Michael Flynn's Blog, page 51

July 10, 2011

Musings on the borderland

What is Fantasy?

CSI: Crime Scene Investigation ran an episode called "A Space Oddity" that involved a fictitious TV show titled Astro Quest. In the course of investigating a murder at Whatificon, a bit of byplay ensues between David Hodges, the Trace tech, and Mandy Webster, the Fingerprint tech at around the 1:00 mark on this video

So is Mr. Ed hard SF but Star Trek is fantasy? Maybe we can call it "hard fantasy"?

What tropes of hard SF really qualify as fantasy? Earlier in the game we identified strong AI and downloading human minds into computers as being philosophically impossible, although True Believers in the parousia of the download, when they throw off this corruptible body and put on a new and incorruptible body -- gee, that sounds familiar -- and achieve the Singularity, the Rapture of the Nerds, will never believe the Chinese Room, let alone the Gödelian proof. In our next installment, we will ask:

Is Genetic Engineering a Real Possibility?

By a real possibility, we mean a possibility in the Real World™, not in the Platonic world of ideal abstractions, where one may merely wave a hand, o'erleap the Singularity, and cry "Make it so."

CSI: Crime Scene Investigation ran an episode called "A Space Oddity" that involved a fictitious TV show titled Astro Quest. In the course of investigating a murder at Whatificon, a bit of byplay ensues between David Hodges, the Trace tech, and Mandy Webster, the Fingerprint tech at around the 1:00 mark on this video

So is Mr. Ed hard SF but Star Trek is fantasy? Maybe we can call it "hard fantasy"?

What tropes of hard SF really qualify as fantasy? Earlier in the game we identified strong AI and downloading human minds into computers as being philosophically impossible, although True Believers in the parousia of the download, when they throw off this corruptible body and put on a new and incorruptible body -- gee, that sounds familiar -- and achieve the Singularity, the Rapture of the Nerds, will never believe the Chinese Room, let alone the Gödelian proof. In our next installment, we will ask:

Is Genetic Engineering a Real Possibility?

By a real possibility, we mean a possibility in the Real World™, not in the Platonic world of ideal abstractions, where one may merely wave a hand, o'erleap the Singularity, and cry "Make it so."

Published on July 10, 2011 21:09

July 9, 2011

July 8, 2011

Blatant commercialism

EBooks on Parade

A new Kindle Edition of Fallen Angels is up on Amazaon.com for the princely price of US$4.99, a mere Abe Lincoln. Buy early and often. The recent behavior of Old Sol may make it more timely than not! Colder times ahead, perhaps.

A new Kindle Edition of Fallen Angels is up on Amazaon.com for the princely price of US$4.99, a mere Abe Lincoln. Buy early and often. The recent behavior of Old Sol may make it more timely than not! Colder times ahead, perhaps.

This edition is published by the Authors Themselves: Larry Niven, Jerry Pournelle, and your humble servant, courtesy of Managing Partner Pournelle and his chaos manor advisors.

The original drafts were actually written when Global Cooling as the crisis du jour was just giving way to Global Warming, and the idea of one as the antidote for the other was just too delicious.

And as long as we are on the subject of ebooks, another helpful reminder that there is a Kindle edition of a novelette of mine, called

The Iron Shirts

, from tor.com for a paltry US$0.99, a mere George Washington. This is an alternate history story of treachery, deceit, and other fun things.

And as long as we are on the subject of ebooks, another helpful reminder that there is a Kindle edition of a novelette of mine, called

The Iron Shirts

, from tor.com for a paltry US$0.99, a mere George Washington. This is an alternate history story of treachery, deceit, and other fun things.

And last but not least is the re-issue of the story collection, The Forest of Time . , available as a Kindle for US$9.99, a mere Alexander Hamilton. At first, because it includes my epic poem "There's a Bimbo on the Cover" we had thought to use this cover:

But cooler heads prevailed and it was issued with the less lascivious cover shown below.

A new Kindle Edition of Fallen Angels is up on Amazaon.com for the princely price of US$4.99, a mere Abe Lincoln. Buy early and often. The recent behavior of Old Sol may make it more timely than not! Colder times ahead, perhaps.

A new Kindle Edition of Fallen Angels is up on Amazaon.com for the princely price of US$4.99, a mere Abe Lincoln. Buy early and often. The recent behavior of Old Sol may make it more timely than not! Colder times ahead, perhaps. This edition is published by the Authors Themselves: Larry Niven, Jerry Pournelle, and your humble servant, courtesy of Managing Partner Pournelle and his chaos manor advisors.

The original drafts were actually written when Global Cooling as the crisis du jour was just giving way to Global Warming, and the idea of one as the antidote for the other was just too delicious.

And as long as we are on the subject of ebooks, another helpful reminder that there is a Kindle edition of a novelette of mine, called

The Iron Shirts

, from tor.com for a paltry US$0.99, a mere George Washington. This is an alternate history story of treachery, deceit, and other fun things.

And as long as we are on the subject of ebooks, another helpful reminder that there is a Kindle edition of a novelette of mine, called

The Iron Shirts

, from tor.com for a paltry US$0.99, a mere George Washington. This is an alternate history story of treachery, deceit, and other fun things. And last but not least is the re-issue of the story collection, The Forest of Time . , available as a Kindle for US$9.99, a mere Alexander Hamilton. At first, because it includes my epic poem "There's a Bimbo on the Cover" we had thought to use this cover:

But cooler heads prevailed and it was issued with the less lascivious cover shown below.

Published on July 08, 2011 17:30

July 7, 2011

The Craft

Entitlement, Part II

The First Shall be Last

The title may be the first thing the reader sees, but it might be the last thing the writer sees.

Other writers, however, don’t come up with a title until the story is complete or near enough. For many, the final title is a struggle or, in Michael Swanwick’s case, “a hideous struggle.” His working title for the award-winning Stations of the Tide was… Science Fiction Novel, and it “came perilously close to being published as Sea-Change, being saved from this fate on literally the last day the title could have been changed.” Nancy Kress seldom has even a working title while she writes, and often struggles with the titles afterward. “I have no good titles that I chose myself,” says Nancy Kress, “with a few exceptions. Otherwise, I grab the sleeve of any one I can and say ‘Will you read this and title it for me?’” Geoffrey Landis says, “I usually struggle for a while and then give up and give it something obvious.” Ed Lerner tells us, “I generally go through several titles before one sticks.” For Harry Turtledove, it is “almost always a struggle” with occasional exceptions. His original title for "The Pugnacious Peacemaker" (a sequel to Sprague deCamp's “Wheels of If") was "Making Peace with the Land of War,” which he thinks was perhaps too long and obscure.

On the other hand, Juliette Wade says that while she has struggled once or twice with titles, she usually doesn’t have that much trouble, especially with her Allied Systems stories. For Bill Gleason, titles “don’t come easily, but it hasn't really been a struggle either.” I would have to put myself in this category, too. I often have more titles than stories. Or perhaps more accurately, where some folks have working titles, I have working stories; that is, story ideas, concepts, and such to which I’ve given a title/label and placed on a to-do list. A story entitled “On the Shore of the Endless Ocean” has been lying doggo for some years now in a state of I-sorta-know-what-it-will-be-about-but-not-quite.

Jack McDevitt swings both ways. He has occasionally spent an entire year trying to come up with a title and still ended with one that was unsatisfactory. “The Hercules Text was my first novel,” he says. “The book, I’m happy to say, was considerably better than the title, which made it sound like a school assignment.” But he had other titles, like A Talent for War, before he had even the germ of a plot to go with it.

Authors’ Favorites.

Whether the result of hideous struggle or happy inspiration, whether captured ahead of time or only after the story has revealed its name, a title sometimes hits that sweet spot. I asked the Committee of Correspondence which titles of their own they were especially pleased with.

Michael Swanwick is partial to two. The first is “Mother Grasshopper,” a story set on a planet-sized grasshopper, because, he says, only the second word is literal. “Mother” is figurative. “It refers to no thing or fact that you can find in the story,” he says, “but it involves the reader in interpreting the story’s meaning and adds to its depths. That title came about in the usual, sweaty, making-lists-and-cursing way.” He also likes “‘Hello,’ Said the Stick” and defies anyone to turn to that page of Analog and not read the first paragraph or two, just to see what the heck is going on.” Definitely an arresting title.

For Geoffrey Landis a favorite title is his recent Nebula-nominated story "Sultan of the Clouds." “It seems appropriate for the story,” he says, “yet somewhat lyrical.”

Juliette Wade thinks "Cold Words" was her most effective title because “it gave good intellectual guidance, captured the core of the story, and also had a lot of emotional content and potential for rousing curiosity.”

Ed Lerner is partial to his "Dangling Conversations," a novelette dealing with SETI. He says it “fits the story (because radio-based comm between stars is going to be slow, with years between question and answer), sounds intriguing (who's talking, and what's been left in abeyance?), and avoids giving away anything critical.” He has no idea how he came up with it. It just popped out of his subconscious.

Bill Gleason lifted "Into That Good Night" from a poem by Dylan Thomas. But he believes it especially fitting because it hints at both the action of the story and one of its major themes.

Harry Turtledove likes In the Presence of Mine Enemies, The Man With the Iron Heart, and "Lee at the Alamo" (upcoming on tor.com) “They fit the stories and seemed tolerably memorable.”

For Jack McDevitt, a favorite is The Engines of God. “It implies the cosmic power which constitutes the threat in the novel, and it also has an epic feel, perfect for the novel that introduced the omega clouds and Priscilla Hutchins. Time Travelers Never Die works well also, depicting the relatively light tone of the novel, and the central point that you always know when to find a time traveler, so she is never really dead.”

Nancy Kress likes "Out of All Them Bright Stars" and "The Price of Oranges" because she chose them herself!

John Wright says his titles are “about average as titles go.” He offers two novels: Null-A Continuum has the unusual term ‘Null-A,’ and since the first book dealt with the world of Null-A, and the second with a galactic war, he upped the ante to ‘Continuum,’ which “has that nice shiny science fictional ring to it. Sounds all technical and stuff.” He also likes Last Guardian of Everness. It has an unusual or invented word, everness, “which conveys a hint of eternity.” And “there is an irony or an oddity in the title, since if the ‘Everness’ (whatever that is) lasts forever, how can there be a last one of them? The word ‘Guardian’ is also mildly archaic, and tells the reader this is a fantasy.” Finally, ‘Last’ conjures that sense of melancholy so common to fantasy. But his all-time favorite is a novella, “One Bright Star to Guide Them.” “That title to me captures an eerie magic hard to describe.”

I asked them, too, which titles by other writers struck them as most effective.

Michael Swanwick thinks Terry Bisson’s “Bears Discover Fire” is deceptively simple, inherently interesting, easy to remember, and rouses the reader’s curiosity. “And it fits the story perfectly. You can’t do better than that.”

Geoffrey Landis tells us that Roger Zelazny was good with titles. Creatures of Light and Darkness resonates with him. (The title appealed to me, too, and I bought the book on no other basis than that. Note the contrast between light and darkness and the suggestive ambiguity of creatures. )

Juliette Wade said that it was hard for her to pick a favorite title in others' work, but says “I do always enjoy titles which have unusual grammatical structure, though overall I'd say content is more important. I like titles which are a bit mysterious.” She named my own "Where the Winds are All Asleep" and Ursula LeGuin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, which she found “nicely intriguing.”

Ed Lerner likes A Fire Upon the Deep and A Deepness in the Sky, both by Vernor Vinge. Both titles are “striking, fit their stories well, and avoid giving away any plot.”

For Harry Turtledove, three satisfactory titles that spring to mind are For Whom the Bell Tolls (Hemingway), Stranger in a Strange Land (Heinlein), and Lest Darkness Fall (deCamp).

Jack McDevitt says that two of his favorite titles are Glory Road (Heinlein) and “Out of All Them Bright Stars” (Kress). “I’d buy either book without knowing anything else about them, even their authors.” He’s not sure why. “Other people’s titles just blow me away. Or don’t.”

John Wright likes The Dying Earth (Jack Vance). “These two words are quite ordinary taken separately, and forgettable, whereas together immediately conjure that sense of cosmic deeps of time which is the heart of science fiction, and, at the same time, that haunting sense of melancholy which is the heart of fantasy. It immediately sets the reader to wonder: we have seen creatures die, but the Earth?” Regarding Well at the World’s End (William Morris), he defies anyone to come up with “a title more rich with the echoes of the sounds of the horns of elfland dimly blowing.”

Going out of genre, some titles I’ve especially liked are the thriller As the Wolf Loves Winter, by David Poyer, and the detective novel When the Sacred Ginmill Closes, by Lawrence Block. The former suggests something of the bitter cold and the predatory characters in the story; the latter suggests a sea-change in the characters’ lives. I bought both books on little more than the title, and you can’t ask more of a title than that. I have also found Cordwainer Smith (“The Colonel Came Back from the Nothing-at-All"), Harlan Ellison (“‘Repent, Harlequin!’ Said the Ticktockman”), and R.A. Lafferty (“The Groaning Hinges of the World”) to be producers of astonishing titles. But be careful with astonishing titles if you don’t have an astonishing story to go with it.

Where Do You Get Your Titles From?

Titles crawl out from under a variety of rocks, even when we have to turn the rock over with a stick. Four sources are the four dimensions of a story: setting (or milieu), theme (or idea), characters, and plot (events or “peak situations”).

1. Setting: A book can take its title from the milieu in which it takes place. This can be literal or metaphorical. Examples include: Ringworld (Niven). “The Gate of the Hundred Sorrows” (Kipling). Eternity Road (Jack McDevitt). Venus (Ben Bova). Red Mars (Kim Stanley Robinson). “Gibraltar Falls” (Poul Anderson). Or my own Eifelheim. Because SF often involves strange milieus, and readers are attracted to futuristic or alternate settings, this is a popular class of title.

2. Idea: The title can be a word or phrase that captures the essential theme of the story. This is probably the most popular category of titles. The idea may be described directly, as in the mainstream book Room at the Top (John Braine) or by means of a double-meaning, as in The Bookman’s Wake (John Dunning) or a paradox, as in Casualties of Peace (Edna O’Brien). Examples in SF include: Thrice Upon a Time (James Hogan), Mission of Gravity (Hal Clement) or Dark as Day (Charles Sheffield).

3. Character: The name or description of a key character, either directly naming the individual (or group of individuals) or by using a metaphor. Examples include: The Odyssey (Homer), David Copperfield (Dickens), and Lolita (Nabokov). Titles taken from protagonist names are less common in SF, but we have Kinsman (Bova), Starman Jones (Heinlein), and of course Conan the Barbarian (Robert E. Howard). Metaphorically, we have character-driven titles in The Fellowship of the Ring (Tolkein), The Revolving Boy (Gertrude Friedberg), and “The Man Who Came Early” (Poul Anderson).

4. Event: A name or phrase that captures some peak situation or occurrence within the story. Typical examples include “The Madness of Private Ortheris” (Kipling), The Fall of the Towers (Samuel R. Delany), and “The Green Hills of Earth” (Heinlein). The last refers to a poem composed by the character Rhysling during the story crisis. Mars Crossing (Landis) and “Nano Comes to Clifford Falls” (Nancy Kress) are summaries of their respective plots.

Poking the Muse

There are several ways of jogging the creative juices to emit a title from the brain-pan.

1. Simple description. A nanotech story of mine was called “Werehouse” because that was where people went to be illegally transformed into animals. Such titles often take the form Noun (The Syndic, C.M. Kornblunth)Adjective Noun, (The Maltese Falcon, Dashiell Hammett),Noun Noun (Dinosaur Beach, Keith Laumer),Noun of Noun, ("Flowers of Aulit Prison," Kress)and so forth. For place-titles, try tossing prepositions like At, In, On, To, etc. while you ponder your story and you might come up with To the Tombaugh Station (Wilson Tucker), “On Greenhow Hill” (Kipling), In the Country of the Blind (yours truly).

2. A line from the story. Search the text of your story for a line that seems to encapsulate the story. That was the origin of my in-progress novella, “Places Where the Roads Don’t Go.” It was also how Nancy Kress found titles for "Out of All Them Bright Stars" and "The Price of Oranges," and R.A. Lafferty obtained “Camels and Dromedaries, Clem.”

3. Famous (or not so famous) quotations. Make a list of key words from each of the four categories mentioned above and go to Bartlett’s to see if there’s a quotation that illuminates the story. Shakespeare and the Bible have been overused, though there is a good reason why people fish there for pithy quotes. But why not look for the road less traveled and try Matthew Arnold, Algernon Swinburne or Lewis Thomas? This was how I found “Where the Winds Are All Asleep,” “Great, Sweet Mother,” and “The Common Goal of Nature.” I also mined quotes for “Dawn, and Sunset, and the Colours of the Earth” and “The Clapping Hands of God.” Harry Turtledove took “In the Presence of Mine Enemies” from Psalms 23:5 – and “The Road Not Taken” from Frost. Bill Gleason, as already mentioned, used Dylan Thomas. Lawrence Block’s Small Town comes from a passage by John Gunther – and refers to New York City, which makes for an arresting contrast.

4. Pairings. BruteThink is a creative thinking tactic. It consists of finding two words that are individually contrasting but which in combination capture the story. From the list of key terms suggested by the four categories, look for pairs that clash. Charles Sheffield’s Dark as Day, for example; or Nancy Kress’ “Flowers of Aulit Prison.” Flowers + Prison? What’s that all about? Another contrast, which Jack McDevitt has mentioned, is to join a physical thing with an abstraction, as in his Infinity Beach, Nancy Kress’ Probability Moon, or Kipling’s “Dayspring Mishandled.”

5. Crossing categories. A good title might suggest itself by pairing key words from different categories. For example, an event and a place, as in Kipling’s “The Taking of Lungtungpen” or Dashiell Hammett’s “The Gutting of Couffignal”; or a character and a place, as in de Camp’s Conan of Cimmeria. Try each pairing and see what comes up: “The Character of Setting,” “Of Idea and Character,” and so on.

6. Random matches. Mozart used to roll a trio of dice to suggest chord progressions. He would take the randomly-generated chords and see if they inspired his creative juices. If not, he would keep rolling until something came up. The writer can do the same thing, taking words from the list of key words purely at random and rubbing them against one another to see if any of them strike sparks.

Since I know my own titles best, I can offer a few comments on several stories in various stages of (in)completion: “Places Where the Roads Don’t Go” An idea-title. The story began with a different title, but partway through one of the characters said, “but there are places where the roads don’t go.” Because it encapsulated the entire theme of the story and the relationship between the two main characters, it was forthwith promoted to title. “Buried Hopes” This follows Jack McDevitt’s dictum of pairing something physical (Buried) with something abstract (Hope). It was the original working title for the first item, above. Never waste a title, sez I! Now it is part of a story cycle that also includes “Remember’d Kisses” and “Captive Dreams,” so it employs parallel Adjective Noun structure. It also has a second meaning that becomes clear near the end. “Hopeful Monsters” This was a title that existed before there was a story plot to go with it, only a theme or idea. The reference is to Goldschmidt’s “hopeful monster theory” that evolutionary change may involve, not incremental Darwinian steps, but big leaps (mutants, ‘monsters’ in the technical sense) that have great possibilities (hence, ‘hopeful’). The story applies that idea to genetic engineering intended to optimize human beings. There is a nice contrast between the two words and a double meaning lurking in the story. “Elmira, 1895” This is a place title; and involves a fictional visit by Rudyard Kipling, then living in Vermont, to Samuel Clemens in Elmira, regarding a manuscript that Clemens has written and some newspaper stories that Kipling had clipped. A title like this suggests a tight focus on a single event at a particular time and place. “Mayerling” Another place-title for an alternate history centered on Crown Prince Rudolf and his hunting lodge at Mayerling, near or around which numerous other characters – Strauss Jr., Freud, Klimt, et al. – have also lived, hiked or picnicked. In addition, I have portions of two potential novels: The Chieftain is a character-title referring to David O’Flainn, chief of the Sil Maelruain ca. 1224, in a medieval fantasy. Since the basic plot is already in the Annala Connaughta and a practice version of the whole thing, written in college, sits in a box beside me, there is actually some hope of whapping it into shape. The title is appropriate because the character of the clan chieftain is the focus of the story. The Shipwrecks of Time is from a quotation by Francis Bacon about the haphazard nature of surviving antiquities. I saw it in a chapter quote in one of Jack McDevitt’s Alex Benedict novels and I began thinking about a story in which bits and pieces of haphazardly surviving data gradually comes together to... Well, there are all sorts of shipwrecks, aren't there? A Note on Series

Stories or novels in a series present an additional challenge. They are often expected to carry some sort of commonality. Each of John D. MacDonald’s Travis McGee books has a color in the title; as does Kim Stanley Robinson’s Martian trilogy. The Cliff Janeway novels of John Dunning all have “booked” or “bookman” in the title. My own Firestar series had the word “star” in each of the titles. Nancy Kress did the same with her Sleepless books and her Probability series. Ed Lerner and Larry Niven included the phrase "...of Worlds" in each book of their Fleet of Worlds series.

But this is by no means a requirement. Neither Jack McDevitt’s Priscilla Hutchins novels nor his Alex Benedict novels have “marker” titles. Neither do my own Spiral Arm books. Lawrence Block uses a title pattern for his Burglar books (“The Burglar Who….”) but not for his Matthew Scudder books. However, a title pattern is a choice that you might keep in mind if you have a series.

SummaryWhile the title is not the only gateway into a book or story, it is still important to stir the reader’s interest with a good title. Novels are often helped by the cover art, but magazine stories are not. A good title should be i) arresting, ii) suggestive, and iii) challenging. “Arresting” means the use of words or phrases that catch the attention: sometimes neologisms or “SF” words, the use of “strange pairs” like contradictory terms or physical+abstract, or by using unusual grammar. “Suggestive” means a title that tells the reader something about the story without revealing too much about it. It ought to hint at whether the story will be SF, fantasy, or something else, tell us if the story will be serious or comic, intended for mature or YA readership, etc. A great title for one could be terrible for another. “Challenging” means that the title may have hidden meanings or a significance that does not become clear until after the story has been read. Quotations or allusions, double meanings, and the like are useful for this purpose. Titles can be short or long, straightforward or elaborate. They can be found in a variety of ways: i) from the four dimensions of a story – setting, theme, character, and/or plot events;ii) from quotations within the story itself;iii) from apposite external quotations. Lists of key words expressing setting, theme, character, and/or plot events can be “mixed and matched” in a variety of ways to suggest possible titles. Compared to writing the story itself, coming up with the title may seem a minor issue, not worth the five kilowords just spent on it. But writers do not struggle over the title because titles don’t matter.

Contests

Old wine in new bottles. Pick a book or story you liked, and suggest an alternate title for it. John Wright says he “would have changed I Will Fear No Evil into "Brain-Swapping Lust Ghost of Venus or something.” And Foundation he would have called, Mind-Masters of the Dying Galactic Empire. What titles can you come up with? You can

a) suggest serious alternatives to titles you thought didn’t quite make it, or

b) try to out-gonzo Mr. John C. Wright.

Note to the Anonymoi. If you are one of the Anonymoi, that is, not registered on either LiveJournal or the alternate Blogspot site, make up a name – even your own – to sign your contribution, lest we confuse one Anonymous with another.

The prize… Well, there ain’t no prize. We don’t need no stinking prizes. It’s an honor just to participate.

The First Shall be Last

The title may be the first thing the reader sees, but it might be the last thing the writer sees.

Other writers, however, don’t come up with a title until the story is complete or near enough. For many, the final title is a struggle or, in Michael Swanwick’s case, “a hideous struggle.” His working title for the award-winning Stations of the Tide was… Science Fiction Novel, and it “came perilously close to being published as Sea-Change, being saved from this fate on literally the last day the title could have been changed.” Nancy Kress seldom has even a working title while she writes, and often struggles with the titles afterward. “I have no good titles that I chose myself,” says Nancy Kress, “with a few exceptions. Otherwise, I grab the sleeve of any one I can and say ‘Will you read this and title it for me?’” Geoffrey Landis says, “I usually struggle for a while and then give up and give it something obvious.” Ed Lerner tells us, “I generally go through several titles before one sticks.” For Harry Turtledove, it is “almost always a struggle” with occasional exceptions. His original title for "The Pugnacious Peacemaker" (a sequel to Sprague deCamp's “Wheels of If") was "Making Peace with the Land of War,” which he thinks was perhaps too long and obscure.

On the other hand, Juliette Wade says that while she has struggled once or twice with titles, she usually doesn’t have that much trouble, especially with her Allied Systems stories. For Bill Gleason, titles “don’t come easily, but it hasn't really been a struggle either.” I would have to put myself in this category, too. I often have more titles than stories. Or perhaps more accurately, where some folks have working titles, I have working stories; that is, story ideas, concepts, and such to which I’ve given a title/label and placed on a to-do list. A story entitled “On the Shore of the Endless Ocean” has been lying doggo for some years now in a state of I-sorta-know-what-it-will-be-about-but-not-quite.

Jack McDevitt swings both ways. He has occasionally spent an entire year trying to come up with a title and still ended with one that was unsatisfactory. “The Hercules Text was my first novel,” he says. “The book, I’m happy to say, was considerably better than the title, which made it sound like a school assignment.” But he had other titles, like A Talent for War, before he had even the germ of a plot to go with it.

Authors’ Favorites.

Whether the result of hideous struggle or happy inspiration, whether captured ahead of time or only after the story has revealed its name, a title sometimes hits that sweet spot. I asked the Committee of Correspondence which titles of their own they were especially pleased with.

Michael Swanwick is partial to two. The first is “Mother Grasshopper,” a story set on a planet-sized grasshopper, because, he says, only the second word is literal. “Mother” is figurative. “It refers to no thing or fact that you can find in the story,” he says, “but it involves the reader in interpreting the story’s meaning and adds to its depths. That title came about in the usual, sweaty, making-lists-and-cursing way.” He also likes “‘Hello,’ Said the Stick” and defies anyone to turn to that page of Analog and not read the first paragraph or two, just to see what the heck is going on.” Definitely an arresting title.

For Geoffrey Landis a favorite title is his recent Nebula-nominated story "Sultan of the Clouds." “It seems appropriate for the story,” he says, “yet somewhat lyrical.”

Juliette Wade thinks "Cold Words" was her most effective title because “it gave good intellectual guidance, captured the core of the story, and also had a lot of emotional content and potential for rousing curiosity.”

Ed Lerner is partial to his "Dangling Conversations," a novelette dealing with SETI. He says it “fits the story (because radio-based comm between stars is going to be slow, with years between question and answer), sounds intriguing (who's talking, and what's been left in abeyance?), and avoids giving away anything critical.” He has no idea how he came up with it. It just popped out of his subconscious.

Bill Gleason lifted "Into That Good Night" from a poem by Dylan Thomas. But he believes it especially fitting because it hints at both the action of the story and one of its major themes.

Harry Turtledove likes In the Presence of Mine Enemies, The Man With the Iron Heart, and "Lee at the Alamo" (upcoming on tor.com) “They fit the stories and seemed tolerably memorable.”

For Jack McDevitt, a favorite is The Engines of God. “It implies the cosmic power which constitutes the threat in the novel, and it also has an epic feel, perfect for the novel that introduced the omega clouds and Priscilla Hutchins. Time Travelers Never Die works well also, depicting the relatively light tone of the novel, and the central point that you always know when to find a time traveler, so she is never really dead.”

Nancy Kress likes "Out of All Them Bright Stars" and "The Price of Oranges" because she chose them herself!

John Wright says his titles are “about average as titles go.” He offers two novels: Null-A Continuum has the unusual term ‘Null-A,’ and since the first book dealt with the world of Null-A, and the second with a galactic war, he upped the ante to ‘Continuum,’ which “has that nice shiny science fictional ring to it. Sounds all technical and stuff.” He also likes Last Guardian of Everness. It has an unusual or invented word, everness, “which conveys a hint of eternity.” And “there is an irony or an oddity in the title, since if the ‘Everness’ (whatever that is) lasts forever, how can there be a last one of them? The word ‘Guardian’ is also mildly archaic, and tells the reader this is a fantasy.” Finally, ‘Last’ conjures that sense of melancholy so common to fantasy. But his all-time favorite is a novella, “One Bright Star to Guide Them.” “That title to me captures an eerie magic hard to describe.”

I asked them, too, which titles by other writers struck them as most effective.

Michael Swanwick thinks Terry Bisson’s “Bears Discover Fire” is deceptively simple, inherently interesting, easy to remember, and rouses the reader’s curiosity. “And it fits the story perfectly. You can’t do better than that.”

Geoffrey Landis tells us that Roger Zelazny was good with titles. Creatures of Light and Darkness resonates with him. (The title appealed to me, too, and I bought the book on no other basis than that. Note the contrast between light and darkness and the suggestive ambiguity of creatures. )

Juliette Wade said that it was hard for her to pick a favorite title in others' work, but says “I do always enjoy titles which have unusual grammatical structure, though overall I'd say content is more important. I like titles which are a bit mysterious.” She named my own "Where the Winds are All Asleep" and Ursula LeGuin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, which she found “nicely intriguing.”

Ed Lerner likes A Fire Upon the Deep and A Deepness in the Sky, both by Vernor Vinge. Both titles are “striking, fit their stories well, and avoid giving away any plot.”

For Harry Turtledove, three satisfactory titles that spring to mind are For Whom the Bell Tolls (Hemingway), Stranger in a Strange Land (Heinlein), and Lest Darkness Fall (deCamp).

Jack McDevitt says that two of his favorite titles are Glory Road (Heinlein) and “Out of All Them Bright Stars” (Kress). “I’d buy either book without knowing anything else about them, even their authors.” He’s not sure why. “Other people’s titles just blow me away. Or don’t.”

John Wright likes The Dying Earth (Jack Vance). “These two words are quite ordinary taken separately, and forgettable, whereas together immediately conjure that sense of cosmic deeps of time which is the heart of science fiction, and, at the same time, that haunting sense of melancholy which is the heart of fantasy. It immediately sets the reader to wonder: we have seen creatures die, but the Earth?” Regarding Well at the World’s End (William Morris), he defies anyone to come up with “a title more rich with the echoes of the sounds of the horns of elfland dimly blowing.”

Going out of genre, some titles I’ve especially liked are the thriller As the Wolf Loves Winter, by David Poyer, and the detective novel When the Sacred Ginmill Closes, by Lawrence Block. The former suggests something of the bitter cold and the predatory characters in the story; the latter suggests a sea-change in the characters’ lives. I bought both books on little more than the title, and you can’t ask more of a title than that. I have also found Cordwainer Smith (“The Colonel Came Back from the Nothing-at-All"), Harlan Ellison (“‘Repent, Harlequin!’ Said the Ticktockman”), and R.A. Lafferty (“The Groaning Hinges of the World”) to be producers of astonishing titles. But be careful with astonishing titles if you don’t have an astonishing story to go with it.

Where Do You Get Your Titles From?

Titles crawl out from under a variety of rocks, even when we have to turn the rock over with a stick. Four sources are the four dimensions of a story: setting (or milieu), theme (or idea), characters, and plot (events or “peak situations”).

1. Setting: A book can take its title from the milieu in which it takes place. This can be literal or metaphorical. Examples include: Ringworld (Niven). “The Gate of the Hundred Sorrows” (Kipling). Eternity Road (Jack McDevitt). Venus (Ben Bova). Red Mars (Kim Stanley Robinson). “Gibraltar Falls” (Poul Anderson). Or my own Eifelheim. Because SF often involves strange milieus, and readers are attracted to futuristic or alternate settings, this is a popular class of title.

2. Idea: The title can be a word or phrase that captures the essential theme of the story. This is probably the most popular category of titles. The idea may be described directly, as in the mainstream book Room at the Top (John Braine) or by means of a double-meaning, as in The Bookman’s Wake (John Dunning) or a paradox, as in Casualties of Peace (Edna O’Brien). Examples in SF include: Thrice Upon a Time (James Hogan), Mission of Gravity (Hal Clement) or Dark as Day (Charles Sheffield).

3. Character: The name or description of a key character, either directly naming the individual (or group of individuals) or by using a metaphor. Examples include: The Odyssey (Homer), David Copperfield (Dickens), and Lolita (Nabokov). Titles taken from protagonist names are less common in SF, but we have Kinsman (Bova), Starman Jones (Heinlein), and of course Conan the Barbarian (Robert E. Howard). Metaphorically, we have character-driven titles in The Fellowship of the Ring (Tolkein), The Revolving Boy (Gertrude Friedberg), and “The Man Who Came Early” (Poul Anderson).

4. Event: A name or phrase that captures some peak situation or occurrence within the story. Typical examples include “The Madness of Private Ortheris” (Kipling), The Fall of the Towers (Samuel R. Delany), and “The Green Hills of Earth” (Heinlein). The last refers to a poem composed by the character Rhysling during the story crisis. Mars Crossing (Landis) and “Nano Comes to Clifford Falls” (Nancy Kress) are summaries of their respective plots.

Poking the Muse

There are several ways of jogging the creative juices to emit a title from the brain-pan.

1. Simple description. A nanotech story of mine was called “Werehouse” because that was where people went to be illegally transformed into animals. Such titles often take the form Noun (The Syndic, C.M. Kornblunth)Adjective Noun, (The Maltese Falcon, Dashiell Hammett),Noun Noun (Dinosaur Beach, Keith Laumer),Noun of Noun, ("Flowers of Aulit Prison," Kress)and so forth. For place-titles, try tossing prepositions like At, In, On, To, etc. while you ponder your story and you might come up with To the Tombaugh Station (Wilson Tucker), “On Greenhow Hill” (Kipling), In the Country of the Blind (yours truly).

2. A line from the story. Search the text of your story for a line that seems to encapsulate the story. That was the origin of my in-progress novella, “Places Where the Roads Don’t Go.” It was also how Nancy Kress found titles for "Out of All Them Bright Stars" and "The Price of Oranges," and R.A. Lafferty obtained “Camels and Dromedaries, Clem.”

3. Famous (or not so famous) quotations. Make a list of key words from each of the four categories mentioned above and go to Bartlett’s to see if there’s a quotation that illuminates the story. Shakespeare and the Bible have been overused, though there is a good reason why people fish there for pithy quotes. But why not look for the road less traveled and try Matthew Arnold, Algernon Swinburne or Lewis Thomas? This was how I found “Where the Winds Are All Asleep,” “Great, Sweet Mother,” and “The Common Goal of Nature.” I also mined quotes for “Dawn, and Sunset, and the Colours of the Earth” and “The Clapping Hands of God.” Harry Turtledove took “In the Presence of Mine Enemies” from Psalms 23:5 – and “The Road Not Taken” from Frost. Bill Gleason, as already mentioned, used Dylan Thomas. Lawrence Block’s Small Town comes from a passage by John Gunther – and refers to New York City, which makes for an arresting contrast.

4. Pairings. BruteThink is a creative thinking tactic. It consists of finding two words that are individually contrasting but which in combination capture the story. From the list of key terms suggested by the four categories, look for pairs that clash. Charles Sheffield’s Dark as Day, for example; or Nancy Kress’ “Flowers of Aulit Prison.” Flowers + Prison? What’s that all about? Another contrast, which Jack McDevitt has mentioned, is to join a physical thing with an abstraction, as in his Infinity Beach, Nancy Kress’ Probability Moon, or Kipling’s “Dayspring Mishandled.”

5. Crossing categories. A good title might suggest itself by pairing key words from different categories. For example, an event and a place, as in Kipling’s “The Taking of Lungtungpen” or Dashiell Hammett’s “The Gutting of Couffignal”; or a character and a place, as in de Camp’s Conan of Cimmeria. Try each pairing and see what comes up: “The Character of Setting,” “Of Idea and Character,” and so on.

6. Random matches. Mozart used to roll a trio of dice to suggest chord progressions. He would take the randomly-generated chords and see if they inspired his creative juices. If not, he would keep rolling until something came up. The writer can do the same thing, taking words from the list of key words purely at random and rubbing them against one another to see if any of them strike sparks.

Since I know my own titles best, I can offer a few comments on several stories in various stages of (in)completion: “Places Where the Roads Don’t Go” An idea-title. The story began with a different title, but partway through one of the characters said, “but there are places where the roads don’t go.” Because it encapsulated the entire theme of the story and the relationship between the two main characters, it was forthwith promoted to title. “Buried Hopes” This follows Jack McDevitt’s dictum of pairing something physical (Buried) with something abstract (Hope). It was the original working title for the first item, above. Never waste a title, sez I! Now it is part of a story cycle that also includes “Remember’d Kisses” and “Captive Dreams,” so it employs parallel Adjective Noun structure. It also has a second meaning that becomes clear near the end. “Hopeful Monsters” This was a title that existed before there was a story plot to go with it, only a theme or idea. The reference is to Goldschmidt’s “hopeful monster theory” that evolutionary change may involve, not incremental Darwinian steps, but big leaps (mutants, ‘monsters’ in the technical sense) that have great possibilities (hence, ‘hopeful’). The story applies that idea to genetic engineering intended to optimize human beings. There is a nice contrast between the two words and a double meaning lurking in the story. “Elmira, 1895” This is a place title; and involves a fictional visit by Rudyard Kipling, then living in Vermont, to Samuel Clemens in Elmira, regarding a manuscript that Clemens has written and some newspaper stories that Kipling had clipped. A title like this suggests a tight focus on a single event at a particular time and place. “Mayerling” Another place-title for an alternate history centered on Crown Prince Rudolf and his hunting lodge at Mayerling, near or around which numerous other characters – Strauss Jr., Freud, Klimt, et al. – have also lived, hiked or picnicked. In addition, I have portions of two potential novels: The Chieftain is a character-title referring to David O’Flainn, chief of the Sil Maelruain ca. 1224, in a medieval fantasy. Since the basic plot is already in the Annala Connaughta and a practice version of the whole thing, written in college, sits in a box beside me, there is actually some hope of whapping it into shape. The title is appropriate because the character of the clan chieftain is the focus of the story. The Shipwrecks of Time is from a quotation by Francis Bacon about the haphazard nature of surviving antiquities. I saw it in a chapter quote in one of Jack McDevitt’s Alex Benedict novels and I began thinking about a story in which bits and pieces of haphazardly surviving data gradually comes together to... Well, there are all sorts of shipwrecks, aren't there? A Note on Series

Stories or novels in a series present an additional challenge. They are often expected to carry some sort of commonality. Each of John D. MacDonald’s Travis McGee books has a color in the title; as does Kim Stanley Robinson’s Martian trilogy. The Cliff Janeway novels of John Dunning all have “booked” or “bookman” in the title. My own Firestar series had the word “star” in each of the titles. Nancy Kress did the same with her Sleepless books and her Probability series. Ed Lerner and Larry Niven included the phrase "...of Worlds" in each book of their Fleet of Worlds series.

But this is by no means a requirement. Neither Jack McDevitt’s Priscilla Hutchins novels nor his Alex Benedict novels have “marker” titles. Neither do my own Spiral Arm books. Lawrence Block uses a title pattern for his Burglar books (“The Burglar Who….”) but not for his Matthew Scudder books. However, a title pattern is a choice that you might keep in mind if you have a series.

SummaryWhile the title is not the only gateway into a book or story, it is still important to stir the reader’s interest with a good title. Novels are often helped by the cover art, but magazine stories are not. A good title should be i) arresting, ii) suggestive, and iii) challenging. “Arresting” means the use of words or phrases that catch the attention: sometimes neologisms or “SF” words, the use of “strange pairs” like contradictory terms or physical+abstract, or by using unusual grammar. “Suggestive” means a title that tells the reader something about the story without revealing too much about it. It ought to hint at whether the story will be SF, fantasy, or something else, tell us if the story will be serious or comic, intended for mature or YA readership, etc. A great title for one could be terrible for another. “Challenging” means that the title may have hidden meanings or a significance that does not become clear until after the story has been read. Quotations or allusions, double meanings, and the like are useful for this purpose. Titles can be short or long, straightforward or elaborate. They can be found in a variety of ways: i) from the four dimensions of a story – setting, theme, character, and/or plot events;ii) from quotations within the story itself;iii) from apposite external quotations. Lists of key words expressing setting, theme, character, and/or plot events can be “mixed and matched” in a variety of ways to suggest possible titles. Compared to writing the story itself, coming up with the title may seem a minor issue, not worth the five kilowords just spent on it. But writers do not struggle over the title because titles don’t matter.

Contests

Old wine in new bottles. Pick a book or story you liked, and suggest an alternate title for it. John Wright says he “would have changed I Will Fear No Evil into "Brain-Swapping Lust Ghost of Venus or something.” And Foundation he would have called, Mind-Masters of the Dying Galactic Empire. What titles can you come up with? You can

a) suggest serious alternatives to titles you thought didn’t quite make it, or

b) try to out-gonzo Mr. John C. Wright.

Note to the Anonymoi. If you are one of the Anonymoi, that is, not registered on either LiveJournal or the alternate Blogspot site, make up a name – even your own – to sign your contribution, lest we confuse one Anonymous with another.

The prize… Well, there ain’t no prize. We don’t need no stinking prizes. It’s an honor just to participate.

Published on July 07, 2011 07:23

The Craft

Entitlement, Part I

Titles. What we know first about anything is its being, its existence; and so we give it a name so we can talk about it. What we know first about any story or novel is its title. Before the reader knows the names of the characters, he knows the name of their story. In fact, the latter may be a precondition to the former, since a bad title can drive readers off. Well-known writers may get by with so-so titles. Their books will sell regardless. And some readers will buy anything in their favorite genre, and again the title will not be the deciding factor. But for the most part, a book will sit among other books, each clamoring for attention. The browsing reader, who is neither fan nor fanatic, will pick up one and not the other.

Why? The title, the cover, and the opening passages. Now short stories seldom have covers, and even for novels the cover is usually not controlled by the writer. So let’s consider titles, as such. We will consider the opening in a later post at some uncertain date.

Thanks and Acknowledgments. I was assisted in this essay by helpful inputs from the Committee of Correspondence. They include old hands and neo-pros, hard SF and fantasy, novelists and short fiction writers. However, they are not to blame for what I did with their comments. Jack McDevitt, Nebula-winning author of the popular Alex Benedict and Priscilla Hutchens novelsBill Gleason, a neo-pro with several short stories in ANALOGNancy Kress, multiple Hugo and Nebula winning author and one-time fiction columnist for Writer's DigestGeoff Landis, author of Crossing Mars and winner of both Hugo and Nebula awards for short fiction.Ed Lerner, author of multiple novels including the Fleet of Worlds series with Larry NivenMichael Swanwick, author of the Nebula-winning Stations of the Tide and numerous fine short fictionHarry Turtledove, regarded as the master of alternate history, has won the Hugo and Nebula for his short fictionJuliette Wade, a neo-pro with several noted short stories hinging on linguistics and culture.John C. Wright, author of the Golden Age series and Chronicles of Chaos and the forthcoming Count to a TrillionWhat are the Qualities of a Good Title?

In his book Twenty Problems of the Fiction Writer, John Gallishaw addresses the title in his chapter "How to Make a Story Interesting." Now the ultimate Beginning of any story, that part which comes at once to the reader's attention, is the title. From the point of view of interest, a good title is, then, your first consideration in arousing the reader's interest. The title should be arresting, suggestive, challenging. Kipling's "Without Benefit of Clergy" has all these requirements. So has Barrie's "What Every Woman Knows." So has Henry James's "The Turn of the Screw." So has O. Henry's "The Badge of Policeman O'Roon." So has John Marquand's "A Thousand in the Bank." ..... You may say definitely that the first device for capturing interest is in the selection of a title which will cause the reader to pause, which will whet his curiosity.

1. Arresting. What causes the reader to pause is an arresting title. The reader wonders what the heck is this about? Especially arresting titles include When the Sacred Gin Mill Closes (Lawrence Block); “Time Considered as a Helix of Semi-Precious Stones” (Samuel Delaney), “Out of All Them Bright Stars” (Nancy Kress), or even my own “Timothy Leary, Batu Khan, and the Palimpsest of Universal Reality.” Harry Turtledove recently submitted a story titled "It's the End of the World As We Know It, and We Feel Fine."

Of course, arresting titles need not be elaborate (although a review of Hugo and Nebula nominees reveals something of a fashion for this in SF). The Maltese Falcon is short, descriptive, and carries a hint of the exotic. Niven and Pournelle’s Lucifer’s Hammer and Greg Bear’s The Forge of God are effective for the same reason. John C. Wright would like a title to be “brief, striking or memorable to the reader, and to tell the reader immediately what genre the book is. If the title includes an odd or invented word, or a combination of words not normally found together, this is better still.”

A good way to arrest the attention is to evoke imagery. “I want graphics,” writes Jack McDevitt. “I want a visual, connected with an emotional impact, or at least an insight into where the narrative is going.” He suggests joining a physical object with an abstraction. For example, his own Eternity Road (which is one of my own favorites) joins the physical Road with the abstraction of Eternity and “takes on the changes brought about by the passage of time.”

Because genre readers like to read genre, John Wright suggests the title include words like star or world or otherwise suggest SF and offers The Star Fox (Poul Anderson), Rocannon’s World (Ursula K. LeGuin), Forbidden Planet (“W.J. Stuart” (Philip MacDonald)) and World of Null-A (A.E. VanVogt) as examples. The last-named contains the mysterious, and therefore arresting neologism null-A. He also cites the hard-to-find Harry Potter and the Sky-Pirates of Callisto vs. the Second Foundation.

Keep in mind that titles must be reader-appropriate. A young boy may be intrigued by Space Captives of the Golden Men (Mary E. Patchett) – I was. It was the first SF book I read. – but more mature readers often prefer titles with greater subtlety.

2. Suggestive. Now, if arresting the reader’s attention were the only quality for a title, every story would be entitled "Secret Sex Lives of Famous People” or perhaps Golden Bimbos of the Death Sun. Indeed, William Sanders once quipped about a certain publisher that he was the sort who would change the title of the Bible to War Gods of the Desert. Michael Swanwick writes that the title “should suggest that something really interesting is happening in the story.”

The simplest way to do this is with a title that captures the essence of the story. Heinlein's Tunnel in the Sky is not only arresting (a tunnel in the sky?) but suggests what the story will be about. William Trevor’s mainstream story “The General’s Day” chronicles the banal events of one day in the life of a retired British general (with a devastating ending).

However, “suggestive” does not mean flat description. Suggestive means to hint, to adumbrate something about the story. i) Not too revealing. Ed Lerner cautions that the title should avoid giving away anything critical in the story. Geoff Landis concurs: “Something evocative and also fitting for the story, but doesn't give away key points of the story.” The art of story-telling is to present events to the reader in an order that produces the best artistic effect. So Odysseus Comes Home Late would be a bad title, even though it is correctly descriptive.

ii) Metaphoric or symbolic. Edmund Hamilton's The Haunted Stars concerns the discovery of an abandoned alien base on the Moon, and the imagery of vanished peoples and long-ago deeds pervades the book. John Brunner’s The Shockwave Rider concerns a protagonist who “surfs the wave” of Future Shock. Juliette Wade tells us that her titles grow out of thematic ideas or important recurring concepts in the story, like the title of her novel, For Love, For Power. Nancy Kress also admires titles that work on both a plot and a thematic level, like LeGuin's "Nine Lives." Sara Umm Zaid entitled her 2001 Andalusia Prize story “Making Maklooba.” Maklooba is a Palestinian dish in which the bowl is turned upside down on the tray and removed. If the maklooba is good, the food retains the shape of the bowl. The dish is used as a metaphor for a woman whose life has been turned upside down and emptied by the death of her son and its subsequent political exploitation. John Dunning used the title Two O’Clock, Eastern Wartime for a tale of murder set in the days of live radio and World War II. Kipling’s “The Gate of the Hundred Sorrows” is likewise suggestive while also being descriptive – it is the name of an opium den where the main story takes place.

iii) Atmosphere. The title might also be suggestive by conjuring an atmosphere. For science fiction, that might be a title that conveys a sense of “cosmic deeps of time.” For fantasy, one that conveys a “haunting sense of melancholy.” In fact, Roger MacBride Allen wrote The Depths of Time, which surely conveys that sense of cosmic deeps of time! The sequel The Ocean of Years succeeds by pairing ocean with years. Edmond Hamilton’s City at World’s End does a little of both, hinting at depths of time and a sense of melancholy.

3. Challenging. You can also catch the reader’s attention with a title that challenges him. An odd word might be used – Null-A, Dirac Sea, Feigenbaum Number, and so on. Ed Lerner suggests that the relevance of the title might become evident only after the reader has finished the story and reflects on it.

Juliette Wade likes titles that can have more than one meaning, such as her own “Cold Words,” which is both literal and metaphorical. John Dunning’s detective title The Bookman’s Wake seems to mean one thing during the course of the story, but takes on another meaning at the end. Patrick O’Brian’s naval novel The Surgeon’s Mate also carries two meanings. Sara Umm Zaid’s “Village of Stones” refers not only to the material construction of the dwellings, but to the enthusiasm with which the villagers stone a young girl who has dishonored her family. We might call these double-take titles.

But be careful. A title may be so challenging that the prospective reader scratches his head in bewilderment and goes on to another book or story. Long, obscure titles could tip over into a perceived pretentiousness. Apparent metaphors could fail to deliver. James Blish’s The Warriors of Day had a nice title, but it turned out to be prosaic: actual warriors from a planet called Day. Double meanings could be unintentional. “The Iron Shirts,” my alternate history story for tor.com, was originally titled “Iron Shirts” until it was pointed out that “iron” might be read as a verb!

It’s Got a Good Beat. A fourth factor that relates to the form rather than the matter of the title is its rhythm or meter. Critic and author Greg Feeley once said of my own title The Wreck of “The River of Stars” that what was arresting about it was how the regular beat of the phrase contrasted with the chaos and irregularity implicit in the words wreck, river, and stars. G.K.Chesterton was fond of alliteration in many of his Father Brown mysteries: “The Doom of the Darnaways,” “The Flying Fish,” and so forth. Try saying aloud such titles as “The Last Hurrah of the Golden Horde” (Norman Spinrad), “The Sorrow of Odin the Goth” (Poul Anderson), The Stone That Never Came Down (John Brunner), To Your Scattered Bodies Go (Philip José Farmer). Each has a rhythm that makes it attractive. But a short, punchy title can have its own charms: Warlord of Mars (Burroughs), Jumper (Steven Gould), Star Gate (Andre Norton).

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

A good title may mask a bad story. I’ve mentioned The Warriors of Day. John Wright mentions Gormenghast (Mervyn Peake), which is an unusual and arresting word that “sticks in the memory as something gigantic and ghastly.” But he does not care much for the story itself.

Similarly, a good story may have a poor title – and thrive regardless. Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen (H. Beam Piper) is a worse title than the original novelette “Gunpowder God.” Even the blockbuster Dune, which John Wright says “conjures up an image of a small hillock of sand at the beach,” had better titles in magazine serial form; viz., “Dune World” and “The Prophet of Dune.” However, each of these tales already had followings in the magazines, and the authors themselves were popular.

Next

Part I has looked at what the title is – its matter and form, if you will. Part II will look at how a title comes about – its efficient cause.

Contest

Our favorite titles. Okay, dear readers, if there are any. Your assignment is to share book or story titles that you found effective, memorable, or resonant, regardless of the quality of the story itself. That is, titles that lured you to buy the book or read the story, or which have stuck with you afterward. What about the title enticed you? What made it work. You don’t have to restrict yourself to SF titles, either.

Note to the Anonymoi. If you are one of the Anonymoi, that is, not registered on either LiveJournal or the alternate Blogspot site, make up a name – even your own – to sign your contributions, lest we confuse one Anonymous with another.

Titles. What we know first about anything is its being, its existence; and so we give it a name so we can talk about it. What we know first about any story or novel is its title. Before the reader knows the names of the characters, he knows the name of their story. In fact, the latter may be a precondition to the former, since a bad title can drive readers off. Well-known writers may get by with so-so titles. Their books will sell regardless. And some readers will buy anything in their favorite genre, and again the title will not be the deciding factor. But for the most part, a book will sit among other books, each clamoring for attention. The browsing reader, who is neither fan nor fanatic, will pick up one and not the other.

Why? The title, the cover, and the opening passages. Now short stories seldom have covers, and even for novels the cover is usually not controlled by the writer. So let’s consider titles, as such. We will consider the opening in a later post at some uncertain date.

Thanks and Acknowledgments. I was assisted in this essay by helpful inputs from the Committee of Correspondence. They include old hands and neo-pros, hard SF and fantasy, novelists and short fiction writers. However, they are not to blame for what I did with their comments. Jack McDevitt, Nebula-winning author of the popular Alex Benedict and Priscilla Hutchens novelsBill Gleason, a neo-pro with several short stories in ANALOGNancy Kress, multiple Hugo and Nebula winning author and one-time fiction columnist for Writer's DigestGeoff Landis, author of Crossing Mars and winner of both Hugo and Nebula awards for short fiction.Ed Lerner, author of multiple novels including the Fleet of Worlds series with Larry NivenMichael Swanwick, author of the Nebula-winning Stations of the Tide and numerous fine short fictionHarry Turtledove, regarded as the master of alternate history, has won the Hugo and Nebula for his short fictionJuliette Wade, a neo-pro with several noted short stories hinging on linguistics and culture.John C. Wright, author of the Golden Age series and Chronicles of Chaos and the forthcoming Count to a TrillionWhat are the Qualities of a Good Title?

In his book Twenty Problems of the Fiction Writer, John Gallishaw addresses the title in his chapter "How to Make a Story Interesting." Now the ultimate Beginning of any story, that part which comes at once to the reader's attention, is the title. From the point of view of interest, a good title is, then, your first consideration in arousing the reader's interest. The title should be arresting, suggestive, challenging. Kipling's "Without Benefit of Clergy" has all these requirements. So has Barrie's "What Every Woman Knows." So has Henry James's "The Turn of the Screw." So has O. Henry's "The Badge of Policeman O'Roon." So has John Marquand's "A Thousand in the Bank." ..... You may say definitely that the first device for capturing interest is in the selection of a title which will cause the reader to pause, which will whet his curiosity.

1. Arresting. What causes the reader to pause is an arresting title. The reader wonders what the heck is this about? Especially arresting titles include When the Sacred Gin Mill Closes (Lawrence Block); “Time Considered as a Helix of Semi-Precious Stones” (Samuel Delaney), “Out of All Them Bright Stars” (Nancy Kress), or even my own “Timothy Leary, Batu Khan, and the Palimpsest of Universal Reality.” Harry Turtledove recently submitted a story titled "It's the End of the World As We Know It, and We Feel Fine."

Of course, arresting titles need not be elaborate (although a review of Hugo and Nebula nominees reveals something of a fashion for this in SF). The Maltese Falcon is short, descriptive, and carries a hint of the exotic. Niven and Pournelle’s Lucifer’s Hammer and Greg Bear’s The Forge of God are effective for the same reason. John C. Wright would like a title to be “brief, striking or memorable to the reader, and to tell the reader immediately what genre the book is. If the title includes an odd or invented word, or a combination of words not normally found together, this is better still.”

A good way to arrest the attention is to evoke imagery. “I want graphics,” writes Jack McDevitt. “I want a visual, connected with an emotional impact, or at least an insight into where the narrative is going.” He suggests joining a physical object with an abstraction. For example, his own Eternity Road (which is one of my own favorites) joins the physical Road with the abstraction of Eternity and “takes on the changes brought about by the passage of time.”

Because genre readers like to read genre, John Wright suggests the title include words like star or world or otherwise suggest SF and offers The Star Fox (Poul Anderson), Rocannon’s World (Ursula K. LeGuin), Forbidden Planet (“W.J. Stuart” (Philip MacDonald)) and World of Null-A (A.E. VanVogt) as examples. The last-named contains the mysterious, and therefore arresting neologism null-A. He also cites the hard-to-find Harry Potter and the Sky-Pirates of Callisto vs. the Second Foundation.

Keep in mind that titles must be reader-appropriate. A young boy may be intrigued by Space Captives of the Golden Men (Mary E. Patchett) – I was. It was the first SF book I read. – but more mature readers often prefer titles with greater subtlety.

2. Suggestive. Now, if arresting the reader’s attention were the only quality for a title, every story would be entitled "Secret Sex Lives of Famous People” or perhaps Golden Bimbos of the Death Sun. Indeed, William Sanders once quipped about a certain publisher that he was the sort who would change the title of the Bible to War Gods of the Desert. Michael Swanwick writes that the title “should suggest that something really interesting is happening in the story.”

The simplest way to do this is with a title that captures the essence of the story. Heinlein's Tunnel in the Sky is not only arresting (a tunnel in the sky?) but suggests what the story will be about. William Trevor’s mainstream story “The General’s Day” chronicles the banal events of one day in the life of a retired British general (with a devastating ending).

However, “suggestive” does not mean flat description. Suggestive means to hint, to adumbrate something about the story. i) Not too revealing. Ed Lerner cautions that the title should avoid giving away anything critical in the story. Geoff Landis concurs: “Something evocative and also fitting for the story, but doesn't give away key points of the story.” The art of story-telling is to present events to the reader in an order that produces the best artistic effect. So Odysseus Comes Home Late would be a bad title, even though it is correctly descriptive.

ii) Metaphoric or symbolic. Edmund Hamilton's The Haunted Stars concerns the discovery of an abandoned alien base on the Moon, and the imagery of vanished peoples and long-ago deeds pervades the book. John Brunner’s The Shockwave Rider concerns a protagonist who “surfs the wave” of Future Shock. Juliette Wade tells us that her titles grow out of thematic ideas or important recurring concepts in the story, like the title of her novel, For Love, For Power. Nancy Kress also admires titles that work on both a plot and a thematic level, like LeGuin's "Nine Lives." Sara Umm Zaid entitled her 2001 Andalusia Prize story “Making Maklooba.” Maklooba is a Palestinian dish in which the bowl is turned upside down on the tray and removed. If the maklooba is good, the food retains the shape of the bowl. The dish is used as a metaphor for a woman whose life has been turned upside down and emptied by the death of her son and its subsequent political exploitation. John Dunning used the title Two O’Clock, Eastern Wartime for a tale of murder set in the days of live radio and World War II. Kipling’s “The Gate of the Hundred Sorrows” is likewise suggestive while also being descriptive – it is the name of an opium den where the main story takes place.

iii) Atmosphere. The title might also be suggestive by conjuring an atmosphere. For science fiction, that might be a title that conveys a sense of “cosmic deeps of time.” For fantasy, one that conveys a “haunting sense of melancholy.” In fact, Roger MacBride Allen wrote The Depths of Time, which surely conveys that sense of cosmic deeps of time! The sequel The Ocean of Years succeeds by pairing ocean with years. Edmond Hamilton’s City at World’s End does a little of both, hinting at depths of time and a sense of melancholy.

3. Challenging. You can also catch the reader’s attention with a title that challenges him. An odd word might be used – Null-A, Dirac Sea, Feigenbaum Number, and so on. Ed Lerner suggests that the relevance of the title might become evident only after the reader has finished the story and reflects on it.

Juliette Wade likes titles that can have more than one meaning, such as her own “Cold Words,” which is both literal and metaphorical. John Dunning’s detective title The Bookman’s Wake seems to mean one thing during the course of the story, but takes on another meaning at the end. Patrick O’Brian’s naval novel The Surgeon’s Mate also carries two meanings. Sara Umm Zaid’s “Village of Stones” refers not only to the material construction of the dwellings, but to the enthusiasm with which the villagers stone a young girl who has dishonored her family. We might call these double-take titles.

But be careful. A title may be so challenging that the prospective reader scratches his head in bewilderment and goes on to another book or story. Long, obscure titles could tip over into a perceived pretentiousness. Apparent metaphors could fail to deliver. James Blish’s The Warriors of Day had a nice title, but it turned out to be prosaic: actual warriors from a planet called Day. Double meanings could be unintentional. “The Iron Shirts,” my alternate history story for tor.com, was originally titled “Iron Shirts” until it was pointed out that “iron” might be read as a verb!

It’s Got a Good Beat. A fourth factor that relates to the form rather than the matter of the title is its rhythm or meter. Critic and author Greg Feeley once said of my own title The Wreck of “The River of Stars” that what was arresting about it was how the regular beat of the phrase contrasted with the chaos and irregularity implicit in the words wreck, river, and stars. G.K.Chesterton was fond of alliteration in many of his Father Brown mysteries: “The Doom of the Darnaways,” “The Flying Fish,” and so forth. Try saying aloud such titles as “The Last Hurrah of the Golden Horde” (Norman Spinrad), “The Sorrow of Odin the Goth” (Poul Anderson), The Stone That Never Came Down (John Brunner), To Your Scattered Bodies Go (Philip José Farmer). Each has a rhythm that makes it attractive. But a short, punchy title can have its own charms: Warlord of Mars (Burroughs), Jumper (Steven Gould), Star Gate (Andre Norton).

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

A good title may mask a bad story. I’ve mentioned The Warriors of Day. John Wright mentions Gormenghast (Mervyn Peake), which is an unusual and arresting word that “sticks in the memory as something gigantic and ghastly.” But he does not care much for the story itself.

Similarly, a good story may have a poor title – and thrive regardless. Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen (H. Beam Piper) is a worse title than the original novelette “Gunpowder God.” Even the blockbuster Dune, which John Wright says “conjures up an image of a small hillock of sand at the beach,” had better titles in magazine serial form; viz., “Dune World” and “The Prophet of Dune.” However, each of these tales already had followings in the magazines, and the authors themselves were popular.

Next

Part I has looked at what the title is – its matter and form, if you will. Part II will look at how a title comes about – its efficient cause.

Contest

Our favorite titles. Okay, dear readers, if there are any. Your assignment is to share book or story titles that you found effective, memorable, or resonant, regardless of the quality of the story itself. That is, titles that lured you to buy the book or read the story, or which have stuck with you afterward. What about the title enticed you? What made it work. You don’t have to restrict yourself to SF titles, either.

Note to the Anonymoi. If you are one of the Anonymoi, that is, not registered on either LiveJournal or the alternate Blogspot site, make up a name – even your own – to sign your contributions, lest we confuse one Anonymous with another.

Published on July 07, 2011 06:41

July 1, 2011

This Day in History

The Glorious First

On this day in history, the first of July, 1863, the 153rd Pennsylvania Volunteers, "Northampton's Own," along with several thousand heavily armed friends, came to the aid of Buford's cavalry north and west of Gettysburg, Penn., where it took its stand on Blocher's Knoll, now called Barlow's Knoll. The 153rd was part of von Gilsa's brigade in Barlow's division of Howard's XI ("Dutch") Corps.

Barlow's Division was supposed to delay Ewell's advance down the Harrisburg Road long enough for von Steinwehr's Division to complete the fortifications on the fall back position on Cemetery Hill. His "advanced" position to the knoll is often regarded as a blunder; but may have been the best move available given the situation of the moment. Had the knoll been occupied by rebel artillery, it would have rolled up the right of I Corps and led to disaster. See here for an appraisal.

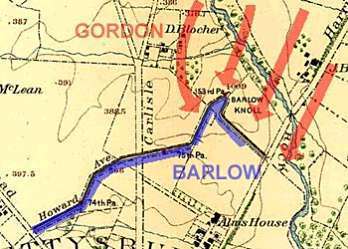

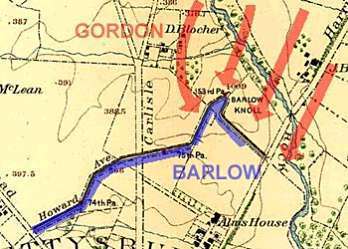

In the map to the left, note the position of the 153rd Penn. at the tip of the salient, ready to be enveloped on both sides.

In the map to the left, note the position of the 153rd Penn. at the tip of the salient, ready to be enveloped on both sides.

It should be noted that the 153rd first met battle at Chancellorsville, where it was positioned on the very far right of the US lines, and were first to be hit by Stonewall Jackson's surprise attack. Nonetheless, they fired one volley in good order before von Gilsa ordered them to withdraw lest they be enveloped.

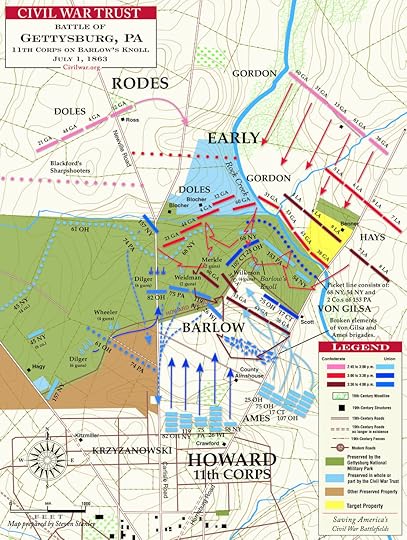

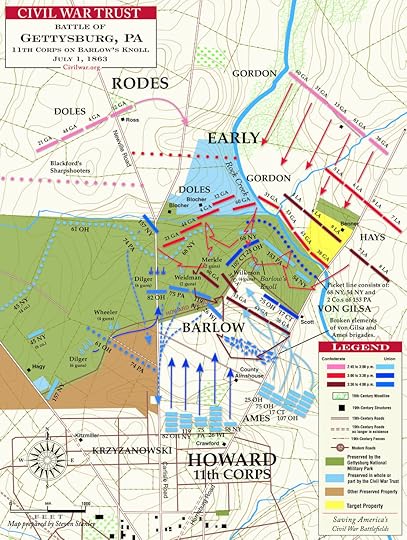

The development of the battle is shown in the map below. You will notice that Barlow had only a skirmish line to link up with (68th NY) because Krzyzanowski (known as "General Consonants" among the soldiers) was resting his men before bringing them into line. Had Krzyzanowski advanced a half hour earlier or Devin's cavalry not withdrawn from the right flank a half hour earlier, the position might have held a great deal longer than it did.

As it was, it was because of the battering that his corps took in this fight that Ewell decided it was not "practicable" to take Cemetery Hill later that day; so we may have the 153rd Pennsylvania to thank for at least some of that.

The 153rd is second from the right on Barlow's line, minus two companies forward as skirmishers.

The 153rd is second from the right on Barlow's line, minus two companies forward as skirmishers.

A monument to the 153rd stands on Barlow's Knoll today to mark the position of the regiment, photographed here by Margie:

When Barlow's and Ames' Divisions finally broke, they pulled back in disorder through town to retire on the previously planned fallback position on Culp's Hill, where they spent the second day.

The Bugler, as he is known locally, stands also atop the Civil War monument in Centre Square in Easton, PA:

On this day in history, the first of July, 1863, the 153rd Pennsylvania Volunteers, "Northampton's Own," along with several thousand heavily armed friends, came to the aid of Buford's cavalry north and west of Gettysburg, Penn., where it took its stand on Blocher's Knoll, now called Barlow's Knoll. The 153rd was part of von Gilsa's brigade in Barlow's division of Howard's XI ("Dutch") Corps.

Barlow's Division was supposed to delay Ewell's advance down the Harrisburg Road long enough for von Steinwehr's Division to complete the fortifications on the fall back position on Cemetery Hill. His "advanced" position to the knoll is often regarded as a blunder; but may have been the best move available given the situation of the moment. Had the knoll been occupied by rebel artillery, it would have rolled up the right of I Corps and led to disaster. See here for an appraisal.

In the map to the left, note the position of the 153rd Penn. at the tip of the salient, ready to be enveloped on both sides.

In the map to the left, note the position of the 153rd Penn. at the tip of the salient, ready to be enveloped on both sides. It should be noted that the 153rd first met battle at Chancellorsville, where it was positioned on the very far right of the US lines, and were first to be hit by Stonewall Jackson's surprise attack. Nonetheless, they fired one volley in good order before von Gilsa ordered them to withdraw lest they be enveloped.

The development of the battle is shown in the map below. You will notice that Barlow had only a skirmish line to link up with (68th NY) because Krzyzanowski (known as "General Consonants" among the soldiers) was resting his men before bringing them into line. Had Krzyzanowski advanced a half hour earlier or Devin's cavalry not withdrawn from the right flank a half hour earlier, the position might have held a great deal longer than it did.

As it was, it was because of the battering that his corps took in this fight that Ewell decided it was not "practicable" to take Cemetery Hill later that day; so we may have the 153rd Pennsylvania to thank for at least some of that.

The 153rd is second from the right on Barlow's line, minus two companies forward as skirmishers.

The 153rd is second from the right on Barlow's line, minus two companies forward as skirmishers. A monument to the 153rd stands on Barlow's Knoll today to mark the position of the regiment, photographed here by Margie:

When Barlow's and Ames' Divisions finally broke, they pulled back in disorder through town to retire on the previously planned fallback position on Culp's Hill, where they spent the second day.

The Bugler, as he is known locally, stands also atop the Civil War monument in Centre Square in Easton, PA:

Published on July 01, 2011 20:57

June 30, 2011

News from all over

from the WSJ Best of the Web, news from all over.