Stella Riley's Blog, page 11

March 17, 2014

THE KING’S CHAMPION

James Graham 1612 to 1650

5th Earl and 1st Marquis of Montrose

Attributed to Gerard von Honthurst

I should begin by saying that, since Montrose is one of my great heroes, I won’t be making any attempt to be unbiased here. This one is personal.

Born at Montrose and heir to one of the most ancient and noble Scottish families, James Graham might well be described as the perfect Renaissance gentleman. He was a soldier, a scholar, a poet and the epitome of Christian chivalry. He rode well and was extremely athletic; he enjoyed books and the arts and held deep religious convictions. He was also very good-looking – curling chestnut hair, clear grey eyes and a splendid figure.

When Archbishop Laud’s new prayer book was introduced in Scotland in 1637, Montrose – though a Royalist – was one of the first to sign the National Covenant. Originally, he didn’t see this as opposition to the Crown. He saw it as a matter of spiritual liberty and, initially, even fought in the Bishops’ Wars of 1639-40 until doubts set in, causing him to distance himself from the increasing despotism of the Kirk. This brought him into conflict with Archibald Campbell, Marquis of Argyll – with the result that Montrose, by now in direct contact with Charles 1, was imprisoned for five months without trial.

Montrose finally joined the King in Oxford in 1643 and, in March of the following year, rode north as His Majesty’s Lieutenant-General in Scotland. With only two companions but recruiting as he went, he winnowed his way through the Covenant-dominated lowlands to his home territory of Perthshire; and there, in July, his thousand or so Highlanders were joined by 1,600 Irishmen led by the somewhat colourful Alasdair Coll Keitach.

As Max Hastings puts it in his outstanding biography, The King’s Lieutenant-General had been granted the steel spearhead of an army. Montrose’s Year of Miracles had begun.

Inevitably, this little army was ill-armed and poorly-equipped. But in August 1644 at Tippermuir, Montrose defeated a force twice the size of his own and took Perth. A month later, it was the turn of Aberdeen – by which time Argyll was giving chase. It is worth noting here that, due to Argyll’s seizure of their lands, both the Highlanders and the Irishmen were blood enemies of the Clan Campbell.

Drawing the Covenanting army out of England was exactly what Montrose had been hoping for but his own inferior numbers made it necessary to lead Argyll a merry dance, rather than be brought to battle at a time and place not of his choosing. In October and virtually out of ammunition, he was at Fyvie Castle melting pewter chamber-pots down to make bullets. And then, as winter was setting in, he and his small army did the impossible.

They vanished into the sow and ice of the Grampians, crossing the mountains in severe weather and with little suitable clothing. Their journey covered some 200 miles and, tiring of both pursuit and the freezing conditions, Argyll retired to his castle at Inverary – a decision he was to regret when Montrose’s force arrived without warning in January of 1645 and the Irish and Highlanders book both the castle and their long-awaited revenge.

The Annus Mirabilis continued. Montrose triumphed at Inverlochy in February, Auldearn in May and Alford in July. His victory at Kilsyth in August made him master of Scotland. Glasgow opened its gates and Edinburgh freed its Royalist prisoners. It seemed the moment was now ripe for Montrose to march south and mend the King’s fortunes in England.

It was not to be. The Highlanders and Irish refused to march south with the Clan Campbell in their rear. Consequently, Montrose left Glasgow with only six hundred men to face six thousand under the command of David Leslie. The result was a foregone conclusion. Montrose was utterly defeated at Philiphaugh near Selkirk in September and the Year of Miracles was over.

Now a fugitive, Montrose fled to the continent. He was hailed as a hero in Vienna and Paris, given a Marshal’s baton by the Emperor and offered high military command by Mazarin. It is also possible that, at this time, he formed a close relationship with Rupert of the Rhine’s sister, Princess Louise, and that they planned to marry. This may be no more than a charming story – or it could be true. The portrait of Montrose [above] is ‘attribulted’ to Gerard Honthurst – but Louise was a talented artist who had studied under Honthurst. Since her family was always short of money, she needed to sell her work and some of it was signed by Honthurst because his name fetched a higher price than her own. So did Honthurst paint Montrose – or did Louise? Sadly, we’ll never know.

Time wore on but Montrose’s loyalty and hopes were still with the Royalist cause and in April 1650 he returned to Scotland with a few hundred men from Orkney and a handful of Danes. Three weeks later, his forces were annihilated at Carbisdale. Former friends who might have helped him didn’t and he was captured. Under the auspices of his old enemy, Argyll, he was executed at the Mercat Cross in Edinburgh on May 21st.

His last words from the scaffold were I leave my soul to God, my service to my prince, my goodwill to my friends, my and love and charity to you all.

His head was placed on a spike at the Tolbooth prison and his limbs severed for distribution to Glasgow, Stirling, Perth and Aberdeen.

Montrose’s Tomb in St Giles’ Cathedral

Eleven years later on May 11th, 1661 while Argyll lay in a dungeon awaiting his own fate, the people of Edinburgh lined the streets as the remains of the Lord Marquis were given a State Funeral and interred in a magnificent tomb in St Giles’ Cathedral. The King’s Champion was finally laid to rest with all the honour that was his due.

The inscription below the effigy are words of Montrose’s own, written whilst awaiting execution.

Scatter my ashes, strew them in the air;

Lord! Since thou knowest whence all these atoms are,

I’m hopeful thou’lt recover once my dust,

And confident thou’lt raise me with the just.

I’ve visited Montrose’s tomb many times over the years. It’s not just beautiful; it’s a little oasis of tranquillity where one may sit for a while and remember a remarkable man. Like other visitors, I’ve always left a small tribute – my preference being for a single red rose. But on one occasion when this wasn’t possible, I left a large purple thistle. I don’t say the one in the photograph above is mine – but it very well could be.

And a brief footnote to this tale of two Marquises …

On May 27th 1661, the Marquis of Argyll was also executed at the Mercat Cross and his head placed on the same spike previously occupied by Montrose. I call this fitting. Argyll’s tomb lies on the opposite side of the nave of St Giles’ Cathedral to that of my hero.

I have never seen it.

March 9, 2014

A bit of personal news …

The Barbican, Sandwich, Kent

This week sees my long-awaited move from Shropshire to Sandwich in Kent.

For those of you who don’t know it, Sandwich is a well-preserved medieval town and was once one of the ancient Cinque ports – though its harbour has long since silted up, leaving only the river behind.

The actual house-move means that I’ll be off-line for a few days and won’t be picking up messages. However, as soon as I’m back in business I’ll be posting the next Who’s Who … and it’s one that is particularly dear to my heart so I hope you all enjoy it.

February 21, 2014

HE GAINED THEN LOST IT ALL

MAJOR-GENERAL JOHN LAMBERT

1619 TO 1684

Lambert was born the same year as Rupert of the Rhine and, like Rupert, would have been just twenty-three years old when the Civil War began. I’ve always had a sneaking fondness for him – which anyone who has read Garland of Straw, where he features as Gabriel’s superior officer, will already know. Needless to say, he’ll be back in The King’s Falcon – this time as Eden’s commander between Scotland and Worcester.

Some of the Roundheads – such as Cromwell, for example – who were leading players in the conflict were born around the turn of the seventeenth century and didn’t achieve prominence until they were well into their forties. Others, like Ireton and Lilburne, died before reaching that age. By the time John Lambert was forty, he had achieved everything and lost it all … and he spent his remaining years in prison.

How did that come about?

Lambert was born in West Yorkshire. He began his military career as a Captain in Fairfax’s cavalry and was a Major-General by the young age of twenty-eight – a swift rise which reflects his strategic brilliance. He fought at Marston Moor in 1644, Preston in 1648, Dunbar in 1650 and played a vital role in the victory at Worcester in 1651. He was popular with his own men and the Cavaliers disliked him less than most of the other Roundhead leaders – probably because he was less Puritanical. He kept his religious views to himself, was a cynical realist and combined ambition with a gift for intrigue. He lived in style with his wife, Frances, at Wimbledon House where his hobby was cultivating tulips – on which he spent a great deal of money.

Having covered it in detail in Garland, I’ll pass over Lambert’s involvement in the complex politics of 1647-49 and simply say that he had no sympathy at all with the radicals and wasn’t one of the regicides. But in 1653, he engineered the dissolution of the Barebones’ Assembly and produced the first draft of a document which led to the establishment of the Protectorate. This is interesting because I get the impression that he didn’t particularly like Cromwell – and Cromwell clearly didn’t understand Lambert at all, describing him as ‘bottomless’. Certainly Lambert opposed the move to make Cromwell king or the Protectorate hereditary – a stand which led to his dismissal.

In May 1659, after the death of Cromwell and the overthrow of his son, Richard, Lambert regained his previous military commands when the Rump was recalled.

But this is where everything seems to have gone awry.

Following [yet another] quarrel between Parliament and the Army, Lambert repeated history by expelling the Rump. This drew General Monck down from Scotland to restore civil authority and – inexplicably, to me at least – Lambert’s troops deserted him rather than fight. The result was that he was captured and put in the Tower. He escaped, tried to rally the Army in a last ditch attempt to prevent the Restoration – and was recaptured. In 1662, he was tried, condemned to death, reprieved and sentenced to life imprisonment. He spent his remaining twenty-two years as a captive – first on Guernsey and then on Drake’s Island in Plymouth Sound.

Perhaps Lambert’s tragedy was that he reached his peak too soon and couldn’t accept that his meteoric rise might come to an abrupt end. It’s true to say that, if he had been less ambitious, he might not have begun the troubles of 1659 which resulted in the Restoration; but equally, if his principles had been of the more flexible kind, he might have gained further honours by betraying his friends and throwing in his lot with Charles the Second.

At the end, Lambert plainly did what he’d always done – he stuck to his guns. And for two decades, the intelligence and courage of a natural leader were utterly wasted.

In the words of one of the great Cavalier heroes, horribly murdered nine years before the return of the King …

He either fears his fate too much or his deserts are small,

Who puts it not unto the touch, to win or lose it all.

James Graham, Marquis of Montrose

HE GAINED THEN LOST IT ALL

MAJOR-GENERAL JOHN LAMBERT

1619 TO 1684

Lambert was born the same year as Rupert of the Rhine and, like Rupert, would have been just twenty-three years old when the Civil War began. I’ve always had a sneaking fondness for him – which anyone who has read Garland of Straw, where he features as Gabriel’s superior officer, will already know. Needless to say, he’ll be back in The King’s Falcon – this time as Eden’s commander between Scotland and Worcester.

Some of the Roundheads – such as Cromwell, for example – who were leading players in the conflict were born around the turn of the seventeenth century and didn’t achieve prominence until they were well into their forties. Others, like Ireton and Lilburne, died before reaching that age. By the time John Lambert was forty, he had achieved everything and lost it all … and he spent his remaining years in prison.

How did that come about?

Lambert was born in West Yorkshire. He began his military career as a Captain in Fairfax’s cavalry and was a Major-General by the young age of twenty-eight – a swift rise which reflects his strategic brilliance. He fought at Marston Moor in 1644, Preston in 1648, Dunbar in 1650 and played a vital role in the victory at Worcester in 1651. He was popular with his own men and the Cavaliers disliked him less than most of the other Roundhead leaders – probably because he was less Puritanical. He kept his religious views to himself, was a cynical realist and combined ambition with a gift for intrigue. He lived in style with his wife, Frances, at Wimbledon House where his hobby was cultivating tulips – on which he spent a great deal of money.

Having covered it in detail in Garland, I’ll pass over Lambert’s involvement in the complex politics of 1647-49 and simply say that he had no sympathy at all with the radicals and wasn’t one of the regicides. But in 1653, he engineered the dissolution of the Barebones’ Assembly and produced the first draft of a document which led to the establishment of the Protectorate. This is interesting because I get the impression that he didn’t particularly like Cromwell – and Cromwell clearly didn’t understand Lambert at all, describing him as ‘bottomless’. Certainly Lambert opposed the move to make Cromwell king or the Protectorate hereditary – a stand which led to his dismissal.

In May 1659, after the death of Cromwell and the overthrow of his son, Richard, Lambert regained his previous military commands when the Rump was recalled.

But this is where everything seems to have gone awry.

Following [yet another] quarrel between Parliament and the Army, Lambert repeated history by expelling the Rump. This drew General Monck down from Scotland to restore civil authority and – inexplicably, to me at least – Lambert’s troops deserted him rather than fight. The result was that he was captured and put in the Tower. He escaped, tried to rally the Army in a last ditch attempt to prevent the Restoration – and was recaptured. In 1662, he was tried, condemned to death, reprieved and sentenced to life imprisonment. He spent his remaining twenty-two years as a captive – first on Guernsey and then on Drake’s Island in Plymouth Sound.

Perhaps Lambert’s tragedy was that he reached his peak too soon and couldn’t accept that his meteoric rise might come to an abrupt end. It’s true to say that, if he had been less ambitious, he might not have begun the troubles of 1659 which resulted in the Restoration; but equally, if his principles had been of the more flexible kind, he might have gained further honours by betraying his friends and throwing in his lot with Charles the Second.

At the end, Lambert plainly did what he’d always done – he stuck to his guns. And for two decades, the intelligence and courage of a natural leader were utterly wasted.

In the words of one of the great Cavalier heroes, horribly murdered nine years before the return of the King …

He either fears his fate too much or his deserts are small,

Who puts it not unto the touch, to win or lose it all.

James Graham, Marquis of Montrose

January 30, 2014

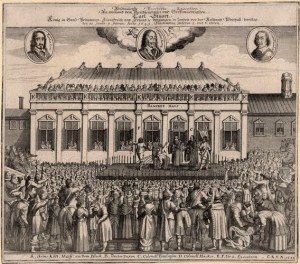

MARTYR OF THE PEOPLE OR MAN OF BLOOD?

CHARLES STUART 19th November 1600 to 30th January 1649

This is not the usual Who’s Who.

This is not the usual Who’s Who.

I have written a great deal about the reign and character of Charles 1 in The Black Madonna and Garland of Straw – and have described both his trial and execution in what some readers might consider to be exhaustive detail.

Today, on the 365th anniversary of his death, I just wanted to take a moment to think about the man who, on the morning of his execution, wore two shirts against the bitter cold of a January day so that he wouldn’t shiver and be thought afraid.  If I would have given way to an arbitrary way, for to have all laws changed according to the power of the sword, I needed not to have come here; and therefore I tell you – and I pray to God it be not laid to your charge – that I am the Martyr of the People.

If I would have given way to an arbitrary way, for to have all laws changed according to the power of the sword, I needed not to have come here; and therefore I tell you – and I pray to God it be not laid to your charge – that I am the Martyr of the People.

So, Charles called himself the Martyr of the People in his speech from the scaffold.

And Man of Blood? This tag came from Major-General Thomas Harrison. Harrison, the son of a butcher from Newcastle-under-Lyme in Staffordshire, was the first of the regicides to be hanged, drawn and quartered after the Restoration. He died at Charing Cross on October 13th 1660.

On a quite different and purely personal note …

I’d like to commend the Sealed Knot for a very enjoyable afternoon on Saturday at their annual re-enactment of the Battle of Nantwich – originally fought on Jan 25th 1644. The weather was utterly vile – driving rain, thunder and a hailstorm. But the SK didn’t allow it to dampen either their enthusiasm or good-humour even when the ground turned into a sea of freezing mud. The fact that those involved were able to leave the field smiling, says it all.

I’d like to commend the Sealed Knot for a very enjoyable afternoon on Saturday at their annual re-enactment of the Battle of Nantwich – originally fought on Jan 25th 1644. The weather was utterly vile – driving rain, thunder and a hailstorm. But the SK didn’t allow it to dampen either their enthusiasm or good-humour even when the ground turned into a sea of freezing mud. The fact that those involved were able to leave the field smiling, says it all.

January 7, 2014

One of the ‘Roaring Boys’?

Lord George Goring 1608 to 1657

When he was twenty-one years old, George Goring married the daughter of the millionaire Earl of Cork. She brought him an impressive dowry of £10,000 – which he soon squandered on cards, dice and debauchery before taking military service in Holland. By the time he was thirty, he had acquired a reputation as a gambler, a libertine and a soldier.

Bust portrait of Lord George Goring in armour, after Van Dyck

The famous siege of Breda in 1637 left Goring with a shattered ankle, a permanent limp – and presumably also permanent pain – but he didn’t let this stand in his way and, when he returned to England, he accepted the post of Governor of Portsmouth.

The Earl of Clarendon [who plainly didn't like him!] declared that, ‘he would have broken any trust or done any act of treachery to satisfy an ordinary passion or appetite.’ A severe criticism perhaps, but not unjustified. Goring’s actions between 1640 and 1642 don’t do him much credit. He managed to convince Parliament of his loyalty whilst making Portsmouth a base for the King; he was deeply involved in the Army Plots of 1641 but betrayed both of them to the Commons; and when the Civil War began, he declared openly for Charles 1 but surrendered Portsmouth within a month and decamped for Holland.

He didn’t remain abroad for long. Once back in England, he distinguished himself as a cavalry leader in the north, was taken prisoner in 1643 and released in 1644. He commanded a wing of the Royalist Horse at Marston Moor where he acquitted himself well against Fairfax only to be routed by Cromwell – and it was at this point that the rot seems to have set in. Goring had always been unreliable and was notorious for letting his men run amok. But after Marston Moor he appears to have started hitting the bottle with serious regularity whilst going out of his way to become a thorn in Prince Rupert’s side.

In the latter, he was ably assisted by Lords Wilmot and Digby – the three of them joining forces to intrigue against Rupert and to obstruct him at every turn. Inevitably, this constant ill-feeling and the resulting arguments was to eventually prove disastrous to the King’s cause.

In August 1644, Goring – now Captain of Horse in the West Country – let the Roundhead cavalry slip through his fingers at Lostwithiel but redeemed himself with a gallant showing at the battle of Newbury two months later. However, the following year saw him refusing to join Rupert before the battle of Naseby, preferring to spend his time in idle, largely drunken resentment – occasionally punctuated by bursts of action. During the next few months, he lost Taunton and caused a local rebellion by letting his men loot homes and kill livestock. By the time the Roundheads wiped him out at Langport in July 1645, he was widely regarded as ‘the evil genius of the war in the West‘.

With the King’s cause past saving, Goring went to the Netherlands and, from there, to command English regiments in Spanish service. He was to spend the rest of his days there, dying in Madrid in 1657.

So what do we make of this man who, both during his lifetime and long after it, was either loved or reviled? Egotistical, charismatic, pleasure-seeking, wasteful, intelligent, quarrelsome, brave? All of those things, probably. He had a way with the ladies and was the kind of rakehell more commonly found after the Restoration. He diced and whored and drank … but he also had a natural military talent and the ability to inspire men. He was wildly ambitious – and equally wildly irresponsible; and though he possessed the potential for brilliance, he rarely achieved it.

Nowadays, a lot of people probably consider swaggering, hard-drinking, sword-out-at-the-drop-of-a-hat George Goring to be a typical Cavalier. I don’t think this is true. He was more than those things – and many of his contemporaries were none of them. But there seems little doubt that he was one of the Roaring Boys.

November 29, 2013

THE KING’S FALCON

The following is a sample from THE KING’S FALCON

Roundheads & Cavaliers #3

by STELLA RILEY

All rights reserved. This sample may not be reproduced in any form.

In the Prologue of The King’s Falcon, we join Eden Maxwell at the battle of Dunbar in September 1650. It is not included in this sample.

ONE

On the first day of January, 1651, Francis Langley stood at the back of Scone Cathedral and watched a tall young man, five months short of his twenty-first birthday, receive – as a reward for several months of gritting his teeth – something which already rightfully belonged to him.

On the surface, the occasion looked just as it should. The young Prince, robed as befitted his station and with the royal regalia laid out before him, sat beneath a crimson velvet canopy held aloft by the eldest sons of six Earls. The vacant throne stood atop an impressive stage, some four feet off the ground and covered in rich carpets … around which the flower of Scottish nobility, splendidly attired, rubbed elbows with the cream of the Kirk. But there the illusion ended. For the crowning of a king, though a serious business, ought also to contain an element of rejoicing; and this one had so far been about as cheerful as an interment.

It wasn’t a surprise. After forcing Charles to take both Covenants, making him publicly repent the sins of his parents as well as his own and ordaining two fast days, the Scots were scarcely likely to allow the coronation itself to be marred by any hint of pleasure. The handful of English Royalists had been relegated to the edges; the Engagers, those gentlemen who’d fought for the late King at Preston, had been prohibited altogether; and the only persons permitted to have a hand in the ceremony itself were those whose Covenanting principles met the exacting standards of Archibald Campbell, Marquis of Argyll. Francis, of course, wasn’t supposed to be there at all – which is why he was lurking as unobtrusively as possible in a dimly-lit corner.

The Moderator of the General Assembly delivered an epic sermon, liberally laced with gloom. Major Langley shifted his shoulders against the cold stone, smothered a yawn and let dire warnings about tottering crowns and sinful kings flow over him. One became immune, after a time, to austere Scottish strictures. And a formal crowning would do much to dilute such humiliations.

Charles knelt to affirm his oath to the Covenants. His voice was devout enough and his promise to establish Presbyterianism in his other dominions was made without a hint of either reluctance or cynicism. Francis smiled, silently applauding … and immediately found himself encompassed by the obliquely considering stare of the fellow who’d ridden in on the previous evening with a bundle of heavily-sealed letters. Francis responded with one sardonically raised brow before restoring his attention to the ceremony. Not everyone, he reflected, thought this particular game worth the candle.

Charles ascended to the waiting throne. Lord Lyon, the King of Arms, announced that he was the rightful and undoubted heir of the Crown and those present responded with a resounding cry of God save the King, Charles the Second! – upon which His Majesty was escorted back to the chair he’d occupied during the interminable sermon for the reading of the Coronation Oath. Francis watched Charles kneel to affirm this before being invested with kingly robes and the articles of state; he set his jaw and suppressed a desire to fidget when the minister prayed that the Lord would purge the Crown from the sins and transgressions of them that did reign before; and he let out a breath he hadn’t known he’d been holding when the Marquis of Argyll finally placed the crown on Charles’s head.

The tradition of anointing the sovereign had been dispensed with as superstitious ritual but, at long last, Charles was declared King of Great Britain, France and Ireland; and, amidst more pious exhortations from the Moderator, he was led to the throne so that the nobles could touch the crown and swear fidelity.

‘Argyll the kingmaker,’ murmured the courier. ‘And even more Friday-faced than usual. The débâcle at Dunbar, do you think? Or perhaps it’s merely that squint of his.’

Francis turned his head and encountered a gleaming stare.

‘Both, I imagine.’

‘But one more than the other,’ came the bland reply. ‘Contrary to present appearances, his power isn’t quite what it was. One even hears rumours of the return of Hamilton.’

Wondering where someone who’d only just arrived might have picked up that particular rumour, Francis said gently, ‘Does one? I wouldn’t know. But it would certainly account for Argyll’s expression … even allowing for the squint.’

The other man said nothing. The Scots finished swearing fealty and King Charles the Second rose to solemnly beseech the ministers that if at any time they saw him breaking his covenant, they would instantly tell him of it. Then, with becoming dignity and a flourish of trumpets, the royal procession passed back down the aisle … and, in due course, Francis found himself outside with the rest.

His companion from the cathedral was nowhere to be seen and, instead, his arm was taken by the Duke of Buckingham, who drawled, ‘The throne’s gain is clearly the theatre’s loss. Such clarity of diction despite having his tongue firmly in his cheek! I’m impressed.’

‘And indiscreet,’ sighed Francis. ‘Shall we go? It’s extremely cold and the banquet awaits.’

‘It’s bound to be dreary. There will be speeches, God help us all … and insufficient wine to drown them out. But I’m amazed the coronation committee thought fit to invite you – if, indeed, they did? Come to think of it, I’m not entirely sure why they asked me.’

It wasn’t true, of course. Twenty-two years old, blessed with startling good looks and frequently too clever for his own good, George Villiers, second Duke of Buckingham, was not used to being ignored.

Smiling faintly, Francis said, ‘For your entertainment value, George. Why else?’

‘Do you think so? I thought it had rather more to do with my having been more or less reared alongside the Lord’s unanointed. But I daresay you know best … so I’ll try to live up to everyone’s expectations.’

Inside the banqueting chamber, wax candles burned bright and log fires blazed in the great hearths. Long tables gleamed with silver plate, fine glassware and monogrammed damask and, winnowing between these and the arriving guests, liveried servants handed out cups of spiced wine. No expense, it appeared, had been spared. It was just a pity, thought Francis, that the company wasn’t better.

Undeterred by the fact that His Majesty was still hemmed in by Argyll and a clutch of black-clad ministers, Buckingham sauntered towards him. Francis made polite conversation with various acquaintances and then took his place, as directed, at one of the lower tables with the rest of his unwelcome compatriots.

‘Well, well,’ said a familiar voice cheerfully. ‘You again. We are obviously perceived to be of the same lowly status. Or do I mean tarred with the same brush?’

Francis turned slowly and took his time about replying.

Of roughly his own age and height, the courier was as fair as he himself was dark and dressed in well-worn buff leather. Knowing how few Royalists had any money these days and aware that his own blue satin was decidedly shabby, Francis passed over this sartorial breach and concentrated on the intelligence evident in the fine-boned face and the gleam of humour in the dark green eyes.

Holding out his hand, he said lightly, ‘Francis Langley – unemployed Major of Horse.’

His fingers were taken in a cool, firm grip.

‘Ashley Peverell – jack-of-all-trades,’ came the reply. And, dropping into the adjacent seat, ‘Don’t tell me. You were purged from the army before Dunbar?’

‘Well before it. And you?’

‘Oh – I was already persona non grata.’ Bitterness mingled oddly with nonchalance. ‘I fought at Preston – for all the good that did.’

An Engager, then, thought Francis. If Argyll knew that, the door would have been slammed in your face. But it explains how you know about Hamilton. He said merely, ‘Quite. I was at Colchester.’

‘Ah. Then you doubtless have better cause for resentment than I. However. At least you haven’t become a glorified errand boy.’

The conversation had arrived, quicker than Francis expected, at the point which interested him. He said, ‘The letters you took to the King last night?’

‘The very same. Speculation rife, is it?’

‘Naturally. Anything to break the monotony.’

Ashley Peverell grinned.

‘A cry from the heart, if ever I heard one. But I’m afraid I’m going to disappoint you. I’ve merely been doing the rounds in England. You know the sort of thing. Can you offer a few guineas to help feed and clothe your King? Alas, sir, I can barely feed and clothe my family. Can His Majesty rely on your support in the event of another invasion? He has my very good wishes, sir. More than that, I cannot guarantee. And so on and so on and depressingly, unsurprisingly so on.’

Francis frowned. ‘Is it really as bad as that?’

‘Yes. Oh – people are sick of the so-called Commonwealth. They’re tired of the Rump clinging to power while it ordains fines for swearing and penalties for adultery – and they resent the monthly assessments and the Excise. But not everyone will ally themselves with the Scots and many wish His Majesty hadn’t taken the Covenant. Then again, out of the total support I have been promised, experience has taught me not to expect to see more than half of it when the time comes.’

‘You’re turning into a cynic, Ash,’ remarked a voice from the far side of the table. ‘It won’t do, you know.’

Two pairs of eyes, one green and one deep blue, turned towards the speaker – a thin-faced young man with a shock of unruly brown hair.

‘My God,’ groaned Ashley. ‘Somebody should have warned me.’ Then, laughing and stretching out a hand, ‘How are you Nick? Still looking for dragons to slay?’

‘You could put it that way,’ returned Sir Nicholas Austin, accepting the hand with unabashed good-humour, ‘though I personally wouldn’t. And I suppose you’re going to tell me that there are plenty of them here.’

‘Look around and judge for yourself.’

Nicholas cocked an eyebrow at Francis.

‘Major Langley – I’m shocked. I thought you only had truck with respectable people.’

‘One tries,’ murmured Francis. ‘As it happens, Mr Peverell and I have only just met.’

Nicholas blinked and opened his mouth to speak. Forestalling him, Ashley said, ‘Hallelujah. The food is coming. Along, I hope, with another jug of claret.’

Taking the hint, Nicholas said, ‘Hold on to that hope but don’t rely on it. They’ll be making sure no one gets drunk. After all, it would be a pity if we started to enjoy ourselves, wouldn’t it?’

The food was good and plentiful. Capons jostled numerous varieties of fish, venison sat cheek-by-howl with partridge and woodcock, and delicately flavoured creams and custards nestled between pastries filled with beef and apricots. The wine, on the other hand, continued to arrive slowly and in niggardly quantities. Even the King, still politely listening to Argyll, was frequently seen to be nursing an empty glass.

Ashley diverted a flagon from a table to his right and Francis liberated another from the one behind him. Vociferous complaints arose. Laughing, Nicholas passed both jugs back – empty. From his place beside Charles, his Grace of Buckingham watched enviously.

‘It seems to me,’ remarked Ashley Peverell at length, ‘that our sovereign lord deserves a small celebration more in keeping with his tastes.’

‘I daresay,’ agreed Francis. ‘But exquisite ladies of easy virtue don’t exactly abound in Perth. And his reputation is widespread enough already.’

‘His bastard by Lucy Walter? Quite. But he must be able to enjoy himself outside the bedchamber. Amidst friends, for example … over a few bottles, in the private room of a tavern. It shouldn’t be too difficult to arrange.’

Francis looked at him.

‘Is that a suggestion?’

‘Call it more of a challenge.’

Major Langley lifted one dark brow.

‘A challenge? How medieval. But I think … I really think I must accept.’

* * *

In the end, the party in the upper room of the Fish Inn to which Charles was discreetly conducted later that evening, was augmented by two persons. Buckingham – because, as the King’s closest friend, he couldn’t be left out; and Alexander Fraizer, because his ability to mingle medicine with intrigue meant that he’d find out anyway. Also, as Ashley pointed out, after the amount they’d all eaten and the amount they intended to drink, a doctor might come in handy.

To preserve His Majesty’s incognito, bottles were fetched and carried by Ashley’s servant, Jem – a burly individual whose fund of thieves’ cant made Francis wonder where Mr Peverell had found him and soon had the King memorising phrases.

By the time toasts had been drunk and the coronation thoroughly dissected and joked about, everyone was pleasantly mellow. Then Charles said, ‘Try not to laugh your boots off, gentlemen – but Argyll thinks I should marry.’

‘Does he?’ Buckingham reached for the bottle. ‘How quaint of him. And whom does he suggest as a potential bride?’

‘A paragon of birth, beauty and virtue. In short, the Lady Anne Campbell.’

The room fell abruptly silent.

‘His daughter?’ asked Nicholas feebly. ‘He wants you to marry his daughter?’

Charles nodded, his dark eyes impassive.

There was another silence. Then Ashley said, ‘They must be allowing the Engagers back.’

Buckingham’s brows rose.

‘I thought we were discussing His Majesty’s proposed marriage?’

‘We are. Argyll’s position has been slipping since Dunbar. The return of Hamilton and the Engagers will destroy it completely. But with the English holding Edinburgh and everything to the south of it, the Scots army needs all the help it can get – so the repeal of the Act of Classes is only a matter of time. Consequently, Argyll is trying to join his star to the King’s before it vanishes completely. Simple.’

Francis eyed him thoughtfully. Whoever – or whatever – Ashley Peverell was, there was plainly nothing wrong with his intellect. The King obviously knew this already for he said, ‘So tell me, Ash. How badly do I need him?’

‘A lot less than you did yesterday,’ came the frank reply. ‘If I’m right about the Engagers, the only influence Argyll will soon have left to him is over the Kirk – and since you can’t afford trouble from that direction, you’ll have to go on being nice to him for a while longer.’ Ashley grinned. ‘But a marriage negotiation is a weighty matter which can take months, Sir. And you can’t even contemplate it without Her Majesty, your mother’s consent.’

‘Which, of course, she won’t give,’ murmured Charles with an answering gleam.

‘No. But you don’t need to tell Argyll that.’

‘I wouldn’t think,’ remarked Buckingham, ‘that he’ll need telling. However … since you seem to have it all worked out, perhaps you’d like to evaluate His Majesty’s chances of regaining his throne in the not-too-distant future.’

Alexander Fraizer said flatly, ‘That’s no a fair question, your Grace – and one nobody here could fairly answer.’

‘Not you or I, certainly, Sandy. But I’m sure Colonel Peverell is much better informed than we are.’

Colonel Peverell? Francis looked across at Nicholas and received a rueful shrug.

‘Or perhaps,’ added the Duke, slanting a slyly malicious smile in the Colonel’s direction, ‘you prefer to be called The Falcon?’

Francis narrowly suppressed a groan.

The Falcon? Really? Christ. Who was this fellow?

‘I doubt it,’ said Ashley prosaically. ‘As to your question … we all know the general situation. Ireland has been left groaning under Henry Ireton’s boot; France is offering us nothing because Mazarin has his own problems; and the death of William of Orange means we can expect little of the Dutch. As for England – sporadic risings like the one in Norfolk before Christmas are crushed within hours. So for the time being, our only real hope lies in a strong, fully-united Scots Army.’

‘Woven about yourself and the Engagers, no doubt,’ said Buckingham sweetly. ‘So you’ll gladly do penance in sackcloth and ashes like poor Middleton?’

Colonel Peverell fixed him with a cool, faintly impatient stare.

‘Why not? If His Majesty can swallow his pride, I’m not about to stand on mine. Francis – pass the bottle, will you? This is supposed to be a celebration. Doesn’t anyone know any funny stories?’

Buckingham did and immediately embarked on an anecdote about a pair of startled lovers and a misdirected golf ball. Francis leaned towards Ashley and said softly, ‘George doesn’t like you, does he? Any particular reason?’

‘You’d better ask him.’

‘On the contrary. I think I’d better not.’ Amusement stirred behind the sapphire eyes and then was gone. ‘Why didn’t you say you were a colonel?’

‘I didn’t want to put you to the trouble of saluting. Does it matter?’

‘It shouldn’t. But I can’t help wondering why you didn’t want Nick to reveal it.’

‘No reason that will make you feel any better. Get ready to laugh. Buckingham’s building up to his grand finale.’

Curiosity had always been Francis’s besetting sin and he had no qualms about indulging it. Fortunately, one golfing tale had a way of leading to another – so it wasn’t difficult to get the King and Sandy Fraizer started on the last game they had played together. Smiling, Francis turned back to the Colonel.

‘I’ve heard this one. It takes about ten minutes. So … where were we?’

‘Nowhere that I can recall. Don’t you like golf?’

‘Not as a topic of conversation. It ranks alongside Generals I have known and How I lost my leg at Naseby.’

Ashley laughed. ‘My God. How do you pass the time?’

‘I read. Poetry, mostly. And I write a little.’ Francis re-filled both their glasses and sat back. ‘In truth, though I trained at Angers, I expected to spend my life at Court. It was the war that made me a soldier – and not, I’m afraid, a particularly good one. By the time we got to Marston Moor, Rupert had cured my worst faults and I learned a whole lot more at Colchester. But I’m no military genius … and I still prefer books to battles.’ He smiled again. ‘That’s my guilty secret. What’s yours?’

Ashley drew a short breath and then loosed it.

‘You don’t give up, do you?’

‘Rarely. But at least I’m asking you, not Nick.’

‘It wouldn’t do you an enormous amount of good if you did. But there’s no need to show me the stick,’ came the dust-dry response. Then, with a slight shrug, ‘You wish to know if my military rank is a courtesy. It isn’t.’

‘And The Falcon?’

‘Does things a Colonel can’t – and isn’t a sobriquet I either sought or want.’

‘I … see.’

‘I doubt it.’ Ashley grinned suddenly. ‘But if you can’t live without at least one incident from my murky past … between Preston and joining Charles in late ’48, I took to the High Toby.’

Francis blinked. ‘I beg your pardon?’

‘I was a highwayman. Jem says I was a bloody bad one – but that’s due to a difference of opinion coupled with the fact that it was his profession long before it was mine. You must have guessed that. His vocabulary is extremely … colourful.’

‘Incomprehensible, more like.’

‘Not to me, fortunately.’ Ashley stood up and stretched, then turned back to murmur wickedly, ‘You’re right about Buckingham, by the way. Asking him about me wouldn’t be very tactful.’

‘So I had assumed. Is there a good reason?’

‘He certainly thinks so. Her name was Veronique.’

Charles and the doctor reached the end of their golfing reminiscences and the talk became general once more. By the time Jem Barker appeared with fresh supplies, the party was growing very merry and Buckingham was decidedly the worse for wear.

Dumping his cargo on the table, Mr Barker said, ‘Here’s some more boozing-cheats for you – though I reckon you’ve all got bread-and-cheese in your heads already, going by the din.’ He bent a severe gaze upon the Duke and then, turning to Ashley, said, ‘Better watch that’n. Looks about ready to flay the fox, to me.’

The door banged shut behind him and, amidst the laughter, Charles said unsteadily, ‘F-flay the fox?’

‘Throw up,’ translated Colonel Peverell obligingly.

‘In my presence?’ demanded the King. ‘He’d better not. It isn’t respectful.’ He paused, looking at Ashley. ‘You’re not drunk, are you? Why not?’

‘Because someone has to see you safe home again, Sir.’

‘I don’t want to be seen home. I don’t want to be discreet. And I’m sick of not being able to stir without a pack of preachers at my heels.’ The dark, Stuart eyes gathered an obstinate glow. ‘It’s got to change, Ash.’

‘It has changed, Your Majesty. You’ve been crowned.’

‘Not in England. Nor, without a united army, will I ever be – and amidst all the damned squabbling, I can’t see how I’m to get one.’

‘A royal progress,’ said Francis languidly. And then, when Charles peered owlishly at him, ‘Travel about those areas not occupied by Cromwell. Draw the people to you – and make sure that the Kirk is aware of it.’

There was a short silence. Then Nicholas said hazily, ‘Rose-petals and banners, cheering crowds and hosts of pretty girls … fountains flowing with wine –’

‘In Scotland?’ murmured Ashley.

‘True,’ said the King. ‘But it’s a good idea for all that. Popularity is important.’ He paused, his face creasing in a tipsy, sardonic smile. ‘Not that I’m ever going to be popular with the Kirk unless I repent being born.’

‘Long-nosed canting miseries,’ grumbled Sandy Fraizer into his glass. ‘They fair give me the marthambles.’

‘Me too.’ Lurching to his feet, Buckingham grabbed a bottle and collapsed back into his seat with it. ‘Whole bloody country givesh me the marthambles.’

‘And Cromwell,’ pronounced Nicholas. ‘Let’s not forget Old Noll. Lucky Noll, warty Noll, Noll the nose.’ And sang, ‘Nose, nose, nose, nose – who gave thee that jolly red nose?’

And with enthusiastic if imperfect unison, his companions responded, ‘Cinnamon and ginger, nutmeg and cloves – that’s what gave thee that jolly red nose!’

One song led to another. Sir Nicholas climbed uncertainly on his chair and conducted the ensemble with a poker. Dr Fraizer beat time on the log-box, the King used a pair of pewter plates as cymbals and his Grace of Buckingham, slightly green about the gills, participated with a series of violent hiccups.

Then the door burst open and Jem Barker flew backwards into the room on the end of someone’s fist.

Nicholas fell off his perch.

In the doorway, three men-at-arms made way for the stern-faced Moderator of the General Assembly and a pair of horrified ministers.

‘Shit,’ burped Buckingham. And threw up in the hearth.

Silence engulfed the room and Ashley stared rather desperately at Francis.

‘Oh dear,’ he said mildly. ‘Sackcloth and ashes all round, I think.’

And gave way to helpless laughter.

TWO

Although it necessitated a good deal of grovelling, the affair at the Fish Inn did not become common knowledge and Charles, having written to ascertain his mother’s views on a possible union with the Lady Anne Campbell, wisely set off on an immediate tour of north-eastern Scotland. Unsurprisingly, Major Francis Langley and Sir Nicholas Austin were not amongst those permitted to accompany him – which meant that they had the pleasure of watching the second Duke of Hamilton’s return to Court occasion Argyll’s sulky withdrawal from it. And around the end of the month, Colonel Peverell disappeared again on undisclosed business.

He went to Ireland first to see if things were really as bad as people said. They were. Thousands starved on a land devastated by war; and while Irish Royalists and Irish patriots continued to exist in mutual distrust, Commissary-General Ireton extended his grip on everything outside the mountains and the bogs.

Disguised as a peat-cutter in clothes that itched, Ashley evaluated what he saw. And when both stealth and his assumed persona failed him, he dispatched the problem in the usual unpleasant but extremely final way and put it from his mind. It wasn’t the first time and it probably wouldn’t be the last but it was sometimes necessary. He just preferred not to keep count.

He spent five days trying to talk sense in to a clutch of O’Neils; and then, aware that he was wasting his time and wanting a bath more than he’d ever wanted anything in his life, he took ship for The Hague.

The crossing in a filthy, leaking tub was a bad one and the news at the other end no better. Ashley had known that William of Orange’s stubborn solitary opposition to the Commonwealth had died with him. What he hadn’t known was that the Prince’s death had also allowed Holland to take the lead amongst the United Provinces, with the result that negotiations were even now taking place with Westminster. In vain did the exiled Royalists try to cheer him with descriptions of how difficult they were making life for the Parliamentarian envoys. Ashley merely shrugged and remarked that making Oliver St. John go about armed to the teeth with a couple of body-guards in attendance wasn’t going to solve anything. Then, leaving his compatriots muttering darkly to themselves, he left on the next leg of his Odyssey.

Arriving in Paris amidst the rain and wind of early March, he gave Sir Edward Hyde an unvarnished account of how matters stood in Scotland and received, in return, a gloomy picture of the latest obstacles being set in the way of his fellow agents in England, coupled with an alarmingly long list of recent arrests. Amongst these was a name worrying enough to set Ashley scouring Paris for the best-informed and most elusive spy he knew … which was how, two painstaking days later, he ended up in the crowded pit of the Theatre du Marais.

By the time he arrived, the play was already well under way. A florid, middle-aged actor was engaged in verbose seduction of a well-endowed actress some four inches taller than himself and demonstrably past her first blush. The female half of the audience appeared enthralled; the gallants in the pit brimmed with boisterous advice – of which Get a box to stand on! seemed generally the most popular. Colonel Peverell sighed, shoved his playbill unread into his pocket and started looking about for One-Eyed Will.

The theatre, which had originally been a tennis-court, was smarter than he’d expected owing to a fortuitous fire which had caused it to be largely rebuilt some six or seven years ago. Lit by a huge chandelier, the proscenium stage was wide and deep with a good-sized apron surrounded by foot-light candles. The old spectators’ galleries had been replaced by comfortable boxes – though, from most of them, it was only possible to watch the play by leaning over the parapet. Jostled on all sides, Ashley stood in the pit, systematically scanning faces until, in one of the front off-stage boxes, he recognised the distinctive black silk eye-patch and wild mop of dark hair belonging to Sir William Brierley.

Since he was in the company of two other gentlemen and a lady, Ashley hesitated briefly and then, shrugging slightly, started elbowing his way in their direction.

With the mischievous restlessness around him fast approaching its zenith, this was not easy. On stage, the statuesque heroine swooned into the arms of her would-be seducer, knocking his wig askew. Undeterred and clasping her to his manly chest, the hero delivered another epic speech and attempted to haul her to a couch. Predictably, the wits advised him to make two trips. Casting his well-wishers a venomous glance, the actor concluded his speech and exited stage-left with a swish of his cloak, to an accompanying chorus of stamping and whistles.

Purposefully but without haste, Ashley pursued his winnowing course, vaguely aware that, on the stage, a girl costumed as a maid-servant had skimmed out from the wings to fan the recumbent leading-lady with her apron. The pit, now well into its collective stride, suggested various other ways of reviving Madame d’Amboise.

‘Get her corset off!’ shouted one.

‘Fetch a bucket of water!’ yelled another.

‘Fetch the Vicomte de Charenton!’ howled a third.

The pit roared its approval and, this time, even the boxes shook with laughter. Stuck between a fat fellow reeking of garlic and a world-weary slattern peddling oranges, Ashley reflected that he’d known quieter battle-fields and wondered how the actors endured it. Just now, for example, the girl playing the maid was still kneeling beside the leading lady. Neither showed any sign of trying to carry on with the play which, until the noise died down, was probably wise. Then, just as Ashley sucked in his breath prior to fighting his way closer to One-Eyed Will, the girl rose swiftly to her feet and stepped downstage into the blaze of candles surrounding the apron.

The effect on the audience was cataclysmic. The stamping stopped; the catcalls withered into uncertainty; and the laughter turned into a medley of appreciative whistles before fading into something very close to silence. Ashley took a good, long look … and understood why.

Seen properly for the first time in the full glare of the lights, the girl was mind-blowingly beautiful. A dainty, lissom creature with a hand-span waist, a torrent of glowing, copper curls and an exquisite heart-shaped face set with huge dark eyes; a fantasy made flesh … and guaranteed to stop any man’s breath for a moment. The only thing wrong, decided Ashley clinically, was that she clearly knew it and was enjoying the effect.

As swiftly as the thought had come, he realised it was wrong. Although he couldn’t read her eyes from where he stood, he could see indecision in the line of her shoulders and the way her hands were gripping her apron. A smile curled his mouth. At a guess, she had a few lines – probably pitifully few – and, since she didn’t want to waste them on an audience that wouldn’t shut up, she’d stormed downstage. Only now the audience had shut up, she’d realised that she was out of position. Ashley’s smile grew as he waited to see what she’d do about it.

What she did was to draw a very deep breath. The effect this had on her body had Ashley and most of the men around him drawing one with her. The audience was absolutely silent now, waiting for her to speak. She lifted her chin, smiling a little. Then, seizing a candle from the nearest sconce, she embarked smoothly on her opening speech and swirled back to the couch to twitch an ostrich feather from Marie d’Amboise’s head-dress, singe it and wave it under that lady’s nose.

Madame d’Amboise coughed and regained consciousness with remarkable, if unconvincing rapidity. Ashley was startled into a choke of amusement, the gallants in the pit hooted with laughter and the acrid smell of burned feathers drifted into the front boxes. Avoiding the leading lady’s furious glare, the girl played the rest of her brief scene without apparent deviation and exited to an unexpected storm of applause.

Ashley Peverell watched her go and wondered if, under the paint, she looked as good close to as she did from a distance. Then, reminding himself that he hadn’t come here to watch the play, he turned his attention back to the business in hand.

By dint of a good deal of unmannerly shoving, he eventually reached his goal and immediately found himself impaled on Sir William’s one and only eye.

‘Well, I’m damned,’ drawled that gentleman lazily. ‘A face I never thought to see again … back from the dead and come to haunt me. How are you, Colonel?’

‘Bruised,’ replied Ashley. And with an audacious smile at the pretty brunette, ‘I don’t suppose you’d care to invite me into your private haven?’

She smiled coquettishly.

‘By all means, sir. Come and be welcome.’

Needing no further telling, Ashley hoisted himself over the parapet and bowed over the lady’s hand. ‘Madame, you are a pearl among women and may count me your most willing slave.’

She gave a trill of laughter.

‘William – your friend is charming. Aren’t you going to introduce him?’

‘He’s a rogue and a mountebank,’ remarked Sir William calmly. Then, with a wave of his handkerchief, ‘However, mes amis … allow me to present Colonel Peverell, formerly of His Majesty’s Horse and latterly of God alone knows where. Ashley … meet Mistress … er …’

‘Verney,’ supplied the brunette firmly and with something resembling defiance. ‘Celia Verney.’

‘Of course,’ murmured Will, watching Ashley kiss the lady’s hand. ‘Also Sir Hugo Verney … and Jean-Claude Minervois, Vicomte de Charenton.’

Mechanically going through the obligatory courtesies, Ashley was aware of several things. Sir Hugo looked uncomfortable; the Vicomte was not in the best of tempers; and Will’s eye was brimming with wicked amusement.

Oh God, thought Ashley. It’s a ménage a quatre. Cinque, if you count that busty piece on the stage. How long before I can get Will away?

As it happened, he didn’t have to wait very long at all. The third act drew to a close amid increasingly ribald comments from the pit and, after some desultory discussion on the merits of the play and whether or not Arnaud Clermont was past his professional best, Sir William said suavely, ‘Celia, my angel – you’ll forgive me if Ashley and I desert you? So much gossip to catch up on and, one suspects, so little time in which to do it, you know?’ Then, barely giving her time to nod, ‘Hugo, my dear … such a pleasure to see you. You must both dine with me one day soon. And Jean-Claude … what can one say? One had no notion that your liaison with the delectable d’Amboise was so widely known. But naturally one sees that the cachet it gives the lady is bound to place a strain upon her discretion. So difficult for you, mon brave. One cannot but sympathise.’

Still smiling and with the merest hint of a pause, Sir William turned to Ashley.

‘Come, my loved one. The play is about to resume and we must not interrupt it. Farewell, one and all. Bon nuit!’ Upon which, he swept Ashley away.

‘And that, as they say, was definitely better than the play,’ he remarked, linking arms with Ashley. ‘It’s not Marie d’Amboise’s fault that the whole of Paris knows Charenton’s bedding her. It’s milord himself who does the boasting. And then he gets disgruntled when the wags make a game of him. The man, my dear,’ finished Will blandly, ‘is an absolute prick.’

Laughing, Ashley said, ‘And you’re a damned shit-stirrer. I’m surprised he didn’t hit you.’

‘No, no. He’d be afraid I might hit him back.’

‘Which, of course, you would.’ Ashley was perfectly well-aware that Sir William’s effete manner was only skin deep and that below it lay a dangerous and, when necessary, ruthless man. ‘And what of the Verneys? Something not quite right there either, I fancy.’

‘You were awake, weren’t you?’ came the admiring reply. ‘Can’t you guess? The fair Celia is Verney’s mistress – but not, alas, Mistress Verney.’

‘Ah.’

‘Quite. One understands that Hugo has a wife in England, clinging tenaciously to the family estates and rearing a son … and similarly, Celia is still married to one of Cromwell’s up-and-coming young officers. So what we have here is caps over the windmill and the world well lost for love. All very well in its way … but one wonders whether having the right body in bed is sufficient compensation for social leprosy.’ Will’s mouth curled wryly. ‘One may be a threadbare exile – but one has one’s standards.’

‘A lady conducts her affaires with discretion and a gentleman doesn’t inflict his whore on polite company?’ recited Ashley. And then, ‘How nice that some people still have nothing better to think about.’

‘It would be if it were true.’

‘And isn’t it?’

‘Oh no,’ came the gentle reply. ‘Most of our compatriots here have lost everything except their pride – and that, they preserve at all costs. One can’t really blame them. After all, you and I do it too. The only difference is that we’ve grown so used to banging our heads against the wall, we don’t know how to stop.’ He paused and gestured to a shallow flight of steps. ‘My humble abode – within which lie a couple of bottles of reasonably palatable burgundy. Shall we?’

‘By all means. Fascinating as all this is, I didn’t scour Paris in search of you just to find out who is sleeping with whom.’

‘I never thought you did. But don’t dismiss it too readily. Bedroom secrets are often terribly useful.’

Sir William’s lodgings comprised two neat, spacious rooms on the first floor. While his host busied himself with the wine, Ashley dropped into a carved chair by the hearth and attempted to poke some like into the almost dormant fire. Then, when Will handed him a glass and sat down opposite him, he said bluntly, ‘You’ll have guessed, I daresay, that I’ve come from Scotland. To cut a long story short, I’m gathering information in an attempt to assess the chances of a second invasion succeeding where the first one failed.’

Sir William’s brows rose.

‘Excuse my asking … but do you really think there’s the remotest chance of the Scots ever fielding a viable army?’

‘Meaning you don’t?’

‘No, my loved one. I don’t. However. Let us put that aside for the moment. What do you want to know?’

‘Hyde says Tom Coke’s been arrested. I need to know how much he knows – and whether he’s likely to make Cromwell’s spy-master a present of it.’

‘Oh dear.’ William sat back in his chair and contemplated his wine-glass. The fire was burning brighter now and its glow was dully reflected in the silk eye-patch, giving its wearer an appearance of demonic menace. Finally, in a tone of acid finality, he said, ‘Thomas Coke will have spilled his guts on the first time of asking and, in all probability, has gone on babbling ever since. As for what he can reveal … I have to say that, in common with the rest of our agents, it’s too damned much. That has always been our problem. If no one knew more than they needed to, we’d be a great deal more efficient than we are.’ He paused briefly and looked across at Ashley. ‘The unfortunate truth is that you are careful and I am careful. But the rest of the buggers treat espionage like a game of Blind Man’s Buff.’

‘I know.’ Ashley sighed. ‘I’ve worked with a few of them, God help me. But what about Coke? Do you have any idea what he may have been involved with? Or who?’

‘Oh yes,’ returned Sir William, wryly. And told him.

At the end of it, Ashley stared into the fire without speaking. Then he said, ‘Oh bloody hell. And there’s not a damned thing we can do about it, is there?’

‘There’s nothing anyone can do about it.’ There was another long pause. Then, ‘This invasion fantasy of yours. Tell me about it.’

‘It’s less of a fantasy than you might think. The Scots want Cromwell out of their country so much they’ve crowned Charles and are letting the Engagers back. They have an army of sorts. Oh – it’s neither huge nor well-equipped and it’s far from well-trained … but, to a degree at least, all those faults might be mended.’

‘I do so admire optimism. But please go on. Who is commanding?’

‘Well, David Leslie, of course. And –’

‘Ah yes. Canny, cautious old Leslie. The general who, despite knowing the ground like the back of his hand, managed to get wiped out at Dunbar. Next?’

‘Edward Massey.’

‘The hero of Gloucester? Well, one can’t sneer at him. It’s a pity, though, that his best successes occurred whilst fighting for the Parliament. A number of good English Royalists may balk at serving under a former enemy.’

Ashley eyed him with foreboding. ‘Hamilton.’

‘The parsons like that family less than the devil. They’ll be snapping at his heels like terriers. Still … I suppose he may be luckier than his late brother. Any more?’

‘The Earl of Derby.’

Sir William laughed.

‘Oh – please! That man never got anything right in his life. The only thing he’s any good at is starting quarrels – and, in the company you’ve described, there’ll be plenty of opportunity for that.’ The laughter faded and, in a different tone, he said, ‘I’m sorry, Ashley. I’m desperately sorry … but I don’t think you’ve a cat in hell’s chance. And it’s not just the lack of good leadership. Very few Cavaliers will fight beside the Scots – and none of the Scots will have anything to do with the Catholics. What hope can such a clutch of ill-assorted factions have against the New Model? Cromwell will chew it up and spit out the pips.’

This time the silence yawned like a cavern. Then Ashley said ruefully, ‘I hope you’re wrong … though I suspect you’re not. But you see, Charles is set on it, if only the Scots will agree. And what other option is there?’

‘Truthfully?’ Will’s smile was faintly twisted. ‘None.’

‘None,’ agreed Ashley. ‘So even if failure is guaranteed, I can’t just wash my hands of it, can I?’

‘Actually, that might be the most helpful thing you can do. You and everyone else who has both a brain and enough field experience to recognise when the writing’s on the wall.’

‘It’s not that simple, Will. I can’t abandon Charles. Not only because if an invasion does take place, he’ll go with it – but because, if he’s to make a better job of kingship than his father, he needs the right sort of men around him now. Englishmen without a religious axe to grind … and ones who don’t keep their brains in their breeches. You see?’

‘Only too well. You’ll go with Charles and, if necessary, you’ll die for him … but not for any of the excellent reasons you’ve just put forward.’ Sir William paused and reached for the bottle. ‘You’ll do it because you’d never forgive yourself if you didn’t. And so, having established that point, we may as well get drunk.’

* * *

Colonel Peverell arose next morning with mill-wheels grinding inside his head and the aggravating knowledge that he only had himself to blame. Gritting his teeth, he washed, shaved, dressed … and decided he was never going to drink again. Then, unable to face breakfast, he went off to reclaim his hired horse from the stables where he had lodged it.

It was only then, whilst paying his shot, that he found the crumpled playbill from the Theatre du Marais still in his pocket … and, by process of elimination, worked out that the stunning red-head who’d played the maid-servant rejoiced under the name of Mademoiselle de Galzain.

He was half-way back to the coast before it occurred to him to wonder why he’d wanted to know.

~ * * ~ * * ~

I should explain that The King’s Falcon is only about 20% written as yet and therefore will not become available for some time. I have released this sample purely to give a glimpse into the direction the book will be taking.

Stella Riley

THE KING’S FALCON

The following is a sample from THE KING’S FALCON

Roundheads & Cavaliers #3

by STELLA RILEY

All rights reserved. This sample may not be reproduced in any form.

In the Prologue of The King’s Falcon, we join Eden Maxwell at the battle of Dunbar in September 1650. It is not included in this sample.

ONE

On the first day of January, 1651, Francis Langley stood at the back of Scone Cathedral and watched a tall young man, five months short of his twenty-first birthday, receive – as a reward for several months of gritting his teeth – something which already rightfully belonged to him.

On the surface, the occasion looked just as it should. The young Prince, robed as befitted his station and with the royal regalia laid out before him, sat beneath a crimson velvet canopy held aloft by the eldest sons of six Earls. The vacant throne stood atop an impressive stage, some four feet off the ground and covered in rich carpets … around which the flower of Scottish nobility, splendidly attired, rubbed elbows with the cream of the Kirk. But there the illusion ended. For the crowning of a king, though a serious business, ought also to contain an element of rejoicing; and this one had so far been about as cheerful as an interment.

It wasn’t a surprise. After forcing Charles to take both Covenants, making him publicly repent the sins of his parents as well as his own and ordaining two fast days, the Scots were scarcely likely to allow the coronation itself to be marred by any hint of pleasure. The handful of English Royalists had been relegated to the edges; the Engagers, those gentlemen who’d fought for the late King at Preston, had been prohibited altogether; and the only persons permitted to have a hand in the ceremony itself were those whose Covenanting principles met the exacting standards of Archibald Campbell, Marquis of Argyll. Francis, of course, wasn’t supposed to be there at all – which is why he was lurking as unobtrusively as possible in a dimly-lit corner.

The Moderator of the General Assembly delivered an epic sermon, liberally laced with gloom. Major Langley shifted his shoulders against the cold stone, smothered a yawn and let dire warnings about tottering crowns and sinful kings flow over him. One became immune, after a time, to austere Scottish strictures. And a formal crowning would do much to dilute such humiliations.

Charles knelt to affirm his oath to the Covenants. His voice was devout enough and his promise to establish Presbyterianism in his other dominions was made without a hint of either reluctance or cynicism. Francis smiled, silently applauding … and immediately found himself encompassed by the obliquely considering stare of the fellow who’d ridden in on the previous evening with a bundle of heavily-sealed letters. Francis responded with one sardonically raised brow before restoring his attention to the ceremony. Not everyone, he reflected, thought this particular game worth the candle.

Charles ascended to the waiting throne. Lord Lyon, the King of Arms, announced that he was the rightful and undoubted heir of the Crown and those present responded with a resounding cry of God save the King, Charles the Second! – upon which His Majesty was escorted back to the chair he’d occupied during the interminable sermon for the reading of the Coronation Oath. Francis watched Charles kneel to affirm this before being invested with kingly robes and the articles of state; he set his jaw and suppressed a desire to fidget when the minister prayed that the Lord would purge the Crown from the sins and transgressions of them that did reign before; and he let out a breath he hadn’t known he’d been holding when the Marquis of Argyll finally placed the crown on Charles’s head.

The tradition of anointing the sovereign had been dispensed with as superstitious ritual but, at long last, Charles was declared King of Great Britain, France and Ireland; and, amidst more pious exhortations from the Moderator, he was led to the throne so that the nobles could touch the crown and swear fidelity.

‘Argyll the kingmaker,’ murmured the courier. ‘And even more Friday-faced than usual. The débâcle at Dunbar, do you think? Or perhaps it’s merely that squint of his.’

Francis turned his head and encountered a gleaming stare.

‘Both, I imagine.’

‘But one more than the other,’ came the bland reply. ‘Contrary to present appearances, his power isn’t quite what it was. One even hears rumours of the return of Hamilton.’

Wondering where someone who’d only just arrived might have picked up that particular rumour, Francis said gently, ‘Does one? I wouldn’t know. But it would certainly account for Argyll’s expression … even allowing for the squint.’

The other man said nothing. The Scots finished swearing fealty and King Charles the Second rose to solemnly beseech the ministers that if at any time they saw him breaking his covenant, they would instantly tell him of it. Then, with becoming dignity and a flourish of trumpets, the royal procession passed back down the aisle … and, in due course, Francis found himself outside with the rest.

His companion from the cathedral was nowhere to be seen and, instead, his arm was taken by the Duke of Buckingham, who drawled, ‘The throne’s gain is clearly the theatre’s loss. Such clarity of diction despite having his tongue firmly in his cheek! I’m impressed.’

‘And indiscreet,’ sighed Francis. ‘Shall we go? It’s extremely cold and the banquet awaits.’

‘It’s bound to be dreary. There will be speeches, God help us all … and insufficient wine to drown them out. But I’m amazed the coronation committee thought fit to invite you – if, indeed, they did? Come to think of it, I’m not entirely sure why they asked me.’

It wasn’t true, of course. Twenty-two years old, blessed with startling good looks and frequently too clever for his own good, George Villiers, second Duke of Buckingham, was not used to being ignored.

Smiling faintly, Francis said, ‘For your entertainment value, George. Why else?’

‘Do you think so? I thought it had rather more to do with my having been more or less reared alongside the Lord’s unanointed. But I daresay you know best … so I’ll try to live up to everyone’s expectations.’

Inside the banqueting chamber, wax candles burned bright and log fires blazed in the great hearths. Long tables gleamed with silver plate, fine glassware and monogrammed damask and, winnowing between these and the arriving guests, liveried servants handed out cups of spiced wine. No expense, it appeared, had been spared. It was just a pity, thought Francis, that the company wasn’t better.

Undeterred by the fact that His Majesty was still hemmed in by Argyll and a clutch of black-clad ministers, Buckingham sauntered towards him. Francis made polite conversation with various acquaintances and then took his place, as directed, at one of the lower tables with the rest of his unwelcome compatriots.

‘Well, well,’ said a familiar voice cheerfully. ‘You again. We are obviously perceived to be of the same lowly status. Or do I mean tarred with the same brush?’

Francis turned slowly and took his time about replying.

Of roughly his own age and height, the courier was as fair as he himself was dark and dressed in well-worn buff leather. Knowing how few Royalists had any money these days and aware that his own blue satin was decidedly shabby, Francis passed over this sartorial breach and concentrated on the intelligence evident in the fine-boned face and the gleam of humour in the dark green eyes.

Holding out his hand, he said lightly, ‘Francis Langley – unemployed Major of Horse.’

His fingers were taken in a cool, firm grip.

‘Ashley Peverell – jack-of-all-trades,’ came the reply. And, dropping into the adjacent seat, ‘Don’t tell me. You were purged from the army before Dunbar?’

‘Well before it. And you?’

‘Oh – I was already persona non grata.’ Bitterness mingled oddly with nonchalance. ‘I fought at Preston – for all the good that did.’

An Engager, then, thought Francis. If Argyll knew that, the door would have been slammed in your face. But it explains how you know about Hamilton. He said merely, ‘Quite. I was at Colchester.’

‘Ah. Then you doubtless have better cause for resentment than I. However. At least you haven’t become a glorified errand boy.’

The conversation had arrived, quicker than Francis expected, at the point which interested him. He said, ‘The letters you took to the King last night?’

‘The very same. Speculation rife, is it?’

‘Naturally. Anything to break the monotony.’

Ashley Peverell grinned.

‘A cry from the heart, if ever I heard one. But I’m afraid I’m going to disappoint you. I’ve merely been doing the rounds in England. You know the sort of thing. Can you offer a few guineas to help feed and clothe your King? Alas, sir, I can barely feed and clothe my family. Can His Majesty rely on your support in the event of another invasion? He has my very good wishes, sir. More than that, I cannot guarantee. And so on and so on and depressingly, unsurprisingly so on.’

Francis frowned. ‘Is it really as bad as that?’

‘Yes. Oh – people are sick of the so-called Commonwealth. They’re tired of the Rump clinging to power while it ordains fines for swearing and penalties for adultery – and they resent the monthly assessments and the Excise. But not everyone will ally themselves with the Scots and many wish His Majesty hadn’t taken the Covenant. Then again, out of the total support I have been promised, experience has taught me not to expect to see more than half of it when the time comes.’

‘You’re turning into a cynic, Ash,’ remarked a voice from the far side of the table. ‘It won’t do, you know.’

Two pairs of eyes, one green and one deep blue, turned towards the speaker – a thin-faced young man with a shock of unruly brown hair.

‘My God,’ groaned Ashley. ‘Somebody should have warned me.’ Then, laughing and stretching out a hand, ‘How are you Nick? Still looking for dragons to slay?’

‘You could put it that way,’ returned Sir Nicholas Austin, accepting the hand with unabashed good-humour, ‘though I personally wouldn’t. And I suppose you’re going to tell me that there are plenty of them here.’

‘Look around and judge for yourself.’

Nicholas cocked an eyebrow at Francis.

‘Major Langley – I’m shocked. I thought you only had truck with respectable people.’

‘One tries,’ murmured Francis. ‘As it happens, Mr Peverell and I have only just met.’

Nicholas blinked and opened his mouth to speak. Forestalling him, Ashley said, ‘Hallelujah. The food is coming. Along, I hope, with another jug of claret.’

Taking the hint, Nicholas said, ‘Hold on to that hope but don’t rely on it. They’ll be making sure no one gets drunk. After all, it would be a pity if we started to enjoy ourselves, wouldn’t it?’

The food was good and plentiful. Capons jostled numerous varieties of fish, venison sat cheek-by-howl with partridge and woodcock, and delicately flavoured creams and custards nestled between pastries filled with beef and apricots. The wine, on the other hand, continued to arrive slowly and in niggardly quantities. Even the King, still politely listening to Argyll, was frequently seen to be nursing an empty glass.

Ashley diverted a flagon from a table to his right and Francis liberated another from the one behind him. Vociferous complaints arose. Laughing, Nicholas passed both jugs back – empty. From his place beside Charles, his Grace of Buckingham watched enviously.

‘It seems to me,’ remarked Ashley Peverell at length, ‘that our sovereign lord deserves a small celebration more in keeping with his tastes.’

‘I daresay,’ agreed Francis. ‘But exquisite ladies of easy virtue don’t exactly abound in Perth. And his reputation is widespread enough already.’

‘His bastard by Lucy Walter? Quite. But he must be able to enjoy himself outside the bedchamber. Amidst friends, for example … over a few bottles, in the private room of a tavern. It shouldn’t be too difficult to arrange.’

Francis looked at him.

‘Is that a suggestion?’

‘Call it more of a challenge.’

Major Langley lifted one dark brow.

‘A challenge? How medieval. But I think … I really think I must accept.’

* * *

In the end, the party in the upper room of the Fish Inn to which Charles was discreetly conducted later that evening, was augmented by two persons. Buckingham – because, as the King’s closest friend, he couldn’t be left out; and Alexander Fraizer, because his ability to mingle medicine with intrigue meant that he’d find out anyway. Also, as Ashley pointed out, after the amount they’d all eaten and the amount they intended to drink, a doctor might come in handy.

To preserve His Majesty’s incognito, bottles were fetched and carried by Ashley’s servant, Jem – a burly individual whose fund of thieves’ cant made Francis wonder where Mr Peverell had found him and soon had the King memorising phrases.

By the time toasts had been drunk and the coronation thoroughly dissected and joked about, everyone was pleasantly mellow. Then Charles said, ‘Try not to laugh your boots off, gentlemen – but Argyll thinks I should marry.’

‘Does he?’ Buckingham reached for the bottle. ‘How quaint of him. And whom does he suggest as a potential bride?’