Anthony McIntyre's Blog, page 1131

July 9, 2018

A Morning Thought (69)

Published on July 09, 2018 00:30

July 8, 2018

Who Are We To Judge People Living In Islamic Countries?

Armin Navabi explains to Scott Jacobsen from Atheist Republic the dangers of moral relativism.

Add caption

Add caption

Scott Douglas Jacobsen: I hear arguments from different people on Islamic countries and people who live in them. Some argue for different standards for different beliefs and groups. If not in an explicit manner, then the implicit understanding in the conversation amounts to different standards for different people. The conversations start with the general question about judgment of people who live in Islamic countries. In these dialogues, the person may respond with a question, “Who are we to judge people living in Islamic countries?”

Armin Navabi: We are all human beings. That is what we all are. Why does care for our fellow human beings have to be dependent on their location? Why does it have to be dependent on where they were born, their race, or how far or how close they are to us? I do not understand the relevance of that. Pain is pain. Happiness is happiness. I believe that it does not matter if somebody is hungry next to you, or if somebody is hungry a thousand kilometers from you. It does not matter if somebody is being oppressed right next to you or if somebody is being oppressed a thousand kilometers from you. That somebody is human. They need your help.

We Are All Connected

The idea of “I can help people who are next to me more than I could help people far away from me” does not exist anymore. We are all connected globally, through the advances in technology, that it is so easy to help other people with little effort and little budget.

Today, you can make a huge difference for people you have never even met or will never even meet. You can make a difference for people, whichever corner of the world they are in now. In fact, you might be able to make more of a difference because you live in a country where you could speak freely.

They Need Your Voice

You live in a country where you could say whatever you want. People living in Islamic countries do not. They do not live in a country where they can speak their minds. That is why you might be able to make a bigger difference in their lives compared to people close to you. They need your voice. Because when they do speak, these people will get prosecuted and go to jail. They lose their freedom. They lose their safety. These are people taken away from their children. There are even people who pay the government for the cost of executing their loved ones.

Arrogance in Freedom

Liberated countries enjoy some or most of these rights: freedom of speech, right to peace, equality, anti-discrimination, men and women are equal, homosexuals should not to be prosecuted for being gay, and for people of the minority to express their views without being punished. The people who are enjoying these rights have no empathy for what the people in Islamic countries are suffering from there. To me, it is arrogant when some people suggest that this is maybe because these are our values but not theirs.

Morally Superior

Because of this, they claim moral superiority for following these values. That people who follow such humanist values are going to enjoy life more, and live a life with more peace and more happiness. Since we are claiming superiority for this, we think we are deserving of these values and other people are not.

Other people might never be able to see that these values are good for them because they weren’t always in the situation where they had these values. Later on, they progressed to adopt these values, but people are denying them on the same grounds. They might say, “We came to these values ourselves. They should do the same thing.” I call bullshit. There is no country, no idea, and no value that has not been influenced by other countries, by other values, by philosophers and thought leaders from different corners of the world. Europe was introduced to its own ancient values through the Arab Empire. If it wasn’t because of the Arab Empire, we would not know how much of those ancient values would have come back from Greek philosophers. They were influenced by foreign countries, foreign philosophers, and foreign thought.

No group of people or country lives in a bubble. Of course, they are going to be influenced by foreign countries. They are going to influence other countries. They are going to be influenced by other countries. There is no way a country could progress in a bubble. They need outside influence as we need outside influence. The world is connected. If that was true a thousand years ago, it is more true today because we are more connected today. If European countries want an enlightenment, because of the influence of foreign countries at that time, are you going to deny foreign influence to these countries today since we are even more connected now?

Moral and Pleasure Matrix

I will say to people who do not agree with these values, to bring on your values and sell your values to these people, but do not deny us the opportunity to come and introduce these values to people that might want them. Compete with us in the market of ideas, compete with us and tell us why your values are better; however, that is not what you are doing. You are telling us, we are not in a position to judge, so we should shut the fuck up. That is the position you are taking. I am saying, if you think our ideas are wrong, bring up better ideas, but do not deny these people the opportunity to choose their ideas. Ideas that we think are better.

If you think we are wrong, introduce them to more ideas, not fewer ideas. That is how you compete with our ideas. That is how you respond to a bad idea. That is how we respond to your shitty backwards barbaric ancient ideas. We do not silence you. We compete with you. If you think our ideas are imperialist, foreign, too liberal, too free, too empty of spiritual guidance, too empty of meaning, too empty of providing purpose to people, then I am sure. If your ideas are better, they are going to do good.

Exploiting Evolution

You should bring your ideas to the public and compete with us. Do not deny the people, who might prefer our values, the opportunity to hear us because you think somebody might take advantage of these ideas for their agenda. Because if that is your argument, then we should stop teaching evolution in Western countries. Because it was not that long ago, when the Nazis took advantage of the evolution of science to sell their agenda and to tell people why we need to stop letting some races spread, some races should be superior. The whole genocide of the Jews. All those gas chambers and crimes were committed by the Nazi Regime. They were based on the truth, based on the misuse of an actual true scientific principle, which is evolution.

If you are looking at how people could misuse something, we should stop teaching evolution in Western countries because we have a history. In fact, you should try to suggest a value to me. I could come up with a way that it could be misused.

Misuse of Human Rights

In fact, if you are worried about the fact that we are talking about human rights being misused by the military/industrial complex to bring war to these countries, why are you not equally concerned about the Islamic values that have been used, time and time again, in history, for killing, for war, for torturing people, and for denying people’s rights? We have more examples of Islamic values being used to do the same thing. Based on the argument, we should deny Muslims the opportunities to spread their ideology because of the history and examples that came from the misuse of it.

You cannot stop telling the truth because of somebody being able to misuse it. Because if you do that, then you cannot say anything. Everybody should stay home and shut the fuck up.

The only way that you could fight the misuse of good ideas is to expose them as misuse of good ideas. Because if you do not compete bad ideas with better ideas, those bad ideas are more easily used, more easily misused, than good ideas. If your values are better values, then any misuse of it is a misrepresentation and is another inferior value that you should fight for rather than it. When we say these values are superior and you say, “Well, who are you to say?” You could still say that about any claim. I could say, “Who are you to say? Who am I to say?” Let us say your claim is we should not interfere in other people’s countries, who are you to say we should not interfere in other people’s countries?

Challenge Your Ideas

The point of bringing your ideas out there is to challenge them. If you go around the argument and look at the person who is making the argument and you think that they do not deserve to make such argument, then you are making a judgement about the person, whether or not they are deserving to make an argument. Now, you are in that position where we can ask the same from you: who are you to deny this person making the argument?

Another thing is when people say, “Oh, Christianity is the same. It is as bad here. Look at the people. Look at how many police are killing black people or look how Christianity is also barbaric. Ancient ideology that could be as harmful.”

To that, I say, “Fuck you.” I am not talking about those things. I am talking about something else. An

example: Imagine if you have a fundraiser for cancer. You are trying to raise money to fund research for cancer. You want to fight cancer, and then people come in and start shouting. They say, “What about

AIDS? Why are you not talking about AIDS? AIDS is a disease too. AIDS is also killing people. You guys do not care about AIDS!” What would I do? I would probably kick these people out. AIDS is bad. Yes! However, we are talking about cancer because we are talking about the problems of cancer. That does not mean we are denying that AIDS is also a problem.

However, you are not helping by shifting the discussion to something that this fundraiser is not fighting for now. You are not helping, and fuck you for making everything about you. Because what you are doing is you are taking part in the Oppression Olympics. You think that if the conversation is not about the things that attacks your people or the things that have affected your life, then it is not worth talking about now. If you have been hurt by Christianity or by racism in the US, then when we come and say, “Islam is hurting people,” you are saying, “No, let us pay attention to this.” That makes you self-centered because you cannot stand it when other people are talking about being victims of something else other than what concerns you. You cannot stand people who are bringing awareness to something that you or the people around you are not victims of. If that is the case, then you are selfish and arrogant. However, some people might say this cancer and AIDS example does not make sense because Islam and Christianity have the same root.

Religion As A Whole

This is why we always want to say that we should not talk about Islam. Talk about religion as a whole. Okay, let me add to my example. Let us say we had a fundraiser about pancreatic cancer and then somebody came and said, “Skin cancer is a problem too. Why are you not talking about skin cancer?”

Is that close enough for you?

Sometimes, it makes sense to focus on a specific problem, even if it has similarities with other problems. Different problems manifest themselves in different ways. They harm people in different ways. They have different answers.

It makes sense to focus on a certain problem. Sometimes, it makes sense to look at it as a whole. However, it does not make sense when you always try to shift the attention to a different category when we are focusing on another one. It does not make sense because you are not helping. We are having a discussion about a certain topic and all you are doing is coming and saying, “pay attention to the problem that I care about.” That is what you are doing.

Better Than Most

The obsession for a certain issue might be for different reasons. It could be because you were hurt. It

might be because you know more about a particular topic. It might be simply because you care more about a certain issue. Who cares? At least, you are talking about a problem, which makes you better than most people.

For example, if somebody is going out there and rescuing dogs, I am not going to tell them, “What the fuck do you have against cats? Why are you not rescuing cats? Are other animals not good enough for you? Do they not deserve saving?”

This person maybe cares about dogs. Maybe, he is passionate about dogs. However, the fact that he is

rescuing dogs. He might be doing more than most people. Do you know what you say to somebody who is going out there and rescuing dogs? You say, “Thank you.” That is what you say to that person.

For example, let us say somebody says to me, “Why are you focused on Islam? Why not all religions?” I tell them, “Why are you so focused on other religions? Why not all dogma?” They might say, “Okay, all dogma.”

I am like, “Why are you focusing on all dogma? Why are you not focusing on all bad ideas? Does a bad idea have to be a dogma for you to focus on it?” Then they go, “Okay, all bad ideas.” I am like, “Bad ideas? What about other bad things? Does something have to be an idea for you to attack it? Diseases are not ideas. Why are you focusing on bad ideas?”

“Alright, so let us be more general, bad things are bad. Good things are good. Is that general enough for you? Is that good? How helpful is that? How helpful of a claim that is… bad things are bad?” You cannot get more general than that.

General Activism

Some people prefer to look at it more generally. Others might want to look at it more focused in a more specific situation. For example, there is a certain village in the Philippines, where the people need help now. This person wants to specifically focus on this group of people. People who do not have access to water. It is focused. Nobody will go to this person and be like, “Why are you focusing on that specific village?” That is incredibly focused, but I am sure most people will say, “Congratulations, that is good. Thank you for helping these people.”

But when it comes to Islam, many people, atheists especially, say, “Why are you focusing on Islam?” I do not think it is because their problem is that you are being too focused. I think they feel a certain amount of bigotry if you are focused on Islam because they do not say that about any other form of activism if it is focused on anything.

Have you ever heard anybody say that about any other form of activism? It looks ridiculous. Let us say somebody is focusing on the environment in Iran. Nobody comes to him and says, “Why do you not care about the environment in Iraq?”

Pushed Back for Bigotry

Every form of activism gets this bigotry pushback. However, this specific claim that you are being too focused is either regarding Islam or nationalism. For example, if Americans are focusing on other countries, they might get accused on why are you not focusing on problems at home.

I know a lot of people who are nationalistic and anti-globalist do not like this. However, I do not understand it. Why do we have to care about a certain group of people because they happened to be born on this side of the border instead of on the other side of the border? Is that good criteria for us to start caring about somebody? Why is that? What makes this so special? With this line in the sand, all of the sudden the person that is born on this side of it matters more?

Western Values

Another thing, I want to address Western values. The name: “Western values.” The reason why it is called Western values is because it first happened in Western countries. The fact that these values were adopted more in Western countries is a historical accident. Because they are named, “Western values,” now, that does not mean that the West should own these values. The West does not own women’s rights. The West does not own human rights. The West does not have a monopoly over not discriminating against gay people. The West does not have a monopoly on secularism. The West does not have ownership over freedom of speech.

The fact people are accusing us of bigotry because we are suggesting that these values should be global and introduced globally, you are being the bigots. You are claiming ownership over some values because you happened to historically come across it -- before the rest of the world. You are the people unwilling to share. You think that this is good for you, but it is not good for other people. Why is it not good for other people? What makes them so different from us that it works for you but not for them?

Western Superiority

You are the people claiming superiority. What is it about values that make somebody claim ownership over them? Why can we not introduce these values? Why can we not promote these values? It has been introduced, but we could promote it even more. Why can we not promote them? Could somebody use it to attack these countries? Reality check: somebody is using other values to oppress women.

If we go back to arguments people use when you are talking about Muslims and Islamic ideology, you are not looking at the main threat in the world. You are not looking at the main powers at play, at the destruction and the harm that they cause.

You have to see who is in control and not look at these minority Muslims in our Western countries. You have to make the difference where it matters the most now. Those are the ideas. The values that are being used to oppress people in foreign countries and in their countries by these major superpowers in the West.

I tell them that is a narrow way of looking at it because where I come from Islam is in power. You are underestimating Islam as a major superpower when you think about it that way. Islam is the fastest growing religion in the world. Islam is going to become the number one main ideology in the world soon.

Islam Colonization

Islam is dominating not lands but minds. Islam is used to rule over people and to oppress people. Islam has been used to colonize people. Do you think white people are the only people that can colonize?

Islam has been used for colonization way before the British discovered what that even means and that it is even an option. It is okay if it happens voluntarily. If people are adopting other people’s cultures or ideas or values voluntarily, that is not colonizing them. We are asking for these other values and ideas to be heard and considered rather than suppressed or silenced.

We asking for a seat at the table, at every table. I am not talking about a seat at a table talking about humanism and secularism in the United States, in the United Kingdom, in Canada, or in France. I am talking about a seat at a table in Iran, in Bangladesh, in Saudi Arabia, in Malaysia, in Indonesia, in Pakistan.

We demand a seat at a table. We are going to get it. if you think that that is us imposing our values on other people, fuck you. Because you are enjoying the benefits of these values, somebody at some point in your history was told that these values are not for your country. They did not stay silent. They sacrificed their lives. They sacrificed their safety. They sacrificed their comfort for you to enjoy that today. People are doing these things in Iran, in Saudi Arabia, and in Bangladesh. They are suffering for it.

Moral Cowardice

You are a moral coward for thinking that it is morally wrong for us to voice our feelings on the killing of secular bloggers in Bangladesh. Do you think it is not right for us to judge? Do you think you are not in a position to judge? To judge whether women having less inheritance rights in government, as a witness in court, on what they wear, where they go, what jobs they get, who they talk to, do you think that you are not in a position to make a moral judgment on that? That makes you a moral coward.

But what is moral or not? If you are making that judgement based on how different sets of actions

influence people’s well-being, then there is always a right answer and a wrong answer. There are many good answers and many bad answers. It does not take a genius to see that hanging gay people is not good for the well-being of the society. If you think that you are not in a position to make a moral judgment for other countries, I want you to tell me what you would say to the person that is about to be hanged because they are gay.

Go ahead and tell that to that person right before they are being hanged, say, “This is not

that bad. In my country it is bad, but here, this is your culture, so shame on you for being gay. If

you were in the United Kingdom, I would be marching for gay pride and being gay and proud, but here it is a different country. So, fuck you, fuck your gay ass, you deserve being hanged here.”

For The People in Islamic Countries

All the people who are in jail in Iran or Saudi Arabia; all the bloggers who died trying to spread secularism and humanism; all the people in Malaysia who after the government came out and said that they need to hunt down atheists; on behalf of those people, all the people that were burned or tortured for accusations of desecrating the Quran in Pakistan; on behalf of all those people, I want to say, “Fuck you to whoever says that it is their culture and who are we to judge and ask, ‘What’s right for them?’” On behalf of every woman that suffered from Islam; on behalf of every homosexual person that suffered in Islam; and on behalf of anybody that dares speak against Islam and paid the consequences for it, I want to say, “Fuck you” to whoever says, “Who are we to judge?”

Enlightenment for All

The Western countries went through the Enlightenment. Now we want this for other countries as well. We want the same enlightenment values. We want to fight for those values. If you are arrogant enough to want to deny the rest of us the same process, if you are not going to help, then stay out of our way. It is interesting a lot of people come and tell me, “Armin, why are you saying these things? That is our country. It has nothing to do with our country. That is Iran.” I almost, almost want to say, “Mother fuckers, I am from Iran.” However, I do not think that is even relevant because I think you should not need to be from there for you to care about them.

Situation in Yemen

Who do I care more about right now than even the people in Iran? I care more about the people in Yemen. If I could speak Arabic, I would have been tweeting more about the situation that is happening in Yemen because they are suffering more than the people in Iran. The fact that you think we have to be from there to care about them makes no sense to me. However, if you think that, and if you do not want to be part of the solution, and if you do not want to lend a voice to people that need you to lend them a voice, the people that are voiceless. The people that cannot speak for themselves.

If you are not going to use your platform to help them, then stay out of our way because we are going to keep doing that. We are going to keep doing that. It does not matter how many times you call us a bigot. We are going to keep fighting for those people.

If you think they need to do it themselves, then fuck you again because it would be much faster and much easier if we could help them out. Because we enjoy the freedom of speech here. We enjoy some security. We could bring more attention to their problems, to their suffering. We could help. We could help. They need our help. They are asking for our help. For you to deny that to them because you think they do not deserve it, it is selfish. It is selfish to judge your life by a different standard than what you are judging their lives by.

So, who are we to judge how people in Islamic countries live? To that I say, “That is the wrong question. The right question is, “Who do you have to be to remain silent?” The answer to that is, “You have to be a monster.” You have to be a monster to have seen such crimes being done against your fellow human beings and judge it by a different standard than what you would have done if it was happening in your own backyard.

About Atheist Republic

About Atheist Republic

Follow Atheist Republic on Twitter @AtheistRepublic

Add caption

Add captionScott Douglas Jacobsen: I hear arguments from different people on Islamic countries and people who live in them. Some argue for different standards for different beliefs and groups. If not in an explicit manner, then the implicit understanding in the conversation amounts to different standards for different people. The conversations start with the general question about judgment of people who live in Islamic countries. In these dialogues, the person may respond with a question, “Who are we to judge people living in Islamic countries?”

Armin Navabi: We are all human beings. That is what we all are. Why does care for our fellow human beings have to be dependent on their location? Why does it have to be dependent on where they were born, their race, or how far or how close they are to us? I do not understand the relevance of that. Pain is pain. Happiness is happiness. I believe that it does not matter if somebody is hungry next to you, or if somebody is hungry a thousand kilometers from you. It does not matter if somebody is being oppressed right next to you or if somebody is being oppressed a thousand kilometers from you. That somebody is human. They need your help.

We Are All Connected

The idea of “I can help people who are next to me more than I could help people far away from me” does not exist anymore. We are all connected globally, through the advances in technology, that it is so easy to help other people with little effort and little budget.

Today, you can make a huge difference for people you have never even met or will never even meet. You can make a difference for people, whichever corner of the world they are in now. In fact, you might be able to make more of a difference because you live in a country where you could speak freely.

They Need Your Voice

You live in a country where you could say whatever you want. People living in Islamic countries do not. They do not live in a country where they can speak their minds. That is why you might be able to make a bigger difference in their lives compared to people close to you. They need your voice. Because when they do speak, these people will get prosecuted and go to jail. They lose their freedom. They lose their safety. These are people taken away from their children. There are even people who pay the government for the cost of executing their loved ones.

Arrogance in Freedom

Liberated countries enjoy some or most of these rights: freedom of speech, right to peace, equality, anti-discrimination, men and women are equal, homosexuals should not to be prosecuted for being gay, and for people of the minority to express their views without being punished. The people who are enjoying these rights have no empathy for what the people in Islamic countries are suffering from there. To me, it is arrogant when some people suggest that this is maybe because these are our values but not theirs.

Morally Superior

Because of this, they claim moral superiority for following these values. That people who follow such humanist values are going to enjoy life more, and live a life with more peace and more happiness. Since we are claiming superiority for this, we think we are deserving of these values and other people are not.

Other people might never be able to see that these values are good for them because they weren’t always in the situation where they had these values. Later on, they progressed to adopt these values, but people are denying them on the same grounds. They might say, “We came to these values ourselves. They should do the same thing.” I call bullshit. There is no country, no idea, and no value that has not been influenced by other countries, by other values, by philosophers and thought leaders from different corners of the world. Europe was introduced to its own ancient values through the Arab Empire. If it wasn’t because of the Arab Empire, we would not know how much of those ancient values would have come back from Greek philosophers. They were influenced by foreign countries, foreign philosophers, and foreign thought.

No group of people or country lives in a bubble. Of course, they are going to be influenced by foreign countries. They are going to influence other countries. They are going to be influenced by other countries. There is no way a country could progress in a bubble. They need outside influence as we need outside influence. The world is connected. If that was true a thousand years ago, it is more true today because we are more connected today. If European countries want an enlightenment, because of the influence of foreign countries at that time, are you going to deny foreign influence to these countries today since we are even more connected now?

Moral and Pleasure Matrix

I will say to people who do not agree with these values, to bring on your values and sell your values to these people, but do not deny us the opportunity to come and introduce these values to people that might want them. Compete with us in the market of ideas, compete with us and tell us why your values are better; however, that is not what you are doing. You are telling us, we are not in a position to judge, so we should shut the fuck up. That is the position you are taking. I am saying, if you think our ideas are wrong, bring up better ideas, but do not deny these people the opportunity to choose their ideas. Ideas that we think are better.

If you think we are wrong, introduce them to more ideas, not fewer ideas. That is how you compete with our ideas. That is how you respond to a bad idea. That is how we respond to your shitty backwards barbaric ancient ideas. We do not silence you. We compete with you. If you think our ideas are imperialist, foreign, too liberal, too free, too empty of spiritual guidance, too empty of meaning, too empty of providing purpose to people, then I am sure. If your ideas are better, they are going to do good.

Exploiting Evolution

You should bring your ideas to the public and compete with us. Do not deny the people, who might prefer our values, the opportunity to hear us because you think somebody might take advantage of these ideas for their agenda. Because if that is your argument, then we should stop teaching evolution in Western countries. Because it was not that long ago, when the Nazis took advantage of the evolution of science to sell their agenda and to tell people why we need to stop letting some races spread, some races should be superior. The whole genocide of the Jews. All those gas chambers and crimes were committed by the Nazi Regime. They were based on the truth, based on the misuse of an actual true scientific principle, which is evolution.

If you are looking at how people could misuse something, we should stop teaching evolution in Western countries because we have a history. In fact, you should try to suggest a value to me. I could come up with a way that it could be misused.

Misuse of Human Rights

In fact, if you are worried about the fact that we are talking about human rights being misused by the military/industrial complex to bring war to these countries, why are you not equally concerned about the Islamic values that have been used, time and time again, in history, for killing, for war, for torturing people, and for denying people’s rights? We have more examples of Islamic values being used to do the same thing. Based on the argument, we should deny Muslims the opportunities to spread their ideology because of the history and examples that came from the misuse of it.

You cannot stop telling the truth because of somebody being able to misuse it. Because if you do that, then you cannot say anything. Everybody should stay home and shut the fuck up.

The only way that you could fight the misuse of good ideas is to expose them as misuse of good ideas. Because if you do not compete bad ideas with better ideas, those bad ideas are more easily used, more easily misused, than good ideas. If your values are better values, then any misuse of it is a misrepresentation and is another inferior value that you should fight for rather than it. When we say these values are superior and you say, “Well, who are you to say?” You could still say that about any claim. I could say, “Who are you to say? Who am I to say?” Let us say your claim is we should not interfere in other people’s countries, who are you to say we should not interfere in other people’s countries?

Challenge Your Ideas

The point of bringing your ideas out there is to challenge them. If you go around the argument and look at the person who is making the argument and you think that they do not deserve to make such argument, then you are making a judgement about the person, whether or not they are deserving to make an argument. Now, you are in that position where we can ask the same from you: who are you to deny this person making the argument?

Another thing is when people say, “Oh, Christianity is the same. It is as bad here. Look at the people. Look at how many police are killing black people or look how Christianity is also barbaric. Ancient ideology that could be as harmful.”

To that, I say, “Fuck you.” I am not talking about those things. I am talking about something else. An

example: Imagine if you have a fundraiser for cancer. You are trying to raise money to fund research for cancer. You want to fight cancer, and then people come in and start shouting. They say, “What about

AIDS? Why are you not talking about AIDS? AIDS is a disease too. AIDS is also killing people. You guys do not care about AIDS!” What would I do? I would probably kick these people out. AIDS is bad. Yes! However, we are talking about cancer because we are talking about the problems of cancer. That does not mean we are denying that AIDS is also a problem.

However, you are not helping by shifting the discussion to something that this fundraiser is not fighting for now. You are not helping, and fuck you for making everything about you. Because what you are doing is you are taking part in the Oppression Olympics. You think that if the conversation is not about the things that attacks your people or the things that have affected your life, then it is not worth talking about now. If you have been hurt by Christianity or by racism in the US, then when we come and say, “Islam is hurting people,” you are saying, “No, let us pay attention to this.” That makes you self-centered because you cannot stand it when other people are talking about being victims of something else other than what concerns you. You cannot stand people who are bringing awareness to something that you or the people around you are not victims of. If that is the case, then you are selfish and arrogant. However, some people might say this cancer and AIDS example does not make sense because Islam and Christianity have the same root.

Religion As A Whole

This is why we always want to say that we should not talk about Islam. Talk about religion as a whole. Okay, let me add to my example. Let us say we had a fundraiser about pancreatic cancer and then somebody came and said, “Skin cancer is a problem too. Why are you not talking about skin cancer?”

Is that close enough for you?

Sometimes, it makes sense to focus on a specific problem, even if it has similarities with other problems. Different problems manifest themselves in different ways. They harm people in different ways. They have different answers.

It makes sense to focus on a certain problem. Sometimes, it makes sense to look at it as a whole. However, it does not make sense when you always try to shift the attention to a different category when we are focusing on another one. It does not make sense because you are not helping. We are having a discussion about a certain topic and all you are doing is coming and saying, “pay attention to the problem that I care about.” That is what you are doing.

Better Than Most

The obsession for a certain issue might be for different reasons. It could be because you were hurt. It

might be because you know more about a particular topic. It might be simply because you care more about a certain issue. Who cares? At least, you are talking about a problem, which makes you better than most people.

For example, if somebody is going out there and rescuing dogs, I am not going to tell them, “What the fuck do you have against cats? Why are you not rescuing cats? Are other animals not good enough for you? Do they not deserve saving?”

This person maybe cares about dogs. Maybe, he is passionate about dogs. However, the fact that he is

rescuing dogs. He might be doing more than most people. Do you know what you say to somebody who is going out there and rescuing dogs? You say, “Thank you.” That is what you say to that person.

For example, let us say somebody says to me, “Why are you focused on Islam? Why not all religions?” I tell them, “Why are you so focused on other religions? Why not all dogma?” They might say, “Okay, all dogma.”

I am like, “Why are you focusing on all dogma? Why are you not focusing on all bad ideas? Does a bad idea have to be a dogma for you to focus on it?” Then they go, “Okay, all bad ideas.” I am like, “Bad ideas? What about other bad things? Does something have to be an idea for you to attack it? Diseases are not ideas. Why are you focusing on bad ideas?”

“Alright, so let us be more general, bad things are bad. Good things are good. Is that general enough for you? Is that good? How helpful is that? How helpful of a claim that is… bad things are bad?” You cannot get more general than that.

General Activism

Some people prefer to look at it more generally. Others might want to look at it more focused in a more specific situation. For example, there is a certain village in the Philippines, where the people need help now. This person wants to specifically focus on this group of people. People who do not have access to water. It is focused. Nobody will go to this person and be like, “Why are you focusing on that specific village?” That is incredibly focused, but I am sure most people will say, “Congratulations, that is good. Thank you for helping these people.”

But when it comes to Islam, many people, atheists especially, say, “Why are you focusing on Islam?” I do not think it is because their problem is that you are being too focused. I think they feel a certain amount of bigotry if you are focused on Islam because they do not say that about any other form of activism if it is focused on anything.

Have you ever heard anybody say that about any other form of activism? It looks ridiculous. Let us say somebody is focusing on the environment in Iran. Nobody comes to him and says, “Why do you not care about the environment in Iraq?”

Pushed Back for Bigotry

Every form of activism gets this bigotry pushback. However, this specific claim that you are being too focused is either regarding Islam or nationalism. For example, if Americans are focusing on other countries, they might get accused on why are you not focusing on problems at home.

I know a lot of people who are nationalistic and anti-globalist do not like this. However, I do not understand it. Why do we have to care about a certain group of people because they happened to be born on this side of the border instead of on the other side of the border? Is that good criteria for us to start caring about somebody? Why is that? What makes this so special? With this line in the sand, all of the sudden the person that is born on this side of it matters more?

Western Values

Another thing, I want to address Western values. The name: “Western values.” The reason why it is called Western values is because it first happened in Western countries. The fact that these values were adopted more in Western countries is a historical accident. Because they are named, “Western values,” now, that does not mean that the West should own these values. The West does not own women’s rights. The West does not own human rights. The West does not have a monopoly over not discriminating against gay people. The West does not have a monopoly on secularism. The West does not have ownership over freedom of speech.

The fact people are accusing us of bigotry because we are suggesting that these values should be global and introduced globally, you are being the bigots. You are claiming ownership over some values because you happened to historically come across it -- before the rest of the world. You are the people unwilling to share. You think that this is good for you, but it is not good for other people. Why is it not good for other people? What makes them so different from us that it works for you but not for them?

Western Superiority

You are the people claiming superiority. What is it about values that make somebody claim ownership over them? Why can we not introduce these values? Why can we not promote these values? It has been introduced, but we could promote it even more. Why can we not promote them? Could somebody use it to attack these countries? Reality check: somebody is using other values to oppress women.

If we go back to arguments people use when you are talking about Muslims and Islamic ideology, you are not looking at the main threat in the world. You are not looking at the main powers at play, at the destruction and the harm that they cause.

You have to see who is in control and not look at these minority Muslims in our Western countries. You have to make the difference where it matters the most now. Those are the ideas. The values that are being used to oppress people in foreign countries and in their countries by these major superpowers in the West.

I tell them that is a narrow way of looking at it because where I come from Islam is in power. You are underestimating Islam as a major superpower when you think about it that way. Islam is the fastest growing religion in the world. Islam is going to become the number one main ideology in the world soon.

Islam Colonization

Islam is dominating not lands but minds. Islam is used to rule over people and to oppress people. Islam has been used to colonize people. Do you think white people are the only people that can colonize?

Islam has been used for colonization way before the British discovered what that even means and that it is even an option. It is okay if it happens voluntarily. If people are adopting other people’s cultures or ideas or values voluntarily, that is not colonizing them. We are asking for these other values and ideas to be heard and considered rather than suppressed or silenced.

We asking for a seat at the table, at every table. I am not talking about a seat at a table talking about humanism and secularism in the United States, in the United Kingdom, in Canada, or in France. I am talking about a seat at a table in Iran, in Bangladesh, in Saudi Arabia, in Malaysia, in Indonesia, in Pakistan.

We demand a seat at a table. We are going to get it. if you think that that is us imposing our values on other people, fuck you. Because you are enjoying the benefits of these values, somebody at some point in your history was told that these values are not for your country. They did not stay silent. They sacrificed their lives. They sacrificed their safety. They sacrificed their comfort for you to enjoy that today. People are doing these things in Iran, in Saudi Arabia, and in Bangladesh. They are suffering for it.

Moral Cowardice

You are a moral coward for thinking that it is morally wrong for us to voice our feelings on the killing of secular bloggers in Bangladesh. Do you think it is not right for us to judge? Do you think you are not in a position to judge? To judge whether women having less inheritance rights in government, as a witness in court, on what they wear, where they go, what jobs they get, who they talk to, do you think that you are not in a position to make a moral judgment on that? That makes you a moral coward.

But what is moral or not? If you are making that judgement based on how different sets of actions

influence people’s well-being, then there is always a right answer and a wrong answer. There are many good answers and many bad answers. It does not take a genius to see that hanging gay people is not good for the well-being of the society. If you think that you are not in a position to make a moral judgment for other countries, I want you to tell me what you would say to the person that is about to be hanged because they are gay.

Go ahead and tell that to that person right before they are being hanged, say, “This is not

that bad. In my country it is bad, but here, this is your culture, so shame on you for being gay. If

you were in the United Kingdom, I would be marching for gay pride and being gay and proud, but here it is a different country. So, fuck you, fuck your gay ass, you deserve being hanged here.”

For The People in Islamic Countries

All the people who are in jail in Iran or Saudi Arabia; all the bloggers who died trying to spread secularism and humanism; all the people in Malaysia who after the government came out and said that they need to hunt down atheists; on behalf of those people, all the people that were burned or tortured for accusations of desecrating the Quran in Pakistan; on behalf of all those people, I want to say, “Fuck you to whoever says that it is their culture and who are we to judge and ask, ‘What’s right for them?’” On behalf of every woman that suffered from Islam; on behalf of every homosexual person that suffered in Islam; and on behalf of anybody that dares speak against Islam and paid the consequences for it, I want to say, “Fuck you” to whoever says, “Who are we to judge?”

Enlightenment for All

The Western countries went through the Enlightenment. Now we want this for other countries as well. We want the same enlightenment values. We want to fight for those values. If you are arrogant enough to want to deny the rest of us the same process, if you are not going to help, then stay out of our way. It is interesting a lot of people come and tell me, “Armin, why are you saying these things? That is our country. It has nothing to do with our country. That is Iran.” I almost, almost want to say, “Mother fuckers, I am from Iran.” However, I do not think that is even relevant because I think you should not need to be from there for you to care about them.

Situation in Yemen

Who do I care more about right now than even the people in Iran? I care more about the people in Yemen. If I could speak Arabic, I would have been tweeting more about the situation that is happening in Yemen because they are suffering more than the people in Iran. The fact that you think we have to be from there to care about them makes no sense to me. However, if you think that, and if you do not want to be part of the solution, and if you do not want to lend a voice to people that need you to lend them a voice, the people that are voiceless. The people that cannot speak for themselves.

If you are not going to use your platform to help them, then stay out of our way because we are going to keep doing that. We are going to keep doing that. It does not matter how many times you call us a bigot. We are going to keep fighting for those people.

If you think they need to do it themselves, then fuck you again because it would be much faster and much easier if we could help them out. Because we enjoy the freedom of speech here. We enjoy some security. We could bring more attention to their problems, to their suffering. We could help. We could help. They need our help. They are asking for our help. For you to deny that to them because you think they do not deserve it, it is selfish. It is selfish to judge your life by a different standard than what you are judging their lives by.

So, who are we to judge how people in Islamic countries live? To that I say, “That is the wrong question. The right question is, “Who do you have to be to remain silent?” The answer to that is, “You have to be a monster.” You have to be a monster to have seen such crimes being done against your fellow human beings and judge it by a different standard than what you would have done if it was happening in your own backyard.

About Atheist Republic

About Atheist RepublicFollow Atheist Republic on Twitter @AtheistRepublic

Published on July 08, 2018 01:00

A Morning Thought (68)

Published on July 08, 2018 00:30

July 7, 2018

Provos: “We Killed Jo Jo”

Tarlach MacDhónaill writes on the Andersonstown Town News admission of IIRA culpability in the 2000 murder of Joseph O'Connor.

This week’s Andersonstown News has finally accepted and printed what Belfast Republicans have known for almost two decades, that the Provisional I.R.A. murdered Volunteer Joseph O’Connor.

This week’s Andersonstown News has finally accepted and printed what Belfast Republicans have known for almost two decades, that the Provisional I.R.A. murdered Volunteer Joseph O’Connor.

It is not altogether surprising that such a ground-breaking shift from Provisional policy has passed-off largely unnoticed. The O’Connor family are in mourning following the tragic, sudden death of Jo Jo’s second youngest son Eamon (18) only weeks ago. Eamon’s death was preceded by that of his Grandmother Margaret’s just last year.

It is then understandable that the wider O’Connor family and their friends are presently consumed by grief. As Jo Jo was a member of the Real I.R.A which doesn’t exist anymore; it is unlikely that any statement from the group in relation to Jo Jo’s death will ever be carried in the media again.

The British-backed murder of I.R.A volunteer Joseph O’Connor arrived at an extremely delicate time for the Provisionals, during the initial stages of a sham-peace. The murder was planned and carried out with an immediate dual-aim, to execute an anti-agreement Republican while designating blame to other Anti-agreement Republicans in the process. From the very moment they shot him multiple times in the head and face, the death-squad busied themselves with the task of concealing their movement’s involvement in his murder.

Unfortunately for Sinn Féin, Ballymurphy is a small place. A seemingly arrogance-based brazenness allowed people to identify the death-squad who shot ‘Jo Jo’. This was followed by a number of mistakes being made during their escape. Logistical blunders aside, locals talk, and literally within minutes of Joseph O’Connor’s murder, his neighbours, his family, his friends and his comrades knew who was responsible, the Provisional I.R.A.

Immediately after the murder, local Sinn Féin spokespersons attempted to deflect blame onto other Republicans, they were assisted in their attempts by the RUC who raided the offices of Republican Sinn Féin, publicly citing Joe’s murder as their motive.

Within days the party’s accepted local mouthpiece “The Andersonstown news” also helped to raise the notion of an internal Republican feud by using ambiguous language to report on what the community knew to be facts. Even a year later the “Andersonstown news” continued to ply the idea of an internal Republican dispute as being responsible for the murder of Joseph O’Connor. Upon being challenged by members of Belfast 32CSM the paper’s editorial board smugly stated that their editorial line was ‘No I.R.A. involvement in the murder of Joseph O’Connor’, and that his death was the result of a ‘dissident feud’.

Joseph’s family friends and comrades were not alone in voicing their disgust at what the Provisional movement had done. Many well-known Republicans, including former life-sentence prisoner and blanket-man Anthony McIntyre and Maidstone escapee Tommy Gorman, added their voices to a steady stream of condemnation which naturally emanated from within the Republican base.

All of those who told the basic truth, for the simple sake of basic truth, faced immediate vilification for doing so, homes were picketed, vile abuse was spat at the direction of honest commentators, and one of the weapons used to attack them was the indisputable Sinn Féin alligned “Andersonstown news.”

A decade ago an opinion piece written by ‘Squinter’ criticising Gerry Adams appeared in the Andersonstown News. This story made international headlines because the Andersonstown News was then, as it is now, considered to be an organ of the Provisional movement and such internal criticism of Sinn Féin was unprecedented. When Gerry Adams was accused of forcing the paper’s editorial board to issue a grovelling, front-page apology to him, Sinn Féin’s critics went into overdrive. It is in this story that you will find evidence of the AndersontownNews’ links to and representation of Sinn Féin.

The magnitude therefore of the paper’s admission of I.R.A responsibility for Joe O’Connor’s murder poses a particular significance at this time.

Margaret O’Connor did not want revenge for her son’s death, all she asked was an admission of responsibility, perhaps an apology from those behind it. As a grieving mother, she lobbied Sinn Féin through Relatives for Justice and promised that as a republican, she would not pursue prosecutions, she kept that promise till her dying day.

Margaret O’Connor was denied this grace, she was offered nothing in return and sadly died last year in the very same turmoil that had been imposed upon her by a Provisional death-squad on Friday 13th of October 2000 outside her own home.

Perhaps the Andersons town News did not intend to accept that Jo Jo’s death was at the hands of the I.R.A. It has done so however and this simply cannot be ignored. The paper has gone out of its way over the years in publicizing its position that there is only one I.R.A, and that they are the Provisionals. Maybe it is an editorial oversight and maybe it is in preparation for something to come, maybe it is even a huge-leap forward in the pursuit of truth for victims of conflict.

Whatever the reasons questions now exist which demand answers. Why was Margaret O’Connor sent to her grave without an admission by Sinn Féin that the Provisional I.R.A had murdered her son?

Why has a media outlet, so closely and openly associated with Sinn Féin MLA Máirtín Ó Muilleoir challenged the leadership of Sinn Féin in this fashion?

Will Sinn Féin now tell the Republican people of Belfast the truth and apologise for the lies they told them in 2000 and ever since?

Will all of those who received Provisional death threats for telling the truth about Joseph O’Connor’s murder now be pardoned by the Army Council?

Or, Will Squinter return next Wednesday and apologise for making the biggest blunder since ‘they haven’t gone away you know’?

This week’s Andersonstown News has finally accepted and printed what Belfast Republicans have known for almost two decades, that the Provisional I.R.A. murdered Volunteer Joseph O’Connor.

This week’s Andersonstown News has finally accepted and printed what Belfast Republicans have known for almost two decades, that the Provisional I.R.A. murdered Volunteer Joseph O’Connor. It is not altogether surprising that such a ground-breaking shift from Provisional policy has passed-off largely unnoticed. The O’Connor family are in mourning following the tragic, sudden death of Jo Jo’s second youngest son Eamon (18) only weeks ago. Eamon’s death was preceded by that of his Grandmother Margaret’s just last year.

It is then understandable that the wider O’Connor family and their friends are presently consumed by grief. As Jo Jo was a member of the Real I.R.A which doesn’t exist anymore; it is unlikely that any statement from the group in relation to Jo Jo’s death will ever be carried in the media again.

The British-backed murder of I.R.A volunteer Joseph O’Connor arrived at an extremely delicate time for the Provisionals, during the initial stages of a sham-peace. The murder was planned and carried out with an immediate dual-aim, to execute an anti-agreement Republican while designating blame to other Anti-agreement Republicans in the process. From the very moment they shot him multiple times in the head and face, the death-squad busied themselves with the task of concealing their movement’s involvement in his murder.

Unfortunately for Sinn Féin, Ballymurphy is a small place. A seemingly arrogance-based brazenness allowed people to identify the death-squad who shot ‘Jo Jo’. This was followed by a number of mistakes being made during their escape. Logistical blunders aside, locals talk, and literally within minutes of Joseph O’Connor’s murder, his neighbours, his family, his friends and his comrades knew who was responsible, the Provisional I.R.A.

Immediately after the murder, local Sinn Féin spokespersons attempted to deflect blame onto other Republicans, they were assisted in their attempts by the RUC who raided the offices of Republican Sinn Féin, publicly citing Joe’s murder as their motive.

Within days the party’s accepted local mouthpiece “The Andersonstown news” also helped to raise the notion of an internal Republican feud by using ambiguous language to report on what the community knew to be facts. Even a year later the “Andersonstown news” continued to ply the idea of an internal Republican dispute as being responsible for the murder of Joseph O’Connor. Upon being challenged by members of Belfast 32CSM the paper’s editorial board smugly stated that their editorial line was ‘No I.R.A. involvement in the murder of Joseph O’Connor’, and that his death was the result of a ‘dissident feud’.

Joseph’s family friends and comrades were not alone in voicing their disgust at what the Provisional movement had done. Many well-known Republicans, including former life-sentence prisoner and blanket-man Anthony McIntyre and Maidstone escapee Tommy Gorman, added their voices to a steady stream of condemnation which naturally emanated from within the Republican base.

All of those who told the basic truth, for the simple sake of basic truth, faced immediate vilification for doing so, homes were picketed, vile abuse was spat at the direction of honest commentators, and one of the weapons used to attack them was the indisputable Sinn Féin alligned “Andersonstown news.”

A decade ago an opinion piece written by ‘Squinter’ criticising Gerry Adams appeared in the Andersonstown News. This story made international headlines because the Andersonstown News was then, as it is now, considered to be an organ of the Provisional movement and such internal criticism of Sinn Féin was unprecedented. When Gerry Adams was accused of forcing the paper’s editorial board to issue a grovelling, front-page apology to him, Sinn Féin’s critics went into overdrive. It is in this story that you will find evidence of the AndersontownNews’ links to and representation of Sinn Féin.

The magnitude therefore of the paper’s admission of I.R.A responsibility for Joe O’Connor’s murder poses a particular significance at this time.

Margaret O’Connor did not want revenge for her son’s death, all she asked was an admission of responsibility, perhaps an apology from those behind it. As a grieving mother, she lobbied Sinn Féin through Relatives for Justice and promised that as a republican, she would not pursue prosecutions, she kept that promise till her dying day.

Margaret O’Connor was denied this grace, she was offered nothing in return and sadly died last year in the very same turmoil that had been imposed upon her by a Provisional death-squad on Friday 13th of October 2000 outside her own home.

Perhaps the Andersons town News did not intend to accept that Jo Jo’s death was at the hands of the I.R.A. It has done so however and this simply cannot be ignored. The paper has gone out of its way over the years in publicizing its position that there is only one I.R.A, and that they are the Provisionals. Maybe it is an editorial oversight and maybe it is in preparation for something to come, maybe it is even a huge-leap forward in the pursuit of truth for victims of conflict.

Whatever the reasons questions now exist which demand answers. Why was Margaret O’Connor sent to her grave without an admission by Sinn Féin that the Provisional I.R.A had murdered her son?

Why has a media outlet, so closely and openly associated with Sinn Féin MLA Máirtín Ó Muilleoir challenged the leadership of Sinn Féin in this fashion?

Will Sinn Féin now tell the Republican people of Belfast the truth and apologise for the lies they told them in 2000 and ever since?

Will all of those who received Provisional death threats for telling the truth about Joseph O’Connor’s murder now be pardoned by the Army Council?

Or, Will Squinter return next Wednesday and apologise for making the biggest blunder since ‘they haven’t gone away you know’?

Published on July 07, 2018 01:00

A Morning Thought (67)

Published on July 07, 2018 00:30

July 6, 2018

Contract In Blood

Christopher Owens reviews a book by musician and writer, Ian Glasper.

The best books about music are the ones that are so absorbing, it doesn't matter if you like the music or not. And the best authors are the ones who focus just as much on the unloved ones as much as the classic bands.

A scribe for metal magazine Terrorizer since forever, Ian Glasper is what we would call a lifer. Being immersed in punk since 1980, he has played in numerous bands and feels compelled to catalogue the various scenes for posterity. For this, we are truly grateful.

His previous books have focused on the UK punk scene in all it's guises (UK82, anarcho/crust, hardcore, metalcore, pop punk, melodic hardcore) so it makes sense for him to turn his focus to the UK thrash scene from its beginnings in the early 80's, to the present day, where younger bands pick up the baton and spread the music far and wide.

What's always been infectious about Glasper's tomes is that he gives just as much space to the lesser known bands as he does to the big hitters (i.e. the ones you've come to read about) and their tales are just as compelling. Quite often, it can just be about the environment that they come from. Reading about the likes of Richard III (from Co. Cavan) act as a reminder just what a conservative, backward looking hellhole this country was in the early 90's, culturally speaking.

Or Lord Crucifier, originally from Rome but who ended up settling in Halifax, Yorkshire because Rome had nothing to offer them.

Of equal interest are the tales of tension between the thrashers and the hardcore punks, always fascinating to read. Although, to most, thrash metal and hardcore punk sound similar, both cultures come with their own set of rules and influences. And sometimes, crossing over isn't good for a band's health (one of the first "crossover" bands, English Dogs, were universally sneered at by punks when they turned metal).

And it's rather telling that, for me, the most creative records of that era were put out by bands with backgrounds in hardcore punk (English Dogs, Warfare, Hellbastard, Sacrilege).

And this is a crucial point because it's important to remember that, at the time, Britain had little credibility in the thrash scene, which was dominated by the Americans (Metallica, Slayer, Megadeth) and the Germans (Kreator, Sodom, Destruction) with Swiss pioneers Celtic Frost dropping jaws around the world for their twisted, evil and avant-garde approach to the genre.

Although Britain helped create the genre with Venom (who are now mainly synonymous with black metal), the biggest bands it could boast of were Onslaught, Slammer and Sabbat, with bands like Acid Reign and Xentrix retaining a sizeable national following but never translated into anything worldwide.

Throughout, Glasper queries why the UK never garnered sufficient credibility. Although the answers vary, the cold truth is that if you put any record by those bands up against the likes of Reign in Blood, Morbid Tales or Pleasure to Kill, you will see that they are worlds apart. And that's just in terms of extremity. Put the same records up against bona fide metal classics like Master of Puppets, Peace Sells...But Who's Buying and Among the Living, albums that are hailed by mainstream critics and music fans as the epitome of heavy metal and the British ones just don't stand up.

To be fair, Britain were pushing the boundaries when it came to hardcore punk, giving us Extreme Noise Terror, Napalm Death, Sore Throat and giving birth to the genre that we now call grindcore. And gothic metal (coming out of bands like Paradise Lost and My Dying Bride) was also on the ascendency in this period.

So, by contrast, the UK thrash acts couldn't help but come across as also-rans. But the ones with some punk in their system could end up creating something that stands above most of their peers.

However, leaving aside tribal allegiances,, Glasper has to be saluted for his efforts. He takes a genre that has long been written off for the reasons listed above and shows it sufficient respect for readers unfamiliar with the bands to take an interest in the recordings. It's the human touch, the dreamers who felt they were just as good as the big boys. They're the ones who keep going regardless of trends, and the ones who talk about their time with pride and affection.

Contract in Blood is a celebration of an area of underground music and a great jumping off point for readers who now want to check out Slammer or Evil Priest.

Ian Glasper Contract in Blood: A History of UK Thrash Metal 2018 Cherry Red Publishing ISBN-13: 978-1909454675

➽ Christopher Owens reviews for Metal Ireland and finds time to study the history and inherent contradictions of Ireland.Follow Christopher Owens on Twitter @MrOwens212

The best books about music are the ones that are so absorbing, it doesn't matter if you like the music or not. And the best authors are the ones who focus just as much on the unloved ones as much as the classic bands.

A scribe for metal magazine Terrorizer since forever, Ian Glasper is what we would call a lifer. Being immersed in punk since 1980, he has played in numerous bands and feels compelled to catalogue the various scenes for posterity. For this, we are truly grateful.

His previous books have focused on the UK punk scene in all it's guises (UK82, anarcho/crust, hardcore, metalcore, pop punk, melodic hardcore) so it makes sense for him to turn his focus to the UK thrash scene from its beginnings in the early 80's, to the present day, where younger bands pick up the baton and spread the music far and wide.

What's always been infectious about Glasper's tomes is that he gives just as much space to the lesser known bands as he does to the big hitters (i.e. the ones you've come to read about) and their tales are just as compelling. Quite often, it can just be about the environment that they come from. Reading about the likes of Richard III (from Co. Cavan) act as a reminder just what a conservative, backward looking hellhole this country was in the early 90's, culturally speaking.

Or Lord Crucifier, originally from Rome but who ended up settling in Halifax, Yorkshire because Rome had nothing to offer them.

Of equal interest are the tales of tension between the thrashers and the hardcore punks, always fascinating to read. Although, to most, thrash metal and hardcore punk sound similar, both cultures come with their own set of rules and influences. And sometimes, crossing over isn't good for a band's health (one of the first "crossover" bands, English Dogs, were universally sneered at by punks when they turned metal).

And it's rather telling that, for me, the most creative records of that era were put out by bands with backgrounds in hardcore punk (English Dogs, Warfare, Hellbastard, Sacrilege).

And this is a crucial point because it's important to remember that, at the time, Britain had little credibility in the thrash scene, which was dominated by the Americans (Metallica, Slayer, Megadeth) and the Germans (Kreator, Sodom, Destruction) with Swiss pioneers Celtic Frost dropping jaws around the world for their twisted, evil and avant-garde approach to the genre.

Although Britain helped create the genre with Venom (who are now mainly synonymous with black metal), the biggest bands it could boast of were Onslaught, Slammer and Sabbat, with bands like Acid Reign and Xentrix retaining a sizeable national following but never translated into anything worldwide.

Throughout, Glasper queries why the UK never garnered sufficient credibility. Although the answers vary, the cold truth is that if you put any record by those bands up against the likes of Reign in Blood, Morbid Tales or Pleasure to Kill, you will see that they are worlds apart. And that's just in terms of extremity. Put the same records up against bona fide metal classics like Master of Puppets, Peace Sells...But Who's Buying and Among the Living, albums that are hailed by mainstream critics and music fans as the epitome of heavy metal and the British ones just don't stand up.

To be fair, Britain were pushing the boundaries when it came to hardcore punk, giving us Extreme Noise Terror, Napalm Death, Sore Throat and giving birth to the genre that we now call grindcore. And gothic metal (coming out of bands like Paradise Lost and My Dying Bride) was also on the ascendency in this period.

So, by contrast, the UK thrash acts couldn't help but come across as also-rans. But the ones with some punk in their system could end up creating something that stands above most of their peers.

However, leaving aside tribal allegiances,, Glasper has to be saluted for his efforts. He takes a genre that has long been written off for the reasons listed above and shows it sufficient respect for readers unfamiliar with the bands to take an interest in the recordings. It's the human touch, the dreamers who felt they were just as good as the big boys. They're the ones who keep going regardless of trends, and the ones who talk about their time with pride and affection.

Contract in Blood is a celebration of an area of underground music and a great jumping off point for readers who now want to check out Slammer or Evil Priest.

Ian Glasper Contract in Blood: A History of UK Thrash Metal 2018 Cherry Red Publishing ISBN-13: 978-1909454675

➽ Christopher Owens reviews for Metal Ireland and finds time to study the history and inherent contradictions of Ireland.Follow Christopher Owens on Twitter @MrOwens212

Published on July 06, 2018 01:00

A Morning Thought (66)

Published on July 06, 2018 00:30

July 5, 2018

Desperately Seeking Socialism

A response by Gabriel Levy to Dissidents Among Dissidents, by Ilya Budraitskis – and Budraitskis’s response to that response. Dissidents Among Dissidents (Dissidenty Sredi Dissidentov) was published in Russian in 2017 by Free Marxist Publishers [Svobodnoe Marksistskoe Izdatelstvo].)

Русская версия здесь / Russian version here

The existence of a “new cold war” was already being treated in public discourse as an “obvious and indisputable fact”, Budraitskis argues – but “the production of rhetoric has run way ahead of the reality” (pp. 112-3).

To question the assumptions behind the rhetoric further, in the essay, “Intellectuals and the Cold War” (in English on line here), Budraitskis considers the character of the original cold war, i.e. between the Soviet bloc and the western powers between the end of the second world war and 1991. The cold war was a set of “principles of the world order”, construed by ruling elites and then confirmed in intellectual discourse and in the everyday activity of masses of people, he writes (p. 112).

The reality of continuous psychological mobilisation, and the nerve-straining expectation of global military conflict, as apprehended by society as a whole, became a means of existence, reproduced over the course of two generations, in which loyalty to beliefs was combined with fear and a feeling of helplessness before fate.

This proposition, that the cold war was essentially a means of social control, in which masses of people were systematically deprived of agency, certainly works for me. I wondered whether Budraitskis knows of the attempts, made during the cold war on the “western” side of the divide, to analyse this central aspect of it – for example of the work of Hillel Ticktin and others in the early issues of the socialist journal Critique (from 1973). (Ticktin wrote on the political economy of the Soviet Union, interpreting it in the context of world capitalism. The journal web site is here.)

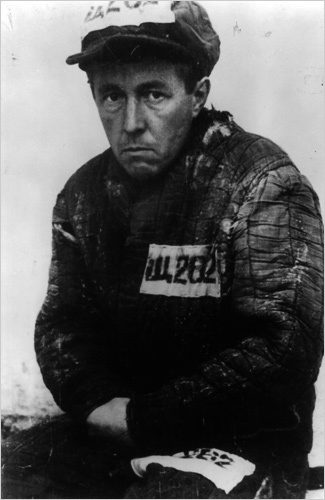

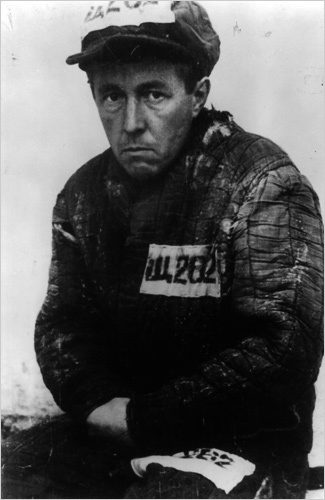

Prague, 1968: students take on Soviet tanks

Prague, 1968: students take on Soviet tanks

Today, the cold war’s binary ideological constraints live on, Budraitskis argues. “The trauma of choice between hostile camps has still today not been overcome” (p. 123). As an example, he quotes the reactions to Russia’s participation in the war in eastern Ukraine by, on one hand, Aleksandr Dugin, the extreme right-wing Russian “Eurasianist”, and, on the other, the American historian Timothy Snyder. (See here (Russian only) and here.)

For Dugin, the military conflict in eastern Ukraine amounted to “the return of Russia to history”. For Snyder, it was confirmation that Ukraine had finally to recognise that it was part of Europe. Dugin’s anti-Europe and Snyder’s Europe leave no room for a third way, Budraitskis asserts gloomily (p. 120).

On this at least, I feel more optimistic. It is undeniable that elite-controlled public forums have increasingly been dominated by this two-sided, one-dimensional discourse. On the “left”, this false dichotomy has been reflected in “geopolitical” stances that base themselves on the relative qualities of imperialist blocs, and deny agency to, or sideline, society generally and social movements particularly. But those social movements exist, and there are voices in the intelligentsia that reflect them.

Escaping the binary

From the late 1940s, both in the west and in the Soviet Union, the intelligentsia began to be transformed “from a group that was capable simply of implementing an ideological order, to one that was prepared independently to formulate it, make it more precise and reproduce it”,

Budraitskis writes (pp. 113-114). In the Soviet Union, the intelligentsia was constrained by the state’s imperialistic and chauvinistic approach to politics. That defined not only 1960s debates such as those about the scientific-technical revolution and “socialism with a human face”, but even 1970s Soviet dissidents’ discussions of the relationship between “national” and “universal-humanist” values.

It was “self-evident”, and “required no special confirmation from above”, that a “third way” for intellectuals, that escaped the “binary structure of the East-West conflict [of states]”, was “impossible”, Budraitskis argues. The proof, for him, was that as official “Marxism-Leninism” became completely discredited in the two decades prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, that collapse “could not then be understood otherwise than as the victory of one of the military-political blocs [i.e. the western one]” (p. 115).

I read this passage hoping for more caveats and qualifications. I accept that the western liberal narrative about the “collapse of communism” in the 1990s became ubiquitous and overwhelming in those spaces – journalism, academia, etc – that in the west are called “public opinion”. But surely there were dissenting and critical strands in the intelligentsia – particularly if understood in the wider way that it used to be in Soviet times – both in the west and in the former Soviet states.

In Russia, those public spaces were taking shape, uncensored, in a new way. Immediately before and after the collapse of the USSR, Russian journalism was in its heyday, lashing out at corruption and the horror of the first war in Chechnya, before corporate control and Putin-era censorship tightened the screws. In film, the reckoning with Stalinism began, running from Elem Klimov’s Come and See (1985) to Nikita Mikhalkov’s Burnt By The Sun (1994). In literature, Viktor Pelevin’s Generation “P” (1999), magnificently, turned Yeltsin’s regime into an absurd phantasmagoria.

These are just the (perhaps rose-tinted?) memories of a western leftist who started travelling to Russia at that time. But I want to know how this rich, chaotic ferment fits in to Budraitskis’s argument.

The dissidents’ history

The centre-piece of Budraitskis’s book is a longer essay, “Dissidents Among Dissidents”, that traces the history of socialist trends in the Soviet dissident milieu between the mid-1950s and the Gorbachev reforms of the mid-1980s. It is a fascinating and valuable piece of work.

Budraitskis describes (p. 34) how a “wave of social discontent” in the Soviet Union in the late 1950s, echoing the workers’ revolts in Hungary, Poland and the German Democratic Republic – from large-scale riots in Chechnya (1958) and Kazakhstan (1959) to protests and attacks on Communist party offices in Murom and Aleksandrov (1961) and culminating in the Novercherkassk rebellion (1962) – formed the background not only to the twentieth Communist Party congress (1956) and Nikita Khrushchev’s post-Stalinist “thaw”, but also to the emergence of the first big wave of socialist dissident groups. They were mostly made up of students and young workers in larger cities, they always met in secret, were usually isolated from each other, and their activity was almost always cut short by arrests.

There had been precursors, in the last years of Stalin’s rule, such as the “Communist Party of Youth” (formed in Voronezh in 1948) and the “Union of Struggle for the Cause of Revolution” (formed in Moscow in 1951). These student groups were soon crushed by arrests and long prison sentences. But the “thaw” of the late 1950s and early 1960s brought such public forums as gatherings in Moscow for poetry reading and discussion at the statue of Vladimir Mayakovsky, and a corresponding widening of political activity.

The meaning of socialism, then and now