Patricia Roberts-Miller's Blog, page 41

August 11, 2017

Aristotle’s types of rhetoric

Aristotle identified three kinds of rhetoric (with, he admitted some overlap). Any kind of decision-making body (a group that is setting policies) should engage in deliberative rhetoric, or what is sometimes called policy argumentation. As Aristotle said, in deliberative rhetorical situations, people argue about the pragmatics of the situation—people try to get the best outcomes, and they make issues like honor secondary (or don’t consider them at all). Scholarship in rhetoric would go on to identify the really crucial ways that communities can engage in healthy arguments about policy, and it isn’t rocket science.

Let’s imagine that we’re deliberating about the problem of the litterboxes needing cleaning (I have three cats—they always need cleaning). A good argument about a policy has certain content rules:

you have to debate (and that means disagreement is crucial and helpful) about whether there really is a problem (the litterboxes are nasty);

whether it will go away on its own (inherency: they will not clean themselves);

whether it’s significant (yes, they’re nasty);

what policy options we have, and this is important, since faux deliberative rhetoric says there is Our Policy or doing nothing at all, when we always have a lot of policy options (we could hire someone to clean them, we could invade another country, we could rant at the cats about how much they poop, we could hope that quantum physics puts the poop in some other part of the universe, we could invest in self-cleaning litterboxes, we could let the cats out, we could make the catio more attractive for pooping, we could declare the problem of the litterboxes is part of the squirrel conspiracy and so the answer is to eradicate our property of squirrels, we could clean the litterboxes more often, we could have fewer cats, we could see whether people on the neighborhood mailing list who clearly have way too much time on their hands could be persuaded to use some of that time cleaning our litterboxes);

and then we assess those policy options in terms of feasibility (what it would cost to hire someone to clean the litterboxes), solvency (would invading another country actually clean our litterboxes), and unintended consequences (people who have way too much time on their hands and engage in long and useless threads about graffiti on the neighborhood mailing list would probably insist on ranting at us in person about how pretty meh graffiti on a wall means our thoroughly upper middle class neighborhood is just one mark from being the kind of sodomic drug scene you see in video games and that would mean hours of loss in productivity and maybe an assault charge against me).

Deliberative rhetoric is hard. It requires thinking you might be wrong, and it privileges long-term thinking. It requires that the people involved in the deliberation believe that all the groups in the discussion have shared goals, so it means a world in which some kind of value is more important than the short-term triumph of the ingroup, and it requires a world in which fairness is dominant as a value.

In judicial rhetoric the whole issue is determining what happened in the past, and who is guilty. Judicial rhetoric relies on binaries—someone is guilty or not, this person is the victim and that person is the villain. And it isn’t about causality; it’s about blame. Judicial rhetoric is always about people who do or don’t intend to do wrong. Deliberative rhetoric always has arguments about causality (this person or this movement or this action caused that thing) but it isn’t about intent—healthy deliberative rhetoric acknowledges that people will good intentions can make decisions with disastrous consequences.

Judicial rhetoric, however, needs to find a person to punish. It doesn’t matter whether punishing that person (or group) will lead to a good outcome. All that matters is attributing blame and then punishing. Deliberative rhetoric and judicial rhetoric get confused for a lot of people who spend their whole lives in judicial rhetoric, since they hear all causality arguments as blame arguments—if a butterfly here causes a hurricane to happen there, then the butterfly is to blame. That’s judicial rhetoric. Deliberative rhetoric doesn’t blame the butterfly, but tries to figure out whether we could find processes that would keep a butterfly from being able to do so much damage.

Aristotle’s third category is epideictic, or ceremonial rhetoric. Aristotle says that kind of rhetoric is all about honor and dishonor. The classic (even classical) examples of epideictic rhetoric are a funeral oration or Fourth of July speech. A good funeral oration always presents the dead person as entirely honorable, an argument that not uncommonly involves skipping over some things (I once heard a Catholic priest say about a woman who had refused to attend mass for some twenty years, “She has a good Irish name, and so we know God welcomed her.”) More recent scholars of rhetoric have argued (correctly, I think) that ceremonial rhetoric creates an “us” (often, but not necessarily, against a “them”). Epideictic rhetoric says there is “we” and invites you to be a part of that “we.” It makes you feel good about that “we” and it generally (but not always) makes you feel angry about the “not-we.” A Fourth of July speech doesn’t invite you to consider complicated things about what “we” means for the US (unless you’re Frederick Douglass); it invites you to feel part of the “American” community and take pride in that.

August 3, 2017

Why we named a dog Marquis de la Fayette in 2004

When Chester Burnette died, and Hubert Sumlin almost died from grief, George Washington arrived on the scene and saved the day. George was the sort of pushy goofball that everyone loves–he had his faults. To his dying day (literally) we could not persuade him to leave strangers’ crotches alone, and his mission in life was to get to any kleenex in any available trash can (which, let’s be blunt, means I was an idiot to keep throwing kleenex in the trash). Someone told us his breed was “Austin Red Dog,” meaning he was one of the many combinations that ends up in a dog between 70 and 100 lbs., red-orange coat, sort of stand-up sort of hang down ears. (In George’s case, he had one of each.)

When we’d had George for about a month, we got a call from our vet’s office. If you’re doing the math, this means we got the call at the end of January when everyone in Austin is dying from cedar fever. This fever is particularly bad if you live in a place called Cedar Park–people are walking into walls either because of allergies or because of allergy medicine. Personally, I was on both. They explained that the local animal shelter (which, as I understand, has since been closed) had a limited number of cages for dogs; when they got additional admissions, they just euthanized whatever dogs were at the end. These end-cage animals were euthanized at our vet’s office, and so the vet’s office was calling the customers (aka “softies”) who might be able to foster some of the puppies who were in that last cage.

There was one, they said, that looked just like George. “Sure,” I said. [As an aside, you might note I did not ask my husband first. He has never upbraided me for this, although he could have.] The 12-week old puppy we got was an only slightly mini-me version of George. Even we often had trouble telling them apart. Feeling guilty about having landed my family with a foster dog without asking, I was determined I would find this dog a home. Instantly, we started obedience lessons, at which he was outrageously good, and I started asking everyone I knew if they wanted an adorable and smart dog. In the interim, he had completely bonded with George. He did everything George did, literally looking up to him. There came the question of what to call him. “Ha ha,” I said, “he follows George Washington around and looks up to him–we should call him Marquis de Lafayette.” I had forgotten that my son was in the midst of a revolutionary war geekocity (thanks, “Liberty’s Kids”), having just named our new dog George Washington. And my husband has considerable history geek cred. They loved the idea. “No!,” I said, “we’re in Texas–we need to name him Cowboy or Buddy or we’ll never find him a home!” I was outvoted.

I found him a prospective home–which wasn’t hard–after two weeks. He was, after all, smart and highly photogenic and the perfect size (headed for around 70 lbs.). The prospective parents were going to come over one Saturday, and the night before I told Jacob (six years old). Jacob didn’t throw a fit (which I might have been able to resist); instead, his lower lip trembled, as he tried desperately to be brave. I said, “Now, Jacob, we talked about this. We knew that he wasn’t going to stay with us.” He said, “Yes, I know, but good-byes are so hard.”

I fell back on the parental [blarghy blargh ohnowhatdoisaynow] filler, and said, “What do you mean by that?”

He said, “Well, we had to say good-bye to Chester, and then to Coolhand Luke [a very old cat who died during that January], and now to Marquis.”

I said, “Um, I need to talk to your dad for a minute.” And I went into the study, where Jim was playing a computer game. I said, “I think we’re keeping Marquis.” He said, “I know.” He didn’t even turn around or hit pause.

August 1, 2017

III. Immediate rhetorical background

In the 1932 election, nobody received enough votes for anything other than a coalition government. The far left refused to compromise with the moderate left, and Hindenburg and Papen were persuaded to bring Hitler in with an understanding that Hitler’s radicalism (and economic ignorance) would be moderated by conservatives. Papen was, according to Richard Evans, confident that Hitler “would surely be easy enough to control” (308). Hitler’s ascent to power was enabled by conservative elite, but not because they wholeheartedly agreed with his ideology: “The anxiety to destroy democracy rather than the keenness to bring the Nazis to power was what triggered the complex developments that led to Hitler’s Chancellorship” (Kershaw, Hubris, 424-5).

A large number of people had given up on Enlightenment models of democratic liberalism–public discourse based in reason, fairness, and compassion, that benefits from inclusion and diversity, and which presumes universal human rights, and which assumes that policy deliberation means a world in which no one ever completely wins or completely loses. They were hoping that a more authoritarian government would solve their various economic and cultural problems quickly and decisively, and Hitler certainly came across as decisive.

Many people believed that the explicit antisemitism of his beerhall rhetoric was tacky, although they shared many of basic premises of it. They agreed that Jews were icky and weird, but they didn’t want them killed, or their businesses destroyed; they just wanted to ensure that Jews had a marginal role in government, and maintained a kind of second-class citizenship. Hindenburg brought Hitler in to a coalition government, and many conservatives weren’t happy, but they thought it was a necessary compromise and perhaps Hitler would mature with responsibilities.The hope seems to have been that, although Hitler had long been advocating an extreme antisemitism and militarism, that was just feeding red meat to the base, and he didn’t really mean it, or he could be persuaded to become more moderate if given power. And, besides, they said, he was a better alternative than Bolshevism.

Evans quotes the French ambassador to Germany, Andre Francois-Poncet, that conservatives expected (correctly) that Hitler would “agree to their program of ‘the crushing of the left, the purging of the bureaucracy, the assimilation of Prussia and the Reich, the reorganization of the army, the re-establishment of military service.” They believed that they could all those policies out of him and discredit him (315).

To quote Kershaw again:

“The working class was cowed and broken by Depression, its organizations enfeebled and powerless. But the ruling groups did not have the mass support to maximize their ascendancy and destroy once and for all the power of organized labour. Hitler was brought in to do the job for them. That he might do more than this, that he might outlast all predictions and expand his own power immensely and at their own expense, either did not occur to them, or was regarded as an exceedingly unlikely outcome. The underestimation of Hitler and his movement by the power-brokers remains a leitmotiv of the intrigues that placed him in the Chancellor’s office.” (Hubris 425-6)

Then a crazed Dutchman set fire to the Reichstag, and the Nazis could put in place things they’d been planning for years. They framed the arsonist as a Jewish Bolshevist (he was neither), and used his actions to justify ending Germany’s experiment with democracy, and beginning its experiment with fascism.

On March 5, the Nazis were given a majority of the Reichstag in an election, and Hitler was able, on March 23, to propose an “Enabling Act“that would give him tremendous power and greatly reduce the power of the Reichstag. Since the Communist deputies were either detained or in hiding, Hitler could count on his proposal winning. The speech he gave was not necessary for getting the act passed, but it was necessary for legitimating his actions and, more important, legitimating him and delegitimating his oppositions and critics.

As with many political speeches, this one had what scholars of rhetoric call a “composite” audience. There were first, the conservative elites, who wanted assurance that he was not the beerhall demagogue who had roused his base to violence, and second, that base, who wanted more of the red meat he’d been feeding them for years, third, leaders of other countries who wanted to know what sort of person he was going to be (hopefully, a rational one), and, fourth, large numbers of people who may or may not have voted for him, but who wanted more stability, and who might have been somewhat worried about whether he was going to provide it.

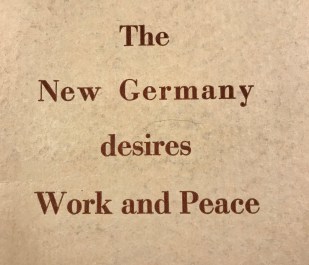

He also had an international audience for this speech (it was reported in German and published in an official English translation). They were concerned that he was an irrational, self-aggrandizing, and impractical toxic populist, that he really meant to exterminate Jews, that he intended to default on German war debts. Given the violence unleashed by his being named Chancellor, and his insistence that Nazis be allowed to murder with impunity, the attacks on Jews, and the war-mongering of Mein Kampf, the international audience wanted reassurance that Hitler would calm the fraught and paralyzingly factional political situation of Germany, not go Bolshevik, be a responsible leader, and not actually act on the foaming-at-the-mouth antisemitism of Mein Kampf.

He had an autobiography in which he bragged about manipulating others, and that his major goals were to achieve world domination and a Europe (Germany) free of liberals, people who disagreed with him, and genetically-inferior beings (which included entire peoples, such as Jews, Romas, Sintis, and Poles, as well as categories of people whose behavior showed that they were genetically criminal, such as leftists, homosexuals, union activists). He needed to persuade his base that he hadn’t abandoned any of those values or goals, and he needed to persuade “moderate” conservatives that he hadn’t meant the things he’d said to his base in his autobiography or numerous speeches. He had to appear not as a beerhall demagogue, a Jew-baiter, and a man who had probably had an affair with his niece, but a responsible political figure, while not losing the persona of the Jew-baiting beerhall demagogue his base had come to love. He had to look as though he was open to reason, and as though nothing would move him. He had to espouse his irresponsible protectionist policies and appear not to.

His previous forays into extremism meant that the bar was pretty low for him to look responsible–he really just had to look as though he was less demagogic than he had been. And, in his first speech in the position afforded him by post-Reichstag fire political contingencies, he needed to square the circle of being passionately antisemitic, determined on world domination, and reasonably committed to peace and the status quo, but needing extraordinary measures of power. And he did it. He looked like a reasonable fascist.

II. A source of unshakeable authority

“We are determined to constitute a government which, instead of constantly wavering from side to side, shall be firm and purposeful, and restore to our people a source of unshakeable authority”

When people believe that they would have rejected Hitler, it’s because they believe that since Hitler’s evil is now obvious to them, it would have been just as obvious then. That’s probably not true. People in the era were persuaded, especially after he took office, that he would just promote Germany, and they didn’t think there would be genocide or world war (for more on that point, see Backing Hitler and Letters to Hitler).

In Mein Kampf (1925) Hitler had explained his goal of a lebensraum (living space) for the Aryan race. Germany would control all of Europe and the US, all lesser races in those regions would be expelled, exterminated, or enslaved, and all the land would be redistributed to Aryans in a kind of plantation system (much like Rhodesia). As Ian Kershaw points out, the basic concept “had been a prominent strand of German imperialist ideology since the 1890s” (Hitler 248). So, much like his racialist theories, this way of thinking about Germany’s “need” would have resonated with a lot of common rhetoric of the time.

Obviously, that plan involved world war and genocide, but people supported him who, at least initially, wanted neither. How did that happen? How were large numbers of people persuaded to ignore what Hitler had promised when he was campaigning? How did people who didn’t like Nazis for their extremism and eliminationist rhetoric decide supporting their candidate would be okay?

Hitler presented himself as a person who cared about regular people, who appealed to the dominant sense that democratic deliberation was inefficient and dominated by special interests. He presented himself as someone who could cut through the Gordian knot of government bullshit and get every real German what s/he deserved. He employed a rhetoric of brave victimhood (you are being brave despite being victimized by them), and incoherent vaguely religious scapegoating (that sort of racial, sort of religious group is in a vast conspiracy to exterminate you),that enabled aggressive action (expel or kill them all) as some kind of self-defense (with various rumors, myths, and misrepresentations of violence against the ingroup). And he had large number of media who would not only perfectly replicate the talking points created about him, but who would inoculate (in the sense it’s used in rhetoric) their consumers against opposition points of view.

Rhetorical inoculation is crucial to understanding how authoritarianism works. Just as giving someone cowpox (a weak version of smallpox) will enable them to resist smallpox if they encounter it, so presenting a person with a weak version of an ideology can enable their cognitive system to reject any argument of that ideology, even much stronger versions. While that might be useful for immunology, it is profoundly anti-democratic in that the whole point of it is to persuade citizens not to listen to anyone who disagrees. It says that you already know what they’re going to say, and it’s stupid. When it works, citizens don’t know any points of view other than their own, but they think they do, and so they’re making uninformed decisions while thinking they’re as informed as they need to be.

Inoculation ensures that we have a citizenry that is simultaneously un- and mis-informed about their policy options.

Authoritarianism works by saying there are two choices: our good set of policies (our ingroup) and everything else, and those two choices are obviously between what is good (rational, moral, clear) and what is bad (irrational, immoral, relativist). Authoritarianism works when it persuades people to make decisions on the basis of group identity. Authoritarianism also always says that the situation of the ingroup is so disastrous that we don’t have time for deliberation. In Robert Paxton’s words, we are in an “overwhelming crisis beyond the reach of traditional solutions.” And Hitler could count on large parts of his audience believing that to be true—the German government really had had a hard time getting much done or solving its problems; it didn’t seem to be working. But it wasn’t working because neither the Fascists nor the Stalinists wanted it to work. They set fire to democracy and then insisted that democracy was unworkable because it caught on fire.

He could also count on the support of a lot of wealthy reactionaries and authoritarians, even ones who looked down on Hitler, because they were opposed to the higher tax obligations and restrictions on the rich that they thought social democrats would impose (who wanted a progressive tax to support a strong social safety net), and they felt threatened by the Bolsheviks. They were worried about losing their privileges (Mann). They thought that Hitler, who had a passionate (albeit profoundly irrational) base didn’t really mean what he said and wasn’t that extreme, would be matured by being in a position of power, or could be controlled. They just needed someone “to sign this stuff. We don’t need someone to think it up or design it.”

Hitler said: We are not in a bad situation because of having made bad decisions in the past. WWI didn’t start because of Germany having decided to support Austria in a stupid bluff, and our invading Belgium was the fault of England, and it had nothing to do with nationalism and racism about the French and a political system that put too much power in the hands of an individual who might have poor judgment. We’re the real victims here. The Versailles Treaty is evil (and let’s not talk about the conditions imposed on France after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870), and we only lost WWI because of Jews (who are all Bolshevists, especially the capitalists, and who are sort of a race and sort of a religion, and don’t ask too much about that or the whole capitalist/communist thing).

For much of Hitler’s audience, that was tl;dr.

What he said was: you’re in a bad situation; it can’t be your fault. You’re a German, so it can’t be Germany’s fault. IT’S THE LIBERALS. Who are Jews. And Bolsheviks. And international financiers. ALL TRUE GERMANS AGREE. Our government sucks because it isn’t giving you the things you know you deserve, and it isn’t dominating every other country, and GOD WANTS US TO BE THE BEST, and democracy involves letting other people argue and they’re all wrong and so it’s a waste of time because the true course of action is obvious to every reasonable person and so ELECT SOMEONE WHO CARES ABOUT PEOPLE LIKE YOU. And who will insist that GERMANY IS THE BEST. A strong man who will just walk into every international negotiation and dominate everyone and insist that they do what is best for Germany. As far as domestic policies, we need someone who gets people like us, who cares about us. Politicians who say it’s complicated are just trying to line their own pockets. Democratic deliberation is a waste of time–just hand over all the power to a guy who can get things done. And that’s me.

The fact is that that kind of political rhetoric never ends well, but it always looks as though it will. And it looks as though it will work out okay because it appeals to the sense that people like us are good, and so things that people like us support must be good.

I’m trying to make two points here: first, no one supports genocide or world war at the beginning, but we support policies that (unbeknownst to us) tend toward genocide and so authoritarians who think their authoritarian isn’t Hitler because s/he isn’t explicitly supporting genocide are thoroughly missing the historical lesson; second, Hitler’s success came about because he depoliticized politics–he said it wasn’t about political issues, but about whether he was the kind of person people could trust, and therefore they should hand all decisions over to him.

So, the fantasy that a lot of people have now–that they would recognize a Hitler were he to arise because they would never support someone who would advocate genocide and an obviously unnecessary war–is false in that it assumes that they would know what they know now about Hitler. Anytime an individual, institution, community, or culture comes to a disastrously bad decision (such as Germany supporting Hitler), the interesting question is not about the content of their decision (they supported Hitler) but about the process–what made supporting Hitler seem like a good decision?

We all would like to imagine that we would have been running slaves to freedom, hiding Jews, in a cell next to King in Birmingham, standing firm on the bridge in Selma, and that imagined version of ourselves is premised on our knowing what we know about how those actions turned out. Now, we know that slavery was wrong. But how do we know that? If we know that because we consume a lot of media that says slavery was wrong and the people involved in the underground railroad were good, then our method of deciding what is right and wrong is one–what our dominant media says is right or wrong–is a method that would have made us outraged if we had been raised in a proslavery culture.

So, if our method of deciding if something is right or wrong is just asking ourselves if the thing seems right or wrong then we would have supported slavery if we’d been raised in a proslavery environment. In other words, just asking ourselves whether something is right or wrong is a shitty way to determine if something is right or wrong.

Hitler persuaded people he could be trusted—if not trusted to do the right thing, at least trusted not to do the wrong thing, and the March 23, 1933 speech exemplifies how authoritarians do that.

July 31, 2017

I. “This collapse is due to internal infirmities in our national body corporate:” Popular Science, Their Conspiracies, and Agreement is All We Need

[The introduction to this argument is here.]

Many people look back at Hitler and believe someone like him could never sucker them because, they believe, he pounded on a podium shouting for the extermination of Jews on the basis of what everyone could recognize as rabid and irrational racism. They recognize that Hitler relied on charismatic leadership, but they think they’re immune to it.

Hitler didn’t begin by arguing for extermination of the Jews. He told his audience that Germany, which should be great, was in a state of political, economic, and moral collapse because it was weakened by the presence of those people. He said we’re weakened by disagreement, and the disagreement is purely the consequence of them. He said the solutions to the major problems of the era were simple, and he could (and would) enact them immediately. Germany was trapped by procedural quibbling, “parliamentarianism” (by which he meant that everything had to be argued in the equivalent of Congress), liberals who just want to slow everything down, experts who try to tell people like you and me that our beliefs are wrong, Marxists who want to destroy what we have, and Jews who are all terrorists.

Weimar Germany was (like most of Europe) profoundly antisemitic, ranging from “they’re okay as neighbors, but I wouldn’t want my daughter to marry one” through “it sure would be nice if they all went away” to “we should kill them all.” That last group wasn’t especially large, but the other versions were widespread. (And, really, the “milder” ones could be morphed into exterminationist easily.) The Jewish stereotype (in literature, film cartoons, even songs) was that Jews were clubby, greedy, crude, and damned to Hell. Sometimes that stereotype was presented as though it were positive (G.K. Chesterton’s antisemitism fits into this category, and Wyndham Lewis’ Are Jews Human is another apt example).

Many people decide that a claim is true if it’s repeated in their informational world a lot, and if it’s repeated by people they respect. If a claim is unanimously supported by their ingroup and contested by one of their outgroups, many people will decide it must be true (a version of social knowing). Basically, this whole long discussion of Hitler could be compressed in my saying that that way of approaching decisions is what enabled Hitler (and Stalin), and so anyone who approaches decisions that way doesn’t get to pretend s/he would have recognized Hitler or Stalin as evil. Nope. Congratulations: if you reason that way about politics, here is your death’s head symbol!

Karl Marx was Jewish, and many of the people in Lenin’s close circle were Jewish, and a lot of anti-Semitic propaganda equated being Jewish and being Bolshevik. Of course, most Jews weren’t Bolshevik, and not all Bolsheviks were Jews, but people engage in very sloppy reasoning when it comes to an outgroup. Since we have a tendency to assume the outgroup is essentially evil, then the bad behavior of some of them seems to typify all of them. By the early twentieth century most of the major financiers were not Jewish, but the Rothschild family came to be the symbol of international finance.

Thus, a large number of people were willing to blame Jews for Bolshevism, capitalism, the loss of WWI, entry into WWI, and anything else that needed a scapegoat. Sometimes that stereotype was presented by an author as though it wasn’t unreasonable—a hero or narrator might grant that not all Jews were involved in a worldwide conspiracy, but assert that all conspiracies were Jewish (an assumption so widespread that it amounted to a cliche in thrillers). A fair number of people also blamed Jews for draining blood from Christian boys, killing Jesus (a particularly pernicious claim), stealing consecrated hosts. Many people, especially those who had made it through the near Soviet-style revolts in some German cities, were deeply opposed to Soviet-style communism (a not unreasonable concern) but a lot of anti-communist propaganda equated Bolshevism (as it was called) and Jews. It’s important to understand that connection, otherwise it’s easy to miss why Nazism was so successful.

Jews were thoroughly marginalized in Czarist Russia, and, so, compared to the number of Jews in the general population, it could be argued that there was a disproportionate number of Jews in Lenin’s immediate circle. He also had a disproportionate number of close advisors from Georgia, and no one wonders about the disproportionate number of New Yorkers in the official and unofficial cabinet of a New York President. We expect that people will rely heavily and work with people in their social circle; it’s only if that circle is marked by ougroup membership (especially by race or religion) then we decide there is a causal correlation. Since Jews were marked as outgroup, then the Jewishness of any participant in Lenin’s revolution or cabinet was marked and assumed to have some kind of causal relationship to Bolshevism. (That most supporters of Lenin were not Jewish is ignored.)

Here’s one way to think about that. If a person wearing a t-shirt showing they support a politician, religion, or sports team you loathe treats you badly in line at the grocery store, you’ll attribute their being a jerk to their being in your outgroup. They did that jerky thing because they’re Wisconsin Synod Lutherans, and we all know how they are. That incident will confirm your sense that Wisconsin Synod Lutherans are inherently evil. If someone behaved exactly the same way but had a t-short that showed they shared some kind of identity important to you, if you are Wisconsin Synod Lutheran, then you would attribute their behavior to something else (they’re wearing someone else’s shirt, they’re having a bad day). Unhappily, therefore, a depressing number of people who self-identified as Christian equated “Jewish” with “atheist Bolshevism” (the same way that many people now equate “Muslim” with “politically motivated terrorists”).

Thus, in Weimar Germany, many people were willing to believe that Bolshevism was Jewish, and while people were willing to grant that not all Jews were Bolshevists, they believed that enough of them were that the entire “race” (and keep in mind, Judaism isn’t a race) should be removed from Germany. It was the peanut analogy—if you know that some peanuts are poison, you would throw out the whole bowl, or at least keep more from entering.

Let’s be clear: the attempt to “cleanse” Europe of all sorts of identities (Jews, Romas, Sintis, Poles, intellectuals, Marxists, union leaders, liberals, homosexuals) began as an argument that was framed as “it’s best for all of us if they go elsewhere.”

Hitler’s policies regarding stigmatized groups could be framed as reasonable throughout his career because he would appear to have been just on the edge of acceptable racist discourse. He would have appeared crude to a lot of people, but also a lot of of his followers would have found his “honesty” on “what they all knew” to be refreshing. And he didn’t immediately call for extermination; he called for refusing to allow more immigrants. Initially, his claim was that Germany needed to protect itself against parasites (takers), immigrants, peoples not capable of being really German, groups that were inherently criminal, his political opponents, and that meant more purity in the culture, more rigid actions on the part of police, less concern about due process and fairness, and a more open equation of German-ness and a particular political group.

Hitler persuaded a large number of people that he was them, that he cared about them, and they needed to throw all their faith onto him, and he persuaded others (who were appalled at the liberalism of Weimar Germany) that he was their only choice to undo the liberal policies of Weimar politics. Many people voted for him for those reasons, even ones really uncomfortable with his tendency to engage in bigoted claims about various races and religions. They believed that democracy was dead, as was shown by the inability of the Weimar democracy to make the situation better (it actually had done a pretty good job, but the main problem was that compromise and deliberation were demonized, but that’s a tangent I’ll avoid).

My point is that Hitler’s genocidal policies wouldn’t have seemed to his audience as purely racial; it would have seemed to his audience as though the groups he was targeting really were political and economic threats. A lot of people really did believe that Jews were intent on imposing communism everywhere and they could name acts of terrorism and revolution in which Jews participated, and they could point to all sorts of media, common discourse, and “walking down the street” experience to say that some groups are just useless takers—Polack jokes, getting “gypped” by someone.

There were terrorists who were Jewish; there were criminals who were Sintis. Therefore, “normal” people could “know” that a group of Jews or Romas would include terrorists and criminals, and so they defined the essence of Jews and Romas as terrorist and criminal. Germany had a lot of terroristic violence, with a lot of it (most?) committed by Nazis and other volkisch groups. But many people wrote off that violence as either justified (as self-defense against the Jews) or inessential. The US, right now, has a lot of terrorism, most of it committed by white males who self-identify as Christian. Yet, how many people worried about terrorism are worried about white male Christians? They engage in the no true Scotsman defense, and only worry about outgroup violence, and, as too many people in Weimar Germany did, they are willing to generalize about the essence of another religion, while engaging in considerable cognitive work to keep from admitting that most terrorism is ingroup.

I’m not saying that the Jews of the 1917-1933 are just like Muslims of 1996-now. I’m not making a claim about facts; I’m making a claim about how people in a moment understand things. And how they understand things largely depend on the media they consume. In Weimar Germany, a time of highly factionalized media, people were really worried because of events that had actually happened (the communist uprisings), but also ones that hadn’t (desecrations of the host, Jews having killed Jesus, but they decided those events were the consequence of identity (Jews) and not policy (the German commitment to winning WWI) or process (that there was no way for the country as a whole to get good information about the war or influence decision-making). Weimar Germany media was, all at the same time, rabidly factionalized (if you read this newspaper, you only heard about terrible things they did and never about terrible things your group did), agreed that the mistakes of WWI wouldn’t be usefully debated (but just factionalized), and agreed that significant dissent is unpatriotic.

Hitler accepted a narrative about civilization and race that was popular in some circles and also accepted among many experts (especially the new science of genetics). The idea was that evolution is progressive, so that a “more evolved” species is better in every way than a less evolved one (Gould’s Mismeasure of Man remains a really good introduction to all that discourse, even with some disagreements as to his argument on brain size measurements). In this view, “immorality” is more common among “lower” species, so that higher animals (like humans) behave in a more moral way than lower animals (like apes). In addition, dominant genetics said that there were sometimes “throwbacks” in evolution (called atavism), so that humans are sometimes born with characteristics genetically connected to earlier (and lower) stages in our evolution, such as babies born with tails. Races, many of these people argued, functioned as species, and so there are races that are closer to animals, and they are more inherently criminal, and essentially incapable of autonomy. This version of genetics was simultaneously deeply flawed and very popular. And it’s important to understand both parts to understand Hitler’s popularity.

Since morality is just as much genetic as a tail, this argument ran, and the more genetically advanced are more moral, then immorality is also an evolutionary throwback. Groups that are more immoral are more like animals in every way, and it’s because of their genetics.

The last bad idea in this cornucopia of bad ideas is that we should think about human genetics the way we think about breeding racehorses, bunnies, or chickens. Notice that throughout this discussion I haven’t defined “morality,” nor terms like “higher” or “better.” Here I’m following how geneticists wrote–they began their research by assuming that there was perfect agreement on those terms, and thereby enabled themselves not to see the circularity in their arguments. Most people charged with crimes were recent immigrants or criminalized ethnicities, and, since crime is immoral, they concluded that those ethnicities were genetically criminal. (We still make this mistake, by assuming that rates of arrest are perfect representations of rates of commission of crime.)

So, what they didn’t notice in their own research was that their own standards of “better” were actually pretty odd. They tended to equate, without noticing, market value with better. A racehorse is “better” than a drafthorse insofar as you pay more for the former than the latter, but a racehorse is a terrible draft horse. To get the fastest horse, breeding two fast horses is a good choice, but a fast horse is not always the better horse. The research on chickens and bunnies is unintentionally hilarious (with horror about the monstrosity of a bunny with one ear upright and the other floppy). It’s also contradictory, since, as mentioned above, market value was often taken as a pure measure of goodness, and market value is often enhanced by genetic oddities. Or, in other words, purebred, and inbred are pretty similar, as shown in the Hapsburg Jaw. I love Great Danes, and even I will admit that a purebred Great Dane is not a better dog than a mutt–it’s much more likely to have terrible problems. But early twentieth-century genetics assumed that purity is always better, except when it didn’t.

What’s odd to a rhetorician about the genetics rhetoric is that it was so obviously wrong, even in its era. Anthropologists, linguists, and even a lot of biologists took issue with geneticists’ arguments in the first decade of the 20th century (that’s why geneticists had to form their own organizations–they couldn’t stand the critiques). Anyone familiar with the Habsburgs knew purity wasn’t good, and genetics simultaneously assumed that purity was better AND condemned inbreeds like the Jukes family.

Early twentieth century genetics was just a muck of contradictory assumptions. For instance, it was a convention to say that a cross between a higher and lower was halfway between the two, but, of course, even royal families had their “lower” babies–epileptics, hemophiliacs, homosexuals. And anyone even a little familiar with breeding dogs or horses knew that not only did you often get a dud from two great individuals, but that there were always surprises from less than stellar lines. That it was muddled is an important point, because when a particular sustained conversation (that is, a bunch of people who have created a kind of argumentative ingroup—a subreddit, Fox News, DailyKos, analytic philosophers, native plant gardeners—sometimes called a “discourse community”) have an argument that doesn’t have internally consistent arguments, then you know you’ve got an ideologically-driven discourse community.

That point might seem a little pedantic, and it’s important for understanding when the Hitler analogy is and isn’t relevant, so I should explain it a little more. In rhetoric, it’s common to talk about enclaves, which are little safe spaces in which like-minded people can huddle together and do nothing but agree how awesome they all are.

Enclaves are great, and we all need them, and so every life should have at least one. Enclaves are places where we all agree, and we go to feel that we are part of a group that is entirely right, and entirely good, and entirely powerful.

Enclaves are useful for motivation, and, really, it’s just lovely to be in an enclave. Everything is clear, and everything is comfortable and no one will tell you that you might have fucked up.

Enclaves can be politically important. Lefty women relegated to making coffee and working the mimeograph literally got together and discovered they all shared similar experiences. Our Bodies, Our Selves came out of an enclave. The Tea Party is an enclave-based movement, as was Earth First. Within your enclave, deciding that loyalty to that group is important makes perfect sense. The institutional goal of an enclave is to make people feel safe within a group. Enclaves are also good for motivation—before putting on a show, or playing a competitive sport, and in those circumstances it wouldn’t be helpful for someone to say, “Well, maybe the other team is better, and really should win.”

But all the research on decision-making is clear that it isn’t good for a large institution or community to make decisions from within an enclave, largely because of that enclave emphasis on loyalty to the group being such a high value. Good decisions require good disagreement, and criticism of the ingroup is generally perceived as disloyalty. And, so, while it’s common for political agenda to be brainstormed within an enclave, and it’s healthy for all of us to retreat to one from time to time, political agenda should be subject to criticism, worst-case scenario thinking, assessment of weaknesses and challenges, and honest assessments of previous failures. So, at some point, that political agenda needs to be shared outside of an enclave.

Determining processes and policies within an enclave is challenging, because of the value on loyalty, and so it’s common for enclaves either to splinter into sub-communities on which everyone agrees, or to begin threatening dissenters with violence and exclusion. Unhappily, the more that an enclave values loyalty, the more likely it is to devolve into smaller communities, or become a community in which people can’t disagree.

Genetics ended up being an enclave expert discourse. Instead of respond to the serious objections and criticism of eugenics made by contemporaries, they created their own journals and departments (and as in the case of Franz Boas, tried to get really threatening critics fired). And what eugenics had to say could be defended with complicated charts and statistics (which was a relatively new field at that point), and it confirmed everyday and very popular racism. But it was popular, and it was powerful–even college textbooks endorsed it. That science was used to rationalize the US forced sterilization of 60k people, the extraordinarily restrictive 1924 Immigration Act, Japanese internment, anti-Asian immigration/naturalization rules and statutes, antimiscegenation laws, and segregation in the US. Every claim of that kind of genetics was rejected by methodologically sound research in anthropology, linguistics, and biology, but my point is that it was easy for racists to find apparently expert support for their racist policies (see Science for Segregation).

The most problematic claims of eugenics were that “race” is a biological category (the history of debates over “whiteness” show that isn’t true); that races exist on a hierarchy of civilization (some races are essentially more gifted with intelligence, morality, strength, and all the virtues that merit higher status and pay–other races are given the virtues, such as being good with children, that are connected to lower status and pay); that the “mixing” of races results in children who are closer to the “lower” than the “higher” race; and that the “white” race (sometimes Nordic, sometimes Aryan) is responsible for all the great civilizations in the history of humanity, and those civilizations fail when the white/Nordic/Aryan race stops being pure. Race-mixing, these people say, weaken civilizations. Hitler used this narrative to argue that “lesser” races had to be exterminated, and that punishing ‘race-mixing’ with death was justified. Even after the war, supporters of segregation cited the same shitty “science” that justified Hitler’s genocide–that line of argument figured into the lower courts’ rulings on Loving v. Virginia in the 60s.

So, while we look back at Hitler’s racism and see it as insane, and while the most methodologically sound scholarship of the era had long since shown it to be ideologically driven, people who wanted to believe that some racial groups were inherently more dangerous, more criminal, more prone to terrorism, more genetically driven to be poor could find experts who would tell them that they were right. Hell, they could find entire departments at some universities who would tell them that.

What made Hitler’s “science” bad wasn’t that it now looks bad to us, nor that it was a fringe science, nor that it didn’t have supporting evidence—it did. What made it bad was the logic of their arguments—their failure to define terms, to put forward internally consistent arguments, and to define the conditions that would falsify their claims. For instance, eugenicists never came up with a definition of “race” that they used consistently—sometimes they meant nationality, sometimes language group, sometimes, as in the case of “the Jews,” they talked about a religion as though it were a race (the same thing is happening now with people who refer to the “Muslim race” or who assume that “Muslim” and “Arabic” are the same).

In Germany, the “science” was slightly different, as was the religious rhetoric. In the US, there was a lot of support for “science” that said that African Americans, Latinx, Native Americans, and Asians deserved their economic, political, and cultural situation because it was the natural situation. In Germany, there wasn’t as much political need to rationalize the oppression of African Americans, Latinx, Native Americans, or Asians, but Jews, Sintis, Romas, various central and eastern European groups filled that same role, and there was the same rhetorical need to naturalize their oppression. Hitler’s long-term plan was to establish the same kind of plantation system in eastern Europe that England had in places like Rhodesia (Kershaw’s biographies of Hitler are especially good on this).

Although he called himself national socialist (meaning not the international socialists–that is, Marxist socialism), what he meant was European colonialism. In his era “socialism” meant redistribution of wealth, and he imagined a racial redistribution of wealth. Central and eastern Europe would become the Rhodesia of Germany. So, once Europe was Jew-free, then the other lesser races would behave in the ways British colonialism used Africans. Poles, for instance, would act as workers, perhaps even managers, for the large estates run by Aryans.

Hitler’s plans were more extreme that most of the dominant rhetoric of the era (which was still pretty racist), and so he was clever about keeping it out of the larger public sphere. But he meant it, as is shown by his deliberations with his generals (a different post entirely). Briefly, his military decisions were grounded in his understandings of races, and since his understandings of race were wrong, they were bad decisions. Again, that’s a different post (involving the Hitler Myth).

For this post, what matters is that German (European, to be blunt) cultural rhetoric provided a lot of support for essentializing the evil of those groups (lefties, homosexuals, Sintis anbd Romas, union leaders, Jews, Jehovah’s Witnesses, “mentally retarded”) because that rhetoric assumed that there was a clear distinction between “them” and “us” and that the differences were biological (that is, grounded in genes and incapable of genuine change).

But, as in the US, while people would support the lynching here and there of outgroup members, disproportionate incarceration rates, polite racism (social exclusion, racist employment practices, shunning people in intergroup marriages), the same people who believed that that group is essentially evil balked at government-sponsored violence in front of their eyes (Hitler, the Germans, and the Final Solution is elegant on this). Prior to the war, most Germans didn’t want all the Jews in Europe to be killed, and they probably wouldn’t have supported Hitler in 1933 had he said that was what he would do. But he didn’t say it, and they supported his putting in place the systems, policies, and processes (especially one-party government, an openly politicized and authoritarian police force, and personal loyalty to him being the central value—more on all those below), because they were okay with the kind of expulsions and restrictions they thought Hitler had in mind for those kind of scary Others.

I’ve given so much background on eugenics/genetics because I think that one mistake that people make when they think they would recognize Hitler and resist (or believe that comparing their beloved authoritarian to Hitler is a ridiculous analogy) is that they think Hitler started off by calling for genocide based on wacky science. He didn’t initially explicitly call for genocide (or, at least, people didn’t hear him saying that, and he gave himself a lot of plausible deniability), and most of his intended audience wouldn’t have seen the science as wacky.

So, when we’re worried about whether this leader is like Hitler in troubling ways, we shouldn’t be looking for someone who will use early-twentieth century genetics to argue for exterminating Jews. We also shouldn’t be looking for someone who will cite obviously whackjob “science” or fringe experts to support the bizarre notions of some marginalized group. We should worry more about a leader who is citing experts whose “science” can’t withstand the rigors of academic argument, who have had to form their own journals and organizations, but whose claims are attractive both to authoritarian leaders and to most people because they confirm common beliefs. The most important failure of those experts (and the propaganda supporting and promoting them) is that neither they nor their supporters can make arguments that are both internally consistent and apply the same rhetorical/logical standards across groups.

[image from wikimedia commons: http://wikivisually.com/wiki/Ludwig_C...]

“I cannot explain why it does not affect me:” How to make a Hitler comparison (Introduction)

Godwin’s Law is a reasonably good statement about internet arguments–that the argument is over when someone accuses the other side of being just like Hitler–because “Hitler” is what rhetoricians call an “ultimate term;” that is, all connotation and no denotation. It’s a word that powerfully evokes a set of closely associated ideas, the precise connection of which is surprisingly vague (“freedom,” “terrorist,” “political correctness”). People think they’re making a clear reference, but they aren’t (as you can tell if you ask them to define the term precisely-they just get mad). Since the invocation of Hitler is simultaneously powerful, apparently clear, but actually unclear, comparing an opponent to Hitler ends a conversation because there appears to be no useful way to refute or support the comparison.

So, what would it mean to try to have a reasonable conversation about Hitler, who he was, what he did, and how he got a fairly normal country to hand over all power to him and support him in a policy of ethnic cleansing that involved “cleansing” Europe of every member of lots of religions, ethnicities, and behaviors AND take on almost every other European power and every other major industrialized nation.

If we want to know whether a leader is like a current Hitler is some significant way, then we need to look at how Hitler looked in the moment, and not just through the lens of what we know was revealed about him later. Knowing how things played out, and what we now know, is useful, but it’s just as useful to understand why people didn’t predict those things, or didn’t know what we know. And I think a good place to start for thinking about why people didn’t worry as much about him as we think they should have is his March 23, 1933 speech to the Reichstag. Talking about that speech requires some background on Hitler and his context, and talking about comparing a current leader to Hitler requires at least a little bit of an explanation about Hitler analogies.

Everyone is like Hitler in some way–they have a two-syllable name, they’re charismatic, they like dogs, they eat pasta. An argument about a historical comparison needs to be about whether the analogy is apt, if the similarities are causally important to the outcome we want to avoid (Hitler didn’t destroy Germany because he liked dogs).

After all, Hitler did a lot of things–he was vegetarian, a dog lover, a shitty painter, a racist, a lame architect, an authoritarian who was cozy with the industrial class, a poseur art critic, a millionaire who dodged his taxes, a traditionalist when it came to gender roles, a charismatic leader. We worry about whether a current leader is just like Hitler because we’re worried about whether that leader will drag a country into authoritarian government, unnecessary war, an ultimately disastrous economic policy, the jailing of all political opponents, and genocide.

And so we need to figure out which of his characteristics are causally related to those outcomes. Being a dog owner wasn’t one of them. Being authoritarian, racist, and a charismatic leader (not a leader who is charismatic) was causally related to those outcomes, but they aren’t necessarily related (in the logical sense–not all racists engage in genocide, so the two aren’t necessarily related). Genocide is always racist, but not all racism ends in genocide.[1]

So, how did he do it? Hitler didn’t take a nation of tolerant and peaceful supporters of democracy and wave a word wand that magically transformed them into racist warmongerers. He did four things. First, he rode various very powerful cultural and political waves in Weimar German culture to power. Second, when in power, he transformed Germany into a one-party state. Third, between 1933 and 1939 (by which time it was incredibly dangerous to oppose him), he made things better for a lot of Germans. Granted, he did so in ways that would only work for the short term, but people tend not to ask about the long term. Fourth, and the one I want to talk about here, he made his authoritarianism look like not authoritarianism by reframing it as decisiveness, a stance that was helped by his carefully controlling his public image and public rhetoric, looking more reasonable than anyone expected–he had set a low bar–and saying that he just wanted peace and prosperity. He had a rhetoric that made people feel they could trust him.

And so what was that rhetoric?

July 27, 2017

Reagan and Trump

A few years ago, I was talking to one of those young people raised to believe that Reagan was pretty nearly God, and he said to me, “At first I was mad when people said Reagan has Alzheimer’s but then I decided that it didn’t matter.”

A few years ago, I was talking to one of those young people raised to believe that Reagan was pretty nearly God, and he said to me, “At first I was mad when people said Reagan has Alzheimer’s but then I decided that it didn’t matter.”

I thought that was interesting. He wasn’t mad because it was false; he was mad because it seemed mean. He didn’t change his mind about it because he went from thinking it was false to thinking it was true; he changed his mind because he found a way to explain it as non-trivial.

This was in 2005 or so, but it perfectly reproduced my experience of arguing with Reagan supporters in 1980. Reagan said a lot of things about himself and his record that were untrue. He might have sincerely believed them or not–I think he did–but if you pointed out he was saying things that were untrue, his fans said you were mean. He declared his candidacy literally on the site of one of the most appalling pro-segregation murders of the 1960s, and said he was in favor of states’ rights, and his supporters were apoplectic if you said he was appealing to racism. “He isn’t racist,” they’d say. “He’s a good man.”

If you tried to point out that the economic model on which he was going to base US policy was thoroughly irrational in that it was completely unfalsifiable, you were rejected as some kind of egghead.

When I asked a few more questions (such as, if your policies are best advocated by a person with Alzheimer’s, maybe there are problems with the policies), it became clear that he saw Reagan’s failure to be able to grasp complicated things as a virtue. That’s what made Reagan go for simple solutions, he thought, and he thought that meant that Reagan cut through the bullshit.

That, too, was my experience of Reagan supporters in the 80s (except the Marxists I knew who voted for them because they said he would bring about the people’s revolution faster, and the Dems who voted for him as a protest vote against Carter and then Mondale). They liked that he didn’t seem to understand the complexities of political situations. They sincerely believed that political issues aren’t really complicated, but are made so by professional politicians and eggheads just trying to keep their jobs, and so a person who looked at things in black and white terms would get ‘er done.

I think we have the same situation now. Clearly, the WH is made up of people who don’t understand the law about any of the things they’re trying to enact or the things they’re doing (whose defense is that they don’t and never did), who never had clear plans for any of the things they said they would achieve, who don’t understand how government actually works, who don’t understand what it means to be President, who are mad that they’re being treated the way they treated the previous President, and who are just engaged in rabid infighting.

People with even a moderate understanding of history are worried because this never works out well (for anyone, including his own party). People with a cherrypicked version of history don’t think it matters because they think he’ll enact the GOP agenda (and they think that’s great). And his base thinks it’s great because they think that a person who doesn’t think anything is complicated and isn’t deeply informed is exactly what we need.

July 23, 2017

Let’s reinvigorate the charge of religious bigotry

In the US, the term “bigot” is used interchangeably with “racist,” but its use for a long time involved religious, not racial, bigotry. At a certain point, it became more broadly used for someone who could not be persuaded out of a belief, religious or political. The OED gives the first three definitions as:

A religious hypocrite; (also) a superstitious adherent of religion; A person considered to adhere unreasonably or obstinately to a particular religious belief, practice, etc.; In extended use: a fanatical adherent or believer; a person characterized by obstinate, intolerant, or strongly partisan beliefs. (OED, Third Edition, December 2008)

The OED notes that Smollet in 1751 condemned the political discourse of his era by referring to “The crazed tory, the bigot whig.”

And that’s what’s wrong with our political discourse. It isn’t whether people are “civil” or “hostile” or even “racist.” Our problem is that our political discourse is dominated by bigoted discourse. And a lot of those bigots pretend that their views are reasonable ones related to Scripture.

Democracy works when most people are open to persuasion, and it doesn’t work when too many of us are bigots. Being open to persuasion doesn’t mean that you’ll change your mind every time someone gives you new information (the test apparently used by some studies about persuasion), but it does mean that you can imagine changing your mind, and, ideally, you can identify the conditions under which you would change your mind.

A.J. Ayer famously argued that some beliefs are falsifiable (which he described as scientific) and some aren’t (which he defined as religious). I think he was wrong in the notion that science is always falsifiable and religious never is, and there are other quibbles with his claim, but, having spent a lot time arguing with people in academic, nonacademic, fringe, and just fucking loony realms, I have come to think, while there are lots of good criticisms of the specifics of his argument, his general point–that we have beliefs we open to change and we have beliefs we will not change—is a useful and accurate description. (In fact, a lot of descriptions about whether an argument is useful or not begin with exactly that determination—are you open to changing your mind about the argument? Are you arguing with someone who is?)

A bigot is someone who cannot imagine circumstances under which she might change her mind. Or, more aptly, a bigot is someone who imagines himself as never wrong, and always able to summon evidence to support his position. What he can’t imagine (and this is what makes him irrational) is the evidence that would prove him wrong, and she condemns everyone who disagrees as so completely and obviously wrong that they should be silenced without ever having carefully listened to their argument.

I do believe that Jesus is my savior, and in a God who is omniscient and omnipotent. That belief is not open to disproof. And I am comfortable with calling that a religious belief. And, so, in that regard, I am a bigot. On the other hand, I’ve read the arguments for atheism, and various other religions, and I don’t think advocates of those beliefs should be silenced.

In addition I don’t believe that those two claims necessarily attach me to beliefs about slavery or segregation—and it’s important to remember that, for much of American history, there were entire regions in which it was insisted that being Christian necessarily meant supporting slavery and segregation. When Christian scholars of Scripture pointed out that the Scriptural based defenses of slavery and segregation were problematic, they were condemned as having a prejudiced and politicized reading of Scripture by people who insisted the Scripture endorsed US slavery practices. The notion that Scripture justified slavery as practice in the US South, especially after 1830 or so, was a bigoted reading of Scripture—not because I think it was wrong, but because its proponents refused to think carefully or critically about their own reasons and positions. They could “defend” slavery in that they could come up with (cherry-picked) proof texts, but they could argue fairly with their critics, and they couldn’t articulate the conditions under which they would change their minds. There were none. They were bigots.

Furthermore, they banned criticisms of slavery, enforcing that ban with violence. So, they had both parts of the bigot definition—their views weren’t open to disproof, and they advocated refusing to listen to criticism of their views. They were bigots on steroids, in that they advocated violence against their critics.

Right now, we’re in a situation in which a lot of very powerful people are insisting you shouldn’t listen to criticisms of the current GOP political agenda, and they’re claiming that their views are grounded in Scripture, and they are implicitly and explicitly advocating violence against their critics. You should read them. (You can start with American Family Association, or Family Research Institute, or any expert cited on Fox News. Really—go read them.)

They call themselves conservative Christians. But being theologically conservative in Christianity does not necessarily involve the current GOP political agenda. For instance, there are conservative Christian arguments for gay marriage, for women working outside the home, and even the connection between conservative Christianity and abortion is fairly new. I’m not saying that true conservative Christians have this or that view–I’m saying that being conservative theologically doesn’t necessarily lead you to the GOP political agenda. And even many conservative Christians who argue for positions more or less in line with the current GOP political agenda don’t do so in a bigoted way.

So, let’s stop using the term “conservative Christian” for people who insist that being a true Christian so necessarily means believing that the GOP agenda is right that everyone who disagrees should be threatened with violence till they shut up. “Conservative Christian” for what is actually authoritarian bigotry is strategic misnaming. Whether the Founders imagined a Christian nation is open to argument; whether they imagined a nation without disagreement is not. They valued disagreement; they valued reconsideration, deliberation, and pluralist argument.

People who pant for a one-party state, who tell their audience not to listen to anyone who disagrees, and who threaten (or justify threatening) their critics with violence are not only violating what the Founders said our country means may or may not be Christian (since they’re explicitly violating the “do unto others rule” I think that’s open to argument) but they are showing themselves to be anti-democratic authoritarian bigots.

And here is one last odd point about people like this (since I spend a lot of time arguing with them). They have a tendency to equate calling them authoritarian bigots with calling for silencing them, and that’s an interesting and important instance of projection. They believe that people who disagree with them should be silenced, so they really seem to hear all criticism of their views as an argument for silencing them. But that’s just projection.

We shouldn’t silence them. We should ask them to argue, not just engage in sloppy Jeremiads. I think our country is better if there are people who are participating in public discourse from the perspective of conservative Christianity. I think that’s a view that should be heard, and it can be heard without insisting all other views should be threatened into silence.

[The image at the top of the post is from a series of stained glass celebrating the massacre of Jews.]

July 19, 2017

Neoliberalism, liberalism, neopurconliberalism and why some people hate the ACA (pt II)

This was originally part of another post, but I cut it. There’s a bunch of stuff about how we shouldn’t use the term neoliberalism, though, so I thought I’d throw it out there.

Elsewhere, I argued that the GOP objection to the ACA is grounded in the just world hypothesis—the notion that good things happen to good people and bad things happen to bad people–and so good things (money, healthcare, food) should only be given to good people. If people want healthcare, for instance, they should get a job.

There’s also the argument that many of the GOP objected only because it was Obama who supported it. It was based, after all, on the recommendations of a very conservative think tank and Mitt Romney’s healthcare plan in Massachusetts. They didn’t want any Democratic plan to succeed because our political landscape is so rabidly factionalized that parties are willing to do harm to the country as a whole rather than let the other side succeed.

And that rabid factionalism certainly mattered, but I think there is also a sincere ideological objection, having to do with hostility to third-way neoliberalism (explained below), and the rise of what might be called neopurconliberalism because it’s a muddle of various philosophies.

Loosely, Obama’s healthcare plan was a classic example of his tendency toward what political theory folks call “third-way neoliberal.” Although in popular usage, “liberal” means people who believe in a social safety net (and tend to vote Dem or Green), in political theory, “liberal” means people who accept the Enlightenment principles of universal rights (especially property, due process, and fair trial), a separation of church and state, minimal interference in the market, and a separation of public and private. Until very recently (the 2000s, really), most GOP and Dem voters were liberal, and it was the dominant lay political theory (meaning how non-specialists explained how a government should work). There were lots of arguments as to what “minimal interference” meant, and what is private (for instance, for years, wife-beating was considered a private act, and outside the realm of government “interference”). So, most people agreed on the principle but disagreed as to how the principle plays out in specific cases.

The other category that matters for thinking about hostility to Obamacare is democratic socialism, which is often used to describe systems in which the government is democratic (little d) and the government provides an extensive safety net. Democratic socialist countries tend to have high taxes and excellent infrastructures.

In the 1970s or so, a lot of economic theorists began arguing for what is often called “neoliberalism,” which is not “liberal” in the common sense–in fact, it’s deeply and profoundly opposed to the principles of someone like LBJ, JFK, or FDR. Neoliberalism says that the market is purely rational, and we should take as much as we can away from the government and put it into the private sector. Neoliberals don’t vote Dem, and they don’t fit the common usage of liberal–they tend to vote GOP or Libertarian. Supporting neoliberalism requires ignoring the whole field of behavioral economics and all the empirical critiques of the fantasy of the rational market, but neoliberalism and neoconservatism both got coopted by people whose political and economic theories are purely ideological (in the sense that their claims are deduced from their premises, and their premises are non-falsifiable–that is, there is no evidence they would accept to get them to reconsider their premises).

On the far right, there emerged an ideology that might be called neopurconliberal, a reemergence of one very specific aspect of early American Puritanism (that wealth is a sign of saintliness), entangled into the neocon assumption that the US is entitled to dictate to all other countries how they should do things–an entitlement that should be enforced through a domination-oriented “diplomacy” and the continual threat of intervention (so, shout a lot and carry a big stick)–and the neoliberal notion that as many social practices should be thrown into the market as possible (so there is no such thing as public goods that should not be sold). Or, more accurately, the far right thoroughly and completely endorsed the “just world hypothesis” (that everyone in this world gets exactly what we deserve).

If you think about it in terms of healthcare, you can see how these ideologies play out. Democratic socialism would have in place single-payer health care, most healthcare provided by the state, and paid for by taxes of some kind. Neoliberalism would leave it all up to the market with little or no governmental control of insurance companies or healthcare providers. Third-way neoliberalism would try to develop a system that created profit incentives for insurance and healthcare providers to serve everyone—more governmental control (such as mandates) than neoliberalism, but not by providing the insurance or healthcare directly (as would happen in democratic socialism).

I really like Bertrand Russell’s argument for socialized medicine. Here’s the problem every healthcare plan faces: it’s the problem of a gambling establishment because insurance is just legalized gambling If you are running a casino, you need to make a prediction as to how much you will pay out, and you need to ensure that you will take more than you have to pay out. So, you have to have a system that collects enough from losers to pay out the winners.

Russell’s argument was exactly right: casinos work because losers pay into the system more than the winners take out. And that’s how insurance works. You have a lot of people who pay to play on the grounds that they might be someone who later gets a lot. You pay a dollar for a lottery ticket, not because you’re certain you’ll win the lottery, but because you’re willing to pay for the chance that you might win. You pay into a benefits pool, not because you’re certain you’ll win, but because you think you might.

The argument about healthcare is an argument about how to gamble. Russell saw that.

What Russell didn’t predict is how ingroup/outgroup preferences would impact healthcare decisions. We always see outrageous expenses on the part of beings with whom we identify as justified. The GOP made a big deal about death panels at the same that it was the party that had put such panels in place http://www.nationalreview.com/corner/428426/death-panel-futile-care-law-texas by reframing the issue as Obama would kill your grandmother, and many in their audience believed it because Obama is outgroup. They either never mentioned the GOP-supported death panels, denied they existed, or characterized them as just fiscal responsibility.

Looking at the issue the way Russell describes means just doing the math, and not worrying about whether the people winning at the tables are good or bad people, whether we think they “deserve” to win. Neoliberals hate the ACA because it doesn’t leave things to the market, and neopurconliberals hate it because it is not grounded in an obsession with whether healthcare is only going to people who “deserve” it.

So, this is also an argument about what we think the government should do, and how we should think about policies—in pragmatic terms, or in terms of punish/reward. Whether third-way neoliberalism is inherently bad or good from the perspective of social democrats is an interesting question, if not engaged in a purely ideological way. Can it be a bridge? Can it lead to social democratic policies? The right certainly thinks it can, and that’s why they oppose it. And we should engage the argument in pragmatic ways.

Why not having insurance can be framed as a freedom

Over at The Resurgent, Senator Mike Lee (R-Utah) explains why he would not support the compromise health care plan, even with the (amended) amendment he and Cruz proposed. And I think that Lee is perfectly sincere in his argument, and I think that his argument shows why a lot of lefty critiques of Trumpcare just don’t quite work, but I’ll explain that after I try to be really, really fair to his argument.

Lee’s objection to ACA is that: “Millions of middle-class families are being forced to pay billions in higher health insurance premiums to help those with pre-existing conditions.” He calls it a “hidden tax,” since it’s “paid every month to insurance companies instead of to the government” and he maintains that hidden tax is: “one of the most crushing financial burdens middle-class families deal with today.”

Lee’s proposals is not, as many say, that people with pre-existing conditions and expensive medical costs would get thrown off insurance entirely. Instead, this plan would split insurees into two groups: people who already have high medical costs, and are bad risks for insurers, and people who have not yet developed expensive medical costs (whom Lee consistently identifies as “the middle class”–that’s an important point, since it implies that he thinks the middle class and people with serious medical costs are different groups). The people with high medical costs, Lee argues, shouldn’t be protected through price-fixing: “We don’t have to use price controls to force middle-class families to bear the brunt of the cost of helping those who need more medical care. We could just give those with pre-existing conditions more help to get the care they need.” So, insurers are “free” to charge whatever they want, and consumers are “free” to get insurance or not (hence the name “Consumer Freedom Amendment”), and this plan will not put the financial burden of healthcare of others on “middle-class families.”