Alex Soojung-Kim Pang's Blog, page 103

November 20, 2012

Distraction Addiction Flickr set and slideshow

I thought it would be interesting to create a photo set that mixes images I use in my contemplative computing talks, with photos from Cambridge and my year writing the book.

It's currently rather on the long side, but perhaps I'll get it cut down to a clean 100 pictures, or 50, or something that doesn't exhaust everyone. Right now there's a kind of Brian Eno ambient imagery gone mad quality to it.

November 16, 2012

Ancient multitasking is older than we thought: Evidence from stone spear use and arrow manufacture

When I was at Cambridge (almost two years ago!), I stumbled on the work of cognitive archaeologists Lambros Malafouris and Colin Renfrew. Renfew is a professor at Cambridge with whom I had a really interesting lunch, while Lambros is a fellot at Oxford (and one of those brilliant young academics who in a more generous and expansive era would have gotten tenure years ago). They in turn led me to studies of ancient multitasking, particularly Monica Smith's reconstruction of multitasking in everyday ancient life and Lyn Wadley's work on halfting.

So naturally new research indicating that halfting is a much older practice than we realized caught my eye. Science has a new article on the subject, which is summarized on the AAAS Web site:

Early humans were lashing stone tips to wooden handles to make spears

and knives about 200,000 years earlier than previously thought,

according to a study in the 16 November issue of Science.

Attaching stone points to handles, or “hafting,” was an important

technological advance that made it possible to handle or throw sharp

points with much more power and control. Both Neandertals and early Homo sapiens made hafted spear tips, and evidence of this technology is relatively common after about 200,000 to 300,000 years ago.

Jayne Wilkins of the University of Toronto and colleagues present

multiple lines of evidence implying that stone points from the site of

Kathu Pan 1 in South Africa were hafted to form spears around 500,000

years ago. The points’ damaged edges and marks at their base are

consistent with the idea that these points were hafted spear tips.

So why does this matter? The Guardian explains,

The invention of stone-tipped spears was a significant point in human evolution, allowing our ancestors to kill animals more efficiently and have more regular access to meat, which they would have needed to feed ever-growing brains. "It's a more effective strategy which would have allowed early humans to have more regular access to meat and high-quality foods, which is related to increases in brain size, which we do see in the archaeological record of this time," said Jayne Wilkins, an archaeologist at the University of Toronto who took part in the latest research.

The technique needed to make stone-tipped spears, called hafting, would also have required humans to think and plan ahead: hafting is a multi-step manufacturing process that requires many different materials and skill to put them together in the right way. "It's telling us they're able to collect the appropriate raw materials, they're able to manufacture the right type of stone weapons, they're able to collect wooden shafts, they're able to haft the stone tools to the wooden shaft as a composite technology," said Michael Petraglia, a professor of human evolution and prehistory at the University of Oxford who was not involved in the research. "This is telling us that we're dealing with an ancestor who is very bright."

This joins recent work on arrow-making, which both demonstrates that the manufacture and use of arrows is older than we thought, and that its complexity suggests ancient multitasking abilities:

"These operations would no doubt have taken place over the course of

days, weeks or months, and would have been interrupted by attention to

unrelated, more urgent tasks," observes paleoanthropologist Sally

McBrearty of the University of Connecticut in a commentary accompanying

the team’s report. "The ability to hold and manipulate operations and

images of objects in memory, and to execute goal-directed procedures

over space and time, is termed executive function and is an essential

component of the modern mind," she explains.

McBrearty, who has long argued that modern cognitive capacity evolved at

the same time as modern anatomy, with various elements of modern

behavior emerging gradually over the subsequent millennia, says the new

study supports her hypothesis. A competing hypothesis, advanced by

Richard Klein of Stanford University, holds that modern human behavior

only arose 50,000 to 40,000 years ago, as a result of some kind of

fortuitous genetic mutation that kicked our ancestors’ creativity into

high gear. But discoveries of symbolic items much older than that

supposed mutation–and older than the PP5-6 arrowheads for that

matter–have cast doubt on Klein’s theory. And other finds hint that

Neandertals, too, engaged in symbolic behaviors, which would suggest

that the capacity for symbolic thinking arose in our common ancestor

perhaps half a million years ago.

November 11, 2012

You damn kids get off my lawn, with your misinterpretations of neuroplasticity and media history!

I'm just getting around to Carl Wilkinson's recent Telegraph essay on writers "Shutting out a world of digital distraction." It's about how Zadie Smith, Nick Hornby and others deal with digital distraction, which for writers is particularly challenging. Successful writing requires a high degree of concentration over long periods, but the Internet can be quite useful for doing the sort of research that supports imaginative writing (not to mention serious nonfiction). Add in communicating with agents, getting messages from fans, and the temptation to check your Amazon rank, and you have a powerful device.

Unfortunately, the piece also has a couple paragraphs featuring that mix of technological determinism and neuroscience that I now regard as nearly inevitable. Editors seem to require having a section like this:

the internet is not just a distraction – it’s actually changing our brains, too. In his Pulitzer Prize-nominated book The Shallows: How the Internet is Changing the Way We Think, Read and Remember (2010), Nicholas Carr highlighted the shift that is occurring from the calm, focused “linear mind” of the past to one that demands information in “short, disjointed, often overlapping bursts – the faster, the better”….

Our working lives are ever more dominated by computer screens, and thanks to the demanding, fragmentary and distracting nature of the internet, we are finding it harder to both focus at work and switch off afterwards.

“How can people not think this is changing your brain?” asks the neuroscientist Baroness Susan Greenfield, professor of pharmacology at Oxford University. “How can you seriously think that people who work like this are the same as people 20 or 30 years ago? Whether it’s better or worse is another issue, but clearly there is a sea change going on and one that we need to think about and evaluate.... I’m a baby boomer, not part of the digital-native generation, and even I find it harder to read a full news story now. These are trends that I find concerning.”

As with Nick Carr's recent piece, Katie Roiphe's piece on Freedom, everything Sven Birkets has written since about 1991, and the rest of the "digital Cassandra" literature (Christopher Chabris and Daniel Simons called it "digital alarmism"), I think the problem here is that statements like these emphasize the flexibility of neural structure in a way that ironically diminishes our sense of agency and capacity for change. The argument works like this:

The world is changing rapidly.

Our media are changing very rapidly.

Brains adapt to their (media) environments.

Therefore our brains must be changing very rapidly.

These changes are so vast and fast, we don't have time to adapt.

I don't want to argue, pace Stephen Poole, that this is merely neurobollocks (though I love that phrase), (Nor do i want to single out Baroness Greenfield, who's come in for lots of criticism for the ways she's tried to talk about these issues.)

All I want to argue is that 1-4 can be true, but that doesn't mean 5 must be true as well.

Technological determinism is not, absolutely not, a logical consequence of neuroplasticity.

It's possible to believe that the world is changing quickly, that our brains seek to mirror these changes or adapt to them in ways that we're starting to understand (but have a long way to go before we completely comprehend), and lots of this change happens without our realizing it, before we're aware of it, and becomes self-reinforcing.

But-- and this is the important bit, so listen up-- we also have the ability of observe our minds, to retake control of the direction in which they develop, and to use neuroplasticity for our own ends.

Because we can observe our minds as work, we can draw on a very long tradition of practice in building attention and controlling our minds-- no matter what the world is doing. Yes, the great Jeff Hammerbacher line, "The best minds of my generation are thinking about how to make people click ads" is absolutely true*, but when all is said and done, even Google hasn't taken away free will.

We can get our minds back. It's just a matter of remembering how.

*And can even be represented in graphical form.

November 9, 2012

A Thomas Merton line I must use one day

In the opening paragraph of Mystics and Zen Masters, he contrasts "the monk or the Zen man" to "people dedicated to lives that are, shall we say, aggressively noncontemplative."

That pretty much describes us all these days. Though it's worth noting that Merton published his book in 1961, before the Internet, when even long-distance telephone calls were a rarity in some parts of the U.S.

November 8, 2012

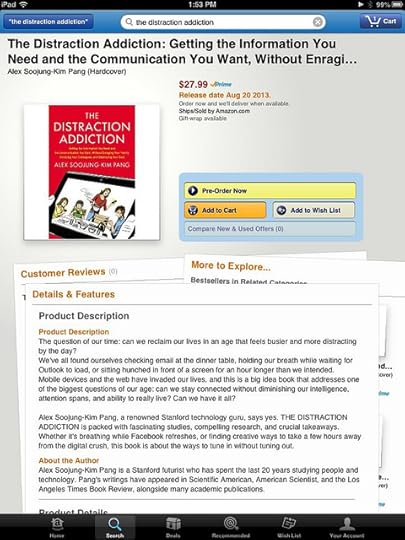

Pre-order The Distraction Addiction!

My book is now available to pre-order on Amazon. Amazing.

via flickr

It's been about two and half years since I first wrote the words "contemplative computing" (or typed them on my iPhone, actually), and nearly two years since I started my fellowship at Microsoft Research Cambridge to explore the idea in depth. It's a bit surreal to watch the book move closer to the bookshelves, but it's also very cool.

November 7, 2012

Google is a search engine, not a Free Will Destruction Machine

The Memory Network has published a new essay by Nick Carr on computer versus human memory. This is a subject I've followed with great interest, and when I was at Microsoft Research Cambridge I had the good fortune to be down the hall from Abigail Sellen, whose thinking about the differences between human and computer memory is far subtler than my own.

Carr himself makes points about how human memory is imaginative, creative in both good and bad ways, changes with experience, and has a social and ethical dimension. This isn't new: Viktor Mayer-Schönberger's book Delete is all about this (though how successful it is is a matter of argument), and Liam Bannon likewise argues that we should regard forgetting as a feature, not a bug.

The one serious problem I have with the piece comes after a discussion of Betsy Sparrow's work on Internet use and transitive memory:

We humans have, of course, always had external, or “transactive,” information stores to supplement our biological memory. These stores can reside in the brains of other people we know (if your friend Julie is an expert on gardening, then you know you can use her knowledge of plant facts to supplement your own memory) or in media technologies such as maps and books and microfilm. But we’ve never had an “external memory” so capacious, so available and so easily searched as the Web. If, as this study suggests, the way we form (or fail to form) memories is deeply influenced by the mere existence of outside information stores, then we may be entering an era in history in which we will store fewer and fewer memories inside our own brains.

To me this paragraph exemplifies both the insights and shortcomings of Carr's approach: in particular, with the conclusion that "we may be entering an era in history in which we will store fewer and fewer memories inside our own brains," he ends on a note of technological determinism that I think is both incorrect and counterproductive. Incorrect because we continue to have, and to make, choices about what we memorize, what we entrust to others, and what we leave to books or iPhones or the Web. Counterproductive because thinking we can't resist the overwhelming wave of Google (or technology more generally) disarms our ability to see that we still can choose to use technology in ways that suit us, rather than using it ways that Larry and Sergei, or Tim Cook, or Bill Gates, want us to use it.

The question of whether we should memorize something is, in my view, partly practical, partly... moral, for lack of a better word. Once I got a cellphone, I stopped memorizing phone numbers, except for my immediate family's: in the last decade, the only new numbers I've committed to memory are my wife's and kids'. I carry my phone with me all the time, and it's a lot better than me at remembering the number of the local taqueria, the pediatrician, etc.. However, in an emergency, or if I lose my phone, I still want to be able to reach my family. So I know those numbers.

Remembering the numbers of my family also feels to me like a statement that these people are different, that they deserve a different space in my mind than anyone else. It's like birthdays: while I'm not always great at it, I really try to remember the birthdays of relatives and friends, because that feels to me like something that a considerate person does.

The point is, we're still perfectly capable of making rules about what we remember and don't, and make choices about where in our extended minds we store things. Generally I don't memorize things that I won't need after the zombie apocalypse. But I do seek to remember all sorts of other things, and despite working in a job that invites perpetual distraction, I can still do it. We all can, despite the belief that Google makes it harder. Google is a search engine, not a Free Will Destruction Machine. Unless we act like it's one.

November 2, 2012

A forgotten piece of the book: an essay on Digital Panglosses versus Digital Cassandras

Chad Wellmon has a smart essay in The Hedgehog Review arguing that "Google Isn’t Making Us Stupid…or Smart."

Our compulsive talk about information overload can isolate and abstract digital technology from society, human persons, and our broader culture. We have become distracted by all the data and inarticulate about our digital technologies…. [A]sking whether Google makes us stupid, as some cultural critics recently have, is the wrong question. It assumes sharp distinctions between humans and technology that are no longer, if they ever were, tenable…. [T]he history of information overload is instructive less for what it teaches us about the quantity of information than what it teaches us about how the technologies that we design to engage the world come in turn to shape us.

It's something you should definitely read, but it also reminded me of a section of my book that I lovingly crafted but ultimately editing out, and indeed pretty much forgot about until tonight. It describes the optimistic and pessimistic evaluations of the impact of information technology on-- well, everything-- as a prelude to my own bold declaration that I was going to go in a different direction. (It's something I wrote about early in the project.)

I liked what I wrote, but ultimately I decided that the introduction was too long; more fundamentally, I was really building on the work of everyone I was talking about, not trying to challenge them. (I don't like getting into unnecessary arguments, and I find you never get into trouble being generous giving credit to people who've written before you.) Still, the section is worth sharing.

Since their earliest days, personal computers and Internet connections have been bundled with what I’ve come to think of as Digital Panglossianism, after the famously optimistic Dr. Pangloss in Voltaire's "Candide." "Those who have asserted all is well talk nonsense," he told his student, Candide; "they ought to have said that all is for the best." Having access to information simply makes people smarter. Having unlimited quantities of information means that you can learn and know anything. The intellectual demands of today's video games, and their social character, helps make us smarter, more collaborative, and just better people, more likely to devote our "cognitive surplus" to worthy world-changing causes.

Contrast this vision with that of the Digital Cassandras. In the Iliad, the god Apollo blessed Cassandra with the ability to see the future, but cursed her with the knowledge that her predictions would be ignored. Given that she foresaw the destruction of her home and royal line (she was a daughter of Trojan king Priam), and knew that her warnings would never be taken seriously, Cassandra tended to be a bit of a pessimist.

Today's digital Cassandras are warning that our technologies are creating problems that we can avoid-- but all often are choosing to ignore. Online spaces that are designed to foster a sense of community, or connect users with friends, end up "offering the illusion of companionship without the demands of friendship," as Sherry Turkle puts it. Further, as Jaron Lanier says, our infatuation with collective intelligence leads to a kind of "digital Maoism." Treating humans as the raw material of metacognition leads us to "gradually degrade the ways in which each of us exists as an individual," he argues, and underestimate "the intrinsic value of an individual's unique internal experience and creativity." It impoverishes both inner life and public life: the Internet's collective intelligence hasn't solved many of the world's problems, but is has watched a lot of cat videos. And finally, of course, Google is making us stupid.

Digital Panglosses and Cassandras disagree about a lot, but they share one common assumption: that the Internet and ubiquitous computing constitute something new. Sven Birkerts talks about a “total metamorphosis” brought about by the Web, of literary practice confronting a “critical mass” of technological and social changes. Pierre Levy talks about the Web as “civilization’s new horizon,” and that “we are moving from one humanity to another.” In other words while they disagree about whether this is to be applauded or feared, they agree that we’re living through an unprecedented period in history.

They share another, even more important, common assumption. Whether they see information technologies having an ultimately positive or negative effect, they both write as if its impacts are inevitable and unavoidable. Forgetting how to read novels will impoverish your inner life, or make you a playful postmodern trickster. Games are breeding-grounds for sociopaths, or training academies for tomorrow's leaders. Social software will usher in a new age of connectivity and community, or make us more isolated and alone than ever. Either way, good or bad, technologies are going to change you, and there's not a lot you can do about it.

Neither side means to promote a sense of passivity and inevitability, but they do. So, I think, do historians of media and technology who try to navigate between the optimistic and pessimistic views of Pangloss and Cassandra. The Web, they argue, is but the latest information technology to change our brains. The invention of writing-- particularly the invention of the Greek alphabet, the first that could accurately reproduce the full range of a language's sounds-- profoundly altered the way we thought. The printing press set information free five hundred years before the Internet, while the newspaper was the first near real-time medium, and a critical foundation for the growth of "imagined communities." The radio, telephone, and television were transforming the world into a "global village" in the 1960s, according to Marshall McLuhan.

Not only have we been living through information revolutions for as long as history can remember; we've lamented the changes, too. Socrates distrusted the new medium of writing. In 1477, the Venetian humanist Hieronimo Squarciafico complained in his "Memory and Books" that "Abundance of books makes men less studious; it destroys memory and enfeebles the mind by relieving it of too much work." A hundred fifty years ago, the telegraph was a "Victorian Internet," talked about in the same apocalyptic and prophetic tones used to describe the Web today.

All this is true, but I think it suffers from two problems. First of all, it's easy to read these histories and conclude that new information technologies have always created problems, and that we've always survived. Eventually, we make peace with the new, or adapt, or forget that things ever were different. Ironically, while many historians of technology see themselves as critics of technological determinism, they end up making the changes we're experiencing seem inevitable and irresistible. History also tends to be cruel to its Cassandras. Socrates' criticism of writing looks pretty stupid given Greek civilization's incredible legacy of philosophy, theatre, science, and literature-- all of which would have been lost, and arguably would never have been created, without writing. Few people remember Thomas Watson's brilliant leadership of IBM; instead, they remember his (perhaps incorrectly-attributed) offhand remark that he couldn't imagine the world ever needing more than five computers.

Second, for all their thoroughness and careful scholarship, these histories offer an incomplete view of the past. It's certainly true that human history is full of technological innovation, and some brilliant scholarship has shown how new information technologies-- some as simple as the use of spaces between words-- have changed the way we write, argue, and think. But it's wrong to assume that only history's losers have resisted the changes, or that we should take as a lesson that today's worries about the decline of focus and attention-- not to mention our own personal sense of dismay at being more distractible and having a harder time concentrating-- are mere historical epiphenomena. In fact, there's a long history of creating systems and institutions that cultivate individual intellectual ability, support concentration, and preserve attention.

Some of humanity's most impressive institutions and spaces are devoted to cultivating memory and contemplation: think of the monastery, the cathedral, or the university, all of which can be seen as vast machines for supporting and amplifying concentration. Or, at a much more personal level, the coffee-house, personal office, and scholar's study all to different degrees support contemplation and deep thought. Contemplative practices themselves have a long history. As historians of religion have noted, Buddhism emerged in a South Asia that was newly urbanized, quickening economically, developing into a global center of trade, and on the verge of supporting large states. Christian monasteries first developed as an alternative to urban living; every culture has its holy men, shamans or witches, but only complex societies need (and can support) monastic institutions with large groups working, praying, and studying together. Early universities straddled a physical and psychic line between drawing on the capital and infrastructure of cities (Paris, Oxford, Bologna and Cambridge were all medieval centers of trade) and providing an intellectual respite from the bustle of trade and machinations of politics.

In other words, alongside the history of technological change, cognitive shifts, and increasing distraction, there is a history of innovation in contemplation. Efforts to create spaces and practices that help people concentrate and be creative are as old as writing and print. This knowledge can help us today. There are specific things we can take from this history in crafting our own responses to today’s digitally-driven pressures: as we’ll see later in the book, there are design principles that we can borrow from contemplative objects and spaces, and apply to information technologies and interactions.

Just as important, this history offers hope. It reminds that for millennia, people haven’t just complained about or resisted the psychological and social challenges presented by new media and information technologies, nor have they passively allowed change to happen. They’ve developed ways of dealing. And some of those practices— like varieties of Buddhist meditation— possess a sophistication and potency that modern science is only now starting to fully appreciate.

The downside of flow: Machine gambling

I'm a big fan of the work of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi: his book Flow is one of the most important thing I've read in the last ten years, and one of those argument and concepts I constantly refer to in my everyday life (not to mention writing about on this blog). I think promoting flow states is one of the healthiest things contemplative computing can do. But one of the first objections I get to the idea that flow is important in contemplative computing runs like this: "My son [or husband] plays spends hours totally immersed in video games. That's definitely a flow experience. And you argue it's a good thing?" (And yes, the subject usually is male.)

They have a point. It's definitely case that game design companies have tried hard to get players "in the zone," in that state where they forget about everything but the game, and don't care about anything but getting to the next level.

Flow has four major components, Csikszenthmihalyi writes in his rapidly-approaching-classic-status book, Flow. "Concentration is so intense that there is no attention left over to think about anything irrelevant, or to worry about problems," he says. "Self-consciousness disappears, and the sense of time becomes distorted. An activity that produces such experiences is so gratifying that people are willing to do it for its own sake, with little concern for what they will get out of it, even when it is difficult, or dangerous."

Here's the problem. Game designers have read Csikszentmihalyi carefully, much in the way aspiring Wall Streeters read Michael Lewis' Liar's Poker: less as an exploration of the moral complexities of design, or as a guide to live the good life, than as a how-to manual. (I'm working on an article on how designers have ignored the moral dimensions of Csikszentmihalyi's argument.) They've learned how to create what I would call flow-like states: mental states that are very absorbing, but which don't offer the long-term gratifications of real flow experiences-- or only do so for a very small number of highly self-aware people.

But it's not just game designers who've done this: an even better example might be machine gambling designers, as Natasha Dow School argues in her new book Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas. As a review of her book explains,

In her book, she looks at what the industry has done to make those devices more compelling. For instance, video slot machines now deliver frequent small wins rather than infrequent large jackpots, to better sustain what she calls "the flow of the experience."...

Schüll's book delves into the lives of compulsive machine gamblers—not the folks playing social games like poker around a table but the smaller percentage of the population who play alone at electronic slot machines or video poker terminals with such intensity that they enter a state of total gambling immersion, shutting out the world for long stretches of time.

As she puts it elsewhere, there's an "intimate connection between extreme states of subjective absorption in play and design elements that manipulate space and time to accelerate the extraction of money from players." This creates players like

Mollie, a mother, hotel worker, and habitual video poker player, who recounted for Schüll her life as a gambler—running through paychecks in two-day binges, cashing in her life insurance. "The thing people never understand is that I'm not playing to win," Mollie says in the book. Instead, she was simply trying "to keep playing—to stay in that machine zone where nothing else matters."

For those who have access to it, her earlier work on digital gambling, and the language of compulsion and addiction in gambling, are well worth reading.

So clearly flow states are things that can benefit game companies and casinos, and can lead people to do things that are pleasurable (or at least narcotizing) in the moment but self-destructive over the long run. Does that mean they should be avoided?

No.

The problem is that flow can be a phenomenally valuable thing, and indeed you can argue-- as Czikszentmihalyi does-- that its pursuit is one route to the Good Life. This is really central to the book: as I noted when I first wrote about it,

What I really like about the book is that it's interested in the fundamental question, what is happiness? Csikszentmihalyi's answer is a bit counterintuitive, but quite rich and interesting. This means he's not just interested in isolated experiences, but in the overall shape and tone of life: it's an interest in values rather than merely specific ends. "Happiness is not something that happens," (2) he argues:

It is a condition that must be prepared for, cultivated, and defended privately by each person. People who learn to control inner experience will be able to determine the quality of their lives, which is as close as any of us can come to being happy.... It is by being fully involved with every detail of our lives, whether good or bad, that we find happiness, not by trying to look for it directly. [Reaching happiness involves] a circuitous path that begins with achieving control over the contents of our consciousness. (2)

This control, he explains, feels like this:

We have all experienced times when, instead of being buffeted by anonymous forces, we do feel in control of our actions, masters of our own fate. On the rare occasions that it happens, we feel a sense of exhilaration, a deep sense of enjoyment that is long cherished and that becomes a landmark in memory for what life should be like. This is what we mean by optimal experience.... Contrary to what we usually believe, moments like these, the best moments in our lives, are not the passive, receptive, relaxing times.... The best moments usually occur when a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile. Optimal experience is thus something that we make happen. (3)

So at its best, flow is something we experience when we're doing hard things not easy ones, when we're most awake and productive, not passive or consuming. I think if anything has changed since Flow appeared in the early 1990s, it's that we've had a couple decades' experience with industries that have learned how to get us to have experiences that feel like flow, but aren't. They tap into our desire for challenging, engaging experiences, but don't deliver the moral rewards or self-improvement. The qualities that make flow powerful and redemptive can also make its manufactured versions dangerous and self-destructive.

Caitlin Zaloom also makes an interesting comparison between financial trading and gambling:

The whirl of markets can also deliver more sensory satisfactions. In the midst of a deal, traders can fully give themselves over to the moment, achieving the optimal experiences that Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls “flow.” Although traders would prefer the analogy with skilled, masculine counterparts like fighter pilots or soccer stars, machine gamblers, like slot or video poker players, may be the accurate comparison case. The architecture and technologies of both markets and casinos structure chaos, creating environments that spark flow experiences. In the heyday of open outcry trading, derivatives exchanges used just this language to justify the markets they made. The pandemonium of the trading pits, they claimed, channeled market competition, helping buyers and sellers make deals as the prices of currencies, pork bellies, and stock indices rose and fell. In the pits, bodies crowded toward every bid shouting matching offers with red-faced tension. Now that derivatives markets have moved online, order seems to reign. Prices and lots blink across screens second by second in neat rows. Whether on the screen or in the pit, the market organizes an experience of acting amid structured chaos that ushers the players toward feelings of mastery and rapt states that athletes and video poker players alike call “the zone.”

Gamblers, like traders, seek out the zone, and gambling spaces and technologies assist in the quest. The anthropologist Natasha Schull has analyzed how gaming architects and entrepreneurs assist players’ entry into the zone and heighten their flow experiences by employing easy curves in gambling floors, engineering ambient noise, and creating a sense of comfortably enclosed space to usher gamblers toward absorption in the games. One leading design firm, she reports, calls this the “immersion paradigm.” They fashion environments “to hold players in a desubjectified state so as to galvanize, channel, and profit from” the experience of gaming oblivion.7 During play, gamblers lose sense of space and self. Completely captivated by the swift shifts in their glowing cards, their sense of their own presence dissolves into the smooth motion of poker hands through time. With credit cards racking up a tally and waitresses offering ample drink, gaming designers make sure that only bathroom breaks interrupt.

Traders, like gaming designers, manipulate bodies, machines, and mental states to promote peak experience; and they pride themselves on the ability to delay the call of nature while they are holding a position. The gaming industry employs the intimate experiential requirements of the zone to encourage gamblers to play “faster, longer, and more intensively.” Similarly, traders engage with machines and frame their senses of physical and social space to merge with the flow of the market.

Skiing isn't exciting enough? Add email and phone calls!

For those of you who don't like to get away when you're getting away:

It is the gadget that every workaholic will be clamouring for – a pair of ski goggles that let you read your emails while on the slopes.

The £500 Oakley Airwave has a fighter pilot-style screen on the inside of the lens, displaying a skier’s speed, location, altitude and distance travelled as they zoom down the slopes.

The goggles can also connect to an iPhone or Android phone or tablet, transmitting incoming calls to an earpiece.

Anyone who leads a life in which a device like this actually makes sense needs to 1) stay away from the slopes so you don't hurt other people, and 2) think about your life.

On a more serious note, this is an expensive and slightly extreme example of a problematic assumption: that everything is made better when you add connectivity. Driving somewhere? Have your GPS unit Tweet your location! Is tonight's sushi dinner delicious? Say it on Facebook!

No.

October 23, 2012

Slow… everything… at the RSA

A couple years ago I got (improbably) an invitation to join the RSA, the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce. (An acquaintance of mine had just gone to work for them.) Money was a bit tight so I passed, but perhaps it's time to sign up, given their interest in Slow Movement(s) and mindfulness.

This post about mindfulness and Daniel Kahneman's work is also good.