Michael Flynn's Blog, page 64

October 21, 2010

Tidbits

Regarding the recent essay on the brain atoms collectively called Prof. Haggard, Mr. Chesterton chimes in:

Similarly you may say, if you like, that the bold determinist speculator is free to disbelieve in the reality of the will. But it is a much more massive and important fact that he is not free to raise, to curse, to thank, to justify, to urge, to punish, to resist temptations, to incite mobs, to make New Year resolutions, to pardon sinners, to rebuke tyrants, or even to say "thank you" for the mustard.-- G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy

Syllogism of the Day

In a related vein

Major premise:

"You will know the truth, and the truth will make you free." -- John 8:32

Minor premise:

"There is no such thing as the truth." -- Scott Rudin, producer of The Social Network

Conclusion

Left as an exercise to the reader.

Beethoven Lives!

with the Finale to Beethoven's Fifth Symphony, conducted by a 3-yr old named Jonathan. One really must watch up to the end.

h/t The Anchoress

The Beat Goes On

Those of you who remember so far back as In the Country of the Blind will recall that Red Malone played at the clarinet and was heard from time to time attempting the clarinet obligato from High Society, a test piece for jazz clarinetists. In the final scene, the he plays it successfully in concert with Sarah Beaumont and others.

In the interests of full disclosure, I also played the clarinet; or rather played at the clarinet. I was passable for marching band, and could get partway through the slow movement of Mozart's concerto; but I never got really good at it, alas. But that does not stop me from admiring the expertise of others.

To get in the mood while writing In the Country of the Blind, I would play a "record" -- these were discs of vinyl on which music was recorded by an analog process. The record was by the New Orleans Ragtime Orchestra, and so the music was arranged for a small orchestra heavy on band instruments. This was the sort of orchestra which in the early 1900s played in movie theaters, skating rinks, municipal bandstands, dance halls, etc.

I found the cut on YouTube! Though I cannot answer for the odd graphic the tuber chose to accompany it! Forsooth. The clarinet solo comes in about halfway through. In the trio section, the passage is first a violin andante, then a clarinet solo, the both together. Enjoy.

And, since I am now in a ragtime/jazz mood, I present as a bonus feature "A Real Slow Drag" from Scott Joplin's second opera Treemonisha. A YouTube commentator on one of the rags said that if Joplin had not been black they would have made a statue of him. Of course, they did. It's in the San Antonio Opera House. Notice that a drag is not a rag; but neither is it a cakewalk. But the arms-linked side by side goose-stepping was characteristic of it. (A lot of the popular dances of the early 1900s were adapted from military marches. In fact, we might compare Joplin to Sousa.

And last but not least, to march you out with your head held high, and feet high stepping, we will close this evening's concert with Preservation Hall Dixieland Jazz Band. Dixieland is not ragtime. Rags keep a regular beat in the left hand (bass) but syncopate the right hand (treble). Dixieland jazzed up both clefs. (Although they did not either swing or rock the beat. Swinging meant to play two eighth notes as if they were the first and third note of a triplet. Swing high and swing low depended on which direction the notes went. Rock means to shift the beat from 1-2-3-4 to the back beat 1-2-3-4. But we digress.

In any case, here is The Gettysburg March. They play it first in march time, then they jazz it up.

October 18, 2010

Off the Reservation, Again

It's hard to fathom the obsession some scientists have with trying to prove that they have no minds. In Neuroscience, free will and determinism: 'I'm just a machine', the electrochemical reactions in the brain belonging to Prof. Patrick Haggard try to do just that. This is a bit like Parmenides trying to sway [move] his listeners into believing there is no motion in the world. But no doubt these chemical reactions were compelled to make the useless effort.

The reactions in the Haggard brain have devised a technique -- "transendental magnetic stimulation" -- which supposedly demonstrates that:

The reactions in the Haggard brain have devised a technique -- "transendental magnetic stimulation" -- which supposedly demonstrates that:"We don't have free will, in the spiritual sense. What you're seeing is the last output stage of a machine. There are lots of things that happen before this stage – plans, goals, learning – and those are the reasons we do more interesting things than just waggle fingers. But there's no ghost in the machine."

The chemical reactions reactions accomplish this by manipulating an "assistant" into using a magic wand to generate a magnetic field in the brain, triggering certain neurons into twitching a finger. Whereupon the entire edifice of Western Thought since Plato comes tumbling down.

Or not. It is not clear what he means by "free will, in the spiritual sense" or "ghost in the machine." But it is quite clear that the brain chemicals do not understand what is meant by "will" or "free." They assert reflexively that because we have reflexes that can be triggered externally we have no will.

But no one has ever asserted that there are no such things as involuntary actions, or that voluntary actions might be simulated by an artifice. With a flight simulator, we can take a 747 from New York to Paris; but that does not mean we will find ourselves in the City of Lights when we emerge. And it certainly does not mean that air travel is an illusion.

You will notice that all of the great refutations of "free will" involve bodily motions: flipping a switch, twitching a finger, and so on. Now, muscle spasms or even habituated physical actions are not the end of volition, although the formation of the habits is. That scientists, even neuroscientists, seem to fail to understand the nature of the will is startling; but really the sort of thing we would expect when they scamper off the reservation.

We might start with a few things free will [volition] does not mean.

It does not mean a random choice. It does not mean a successful choice. It does not mean an unpredictable choice.It does not mean an unforeseeable choice.It does not mean a surprising choice.It does not mean an unreasoned choice. It does not mean an unmotivated choice. It does not mean indifference to the ends chosen.It does not mean a deliberated choice. It need not mean a conscious choice. And it does not mean that the will is unencumbered by habit, error, mental or physical illness, or other impairment -- including magnetic wands. It only means that it is not determined by external forces. Someone could seize hold of Prof. Haggard's finger and twitch it mechanically, but the fact that an external force can also move his finger does not demonstrate that in the common course of nature Prof. Haggard can normally choose to do so.

The last bullet needs a comment: If the human subconscious is real, it is as much a part of the mind as any other; so subconscious choices are also encompassed by free will.

Part of the problem is the blindness of modern science to formal and final causation. These two causes are making a quiet re-appearance under new names like "emergent property"/"self-organizing system" and "attractor basins," but they have been banished from our thinking of causation for several hundred years. Therefore, Haggard and others misunderstand both "will" and "free."

The electrochemical reactions in the brain are simply the material cause of the choice. They are not the formal or final causes.

There is no "I"

Prof. Haggard proves this by saying:

"There are physical laws, which the electrical and chemical events in the brain obey. Under identical circumstances, you couldn't have done otherwise; there's no 'I' which can say 'I want to do otherwise'. It's richness of the action that you do make, acting smart rather than acting dumb, which is free will."

From this we conclude that Prof. Haggard is saying that there is no Prof. Haggard saying this. Literally! The last sentence appears to be pure gibberish, simply the outputs of electro-chemical events in the Haggard brain. His brain chemistry did not condescend to explain how there could be "smart" or "dumb" or indeed "rich" under his own assumptions.

So, What is This "Liberum Arbitrium"?

First of all, note that the term we translate as "free will" is liberum arbitrium, which means "free judgment." (See Summa theologica, Pars I, Quaestio 83) Ever since the triumph of the will, we have gotten the will confused with concupiscence and have forgotten that it once meant part of a rational act.

When we see a basketball on the table we don't say we see a basketball and we see a sphere. The basketball just is spherical. Even if it is punctured and deflated, we don't say that "therefore sphericity is an illusion." We would say that its sphericity has been impared. If we buy a basketball, we are not charged for multiple things (rubber, air, sphericity, umber color, one, etc.) but for a single thing (a basketball). This is because in physical existence the form is inseparable from the matter. "Every thing is some thing."

The word anima, which we translate as "soul," means "alive." So to ask if X has a soul is to ask whether X is alive. This can be verified empirically. But the soul is simply the form of a living being. There is no more a separate "ghost in the machine" than there is a separate "sphere in the basketball." The "ghost" just is the machine, or rather the form of the "machine."

The powers of a body derive from its form. Sodium and chlorine are made of the same materials: protons, neutrons, electrons. What makes one a flammable metal and the other a poisonous gas is the number and arrangement of their parts; i.e., their form. A form may or may not be "spiritual," but it is certainly not material.

The rational soul differs from the sensitive [animal] soul by the addition of the two rational powers: Intellection and Volition. In the sensitive soul (Stimulus to Response in the drawing) particulars are perceived by the inner senses, which we may call collectively "Imagination." The Emotions are an appetite or desire for these percepts. (This includes the desire to avoid.) Hence, they are called the "sensitive appetites." (Autonomous actions are the "short circuit" in the diagram from Perception directly to Motor Powers.)

The rational soul differs from the sensitive [animal] soul by the addition of the two rational powers: Intellection and Volition. In the sensitive soul (Stimulus to Response in the drawing) particulars are perceived by the inner senses, which we may call collectively "Imagination." The Emotions are an appetite or desire for these percepts. (This includes the desire to avoid.) Hence, they are called the "sensitive appetites." (Autonomous actions are the "short circuit" in the diagram from Perception directly to Motor Powers.) The Intellect reflects on the perceptions of the senses and abstracts conceptions from them. We perceive Lassie and Fido and Rover and Spot; but we must conceive "dog." The concept "dog" has no physical existence as such. Only particular dogs have physical existence. The form of "dog" is something over-and-above this dog or that dog.

The Will or Volition is an appetite for the products of the intellect, just as the emotions are appetites for the products of the imagination. Thus, a twitching finger is not the proper object of an act of will, but a concept like "come here" which is signified by the twitching finger may well be.

Aquinas called a human act precisely those acts performed with intellect and will. All other acts were "acts of a man" but not "human acts" as such. The intellect through understanding, knowledge, and wisdom recognizes/knows an end. The will, exercising justice, temperance, and courage, desires the end and chooses the means to achieve it. The link between the two is prudence, by which the intellect decides that the means are proportionate to the ends.

Thus, every voluntary act is two acts. Formal cause: An interior act of the will ["intention"] whose object is the end; and Material cause: The exterior act whose object is the means. Thus, materially, I might reach out and grab a baseball bat. Formally, I may intend to hit a home run or (more modestly) a base hit. Or I might intend to stimulate Prof. Haggard's brain atoms with it.

And of course, not all acts are voluntary. Some are induced by baseball bats to the head, or by strong drink, or by magnetic wands. Because our friend Haggard deliberately restricts himself -- or his brain atoms restrict him, will he, nill he -- to purely material causes, the whole concept of "intention" becomes invisible to his methodology, and so invisible to his brain atoms. No wonder he does not see intention! And what he will not see cannot exist.

Now, What About That "Free" Part

To say that the will is free is simply to say that it is not determined externally to some particular end. This does not mean we are indifferent to the end. A dog that is hungry will eat. A man who is hungry may fast from piety, diet from vanity (or health), dine abstemiously, pig out, etc. Those who are expert in the measurement of inanimate objects tend to confuse motives or reasons with causes. But that someone is motivated by the desire to lose weight does not mean that his behavior at the buffet table is caused by that desire in the same way that a current is caused by and electro-motive force.

James Chastek summarized this in an Interior Dialogue on Free Will, which I have taken the liberty of reproducing here. I have renamed his "A" and "B" for my own amusement.

Socrates: Does it seem reasonable to say that will is a kind of appetite, and that we can question whether this appetite has some sort of freedom? Even if “will” doesn’t exactly mean “appetite”, you’d still admit that we have desires and appetites.

The Athenian: Yes. ”Will” doesn’t sound exactly the same as appetite or desire to me, but we really do have desires or appetites, and I deny that we have any real choice about which one we are going to follow. A perfectly formed science could tell us why some monks follow the desire or appetite to fast in the desert and pray while playboys follow the desire to live the high life. But they had no choice but to follow the desire they followed.

Socrates: So what sort of thing is desire? For example, can we desire something that we are utterly ignorant of, or do we at least have to have some idea of it?

The Athenian: I’m not sure that “not being utterly ignorant of X” and “having some idea of X” are the same, but that seems right.

Socrates: So the desire for X follows some awareness of it -- though this can mean many different things. The desire for peace, for example, can be had even during war.

The Athenian: Right.

Socrates: So you’re claiming that we have no choice but to desire the goods we desire?

The Athenian: Right, once we learn enough, we’ll know exactly why we see all these things as good. Just look at what evolution can explain about beauty, morality, altruism, etc.

Socrates: But we desire these goods only so far as we know them?

The Athenian: Yes

Socrates: Now do we know everything we desire with absolute clarity, or not? If we want peace, do we know exactly what the peace will consist in, how we will get to it, how fast we can attain it, and all the other relevant details?

The Athenian: No.

Socrates: But then our knowledge of these goals is vague and indeterminate, and could be fulfilled in any number of ways.

The Athenian: Right.

Socrates: But if I truly desire, say, peace, and desire follows knowledge, then if the knowledge is indeterminate then the desire is indeterminate. But isn’t an indeterminate desire the opposite of a determinate desire? So isn’t this an undetermined desire -- a free will?

Or to put the matter in simpler if less entertaining form: Since we cannot will what we do not know, the freedom of the will follows necessarily from the incompleteness of our knowledge. Presumably, should there come a time when we see all things clearly and not as if through a glass darkly, then the will will be perfectly ordered toward the ultimate good, of which all lesser goods are mere reflections. (The proper object of the will is the good. No one desires what they believe is bad.)

Chastek again, in a "Ramble on free will"

St. Thomas explains the freedom of the will though the indetermination of the intellect: we choose in virtue of some concept or idea, but our idea is not determined to some one particular, so neither is our choice. Whenever I read debates about “libertarian free will”- or scientific trials that hook up electrodes to a guy's head to anticipate what he will decide when we tell him to make some random choice- I get the sense that the debaters have a much more elaborate notion of “free will” than St. Thomas had. Who can object to the idea that we act in virtue of concepts that are not sufficiently determined to one result, and so far as this is true, our action is not determined to a result? Do we really need to argue about this? There is mountain of after-market qualifications we can add to this rather weak account of free will. Habits (which for St. Thomas are any determination of a power, whether this arose from personal, cultural, or genetic origins) certainly play a role in fast-tracking our undetermined concepts to one deteminate thing. A good deal of life needs to be simply executed automatically, and so much of our action- probably much more than is worth thinking about- is almost certainly “determined” in the sense of foreseeable by another. Do we really need a brain scan to tell us this? Can’t we figure this out by living with someone for a week?

This is why, as he puts it, when an experimenter tells his subject to "choose one" of several objects or symbols, the presumption of free will is built in: not by use of the word "choose," but by use of the word "one." To which particular symbol does "one" refer?

"'One' is indeterminate, and so there is a necessary indetermination in 'choose one.' That said, this sort of indetermination is utterly compatible with some ability to foresee the results someone’s action, especially when all one must do is foresee it in a way more accurate than sheer chance. My wife and my mother could probably foresee my choices before I make my decision more accurately than sheer chance."

Additional reading:

Chastek essays and comments:

Determinism as a cause of free will

Free Will and Electrodes

The Old Stagerite is here

Nichomachean Ethics: Book III, ch. 1-5

And of course: Aquinas himself

Summa Theologica: Part I, Q. 82, The Will

Summa Theologica: Part I, Q. 83, Free Will

October 17, 2010

You Go, Huizinga!

The Modern Ages began conventionally ca. 1500 and ran until fairly recently. Just as the 15th century was the "Autumn of the Middle Ages" (as Johan Huizinga's book was titled) so too has the 20th century been the Autumn of the Modern Ages. All those things that marked the Modern Age began to fade or change: Cities, the Bourgeois, Science, Privacy, Science, Industry, and so on. It is not that the new age (whatever it is to be called) will be better or worse. The Classical Ages faded into a barbarian Dark Age; the Middle Ages faded into a Renaissance. Which was the worse disaster is anyone's guess.

We always imagine the future as being something like the present, only more so. In the 50s, the future was going to be the 50s -- with flying cars. In the 70s, it was going to be sex, drugs, and rock-n-roll forever. But an age is not defined by its gadgets. Even if we one day get our flying cars, they will not make that age like the gung-ho, white-bread, techno-worshiping 50s. Sorry, Jetsons. An age is defined by the type of person who lives in it.

The beginning of the end for the Modern Ages lay in Europe's mutual suicide pact of 1914-1945 (with intermission). But when can we say the Modern Ages ended?

Art, as usual, runs ahead of the curve. What we call "modern art" is decidedly "post-modern," since the essence of the Modern Ages was representational.

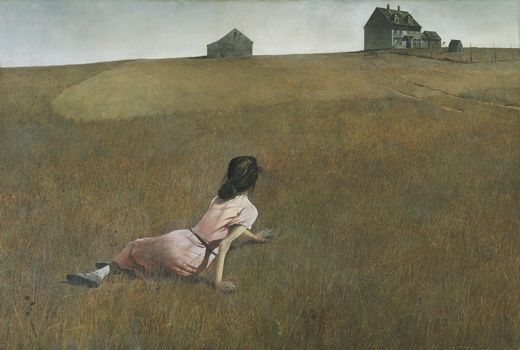

Quiz: Below the cut are pictures of couples and pictures of artwork from each of the Modern Ages. Between which set do your find a break in the Modern tradition?

1. Renaissance:

2. Scientific Revolution

3. Age of Reason

4. Industrial Revolution

5. High Modern Age

6. Post-Modern Age

October 15, 2010

Gliese 581g, We Hardly Knew Ye

The Ongoing Crisis

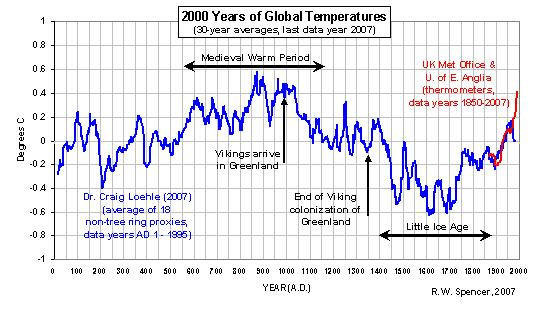

Michael Mann discovered that the thermometer measurements of recent decades diverged from the tree ring proxies for the same times, so he dropped the tree ring data from the tail end of his chart and replaced it with thermometer data. This was to "hide the decline" showed by the tree ring data. But what it showed was that tree rings are not good proxies for temperature. And if not now, then not in the past.

So what happens when you leave tree rings out of the pictures?

h/t j.pourmelle

October 14, 2010

October 9, 2010

In the Lion's Mouth

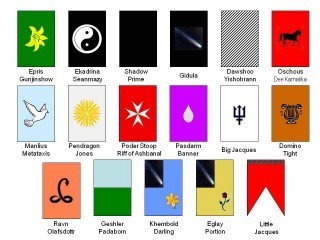

The Shadows of the Lion's Mouth are based loosely on 15th century Burgundian knighthood only with way cool ninja type weapons. The banners mentioned in the course of the story include, in order of rank:

1. Shadow Prime, Father of the Abattoir: Black, no mon

2. Ekadrina Seanmazy: Black, a taiji

3. Gidula: Black, a comet natural

4. Dawshoo Yishohrann: Black on white, diagonal

5. Oschous Dee Karnataka: Scarlet, a black horse

6. Epris Gunjinshow: Green, a yellow lily

7. Manlius Metataxis: Sky Blue, a white dove

8. Pendragon Jones: Silver, a yellow mum

9. Poder Stoop, the Riff of Ashbanal: Scarlet, a white maltese

10. Big Jacques: White, a prussian blue trident

11. Domino Tight: Umber, a lyre

12. Ravn Olafsdottr: Coral, a black snake twisted

13. Geshler Padaborn: Sky blue over hunter's green

14. Little Jacques: Red swallowtail

15. Khembold Darling: Light blue, a yellow daffodil; Gidula's comet quartered

16. Eglay Portion: Tan, a rose natural; Gidula's comet quartered

Pasdarm banner: Purple, a single teardrop. Flown at tourneys (pasdarms) in which Shadows fight for honor or vengeance.)

Quartering another Shadow's mon means that one is subordinate to the other.

This Wonderful Modern Age, redux

h/t John Wright

Michael Flynn's Blog

- Michael Flynn's profile

- 237 followers