Rod Dreher's Blog, page 41

November 16, 2021

Journalists Welcome New Woke Overlords

Back in 2017, I wrote the following in The Benedict Option:

David Gushee, a well-known Evangelical ethicist who holds an aggressively progressive stance on gay issues, published a column in 2016 noting that the middle ground is fast disappearing on the question of whether discrimination against gays and lesbians for religious reasons should be tolerated.

“Neutrality is not an option,” he wrote. “Neither is polite half-acceptance. Nor is avoiding the subject. Hide as you might, the issue will come and find you.”

Public school teachers, college professors, doctors, and lawyers will all face tremendous pressure to capitulate to this ideology as a condition of employment. So will psychologists, social workers, and all in the helping professions; and of course, florists, photographers, bakers, and all businesses that are subject to public accommodation laws.

Christian students and their parents must take this into careful consideration when deciding on a field of study in college and professional school. A nationally prominent physician who is also a devout Christian tells me he discourages his children from following in his footsteps. Doctors now and in the near future will be dealing with issues related to sex, sexuality, and gender identity but also to abortion and euthanasia. “Patient autonomy” and nondiscrimination are the principles that trump all conscience considerations, and physicians are expected to fall in line.

“If they make compliance a matter of licensure, there will be nowhere to hide,” said this physician. “And then what do you do if you’re three hundred thousand dollars in debt from medical school, and have a family with three kids and a sick parent? Tough call, because there aren’t too many parishes or church communities who would jump in and help.”

In past eras, religious minorities found themselves locked out of certain professions. In medieval times, for example, anti-Semitic bigotry in Europe prevented Jews from participating in many trades and professions, shunting them off to do marginal work that Christians did not want to do. Jews entered banking, for example, because usury was considered sinful by medieval Christianity and was kept off-limits to Christians.

Similarly, orthodox Christians in the emerging era will need to adapt to an era of hostility. Blacklisting will be real.

Five years later, in some professions, it’s worse than I anticipated back then — and the ideology has gone beyond sexuality to take in race. I wrote The Benedict Option to help my fellow orthodox Christians navigate the brave new world, but the destruction of the professions by ideology affects all honest men and women, of any faith and no faith, who aspire to work within them. Is there a place left for honest people there?

Take a look at two pieces of news from today, the first from the world of professional journalism, the second from the psychology profession.

Working with Project Veritas, a whistleblower at the CBS affiliate station in San Antonio exposes the shocking “diversity training” going on at stations like his across the country, owned by the same parent company. Watch this 7:16 video. In it, you will hear diversity trainers caught on video (apparently these trainings were done by Zoom) instructing journalists not to be objective:

These aren’t hidden camera clips from Project Veritas, but clips that were livestreamed to employees taking diversity training from Zoom. One of the trainers is from the Poynter Institute, which, I can tell you from my days in newspapering, is a big deal in US journalism culture. Poynter provides lots of professional training for journalists.

As I’ve said here before, I spoke earlier this year to a working journalist in one of America’s biggest newsrooms, who told me that the younger people there seem to believe that journalists have no obligation to be fair, or to seek out a side of the story that challenges the progressive narrative. The rising generation in that newsroom believes … well, they believe what the diversity trainers in that video above want them to believe. This is the death of professional journalism. Note well that the whistleblower talks about how in the training, the diversocrats had all the participants divide people into demographic categories, and rank them in matter of importance (e.g., race, age). Brett Mauser, the whistleblower, says that this ideology trains people to look at others in terms of group identity — and he correctly compares this to totalitarianism.

Brett Mauser, from inside a broadcast newsroom, directly validates the message of Live Not By Lies. And he brought the receipts to Project Veritas. See them for yourself. You should be wondering whether your go-to media sources are doing the same kind of internal training, to educate the actual journalistic values out of them.

I expect that the usual liberal suspects who comment here will try to discredit this reporting by griping about James O’Keefe and Project Veritas. But more reasonable people ought to watch it to see what the diversity trainers were saying to reporters — and what one anchorman says about how he doesn’t care if people trust him. The seeds for all of this were very much there when I left the mainstream media in 2010, but now it seems to have blossomed fully. If you are young, think hard about this before you train for a career in journalism. You might well find yourself stuck in a print or broadcast outlet that won’t let you do your job, only do propaganda.

It appears that journalists today are being trained to serve Our New Woke Overlords:

One aspect of soft totalitarianism that we didn’t see in the hard version: this is not being imposed by the state, but being welcomed into the professions by crack-brained do-gooders.

Meanwhile, a prominent Canadian psychologist loses his temper:

This is absolutely inexcusable. Come on, psychologists: if you don’t stand up to these self-righteous ideologies who will? Can’t you see what this will mean? No more classic psychotherapy training. Woke investigators on every campus. A nightmare for anyone individual focused. https://t.co/ugtR1BQHKf

— Dr Jordan B Peterson (@jordanbpeterson) November 17, 2021

You might look at the list that Peterson cites and say, “What’s the big deal?” The phrase that’s doing all the heavy lifting in that passage is “Human Rights and Social Justice.” An anodyne formulation, but one that in Canada, with its ultrawoke and powerful Human Rights Commissions, should put the fear of God into you. Not only are they ruining psychology by politicizing it, but I predict that psychology will be used by the woke in power in the way the Soviets used it: as a means of pathologizing and punishing critics of the regime. Similarly, journalists will be eager to report on Enemies Of The People, and will give each other awards for doing so. After all, the Pulitzer Prize went to that fraudulent 1619 Project.

It’s all happening, and it’s happening right now. Slowly but with increasing speed, the noose is tightening. If we don’t speak up and fight back now, it won’t be possible before much longer.

The post Journalists Welcome New Woke Overlords appeared first on The American Conservative.

Michael Pack Vs. The Baizuocracy

Here’s a bracing essay by Michael Pack, a Trump administration appointee to run the Voice of America, who was defeated by the Democrats in Congress and then by the permanent bureaucracy — perhaps the “baizuocracy,” an entity administered by white leftists (in Chinese, “baizuo”) — at the agency he was tapped to run. Here’s the most important part:

What to do about it? I do not accept the two favorite solutions put forward by conservative reformers.

The first group says the problem is that Donald Trump did not get enough qualified, experienced, government professionals in key political appointments soon enough. Next time, we need to have a government in waiting, ready to serve. Surely, this is a good idea, but far from sufficient. In my agency of 4,000 people, I could bring in about 10 political appointees. We were outnumbered 400-to-1.

As near as I can tell, all my mid-level and senior managers were partisan Democrats or not very political. Many lower-level workers, especially technicians, were more evenly divided, but they did not lead the agency. Those who did lead the agency made their opposition to President Trump and me personally very clear. No amount of management genius by a few could overcome this concerted opposition of the many who were out to undermine us. Only hubris could persuade otherwise, hubris which is likely to lead to ineffective and weak leadership. Usually, those who think they can manage the bureaucracy end up instead making an implicit deal with them: They are allowed a few conservative pet projects to burnish their credentials with their base, but they agree to let the bureaucracy run the remaining 95% of the agency — a recipe for a peaceful and “successful” time in office.

The second, more radical group of reformers advocates firing huge numbers of career bureaucrats in a short time. Some say we need to fire 30% in the first weeks of a new administration, an appealing slogan and rallying cry, but no more likely to succeed than a “good management” solution.

I highly doubt that this ambitious objective could be achieved, given the size and nature of the modern federal bureaucracy. Government bureaucrats have powerful civil service protections. In eight months, I could not fire a handful of people whom career adjudicators recommended terminating for cause, such as gross mismanagement leading to security lapses. I put them on administrative leave with pay and then started the process of removal. All have been brought back among those who wanted to return. Republicans often promise to eliminate entire departments. For example, candidate Ronald Reagan ran on eliminating the newly created Education Department. Not one department has been eliminated. Most grew in size, including the Education Department.

Even if the new administration could institute a 30% across-the-board cut, the wrong people would likely be fired. The best at scheming, the most committed ideologues, are the most skilled in surviving reductions in force. Declaring war on the bureaucracy, unless you have a real plan, will mire the new administration in endless internecine battles, in court and on the Hill, distracting it from the rest of its agenda. Remember all the supporting institutions, like the media, the courts, and whistleblower law firms? They would have a field day.

Biden is proving to be so hapless that I would not be surprised if Trump was re-elected. Do you think Trump will be any more competent at fighting this the second time than he was fighting it the first? Has he shown himself to have learned any lessons? Is he out building the kind of machine that can root out these loyalists with the effective ferocity of US Marines clearing tunnels on Iwo Jima? Don’t make me laugh.

Do we on the Right expect that of him? No, we do not. Most of us want nothing more than emotional validation over and against our political enemies, even as those enemies keep winning actual, substantive policy conflicts within key institutions. One side has built up a whole cadre of commissars to staff every major American institution, and can literally ruin people’s livelihoods; the other side makes liberals cry on Twitter and chants, “Let’s go, Brandon!”

On the other hand, I complain about this all the time, but what solutions do I offer? None. But then, I don’t have a mind that understands how bureaucracies work, so I wouldn’t have the faintest idea about how to go about dismantling the ideological biases in the one we have. Is it even possible? Is it even possible to create a federal bureaucracy that plays it straight? And if not, what does that say about our country and its government?

Maybe the best we on the Right can do is to elect a president who can somehow govern without the bureaucracy on his side. Maybe we can elect a president who can walk on water.

Seriously, though, do any of you readers have an idea how a future Republican president could strike a serious blow against the permanent biased bureaucracy? If you were a strategist working within the GOP to figure out how to effectively fight the “Deep State” — I use the term advisedly — for the next time your party came to power, where would you start?

And again, if the battle is futile, if the federal government is a baizuocracy, a permanently occupied territory, what does that tell us?

The post Michael Pack Vs. The Baizuocracy appeared first on The American Conservative.

November 15, 2021

Gen. Flynn’s Trumpagelical Integralism

Did you see Gen. Michael Flynn over the weekend at that crackpot hootenanny at John Hagee’s megachurch? The one in which a church full of people chanted, “Let’s go, Brandon” as they were egged on by a man onstage? In his remarks, Flynn said that America was prophesied in the Gospel of Matthew, and said that we need “one religion” in America. Watch:

Saw a short clip floating around of Michael Flynn calling for “one religion” in America.

I took a moment to dig to make sure the broader context was, in fact, Christian nationalist in nature.

Answer: Yup, and it arguably gets *even more so* the longer you watch. pic.twitter.com/MmAvMutI7K

— Jack Jenkins (@jackmjenkins) November 14, 2021

First of all, his Biblical exegesis is bonkers. America is not Biblical Israel. We are a country that has been greatly blessed by God, but Americans are not a chosen people. This is idolatry. I am in favor of what is called “national conservatism,” but I do not believe in mixing nationalism with Christianity. In Germany and Austria before the Second World War, lots of Christians were so corrupted by nationalism that they fell for the Nazi Party’s pseudo-Christian propaganda, and failed to recognize the evil of Nazism. I oppose the Church getting too close to the state for the sake of protecting the Church.

Second, about the “one religion” think, Flynn didn’t specify which religion, though presumably he means Christianity. Leaving aside the constitutional ban on establishing a religion, this country is rapidly de-Christianizing — an alarming fact, but one we have to deal with. Christians are 70 percent of the country today, but the picture is distorted by the weight of older demographic groups. If we were somehow able to repeal the First Amendment, there is no guarantee at all that the religion established in this country would be Christianity.

Besides which: whose Christianity would it be? Michael Flynn’s, whatever it is (he was raised Catholic, but it’s not clear where he worships today)? Over my dead body. I am a churchgoing Christian who recognizes the nonsense that went on in that Texas megachurch over the weekend as idolatrous nonsense. I would do everything I could to prevent that nationalistic pseudo-Christianity from infecting my church community. I wrote about the big Jericho March in Washington last December, and what an appalling religious spectacle it was.

I’ll give Flynn this, though: it is better for a country to be united in religion. It makes things more stable and cohesive, but as the case of contemporary Ireland shows, it doesn’t mean that the populace will remain Christian. Even if you concede that having only one religion in a country is ideal, that does not describe conditions in the actually existing USA. Absent mass conversion, there’s no way to enforce the “one religion” mandate without tyranny.

The Catholic integralists make a claim far more sophisticated than Flynn’s crudeness, but one that is clearly related. They too believe that society should have a single religion, and that it should be Roman Catholicism. How you get that in a country where only slightly more than 20 percent of Americans identify as Catholic, I don’t know. How you get that in a country where the number of Catholics who would accept the Church’s authority over their lives is very small, I don’t know. I mean, without mass conversion, I don’t know how they do it absent tyrannical methods.

Writing in Notre Dame’s Church Life Journal, Terence Sweeney considers both the Benedict Option and the integralist program, which he calls the Salazar Option, after the one-time authoritarian leader of Portugal (who, note well, was not a fascist, and who didn’t make Portugal into a confessional state). Here’s how the essay begins:

The publication of Rod Dreher’s The Benedict Option by Penguin Random House in 2017 launched a slew of options. There was the Dominican, Franciscan, Ignatian, and Salesian Options (my favorite was the Walker Percy Option). The debate about these options occupied the Catholic commentariat for a while, but the furor around these options slackened during the Trump years. A recent article titled “The Salazar Option” brought back memories of this proliferation. The shift is stark: from an array of saints and scholars to a petty dictator forgotten outside of fascist circles. This article is not in isolation, as many conservative Catholics have shifted from programs based on saints and religious orders to a variety of integralist, fascist, and neo-colonizing options.

Despite the incongruity, there are connections between the Benedict Option and the Salazar Option. To see these connections is to identify a constitutive flaw in those early debates while also recalling important insights from the various options. My goal here is to figure out how we can have the insight while excising the flaw. We need, in a sense, to begin again with those conversations to take seriously the diminishment of Western Christianity, and to articulate a vision forward for a small Church open to going out into the world to invite our neighbors into the Church.

The BenOp conversations were centered on the question of how the Church relates to the world and how we are to live as Catholics in these Christ-forgetting times. This conversation was and is essential, the defining theological question of our time. However, the conversations were short-circuited by a vision of Church-world relations based in a Schmittian friend-enemy binary. The rejection of this binary has been at the heart of Francis’s papacy as he articulates an ecclesiology of open doors which might very well be the Benedict we are all waiting for.

Well, I think he’s as wrong as wrong can be about the Francis papacy, but I won’t argue with that. Before I engage with the meat of Sweeney’s essay, here is his characterization of the subsequent discussion among Catholics:

The culture war was lost; the “empire” of Christendom is fallen. All that could be done was to foster intentional communities amidst the ruination. This was the state of the Church in 2017. And yet by 2018, Christians, especially Catholics, quickly shifted their intellectual projects from the Benedict Option to integralism. The Benedict Option was premised on having lost the Culture Wars. The integralist option was premised on the idea that we could so thoroughly win the Culture Wars that, according to Sohrab Ahmari, we could enjoy “the spoils in the form of a public square re-ordered to the common good and ultimately the Highest Good.” The Benedict Option saw the Roman Empire as fallen; the integralists thought the Imperium could be restored.

How did this shift from “it is all lost” to “it can all be won” take place? And how do we get from bolstering our local communities, parishes, and schools to seizing the reins of power? To see this, we must understand the core flaw of the Benedict Option. This defect regards those who are outside the Church (or perceived as being outside). In Dreher’s metaphor those “outside” are barbarians who, like the barbarians of the late Roman Empire, have brought ruin to the Imperium. If we take barbarian as our guiding metaphor for others, we must then determine what to do with said barbarians. In Dreher’s metaphor, the barbarians are winning (or have won), so we retreat strategically, sustaining the light of the faith and laying seeds for a new civilization. This, as Dreher has rightly insisted, is not defeatism but a realism that allows a robust approach to our actual situation.

But that is not the only option when faced by barbarians. Sure, if one thinks that one has no chance of victory, one might take this route. But what if you can fight back and win? One only speaks of the spoils of victory and the transformation of the public square because victory is possible. Barbarians—in this case secular liberals, leftists, and many Christians—are not the type with whom you can reach compromise. While Ahmari is not as extreme as the pro-Salazar right, he too thinks that we cannot hole up and survive. If we take that route, we should expect what Christophe Roach calls the “branch Davidian treatment.” We must fight to survive and then to conquer.

Again, I’m not Catholic, so I don’t have a good handle on how the conversation shifted in Catholicism. Did it really move so quickly from discussing the Benedict Option to integralism? Maybe it did — but I also wonder about the extent to which either idea was or is being discussed outside of the Very Online. Anyway, I’m not sure why Sweeney identifies the barbarian problem as the fatal flaw of the Benedict Option model. I use the term to describe post-Christian Americans (including post-Christian Christians) who no longer share the faith, or who have adopted a modernist form of the faith that makes it conform to contemporary progressive standards. I don’t think that they can be defeated in the short term. Team Integralist says:

Meanwhile, right liberals and libertarian Christians routinely mock the idea that Christianity could master the public square prior to widespread conversions.

Yet woke ideology, including in its pseudo-Christian iterations, has decisively taken hold of the Western public square, though its true-believing adherents form a minuscule share of the population. Could cultural Christianity become again politically relevant, not for the further extension of liberalism, but for the protection of traditional Christian life? We answer yes, that the very political examples criticized as “insincere” betoken Christianity’s enduring importance.

They are correct that wokeness is so powerful, despite representing the views of a small number of Americans. They don’t explain why, but the only possible answer is that it conquered the elites who administer American institutions. Why hasn’t there been mass pushback against it? I would argue that it’s because many woke suppositions, despite their extremism, reflect what most Americans believe. The insane gender ideology debates are happening not only because they are forced on us by progressive elites, but also because most Americans, especially the young, who came of age in a post-Christian country, accept the choosing individual as sacrosanct, and recognize few if any natural limits. This is the cultural revolution that small-o orthodox Christians and conservatives are up against. The woke are indeed a vanguard, but they are rowing with the cultural tide.

How could Christians “master the public square prior to widespread conversions”? I suppose the same way the woke have done: by marching through the institutions. But what kind of changes would they make to the system to establish their mastery?

In the first 2019 French-Ahmari Debate (starting just after 28:00), French challenges Ahmari to explain how he would fight Drag Queen Story Hour. Ahmari says he would like to see a Senate hearing in which Hawley, Cruz, and Cotton roast a librarian. OK, says French, but what serious thing would you do? Ahmari says, “Local ordinances” — which, as French points out, are subject to constitutional review, so this is not a way out. What? Ahmari’s got nothing. Watch the clip yourself.

This is why it’s unlikely that we will defeat these people in the near term, unless we abolish the Constitutional order. French keeps pointing out that if we do that, just to get at the freaks of Drag Queen Story Hour, we will leave our own institutions vulnerable to those who hate us. And unless we see mass conversions in the next decade or two, they are going to be a majority in America by mid-century. Where will we hide then? Note well that the angry woke left doesn’t like the First Amendment either. As the Millennials and Gen Z age, there will be a lot more of Them than there are of Us. If the integralists prefer a top-down Catholic dictatorship, then they should say so. If not, then they should explain how they will master the public square as tiny minorities within a post-Christian society.

Look, some Ben Op critics call it “defeatist,” but I don’t want Christians to lose! The Benedict Option idea is not how I prefer to live. But I agree with the Catholic historian Robert Louis Wilken that in the modern world, we have lost much substance of what the Christian faith stands for. If we hadn’t, then Catholic sociologist Christian Smith’s concept of Moralistic Therapeutic Deism would not be such a compelling and convincing explanation of contemporary religious demoralization. To think that political power can reverse the deep currents that have led us to this decadent state is to follow the Julian The Apostate Option, named after the neopagan Roman emperor who tried to return the Empire to paganism, and failed.

What is the purpose of controlling the levers of worldly power if we lose the next generations to the faith? What does it matter if we depend on nominal Christians to help us master the public square, if the life-changing power of the Gospel does not exist in their lives? Kierkegaard famously said that in a society where all are Christians, Christianity ceases to exist. His point was that if people come to believe that they are Christians simply by virtue of having been born into a Christian society, then people will lose the authentic Gospel, which requires radical conversion of life. Kierkegaard, a cranky Protestant, went farther than I would go on that point, but I believe he is more right than wrong.

As I write in The Benedict Option, Christians have to stay involved in politics, if only to protect religious liberty. I come out strongly in the book against my fellow Christians who think that politics is the solution. It is part of the solution, yes, but it cannot be the whole of it, or even the greater part. All my adult life I have heard conservative Christians speaking, and watched them behaving, as if winning political power were the key to solving our problems. Our candidates did win, often. Are we a more observably Christian country because of it? Things probably would have been worse had they not won, but that’s a very low bar for success. Look at this:

In the decade of political Christianity’s greatest influence over national politics, the decline of Christianity in America began. I don’t think that there is one-to-one causation at work here. That is, contrary to what liberals might say, I don’t believe that the Religious Right’s influence over politics is the cause of younger Americans abandoning Christianity. There were other more important factors, such as longterm effects of the divorce revolution. I only cite the graph above to show that political power did not help us Christians hold on to our children’s generation. And, we just had four years of a president who openly and lavishly praised Evangelical Christians, but under whose presidency wokeness accelerated to Lamborghini cruising speed. Again, I’m not blaming Trump for that, but am simply saying that politics cannot control culture.

Back to Sweeney’s essay:

As Wittgenstein argued, language can be bewitching. We are captured by the pictures of the world that our metaphors shape. To think of others as the barbarians is to imagine them as enemies, and one fights enemies. Too many have been captured by this image. Unsurprisingly, Carl Schmitt’s popularity is rising on the right. For Schmitt, “The specific political distinction to which political actions and motives can be reduced is that between friend and enemy.” If we posit the people around as barbarians—enemies to our group of unambiguously Christian friends—then we have the following options: you have lost the war, so you survive and thrive in the “monastery”; or you can still win, so you fight and conquer. In 2016, the answer was the former. In 2018, the answer shifted to the latter.

The move from the Benedict Option to the Salazar Option was possible because the BenOp metaphor was wrapped up in the idea of enemies.

Well, no, that’s not right. The barbarian tribes were enemies of Imperial Rome, yes, but to the early Benedictines, they were also potential Christians. The Benedictines were not an evangelistic order, but they did reach out to the peasantry in many ways, to present them with the faith and with better ways of living amid chaos. As Catholic historian Russell Hittinger said in this great lecture on the legacy of St. Benedict:

Benedict’s wisdom, genius and “legacy,” for which history rightly esteems him, certainly extend beyond the modest walls of the monastery or the humble souls of the monks. If one goes to Benedict’s hometown of Norcia, a little town of about 4,600 souls nested in the mountains of Umbria, one quickly happens on the Piazza di San Benedetto. On the far end of the piazza stand a church and a monastery built over the top of the Roman-era apartment building in which Benedict was raised. In the center of the piazza is a statue of Benedict, made by Giuseppe Pinzi in the late 19th century. The inscription reads:

Founder and Father of Monasticism in the Western regions, he was driven by the Spirit to a life hidden from society. From whence there arose a renaissance of letters, the useful arts, agriculture, and sciences.The inscription is quite astute. Benedict, it suggests, is the patron saint of Europe not so much because of the civilizing of culture accomplished by his monasticism but because he went into the desert. This reveals the spiritual root of European culture. Europe’s claim to fame, in other words, is not so much that it relearned and perfected the arts and sciences preserved by monks during the Dark Ages, but rather that Europe is a civilization grown from a cultivated desert. This is a quite radical claim, made in our own day more than once by Pope Benedict XVI, who suggested that the current crisis of European identity should be understood in terms of what the Benedictines did in the wasteland: Were they merely technicians who invented tools to till the soil, or were they about the business of clearing the weeds growing in the human soul?If Benedict’s Rule established nothing but a trade school for learning the useful arts—slightly eccentric monks who figured out how to build windmills—it quickly would have made itself obsolete. For it is in the very nature of such an enterprise to graduate its students into more advanced skills. This is how humanists in modern times interpreted the story of Benedict’s “school.” But if the monastic school teaches its students to awake from the mortal slumber of the Old Adam, and like the Prodigal to run to the Father, no one (in this life, anyway) can claim to be a graduate, and the capacity of monastic culture to renew culture from within is truly boundless.10

How to be “a beginner”: This is the first thing Benedict teaches the Dark Ages, his and ours. To be a beginner in this way is not a primitive condition to be outgrown but rather a sign of advancement and the mark of a return to the most essential. It is what everyone needs to relearn each Lent and learn again amid the vespers of our present age.

Yes! And more:

It is worth reflecting on the possibility that technology alone is not the only factor that marks civilization from a dark age. The European Dark Ages teach us that the more diversified the functions of a civilization, the more necessary it is that at least some people know what is a life worth living versus a life worth merely enduring. The Dark Ages were dark because people simply forgot what the Owl of Minerva understands—namely, the way the world ought to be or, at least, the way it once was.

As one will discover when reading the Rule, in addition to their commitment to poverty, chastity and obedience, like other consecrated religious, the Benedictine monks also promise stability (stabilitas) and reform of manners (conversatio morum). Stability was perhaps the most important vow for the Dark Ages. For when the Benedictines established a community, they were there to stay. Unlike the warrior class, which was mobile and just short of nomadic, the monks would arrive, clear the forests, and irrigate and cultivate the land. Within earshot of the bells, laypeople could begin again to measure time. From the monks they learned how to properly bury the dead, how to read and write—how to do things that transcend a life of mere subsistence. In summary fashion, this is what Benedict taught the Dark Ages: how to live life as a whole when forces of disintegration and confusion abound. Not a life of worldly success so much as one of human success. Not only how to divide a day, but how to divide it unto wisdom.

Maybe the greatest difference between the integralists and me is that we have a somewhat different diagnosis of the nature of our civilizational sickness, and very different ideas about how to fix what is broken. We probably agree that the core problem of our civilization is that it has forgotten God. We might differ a bit on the manifestations of that forgetting. But we definitely disagree on how to address the crisis. I think it’s going to require the work of generations, to nurture us back to wholeness; the integralists seem to believe that they can command the body politic to get healthy. I don’t think they can do this any more than the Communists could command the economy to obey its will. And even if they did take full power, it is one thing to have people obey the law, but that’s not the same thing as conversion of life. If outward obedience to the law was sufficient to guarantee a Christian society, Spanish Catholicism wouldn’t have collapsed shortly after Franco died in 1975.

Once more, here’s Sweeney:

The genetic flaw of the Benedict Option was that it thought of those outside the Church according to the un-Christian hermeneutic of friend-enemy.

Not so, or not as Sweeney has it. In the book, I talk about the enemy (though I don’t use that word) being our own complacency about the lateness of the hour and the depths to which we have sunk. Besides, The Benedict Option is not a manual for how to defeat the enemy (defined as those outside the Church). It’s about keeping the faith alive in a period of chaos and de-Christianization. Again, I would consider it a tragic defeat if believing Christians held all the top political offices in the country, but the country had become hostile or indifferent to Christianity, whose founder is the Way, the Truth, and the Life. I think Sweeney may mischaracterize the Benedict Option because he wants to posit Pope Francis as offering the real solution to the crisis of our age. He writes:

If we need to look for new Benedict Options, Pope Francis is a good guide. He sees the deep un-Christianity of friend-enemy binaries and the need to restore the biblical language of neighbor, friend, and brother. In Fratelli Tutti he writes “Amid the fray of conflicting interests, where victory consists in eliminating one’s opponents, how is it possible to raise our sights to recognize our neighbors or to help those who have fallen along the way?” Here there is no language of the spoils of victory, forced labor, or going for the jugular. We are not trying to eliminate or avoid our opponents; we are trying see them as neighbors. We are to help them along the way to God.

To go out to my neighbors or to welcome them in requires open doors that let us go out and allow them to come in. In so doing, we find that our neighbors are actually our brothers and sisters. This is a key to Francis’s maternal and paternal images of the Church. Francis teaches that “The Church is a home with open doors, because she is a mother.” We lock our doors when we believe that others around us are a threat. To leave our doors open is to treat those around us as neighbors and friends. The Church, as mother, welcomes not only her children within but also her children without.

This is precisely how Francis partisans do the same thing that the integralists do: portray the Benedict Option as one of simple, crude retreat. As I say in the book, the retreat is not into closed communities. Rather, it is into ones that are somewhat separated from the world, for the sake of maintaining fidelity to our Christian identity. In a post-Christian (and increasingly anti-Christian) world, if you do not have some ground on which to take your stand, you will be assimilated by the broader culture. This is why some conscious distancing must happen. From The Benedict Option:

St. Benedict commands his monks to be open to the outside world—to a point. “The House of God will be wisely governed by wise men,” the Rule says. Hospitality must be dispensed according to prudence, so that visitors are not allowed to do things that disrupt the monastery’s way of life. For example, at table, silence is kept by visitors and monks alike. As Brother Augustine put it, “If we let visitors upset the rhythm of our life too much, then we can’t really welcome anyone.” The monastery receives visitors constantly who have all kinds of problems, and who are seeking advice, help, or just someone to listen to them, and it’s important that the monks maintain the order needed to allow them to offer this kind of hospitality.

Rather than erring on the side of caution, though, Father Benedict believes Christians should be as open to the world as they can be without compromise.

“I think too many Christians have decided that the world is bad and should be avoided as much as possible. Well, it’s hard to convert people if that’s your stance,” he says. “It’s a lot easier to help people to see their own goodness and then bring them in than to point out how bad they are and bring them in.”

The power of popular culture is so overwhelming that faithful orthodox Christians often feel the need to retreat behind defensive lines. But Brother Ignatius warns that Christians must not become so anxious and fearful that they cease to share the Good News, in word and deed, with a world held captive by hatred and darkness. It is prudent to draw reasonable boundaries, but we have to take care not to be like the unfaithful servant in the Parable of the Talents: punished by his master for his poor, fearful stewardship of the master’s property.

“The best defense is offense. You defend by attacking,” Brother Ignatius said. “Let’s attack by expanding God’s kingdom—first in our hearts, then in our own families, and then in the world. Yes, have to have borders, but our duty is not to let the borders stay there. We have to push outwards, infinitely.”

This is why I think that the Benedict Option model is the only one I’ve yet seen that has within it the capacity to renew, organically, this world — and it will take a long time. I can’t see that Pope Francis has the least concern with whether or not Catholics know their faith, affirm it, and strive to live obedient to its teachings. You can’t give the non-Christian world what you don’t have. What’s the point of “going to the peripheries,” as Francis calls on Catholics to do, if you don’t know what you are supposed to tell the people when you get there.

Finally, I want to share with you some quotes I found from my 2016 interview with Russ Hittinger — material I did not use in The Benedict Option:

“Christopher Dawson used to say the secret to all spiritual reform in Latin Christianity is that there are movements from below that no pope or no bishop can cause, but there are ecclesiastical authorities above who can pick it out and promote it. This new life can’t be engineered from above. All the big religious orders came out from below. Even Ignatius and the Jesuits began as a group of college students at the University of Paris. The Franciscans were just a bunch of rich kids in Assisi. … When you get both of those aligned, things began happening, but it can’t be generated from bureaucracies.”

More:

“Just going out into the woods of Arkansas, that may work for some, but that is necessarily limited in scope. There’s another thing about liturgy too. Because I’m a Benedictine oblate, I’ve come to appreciate that liturgy, including the office, is profoundly formative. It’s not just a matter of doing good works and having the right moral opinions. There’s a very deep moral formation when there’s a common life around prayer. The Church in this country has never figured out, once the Catholics moved to the suburbs, how to form suburban parishes into anything like a Durkheimian community. They’re sacramental gas stations. At least the old urban parishes were communities at multiple levels. The church hasn’t figured out how to do that.”

And:

“It usually comes down to little and simple things. American Catholics are very generous, and they can take to big things that have a big purpose, but simple and little things, which is the way one has to learn anyway, we’re just not as skilled on that one. So at the end of MacIntyre’s book, we have to be patient, because whoever the spiritual genius is, the one who figures out a traditional way of living and praying together that is adaptable to our sociological conditions, whoever that genius is, or that group is, we don’t know.”

Political power can help protect churches from attacks from the state and other hostile powers that may arise. But political power cannot keep churches from becoming sacramental gas stations. In the Soviet Union, people stayed away from churches because the state terrorized them into cowering with fear. In the US, more of the young are staying away from church, even though they suffer no penalty by attending. That is not a problem that can be solved through politics — though it is a problem that is existential for the churches.

The post Gen. Flynn’s Trumpagelical Integralism appeared first on The American Conservative.

Adultery 1, Veritatis Splendor 0

From time to time, people ask me what I think of Veritatis Splendor (“The Splendor of Truth”) — not the John Paul II encyclical, but the planned Catholic community in East Texas. If you watch the promotional video, it’s clearly a Benedict Option-style community:

I tell inquirers I don’t know what to think about this project. I wish those people well, of course, but I didn’t know anything about any of its founders, or their plan, so I withhold judgment. When a writer for Crisis magazine reached out to me this spring, I told him as such. In the article, both the founder of the project and Bishop Joseph Strickland of Tyler, Texas, who openly promotes it in the video, said this isn’t a Benedict Option thing — which is weird, because it pretty obviously is.

In light of today’s news, I’m glad they distanced themselves from me. Simcha and Damien Fisher report that the Veritatis Splendor initiative is reeling after the revelation of a sexual affair between two of its leaders. Excerpts:

Kari Beckman was going to build Veritatis Splendor, a village of Catholic “true believers” in the heart of Texas. Now, after acknowledging an illicit relationship, reportedly with Texas Right to Life head and Regina Caeli board member Jim Graham, she’s moved out of the property’s luxury ranch and back to Atlanta, and has stepped down as executive director of Regina Caeli Academy and Veritatis Splendor.

As for the village, one $3 million loan later, not a single structure has yet been built on the land, and the members of Regina Caeli across the nation are left wondering if their homeschool tuition fees and bake sale fundraising dollars paid for the grandiose Tyler, Texas project, or for any of Beckman’s other, more clandestine activities of the past year.

Beckman, who founded the homeschool hybrid Regina Caeli Academy in 2003, sent a letter to the members of Regina Caeli at the end of last week acknowledging “a terrible lapse in judgment with a personal relationship.” Multiple sources confirmed the relationship was with Jim Graham. Beckman and Graham are both married. Beckman said she immediately sought forgiveness through the sacrament of confession, and then, months later, confessed to her husband. She said that she and her husband then both went to the board of Regina Caeli and told them “what had occurred,” and then stepped down as Executive Director.

Shortly before she stepped down, the Board of Directors received an anonymous letter alleging Beckman had carried on an illicit sexual relationship with Graham. Graham was also, until recently, on the Board of Regina Caeli, but his name has recently been removed from that site, along with Kari Beckman’s name. Beckman’s husband remains listed as a board member. Three other board members are no longer listed on the site, and Nicole Juba has been named acting Executive Director.

As the Fishers point out, there is a distinct lack of financial clarity around this project. Earlier this year, Simcha Fisher reported on her efforts to determine where the fundraising money is going, and to whom priests who will serve at the completed project will be responsible: she got nowhere, because they organizers gave her the runaround.

In the new story, there are more allegations of financial impropriety around the project:

But it’s not merely a matter of spiritual hypocrisy that distresses this and other Regina Caeli families. The anonymous letter-writer told us they also filed two complaints with the IRS on November 12 asking for an investigation of Beckman’s possible financial misuse of Regina Caeli funds. The complaints accused Regina Caeli of “using assets for personal gain” and “questionable fundraising practices.”

As one RCA [Regina Caeli Academies] parent put it, “We essentially bought them a ranch.”

And now we learn that Kari Beckman, mother of eight, has been cheating on her husband, allegedly with a married man.

This is incredibly discouraging for a number of reasons. The concept of the Veritatis Splendor community sounds appealing, in general, but based on what the Fishers report, it has been very shaky from the start. The fact that this one Benedict Option-style initiative is sinking because of bad planning and the sins of its founder does not negate the value of all experiments. But it does demonstrate the profound need for prudent planning and strong leadership. Bishop Strickland has done himself no favors here by going all-in on this project, which is in his diocese, but not of the diocese.

It reminds me in some ways of the scam the Society of St. John, a closeted gay cult within traditionalist Catholicism, pulled over two decades ago in Pennsylvania, with the help of the Bishop of Scranton. The SSJ told people that it wanted to found a traditionalist Catholic village. Bishop James Timlin co-signed a loan to help them buy property. It turned into a hot mess of lies and abuse. Timlin’s successor suppressed the SSJ. To be very clear, no sexual abuse has been alleged around the Veritatis Splendor project (sexual sin, like adultery, is not necessarily sexual abuse). But this does seem like a repeat of the SSJ debacle: raise money appealing to the desires of Catholic conservatives to live in a community of faith, and by drawing in a gullible bishop to give a de facto imprimatur to the project, and then watch it all fall apart when the sexual disorder of the leadership draws attention to financial and other problems with the project.

The post Adultery 1, Veritatis Splendor 0 appeared first on The American Conservative.

Annals Of Gaslighting: Armed Forces Edition

The Marine Corps, the smallest U.S. military force, has plans for a big overhaul designed to address its lack of diversity and problem with retaining troops.

The goal that’s driving what amounts to a cultural shift within the service, is for the Marines “to reflect America, to reflect the society we come from,” Gen. David Berger, commandant of the Marine Corps, said in an interview with NPR’s Morning Edition.

It’s not a matter of being politically correct or “woke,” he said.

The core of America’s strength lies in its diversity, Berger said, adding that the same is true for the military.

“Our advantage militarily is on top of our shoulders,” he said. “It’s not actually our equipment. We are better than anybody else, primarily because we don’t all think exactly alike. We didn’t come from the same backgrounds.”

No, it’s not wokeness. It’s not! Stop saying it is, bigot! Diversity is our STRENGTH !

!

Read or listen to it all. Do I even need to tell you that there is zero pushback from the NPR reporter? The purpose of this report was to reassure listeners that all is well with the Marine Corps, as it implements the same ideology that has conquered the leadership ranks of every other major institution in this country.

I wrote recently in this space about this same USMC plan (see “The Baizuocracy At War”). Do you think that listening to or reading that NPR report, the American people would grasp what’s really going on here? Do you think this official Marine Corps graphic celebrating the new approach occurs to Americans?

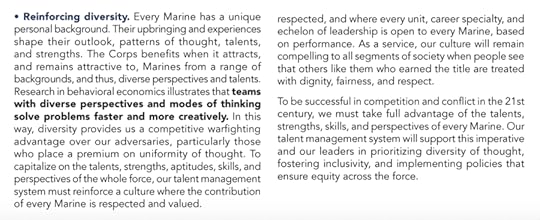

Here, from the USMC’s document (the one the commandant was on NPR defending), is the Corps’ new attitude:

The military, like every other bureaucracy that drinks the Kool-Aid, tells itself this lie. The truth is — this, based on my experience in the intentionally diverse workplace — is that hiring for any reason other than capability and competency ends up creating resentment and demoralization on the team. Once people understand that N. was a diversity hire, when N. fails to do the work, dumping it off on others, resentment builds. What makes it worse is the certain knowledge that to complain about it to one’s superiors would be to risk one’s job as a self-outed “bigot”.

The reader who first tipped me off to this said:

My comment is that the priority should be to put together a skilled, cohesive and highly trained military force that can be exceedingly lethal when necessary. The line that diversity provides us a competitive warfighting advantage over our adversaries is entirely absurd.

The beauty of the military I grew up in was the oneness of the soldiers, airmen and sailors and singular commitment to the mission whatever that may be. When that uniform went on, there was no differences or diversity. In times of battle, the cohesion and commitment to each soldier to his brother is what gets them through.

I recently met an active duty member of the armed forces who told me that the leadership of our military seems to be more interested in winning the culture war against unwoke soldiers, sailors, and airmen than in winning actual wars against America’s enemies.

My old TAC colleague Kelly Beaucar Vlahos, who covers military affairs, has a great piece today at The Spectator, talking about how hard questions have arisen about the condition of the military. She begins by talking about how USMC Lt. Col Stuart Scheller put his entire career on the line to speak out against corruption in the leadership ranks, in light of the Afghanistan debacle. More:

Scheller was relieved of his command, jailed briefly, and court-martialed, but a largely sympathetic military judge gave him a reprimand and $5,000 fine (much to the consternation of the prosecution). While the military community was split over his punishment for violating code, there was clearly something more powerful going on. Scheller’s decision to put his career on the line to demand accountability became a mantra, not just about the August evacuation — but a reckoning of the last two decades.

(Ret.) Col. Doug Macgregor, writing in the American Conservative in October:

The generals always knew that the public admission of failure would not simply throw 20 years of graft and deceit into sharp relief; such an admission would expose the four stars themselves to serious scrutiny. To explain the rapid collapse of the U.S.-backed Afghan state and the inexcusable waste of American blood and treasure, the American people would discover the long process of moral and professional decline in the senior ranks of the Army and the Marines, their outdated doctrine, thinking, and organization for combat. For the generals it was always better to preserve the façade in Kabul, propping up the illusion of strength, than face the truth.

It was as if the Afghanistan debacle had finally ripped the last scab off the military’s role in the failed enterprise. Suddenly the superstar warrior/monk generals for whom the mainstream media had written endless paeans, before which members of Congress had bowed and scraped, were under the garish light of delayed circumspection.

As a result, there is plenty of talk about what went wrong and what shape the military is in for the future. And certainly just focusing on “the generals” would be shortsighted. This is about the institution — for which America’s trust is actually plummeting. So can the military really afford not to take stock of the cultural, institutional — and yes, political — changes that have swept over it in the last 20 years or more?

“My major concern is military effectiveness,” says (Ret.) Marine Corps. Capt. Dan Grazier, who served tours in Iraq and Afghanistan in a tank battalion and is now a military analyst at the Project on Government Oversight, “that in the rare event where the military does need to be deployed that we can be the most effective, lethal force possible when the situation calls for it.”

After interviews with several infantry veterans who served in the post-9/11 wars, The American Spectator picked up on a familiar theme as the main obstacle for rebuilding the forces and the faith: leadership corrupted by careerism and influenced by outside interests that don’t always coincide with the interests of the national defense.

The Vlahos article does not focus on wokeness, note well. But there’s a definite tie-in. Look:

(Ret.) Army Lt. Col. Daniel Davis, who also served multiple tours in Iraq and Afghanistan, blames the influence of private industry, particularly its cozy relationships inside the Pentagon for the dysfunctional nature of procurement and acquisitions. Private defense firms spent $1 billion lobbying Washington since 2001, and in return received some $7 trillion in taxpayer funds over the course of the post-9/11 wars — that’s half of the $14 trillion spent overall.

Davis says this amount of money sloshing around has created enormous boondoggles that leave the forces ultimately high and dry (and the contractors fat and happy). Chew on this: the Air Force now wants to cut more than 87,000 pilot training hours because aircraft sustainment costs soared to $1 billion this year.

All these top generals who have gone ga-ga over Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, are making themselves more attractive to corporate culture, including defense contractor culture, by demonstrating their loyalty to the successor ideology. More:

Davis and Grazier say the problem is too much money and industry influence going on the E-Ring to get at it. Thus the revolving door: one POGO report from 2008 to 2018 found that 280 high ranking officials became lobbyists, board members, executives, or consultants for defense contractors within two years of leaving the service. Military officers going through the revolving door included 25 generals, 9 admirals, 43 lieutenant generals, and 23 vice admirals.

And then they come back. Secretary of Defense Mark Esper was a Raytheon lobbyist ($27 billion in federal contracts in 2020); Secretary of Defense Patrick Shanahan came from Boeing ($21 billion), Secretary of the Army Ryan McCarthy bounced over from Lockheed ($74 billion), and current Secretary of Defense Austin was a paid member of the Raytheon board after leaving the service in 2016.

Though the awokening of our armed forces began under Obama, Esper, a Trump appointee (!), was a major force pushing the awokening of our armed forces. Two years ago, I talked to a Raytheon management employee, a veteran and a conservative Christian who told me he was on the verge of quitting because he could not accept the compulsion to celebrate LGBT Pride that was now expected of Raytheon managers. Note well: he wasn’t talking about tolerance, but about being forced to affirm Pride as a condition of his job as a manager in this defense contracting giant. The revolving door brings the infection of wokeness from corporate board rooms to the Pentagon.

Now do you understand better why NPR’s story is gaslighting? The media already have accepted the successor ideology as dogmatically true. It wouldn’t even occur to many of these reporters that there is another side to this issue, or a down side.

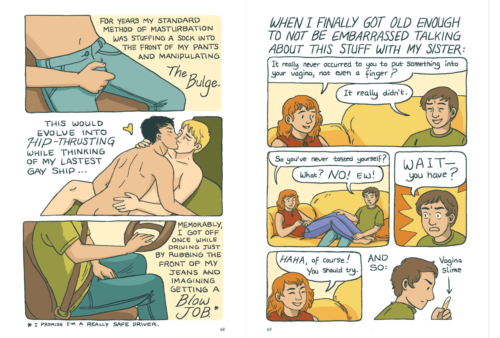

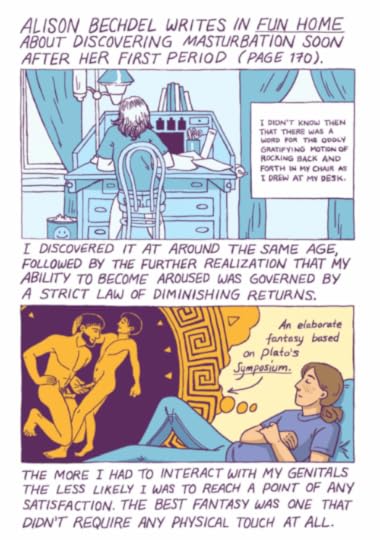

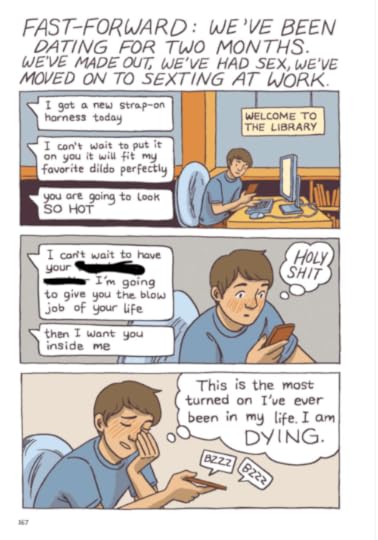

This is tangential, but I think it applies. I wrote over the weekend about how NPR gaslit its audience on the controversial book “Gender Queer” by Maia Kobabe. The book is being removed from school library shelves here and there, after parents complain that its pornographic content is inappropriate. In my post, I observed that NPR (on the web version of its story) only showed the most innocuous pages from the graphic memoir, and did not show the parts that have parents up in arms. If you depended on NPR to tell you about this controversy, you would think that this is clearly nothing more than right-wing bigoted parents up in arms over nothing. I posted on that blog post images from the book that have upset parents. You might think that parents are overreacting, but you should at least understand what they’re actually reacting to; the dishonest sleight of hand from NPR’s 1A program is misleading.

Interestingly, a prominent Yale professor — a man who is a liberal of real courage, who stood up to a woke campus mob in 2015 — had this to say about it on Twitter this morning:

Here is a tweet with images deemed most offensive. My sense is that having such a book available in a high school library is in keeping with the sexual awareness of most students that age. And similar content should be available for straight students, too. https://t.co/Nlne4Y4rXB

— Nicholas A. Christakis (@NAChristakis) November 15, 2021

Read the comments — Prof. Christakis is being roasted by his followers. My guess is that his thinking this stuff is fine for teenagers (versus the very, very strong pushback he’s getting from his Twitter followers) is a reflection of how cut off from ordinary people American elites — especially academic elites — are. It simply doesn’t occur to them that people would find a graphic memoir depicting minors performing fellatio as part of a journey to discovering that the protagonist is “gender queer” as outrageously inappropriate for a school library. Look, I respect Christakis, who was brave when it counted, but I think his reaction is quite telling. And I think it has a lot to do with why our media are so untrustworthy, and why the successor ideology having conquered the senior officer class in the US military makes our country weaker. It’s all based on ideological lies.

It is long past time for Republican members of Congress to cease and desist their knee-jerk deference to the military, and to push back on this corruption — the ideological corruption, as well as the revolving door between the Pentagon and defense contractors. We haven’t been able to win a war in a long time. Just you wait until we get into a major one. Is it going to take a catastrophe like that to finally force reform? Note well that the Russian Imperial army’s loss in the Russo-Japanese War was a major factor in undermining the Russian people’s confidence in the Tsarist government, which was overthrown in 1917. This stuff matters.

UPDATE: This news just in:

The U.S. Air Force can’t provide its pilots with additional flight hours in part because aircraft sustainment costs have surged to roughly $1 billion, top service leaders told lawmakers Tuesday.

While flying hours do not directly equate to how experienced or proficient a pilot is, there have been concerns about declining cockpit time for years, as this is crucial to maintaining aircraft skills.

According to its fiscal 2022 budget request, the service instead wants to slash flight time by roughly 87,500 hours. The planned reduction is due to the demands of weapon system sustainment, or WSS, which impacts aircraft availability, said Lt. Gen. David Nahom, deputy chief of staff for plans and programs.

The USAF veteran who sent the link comments:

This isn’t good. The amount of resources we allotted to flight training hours has given us our edge over competitors.

Well, clearly he’s wrong. Doesn’t he know that Diversity Is Our Strength ?

?

UPDATE: A reader writes:

25 years of service and anxiously awaiting retirement that I can’t achieve until I get my Covid shots. For those not in the military, it is worse than you wrote. Those are only the wave tops. It will get worse until large scale war happens, we get our asses kicked, and are forced to refocus to win.

The post Annals Of Gaslighting: Armed Forces Edition appeared first on The American Conservative.

November 14, 2021

Annals Of Media Gaslighting: Gender Queer Edition

Last week, the Kyle Rittenhouse trial provided us with yet another real time example of the difference between reality and the way the mainstream media construes reality. If you watched any of the trial proceedings, you would know that what happened there, and what many in the media said happened there, were not the same thing. I don’t believe the media are consciously lying, though perhaps I’m being charitable. I believe that most journalists are so sold out to their own narrow and biased way of seeing the world that they cannot imagine that they could be wrong about anything.

This week it was Rittenhouse. Last week, and in the previous weeks, it has been the refusal of the MSM to deal with the reality of race radicalism being mainstreamed in public schools. Today I want to talk about the lies that the NPR show 1A told in an effort to shield from scrutiny and criticism a book that has been targeted by some angry parents, who want to know what the hell it is doing on the shelves of their kids’ school library.

The book is Gender Queer, a graphic memoir by a woman who is now … well, I don’t know. Genderqueer. It’s about her transition away from what she was born into whatever she identifies as now. 1A recently spent time talking to the author, Maia Kobabe, and deploring the bigots who attempt to get the book removed from schools.

On the web page for the interview, 1A displays several pages from Gender Queer. Take a look at them; they’re relatively innocent. I mean, a conservative like me doesn’t think there’s a place for any of this in a school library, but I can imagine someone who is more moderate looking at the examples in the 1A story and thinking that conservatives are making a big deal about nothing. Which, of course, is what NPR wants you to think.

You know which images from Gender Queer 1A did not show its listeners? These (I’ve altered the first one, for obvious reasons):

You get the idea. If NPR’s 1A had been interested in actually informing its viewers about the controversy, it would have shown one or two of these images along with the more sedate ones. But this is not about informing listeners; this is about manufacturing consent to progressive radicalization. In other words, this is propaganda.

Let me be clear: I don’t object at all to Kobabe and these other authors coming on the program to give their side to the story. What I greatly object to is the de facto lying by NPR about the nature of the controversy involving that particular book. The governor of South Carolina has ordered an investigation to find out how that pornographic book made it onto high school library shelves there. If you depend on NPR to tell you why the book offends people, you would not understand the controversy at all.

This is how NPR rolls these days. As longtime readers know, I have long been a booster of NPR, even though it has been generally opposed to my own politics and cultural sensibilities. I used to appreciate its reporting, and I almost always found interesting things to listen to on the network. But since the Trump years, the Great Awokening swept through NPR, and now it seems that every other story talks about identity politics in one form or another. If you spent an afternoon listening to NPR and playing a drinking game in which you slammed a shot every time the network referred to race, gender, sexuality or immigration, you would be passed out before teatime.

I wonder, though, how many people who listen to and financially support NPR realize how inaccurate the picture of the world NPR’s journalism can be. It seems to me that if I wanted to defend the presence of queer books in public school libraries, I would want to know what, precisely, parents were objecting to. Trust me, the way 1A handled the Gender Queer story is more and more common whenever NPR’s news reporting intersects with wokeness. It’s as if the newsroom there simply cannot bring itself to imagine a world of people outside its bubble.

I see NPR, The New York Times, the Washington Post, and other mainstream media as engaged in an active attempt to render people like me into hate figures, and to convince people that we have no case for our views. The Times and the Post, though, do not depend on money from the pockets of people they demonize. NPR? From NPR’s website:

Why do taxpayers continue to subsidize dishonest journalism that demonizes so many of us? This is a question it would be good for the Congress to take up the next time Republicans are in the majority. The issue of NPR funding has come up over and over for all my journalism career. I have always spoken out against conservatives who want to defund NPR, because I have really loved NPR over the years, have friends who work there, and have cherished it. Some years back, NPR welcomed me and my daughter for a tour of headquarters. I’m very grateful to them for their kindness. I hate where I’ve landed re: NPR. I feel so bitterly about this issue because I loved NPR so much as it once was. It used to be a significant part of my life. But you get to the point where you realize that these people honestly can’t stand folks like you, and don’t want to treat you with fairness and respect, even within their generally liberal reporting agenda. Which is what NPR always had — but I long believed that NPR, though liberal, tried to be fair, and I respected and appreciated that. I wonder if the easing out through retirement of older NPR journalists, and the rise of young radicals to replace them — young reporters who believe that seeking fairness and objectivity is to aid and abet evil conservatives — is to blame.

Believe me, I’m not singling out NPR. They all do it. I guess it bothers me more about NPR because I feel like I’ve lost an old friend.

Andrew Sullivan wrote on his Friday Substack about all the recent MSM fails.Rittenhouse. The Covington Catholic boys. Russiagate — and several more.

We all get things wrong. What makes this more worrying is simply that all these false narratives just happen to favor the interests of the left and the Democratic party. And corrections, when they occur, take up a fraction of the space of the original falsehoods. These are not randos tweeting false rumors. They are the established press.

And at some point, you wonder: what narrative are they pushing now that is also bullshit? One comes to mind: the assurance that the insane amount of debt we have incurred this century is absolutely nothing to be concerned about because interest rates are super-low and borrowing more and more now is a no-brainer. But when inflation spikes and sets off a potential spiral in wages to catch up, will interest rates stay so quiescent? And if interest rates go up, how will we service the debt so easily?

I still rely on the MSM for so much. I still read the NYT first thing in the morning. I don’t want to feel as if everything I read is basically tilted through wish-fulfillment, narrative-proving, and ideology. But with this kind of record, how can I not?

The post Annals Of Media Gaslighting: Gender Queer Edition appeared first on The American Conservative.

November 12, 2021

Prof Walks Before They Make Him Run

I received this message yesterday from an occasional correspondent, a veteran college professor. He has given me permission to post it, with the proviso that I slightly edit it to preserve his identity:

I’m in my last semester at my college, having started here decades ago, when it was a more open, more tolerant place. This was a university that while its faculty leaned left (And what faculty at a state university does NOT lean left?), there still existed a commitment to the last vestiges of academic liberalism, free speech, and real diversity. The curriculum was a fairly classical one in that and students received the kind of educations that were not markedly different than what previous generations had enjoyed.

Our student body decidedly is not elite. Many are first-generation college students, a good portion of our students are African American, and our entrance standards are not difficult. In my own teaching experience here, I have had students who probably could have done well anywhere and others that probably didn’t belong in college at all. (That is fine; college is not for everyone, and I strongly believe that there are many good jobs in the trades that for many people would be much more fulfilling than becoming a bureaucrat, which is many graduates become these days.

I prefer the non-elite students to elites, who have a ridiculous sense of self-entitlement and who always are looking for new and better ways to be offended. Non-elites tend not to become activists because they are not full of themselves or believe the rest of the world exists for their amusement. For my entire career here, I have had students of all backgrounds, races, nationalities, and orientations and have found the experience very rewarding and would do it again.

Unfortunately, the university where important things once mattered is being transformed into a place where everything is politicized, and a politicized place is a sick society that, in your words, lives by lies. We now have a Diversity Officer who, in reality, is the chief political officer on campus, and she is trying to turn as many students as possible into campus activists ready to pounce at the next alleged injustice. She sent out an alert not long ago to warn that there had been an act of “cultural appropriation” on campus, and that it was being investigated.

First, “cultural appropriation” is a term that didn’t exist just a few years ago but now has been elevated to a Crime Against Humanity. In the modern list of cultural crimes, “cultural appropriation” can rank from a white person in blackface to someone wearing a sombrero, and I suspect the list will continually grow until a Caucasian singing a spiritual is handcuffed and dragged off stage by Diana Moon Glampers herself. Nonetheless, no one was told what this alleged Crime Against Humanity was or why we needed to have a campus alert. (We get those at times when a bear is seen running on campus.)

While no one yet is required to list one’s pronouns, we already have faculty members doing it and it only is a matter of time until the practice is mandatory. We already have had to undergo diversity training in which we are told that the Golden Rule really is racist and that the Platinum Rule (Do unto others as THEY would like) which means that any action that one can twist into an act of racism/sexism/anti-trans/anti-gay/etc. is treated as though the perpetrator intended for it to happen — even if it is obvious that there is no malintent. It doesn’t matter; only the perception of the “victim” is important.

In practice, the most innocent and well-meaning comment or gesture can be interpreted as a racist, hostile action which demands justice, and that usually means humiliation, firing, or some other consequence visited upon a human being who then is stripped of all humanity and treated as yesterday’s garbage. We have seen this in practice in the former USSR, Eastern Europe, China, and elsewhere. Having taught in China, I have first-hand experience seeing what happens in a society where everything is politicized and where real-live political officers abound. (You can tell who the Communist Party members are, as they have nicer clothes and drive better cars.)

Now, in my classes I have gone into a lot of detail about things that have happened in U.S. History, the lynching, the discrimination, and the horror that went with it. I’ve never sugarcoated our history but neither have I presented things the way our political officers want them portrayed, so all of my teaching is racist, etc. You get the picture.

I’m not waiting around until I am accused of a Crime Against Humanity such as “misgendering” someone or not going to the right church. I’m old enough to retire, so that is what I will do. Interestingly, the old-line Democratic liberals on campus also are aghast at what they are seeing. These movements are being inspired and directed by people whose mindset is totalitarian. At the present time, there are still liberals on campus that do not go along with what is happening, but soon enough they will be gone and all that will be left are those that believe all of life should be about political propaganda. I truly fear for our future.

I have a Black wife, Black in-laws, and Black children, but none of that counts for anything in this new world on campus. Thanks to Intersectionality and Critical Theory, the only thing that matters is conformity to the latest iteration of the Sexual Revolution and whatever ideological organization George Soros wants to bankroll, such as Kendi’s Anti-Racism Center or Black Lives Matter. Sadly, these folks rail about economic inequality between Blacks and whites, but then pursue political and economic policies that guarantee that the economic gaps only will grow larger. Maybe that is their plan; create terrible conditions for marginalized people, rail about the situation, and then demand money to fight the problem. Wash, rinse, repeat.

The post Prof Walks Before They Make Him Run appeared first on The American Conservative.

November 11, 2021

Normalizing Pedophiles

Take a look at this:

This non-binary assistant professor at Old Dominion University is trying to normalize the term MAP (Minor Attracted Persons) pic.twitter.com/riD6TdIt8k

— Libs of Tik Tok (@libsoftiktok) November 12, 2021

A description from the academic publisher’s website of the book Allyn Walker has written, and is talking about:

Challenging widespread assumptions that persons who are preferentially attracted to minors—often referred to as “pedophiles”—are necessarily also predators and sex offenders, this book takes readers into the lives of non-offending minor-attracted persons (MAPs). There is little research into non-offending MAPs, a group whose experiences offer valuable insights into the prevention of child abuse. Navigating guilt, shame, and fear, this universally maligned group demonstrates remarkable resilience and commitment to living without offending and to supporting and educating others. Using data from interview-based research, A Long, Dark Shadow offers a crucial account of the lived experiences of this hidden population.

Watching that short clip of the interview with Walker, and reading that description, gosh, it sure seems like the next crusade of the genderqueer brigade is to normalize pederastic desire — exactly as many of us figured would happen.

I read the introductory chapter on Google Books. It’s important that I quote it at length, for the sake of clarity. Here we go:

B4U-ACT is a group of pedophiles who want to manage their desire so that they do not commit a crime, and who come together to help each other bear the burden. Knowing nothing more about this group than that, I can see real value in it. But the last two lines are big red flags that we are going down the path of normalization.

Here Walker talks about a conversation with a journalist who has covered this topic, and who warns that it’s dangerous to talk about, because people assume that if you work to normalize pedophiles to any degree, you are setting children up for sexual assault:

Allyn Walker is playing with fire. Surely there must be some way to get these suffering people the help they need without moving towards considering pedophilia just one more “sexual orientation.” Because if it ever should become that, we are halfway to legalizing it, following the same path that standard homosexuality took. If sexual desire is the equivalent of identity, and if to sexually desire minors is at the core of one’s identity, then how can we stigmatize or otherwise suppress pedophiles if we recognize that other kinds of sexual minorities have civil rights?

Anybody who has lived through the last twenty years knows that sexual identity and the law is a slippery slope. This needs to be crushed right now, without apology.

The clip comes from this interview Walker did with Noah Berlatsky of the Prostasia Foundation, which bills itself as “a new kind of child protection organization,” but which amounts to a very sophisticated attempt to normalize pedophilia.

Berlatsky is a weird middle-aged dude, a former contributor to NBC Online, The Atlantic, and other sites, who is familiar from Internet controversies. Among other things, he has written about how parents are an oppressor class, and how the biggest threat to “child sex workers” are the police.

Here, from the website, is one of Berlatsky’s Prostasia co-workers:

Just what we need: a hooker/childcare expert/kink educator. Totally normal, totally fine.

The post Normalizing Pedophiles appeared first on The American Conservative.

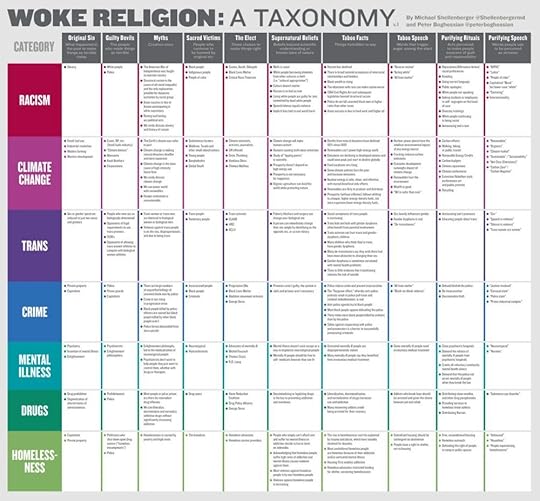

Taxonomy Of Woke Religion

Here’s a fantastic graphic by Peter Boghossian and Michael Shellenberger, two anti-woke liberals:

Here’s a Shellenberger essay explaining why wokeism is a religion. He begins by pointing out how the devoutly woke believe things that are demonstrably untrue, but that are defended fanatically by the true believers. More: