Rod Dreher's Blog, page 563

July 1, 2016

The Shrink Who Assists Exorcists

Writing in the Washington Post, psychiatrist and professor of psychiatry Richard Gallagher talks about his many years of helping Catholic exorcists. He believes that almost all cases of people who believe they are demonically possessed are examples of mental illness. But he absolutely believes that demons are real, and so is possession. Excerpts:

The priest who had asked for my opinion of this bizarre case was the most experienced exorcist in the country at the time, an erudite and sensible man. I had told him that, even as a practicing Catholic, I wasn’t likely to go in for a lot of hocus-pocus. “Well,” he replied, “unless we thought you were not easily fooled, we would hardly have wanted you to assist us.”

So began an unlikely partnership. For the past two-and-a-half decades and over several hundred consultations, I’ve helped clergy from multiple denominations and faiths to filter episodes of mental illness — which represent the overwhelming majority of cases — from, literally, the devil’s work. It’s an unlikely role for an academic physician, but I don’t see these two aspects of my career in conflict. The same habits that shape what I do as a professor and psychiatrist — open-mindedness, respect for evidence and compassion for suffering people — led me to aid in the work of discerning attacks by what I believe are evil spirits and, just as critically, differentiating these extremely rare events from medical conditions.

More:

But I believe I’ve seen the real thing. Assaults upon individuals are classified either as “demonic possessions” or as the slightly more common but less intense attacks usually called “oppressions.” A possessed individual may suddenly, in a type of trance, voice statements of astonishing venom and contempt for religion, while understanding and speaking various foreign languages previously unknown to them. The subject might also exhibit enormous strength or even the extraordinarily rare phenomenon of levitation. (I have not witnessed a levitation myself, but half a dozen people I work with vow that they’ve seen it in the course of their exorcisms.) He or she might demonstrate “hidden knowledge” of all sorts of things — like how a stranger’s loved ones died, what secret sins she has committed, even where people are at a given moment. These are skills that cannot be explained except by special psychic or preternatural ability.

I have personally encountered these rationally inexplicable features, along with other paranormal phenomena. My vantage is unusual: As a consulting doctor, I think I have seen more cases of possession than any other physician in the world.

And:

Most of the people I evaluate in this role suffer from the more prosaic problems of a medical disorder. Anyone even faintly familiar with mental illnesses knows that individuals who think they are being attacked by malign spirits are generally experiencing nothing of the sort. Practitioners see psychotic patients all the time who claim to see or hear demons; histrionic or highly suggestible individuals, such as those suffering from dissociative identity syndromes; and patients with personality disorders who are prone to misinterpret destructive feelings, in what exorcists sometimes call a “pseudo-possession,” via the defense mechanism of an externalizing projection. But what am I supposed to make of patients who unexpectedly start speaking perfect Latin?

One good point Gallagher makes in the piece is that there’s really no point in trying to convince those who are unconvince-able. The point is to help those who are suffering. Nearly 25 years ago, when I first met a Louisiana exorcist who became a friend (and who later was able to help our family deal with a poltergeist situation), I asked him how people found him, and once they found him, how they convinced themselves that he could help them.

“By the time they find me,” he said, “they don’t need to be convinced of anything.”

The friend who sent me a link to this article added:

Btw, the missionaries that I worked with in Uganda (all highly rational/educated Presbyterians) had stories like this…crazy things they’d witnessed.

Yep. In my experience, if you spend any time talking to people from Africa or Haiti, you will hear things that will blow your mind. On this blog last year, I wrote about talking to a Haitian taxi driver in Boston about voodoo and the demonic. I could tell by the name on his taxi license that he was Haitian, and he was listening to a Christian radio station, which is why I struck up a conversation with him about it. He spoke with real passion about all the college professors from Harvard, MIT, and Boston College he drove around in his cab who struck up the same conversations with him, and refused to believe him when he would talk about the things he had seen and heard in his life in Haiti. It frustrated him to no end. He wasn’t talking about stories he had heard, but things he had personally witnessed.

It is critically important not to be quick to believe. But it’s also critically important not to close your mind so tight that you cannot see what’s right in front of your nose. My friend Julie Lyons, a Dallas journalist who told me hair-raising stories of supernatural evil she saw in Africa, wrote a wild piece for D Magazine a couple of years ago about a pair of West Texas Protestant exorcists. You see this stuff with your own eyes, especially if you see it more than once (as I have), and it takes far more faith not to believe in its existence.

The Religion Of Sex

Sorry for the light posting today. I had to run into Baton Rouge this morning, and on the way back got caught in a massive traffic jam because of a gas spill. It took forever to get re-routed and back home. When I did return, I got the statistics for this blog’s readership for the past month, and the second quarter. We have had a record-setting year. For that, I thank you all.

Now, to business.

Sherif Girgis has a great piece in First Things about “Obergefell and the new sexual gnosticism.” Even if you celebrate same-sex marriage, it’s an important read to understand better why orthodox Christians believe as we do on this issue. Excerpts:

For decades, the Sexual Revolution was supposed to be about freedom. Today, it is about coercion. Once, it sought to free our sexual choices from restrictive laws and unwanted consequences. Now, it seeks to free our sexual choices from other people’s disapproval.

That’s a sharp turn—but it was inevitable. The ideals of the Sexual Revolution call for it: That is one lesson of the year that has passed since the Supreme Court imposed same-sex marriage in Obergefell v. Hodges. Most of Obergefell’s lay supporters were simply moved by concern for our LGBT neighbors—a worthy and urgent concern that the Church must be the first to heed, as Wesley Hill has beautifully reminded us. But the Court’s ruling itself depended on a broader sexual progressivism; and its cultural fallout has made clearer that sexual progressivism is illiberal. Absorb its vision of the human person wholesale, and you will soon conclude that social justice requires getting others to subscribe to that vision.

I’m so glad to read this put so well. It is at the core of the Sex & Sexuality chapter I’ve written for the Benedict Option book. It is impossible for orthodox Christians to separate sexuality from what the human person is. As Sherif explains, this is also the view of the Sexual Revolutionaries. The Sexual Revolution is best seen as like a different religion — a Gnostic one. He is not being snarky here, but explaining what this looks like from the point of view of traditional Christianity. I’m not going to quote it at too much length, but I strongly urge you to read it. He’s exactly right. Exactly.

More:

It’s not that the New Gnostics are an especially vindictive bunch. It’s that a certain kind of coercion is built into their view from the start. If your most valuable, defining core just is the self that you choose to express, there can be no real difference between you as a person, and your acts of self-expression; I can’t affirm you and oppose those acts. Not to embrace self-expressive acts is to despise the self those acts express. I don’t simply err by gainsaying your sense of self. I deny your existence, and do you an injustice. For the New Gnostic, then, a just society cannot live and let live, when it comes to sex. Sooner or later, the common good—respect for people as self-defining subjects—will require social approval of their self-definition and -expression.

This vision of the self explains otherwise novel and puzzling ideas: e.g., that you can’t be authentic without acting on your sexual desires, and that a physically healthy biological male might have been a woman all along. And its consequent illiberalism—the impulse to police dissent—explains an otherwise astonishing development. It explains how the status of absolute orthodoxy—which same-sex marriage advocates fought for decades to secure, and still achieved with astonishing speed—was transferred to transgenderism virtually overnight.

This is why we have the new blasphemy laws and heresy trials. It is why progressives and their right-wing fellow travelers on LGBT issues cannot recognize that equating homosexuality with race is a massive category error, and trads don’t understand why progressives don’t see what is obvious to us.

We are living by two different religions. But progressives, who are the new American mainstream on LGBT issues, don’t understand their view of what a human being is as essentially religious. They think it’s simply normal. But it is a religion: the New Gnosticism.

That’s why they will not stop until orthodox Christians are all thoroughly subjugated and dhimmified. The Sexual Revolution was more profound than the Reformation in its social and political effects, as we are now seeing. How well did life work out for Catholics in Protestant states in the Reformation era, and vice versa? This is why Christians can be as “winsome” as they like, but it won’t make one bit of difference. This is a religious war, and they are always the ugliest kind.

UPDATE: Earlier this week, I had meant to blog a link to Mary Eberstadt’s piece about the religion of secular progressivism, but it got lost in the shuffle. Read it! Excerpt:

The bedrock of contemporary progressivism can only be described as quasi-religious. The followers of this faith are, furthermore, Kantians regarding these beliefs, in the sense that the philosopher’s categorical imperative applies: Exactly like followers of other faiths, they believe both that they are right, and that people who disagree are wrong — and that those other people ought to think differently.

The so-called culture war, in other words, has not been conducted by people of religious faith on one side, and people of no faith on the other. It is instead a contest of competing faiths: one in the Good Book, and the other in the more newly written figurative book of secularist orthodoxy about the sexual revolution. In sum, secularist progressivism today is less a political movement than a church.

The Mission of The Mission

This is a post I had hoped never to have to write.

Our little Orthodox mission in West Feliciana, St. John the Theologian, is losing our priest after three and a half years, though it won’t officially close. Father Matthew Harrington and his family are returning home to Washington state. There are no plans to replace him. We can’t afford it. We have fewer members now than we did when we started. It was always going to be a long shot to establish Orthodox Christianity in a small Southern town, and it hasn’t happened. Yet, anyway. We don’t know what God has in mind.

It all happened quite suddenly, and out of the blue. Early last week, one of the church’s families, converts of three years, met with Father Matthew and told him that they were leaving Orthodoxy. Just like that. We had an emergency meeting of the congregation after liturgy this past Sunday to consider our options. But there really were no options to consider. We are down to three families (not counting the Harringtons) and a monk. Father Matthew was already making do on a pittance wage, but we were paying him the most that we could. The departing family promised to continue their tithe through year’s end, but that would be simply delaying the inevitable, Father Matthew figured. (I think he’s right.)

The Harringtons have been through so much since they’ve been here. Anna nearly died last summer giving birth to Irene, who has severe birth defects. Anna required 31 units of blood during the surgery. The human body contains between 10 and 11 units, meaning she bled out entirely nearly three times. Almost nobody survives that. But Anna lived, and so did that sweet baby! It was a miracle of God, said the doctors. Here is what Irene looks like today:

The Harringtons have been a clergy family in a minuscule mission parish. They had nothing. Perfect strangers — including many readers of this blog — opened their hearts and donated to a GoFundMe to help them pay for Irene’s care, which will be unending. In the past 11 months, you have given over $87,000. I can assure you that every single penny of that money has been scrupulously dedicated by the Harringtons to Irene’s care, and nothing but. Writing this, tears come to my eyes, thinking about how kind you all have been to that family, and that precious child.

Not many people know this, but the Harringtons learned from medical testing early on that Irene would have all these critical problems. She was unlikely to survive until birth, they said. And if she did, Anna stood a good chance of dying in the process. If ever there were a good case for termination, it was this one. But they said no. We are Christians, they said, and we welcome life, and whatever God sends.

He sent Irene, and he sent skilled doctors and nurses who saved her and saved her mother’s life. And he sent you all, with generous hearts, to help carry the financial burden. Thank you.

Over the last three and a half years, we have lost some people —

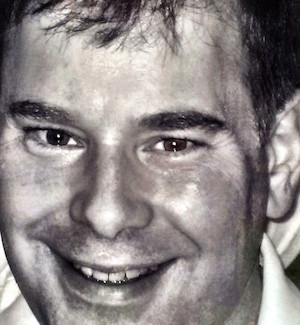

Jack Cutrer

original members and converts — to attrition. Orthodoxy is not an easy way of life. We gained a couple of dear converts who remain with us. But most grievously, we lost our beloved Jack Cutrer. His mother found him dead in his home on his sofa one morning. His prayer rope was in his hand. He passed away in prayer. He had been in and out of the hospital with kidney trouble, but he was sicker than he knew, sicker than any of us knew. He was only 41 years old. To say his passing was a shock is a gross understatement. Jack was there from the beginning. He read himself into the Orthodox Church years before we had a mission here. Jack was quiet and steady. We loved him more than we can say. I pass by his grave in the Starhill Cemetery almost every day, and think of him.

I grieve to think of what has become of Jack’s dream. I know I’m not the only one. There just aren’t enough of us to support a priest at this point. It was mostly a matter of money, but even if the heavens opened and rained dollars, that doesn’t change the blunt fact that we are so few. “We’re going to start coming to your church,” people said, and “What a great parish! We’re going to try to move to St. Francisville and join you.” If only half the people who told us these things had followed through, things might have turned out otherwise. But they didn’t, and they didn’t. There’s no changing the past.

The Lord giveth, and the Lord taketh away. Blessed be the name of the Lord.

Father Matthew taught us always to say, “Glory to God,” no matter what. So let me say a little about why I can say that through tears. In my book How Dante Can Save Your Life, I told his personal story, and how he helped lead me through the worst spiritual, emotional, and physical crisis of my life. Here, in a short passage from the book, is an example of his leadership:

After vespers one warm October night, I took my spiteful passions to Father Matthew in confession.

“I know my anger is wrong, and that’s why I’m in confession,” I said. “I realized, reading Dante this week, that I resented all of them for being happy without us. I know it’s not right, but I can’t get out from under this anger.”

I explained that I felt like I was living the prodigal son parable, but in this telling, the father is not running out to welcome the long-lost son but rather taking the side of the bitter older brother and not letting the younger one come through the gate.

“That’s tough,” Father Matthew said. “So what do you want?”

“I want justice. It’s not fair, the way they do me.”

“You want justice?” he said, chuckling. “What is justice? You have no right to expect justice. It’s nice if you get it, but if you don’t, that doesn’t release you from the commandment to love. The elder brother in the prodigal son story stood on justice, but his father stood on love.”

“Okay, but I think that if I do that, they’re going to win.”

“Win? This is a contest, Benedict?” he said. [Benedict is my chrismation name — RD] “I don’t know about you, but from where I sit, it doesn’t look to me like you’re winning much of anything by hanging on to all of this.”

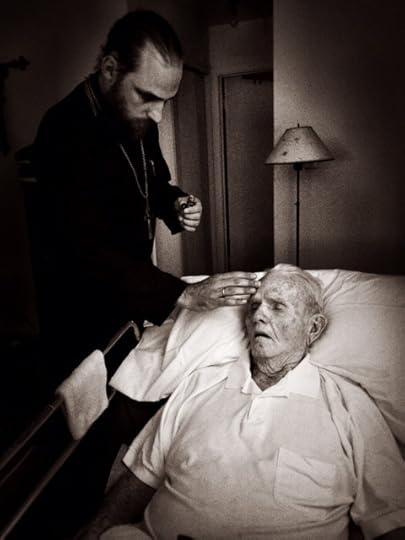

He was right. I was wrong. In large part because of that priest, I was able to be at my dying father’s bedside the last week of his life, and to hold his hand when he passed away, and to be something I had never been in my life: at peace with God and my father.

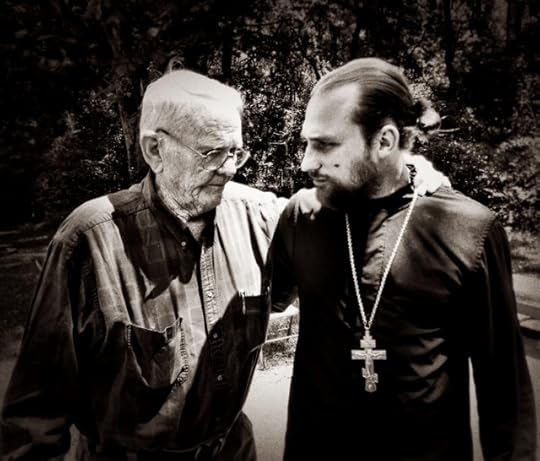

Ray Dreher Sr and Father Matthew Harrington

Daddy thought the world of Father Matthew. “That’s a good man,” he told me. And there was Father Matthew, anointing my father on his deathbed, days before he entered eternity:

When Father Matthew arrived in this subtropical sauna from the Pacific Northwest, we tried to school him in Southern manners. He told us firmly, “I’m not here to be your friend. I’m here to be your priest.” Which was a little bit shocking to us, but it turned out that he was right to say that. Were I a priest, I could not have said the hard things he said to me many times in confession — things I needed to hear, and things it would have been hard for a chummier priest to say. I love priests, and make friends easily with them. Not Father Matthew. It wasn’t that he was unfriendly, not at all. But he took his role as spiritual father very seriously, which made him immune to the usual hail-fellow-well-met ways of us Southerners.

And this made him a very effective priest. Best I’ve ever had, and likely ever will have. The thing is, he isn’t soft and intellectual, like me. Don’t get me wrong, he’s very intelligent and well read. But dispositionally, he’s not an intellectual, and that makes all the difference. When I was so sick, and struggling to make sense of the terrible emotional tangle of my family’s life, and the pain and confusion between my dad and me, Father Matthew cut straight through all the rationalizations that kept me from seeing myself as I really was. As I’ve said, Dante was the leader, but I could not have been set free were it not for the help of my therapist Mike Holmes, and Father Matthew. It was he who gave me the epic prayer rule that got me out of the prison inside my head. It was he who refused to let me feel sorry for myself.

He did not comfort; he led. And for that, I will be forever grateful.

I had been Orthodox for six years when the Harringtons arrived. I loved being Orthodox, but there had been no stability in it. We moved a lot in that time, and I had allowed myself to get caught up in church politics, which was stupid and self-destructive.

Father Matthew fixed that.

He is a priest of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (ROCOR), the exile church continuing after the Bolshevik Revolution. ROCOR was fully reconciled with the Moscow Patriarchate a few years ago, but in the diaspora, ROCOR kept all the Russian traditions. We didn’t seek out a ROCOR priest for our mission — all of us were members of the Orthodox Church in America — but ROCOR was willing to send us one, so we became a ROCOR mission. That meant celebrating Christmas in January, because ROCOR follows the Old Calendar. And it meant that if we wanted to receive Communion on Sundays and feast days, we would have to come to vespers the night before.

“But no other Orthodox church does that!” we protested.

“We do,” he replied, meaning ROCOR. “It’s not negotiable.”

Boy, did we grumble, me loudest of all. What business does the church have demanding that I come to evening prayer between 6 and 6:45 every Saturday night if I want to receive Communion the next day? We have dinner parties, crawfish boils, football games to go to. We’re going to be late!

Sorry, it wasn’t negotiable.

So I did it. We all did. And in time, I came to love the vespers service. Saturday didn’t feel right without it. Father Matthew was not a hard taskmaster — he challenged me constantly, but never gave me more than I could handle. Though a convert himself, he didn’t have time for the usual American Christian, forgive me, bullshit. What a rare gift that is in a priest. His stance was basically this: Either God is God, or He isn’t. If He is God, then everything in your life must be ordered to Him. Orthodoxy is not a Sunday-only kind of faith. You have to be all in. Because God is God, and we are His people.

Your Working Boy talks a good game about the value of orthodoxy, and of Orthodoxy, but he did not know how much of it was just talk until he fell into the clutches of Father Matthew Harrington, who did not have much patience for self-deception and spiritual laziness. He’s a former cop. He grew up in difficult circumstances, raised by his grandparents. He knew the stakes, morally and spiritually, in all our lives. And he loved us all too much to let us fail.

Boy, can that man preach. He hated it when I would praise him for his homilies, but I have never heard a better preacher (and I have heard many of them in my lifetime). He made you want to be better, to repent more deeply, to love more completely, to pray with more intensity. His homilies were often not about any specific thing, but they were about everything, and not in a general, hodge-podge way. I’ve thought a lot about his rhetoric, and have been mystified as to why he was such an effective preacher, even though he didn’t write his sermons as if they were op-eds. The answer, I think, is that he did not usually tell us what to think as Orthodox Christians, but he taught us how to think as Orthodox Christians. Big difference.

It is a tragedy, a real injustice, that Father Matthew will leave us soon and return to Washington state, and will cease to work as a priest for now. He’s not leaving the priesthood, thank God, but there are no parishes open for him in our very small and poor national church. Wherever he lands for employment, the people he will be working with will not know that they have one of the most gifted young priests in America in the next cubicle over. This is wrong, this is cosmically wrong … but there’s nothing to be done about it.

Blessing the Mississippi River on Theophany

Many tears have been shed this past week as the reality of our situation has sunk in. Julie and I were talking the other night about how hard these last three and a half years of mission life have been, but how much we have grown in them. In a mission as small as ours, it was all hands on deck. Me, my habit has always been to hang back, to brood, to analyze. I couldn’t get away with that here. There was nowhere to hide. And it was good! I have grown more spiritually these last three years than I have the previous twenty, at least. It has all been grace, at times a severe mercy. But a mercy all the same.

As you know if you read The Little Way of Ruthie Leming, or my Dante book, I returned to my hometown with the best of intentions after my sister passed, but was devastated to discover a hidden family secret that changed everything. The inability to overcome old grudges sedimented into the family’s bones nearly destroyed me spiritually and physically (my chronic mononucleosis was caused by deep and abiding stress, doctors said). Thanks in large part to Father Matthew’s leadership, and the simple practice of the Orthodox life, day in and day out, as I learned in our mission, I was given the grace, the clarity, and the strength to identify, confront, and throw down the false idols of Family and Place, and finally, after four decades, begin to re-order my life around God the Father.

Reflecting on what St. John’s has meant to me, I cannot improve on the words of Dante: “Incipit vita nova: Here begins the new life.”

The most important lesson I learned from these blessed three years at St. John’s is that nothing, absolutely nothing, must come before God. There is no doubt in my mind that I could not write the Benedict Option book if it had not been for what God did for me at St. John’s. Julie and I agree that we cannot live and raise our kids without close involvement with an Orthodox parish, and the sacraments. And the education of our children — their moral, intellectual, and spiritual formation as Christians — is inseparable from the life of the Church.

That is why we have had to make the hard, hard decision to move this summer just down the road to Baton Rouge. Before we had the mission, we would drive 45 minutes each way on Sundays to the Orthodox mission there. We were glad to have the Baton Rouge church, but it’s hard to be a real part of a parish’s life if you’re so far away.

Before we received the shock about St. John’s last week, we had enrolled all three of our kids in Sequitur Classical Academy in Baton Rouge. My son Matthew was in Sequitur for its first two years, but then withdrew because of his own particular needs. Now he’s returning for his 11th grade year, and he’s bringing his brother and sister with him. The school is really growing, and we want to give everything we have to building it up. Julie has been working for months with our friends who lead Sequitur, and has been planning to open in Fall 2017 a sister school in St. Francisville. Father Matthew was key to that plan. Without Father Matthew, a classical Christian school in St. Francisville becomes untenable. We had planned to take the hit of driving 90 minutes round-trip to Baton Rouge four days a week so the kids could have a year of Sequitur before opening our local school. Now we not only wouldn’t have a local classical Christian school to look forward to, but we would also have had to add another day of 90-minutes driving, this time on Sunday. It made no sense.

Nothing about this — about any of it — is what we expected, or what we wanted. But Father Matthew has formed us all well to be resilient.This isn’t the end of the world. As much as we hate to leave St. Francisville, God must come first. Happily, it’s only 45 minutes away, and an easy drive to get back to the West Feliciana hills. Don’t worry, I’m still going to be all up in the Walker Percy Weekend. My mom is in good health, and well looked after by her friends and neighbors. She doesn’t want to see us go either, but she tells me it makes sense. Besides, it’s not far.

To be honest, if I had not been doing so much research about the Benedict Option this year, and had not become even more convinced about the critical importance of having a strong parish and school for one’s kids, it would have been harder to make this decision. But there really can’t be a compromise on this. I’m convinced of that. How strange and unsettling that circumstances are sending us into the city for the Benedict Option. But I’ve always maintained that the Ben Op is not about heading for the hills and nothing but. Most people will live out the Ben Op in cities and suburbs, because that’s where we are.

To repeat: St. John’s mission will not be closing down, I’m happy to say. There will be a remnant, and they will gather there for typika and other prayers on Sundays and feast days, and will have liturgy when a priest is passing through and able to serve. We all worked too hard to build that church for them to let it go. We will help as we can. They are our family, and some of the finest people we have ever known. And we are renting our Starhill house out, not selling it. We want to come back. But now is not the time. It breaks our heart, God knows, but you can’t sustain a parish on heartbreak.

Some of you readers came through town over these last several years, and worshiped with us at St. John’s. I’ve been so encouraged by your sincere praise of what we had there, in our community and especially in our priest. You saw it. You had a glimpse of what Orthodox parish life can be like, despite our poverty and despite our strangeness here in the rural South. If only you could have seen what we had week in and week out! Well, I did see it, and I will carry those memories for all my days. It was a theophany, all of it, even the struggles. And it changed my life.

Father Matthew arrived here as a newly ordained priest, and he leaves here a real Father. He said he came to be our priest, not our friend, but in truth, he became one of the best friends we ever had. And that is something nobody can take away from us.

‘Christ is risen! Truly he is risen!’

June 30, 2016

The Pentagon’s Social Justice Warriors

Transgender service members will also receive the same medical coverage as any other military member — receiving all medical care that their doctors deem necessary — according to Carter.

For current members of the military, the coverage will include hormone therapy and gender reassignment surgery if doctors determine that such procedures are medically necessary.

Incoming service members must be “stable” in gender identity for 18 months before joining the military.

“The Defense Department and the military need to avail ourselves of all talent possible in order to remain what we are now — the finest fighting force the world has ever known,” Carter said Thursday at the Pentagon.

The reaction from Moscow was swift:

Meanwhile, from Watts Valhalla:

But seriously … Weimar America. A reader who is one unhappy veteran writes:

Just a few news stories that ought to be addressed, showing the concerted plan to destroy not only the traditional fabric of America, but the traditional culture of the military that defends it. I served four years in the United States Marine Corps from 2001 to 2005, two tours overseas and am 30% disabled. A military reflects the society from which it is drawn and often reflects the most traditional elements of that society, because of the emphasis on honor, loyalty, fidelity, courage, and sacrifice — all those things that have been missing in civilian society or belittled by progressives.

I was a lance corporal, not some officer. I humped a rifle out there where the consequences to the social re-engineering of combat units could mean death, not diminished career prospects. I didn’t have to serve with women, transgenders or assorted malcontents and deviants like the Army, Navy and Air Force is hell-bent on instituting in their units. In the Marine Corps of my day, only one thing counted: a close knit unit whose only purpose was to “locate, close with, and destroy the enemy.”

That meant weaklings, physically and morally, jeopardized us all. It meant that an unbreakable bond among each other had to be built, a bond based on the brotherhood of men who lived together, drank together, fought together and became one. It is a ruthless meritocracy where mistakes and weakness get someone else killed. This was how Marines took Belleau Wood in 1918, raised the flag on Iwo Jima in 1945, took Hue in 1968, and Fallujah in 2004. It was the spirit that animated the icons of our Corps like Chesty Puller and, most recently, General Mattis, a real Marine who was shoved out when his brand of warfighting became uncomfortable to the Pentagon and the DC drones, who rolled over for anything the radical feminist/LGBT/social justice crowd who never heard a rifle in anger wanted like the spineless lapdogs they are.

This is the result. This is why Bowe Berghdal deserted, why transgender Bradley Manning betrayed us, why combat units are being forced to bow to political correctness rather than warfighting, and why there is a concerted plan to eviscerate every vestige of military tradition, esprit de corps, and ultimately, our military effectiveness. As for me, I’m glad I didn’t have to see this firsthand, but I still have friends who are in. I recall talking to a sergeant I had served with, who was commissioned from the ranks and was a captain in 2014 when the push for women to be in combat arms first reared it’s ugly head. I asked him just what the hell those idiots at the Pentagon were doing and he told me in these exact words: “That’s all they think about over there, bro.” He said that the atmosphere was so stifling that he was getting out. Other Marines and soldiers, veterans I have come to know have told me the same thing. They spend more time on sexual etiquette classes than time at the rifle range, and bucking the reeducation program is a fast track to discharge. Talk to other vets who know, talk to someone still in willing to tell the truth.

Readers?

The ‘Re-Traditionalization’ of Europe?

It is most certainly the case that the world is going through a radical realignment along nationalist and provincialist lines. From Bosnia to Chechnya, Rwanda and Barundi, from South Sudan to Scotland, populations have been turning increasingly inward for civic and cultural identity.

But within these balkanizing tendencies is a process called re-traditionalization. Because globalization challenges the traditions and customs, the religions and languages of local cultures, its processes tend to be resisted with a counter-cultural blowback. In the face of threats to localized identity markers, people assert their religiosity, kinship, and national symbols as mechanisms of resistance against globalizing dynamics.

So far so good.

And continue they will. We should not regard this resurgent nationalism a temporary political fad. This is because globalization entails its own futility; as we have found with the attempt to bring liberal democracy to the Middle East, few are willing to die for emancipatory politics, feminism, and LGBT rights. But the willingness to die for land, people, custom, language, and religions is seemingly universal. Though a formidable challenger, globalization appears to have no chance of overcoming such innate fidelities.

I think this is true. To modify a phrase of MacIntyre’s, dying for the EU is like dying for the phone company. More:

And so, it is certainly the case that the Brexit signifies the rise of nationalism in Europe, but it also suggests the inexorable revival of traditional values and norms. And while there are a number of current cultural peculiarities and paradoxes indicative of a stubborn secularism throughout the West, we can expect social and cultural trends to resolve such inconsistencies in favor of traditional beliefs and practices.

A renewed Christian Europe may not be so far away.

Would that it were so! But I don’t believe it is. I love hearing the good news of religious revival within Russia, but news that the Duma has passed a law massively restricting the religious liberty of non-Orthodox Christians is terrible news. Putin hasn’t signed it, but I expect that he will. You know that I deeply want Europe to return to its Christian roots, but doing so out of purely tribal, nationalistic reasons does not give one hope that such a return would be truly Christian.

The problem for people like me is that nationalistic religion is, unfortunately, part of tradition in many places. The reason I was pleased that Brexit won is that I am almost always in favor of the local over the global. To the extent that the EU threatened local identities, cultures, and traditions, I think it was a threat to be resisted. I would love to see Western Europe’s Catholic and Protestant churches filled again, but if Europeans returned to them not out of a love of God and a longing for His presence, but because it was part of sticking it to Them (whoever “Them” may be), then I’m concerned.

On the other hand, getting them in the door by whatever means is to be celebrated, and then the pastors could reacquaint their de-Christianized peoples with the faith. But are Europe’s priests and pastors prepared to do this? Do they have the faith still? I don’t know, and would love to hear from European Christian readers of this blog.

Point is, two cheers for what Stephen Turley says. But the growing instrumentalization of the Orthodox faith in Russia for nationalist purposes is not a good sign. On the other hand, my suspicion is that the desire I have to separate the faith from nationalism is a distinction that is abstract and academic in the historical experience of lived Christianity outside the United States. Again, I am eager to hear from non-American readers on this.

White Martyrs Of Liberalism

From a lecture Michael Hanby gave in Philadelphia a while back:

I am deeply aware of how scandalous, even how obscene, it seems to speak of martyrdom from within the relative safety and prosperity of the liberal West, while so many of our brothers and sisters elsewhere in the world are dying for the faith. I have no answer to this powerful objection, and so I am also aware of the famous remark of Wittgenstein, “whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” And yet the suffering of a Barronelle Stutzman does not become less real simply because liberal order has perfected the art of bleeding its victims slowly and invisibly through ten-thousand bureaucratic paper cuts, rather than with the sword or lions in the Colosseum. Certainly we must be grateful for that, and yet there is a peculiar challenge for Christian faith and witness in the fact that liberal order diffuses its power quietly, almost imperceptibly, without blood or spectacle or responsibility. It creates a real possibility that one’s sufferings may be visible only to God, so that it will always be possible to say, as many of our Catholic brethren seem only too eager to say, “Move on, there is really nothing to see here.”

I sat next to Barronelle Stutzman on a couch last week and interviewed her. I couldn’t quite recall when the last time I was with someone so brave and so serene, but Hanby’s remarks above brought it to mind: sitting at breakfast in Istanbul a decade ago with a Coptic archbishop, who told me terrible stories of what his people in Egypt were enduring each day. Yet he was so gentle, so luminous. It was uncanny. Barronelle is like that too.

In Orthodoxy, someone who suffers extraordinarily for the faith, but who is not martyred, is called a “confessor.” That term means something slightly different in Catholicism. Unofficially, Catholics consider a “white martyr” to be someone who has suffered greatly for the faith, but not to the point of dying violently (that would be a “red martyr”).

The world — and some readers of this blog — say of people like Barronelle, “Move on, there’s nothing to see here.” But they are wrong. The most important thing to see in people like her is what you see through people like her.

June 29, 2016

View From Your Table

Maui Wowee

Photo by Laurel Dugan

I was standing right next to my friend Laurel Dugan when she took this image last week. This sight felt like a theophany.

She’s a painter, by the way. Check out her work. It’s kind of amazing to me that I know someone so talented, much less that I made a frosty rum drank for her last week.

The New Jacobin Normal

On the Christian pessimism thread, reader Candles writes:

I was talking to a friendly acquaintance of mine a few days ago, a liberal/left professor at a R1 university. We were talking about politics broadly and the democratic race, and I was biting my tongue a lot. He’s mid-late 30’s, not married, no kids. Family was historically Russian Jewish immigrants, but he’s an atheist, for what it’s worth. Likable guy.

At some point, he meandered onto the general topic of all the things he would like to see the Federal government doing and enforcing. He mentioned that he had spent a year living in Utah, and how frustrating it was, the general lack of cultural respect for separation of church and state there, as he saw it. And this dove-tailed with his general notion that the federal government had made great progress in forcing people in places like suburbs in Utah to respect various Civil Liberties over the last half a century, but that it hadn’t gone nearly far enough, and he thought much further efforts in those directions were both morally good and inevitable.

At a certain point, I said, “You’re essentially advocating that Mormons should be forced by the coercive powers of the state and its monopoly on violence to be Unitarians in everywhere broadly conceived, by people like you, as the public, right?” And he shrugged and said, “Yeah. What’s so bad about that?”

I think this interaction gets right deep in the heart of why there’s no way for this to end in peace. As far as my friend is concerned, as long as there is anywhere in the country he could move that would make him living in accordance of his own values difficult or even impossible, America is not living up to (his vision) of its founding principles. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere etc etc.

And to be totally honest, if I were him, and I had been forced by my job like he had to move to a very heavily LDS part of Utah, I’m sure it would have been very frustrating. I’m actually pretty sympathetic to his point of view.

But a consequence of his concerns for himself and people like him is that he wants to live in a world where Mormons are forced, by the state, with its guns, to live a version of Mormonism that he and people like him have functionally colonized. He is fine with Mormonism as long as it is a properly subjugated and subordinate to his values anywhere Mormons might interact with him (or with what he would categorize as oppressed groups, which, if push came to shove, would include Mormon women and Mormon children who might be gay or transgender).

I’m no longer Mormon, and I have misgiving about the Church, but I found myself pretty frustrated with the conversation. And he’s no kind of firebrand – I don’t think he felt like anything he was saying was particularly provocative. But I think he just couldn’t recognize that “Mormons have to be Unitarians in public, and they’re not nearly Unitarian enough yet, so that state needs to do much more” is tyranny for a large amount of Mormons in exactly equal measure that it’s liberation for him.

Which is to say, I’m very sympathetic to the general thrust of your arguments.

Thank you. One of the most galling things about these arguments is the assumption by secular liberals (and their liberal Christian fellow travelers) that their own beliefs are neutral, and more, so obviously neutral that anyone who dissents only does so in bad faith, and must neither be accommodated nor taken seriously. It’s like Scientism in that way.

A few years back, veteran religion journalist Kenneth Woodward, writing on the Commonweal blog, explained how The New York Times is its own religion. It was a great piece, and said a lot, generally, about the culture of mainstream journalism, not just at the Times. If you can find a conservative who works in a major American newsroom, ask him or her what it’s like to be a dissenter there. You will learn that the homogeneous groupthink is overwhelming there, and it’s exacerbated by the conviction among the True Believers that they simply see the world as it really is. The epistemic closure is epic. And you know, I can live with epistemic closure, because all belief systems and cultures have to draw the line somewhere. What I find repulsive is the conceit these people carry that they have no biases or prejudices at all.

Reader Sean writes:

The moment I became pessimistic was not at the Obergefell decision. While I was dismayed like a lot of other people, I thought we might be able to outlast it and eventually begin to turn public opinion, like in Roe v Wade. No, the moment pessimism set in was in the fierce reaction I got from acquaintances and friends on Facebook.

I had worked in local politics for the better part of a decade, both on campaigns and working for elected officials and advocacy organizations. When I started pushing back on the gay marriage ruling on social media, I was immediately met with a tidal wave of vitriol and anger. From my acquaintances on the left I was expecting it, but what took me back was the hatred directed my way from many of my fellow Republicans, particularly the younger and college-age set.

These were people I had worked side by side with on many campaigns, who I had formed social clubs with and gone out many a time for a friendly drink. Yet after Obergefell they were denouncing me as a hate-filled bigot who might as well have wanted blacks to still be stuck under Jim Crow. The attacks were incredibly personal, and from people who knew me, not just random trolls on the internet.

What’s more, they were gleeful at the prospect of religious believers being railroaded on this issue. When the Barronelle Stutzman and the later Indiana RFRA issues hit the news, the dominant reaction of many of the young Republicans I knew was, Serves you right, that’s what happens to bigots. When I raised the prospect of churches being directly targeted for not performing gay marriages, I was met with airy dismissals. Some, alarmingly, were not even bothered by the idea.

I knew then that none of our ostensible political allies would come to our aid when the time came. It’s hard enough to ask people to sacrifice for a cause when it directly affects them. It’s extremely unlikely that people will go to the wall for a cause they only have a vague philosophical agreement with and especially when they consider the people they would be fighting for as the worst sort of bigots.

Thus we will be on our own for the foreseeable future, which was why I was so interested when I came upon your idea for the Benedict Option. We need something to help keep us together during the times ahead, otherwise we will all hang separately.

In my experience, there is nothing like the hatred that comes from the LGBT movement and its allies, even straights. Oh, do I ever have stories about this, from my life and the lives of others. Watching Barronelle Stutzman, a gentle elderly Baptist lady from a small town, break into tears last week, talking about all the people who have threatened to kill her, and to burn her house down, all because she wouldn’t arrange flowers for a gay wedding — that tells you something important about the nature of what we’re up against.

But this is the New Normal. Dig in and get ready for the long night. A reader of this blog, an academic, said to me (maybe in a comment, or in a private e-mail, I can’t remember) that he’s a conservative on a liberal college faculty. He loves his older colleagues, all of whom are liberals of the old school, meaning they are genuinely tolerant and supporters of the free exchange of ideas. But he lives in fear of his younger colleagues, who are Jacobins to the last man.

Robert Nisbet has written, in his 1953 classic The Quest For Community:

For the Philosophical Conservatives the greatest crimes of the Revolution in France were those committed not against individuals but against institutions, groups, and persona statuses. These philosophers saw in the Terror no merely fortuitous consequence of war and tyrannic ambition but the inevitable culmination of ideas contained in the rationalistic individualism of the Enlightenment. [Emphasis mine — RD] In their view, the combination of social atomism and political power, which the Revolution came to represent, proceeded ineluctably from a view of society that centered on the individual and his imaginary rights at the expense of the true memberships and relationships of society. Revolutionary legislation weakened or destroyed many of the traditional associations of the ancien régime — the guilds, the patriarchal family, class, religious association, and the ancient commune. In so doing, the Conservatives argued forcefully, the Revolution had opened the gates for forces which, if unchecked, would in time disorganize the whole moral order of Christian Europe and lead to control by the masses and to despotic power without precedent.

And so it did, and will again. We are living through a contemporary version of this. The revolution is the next phase of the Sexual Revolution, the revolution that Philip Rieff called the most consequential one ever. Our own Jacobins are now attempting to separate our people, starting in early childhood, from their own masculinity and femininity. They are unleashing forces that will disintegrate what remains of the moral order, and are bringing forth despotism.

In his brilliant book How Societies Remember, social anthropologist Paul Connerton says that every revolutionary regime has to suppress, even exterminate, the symbol system that keeps the people it wishes to rule bound to old ways of thinking. The forces of revolution have to deprive the ruled of their memories:

All totalitarianisms behave in this way; the mental enslavement of the subjects of a totalitarian regime begins when their memories are taken away. When a large power wants to deprive a small country of its national consciousness it uses the method of organised forgetting. In Czech history alone this organised oblivion has been instituted twice, after 1618 and after 1948. Contemporary writers are proscribed, historians are dismissed from their posts, and the people who have been silenced and removed from their jobs become invisible and forgotten. What is horrifying in totalitarian regimes is not only the violation of human dignity but the fear that there might remain nobody who could ever again properly bear witness to the past. Orwell’s evocation of a form of government is acute not least in its apprehension of this state of collective amnesia. Yet it later turn out — in reality, if not in Nineteen Eighty-Four — that there were people who realised that the struggle of citizens against state power is the struggle of their memory against forced forgetting, and who made it their aim from the beginning not only to save themselves but to survive as witnesses to later generations, to become relentless recorders: the names of Solzhenitsyn and Wiesel must stand for many. In such circumstances their writing of oppositional histories is not the only practice of documented historical reconstruction; but precisely because it is that it preserves the memory of social groups whose voices would otherwise have been silenced.

Similarly, anthropologist Mary Douglas, in her classic work Natural Symbols, writes:

Each social form and its accompanying style of thought restricts the self-knowledge of the individual in one way or another. With strong grid and group, there is the tendency to take the intellectual categories which the fixed social categories require as if they were God-given eternal truths. The mind is tied hand and foot, so to speak, bound by the socially generated categories of culture. No other alternative view of reality seems possible. … Anyone who finds himself living in a new social condition must, by the logic of all we have seen, find that the cosmology he used in his old habitat no longer works.

This is one reason I keep tub-thumping about the Benedict Option. It is in large part a call to prepare for what is to come by grounding ourselves so deeply in our faith and our communities of faith that we can resist anything they throw at us.

We are not Solzhenitsyn or Wiesel, or Wojtyla, Havel, or Sakharov. God willing, we never will be. But to assume that the only way a system erases cultural memories is through governmental coercion is incredibly naive. Consider what Notre Dame professor Patrick Deneen wrote of his own students earlier this year:

My students are know-nothings. They are exceedingly nice, pleasant, trustworthy, mostly honest, well-intentioned, and utterly decent. But their brains are largely empty, devoid of any substantial knowledge that might be the fruits of an education in an inheritance and a gift of a previous generation. They are the culmination of western civilization, a civilization that has forgotten nearly everything about itself, and as a result, has achieved near-perfect indifference to its own culture.

It’s difficult to gain admissions to the schools where I’ve taught – Princeton, Georgetown, and now Notre Dame. Students at these institutions have done what has been demanded of them: they are superb test-takers, they know exactly what is needed to get an A in every class (meaning that they rarely allow themselves to become passionate and invested in any one subject); they build superb resumes. They are respectful and cordial to their elders, though easy-going if crude with their peers. They respect diversity (without having the slightest clue what diversity is) and they are experts in the arts of non-judgmentalism (at least publically). They are the cream of their generation, the masters of the universe, a generation-in-waiting to run America and the world.

But ask them some basic questions about the civilization they will be inheriting, and be prepared for averted eyes and somewhat panicked looks. Who fought in the Peloponnesian War? Who taught Plato, and whom did Plato teach? How did Socrates die? Raise your hand if you have read both the Iliad and the Odyssey. The Canterbury Tales? Paradise Lost? The Inferno?

Who was Saul of Tarsus? What were the 95 theses, who wrote them, and what was their effect? Why does the Magna Carta matter? How and where did Thomas Becket die? Who was Guy Fawkes, and why is there a day named after him? What did Lincoln say in his Second Inaugural? His first Inaugural? How about his third Inaugural? What are the Federalist Papers?

Some students, due most often to serendipitous class choices or a quirky old-fashioned teacher, might know a few of these answers. But most students have not been educated to know them. At best, they possess accidental knowledge, but otherwise are masters of systematic ignorance. It is not their “fault” for pervasive ignorance of western and American history, civilization, politics, art and literature. They have learned exactly what we have asked of them – to be like mayflies, alive by happenstance in a fleeting present.

Over and over again, when I speak to professors who teach at Christian colleges, the story is the same: these kids come to us knowing next to nothing about the faith. Nobody at the Ministry of the Suppression of Christianity ordered their families, their churches, or their Christian schools to deprive these kids of their inheritance. They didn’t have to — and that is the epic tragedy of our time. People without a past will have whatever future those who command their attention want for them. If you think your children, and your children’s children, will be Christian in any meaningful sense of the term without you and your community fighting like crazy to swim upstream against the current of this post-Christian culture, you are living a lie. I’m sorry, but it’s the truth.

You may not be interested in the Jacobins, but the Jacobins are interested in you — and your children. We must fight them every opportunity we get, but we have to know what we’re fighting for, and we have to know how to continue the fight underground if we are ultimately defeated.

Leaving aside the infinitely more important cause of the eternal fate of souls, there is the matter of making sure that there are people alive in the generations to come who can properly bear witness to the past — not just the particularly Christian past, but to Western civilization, the civilization that — I speak symbolically, of course — came from Athens, Rome, and Jerusalem. We fight for Christian civilization itself, which includes what emerged from Moscow too. And therefore we must fight against the nihilistic successor civilization of New York, Los Angeles, Washington, and Brussels. We fight for the Paris of St. Genevieve, not the Paris of Robespierre. Modern civilization has no past, only a future. If our civilization is to have a future, it must be rooted in our past. We must remember our sacred Story.

I believe we will have a future, and I will fight for that future by fighting to keep alive the memory of the past. I won’t stake my life on defending New York, Los Angeles, Washington, and Brussels, but I will stake my life on defending Athens, Rome, Jerusalem, and Moscow. That’s where the battle is. It’s a battle taking place in every city, town, and village in America. Which side are you on?

All-Nighter

Father Matthew, blessing the Mississippi River on Theophany (Photo by Rod Dreher)

Please forgive me for no posting this morning. I pulled an all-nighter, and very nearly finished the final chapter of the Benedict Option book. (That’s not as good as it seems; I have two more inside chapters to go.) Went to bed at 5 a.m., and was awakened just now by the oncoming train of a caffeine headache.

The first chapter of the book is a “Gathering Storm” introduction, laying out the problem. The final chapter of the book is a short recap of what has come before, but then one that explores the higher reasons for being a small-o orthodox Christian — what Chesterton would have called the romance of orthodoxy. If people come to the Benedict Option out of fear, that’s … well, that’s not necessarily wrong, because there is a lot to be worried about. But it’s not going to last if it’s not motivated above all by love. What I need to do in this chapter is convey a sense of the love of the historic faith, with the Christ of the Bible and the ages at its center.

The late film critic Roger Ebert held that the difficulty of writing a film review existed in inverse proportion to the quality of the film under review. The better the movie is, the harder it is to write a review of it. As a former professional film critic, I can tell you that that’s absolutely true. It’s easy to pick out what’s wrong with a film that fails, but one that is a true work of art defies easy description.

It’s that way for me in talking about my faith. Writing this final chapter has made me understand more deeply the point Pope Benedict made about the best arguments for Christianity being the art and the saints that come out of it — that is to say, the Beauty and the Goodness that bear witness to the Gospel Truth. Last night, thinking through all the ways God brought me to Himself by drawing my love towards Him, I couldn’t think of a single argument that was primary. It started with love: the love of things and people that captured the Light, and refracted it. That Light made it possible for me to grasp the arguments. But it was never about an argument. It was about seeing something there that was greater than myself, and wanting to know it, and coming to believe that that something was a Someone, and He was love itself.

This took years of slow growth, with many ups and downs and trials and tribulations, but it became my reality. I find that trying to explain why I’m a Christian is like trying to explain why I love my wife. I mean, I believe that Christianity is true, but that is only part of it.

I’m going to return to last night’s chapter this afternoon and try to finish it. When I finally crashed last night, I had fallen into telling stories of theophanies — moments when God broke into the world, and I knew I was in the presence of the sacred. Very few of them happened in church. In all those moments, I knew in my bones that I was in the presence of something realer than real, and that the only proper response was to say inside, My Lord and my God.

That’s not a narrative that persuades others, but when I think that these events in my life are pages in a big book that tells the Story of the universe, from Creation to the End of All Things, and that they are pages in a book that includes Moses and the Exodus, David and Goliath, the Hebrew Prophets, the Annunciation, the Nativity, the Passion and Resurrection and Pentecost, Paul’s journeys, St. Polycarp’s pilgrimage to martyrdom, the Cappadocian fathers (imagine growing up with St. Macrina as your mother), Constantine’s conversion, the Martyrs of Lyon, St. Augustine pondering the collapse of Rome, the Celtic fathers clinging to rocks in the sea, St. Benedict founding his order, the conversion of Prince Vladimir, the agony of the Great Schism, Thomas Aquinas’s “everything is straw” vision, Dante (Dante!), the Fall of Constantinople … well, I could go on, all the way up to my waking up at noon and sitting here writing this blog. My own story only has meaning as part of the Great Story, the one that starts with the words, “In the beginning.”

I have found no better way to describe what it’s like to be a pilgrim in this story than the Divine Comedy. The farther one goes into the story, the more one loves, and the more one knows. The capacity to know and to love is infinite. Near the beginning of Dante’s Paradiso, the poet describes the experience as akin to a Greek myth in which a fisherman tastes a magic herb that makes it possible for him to become one with the sea. That’s the Christian life of theosis, of making this lifelong pilgrimage towards total and eternal union with God. To be part of the same pilgrimage with so many others — not only the saints of old, but Christian men and women like the monks of Norcia, like Marco Sermarini and the Tipi Loschi, like Barronelle Stutzman and Chief Kelvin Cochran, and Evgeny Vodolazkin, and Father Matthew Harrington, my own priest, is a privilege and an adventure and … well, it’s overwhelming to imagine, much less put into words.

But I’m going to have to make an attempt, because I am a writer, and this is my next book.

Rod Dreher's Blog

- Rod Dreher's profile

- 509 followers