These “alternative expressions, social networking and cultural formation” are “worker generated content (WGC)” for digital media, that is “beyond the scope of user-generated content (UGC) […] which is governed by corporate goals and/or the logic of state surveillance.”

Just as Africans used singing and dancing on slave ships and plantations in the 19th century as “spiritual and poetic, gratifying and powerful” means of defiance, so millions of Chinese workers, in an age of inexpensive digital media – especially affordable camera phones, mobile internet and social networking – have found means of “self-expression and participation in public discussion” on an unprecedented scale.

There is a parallel in the USA, Qiu argues, with the smartphone videos of police brutality, shared through social media, that initiated widespread mobilisation in 2014-15 by African Americans against state oppression.

He gives examples of mobilisation using networked technology, in addition to the collective suicide threat mentioned above, including:

■ A small-scale protest at Foxconn Shenzhen in January 2014 that “went viral via Weibo [a social networking site] among workers in different parts of China. Following each other’s Weibo accounts, they discussed overtime wages in different Foxconn facilities across the nation, the usefulness in appealing to labour unions, and ways to bring more public attention to their collective cause. All the conversations were in the public domain and easily retrievable” (p. 134).

■ A campaign led by grassroots workers and their families to protect Tongxin Experimental Elementary School in a migrant workers’ community on the outskirts of Beijing, which Qiu characterised as “collective activism with empowerment” (p. 138).

■ The use of photographs, videos and text messages to publicise high-profile cases, such as that of Zhang Tingzhen, a Foxconn worker injured on the job, or the Tiny Grass Workers Cultural Home, a community group that were forcibly evicted. Here there was “collective activism without empowerment” (p. 138).

■ Individuals who shared grievances, or demands, via social media, to great effect. An example was Zhang Jun, a worker-activist “who used high-impact videos during the Ole Wolff strike of 2009, resulting in China’s first independent workplace union born out of an industrial action.” This, Qiu writes, was “individual activism with an empowerment effect” (p. 139).

Qiu does not suggest that any medium of communication is a replacement for, or alternative to, collective discussion and action. Rather he argues that the form of action taken, collectively or individually, is changing in a country of 688 million internet users (in December 2015), of which 620 million rely on mobile access.

Digital media has been diffused among working-class communities “in the seething context of increasing social unrest”, and successive types of network used to evade and subvert repeated attempts at state censorship (p. 147).

Since 2014 Chinese workers have repeatedly deployed digital media on their picket lines; “these digital tools have been added to the toolkit of working-class struggles against iSlavery”; no economic sector has been left untouched by this use of digital media for “collective empowerment”.

Another significant initiative came from students and teachers at 20 universities in mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong, who set up a joint investigative team to collect and publish information on labour conditions at Foxconn and other companies. Between 2010 and 2015 they issued four major reports on Foxconn. (See the Students and Scholars Against Corporate Misbehaviour web site. Here are reports on Foxconn and other companies.)

Qiu himself participated in the 20-university team, and devotes a chapter of Goodbye iSlave to details of working conditions at Foxconn, and reflects on that experience. Qiu describes the impunity with which the company hires and fires; the illegal and inhuman methods it uses to prevent workers who want to leave of their own accord from doing so; and the bullying and violence used by management and security hierarchies.

Workers and slaves

The title of Goodbye iSlave is not just a slogan. Qiu argues that workers at Foxconn and other big Chinese manufacturers are slaves in both historical and legal senses. He starts with some telling analogies – of young women migrant workers of today, with women slaves in the past; and of the nets that 18th-century slave traders used to prevent captive Africans from jumping off their ships to their deaths in the Atlantic, with the “safety nets” installed by Foxconn after the suicides of 2010.

A central slave-like quality in the labour relations at Foxconn was, until 2010, the systematic social isolation of migrant workers. They were billeted in dormitories separate from friends and from those who travelled from the same rural communities.

Anti-suicide nets at Foxconn (above) and on an 18th-century slave ship (top). Pictures from Goodbye iSlave communities.

Anti-suicide nets at Foxconn (above) and on an 18th-century slave ship (top). Pictures from Goodbye iSlave communities.

“Separation and isolation are among the most quintessential experiences of being a dehumanised slave”, Qiu argues (p. 71). “This was true for African slaves centuries ago as much as it was for Chinese workers who had to live under the dormitory labour regime of Foxconn. Although there are notable differences in the degree and methods of coercion, the origin of such atomisation was the same: essentially, these are efforts to structure a worker’s life – not just work, but life in the holistic sense, 24/7, throughout the year – for the goal of profit maximisation.”

I was convinced about the all-encompassing and dehumanising character of labour practices, but not so much by the analogy with African slaves, who were the property of their masters. Many types of “free” labour under capitalism have, through history, included aspects of slave-like comprehensive coercion and dehumanisation of the sort that Qiu mentions. There is a continuum between slavery and “free” labour; there are grey areas; there is no neat divide.

In fact Qiu quotes (p. 39) the Marxist writers Karl Heinz Roth and Marcel van der Linden, who argued that “the historical reality of capitalism has featured many hybrid and transitional forms between slavery and ‘free’ wage-labour. Moreover, slaves and wage-workers have repeatedly performed the same work in the same business enterprise.” That way of looking at it works well for me.

Qiu acknowledges the differences between types of labour (which made me still more doubtful about the usefulness of categorising Chinese electronics workers as slaves). Twenty-first century capitalism, in contrast to 18th century European capitalism, no longer relies on “brute force, intimidation and coercive measures of the law”, he writes (p. 35). Rather it uses a “hegemonic cultural regime” to stimulate market growth.

“There has to be a newfangled regime of (servile) consumption to match the marvellous regime of miraculous (slave) productivity. The goal of this new hegemonic system is to generate a new culture, even a new religion of consumerism, an indispensable pillar of capitalist world-economy.”

Yes. The creation of consumers’ “want” (or “need”) for smartphones is the other side of the coin of the coercion and exploitation used to produce the smartphones.

What we might learn

There is much for militants in Europe and north America to learn here. In terms of sheer scale, these events in the cradle of modern manufacturing dwarf many of the movements that we have participated in. These movements face a combination of a treadmill of capitalist production in the “workshop of the world” and ruthless Stalinist dictatorship. Many of them are first- or second-generation migrants from the countryside, in contrast to European workers, most of whom have lived for several generations in an urban world of wage labour exploitation.

In part due to language problems, accurate information about social and labour movements in China is hard to get. Jack Linchuan Qiu’s book makes a massive contribution to bridging that gap. GL, 23 October 2017.

■ Jack Linchuan Qiu’s university web page

■ A video of Jack Linchuan Qiu addressing a meeting last month in London, organised by Breaking the Frame. (I went to the meeting and bought a copy of Goodbye iSlave there. I am glad to say that all the royalties go to a campaign against exploitative labour conditions in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where coltan used in smartphones is mined, for export to China for use in factories such as Foxconn.)

■ More about technology on People & Nature: Interrogating digital capitalism … The Lucas plan and the politics of technology … I have seen the techno-future and I am not so sure it works.

Jack Linchuan 2016. Goodbye iSlave : A Manifesto For Digital Abolition Publisher: University of Illinois Press. ISBN-13: 978-0252040627

Gabriel Levy blogs @ People And Nature.

When 15 young workers jumped or fell from the upper floors of Foxconn’s factories in China in five months of 2010 – 13 of them to their deaths – it made international headlines. People across the world felt outrage at the oppressive working conditions in which iPhones and other high-tech products are made.

Much less well-publicised were the collective resistance movements that flowered at Foxconn and other big Chinese factories in the years following the “Suicide Express”.

In April 2012, 200 Foxconn employees at Wuhan took pictures of themselves on the factory rooftop, and circulated them on social media, along with threats to jump if the company kept ignoring their demand for a wage increase. The company backed down.

This action “differ[ed] qualitatively from individual acts of suicide. Instead, it became a collective behaviour that successfully pressurised Foxconn to increase wages”, the Hong Kong-based activist and university teacher Jack Linchuan Qiu writes in Goodbye iSlave (p. 134).

Qiu describes a world – our world – in which the latest technological devices are made by workers who are subject to dehumanising super-exploitation, and are also used by those workers in organising collective resistance to their conditions.

The main focus of the book is Foxconn, the world’s largest electronics manufacturer. Its workforce of 1.4 million, mostly in China, make most i-products for Apple – including iPads, iPhones, iMacs and MacBooks – and devices for HP, Dell, Nokia, Microsoft, Sony, Cisco, Nintendo, Intel, Motorola, Samsung, Panasonic, Google, Amazon and others.

Qiu describes how, after the slew of Foxconn suicides in 2010, the Chinese state – which had always, at central and local level, supported and encouraged the company’s bosses – felt compelled to act.

The authorities sent an investigation team to Foxconn Shenzhen. Its findings, leaked to the press by a trade union official, were that Foxconn workers were being compelled to do up to 100 hours of overtime a month, while the legal maximum was 36 hours; and that the company’s “semi-militarised management system” put too much pressure on workers, both when they were at the factory and when they were off duty (p. 126).

The friction between the authorities and Terry Guo, the multi-millionaire owner of Foxconn and a Chinese media darling, was real enough – but, as I understand it, was aimed at containing and dampening worker resistance at the giant factories.

If that was the idea, it didn’t work. Foxconn workers found new ways of fighting back , and students and others in China found ways to build solidarity.

Resistance to, and with, smartphones

Qiu argues that collective resistance in the aftermath of the “Suicide Express” (that is, in 2011-14) took different forms from earlier workers’ movement in China, partly because a new generation of workers were at the fore, and partly because they deployed the latest technology.

This new generation were migrants from the countryside, who were “less united, confrontational and militant compared with their elders in state-owned enterprises and the rural villages”, Qiu writes (p. 132). “While those of older age still remember and try to continue practising Maoist politics after they are laid off or facing illegal land grabs, young workers are much more individualistic, consumeristic and prone to seductions leading toward manufactured iSlavery [i.e. work in the high-tech sector].”

There were instances of collective violence in 2012-13 – but these often took the form of “in-fights among employees of different regional and/or ethnic identities and across internal divisions of labour, rather than organised against the ruling elite or the factory itself”. Examples included riots in Foxconn Taiyuan in September 2012 (Sha’anxi guards versus Henan workers), Foxconn Zhengzhou in October 2012 (assembly line workers versus quality-control employees) and Foxconn Yantai in September 2013 (Guizhou versus Shandong workers), Qiu writes.

Against this background, the use of poetry, folk songs, music, theatrical performance and online videos had played a positive and unifying role, Qiu argues. These “alternative expressions, social networking and cultural formation” are “worker generated content (WGC)” for digital media, that is “beyond the scope of user-generated content (UGC) […] which is governed by corporate goals and/or the logic of state surveillance.”

Just as Africans used singing and dancing on slave ships and plantations in the 19th century as “spiritual and poetic, gratifying and powerful” means of defiance, so millions of Chinese workers, in an age of inexpensive digital media – especially affordable camera phones, mobile internet and social networking – have found means of “self-expression and participation in public discussion” on an unprecedented scale.

There is a parallel in the USA, Qiu argues, with the smartphone videos of police brutality, shared through social media, that initiated widespread mobilisation in 2014-15 by African Americans against state oppression.

He gives examples of mobilisation using networked technology, in addition to the collective suicide threat mentioned above, including:

■ A small-scale protest at Foxconn Shenzhen in January 2014 that “went viral via Weibo [a social networking site] among workers in different parts of China. Following each other’s Weibo accounts, they discussed overtime wages in different Foxconn facilities across the nation, the usefulness in appealing to labour unions, and ways to bring more public attention to their collective cause. All the conversations were in the public domain and easily retrievable” (p. 134).

■ A campaign led by grassroots workers and their families to protect Tongxin Experimental Elementary School in a migrant workers’ community on the outskirts of Beijing, which Qiu characterised as “collective activism with empowerment” (p. 138).

■ The use of photographs, videos and text messages to publicise high-profile cases, such as that of Zhang Tingzhen, a Foxconn worker injured on the job, or the Tiny Grass Workers Cultural Home, a community group that were forcibly evicted. Here there was “collective activism without empowerment” (p. 138).

■ Individuals who shared grievances, or demands, via social media, to great effect. An example was Zhang Jun, a worker-activist “who used high-impact videos during the Ole Wolff strike of 2009, resulting in China’s first independent workplace union born out of an industrial action.” This, Qiu writes, was “individual activism with an empowerment effect” (p. 139).

Qiu does not suggest that any medium of communication is a replacement for, or alternative to, collective discussion and action. Rather he argues that the form of action taken, collectively or individually, is changing in a country of 688 million internet users (in December 2015), of which 620 million rely on mobile access.

Digital media has been diffused among working-class communities “in the seething context of increasing social unrest”, and successive types of network used to evade and subvert repeated attempts at state censorship (p. 147).

Since 2014 Chinese workers have repeatedly deployed digital media on their picket lines; “these digital tools have been added to the toolkit of working-class struggles against iSlavery”; no economic sector has been left untouched by this use of digital media for “collective empowerment”.

Another significant initiative came from students and teachers at 20 universities in mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong, who set up a joint investigative team to collect and publish information on labour conditions at Foxconn and other companies. Between 2010 and 2015 they issued four major reports on Foxconn. (See the Students and Scholars Against Corporate Misbehaviour web site. Here are reports on Foxconn and other companies.)

Qiu himself participated in the 20-university team, and devotes a chapter of Goodbye iSlave to details of working conditions at Foxconn, and reflects on that experience. Qiu describes the impunity with which the company hires and fires; the illegal and inhuman methods it uses to prevent workers who want to leave of their own accord from doing so; and the bullying and violence used by management and security hierarchies.

Workers and slaves

The title of Goodbye iSlave is not just a slogan. Qiu argues that workers at Foxconn and other big Chinese manufacturers are slaves in both historical and legal senses. He starts with some telling analogies – of young women migrant workers of today, with women slaves in the past; and of the nets that 18th-century slave traders used to prevent captive Africans from jumping off their ships to their deaths in the Atlantic, with the “safety nets” installed by Foxconn after the suicides of 2010.

A central slave-like quality in the labour relations at Foxconn was, until 2010, the systematic social isolation of migrant workers. They were billeted in dormitories separate from friends and from those who travelled from the same rural communities.

Anti-suicide nets at Foxconn (above) and on an 18th-century slave ship (top). Pictures from Goodbye iSlave communities.

Anti-suicide nets at Foxconn (above) and on an 18th-century slave ship (top). Pictures from Goodbye iSlave communities.“Separation and isolation are among the most quintessential experiences of being a dehumanised slave”, Qiu argues (p. 71). “This was true for African slaves centuries ago as much as it was for Chinese workers who had to live under the dormitory labour regime of Foxconn. Although there are notable differences in the degree and methods of coercion, the origin of such atomisation was the same: essentially, these are efforts to structure a worker’s life – not just work, but life in the holistic sense, 24/7, throughout the year – for the goal of profit maximisation.”

I was convinced about the all-encompassing and dehumanising character of labour practices, but not so much by the analogy with African slaves, who were the property of their masters. Many types of “free” labour under capitalism have, through history, included aspects of slave-like comprehensive coercion and dehumanisation of the sort that Qiu mentions. There is a continuum between slavery and “free” labour; there are grey areas; there is no neat divide.

In fact Qiu quotes (p. 39) the Marxist writers Karl Heinz Roth and Marcel van der Linden, who argued that “the historical reality of capitalism has featured many hybrid and transitional forms between slavery and ‘free’ wage-labour. Moreover, slaves and wage-workers have repeatedly performed the same work in the same business enterprise.” That way of looking at it works well for me.

Qiu acknowledges the differences between types of labour (which made me still more doubtful about the usefulness of categorising Chinese electronics workers as slaves). Twenty-first century capitalism, in contrast to 18th century European capitalism, no longer relies on “brute force, intimidation and coercive measures of the law”, he writes (p. 35). Rather it uses a “hegemonic cultural regime” to stimulate market growth.

“There has to be a newfangled regime of (servile) consumption to match the marvellous regime of miraculous (slave) productivity. The goal of this new hegemonic system is to generate a new culture, even a new religion of consumerism, an indispensable pillar of capitalist world-economy.”

Yes. The creation of consumers’ “want” (or “need”) for smartphones is the other side of the coin of the coercion and exploitation used to produce the smartphones.

What we might learn

There is much for militants in Europe and north America to learn here. In terms of sheer scale, these events in the cradle of modern manufacturing dwarf many of the movements that we have participated in. These movements face a combination of a treadmill of capitalist production in the “workshop of the world” and ruthless Stalinist dictatorship. Many of them are first- or second-generation migrants from the countryside, in contrast to European workers, most of whom have lived for several generations in an urban world of wage labour exploitation.

In part due to language problems, accurate information about social and labour movements in China is hard to get. Jack Linchuan Qiu’s book makes a massive contribution to bridging that gap. GL, 23 October 2017.

■ Jack Linchuan Qiu’s university web page

■ A video of Jack Linchuan Qiu addressing a meeting last month in London, organised by Breaking the Frame. (I went to the meeting and bought a copy of Goodbye iSlave there. I am glad to say that all the royalties go to a campaign against exploitative labour conditions in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where coltan used in smartphones is mined, for export to China for use in factories such as Foxconn.)

■ More about technology on People & Nature: Interrogating digital capitalism … The Lucas plan and the politics of technology … I have seen the techno-future and I am not so sure it works.

Jack Linchuan 2016. Goodbye iSlave : A Manifesto For Digital Abolition Publisher: University of Illinois Press. ISBN-13: 978-0252040627

Gabriel Levy blogs @ People And Nature.

Published on November 16, 2017 01:00

November 15, 2017

Gender Segregation Is Humiliating And Damaging

Maryam Namazie slams Gender Segregation. This piece was first published in The Freethinker.

Add caption

Add caption

Segregation was humiliating. Just the reality of signs that said you couldn’t use front doors or you couldn’t use this water fountain implied that you were subhuman … Every time I complied with a sign, I felt like I was acquiescing to my own inhumanity. I felt outraged and hated it. - Diane Nash, a leader of the 1960s US Civil Rights Movement

When the Hezbollah came to segregate the girls from the boys at my school in Iran in 1980 after an Islamic regime took power, I remember wondering what was so wrong with me that I had to be separated from my male friends.

I was only 12 at the time.

I soon learnt that segregation was a “necessity” because girls over the age of nine (considered the age of maturity) are “sources of fitnah“, “temptations that incite men’s lust” eventually leading to adultery (Zina). And that gender segregation “protects” society from “moral decay” and “sex anarchy”.

Better to be segregated, I was told, than to have to be stoned to death for adultery.

I was elated, therefore, when a Court of Appeal found that gender segregation – including in the classroom, corridors, school clubs, play areas and school trips – at Al-Hijrah school in Birmingham was discriminatory.

Given the rise of gender segregation at schools and universities in this country (including at the Rabia School in Luton, Madani school in Leicester, the LSE, Queen Mary University of London as well as Orthodox Jewish schools), the land-mark decision should have far-reaching effects in favour of the rights of minority women and girls in particular. The decision is also a victory against the religious-Right which uses religion in the educational system to police and control women and girls.

The basis for gender segregation (as well as veiling, banning women’s singing, prohibiting hand-shaking with women, male guardianship and so on) is that a woman’s and girl’s place is in the home, that she is lesser than a man or boy and that mixing with her will lead to “corruption”.

In Bas les Voiles , Chahdortt Djavan argues that the psychological damage done to girls from a very young age by making them responsible for men’s arousal is immense and builds fear and feelings of disgust at the female body.

Sayyid Maududi, the founder of Jama’at-i Islami (the Salafis of South Asia that are running some of the mosques, schools and Sharia courts here in Britain) explains why segregation is important in his book Purdah and the Status of Women in Islam :

Sharia courts here in Britain reinforce this point of view. For example Haitham al-Haddad, who was until recently a Sharia judge at the Leyton Sharia council and who testified at the Home Affairs Committee Sharia Councils inquiry (which was by the way quietly closed without any resolution), says on gender segregation:

Those who defend gender segregation as being “separate but equal” ignore the reality that women and men are not equal in any sense of the word. In fact, “one is confined while the other is at large.”

Cultural relativists who would never defend inequality between non-minority women and men or segregation based on race excuse gender segregation because they say it is “voluntary” and a “choice”. Aside from the fact that Islamists use rights language to curtail rights, of course women and girls can sit where they choose. “What is discriminatory”, however, says Algerian sociologist Marieme Helie Lucas “is to assign a place to somebody, whatever that place may be. It says: keep to your place; to women’s place!”

In her witness statement to the Court of Appeal, Pragna Patel, Director of Southall Black Sisters stated:

In a piece entitled “Education and the Muslim Girl”, Saeeda Khanum quotes an interview with Liaqat Hussein from the Council for Mosques, which shows the real aims of gender segregation:

For now though, we should celebrate this important decision. As Pragna Patel of Southall Black Sisters stated:

Add caption

Add captionSegregation was humiliating. Just the reality of signs that said you couldn’t use front doors or you couldn’t use this water fountain implied that you were subhuman … Every time I complied with a sign, I felt like I was acquiescing to my own inhumanity. I felt outraged and hated it. - Diane Nash, a leader of the 1960s US Civil Rights Movement

When the Hezbollah came to segregate the girls from the boys at my school in Iran in 1980 after an Islamic regime took power, I remember wondering what was so wrong with me that I had to be separated from my male friends.

I was only 12 at the time.

I soon learnt that segregation was a “necessity” because girls over the age of nine (considered the age of maturity) are “sources of fitnah“, “temptations that incite men’s lust” eventually leading to adultery (Zina). And that gender segregation “protects” society from “moral decay” and “sex anarchy”.

Better to be segregated, I was told, than to have to be stoned to death for adultery.

I was elated, therefore, when a Court of Appeal found that gender segregation – including in the classroom, corridors, school clubs, play areas and school trips – at Al-Hijrah school in Birmingham was discriminatory.