Maria Haskins's Blog, page 60

April 20, 2015

More about that new science fiction anthology, and a book give-away

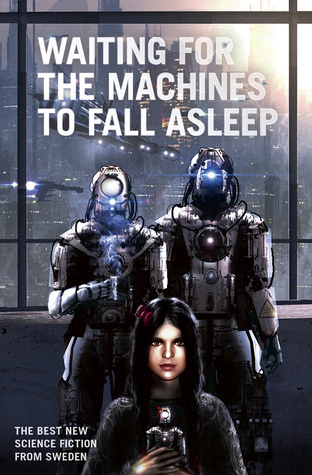

As I mentioned here on the blog recently, my short story “Lost And Found” from my book Odin’s Eye will be included in a soon-to-be-released science fiction anthology titled Waiting For The Machines To Fall Asleep. The anthology is put together by editor Peter Öberg, and will be published by Affront on May 6th, 2015.

You can already pre-order the ebook-version from Amazon: Waiting for the Machines to Fall Asleep in the Kindle store.

I’m very excited and proud to be included in this anthology, which also includes short stories by many other Swedish authors, including Hans Olsson, Boel Bermann, Erik Odeldahl, Ingrid Remvall, Love Kölle, Lupina Ojala, Christina Nordlander, Pia Lindestrand, Jonas Larsson, Tora Greve, Andrew Coulthard, Alexandra Nero, Johannes Pinter, Andrea Grave-Müller, AR Yngve, My Bergström, Anders Blixt, Patrik Centerwall, Björn Engström, KG Johansson, Oskar Källner, Sara Kopljar, Eva Holmquist, Markus Sköld, and Anna Jakobsson Lund.

All the writers are Swedish, and if you are in Sweden, you will be able to find hard-copies of the anthology at these bookstores:

SF-bokhandeln in Gothenburg and Stockholm

English Bookshop in Uppsala

And if you like winning free stuff (who doesn’t?) you can enter this book give-away at Goodreads and win a copy of Waiting For The Machines To Fall Asleep. You can enter until April 30th.

Of course, you can read “Lost And Found” and many more of my short stories right now, if you pick up a copy of Odin’s Eye:

Smashwords (download available in various ebook formats, including epub, mobi for Kindle, txt, and pdf)

Amazon (available at Amazon.com and other Amazon outlets)

Kobo

Barnes & Noble

Apple iBooks

Overdrive

Individual links to all Amazon outlets:

CA / Canada

.com / US

UK / United Kingdom

AU / Australia

DE / Germany

FR / France

ES / Spain

IT / Italy

NL / Netherlands

JP / Japan

BR / Brazil

MX / Mexico

IN / India

April 17, 2015

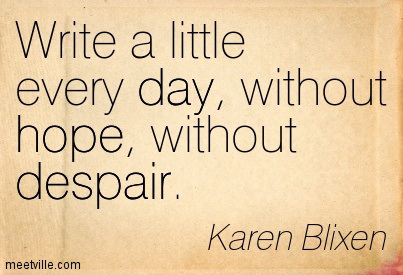

My new mantra

“Write a little every day, without hope, without despair.”

The words are Isak Dinesen’s, AKA Danish writer Karen Blixen. And that is my new creed, mantra, and motto.

Flashback essay: Faceless saviour

Detail of “Intåget i Jerusalem” (“Entering Jerusalem”), watercolour by Berta Hansson (b 1901, d 1994).

I originally wrote this short essay for a special series in the Swedish newspaper Norran in 1993. Various writers chose a painting each from the art-collection belonging to Museum Anna Nordlander in Skellefteå, Sweden. Then, each writer wrote an essay inspired by that particular painting. The essays were later published in a booklet by the museum: “En bild, en tanke” (“A picture, a thought”).

Faceless saviour

Jesus has no face.

It’s kind of odd that the main character in the New Testament is faceless. In modern literature, descriptions of thr characters’ physical attributes are everywhere: there are people with crooked smiles, pointy noses, bedroom eyes, rough hands, and cauliflower ears. Even in Ancient Greece, Homer used vivid language to describe the characters of The Iliad and The Odyssey, informing us that Odysseus had red hair and Athena grey eyes. Yet, you can read the gospels over and over without getting even a hint of what Jesus looked like. Did he have dark or fair hair? Brown or blue eyes? Was he short or tall, fat or thin? Was he disfigured? Scarred? Did he have gaps between his front-teeth? Nobody knows. He is the story from the manger to the cross, but we never, ever get to see him.

The Jesus of the New Testament is a mystery in other ways too. We don’t really get to know him: you know, the real, at-home, in-his-own-skin, everyday Jesus. Occasionally he gives us a parable about the poor and camels, children and loving thy neighbour, but none of his stories seem really personal or character-revealing. None of them begin with “When I was growing up in Nazareth…” or “My mom once told me…”, or even: “One of the things I learned when I was a child…”. Actually, there is very little mention at all of Jesus’ early life in the gospels. The story leaps rather abruptly from his birth to his early thirties (the brief mention of a visit to the temple as a young boy being the only exception). It totally skips the formative years of childhood and adolescence and we don’t find out very much about his family life, either. All of this makes him somewhat of a blank page, and making that page even more blank is the fact that Jesus doesn’t talk much about his emotions: about how he feels.

In today’s world everyone is asked that question:“How does it feel?”; politicians and hockey players, hunters mauled by bears, lottery winners, victims of crime, and celebrities just out of rehab. But no one asks Jesus how it feels. How does it feel to be Jesus? How does it feel to grow up as a supposedly illegitimate child in a small village? How does it feel to believe you’ve been chosen by god? How does it feel to know that all those children were killed by Herod when he tried to have you killed as a baby? How does it feel to know that you will be betrayed by a guy you handpicked as a follower, and then, tortured and executed? All of these questions, and many more, would no doubt be asked of Jesus if he was interviewed on a TV talk-show or by a magazine, or even if he just came over to one of us for a cup of coffee. Yet, as far as we know, none of the disciples ever ask him how it feels, and he never tells anyone about it either.

There is just the one occasion, when we do get some understanding of how it might feel. It’s that night before he is arrested, when Jesus more or less breaks down and asks God to “take this cup from me”. It is perhaps the strangest part in all of the New Testament, and to me it seems quite odd that it’s even included in the text at all. The man who by his life and death, and reported resurrection, creates a new religion; the man who is worshipped as the son of God more than two thousand years later; is asking God to let him pass on the whole thing. What if his prayer had been answered?

Jesus might be faceless in the Bible, but in the movies he has been given plenty of different faces. He has looked like Max von Sydow, Willem Dafoe, Ted Neeley, Robert Powell and James Caviezel. Jesus’ face has also been painted, carved, sculpted, and reproduced in every fashion imaginable. Still, the fact remains that we don’t know if any of these images look anything at all like the real Jesus.

I used to think that the absence of descriptive details in the New Testament turned the face of Jesus into a kind of mirror where people could see their own reflection – God made in our own image: black or white, Jewish or not, catholic or protestant, liberal or conservative. But the more I think about it, the more I believe that maybe there is no mirror. Maybe there is only a gallery of masks, made by us to create the kind of Jesus that we want to see, that we choose to see: Son of God or overrated human being, Messiah or fool, deliverer or oppressor, saviour or opium for the masses, Dafoe or Caviezel.

In the end, does it even matter what Jesus’ face looked like? Obviously the people who wrote the gospels didn’t think so. They were concerned with other things, like divinity and redemption, sin and salvation, heaven and hell, and the end of the world. Facial features, weight and height and the answer to questions like “How does it feel”, didn’t interest them.

Still, I can’t help but wonder about the original face, the first face, the face beyond and beneath all of the masks that we have fashioned through the ages. And I can’t help but wonder what he saw when he looked into his own mirror.

Museum Anna Nordlander.

More about the Swedish artist Berta Hansson. She grew up on a farm, studied to become a teacher, and then worked as a teacher in Fredrika, a small town in northern Sweden. Berta had been interested in drawing and painting from a young age, and in 1938 she studied painting with Leoo Verde. She continued her studies with the painter Brita Nordencreutz, and spent six months at an art-school in Stockholm.

April 16, 2015

That time my poetry was translated into Slovakian

In 1997 two of my poems (written in Swedish) were translated into Slovakian and published in a magazine called Revue Svetovej Literatúry. Being a writer and translator myself, but not able to understand a word of Slovakian, this was both exciting and kind of odd: after all, I couldn’t understand a word of the translations. And even today, Google Translate isn’t that good when it comes to stuff like poetry…

Poetry has to be one of the most difficult things to translate: so much hangs on the sound and rhythm of a word, as well as its actual meaning. I’ve quoted Edward Hirsch on the subject before:

Strictly speaking, total translation is impossible, since languages differ and each language carries its own complex of linguistic resources, historical and social values. This is especially true in poetry, the maximal of language. It is axiomatic that in a poem there is no exact equivalent for the valences of sound, the intonations and sequences of words, the rhythm of separate lines, the weight of accruing stanzas, the totality of musical effects.

Yet, it was a wonderful thing: that someone read my words and then wanted to interpret and translate them into their own language. It feels like a huge compliment, and I am very grateful to Milan Richter for translating my poems.

The translated poems are Naken (“Naked”) from my third collection of poetry, Den Tredje (The Third); and Dräparna (“The Killers”), from my second collection of poetry Honung (Honey).

Right now, I’m considering translating all my own poems that were originally written in Swedish into English, and I’m hoping to get that project finished sometime soon (if I finally get around to starting it!), but I’m under no illusions: it won’t be easy. It makes me think of another quote about translation, this one by Anne Michaels:

Translation is a kind of transubstantiation; one poem becomes another.

That sounds kind of exciting, actually.

If you want to check out Revue Svetovej Literatúry, the website is here.

You can read more about my previously published works, poetry and otherwise, here.

April 12, 2015

My short story in a new science fiction anthology!

My short story “Lost And Found” from Odin’s Eye will be included in Waiting For The Machines To Fall Asleep, an anthology of science fiction from Sweden.

I don’t have a confirmed release date right now, but I’m so excited to be part of this with so many other great writers.

Of course, you can read the short story right now if you pick up Odin’s Eye! It’s available as an ebook from several online retailers:

Smashwords (download available in various ebook formats, including epub, mobi for Kindle, txt, and pdf)

Amazon (available at Amazon.com and other Amazon outlets)

Kobo

Barnes & Noble

Apple iBooks

More info right here.

April 11, 2015

Another new poem: Sparrow

Sparrow

This small bird,

sleeping,

head tucked under wing.

I didn’t see it, I just felt it,

a flutter of wings,

a whisper,

when they lifted you out of me.

And I know

that you already can fly

with closed eyes, closed fists.

Even when you’re sleeping:

that bird-heart trembling in your chest,

that sparrow-dream

tucked under wing.

April 8, 2015

Selfie with dog & an introduction

Selfie with dog.

My name is Maria Haskins. As you might know from looking around this site, I’m a writer and translator, and my new ebook Odin’s Eye – a collection of science fiction short stories – is out right now. I’m working on a science fiction novel, and I blog about writing, translating, books, life, poetry and other things that interest me.

You can also find me elsewhere online:

My website & blog

My Facebook Page

My Smashwords author page

My Goodreads author page

My Amazon Author page

My Twitter

My Pinterest

My Instagram

My Shelfari

The big, beautiful, hairy face in the selfie above belongs to our family dog. He keeps me healthy and reasonably in shape by taking me on walks every day.

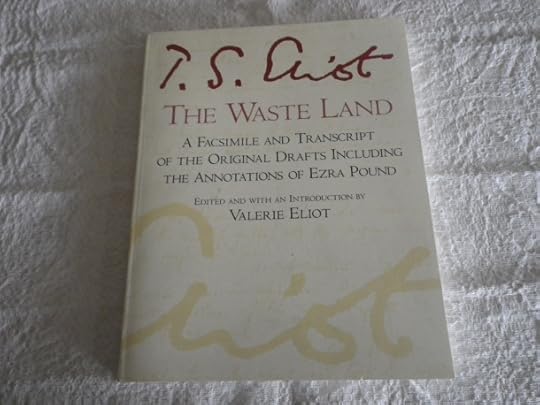

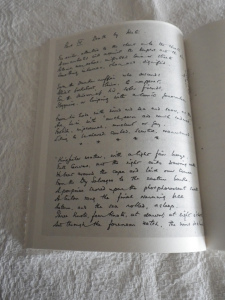

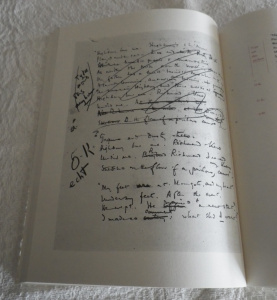

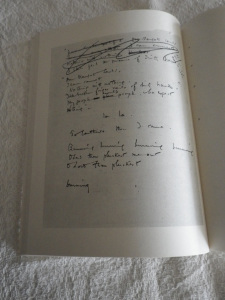

The importance of rewriting & editing: for T.S. Eliot and other writers, too

A few years ago I received this beautiful and rather amazing book as a gift. It’s called The Waste Land: A Facsimile and Transcript of the Original Drafts Including the Annotations of Ezra Pound. Just like the title indicates, the book chronicles the making of T.S. Eliot’s famous poem The Waste Land in astonishing detail, with images of Eliot’s original drafts, as well as editorial comments and notes made by Eliot, his wife (who helped edit the poem), and his friend and main editor Ezra Pound, as they worked on the poem together.

To quote the Amazon sales-blurb:

Each facsimile page of the original manuscript is accompanied here by a typeset transcript on the facing page. This book shows how the original, which was much longer than the first published version, was edited through handwritten notes by Ezra Pound, by Eliot’s first wife, and by Eliot himself.

The Waste Land is one of my favourite poems. It is a rich, bewildering, mesmerizing, and utterly captivating poem that weaves together sounds, lyrics, images, words, and a multitude of quotes from and references to other sources, both ancient and modern: books, myths, legends, prayers, chants, fairy tales, songs, plays, as well as spiritual and religious works. When I read it in high school, it fundamentally changed the way I looked at poetry, writing, and language. It made me realize that language can be used in very different ways than we usually see in more traditional “rhyming poetry”, prose, and everyday writing; and that even though what is said can seem strange and even be difficult to understand, it can capture your imagination and express profound emotions, thoughts, and ideas in a way that speaks to you beyond verbal logic.

When I read The Waste Land, I sometimes feel like I’m immersed in a hallucinatory, feverish vision – a half-dreamed, half-mad, half-lucid stream-of-consciousness. I imagine it to be something like listening to the prophecies of the ancient oracles, high on whatever hallucinogens or trance-inducing prayers and chants they used in their caves or temples, minds caught somewhere between the worlds, between the real and the unreal, between sleep and waking and tripping out. And just like in the prophecies of the oracles, you can find profound truth in Eliot’s words, even if it is not a literal, logical truth.

To me, The Waste Land is a masterpiece, written by a poet at the top of his powers.

What this particular book about the poem shows so well, is that even a masterful writer like Eliot depended on and benefited from severe rewrites and thorough editing. The Waste Land in its original state (i.e. the first draft) was not as good as the final result when the text had been put through the editorial wringer not just once, but repeatedly. I sometimes get the feeling that many people believe that if an author is really good, then the stories or poems just flow from their brain through their pen or keyboard, and comes out fully finished on the page. In my experience, that is not the case. I’m sure it happens occasionally, but more often good writing, good books, good poems, are the result of savage self-editing and a multitude of rewrites by the author, as well as helpful editing from others: call them editors or trusted helpers (in Eliot’s case the main helpers were Ezra Pound and Eliot’s first wife Vivienne Haigh-Wood Eliot).

Having to work at something, doubting it, rewriting it, throwing it out, bringing it back, editing and re-editing, writing and re-writing… all this is part of the creative process, and very often your first draft is a hellish, sub-standard piece of crap – no matter how good the writer.

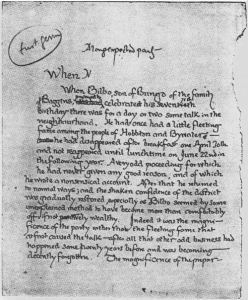

Tolkien’s original first page of The Lord of the Rings.

Consider another one of my favourite literary works: J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. In Tolkien’s first versions of the story, the Strider/Aragorn character was called “Trotter”, and was originally a strange hobbit wearing wooden shoes. He passed through various stages of development (he was even an Elf at one point) before eventually becoming a man, and then the Aragorn character we now know and love. Tolkien’s story developed and changed many times in his rewrites, and I think that in the end, he ended up with something a lot better than his original idea.

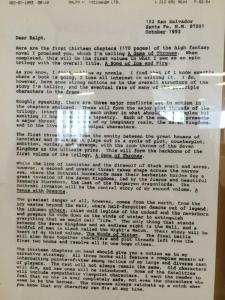

George R.R. Martin’s (alleged) original outline for A Song of Ice And Fire.

The same can be said about George R. R. Martin’s epic A Song of Ice and Fire-saga. In a recently leaked three-page document that was apparently Martin’s original outline of the story, there are many things that seem strange and weird if you’ve read the published books. Arya falls in love with Jon Snow, Daenerys kills Khal Drogo after he kills her brother, and Sansa gives birth to Joffrey’s son. I think most of us would agree that whatever editing and rewriting took place in this case, also changed things for the better.

Seeing The Waste Land take shape in what seems to have been an often tortured and torturous process of scribbled notes, savage cuts, moving and re-inserting text, and an eternity of rewrites and editing, is both fascinating and instructional. It is clear that collaborating with insightful and talented editors was important when Eliot shaped his masterpiece. (I’ve worked with editors, and I know how sensitive and crucial that relationship can be.) Because the poem’s evolution is so well documented, there are even some who argue that The Waste Land was really co-written by Ezra Pound. I understand the argument since Pound did make important changes and significant cuts to the poem, but I also think that many other writers out there owe their editors the same debt!

What this book reinforces for me, is that great works of art don’t usually just fall into your lap (or onto the page). It takes work and effort to create something good. Real writing doesn’t depend on coming up with a brilliant idea, brilliantly formulated on the first try. Real writing isn’t about getting everything right in the first draft. Real writing is sticking with your story (or your poem, or whatever else it is) through thick and thin, through rewrites and editing and despair and endless cups of tea and coffee and walks to clear your mind, through agony and joy, until you have something you are ready to release into the world.

To quote Louis Brandeis: “There is no great writing, only great rewriting.” Words to live by and remember.

The Waste Land was published in 1922. One of my favourite parts of the poem is the final, or fifth, part, “V. What the Thunder Said”. Here is an excerpt:

Ganga was sunken, and the limp leaves

Waited for rain, while the black clouds

Gathered far distant, over Himavant.

The jungle crouched, humped in silence.

Then spoke the thunder

DA

Datta: what have we given?

My friend, blood shaking my heart

The awful daring of a moment’s surrender

Which an age of prudence can never retract

By this, and this only, we have existed

Which is not to be found in our obituaries

Or in memories draped by the beneficent spider

Or under seals broken by the lean solicitor

In our empty rooms

DA

Dayadhvam: I have heard the key

Turn in the door once and turn once only

We think of the key, each in his prison

Thinking of the key, each confirms a prison

Only at nightfall, aetherial rumours

Revive for a moment a broken Coriolanus

Read more about Aragorn’s character development.

Read more about George R. R. Martin’s original outline for A Song of Ice and Fire.

April 7, 2015

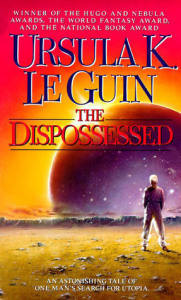

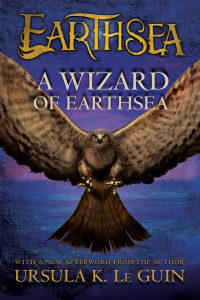

A wonderful, must-read interview with Ursula K. Le Guin

Den of Geek, a very good website for those of us who like being geeks (who doesn’t?), has a new interview with Ursula K. Le Guin that is an absolute must-read if you’re into fantasy and science fiction, if you like Le Guin as an author, and if you’re interested in the meaning of books and literature in our culture and our world.

I’ll share two quotes to give a flavour of the thing, but it’s very much worth it to read the entire piece.

First, one of her answers dealing with snobbish attitudes towards fantasy and science fiction. (She discusses this at length in the interview, including how Margaret Atwood’s publisher basically forbade her from calling her science fiction books, science fiction.)

You’ve spoken and written very cogently for decades about the snobbery that imaginative literature – science-fiction and fantasy – has from the literary establishment. Do you think we’ll ever reach a point when those snobbish attitudes don’t exist?

Some people have to be snobs, don’t they? They can’t exist without looking down on something. There will always be such people, but tomorrow the fashion could change and then we’ll be looking down on realism!

The good thing is that in my life, we really have come quite a long way to return to sanity in admitting that imaginative literature is probably the oldest kind of storytelling and will always be with us – thank goodness – and that realism is just one kind of way of writing fiction, but not necessarily the best. Certainly not automatically the best, which is what the snobbery thing was to do with. If it was realistic it was inherently better than anything imaginative and therefore the silliest realist was better than Tolkien. Well, it just, it won’t wash, as we say.

And a second quote, that really resonates with me, about the difference between the books that make an impression on you as a young person, vs. the books that make an impression on you when you’re older. I strongly agree with her here: the things that affect you when you’re a child or a teenager, shape your life and your thinking in a very different and (I believe) more profound way than the things you read later in life.

My question then is, do the books that you eat now nourish you as much as the ones you ate when you were a child and a teenager?

Oh, no no. That’s such a good question. Things that kids read and the thing that hits the kid as a kid gets into their bones. The things I read now get into my head, sure enough. I think about them. I might read something and it’ll turn into a poem next month or something, but that early stuff, that becomes a part of your whole being in a different way, and you can’t get rid of it.

Read the whole interview at Den of Geek.

April 5, 2015

“…and everyone is writing a book”

“Times are bad. Children no longer obey their parents, and everyone is writing a book.”

— Marcus Tullius Cicero

Just a reminder that if you’re wondering what the world is coming to (aren’t we all?), Cicero already complained about it over 2000 years ago.