Nina Munteanu's Blog, page 4

April 22, 2021

Happy Earth Day! Celebrate with Eco-Fiction ... Then Plant a Tree!

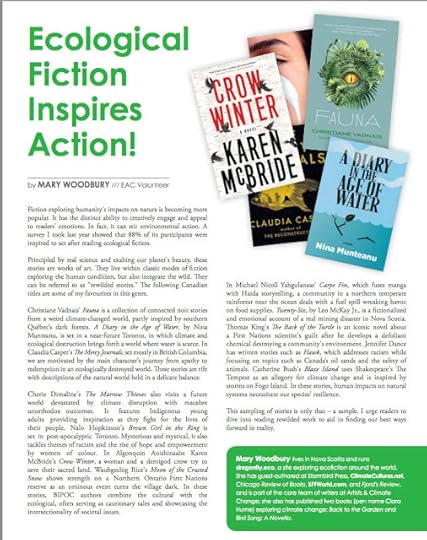

Mary Woodbury, author and publisher of Dragonfly.eco, lists some of her favourite “Eco-Fiction [that] Inspires Action” in the Spring 2021 issue of Ecology & Action. Among them is Nina Munteanu’s eco-novel “A Diary in the Age of Water”:

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications in 2020. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications in 2020. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

March 23, 2021

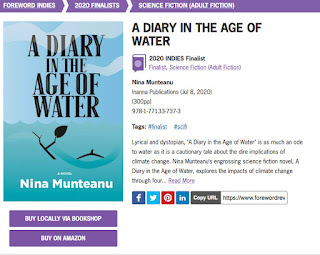

"A Diary in the Age of Water" Finalist for Foreword 2020 Book of the Year Award

On World Water Day, Foreword Reviews declared my dystopian cli-fi eco-novel A Diary in the Age of Water a finalist for their INDIE Book of the Year Award in the science fiction category for 2020.

The story follows the climate-induced journey of Earth and humanity through four generations of women, each with a unique relationship to water. The novel explores identity and our concept of what is "normal"--as a nation and an individual--in a world that is rapidly and incomprehensibly changing.

A Diary in the Age of Water has already received much praise by reviewers and readers. Reviewer Lee Hall included it in his top twenty books that he read and reviewed in 2020: "...one of the most powerful books I've ever read...A truly important once in a generation read that flows like a wild river right through your imagination and heart."

A Diary in the Age of Water was considered by reviewers of The Winnipeg Free Press one of the top twenty books reviewed in 2020. Reviewer Joel Boyce writes:

"Like the works of Margaret Atwood and George Orwell, whose flavours seep through, this story works as both literature and persuasion."

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications in 2020. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

February 17, 2021

Nina Munteanu Talks Water and Writing on Minddog TV

I was recently interviewed by Matt Nappo on Minddog TV in New York, where we talked about the science and magic of water, climate change and how to not become cynical, the process of writing, what scares us and what takes us through it into great storytelling.

Here’s the interview:

January 12, 2021

"The Best Books I Have Read This Year--2020

Author and reviewer Lee Hall recently compiled his list of the twenty best books he read in 2020. Says Lee:

It’s hard to believe that we’ve got to this point but we have. For all the words you could use to describe the dumpster fire that is and was 2020 I am going to use the word grateful.

Grateful for the authors who have provided me with not only an escape through their wonderful works but grateful to them for providing a vital centre pillar of content for this blog – reviews. Some of these creators have become friends and important connections in the world of online authoring for me. This post is dedicated to them and the best books I have read this year.

While the criteria of ‘best books’ is derived mainly from my own personal taste it is also influenced by how many views the review got on here along with my admiration for the author. These works are an extension of some wonderful personalities who make up an incredible community.

A Diary in the Age of Water was among the books Lee chose for 2020 reading:

‘A Diary in the Age of Water’ by Nina Munteanu

A truly important once in a generation read that flows like a wild river right through your imagination and heart…– Quote from my review

I’m being 100% serious when I say ‘A Diary in the Age of Water’ is one of the most powerful books I’ve ever read. For what it stands for is truly a statement towards our own damning of this beautiful planet and our most precious resource – water. Canadian Author Nina Munteanu has put together a masterful look at where we could possibly end up if we don’t act. This one was another Reedsy Discovery find and thus totally justified my joining of the platform well and truly!

LEE HALL

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications in 2020. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books.

July 9, 2016

Flight Behavior

Barbara Kingsolver’s 2012 novel Flight Behaviorwas, according to The Globe and Mail, the first novel that dealt “specifically, determinedly and overtly with climate change. [And] only Kingsolver could pull it off.”

Barbara Kingsolver’s 2012 novel Flight Behaviorwas, according to The Globe and Mail, the first novel that dealt “specifically, determinedly and overtly with climate change. [And] only Kingsolver could pull it off.”The premise of climate change and its affect on the monarch butterfly migration is told through the eyes of Dellarobia Turnbow, a rural housewife, who yearns for meaning in her life.

The book starts with her scrambling up the forested mountain—slated to be clear cut—behind her eastern Tennessee farmhouse; she is desperate to take flight from her dull and pointless marriage of myopic routine. The first line of Kingsolver’s book reads: “A certain feeling comes from throwing your good life away, and it is one part rapture.” Dellarobia thinks she’s about to throw away her ordinary life by running away with the telephone man. But the rapture she’s about to experience is not from the thrill of truancy; it will come from the intervention of Nature:

A small shift between cloud and sun altered the daylight, and the whole landscape intensified, brightening before her eyes. The forest blazed with its own internal flame. “Jesus,” she said, not calling for help, she and Jesus weren’t that close, but putting her voice in the world because nothing else present made sense…The mountain seemed to explode with light. Brightness of a new intensity moved up the valley in a rippling wave. Like the disturbed surface of a lake. Every bough glowed with an orange blaze. “Jesus God,” she said again…Trees turned to fire…The flame now appeared to lift from individual treetops in shows of orange sparks, exploding the way a pine log does in a campfire when it’s poked. The sparks spiraled upwards in swirls like funnel clouds….It was a lake of fire, something far more fierce and wondrous than either of those elements alone. The impossible…She was on her own here, staring at glowing trees. Fascination curled itself around her fright. This was no forest fire. She was pressed by the quiet elation of escape and knowing better and seeing straight through to the back of herself, in solitude. She couldn’t remember when she’d had such room for being. This was not just another fake thing in her life’s cheap chain of events, leading up to this day of sneaking around in someone’s thrown-away boots. Here that ended. Unearthly beauty had appeared to her, a vision of glory to stop her in the road. For her alone these orange boughs lifted, these long shadows became brightness rising. It looked like the inside of joy, if a person could see that. A valley of lights, and ethereal wind. It had to mean something.

Although Dellarobia doesn’t realize it yet, that moment proves life-changing for her: no longer “watching a nearly touchable lover behind her eyelids but now seeing flame in patterns that swirled and rippled. A lake of fire.” That day, she participates in the sheep shearing, greatly distracted from a new awakening to the power and wisdom of Nature:

Although Dellarobia doesn’t realize it yet, that moment proves life-changing for her: no longer “watching a nearly touchable lover behind her eyelids but now seeing flame in patterns that swirled and rippled. A lake of fire.” That day, she participates in the sheep shearing, greatly distracted from a new awakening to the power and wisdom of Nature:“Watch and learn, Dellarobia thought, feeling an unaccustomed sympathy for the animals, whose dumb helplessness generally aggrieved her. Today they struck her as cannier than the people. If the forest behind them burned, these sheep would come to terms with their fate in no time flat. Flee or cower, they’d make their best call and fill up their bellies with grass to hedge their bets. In every way more realistic about their circumstances. And the border collies too. They would watch, ears up, forepaws planted, patiently bearing with the mess made by undisciplined humans as the world fell down around them.”

Climate change—and all that is associated with it—is altering our planet irreparably, one sure-footed step at a time.

Climate change—and all that is associated with it—is altering our planet irreparably, one sure-footed step at a time.Entomologist Ovid Byron (in response to a reporter’s suggestion that scientists disagree about whether it’s happening and whether humans have a role) talks about the tipping point we’ve ignorantly raced past: “The Arctic is genuinely collapsing. Scientists used to call these things the canary in the mine. What they say now is, the canary is dead. We are at the top of Niagara Falls… in a canoe. There is an image for your viewers. We got here by drifting, but we cannot turn around for a lazy paddle back when you finally stop pissing around. We have arrived at the point of an audible roar. Does it strike you as a good time to debate the existence of the falls?” Ovid (Kinsolver) effectively reiterates what most scientists know: that we have already crossed the tipping point of no return. There is no point in looking back to restore what we are losing; there is only the option of looking forward to adapt—and assist—as best we can.

The irony is that, as audible a roar climate change is for scientists like Ovid, to most of us climate change whispers insidious notes too subtle for us to comprehend or care about.

The irony is that, as audible a roar climate change is for scientists like Ovid, to most of us climate change whispers insidious notes too subtle for us to comprehend or care about.How does one grasp the gravity of a few degrees difference in temperature? The subtle rise in sea level? The almost imperceptible shift in the migratory pattern of a bird? When we are already so disconnected from Nature and lack the sensibilities—and compassion—to recognize and empathize with her trials and tribulations. Kingsolver suggests—quite accurately, I think—that only scientists can truly appreciate the portent of these subtle changes because it speaks in a language only they can understand.

Flight Behavior resonated with Kristen Poppleton, climate change educator, who shared that Kingsolver was spot on in her “description of the grief and sensation of loss most of us in this business of climate change education, communication and science carry around daily.” This type of grief is so prevalent, in fact, that it has a name:

solastalgia

. Poppleton empathized with scientist Ovid’s grief as Kingsolver writes, “The one thing most beloved to him was dying. Not a death in the family…but maybe as serious as that. He’d chased this life for all his years; it had brought him this distance…Now began the steps of grief. It would pass through this world…while most people paid no attention.”

Flight Behavior resonated with Kristen Poppleton, climate change educator, who shared that Kingsolver was spot on in her “description of the grief and sensation of loss most of us in this business of climate change education, communication and science carry around daily.” This type of grief is so prevalent, in fact, that it has a name:

solastalgia

. Poppleton empathized with scientist Ovid’s grief as Kingsolver writes, “The one thing most beloved to him was dying. Not a death in the family…but maybe as serious as that. He’d chased this life for all his years; it had brought him this distance…Now began the steps of grief. It would pass through this world…while most people paid no attention.” Flight Behavior isn’t so much about climate change and its effects and its continued denial as it is about our perceptions and the actions that rise from them: the motives that drive denial and belief. This is no more apparent than in Kingsolver’s use of biblical references of fire and flood. Both water and flame are potent cleansing agents. They evoke powerful change. They represent givers—and takers—of life. Together, fire and water frame Kingsolver's book with a strong metaphoric beginning and end that embraces creative destruction.

Kathleen Byrne of The Globe and Mail writes: “We begin in flames and end in flood, which suits the biblical (and scientific) parameters of a novel whose setting in Tennessee’s Appalachian mountains is the nexus of a God-fearing religious literalism and an untaught but unbudging righteousness that finds expression in the view that “weather is the Lord’s business.”

To Dellarobia’s question to Cub, her farmer husband, “Why would we believe Johnny Midgeon about something scientific, and not the scientists?” he responds, “Johnny Midgeon gives the weather report.” Kingsolver writes: “and Dellarobia saw her life pass before her eyes, contained in the small enclosure of this logic. All knowledge measured, first and last, by one’s allegiance to the teacher.”

Ovid shares a terrible insight about science and our perceptions of scientists with Dellarobia: “There are always more questions. Science as a process is never complete. It is not a foot race, with a finish line.... People will always be waiting at a particular finish line: journalists with their cameras, impatient crowds eager to call the race, astounded to see the scientists approach, pass the mark, and keep running. It's a common misunderstanding, [Ovid] said. They conclude there was no race. As long as we won't commit to knowing everything, the presumption is we know nothing.”

The grief that Poppleton feels, voiced by Kingsolver through her character Ovid, is really a grief for us, for the “home” we grew up in and love. The world we made. Near the end of Kingsolver’s book, Dellarobia makes this observation: “Mistakes wreck your life. But they make what you have. It's kind of all one…it's no good to complain about your flock, because it's the put-together of all your past choices.”

We—humanity—may not be around here for much longer. Nature will endure without us. Planet Earth will continue, in some form and Nature and life will endure, evolve, and flourish—in its own way. It will change, perhaps grow more unruly than it is already, but Gaia will continue after she has kicked us off. Ecologists have long recognized the pattern of colonization, exploitation, decadence and succession. How hubristic of humanity not to include itself in that cycle. The cycle of continuing change. We grasp—we clamor—for the world we knew—even as we senselessly impose irreparable change. Shaving forests to the ground so water has no where else to go but down and in a torrent. Creating hot deserts by diverting great rivers somewhere else. Mining vast oil and mineral reserves by scraping the earth until it “bleeds” from unhealable wounds.

Evolution and Nature march on, greater than us, encompassing us—whether we recognize it or not—in ways we can’t imagine (and science is only beginning to discover). Our vast Universe is so much more than we are capable of even imagining.

Flight Behavior is a multi-layered metaphoric study of “flight” in all its iterations: as movement, flow, change, transition, and transcendence.

Flight Behavior is a multi-layered metaphoric study of “flight” in all its iterations: as movement, flow, change, transition, and transcendence.Kingsolver ends her book with Dellarobia caught in a mountain flood that may take her life; yet, she remains suspended—transfixed in the moment of the miracle unfolding before her. The monarchs survived the winter and are taking flight:

“The vivid blur of their reflections glowed on the rumpled surface of the water, not clearly defined as individual butterflies but as masses of pooled, streaky color, like the sheen of floating oil, only brighter, like a lava flow. That many.

She was wary of taking her eyes very far from her footing, but now she did that, lifted her sights straight up to watch them passing overhead. Not just a few, but throngs, an airborne zootic force flying out in formation, as if to war…Her eyes held steady on the fire bursts of wings reflected across the water, a merging of flame and flood. Above the lake of the world, flanked by white mountains, they flew out to a new earth.”

Barbara KingsolverAnd a new earth is what we can be sure of. Whether we’ll be there is debatable—unless we too change.

Barbara KingsolverAnd a new earth is what we can be sure of. Whether we’ll be there is debatable—unless we too change.Interview with Simon Rose

My guest today is Simon Rose, an author of science fiction and fantasy novels for children and young adults, with a recent novel,

Future Imperfect

that will thrill your socks off. I met Simon some time ago through his awesome show, Fantasy Fiction, when we discussed science fiction, ecology and why we write.

My guest today is Simon Rose, an author of science fiction and fantasy novels for children and young adults, with a recent novel,

Future Imperfect

that will thrill your socks off. I met Simon some time ago through his awesome show, Fantasy Fiction, when we discussed science fiction, ecology and why we write. I recently had a chance to invite Simon aboard my intelligent ship, Benny, orbiting the Earth. An SF veteran, he didn’t blink an eye when I suggested the crystal-beam transporting device to get us aboard (it makes even me a bit squeamish). After settling in the aft lounge with some pockta juice, and a gorgeous view of Earth, we began the interview:

SFgirl : Tell us about your latest novel.

Simon: Future Imperfect is an exciting technology-driven adventure featuring teenage geniuses, corporate espionage, and mysterious messages. In the novel, we’re introduced to Andrew Mitchell, who was one of the leading experts in highly advanced technology in Silicon Valley, until he vanished following a car accident, which also injured his son, Alex. When a mysterious app later appears on Alex’s phone, he and his friend Stephanie embark on a terrifying journey involving secret technology, corporate espionage, kidnapping, and murder in a desperate bid to save the future from the sinister Veronica Castlewood.

The story will appeal to all young readers for whom technology plays such a large role in their lives, whether it’s cell phones, laptops, tablets, gaming, or the online world, but it’s also a very compelling adventure story, with lots of cliffhangers, twists, and turns.

SFgirl : I think it’ll be more than young readers enjoying it, Simon. Where can people buy Future Imperfect?

Simon: Future Imperfect is available at local bookstores, online at Amazon Canada, Amazon USA, Indigo/Chapters, Barnes and Noble, Amazon UK, and other locations, and autographed copies can also be purchased directly from me via my website.

SFgirl : You called me prolific once, but after seeing your collection, I think you’re the prolificest … Is that a word? Anyway, tell us about your other novels for young adults.

Simon:

Future Imperfect

is my tenth novel for young adults. The other novels include The Alchemist's Portrait, The Sorcerer's Letterbox, The Clone Conspiracy, The Emerald Curse, The Heretic's Tomb, The Doomsday Mask, The Time Camera, The Sphere of Septimus, and Flashback. I’ve also written more than 80 nonfiction books for children and young adults, but have also written books for adults. These include The Children's Writer's Guide, The Working Writer's Guide, The Social Media Writer's Guide, School and Library Visits for Authors and Illustrators, Exploring the Fantasy Realm, and Where Do Ideas Come From?

Simon:

Future Imperfect

is my tenth novel for young adults. The other novels include The Alchemist's Portrait, The Sorcerer's Letterbox, The Clone Conspiracy, The Emerald Curse, The Heretic's Tomb, The Doomsday Mask, The Time Camera, The Sphere of Septimus, and Flashback. I’ve also written more than 80 nonfiction books for children and young adults, but have also written books for adults. These include The Children's Writer's Guide, The Working Writer's Guide, The Social Media Writer's Guide, School and Library Visits for Authors and Illustrators, Exploring the Fantasy Realm, and Where Do Ideas Come From?SFgirl : What are you working on now?

Simon: My previous novel, Flashback, is a paranormal adventure involving psychic phenomena, ghosts, imaginary friends, mind control experiments, secrets, conspiracies, and time travel with a difference. Flashback has two sequels coming out in 2017, one in the spring and the third installment in the summer. These are already completed but there will be revisions and editing along the way later this year. I’m developing plans for some sequels to The Sphere of Septimus and Future imperfect may generate more adventures too. I’ve also recently completed a parallel universe trilogy, which I’m currently exploring publication options for.

SFgirl : What kind of marketing and promotion do you do?

Simon: I’m in all the usual places online and on social media but I’m also active in the local writing community and conduct book signings at local bookstores on a regular basis. In the spring I was at the Calgary Comic and Entertainment Expo and also connected with readers at schools and libraries in Montreal and Quebec City during Children's Book Week. In August I’ll also be appearing at When Words Collide in Calgary.

SFgirl: I’ll see you then; I’m going too! So, what do you do besides write?

Simon: I work as an instructor for adults at Mount Royal University and the University of Calgary. These classes and courses focus on writing for children and young adults or preparing your work for publication. I also offer coaching and editing services for writers in all genres and conduct online writing courses, such as Writing for Children and Young Adults and Writing Historical Fiction. I write screenplays, articles for magazines, and offer copywriting services for websites, blogs, social media, and businesses.

SFgirl : Simon, do you have any advice for new authors?

Simon RoseSimon: Writing is in some ways the easy part. It can be a very long process not only to write a book, but also to get it published. Most authors go through many revisions before their work reaches its final format. Remember too that your book will never be to everyone’s taste, so don’t be discouraged. A firm belief in your own success is often what’s necessary. After all, if you don’t believe in your book, how can you expect other people to?

Simon RoseSimon: Writing is in some ways the easy part. It can be a very long process not only to write a book, but also to get it published. Most authors go through many revisions before their work reaches its final format. Remember too that your book will never be to everyone’s taste, so don’t be discouraged. A firm belief in your own success is often what’s necessary. After all, if you don’t believe in your book, how can you expect other people to?Read as much as you can and write as often as you can. Keep an ideas file, even if it’s only a name, title, sentence or an entire outline for a novel. You never know when you might get another piece of the puzzle, perhaps years later. You also mustn’t forget the marketing. You may produce the greatest book ever written. However, no one else is going to see it if your book doesn’t become known to potential readers. Be visible as an author. Do as many readings, signings and personal appearances as you can. Get your name out there and hopefully the rest will follow. Especially for newly published authors, books don’t sell themselves and need a lot of help.

SFgirl : Excellent advice! Where can people learn more about you and your work?

You can visit my website at www.simon-rose.com or subscribe to my newsletter,which goes out once a month and has details of my current projects and upcoming events.

SFgirl : Thanks so much for joining me on Benny, Simon.

Simon: My pleasure, Nina.

SFgirl: You didn’t finish your pockta nectar…

Simon: It was … interesting … but I’m on a cleanse right now.

Well done, Simon! You can find Simon on the following Social Media links:

Facebook Twitter LinkedIn YouTube Google + Pinterest

July 4, 2016

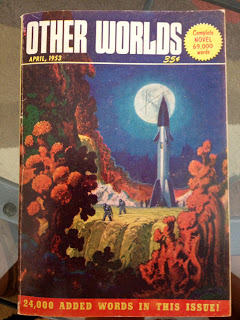

New Moon … and Other Worlds

After learning of my science fiction background, one of my writing coach clients very kindly gave me several 1950s issues of an SF pulp magazine Other Worlds Science Stories. I didn’t have the heart to tell her that the last thing I needed was more books—given that I’m more or less an itinerant and still trying to lighten my material possessions.

After learning of my science fiction background, one of my writing coach clients very kindly gave me several 1950s issues of an SF pulp magazine Other Worlds Science Stories. I didn’t have the heart to tell her that the last thing I needed was more books—given that I’m more or less an itinerant and still trying to lighten my material possessions.But I was intrigued.

Tattered and smelling of “attic”, the magazines lured with adventurous covers that summoned memories of why I started reading when I was little: streamlined rocket ships, aliens from exotic planets, explorers on adventures, and technological “utopias”.

1st issue of Astounding Stories 1930

1st issue of Astounding Stories 1930Defined by SF author Robert Silverberg as the epitome of the Science Fiction Golden Age, the 1940s heralded a panoply of short story magazines of the fantastic culminating in a true Golden Age for science fiction in the 1950s. According to Silverberg, the post-WWII 1950s saw “a spectacular outpouring of stories and novels.” Howard Browne started Fantastic in 1952. Horace Gold started Galaxy Science Fiction in 1949. Anthony Boucher founded The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fictionin 1949. Samuel Mines ran Thrilling Wonder in the 1950s. And John W. Campbell Jr. had started Astounding Science Fiction in 1930, in which A.E. van Vogt and Robert A. Heinlein were first published. Hugo Gernsback had started Amazing Stories in 1926, in which Isaac Asimov was first published in 1939. Amazing Stories still runs today as an online magazine.

Asimov's first story in 1939 issueThe Golden Age saw in some of the most enduring science fiction tropes. Works celebrated scientific achievement and a sense of wonder in our universe. Space opera (space adventure) and exploration of the universe emerged; Isaac Asimov established the Three Laws of Robotics; Heinlein expressed libertarian ideologies and we saw the re-emergence of spiritual themes from the “pulp era”. Books that I read when I was young—Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles; Clarke’s Childhood’s End; Wyndham’s Day of the Triffids; and Miller’s A Canticle for Leibowitz—came from this era.

Asimov's first story in 1939 issueThe Golden Age saw in some of the most enduring science fiction tropes. Works celebrated scientific achievement and a sense of wonder in our universe. Space opera (space adventure) and exploration of the universe emerged; Isaac Asimov established the Three Laws of Robotics; Heinlein expressed libertarian ideologies and we saw the re-emergence of spiritual themes from the “pulp era”. Books that I read when I was young—Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles; Clarke’s Childhood’s End; Wyndham’s Day of the Triffids; and Miller’s A Canticle for Leibowitz—came from this era. Clark Publishing in Evanston, Illinois, started to publish and sell Other Worlds Science Stories for 35 cents in the late 1940s. Raymond A. Palmer and Bea Mahaffey were editors.

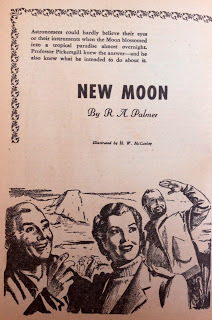

I picked up the digest-size April 1953 issue of Other Worlds with its iconic rocket ship in an alien world of lush alien vegetation and exploring astronauts and large “moon” shining in the background; only in this case the lush world was our moon and the “moon” in the sky was Earth. A changed Earth. The cover art by Robert Gibson Jones portrayed a scene from the first story in the magazine called “New Moon” by Raymond A. Palmer (the editor of the magazine) and illustrated by H.W. McCauley. A story I found interesting for several reasons.

Palmer introduces “New Moon” as a story taking place in 1967—14 years after he wrote it and two years prior to the first moon landing by the Apollo 11 crew. He proposed a two-fold premise: 1) that we can measure and reasonably predict dry and wet periods by using varves (layers in lake sediment); and 2) that rocket scientists will send a rocket to the moon in reasonable time. In fact, his story of a first moon landing was out by only two years. Palmer also set his story during a major draught in America in the mid-sixties—a time when the Northeastern United States would be hit with devastating drought that would last several years.

Palmer introduces “New Moon” as a story taking place in 1967—14 years after he wrote it and two years prior to the first moon landing by the Apollo 11 crew. He proposed a two-fold premise: 1) that we can measure and reasonably predict dry and wet periods by using varves (layers in lake sediment); and 2) that rocket scientists will send a rocket to the moon in reasonable time. In fact, his story of a first moon landing was out by only two years. Palmer also set his story during a major draught in America in the mid-sixties—a time when the Northeastern United States would be hit with devastating drought that would last several years.The horizon was near, a rolling pail of brownish black, cutting down visibility to a matter of less than a quarter of a mile In the yard a thorny rosebush whipped in the wind, a few dried leaves still clinging to it. Above it the gaunt limbs of the great elm that had shaded the house etched photographically potent arms against the tragic sky. The ditch between the yard and the road was filled with curiously wind-rippled powdery dust…

When the moon suddenly and literally turns green—blossoming into a verdant paradise—scientists get excited. Enter Professor Pickersgill, physicist and astronomer, who explains that this resulted from “a vast cloud of atmospheric and water vapors that had drifted in from outer space, and had now engulfed the moon. Or rather, the moon had gulped most of it in to itself.” Pickersgill then explains to one of the crew who marveled at the speed of vegetative growth, that the spores of life may exist in all space and if so, “they’ve been falling for uncounted ages on the moon, accumulating in soil of incredible fertility. Maybe all that was needed was the water and atmosphere. And among all these strange vegetable forms, there must be hundreds unknown on Earth, and many of them may be much swifter in growth than those adapted to Earth conditions.”

Scientists now know that water exists everywhere in the universe, from our own sun and planets to comets, dust clouds and even whirlpool-like spinning black holes.

In June 2011, researchers at ESA’s Herschel Space observatory identified a protostar or quasar, 750 light years away. The young star was blasting jets of water into interstellar space from its poles at 124,000 miles per hour. The telescope was able to trace where hydrogen and oxygen, two of the most popular elements in the universe, formed water on and around the star. Close to the star, its heat and pressure vaporize the water into jets of gas. But farther away the water cools into droplets that move like bullets at “80 times faster than the average round fired from a rifle,” writes Clay Dillow in Popular Science Magazine. The speedy spray is “equal to the amount that flows through the Amazon every second,” researchers said. This suggests two things: (1) that young protostars may be distributing vast quantities of water, potentially seeding life elsewhere in the universe; and (2) that water may have played a significant role in the formation of our own sun and solar system. “Stars are the alchemists of the Universe,” Philip Ball writes in H2O: A Biography of Water. Engines of creation, “out of their hearts come the elements needed to make worlds.”—Nina Munteanu, Water Is…The Meaning of WaterScientists have shown that water plays a key role in the formation of organic molecules and together with the vortex-like radiation of a neutron star may influence the creation of life-forming amino acids. This is not surprising, considering water’s ubiquitous nature and weird properties.

Because water is denser as a liquid than as a solid, ice floats; this permits fish and other aquatic biota to live under partially frozen rivers and lakes. Water—unlike most other liquids—also needs a lot of heat to warm up even a little, which allows mammals to regulate their body temperature. Life’s cellular processes rely on water’s ability to act as a universal solvent. The high diffusion rate of water helps transport critical substances in multicellular organ- isms and allows unicellular life to exist without a circulatory system. one important result is that the viscosity of blood, which behaves in a non-Newtonian way (its viscosity decreases with pressure), will drop when the heart beats faster.—Nina Munteanu, Water Is…The Meaning of Water

July 3, 2016

The Way of Water (La natura dell’acqua)

She imagines its coolness gliding down her throat. Wet with a lingering aftertaste of fish and mud. She imagines its deep voice resonating through her in primal notes; echoes from when the dinosaurs quenched their throats in the Triassic swamps.

Water is a shape shifter.

It changes yet stays the same, shifting its face with the climate. It wanders the earth like a gypsy, stealing from where it is needed and giving whimsically where it isn’t wanted.Dizzy and shivering in the blistering heat, Hilda shuffles forward with the snaking line of people in the dusty square in front of University College where her mother used to teach. The sun beats down, crawling on her skin like an insect. She's been standing for an hour in the queue for the public water tap.

“La immagina scenderle fresca giù per la gola, con un persistente retrogusto umido di pesce e fango. La immagina risuonarle dentro con voce cupa, una voce primordiale; gli echi del tempo in cui i dinosauri placavano la sete nelle paludi del Triassico.L’acqua è un mutaforma.Cambia pur restando la stessa, muta il proprio volto insieme al clima. Vaga per il pianeta come una nomade, rubando da dove è necessaria e dandosi per capriccio dove non serve.Frastornata e tremante nel caldo afoso, Hilda si trascina a fatica dietro al serpente di persone sul piazzale polveroso di fronte al college universitario in cui insegnava sua madre. Il sole picchia e le striscia sulla pelle come un insetto. È in fila da un’ora davanti al distributore pubblico di acqua."

“The Way of Water” is a near-future vision that explores the nuances of corporate and government corruption and deceit together with resource warfare. An ecologist and technologist, Nina Munteanuuses both fiction and non-fiction to examine our humanity in the face of climate change and our changing relationship with technology and Nature.“The Way of Water” (“La natura dell’acqua”) was recently favorably reviewed by Simone Casevecchia of SoloLibri.net . The bilingual print book by Mincione Edizioni showcases the short story in Italian and English and provides an account of what inspired it: “The Story of Water” (“La storia dell’acqua”).

After the release of the print book, Future Fiction released “The Way of Water” (“La natura dell’acqua”) in ebook format. The ebook contains the “Way of Water” story and another story, “Virtually Yours” (“Virtualmente tua”) alongside “The Story of Water” (non-fiction), which can be purchased in either Italian or Engish versions.“Virtually Yours” was first published in Issue #4 of Neo-Opsis Science Fiction Magazine (Canada); it was reprinted in several languages in other countries including USA, Poland, Romania, Greece, and now Italy. It also appears as one of nine stories on human evolution in

Natural Selection

, a Canadian collection of short stories that examine the evolution of humanity with Nature and technology. Nina’s short stories have received praise for their world building, depth of character, compelling plot and use of evocative metaphor:

After the release of the print book, Future Fiction released “The Way of Water” (“La natura dell’acqua”) in ebook format. The ebook contains the “Way of Water” story and another story, “Virtually Yours” (“Virtualmente tua”) alongside “The Story of Water” (non-fiction), which can be purchased in either Italian or Engish versions.“Virtually Yours” was first published in Issue #4 of Neo-Opsis Science Fiction Magazine (Canada); it was reprinted in several languages in other countries including USA, Poland, Romania, Greece, and now Italy. It also appears as one of nine stories on human evolution in

Natural Selection

, a Canadian collection of short stories that examine the evolution of humanity with Nature and technology. Nina’s short stories have received praise for their world building, depth of character, compelling plot and use of evocative metaphor: ".a stunning example of good storytelling with an excellent setting and cast of characters."--Tangent Online

“…Written with flare and a conscience…Munteanu shines a light on human evolution and how the choices we do or don’t make today, may impact our planet and future generations. The science is fascinating and so are these nine short stories.”—J.P. McLean, author of The Gift Legacy

“…Fascinating dramas set in a world too close to our own…the science was so interesting, combining visionary metaphysical speculation with AI corporate tech in scenarios that often seemed chillingly possible.”—Amazon review

“…Jealousy, lust, loneliness, grief and love are all drivers of these taut and fascinating narratives.”—Amazon review

“…a fantastic collection of stories by a deeply-involved writer, based in Canada.”—Amazon review

“…a well written, thought provoking collection of stories that will leave you hoping the future that Nina Munteanu projects never happens…Nina Munteanu is a gifted writer. Each story surprises and delights.”—Allan Stanleigh, author of USNA

“…Actually brought to mind Niven’s Tales of Known Space…Nina’s stories tease you.”—D. Merchant, Louisianna Tech University College

The Way of Water can be purchased as:

Ebook (Italian OR English) with additional short story “Virtually Yours” through Future Fiction (Mincione Edizioni) for €1,99 at:

Ebook (Italian OR English) with additional short story “Virtually Yours” through Future Fiction (Mincione Edizioni) for €1,99 at: · Italian or English, Pubisher · Italian version, Amazon.it (kindle) · Italian version, Amazon.com · Italian version, iBooks · English version, Amazon.com (kindle) Print book (Italian AND English) through Mincione Edizioni for €7,00 at:

· IBS · Unilibro · LaFeltrinelli · Amazon France · Ciao

Translated into Italian by Fiorella Moscatello. Print book cover by Laura Cionci. Ebook cover by Brad Sharp.

June 17, 2016

Launch of "Water Is..." Celebrates Our Connection With Water

Abbas Jivaji offers smudging in water blessingOn June 12th, Councillor Jim Tovey, Mississauga Nation knowledge keeper Nancy Rowe and others helped me celebrate the launch of my long-awaited book

"Water Is..."

(three years in the making!) with a water blessing of Mimico Creek and various water-engaging activities.

Abbas Jivaji offers smudging in water blessingOn June 12th, Councillor Jim Tovey, Mississauga Nation knowledge keeper Nancy Rowe and others helped me celebrate the launch of my long-awaited book

"Water Is..."

(three years in the making!) with a water blessing of Mimico Creek and various water-engaging activities.The environmental event “celebrated water and our connection with it” at Islington Golf Course in Etobicoke. The 75 people who attended also included the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority, Credit Valley Conservation Authority, Lake Ontario Waterkeeper, Ecologos (WaterDocs), Rethink Sustainability Initiatives, poets, writers and artists.

Nancy Rowe

Nancy RoweIn her powerful and compelling blessing, Nancy Rowe said, “Water is life, water is healing, we owe everything to water.” Despite the celebration, Mimico’s ironic reality was reflected in the ceremony: “You used to be able to drink this water,” Rowe lamented as she used tap water for the water blessing ceremony.

Vince D’Elia of TRCA gave Mimico Creek a failed report card and spoke about the need to educate the public on water and watersheds. Given that Mimico Creek flows some 33 km within a 77 square km watershed that encompasses three jurisdictions (Brampton, Mississauga, and Toronto); harmonizing efforts is no easy task.

Jim Tovey offers water wisdom at Nina's book launchCouncillor Tovey stressed connection of individuals, communities and jurisdictions to create awareness and action in re-wilding our watersheds and to foster beauty. He highlighted Mississauga's extensive planning and investment into these initiatives, saying that they are setting the precedent for all Canadian cities for sustainability planning.

Jim Tovey offers water wisdom at Nina's book launchCouncillor Tovey stressed connection of individuals, communities and jurisdictions to create awareness and action in re-wilding our watersheds and to foster beauty. He highlighted Mississauga's extensive planning and investment into these initiatives, saying that they are setting the precedent for all Canadian cities for sustainability planning. Claire Lawson of LOWaterkeeper proclaimed that, “We are Lake Ontario,” referring to us being 70% water and the constant circulation of water on the planet. She gave us the 5 steps to water leadership, and told us why sharing our personal watermarks was so important. She urged participants to share their watermark--a personal story that connected them with a particular waterbody and event--to help promote meaning and protection of waterbodies around the world.

Mimico Creek (photo N. Munteanu)Ro Omrow, with Ecologos (WaterDocs) invited participants to sign a petition to make Toronto a Blue Community. Initiated by the Council of Canadians, a Blue Community is one that:recognizes water as a human rightbans the sale of bottled water in public facilities and at municipal eventspromotes publicly financed, owned and operated water and wastewater servicesColleague, Naturalist friend, editor, indexer and poet, Merridy Cox, shared her watermark. Liana Di Marco read her poem "Rewilding the Sacred", which appears in my book. John Ambury, whose poem also appears in my book read "Moving Waters."

Mimico Creek (photo N. Munteanu)Ro Omrow, with Ecologos (WaterDocs) invited participants to sign a petition to make Toronto a Blue Community. Initiated by the Council of Canadians, a Blue Community is one that:recognizes water as a human rightbans the sale of bottled water in public facilities and at municipal eventspromotes publicly financed, owned and operated water and wastewater servicesColleague, Naturalist friend, editor, indexer and poet, Merridy Cox, shared her watermark. Liana Di Marco read her poem "Rewilding the Sacred", which appears in my book. John Ambury, whose poem also appears in my book read "Moving Waters."

The Sea by Tasnim Jivaji (photo by Nina Munteanu)

The Sea by Tasnim Jivaji (photo by Nina Munteanu)Mississauga artist Tasnim Jivaji exhibited her water-inspired art. Originally from Nairoby, Kenya, Jivaji said, "In all my travels, in all the places around the world, it has never been the concrete that takes my breath away; it is always the body of water."

The event also included a Water Action Station, which featured a three-step process toward successful water-action:

Step 1: buy my book (learning--step one toward water literacy, of course!)Step 2: pin your prioritized water charity (Pixl Press is donating a portion of book sales toward several water charities; engagement)Step 3: sign a pledge to Cousteau's Bill of Rights for Future Generations (commitment to action)

Sunset sky by Tasnim Jivaji (photo by N. Munteanu)The mission of the Cousteau society and this bill is to "educate people to understand, to love and to protect the water systems of the planet, marine and fresh water, for the well-being of future generations."

Sunset sky by Tasnim Jivaji (photo by N. Munteanu)The mission of the Cousteau society and this bill is to "educate people to understand, to love and to protect the water systems of the planet, marine and fresh water, for the well-being of future generations."According to Tovey, my book “Water Is…” bridges the gap from awareness to appreciation, connection and final action.

Praise for "Water Is..." from around the world:

“This book emotionally connected me with water. As a result it fed my perception about the value of life. It reminded me that life reveals in each space a complex system that is full of surprise and beauty. A system of which I am part, without separation.”—Laura Fres, One Deep Sustainability, Barcelona, Spain “A sumptuous collection of treasures…from the basics of matter itself to the social and spiritual aspects of this substance, which touches our lives so much and is still not really understood.”—Dr. B. Kröplin and Regine C. Henschel, “World in a Drop”, Germany “Congratulations, Nina! Water Is… is an adventurous, surprising and inspiring book that could not feel more timely. The writing swept me away on a journey through history, landscape and our entire universe, yet brought me back home in the end with a fresh perspective on the significance of water.”—Emmi Itäranta, author of Memory of Water, United Kingdom

“If you don’t want to read all those other books on water, just read this one.”—John Stewart, Mississauga News, Ontario, Canada

“[Nina] is immersed well enough in water to tell us about how we should think about it. And the way she goes about it in this book is awfully good…A fine achievement.”—Joseph Planta, The Commentary, Vancouver, Canada

“This book leaves me impressed. From science to science fiction, from philosophy to religion, from history to fairytale, the role of water is illustrated and illuminated. Water is probably the best investigated and least understood substance on this world, yet we still don’t know how to describe it in a better way than calling it H2O. This book tries to zero in on the missing part, the great unknown of water, and it does it in a very intelligent and charming way.”—Elmar C. Fuchs, scientist, WETSUS Program Manager, Netherlands “Kudus to Nina Munteanu for sharing her deep wisdom, experience and knowledge of humanity’s greatest natural resource! As Leonardo da Vinci said, “We forget that the water cycle and the life cycle are one.” We forget at our own peril and so I am deeply grateful for this book by so highly qualified an author!”—Elisabet Sahtouris, evolution biologist, futurist, author of Gaia’s Dance: The story of Earth & Us, USA

This book came from a lifetime's dedication to water, humanity and our environment--from the moment I realized as a little girl that I felt the planet. I firmly think that water is the "glue" that can help us all connect and this book is the result.

This book came from a lifetime's dedication to water, humanity and our environment--from the moment I realized as a little girl that I felt the planet. I firmly think that water is the "glue" that can help us all connect and this book is the result. Water is the ultimate gift and connecting force.

In the months and years to come we may see water further commodified, abused, and persecuted, figuring in tensions, take-overs and wars ... Or not ... That depends on us, everyone of us. We're over 70% water, after all.

We ARE water...

What we think, feel and do, so does water.

#WhatIsWATER#TheMeaningOfWater

Images taken by Kevin September (@SeptemberSphere; http://kevinseptember.com) unless otherwise shown.

May 18, 2016

Drinking Smoke and Peat with Mac & Cheese

scotch on the Faculty Club patioIt’s been a while since I drank scotch.

scotch on the Faculty Club patioIt’s been a while since I drank scotch.The last time was more than several years ago in a dark bar at the foot of Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania.

I had just come down the mountain, having barely reached the upper foothills. My friend Margaret and I had abandoned the taxing ascent in favor of a more pleasant and relaxing hike and more time at the local bar. The place was somewhat run down and smelled of burnt plantain and rotting fruit. All they had was scotch. The whisky burned down my throat like a wild fire; its pungent rawness mocked the disappointment that lurked beneath my relief in the abandoned climb. As I nursed my drink over some fried goat’s meat, I decided that I didn’t like scotch. And that was that. Scotch—like the peak of Kilimanjaro—remained elusive.

Many years later, I found myself travelling in Kentucky and sampling its signature drink—Kentucky small batch bourbon whisky. Bourbon is a barrel-aged American whiskey made mainly of corn. Like Champagne, Bourbon is named for the area it was first conceived, known as Old Bourbon (now Bourbon County in Kentucky)

Getting the Lagavulin, Faculty Club Puband after the French House of Bourbon royal family. The typical bourbon grain mixture, called mash bill, is 70% corn mixed with wheat and/or rye and malted barley. Yeast is added to a sour mash of ground grain and then fermented. This “wash” is then distilled into a clear spirit, which is aged in charred white oak barrels. Bourbon gains color and flavor from the wood as it ages. When I finally graduated to drinking bourbon neat, I learned to look for a premium class sipping whiskey that is a Kentucky Straight (aged at least two years and made entirely in Kentucky) and a single-barreled bourbon (e.g., the bottle comes from an individual aging barrel; not a blend from various different barrels to provide uniformity of color and taste). A good sipping bourbon boasts a very deep and satisfying nose, with a start of caramel and vanilla and a “soft pepper” aftertaste.

Getting the Lagavulin, Faculty Club Puband after the French House of Bourbon royal family. The typical bourbon grain mixture, called mash bill, is 70% corn mixed with wheat and/or rye and malted barley. Yeast is added to a sour mash of ground grain and then fermented. This “wash” is then distilled into a clear spirit, which is aged in charred white oak barrels. Bourbon gains color and flavor from the wood as it ages. When I finally graduated to drinking bourbon neat, I learned to look for a premium class sipping whiskey that is a Kentucky Straight (aged at least two years and made entirely in Kentucky) and a single-barreled bourbon (e.g., the bottle comes from an individual aging barrel; not a blend from various different barrels to provide uniformity of color and taste). A good sipping bourbon boasts a very deep and satisfying nose, with a start of caramel and vanilla and a “soft pepper” aftertaste.Fast forward to a few days ago, as I lounged in the outside patio of the University of Toronto

UofT Faculty Club patioFaculty Club, recently opened for the season. It was early May and a warm breeze brought with it the promise of adventure. The patio provided a cheerful setting as I prepared to celebrate a double birthday—mine and a friend’s—as well as my soon to be released book

Water Is…

I decided to order a bourbon as I waited for my friend to arrive. Alas! They didn’t have any! What was a girl to do for her birthday and first of many launch celebrations?

UofT Faculty Club patioFaculty Club, recently opened for the season. It was early May and a warm breeze brought with it the promise of adventure. The patio provided a cheerful setting as I prepared to celebrate a double birthday—mine and a friend’s—as well as my soon to be released book

Water Is…

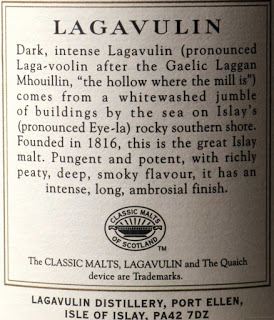

I decided to order a bourbon as I waited for my friend to arrive. Alas! They didn’t have any! What was a girl to do for her birthday and first of many launch celebrations?“The 16-year old Lagavulin is a lovely scotch,” offered one of the kind patrons as reprieve to my forlorn disappointment. I forgave him for not knowing my legacy with scotch. “Lagavulin is a fine Islay single malt scotch; great for a celebration,” he insisted. Malt scotch whisky is made by the pot still process using malted barley only. And the name Lagavulin, I later found, means “hollow by the mill” (Laggan Mhouillin) in Gaelic.

I demurred at first.

Faculty Club pubThen, with thoughts of an elusive mountain unclimbed, I agreed and watched Leanne, the manager of the Faculty Club, pour me a dram of intense amber liquid. She left the bottle for me to study and I read the strange description on the front label:

Faculty Club pubThen, with thoughts of an elusive mountain unclimbed, I agreed and watched Leanne, the manager of the Faculty Club, pour me a dram of intense amber liquid. She left the bottle for me to study and I read the strange description on the front label: “Moss water, passing over rocky falls, steeped in mountain air and moorland peat, distilled and matured in oak casks exposed to the sea shape Lagavulin’s robust and smoky character. Time, say the Islanders TAKES OUT THE FIRE but LEAVES IN THE WARMTH.”

I inhaled the sharp organic scent of peat

rare fritillary butterfly on Islaybog with something else not identifiable. Intrigued, I took a sip. The deep musk burned down my throat with a complex fire, warming every cell of my body with stories of ancient peatlands by the sea and rolling acidophillous grassland and marsh—home of the elusive and endangered marsh fritillary butterfly. The complexity of loam, smoke and sweet meadow grass gave way to a long and intense finish of burning sweet caramel: what I imagined a crème brulee would be if it decided to be a liquor. Do the villagers of Islay enjoy crème brulee as much as I do?

rare fritillary butterfly on Islaybog with something else not identifiable. Intrigued, I took a sip. The deep musk burned down my throat with a complex fire, warming every cell of my body with stories of ancient peatlands by the sea and rolling acidophillous grassland and marsh—home of the elusive and endangered marsh fritillary butterfly. The complexity of loam, smoke and sweet meadow grass gave way to a long and intense finish of burning sweet caramel: what I imagined a crème brulee would be if it decided to be a liquor. Do the villagers of Islay enjoy crème brulee as much as I do? When my friend arrived, we toasted each other’s birthdays and ordered something to go with the scotch. Merridy ordered the warm mushroom salad and I went with the club’s signature macaroni and cheese, baked with spinach and mushrooms. Exquisitely baked and briefly braised on top, the mac and cheese was a divine mate to the 16-year old scotch. A libiamo ne’lieti calici of sharp and salty seashore tempered with the bursting melt of cheese and pasta. A comingling in a lively Verdi duet. I sipped my scotch and dug through the crispy crust of baked cheese pulling out gooey strings of cheddar, parmesan, mushrooms and spinach.

When my friend arrived, we toasted each other’s birthdays and ordered something to go with the scotch. Merridy ordered the warm mushroom salad and I went with the club’s signature macaroni and cheese, baked with spinach and mushrooms. Exquisitely baked and briefly braised on top, the mac and cheese was a divine mate to the 16-year old scotch. A libiamo ne’lieti calici of sharp and salty seashore tempered with the bursting melt of cheese and pasta. A comingling in a lively Verdi duet. I sipped my scotch and dug through the crispy crust of baked cheese pulling out gooey strings of cheddar, parmesan, mushrooms and spinach.Mac and cheese originated in southern Italy in the 12oos. Liber de coquina, written by

Leanne inhales the "nose" of Lagavulinsomeone familiar with the Neapolitan court then under Charles II of Anjou (1248-1309) contains a recipe called de lasanis, purported to be the first “macaroni and cheese” recipe.

Leanne inhales the "nose" of Lagavulinsomeone familiar with the Neapolitan court then under Charles II of Anjou (1248-1309) contains a recipe called de lasanis, purported to be the first “macaroni and cheese” recipe.Six hundred years later, John Jonston and Archibald Campbell built the Lagavulin distillery—a whitewashed jumble of buildings by the sea—in the village of Lagavulin on the rocky southern shore of the island of Islay, the southernmost of the Inner Hebridean Islands off the west coast of Scotland. Amy Zavatto of Serious Eats describes Islay as a “wild and windswept corner of the world where sheep may well outnumber people and waterproof shoes are your good friend.” Peat, she reminds us, is decomposed organic matter—grass, heather, moss—that forms along the coastal, boggy lands that make up much of Islay. Peat holds moisture and smokes wonderfully when you burn it. And when this is used to truncate the germinating of the little barley bits via heat it flavors the malted barley with a unique perfume. This is called peating whisky. Most of Scotland’s distillers no longer peat their whiskies (preferring oil burners); but Islay still harvest and burn peat to make their whisky.

Still pots at Lagavulin

Still pots at LagavulinThe Master of Malt writes that Lagavulin is “a much sought-after single malt with the massive peat-smoke that's typical of southern Islay—but also offering richness and a dryness that turns it into a truly interesting dram. The 16 year old has become a benchmark Islay dram from the Lagavulin distillery.” This 16-year spirit has won many awards, including the Whisky of the Year in 2013. Lagavulin is known for its use of slow distillation speed and its pear-shaped pot stills.

The waters of Solum Lochs, along with the peating levels of the barley, help give this scotch its distinctive flavor. In an interview with Eric Knudsen, master distiller Donald Renwick of Lagavulin affirmed that, “The water from the Solum Lochs is obviously important, as it is our own water, good quality with lots of peat in it. However one of the most important parts is the Malted barley (malted at our own Maltings plant on Islay) During the kilning process a peat fire introduces the peat smoke into the malted barley. This gives Lagavulin its distinctive peaty and smoky flavours.”

T

Lagavulin on Islayhe Whisky Exchange writes that, “Lagavulin is not for the faint-hearted but inspires fanatical devotion in its many followers.” Says Zavatto: “Give it a couple of gentle sniffs (e.g., don't go sticking your nose all the way in the glass; there's a lot of alcohol there, so take it in easy!) to take in that first burst of sea spray and smoke, and then try to see what else you find underneath that. I'd recommend that you consider adding a drop or two of water, which you'll find really teases out some of the underlying orchard fruit, citrusy, or caramel-vanilla notes that are lurking beneath the peaty surface. This is, after all, uisge beatha—the water of life. It's worth a wee moment or two to enjoy it.”

Lagavulin on Islayhe Whisky Exchange writes that, “Lagavulin is not for the faint-hearted but inspires fanatical devotion in its many followers.” Says Zavatto: “Give it a couple of gentle sniffs (e.g., don't go sticking your nose all the way in the glass; there's a lot of alcohol there, so take it in easy!) to take in that first burst of sea spray and smoke, and then try to see what else you find underneath that. I'd recommend that you consider adding a drop or two of water, which you'll find really teases out some of the underlying orchard fruit, citrusy, or caramel-vanilla notes that are lurking beneath the peaty surface. This is, after all, uisge beatha—the water of life. It's worth a wee moment or two to enjoy it.”The whiskies of the nine or so distilleries along the southeastern coast of Islay typically

express that smoky character and what some—me included—would describe as a “medicinal” quality. Notes of iodine, seaweed and salt have been used to describe the element that I found deliciously unidentifiable.

express that smoky character and what some—me included—would describe as a “medicinal” quality. Notes of iodine, seaweed and salt have been used to describe the element that I found deliciously unidentifiable.It made perfect sense, I finally decided, reminded of what D.H. Lawrence said about water: “Water is H2O, hydrogen two parts, oxygen one; but there is also a third thing that makes it water. And nobody knows what it is.”

So with water; so with scotch. Uisge beatha.

The University of Toronto Faculty Club is located on 41 Willcocks Street, Toronto, Ontario; 416-971-2062.

My book,

“Water Is…”

was released worldwide on May 10, 2016.

My book,

“Water Is…”

was released worldwide on May 10, 2016. Water Is…

Pixl Press

ISBN: 978-0-9811012-4-8