Deena Metzger's Blog, page 5

January 5, 2019

Extinction Illness: Grave Affliction and Possibility Featured Essay on Tikkun by Deena Metzger

“Everyone says climate is the most important issue of all, and yet they just carry on as before. I don’t understand that. Because if the emissions have to stop, then we must stop the emissions. To me that is black or white. There are no gray areas when it comes to survival. Either we go on as a civilization or we don’t. We have to change.”

– Greta Thunberg, 15-year-old climate activist, self-identified as autistic, speaking at the UN Climate Summit in Poland, December, 2018.

The insight came swiftly, undeniable and overwhelming, like the fire storm that devoured Paradise. Instant and devastating. The impact and understanding immediate.

I had been reeling from the news of the last years regarding climate disruption, wars, famine, hate crimes, the desperation of migrants and refugees, and the incomprehensible chaos and brutishness of our current president – as have we all – and also from a series of events which I had met individually and, without realizing it, had compartmentalized in order to respond from an open an unimpeded heart.

But coming home after many days away to phone messages from two different women who could not speak coherently because they had broken into sobs, I was alerted to the grief that they were carrying for all of us which could not be contained in a personal story. I knew then these are not merely difficult times. And even this might not have been sufficient to alert me to the extremity of the critical shift in our weather, external and internal, had not another message been left from a friend whose daughter had just been killed by the Thousand Oaks shooter and another from a relative on her way to the Pittsburgh synagogue where there had just been a massacre.

On Friday November 13, 2015, I had stayed up all night emailing with a friend in Paris as she hid in her apartment after the bombings which had just occurred in her neighborhood. And in the last year, I had been advising several friends and colleagues who are offering trauma counseling and community support to the Parkland survivors and their families as well as to students and faculty in Pine Ridge who were trying to meet a rash of suicides and attempted suicides in teenagers and younger children. There were also three deaths of young people close to me in the last month. A startling number of friends and acquaintances, formerly competent and active people, have been unable to function for long periods of time due to disabling depression, anxiety, and despair; I do not know if they will recover. Two members of our small, well-educated and trained community are homeless, unable to find work or permanent housing with friends or relatives. An alarming percentage of friends’ children are suffering from addiction, schizophrenia, depression, and are in danger of committing suicide. Two women will meet with me this week to explore writing about living with wary children (plural) suffering mental illness while another friend called to ask for prayers for yet another young man incarcerated in a mental hospital. One of our Daré (community healing circles) members reports monthly on the condition of two sons in and out of mental hospitals over the last ten years. There has been more mental illness and addiction in my extended family than I had ever conceived possible when I was young and more children in my kinship network suffering from conditions that range between high functioning Asperger’s syndrome and extreme autism requiring full time care.

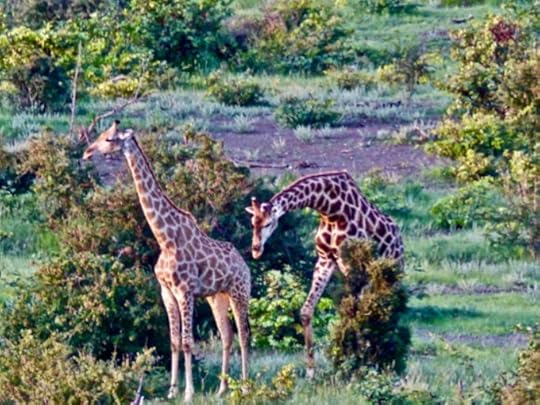

At night, I dream the anguished cries of polar bears, grizzlies, fur seals, whales, wolves, elephants, giraffes, lions, whose habitats are overrun, toxic and gravely dangerous, who cannot live a moment without fear of the next action by the ravenous two-leggeds who hunt or gawk, who pollute, destroy, and dominate. Though I had to evacuate for a week because of the firestorm threat to Topanga, my discomfort did not compare to the death in the Woolsey fire of two of our very, very few mountain lions when 85% of the wild mountain park that was their territory burned. Meanwhile, the rangers cautioned us not to put out water or food because “the animals are resourceful” even though there is no water to be found in this drought which caused the fires. Simultaneously, the Camp Fire changed everything as people were vaporized or cremated in a fire that was hotter than any natural fire we have known. A filmmaker friend who traveled to Chico and Paradise found people gathering – Climate Uprising – to face the climate crisis even while sifting through the ashes for signs of their loved ones and trying to imagine how to survive and rebuild. The probability that there was and may continue to be a release of radiation from the toxic and radioactive super site at the old Rocketdyne lab in Simi Valley is democratically experienced by all beings which means the remaining mountain lions and all the flora and fauna and human beings, myself, my children, my friends included within a hundred miles.

What was my realization? Here it is:

We are all going extinct.

The animals know this and now all humans know this as well. Sensing the imminent death of all species, the cellular understanding of our common fate is making us ill. Our nervous and physical systems cannot bear this terrible knowledge. The growing understanding of the reality of the human caused 6th Extinction is resulting in Extinction Illness.

Contemplating the extent and pervasiveness of despair and violence across the globe, the increasing aberrance of human and non-human behavior, I see that all humans and non-humans know this, all human people and all beings, animals, trees, birds, insects, fish, know this. And all of us are being driven to some form of madness, pain, or dysfunction. For the animals, Bear, Wolf, Elephant, Whale this results in unavoidable and unmediated terror. We humans know, with or without awareness, that we are responsible. And so, we, entirely crazed, become a species that commits ecocide even as we die of it. The different signs and symptoms are ubiquitous and no one is escaping it.

We know we are going extinct. We know this consciously and/or unconsciously. Each person on the planet knows this. Extinction is upon us and no one is immune to it. All beings sense our/their imminent death. Not only their individual deaths, but far worse, the death of their species. An unbearable thought. And beyond that, the death of all species ….

My father, writer Arnold Posy, feared for the death of his people. He wrote in Yiddish and mourned its death and everything that would mean, the end of a culture which was held together for hundreds of years by language. I lived every day with his grief as the truth of the Holocaust descended upon him. He had escaped the Czarist army and made his way to England, because he knew how Jews fared when conscripted and also, he was not a man who could take up a gun. His brother came to the foot of his bed one night, his uniform torn and stained with mud, his head bandaged and bloody, his body broken and exuding the patina of death. “Look, Aria, what the Cossacks have done to me,” the ghost said and disappeared. Weeks later, a letter came to London detailing his death in the army. My father knew that had he not escaped, he would also have died by fragging but he could not bear the reality that his family of twelve children and numerous aunts, uncles, cousins, had perished in mass graves, save him, the youngest, and his sister the oldest, twenty years between them.

We lived with these deaths though my father’s personal sorrow was mostly silenced by the greater wail of the Holocaust. In 1945, at age 9, I learned of the atom bomb and sensed that I would also mourn other incomprehensible tragedies. When my father died in 1987 when I was fifty, I knew that I would be carrying not the death of a people but the death of all peoples, human and non-human alike, the death of the planet, of Earth, of the future, of all life.

It is possible that Extinction Illness is the root of all contemporary mental, physical, and spiritual diseases. Extinction Illness, the essential cellular knowledge and terror that one’s life, one’s people’s lives, all life is threatened, that lineage is disappearing, that we, all, may well become extinct within a very short period of time, that the future will be eradicated.

The fire of knowing sweeps down upon us like a tornado and there is no place to run. There is no escape. And worse, we do not get to live our ordinary lives until the moment of Extinction. Much suffering is inevitable before our demise in whichever way it will come to any one of us.

An inevitable prelude arises: Extinction illness – our bodies, minds, souls reeling with the terrible reality of what we have done, are doing. Extinction is our fault.

Whether or not we ‘believe’ the scientists who say climate change is Anthropocene Climate Disruption, meaning we are the cause, we know extinction and our role in it, consciously and unconsciously. Even those who don’t consciously know or accept the reality of the 6th Extinction or Climate Change or Disruption or recognize the consequences of the bleaching of the barrier reefs, the glaciers and poles melting, the acidification of the oceans, the extreme weather shifts, deadly floods, year-long and increasingly intense fire seasons, wind tornadoes and fire tornadoes, the insect apocalypse, the collapse of fisheries, deforestation, desertification and 17,000 species threatened at this time, they know. The unconscious knows. The soul knows. The connected life system knows even if the individual isn’t consciously aware. He/she/they were born into the network of all life and Life knows too. As Ubuntu teaches, “I am because you are,” which now we must rephrase: I will not be because you will not be. I will not be if you will not be.

Extinction illness. A world condition and a world affliction. Perhaps this systemic affliction is at the root of all our current global plagues, diseases, and illnesses.

As I write this to you, my heart beat is irregular and pounding. I know the reality of all of this in my body. We each know this differently. I know it through hartzveitig– the pain of extreme grief and despair, the anguish of the broken heart. There is no physical medical cause for my body’s agitation; there is only this physical manifestation of hartzveitig. It could be any symptom. It could be any of the conditions or situations mentioned in the beginning of this desperate exhortation to sanity and change. It could be a heart attack, intractable depression, inconsolable grief, addictions of every sort, splitting, compulsions, denial, extreme greed and territoriality, violent rages, derangement, uncontrollable aggression, murder, urges to suicide, even, paradoxically, paralleling the host of auto-immune responses, deliberate acts of ecocide. It could be any of these arbitrary or happenstance physical or mental manifestations of the same illness which we mistake for symptoms and treat uselessly, as we often treat symptoms without seeking the essential core.

As there is no pharmaceutical for Extinction, there is none for Extinction Illness. There is no anti-biotic, no anti-depressant or anti-psychotic, no sedative, no bone marrow transplant, no chemotherapy, rodenticide, no pesticide, no radiation therapy. To the contrary, this list makes it clear that these conventional medicinals are the poisons which accelerate the condition. There is no personal healing for these conditions and treating or focusing on the symptoms is counter-productive and exacerbates our common jeopardy.

Here we are. We are all suffering a life-threatening illness for which there is no discoverable cure. How shall we meet it?

For a period of time, we may be able to bear the symptoms or pretend that they are part of the natural order of disease to be treated conventionally. Over time, this blind recourse will be seen to be self-serving and futile. Like any being with a life-threatening illness, we suffer it and respond in a thousand different ways before we ultimately succumb.

However, in rare cases we can transform our fate through deep listening to what the body and soul need to reverse the death process and enter life. Healing our lives and preparing for good deaths is the same action. Can we heal ourselves, our planet? Can we desist from doing so much harm? There is no medicine, no medical procedure that will heal Extinction except ….

The only healing for Extinction, and so Extinction IIlness, as they are entirely intertwined, is stopping Extinction.

***

When one is suffering a life-threatening illness, one is called to look beyond the physical manifestation to see the root cause and determine what one can do to change one’s life and, hopefully, extend, even save it. As it happens, the particular symptoms we have, the particular affliction, often point the way to the healing action we are to take. This implies that each of us suffering distinctly gets to add exactly what is needed to the complex whole. Though this way of proceeding is not part of conventional western medicine, it is still a deep response among many people who search to find meaning and purpose in a healing path. Cure is instant but healing is a life-long practice.

Learning I had cancer at age forty, I understood I had to change my life in every way to create health. I had to leave a relatively secure teaching life for the unknown, risking my income, leaving friends, community, comfort and a four-bedroom house and pool in the suburbs to live in Topanga, a rural canyon in California in a two-room broken down cottage at the end of a dirt road to which I had to bring water and other basic amenities. My value system was undergoing an extreme reset. It was excruciatingly difficult to strip away socialization, conventional assumptions about the good life and everyone’s advice to remain safe, but I knew my life depended on the shift. Struggling and afraid, I turned inward to create a relationship with the natural world. Cancer striking at age forty brought a dark time, but the activity of healing brought light. Not everyone can leave our urban centers, but we can transform them so that we are all living less desperate and disconnected lives. We can find the necessary ways to restore and co-exist in different degrees with the wild everywhere. However, to really live once again with the natural world and the wild on their own terms means to strip away almost everything and begin again. And only when we do so will we be in the right mind to begin to contemplate what is next and how to proceed on behalf of a future for all beings, including ourselves.

In the mid-seventies, a man suffering cancer said to me, “Cancer is the answer.” He had changed his life drastically from a deadly regime to life-giving ways that entirely invigorated him and it seemed was also going to extend his life significantly.

And so, given that we are all suffering this life-threatening condition which manifests in the deterioration of the natural world and in concomitant individual, social, political, global catastrophes, and given that a multitude of climate scientists, specialists of Earth medicine, asserted on October 7, 2018, through the release of a UN climate assessment report that we have only twelve years to lower the carbon level or all life as we know it is done for – all life – then we have less than twelve years to reverse this diagnosis. How, then, shall we live to promote health? How will we change our lives drastically enough to save Life itself?

Well, we will have to love life, won’t we? We will have to love life, the natural world, value beauty and the wild nature above all else, won’t we?

And here’s the rub: in order to save our lives, we have to save everyone’s life, human and non-human, because Extinction Illness tells us that we cannot survive alone as the life force and life cycles depend absolutely on diversity and the abundance of all the life forms.

In modern days, when a plague or virus affects a large population or is highly contagious and uncontrollable, all health and medical resources are directed toward healing and containment. But in this instance, medical, psychological, and health personnel have not considered it their duty, let alone their primary responsibility to make the diagnosis and find the causes of Extinction and Extinction Illness in our lives and respond accordingly. It is urgent that we do so. The ultimate meanings of “Physician heal thyself,” coupled with, “First do no harm.”

So much more can and must be said and explored about this, but first we must take in the reality of the illness, its multiple forms and manifestations, the ways it masks ordinary diseases, and the truth that there are no easy cures or even opiates to dull the pain. First, we must recognize our condition and then admit we have caused this crisis, that we continue to create it. We are responsible. It is a consequence of our willful and/or oblivious initiation of an auto-immune disease, simultaneously homicide and ecocide.

Extinction Illness: an affliction and an alert. In 1977, cancer alerted me to Imperialism and its affects: a rogue cell invades a territory, reproduces itself without assuming any useful functions to sustain the whole, uses up all the available resources and pollutes the site until everything, itself included, dies. I had to know it in my body in order to understand its grave harm in the world. Extinction Illness alerts us to the dire effects of our predatory nature. Extinction Illness is an iconic auto-immune disease: the species attacks itself and all life is threatened.

But deep self-scrutiny of the illness and its causes can reveal, as is the case, again, with other life-threatening illnesses, which paths lead to healing and the restoration of vitality. There are old medicines and medicine ways that can be revived. Indigenous peoples whose ways and culture are not responsible for this tragedy, though they suffer it, know something of the values, approaches, lived ways that can mitigate what is otherwise our grim fate. Deep immersion in and attention to and unconditional love of the natural world are necessary pathways. There are other ways we can find but none will be effective unless we willingly, ruthlessly and essentially change our lives.

The only healing for Extinction Illness is changing our lives to stop Extinction.

The only healing for Extinction Illness is changing our lives to stop Extinction.

Read the essay at Tikkun.org

November 29, 2018

The Eulogy that Deena offered at the Memorial for Noel Sparks killed by the Thousand Oaks Shooter

From Noel’s FB page September 9, 2017:-

Sometimes you don’t know the value of something until it becomes a memory – Dr Suess

“I knew also, that for us, the older generation, Noel was hope. When we think of how, despite our efforts, we have failed the time, we think of young people like Noel as hope for the future.”

I knew Noel from approximately age 8 to 14. We met through poetry and music. I was reading my poetry with Jami Sieber, cellist and Wendy Anderson, her mother, and Noel were in attendance. They followed Jami’s music so closely I can only guess that Jami inspired Noel’s love of the cello. In that way, I think my writing inspired this gifted young woman as well. Our souls found each other, Jami, Wendy, Noel and I. When Noel was about twelve or thirteen, she attended a week-long writing retreat I offered for advanced writers, many already published. She held her own and helped out in the kitchen. All of it part of her home schooling, which Wendy pursued with the utmost seriousness and devotion. She home schooled Noel because she knew how remarkable Noel was and had a sacred responsibility to provide the fullest most relevant education possible.

When he confirmed that I would be speaking today, Pastor Curtis Johnson asked me to craft a message of hope. I took in his request deeply and have been contemplating the nature of hope, how it arises and guides us. I knew given these terrible circumstances and the grief and violence of these dark years like no other on the face of the earth since the beginning of time, that I had to offer real hope, not rhetoric or exhortation, but hope that would be palpable and sustaining for everyone, myself included.

I knew also, that for us, the older generation, Noel was hope. When we think of how, despite our efforts, we have failed the time, we think of young people like Noel as hope for the future.

When we read the current dire IPCC report, the International Panel on Climate Change, and see how grievously we have attacked the earth, or when we take in the tragedy of the fires still burning here and in the North, that are of our doing, we think of Noel who loved the Earth passionately, as someone who already carried and so would initiate the changes we must make in order for life to survive.

A simple story to set the context. Wendy attended a workshop I offered in Topanga. We spent a long time in silence on the land meeting the spirit of the natural world. At the end, Wendy appeared with a rack of deer antlers on her head. So many of us had walked the land over and over again for years, but no one of us had seen the weathered antlers. It had had to be Wendy. Wendy is of the natural world. The earth raised her in her great wisdom. And Wendy, in turn, allowed the earth to raise Noel so that she would grow up wise and compassionate, an advocate for the Earth that would give us hope.

When we, the older generation, think of all the wars we wage, the viciousness of the technology, the violence, alienation, the enormous suffering that combatants and non-combatants endure, the fact that the wars never end and come home to us again and again as they did on November 7th, we think of Noel as someone who knew and lived peace in every cell of her being. Because Noel was intuitively, instinctively, spiritually, even stubbornly, devoted to peace, insisting on peaceful and heartful solutions to conflict, we had hope that she would set right what we failed to do.

When we think of all the Ian David Longs who went to war and suffered such moral injury that drives one mad, and when we admit that we failed to stop these wars, failed to provide healing, then we had hope that Noel would know how to meet his ravaged soul, that she would have known to take such a one to the forest, to the desert, to rock climb, to be washed clean in the sea, to the healing of the natural world, that she would have listened to his unspeakable story, brought comfort, helped him make amends and heal before… We had hope in Noel as a healer.

And when we watch everything of value torn apart by injustice and hate, we had faith that Noel had the fierce and devoted love that could meet such circumstances and those who suffered them and could bring the peace that only a true, determined, intelligent, courageous, undaunted, entirely authentic love can bring.

And so now that she is gone, what hope?

I reframe here a poem I wrote some years ago:

When a great body and soul

is broken by catastrophe

We take the pieces into ourselves

And we are made whole thereby.

We have all heard who Noel was, what she lived by, what she embodied, the true, pure and spiritual nature of her being.

Let us take a moment of silence, and take what we know of her deep. Deep into ourselves. Let us breathe in the parts of her that are most important to each of us – whether it be

her profound love and participation in beauty, music, dance, art, words,

her indomitable healing spirit,

her love and devotion to the natural world and all beings,

her insistence upon justice,

her lived conviction that violence is unnecessary and peace is necessary

and possible

and her loving nature, her determination to meet every situation in real

time with love, courageously and passionately.

Take these in. Breathe her spirit into you. Let it inscribe itself in you.

What is hope?

Noel was hope.

And now she is in you, is of us.

She is not gone, she is dispersed within us.

And so hope?

You are hope.

You are now the hope that will bring peace and restore life to this ravaged planet.

Bless you all.

September 12, 2018

The Lost Etiquette: Sharon English Converses with Deena Metzger at Dark Mountain Project

Recently I was interviewed by Sharon English. The interview I have posted below can be found at The Dark Mountain Project.

I met Deena Metzger in 2014 when she visited Canada to teach a weekend workshop on story and healing. As a teacher and writer myself, deeply interested in how writers can address ecological and social crisis, the workshop theme intrigued me. Deena’s biography described her as “a poet, novelist, essayist, storyteller, teacher, healer and medicine woman” who has been devoted to “investigating Story as a form of knowing and healing.” Excitingly, her notion of ‘healing’ seemed radically extended to include “life-threatening diseases, spiritual and emotional crises, as well as community, political and environmental disintegration.” Still, I knew nothing of the extraordinary individual awaiting me, with whom I’ve been fortunate to continue learning and seeking since.

“Who do we have to become to find the forms and sacred language with which to meet these times?” Deena’s life is certainly one possible answer to her own question. Spanning many decades, her work interweaves activism, art and community building with a rare courage to cross frontiers such as the reality of animal intelligence and agency, and the reality of spirit. Her book The Woman Who Slept With Men to Take the War Out of Them was published in one volume in 1977 with Tree, one of the first books written about breast cancer. The book coincided with the printing of the exuberant post-mastectomy photograph of Deena, called “Tree” or “Warrior”, which has been shared worldwide. It took the third publisher, North Atlantic Press, to have the courage when reissuing Tree to print the poster image on the cover. Since writing Entering the Ghost River: Meditations on the Theory and Practice of Healing (2002), which came out of a decade’s work with animals and Indigenous medicine, Deena has held ReVisioning Medicine gatherings for those trained in Western medicine who long to be healers too and also Daré, a monthly gathering for the community at her home in Topanga, California, and a practice that has spread to other North American cities.

Drawing on myth, Indigenous and other wisdom traditions that have been lifetime pre-occupations, Deena has articulated a vision of why and how we must create a culture that does no harm, called the . She’s recently been touring her new novel, A Rain of Night Birds (2017), which addresses ecological crisis and the necessity of bridging the disparity between Indigenous and Western mind. I caught up with her on Skype in August, 2017.

Sharon English: Let’s start with the invitation which Dark Mountain made with Issue 12, which led us to this conversation: an invitation to reflect on our experience of the sacred in a time of unravelling and how that experience might call our contemporary assumptions into question.

Deena Metzger: I think the essential questions are: How is the sacred implicit in whatever possibilities exist for this time? How can our own experiences of the sacred inform our activism? I think you know that, for me, the only hope that I really see for a future for the planet and all life is following the direction and the guidance of the sacred, being aware of its presence.

SE: Yes, yet the sacred and spirit have had a very bad rap. On the one hand, because religion has been put into the service of the dominator culture, many people associate the spiritual with something oppressive or at least conforming. On the other hand, New Age spirituality seems too bound up in the individual – ‘what’s sacred to you’ – to be relevant in a time of unravelling.

DM: I would prefer not to go there. Because if we go there, we’re focusing on the human, when what we’re called to do is to listen and respond to the sacred. How you and I have experienced the sacred, without reference to how it has not been experienced, feels very important to me. What feels essential is speaking about the sacred, and the awareness that this is what Indigenous people have always known and what has sustained them. My interest is in returning to the old wisdom and bringing it back so that the planet can be saved.

Terrence Green, one of the protagonists in A Rain of Night Birds, is clear about this as he, a climatologist, faces the reality of the planet’s unravelling. A mixed blood man, he became Chair of the Department of Earth and Environmental Studies, but his grief awakens the Native teachings transmitted to him by his grandfather. This is 2007. It’s the time of the International Panel on Climate Change. In this stunning report, he finds two small references to TEK: traditional ecological knowledge. Within thousands of pages of scientific data and analysis, he finds two small references, four or five sentences. This both moves and grieves him. His response is to go to the Mountain where his grandfather took him as a child to teach him about the old ways. As he prays to the Mountain and apologises for having left the red path – even though he left it for reasons that were theoretically on behalf of his people, learning what Westerners were doing so that he could help Native people adjust to the way we are living – he realises exactly how much he betrayed his soul for entering into Western living:

He was speaking aloud, but he didn’t know to whom he was speaking, or whether he was speaking, or in a dream of speaking, or in a spirit realm to which he had been transported by what appeared to be injury, but was also something else. [The injury is the Earth’s injury and his own injury.] There was a thousand different ways he’d accepted that spirits are real although Western mind was a miasma of denial that entered through the cracks and fissures of his being, like water seeping through rock, undermining the original structure of all things. (174)

I think that’s all that needs to be said: Western mind IS a miasma of denial that undermines the true nature of the world. So then, how can we make our way back? How do we accept Spirit as reality, not illusion? And what is Spirit saying to us?

You’ve recently had a remarkable dream that is teaching you/us a lost etiquette. I’ve also had such dreams. They come from Spirit. This novel was given to me by Spirit. These gifts are our “evidence”. They offer guidance. They teach us what is important to bring forth. When I heard your dream, I knew that you were being guided and were dreaming in the old ways, which means not for you personally or psychologically, but as a teaching for all of us.

SE: I’ll retell it now for readers. The dream came early this summer:

I’m attending a council of Indigenous people held inside an orca. First, I’m shown that the orca has two spaces: a small opening in its body that has something to do with healing, like a healing chamber, and also a larger opening like two skin flaps that part and lead into a sizable circular chamber, like a tent, with a floor and walls of black and white orca skin. I enter.

Inside, a group of Indigenous people are sitting in a circle around a simple altar of animal skin with objects placed on it. An elder sits on the far side. I sit down in the circle, directly across from the elder. I’m the only non-Indigenous person. It occurs to me that I’m not sitting in the right place, that maybe I shouldn’t be facing the elder so directly, so I change places in the circle so I’m more to the side. I feel like I’m being invited here for the first time and am learning the protocol.

One of the biggest teachings for me, in opening to the sacred and spirit, has been coming to understand dreams as language or communication that aren’t only about the isolated individual. That dreams can hold meaning for the community, and come through us, not only from our own psyches.

The great danger at the core of Western thinking is our belief that we are the world, the centre of things. So when we respond to the crises in our world we assume it’s up to us to figure them all out – the very kind of self-involved thinking that got us here. We have no sense of living in a field of relationships with other creatures who possess their own traditions, wisdom, consciousness and agency. That when it comes to our world crises, everybody, human and nonhuman, needs to be at the table. At this point it’s we who need to be guided by whales and spirit, or Spirit-as-Whales.

DM: The dream is about more than being guided by Whales. In the dream, you enter into the Whale, and the council is taking place inside the Whale. In other words, in the dream, Whale consciousness is the sacred world we enter. That’s the territory in which this Indigenous council is taking place. As the Whales or other beings live in our consciousness, we are now living within the Whales’ consciousness.

Furthermore, you are aware that you don’t know how to deport yourself in this setting. As more of us experience the presence of the sacred, we have to figure out the protocol, the etiquette for approaching this realm and those within it. We have to re-learn what our Indigenous ancestors knew and also discover how to proceed at this time in history. Here the sacred is within the body-mind of the great ones, in this case, Whale. We have to go into the internal place where the field exists, the consciousness we need. In a sense like the story of Jonah – except we hope to keep living there, not leave.

When a dream like this comes as a teaching for the community, it’s not going to be an easy dream to understand. We’re going to have to sit with what it means. You and I may not know all its dimensions as we’re speaking to each other, so we carry it for as long as necessary, bringing it to others who might help to reveal its profound mystery. We do this because we understand that such dreams can be the source of wisdom. In the old, old days, no matter which Indigenous culture one was part of, if there was something going on that was really difficult or terrible, one would ask for a dream. The community of elders would gather and hope that a dream would come, or someone would come and say they’d had a dream, and people would gather to listen to it. This happened with your dream: you responded to it in the old, old ways by bringing it to me. We talked about what it might mean, and then I suggested that you take this dream to the community. And you did. Those you’ve shared it with have pondered it with you. We are not asking the personal meaning of the dream, ‘What is this dream for your life?’ Rather we’re considering, ‘What is this dream telling us?’

I had an experience this weekend that feels related: I went Whales watching in the Channel Islands off the coast of southern California. There were so many Whales, such a profusion of wildlife, that the guides on the boat were astonished. Again and again they marvelled that they had never seen anything like it. I’ve been speaking with friends who live along the coast who’ve also been seeing a remarkable profusion of Whales this summer. Stan Rushworth, a Native novelist, author of the remarkable book Going to Water, speaks of the surprising occurrences of Whales coming in close to the shore and breaching over and over when he is walking on the beach. Cynthia Travis, who founded and directs the grassroots peace-building NGO in Liberia, everyday gandhis, and who lives overlooking the sea in Ft. Bragg, CA, has also been startled by the profusion of Whales.

Cynthia was on the Whales watching boat with me as was Cheryl Potts, with whom I share my land in Topanga. Cynthia and I have travelled to Africa to many times. At the moment when we found ourselves among several different kinds of Whales, and kinds of Dolphins and Sea Lions, Cynthia wondered if the Whales were coming to us deliberately in the way that the Elephants came to us. So maybe your dream isn’t accidental, but part of a consciousness being held by Whales that’s alerting us humans to what’s happening on the planet – and to the fact that there’s a protocol required. That’s the sacred knowledge being transmitted: first, that we’re within Whales’ consciousness, and second, that there’s an etiquette we have to learn.

SE: In Amitav Ghosh’s book The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, he notes how various thinkers have begun to use the word uncanny in relation to macro ecological events because, he says, they’re recognising what we’ve long turned away from: “the presence and proximity of the nonhuman interlocutors” (30). Having to learn the etiquette for approaching the nonhuman and the sacred – that’s such a different teaching than this idea that ecological events are uncanny, a concept that suggests the world of the nonhuman is unsettling, inexplicable, and even creepy. There’s a great humility required to accept that we’re being called to learn, not to figure things out, but to learn or recover the ways of relationship to the sacred.

DM: It’s important what you said, “not to figure it out”. We don’t have the capacity to figure it out, and that’s humbling. We learn some from the old, old ways: we learn things about making offerings, about meeting the nonhuman and the sacred with profound respect and honour, and then, we listen deeply to the teachings that come. So your dream was the thing-in-itself and also about it: you went into the sacred and were taught how to approach the sacred.

SE: Yes. In approaching the sacred, council seems integral, as was pointed out in the dream. And your process, whether in Daré or ReVisioning Medicine or writing workshops, is to teach by holding council. Can we talk about what council is and why it’s part of our relationship to the sacred?

DM: It goes back to what you said, ‘It’s not about us figuring things out.’ When I was visiting a nganga, a medicine person in Zimbabwe, Mandaza Kandemwa, alongside whom I worked as a healer on many occasions over ten years, he said something that’s guided me since: “When human beings sit in council, the spirits sit in council as well.” His sense is that the sacred is a council: it’s the interconnection of all the different points of light. It’s the net of Indra. A field of knowing constituted of all the different parts in interrelationship – that is what the sacred is.

When you sat in council within the Whale, you were with those elders who’d been informed for generations and generations about the way to meet the sacred. They had their own individual and collective experiences, and so we understand that you have to meet the sacred wholly, and then the holy is there. Part of the relationship with Spirit involves stepping away from the horrifically narcissistic dangers of individualism. Everywhere we locate the sacred, we also find interconnection, as in the natural world.

SE: When you bring up the problem of individuism, I think about how challenging it is to get people to think broadly and collectively in terms of what’s good for all humanity, let alone all beings on the planet. There’s this fear reaction of collective action and purpose or identity, really a kind of twisted up notion of collectivity as entirely negative, group think, et cetera. Sorry, I know you don’t want to focus on our problems.

DM: Because we keep refocusing on ourselves, it’s important to keep coming back to ‘Let’s not talk about our problems’ precisely because it’s so hard to stay away from focusing on ourselves, whether as individuals or as humans. So this is a practice of looking at what’s been invisible to us, which is the presence of Spirit. A practice of going back to what was shown, rather than what we didn’t see or don’t want to see.

Was there an initiatory event that opened you to recognizing your materialistic way of thinking? How did Spirit reveal itself to you?

SE: For me, following the writer’s path has meant that I’m always making meaning my focus, my purpose, and attuned to listening to and observing the world, trying to see and feel the patterns. So although I come from no spiritual tradition – on the contrary, an anti-spiritual tradition via my upbringing, education and culture – I think being an artist primed me to be receptive to the sacred.

Now I can look back and see how Spirit has guided my life, if I view it that way. There wasn’t a key initiatory event, but what did open me up most consciously to the sacred was spending more time in nature. I did a great deal of that after writing my second book, in part because I’d become injured and needed to stay off the computer, in part because I felt evermore compelled to immerse myself in nature. I found myself growing desperately alarmed at the ecocidal path that our culture is on, and it seemed to me that we were never going to come to our senses without recognising our own limits and narcissism. I came to see and feel, deeply, that the human is not the centre of reality but part of the whole, and that the whole is animate, conscious, intentional – everything we are and more. As well, I’ve always paid attention to dreams, and about a decade ago I experienced a couple that were powerfully, undeniably spiritual in tone and images. These helped push me into humbly recognising the arrogance and limits of my materialist mindset – and also the tremendous loss of spiritual and life wisdom from our ancestors that’s happened as a result of our obsession with mechanical, materialistic thinking.

DM: We’re at a critical moment, and it’s a moment of consciousness. Stepping into a world where Spirit exists – stepping into, finally, the real world, being able to remember it as Indigenous people have known it forever – is for us Westerners as great a mental shift as it’s possible to make. Like the consequences for Copernicus and Galileo when they understood that the Earth went around the sun.

SE: An apt analogy!

DM: Yes, the sun. It’s not that Spirit is the sun; it’s that Spirit is the entire universe, and we circle a light that it shines to us and that keeps us in relationship to others who are circling this light, and are warmed by it, and have life because of it. Because we’re at a certain distance from it, but not too far, the structure of the solar system as we know it isn’t a bad analogy, though not the whole.

But here’s the important moment: we either talk about what we didn’t know, or we talk about what we see. Once you know the reality of ecocide, once you say that word, nothing else has to be said except what follows from that knowledge, what you now see/understand differently: what you see in the natural world that’s different, what your experiences from Spirit have been – that’s the mind shift. I can’t emphasise how important this is. If we continue to look at and articulate and be obsessed with what’s wrong then we find ways to meet it that are familiar in terms of how we solve problems, and they’re not working. I’m not saying leaving them altogether, for some people have to focus on familiar problem solving, but for those of us who have felt and experienced and seen the irrefutable presence of Spirit, the next step is learning how to listen and take direction. We really don’t know what to do to restore the natural world and sanity without Spirit’s teachings; everything we have ‘done’ until now has brought us to this place of devastation. So your dream comes: Learn the protocol; enter into the mind-body-being-universe of Whales. Then …? Then we’ll see what becomes possible and how.

In 2010, I had a dream: I won a contest, and the prize was that I would go to New York and be part of a program, after which I would be or think like and move in the world like an Indigenous elder. When I woke up, I understood, after sitting with the dream for some time, that it was instruction. Not about going to New York, but learning how to be an Indigenous elder. I enrolled myself, so to speak, in my own program, and as I think back upon it now – I didn’t realise it until this moment – I changed to a great extent what I was reading. I started reading far more Indigenous literature and thinking than I had before; I started listening even more deeply to my Indigenous friends and colleagues; and I asked myself at every moment when I had to make a decision, How might an uncolonised, Indigenous elder respond to this situation? In part I’m doing that with you now, coming back again and again saying, What do we see, what are our experiences? That dream, and my understanding that it was instruction, changed me, and we would not be having this conversation if I’d not responded to my dream in that way.

Before writing A Rain of Night Birds, when I was in the desert and hoping for the next novel, I heard a voice saying, ‘You know. Her name is Sandra Birdswell and she is a meteorologist.’ And I said, ‘No, I don’t know!’ Yet even as I responded, I knew that I was being given something by Spirit and had a mandate to write whatever came, which required enormous research, thinking, listening, yielding and daring. Daring to say the book was given in that way. Daring to write things that I knew would be challenged if not ridiculed. But it was what was given, and the next six years verified that it was given because of all the other events and revelations that came and made a whole of the book.

If there had just been a voice one time and I never heard anything again, that would be meaningless. But when we listen and enter into a field, a council if you will, of events and synchronicities and revelations and experiences that we ourselves could never have created on our own, then we know we’re in the domain of the sacred.

SE: In this sense holding council, even with just one person, seems crucial to yielding to the sacred. We need support for daring to listen to, take seriously, and follow our experiences of the sacred in these times. Even you, with all your years of following the sacred, still had that feeling of, Wow, I really have to say things that might seem totally out there to people! Yet you did, and it seems to me that having a council and/or a spiritually focused community made that possible.

DM: It’s essential. When you sit in a circle with people and the conversation is about Spirit, and how Spirit has come or how Spirit is directing, the fact that Spirit exists is the ground. So, everything you say is enhanced by or grounded in Spirit’s existence, and our relationship to it, and the possibility that that kind of alliance might in fact save the planet. You have the assumption that you want it saved and that you’d give everything to do that – that forms a different kind of conversation. Our conversation right now is grounded in the councils we’ve been in and those assumptions. We don’t step out of that when we step out of those councils.

SE: It’s beautiful and supportive what you just said, that once we sit in council, those councils go with us. You’ve spoken of the field as a kind of container as well.

DM: The field is composed of all of us and we emerge out of it, as if born out of it but never leaving it. It is of us and we are of it.

In January 2017, when I met with the Elephant people in Thula Thula, South Africa, I understood that our interactions could only occur because we were in a field of consciousness together: we were brought to a meeting place and had an interaction that was articulate and specific.

SE: And that field existed because you responded to the call of Elephant?

DM: Right. And again and again over 18 years. In retrospect, I understand that I had to show up all those other times, and every time I did, there was an interaction, the field was being built. It wasn’t only that I showed up, but that the Elephant people showed up as well.

When I went to Thula Thula in 2017 and could say, without awkwardness, ‘I’m going to meet the Elephant people,’ capital E, I understood that I could no longer write ‘Elephant’ with a small ‘e’ any more than I would write Canadian with a small ‘c.’ But then, I could no longer write ‘Cow’ with a small ‘c’ either because the experience with the Elephant people taught me that they are as humans are: conscious beings who exercise spiritual intent.

As I write these days and capitalize the different species or peoples, my consciousness changes. Because then, I’m always in a kind of council with them, a council that extends because we sit in council with the humans as well as the nonhumans, and our human minds change.

SE: How powerful it is to make that seemingly small change on the page: from small ‘e’ to capital ‘E.’ I’ve been disturbed for a long time now by our human-centric narratives in literature, how these reinforce a poisonous and frankly wrong-headed worldview. Amitav Ghosh observes that although the nonhuman had and has agency in many narrative traditions, in modern Western literature nonhuman agency has been relegated to “the outhouses of science fiction and fantasy” (66). Making that shift in capitalisation loosens our grip on the narrative, so we start to perceive and tell different kinds of stories. It’s a radical change, and also a return to the old ways and understandings.

DM: Suppose an Inuit man or woman said, ‘I had this dream and Bear came and talked to me about how to walk out on the ice and fish.’ She wouldn’t say ‘a bear came’ but Bear came, capital B implicit. When you read that, you’re getting an entirely different understanding just by that capital: Bear came, a profound spiritual being, and it really happened. To incorporate that into our literature or writing or speaking is to change our minds, to create a literature or conversation through which the earth and our consciousness can be restored.

Imagine if we began to think of our writing and speaking as having to do with connection and relationship rather than indulging a language that’s so combative and therefore constantly honours combat. There are many things we can do to undermine war, but one of them is to stop thinking in terms of war and to stop referencing war constantly.

SE: Part of what’s so unbearable about listening to mainstream news, political discussions, economics, and so on is the incessant repetition of military metaphors, a combative way of looking at each other and the world. What you’ve called the Literature of Restoration offers a way changing our stories, our language.

DM: Changing our stories, changing our paragraphs, changing our sentences, changing our words. The Literature of Restoration is not something developed yet; it’s something I’ve been thinking about and gave a name to, an opportunity for all of us to discover what it might be. I can’t do it alone and shouldn’t attempt it. Perhaps, there’s nothing any of us should do alone except to be in solitude with Spirit at times when we need it.

I was in a circle with a woman who was trying to think about how she might speak differently. She was speaking of a woman she’d been with in Nicaragua, and said, ‘Listening to her, I was held captive.’ And then she said, ‘Wait a moment. Held captive? No, that’s not what happened.’ She had to find language that did not speak of violence in order to honour.

The Native American writer Robin W. Kimmerer, who wrote Braiding Sweetgrass, speaks of how the English language is so full of ‘I’ instead of we, and how it makes Spirit an object. She notes that the Anishinaabe language does not divide the world between he, she and it, but between animate and inanimate. This distinction asserts an entirely different world. Here’s what she says:

Imagine your grandmother standing at the stove in her apron and someone says, ‘Look, it is making soup. It has gray hair.’ We might snicker at such a mistake, at the same time that we recoil. In English, we never refer to a person as ‘it.’ Such a grammatical error would be a profound act of disrespect. ‘It’ robs a person of selfhood and kinship, reducing a person to a thing. And yet in English, we speak of our beloved Grandmother Earth in exactly that way, as ‘it.’ The language allows no form of respect for the more-than-human beings with whom we share the Earth […] In our language there is no ‘it’ for birds or berries […] The grammar of animacy is applied to all that lives: sturgeon, mayflies, blueberries, boulders and rivers. We refer to other members of the living world with the same language that we use for our family. Because they are our family.

SE: So in learning the protocol for approaching the sacred, we have receiving certain dreams as spiritual communication and guidance for the community; approaching the sacred wholly by sitting in council together; entering into a conscious field with our nonhuman family; and finally, changing our language to shift our minds.

One more thing feels important to speak about: beauty. In your book Entering the Ghost River, you tell a story about coming to understand Spirit through beauty. Beauty is central to your work and what you’ve articulated in the . Beauty seems to me one way – maybe the way – that everyone feels the sacred, though they might not call it that. Does part of the protocol we’re learning involve honouring beauty?

DM: Beauty is experienced in many different ways. But the visual is also at its heart, and the ability to see beauty is a great gift. I’m using the word ‘see’ very deliberately because seeing is so important to English speakers. Visually, from my point of view, there is not a single millimetre on the Earth – the part that hasn’t been touched by human hands – that isn’t beautiful. Beauty is a force, and it’s also how Spirit reveals itself. In terms of a path, seeing beauty and then honouring it is a way of recognising the presence of Spirit.

The story I tell in Entering the Ghost River happened in Canyon de Chelly, Arizona. My ex-husband brought me there for the first time, knowing it was going to be an incredible experience. As we were driving, we hit incredible storms and went through one of those initiation stories: the rains come, the mud is thick, everything is dangerous, you can’t get there, the car doesn’t go, you run out of food, you meet a stranger, you stop at a little hut and ask for directions and the directions they give you are impossible to follow, so you keep going and trying, and you pick up this old man … [Laughs.] I’m so scared at this point, the roads are so slippery and we’re on a cliff, that I get out and walk while Michael is driving the car and this elder, this Native American Diné man is sitting in the back of it eating the nuts that we gave him – it was all we had to offer – and he’s laughing!

We dropped him off about 1,000 yards from the entrance to Canyon de Chelly, and when we got to the very entrance, the road was completely dry.

Michael then did this amazing thing. He blindfolded me and took me to this outlook, and I looked out at this extraordinary canyon and the mountains around it. It was sunset, and the lightning and the colours of the sunset and clouds were the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen in my life. We’d arrived at a moment that could not have been choreographed, that would not have happened if we hadn’t arrived exactly at sunset because we had gotten stuck in the mud – one of those. I looked at the cliffs, which are rust colour and blue from the copper, extraordinarily beautiful, painted, and I knew: This Beauty comes from a great Heart. Love – heart – are at the very core of creation. Beauty and Heart are the same, just different ways of seeing, different manifestations.

That was so powerful an impression – and I mean it pressed itself into my consciousness – that I’ve been marked by it. It’s a living mark: I’m always aware of Beauty, the beauty that’s the essence of the natural world, and that’s changed my life as much as anything, and confirmed the reality of the Divine. Our collective task, as I see it and expressed it in that book, is to re-establish the sacred universe and render the signature of the Divine visible – beauty.

To read or hear other interviews with Deena go .

The Lost Etiquette: Sharon English in conversation with Deena Metzger

Recently I was interviewed by Sharon English. The interview I have posted below can be found at The Dark Mountain Project.

I met Deena Metzger in 2014 when she visited Canada to teach a weekend workshop on story and healing. As a teacher and writer myself, deeply interested in how writers can address ecological and social crisis, the workshop theme intrigued me. Deena’s biography described her as “a poet, novelist, essayist, storyteller, teacher, healer and medicine woman” who has been devoted to “investigating Story as a form of knowing and healing.” Excitingly, her notion of ‘healing’ seemed radically extended to include “life-threatening diseases, spiritual and emotional crises, as well as community, political and environmental disintegration.” Still, I knew nothing of the extraordinary individual awaiting me, with whom I’ve been fortunate to continue learning and seeking since.

“Who do we have to become to find the forms and sacred language with which to meet these times?” Deena’s life is certainly one possible answer to her own question. Spanning many decades, her work interweaves activism, art and community building with a rare courage to cross frontiers such as the reality of animal intelligence and agency, and the reality of spirit. Her book The Woman Who Slept With Men to Take the War Out of Them was published in one volume in 1977 with Tree, one of the first books written about breast cancer. The book coincided with the printing of the exuberant post-mastectomy photograph of Deena, called “Tree” or “Warrior”, which has been shared worldwide. It took the third publisher, North Atlantic Press, to have the courage when reissuing Tree to print the poster image on the cover. Since writing Entering the Ghost River: Meditations on the Theory and Practice of Healing (2002), which came out of a decade’s work with animals and Indigenous medicine, Deena has held ReVisioning Medicine gatherings for those trained in Western medicine who long to be healers too and also Daré, a monthly gathering for the community at her home in Topanga, California, and a practice that has spread to other North American cities.

Drawing on myth, Indigenous and other wisdom traditions that have been lifetime pre-occupations, Deena has articulated a vision of why and how we must create a culture that does no harm, called the . She’s recently been touring her new novel, A Rain of Night Birds (2017), which addresses ecological crisis and the necessity of bridging the disparity between Indigenous and Western mind. I caught up with her on Skype in August, 2017.

Sharon English: Let’s start with the invitation which Dark Mountain made with Issue 12, which led us to this conversation: an invitation to reflect on our experience of the sacred in a time of unravelling and how that experience might call our contemporary assumptions into question.

Deena Metzger: I think the essential questions are: How is the sacred implicit in whatever possibilities exist for this time? How can our own experiences of the sacred inform our activism? I think you know that, for me, the only hope that I really see for a future for the planet and all life is following the direction and the guidance of the sacred, being aware of its presence.

SE: Yes, yet the sacred and spirit have had a very bad rap. On the one hand, because religion has been put into the service of the dominator culture, many people associate the spiritual with something oppressive or at least conforming. On the other hand, New Age spirituality seems too bound up in the individual – ‘what’s sacred to you’ – to be relevant in a time of unravelling.

DM: I would prefer not to go there. Because if we go there, we’re focusing on the human, when what we’re called to do is to listen and respond to the sacred. How you and I have experienced the sacred, without reference to how it has not been experienced, feels very important to me. What feels essential is speaking about the sacred, and the awareness that this is what Indigenous people have always known and what has sustained them. My interest is in returning to the old wisdom and bringing it back so that the planet can be saved.

Terrence Green, one of the protagonists in A Rain of Night Birds, is clear about this as he, a climatologist, faces the reality of the planet’s unravelling. A mixed blood man, he became Chair of the Department of Earth and Environmental Studies, but his grief awakens the Native teachings transmitted to him by his grandfather. This is 2007. It’s the time of the International Panel on Climate Change. In this stunning report, he finds two small references to TEK: traditional ecological knowledge. Within thousands of pages of scientific data and analysis, he finds two small references, four or five sentences. This both moves and grieves him. His response is to go to the Mountain where his grandfather took him as a child to teach him about the old ways. As he prays to the Mountain and apologises for having left the red path – even though he left it for reasons that were theoretically on behalf of his people, learning what Westerners were doing so that he could help Native people adjust to the way we are living – he realises exactly how much he betrayed his soul for entering into Western living:

He was speaking aloud, but he didn’t know to whom he was speaking, or whether he was speaking, or in a dream of speaking, or in a spirit realm to which he had been transported by what appeared to be injury, but was also something else. [The injury is the Earth’s injury and his own injury.] There was a thousand different ways he’d accepted that spirits are real although Western mind was a miasma of denial that entered through the cracks and fissures of his being, like water seeping through rock, undermining the original structure of all things. (174)

I think that’s all that needs to be said: Western mind IS a miasma of denial that undermines the true nature of the world. So then, how can we make our way back? How do we accept Spirit as reality, not illusion? And what is Spirit saying to us?

You’ve recently had a remarkable dream that is teaching you/us a lost etiquette. I’ve also had such dreams. They come from Spirit. This novel was given to me by Spirit. These gifts are our “evidence”. They offer guidance. They teach us what is important to bring forth. When I heard your dream, I knew that you were being guided and were dreaming in the old ways, which means not for you personally or psychologically, but as a teaching for all of us.

SE: I’ll retell it now for readers. The dream came early this summer:

I’m attending a council of Indigenous people held inside an orca. First, I’m shown that the orca has two spaces: a small opening in its body that has something to do with healing, like a healing chamber, and also a larger opening like two skin flaps that part and lead into a sizable circular chamber, like a tent, with a floor and walls of black and white orca skin. I enter.

Inside, a group of Indigenous people are sitting in a circle around a simple altar of animal skin with objects placed on it. An elder sits on the far side. I sit down in the circle, directly across from the elder. I’m the only non-Indigenous person. It occurs to me that I’m not sitting in the right place, that maybe I shouldn’t be facing the elder so directly, so I change places in the circle so I’m more to the side. I feel like I’m being invited here for the first time and am learning the protocol.

One of the biggest teachings for me, in opening to the sacred and spirit, has been coming to understand dreams as language or communication that aren’t only about the isolated individual. That dreams can hold meaning for the community, and come through us, not only from our own psyches.

The great danger at the core of Western thinking is our belief that we are the world, the centre of things. So when we respond to the crises in our world we assume it’s up to us to figure them all out – the very kind of self-involved thinking that got us here. We have no sense of living in a field of relationships with other creatures who possess their own traditions, wisdom, consciousness and agency. That when it comes to our world crises, everybody, human and nonhuman, needs to be at the table. At this point it’s we who need to be guided by whales and spirit, or Spirit-as-Whales.

DM: The dream is about more than being guided by Whales. In the dream, you enter into the Whale, and the council is taking place inside the Whale. In other words, in the dream, Whale consciousness is the sacred world we enter. That’s the territory in which this Indigenous council is taking place. As the Whales or other beings live in our consciousness, we are now living within the Whales’ consciousness.

Furthermore, you are aware that you don’t know how to deport yourself in this setting. As more of us experience the presence of the sacred, we have to figure out the protocol, the etiquette for approaching this realm and those within it. We have to re-learn what our Indigenous ancestors knew and also discover how to proceed at this time in history. Here the sacred is within the body-mind of the great ones, in this case, Whale. We have to go into the internal place where the field exists, the consciousness we need. In a sense like the story of Jonah – except we hope to keep living there, not leave.

When a dream like this comes as a teaching for the community, it’s not going to be an easy dream to understand. We’re going to have to sit with what it means. You and I may not know all its dimensions as we’re speaking to each other, so we carry it for as long as necessary, bringing it to others who might help to reveal its profound mystery. We do this because we understand that such dreams can be the source of wisdom. In the old, old days, no matter which Indigenous culture one was part of, if there was something going on that was really difficult or terrible, one would ask for a dream. The community of elders would gather and hope that a dream would come, or someone would come and say they’d had a dream, and people would gather to listen to it. This happened with your dream: you responded to it in the old, old ways by bringing it to me. We talked about what it might mean, and then I suggested that you take this dream to the community. And you did. Those you’ve shared it with have pondered it with you. We are not asking the personal meaning of the dream, ‘What is this dream for your life?’ Rather we’re considering, ‘What is this dream telling us?’

I had an experience this weekend that feels related: I went Whales watching in the Channel Islands off the coast of southern California. There were so many Whales, such a profusion of wildlife, that the guides on the boat were astonished. Again and again they marvelled that they had never seen anything like it. I’ve been speaking with friends who live along the coast who’ve also been seeing a remarkable profusion of Whales this summer. Stan Rushworth, a Native novelist, author of the remarkable book Going to Water, speaks of the surprising occurrences of Whales coming in close to the shore and breaching over and over when he is walking on the beach. Cynthia Travis, who founded and directs the grassroots peace-building NGO in Liberia, everyday gandhis, and who lives overlooking the sea in Ft. Bragg, CA, has also been startled by the profusion of Whales.

Cynthia was on the Whales watching boat with me as was Cheryl Potts, with whom I share my land in Topanga. Cynthia and I have travelled to Africa to many times. At the moment when we found ourselves among several different kinds of Whales, and kinds of Dolphins and Sea Lions, Cynthia wondered if the Whales were coming to us deliberately in the way that the Elephants came to us. So maybe your dream isn’t accidental, but part of a consciousness being held by Whales that’s alerting us humans to what’s happening on the planet – and to the fact that there’s a protocol required. That’s the sacred knowledge being transmitted: first, that we’re within Whales’ consciousness, and second, that there’s an etiquette we have to learn.

SE: In Amitav Ghosh’s book The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, he notes how various thinkers have begun to use the word uncanny in relation to macro ecological events because, he says, they’re recognising what we’ve long turned away from: “the presence and proximity of the nonhuman interlocutors” (30). Having to learn the etiquette for approaching the nonhuman and the sacred – that’s such a different teaching than this idea that ecological events are uncanny, a concept that suggests the world of the nonhuman is unsettling, inexplicable, and even creepy. There’s a great humility required to accept that we’re being called to learn, not to figure things out, but to learn or recover the ways of relationship to the sacred.

DM: It’s important what you said, “not to figure it out”. We don’t have the capacity to figure it out, and that’s humbling. We learn some from the old, old ways: we learn things about making offerings, about meeting the nonhuman and the sacred with profound respect and honour, and then, we listen deeply to the teachings that come. So your dream was the thing-in-itself and also about it: you went into the sacred and were taught how to approach the sacred.

SE: Yes. In approaching the sacred, council seems integral, as was pointed out in the dream. And your process, whether in Daré or ReVisioning Medicine or writing workshops, is to teach by holding council. Can we talk about what council is and why it’s part of our relationship to the sacred?

DM: It goes back to what you said, ‘It’s not about us figuring things out.’ When I was visiting a nganga, a medicine person in Zimbabwe, Mandaza Kandemwa, alongside whom I worked as a healer on many occasions over ten years, he said something that’s guided me since: “When human beings sit in council, the spirits sit in council as well.” His sense is that the sacred is a council: it’s the interconnection of all the different points of light. It’s the net of Indra. A field of knowing constituted of all the different parts in interrelationship – that is what the sacred is.

When you sat in council within the Whale, you were with those elders who’d been informed for generations and generations about the way to meet the sacred. They had their own individual and collective experiences, and so we understand that you have to meet the sacred wholly, and then the holy is there. Part of the relationship with Spirit involves stepping away from the horrifically narcissistic dangers of individualism. Everywhere we locate the sacred, we also find interconnection, as in the natural world.

SE: When you bring up the problem of individuism, I think about how challenging it is to get people to think broadly and collectively in terms of what’s good for all humanity, let alone all beings on the planet. There’s this fear reaction of collective action and purpose or identity, really a kind of twisted up notion of collectivity as entirely negative, group think, et cetera. Sorry, I know you don’t want to focus on our problems.

DM: Because we keep refocusing on ourselves, it’s important to keep coming back to ‘Let’s not talk about our problems’ precisely because it’s so hard to stay away from focusing on ourselves, whether as individuals or as humans. So this is a practice of looking at what’s been invisible to us, which is the presence of Spirit. A practice of going back to what was shown, rather than what we didn’t see or don’t want to see.

Was there an initiatory event that opened you to recognizing your materialistic way of thinking? How did Spirit reveal itself to you?

SE: For me, following the writer’s path has meant that I’m always making meaning my focus, my purpose, and attuned to listening to and observing the world, trying to see and feel the patterns. So although I come from no spiritual tradition – on the contrary, an anti-spiritual tradition via my upbringing, education and culture – I think being an artist primed me to be receptive to the sacred.

Now I can look back and see how Spirit has guided my life, if I view it that way. There wasn’t a key initiatory event, but what did open me up most consciously to the sacred was spending more time in nature. I did a great deal of that after writing my second book, in part because I’d become injured and needed to stay off the computer, in part because I felt evermore compelled to immerse myself in nature. I found myself growing desperately alarmed at the ecocidal path that our culture is on, and it seemed to me that we were never going to come to our senses without recognising our own limits and narcissism. I came to see and feel, deeply, that the human is not the centre of reality but part of the whole, and that the whole is animate, conscious, intentional – everything we are and more. As well, I’ve always paid attention to dreams, and about a decade ago I experienced a couple that were powerfully, undeniably spiritual in tone and images. These helped push me into humbly recognising the arrogance and limits of my materialist mindset – and also the tremendous loss of spiritual and life wisdom from our ancestors that’s happened as a result of our obsession with mechanical, materialistic thinking.

DM: We’re at a critical moment, and it’s a moment of consciousness. Stepping into a world where Spirit exists – stepping into, finally, the real world, being able to remember it as Indigenous people have known it forever – is for us Westerners as great a mental shift as it’s possible to make. Like the consequences for Copernicus and Galileo when they understood that the Earth went around the sun.

SE: An apt analogy!

DM: Yes, the sun. It’s not that Spirit is the sun; it’s that Spirit is the entire universe, and we circle a light that it shines to us and that keeps us in relationship to others who are circling this light, and are warmed by it, and have life because of it. Because we’re at a certain distance from it, but not too far, the structure of the solar system as we know it isn’t a bad analogy, though not the whole.

But here’s the important moment: we either talk about what we didn’t know, or we talk about what we see. Once you know the reality of ecocide, once you say that word, nothing else has to be said except what follows from that knowledge, what you now see/understand differently: what you see in the natural world that’s different, what your experiences from Spirit have been – that’s the mind shift. I can’t emphasise how important this is. If we continue to look at and articulate and be obsessed with what’s wrong then we find ways to meet it that are familiar in terms of how we solve problems, and they’re not working. I’m not saying leaving them altogether, for some people have to focus on familiar problem solving, but for those of us who have felt and experienced and seen the irrefutable presence of Spirit, the next step is learning how to listen and take direction. We really don’t know what to do to restore the natural world and sanity without Spirit’s teachings; everything we have ‘done’ until now has brought us to this place of devastation. So your dream comes: Learn the protocol; enter into the mind-body-being-universe of Whales. Then …? Then we’ll see what becomes possible and how.

In 2010, I had a dream: I won a contest, and the prize was that I would go to New York and be part of a program, after which I would be or think like and move in the world like an Indigenous elder. When I woke up, I understood, after sitting with the dream for some time, that it was instruction. Not about going to New York, but learning how to be an Indigenous elder. I enrolled myself, so to speak, in my own program, and as I think back upon it now – I didn’t realise it until this moment – I changed to a great extent what I was reading. I started reading far more Indigenous literature and thinking than I had before; I started listening even more deeply to my Indigenous friends and colleagues; and I asked myself at every moment when I had to make a decision, How might an uncolonised, Indigenous elder respond to this situation? In part I’m doing that with you now, coming back again and again saying, What do we see, what are our experiences? That dream, and my understanding that it was instruction, changed me, and we would not be having this conversation if I’d not responded to my dream in that way.

Before writing A Rain of Night Birds, when I was in the desert and hoping for the next novel, I heard a voice saying, ‘You know. Her name is Sandra Birdswell and she is a meteorologist.’ And I said, ‘No, I don’t know!’ Yet even as I responded, I knew that I was being given something by Spirit and had a mandate to write whatever came, which required enormous research, thinking, listening, yielding and daring. Daring to say the book was given in that way. Daring to write things that I knew would be challenged if not ridiculed. But it was what was given, and the next six years verified that it was given because of all the other events and revelations that came and made a whole of the book.

If there had just been a voice one time and I never heard anything again, that would be meaningless. But when we listen and enter into a field, a council if you will, of events and synchronicities and revelations and experiences that we ourselves could never have created on our own, then we know we’re in the domain of the sacred.

SE: In this sense holding council, even with just one person, seems crucial to yielding to the sacred. We need support for daring to listen to, take seriously, and follow our experiences of the sacred in these times. Even you, with all your years of following the sacred, still had that feeling of, Wow, I really have to say things that might seem totally out there to people! Yet you did, and it seems to me that having a council and/or a spiritually focused community made that possible.