Carl Zimmer's Blog, page 70

February 25, 2011

World Science Festival TV: Another afternoon shot

I really do have work to do. So I'm profoundly resentful (in the best way possible) that the World Science Festival has launched a video site called WSFtv. Here's seven minutes of neuroscientist Giulio Tononi (subject of my recent New York Times profile) talking about his theory of consciousness. There is a lot more where that came from.

Science Home Movies and Technical Ships in a Bottle

I've had a long-running email conversation with Randy Olson, a biologist-turned-film-maker, about what works and what fails when you are trying to convey science to the world at large. In his documentary Flock of Dodos, Randy looked at how creationists made inroads in his home state of Kansas. Randy argued in the movie that evolutionary biologists needed to learn how to do a better job of talking about their work to the public, especially when there's a well-funded publicity machine operating on the other side. Otherwise, they end up sounding obtuse and high-handed.

I've had a long-running email conversation with Randy Olson, a biologist-turned-film-maker, about what works and what fails when you are trying to convey science to the world at large. In his documentary Flock of Dodos, Randy looked at how creationists made inroads in his home state of Kansas. Randy argued in the movie that evolutionary biologists needed to learn how to do a better job of talking about their work to the public, especially when there's a well-funded publicity machine operating on the other side. Otherwise, they end up sounding obtuse and high-handed.

Olson makes a similar point in his book, Don't Be Such A Scientist. In one chapter he takes a close look at how his fellow ocean scientists worked long and hard on a massive report on the state of the oceans (it's in a bad way), convinced that the sheer poundage of the report would send ripples through the country and lead to concrete actions to deal with the crisis. After the report made its great thunk, nothing of the sort happened. The scientists simply didn't have any way of ...

February 24, 2011

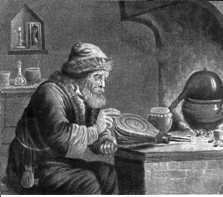

Give the alchemists their credit

The Economist reports from this year's AAAS meeting about a fascinating lecture delivered by the historian of science Lawrence Principe about his quest to figure out the real history of alchemy. Principe has done some impressive work to brush away the Whig history of modern chemistry and understand alchemy on its own terms.

The Economist reports from this year's AAAS meeting about a fascinating lecture delivered by the historian of science Lawrence Principe about his quest to figure out the real history of alchemy. Principe has done some impressive work to brush away the Whig history of modern chemistry and understand alchemy on its own terms.

Alchemy is saddled with such a bad reputation that many people don't appreciate how it played an important role in the birth of modern sciences, such as biochemistry and neurology.

Here's part of a blog post I wrote in 2006 on this surprising link:

Jan Baptist van Helmont, a sixteenth-century Belgian alchemist, carried out a classic experiment on biological growth. He put a five pound willow sapling in a tube of 200 pounds of earth. For five years he gave the tree nothing but water, and then weighed both tree and earth. The tree had grown to 169 pounds, while the earth had lost a few ounces. "Hence one hundred and sixty-four pounds of wood, bark, and roots have come up from water alone," he announced. Van Helmont believed that the willow was nothing more than transmuted ...

Are there aliens worth saving?

Behold the Japanese white-eye, considered an invasive species in its new home in Hawaii. Yet the bird does something that conservation biologists might considered useful for sustaining ecosystems: it spreads the seeds of native Hawaiian plants. Get rid of the Japanese white-eye, and you get rid of its service.

Behold the Japanese white-eye, considered an invasive species in its new home in Hawaii. Yet the bird does something that conservation biologists might considered useful for sustaining ecosystems: it spreads the seeds of native Hawaiian plants. Get rid of the Japanese white-eye, and you get rid of its service.

In Yale Environment 360 this morning, I take a look at a controversial proposal that's making its way into the peer-reviewed biology literature: some invasive species are actually beneficial. I wrote about the complicated relationship between invasive species and biodiversity a couple years ago in the New York Times. In my new article, I focus on two new papers (here and here) in which scientists are advancing these ideas further. Reconsidering invasive species is just one part of a bigger vision they're offering: in a human-dominated world, we will often have to give up the idea of restoring ecosystems to a pre-human state; instead, we should focus on ensuring the ecosystems are as resilient as possible, because they're going to be facing even tougher times in years to come.

As one of the scientists say, the idea is now edgy, ...

February 21, 2011

Sex-twisted frogs in the suburbs

I sat down recently with ecologist David Skelly to talk about the strange things happening to frogs these days. A few years back, scientists found evidence suggesting that pesticides were causing sexual deformities in frogs that lived near farms. Now Skelly is finding that the situation is actually a lot more dire for frogs in suburbs and cities. Over at Yale Environment 360, you can read our Q & A about what sort of chemical cocktail may be making eggs grow in the testes of male frogs–and what it may all mean for us fellow vertebrates.

I sat down recently with ecologist David Skelly to talk about the strange things happening to frogs these days. A few years back, scientists found evidence suggesting that pesticides were causing sexual deformities in frogs that lived near farms. Now Skelly is finding that the situation is actually a lot more dire for frogs in suburbs and cities. Over at Yale Environment 360, you can read our Q & A about what sort of chemical cocktail may be making eggs grow in the testes of male frogs–and what it may all mean for us fellow vertebrates.

[Image: Telemudcat at Flickr, Creative Commons License ]

February 17, 2011

Darwin lecture now on Youtube

Here's the video of the lecture I gave last week at Stony Brook University, which was the basis of my recent blog post. I've uploaded the slides as a pdf here. I'm not sure what the ideal combination of video and slides would be…if anyone has any suggestions, let me know.

How The Simpsons make us human

If you're interested in language, computers, and human cognition, check out my brother Ben's first piece for the Atlantic, in which he pops the hype balloon that has inflated around the Watson computer's performance on "Jeopardy." Suddenly, my stash of Simpsons trivia has become profound!

If you're interested in language, computers, and human cognition, check out my brother Ben's first piece for the Atlantic, in which he pops the hype balloon that has inflated around the Watson computer's performance on "Jeopardy." Suddenly, my stash of Simpsons trivia has become profound!

February 16, 2011

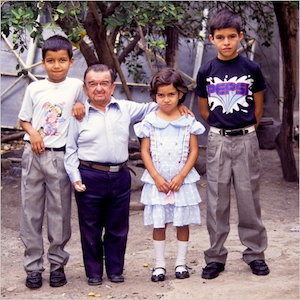

Escaping youth's double-bind?

Nicholas Wade reports today in the New York Times on a tantalizing study that may offer some insight into the evolution of aging, the subject of my recent Darwin Day lecture. An extended family in Ecuador carries a mutation that seems to leave them completely free of cancer and diabetes. The mutation affects a growth hormone receptor on their cells, so that the cells produce low levels of a growth factor. As I mentioned in my lecture, scientists have studied animals with this same mutation, and they can live to amazingly old ages–the life span of C. elegans worms doubles, for example.

Nicholas Wade reports today in the New York Times on a tantalizing study that may offer some insight into the evolution of aging, the subject of my recent Darwin Day lecture. An extended family in Ecuador carries a mutation that seems to leave them completely free of cancer and diabetes. The mutation affects a growth hormone receptor on their cells, so that the cells produce low levels of a growth factor. As I mentioned in my lecture, scientists have studied animals with this same mutation, and they can live to amazingly old ages–the life span of C. elegans worms doubles, for example.

The story with the Ecuadorians is not cut and dried, however. While they may be blissfully free from cancer and diabetes, they don't live to be 160 years old. They die at a normal age of other causes. What's more, as I mentioned in my lecture, the Methuselah worms trade long life for reproductive success–a prediction that comes out of evolutionary theory. There's one obvious trade-off that the Ecuadorian family experiences: they have a severe form of dwarfism. On the other hand, their mutation does not ...

When plants become ultrafast killers, it's time to slow the camera down

In my National Geographic article last year on carnivorous plants, I mentioned one particularly swift killer, the bladderwort. This aquatic plant grows little suction traps that can be triggered by passing animals. In a new paper in the Proceedings of the Royal Society, French researchers take the closest look yet at these ultrafast killers. They find that the door to the traps buckles like a popped bubble of chewing gum–but can then almost immediately swing back shut. Along with the new study on jumping fleas I wrote about last week, this is evidence of how far we're just starting to explore the world of quick biology.

Science News has a nice write-up, and here is an excellent YouTube video provided by a co-author of the study, Philippe Marmottant, a physicist at Joseph Fourier University in Grenoble, France–complete with computer simulation, rubber-cap demos, and groovy soundtrack.

February 15, 2011

The Price of Youth: My Darwin Day 2011 Lecture

Over the weekend, Charles Darwin turned 202. I celebrated in Stony Brook on Long Island–which just so happens to be a very appropriate place to mark the event. Stony Brook University was the intellectual home of one of Darwin's most important followers, the scientist George Williams. Williams may not be a household name, but for evolutionary biologists he looms large. Some fifty years ago, he framed some of the most important questions they are still seeking to answer answer today.

Over the weekend, Charles Darwin turned 202. I celebrated in Stony Brook on Long Island–which just so happens to be a very appropriate place to mark the event. Stony Brook University was the intellectual home of one of Darwin's most important followers, the scientist George Williams. Williams may not be a household name, but for evolutionary biologists he looms large. Some fifty years ago, he framed some of the most important questions they are still seeking to answer answer today.

I was invited to Stony Brook University to give a Darwin Day lecture, and since Williams died last September at 84, I decided to make it a kind of scientific eulogy for him. It was an honor to have the chance to do so, but there was also a bittersweet irony to the experience. For the last few years of his life, Williams suffered from dementia (which may have been Alzheimer's disease or Lewy body dementia, according his wife, Doris). The fact that millions of older people get dementia was exactly the sort of phenomenon that fascinated Williams throughout his career. Why, he wondered, do we ...