Felix Calvino's Blog, page 6

January 29, 2017

So Much Smoke I Magdalena Ball I Compulsive Reader

January 30, 2017

So Much SmokeReviewed by Magdalena Ball

The short stories that make up Felix Calvino’s book So Much Smoke are oddly familiar. Perhaps there is something universal in the migrant experience that is transmitted through his delicate prose. Perhaps it’s because of the distinctive coupling of nostalgia and immediacy that make up these dreamlike stories. The settings are charged with tenderness and a sense of loss, even when action is present tense.The stories are mostly very short, with the exception of “The Smile”, which is almost a novella in length. In nearly all of these stories, the conflict occurs in the spaces between action – in dreams, in prophesy, in a growing self-awareness, and in memory. In the first story, a young girl’s dreams are prophetic. Her mother worries she will be called names at school. Though the story has a hint of a dark edge to it, it pivots on moments of tenderness that seem to exist in an alternate space. In another story, a boy, the narrator, agrees to kill a hen for his mother, but the job is harder than it looks. When the boy uses a shotgun rather than a knife to do the dirty work, his maturity is called into question. In “What Do You Know About Your Friends”, the family home is left to two brothers after a father dies intestate. This is one of many stories about death and inheritance. The brothers have different ideas about how to manage the home and one is left struggling to manage his place on his own. In the title piece, a forty-year old man inherits the family home on his mother’s death, but as the will states that he must take the house unencumbered he has to pay bills he can’t afford. In each of these stories, there is a strong visual impressions—almost like a painting—that create the tension. The activity almost feels beside the point against these visuals. Each scene is set up in careful detail like a tableau:

The early morning autumn sky was grey as he stood and listened to the silence. At the far end of the yard, under the mango tree, the neighbour’s black and white cat watched intently for birds. (“The Smile”)

The feeling created is one of heaviness: an inertia that the characters have to struggle against. There is politics, but it is subtle. We know that Franco’s Spain is both home in the Ithaca sense – beautiful in memory, but also the place that must be escaped. Poverty, unemployment, and fear provide the backdrop. It has already been left. Sydney too, the destination, becomes defamiliarised. The protagonists are always struggling with identity; always outsiders marked by mannerism, clothing, accent. These characters tend to be caught – the role of migrant becoming a permanent state of being rather than a transitory one. It’s an uncomfortable space, where the conflict is not caused by action but by a struggle for meaning – a coming into being that never quite actualises. The plight of the migrant is a recurrent theme in all of these stories, and the ‘migratory’ process is not always a motion from place to place but also occurs through time and memory and through linguistic process, language becoming a metaphor for the self. In “The Dream Girl”, Gabriel works hard to read and write in his native Galician, discovering the work of Rosalía de Castro, a Galician author, and finds some meaning in the discovery of his transition:

Adjustment is a complex subject. Many of them [Galician migrants] have managed a measure of success, but the other life, the one up to the point of departure, is always etched in their memories. No matter how well integrated they are in the adopted society, each of them has his or her concealed hinterland. (121).

Though the stories are very much in the literary realist tradition – much of the plots centre around everyday activities, depicted without overt artifice, there is an air of magic that pervades the work. Calvino handles it very subtly, rooting the magic in natural occurrences like sleepwalking, superstition, fever, premonitions, and grief. Always there’s a sense that the world is not quite fixed and that what we’re experiencing is illusory (so much smoke), and charged by scars, memories, hunger, and all that we’ve lost. The stories that make up So Much Smoke are powerful, not so much because of what happens, but because of the way they hint at how much lurks below the surface. Though the work is rooted in the settings that Calvino creates so well, there is always a self-referential modernism that keeps pushing against a linguistic otherness: the unsettling nature of language and the shock of transition. So Much Smoke is a nuanced collection, full of place, space, and subtle epiphany.

Compulsive Readerhttp://www.compulsivereader.com/

Published on January 29, 2017 13:00

January 15, 2017

So Much Smoke I Grady Harp I Amazon.com

January 16, 2016

Amazon.com: Grady Harp's review of So Much SmokeFind helpful customer reviews and review ratings for So Much Smoke at Amazon.com.Read honest and unbiased product reviews from our users.AMAZON.COM

Félix Calvino deserves a much wider audience here in the United States. His first collection of short stories gathered under the title A HATFUL OF CHERRIES were piquant brief morsels that ranged from a few pages to extended stories and every story manages to paint imagery and place and character so clearly with the most economical style that each appears like a flashback of thought in every reader's memory bank.

Calvino was born in Galicia and spent his childhood on a farm not unlike those scenes he so frequently recalls in these stories. Under the reign of General Franco, Calvino fled to England to study and work and eventually migrated to Australia where he currently lives and writes his magical prose. From these various regions Calvino gathers the fodder for his tales - stories that take place in Spain and in Australia with settings that range from dealing with the earth as a child to discovering love as a youth to encountering the realities of small community prejudices to simply celebrating the aspects of the very young to the very aged characters he describes so well.

Calvino's writing style is the opposite of florid. With a few brief sentences on a few pages he is able to bring the reader into the focal point of his stories that usually take a quiet twist at the end, a technique that makes reading a collection of short stories more like reading a full length novel, so engrossed is the reader in his ability to capture attention and imagination. Not that his writing is without color: for instance, in the story ‘They Are Only Dreams’ he writes ‘Mama, I had a dream last night,’ the girl says. ‘It was about a man in bed. He had a white beard. His mouth was open and there was a rattling sound coming from his throat. After he stopped rattling, I heard women crying loudly.’ He knows well how to speak of love, of desire, of tragedy and of humor and is equally at home with each of these and other emotions. The other stories in this collection include ‘The Hen’, ‘What Do You Know About Your Friends?’ ‘The Road’, ‘The Gypsies’, ‘So Much Smoke’, The Smile’, ‘The Sleepwalker’, ‘The Dream Girl’, ‘Kneading the Dough’ and ‘The Valley of Butterflies’.

Some astute publisher should capture the talents of this Spanish Australian writer. He deserves center stage in the arena of authors who have mastered the art of writing short stories as well as his very fine novel ‘Alfonso’. Highly Recommended. Grady Harp, January 17

Amazon.com: Grady Harp's review of So Much SmokeFind helpful customer reviews and review ratings for So Much Smoke at Amazon.com.Read honest and unbiased product reviews from our users.AMAZON.COM

Félix Calvino deserves a much wider audience here in the United States. His first collection of short stories gathered under the title A HATFUL OF CHERRIES were piquant brief morsels that ranged from a few pages to extended stories and every story manages to paint imagery and place and character so clearly with the most economical style that each appears like a flashback of thought in every reader's memory bank.

Calvino was born in Galicia and spent his childhood on a farm not unlike those scenes he so frequently recalls in these stories. Under the reign of General Franco, Calvino fled to England to study and work and eventually migrated to Australia where he currently lives and writes his magical prose. From these various regions Calvino gathers the fodder for his tales - stories that take place in Spain and in Australia with settings that range from dealing with the earth as a child to discovering love as a youth to encountering the realities of small community prejudices to simply celebrating the aspects of the very young to the very aged characters he describes so well.

Calvino's writing style is the opposite of florid. With a few brief sentences on a few pages he is able to bring the reader into the focal point of his stories that usually take a quiet twist at the end, a technique that makes reading a collection of short stories more like reading a full length novel, so engrossed is the reader in his ability to capture attention and imagination. Not that his writing is without color: for instance, in the story ‘They Are Only Dreams’ he writes ‘Mama, I had a dream last night,’ the girl says. ‘It was about a man in bed. He had a white beard. His mouth was open and there was a rattling sound coming from his throat. After he stopped rattling, I heard women crying loudly.’ He knows well how to speak of love, of desire, of tragedy and of humor and is equally at home with each of these and other emotions. The other stories in this collection include ‘The Hen’, ‘What Do You Know About Your Friends?’ ‘The Road’, ‘The Gypsies’, ‘So Much Smoke’, The Smile’, ‘The Sleepwalker’, ‘The Dream Girl’, ‘Kneading the Dough’ and ‘The Valley of Butterflies’.

Some astute publisher should capture the talents of this Spanish Australian writer. He deserves center stage in the arena of authors who have mastered the art of writing short stories as well as his very fine novel ‘Alfonso’. Highly Recommended. Grady Harp, January 17

Published on January 15, 2017 18:15

January 12, 2017

So Much Smoke I Tim Bazzett I Rathole Books

January 13, 2017

Tim Bazzett

http://RatholeBooks.com

Review

With his new collection of stories, SO MUCH SMOKE, Felix Calvino continues to chronicle the lives and journeys of Spanish emigrants to Australia, a task he began with the stories in his first book, A HATFUL OF CHERRIES, and continued in his exquisite novella, ALFONSO.

Calvino is himself such an emigrant, and the eleven stories here are about equally divided between stories of early childhood set in poor farming communities of Galicia, in northwest Spain, and more urban settings of Australia in the seventies and beyond. SO MUCH SMOKE seems, in some ways, to be more personal than the two earlier books. This is particularly evident in "The Dream Girl," a story that is set in Galicia, but also affords the reader a glimpse years into the future, when protagonist Gabriel has moved to Australia and made a new, successful life in business. His youthful dreams of teaching and writing stories have been given up or put 'on hold,' while the titular 'dream girl' has married, become a mother and a pharmacist. But there is much more to the story than this. In "The Dream Girl," Calvino pays tribute to Galician and Spanish writers he read in his youth, including them in two reading lists Gabriel is given by a teacher -

"One contains twenty titles by Galician authors; the other names over a hundred by Spanish authors. It begins with EL CANTAR DE MIO CID, DON QUIXOTE, LAZARILLO DE TORMES and ROMANCERO GITANO, iconic works of Spanish literature from the twelfth century, all the way to the poems of Federico Garcia Lorca."

The Galician writers are more obscure (at least to me). They include Rosalia de Castro, "the illegitimate child of an upper-class woman and a Catholic priest, who never acknowledged her." Gabriel finds that "The migrant's plight is a recurring theme in her work ... [and] having been a migrant for two-thirds of his life, he agrees with her insights." Two other Galician writers that ring true to Gabriel are Emilio Pardo Bazan and Ramon del Valle Inclan, the latter "considered by some critics to be the Spanish equivalent to James Joyce ..."

But perhaps equally interesting here is the frustration and disappointment that Gabriel [i.e. Calvino] felt at how hard it was for him to read the Galician texts, despite its being his native tongue, because the Franco government had forbade the teaching and even the speaking of such 'dialects,' to also include Basque, Catalan and others.

"Years later, as an adult, this disappointment will turn into anger towards those who deprive children of the right to learn to read and write in their mother tongue .. to Gabriel it will always be a crime ... [a language] preserves memories, legends, history."

"The Dream Girl" is perhaps the most personal of Calvino's stories, because in it he is able to express his love of literature, as well as how he came to be a writer. But the centerpiece here is probably the longest of the stories, "The Smile." It tells the story of a friendship between Jose and Fidel, both emigrants, and the simple lives they live in Sydney, where Jose is a hotel night clerk and Fidel is a street sweeper. Both Fidel and his wife, Consuelo, are physically homely - ugly even - people, but their love transforms them. So yes, there is a love story here. But there is also the theme of community and upward striving for a better life so common to most of Calvino's emigrant stories set in Australia. Slowly, over a period of many months, Jose learns more and more of Fidel's story - how he met Consuelo back in Spain, how their courtship, how they came to Australia (as a part of Canberra's Spanish Migration Scheme and the Catholic Migration Committees). Their story unfolds gradually, in Calvino's trademark simple, detail-oriented style. Here's a sample -

"He washed his hands under the tap, rubbed salt and pepper on two large chickens and placed them in a baking dish, adding thin rashers of bacon on top. Waiting for the oven to heat, he filled a second baking dish with potatoes, carrots, capsicums and two small onions cut in half."

Reading this, I could not help but recall "Big Two-Hearted River," with its descriptions of Nick Adams making camp and preparing his meager meals in the Michigan north woods, and I wondered if Calvino knew that story, had been influenced by Hemingway. And yes, Calvino's writing is consistently Hemingway-esque. The subjects are different, but the stylistic similarities are unmistakable. Is it just smoke and mirrors? No, it's real. English may be Felix Calvino's third language, but you'd never know it from these stories. He is a meticulous writer at the top of his game. SO MUCH SMOKE displays so much talent. I continue to be amazed at the work of this man. Bravo, Felix. Very highly recommended.

- Tim Bazzett, author of the memoir, BOOKLOVER http://RatholeBooks.com330 West Todd AveReed City, MI 49677-1128USA

Published on January 12, 2017 13:20

January 5, 2017

So Much Smoke I James N. Powell I Goodreads

January 9, 2017

So Much Smoke

The narrative form of short fiction often ends with an unexpected unveiling. The same form, but suddenly standing before you nude. In this way short fiction is similar to another minimalist form, haiku. Many haiku, like cherry trees shedding their blossoms--one by one--expose a sadness at the heart of ephemerality. Much of Felix's stripped-down prose bares similarly poignant modes of being. You'll be hard pressed to find another writer who pulls it off with such silken abandon.

James N. Powell

Goodreads

So Much Smoke

The narrative form of short fiction often ends with an unexpected unveiling. The same form, but suddenly standing before you nude. In this way short fiction is similar to another minimalist form, haiku. Many haiku, like cherry trees shedding their blossoms--one by one--expose a sadness at the heart of ephemerality. Much of Felix's stripped-down prose bares similarly poignant modes of being. You'll be hard pressed to find another writer who pulls it off with such silken abandon.

James N. Powell

Goodreads

Published on January 05, 2017 15:16

December 19, 2016

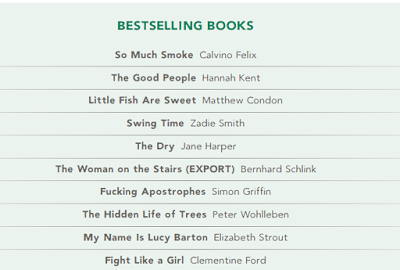

Book Sales

Published on December 19, 2016 16:15

December 16, 2016

Goodreads Giveaway

.goodreadsGiveawayWidget { color: #555; font-family: georgia, serif; font-weight: normal; text-align: left; font-size: 14px; font-style: normal; background: white; } .goodreadsGiveawayWidget p { margin: 0 0 .5em !important; padding: 0; } .goodreadsGiveawayWidgetEnterLink { display: inline-block; color: #181818; background-color: #F6F6EE; border: 1px solid #9D8A78; border-radius: 3px; font-family: "Helvetica Neue", Helvetica, Arial, sans-serif; font-weight: bold; text-decoration: none; outline: none; font-size: 13px; padding: 8px 12px; } .goodreadsGiveawayWidgetEnterLink:hover { color: #181818; background-color: #F7F2ED; border: 1px solid #AFAFAF; text-decoration: none; } Goodreads Book Giveaway

So Much Smoke by Felix Calvino

So Much Smoke by Felix Calvino

So Much Smoke by Felix Calvino

So Much Smoke by Felix Calvino Giveaway ends January 10, 2017.

See the giveaway details at Goodreads.

Enter Giveaway

Published on December 16, 2016 13:58

December 1, 2016

So Much Smoke I Halford I Sydney Review of Books

December 2, 2016

Félix Calvino’s Lost Galicia

James Halford is a recipient of a 2016 SRB-CA Emerging Critics Fellowship. This is the second of three essays by Halford that will appear on the Sydney Review of Books, alongside essays by other fellowship recipients, Ben Brooker and Ali Jane Smith.

‘Galicia is a garden where one always breathes pure aromas, freshness, and poetry,’ wrote the romantic novelist and poet Rosalía de Castro in 1863. ‘Lakes, waterfalls, streams … serene blue skies like those of Italy … Need I say more? No pen could enumerate its charms.’ De Castro and other nineteenth-century nationalists of Galicia’s literary Rexurdimiento were moved to proclaim their love of the region at the height of the greatest exodus in its history. Between 1860 and 1910 something like half a million Galicians left for the Americas. This was the largest in a series of mass migrations from the region, which was among the poorest in Spain from the eighteenth century right through to the 1970s. For centuries Galicians had to periodically abandon their farms due to overcrowding, unemployment, and crises in agricultural production. During the nineteenth century they arrived in Latin America in such numbers that ‘gallego’ jokes, based on peasant stereotypes, became a genre of their own. In 1955, the Galician intellectual Ramón Otero Pedrayo, a less romantic nationalist than De Castro, described his home, not as a garden, but as a ‘land of goodbyes.’

Out of this history of material struggle and displacement, Galicia’s writers have fashioned a rich literature. In recent times, a new crop of Galician-language authors – Manuel Rivas, Xose Luis Mendez, and María do Carme Kruckenberg among the most prominent – have carried on the Rexurdimiento tradition at home, even as diasporic writers have created a new branch of Galician writing abroad. All of them have had to negotiate a relationship with the controversial legacy of Galicia’s best-known twentieth-century writer, the Franco loyalist and 1989 Nobel Laureate for literature, Camilo José Cela.

Franco’s dictatorship drove mass migration, not just from Galicia but from all corners of Spain, for decades. The post-war Spanish diaspora spread to Australia, where expatriate communities developed in both Sydney and Melbourne. Australian Immigration Department records show that about 26,000 Spaniards arrived in Australia between 1945 and 1975. Many of them came under Australian government-assisted migration schemes such as Operación Canguro (1958-1963). This was less a humanitarian gesture on the part of the Australian government, and more an acknowledgement that the preferred British migrants were unlikely to work for paltry wages in the Queensland cane fields or the Riverina tobacco plantations. The early Spanish migrants often languished in squalid camps, like the infamous Bonegilla, for extended periods._____

The Galician-Australian writer, Félix Calvino, arrived with a slightly later wave of Spanish migrants. Born in 1944, in about 65 kilometres south-east of the Galician capital, Santiago de Compostela, Calvino fled Spain in 1964, on his twentieth birthday, to avoid military service. In the late 1960s, after a few years learning English in the UK, he emigrated to Sydney and established himself as a restaurateur, wine merchant, and travel agent. He was a prominent member of the Spanish expatriate community, married and had a family. In the nineties, he made a new start in Melbourne, and finally fulfilled a lifelong goal of undertaking tertiary study. His talents as a fiction writer were not discovered until he was well into his fifties. At the encouragement of the Greek-Australian writer George Papaellinas, one of his teachers at the University of Melbourne, Calvino began publishing short stories in Australian and US literary magazines.

His first short-story collection, A Hatful of Cherries (2007), is notable for its juxtaposition of Galician and Australian settings. About half the stories unfold in the underdeveloped, autocratic post-war Galicia of Calvino’s youth, the rest deal with working-class Spanish migrants in 1960s and 1970s Australia. The ghosts of the Spanish Civil War have haunted his writing from the start. In ‘Don’t Touch Anything,’ the child narrator is sent away from the burial of a school mate’s grandfather when the adults stumble upon a mass grave. ‘After that,’ he remarks, ‘dreams of earth and bones often visited me in my sleep.’ Another early story, ‘Two Men at the Border,’ fictionalises the ordeal of escaping Franco’s Spain.Calvino’s second book, the novella Alfonso (2013), tells the story of a Galician man struggling to invent himself in 1960s Sydney. Alfonso is desperate for the love of an Australian woman, but remains a virgin into his thirties, unable to establish or maintain an adult relationship. Why this sensitive, hard-working, and resilient young man cannot give or receive love is the book’s central mystery. Nothing that we know of him – the loss of his father in the Civil War, his lapsed Catholicism, or his macho Spanish friends’ warnings – fully explains his decade-long terror of Australian women, his decision to sever contact with his elderly mother in Galicia, or the depths of psychological torment to which he subjects himself in his dilapidated Surry Hills terrace house. Calvino’s unsettling imagery and language disrupt what at first appears to be a simple, realist Bildungsroman. The novel gestures at a culturally particular form of homesickness that can never be fully expressed in English. Morriña, the specifically Galician ache for home, has been a favourite subject of its writers since De Castro’s time._____

Eight of the eleven stories in Calvino’s new collection, So Much Smoke, return to the nameless Galician village that appeared in his first collection. The very short story or microcuento is a Calvino speciality. At only 600-words, the opener, ‘They Are Only Dreams,’ stands out for its unity and concision. As mother and daughter watch milk boil on the stone hearth of a farm kitchen in winter, the girl confesses she has dreamed of an old man dying. Bells are heard tolling in the village across the river and a neighbour brings news that the shoemaker has died in the night. Spooked, the mother shares this latest proof of the girl’s prophetic gifts with her husband. The man listens as he oils a fox trap in the barn, but refuses to believe.

A sequence of concrete images and sense impressions – the milk, the fire, the dead man’s white beard, the bells, the snow-covered hills, the trap – fulfil a function akin to the effet de réel of the classic realist short story (we might be reading Chekhov or Maupassant). Yet the absence of an authoritative narrator gives equal weight to the man’s positivist viewpoint and the woman’s mystical, religious one. In the tiny clockwork universe of the microcuento, the fox trap never springs closed, so that both readings of the story remain available, and the unresolved tension lingers.

It is no literary effect that Calvino’s stories set in rural Galicia in the 1950s and 1960s sometimes feel like they could be unfolding in the nineteenth century or even the middle ages. After the Nationalist victory, Franco deliberately set back the clock in the Spanish countryside, aiming, as George Orwell wrote in Homage to Catalonia, ‘not so much to impose Fascism as to restore feudalism.’ But Calvino also bears witness to the exhaustion of the old rural order and the arrival of modernity. In ‘The Road,’ a peasant dies without leaving a will, and his two sons must negotiate the division of the family land. Benito tricks his simpleton younger brother José into accepting the swampy, unproductive plot by the coast. But a landslide in a storm results in a sudden reversal of fortunes: ‘the receding waters exposed a stone road, emerging from the sea like a recalled ghost.’ Heritage tourism, not agriculture, it turns out, represents Galicia’s economic future.

The new collection’s novella-length centrepiece, ‘The Smile,’ unfolds closer to home. It is set in the Sydney Spanish community during the final years of the Franco dictatorship, a world of English classes and shift-work, football on the radio, and paella on the stove. The young Galician protagonist, José, befriends an older Spanish couple, Fidel and Consuelo – a street sweeper and a cleaner – whose Sunday lunches in the Andalusian-style garden of their home are a refuge for exiled Spaniards. Calvino’s attention to the rituals of food and drink highlights the way meals bind friendship networks together in the new country. ‘It’s like my mother’s cooking, which I miss,’ remarks one character.

In the Australian stories the elements of parable, fairy tale, and magic realism are less pronounced but not absent. Both Fidel and Consuelo have disfigured faces that frighten children and attract stares from adults. As Consuelo is dying in hospital of an inoperable brain tumour, José experiences a ghostly visitation outside his kitchen window. And, after her death, he continually senses her presence in the mirrors of Fidel’s home. José’s first encounter with loss and grief changes his cynical, skirt-chasing ways. As the younger man helps Fidel through the ‘exquisite pain,’ of his wife’s loss, and learns more about his friends’ marriage, their relationship comes to represent, in his mind, an ideal of self-acceptance and unconditional love he would one day like to experience. Meanwhile, the bachelor must teach his older friend the life skills he needs to survive alone: ‘Fidel learned to boil a potato, fry an egg, grill a steak and hang out the laundry.’ Like Alfonso, Fidel retreats from the material hardship and loneliness of migrant life into memories of his Spanish past. For him, as for thousands of other scattered Spaniards, Franco’s death in 1975, opens the possibility of return.

Calvino’s fiction, too, seems to be moving back to the village. The stories in So Much Smoke rely upon the defamiliarisation effect used in his earlier books: Galicia is made strange through the English language; Australia is made strange by non-native English and a Galician worldview. In this collection, however, the teeming social world of the village takes over, threatening to spill beyond the boundaries of the short form.This collection firmly establishes Calvino as an English prose stylist. The influence of Anglophone modernist minimalism is apparent and appropriate. Through absence and implication, the stories register feelings of loss the characters themselves often lack the language to articulate. If, as Rosalía de Castro wrote, to sing of Galicia in the Galician language offers ‘consolation against evil, relief from pain,’ to write of it in English implies something else entirely.

ReferencesAustralian Government Department of Immigration and Border Protection. ‘Historical Migration Statistics.’ 2016. Web. Oct 17 2016.

Calvino, Félix. Alfonso. Melbourne: Arcadia, 2013.

– A Hatful of Cherries. Melbourne: Arcadia, 2007.

– So Much Smoke. Melbourne: Arcadia, 2016.

De Castros, Rosalia. Cantares Gallegos. 1863. Buenos Aires: Tor, 1947.

Fernandez-Shaw, Carlos M. Espana Y Australia: Quinientos Anos De Relaciones.Madrid: Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores de Espana, 2000.

García, Rodri. ‘A Vida Do Emigrante, Ata Certo Punto, É Fantasía E Realidade.’ La Voz de Galicia 19 May 2014. Acessed 14 September 2016.

Giraldez, Jose Miguel. ‘Félix Calviño: La Memoria De Galicia Siempre Será Mi Refugio.’ El Correo Gallego 2011. Acessed 14 September 2016.

Leggott, Sarah. Memory, War, and Dictatorship in Recent Spanish Fiction by Women. Vol. 21. London: Routledge, 2015.

Paredes, Carlos Sixirei, Xose Ramon Campos Alvarez, and Enrique Fernandez Martinez. ‘Asocianismo Galego No Exterior.’ Xunta de Galicia 2001. Acessed 13 Sep 2016.

Preston, Paul. A Concise History of the Spanish Civil War. London: Harper Collins, 1996.

Rodriguez Galdo, Maria Xose, and Abel Losada Alvarez. ‘A Contribution to the Study of Historical Relations between Galicia and Australia. Migration and the Labour Market.’ Australia and Galicia: Defeating the Tyranny of Distance. Eds. Maria Jesus Lorenzo Modia, and Roy C. Boland Osegueda. 2008. 101-30.The SRB-CA Emerging Critics Fellowships are supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

________________

The Sydney Review of Books is an initiative of the Writing and Society Research Centre.

Félix Calvino’s Lost Galicia

James Halford is a recipient of a 2016 SRB-CA Emerging Critics Fellowship. This is the second of three essays by Halford that will appear on the Sydney Review of Books, alongside essays by other fellowship recipients, Ben Brooker and Ali Jane Smith.

‘Galicia is a garden where one always breathes pure aromas, freshness, and poetry,’ wrote the romantic novelist and poet Rosalía de Castro in 1863. ‘Lakes, waterfalls, streams … serene blue skies like those of Italy … Need I say more? No pen could enumerate its charms.’ De Castro and other nineteenth-century nationalists of Galicia’s literary Rexurdimiento were moved to proclaim their love of the region at the height of the greatest exodus in its history. Between 1860 and 1910 something like half a million Galicians left for the Americas. This was the largest in a series of mass migrations from the region, which was among the poorest in Spain from the eighteenth century right through to the 1970s. For centuries Galicians had to periodically abandon their farms due to overcrowding, unemployment, and crises in agricultural production. During the nineteenth century they arrived in Latin America in such numbers that ‘gallego’ jokes, based on peasant stereotypes, became a genre of their own. In 1955, the Galician intellectual Ramón Otero Pedrayo, a less romantic nationalist than De Castro, described his home, not as a garden, but as a ‘land of goodbyes.’

Out of this history of material struggle and displacement, Galicia’s writers have fashioned a rich literature. In recent times, a new crop of Galician-language authors – Manuel Rivas, Xose Luis Mendez, and María do Carme Kruckenberg among the most prominent – have carried on the Rexurdimiento tradition at home, even as diasporic writers have created a new branch of Galician writing abroad. All of them have had to negotiate a relationship with the controversial legacy of Galicia’s best-known twentieth-century writer, the Franco loyalist and 1989 Nobel Laureate for literature, Camilo José Cela.

Franco’s dictatorship drove mass migration, not just from Galicia but from all corners of Spain, for decades. The post-war Spanish diaspora spread to Australia, where expatriate communities developed in both Sydney and Melbourne. Australian Immigration Department records show that about 26,000 Spaniards arrived in Australia between 1945 and 1975. Many of them came under Australian government-assisted migration schemes such as Operación Canguro (1958-1963). This was less a humanitarian gesture on the part of the Australian government, and more an acknowledgement that the preferred British migrants were unlikely to work for paltry wages in the Queensland cane fields or the Riverina tobacco plantations. The early Spanish migrants often languished in squalid camps, like the infamous Bonegilla, for extended periods._____

The Galician-Australian writer, Félix Calvino, arrived with a slightly later wave of Spanish migrants. Born in 1944, in about 65 kilometres south-east of the Galician capital, Santiago de Compostela, Calvino fled Spain in 1964, on his twentieth birthday, to avoid military service. In the late 1960s, after a few years learning English in the UK, he emigrated to Sydney and established himself as a restaurateur, wine merchant, and travel agent. He was a prominent member of the Spanish expatriate community, married and had a family. In the nineties, he made a new start in Melbourne, and finally fulfilled a lifelong goal of undertaking tertiary study. His talents as a fiction writer were not discovered until he was well into his fifties. At the encouragement of the Greek-Australian writer George Papaellinas, one of his teachers at the University of Melbourne, Calvino began publishing short stories in Australian and US literary magazines.

His first short-story collection, A Hatful of Cherries (2007), is notable for its juxtaposition of Galician and Australian settings. About half the stories unfold in the underdeveloped, autocratic post-war Galicia of Calvino’s youth, the rest deal with working-class Spanish migrants in 1960s and 1970s Australia. The ghosts of the Spanish Civil War have haunted his writing from the start. In ‘Don’t Touch Anything,’ the child narrator is sent away from the burial of a school mate’s grandfather when the adults stumble upon a mass grave. ‘After that,’ he remarks, ‘dreams of earth and bones often visited me in my sleep.’ Another early story, ‘Two Men at the Border,’ fictionalises the ordeal of escaping Franco’s Spain.Calvino’s second book, the novella Alfonso (2013), tells the story of a Galician man struggling to invent himself in 1960s Sydney. Alfonso is desperate for the love of an Australian woman, but remains a virgin into his thirties, unable to establish or maintain an adult relationship. Why this sensitive, hard-working, and resilient young man cannot give or receive love is the book’s central mystery. Nothing that we know of him – the loss of his father in the Civil War, his lapsed Catholicism, or his macho Spanish friends’ warnings – fully explains his decade-long terror of Australian women, his decision to sever contact with his elderly mother in Galicia, or the depths of psychological torment to which he subjects himself in his dilapidated Surry Hills terrace house. Calvino’s unsettling imagery and language disrupt what at first appears to be a simple, realist Bildungsroman. The novel gestures at a culturally particular form of homesickness that can never be fully expressed in English. Morriña, the specifically Galician ache for home, has been a favourite subject of its writers since De Castro’s time._____

Eight of the eleven stories in Calvino’s new collection, So Much Smoke, return to the nameless Galician village that appeared in his first collection. The very short story or microcuento is a Calvino speciality. At only 600-words, the opener, ‘They Are Only Dreams,’ stands out for its unity and concision. As mother and daughter watch milk boil on the stone hearth of a farm kitchen in winter, the girl confesses she has dreamed of an old man dying. Bells are heard tolling in the village across the river and a neighbour brings news that the shoemaker has died in the night. Spooked, the mother shares this latest proof of the girl’s prophetic gifts with her husband. The man listens as he oils a fox trap in the barn, but refuses to believe.

A sequence of concrete images and sense impressions – the milk, the fire, the dead man’s white beard, the bells, the snow-covered hills, the trap – fulfil a function akin to the effet de réel of the classic realist short story (we might be reading Chekhov or Maupassant). Yet the absence of an authoritative narrator gives equal weight to the man’s positivist viewpoint and the woman’s mystical, religious one. In the tiny clockwork universe of the microcuento, the fox trap never springs closed, so that both readings of the story remain available, and the unresolved tension lingers.

It is no literary effect that Calvino’s stories set in rural Galicia in the 1950s and 1960s sometimes feel like they could be unfolding in the nineteenth century or even the middle ages. After the Nationalist victory, Franco deliberately set back the clock in the Spanish countryside, aiming, as George Orwell wrote in Homage to Catalonia, ‘not so much to impose Fascism as to restore feudalism.’ But Calvino also bears witness to the exhaustion of the old rural order and the arrival of modernity. In ‘The Road,’ a peasant dies without leaving a will, and his two sons must negotiate the division of the family land. Benito tricks his simpleton younger brother José into accepting the swampy, unproductive plot by the coast. But a landslide in a storm results in a sudden reversal of fortunes: ‘the receding waters exposed a stone road, emerging from the sea like a recalled ghost.’ Heritage tourism, not agriculture, it turns out, represents Galicia’s economic future.

The new collection’s novella-length centrepiece, ‘The Smile,’ unfolds closer to home. It is set in the Sydney Spanish community during the final years of the Franco dictatorship, a world of English classes and shift-work, football on the radio, and paella on the stove. The young Galician protagonist, José, befriends an older Spanish couple, Fidel and Consuelo – a street sweeper and a cleaner – whose Sunday lunches in the Andalusian-style garden of their home are a refuge for exiled Spaniards. Calvino’s attention to the rituals of food and drink highlights the way meals bind friendship networks together in the new country. ‘It’s like my mother’s cooking, which I miss,’ remarks one character.

In the Australian stories the elements of parable, fairy tale, and magic realism are less pronounced but not absent. Both Fidel and Consuelo have disfigured faces that frighten children and attract stares from adults. As Consuelo is dying in hospital of an inoperable brain tumour, José experiences a ghostly visitation outside his kitchen window. And, after her death, he continually senses her presence in the mirrors of Fidel’s home. José’s first encounter with loss and grief changes his cynical, skirt-chasing ways. As the younger man helps Fidel through the ‘exquisite pain,’ of his wife’s loss, and learns more about his friends’ marriage, their relationship comes to represent, in his mind, an ideal of self-acceptance and unconditional love he would one day like to experience. Meanwhile, the bachelor must teach his older friend the life skills he needs to survive alone: ‘Fidel learned to boil a potato, fry an egg, grill a steak and hang out the laundry.’ Like Alfonso, Fidel retreats from the material hardship and loneliness of migrant life into memories of his Spanish past. For him, as for thousands of other scattered Spaniards, Franco’s death in 1975, opens the possibility of return.

Calvino’s fiction, too, seems to be moving back to the village. The stories in So Much Smoke rely upon the defamiliarisation effect used in his earlier books: Galicia is made strange through the English language; Australia is made strange by non-native English and a Galician worldview. In this collection, however, the teeming social world of the village takes over, threatening to spill beyond the boundaries of the short form.This collection firmly establishes Calvino as an English prose stylist. The influence of Anglophone modernist minimalism is apparent and appropriate. Through absence and implication, the stories register feelings of loss the characters themselves often lack the language to articulate. If, as Rosalía de Castro wrote, to sing of Galicia in the Galician language offers ‘consolation against evil, relief from pain,’ to write of it in English implies something else entirely.

ReferencesAustralian Government Department of Immigration and Border Protection. ‘Historical Migration Statistics.’ 2016. Web. Oct 17 2016.

Calvino, Félix. Alfonso. Melbourne: Arcadia, 2013.

– A Hatful of Cherries. Melbourne: Arcadia, 2007.

– So Much Smoke. Melbourne: Arcadia, 2016.

De Castros, Rosalia. Cantares Gallegos. 1863. Buenos Aires: Tor, 1947.

Fernandez-Shaw, Carlos M. Espana Y Australia: Quinientos Anos De Relaciones.Madrid: Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores de Espana, 2000.

García, Rodri. ‘A Vida Do Emigrante, Ata Certo Punto, É Fantasía E Realidade.’ La Voz de Galicia 19 May 2014. Acessed 14 September 2016.

Giraldez, Jose Miguel. ‘Félix Calviño: La Memoria De Galicia Siempre Será Mi Refugio.’ El Correo Gallego 2011. Acessed 14 September 2016.

Leggott, Sarah. Memory, War, and Dictatorship in Recent Spanish Fiction by Women. Vol. 21. London: Routledge, 2015.

Paredes, Carlos Sixirei, Xose Ramon Campos Alvarez, and Enrique Fernandez Martinez. ‘Asocianismo Galego No Exterior.’ Xunta de Galicia 2001. Acessed 13 Sep 2016.

Preston, Paul. A Concise History of the Spanish Civil War. London: Harper Collins, 1996.

Rodriguez Galdo, Maria Xose, and Abel Losada Alvarez. ‘A Contribution to the Study of Historical Relations between Galicia and Australia. Migration and the Labour Market.’ Australia and Galicia: Defeating the Tyranny of Distance. Eds. Maria Jesus Lorenzo Modia, and Roy C. Boland Osegueda. 2008. 101-30.The SRB-CA Emerging Critics Fellowships are supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

________________

The Sydney Review of Books is an initiative of the Writing and Society Research Centre.

Published on December 01, 2016 22:03

November 30, 2016

Alfonso I Jennifer Popa I Antipodes

November 30, 2016

In the quiet company of a dreamer

Jennifer PopaAustin, Texas.

Often the novice writer is told that her characters need to have desires, wants, obsessions. While it seems a rather obvious statement, the question “What does this character want?” can summon a cringe from the writer. Matters such as plot, dialogue, or structure—these are manageable craft points, in that they are sometimes easier to pin down, but succinctly describing the innermost desires of a human proves a bit unwieldy. There is something inherently personal and loaded in the question, especially when asked of the writer herself, who is both attempting to depict it and also the inventor of said desire. Even in our own lives, it is difficult to say precisely what we want, at least not plainly or without qualifiers, and if we can identify it, we are not always right. Yet Félix Calvino navigates this question with ease in his slender novel Alfonso, as his title character’s desires are palpable; each page is saturated with his wish for connection. This is possibly because the character’s life parallels the author’s own. Alfonso’s sense of longing is a want so unmistakable, so tangible on the page, that the reader inevitably inherits its burden.

The book opens on Alfonso walking home from his construction job, as he experiences the quiet yearning upon seeing the doppelgänger of a girl from his village. He remembers the village girl at their first communion “dressed in white and looking more angel than girl” (3). He decides he must meet the replica girl and devises plans to encounter her again at the bus stop.

Alfonso’s world is one of duality. There is a double consciousness as he oscillates between replication and reinvention, between his Spanishness and his Australianness. There is a split in his person at the moment he leaves Spain, when his two discernible selves take shape: the one from before and the other who looks toward a bright though elusive future. Still, he remains hopeful that his turn will come. Although he has escaped poverty—an achievement that serves as the springboard for all his good fortune—in Australia he has stayed within the safety of his Spanish bubble. If he wanted, he could lead a life with minimal assimilation among a community of immigrants, but mostly Alfonso’s world is one of loneliness. In his kitchen, he dances with a spatula and a glass of wine, pretending that he is instead dancing with a beautiful woman. He befriends a neighborhood tomcat, which he names Guapo, but even the cat remains aloof: “He also concluded reluctantly that in Guapo’s heart, there was limited space for him” (43). As he restores his row house, he talks to the disembodied voice of a woman, who is part ghostly companion, part invention, part hallucination. The woman’s voice is complimentary, though they sometimes quarrel about his design choices. There is an inevitable claustrophobia to his routine:

The four walls he had washed and painted twice as a gesture of friendship would have captured, as a mirror would, his frustration at trying to sew on a button, or trying not to scorch a new shirt; his clumsy attempts at cooking dinner with half of the ingredients missing until he trained himself to write a shopping list before going shopping; his relentless learning and relearning of English words; his chores of washing, cleaning, daily bed-making, and weekly changing of the bed sheets. These same walls would have recorded his loneliness in daytime and sadness always at night. The narrow wardrobe, the Triumph stove, the couch, two wooden chairs, and the aluminum table with the green Formica top would have watched his character crossing from youth to man, although he could not identify the exact turning point. Perhaps the pieces came together like a jigsaw. (33)

For the reader, the tangible objects in Alfonso’s home take center stage: the carrots and potatoes he is cooking for dinner, the cabinets he restores, and the telephone that does not ring. They only fade to the background when Alfonso retreats to memory to reimagine the details of an encounter with a woman. The care he takes in constructing a life that would welcome a companion and these visions of companionship are so earnest. Yet even when his dream woman arrives in the form of the beautiful Australian Nancy, he is not entirely sure what to do. Sometimes his naiveté trumps his desires, just as his loneliness can be at times willful.

Alfonso’s immigrant experience is deceptively simple. Very little happens in the span of these 117 pages, but there is an economy in Calvino’s narrative that allows us to fully engage with Alfonso. The rhythm of his solitary routine renders an agreeable hum on the page, in part because Alfonso is quite likable as characters go. This is not to say that he is not fallible but that he is human, and there is a universal familiarity in his anxieties and dreams. One cannot help but admire his deliberate efforts: when he is rebuffed by the replica girl, he sets out to learn English through course work, becoming a member of the library and reading his Reader’s Digest subscription. After years as a “bed-sitter,” he buys a dilapidated house and restores it faithfully every day for three years; there is a tenderness in his dismissing his male friends who vilify women. Quite simply, I enjoy his company, and there is a comfort in occupying his headspace. While the immigrant experience might be foreign for the reader, Alfonso teaches us something about the ways in which we live, in particular about the moments when we might feel like strangers to our own lives.

Félix Calvino, Alfonso Author(s): Jennifer PopaSource: Antipodes, Vol. 30, No. 1 (June 2016), pp. 231-233Published by: Wayne State University PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.13110/antipodes.30.1.0231

http://australianliterature.org/

Félix Calvino. Alfonso. Melbourne:Arcadia, 2013. 117 pp. A$22.95. ISBN: 978-1-925003-20-8

In the quiet company of a dreamer

Jennifer PopaAustin, Texas.

Often the novice writer is told that her characters need to have desires, wants, obsessions. While it seems a rather obvious statement, the question “What does this character want?” can summon a cringe from the writer. Matters such as plot, dialogue, or structure—these are manageable craft points, in that they are sometimes easier to pin down, but succinctly describing the innermost desires of a human proves a bit unwieldy. There is something inherently personal and loaded in the question, especially when asked of the writer herself, who is both attempting to depict it and also the inventor of said desire. Even in our own lives, it is difficult to say precisely what we want, at least not plainly or without qualifiers, and if we can identify it, we are not always right. Yet Félix Calvino navigates this question with ease in his slender novel Alfonso, as his title character’s desires are palpable; each page is saturated with his wish for connection. This is possibly because the character’s life parallels the author’s own. Alfonso’s sense of longing is a want so unmistakable, so tangible on the page, that the reader inevitably inherits its burden.

The book opens on Alfonso walking home from his construction job, as he experiences the quiet yearning upon seeing the doppelgänger of a girl from his village. He remembers the village girl at their first communion “dressed in white and looking more angel than girl” (3). He decides he must meet the replica girl and devises plans to encounter her again at the bus stop.

Alfonso’s world is one of duality. There is a double consciousness as he oscillates between replication and reinvention, between his Spanishness and his Australianness. There is a split in his person at the moment he leaves Spain, when his two discernible selves take shape: the one from before and the other who looks toward a bright though elusive future. Still, he remains hopeful that his turn will come. Although he has escaped poverty—an achievement that serves as the springboard for all his good fortune—in Australia he has stayed within the safety of his Spanish bubble. If he wanted, he could lead a life with minimal assimilation among a community of immigrants, but mostly Alfonso’s world is one of loneliness. In his kitchen, he dances with a spatula and a glass of wine, pretending that he is instead dancing with a beautiful woman. He befriends a neighborhood tomcat, which he names Guapo, but even the cat remains aloof: “He also concluded reluctantly that in Guapo’s heart, there was limited space for him” (43). As he restores his row house, he talks to the disembodied voice of a woman, who is part ghostly companion, part invention, part hallucination. The woman’s voice is complimentary, though they sometimes quarrel about his design choices. There is an inevitable claustrophobia to his routine:

The four walls he had washed and painted twice as a gesture of friendship would have captured, as a mirror would, his frustration at trying to sew on a button, or trying not to scorch a new shirt; his clumsy attempts at cooking dinner with half of the ingredients missing until he trained himself to write a shopping list before going shopping; his relentless learning and relearning of English words; his chores of washing, cleaning, daily bed-making, and weekly changing of the bed sheets. These same walls would have recorded his loneliness in daytime and sadness always at night. The narrow wardrobe, the Triumph stove, the couch, two wooden chairs, and the aluminum table with the green Formica top would have watched his character crossing from youth to man, although he could not identify the exact turning point. Perhaps the pieces came together like a jigsaw. (33)

For the reader, the tangible objects in Alfonso’s home take center stage: the carrots and potatoes he is cooking for dinner, the cabinets he restores, and the telephone that does not ring. They only fade to the background when Alfonso retreats to memory to reimagine the details of an encounter with a woman. The care he takes in constructing a life that would welcome a companion and these visions of companionship are so earnest. Yet even when his dream woman arrives in the form of the beautiful Australian Nancy, he is not entirely sure what to do. Sometimes his naiveté trumps his desires, just as his loneliness can be at times willful.

Alfonso’s immigrant experience is deceptively simple. Very little happens in the span of these 117 pages, but there is an economy in Calvino’s narrative that allows us to fully engage with Alfonso. The rhythm of his solitary routine renders an agreeable hum on the page, in part because Alfonso is quite likable as characters go. This is not to say that he is not fallible but that he is human, and there is a universal familiarity in his anxieties and dreams. One cannot help but admire his deliberate efforts: when he is rebuffed by the replica girl, he sets out to learn English through course work, becoming a member of the library and reading his Reader’s Digest subscription. After years as a “bed-sitter,” he buys a dilapidated house and restores it faithfully every day for three years; there is a tenderness in his dismissing his male friends who vilify women. Quite simply, I enjoy his company, and there is a comfort in occupying his headspace. While the immigrant experience might be foreign for the reader, Alfonso teaches us something about the ways in which we live, in particular about the moments when we might feel like strangers to our own lives.

Félix Calvino, Alfonso Author(s): Jennifer PopaSource: Antipodes, Vol. 30, No. 1 (June 2016), pp. 231-233Published by: Wayne State University PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.13110/antipodes.30.1.0231

http://australianliterature.org/

Félix Calvino. Alfonso. Melbourne:Arcadia, 2013. 117 pp. A$22.95. ISBN: 978-1-925003-20-8

Published on November 30, 2016 17:10

November 27, 2016

Alfonso I Review I Cass Moriarty

November 28, 2016

Cass Moriarty Author · Sometimes a novella is the perfect length - long enough to engage with the characters and to get your teeth into the story; short enough to carry around with you, and to still get that satisfactory feeling of finishing a book! And when the novella is a colourful tale, simply told, full of smells and sounds and visions and ideas and memories and dreams and hopes ... well, so much the better. Felix Calvino's novella Alfonso is all of these things. Alfonso is a Spanish migrant who hopes to master the English language, to prosper, and to meet a good woman, in his new homeland of Australia (not necessarily in that order). This is the story of his journey. It begins with clear and distinct memories of what and who he has left behind - his family, his church, his village, his dead father (killed in the war). It progresses to his first experiences in a land far removed from his place of birth in terms of, well, almost everything - climate and weather, landscape, language, culture, customs and people. It depicts in vivid detail his first struggling attempts to gain a foothold in his new country - simple steps such as purchasing furniture and household implements, to eventually buying a small house and completely renovating it, room by room. And always, hovering in the background of all his successes and failures over the years, is his want and need for a woman to share his life, and his bed. This is a book that is easy to read; a straightforward story of home and travels, of arrivals and departures, of making a nest of one's own. It is an interesting and sensitive portrait of the migrant experience of the sixties and seventies, and of just how much it costs - financially, socially, and emotionally - to leave behind all you know in order to follow your hopes for something better. I am looking forward to the launch of Felix's new collection of short stories, So Much Smoke, at Avid Reader on Friday, 16 December.

Sometimes a novella is the perfect length - long enough to engage with the characters and to get your teeth into the story; short enough to carry around with you, and to still get that satisfactory feeling of finishing a book! And when the novella is a colourful tale, simply told, full of smells and sounds and visions and ideas and memories and dreams and hopes ... well, so much the better. Felix Calvino's novella Alfonso is all of these things. Alfonso is a Spanish migrant who hopes to master the English language, to prosper, and to meet a good woman, in his new homeland of Australia (not necessarily in that order). This is the story of his journey. It begins with clear and distinct memories of what and who he has left behind - his family, his church, his village, his dead father (killed in the war). It progresses to his first experiences in a land far removed from his place of birth in terms of, well, almost everything - climate and weather, landscape, language, culture, customs and people. It depicts in vivid detail his first struggling attempts to gain a foothold in his new country - simple steps such as purchasing furniture and household implements, to eventually buying a small house and completely renovating it, room by room. And always, hovering in the background of all his successes and failures over the years, is his want and need for a woman to share his life, and his bed. This is a book that is easy to read; a straightforward story of home and travels, of arrivals and departures, of making a nest of one's own. It is an interesting and sensitive portrait of the migrant experience of the sixties and seventies, and of just how much it costs - financially, socially, and emotionally - to leave behind all you know in order to follow your hopes for something better. I am looking forward to the launch of Felix's new collection of short stories, So Much Smoke, at Avid Reader on Friday, 16 December.

Cass Moriarty Author ·

Sometimes a novella is the perfect length - long enough to engage with the characters and to get your teeth into the story; short enough to carry around with you, and to still get that satisfactory feeling of finishing a book! And when the novella is a colourful tale, simply told, full of smells and sounds and visions and ideas and memories and dreams and hopes ... well, so much the better. Felix Calvino's novella Alfonso is all of these things. Alfonso is a Spanish migrant who hopes to master the English language, to prosper, and to meet a good woman, in his new homeland of Australia (not necessarily in that order). This is the story of his journey. It begins with clear and distinct memories of what and who he has left behind - his family, his church, his village, his dead father (killed in the war). It progresses to his first experiences in a land far removed from his place of birth in terms of, well, almost everything - climate and weather, landscape, language, culture, customs and people. It depicts in vivid detail his first struggling attempts to gain a foothold in his new country - simple steps such as purchasing furniture and household implements, to eventually buying a small house and completely renovating it, room by room. And always, hovering in the background of all his successes and failures over the years, is his want and need for a woman to share his life, and his bed. This is a book that is easy to read; a straightforward story of home and travels, of arrivals and departures, of making a nest of one's own. It is an interesting and sensitive portrait of the migrant experience of the sixties and seventies, and of just how much it costs - financially, socially, and emotionally - to leave behind all you know in order to follow your hopes for something better. I am looking forward to the launch of Felix's new collection of short stories, So Much Smoke, at Avid Reader on Friday, 16 December.

Sometimes a novella is the perfect length - long enough to engage with the characters and to get your teeth into the story; short enough to carry around with you, and to still get that satisfactory feeling of finishing a book! And when the novella is a colourful tale, simply told, full of smells and sounds and visions and ideas and memories and dreams and hopes ... well, so much the better. Felix Calvino's novella Alfonso is all of these things. Alfonso is a Spanish migrant who hopes to master the English language, to prosper, and to meet a good woman, in his new homeland of Australia (not necessarily in that order). This is the story of his journey. It begins with clear and distinct memories of what and who he has left behind - his family, his church, his village, his dead father (killed in the war). It progresses to his first experiences in a land far removed from his place of birth in terms of, well, almost everything - climate and weather, landscape, language, culture, customs and people. It depicts in vivid detail his first struggling attempts to gain a foothold in his new country - simple steps such as purchasing furniture and household implements, to eventually buying a small house and completely renovating it, room by room. And always, hovering in the background of all his successes and failures over the years, is his want and need for a woman to share his life, and his bed. This is a book that is easy to read; a straightforward story of home and travels, of arrivals and departures, of making a nest of one's own. It is an interesting and sensitive portrait of the migrant experience of the sixties and seventies, and of just how much it costs - financially, socially, and emotionally - to leave behind all you know in order to follow your hopes for something better. I am looking forward to the launch of Felix's new collection of short stories, So Much Smoke, at Avid Reader on Friday, 16 December.

Published on November 27, 2016 23:41

Alfonso I Review

November 28, 2016

Cass Moriarty Author ·

Cass Moriarty Author ·

Sometimes a novella is the perfect length - long enough to engage with the characters and to get your teeth into the story; short enough to carry around with you, and to still get that satisfactory feeling of finishing a book! And when the novella is a colourful tale, simply told, full of smells and sounds and visions and ideas and memories and dreams and hopes ... well, so much the better. Felix Calvino's novella Alfonso is all of these things. Alfonso is a Spanish migrant who hopes to master the English language, to prosper, and to meet a good woman, in his new homeland of Australia (not necessarily in that order). This is the story of his journey. It begins with clear and distinct memories of what and who he has left behind - his family, his church, his village, his dead father (killed in the war). It progresses to his first experiences in a land far removed from his place of birth in terms of, well, almost everything - climate and weather, landscape, language, culture, customs and people. It depicts in vivid detail his first struggling attempts to gain a foothold in his new country - simple steps such as purchasing furniture and household implements, to eventually buying a small house and completely renovating it, room by room. And always, hovering in the background of all his successes and failures over the years, is his want and need for a woman to share his life, and his bed. This is a book that is easy to read; a straightforward story of home and travels, of arrivals and departures, of making a nest of one's own. It is an interesting and sensitive portrait of the migrant experience of the sixties and seventies, and of just how much it costs - financially, socially, and emotionally - to leave behind all you know in order to follow your hopes for something better. I am looking forward to the launch of Felix's new collection of short stories, So Much Smoke, at Avid Reader on Friday, 16 December.

Sometimes a novella is the perfect length - long enough to engage with the characters and to get your teeth into the story; short enough to carry around with you, and to still get that satisfactory feeling of finishing a book! And when the novella is a colourful tale, simply told, full of smells and sounds and visions and ideas and memories and dreams and hopes ... well, so much the better. Felix Calvino's novella Alfonso is all of these things. Alfonso is a Spanish migrant who hopes to master the English language, to prosper, and to meet a good woman, in his new homeland of Australia (not necessarily in that order). This is the story of his journey. It begins with clear and distinct memories of what and who he has left behind - his family, his church, his village, his dead father (killed in the war). It progresses to his first experiences in a land far removed from his place of birth in terms of, well, almost everything - climate and weather, landscape, language, culture, customs and people. It depicts in vivid detail his first struggling attempts to gain a foothold in his new country - simple steps such as purchasing furniture and household implements, to eventually buying a small house and completely renovating it, room by room. And always, hovering in the background of all his successes and failures over the years, is his want and need for a woman to share his life, and his bed. This is a book that is easy to read; a straightforward story of home and travels, of arrivals and departures, of making a nest of one's own. It is an interesting and sensitive portrait of the migrant experience of the sixties and seventies, and of just how much it costs - financially, socially, and emotionally - to leave behind all you know in order to follow your hopes for something better. I am looking forward to the launch of Felix's new collection of short stories, So Much Smoke, at Avid Reader on Friday, 16 December.

Cass Moriarty Author ·

Cass Moriarty Author ·

Sometimes a novella is the perfect length - long enough to engage with the characters and to get your teeth into the story; short enough to carry around with you, and to still get that satisfactory feeling of finishing a book! And when the novella is a colourful tale, simply told, full of smells and sounds and visions and ideas and memories and dreams and hopes ... well, so much the better. Felix Calvino's novella Alfonso is all of these things. Alfonso is a Spanish migrant who hopes to master the English language, to prosper, and to meet a good woman, in his new homeland of Australia (not necessarily in that order). This is the story of his journey. It begins with clear and distinct memories of what and who he has left behind - his family, his church, his village, his dead father (killed in the war). It progresses to his first experiences in a land far removed from his place of birth in terms of, well, almost everything - climate and weather, landscape, language, culture, customs and people. It depicts in vivid detail his first struggling attempts to gain a foothold in his new country - simple steps such as purchasing furniture and household implements, to eventually buying a small house and completely renovating it, room by room. And always, hovering in the background of all his successes and failures over the years, is his want and need for a woman to share his life, and his bed. This is a book that is easy to read; a straightforward story of home and travels, of arrivals and departures, of making a nest of one's own. It is an interesting and sensitive portrait of the migrant experience of the sixties and seventies, and of just how much it costs - financially, socially, and emotionally - to leave behind all you know in order to follow your hopes for something better. I am looking forward to the launch of Felix's new collection of short stories, So Much Smoke, at Avid Reader on Friday, 16 December.

Sometimes a novella is the perfect length - long enough to engage with the characters and to get your teeth into the story; short enough to carry around with you, and to still get that satisfactory feeling of finishing a book! And when the novella is a colourful tale, simply told, full of smells and sounds and visions and ideas and memories and dreams and hopes ... well, so much the better. Felix Calvino's novella Alfonso is all of these things. Alfonso is a Spanish migrant who hopes to master the English language, to prosper, and to meet a good woman, in his new homeland of Australia (not necessarily in that order). This is the story of his journey. It begins with clear and distinct memories of what and who he has left behind - his family, his church, his village, his dead father (killed in the war). It progresses to his first experiences in a land far removed from his place of birth in terms of, well, almost everything - climate and weather, landscape, language, culture, customs and people. It depicts in vivid detail his first struggling attempts to gain a foothold in his new country - simple steps such as purchasing furniture and household implements, to eventually buying a small house and completely renovating it, room by room. And always, hovering in the background of all his successes and failures over the years, is his want and need for a woman to share his life, and his bed. This is a book that is easy to read; a straightforward story of home and travels, of arrivals and departures, of making a nest of one's own. It is an interesting and sensitive portrait of the migrant experience of the sixties and seventies, and of just how much it costs - financially, socially, and emotionally - to leave behind all you know in order to follow your hopes for something better. I am looking forward to the launch of Felix's new collection of short stories, So Much Smoke, at Avid Reader on Friday, 16 December.

Published on November 27, 2016 23:41