Natylie Baldwin's Blog, page 143

May 12, 2023

Christopher Mott: The Democratist War on Diplomacy

By Christopher Mott, The National Interest, 4/17/23

While the long-term results of the People’s Republic of China’s diplomatic outreach into both the Middle East and Ukraine remain unknown, it is apparent that the foreign policy establishment in Washington DC was taken aback by the speed at which Beijing’s reputation is rising. They shouldn’t be. The long-running Saudi-Iranian rivalry has been partially fueled by the United States, meaning that Washington could never serve as a reliable mediator for all parties. China’s distance and relatively non-partisan-seeming approach to the region, however, enables more parties to be willing to at least discuss putting aside one of the more dangerous rivalries of the twenty-first century. Elsewhere, India plays an agile game of diplomacy, neither endorsing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine nor rejecting its long-standing and beneficial security relationship with Moscow that dates back to independence. Brazil, increasingly, tows no one’s line at the UN and is quick to question narratives from the great powers. France asserts that European core interests and North American core interests are rapidly diverging.

Commentary on the return of the multipolar world has rightfully arisen. The industrial and economic share of American power on the global stage has narrowed considerably since its heydays in the Cold War and even at the start of the twenty-first century. Regardless of what anyone thinks about it, the multipolar world is already here. And rather than being regarded as some great shock or oddity, a multipolar world is in fact the normal condition of the international system. What we are seeing now is the world emerging out from under an outlier period and into something more typical with the majority of history. It is apparent by the actions of countries like China, India, and Brazil that most of the world knows this and is working towards adapting to such a future.

But the United States and many of its dependent allies are not. The rhetoric from places such as Washington and London is one of appealing to the logic of a “New Cold War”, where an “Axis of Authoritarianism” is rising between China and Russia that seeks to wage an ideological battle against “The Free World” in a bid for total global supremacy. With the possible exception of a reactive and increasingly culture war-obsessed Russia, however, few outside of the North Atlantic world take this rhetoric seriously. They have already moved on to focus on their regional self-interest. This begs the question: how can so much of the foreign policy class in the Beltway continue sacrificing the outcome of results for more tired declarations of loyalty to an ideology of global conflict over universal values? What is it that holds Anglo-American elites in thrall to a way of viewing the world which was questionable even in the Cold War, but is surely beyond unhelpful now?

Last year, the scholar Dr. Emily Finley released an important and comprehensive book that charts the history of this worldview. In The Ideology of Democratism, Finley charts how the world view of Rousseau, built upon by later additions coming from Thomas Jefferson, Woodrow Wilson, John Rawls, Leo Strauss, and up through the Bush Era neoconservatives, injected a universalist faith in liberal democracy as the guiding principle of not just specific societies and local circumstances (the preference of Washington, Hamilton, and the early Federalists in U.S. history), but of the entire world. Democratic systems are no longer outgrowths of particular historical and geographic circumstances but are taken to be the inevitable destiny of all of mankind. For a democracy to be threatened anywhere is to be threatened everywhere. Thus, democracy becomes a kind of civic religion known as “Democratism.”

One of the paradoxes of Democratism, as described by Finley, is that the democratist claims to speak “for the people” while also being highly dismissive of local concerns or popular opinion should these contradict the missionary mentality of expansion of democracy abroad or deviate from the plans of democracy experts. The “national will” is not something left up to individual elections but is rather a long-term project that can only be entrusted to the technocrats of democratic governance. In other words, only the democratists themselves can govern policy because only the mission of democratization is a legitimate purpose for a government whose goals transcend day-to-day concerns about security and infrastructure. Finley contends that this is now the default ideology of the governing and media classes in the North Atlantic, and especially in the foreign policy establishment of Washington. In a world where the U.S. expects Europe to hold solidarity with it on Taiwan (or Japan to not breaks ranks sanctioning Russia over Ukraine), it becomes apparent that, whether cynically or genuinely used, democratism is the rhetoric if not the purpose of present-day global over-extension.

While not the entirety of the reason why the Beltway struggles to shed its imperial hubris and adapt to the new multipolar world, (much of that is simply complacency) understanding democratism’s hold over the governing elite is vital for explaining the unique hostility found in so much of foreign policy commentary towards a soberer and more realistic appraisal of the world. From the bafflement expressed at countries failing to rally behind support for Ukraine and sanctions on Russia, to the clueless exhortations for a “values-based” diplomacy that prioritizes a nation’s domestic politics over its strategic opportunities, democratists will not concede that perhaps their worldview is unsuited for the proper practice of diplomacy under conditions of multipolarity. Particularly in a world where non-liberal powers have a variety of localized interests and abilities to assert themselves to greater degrees than were previously possible.

Perhaps the most damaging manifestation of the democratist worldview is the assignment of a type of karma point system to how nations are ranked. “Good” countries have policies that reflect Anglo-American norms and thus are worthy of some sovereignty, while “bad” countries can have their sovereignty violated on a economic or humanitarian pretext for failing to play their assigned role in the view of North Atlantic policymakers. The backlash this inevitably causes is taken as further proof that this contest for political power is a Manichean struggle of good versus evil which is existential, rather than a clash of interests that could be solved by diplomacy. Such tendencies serve only to drive nonaligned powers further away from partnership with countries enthralled by the democratist worldview.

Geopolitics is the contest for resources and power among territorial units jealous of their security and suspicious of their rivals. The rising and more assertive middle powers cannot coast on the received wisdom of ahistorical ideological projects, they must develop and survive. Having no comforting mythological narrative to blind them, they embrace the world as it is, rather than as they wish it to be. It is this that gives them a key advantage over a self-indoctrinated global power whose commitment to democratist and exceptionalist rhetoric prevents it from adapting to the very real world in which its power is embedded. Nations that understand this dynamic will outperform expectations and those that do not will comparatively underperform. You can have effective situational crisis management, or you can wage a global jihad for abstract universal values. You cannot have both.

Christopher Mott (@chrisdmott) is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Peace and Diplomacy and the author of the book The Formless Empire: A Short History of Diplomacy and Warfare in Central Asia.

May 11, 2023

Ben Freeman & William Hartung: The 21st Century of (Profitable) War

Photo by Dylan on Pexels.com

Photo by Dylan on Pexels.comBy Ben Freeman, William Hartung and Tom Englehardt, TomDispatch, 5/4/23

Honestly, it should take your breath away. We are on a planet prepping for further war in a staggering fashion. A watchdog group, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), just released its yearly report on global military spending. Given the war in Ukraine, you undoubtedly won’t be surprised to learn that, in 2022, such spending in Western and Central Europe surpassed levels set as the Cold War ended in the last century. Still, it wasn’t just Europe or Russia where military budgets leaped. They were rising rapidly in Asia as well (with significant jumps in Japan and India, as well as for the world’s second-largest military spender, China). And that doesn’t even include spiking military budgets in Saudi Arabia and elsewhere on this embattled planet. In fact, last year, 12 of the 15 largest military spenders topped their 2021 outlays.

None of that is good news. Still, it goes without saying that one country overshadowed all the rest – and you know just which one I mean. At $877 billion last year (not including the funds “invested” in its intelligence agencies and what’s still known as “the Department of Homeland Security”), the U.S. military budget once again left the others in the dust. Keep in mind that, according to SIPRI, Pentagon spending, heading for a trillion dollars in the near future, represented a staggering 39% of all (yes, all!) global military spending last year. That’s more than the next 11 largest military budgets combined. (And that is up from nine not so long ago.) Keep in mind as well that, despite such funding, we’re talking about a military, as I pointed out recently, which hasn’t won a war of significance since 1945.

With that in mind, let Pentagon experts and TomDispatch regulars William Hartung and Ben Freeman explain how we’ve reached such a perilous point from the time in 1961 when a former five-star general, then president, warned his fellow citizens of the dangers of endlessly overfunding the – a term he invented – military-industrial complex. Now, let Hartung and Freeman explore how, more than six decades later, that very complex reigns supreme. ~ Tom Engelhardt

Unwarranted Influence, Twenty-First-Century-StyleBy Ben Freeman and William D. Hartung

The military-industrial complex (MIC) that President Dwight D. Eisenhower warned Americans about more than 60 years ago is still alive and well. In fact, it’s consuming many more tax dollars and feeding far larger weapons producers than when Ike raised the alarm about the “unwarranted influence” it wielded in his 1961 farewell address to the nation.

The statistics are stunning. This year’s proposed budget for the Pentagon and nuclear weapons work at the Department of Energy is $886 billion – more than twice as much, adjusted for inflation, as at the time of Eisenhower’s speech. The Pentagon now consumes more than half the federal discretionary budget, leaving priorities like public health, environmental protection, job training, and education to compete for what remains. In 2020, Lockheed Martin received $75 billion in Pentagon contracts, more than the entire budget of the State Department and the Agency for International Development combined.

This year’s spending just for that company’s overpriced, underperforming F-35 combat aircraft equals the full budget of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And as a new report from the National Priorities Project at the Institute for Policy Studies revealed recently, the average taxpayer spends $1,087 per year on weapons contractors compared to $270 for K-12 education and just $6 for renewable energy.

The list goes on – and on and on. President Eisenhower characterized such tradeoffs in a lesser known speech, “The Chance for Peace,” delivered in April 1953, early in his first term, this way: “Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed. This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children…”

How sadly of this moment that is.

New Rationales, New Weaponry

Now, don’t be fooled. The current war machine isn’t your grandfather’s MIC, not by a country mile. It receives far more money and offers far different rationales. It has far more sophisticated tools of influence and significantly different technological aspirations.

Perhaps the first and foremost difference between Eisenhower’s era and ours is the sheer size of the major weapons firms. Before the post-Cold War merger boom of the 1990s, there were dozens of significant defense contractors. Now, there are just five big (no, enormous!) players – Boeing, General Dynamics, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Raytheon. With so few companies to produce aircraft, armored vehicles, missile systems, and nuclear weapons, the Pentagon has ever more limited leverage in keeping them from overcharging for products that don’t perform as advertised. The Big Five alone routinely split more than $150 billion in Pentagon contracts annually, or nearly 20% of the total Pentagon budget. Altogether, more than half of the department’s annual spending goes to contractors large and small.

In Eisenhower’s day, the Soviet Union, then this country’s major adversary, was used to justify an ever larger, ever more permanent arms establishment. Today’s “pacing threat,” as the Pentagon calls it, is China, a country with a far larger population, a far more robust economy, and a far more developed technical sector than the Soviet Union ever had. But unlike the USSR, China’s primary challenge to the United States is economic, not military.

Yet, as Dan Grazier noted in a December 2022 report for the Project on Government Oversight, Washington’s ever more intense focus on China has been accompanied by significant military threat inflation. While China hawks in Washington wring their hands about that country having more naval vessels than America, Grazier points out that our Navy has far more firepower. Similarly, the active American nuclear weapons stockpile is roughly nine times as large as China’s and the Pentagon budget three times what Beijing spends on its military, according to the latest figures from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

But for Pentagon contractors, Washington’s ever more intense focus on the prospect of war with China has one overriding benefit: it’s fabulous for business. The threat of China’s military, real or imagined, continues to be used to justify significant increases in military spending, especially on the next generation of high-tech systems ranging from hypersonic missiles to robotic weapons and artificial intelligence. The history of such potentially dysfunctional high-tech systems, from President Ronald Reagan’s “Star Wars” missile defense system to the F-35, does not bode well, however, for the cost or performance of emerging military technologies.

No matter, count on one thing: tens, if not hundreds, of billions of dollars will undoubtedly go into developing them anyway. And remember that they are dangerous and not just to any enemy. As Michael Klare pointed out in an Arms Control Association report: “AI-enabled systems may fail in unpredictable ways, causing unintended human slaughter or an uncontrolled escalation crisis.”

Arsenal of Influence

Despite a seemingly never–ending list of overpriced, underperforming weapons systems developed for a Pentagon that’s the only federal agency never to pass an audit, the MIC has an arsenal of influence propelling it ever closer to a trillion-dollar annual budget. In short, it’s bilking more money from taxpayers than ever before and just about everyone – from lobbyists galore to countless political campaigns, think tanks beyond number to Hollywood – is in on it.

And keep in mind that the dominance of a handful of mega-firms in weapons production means that each of the top players has more money to spread around in lobbying and campaign contributions. They also have more facilities and employees to point to, often in politically key states, when persuading members of Congress to vote for – Yes!– even more money for their weaponry of choice.

The arms industry as a whole has donated more than $83 million to political candidates in the past two election cycles, with Lockheed Martin leading the pack with $9.1 million in contributions, followed by Raytheon at $8 million, and Northrop Grumman at $7.7 million. Those funds, you won’t be surprised to learn, are heavily concentrated among members of the House and Senate armed services committees and defense appropriations subcommittees. For example, as Taylor Giorno of OpenSecrets, a group that tracks campaign and lobbying expenditures, has found, “The 58 members of the House Armed Services Committee reported receiving an average of $79,588 from the defense sector during the 2022 election cycle, three times the average $26,213 other representatives reported through the same period.”

Lobbying expenditures by all the denizens of the MIC are even higher – more than $247 million in the last two election cycles. Such funds are used to employ 820 lobbyists, or more than one for every member of Congress. And mind you, more than two-thirds of those lobbyists had swirled through Washington’s infamous revolving door from jobs at the Pentagon or in Congress to lobby for the arms industry. Their contacts in government and knowledge of arcane acquisition procedures help ensure that the money keeps flowing for more guns, tanks, ships and missiles. Just last month, the office of Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) reported that nearly 700 former high-ranking government officials, including former generals and admirals, now work for defense contractors. While a few of them are corporate board members or highly paid executives, 91% of them became Pentagon lobbyists, according to the report.

And that feverishly spinning revolving door provides current members of Congress, their staff, and Pentagon personnel with a powerful incentive to play nice with those giant contractors while still in their government roles. After all, a lucrative lobbying career awaits once they leave government service.

Nor is it just K Street lobbying jobs those weapons-making corporations are offering. They’re also spreading jobs to nearly every Main Street in America. The poster child for such jobs as a selling point for an otherwise questionable weapons system is Lockheed Martin’s F-35. It may never be fully ready for combat thanks to countless design flaws, including more than 800 unresolved defects detected by the Pentagon’s independent testing office. But the company insists that its program produces no less than 298,000 jobs in 48 states, even if the actual total is less than half of that.

In reality – though you’d never know this in today’s Washington – the weapons sector is a declining industry when it comes to job creation, even if it does absorb near-record levels of government funding. According to statistics gathered by the National Defense Industrial Association, there are currently one million direct jobs in arms manufacturing compared to 3.2 million in the 1980s.

Outsourcing, automation, and the production of fewer units of more complex systems have skewed the workforce toward better-paying engineering jobs and away from production work, a shift that has come at a high price. The vacuuming up of engineering and scientific talent by weapons makers means fewer skilled people are available to address urgent problems like public health and the climate crisis. Meanwhile, it’s estimated that spending on education, green energy, health care, or infrastructure could produce 40% to 100% more jobs than Pentagon spending does.

Shaping the Elite Narrative: The Military-Industrial Complex and Think Tanks

One of the MIC’s most powerful tools is its ability to shape elite discussions on national security issues by funding foreign policy think tanks, along with affiliated analysts who are all too often the experts of choice when it comes to media coverage on issues of war and peace. A forthcoming Quincy Institute brief reveals that more than 75% of the top foreign-policy think tanks in the United States are at least partially funded by defense contractors. Some, like the Center for a New American Security and the Center for Strategic and International Studies, receive millions of dollars every year from such contractors and then publish articles and reports that are largely supportive of defense-industry funding.

Some such think tanks even offer support for weapons made by their funders without disclosing those glaring conflicts of interest. For example, an American Enterprise Institute (AEI) scholar’s critique of this year’s near-historically high Pentagon budget request, which, she claimed, was “well below inflation,” also included support for increased funding for a number of weapons systems like the Long Range Anti-Ship Missile, the Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile, the B-21 bomber, and the Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile.

What’s not mentioned in the piece? The companies that build those weapons, Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman, have been AEI funders. Although that institute is a “dark money” think tank that doesn’t publicly disclose its funders, at an event last year, a staffer let slip that the organization receives money from both of those contractors.

Unfortunately, mainstream media outlets disproportionately rely on commentary from experts at just such think tanks. That forthcoming Quincy Institute report, for example, found that they were more than four times as likely as those without MIC funding to be cited in New York Times, Washington Post, and Wall Street Journal articles about the Ukraine War. In short, when you see a think-tank expert quoted on questions of war and peace, odds are his or her employer receives money from the war machine.

What’s more, such think tanks have their own version of a feverishly spinning revolving door, earning them the moniker “holding tanks” for future government officials. The Center for a New American Security, for example, receives millions of dollars from defense contractors and the Pentagon every year and has boasted that a number of its experts and alumni joined the Biden administration, including high-ranking political appointees at the Department of Defense and the Central Intelligence Agency.

Shaping the Public Narrative: The Military-Entertainment Complex

Top Gun: Maverick was a certified blockbuster, wowing audiences that ultimately gave that action film an astounding 99% score on Rotten Tomatoes – and such popular acclaim helped earn the movie a Best Picture Oscar nomination. It was also a resounding success for the Pentagon, which worked closely with the filmmakers and provided, “equipment – including jets and aircraft carriers – personnel and technical expertise,” and even had the opportunity to make script revisions, according to the Washington Post. Defense contractors were similarly a pivotal part of that movie’s success. In fact, the CEO of Lockheed Martin boasted that his firm “partnered with Top Gun’s producers to bring cutting-edge, future forward technology to the big screen.”

While Top Gun: Maverick might have been the most successful recent product of the military-entertainment complex, it’s just the latest installment in a long history of Hollywood spreading military propaganda. “The Pentagon and the Central Intelligence Agency have exercised direct editorial control over more than 2,500 films and television shows,” according to Professor Roger Stahl, who researches propaganda and state violence at the University of Georgia.

“The result is an entertainment culture rigged to produce relatively few antiwar movies and dozens of blockbusters that glorify the military,” explained journalist David Sirota, who has repeatedly called attention to the perils of the military-entertainment complex. “And save for filmmakers’ obligatory thank you to the Pentagon in the credits,” argued Sirota, “audiences are rarely aware that they may be watching government-subsidized propaganda.”

What Next for the MIC?

More than 60 years after Eisenhower identified the problem and gave it a name, the military-industrial complex continues to use its unprecedented influence to corrupt budget and policy processes, starve funding for non-military solutions to security problems, and ensure that war is the ever more likely “solution” to this country’s problems. The question is: What can be done to reduce its power over our lives, our livelihoods, and ultimately, the future of the planet?

Countering the modern-day military-industrial complex would mean dislodging each of the major pillars undergirding its power and influence. That would involve campaign-finance reform; curbing the revolving door between the weapons industry and government; shedding more light on its funding of political campaigns, think tanks, and Hollywood; and prioritizing investments in the jobs of the future in green technology and public health instead of piling up ever more weapons systems. Most important of all, perhaps, a broad-based public education campaign is needed to promote more realistic views of the challenge posed by China and to counter the current climate of fear that serves the interests of the Pentagon and the giant weapons contractors at the expense of the safety and security of the rest of us.

That, of course, would be no small undertaking, but the alternative – an ever-spiraling arms race that could spark a world-ending conflict or prevent us from addressing existential threats like climate change and pandemics – is simply unacceptable.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Books, John Feffer’s new dystopian novel, Songlands (the final one in his Splinterlands series), Beverly Gologorsky’s novel Every Body Has a Story, and Tom Engelhardt’s A Nation Unmade by War, as well as Alfred McCoy’s In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power, John Dower’s The Violent American Century: War and Terror Since World War II, and Ann Jones’s They Were Soldiers: How the Wounded Return from America’s Wars: The Untold Story.

Ben Freeman, a TomDispatch regular, is a research fellow at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft and the author of a forthcoming report on Pentagon contractor funding of think tanks.

William D. Hartung, a TomDispatch regular, is a senior research fellow at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft and the author of Prophets of War: Lockheed Martin and the Making of the Military-Industrial Complex.

Copyright 2023 William D. Hartung and Ben Freeman

May 10, 2023

Elizabeth Vos: Using Poison in Ukraine’s Depleted Hope of Victory

By Elizabeth Vos, Consortium News, 5/2/23

Depleted uranium shells have been sent to Ukraine, as confirmed by U.K. Armed Forces Minister James Heappey last week. Britain announced last month that it would send the munitions for use with Challenger 2 tanks, a move that immediately escalated nuclear tensions with Russia, with President Vladimir Putin threatening to place tactical nuclear weapons in Belarus just days later.

The U.K. move comes amid indications that Kiev is increasingly desperate, to the point of being willing to risk scorching the earth it is fighting for.

Over the last few months documents emerging as part of the so-called Pentagon leak allegedly posted online by U.S. National Guardsman Jack Teixera have shown Ukrainian forces are faring far worsethan previously reported by corporate media. As reported by Consortium News, the leaked documents “show the long-planned Ukrainian offensive will fail miserably.”

That the conflict is not going well for Ukraine came as little surprise to those who had been following the story outside of the legacy press echo chamber. However, Britain’s decision to send depleted uranium rounds to Ukraine represents more than a dangerous escalation in the West’s proxy war with a nuclear-armed power.

It is an example of Ukraine’s willingness to target the ethnic Russian population in eastern Ukraine and poison the land it is attempting to retain. Depleted uranium will have effects not only on Russian fighters but also on the civilian population for years to come.

Ukrainian troops in the Donbass region, March 2015. (OSCE Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons)

Radio host Randy Credico, who visited Donbass, recently told Consortium News that residents of that region already live in daily fear of U.S.-made missiles used by Ukraine to target civilians and the emergency services that come to help them: now they are to face the additional prospect of depleted uranium shells, which would not simply kill civilians now, but has the potential to poison future generations.

Russia intervened in Ukraine after eight years of war by Kiev against the ethnic Russians in the east who declared independence from Ukraine after the U.S.-backed 2014 coup.

The U.S. and British corporate media appear to dismiss concerns of Russian nuclear escalation in response to the use of depleted uranium rounds, and the official line in the West is that such weapons represent a low environmental risk.

The Sordid History of Its Use

U.S. sailors checking rounds of depleted uranium aboard the battleship USS Missouri in 1987. (Public domain, Wikimedia Commons)

However, there are compelling reasons to question the official stance. Depleted uranium rounds were used by U.S. forces in both Iraq wars, as well as in the Balkans in the 1990s.

Depleted uranium munitions are heavier than lead and are typically used to pierce the armor of tanks. On impact the metal shears, burns and vaporizes. This process produces toxic radioactive dust. A 2001 report focusing on the health impacts of depleted uranium on U.S. veterans of the Gulf War published by The Nation explains that:

“D.U. is highly toxic and, according to the Encyclopedia of Occupational Health and Safety, can cause lung cancer, bone cancer and kidney disease… Scientists point out that D.U. becomes much more dangerous when it burns. When fired, it combusts on impact. As much as 70 percent of the material is released as a radioactive and highly toxic dust that can be inhaled or ingested and then trapped in the lungs or kidneys. ‘This is when it becomes most dangerous,” says Arjun Makhijani, president of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research. “It becomes a powder in the air that can irradiate you.”

Sites identified by U.N. Environmental Programme as targets for ordinance containing depleted uranium during NATO 1999 bombing of former Yugoslavia. (UNEP 2001 report “Depleted Uranium in Kosovo, Post-Conflict Environmental Assessment)

A 1999 report by The Guardian related the sentiments of scientists speaking in regards to bombing Kosovo with depleted uranium: “One single particle of depleted uranium lodged in the lymph node can devastate the entire immune system.”

Former U.N. weapons inspector Scott Ritter commented on the news of depleted uranium rounds being sent to Ukraine by citing increases in leukemia where it had previously been used in Kosovo as well as increases in birth defects and cancer in Iraq following the wars there.

He argues that the U.S. suppresses the health effects of depleted uranium “because we don’t want to take ownership for what we have done.”

In John Pilger’s film documenting Iraq after the first Gulf War, Paying the Price: Killing the Children of Iraq, he spoke with doctors in Basra where they reported a 10-fold increase in cancer deaths. Pilger also spoke with an Iraqi pediatrician who described an influx of congenital deformities never seen before the war.

In the case of the second Iraq War, the most striking reported effects of depleted uranium and other toxic substances were seen in Fallujah, where U.S. forces bombed mercilessly in 2004.

The rise in birth defects in Iraq have been called “catastrophic,” and The Guardian went so far as to publish a piece in 2014 that accused the World Health Organization of covering up the “nuclear nightmare” left behind in Fallujah by the U.S. and U.K.

U.S. soldiers dispose of a simulated depleted uranium round during training IN 2018 on the island of Oahu in Hawaii. (U.S. Army National Gurd/Rory Featherston)

Others have compared the city’s health crisis with that following the U.S. nuclear attack on Hiroshima.

The specific role of depleted uranium rounds in the sharply increased rate of cancer and serious birth defects remains controversial, but the accounts of doctors on the ground in Fallujah who have documented such birth defects, cancers, and other health problems are staggering.

Is this the future faced by generations of ethnic Russians in Ukraine?

When Ukraine is already set to lose, if slowly, on the battlefield, what is to be gained by taking out a few more Russian tanks if it permanently renders the land a danger to its inhabitants, permeated with toxic dust particles of radioactive heavy metal?

How can this decision be viewed as anything but a spiteful admission that that land is being lost, and that “salting” it is a final act of malice against ethnic Russians in Donbass?

The use of depleted uranium munitions in Ukraine amounts to a last-gasp of desperation and an attempt to contaminate territory Kiev knows it will not regain, for such weapons would not be supplied by Britain and used by Ukraine on land they were confident they would recapture.

Elizabeth Vos is a freelance journalist and contributor to Consortium News . She co-hosts CN Live!

May 9, 2023

Ben Aris: A blueprint for a Ukrainian peace deal

By Ben Aris, Intellinews, 4/28/23

Talk of peace plans is back in the news after China’s President Xi Jinping and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy had a “long and meaningful” telephone call on April 26.

But a workable formula still seems a long way off. The Russian and Ukrainian starting positions are so far apart it seems impossible to close them. The Kremlin is insisting that not only does it keep all the land it has captured but that Kyiv recognises the four Ukrainian regions Moscow annexed in September as Russian. Kyiv says that talks can’t start until all Russian troops have left the country and returned to the 1991 borders. Obviously these two positions are irreconcilable. There is no common ground on which to start talks.

China entered the diplomatic fray on the anniversary of the start of the war with a 12-point peace plan proposal and is trying to position itself as a neutral arbitrator. And it is true that of all the great powers, China is best positioned to bring a deal about. Xi is as close to President Vladimir Putin as a foreign leader can get and, while Beijing’s relations with Washington are less than good, they are at least, for the meantime, still cordial. Moreover, with his trip to Moscow to see Putin in March, Xi has drawn up a chair at the top table of international diplomacy. China’s position on the war can no longer be ignored.

Having said all that, the peace deal that China has proposed is also a non-starter. While the text was full of nice sentiments like “respect for territorial sovereignty”, “an end to hostilities”, and the “prevention of the use of nuclear weapons” the practical part, where the lines of demarcation should be and who controls what territory, are no better than the Russian demands. China’s plan would concede the Donbas, the land bridge and Crimea to Russia and turn the whole of eastern Ukraine into a demilitarised zone.

Nevertheless, it’s a starting gambit that no one expects to be accepted and the goal is to start talks, not draw up an ideal solution at the first pass. What is encouraging is that Xi seems to be genuinely interested in seeing an end to the war.

So what would a possible deal look like? Ukraine and Russia came within a whisker of doing a deal in May, until it was reported that UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson flew into Kyiv and killed it off, saying that the West would not support any peace deal with Russia.

However, during the April process real progress was made and several points were agreed between the Russian and Ukrainian sides that can be built on. The points in a deal would have to deal with the problems listed below. And before proceeding further it should be acknowledged that the atmosphere is currently so toxic it would be a miracle if many of these suggestions could be made to work.

Nato: The first and easiest point to agree on is that Ukraine should give up its Nato ambitions and return to a position of neutrality that was enshrined in its constitution until 2014, when former President Petro Poroshenko changed it and made Nato membership an national ambition.

The Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued an eight-point list of demands in December 2021 that in effect only had one demand that really mattered: Ukraine be permanently barred from joining Nato by a “legally binding guarantee” to that effect.

The Ukrainian negotiators conceded the point and suggested that instead Ukraine sign bi-lateral security agreements with all its Western partners – something the Russian delegates accepted.

The US refused to accept Russia’s insistence on locking Ukraine out of Nato in the January round of diplomacy just before the war, but the point here is to ensure Ukraine’s security, not for it to join Nato per se – something that the US seems more keen on that it cares to admit.

Russian security deal: Any security deal for Ukraine needs a similar security deal for Russia if stability is to return to Europe. The problem with Nato, as far as Russia is concerned, is that it is excluded from the treaty, which was specifically set up to protect Europe from the Soviet Union. The Kremlin argues that the Soviet Union no longer exists and in 2008 proposed Europe sign off on a new post-Cold War pan-European security pact that this time includes Russia and takes in the new realities – a proposal that was rejected out of hand.

For security deals with Ukraine to work, this concern of Russia’s over its security also needs to be addressed, and the idea of a new pan-European security pact needs to be revived. However, as Russia has already drawn up a template, this should be relatively easy, as there is plenty of common ground.

At the same time, once peace arrives, the arms control talks that were kicked off with the signing of a new START treaty in January 2021 should be revived and all the lapsed Cold War missile and security agreements put back in place.

Donbas and the land bridge: The question of territory will be much more difficult, as obviously Russia will not want to give up any territory it has captured without being forced to.

Of all the territory that Russia now holds in the southeast, it has the least claim to the land bridge, which was occupied at great military cost, including the destruction of Mariupol, the main city in the region. The referenda held last September as part of the annexation were an even more obviously sham than that held in Crimea in 2014. As part of a lasting deal – one that not only ends this war, but prevents the next one – the land bridge should be returned to Ukraine.

The large numbers of Donbas residents holding Russian passports – some 600,000 people – makes the question of the Donbas region much more complicated to solve. The situation is made even more complicated by the share of the locals that genuinely want to join Russia. Over the last eight years in an underreported story, the Ukraine army has been shelling the towns in the Donbas, including residential areas with civilian casualties, creating local animosity amongst a proportion of the local population.

The Russian constitution obliges the government to protect Russian citizens wherever they are, which has been used as a justification for launching the “special military operation” but is thin grounds for the occupation of the territory, and is no grounds for annexation.

During the April peace talks Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy offered to meet with Putin personally to negotiate on the status of the Donbas. One option on the table was to grant the region some sort of “autonomous” status, but within Ukraine. That would hand political control to Moscow that would clearly back the local regimes, as it has done in South Ossetia and Abkhazia that were hived off Georgia. The Kremlin signalled it was open to this conversation, but it is not clear if it would accept it.

Another choice would be to create a new country, “Donbas Republic”, (without the “the” as the definite article is used for regions but not countries), but for the local economy to be viable it would need to keep Mariupol as a port and access to the sea. It’s unlikely either side would agree to this as, there is no precedent for a country based on the Donbas region.

The most likely outcome is a stalemate where the issue of the Donbas is kicked down the road to be solved “later” by some form of “referendum” or commission and turns into a frozen conflict, similar to northern Cyprus.

Crimea: Russia will never agree to give up Crimea under any circumstances. While the Kremlin can invent some excuses to lay claim to the Donbas, Russians believe Crimea is part of Russia and has been since it was annexed by Catherine the Great in the 16th century. Even the Ukrainians saw it as “Russian,” at least in a cultural sense, according to Gallup polls taken before the war. However, one fix here would be if the Kremlin agreed to pay for it, like the Tsar’s sale of Alaska to the US.

An obvious price would be $300bn – three times more than the value of the entire pre-war economy – which would solve the problem of how to expropriate the frozen Central Bank of Russia (CBR) money that can’t be touched legally thanks to Europe’s strong property rights. There is a chance the Kremlin will agree to this, as it has surely already written that money off anyway. At least another Alaska deal would bring some sort of closure for everyone involved.

Although an ugly solution, it has the benefit of reducing tensions by putting some legitimacy on Russia’s occupation and provides Ukraine some tangible compensation for its loss. Many Ukrainians would accept the deal as a compromise that allows them to rebuild their ruined country, and that would contribute to avoiding a new war in the future. It would provide the ready cash Ukraine needs to rebuild, which is very unlikely to be provided by its Western partners, private investors or multilateral development banks.

Free trade agreements: The final and key part of a peace plan that will last is to sign free trade agreements (FTAs) between the EU, Ukraine and Russia.

Ukraine was invited to join the EU last July, but in reality it has no chance of doing so for at least a decade, as the EU is not ready for Ukraine mainly because of the size of Ukraine’s agricultural sector. That was amply illustrated by the recent bans on Ukrainian wheat to Central Europe, which has crashed the local grain markets.

A new FTA, or an expansion of the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) already in place, would allow the EU to regulate imports from Ukraine, but also let Ukraine trade its way out of its current economic abyss and so negate, or even eradicate, its dependence on IMF programmes or donor loans.

When Rome finally destroyed Carthage for the first time, the city quickly bounced back by energetically trading with Rome and was able to repay all its reparations to Rome, early and with interest. The fact that Rome destroyed Carthage a second time, and much more thoroughly, only highlights the need to think long term and build a peace that allows for growth and recovery as well as simply stopping the shooting.

Import duties on Ukrainian goods to the EU have been temporarily suspended, but the current DCFTA system of quotas is so small they are used up in the first weeks of every year.

An FTA between Russia and Ukraine would also reopen Ukraine’s eastern border to trade, which would only add to its income. Moreover, entrepreneurial Russians, who already know the market well, would pour into Ukraine, and this is the fastest route to real foreign direct investment (FDI), unsavoury as that may sound.

And if there is a FTA between Ukraine and Russia, there needs to be one between Russia and the EU too, as open borders between Ukraine and EU as well as Ukraine and Russia will simply push Russian goods through Ukraine into the EU and vice versa. The Russians will be as keen to regulate trade with Ukraine crossing its border as the EU. Indeed, it was the EU’s refusal to include Russia in Ukraine’s DCFTA talks that caused the beginning of the worsening of relations between all involved.

The benefits of a new comprehensive trade deal between Russia and the EU would also bring huge new economic benefits for the EU, returning all the cheap and copious raw materials and energy, as well as access to the giant Russian consumer market – increased in size by a third by the addition of the Ukrainian market.

All of this may seem pie in the sky because of the political considerations, but a deal along these lines is inevitable thanks to the proximity of the two countries. As I wrote in another blog, [in] the geography of diplomacy, proximity matters and the geography in this case says Ukraine and Russia should be close commercial partners, even if their ideologies are currently at loggerheads. For example, despite the fact that the two have been at war for more than a year, Russian gas is still transiting Ukraine and the Russian state-owned national gas company Gazprom is still paying hundreds of millions of dollars in transit fee payments to its Ukrainian counterpart Naftogaz, scrupulously sticking to the terms of the 2019 contract. Bottom line: prosperity breeds peace and poverty leads to hate and violence.

May 8, 2023

Gordon Hahn: Can Zelenskiy’s Ukraine End the War?

By Gordon Hahn, Russian and Eurasian Studies Blog, 4/27/23

A series of European developments have demonstrated recently the accelerating dissipation of American hegemony at the hands of the Sino-Russian bandwagon seeking to organize the world’s ‘Rest’ away from the West and the US hegemonic system. Now the leaking has turned into a flood. Chinese president Xi has lassoed Ukrainian President Volodomyr Zelenskiy for negotiations to end or at least stop the NATO-Russian Ukraine war despite apparent US opposition to any such talks or even a ceasefire as stated by numerous US officials in recent weeks. Ukraine’s defection from the American NATO-Ukraine project-turned Russian regime change by proxy war puts Washington in a tight spot and might produce drastic measures.

As I noted recently, a series of European leaders were preparing for trips to the Forbidden City to consult on economic and political issues with Chinese officials. Brazil’s President added the weight of South America’s most powerful state when he met with Xi and called for for a Ukraine peace conference to be led by China. But it turned out that the most important pilgrimage to Beijing was that of French President Emmanuel Macron. The leader of one of NATO’s and the EU’s key members and contender for leadership in Europe announced what many conservative dissidents from across Europe have been stating for years. After meeting with XI, Macron noted in an interview on his flight back to Paris that Europe should avoid “vassal” and “follower” status in relation with the US and instead seek “strategic autonomy” as a “third pole” in the international system along with the US and China. Such a development would obviously represent the removal of the key building block in the American or Western pole in the international system. Washington and Brussels, which had enjoyed hegemony since the Cold War’s end, would see the end of the unipolar system they sat atop of and begin to vie for Beijing’s favors, even as the last protects the hated Russians.

Now comes Zelenskiy’s call to XI and the latter’s acknowledgement that they discussed involving Ukraine in pursuit of a peace process with Russia and the announcement that Beijing is appointing a special envoy to Kiev to coordinate preparation for talks. The fact that Zelesnkiy initiated the contact with Xi and that it came as Ukraine’s hold on the pivotal Donbass transport hub of Bakhmut was being completely broken suggests that Zelenskiy, understanding that Western aide will be too little too late to prevent a Russian march to the Dnepr River which will force the government’s withdrawal from Kiev, sees the handwriting of Ukraine’s total and utter defeat is on the wall. This is a wise move but what that may be too late for him, the Maidan regime, and even Kiev’s sovereignty over Ukrainian territory–the latter being under threat not just from Russia but also by dint of its dire circumstances by Poland and even the US and NATO.

I recently noted Seymour Hersh’s reports that CIA Director William Burns while in Kiev earlier this month handed Zelenskiy a list of 35 Ukrainian generals who were involved in actions skimming $400 million of Western assistance to Ukraine since the war began. Burns reportedly told Zelenskiy that he, the Ukrainian president, should have been at the top of the list. Zelenskiy was thus forced to fire the most ambitious military corruptionaires on the list. This suggests that Washington has serious hold over Zelenskiy and can control Ukraine’s war policies, putting aside Kiev’s full dependence on Western financing for its state budget. But not only does this mean that Washington and Brussels can now manipulate Zelenskiy even more than they had prior to presenting their intelligence acquired from eavesdropping on Kiev’s internal communications and that more than ever Ukraine is a de facto NATO member and a Western satellite state fully reliant on the alliance, especially Washington, for its survival but that Washington can deploy intelligence to raise the tensions in Ukrainian civilian-military relations and those specifically between Zelenskiy and his generals among others. The compromising materials gathered on Zelenskiy could be deployed in future to peak the temperature and then recruit generals, in particular chief of the Ukrainian General Staff Viktor Zalyuzhniy, ultranationalists, neofascists, or others to mount a coup against and/or an assassination of Zelenskiy for any betrayal of the interests of US President Joe Biden, NATO, and other core Western interests by making peace with Putin under Chinese auspices. This would not only out an end to the Western hopes of parlaying the NATO-Russian Ukraine war into the demise of Putin and his regime but would place Beijing above the ‘indispensable nation’ as the chief arbiter of international politics. In Washington and Brussels avoiding such an outcome is valued far more highly than Zelenskiy’s life and the survival of Ukraine.

It is not exactly clear what connection there is in Zelenskiy’s mind between his reaching out to Beijing…with previous pronouncements made by Zelenskiy and Polish President Andrzej Duda about the ‘dissolution’ of borders between Poland and Ukraine and what I suggested many months ago was the real possibility of Polish or NATO forces [going] into Western Ukraine to black any Russian advance beyond the Dnepr. However, it is clear that such a plan can be carried out without Zelenskiy at Kiev’s helm. In sum, if there is no US imprimatur on Zelenskiy’s contacts with Beijing and feelers for possible talks with the Kremlin, then Zelenskiy has put himself in a very precarious position. Whether its Nord Stream, Trump, his son Hunter, or simply approximation of the truth, Biden has shown he is no less ruthless than any other tyrant. Biden’s audacity and that of those who help determine his policies in Washington, Brussels, Davos, and elsewhere will only be emboldened to take desperate actions, given the rapidly deteriorating situation on the Ukrainian front as the Russian winter offensive slowly and methodically gains steam and now encircling troops in Bakhmut, Avdeevsk, and elsewhere, the beginning of the 2024 presidential campaign, and the high stakes of the presidential and congressional election’s outcome for Biden, his family, patrons, and allies.

May 7, 2023

Lee Fang: How The FBI Helps Ukrainian Intelligence Hunt ‘Disinformation’ On Social Media

Photo by Markus Winkler on Pexels.com

Photo by Markus Winkler on Pexels.comBy Lee Fang, Website, 4/28/23

Lee Fang is a journalist with a longstanding interest in how public policy is influenced by organized interest groups and money. He has previously written for The Intercept and The Nation.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation pressures Facebook to take down alleged Russian “disinformation” at the behest of Ukrainian intelligence, according to a senior Ukrainian official who corresponds regularly with the FBI. The same official said that Ukrainian authorities define “disinformation” broadly, flagging many social media accounts and posts that he suggested may simply contradict the Ukrainian government’s narrative.

“Once we have a trace or evidence of disinformation campaigns via Facebook or other resources that are from the U.S., we pass this information to the FBI, along with writing directly to Facebook,” said llia Vitiuk, head of the Department of Cyber Information Security in the Security Service of Ukraine.

“We asked FBI for support to help us with Meta, to help us with others, and sometimes we get good results with that,” noted Vitiuk. “We say, ‘Okay, this was the person who was probably Russia’s influence.'”

Vitiuk, in an interview, said that he is a proponent of free speech and understands concerns around social media censorship. But he also admitted that he and his colleagues take a deliberately expansive view of what counts as “Russian disinformation.”

“When people ask me, ‘How do you differentiate whether it is fake or true?’ Indeed it is very difficult in such an informational flow,” said Vitiuk. “I say, ‘Everything that is against our country, consider it a fake, even if it’s not.’ Right now, for our victory, it is important to have that kind of understanding, not to be fooled.”

In recent weeks, Vitiuk said, Russian forces have used various forms of disinformation to manufacture fake tension between President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and Valerii Zaluzhnyi, the four-star general who serves as commander-in-chief of Ukraine’s military.

Indeed, recent reports have focused on the relationship between the two Ukrainian leaders. The German newspaper Bild reported that Zelenskyy and Zaluzhnyi had argued regarding tactics deployed in the battle over Bakhmut. Vitiuk said that any notion of conflict between Zelenskyy and his military chief, however, is false.

“They try to create problems in Ukraine, and they try to sow the seeds of misunderstanding between Ukraine and our partners that support us,” said Vitiuk.

Vitiuk, a senior official in Ukraine’s domestic intelligence agency, spoke to me this week at the RSA Convention in San Francisco, an annual gathering that brings together a collection of cyber security firms, law enforcement, and technology giants.

Full article here.

May 6, 2023

Taking the Capitalist Road Was the Wrong Choice For Ukraine – My Interview with Expert Renfrey Clarke

By Natylie Baldwin, Covert Action Magazine, 5/5/23

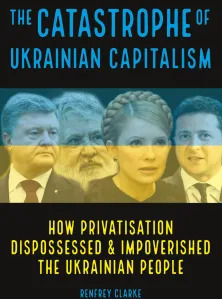

Renfrey Clarke is an Australian journalist. Throughout the 1990s he reported from Moscow for Green Left Weekly of Sydney. This past year, he published The Catastrophe of Ukrainian Capitalism: How Privatisation Dispossessed & Impoverished the Ukrainian People with Resistance Books.

In April, I had an email exchange with Clarke. Below is the transcript.

Natylie Baldwin: You point out in the beginning of your book that Ukraine’s economy had significantly declined by 2018 from its position at the end of the Soviet era in 1990. Can you explain what Ukraine’s prospects looked like in 1990? And what did they look like just prior to Russia’s invasion?

Renfrey Clarke: In researching this book I found a 1992 Deutsche Bank study arguing that, of all the countries into which the USSR had just been divided, it was Ukraine that had the best prospects for success. To most Western observers at the time, that would have seemed indisputable.

Ukraine had been one of the most industrially developed parts of the Soviet Union. It was among the key centres of Soviet metallurgy, of the space industry and of aircraft production. It had some of the world’s richest farmland, and its population was well-educated even by Western European standards.

Add in privatisation and the free market, the assumption went, and within a few years Ukraine would be an economic powerhouse, its population enjoying first-world levels of prosperity.

Fast-forward to 2021, the last year before Russia’s “Special Military Operation,” and the picture in Ukraine was fundamentally different. The country had been drastically de-developed, with large, advanced industries (aerospace, car manufacturing, shipbuilding) essentially shut down.

World Bank figures show that in constant dollars, Ukraine’s 2021 Gross Domestic Product was down from the 1990 level by 38 per cent. If we use the most charitable measure, per capita GDP at Purchasing Price Parity, the decline was still 21 per cent. That last figure compares with a corresponding increase for the world as a whole of 75 per cent.

To make some specific international comparisons, in 2021 the per capita GDP of Ukraine was roughly equal to the figures for Paraguay, Guatemala and Indonesia.

What went wrong? Western analysts have tended to focus on the effects of holdovers from the Soviet era, and in more recent times, on the impacts of Russian policies and actions. My book takes these factors up, but it’s obvious to me that much deeper issues are involved.

In my view, the ultimate reasons for Ukraine’s catastrophe lie in the capitalist system itself, and especially, in the economic roles and functions that the “centre” of the developed capitalist world imposes on the system’s less-developed periphery.

Quite simply, for Ukraine to take the “capitalist road” was the wrong choice.

NB: It seems as though Ukraine went through a process similar to that in Russia in the 1990s, when a group of oligarchs emerged to control much of the country’s wealth and assets. Can you describe how that process occurred?

RC: As a social layer, the oligarchy in both Ukraine and Russia has its origins in the Soviet society of the later perestroika period, from about 1988. In my view, the oligarchy arose from the fusion of three more or less distinct currents that by the final perestroika years had all managed to accumulate significant private capital hoards. These currents were senior executives of large state firms; well-placed state figures, including politicians, bureaucrats, judges, and prosecutors; and lastly, the criminal underworld, the mafia.

A 1988 Law on Cooperatives allowed individuals to form and run small private firms. Many structures of this kind, only nominally cooperatives, were promptly set up by top executives of large state enterprises, who used them to stow funds that had been bled off illicitly from enterprise finances. By the time Ukraine became independent in 1991, many senior figures in state firms were substantial private capitalists as well.

The new owners of capital needed politicians to make laws in their favour, and bureaucrats to make administrative decisions that were to their advantage. The capitalists also needed judges to rule in their favour when there were disputes, and prosecutors to turn a blind eye when, as happened routinely, the entrepreneurs functioned outside the law. To perform all these services, the politicians and officials charged bribes, which allowed them to amass their own capital and, in many cases, to found their own businesses.

Finally, there were the criminal networks that had always operated within Soviet society, but that now found their prospects multiplied. In the last years of the USSR, the rule of law became weak or non-existent. This created huge opportunities not just for theft and fraud, but also for criminal stand-over men. If you were a business operator and needed a contract enforced, the way you did it was by hiring a group of “young men with thick necks.”

To stay in business, private firms needed their “roof,” the protection racketeers who would defend them against rival shake-down artists—for an outsized share of the enterprise profits. At times the “roof” would be provided by the police themselves, for an appropriate payment.

This criminal activity produced nothing, and stifled productive investment. But it was enormously lucrative, and gave a start to more than a few post-Soviet business empires. The steel magnate Rinat Akhmetov, for many years Ukraine’s richest oligarch, was a miner’s son who began his career as a lieutenant to a Donetsk crime boss.

Within a few years from the late 1980s, the various streams of corrupt and criminal activity began merging into oligarchic clans centred on particular cities and economic sectors. When state enterprises began to be privatised in the 1990s, it was these clans that generally wound up with the assets.

I should say something about the business culture that arose from the last Soviet years, and that in Ukraine today remains sharply different from anything in the West. Few of the new business chiefs knew much about how capitalism was supposed to work, and the lessons in the business-school texts were mostly useless in any case.

The way you got rich was by paying bribes to tap into state revenues, or by cornering and liquidating value that had been created in the Soviet past. Asset ownership was exceedingly insecure—you never knew when you’d turn up at your office to find it full of the armed security guards of a business rival, who’d bribed a judge to permit a takeover. In these circumstances, productive investment was irrational behaviour…

Read full interview here.

May 5, 2023

Russian Prime Minister Mishustin’s Remarks at Strategic Session on Improving Living Standards

Russian government website, 4/25/23

Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin’s opening remarks:

Good afternoon, colleagues.

Today we will discuss one of the President’s priority goals – to improve the living standards of our citizens.

Fulfilling the social obligations to our people is our direct responsibility. This effort should not be influenced by any external threat or risk, including sanctions from unfriendly states.

We are working in several key areas in this effort – reducing poverty, providing targeted support to needy families with children, and increasing real salaries and incomes. We are also improving the wellbeing of our pensioners and other socially vulnerable citizens.

As the President noted, there should be no one that can barely make ends meet if they are employed. Therefore, the Government continues supporting the incomes of our citizens. Under the President’s instructions, we have raised the subsistence level twice in a special procedure – starting on June 1 last year and again the beginning of January of this year. The overall increase was over 13.5 percent. By doing this, we have maintained the real incomes of 15 million people.

We are also consistently increasing the minimum wage at a rate that is higher than inflation. It has increased since the start of this year and is now 16,242 roubles. Moreover, on January 1 of next year we will adjust it for inflation again on the President’s instruction, this time by 18.5 percent, which will raise the salaries of 4.8 million people. We are helping the regions bring the salaries of public sector employees in line with the President’s May executive orders. These employees work in many diverse areas, from healthcare and the social sphere to education, science and culture. Their salaries should be increased to the level determined by the President. We will continue this policy through this year, fully implementing the decisions envisaged in the President’s executive orders.

Another area is the programmes on reducing poverty in the regions of the Russian Federation. The majority of regions have such programmes. The local officials know better who needs assistance and how to provide it. In some cases it’s a social contract, in others retraining or upgrade courses. A flexible approach like this that considers the local specifics will allow the regions to meet their personnel needs more quickly.

The President emphasised that protection for maternity and childhood and support for families are indisputable values for each of us.

We continue to assist low-income families with children; there is an integral system for state support. The law on the unified monthly benefit in connection with the birth and upbringing of a child entered into force at the beginning of this year. Over 5 million children under 17 and 190,000 pregnant women, for whom this measure was designed, have used it.

We will continue improving the system of guarantees for our people through the social treasury to make sure they receive all of their support benefits on schedule and in full, and remotely, if they so wish, without excessive red tape and bureaucracy.

Colleagues,

I suggest discussing the objectives we need to fulfil in the near term for improving the living standards of our people.

May 4, 2023

Kevin Gosztola: After Years Of Refusing To Comment, State Department Backs Assange Prosecution

By Kevin Gosztola, The Dissenter, 5/4/23

The following article was made possible by paid subscribers. Support independent journalism on whistleblowers and press freedom and become a subscriber with this limited offer for World Press Freedom Week.

On World Press Freedom Day, the United States State Department abandoned its policy of not commenting on the case against WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange and essentially backed the prosecution against him.

Matthew Lee of the Associated Press asked State Department spokesperson Vedant Patel “whether or not the State Department regards Julian Assange as a journalist who would be covered by the ideas embodied in World Press Freedom Day.”

“I’m not asking for the [U.S. Justice Department point of view. I’m asking for what the State Department thinks,” Lee said.

It was not the first time Lee had posed this question. In 2021, on World Press Freedom Day, Lee asked if President Joe Biden’s administration was looking into the Assange case, “his detention, his extradition, the request for extradition here, the charges against him?”

“I realize you can’t speak for DOJ, but from the State Department’s perspective, is the current position still – does that still hold? Do you believe that Mr. Assange is a journalist?” Lee added. “And given the importance you place on accurate and factual information being disseminated, do you believe that the information that was published based on the U.S. government documents that he obtained and put out was either unfactual or inaccurate?”

Jalina Porter, who was a spokesperson for the State Department, avoided the question. “So to your specific on Julian Assange, we’ll have to get back to you on that.”

But now, with Biden going around repeatedly declaring that “journalism is not a crime,” Patel read a prepared response.

“The State Department thinks that Mr. Assange has been charged with serious criminal conduct in the United States, in connection with his alleged role in one of the largest compromises of classified information in our nation’s history,” Patel declared. “His actions risked serious harm to U.S. national security to the benefit of our adversaries.”

Patel continued, “It put named human sources to grave and imminent risk and risk of serious physical harm and arbitrary detention. So it does not matter how we categorize any person, but we view this as something, he’s been charged with serious criminal conduct.”

The response was lousy and stale. The State Department basically dusted off a few talking points from 2010, when WikiLeaks first published U.S. State Embassy cables that exposed the inner workings of U.S. diplomacy.

To be clear, Assange’s “role” was that of a publisher who received documents from U.S. Army whistleblower Chelsea Manning. A 2011 review by the Associated Press of sources, which the State Department claimed were most at risk from the publication of cables, found no evidence that any person was harmed. The potential for harm was “strictly theoretical.”

Lee appropriately pushed back on the idea that being charged with “serious criminal conduct” made Assange a person unworthy of support on World Press Freedom Day.

“Yeah, but anyone can be charged with anything. Evan Gershkovich has been charged with a serious criminal offense in Russia, and you say that he is a journalist, and he is obviously,” Lee replied. “And I just want to know whether or not you, the State Department – regardless of any charges that he faces – believe that he is a journalist, or he is something else.”

Patel contended the two cases are “completely different.” He said, “The United States doesn’t go around arbitrarily detaining people, and the judicial oversight and checks and balances that we have in our system versus the Russian system are a little bit different.”

The U.S. government subjected nearly 800 people to rendition, indefinite detention, and torture and brought them to Guantanamo Bay military prison, which was established a legal blackhole for alleged terrorism suspects. It’s still open, continues to hold detainees not charged with any crimes, and in fact, the United Nations recently condemned the US for keeping Abu Zubaydah in arbitrary detention, which “may constitute crimes against humanity.”

Yes—the U.S. does arbitrarily detain people. Just not people the U.S. thinks should be free from arbitrary detention.

“Okay. So, basically, the bottom line is that you don’t have an answer. You won’t say whether you think he is a journalist or not,” Lee stated.

The State Department cannot say that US officials do not believe Assange is a journalist because they know that puts them at odds with civil society organizations that they frequently partner with on press freedom issues and campaigns to free detained journalists.

Gershkovich’s case is not meaningfully different from the case against Assange. Russian intelligence accused Gershkovich of “collecting state secrets.” Like the U.S. government, the Russian government claims the authority to detain a journalist to make an example out of them and send a message that they will protect their military information from further disclosure.

Few may know, the State Department intervened in the extradition process to help the Crown Prosecution Service win their appeal after a district judge ruled that extraditing Assange would be oppressive for health reasons. Diplomats offered empty “assurances” that Assange would not be mistreated in U.S. custody and leaned on the United Kingdom to approve Assange’s extradition to preserve the close partnership between the U.S. and the U.K.

Now, on the same day, White House Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre was asked about Assange. “Advocates on Twitter today have been talking a great deal about how the United States has engaged in hypocrisy by talking about how Evan Gershkovich is held in Russia on espionage charges but the United States has Espionage Act charges pending against Julian Assange.”

The reporter who asked this question also suggested the US had lost the “moral high ground.” Unlike the State Department, the White House did not feel compelled to take this question seriously. “Look, I’m not going to speak to Julian Assange and that case from here,” Jean-Pierre blurted.

CODEPINK co-founder Medea Benjamin, CODEPINK member Tighe Barry, and others in the peace group probably deserve credit for forcing the State Department to respond to a question about Assange with something more than “no comment.”

Secretary of State Antony Blinken participated in a World Press Freedom Day event hosted by the Washington Post. As he sat down to talk with Post columnist David Ignatius, Benjamin stepped on to the stage. “Excuse us. We can’t use this day without calling for the freedom of Julian Assange.”

The Post muted the audio for the video broadcast as security swiftly dragged Benjamin offstage. Security was so rough that it made Blinken uncomfortable. He stood up from his seat and told them, “Take it easy. Take it easy. Take it easy, guys.”

Associated Press reporter Matthew Lee tied his Assange question to the protest, noting the case had been “raised perhaps a bit abruptly at the very beginning of [Blinken’s] comments.”

Perhaps, that is why the State Department had a canned response ready. Or maybe the State Department flack had an answer prepared because all the advocates chatting about US hypocrisy bother the department.

There is more political support in the world for ending the case than ever before, with parliamentarians in the U.K., Australia, Mexico, Brazil, and a handful of U.S. representatives urging the Justice Department to drop the charges. U.S. officials are afraid to engage reporters and defend the case in public.

Confrontation works. Letters to the Justice Department that demand an end to the case are welcome, but they do not have the capacity to provoke an immediate response as CODEPINK’s protest apparently did.

Why Putin Went to War: An Interview with Geoffrey Roberts

Flemming Rose, Editor-in-chief of Frihedsbrevet (Denmark), 4/22/23 (Machine translation)

For this week’s ‘Free Thought’, I have spoken with the British historian Geoffrey Roberts about an article he recently published in the Journal of Military and Strategic Studies under the title “Now or Never: The Immediate Origins of Putin’s Preventive War on Ukraine”.i We also talked about the historical craft, how the war in Ukraine will be viewed in 50 years, and what secret documents Roberts would like to see if he could get access to the Russian archives.

Geoffrey Roberts has researched and written about the history of diplomacy for many decades. In particular, he has dealt with the processes leading up to the outbreak of the Second World War and to the Hitler-Stalin Pact of 1939, which involved the division of Eastern Europe into spheres of interest between Germany and the Soviet Union. He is the author a voluminous work entitled Stalin’s Wars: From World War to Cold War 1939–1953, which was based on his studies in the Russian archives. Roberts is also co-author of a book on the wartime relationship between Churchill and Stalin and has written a biography of Georgy Zhukov, Stalin’s most important general during World War II. Most recently, Roberts has written a book entitled Stalin’s Library: A Dictator and His Books.

Reasons for War

Why did Vladimir Putin decide in February 2022 to invade Ukraine and start the biggest land war in Europe since World War II? And when did he make that fateful decision?

There are many opinions about that. It is one of those events that historians will write thousands of articles and books about for decades to come.

Some believe that Putin is driven by the ambition to restore the Soviet Union or the Russian Empire. Others point out that Putin is motivated by the desire to gain control of what is called “the Russian world”, which includes regions where the Russian Orthodox Church and Russian language and culture dominate.

Still others point to Putin launching the war to consolidate his power at home and save his regime from internal threats and opposition.

A fourth claim is that the decision to go to war was the work of an isolated, maniacal dictator. A dictator surrounded by puppets who was convinced the Russian army would be welcomed by a majority of the Ukrainian population.

A fifth explanation says that Putin feared a democratic Ukraine with a political order alternative to his authoritarian regime in Russia, which could lead disaffected Russians to rebel against the Kremlin.

Geoffrey Roberts rejects all these explanations. He believes that Putin went to war to prevent Ukraine from developing into an increasingly strong and threatening military bridgehead for NATO on the border with Russia.

According to Roberts, for Putin the decision to invade Ukraine was not only about the immediate situation; it was about a future in which he feared Russia would face an existential threat from the West. In that context, Roberts states, it is not decisive whether Putin is morbidly paranoid or whether his fantasies have no root in the real world. The key is what Putin actually thought and on what basis he made the decision to go to war; for Roberts as a historian, it is about uncovering the logic and inner dynamics of Putin’s reasoning that preceded the war.

Roberts does this by reviewing Putin’s public comments and statements from spring 2021 until the invasion in February 2022, comparing them with what he has said since.

His method is empirical, meaning that he reconstructs the story based on what Putin says and does. Roberts identifies a common thread of elements and talking points that recur all the way through the narrative – the fear of NATO expansion, concern about NATO missile defense in Poland and Romania, the transformation of Ukraine into an anti-Russia and a NATO armed outpost on the border with Russia, criticism of Ukraine for discrimination against pro-Russians and not implementing the so-called Minsk agreements of 2014 and 2015, which were an attempt to regulate the conflict between the Ukrainian central government and the Russian-backed separatists in eastern Ukraine.

According to Roberts, throughout the run up to the February 2022 invasion, Putin maintained that the Minsk agreements were the only mechanism available to deal with the dispute between Kiev and the Donbass rebels. Roberts also cites Putin’s ‘infamous’ summer 2021 essay on the historical unity of Russia and Ukraine, in which he laments alleged discrimination against Russians in Ukraine, declaring:

“We will never allow our historic lands and people close to us to be used against Russia.”