Franz Kiekeben's Blog, page 2

August 27, 2020

IF THE SHOE WERE ON THE OTHER FOOT

What Christian wouldn’t be incensed by the following statement, especially if informed that it was made by a professor of philosophy at one of this nation’s venerated institutions of higher learning? The statement, ostensibly an attempt to explain the real reasons underlying the religious beliefs of millions of our fellow citizens, appears to be purposely disrespectful:

“Christian belief,” this professor declared, “does not arise from assessment of evidence, but from stubborn closed-mindedness; it does not have its origin in the desire for knowledge but in arrogance and contempt. Christianity is the suppression of truth by hatred, the outgrowth of small-minded prejudice. In short, it is bigotry that is the mother of belief.”

Even strong atheists might admit that this goes too far. No wonder so many religious individuals feel as if they’re under siege. These days, it really does seem that there’s a war on certain types of belief.

Many among the religious who would be offended by statements like the above are, however, perfectly happy with similar pronouncements provided they come from their own side. They complain about biased professors whose hatred of faith is clearly evident, but in turn ignore — or even applaud — religious intolerance aimed at nonbelievers. As an example, consider the fact that the above statement is in reality a paraphrase, and that the original actually reads as follows:

“Atheism is not the result of objective assessment of evidence, but of stubborn disobedience; it does not arise from the careful application of reason but from willful rebellion. Atheism is the suppression of truth by wickedness, the cognitive consequence of immorality. In short, it is sin that is the mother of unbelief.”

My paraphrase consisted essentially of changing it from a statement about atheism to one about Christianity, along with the replacement of its abusive epithets by reasonably equivalent ones so as to make it all “fit.” The tone in the original is every bit as rude and obnoxious. The only difference is which side it’s on. And yet, this passage is the central thesis of a book that has been praised by many believers.

That book, The Making of an Atheist, by James Spiegel, a philosopher who teaches in a small religious university in Indiana, goes on to say that the atheist has a “depraved mind” that blinds him to God and ethics, [p. 54] and that “precipitated by immoral indulgences,” he “willfully rejects God.” [p. 113] According to Spiegel, atheism “is not at all a consequence of intellectual doubts.” Reason is not involved. “For the atheist,” he says, “the missing ingredient is not evidence but obedience.” [p. 11]

Positive reviews by readers on Amazon praise the work as “thought-provoking,” “impressive,” and “profound,” and suggest that it really explains the mind-set of nonbelievers. What would these people say if the shoe were on the other foot?

[Originally published at Debunking Christianity ]

“Christian belief,” this professor declared, “does not arise from assessment of evidence, but from stubborn closed-mindedness; it does not have its origin in the desire for knowledge but in arrogance and contempt. Christianity is the suppression of truth by hatred, the outgrowth of small-minded prejudice. In short, it is bigotry that is the mother of belief.”

Even strong atheists might admit that this goes too far. No wonder so many religious individuals feel as if they’re under siege. These days, it really does seem that there’s a war on certain types of belief.

Many among the religious who would be offended by statements like the above are, however, perfectly happy with similar pronouncements provided they come from their own side. They complain about biased professors whose hatred of faith is clearly evident, but in turn ignore — or even applaud — religious intolerance aimed at nonbelievers. As an example, consider the fact that the above statement is in reality a paraphrase, and that the original actually reads as follows:

“Atheism is not the result of objective assessment of evidence, but of stubborn disobedience; it does not arise from the careful application of reason but from willful rebellion. Atheism is the suppression of truth by wickedness, the cognitive consequence of immorality. In short, it is sin that is the mother of unbelief.”

My paraphrase consisted essentially of changing it from a statement about atheism to one about Christianity, along with the replacement of its abusive epithets by reasonably equivalent ones so as to make it all “fit.” The tone in the original is every bit as rude and obnoxious. The only difference is which side it’s on. And yet, this passage is the central thesis of a book that has been praised by many believers.

That book, The Making of an Atheist, by James Spiegel, a philosopher who teaches in a small religious university in Indiana, goes on to say that the atheist has a “depraved mind” that blinds him to God and ethics, [p. 54] and that “precipitated by immoral indulgences,” he “willfully rejects God.” [p. 113] According to Spiegel, atheism “is not at all a consequence of intellectual doubts.” Reason is not involved. “For the atheist,” he says, “the missing ingredient is not evidence but obedience.” [p. 11]

Positive reviews by readers on Amazon praise the work as “thought-provoking,” “impressive,” and “profound,” and suggest that it really explains the mind-set of nonbelievers. What would these people say if the shoe were on the other foot?

[Originally published at Debunking Christianity ]

Published on August 27, 2020 19:26

August 18, 2020

IS GOD JUST?

[Another summer re-run published at

Debunking Christianity

.]

We nonbelievers claim that a perfectly good, loving being would never have created hell, but according to most Christians we are simply wrong. God is loving, they say, but he is also just — and justice demands that evil-doers be punished. Without hell, after all, where would the Hitlers, Stalins, and Ted Bundys of this world end up? In heaven?

This is a common argument, which means that many must find it persuasive, but my guess is that those who do simply haven't given it sufficient thought. It's very easy to see the flaws in it.

To begin with, hell isn't only for serious evil-doers: standard Christian doctrine maintains that we are all deserving of eternal punishment and that anyone who doesn't accept God's offer of salvation ends up there. A second thing to keep in mind is that even the worst evil-doers aren't necessarily sent to hell — not if at some point they become sincere believers. Ted Bundy, for instance, claimed to have accepted Jesus before being executed, and if that's true then on the standard view he did end up in heaven.

One therefore cannot justify hell on the grounds that evil-doers must be punished. But more importantly, can one still maintain that God is just given this doctrine? Does it make sense that all of us are deserving of eternal punishment, or that those who accept Jesus are forgiven?

Let's begin with why everyone supposedly merits eternal damnation. One common reason offered for this is that God, due to his moral perfection, has standards that are so high that no one is good enough to meet them. Even if you are a saint, you aren't perfect: at the very least, you've probably told a few white lies. And that, the argument goes, makes you bad enough, in God's eyes, to merit the worst form of punishment.

But now consider an analogy. Suppose a father finds out his teenage daughter lied about when she returned home from a party: she said she was back by 10 (as she was supposed to have been) even though she didn't actually make it home until 10:15. By the above logic, if this father punished her by chaining her to the basement wall for a week and giving her a hundred lashes a day with a belt, that would show that he has very high moral standards. His standards still wouldn't be as high as God's, of course, for the Lord demands far worse punishment for the girl, but they would nevertheless be much loftier than those of the majority of parents out there.

As to the second question — whether those who accept Jesus's offer of salvation deserve to be forgiven — consider that while Bundy is experiencing eternal bliss, any non-Christian who spent her entire life helping others and doing nothing but good deeds still goes to hell. All I can say is that if you think that's right, you have a very bizarre sense of justice.

The heinousness of this entire doctrine is somewhat mitigated by the (nowadays rather common) claim that hell isn't as terrible as advertised. Maybe it just means annihilation. Or perhaps it means spending eternity apart from God (which, however, is still supposed to be a very undesirable thing). But no matter what one says about it, the basic idea remains entirely unfair. Believing in Christianity — or in Islam, or any other dogma — does not make one the slightest bit more ethical than not believing, and thus cannot be a sound basis for distinguishing those who merit forgiveness from those who do not.

We nonbelievers claim that a perfectly good, loving being would never have created hell, but according to most Christians we are simply wrong. God is loving, they say, but he is also just — and justice demands that evil-doers be punished. Without hell, after all, where would the Hitlers, Stalins, and Ted Bundys of this world end up? In heaven?

This is a common argument, which means that many must find it persuasive, but my guess is that those who do simply haven't given it sufficient thought. It's very easy to see the flaws in it.

To begin with, hell isn't only for serious evil-doers: standard Christian doctrine maintains that we are all deserving of eternal punishment and that anyone who doesn't accept God's offer of salvation ends up there. A second thing to keep in mind is that even the worst evil-doers aren't necessarily sent to hell — not if at some point they become sincere believers. Ted Bundy, for instance, claimed to have accepted Jesus before being executed, and if that's true then on the standard view he did end up in heaven.

One therefore cannot justify hell on the grounds that evil-doers must be punished. But more importantly, can one still maintain that God is just given this doctrine? Does it make sense that all of us are deserving of eternal punishment, or that those who accept Jesus are forgiven?

Let's begin with why everyone supposedly merits eternal damnation. One common reason offered for this is that God, due to his moral perfection, has standards that are so high that no one is good enough to meet them. Even if you are a saint, you aren't perfect: at the very least, you've probably told a few white lies. And that, the argument goes, makes you bad enough, in God's eyes, to merit the worst form of punishment.

But now consider an analogy. Suppose a father finds out his teenage daughter lied about when she returned home from a party: she said she was back by 10 (as she was supposed to have been) even though she didn't actually make it home until 10:15. By the above logic, if this father punished her by chaining her to the basement wall for a week and giving her a hundred lashes a day with a belt, that would show that he has very high moral standards. His standards still wouldn't be as high as God's, of course, for the Lord demands far worse punishment for the girl, but they would nevertheless be much loftier than those of the majority of parents out there.

As to the second question — whether those who accept Jesus's offer of salvation deserve to be forgiven — consider that while Bundy is experiencing eternal bliss, any non-Christian who spent her entire life helping others and doing nothing but good deeds still goes to hell. All I can say is that if you think that's right, you have a very bizarre sense of justice.

The heinousness of this entire doctrine is somewhat mitigated by the (nowadays rather common) claim that hell isn't as terrible as advertised. Maybe it just means annihilation. Or perhaps it means spending eternity apart from God (which, however, is still supposed to be a very undesirable thing). But no matter what one says about it, the basic idea remains entirely unfair. Believing in Christianity — or in Islam, or any other dogma — does not make one the slightest bit more ethical than not believing, and thus cannot be a sound basis for distinguishing those who merit forgiveness from those who do not.

Published on August 18, 2020 19:15

May 29, 2020

IS THERE EVIDENCE THAT THERE ARE NO GODS?

I was recently involved in an online discussion in which a reason I hadn't previously seen was offered for preferring negative to positive atheism. (By negative atheism, I mean the mere lack of belief in any gods, and by positive atheism, the belief that there are no gods. And the fact that one usually needs to explain this is one reason I prefer the traditional terminology.)

There are better and worse reasons for being only a negative atheist. But the one that was argued by my opponent in the discussion was pretty weak — and if it is accepted by others who call themselves atheists, they really should be aware of that.

Briefly, my opponent's argument was that one should only believe when there is evidence; that there is no evidence that there are no gods; and therefore that to positively disbelieve in such beings is completely unjustified.

I suspect some might accept this argument as a result of thinking of evidence exclusively as direct evidence. One can have direct evidence that there are horses by, for example, seeing some. But one cannot have direct evidence that there are no unicorns by seeing none. This, however, ignores indirect evidence. And there is plenty of that regarding unicorns.

One is justified in positively disbelieving in unicorns when one knows certain things about this supposed creature — for instance, that the earliest reports of it were based on long-horned animals depicted in profile (and as a result showing only one horn), as well as on descriptions of rhinos to ancient Greeks who had never seen them; that the spiral tusks of narwhals were sometimes found on beaches and thought to be unicorn horns; that no unicorn or unicorn skeleton has ever been found (which would be very unlikely, given that it is supposedly a large animal); and so on. All this points to the unicorn being a mythical creature — and as that is by far the most likely conclusion, it is reasonable to hold that unicorns aren't real.

Similar kinds of things can be said about gods. There is evidence that gods are human inventions, and even reasonable explanations for why human beings invented them. There are things we know about our existence (e.g., that we are evolved, physical entities) that make the existence of beings who are like us in many respects (e.g., having minds much like ours), yet exist in a supernatural realm or have supernatural powers, extremely unlikely at best. There is the fact that no god, and no act of a god, has ever been observed (there are of course supposed exceptions to this, but the best explanations for them do not require positing any deities) — yet for all of the gods that humans have believed in, this absence is as much of a problem as the absence of unicorns is for unicorn belief. Finally (though of course I wouldn't expect people in general to know this), there is the argument which I made in The Truth about God, that on the traditional meaning of “god”, a god must have libertarian free will — which rules out their existence if libertarian free will is impossible because there is no middle ground between the determined and the random.

Now, one does not have to accept any of these points as conclusive. And one might have other reasons for being a negative atheist. But to claim that positive atheists are mistaken because there is no evidence against the existence of gods is unreasonable.

[Originally published at Debunking Christianity ]

There are better and worse reasons for being only a negative atheist. But the one that was argued by my opponent in the discussion was pretty weak — and if it is accepted by others who call themselves atheists, they really should be aware of that.

Briefly, my opponent's argument was that one should only believe when there is evidence; that there is no evidence that there are no gods; and therefore that to positively disbelieve in such beings is completely unjustified.

I suspect some might accept this argument as a result of thinking of evidence exclusively as direct evidence. One can have direct evidence that there are horses by, for example, seeing some. But one cannot have direct evidence that there are no unicorns by seeing none. This, however, ignores indirect evidence. And there is plenty of that regarding unicorns.

One is justified in positively disbelieving in unicorns when one knows certain things about this supposed creature — for instance, that the earliest reports of it were based on long-horned animals depicted in profile (and as a result showing only one horn), as well as on descriptions of rhinos to ancient Greeks who had never seen them; that the spiral tusks of narwhals were sometimes found on beaches and thought to be unicorn horns; that no unicorn or unicorn skeleton has ever been found (which would be very unlikely, given that it is supposedly a large animal); and so on. All this points to the unicorn being a mythical creature — and as that is by far the most likely conclusion, it is reasonable to hold that unicorns aren't real.

Similar kinds of things can be said about gods. There is evidence that gods are human inventions, and even reasonable explanations for why human beings invented them. There are things we know about our existence (e.g., that we are evolved, physical entities) that make the existence of beings who are like us in many respects (e.g., having minds much like ours), yet exist in a supernatural realm or have supernatural powers, extremely unlikely at best. There is the fact that no god, and no act of a god, has ever been observed (there are of course supposed exceptions to this, but the best explanations for them do not require positing any deities) — yet for all of the gods that humans have believed in, this absence is as much of a problem as the absence of unicorns is for unicorn belief. Finally (though of course I wouldn't expect people in general to know this), there is the argument which I made in The Truth about God, that on the traditional meaning of “god”, a god must have libertarian free will — which rules out their existence if libertarian free will is impossible because there is no middle ground between the determined and the random.

Now, one does not have to accept any of these points as conclusive. And one might have other reasons for being a negative atheist. But to claim that positive atheists are mistaken because there is no evidence against the existence of gods is unreasonable.

[Originally published at Debunking Christianity ]

Published on May 29, 2020 14:39

April 22, 2020

A VISIT TO THE CREATION MUSEUM

[Since we are all stuck at home right now and cannot visit museums, here is an updated version of a post about my visit to Ken Ham's sad excuse for one. I hope this helps fill a void until you can actually go there and see all of its wonders for yourself.]  Ken Ham's “unnatural history” museum in Petersburg, Kentucky is, as you probably know, devoted to a literal interpretation of the Bible. It claims to present evidence that the earth is about 6000 years old, that dinosaurs coexisted with humans, that there was a worldwide flood around 2350 BCE, and so on.

Ken Ham's “unnatural history” museum in Petersburg, Kentucky is, as you probably know, devoted to a literal interpretation of the Bible. It claims to present evidence that the earth is about 6000 years old, that dinosaurs coexisted with humans, that there was a worldwide flood around 2350 BCE, and so on.

It is a bizarre experience from the moment you walk in.

One of the first things you come across inside is an animatronic display of a child next to a couple of velociraptors. (Dinosaurs are a big part of the attraction here, starting with the stegosaurus on the parking lot gate: the owners know it's a way to attract kids to the place.)

The velociraptor display is problematic, however, and not just because it's on the scientific level of The Flintstones. You see, according to the information presented in the museum, all creatures were vegetarian prior to the Fall: this means that lions could sleep with lambs and, apparently, children could play with velociraptors. It was the eating of the forbidden fruit that introduced hardship into the world, thereby turning some animals into predators. But of course, there were no children until after the Fall. How, then, could a child have a velociraptor for a pet? (Moreover, the child in this display is clothed, which is something no one would be before the eating of the forbidden fruit. As everyone knows, Adam and Eve started out as nudists.)

Once you get past the velociraptor display, you enter the main exhibits. Here, visitors are first informed that different scientists can view exactly the same data yet come to radically different conclusions: some see fossils and think they are millions of years old, others understand them to have been around no more than a few thousand years; some see the Grand Canyon and think it formed gradually, others see it and conclude it was the result of an immense flood; it all depends on what interpretation you bring to the data. As one sign puts it, “dinosaur fossils don't come with tags.” This is a big part of the museum's message, designed to make ignorant visitors think that the biblical interpretation is at least as valid as the scientific one.

Eventually, the claims go beyond merely leveling the field, and science begins to be presented as inferior to biblical authority. For, given that the empirical evidence is open to more than one interpretation, to truly know the past we need the evidence of one who was there and who wrote it all down. And that someone was of course God. In one of the displays, a boy is shown saying (by means of a speech bubble) that he's never heard any of this stuff in school!

The message that one can either trust fallible human reason or God's infallible word is repeated throughout. (The fact that one has to use fallible human reason to conclude that the Bible is God's word is of course conveniently ignored.)

Ignoring God's word is said to be the cause of the modern world's problems, and this leads to the next section, the “Culture in Crisis” exhibit — a dark, subway-like tunnel in which all the evils of the modern, Darwin-believing world are represented: there is lots of graffiti, and talk of teen pregnancy, infidelity, and abortions. Visitors then go through a history of the world that takes them from the creation of light through the garden of Eden, the Fall (dramatically described as “the worst day in the history of the universe”), Noah's ark (where you can actually see dinosaurs embarking, as well as a couple of their babies inside — see picture above), the repopulating of the world after the Flood, the Tower of Babel, and finally a film (which I didn't bother to see) about “the last Adam,” Jesus.

Visitors then go through a history of the world that takes them from the creation of light through the garden of Eden, the Fall (dramatically described as “the worst day in the history of the universe”), Noah's ark (where you can actually see dinosaurs embarking, as well as a couple of their babies inside — see picture above), the repopulating of the world after the Flood, the Tower of Babel, and finally a film (which I didn't bother to see) about “the last Adam,” Jesus.

Many of the claims made throughout are supported by nothing more than the authority of scripture. For instance, to the question, “did dinosaurs evolve from birds?” the hilarious answer given is that “God made birds on day 5 and land animals on day 6. Dinosaurs are land animals, so they were created the day after birds.” This is obviously something that all those scientists who believe birds are descended from dinosaurs failed to consider!

Other times, though, they try to provide more elaborate explanations. Mostly, these hardly make sense. For instance, the reason they give for why marsupials “were the first mammals buried and preserved after the flood” (for they are found in lower strata) and that, unlike most other mammals, they made it all the way to Australia, is that marsupials, “which have pouches, can nurse their young while moving,” whereas placental mammals, “which nurse their young in the womb, spread out more slowly.”

Often, the claims are just outlandish. My favorite is their suggestion that the super-continent Pangaea broke apart to form today's continents as a result of the Flood. That's some powerful receding water.

The burning question I most wanted answered was why there are no longer any dinosaurs. After all, according to Ham and his people, these creatures were taken aboard the ark, so they didn't all perish in the Flood, as I assumed they would say. One possible answer they give is that people “killed them for food or sport.” (Well, if I remember correctly, Fred Flintstone did use to eat dino burgers.) Another display, however, claims that there might still be dinosaurs around today that no one has yet found.

It must be admitted that the Creation Museum is rather entertaining for nonbelievers. It feels sort of like a cross between the Bible and the old Raquel Welch movie One Million Years B.C. But even though it is funny, it's also sad, especially when one sees the children who are taken there to be misinformed, and who will no doubt become confused when they are taught real science in school. If only they didn't have all those animatronic dinosaurs.

[Originally published at Debunking Christianity ]

Ken Ham's “unnatural history” museum in Petersburg, Kentucky is, as you probably know, devoted to a literal interpretation of the Bible. It claims to present evidence that the earth is about 6000 years old, that dinosaurs coexisted with humans, that there was a worldwide flood around 2350 BCE, and so on.

Ken Ham's “unnatural history” museum in Petersburg, Kentucky is, as you probably know, devoted to a literal interpretation of the Bible. It claims to present evidence that the earth is about 6000 years old, that dinosaurs coexisted with humans, that there was a worldwide flood around 2350 BCE, and so on.It is a bizarre experience from the moment you walk in.

One of the first things you come across inside is an animatronic display of a child next to a couple of velociraptors. (Dinosaurs are a big part of the attraction here, starting with the stegosaurus on the parking lot gate: the owners know it's a way to attract kids to the place.)

The velociraptor display is problematic, however, and not just because it's on the scientific level of The Flintstones. You see, according to the information presented in the museum, all creatures were vegetarian prior to the Fall: this means that lions could sleep with lambs and, apparently, children could play with velociraptors. It was the eating of the forbidden fruit that introduced hardship into the world, thereby turning some animals into predators. But of course, there were no children until after the Fall. How, then, could a child have a velociraptor for a pet? (Moreover, the child in this display is clothed, which is something no one would be before the eating of the forbidden fruit. As everyone knows, Adam and Eve started out as nudists.)

Once you get past the velociraptor display, you enter the main exhibits. Here, visitors are first informed that different scientists can view exactly the same data yet come to radically different conclusions: some see fossils and think they are millions of years old, others understand them to have been around no more than a few thousand years; some see the Grand Canyon and think it formed gradually, others see it and conclude it was the result of an immense flood; it all depends on what interpretation you bring to the data. As one sign puts it, “dinosaur fossils don't come with tags.” This is a big part of the museum's message, designed to make ignorant visitors think that the biblical interpretation is at least as valid as the scientific one.

Eventually, the claims go beyond merely leveling the field, and science begins to be presented as inferior to biblical authority. For, given that the empirical evidence is open to more than one interpretation, to truly know the past we need the evidence of one who was there and who wrote it all down. And that someone was of course God. In one of the displays, a boy is shown saying (by means of a speech bubble) that he's never heard any of this stuff in school!

The message that one can either trust fallible human reason or God's infallible word is repeated throughout. (The fact that one has to use fallible human reason to conclude that the Bible is God's word is of course conveniently ignored.)

Ignoring God's word is said to be the cause of the modern world's problems, and this leads to the next section, the “Culture in Crisis” exhibit — a dark, subway-like tunnel in which all the evils of the modern, Darwin-believing world are represented: there is lots of graffiti, and talk of teen pregnancy, infidelity, and abortions.

Visitors then go through a history of the world that takes them from the creation of light through the garden of Eden, the Fall (dramatically described as “the worst day in the history of the universe”), Noah's ark (where you can actually see dinosaurs embarking, as well as a couple of their babies inside — see picture above), the repopulating of the world after the Flood, the Tower of Babel, and finally a film (which I didn't bother to see) about “the last Adam,” Jesus.

Visitors then go through a history of the world that takes them from the creation of light through the garden of Eden, the Fall (dramatically described as “the worst day in the history of the universe”), Noah's ark (where you can actually see dinosaurs embarking, as well as a couple of their babies inside — see picture above), the repopulating of the world after the Flood, the Tower of Babel, and finally a film (which I didn't bother to see) about “the last Adam,” Jesus.Many of the claims made throughout are supported by nothing more than the authority of scripture. For instance, to the question, “did dinosaurs evolve from birds?” the hilarious answer given is that “God made birds on day 5 and land animals on day 6. Dinosaurs are land animals, so they were created the day after birds.” This is obviously something that all those scientists who believe birds are descended from dinosaurs failed to consider!

Other times, though, they try to provide more elaborate explanations. Mostly, these hardly make sense. For instance, the reason they give for why marsupials “were the first mammals buried and preserved after the flood” (for they are found in lower strata) and that, unlike most other mammals, they made it all the way to Australia, is that marsupials, “which have pouches, can nurse their young while moving,” whereas placental mammals, “which nurse their young in the womb, spread out more slowly.”

Often, the claims are just outlandish. My favorite is their suggestion that the super-continent Pangaea broke apart to form today's continents as a result of the Flood. That's some powerful receding water.

The burning question I most wanted answered was why there are no longer any dinosaurs. After all, according to Ham and his people, these creatures were taken aboard the ark, so they didn't all perish in the Flood, as I assumed they would say. One possible answer they give is that people “killed them for food or sport.” (Well, if I remember correctly, Fred Flintstone did use to eat dino burgers.) Another display, however, claims that there might still be dinosaurs around today that no one has yet found.

It must be admitted that the Creation Museum is rather entertaining for nonbelievers. It feels sort of like a cross between the Bible and the old Raquel Welch movie One Million Years B.C. But even though it is funny, it's also sad, especially when one sees the children who are taken there to be misinformed, and who will no doubt become confused when they are taught real science in school. If only they didn't have all those animatronic dinosaurs.

[Originally published at Debunking Christianity ]

Published on April 22, 2020 19:38

March 26, 2020

IT'S THE END OF THE WORLD, AGAIN

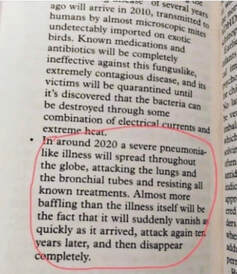

"In around 2020, a severe pneumonia-like illness will spread throughout the globe, attacking the lungs and the bronchial tubes and resisting all known treatments."

"In around 2020, a severe pneumonia-like illness will spread throughout the globe, attacking the lungs and the bronchial tubes and resisting all known treatments."Those are the words of psychic Sylvia Browne in her 2008 book End of Days: Predictions and Prophecies about the End of the World, which which rose to the number two position on Amazon's non-fiction chart after Kim Kardashian tweeted about this. For the naive, the accuracy of Browne's prediction seems impressive. But of course it really isn't.

To begin with, the fact that she stated something that turned out more-or-less right is easy to explain: That there will be a widespread virus, and that it will cause “pneumonia-like” symptoms (why not simply “pneumonia”?) are both fairly safe guesses as to what could happen in a given year – even though one is of course still likely to be wrong when making such a prediction. In this case, Browne just got lucky. But she also made far more incorrect than correct predictions. Kardashian's tweet includes the above picture of the relevant page in Browne's book, and there one can also read that another epidemic would take place in 2010, this one involving a flesh-eating disease transmitted by mites that came from exotic birds. You probably don't remember that epidemic, since it never happened.

Some of the other things Browne incorrectly predicted were that by 2010, a DNA database of every newborn on earth would have been created, that by 2014 microchips would be implanted in people's brains to “override” such conditions as schizophrenia, and that by 2020 no one would be blind or deaf, and many births would take place in “gravity-rigged birthing chambers” (whatever that means). The funniest one I've come across is her claim that fertility rates would drop as end times approached because “fewer and fewer spirits will choose to reincarnate and be around when life on Earth ceases to exist. The fewer the spirits wanting to come here, the fewer the fetuses they’ll need to occupy.”

One prediction that is safe to make is that whenever there is a pandemic, it will bring out the crazy in people. Browne's book isn't popular right now just because of this one prediction; it is popular because it is about the end times. She is being read because people think that they will find information there about the coming apocalypse. And as one might expect, quite a few other charlatans are referring to the current crisis as a sign that the end is near.

Anyone listening to these charlatans should keep in mind that the track record for such predictions isn't exactly good.

[Originally published at Debunking Christianity ]

Published on March 26, 2020 08:31

March 4, 2020

CAN ONE ACTUALLY BELIEVE IN CHRISTIANITY?

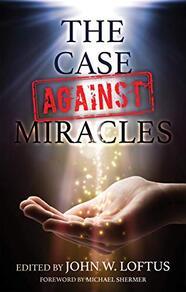

In one of the essays in Loftus's anthology

The Case Against Miracles

, Robert Price raises an issue that is commonly ignored. Price's essay, “Jesus Christ: Docetic Demigod”, concerns the miracles of the Incarnation and of the Virgin Birth, and is well worth reading for the many additional points it makes (as is the rest of the anthology). Here, however, I'm just going to discuss that one issue, for it is something that puts the very idea of Christian belief in doubt.

In one of the essays in Loftus's anthology

The Case Against Miracles

, Robert Price raises an issue that is commonly ignored. Price's essay, “Jesus Christ: Docetic Demigod”, concerns the miracles of the Incarnation and of the Virgin Birth, and is well worth reading for the many additional points it makes (as is the rest of the anthology). Here, however, I'm just going to discuss that one issue, for it is something that puts the very idea of Christian belief in doubt.Price asks whether it is possible to “believe what you cannot understand.”

Consider the doctrine of the Trinity. It does not mean that there are three gods, nor does it mean that there is one God who “reveals himself in different forms,” for those, he points out, are both considered heresies (Tritheism and Modalism respectively). Or consider what is claimed regarding the Incarnation — namely, that Jesus is 100% God and 100% human. It is impossible to make sense of such a thing. After all, it is a logical contradiction. But then what is it that the Christian is supposed to believe?

Some might reply that one can believe each side of these claims separately. There is no inherent difficulty in believing that Jesus is wholly human, nor is there one in believing that he's wholly God. Similarly, one can believe that there is only one God, and one can believe that what we call “God” consists of three distinct persons. Nor does it seem impossible to believe some of these things at one time and some at another (so that one moment I might believe Jesus is entirely human and another that he's entirely divine). But that doesn't solve the problem. For it remains the case that one cannot believe the two sides of the contradictions simultaneously. To do so, one would have to make sense of them — and that, of course, isn't possible.

So-called true believers are more likely to appeal to mystery at this point. The human mind just cannot understand these things, they might say, but that doesn't mean they aren't true. And yet this, once again, won't do. For hidden in that defense is the claim that something is true — namely, the thing that we cannot understand. But what is that something? If we cannot even make sense of it, what are we actually claiming is true?

What Christian doctrine asks one to believe are words that, taken as a whole, fail to be meaningful. The doctrine is therefore literally unbelievable.

[Originally published as a guest-post on the A Tippling Philosopher blog at Patheos.]

Published on March 04, 2020 10:16

February 7, 2020

TRUMP VS. JESUS

In case you missed this, Trump specifically disagreed with Jesus — and did so during the annual National Prayer Breakfast!

In case you missed this, Trump specifically disagreed with Jesus — and did so during the annual National Prayer Breakfast!That event's keynote speaker, Harvard's Arthur Brooks, argued for more unity in our politically divided country, saying that we need to go beyond mere tolerance and actually “love our enemies.” Which is, of course, something Jesus said. Trump, however, who immediately followed Brooks as speaker, began his talk by saying “Arthur, I don't know if I agree with you.”

This is the same guy who said that he has never asked for God's forgiveness — who in fact said that he doesn't “like to have to ask for forgiveness,” adding that he is “good” anyway.

And still evangelicals love him.

And not as an enemy.

Link1

Link2

[Originally published at Debunking Christianity ]

Published on February 07, 2020 17:57

January 10, 2020

METAETHICS FOR ATHEISTS

There's a lot of confusion out there about metaethics. Case in point: I recently ran a promotion of my book Atheism: Q & A, and as a result received a one-star review on Amazon, apparently for no other reason than that the reviewer does not understand what I mean when I claim that morality is subjective. The review makes it clear he sees me as a relativist, for he objects to my position by pointing out that (contrary to what I supposedly imply) slavery is always wrong.

Part of the reason for that misunderstanding may be because many atheists do in fact espouse the kind of relativist view that my critic finds objectionable. But the main problem is the over-simplification that is common in popular discussions and writings on this topic. Most people seem to think there are only two main positions one can take: absolutism/objectivism, which states that there are moral principles that are true for everyone at all times, and relativism/subjectivism, which roughly says that what's right for one person may not be right for another. What's worse, some atheists appear to associate the absolutist view with religion (in effect implying that if one adopts such a position, it is only because of one's religious beliefs), and as a result insist on relativism. And of course, the religious more often than not criticize atheism on the grounds that it is incompatible with objective values, and thus can only lead to relativism.

In addition to all this, the terminology involved isn't used in a consistent way even by philosophers. There are specific views which everyone basically agrees on the meaning of (e.g., non-cognitivism, emotivism, intuitionism), but some of the broader terms are definitely used in more than one way — and none more so than “subjectivism.” No wonder, then, that there is so much confusion.

Before explaining how subjectivism (according to most philosophers who call themselves subjectivists) is different from relativism, let me state some claims that a subjectivist can agree with (and that I in fact agree with):

“Every society that practiced slavery was wrong to do so.”

“The fact that most people in certain societies accepted slavery as permissible did not make it so, not even in those societies.”

“Anyone in a society in which slavery is practiced should oppose it.”

I don't think I can make it any clearer than that. Subjectivism should not be criticized on the grounds that every society that has practiced slavery was wrong to do so. And the reason is simple: the theory is not incompatible with the claim that it is always wrong to own another human being.

The difference between relativism and subjectivism

There are two types of moral relativism, the individual type and the group type. Often, people use “relativism” to mean only the latter, though that's also commonly called “cultural relativism.” But it's probably easier to understand the basic idea behind relativism if we start with the individual variety.

Basically, individual relativism is the view that when someone says, e.g., “x is wrong,” what they are saying is “I disapprove of x.” Thus, if I say slavery is wrong, but plantation-owner Sam says it is right, we can both be saying something true. For what I am doing, in effect, is reporting the fact that I disapprove of slavery, and what he is doing is reporting the fact that he approves of it. It follows that we are both correct!

Group relativism is exactly like this, except relative to societies instead of individuals. Thus, if I say human sacrifice is wrong, I am only saying that, in modern-day America (at least), human sacrifice is frowned upon, whereas if Zahatopolc the Inca says it's right, he is only saying that in his society it's allowed. Thus, once again, we can both be right.

One problem many have with this view is that it apparently makes it impossible to criticize other cultures. But in fact, many relativists endorse this consequence, defending it as the only really tolerant attitude. (Some, when they make this claim, even appear to treat toleration as a moral absolute.)

A subjectivist disagrees. According to subjectivism, moral statements don't state facts about the world (not even about what one or one's society believes). Rather, such statements express one's feelings about moral matters. So, if you say human sacrifice is wrong, you are not reporting what you or those in your group believe. You are expressing your disapproval. And there's no reason to claim that this disapproval doesn't apply to what others, including those in other cultures, believe or practice. That's why as a subjectivist, one can say slavery is wrong, period.

Note: There are many who confuse relativism with the idea that moral principles have exceptions. So if I state as a moral principle that (say) stealing is wrong, someone might object that in certain situations it is perfectly justified. For example, if the only way to save the life of someone who's been bitten by a venomous snake is by stealing some anti-venom, then you should do so. But that's not relativism. Non-relativists are perfectly willing to concede that moral principles have exceptions. Even killing an innocent person can be justified in some cases. All this means is that to correctly state a moral absolute, one would have to qualify the hell out of it. And because that's impractical, we state close approximations instead.

Subjectivism vs. objectivism

Moral objectivism is usually defined as the view that there are moral facts that do not depend on what anyone thinks, and which therefore are universal. It follows that for an objectivist, when someone makes a correct moral statement, they are not only expressing their view, they are also saying something true about reality. Objectivists therefore feel that something crucial is missing in the subjectivist view of things.

However, I can't see what's so important about there being independent moral facts that exist in addition to our moral commitments. When I say slavery is wrong, I'm expressing something I feel very strongly. I would not feel any different about it were I to find out that it is also a fact that slavery is wrong. It wouldn't make me oppose slavery even more.

Maybe objectivists also feel that on their view, it is possible to demonstrate what is really right and wrong (whereas on subjectivism that's obviously ruled out, since there isn't a “really” right or wrong, only how people feel about things). But as everyone should know, that's easier said than done. No one's come up with a theory of ethics that commands universal agreement, or anything close to it.

Lastly, objectivists of course assume that the particular moral views they themselves hold are the factually correct ones. But since people disagree over morality, it follows that if objectivism is true, most objectivists have a bunch of false moral beliefs. You may think slavery is wrong, but those who defend it based on what's in the Bible could be right. A subjectivist at least cannot have that problem. I disapprove of the Bible's acceptance of slavery, and that's that.

For all these reasons (and a few others), I don't see a problem with upholding subjectivism in ethics. It is not a view that in any way diminishes the importance of morality.

[Originally published at Debunking Christianity ]

Part of the reason for that misunderstanding may be because many atheists do in fact espouse the kind of relativist view that my critic finds objectionable. But the main problem is the over-simplification that is common in popular discussions and writings on this topic. Most people seem to think there are only two main positions one can take: absolutism/objectivism, which states that there are moral principles that are true for everyone at all times, and relativism/subjectivism, which roughly says that what's right for one person may not be right for another. What's worse, some atheists appear to associate the absolutist view with religion (in effect implying that if one adopts such a position, it is only because of one's religious beliefs), and as a result insist on relativism. And of course, the religious more often than not criticize atheism on the grounds that it is incompatible with objective values, and thus can only lead to relativism.

In addition to all this, the terminology involved isn't used in a consistent way even by philosophers. There are specific views which everyone basically agrees on the meaning of (e.g., non-cognitivism, emotivism, intuitionism), but some of the broader terms are definitely used in more than one way — and none more so than “subjectivism.” No wonder, then, that there is so much confusion.

Before explaining how subjectivism (according to most philosophers who call themselves subjectivists) is different from relativism, let me state some claims that a subjectivist can agree with (and that I in fact agree with):

“Every society that practiced slavery was wrong to do so.”

“The fact that most people in certain societies accepted slavery as permissible did not make it so, not even in those societies.”

“Anyone in a society in which slavery is practiced should oppose it.”

I don't think I can make it any clearer than that. Subjectivism should not be criticized on the grounds that every society that has practiced slavery was wrong to do so. And the reason is simple: the theory is not incompatible with the claim that it is always wrong to own another human being.

The difference between relativism and subjectivism

There are two types of moral relativism, the individual type and the group type. Often, people use “relativism” to mean only the latter, though that's also commonly called “cultural relativism.” But it's probably easier to understand the basic idea behind relativism if we start with the individual variety.

Basically, individual relativism is the view that when someone says, e.g., “x is wrong,” what they are saying is “I disapprove of x.” Thus, if I say slavery is wrong, but plantation-owner Sam says it is right, we can both be saying something true. For what I am doing, in effect, is reporting the fact that I disapprove of slavery, and what he is doing is reporting the fact that he approves of it. It follows that we are both correct!

Group relativism is exactly like this, except relative to societies instead of individuals. Thus, if I say human sacrifice is wrong, I am only saying that, in modern-day America (at least), human sacrifice is frowned upon, whereas if Zahatopolc the Inca says it's right, he is only saying that in his society it's allowed. Thus, once again, we can both be right.

One problem many have with this view is that it apparently makes it impossible to criticize other cultures. But in fact, many relativists endorse this consequence, defending it as the only really tolerant attitude. (Some, when they make this claim, even appear to treat toleration as a moral absolute.)

A subjectivist disagrees. According to subjectivism, moral statements don't state facts about the world (not even about what one or one's society believes). Rather, such statements express one's feelings about moral matters. So, if you say human sacrifice is wrong, you are not reporting what you or those in your group believe. You are expressing your disapproval. And there's no reason to claim that this disapproval doesn't apply to what others, including those in other cultures, believe or practice. That's why as a subjectivist, one can say slavery is wrong, period.

Note: There are many who confuse relativism with the idea that moral principles have exceptions. So if I state as a moral principle that (say) stealing is wrong, someone might object that in certain situations it is perfectly justified. For example, if the only way to save the life of someone who's been bitten by a venomous snake is by stealing some anti-venom, then you should do so. But that's not relativism. Non-relativists are perfectly willing to concede that moral principles have exceptions. Even killing an innocent person can be justified in some cases. All this means is that to correctly state a moral absolute, one would have to qualify the hell out of it. And because that's impractical, we state close approximations instead.

Subjectivism vs. objectivism

Moral objectivism is usually defined as the view that there are moral facts that do not depend on what anyone thinks, and which therefore are universal. It follows that for an objectivist, when someone makes a correct moral statement, they are not only expressing their view, they are also saying something true about reality. Objectivists therefore feel that something crucial is missing in the subjectivist view of things.

However, I can't see what's so important about there being independent moral facts that exist in addition to our moral commitments. When I say slavery is wrong, I'm expressing something I feel very strongly. I would not feel any different about it were I to find out that it is also a fact that slavery is wrong. It wouldn't make me oppose slavery even more.

Maybe objectivists also feel that on their view, it is possible to demonstrate what is really right and wrong (whereas on subjectivism that's obviously ruled out, since there isn't a “really” right or wrong, only how people feel about things). But as everyone should know, that's easier said than done. No one's come up with a theory of ethics that commands universal agreement, or anything close to it.

Lastly, objectivists of course assume that the particular moral views they themselves hold are the factually correct ones. But since people disagree over morality, it follows that if objectivism is true, most objectivists have a bunch of false moral beliefs. You may think slavery is wrong, but those who defend it based on what's in the Bible could be right. A subjectivist at least cannot have that problem. I disapprove of the Bible's acceptance of slavery, and that's that.

For all these reasons (and a few others), I don't see a problem with upholding subjectivism in ethics. It is not a view that in any way diminishes the importance of morality.

[Originally published at Debunking Christianity ]

Published on January 10, 2020 10:12

December 4, 2019

DOESN’T IT TAKE JUST AS MUCH FAITH TO BE AN ATHEIST?

[The following, posted in Debunking Christianity and in

A Tippling Philosopher

, is an excerpt from my small book, Atheism: Q & A, the Kindle version of which is, for promotional purposes, free December 4 through December 8. The book consists of short entries that answer common criticisms of atheism. The paperback isn't free, but it is inexpensive — and might make a nice Winter Solstice gift for anyone who holds misconceptions about your views.]

[The following, posted in Debunking Christianity and in

A Tippling Philosopher

, is an excerpt from my small book, Atheism: Q & A, the Kindle version of which is, for promotional purposes, free December 4 through December 8. The book consists of short entries that answer common criticisms of atheism. The paperback isn't free, but it is inexpensive — and might make a nice Winter Solstice gift for anyone who holds misconceptions about your views.]The complaint that it takes just as much faith to be an atheist is a strange one. After all, it seems to imply that there’s something wrong with believing on faith — even though in every other context faith is regarded by believers as a virtue. Maybe all that is meant, however, is that everyone is in the same boat, ultimately basing their views on something other than reason and evidence, and that the atheist therefore has no right to single out the religious for criticism.

But is this really true? Does atheism rest on no firmer foundation than religion?

It’s often said that one cannot disprove the existence of God, and that therefore anyone who claims there is no God is going beyond the available evidence. The atheist must as a result rely on faith; if he didn’t do so — if he were sincere about relying only on reason and evidence — he’d be an agnostic instead.

This is a really bad argument, however, and the reason is simple: lack of proof does not mean lack of evidence. I cannot prove that the abominable snowman does not exist, but it doesn’t follow that my disbelief in that creature is a matter of faith: I have good reasons for concluding that the whole thing is a myth, even if these reasons fall short of proof. In fact, to claim that faith is needed whenever there isn’t proof is to claim that just about all our beliefs are a matter of faith; strictly speaking, there’s very little one can prove.

Even if the existence of God can’t be disproven, one can have good reasons for believing God does not exist. For instance, an all-powerful and perfectly good God would almost certainly have created a world with far less suffering than what we find, so at least that kind of deity — the one most theists accept — is at best highly unlikely. One can even reasonably claim to know that no such deity exists: knowledge does not require certainty, for once again, there’s very little we can be certain about. If knowledge required complete certainty, most of our scientific, historical, and even everyday knowledge would go out the window.

One should also be careful about insisting that God can’t be disproven. At least on certain definitions of “God,” his existence can be conclusively ruled out (and in my book The Truth about God I argue that on the traditional meaning of the word “god,” all gods are in fact impossible).

One final comment: it’s interesting that the religious often say their faith can be defended by reason. Their beliefs may be based on faith, but that doesn’t mean they cannot be backed up with hard, logical evidence — or so many theists claim. And yet, when they criticize atheists as being just as dependent on faith, they are obviously implying that atheists have no good reason for their beliefs. Which is it, then? Does faith rule out reason or not? One can’t have it both ways.

Published on December 04, 2019 16:41

November 6, 2019

THE REAL REASON GOD IS A PERFECT BEING

The God most theists believe in isn't merely a powerful non-physical being who created the universe; he is an omnipotent, omniscient, omnipresent, perfectly good and perfectly free being. And apparently male. Theologians might claim that he is also immutable, timeless, perfectly simple, impassible (that is, not affected by anything), and several other things besides. But what reasons could anyone possibly have for believing in such a God?

The God most theists believe in isn't merely a powerful non-physical being who created the universe; he is an omnipotent, omniscient, omnipresent, perfectly good and perfectly free being. And apparently male. Theologians might claim that he is also immutable, timeless, perfectly simple, impassible (that is, not affected by anything), and several other things besides. But what reasons could anyone possibly have for believing in such a God?The standard arguments for God's existence — even assuming that they worked — do not support the above claims. For example, design arguments at best conclude that some intelligent being is responsible for the characteristics found in the universe (or for some of these characteristics). They don't say that this being is all-powerful or all-good; they don't even show that this being created the universe out of nothing (she might only have rearranged previously existing matter), or that this being still exists. Nor do they show that monotheism is more likely than polytheism. Cosmological arguments fare even worse: at best, they show that there is some ultimate cause that is itself uncaused, or that necessarily exists. But by themselves, these arguments do not support the idea that this ultimate cause is an intelligent being, much less that it is a perfectly just and benevolent heavenly father, or one who has any of the other properties claimed by theists.

Then there is what one might call the argument from scripture: the Bible, it is said, shows that God is at least to a great extent as described above. However, the Bible at most only suggests this. It says, for instance, that “with God, all things are possible.” But that is rather vague, and can be interpreted in more than one way. True, if taken at face value, it says God can do anything; but it can also be read more poetically as a suggestion to put one's faith in the very powerful — though not necessarily all-powerful — creator being. And there are other passages in the Bible that if taken at face value are incompatible with God being omnipotent. (The Bible does at least state pretty clearly that God is male. But that's the most ridiculous of the divine properties that believers insist on.)

There are also, of course, the ontological arguments, and those do say that God is omnipotent, perfectly good, and more. But hardly anyone accepts ontological arguments. When they first encounter Anselm's “proof,” most theists suspect that some trick is involved, and rightly so.

It seems clear that the real reason theists accept most of these claims about God is because that is what they want to believe. In the entry on omniscience in The Blackwell Companion to the Philosophy of Religion, George Mavrodes mentions three reasons, besides the Anselmian “perfect-God” theology, why someone might claim God is all-knowing. First, there are biblical passages that “suggest a very wide scope for divine knowledge.” (This has exactly the same problem as the ones used to support belief in an omnipotent God. A “very wide scope” isn't necessarily an all-encompassing one. Plus, there are biblical passages that suggest God isn't all-knowing.) Then there is “the conviction that without an appeal to omniscience one could not maintain a full confidence in God's ability to achieve His purposes in the world.” Finally, there is the idea that God is a being fully worthy or worship, and only a perfect being qualifies as such.

These last two reasons, however, translate to “I believe God is all-knowing for otherwise I wouldn't have as strong as possible a reason for putting my faith in this being.” And if that's a good reason for believing God is all-knowing, or has any of his other commonly-claimed properties, then we might as well believe that carts can pull horses.

[Originally published at Debunking Christianity ]

Published on November 06, 2019 11:36