Tom Stafford's Blog, page 17

July 8, 2015

CBT is becoming less effective, like everything else

‘Researchers have found that Cognitive Behavioural Therapy is roughly half as effective in treating depression as it used to be’ writes Oliver Burkeman in The Guardian, arguing that this is why CBT is ‘falling out of favour’. It’s worth saying that CBT seems as popular as ever, but even if it was in decline, it probably wouldn’t be due to diminishing effectiveness – because this sort of reduction in effect is common across a range of treatments.

‘Researchers have found that Cognitive Behavioural Therapy is roughly half as effective in treating depression as it used to be’ writes Oliver Burkeman in The Guardian, arguing that this is why CBT is ‘falling out of favour’. It’s worth saying that CBT seems as popular as ever, but even if it was in decline, it probably wouldn’t be due to diminishing effectiveness – because this sort of reduction in effect is common across a range of treatments.

Burkeman is commenting on a new meta-analysis that reports that more recent trials of CBT for depression find it to be less effective than older trials but this pattern is common as treatments are more thoroughly tested. This has been reported in antipsychotics, antidepressants and treatments for OCD to name but a few.

Interestingly, one commonly cited reason treatments become less effective in trials is because response to placebo is increasing, meaning many treatments seem to lose their relative potency over time.

Counter-intuitively, for something considered to be ‘an inert control condition’ the placebo response is very sensitive to the design of the trial, so even comparing placebo against several rather than one active treatment can affect placebo response.

This has led people to suggest lots of ‘placebo’ hacks. “In clinical trials,” noted one 2013 paper in Drug Discovery, “the placebo effect should be minimized to optimize drug–placebo difference”.

It’s interesting that it is still not entirely clear whether this approach is ‘revealing’ the true effects of the treatment or just another way of ‘spinning’ trials for the increasingly worried pharmaceutical and therapy industries.

The reasons for the declining treatment effects over time are also likely to include different types of patients selected into trials, more methodologically sound research practices meaning less chance of optimistic measuring and reporting, the fact that if chance gives you a falsely inflated treatment effect first time round it is more likely to be re-tested than initially less impressive first trials, and the fact that older known treatments might bring a whole load of expectations with them that brand new treatments don’t.

The bottom line is that lots of our treatments, across medicine as a whole, have quite modest effects when compared to placebo. But if placebo represents an attempt to address the problem, it provides quite a boost to the moderate effects that the treatment itself brings.

So the reports of the death of CBT have been greatly exaggerated but this is mostly due to the fact that lots of treatments start to look less impressive when they’ve been around for a while.

July 5, 2015

Computation is a lens

“Face It,” says psychologist Gary Marcus in The New York Times, “Your Brain is a Computer”. The op-ed argues for understanding the brain in terms of computation which opens up to the interesting question – what does it mean for a brain to compute?

“Face It,” says psychologist Gary Marcus in The New York Times, “Your Brain is a Computer”. The op-ed argues for understanding the brain in terms of computation which opens up to the interesting question – what does it mean for a brain to compute?

Marcus makes a clear distinction between thinking that the brain is built along the same lines as modern computer hardware, which is clearly false, while arguing that its purpose is to calculate and compute. “The sooner we can figure out what kind of computer the brain is,” he says, “the better.”

In this line of thinking, the mind is considered to be the brain’s computations at work and should be able to be described in terms of formal mathematics.

The idea that the mind and brain can be described in terms of information processing is the main contention of cognitive science but this raises a key but little asked question – is the brain a computer or is computation just a convenient way of describing its function?

Here’s an example if the distinction isn’t clear. If you throw a stone you can describe its trajectory using calculus. Here we could ask a similar question: is the stone ‘computing’ the answer to a calculus equation that describes its flight, or is calculus just a convenient way of describing its trajectory?

In one sense the stone is ‘computing’. The physical properties of the stone and its interaction with gravity produce the same outcome as the equation. But in another sense, it isn’t, because we don’t really see the stone as inherently ‘computing’ anything.

This may seem like a trivial example but there are in fact a whole series of analogue computers that use the physical properties of one system to give the answer to an entirely different problem. If analogue computers are ‘really’ computing, why not our stone?

If this is the case, what makes brains any more or less of a computer than flying rocks, chemical reactions, or the path of radio waves? Here the question just dissolves into dust. Brains may be computers but then so is everything, so asking the question doesn’t tell us anything specific about the nature of brains.

One counter-point to this is to say that brains need to algorithmically adjust to a changing environment to aid survival which is why neurons encode properties (such as patterns of light stimulation) in another form (such as neuronal firing) which perhaps makes them a computer in a way that flying stones aren’t.

But this definition would also include plants that also encode physical properties through chemical signalling to allow them to adapt to their environment.

It is worth noting that there are other philosophical objections to the idea that brains are computers, largely based on the the hard problem of consciousness (in brief – could maths ever feel?).

And then there are arguments based on the boundaries of computation. If the brain is a computer based on its physical properties and the blood is part of that system, does the blood also compute? Does the body compute? Does the ecosystem?

Psychologists drawing on the tradition of ecological psychology and JJ Gibson suggest that much of what is thought of as ‘information processing’ is actually done through the evolutionary adaptation of the body to the environment.

So are brains computers? They can be if you want them to be. The concept of computation is a tool. Probably the most useful one we have, but if you say the brain is a computer and nothing else, you may be limiting the way you can understand it.

Link to ‘Face It, Your Brain Is a Computer’ in The NYT.

July 3, 2015

Spike activity 03-07-2015

Quick links from the past week in mind and brain news:

It is Time to Temper Our Artificial Intelligence Hysteria says PSFK

Oxford academic warns humanity runs the risk of creating super intelligent computers that eventually destroy us all in The Telegraph.

Fusion reports on how artificial intelligence is evolving to recognise porn.

BBC Radio 4’s The Life Scientific featured neurosurgeon Henry Marsh.

Counterpunch has an extended, detailed piece on ‘The Rise and Fall of the Human Terrain System’ – the US Army’s group of ‘war on terror’ weaponised anthropologists.

What kind of a person volunteers for a free brain scan? asks BPS Research Digest.

Neurocritic has an interesting ethical angle on the BRAIN Initiative’s aim to develop brain implants. Do we have the funding or expertise to actually use the medical technology if it is developed?

BBC Radio 4’s The Report has a documentary on chemsex (extended shagging while high) in London’s gay scene.

Mosaic has an interesting piece on being homesick in the modern world.

Wrinkled brain mimics crumpled paper. I know the feeling. Science News with the story.

July 1, 2015

For argument’s sake

I have (self) published an ebook For argument’s sake: evidence that reason can change minds. It is the collection of two essays that were originally published on Contributoria and The Conversation. I have revised and expanded these, and added a guide to further reading on the topic. There are bespoke illustrations inspired by Goya (of owls), and I’ve added an introduction about why I think psychologists and journalists both love stories that we’re irrational creatures incapable of responding to reasoned argument. Here’s something from the book description:

Are we irrational creatures, swayed by emotion and entrenched biases? Modern psychology and neuroscience are often reported as showing that we can’t overcome our prejudices and selfish motivations. Challenging this view, cognitive scientist Tom Stafford looks at the actual evidence. Re-analysing classic experiments on persuasion, as well as summarising more recent research into how arguments change minds, he shows why persuasion by reason alone can be a powerful force.

All in, it’s close to 7000 words and available from Amazon now

June 30, 2015

Pope returns to cocaine

According to a report from BBC News the Pope ‘plans to chew coca leaves’ during his visit to Bolivia. Although portrayed as a radical encounter, this is really a return to cocaine use after a long period of abstinence in the papal office.

According to a report from BBC News the Pope ‘plans to chew coca leaves’ during his visit to Bolivia. Although portrayed as a radical encounter, this is really a return to cocaine use after a long period of abstinence in the papal office.

Although the leaves are a traditional, mild stimulant that have been used for thousands of years, they are controversial as they’re the raw material for synthesising powder cocaine.

The leaves themselves actually contain cocaine in its final form but only produce a mild stimulant effect because they have a low dose that is released relatively gently when chewed.

The lab process to produce the powder is largely concerned with concentrating and refining it which means it can be taken in a way to give the cocaine high.

The Pope is likely to be wanting to chew coca leaves to show support for the traditional uses of the plant, which, among other things, are used to help with altitude sickness but have become politicised due to the ‘war on drugs’.

Because of this, recent decades have seen pressure to outlaw or destroy coca plants, despite them being little more problematic than coffee when used in traditional ways, and consequently, a push back campaign from Latin Americans has been increasingly influential.

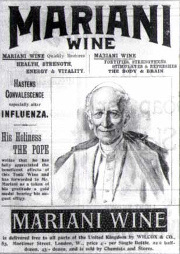

However, two previous Popes have been cocaine users. Pope Leo XIII and Pope Pius X were drinkers of Vin Mariani, which was essentially cocaine dissolved in alcohol for its, er, tonic effect.

Pope Leo XIII even went as far as appearing in an advert for Vin Mariani, which you can see in the image above.

The advert says that “His Holiness THE POPE writes that he has fully appreciated the beneficient effects of this Tonic Wine and has forwarded to Mr. Mariani as a token of his gratitude a gold medal bearing his august effigy.”

But being a Latin American, the new Pope seems to have a much more sensible view of the drug and values it in its traditional form, and so probably won’t be giving away some of the papal gold after having a blast on the liquid snow.

Link to BBC News story.

And thanks to @MikeJayNet for reminding me of the historical connection.

June 28, 2015

Never mind the neuromarketing

I’ve got an article in The Observer about the state of neuromarketing – where companies pay millions of wasted dollars to apply brain science to marketing.

I’ve got an article in The Observer about the state of neuromarketing – where companies pay millions of wasted dollars to apply brain science to marketing.

The piece looks at the three forms of neuromarketing – advertising fluff, serious research, and applied neuroscience. The first is clearly bollocks, the second a solid but currently abstract science, and the third a triumph of selling style over substance.

Finally, there is the murky but profitably grey area of applied neuromarketing, which is done by commercial companies for big-name clients. Here, the pop-culture hype that allows brain-based nonsense in consumer adverts meets the abstract and difficult-to-apply results from neuromarketing science. The result is an intoxicating but largely ineffective mix that makes sharp but non-specialist executives pay millions in the hope of maximising their return on branding and advertising.

The piece also looks at what turns out to be the most powerful innovation in marketing taken from cognitive science, but which doesn’t make the headlines like neuromarketing.

Full article at the link below.

Link to article in The Observer.

Spike activity 26-06-2015

Quick links from the past week in mind and brain news:

Picture This? Some Just Can’t. The New York Times covers a new study on people without visual imagery – that science writer Carl Zimmer helped discover.

New Republic on how the Romans understood hallucinations. “They did not have a single concept of ‘hallucination’ until very late on”.

Science of the pornocalypse. Aeon has an excellent piece that looks at the evidence for benefits and harms of pornography.

Pacific Stand has an important piece on copy number variant genetic mutations and intellectual disabilities.

Neuroscience and Politics: Do Not Hold Your Breath. Good critical piece in E-International Relations on how neuroscience is being used and abused to understand political views.

The Guardian has a reflective piece on inter-generational fathering and child psychology.

There’s a good piece over at Neurocritic about one of the many mouse studies spun by the media in folk psychology terms.

June 25, 2015

Hold infinity in the palms of your hand

A rare documentary about three people who have had hallucinatory and profound revelatory experiences is now available online.

A rare documentary about three people who have had hallucinatory and profound revelatory experiences is now available online.

Those Who Are Jesus examines the borders between revelation and psychosis and hears people recount their intense experiences while looking at how they can be understood in terms of sociology, neuropsychiatry, religion and radical mental health.

Julian believes he has been shown Jacob’s Ladder, how a universe is created and told his soul is Time itself.

Sadat says a vision of an angel said to him: “You were Jesus Christ before and you were raised to life again and you are Jesus Christ”

Rachel is a prolific artist who claims her hand is controlled by an “other energy” or “Christ consciousness” which guides her to paint universal structures.

It’s a great non-judgemental documentary that looks at what happens when intense and idiosyncratic experience intrude on everyday life.

Link to Those Who Are Jesus on Vimeo.

Link to info about the documentary.

June 23, 2015

Compulsory well-being: An interview with Will Davies

The UK government’s use of psychology has suddenly become controversial. They have promised to put psychologists into job centres “to provide integrated employment and mental health support to claimants with common mental health conditions” but with the potential threat of having assistance removed if people do not attend treatment.

The UK government’s use of psychology has suddenly become controversial. They have promised to put psychologists into job centres “to provide integrated employment and mental health support to claimants with common mental health conditions” but with the potential threat of having assistance removed if people do not attend treatment.

It has been criticised as ‘treating unemployment as a mental problem’ or an attempt to ‘psychologically reprogramme the unemployed’ and has triggered an upcoming march on a London job centre.

Will Davies is a political scientist and the author of the new book The Happiness Industry that looks at the history and practice of positive psychology as government and ‘well-being’ as a way of managing people.

We caught up with him to get some background on the recent controversy.

Is this use of psychology in social policy a quick fix or part of a broader trend?

There is a long history of using psychological techniques in order to encourage work or boost productivity. In my book, I trace this right back to the 1920s, when industrial psychologists first started to study the attitudes and emotions of people in the workplace, with a view to understanding how people could be more committed to work. Some of this was born out of a fear of socialism or trade union organising, i.e. that unhappy workers might rebel against business in some way.

But I also think something shifted fundamentally in the 1990s, as economists started to look at psychological survey data, and the field of ‘happiness economics’ took off. Economists were struggling to understand why unemployment sometimes remained high, even during times of economic growth. And one thing they began to realise was that unemployment causes types of psychological harm (namely depression) that can leave people unable to work, or unable to seek work. From an economist’s perspective, it stands to reason that the efficient course of action would therefore be to design a policy instrument that could alleviate this psychological problem. This is exactly what Richard Layard believed he had found, when he met the psychologist David Clark, who preached the virtues of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) to him.

Layard studied the evidence on CBT in the mid-2000s, and quickly put together a ‘business case’ (of the sort the Treasury needs to see, if it is to endorse any new public spending) for why it was an efficient use of public money, given its apparent success in getting people off benefits of various kinds. Of course, this strongly economistic approach to psychology also has various risks attached to it, one of which is that everything becomes viewed in a highly instrumentalised way, which is precisely what there is now a backlash against.

Layard studied the evidence on CBT in the mid-2000s, and quickly put together a ‘business case’ (of the sort the Treasury needs to see, if it is to endorse any new public spending) for why it was an efficient use of public money, given its apparent success in getting people off benefits of various kinds. Of course, this strongly economistic approach to psychology also has various risks attached to it, one of which is that everything becomes viewed in a highly instrumentalised way, which is precisely what there is now a backlash against.

A lot of the protests have centred on the idea that unemployed people might be coerced into psychological treatment with threats of having their benefits removed if they don’t attend but all over the world companies and individuals are voluntarily signing up to ‘happiness technologies’ that claim to be able to monitor and improve people’s contentment. Taking the coercive aspect away, isn’t this is a positive development in terms of also valuing people as emotional beings – rather than simply cogs in an economic system?

The problem here is that ‘happiness’ is becoming conceived in a heavily reductionist way. There tend to be two main types of reduction at play here.

Firstly, ‘happiness’ is viewed in roughly the way that neo-classical economists have viewed it, as the driver of consumer choices. Happiness economists may well be interested in broader notions of flourishing or life satisfaction than this, but the market research world has become fixated on positive emotions purely in the hope that they can be targeted by advertising or branding campaigns. Since the late 1990s, with the influence of neuroscientist Antonio Damasio, ’emotions’ have been the hottest research topic in the world of market research.

Secondly, ‘happiness’ is viewed in some biological, most often neurological, sense, as a physical occurence in the body. The claim that it’s now possible to see emotions via fMRI or physical symptoms (such as muscular reflexes or pulse rate) is no doubt grounded in credible scientific research, but before long, you reach the point where experts are speaking about emotions in ways that entirely bi-passes the voice of the person who is experiencing them. Philosophically, this is nonsense, for the simple reason that words like ‘happiness’ or ‘sadness’ can only make sense, to the extent that we can both witness them in others and describe them in ourselves. Behaviorist approaches to emotion ignore this.

Put these two agendas together, and you have an emerging industry of psychological surveillance, which purports to collect objective data about our feelings, and then commercialises it. The way in which digital health companies and technologies (such as wearables) are also offering consumer research or HR services is indicative of this new fusion between economic and physiological methods. All the while, our everyday articulations of ‘happiness’, ‘anger’, ‘joy’ or ‘despair’ are being ignored as ‘unscientific’. Businesses and policy-makers are so obsessed with tracking and measuring emotion, that they’re losing the capacity to listen to and understand it.

Of course, a lot of wellbeing data is collected in less clandestine, more analogue ways than this. Surveys are still the main basis for the field of happiness economics and ‘national wellbeing’ indicators. But this could change over time. One of the slightly perturbing trends amidst all of this is that a lot of this data collection is happening ostensibly for our own benefit, and yet it still happens without us necessarily granting permission. It’s not typically malicious or punitive surveillance (in an Orwellian sense), yet there’s still something creepy about it. Several of the companies above (including Affectiva) were founded to serve medical needs, but then subtly shifted towards more business-oriented applications, once they received venture capital. They start with the goal of increasing wellbeing… but gradually shift to the goal of maximising profit. This is a trend worth keeping an eye on.

An “emerging industry of psychological surveillance” sounds ominous. Can you give some examples?

Firstly there are those which focus on our physical bodies in various way. Companies such as Affectiva and Realeyes seek to monitor emotions through facial scanning, and offer services to market research companies amongst others. It is rare (though not unheard of) for these technologies to be used without the consent of those being monitored, and consumer groups are mobilising against intrusive uses of such technologies. Wearable technologies, such as Fitbit and Apple Watch, are marketed as devices which benefit the wearer, through greater self-knowledge.

But there are emerging cases of employers making it mandatory to wear them, or health insurers offering lower premiums to those that wear them, because of the data they can gather about behaviour, stress and wellbeing. Humanyze is a company that seeks to track employee activity (including emotions) using wearable technology, while Virgin Pulse is an HR service that includes various tools (including wearable technologies) to keep track of an employee’s state of mind and health.

Secondly, there are ways of calculating emotional variations through our use of language. The field of ‘sentiment analysis’ involves teaching computers to recognise the emotions conveyed in a sentence, and can be put to use to monitor the general happiness level of twitter users, for example, or the spread of emotions amongst facebook users. It is also integral to social media-based market research, or the ‘people analytics’ used by employers to look at employee performance via analysis of email traffic. One company, Beyond Verbal, offers indications of emotion based on tone of voice when on the phone. This has various commercial applications.

The sociologist Nikolas Rose has charted how governments increasingly see individual psychology as part of their governmental responsibility. What role do the psychologists, mental health workers and the like, have in affecting this trend?

We have to be wary of exaggerating the powers of governments and businesses in this area. A lot of my book – like the work of Nikolas Rose on this topic– implicitly looks at the goals, measurement tools and strategies that policy-makers and managers have at their disposal. However, these can seem more effective (and potentially more sinister) than how things work in practice. One thing that sociologists such as Rose have stressed is that the process of ‘translation’ between a public policy (such as tackling depression in job centres) and the actual front-line intervention is long and tortuous, and there are various individuals and institutions along the way that can divert and subvert it, for better or worse.

Professionals working in psychiatry, clinical psychology and psychotherapy retain some power to influence how things play out. Since the 1970s, more quantitative, positivist traditions have come to the fore, which grant less autonomy to professional judgement, and rely more on things like questionnaires and standardised metrics. Naturally, that means that expertise potentially becomes more amenable to governmental co-option. And yet, especially in an area like mental health, the success or failure of a policy is ultimately in the hands of someone providing the care or the listening. It’s not clear that something like IAPT can succeed, even by its own yardstick, if it becomes ever-more integrated into the pursuit of ‘efficiency’ and benefit cuts.

Speaking as an outsider, it seems to me that there is still further scope for the ‘psy’ disciplines to offer coordinated alternatives, which aren’t merely resistant, but offer new policies across society. At present, government policy is driven by an economic rationality, combined with a reductionist, behaviorist notion of mental health. This approach is guilty of both over-medicalising social problems and over-economising policy solutions. A critical bio-psycho-social alternative should have things to say, not only about mental health services or welfare, but about the damage wrought elsewhere in society.

Look at our schools, for example: there is a crisis of stress and anxiety amongst teachers while pupils are suffering the mental strains of constant examination, no doubt justified on the back of some nonsense about Britain being in a ‘global race’. If politicians are serious about the pursuit of happiness and wellbeing, and don’t want those phenomena to be simply manufactured in a mechanised fashion, then the psy disciplines and professions might want to develop some blueprints for how labour markets or companies should be governed on that basis. I remain sceptical as to whether policy-makers do conceive of psychology as anything other than an economistic route to ‘behavior change’, but lets find out.

You can follow Will Davies on Twitter as @davies_will. There are more details of his book The Happiness Industry here.

June 19, 2015

Phantasmagoric neural net visions

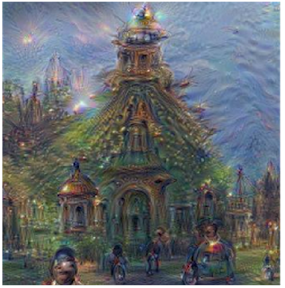

A starling galley of phantasmagoric images generated by a neural network technique has been released. The images were made by some computer scientists associated with Google who had been using neural networks to classify objects in images. They discovered that by using the neural networks “in reverse” they could elicit visualisations of the representations that the networks had developed over training.

A starling galley of phantasmagoric images generated by a neural network technique has been released. The images were made by some computer scientists associated with Google who had been using neural networks to classify objects in images. They discovered that by using the neural networks “in reverse” they could elicit visualisations of the representations that the networks had developed over training.

These pictures are freaky because they look sort of like the things the network had been trained to classify, but without the coherence of real-world scenes. In fact, the researchers impose a local coherence on the images (so that neighbouring pixels do similar work in the image) but put no restraint on what is globally represented.

The obvious parallel is to images from dreams or other altered states – situations where ‘low level’ constraints in our vision are obviously still operating, but the high-level constraints – the kind of thing that tries to impose an abstract and unitary coherence on what we see – is loosened. In these situations we get to observe something that reflects our own processes as much as what is out there in the world.

Link: The researchers talk about their ‘dreaming neural networks’

Gallery: Inceptionism: Going deeper into Neural Networks

Tom Stafford's Blog

- Tom Stafford's profile

- 13 followers